Smith v Allwright Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

April 3, 1944

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Allwright Brief for Petitioner, 1944. a41a7ec1-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2796369-1739-4acb-a954-1903b3e8beca/smith-v-allwright-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

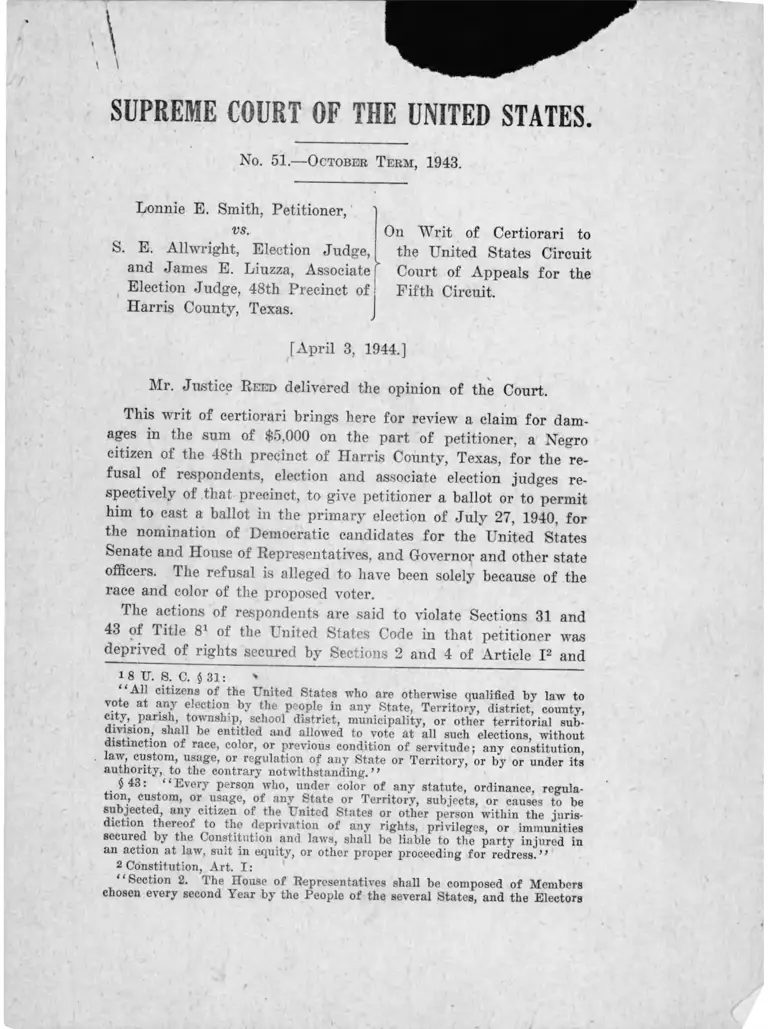

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 51.— October T erm , 1943.

Lonnie B. Smith, Petitioner,

vs.

S. E. Allwright, Election Judge,

and James E. Liuzza, Associate ”

Election Judge, 48th Precinct of

Harris County, Texas.

On Writ of Certiorari to

the United States Circuit

Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit.

[April 3, 1944.]

Mr. Justice R eed delivered the opinion of the Court.

This writ of certiorari brings here for review a claim for dam

ages in the sum of $5,000 on the part of petitioner, a Negro

citizen of the 48th precinct of Harris County, Texas, for the re

fusal of respondents, election and associate election judges re

spectively of that precinct, to give petitioner a ballot or to permit

him to cast a ballot in the primary election of July 27, 1940, for

the nomination of Democratic candidates for the United States

Senate and House of Representatives, and Governor and other state

officers. The refusal is alleged to have been solely because of the

race and color of the proposed voter.

