Memorandum from Williams to Greenberg and Others; Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Order

Correspondence

December 14, 1981 - January 18, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Memorandum from Williams to Greenberg and Others; Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Order, 1981. 8026ee81-d992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e3a98614-d5c8-4dea-8217-c3ced4f25dca/memorandum-from-williams-to-greenberg-and-others-brief-in-support-of-defendants-motion-to-quash-subpoenae-or-in-the-alternative-for-a-protective-order-plaintiffs-response-to-defendants-motion-to-quash-subpoenae-or-in-the-alternative-for-a-p. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

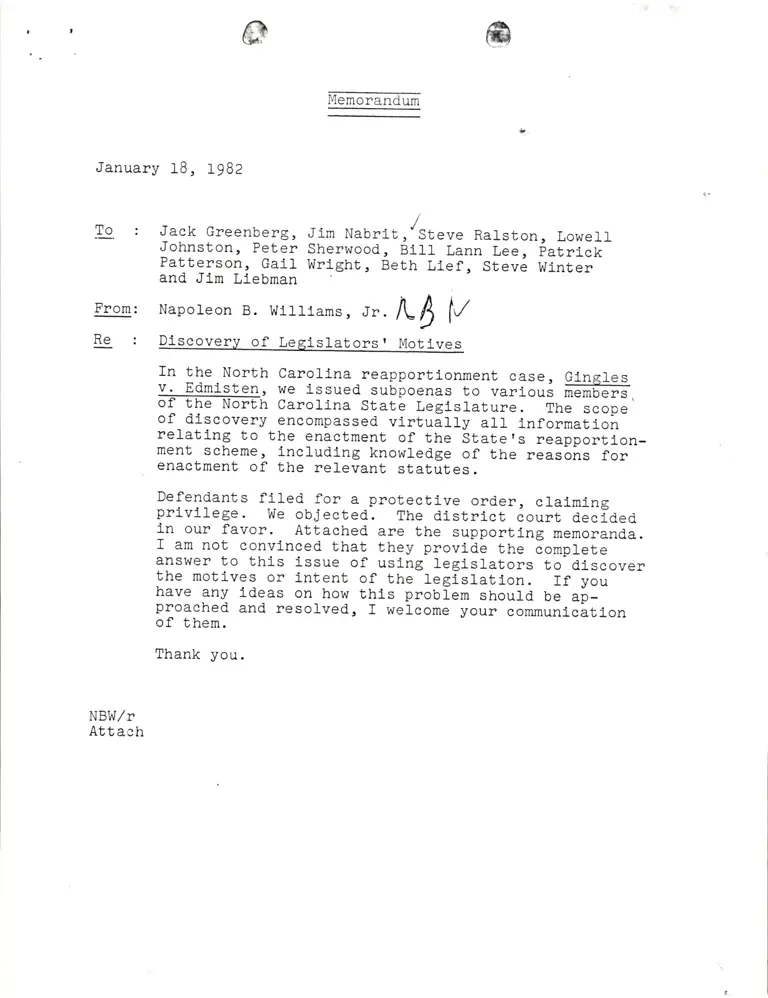

Memorand-um

re

January 18, 1982

From:

: Jack Greenberg, Jim Nabrit,' Steve Ralston, LowellJohnston, Peter Sherwood, Bill Lann Lee, iatrickPatterson, Ga11 Wrlght, Beth Llef, Steve Wlnterand Jlm Llebman

Napoleon B. w1ll1ams, t". k0 lt

Dlscovery of Leglslators r Motlves

rn the North carollna reapportionment case, Glngles

y: PST1.r=t"1,, we issued subpoenas to varioui mffir-s-,of the North carolina state Leglslature. The scopeof_ dlscovery encompassed virtuilly alr lnformationreratlng to the enactment of the state,s reapportlon-ment scheme, lncrudlng knowledge of the reasons forenactment of the relevant statutes.

Defendants f1Ied for a protective order, clalmingprivllege. V{e objected.. The district court aecided1n our favor. Attached. are the supporting memoranda.r am not convinced that they provlde the complete

answer to this issue of using leglslators to discoverthe motlves or lntent of the legislatlon. If you

have any ldeas on how thls problem should be ai-proached and resolved, r welcome your communlcltionof them.

Thank you.

Re

NBW,/T

Attach

FIL F,n< ,1._y'

rN TIIE UNITED S?ATES DISTRICT COUR! flcn

FoR THE EAsTERN DrsrRrcr oF NoRTH cARoLrI'IA -'u ! 4lg1,t

RALETGH o'u"'ol;;r,.

No. r -*#^biffi:rer"

RALPH GINGLES, et. al.,

Plaintiffs,

tr

BRIEF IN SLPPO]?T OF DEPENDANTS I

II1OTION TO OUASH SUBPOENAE OR IN

THE AITEPNASIVE FOR A PROTECTTVE ORDER

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, etc., Et A1.,

Defendants.

