Moore v. Illinois Motion for Leave to File, Statement of Interest, and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moore v. Illinois Motion for Leave to File, Statement of Interest, and Brief Amici Curiae, 1971. 3c6981a2-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e10c9fad-92bc-4653-aae2-6c539283ff2c/moore-v-illinois-motion-for-leave-to-file-statement-of-interest-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

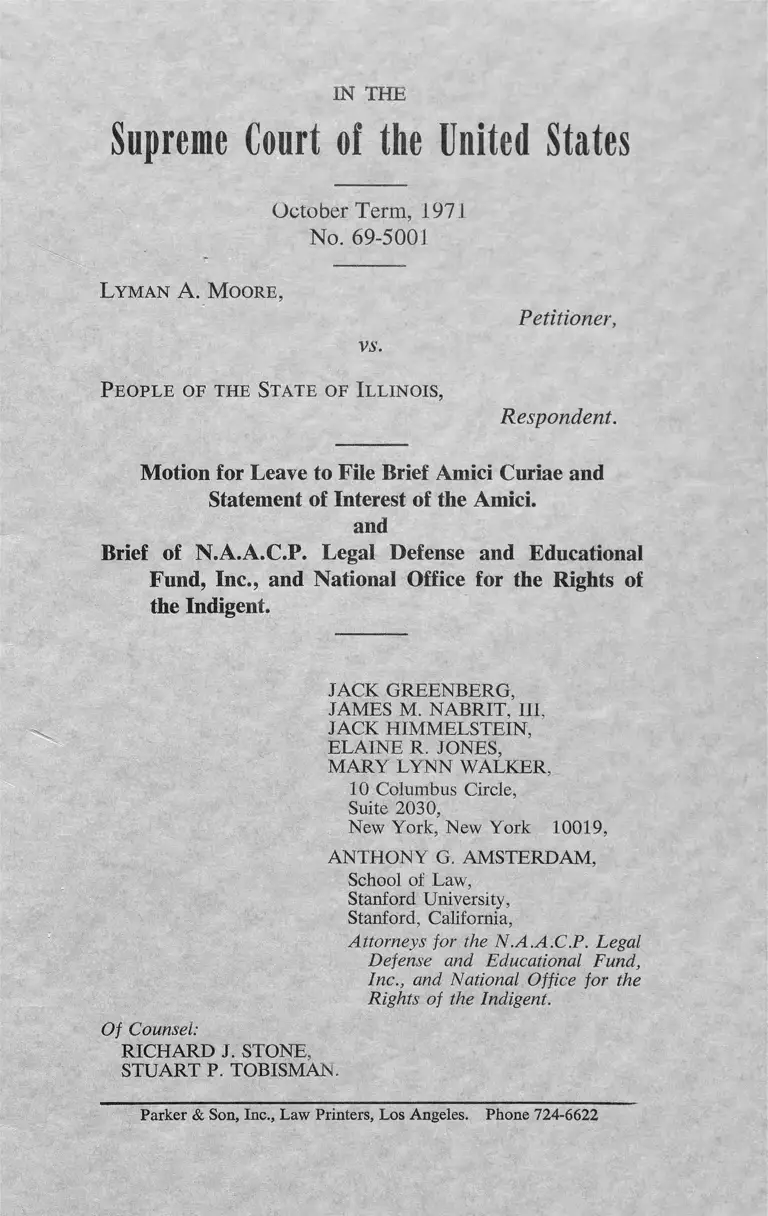

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

Octo ber Term, 1971

No. 69-500J

L ym an A. M o ore ,

Vi*.

P e o pl e of the State o f I l lin o is ,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and

Statement of Interest of the Amici,

and

Brief of N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and National Office for the Rights of

the Indigent.

JACK GREENBERG,

JAMES M. NABRIT, 111,

JACK H1MMELSTEIN,

ELAINE R. JONES,

MARY LYNN WALKER,

10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030,

New York, New York 10019,

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM,

School of Law,

Stanford University,

Stanford, California,

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and National Office for the

Rights of the Indigent.

Of Counsel:

RICHARD J. STONE,

STUART P. TOBISMAN,

Parker & Son, Inc., Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone 724-6622

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and

Statement of Interest of the Amici ....................... I

Statement of Facts ............... ....................................... 7

Summary of Argument ............................................... . 8

Argument ........... .......................... ..... ...................... . 9

I.

The Death Penalty Cannot Be Carried Out in

This Case Because Veniremen Who Voiced

Mere General Objections to the Death Penal

ty Were Removed From the Jury Which Im

posed the Sentence .............................................. 9

II.

The Question of Whether the Tenor of the Voir

Dire in This Case Differed From That in With

erspoon Is Irrelevant to the Issue of Whether

Veniremen Were Improperly Excluded .......... 16

III.