The actions of respondents are said to violate Sections 31 and

43 of Title 81 of the United States Code in that petitioner was

deprived of rights secured by Sections 2 and 4 of Article I2 and

1 8 U. 8. C. $ 31: ' _ '

All citizens of the United States who are otherwise qualified by law to

vote at any election by the people in any State, Territory, district, county,

city, parish, township, school district, municipality, or other territorial sub-

dmsion, shall be entitled and allowed to vote at all such elections, without

distinction or race, color, or previous condition of servitude; any constitution,

law custom, usage, or regulation of any State or Territory, or by or under its

authority, to the contrary notwithstanding. ’ ’

$43: Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regula

tion, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, subjects, or causes to be

subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the juris-

diction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities

secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in

an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress. ”

2 Constitution, Art. I :

“ Section 2. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members

chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors

2 2

the Fourteenth, Fifteenth and Seventeenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution.3 The suit was filed in the District

Court of the United States for the Southern District of Texas,

which had jurisdiction under Judicial Code Section 24, subsec

tion 14.4

The District Court denied the relief sought and the Circuit

Court of Appeals quite properly affirmed its action on the au

thority of Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45.5 We granted the

petition for certiorari to resolve a claimed inconsistency between

the decision in the Grovey case and that of United States v. Classic,

313 U. S. 299. 319 U. S. 738.

The State of Texas by its Constitution and statutes provides

that every person, if certain other requirements are met which

are not here in issue, qualified by residence in the district or

county “ shall be deemed a qualified elector.” Constitution of

Texas, Article VI, Section 2; Vernon’s Civil Statutes (1939 ed.),

Article 2955. Primary elections for United States Senators, Con

gressmen and state officers are provided for by Chapters Twelve

and Thirteen of the statutes. Under these chapters, the Demo

cratic Party was required to hold the primary which was the

in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most

numerous Branch of the State Legislature.”

“ Section 4. The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Sen

ators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature

thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regu

lations, except as to the Places of cliusing Senators. ’ ’

3 Constitution:

Article XIV. “ Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United

States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce

any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the

United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws.”

Article XV. “ Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to

vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State

on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

“ Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by ap

propriate legislation.”

Article XVII. 1 ‘ The Senate of the United States shall be composed of

two Senators from each state, elected by the people thereof, for six years;

and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each state shall have

the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the

state legislatures.”

4 A declaratory judgment also was sought as to the constitutionality of the

denial of the ballot. The judgment entered declared the denial was consti

tutional. This phase of the case is not considered further as the decision on

the merits determines the legality of the action of the respondents.

5 Smith v. Allwright, 131 F. 2d 593.

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

occasion of the alleged wrong to petitioner. A summary of the

state statutes regulating primaries appears in the footnote.6

These nominations are to be made by the qualified voters of the

party. Art. 3101.

51

3 Smith vs. Allwriglit et al. 3

DearWrnm6̂ ‘ t whieh*I*e state controls the primary election machinery ap

pears from the Texas statutes, as follows: Art. 3118, Vernon’s Texas Stat-

tes, provides for the election of a county chairman for each party holding a

o/The^ua^tv’ 6 qu.aljfk’d voters of the wh°le county,” and of one member

+-P 8'.county executive committee by the “ qualified voters of their

m m T l m V pr' “ “ct9-’ ’ These officers have direct charge of the pri-

mary. There is m addition statutory provision for a party convention: the

, rs each precinct choose delegates to a county convention, and the latter

Mttoritr to^riinn,1 th ' ‘f 4!6 conve“ ! ion' Art- 3134- The state convention has

1939 Sunn w ? te e« Cutlve committee and its chairman. Art. 3139,

tCandldates for offices to be filled by election are required to be

votes ^ t t , 3 Tj:!mary election if the nominating party cast over 100 000

votes at the preceding general election. Art. 3101. The date of the primary

a n d ^ no c a n d S in J" ly ’ a mâ » -qu^ed f t n o X a £ £n° candidate receives a majority, a run-off primary between the two

310a Voundmgi candldates is held on the fourth Saturday in August Art

oppositf party P Art 6 ," ’lthln a hlmdred yards of those used by the

presiding luE ’e tfc ° ' • ? ac* Precmct P’mnary is to be conducted 'by a

R J ® d “f judge and the assistants he names. These officials are selected bv

by tfce

s»ss a s rtrW ” in<ir :,t *>*•-

cw ?»a SEFZsmcstizsi

onAthe8' primary1 iballo/ for ̂ fe^eraT's7ate dUtrict*3™ 8 ° f pro^ iag a place

SSSS ve0o ™ 'i.„Teh” = - • » 3 ST22g

B M V J t

posts, such as the offices of district jud*e“ W e

The Democratic Party of Texas is held by the Supreme Court

o that state to be a “ voluntary association,” Bell v. Hill, 123

lex . 531, 534, protected by Section 27 of the Bill of Rights, Art.