INTP.ODUCTION

Plaintiffs have subpoenaed Nortir Carolina Senators Helen Marvln

and Varshall Pauch for the Purpose of taking their depositions on

December 17, 198I. The prospective deponentg, nembers of the }lorth

Carolina General Assembly, are not parties to thls actj.on. Defendants

contend that the matters about which tttarvin and Rauch woul.d be asked

to give testimony are privileged, hence non-discoverable under Ped. R.

Civ. Pro. 25(b)(1), and that such matters are irrelevant to the actlon,

hence also non-di-scoverable under Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 26 (b) (1.) .

I. TNE DOCTRINE OF LEGISLATIVE PRIVTLEGE PREVENTS INOI]IRY INTO

t-dcrs

RuLe 25 (b) (1) specifically excludes from the scope of otherwise

discoverable material matters which are privlleged. The corunon-law

doctrine, variously referred to as legislative privilege or legisla-

tive immunity, affords legislators a privilege to refuse to answer

any questions concerning legislative acts in any proceeding outside

of the legislature. See United States v. I{andel, 415 P.Supp. 1025

(D. Md. 1976). This concept is codified in N.c. Gen. stat. s120-9,

which guarantees freedom of speech and debate in the legislature and

in the legislativ. pto"u"".1

lTh€ sectlon reads as follovrst

"The members shall have freedom of speech and debate in

the General Assemb1y, and shall not be 1lab1e to inpeachment

or question, in any court or place out of the General

Assembiy, for vrords therein spoken; and shall be protected

except ln cases of crirne, frorn all arrest and imprisonment,

or altachment of proPerty, during the tirne of their going to,

coming from, or attending the General Assembly. "

-2-

North carolina,s statutory provision Slarallels the speech or

Debate Clause of the Federal Constitution (Art. I, 56), as well

as the statutory and constitutional enaetments of most other

states. In interpreting the federaL constitutional version of

this doctline the United State6 SuPreme Court has written:

The reason for the privilege is clear' It r'ras

well summarized by Janes wilson an influential

member of the Corunittee of Detail which rras

responsible for the provision in the Federal

Conltitution. nln order to enable and encouraqe

a rePresentative of the publlc to discharge . his

public trust rrith firmness and success, it is

inilispensably necessary, that he should enjoy

the fullest liberty of speech, and th'at he

should be Protected from the resentment of every

one, however porverful, to rrhom the exercise of that

liberty may olcasion offence." TenneY v' Bfc.radl?ve'

341 u.s. 367 (I951) at 372-73 (citatrons omitted).

Legislative privilege has a substantive as well as evidentiary

aspect, and both are founded in the rationale of legislative

integrity and independence, enunciated by the Framers and propounded

two centuries Later by the suprerire court. The substantive asPect

of the doctrine affords LegisJ.ators immunity from civil an<i criminal

liability arising from legislative proceedings. The evi.dentiary

aspect affords legislators a privilege to refuse to testify about

Iegislative acts in proceedings outside the legislative ha1Is. Unlted

State v. ltandel , suP::a at 1027.

At issue here is the evidentiary facet of the privilege and,

specifically, whether such a state-afforde<i evidentiary privilege

should have efficacy in the federal courts. It is clear that the

S;:eech or Debate clause of the fe<leral constitution would preclude

the depositi.on of a member of congress in an analogous situation.

In @, 408 U.S. 508 (1975), the Court stated,

.It ls beyond doubt that the Speech or Debate clause Protects again8t

inqulry lnto acts that occur in the regular courae of the leglalatlve

proceas and lnto the motlvatlon lor those acts.r 408 U.S. at 525.

L

-3-

Defendants acknowledge that even the privllege granted federal

legislators is bounded by countervailing considerations, particularly

the need for every manis evidence in federal criniinal prosecution.

As Brewster further states, 'the privileee is hroad enough to insuret'

the historic independence of the Legislative Branch . . . but narrov,

enough to guard against the excesses of those wlro woul<l corrupt the

process by.corrupting its memhers.n 408 u.s. at 525. Defendants

motion attelpts, however, to conceal no ncorruption"'

with the boundaries of the federal legislatlve privileqe in

mind, we turn to the question of the scope of paral1eI state prlvileges'

whatever their extent and range of applicability in state court, the

united states suprene court has ruled that state privileges v'ill, at

times,yeildtooverridingfederalinterestsinfederalcourts'

unj.ted states v. Glllock, I0o s.ct. 1185 (1980). The Court has

recognized only one federal interest of irnportance sufficient to

merit dispensing with this state-granted privilege: the prosecutlon

of federal crimes.