The Availability of Peremptory Challenges to

the State Does Not Render Harmless the Im

proper Exclusion of Veniremen Under With

erspoon .............. .........-........... .............................. 18

Conclusion ........................................... .......................... 21

Appendix. Excerpts From the Record on Voir

Dire Examination ........ ....... ................. .....App. p. 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Articles Page

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice. Report, The Challege

of Crime in a Free Society (1967), p. 143 ...... 2

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment

(1952), p .284 ............................................................ 2

United Nations, Department of Economic and So

cial Affairs, Capital Punishment— Developments

1961-1965, 1967, p. 2 0 ............................................ 2

Weihofen, the Urge to Punish (1956), pp. 164-65

....................................................................................... 2

Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde, Comparison of the Exe

cuted and the Commuted Among Admissions to

Death Row, 53 J. Crim. L., Crim & Pol. Sci.

(1962), p. 301 .......................................................... 2

Cases

Adderly v. Wainwright, 272 F. Supp. 530 (1967) .. 4

Anderson, In Re, 69 Cal.2d 613 (1968) ............... 19

Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1968) .......... 13

Marion v. Beto, 434 F.2d 29 (1970) ........................ 10

Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967) ............. 3

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1969) ............... 14

Moorer v. South Carolina, 368 F.2d 458 (1966) .... 3

People v. Moore, 42 I11.2d 73, 246 N.E.2d 299

(1969) .............................................................. 4, 7, 16

People v. Speck, 41 111.2d 177, 242 N.E.2d 208

(1968) ...................................................16, 17, 18, 21

Sims and Abrams, Matter of, Nos. 24271-2, decided

August 10, 1967 ............... 3

State v. Mathis, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A.2d 20

(1968) ...................................................................18, 21

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ........

.................................7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

...................................................................17, 18, 19, 21

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 69-5001

L ym an A. M o ore ,

vs.

Petitioner,

P e o pl e of th e State o f I l l in o is ,

Respondent.

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and

Statement of Interest of the Amici.

Movants N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and National Office for the Rights of the In

digent respectfully move the Court for permission to file

the attached brief amici curiae, for the following rea

sons. The reasons assigned also disclose the interest of

the amici.

(1) Movant N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorpo

rated under the laws of the State of New York in 1939.

It was formed to assist Negroes to secure their consti

tutional rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter

declares that its purposes include rendering legal aid

gratuitously to Negroes suffering injustice by reason of

race who are unable, on account of poverty to employ

legal counsel on their own behalf. The charter was ap

proved by a New York court, authorizing the organiza

tion to serve as a legal aid society. The N.A.A.C.P. Le

— 2-

gal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (L D F), is in

dependent of other organizations and is supported by

contributions from the public. For many years its at

torneys have represented parties in this Court and the

lower courts, and it has participated as amicus curiae

in this Court and other courts, in matters resulting in de

cisions that have had a profoundly reformative effect

upon the administration of criminal justice.

(2) A central purpose of the Fund is the legal eradi

cation of practices in our society that bear with dis

criminatory harshness upon Negroes and upon the poor,

deprived, and friendless, who too often are Negroes. In

order more effectively to achieve this purpose, the LDF

in 1965 established as a separate corporation movant

National Office for the Rights of the Indigent (NORI).

This organization, whose income is provided initially by

a grant from the Ford Foundation, has among its objec

tives the provision of legal representation to the poor

in individual cases and the presentation to appellate

courts of arguments for changes and developments in

legal doctrine which unjustly affect the poor.

(3) LDF attorneys have handled many capital cases

over the years, particularly matters involving Negro de

fendants charged with capital offenses in the Southern

States. This experience has led us to the view, con

firmed by the studies of scholars1 and more recently

XE.g., President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Ad

ministration of Justice, Report, The Challenge of Crime in a Free

Society 143 (1967); United Nations, Department of Economic and

Social Affairs, Capital Punishment—Developments 1961-1965

(ST/SOA/SD/IO) 20 (1967); Weihofen, the Urge to Punish

164-65 (1956); Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punish

ment, 284 Annals 8, 14-17 (1952); Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde,

Comparison of the Executed and the Commuted Among Admis

sions to Death Row, 53 J. Crim. L., Crim & Pol. Sci. 301

(1962).

— 3—

by empirical research undertaken under LDF auspices,2

that the death penalty is administered in the United

States in a fashion that makes racial minorities, the de

prived and downtrodden, the peculiar objects of capital

charges, capital convictions, and sentences of death.

Our experience has convinced us that this and other in

justices are referable in part to certain common prac

tices in capital trial procedure, which depart alike from

the standards of an enlightened administration of crimi

nal justice and from the minimum requirements of

fundamental fairness fixed by the Constitution of the

United States for proceedings by which human life may

be taken. Finally, we have come to appreciate that in

the uniquely stressful and often contradictory litigation

pressures of capital trials and direct appeals, ordinari

ly handled by counsel appointed for indigent defend

ants, many circumstances and conflicts may impede the

presentation of attacks on these unfair and unconstitu

tional practices; and that in the post-appeal period,

such attacks are grievously handicapped by the ubiqui

tous circumstances that the inmates of the death rows

of this Nation are as a class impecunious, mentally de

ficient, unrepresented and therefore legally helpless in

2A study of the effect of racial factors upon capital sentencing

for rape in the Southern States (which virtually alone retain the

death penalty for that crime) was undertaken in 1965, with LDF

financial support, by Dr. Marvin E. Wolfgang and Professor An

thony G. Amsterdam. The nature of the study is described in the

memorandum appended to the report of Moorer v. South Caro

lina, 368 F.2d. 458 (4th Cir. 1966), and in Matter of Sims and

Abrams, 5th Cir. Nos. 24271-2, decided August 10, 1967. Its

results, so far analyzed, show persuasively that the death penalty

is discriminatorily applied against Negroes at least in rape cases.