, Constitution of Texas, from interference by the state except

51

4 Smith vs. Allwright et al. 4

J o l ScountLa fee8r\Prree1 xed b ; A r t ^ m l d * ” ^ ^ 3nd for

3n9P'andUAPrte3120 authorize^theuseolfoUng booths ^

rails, prepared for the general election “ fnf t ? 7 ba,.lot boxes and guard

nominating by primary elpctinn + w + 01 * 16 organized political party

the preceding general election ” Vhp 1 ° T ?ne luadrcd thousand votes at

t T n n Thers by

“ d ' P - e ao£ththePrS

25 cover the making Sf returns to t l " teIeCtlJ0na; Art. 3122. Arts. 3123-

of the result by the county committee. By Art SlLT6 a^statTdiand Ca" VaS3 required of the state executive t ■“■“ • 3127, a statewide canvass is

similar canvass bv the state convention .•?£ State and dlstrict officers and a

vided by Art 3138 The ,. ’ '''i l respect to state officers is pro-

' county yc,erks, Z Z ^ ^ t0 the31^7 T3on *. l, ie ornceis to the Secretary of State Art<s 3197

Art ’ 3128 fgifsuuu0^ 7 * M s 7 ° *° be Tet™ eA to the cotnty clerk’

county clerk must p^Xl’ish^he” r e L r sC°Utlty 0„0muiittee, the

is made within five days the name of th ' • ’ 1 . “ / SuPP- If no objection

official ballot by the county clert A t ,0 be Placed 011 the

2984, 2992, 2996. Arts 3146 53 mao V ’ 194? Supp. Cf. Arts. 2978,

The state district courts have exclusive n ^ ’’ P™'’1?6, for election contests,

of Civil Appeals has appellate iurisdTc I n ^ f P^diebicn, and the Court

ized to issue writs of mandamus to ronni™ .‘e C0llrts are als0 author-

men, and primary officers to discharge the , J:xec.utlve committees, committee-

3142 ; cf. Art, 3124. U'sciiarge the duties imposed by the statute. Art.

of''the r^pectivedpartiese<̂ c o dumn°for ̂ ndp ,ccdu®?a8 for the nominees

column for such names as the voters^care to C“?d ^ 7 ’ and a blank

names of nominees of a mrtv to wrlte ln- Arts. 2978, 2980. The

preceding general election may no^ be^rinted^n11̂ 10^ 0]0̂ V° teS at the ,ast

chosen at a primary election Art 2978 p ! ^ e4baII° unless they were

nominees may have their r» • +.’ f *,v Candidates who are not party

3159-62. This' sections reoufre * 7 hf ° l with Arts

State, county judge, or mayor for in A 10na t® he filed with the Secretary of

respectively/ The applications’ must h e .and dlstnct> county, and city ofliccs,

her of from one to five per cenTof the 7 7 t by f alified voters to the num-

depending on the office. * Bach signer must t«k«°»8t a(V w Preceding election,

did not participate in a primary -d „ , .? n oafh to the effect that he

was nominated. While this reauirnnent , caadldat® f°r the office in question

has voted in the party primary t!„,„ baS been udd to preclude one who

Westerman v. Mims,‘ 111 Tex °9 2 2 7 s V m th® bai Iot as an “ dependent,

mott, 277 8 W Pis t r>\„ V “ 1 ’ v' 118: see Cunningham v. McDer-

elected at the Jen al f i i o W i wisupra. election bj a write-in vote. Cunningham v. McDermott,

portant respect”^ Art 3139' 1939 sipT^th by f 16 State in one other im‘

a platform of priniiples, but' ’its' su b m it,, 7 \h conventiPn can announce

to party advocacy of specific le g is C r irt. iS a

5 5

In the interest of fair methods and a fair expression by their

memhers of their preferences in the selection of their nominees,

the state may regulate such elections by proper laws.” P. 545̂

That court stated further:

“ Since the right to organize and maintain a political party is

one guaranteed by the Bill of Rights of this State, it necessarily

follows that every privilege essential or reasonably appropriate

to the exercise of that, right is likewise guaranteed,— including,

of course, the privilege of determining the policies of the party

and its membership. Without the privilege of determining the

policy of a political association and its membership, the right to

organize such an association would be a mere mockery. We think

these rights,— that is, the right to determine the membership of

a political party and to determine its policies, of necessity are’

to be exercised by the State Convention of such party, and can

not, under any circumstances, be conferred upon a State or gov

ernmental agency.” P. 546. Cf. Waples v. Marrast, 108 Texas 5.