The supreme court has never sgrarely addressed the issue Presented

here: whether a state legislatorrs evidentiary privilege remains

intact in federal civil proceedings. In Tenney v. Broadhove, 9.g!E,,

the court ruled that a legislator's substantive irununity from suit

withstood the enactment of 42 U.S.C. 51983, and thus state legislators

were not susceptible to suit for r.rords and acts wlthin the purvievr

of the legislative process. Although it deals with the substanti.ve

aspect of the privilege, Tenney is instructive, i'nsofar as the court

there gave great deference to the state'g own doctrine. Recently,

in united states v. Gillockr suPrar a crlurinal case involving the

evidentiary f,acet of legislatlve lnununlty, the Colrrt clted Tennev

for the propositlon that all federal courts nuEt €ndeavor to apply

atate legislatlve prlvllege. In @, howevor, thc court rulcd

-4-

that the Tennessee Speech or Debate Claug-g would not exclude

inquiry into the legislative acts of the defendant-legislator

prosecuted for a federal criminal offense

Throughout the Suprene Court,s activity in thi.s field no r.

distinction has been drawa betvreen substantive and evidentiary

applications of the privirege for the purpose of determining the

efficacy of legislative privilege in federal court. Thus, the

Court's conclusions in Gillgck and T93EI must be read together,

and their comhined effect dictates that the evidentiary privilege

granted a legislator by his state rernains inviolabre except where

it must yield to the enforcernent of federal criminal statutes.

See Gillocl: at 1193.

Unless federal criminal prosecution demands othe:r..rise, "the

role of the state legislature is entitled to as much judicial

respect as that of Congress . . . lhe need for a Consress vrhich may

act free of interference by the courts is nei.ther more nor ress than

the need for an unimpaired state J.egi.slature." star Distributors, Ltd.

v. Marino, 613 P.2d 4 (1980) at 9. On this fundamental point the

Supreme Court has recently said, "To create a system in which the

Bill of Rights rnonitors more closely the conduct of state officials

than it does that of federal officials is to stand the constitutionar

design on its head.n Butz v. Economou,428 tr.S.47B (1929) at 504.

In the present civil action, brought by prlvate citizens of

liorth Carolina, Leqislators t{arvin and Rauch are privileged to refuse

to testify concernins their regislative acts. principles of comity

and the decided law strongry suggest that federal courts honor.this

evidentiary privilege in all civil actions.

rI. THE I,TATERTAL SOUgHI TO BE DISCOVERXp rS TRRELEVAIIT.

The North Carollna Houao, Scnato, and Congreaalonal reapportlonnan!

plana challenged ln thla lltlgatlon apeak f,or thcngelves. rncolar as

-5-

the intent of the legislature is in quegtion, the legislative history,

i.e., the contemporaneous record of dehate anC. enactment, reveals the

Iegislative intent. The remarks of any single legislator, even the

sponsor of the bi1l, are not controlling in analyzing legi.slatlve

t!

history. Chrysler Corporation v. Brown, 441 U.S. 281 (1979). That

such remarks have any relevance at all precludes that they were made

contemporaneously and constitute part of the record. See qniteg

State v. Gila River Pima-llaricopa Indian Conununity, 586 F.2d 209

(Ct. Cl. 1978). This proposition ls adhered to even more strongly

by the appellate courts of North Carolina. The North Carolina Supleme

Court, for example, stated the following in D & I.!, Inc. v. Charlotte,

268 N.C. 577, 581, 151 S.E.2d 24L, 244 (1965):

". . . llore than a hundred years ago this Court

held that 'no evidence as to the moti.ves of the

Legislature can be heard to give operation to, or

to take it from. their acts. . t Drake v. Drake,

15 N.C. 110, 117. The meaning of a sFffiFaid-EhE'

intention of the legislature which passed it cannot

be shown by the testimony of a memher of the legisla-

ture; it rmust be drawn from the construction of the

Act itself.' Goins v. fndian Training School, 169

N.C. 736, 739,

The testj-mony of Marvin and Rauch is not relevant tn the intent

of the General Assembly and can have no other discernahle relevance.

Thus, their depositions are outside the scope of pcrmissible

discovery.

III. PRESERVATION OF LEGISLATIVE INDEPENDENCE REQUIRTS THAT, SHOULD

If the court orders the depositions to proceed, lt Is imperatlve

that tho transcripts he sealed and opened only upon Court Order. The

purpose of legislative privilege is to "avoid intrusion by the

Executive or the Judiciary into the affairs of " "o-"qual

hranch,

and . . . to protect leglslative independence.' Gillock at I19I.

L

-6-

Legislators must feel free to discussland ponder the plethora

of economic, social, and polltical considerati.ons which enter into

legisrative decision-rnaking. Eear of subsequent discrosure of an

individuar legislator's intent or rati.onale rvould ch1I1 debate and

t'

destroy independence of thought and vote. In this case, sensitive

political consideratj.ons rnight be recklessry exposed by the plaintlffre

proposed dj.scovery. To maintain free expressi.on of ideas vrithin the

General Assemblyr as well as to protect those ideas already freely

expressed therein, a protective order nust issue, lf the subpoenae

are not quashed, as they should be.

Respectfully submitted, this ,n" ( day of December, 1981.

P.UFUS L. EDI'ISTEN

ATTORNEY GT,I.IERAL

Agt6rnev ceneralrs Office

[. C. oepartment of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, llorth Carolina 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377

Norma Harrell

Tiare Smiley

Assistant Lttorneys General

John Lassiter

Aesociate Attorney ceneral

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

Jerris Leonard & Associates, P.C.