One aspect of these results, limited to the State of Arkansas, was

presented in the record in Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650

(1967).

4

the face of death.3 Common state practice makes no

provision for the furnishing of legal counsel to these

men.

(4) For these reasons, amici LDF and NORI have

undertaken a major campaign of litigation attacking on

federal constitutional grounds several of the most

vicious common practices in the administration of capi

tal criminal procedure, and assailing the death penalty

itself as a cruel and unusual punishment. The status

of that litigation is described more fully elsewhere. Suf

fice it to say here that we represent or are assisting

attorneys who represent, more than half of the 400

men on death row in the United States; and the lives

of virtually all of these men will be affected by the

Court’s decision in this and the other cases now before

the Court on the death penalty.

(5) Counsel for the petitioner in Moore has con

sented to the filing of a brief amici curiae by the

3Recently, in connection with Adderly v. Wainwright, 272 F.

Supp. 530 (M.D. Fla. 1967) LDF lawyers were authorize by

court order to interview all of the condemned men on death row

in Florida. The findings of these court-ordered interviews, sub

sequently reported by counsel to the court, indicated that of 34

men interviewed whose direct appeals had been concluded,

17 were without legal representation (except for purposes of

the Adderly suit itself, a class action having as one of its

purposes of declare their constitutional right to appointment

of counsel); 11 others were represented by volunteer lawyers

associated with the LDF or ACLU; and in the case of 2

more, the status of legal representation was unascertained. All

34 men (and all other men interviewed on the row) were in

digent) the mean intelligence level for the death row population

(even as measured by a nonverbal test which substantially over

rated mental ability in matters requiring literacy, such as the in

stitution or maintenance of legal proceedings) were below nor

mal; unrepresented men were more mentally retarded than the few

who were represented; most of the condemned men were, by oc

cupation, unskilled, farm or industrial labors; and the mean

number of years of schooling for the group was a little over

eight years (which does not necessarily indicate eight grades

completed).

■5—

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent,

as has counsel for the respondent State of Illinois.

Wherefore, movants pray that the attached brief

amici curiae be permitted to be filed with the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G r ee n b e r g ,

Ja m es M. N a brit , III,

J ack H im m e l s t e in ,

E lain e R. J o n es ,

M ary L ynn W a lk er ,

10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030,

New York, New York 10019,

A n th o n y G. A m sterd a m ,

School of Law,

Stanford University,

Stanford, California,

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and National Office for the

Rights of the Indigent.

Of Counsel:

R ichard J. St o n e ,

Stuart P. T o bism an .

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 69-5001

L ym an A. M o ore ,

vs.

Petitioner,

P e o p l e of th e State o f I l l in o is ,

Respondent.

Brief of N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and National Office for the Rights of

the Indigent.

Statement of Facts.

Petitioner was found guilty of murder before the

Circuit Court, Cook County, State of Illinois, and sen

tenced to death. The conviction and sentence were up

held by the Supreme Court of Illinois in People v.

Moore, 42 U1.2d 73, 246 N.E.2d 299 (1969). A peti

tion for -a writ of certiorari was filed with the Court on

June 23, 1969, supplemented on July 20, 1970, and

granted on June 28, 1971. There are three questions

before the Court, only one of which is discussed in this

brief, namely, eight veniremen were removed for cause

when they voiced general objections to capital punish

ment or stated that they had religious or conscientious

scruples against the death penalty in a proper case;

in the light of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510

(1968), may a state court of review affirm a death

sentence,

8-

(a) on the ground that the tenor of voir dire ex

amination was unlike that of Witherspoon?

(b) on the ground that the prosecution had suf

ficient peremptory challenges to have eliminated

those prospective jurors eligible to serve under

Witherspoon?

Summary of Argument.

We urge the Court to reverse the imposition of the

death sentence in this case on the grounds that the jury

selection process resulted in the unconstitutional exclu

sion of veniremen who voiced general objections to the

death penalty. The exclusion of these veniremen was

contrary to the Court’s decision in Witherspoon v. Illi

nois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). We further urge the Court

to amplify its Witherspoon decision to end, once and

for all, continued efforts by some lower courts to im

properly avoid the impact of Witherspoon by focusing

on irrelevant distinctions such as those drawn by the

court below in this case.

ARGUMENT.

— 9—

1.

The Death Penalty Cannot Be Carried Ont in This

Case Because Veniremen Who Voiced Mere Gen

eral Objections to the Death Penalty Were Removed

From the Jury Which Imposed the Sentence.

In the case before the Court, twelve veniremen were

removed from the jury panel because of reservations

they had concerning imposition of the death penalty.