The Democratic party on May 24, 1932, in a State Convention

adopted the following resolution, which has not since been

“ amended, abrogated, annulled or avoided” :

“ Be it resolved that all white citizens of the State of Texas who

are qualified to vote under the Constitution and laws of the State

shall be eligible to membership in the Democratic party and, as

such, entitled to participate in its deliberations.”

It was by virtue of this resolution that the respondents refused

to permit the petitioner to vote.

Texas is free to conduct her elections and limit her electorate

as she may deem wise, save only as her action may be affected by

the prohibitions of the United States Constitution or in conflict

with powers delegated to and exercised by the National Govern

ment.7 The Fourteenth Amendment forbids a state from making

or enforcing any law which abridges the privileges or immunities

of citizens of the United States and the Fifteenth Amendment

specifically interdicts any denial or abridgement by a state of the

light of citizens to vote on account of color. Respondents appeared

in the District Court and the Circuit Court of Appeals and defended

on the ground that the Democratic party of Texas is a voluntary

organization with members banded together for the purpose of select

ing individuals of the group representing the common political be-

liefs as candidates in the general election. As such a voluntary or-

VCf. Parker v. Brown, 317 U. S. 341, 359-60.

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

6

ganization, it was claimed, the Democratic party is free to select its

own membership and limit to whites participation in the party

primary. Such action, the answer asserted, does not violate the

Fourteenth, Fifteenth or Seventeenth Amendment as officers of

government cannot be chosen at primaries and the Amendments

are applicable only to general elections where governmental officers

are actually elected. Primaries, it is said, are political party

affairs, handled by party not governmental officers. No appear

ance for respondents is made in this Court. Arguments presented

here by the Attorney General of Texas and the Chairman of the

State Democratic Executive Committee of Texas, as amici curiae,

urged substantially the same grounds as those advanced by the

respondents.

Ihe right of a Negro to vote in the Texas primary has been

considered heretofore by this Court. The first case was Nixon v.

Herndon, 273 U. S. 536. At that time, 1924, the Texas statute,

Art. 3093a, afterwards numbered Art. 3107 (Rev. Stat. 1925)

declared in no event shall a Negro be eligible to participate in

a Democratic Party primary election in the State of Texas.”

Nixon was retused the right to vote in a Democratic primary and

brought a suit for damages against the election officers under

R. S. § 1979 and 2004, the present sections 43 and 31 of Title 8,

U. S. C., respectively. It was urged to this Court that the denial

of the franchise to Nixon violated his Constitutional rights under

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Without considera

tion of the Fifteenth, this Court held that the action of Texas

in denying the ballot to Negroes by statute was in violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and re

versed the dismissal of the suit.

The legislature of Texas reenacted the article but gave the -

Slate Executive Committee of a party the power to prescribe the

qualifications of its members for voting or other participation.

This article remains in the statutes. The State Executive Com

mittee of the Democratic party adopted a resolution that white

Democrats and none other might participate in the primaries of

that party. Nixon was refused again the privilege of voting in

a primary and again brought suit for damages by virtue of Sec

tion 31, Title 8 U. S. C. This Court again reversed the dismissal

of the suit for the reason that the Committee action was deemed

to be State action and invalid as discriminatory under the Four-

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al. 6

7 7

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

teenth Amendment. The test was said to be whether the Com

mittee operated as representative of the State in the discharge of

the State’s authority. Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73. The ques

tion of the inherent power of a political party in Texas “ without

restraint by any law to determine its own membership” was left

open. Id., 84-85.

In Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45, this Court had before it

another suit for damages for the refusal in a primary of a county

clerk, a Texas officer with only public functions to perform, to

furnish petitioner, a Negro, an absentee ballot. The refusal was

solely on the ground of race. This case differed from Nixon v.