9oo 17th street, N.r{.

Suite I020

}lashington, D. C. 20006

(2021 872-L095

, rIf.

Attorney

Legal Affairs

CERTIFTCATE OF Sr:RECE

I hereby certify that I have this dav served the foregoino

Motion to Quash subpoenae or i.n the Alternative for a Protective

Order and foregoing Brief in suPport thereof upqn Plaintiffsr

attorneys by placing a copy of same in the United States Post

office, postage prepaid, addressed to:

- J. Levonne Chanbers

Leslie l{inner

Chamhers, Ferguson, ?latt, I{a11as,

Adkins & Fu11er, P.A.

951 South IndePendence Boulevard

Charlotte, llorth Carolla 28202

Jack Greenberg

James l:. llabrit, III

Napeoloen B. wil1iams, Jr.

I0 Columbus Circle

Nev, York, New York 10019

This the / y' uu, of December, 1981.

RALPH GINGLES,

v.

RUFUS EDMISIEN,

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE i,

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

NO.81-803-CrV-5

eE al.,

Plainciffs,

et a1. ,

De fendant s .

PIAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO

DEFENDANTS' MoTIoN r0 QUASH

SUBPOENAE OR IN THE ALTERIIA.

TIVE FOR A PROTECTI\E ORDER

I. Introduccion

Plainclffs, black citizens of Norch Carolina, bring this

acElon Eo enforce Chelr righc Eo vole and Eo have equal repre-

senEaElon. They asserE claius under the fourteent,h and Flfceenth

Amendments to che United States ConsEicucion and under gg2 and 5

of che Voting Righcs Act of 1965, as aoended, 42 U.S.C. S$1973

and 1973c ("The Voting Rights AcE"), challenging che apporEionroenc

of che NorEh Carolina General Assembly and the United SEaEes

Congressional distrlcEs in North Carolina. Ptainciffs allege thac

the apporrionmencs were adopEed with che purpose and effecr of

denying black clEizens the rlght to use chelr voces effectively

and Ehac Ehe General Asserobly apportionmenEs vtolaEe the i'one

person-one voEe" provlslons of rhe equal procecclon clausc.

Discovery h35 qemgnqsd. 0n Deceober 3, I981, plaintiffs

noEiced the deposicions of and subpoenaed Senalor Marshall Rauch,

the Chairoan of che Norch Carollna SenaEe's CouricEee on Legls-

lacive Redlscrlcting and SenaEor Helen Marvln, che Chairoan of

che Norch CaroIlna Senace's CourlcEee on Congresslonal RedlstrlcClng.

The subpoenae request chac Ehe senaEors bring Eo che deposiElons:

DocuoenEs of any kind which you have in your possession

which relaEe Eo che adopclon of SB 313 t87l durlng che 1981

Session of che Norch Carolina General Assenbly. This

:

requesE includes buE is noE litriEed Eo correspondence,

menoranda or oEher writings proposingfor objecting Eo

any plan for apportionmen! of North Carolina's Senace

ICongressional] discrlcts or any criEeria cherefore.

Defendants ruove Eo quash the subpoenae on the grounds EhaE

neiEher senacor can give any relevanc EesEiEony and that arl tesEi-

nony of both senarors is prlvileged. plainriffs oppose this notion.

Defendants' moEion Eo quash is an objeccion Eo Ehe entire depost-

llons- Prainciffs have noE asked partlcurar questions. rf plain-

Eiffs had Eaken the deposiEions, the inquiry would have incruded the

fo llowing

1. The naEure of the Senator's role as Chairman of a

Redlstrict ing Conrnit,tee ;

2. The sequence of evenEs whtch lead to the enacEmenc of

che redistricting legislatlon;

3. Normal procedures for enacting Ehis type of legi.slatlon;

4. fhe criEeria adopced by the redistrictlng coumiEtees i

5. Fact,ors normally considered inporEant in redisEriccing;

6, The existence of any subscantive or procedural departures

from nornalt

7, The extscence of documenEs, official records, or unoffi-

cial records which conE.ain che substance of commiEcee, subcomictee

or whole SenaEe debate i

8. Their knowledge of che conEemporary sEacemenEs by mem-

bers of the legislature of che reasons for adopcing or rejeccing

proposed apportiontrenE plans ;

9. The exiscence of wlEnesses co sEaterDenEs as described ln

paragraph 8 above; and

I0. The exiscence of oEher wlcnesses who observed or were

invorved in che process uhac red Eo che enacEuen! of che chalrenged

aPPorc lonulenE s .

Because che SenaEors were che Chalroen of che redlscricCing

comniEcees which $rere responsible for reporclng co che full Senace

a recorElended apporrionoenE for enaccmenE, plainciffs believe each

has knowledge relevanE Eo chese inquiries.

One of plainciffs' allegacions is Ehac chese apporcionmenEs

discriminace againsc them on the basis oftr."" in violation of

the equal proEeccion clause of the Fourteench Amendment. In

order t.o prevail on this claim, plaintiffs ousE shor., EhaE Ehe

plans were conceived or nainEained with a purpose to discrininaEe.

cicv of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 tJ.s. 55 (19g0); village of Arlingron

HeiehEs v. Merropol@, qzg u.s. z5z (L977);

l.IashinRcon v."Davis , 426 U.S. 229 (1976).