An excerpt from the voir dire covering the questioning

of each of the excluded veniremen is set forth in the

Appendix attached hereto. The only relevent question

is whether any of these veniremen were removed con

trary to the standards set forth in Witherspoon.

In Witherspoon this Court held that:

“ [A] sentence of death cannot be carried out if

the jury that imposed or recommended it was

chosen by excluding veniremen for cause simply

because they voiced general objections to the death

penalty or expressed conscientious or religious

scruples against its infliction.” Witherspoon v. Illi

nois, supra at 522.

A narrow reading of Witherspoon makes it clear that

any test used to determine whether a venireman has

been properly excluded from a capital case must at

least be consistent with the Court’s statement that its

decision had no bearing on a State’s power to exclude

veniremen who make it

“. . . unmistakably clear (1) that they would

automatically vote against the imposition of capi

tal punishment without regard to any evidence

that might be developed at the trial of the case

before them, or (2) that their attitude toward the

1 0 -

death penalty would prevent them from making

an impartial decision as to the defendant’s guilt.”

Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra at 522-23 n. 21.

Thus, at a minimum, Witherspoon says that a venire

man may not be excluded for cause because of his

views on the death penalty unless: (1) his views are

unmistakably clear, and (2) his views would auto

matically compel him to vote against imposition of the

death penalty or would prevent him from making the

required impartial determination of guilt or innocence.

It is also clear that Witherspoon will countenance

no exclusions made on any broader basis than that

stated by the Court in footnote 21. Before stating its

minimum requirements for exclusion, the Court cau

tioned in the very same footnote that:

“ [i] f the voir dire testimony in a given case in

dicates that veniremen were excluded on any

broader basis than this, the death sentence cannot

be carried out even if applicable statutory or case

law in the relevent jurisdiction would appear to

support only a narrower ground of exclusion.”

(Emphasis added.)

Lastly, it is clear that in deciding whether a venire

man has been properly excluded, any ambiguity which

casts doubt upon whether he has made his views un

mistakably clear must be resolved against exclusion.

Judge Simpson, writing for a unanimous court reversing

for violation of Witherspoon in Marion v. Beto, 434 F.

2d 29, 31 (5th Cir. 1970), noted:

“The Supreme Court further implied that doubts

concerning the ability of a venireman to subordi

— 11

nate his personal views to his oath as a juror to

obey the law of the state should be resolved against

exclusion, stating in footnote 9, on page 515-516

of the opinion, 88 S. Ct. on page 1774:

“ ‘Unless a venireman states unambiguously

that he would automatically vote against the

imposition of capital punishment no matter what

the trial might reveal, it simply cannot be as

sumed that this is his position.’ (Emphasis

added.) [Footnote omitted. ] ”

It is clear that each of the excluded veniremen were

removed from the jury in this case solely because they

voiced “general objections to the death penalty or ex

pressed conscientious or religious scruples against its

inflictions”. Veniremen Byrne, Lorens, Kristock, Petty,

Threatt, Gorski and Hohnwald were excluded merely

because they said that they did not believe in capital

punishment or that they had religious or conscientious

scruples against infliction of the death penalty in a

proper case. In Witherspoon, this Court specifically con

sidered “proper case” exclusions and declared:

“ [I] t cannot be assumed that a juror who de

scribed himself as having ‘conscientious or re

ligious scruples’ against the infliction of the death

penalty or against its infliction ‘in a proper case’

[Citations ] thereby affirms that he could never vote

in favor of it or that he would not consider doing so

in the case before him. [Citations] Obviously

many jurors ‘could, notwithstanding their consci

entious scruples [against capital punishment], re

turn . . . [a] verdict [of death] and . . . make

— 12—

their scruples subservient to their duty as jurors.’

[Citations] Yet such jurors have frequently been

deemed unfit to serve in a capital case. [Citation]

“The critical question, of course, is not how the

phrases employed in this area have been con

strued by courts and commentators. What matters

is how they might be understood— or misunder

stood— by -prospective jurors. Any ‘layman . . .

[might] say he has scruples if he is somewhat un

happy about death sentences . . . [Thus] a general

question as to the presence of . . . reservations [or

scruples] is far from the inquiry which separates

those who would never vote for the ultimate pen

alty from those who would reserve it for the direst

cases.’ Unless a venireman states unambiguously

that he would automatically vote against the im

position of capital punishment no matter what the

trial might reveal, it simply cannot be assumed

that this is his position.” Witherspoon v. Illinois,

supra at 515-16 n. 9.

The inherent ambiguity in almost any question that

asks whether a venireman could return the death pen

alty in a “proper case” is that the venireman might

easily assume that the law classifies certain kinds of

cases as “proper.” The only way that a transcript can

indicate that the venireman did not so interpret the

question is by showing a clear explanation to him that

the jury, in its sole discretion, decides what is a proper

case for imposition of the death penalty. Nothing in

the record indicates that such an explanation was given

to the veniremen excluded in this case.