Condon, supra, in that a state convention of the Democratic party

had passed the resolution of May 24, 1932, hereinbefore quoted.

It was decided that the determination by the state convention of

the membership of the Democratic party made a significant change

from a determination by the Executive Committee. The former

was party action, voluntary in character. The latter, as had been

held in the Condon case, was action by authority of the State.

The managers of the primary election were therefore declared not

to be state officials in such sense that their action was state action.

A state convention of a party was said not to be an organ of the

state. This Court went on to announce that to deny a vote in a

primary was a mere refusal of party membership with which “ the

state need have no concern,” loc. cit. at 55, while for a state to

deny a vote in a general election on the ground of race or color

violated the Constitution. Consequently, there was found no

ground for holding that the county clerk’s refusal of a ballot be

cause of racial ineligibility for party membership denied the peti

tioner any right under the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments.

Since Grovey v. Townsend and prior to the present suit, no

case from Texas involving primary elections has been before this

Court. We did decide, however, United States v. Classic, 313

U. S. 299. We there held that Section 4 of Article I of the Con

stitution authorized Congress to regulate primary as well as

general elections, 313 U. S. at 316, 317, “ where the primary is

by law made an integral part of the election machinery.” 313

U. S. at 318. Consequently, in the Classic case, we upheld the

applicability to frauds in a Louisiana primary of §§19 and 20

of the Criminal Code. Thereby corrupt acts of election officers

8

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

were subjected to Congressional sanctions because that body had

power to protect rights of Federal suffrage secured by the Con

stitution in primary as in general elections. 313 U. S. at 323

This decision depended, too, on the determination that under the

Louisiana statutes the primary was a part of the procedure for

e mice of b ederal officials. By this decision the doubt as to

whether or not such primaries were a part of “ elections” subject

to Federal control, which had remained unanswered since New

berry v. United States, 256 U. S. 232, was erased. The Nixon

Cases were decided under the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment without a determination of the status of the

primary as a part of the electoral process. The exclusion of

Negroes from the primaries by action of the State was held in

valid under that Amendment. The fusing by the Classic case of

the primary and general elections into a single instrumentality

or choice of officers has a definite bearing on the permissibility

under the Constitution of excluding Negroes from primaries. This

is not to say that the Classic case cuts directly into the rationale

of Grovey v. Townsend. This latter case was not mentioned in

tlie opinion. Classic bears upon Grovey v. Townsend not because

exclusion of Negroes from primaries is any more or less state

action by reason of the unitary character of the electoral process

but because the recognition of the place of the primary in the

electoral scheme makes clear that state delegation to a party of

the power to fix the qualifications of primary elections is delega

tion of a state function that may make the party’s action the action

ot the state. When Grovey v. Townsend was written, the Court

ooked upon the denial of a vote in a primary as a mere refusal

by a party of party membership. 295 U. S. at 55. As the Louisiana

statutes for holding primaries are similar to those of Texas our

ru mg m Classic as to the unitary character of the electoral’ pro

cess calls for a reexamination as to whether or not the exclusion

o Negroes from a Texas party primary was state action.

he statutes of Texas relating to primaries and the resolution

of the Democratic party of Texas extending the privileges of mem-

ership to white citizens only are the same in substance and effect

oday as they were when Grovey v. Townsend was decided by a

unanimous Court. The question as to whether the exclusionary

action of the party was the action of the State persists as the

eterminative factor. In again entering upon consideration of

9

the inference to be drawn as to state action from a substantially

similar factual situation, it should be noted that Grovey v. Town

send upheld exclusion of Negroes from primaries through the de

nial of party membership by a party convention. A few years

before this Court refused approval of exclusion by the State Execu

tive Committee of the party. A different result was reached on

the theory that the Committee action was state authorized and

the Convention action was unfettered by statutory control. Such

a variation in the result from so slight a change in form influences

us to consider anew the legal validity of the distinction which has

resulted in barring Negroes from participating in the nominations

of candidates of the Democratic party in Texas. Other precedents

of this Court forbid the abridgement of the right to vote. United

States v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214, 217; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370,

388; Gmnn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 361; Myers v. Ander

son, 238 U. S. 368, 379; Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268.

It may now be taken as a postulate that the right to vote in

such a primary for the nomination of candidates without dis

crimination by the State, like the right to vote in a general elec

tion, is a right secured by the Constitution. United States v.