In addtEion, it ls arguable that plainciffs utrst show purpose

to diluce brack voce in order to prevail in Eheir claims under s2

of che Voting RighEs AcE. See Mobile v. Bolden, g.gpIi, l^Iashinscon

v. Finley, _ f .2d _, (4Eh Cir ., ,80-L27 7, Novernber 17, 19g1).

The Supreme Courc in Arlington Heighrs, g.lry, noEed EhaE,,

"DeEermining whecher tnvidious discriminatory purpose uas a ruocl-

vaEing factor demands a senslt,lve iirquiry inEo such circuoscancial

anddirecc evldence of incenc as Day be available." 429 V.S. at 256.

Anong che subjeccs of proper inquiry for provlng incenc lisced by

che Suprene CourE are:

l. The specific sequence of evenEs leading up Eo the chal-

lenged decision;

2. Deparcures from normal procedural sequencet

3. Subscancive departures from factors usually considered

inporcanE; and

4. ConEemporary sEaEemenCs by members of the declsionmaktng

body, minutes of iEs ureeEings, or reporcs.

Arlington Heighrs v. ttetro Housing Corp., 429 V,S. ac 257-268. See

also McMillan v. Escamlia_gg_=_, 638 F. Zd LZ3g (5ch Cir. I98I) ;

U.S. v. City of Parma, 494 E.Supp. 1049, 1054 (N.D. Oh. l98O).

Senacors Rauch and Marvin would be expecced co glve Eestinony

rclevanc co each of chese inqulries. rn addlclon, Ehe supreoe courc

recognized, "In some excraordinary lnscances Ehe oembers oighc be

called Eo Ehe scand ac crial Eo EesEify concerning Ehe purpose of

of f icial acEion, . .. . " Arlington HeighEs, .guora..

-3-

rn additi.on, defendanEs have raised as Ehe Fourth Defense

in their Answer EhaE, "The deviaEions in in" ,rr, Apporcionnent

of the Generar Assenbry were unavoidabre and are jusrified by

raEional srate policies." This defense relaEes ro plaintiffs,

"one person-one voEe" crairn. rf alrowed Eo Eake the deposirion

of senaEor Rauch, chairnan of the SenaEe comnittee on Legisra-

tive Redistricting, plainciffs would inquire about the raEional

scace policies chac caused the populacion derriations in the

senaEe plan and wourd inquire about che exiscence of ocher prans

thac met chese poricies bur had rower populacion deviacions.

These depositions and these lines of inquiry are peroiEced

under Rules 26 and 33 of che Federar Rules of civil procedure and

under the Federal Rules of Evidence.

II. THE TESTIMONY OF SENATORS RAUCH

AND MARVIN IS NOT PRIVILEGED.

Rule 501 of the Federal Rules of Evidence provldes, in per-

EinenE parE:

Excepc as oEherwise required by che Conscitucion of che

Uniced SE.aEes or provided by Acr of Congress or in rules

prescribed by the Supreme Courc pursuanE Eo scaEuEory

aurhoricy, che privilege of a rritnessr p€ESoo, governnen!,

Scace, or policlcal subdivision Ehereof shall be governed

by che principles of che coymon law as chey rnay be inEer-

preted by che courEs of che United SEaEes in che light of

reason and experience.

This rule applies Eo discovery as weII as to t,rial. F.R.Ev.,

Rule 1101(c). Thus, in ordcr Eo deEeroine if Ehe resciuony of senaEors

Rauch and Marvin is privileged wirhin Ehe meaning of Rule 26(b) of

che Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Ehe CourE EusE deceroine if lt,

ls covered by Rule 501 of che Rules of Evtdence. See !l=f-J.;Q!!!g!,

445 U.S. 350, 366 (1980).

Defendancs asserc a legislacive privilege parallel co uhe Speech

and Debace Clause of Arcicle I, $6 of che Uniced Scares Consclruclon.

However, che Speech and Debace C1ause applies only co meubers of che

uniced sE.aEes congress, noE Eo stace legislators. Nor does the

sEate sraruEe esrablishing the privilege i.il stat.e courEs esEabrish

che privilege under Ehe Federal Rures. u.s. v. Gillock, 44g u.s.

at 358' 374. Defendant.s do noc eite any provision of the uniEed

Scaces Consticution, Act of Congress, or Supreme Courc rule which

establishes a privilege which exe'pts stace legislalors froo ces-

tifying' rhus Ehe courE musE deEermine if Ehe EesEimony is pri-

vireged "by Ehe principres of cormon raw as chey may be inEerpreted

by che courts of che unired scates tn light of reason and experlence.,,

F.R.Ev., Rule 501.