Veniremen Burns, Peterson and Nakata were ap

parently excluded merely because they stated “strong

1 3 -

feelings” against capital punishment.1 * 3 Venireman Larsen

did not even go that far. The trial judge and the prose

cutor did all his talking on the record for him. And

even Venireman Webber’s statement that he “wouldn’t

be able to sign a death penalty” falls far short of the

“unmistakably clear” test of Witherspoon. This Court’s

opinions in Witherspoon and its progeny can leave no

doubt that these exclusions were in violation of the

Constitution.

In Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1968), this

Court specifically considered whether veniremen might

be excluded “merely by virtue of their statements that

they did not ‘believe in’ capital punishment.” Id. at

483. That opinion makes it abundantly clear that ex

clusion on any such “broader basis” will not pass mus

ter. In Boulder, pains were taken to spell out what

should have been obvious:

1 Statements made by Veniremen Nakata also suggest that he

may have had some reservations about giving the death penalty

in the case before the court, and these reservations may have

been the basis for his exclusion. If this was the basis, his exclu

sion too was in violation of Witherspoon:

“Just as veniremen cannot be excluded for cause on the

ground that they voiced general objections to the death

penalty or expressed conscientious or religious scruples against

its infliction, so too they cannot be excluded for cause simply

because they indicate that there are some kinds of cases

in which they would refuse to recommend capital punish

ment. And a prospective juror cannot be expected to say

in advance of trial whether he would in fact vote for the

extreme penalty in the case before him. The most that can be

demanded of a venireman in this regard is that he be willing

to consider all of the penalties provided by state law, and

that he not be irrevocably committed, before the trial has

begun, to vote against the penalty of death regardless of

the facts and circumstances that might emerge in the course

of the proceedings. If the voir dire testimony in a given

case indicates that veniremen were excluded on any broad

er basis than this, the death sentence cannot be carried out

even if applicable statutory or case law in the relevant

jurisdiction would appear to support only a narrow ground

of exclusion.” Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, at 522 n. 21.

— 14—

“ [I]t is entirely possible that a person who has

‘a fixed opinion against’ or who does not ‘believe

in’ capital punishment might nevertheless be per

fectly able as a juror to abide by existing law—

to follow conscientiously the instructions of a trial

judge and to consider fairly the imposition of the

death sentence in a particular case.” Id. at 483-84.

In Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970), this

Court specifically considered whether a venireman could

be removed because he entertained religious or conscien

tious scruples against imposing the death penalty. Once

again, the patent unconstitutionality of such exclusions

was declared:

“ ‘[A] sentence of death cannot be carried out if

the jury that imposed or recommended it was

chosen by excluding veniremen for cause simply

because they voiced general objections to the death

penalty or expressed conscientious or religious

scruples against its infliction.’ 391 U. S., at 522.

We reaffirmed that doctrine in Boulden v. Hol

man, 394 U. S. 478. As we there observed, it can

not be supposed that once such people take their

oaths as jurors they will be unable ‘to follow con

scientiously the instructions of a trial judge and

to consider fairly the imposition of the death sen

tence in a particular case.’ 394 U. S., at 484.

‘Unless a venireman states unambiguously that he

would automatically vote against the imposition

of capital punishment no matter what the trial

might reveal, it simply cannot be assumed that that

is his position.’ Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, at

516 n. 9.

— 15—

“The most that can be demanded of a venire

man in this regard is that he be willing to con

sider all of the penalties provided by state law,

and that he not be irrevocably committed, be

fore the trial has begun, to vote against the

penalty of death regardless of the facts and cir

cumstances that might emerge in the course of

the proceedings. If the voir dire testimony in a

given case indicates that veniremen were exclud

ed on any broader basis than this, the death

sentence cannot be carried out . . ” Id. at

265-66.

Lastly, the record in this case fails to show with

respect to each of the Witherspoon criteria that the

trial judge made any effort to specifically instruct any

excluded venireman that the law required a juror to

“subordinate his personal views to what he . . . [per

ceives] to be his duty to abide by his oath as a juror and

to obey the law of the State,” Witherspoon v. Illinois,

supra at 514-15 n. 7. Thus, it simply cannot be said that

any of the excluded veniremen made their views “unmis

takably clear.” As this Court noted in Witherspoon:

“Obviously many jurors ‘could, notwithstanding

their conscientious scruples [against capital pun

ishment], return . . . [a] verdict [of death] and

. . . make their scruples subservient to their duty

as jurors.’ ” Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra at 516

n. 9.

Hence, because the trial judge failed to instruct ex

cluded veniremen as to their duty to subordinate their

own personal views to the commands of the law as ex

plained to them by the court, and because the trial

judge failed to clearly determine that the excluded

- 1 6 -

veniremen could not subordinate their personal views

and “abide by the law,” each of the veniremen ex

cluded in this case were removed in violation of

this Court’s pronouncement in Witherspoon and its

progeny.