Classic, 313 U. S. at 314; Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368;

Ex parte Yarborough, 110 U. S. 651, 663 et seq. By the terms of

the Fifteenth Amendment that right may not be abridged by any

state on account of race. Under our Constitution, the great privi

lege of choosing his rulers may not be denied a man by the State

because of his color.

We are thus brought to an examination of the qualifications for

Democratic primary electors in Texas, to determine whether state

action or private action has excluded Negroes from participation.

Despite Texas’ decision that the exclusion is produced by private

or party action, Bell v. Hill, supra, Federal courts must for them

selves appraise the facts leading to that conclusion. It is only

by the performance of this obligation that a final and uniform

interpretation can be given to the Constitution, the “ supreme Law

of the Land.” Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73, 88; Standard Oil

Co. v. Johnson, 316 U. S. 481, 483; Bridges v. California, 314

U. S. 252; Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219, 238; Union Pacific

R. Co. v. United States, 313 U. S. 450, 467; Drivers Union v.

Meadowmoor Co., 312 U. S. 287, 294; Chambers v. Florida, 309

U. S. 227, 228. I exas requires electors in a primary to pay a

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al. 9

10

poll tax. Every person who does so pay and who has the quali

fications of age and residence is an acceptable voter for the pri

mary. Art. 29o5. As appears above in the summary of the

statutory provisions set out in note 6, Texas requires by the law

the election of the county officers of a party. These compose

the county executive committee. The county chairmen so selected

are members of the district executive committee and choose the

chairman for the district. Precinct primary election officers are

named by the county executive committee. Statutes provide for

the election by the voters of precinct delegates to the county con

vention of a party and the selection of delegates to the district

and state conventions by the county convention. The state con

vention selects the state executive committee. No convention may

place in platform or resolution any demand for specific legislation

without endorsement of such legislation by the voters in a pri

mary. Texas thus directs the selection of all party officers.

Primary elections are conducted by the party under state statu

tory authority. The county executive committee selects precinct

election officials and the county, district or state executive com

mittees, respectively, canvass the returns. These party com

mittees or the state convention certify the party’s candidates to

the appropriate officers for inclusion on the official ballot for the

general election. No name which has not been so certified may ap

pear upon the ballot for the general election as a candidate of a

political party. No other name may be printed on the ballot

which has not been placed in nomination by qualified voters who

must take oath that they did not participate in a primary for

the selection of a candidate for the office for which the nomina

tion is made.

The state courts are given exclusive original jurisdiction of

contested elections and of mandamus proceedings to compel party

officers to perform their statutory duties.

We think that this statutory system for the selection of party

nominees for inclusion on the general election ballot makes the

party which is required to follow these legislative directions an

agency of the state in so far as it determines the participants in

a piimary election. The party takes its character as a state agency

from the duties imposed upon it by state statutes; the duties do

not become matters of private law because they are performed by a

political party. The plan of the Texas primary follows substan

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al. 10

11 11

tially that of Louisiana, with the exception that in Louisiana the

state pays the cost of the primary while Texas assesses the cost

against candidates. In numerous instances, the Texas statutes fix

or limit the fees to be charged. Whether paid directly by the state

or through state requirements, it is state action which compels.

When primaries become a part of the machinery for choosing of

ficials, state and national, as they have here, the same tests to deter

mine the character of discrimination or abridgement should be ap

plied to the primary as are applied to the general election. If the

state requires a certain electoral procedure, prescribes a general

election ballot made up of party nominees so chosen and limits the

choice of the electorate in general elections for state offices, prac

tically speaking, to those whose names appear on such a ballot, it

endorses, adopts and enforces the discrimination against Negroes,

practiced by a party entrusted by Texas law with the determination

of the qualifications of participants in the primary. This is state

action within the meaning of the Fifteenth Amendment. Guinn v.

United States, 238 U. S. 347, 362.

Hie United States is a constitutional democracy. Its organic

law grants to all citizens a right to participate in the choice of

elected officials without restriction by any state because of race.