Defendancs ciEe no case in.which legislacive privirege is

excended Eo che cest,imony of sEate legisracors, and plainciffs know

of none. U.S. v. ltandel, 4I5 F.Supp. lO25 (D.Md. Lg76), which

defendanrs cice in support of che evidentary privilege, is a case

tn which a st,ate governor asserted irmunit,y froo criminal prosecu-

cior; and Ehe courc held chac Ehere was no imunity for governors

doing legislative acEs. The language quoEed by defendancs ls onry

dicta, Iargely irrelevanE Eo che issue before EhaE Courr.

rn order Eo deEermine wheEher a privilege paralrer to the speech

and Debate crause should be creaEed for state legislators, iE is

helpful Eo analyze Ehe purposes of the speech and DebaEe clause.

Ics history is seE ouE in Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 U.S. 16g, 2O

L.Ed. 377 (I881). The clause rras paEEerned afrer an English parlia_

menEary provision which was designed co stop Ehe crown from inprlsoning

llembers of ParlianenE for sedicious ribel. 26 L.Ed ac 390-391. As

cranslaced inco che American republican form of governmenE,, Ehe

clause has Ewo purposes:

l. To procecc Ehe meobers of the co-equal legislacive

branch of the federal governmenE from prosecucion

by a possibly hosrtle execuElve before a posslbly

hosctle Judiciary, Kilbourn v. Thonpson, supra; and

2. To preserve che independence of che leglslacure by

frcelng rhe members froo rhe burden of defendlng

Ehemselves in courE and of ulcimace liabilicy.

Dombrowski v. Easrland, 387 U.S. 82 (1967).

-5-

Neicher of chese reason is appli.cable to the moEion before

the CourE. '

Since a scate legislaEure is noE one of Ehe Ehree co-equal

branches of che federal governrnenE, che firsc reason does noc

apply. The Supreme CourE reached this conclusion in llr[!!!!gk,'

supra, in holding EhaE a scace legislacor is noc isgrune from

federal prosecution for crimes cormicEed in his legislacive capaciEy

and t.hat he had no privilege againsc che admission into evidence of

his legislacive accs. Both would have been precluded if a privilege

similar in scope Eo the Speech and Debace Clause applied. In

reaching the conclusion che CourE said:

The firsr racionale, resllng solely on Ehe sePararion-of-

powers docErine, gives no supporE Eo Ehe granE of a privi-

lege Eo state legislaEors in federal crioinal prosecuEions.

IE requires no ciEation of auchoriEies for che proposiEion

that. che Federal Government. has limiced powers wit,h respect

Eo Ehe sEaEes, unlike the unfercered aughority which English

monarchs exercised over Ehe Parliamenc. By che same Eoken,

however, in chose areas where Ehe Consritution granEs Ehe

Federal GovernmenE che power Eo acE,, Ehe Supremacy Clause

diccaces chat federal enacEmencs will prevai.l over cooPeEing

sEaEe exercises of power. Thus, under our federal sEruccure,

we do noE have the scruggles for power beElreen rhe federal

and sEace sysEems such as inspired Ehe need for che Speech

or Debace Clause as a resErainc on the Federal ExecuEive co

proEec! federal legislacors. 445 U.S. at 370.

Since a scare legislaEure is nog a co-equal branch wich che

federal legislacure which passed che Vocing Rights AcE or wich the

Federal Courcs, rhe flrsE reason for che Speech and Debace Clause

has no relaclon co Ehis acElon.

The second purpose for che Speech and Debace Clause ls Eo assure

chaE che legislacors can be free co sPeek ouE wi.EhouE. fear of liabi-

1icy.Forrh!sproposiciondefendanEsciEc@'34l

-6-

U.S. 367 (f951) and SEar Discributors Ltd. v. Marino, 613

F.2d 4 (2d Cir. 1980).

However, in boch of chose acEions Ehe staEe legislacor was

che defendanc. The cases discussed not an evidentiary privilege but.

raEher a coumon law iurmunicy from liabilicy. The purpose of pro-

Eeccing legislacive independence is fully protecced if legislators

are relieved of Ehe burden of defending Ehemselves. Powell v.

Mclqorlnack, 395 U.S. 486, 501-505 (1969).

Plainciffs do noc seek Eo hold eicher SenaEor Rauch or SenaEor

Marvin liable. Neither is a defendanc. Neicher !s puc in a posi-

tion of having she burden of defending Ehe acEion.. A11 plainciffs

seek is Eo discover whac evidence each has thar eic,her supporcs

che claims or defenses.

In addition, in @, -ggp53, che legislator was sued for

money d:mages. Ic is reasonable chat possible financial liabilicy

might inhibic a legislacor from act,ing his conscience. Ir is

noc reasonable thar merely having Eo disclose Ehe process or sub-

sEance of legislati.ve actions will prevent a legislacor from

acclng in the interesEs of che people. Plaintlffs herein do noE

seek money damages from anyone, much less Senacor Rauch or SenaEor

i,tarvin. FurEfrermore, in SEar DisEributors, .ggg., an ac!ion Eo

cnjoin a legislacive investigaEion, Ehe Courc sras careful t,o Point

ouc EhaE che plaintiff had anoEher remedy available; co refuse Eo

courply wiEh che legislacive subpoena and asserE Ehe claim as a

defense in conEempt proceedlngs. In rhis case, plainciffs EusE

asserc their claim in a judicial proceeding or noc ac a1l. They

have no oE,her renedy.

