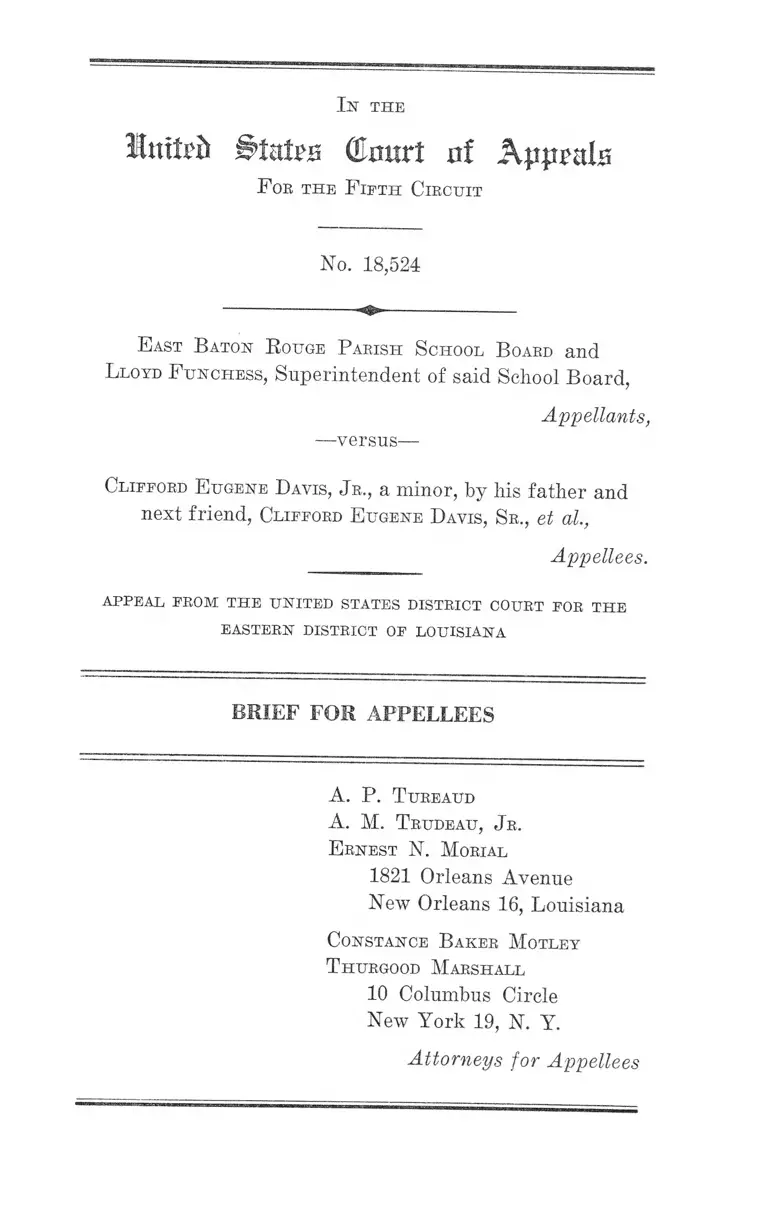

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis Brief for Appellees, 1960. 789aae61-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2ec2f22-69f1-404c-a179-2f0b4bc28ede/east-baton-rouge-parish-school-board-v-davis-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

llmUh Btntm (Emirt rtf Kppmlz

F oe the F ifth Circuit

Isr th e

No. 18,524

E ast B aton R ouge P arish School B oard and

L loyd F unchess, Superintendent of said School Board,

—versus—

Appellants,

Clifford E ugene Davis, J r., a minor, by Ms father and

next friend, Clifford E ugene Davis, Sr., et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. T rudeau, J r.

E rnest N. Morial

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

Constance B aker Motley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

In th e

lmtr& Bttitm (Emtrt rtf kppralB

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 18,524

E ast B aton B ouge P arish School B oard and

L loyd F unchess, Superintendent of said School Board,

—versus—

Appellants,

Clifford E ugene Davis, J r., a minor, by his father and

next friend, Clifford E ugene Davis, Sr., et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement o f the Case

Appellants’ Statement of the Case is supplemented by

the following facts appearing in the record on appeal which

appellees believe necessary to a full and proper statement

of this case:

On May 25, 1960, an injunction order was entered by the

court below in this case.