This grant to the people of the opportunity for choice is not to

be nullified by a state through casting its electoral process in a

form which permits a private organization to practice racial dis

crimination in the election. Constitutional rights would be of

little value if they could be thus indirectly denied. Lane v Wilson

307 U. S. 268, 275. ’

The privilege of membership in a party may be, as this Court

said in Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45, 55, no concern of a

state. But when, as here, that privilege is also the essential quali-1

fication for voting in a primary to select nominees for a general j

election, the state makes the action of the party the action of the'

state. In reaching this conclusion we are not unmindful of the

desirability of continuity of decision in constitutional questions.8

However, when convinced of former error, this Court has never

felt constrained to follow precedent. In constitutional questions,

where correction depends upon amendment and not upon legis-

lative action this Court throughout its history has freely exercised

8 Cf- Pollock v. Farmers Loan & Trust Co., 157 U. S. 429, 652.

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

12 12

its power to reexamine the basis of its constitutional decisions.

This has long been accepted practice,9 and this practice has con

tinued to this day.10 This is particularly true when the decision

believed erroneous is the application of a constitutional principle

rather than an interpretation of the Constitution to extract the

principle itself.11 Here we are applying, contrary to the recent

decision in Grovey v. Townsend, the well established principle of

the F ifteenth Amendment, forbidding the abridgement by a state

of a citizen’s right to vote. Grovey v. Townsend is overruled.

Judgment reversed.

Mr. Justice F rankfurter concurs in the result.

51

Smith vs. Allwright et al.

Ga0sSCo,C2l5 dissentillg “ Burnet *. Coronado Oil &

See e. g , United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100, unanimously overruling

Hammer v Dagenhart, 247 U. S. 251; California v. Thompson, 313 U. S 10if

unanimously overruling DiSanto v. Pennsylvania, 273 U. S. 34; West Coast

261teu Cs ' 3°A°rU'iS' a79’ overn,linf? Adkins v. Children’s Hospital,, 1 Ul o-o (and see Morehead v. New York rx re], T'paldo 298 IT S 5871

verfnTn8pthe; land’ n ** Reynolds and Butler dissentingi Hel-

257 U S 50°1 TnT RC°rPt 3° p U‘ S- 37G> overruling Gillespie v. Oklahoma, 207 U. 8. o01 and Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U. S. 393- Brie

. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64, overruling Swift v. Tyson 16 Pet 1

O ’Keeffe 306 U a| d4^ eBeynolf.S d;“ “ ting ; Graves v. New York ex ' rei

y i efe’ , G U- s - 466> overruling Collector v. Day, 11 Wall. 113, and New

dissenting'’ vv'^T’ 2"i . U’ S- 401’ Jllsticcs Butler and McReynoldsdissenting O Halley v. Woodrough, 307 U. S. 277, overruling Miles v. Graham,

2b8 U. 8. 501, Justice Butler dissenting; Madden v. Kentucky 309 U 8 83

Z I S m i?C hief f 7 ey’ 296,U- 8 4°*> •T" G«OS Roberts and^McReynohls

v Hallock 309 II S mo , c° T urrinff 0,1 other grounds; Helvering

296 U S 39 L Y r , ’ ° Z Trr ? ?Tel.verln« *■ St- Louis Union Trust Co,

p h ; b' J 9 d Becker v- St. Louis Union Trust Co., 296 U. S 48 Justices

Robeits and McReynolds dissenting and Chief Justice Hughes concurring on

other grounds; Nye v. United States, 313 U. S. 33 overruling ToWln

paper Co. v. United States, 247 U. S. 402, Chief Justice’Hughes and Justices Stone

o v l Y t Cr p Y n S ing0 1Ar ab,UU?^'- & 314 U. S 1 uSnlmously

298 U S to w f 277 U' S' 218 and Graves *. Texas Co,

f Haddocf 20r Y as"%r'o rrt 1 Car°Tn;:’ 317 U- S’ 287’ overruling Haddock v. narldock, 201 U. S. o62, Justices Jackson and Murphy dissenting- State

Uf Si 174’ F U N“ gB an fvMaine, ,84 to S. 312, Justices Jackson and Roberts dissenting- Board of

S E 103nl O v T ^ Z 3] 9 ti S- ^ o v e rru lin g Minersville School DiT r L I .

1 U’ S- 586’ Justlces Frankfurter, Roberts and Reed dissenting,

tit. Dissent in Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co, 285 U. S. 393 at 410.

* ^