FinalIy, Ehe nccion of independence of scace legislacures is

anElEheclcal co che purpose of rhe FourceenE,h AoencroenE and of

che VoEtng Rlg,hcs Acc, boEh of which have che purPose of ltolclng Eh.

acEtons which scaEes may rake. See, e.8., @

v. Kaczenbach, 383 U.S.30l (1956).

Afcer rejeccing boch che seParaEion of

of legislacive privilege. rhe Supreme CourE

che doctrine of comiEy. The CourE scaEed:

powers and independence

in Gillock also considered

-7-

We conclude, Eherefore, chat alchough principles of

cooiEy command careful consideration,|our cases dis-

close chac where lmportant federal interests are ac

scake, as in Ehe enforcemenE of federal crininal

staEuEes, comity yields.

Here we believe t,haE recogniEion of an evidenciary

privilege for sEaEe legislacors for their legislacive

accs would impair che legitimaEe i.nEerest of the

Federal Governmenc ln enforcing its crininal staEuEes

with only speculaEive benefit to the state legislacive

process. 445 U.S. aE 373.

In Gillock the imporcanE federal interest was enforcemenc of

a crininal sEaEuEe. However, enforcement of the Uni.ced SEates

Conscitucion and of the VoElng Rights Act is of equal imporEance.

This r.ras recognized by the Court of Appeals for rhe FourEh CircuiE

in Jordan v. Hurchinson, 323 E.2d 597, 600-601 (4Eh Cir. I973),

in holding EhaE plaintiffs, black lawyers, could maincain an acEion

againsc che members of an invesEigatory couuriEtee of the Virginia

legislacure seeking co enjoin the legislaEors from engaging in

racially morivaced harassmenE of plaintiffs and Eheir cliencs.

Thc Court scac.ed, "The concepE of federalism, i.e. federal respecE

for scace inscicucions, will noE be pernicted to.shield an inva-

sion of citizen's consc.itutional righcs." Id at 501. Thus plain-

tiffs were allo*ed to maincain an acEion with legislacors as defen-

danrs. The incrusion here is, of course, utrch more minor.

In addicion, Congress has provided chac a prevailing plainciff

in an accion under che Vocing Righcs Acc or under 42 U.S.C. 51983

is co be awarded his accorney's fees. 42 U.S.C. S$I973Uc) and

1988. The reason for che fee award provtslon lg chac Congress

rccognlzcd chc lmporcanco of ancouraglng prlvacc clctzeno, scctng

as privaEe arEorncys generaL, co cnforce Ehe Vocing Righcs Acc and

che Conscicucion. R!ddelI v. Nacional DemocraElc ParEf:, 624 F.Zd

-8-

539, 543 (5Eh Cir. 1980); 5 U.S. Code Congressional and Adminis-

crative News 5908, 5910 (1976). The righs Eo vote and Eo be fairly

represenEed are central Eo our democratic governmenE.

DefendanEs' quoE.e from Bucz v. Economou, 428 lJ.S. 478, 504

(f978), Eo che effecr EhaE Ehe iuununity of a federal defendanr

should noc be greaEer Ehan the irurunity of a scate defendanE, is

inapposice. In Bucz the quescion was whecher federal adminisEra-

Eors should have greaEer innunity fron liabilicy for invading

an individual's consEituEional rights Ehan do sfuoilar state adnini-

sEraEors. The question involved cooparing Ehe proEeccion of

42 U.S.C. S1983 and the Fourteenth AmendmenE Eo Ehe proEection of

the Fourch and Fifch AmendmenEs co the Uniced Staces Conscicucion.

the Court held chac Ehe tlro could noE be rationally distinguished.

Ihac is a tar cry from Ehe situacion here in which Ehe U.S.

Congressional irnunrnity, creaEed by an unanbiguous consciEuEional

provision, is compared co Ehe stace legislaEor's privilege, a

creaEure of either sEace sEatuEe or unprecedented federal conmon

law.

Even if Ehere is an evidenEiary privilege for sEat.e legisla-

tors, in Ehis case iE musE give way in the inEerest of cruth and

juscice. The courEs have recognized chac privileges of governuenE

officials are in derogation of che Eruch and musE exEend only to

Ehe exEenE necessary co proEecE the independence of che branch in

question. See, e.g., U.S. v. Nixon, 4I8 U.S. 683, 710 (1974) ;

U.S. v. Itandel,415 F.Supp. ac 1030.

However, in rhis case privilege would be more Ehan in dero-

gacion of che cruEhi ic would prevenE plainciffs froo being able

Eo prove an essenEial elemenc of Cheir clains. As discussed in

Parc I, above, discrininacory Iegislaclve PurPose is a necessary

elemcnc of ac lcasc one and posslbly cwo of plalnctffs'clalns.