This injunctive order enjoins the appellant East Baton

Bouge Parish School Board and the appellant Superinten

2

dent of Schools from “ requiring segregation of the races

in any school under their supervision, and from engaging

in any and all action which limits or affects the admission

to, attendance in, or education of plaintiffs or any other

Negro child similarly situated in schools under [their]

jurisdiction, on the basis of race and color, from and after

such time as may be necessary to make arrangements for

admission of children to such schools on a racially non-

discriminatory basis with all deliberate speed, as required

by the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, . . . ” (R. 171-172).

The court below retained jurisdiction of this cause for

the purpose of entering such further orders or granting

such further relief as may be necessary to bring about

compliance with its decree (R. 172).

The foregoing order was entered approximately four

years and three months after February 29, 1956, the date

on which the complaint was filed (R. 2).

The complaint alleged that various statutes of the State

of Louisiana and the State Constitution required racial

segregation in the public schools and prayed for injunctive

relief against the enforcement of same (R. 9-14).

No answer was ever filed by appellants during the four

year period in which this case pended in the court below.

The record shows that prior to the filing of the complaint,

Negro citizens of East Baton Rouge Parish, including some

of these appellees, petitioned the appellant Board and

Superintendent to comply with the decisions of the United

States Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases (R.

58-59). This petition was presented to the Board at its

meeting on November 10, 1955 (R. 55). At that meeting,

the Board adopted the following resolution:

3

“Resolved, That the above-mentioned petition be filed

in accordance with the Board’s resolution of August 25,

1955 as follows:

‘Resolved, That, as far as segregation is concerned,

the Board will follow the State ,lawT on the subject’ ”

(R. 56).

Similar petitions to the Board were disposed of in the

same fashion (R. 49).

After the complaint was filed, appellees took the,deposi

tions of Superintendent Funchess on April 24, 1956 (R. 45-

60). He testified as to the receipt of the various desegrega

tion petitions addressed to the Board (R. 47-49), as to the

failure of the Board to take any steps to comply with the

Supreme Court’s decisions in the School Segregation Cases

(R. 50-51), and testified as to his inability to make assign

ments to schools on a nonraeial basis in view of the Board’s

policies (R. 53). This deposition was before the court

below on consideration of plaintiffs’ motion for summary

judgment (R. 167).

Appellants took the depositions of ten of the fourteen

appellees on various dates during April 1956 (R. 62-134).

During the course of these depositions, appellants learned

the identity of each of these adult plaintiffs and the identity

of each of the minor plaintiffs attending schools under

appellants’ jurisdiction on behalf of whom this suit is

brought.

On November 4, 1959, appellees .filed a motion for a sum

mary judgment (R. 141). Five days later, appellants filed

their opposition thereto (R. 146), In their opposition

appellants called the attention of the court below to the

fact that Louisiana had adopted a pupil placement law (Act

259, 1958, R.S. 17:101-110) which is similar to the one

enacted by Alabama and held facially constitutional in the

4

ease of Shuttlesworth v. B’ham Bd. of Ed. (N. D. Ala. 1958),

162 F. Supp. 372, aff’d 358 U. S. 101 (E. 147).

On the same date upon which appellants filed their oppo

sition they also filed two motions to dismiss, a motion for

a more definite statement (E. 148), and a motion to join

the NAACP as an indispensable party (E. 145).

One of the motions to dismiss sought dismissal on the

ground that appellees failed to allege affirmatively that

they have exhausted their administrative remedies pro

vided by law (E. 150).

The other motion to dismiss sought dismissal on the

ground that this suit is, in effect, a suit against the State of

Louisiana (E. 151).

On March 14, 1960, appellants filed a supplemental oppo

sition to motion for summary judgment (E. 161). By this

document appellants claimed that they were operating

under the Louisiana Pupil Placement Law and since the

highest court of the State of Louisiana had not passed upon

the constitutionality of the Louisiana Pupil Placement Law

the court below should invoke the doctrine of abstention

(E. 161-162).

A third motion to dismiss filed on the same date made

identical claims (E. 167).

On March 14, 1960 the court below held a hearing on all

pending motions which included the motions referred to

above and other motions (E. 166). One of these other

motions was a motion by a third party, Eobert 0. Me-

Craine, Sr., a white parent of East Baton Eouge Parish,

to intervene (E. 159-160, 152). This motion was subse

quently denied (E. 171). Said intervenor also appeals to

this Court (E. 177). Another motion heard on March 14,

1960 was the motion of appellants for a more definite state

ment (E. 148, 164) which was also later denied (E. 170).