Nevertheless, in this case the Supreme Court of Illi

nois, relying on its earlier decision in People v. Speck,

41 111. 2d 177, 242 N.E.2d 208 (1968), upheld

the death sentence on the grounds that “ [t]he tenor

of the entire examination . . . was unlike Witherspoon

where the trial court promply removed all who ex

pressed the slightest qualms about capital punishment”,

People v. Moore, supra at 82; 246 N.E.2d at 305

and because “ [i]t is also clear in this case the State

had sufficient peremptory challenges to have eliminated

those prospective jurors eligible to serve under Wither

spoon”. Id, at 84; 246 N.E.2d at 306. Neither factor

referred to by the lower court justified upholding the

death sentence in the face of Witherspoon.

II.

The Question of Whether the Tenor of the Voir Dire

in This Case Differed From That in Witherspoon

Is Irrelevant to the Issue of Whether Veniremen

Were Improperly Excluded.

The Illinois Supreme Court held that the death sen

tence could be imposed in this case because Wither

spoon only applied to cases where veniremen were

hastily and perfunctorily excused for voicing the slight

est qualms regarding the death penalty. People v.

Moore, supra at 83-84; 246 N.E.2d at 305-06. Led by

the Illinois Supreme Court, a number of lower courts

have likewise professed to recognize Witherspoon’s tests,

but have proceeded to avoid applying them.

The leading case is People v. Speck, supra. In that

case the Illinois Supreme Court conceded that as

17

many as 50 veniremen had been excused “because they

stated that they had conscientious scruples concerning

the death penalty without stating that they would never

impose or consider imposing it.” Id. at 213; 242 N.E.2d

at 227. Although clearly in violation of Witherspoon’s

requirements, the Illinois Court upheld the imposition

on the sentence on the grounds that

“. . . the tone of the proceedings here indicate a

sincere desire on the part of the prosecutor and

the court (although perhaps not shared by the de

fense) to determine the jurors’ qualifications ac

cording to the standard later held acceptable in

Witherspoon.” Id. at 209; 242 N.E.2d at 225.

The emphasis in Speck and later cases on the “tone

of the proceedings” disregards the language and in

tent of Witherspoon. In Speck, Witherspoon, as well

as in the present case, veniremen were excused for voic

ing mere general objections to the death penalty. In

Witherspoon this Court said:

“The most that can be demanded of a venireman

in this regard is that he be willing to consider

all of the penalties provided by state law, and

that he not be irrevocably committed, before the

trial has begun, to vote against the penalty of

death regardless of the facts and circumstances

that might emerge in the course of the proceed

ings. If the voir dire testimony in a given case

indicates that veniremen were excluded on any

broader basis than this, the death sentence cannot

be carried out. . . .” Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra

at 516 n. 9.

On June 28, 1971, this Court reversed the death sen

tence in Speck. Just as the death sentences in Wither

— 18—

spoon and Speck have been reversed, so too must the

death sentence in this case be reversed.

III.

The Availability of Peremptory Challenges to the State

Does Not Render Harmless the Improper Exclusion

of Veniremen Under Witherspoon.

The Illinois Supreme Court also upheld imposition

of the death sentence in this case on the grounds that

the state had sufficient peremptory challenges to have

eliminated those prospective jurors improperly excluded

under Witherspoon,2 This argument was first suggested

in State v. Mathis, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A.2d 20 (1968),

reversed as to judgment imposing death sentence, .........

U.S........... (1971), as a “relevant makeweight:”

“And we think it correct to add that if the

prosecution did not use all its peremptory chal

lenges, that fact may be a relevant makeweight,

for it is not unreasonale to assume that the re

maining challenges would have been used, had the

trial court ruled against the State on its objection

to a specific juror. Here the State used only 7 of

its 12 peremptory challenges.” Id. at 251, 245 A.

2d at 27.

This argument would better be characterized as an ir

relevant makeweight. It is purely conjectural whether

the State would have used its peremptory challenges to

exclude the scrupled veniremen. Witherspoon nowhere

mentions the effect of the existence of remaining prose

cution peremptory challenges. When a right as vital as a

2The record disputes this finding. The state used 16 of its 20

peremptory challenges. Had the four remaining challenges been

used, there would still have been at least four and probably eight

improperly excused veniremen. (See Trial Record pp. 146, 162,

242, 269, 277, 281, 303, 322, 329, 342, 346 and 350.)

- 1 9 -

defendant’s right to have a jury which is not unfairly

“stacked” to condemn him to death is at issue, con

jectural suggestions about whether a prosecutor might

have used his peremptory challenges to remove a

scrupled venireman should not be permitted to over

ride a clearly justifiable claim that some veniremen

were excluded for cause in violation of Witherspoon.

This was the decision of the California Supreme

Court in In Re Anderson, 69 Cal.2d 613, 619-20

(1968), wherein Justice Burke dealt with the “remain

ing peremptories” argument as follows:

“The Attorney General also contends that any

error under Witherspoon in excusing for cause

prospective jurors opposed to the death penalty is

nonprejudicial where, as here, the prosecution had

sufficient peremptory challenges to remove all such

jurors. The Attorney General asserts that since the

chances of a jury’s being able to determine the

penalty impartially are diminished if the jury con

tains even one person who is hostile to, or has

reservations concerning the death penalty, it may

be assumed that, if the challenges for cause had

not been available, the prosecutors would have ex

cluded the veniremen in question by way of per

emptory challenge; that a prosecutor may constitu

tionally exercise his peremptory challenges in a

particular case for any purpose he deems proper

(Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 221-222); and

that therefore any error in excluding for cause the

veniremen in question did not affect the composi

tion of the juries at petitioners’ trials and is not a

ground for vacating the death sentences.