5

The motion to add N.A.A.C.P, as a party (R. 145) was also

heard and similarly subsequently denied (R. 170).

Appellants’ several motions to dismiss, although heard on

March 14, 1960, were also subsequently denied on April 28,

1960 (R. 171).

Appellees’ motion for summary judgment was also heard

on March 14, 1960 but was not granted until April 28, 1960

(R. 170).

The injunctive order recited above was not entered in this

cause until May 25, 1960 (R. 171).

The notice of appeal which the Board and Superinten

dent filed was filed one day prior to the entry of this injunc

tion on May 24, 1960 and appeals from the “ decree entered

in the action” on April 28, 1960 (R. 173) which was the

date on which the court below entered an order denying

the various motions of appellants discussed above and

granting appellees’ motion for summary judgment without

more (R. 170-171).

Intervenor’s notice of appeal was filed on May 26, 1960

(R. 177).

In this brief appellees address themselves to appeal of

the Board and the superintendent only. Appellees believe

the intervenor’s appeal to be wholly without merit. More

over, it appears that intervenor has not filed a separate

brief or record on appeal.

6

ARGUMENT

I.

The validity and propriety of the injunctive order

entered by the court below is sustained by prior decisions

of this Court.

The injunctive order of the court below is similar to the

order entered by that same court in Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board (E. D. La. 1956), 138 F. Supp. 336, 337, and

affirmed by this Court on appeal by the defendant school

board in that case. Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush,

242 F. 2d 156 (5th Cir. 1957).

Appellants’ contention that the court below erred in fail

ing to consider the provisions of the Louisiana Pupil

Placement Law (Act No. 259, 1958, L. E. S. 17:101-110) is

patently frivolous and unsubstantial, same being precluded

by prior recent decisions of this Court in similar public

school desegregation cases in Florida. Mannings v. Board

of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Florida, 277

F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960); Gibson v. Board of Public In

struction of Dade County, Fla., 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir.,

1959); Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm,

Beach County, Fla., 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958); Gibson

v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County, Fla., 246 F.

2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957).

The court below did not err, as appellants contend, in

denying their motion to make the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People (N. A. A. C. P.) an

indispensable party-plaintiff. The NAACP, an organiza

tion, manifestly does not have standing to sue to enjoin

appellants from operating their schools on a racially segre

gated basis. Such a suit could only be brought by the

7

parents of the children affected by such unconstitutional

action.

Appellants took the depositions of ten of the fourteen

appellees. These depositions, which are a part of the record

on appeal (R. 62-140), show that appellants were fully

apprised of all of the facts concerning this case. Moreover,

appellants, themselves, as the proper school authorities of

East Baton Rouge Parish, had within their own records

whatever information they could possibly desire concerning

the ages and school assignments of the minor plaintiffs.

Consequently, no error was made below in denying motion

for more definite statement of these facts.

Finally, the validity and applicability of several other

Louisiana statutes affecting school desegregation in that

state, and to which appellants apparently refer when they

contend that certain statutes should have been referred by

the court below to a three-judge court, have been held un

constitutional by a recent three-judge court decision of

August 27, 1960 in Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board

(E. D. La.), Civil No. 3630.1 And this Court’s decision in

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 268 F. 2d 78 (5th

Cir. 1959) had already disposed of appellants’ contention

regarding Act No. 319, 1956, L.S.A.-R.S. 17:341, also held

unconstitutional by the three judge court.

1 The following Louisiana Statutes were held unconstitutional in that

decision: Sections I, II and IV of Act 496 of I960, Section I and II providing

for separate schools for Negro and white children, Section IV reserving to

the Legislature exclusive power to classify schools; Section V of Act 496

of 1960 which gave the Governor power to supersede local school boards under

court order to desegregate; Acts 256 of 1958 gave the Governor the right

to close any school in the state and ordered to integrate; Act 495 o f 1960

gave the Governor the power to close all the schools in the state if one is

integrated; Act 542 of 1960 gave the Governor the right to close any school

threatened with violence or disorder; Act 333 of 1960; Act 319 of 1956; and

Act 555 o f 1954, all of which provided for segregation o f the races in the

public schools and withheld, under, penalty, free books, supplies, lunch and

state funds from integrated schools.

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, the judgment below must

be affirmed,

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ukeattd

A. M. T rudeau, J r.

E rnest N. Morial

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

Constance Baker Motley

T hurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

38