“We do not agree. Witherspoon did not discuss the

effect of the existence of remaining peremptory

- 2 0 -

challenges of the prosecution, but the broad lan

guage of the opinion establishes without doubt that

in no case can a defendant be put to death where

a venireman was excused for cause solely on the

ground he was conscientiously opposed to the

death penalty. According to our understanding of

Witherspoon, reversal is automatically required if

a venireman was improperly excused for cause on

the basis of his opposition to the death penalty.

It may be noted that in Witherspoon the defense

had three remaining peremptory challenges when

it accepted the jury, but that fact was not viewed

as showing that the jurors who were impaneled

were impartial and that therefore no harm re

sulted from improperly excusing for cause some

prospective jurors. Furthermore, in arguing that

it may be assumed that the prosecutor would

have used his peremptory challenges to remove

veniremen who under Witherspoon were improperly

excused for cause, the Attorney General bases

his argument on a concept of an impartial jury

that is in conflict with the majority opinion in '

Witherspoon. Under the view of the Witherspoon

majority a jury from which all prospective jurors

opposed the death penalty have been excluded is

not an impartial jury but rather constitutes a ‘hang

ing jury,’ one that is ‘uncommonly willing to con

demn a man to die,’ and one that ‘cannot speak

for the community’ but ‘can speak only for a

distinct and dwindling minority.’ We cannot en

gage in conjecture that the prosecutor would have

used his peremptory challenges to excuse all such

jurors.”

Conclusion.

As this Court has repeatedly recognized, the selec

tion of a jury in any case, and particularly in a capital

case, is of critical importance. Cases like Speck and

Mathis indicate that lower courts have resisted the

thoroughgoing application of Witherspoon which this

Court intended. The most effective way to achieve such

application is for this Court to specifically state that the

improper exclusion of even one juror under Wither

spoon will result in reversal of the death sentence.

There is no room for a de minimus doctrine regarding

selection of a jury in a capital case. Every capital de

fendant should be entitled to a jury from which no

prospective jurors were excluded for cause as a result

of their general objections to the death penalty.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G r ee n b e r g ,

J am es M. N a brit , III,

J ack H im m e l s t e in ,

E lain e R. J o n es ,

M ary L ynn W a lk er ,

10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030,

New York, New York 10019,

A n th o n y G. A m sterd a m ,

School of Law,

Stanford University,

Stanford, California,

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and National Office for the

Rights of the Indigent.

Of Counsel:

R ichard J. St o n e ,

Stuart P. T o bism an .

- 2 1 -

APPENDIX.

Excerpts From the Record on Voir Dire Examination.

Page of

Record

57 Prospective jurors sworn to answer questions.

116 MALACHY BURNS, prospective juror:

117 Q. I see. Do you know of any reason why you

cannot be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. I have a strong feeling against capital

punishment, Judge.

Q. I see. And do you think that that feeling

is such as would influence your judgment in this

case?

A. It very well might.

The Court: What about it gentlemen? Mr.

Horka, Mr. Mack.

118 Mr. Mack: Well, Judge,—

The Court: You may be excused.

Mr. Horka: Judge, he said it might or could.

He hasn’t made up his mind yet.

The Court: You may be excused. Step down,

please.

Mr. Mack: For cause?

The Court: For cause, yes.

118 ESTHER BYRNE, prospective juror:

122 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. Well, ordinarily enough, I take the same

stand as Mr. Byrne. T don’t believe in capital

punishment.

Q. In other words, even if we have a law in

this State to that effect, you wouldn’t believe in it.

anyway?

Page of

Record

■2-

A. No, I don’t, definitely not.

The Court: Very well. That’s your prerogative.

You’re excused for cause.

146 PAUL LARSEN, prospective juror:

147 Q. Do you know of any reason why you can

not be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. Well, I don’t know whether I understand

capital punishment. Is it death for death, an eye

for an eye, a tooth for a tooth?

Q. Listen, in a murder case, the jury has a

148 duty to determine, first, whether the defendant

is guilty or not guilty. You will be given multiple

verdicts in this case. If you decide he is not guilty,

that ends the case. Do you understand?

A. Yes.

Q. If you decide he is guilty of murder, then

you must next determine whether or not you wish

to return a verdict of death. If you so decide on

a verdict of death, you will so indicate in your

verdict. If you have determined the guilt of the

defendant and decide against a verdict of death,

you will return a verdict of guilty and the court

will fix the term of punishment.

Do you understand that?

A. The court, the judge will?

Q. That’s right, that’s right. The law in this

State, in a murder case, allows multiple verdicts.

The first thing you decide is whether he is guilty

or not. If you decide he is not guilty, that ends it.

The jury after finding him guilty, will have to de

cide whether or not they want to inflict the death

penalty. If you decide that you don’t want to in-

— 3—

Page of

Record

flict the death penalty, you will say so and then

the court will fix his punishment but it shall

149 not be death. The court cannot fix the death

penalty unless the jury, having been asked for

it, decides that.

Do you understand that?

A. In other words, when we go back to de

cide the verdict, we can either vote against the

death penalty or for it?

Q. Oh, yes. The first thing that you have to

determine is—

A. And what classifies that, the majority or

they all have to vote the same way?

Q. No majority verdicts on anything in this

State. It has to be the unanimous verdict of the

twelve people on each one of those things, first,

guilt or innocence. After that determination, if it’s

guilt then you go ahead and decide whether you

want to inflict the death penalty or not.

A. Well, sir, I think I have to commit myself.

I believe in the Bible, “Thou shalt not kill.”

Q. The Bible has a lot of things in it.

A. That’s one of the ten commandments.

Q. And I haven’t seen any responsible religious

official who says the Bible admonishes a jury not

to follow the law.

150 A. That might be.

Q. What’s that?

A. That might be.

The Court: I thought that’s the highest thing,

the law of God and then the law of man. But if

that’s your position, then, we will excuse you.

(Prospective juror excused.)

-4-

Page of

Record

LOUIS LORENS, prospective juror:

151 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

152 be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. I do not believe in capital punishment.

The Court: Well, step down.

(Prospective juror excused.)

210 KATHERINE KRISTOCK, prospective juror:

212 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. No.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscientious

scruples against the infliction of the death penalty

in a proper case?

A. I ’m afraid I do. I don’t believe in capital

punishment.

The Court: Step down, please.

(Prospective juror excused.)

221 ISAAC NAKATA, prospective juror:

222 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. No.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscientious

scruples against the infliction of the death penalty

in a proper case?

A. I have a very strong prejudice against the

use of capital punishment.

Q. I see.

A. Except in very limited area.

O. Well, the law of this State prescribes

capital punishment in certain types of cases,

223 and murder is one of them. Now, as I stated

before, the jury will have to determine whether

— 5—

Page of

Record

the defendant is guilty or not guilty of the charge

that has been made against him.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Then the jury will also have to consider

whether it’s a proper case for the death penalty.

Now, do you believe that the State could present

a case proper for the death penalty?

A. Yes, sir.

228 A. That’s the reason why I would like to give

my reasoning right now, before I perjure myself

about that personally, because I can’t go all the

way on capital punishment.

Q You can’t go all the way?

A. No.

Q. Where do you sop?

A. It depends on the kind of crime it is and

the evidence presented for it.

Q. Oh, that’s all we are asking you to do.

A. Well, it seems to me, from the statements

made by the prosecuting attorney, that he is going

to ask for the death penalty, so, in view of that

fact, I think I should disqualify myself.

Q. If he asks for it, it doesn’t mean that you

have to give it to him.

A. Of course, that’s true, too. But, at the same

time, though, I mean, I wouldn’t be applying the

law, as he stated it, you see, upon his presentation

of the evidence, and all that, so I don’t think I

would be fair to the court or to the rest of the

jurors by my being on the jury.

The Court: Step down, then if you don’t think

6—

Page of

Record

229 you can be fair. I’m not going to ask you to try

any further. The only question is, we want you

to be fair and impartial.

(Prospective juror excused.)

248 MARIAN PETERSON, prospective juror:

250 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. No.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscien

tious scruples against the infliction of the death

penalty in a proper case?

A. Yes, I have very strong convictions against

capital punishment.

The Court: Step down, please.

(Prospective juror excused.)

NEBRASKA PETTY, prospective juror:

252 Q. Do you know of any reason why you can

not be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. No, sir.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscientious

scruples against the infliction of a death penalty

in a proper case?

A. I do.

The Court: Step down.

(Prospective juror excused.)

308 JACQUELINE B. THREATT, prospective juror:

309 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. No.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscientious

scruples against the infliction of the death penalty

in a proper case?

Page of

Record

A. Yes, 1 do.

Q. You do: What do you mean?

A. I don’t believe in capital punishment.

Q. Say that again.

A. I feel very strongly against capital punish

ment.

The Court: Step down, please. Call another juror.

325 ALBERT WEBBER, prospective juror:

Q. The gentleman on the end, your name, sir?

A. Albert Webber. Your Honor, I wouldn’t be

able to sign a death penalty.

Q. You wouldn’t?

A. No, sir.

The Court: All right. Step down, Mr. Webber.

350 MARY GORSKI, prospective juror:

352 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

A. No, sir.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscientious

scruples against the infliction of the death penalty

in a proper case?

A. Yes, I do, your Honor.

The Court: All right, step down.

365 ANNA L. HOHNWALD, prospective juror:

366 Q. Do you know of any reason why you cannot

be a fair and impartial juror in this case?

a. No, sir.

Q. Do you have any religious or conscientious

scruples against the infliction of the death penalty

in a proper case?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Step down, please.

Service of the within and receipt of

thereof is hereby admitted this................

of September A.D. 1971.

a copy

......day