To hold onc che one hand chac evldencc of leglslaclve purpose ls

necessary and on che oEher chac ic is privileged and inadroissible

is co make a mockery of boch che ConsciEuEion and che Vocing Rlghcs

Acc.

-9-

This reasoning was recognized by the Supreme Courc in

Herbert v. Lando, 44f U.S. 153 (L979). In'HerberE Ehe Courr held

that a television news edlEor could noc claim his First Agrenduenc

privilege noc co disclose his sources, Eocivations, and chought

processes in a libel suic broughc by a public figure. The CourE

recognized it would be grossly unfair co require che plainciff to

prove acrual malice or reckless disregard for che cruuh and pre-

clude him fron inquiring Eo the defendancs' knowledge and moEiva-

Eion. Id. ac 170.

The Courc noEed, in addition, E,hac, iE. was particularly

unfair ro allow defendancs co tesEify to good faich and preclude

plainciff froro inquiring lnco direcc evidence of known or reckless

fal sehood.

Thus the Court concluded EhaE an evidenEiary privilege,

even one rooEed in the Conscitutioh, musE yield, in proper circuu-

sEances,-to a demonstraEed specific need for evidence.

In Ehis case, as in Herbert v. Lando, plaintiffs have demon-

srraEed a specific need for Ehe evidence which Senators Rauch and

Marvin have which may escablish'discriminarory purpose. This case

is, however, even scronger Ehan Herberc v. Lando because, in

Herbcrt, defendanrs asserEed a ConsclEuclonal privilege. In chls

case Ehe privilege, if one exisEs, cotres only from common law or

scace sEar,uE.e.

The Supreme CourE. in ArlingEon Heighcs v. Metropoliran Housing

Aurhority, supra, recognized chat in some circumsEances a oember's

cescimony abouE moEivaEion could be privileged and ciced Cicizens to

Procect OverEon Park v. Volpe, 40I U.S. 402 (1971). 429 U.S. ac 268,

n. 18. In Overcon Park che Supreure Courc considered whether the

SecreEary of TransporEaEion could be examined as co his reasons

for choosing Eo puE a highway chrough a park. The Courc held chac

under che circunscances in chac case he could be examined. The Courc

reasoned chac alchough ic uras SeneraIly co be avoided, when Ehere

was no formal record decailing che reasons for che decision, ic is

permissible co examine che menEaI process of decisionmakers. Id. ac 420.

-10-

In chis case, as in Overton park, supra, lhere is no formal

record adequaEe to deEermine Ehe purpose, or even che process, of

Ehe legislaEors. A direct exami.narion is, cherefore, peruissi.ble.

III. THE TESTII'IONY OF SENATORS RAUCH AND MARVIN IS

RELEVANT TO THE SUBJECT MATTER OF THE ACTION.

RuIe 25(b) provides in perEinent part, "parEies nay obcain

discovery regarding any maErer, noE privleged, which is relevanc

Eo the subject EaEt,er in the pending action, ... IE is noE ground

for objection Ehat Ehe informarion sought wilr be i.nadroissible at

the Erial if the infornarion soughE appears reasonably calcuraced

co lead Eo the discovery of admissible evidence.,'

Thus, in order co be enEitled Eo prevenE the entire deposit,ion,

defendancs must show thac the "informaEion soughE was whol1y

irrelevant and could have no possible bearing on t,he issue, but in

view of Ehe broad Eest of relevancy. aE Ehe discovery sEage such a

moEion will ordinarlly be denied. " WrlghE and Miller, 8 Federal

Praccice and Procedure 52037

The EesEiDony of Ehe Ewo senators is relevanE Eo Ehe subjecC

maEEer. Each senator was Chairnan of a Redistricting ComiEtee.

As discussed in Part I above, Ehese senaEors are believed co have

knowledge of the procedures used for developing Ehe apporcionoenEs,

Ehe criceria used by the cormiE.Eees, other plans which were consi-

dered but rejecEed, and che docr:slenEs and sEaEements which indicace

Ehe reasons EhaE che General Assembly adopced che proposals which

plaintiffs challenge.

Under che Supreue CourE decisions in Cicy of Mob.ile v. Bolden,

supra, and Village of ArLingcon Heighcs v. Metropolican Housing

9orporaciog, .W,, chis informaEion is noE sinply relevanc, iE is

cricical co plainciffs' abiliEy co prove Eheir claims.

Defendancs asserE Ehac Ehe legislacive hiscory and official

records speak for chemselves and rhat che indlvidual senaEors'

Eescimony is, therefore, irrelevanE. Plainciffs know of no official

records which concain any comiEcee proceedings, Ehe concencs of any

floor debaEe, Ehe criEeria used by rhe comictees, a lisc of pro-

posed apporEionmencs available co buc rejected by Ehe conrmicEees,

-lr-

or the contemporaneous sEJEemenE.s of Ehe members, If, however,

these records exisE, perhaps SenaEors Rauch'and Marvin can describe

E,hem so thac plaintiffs may discover rhem.

Finally, defendanc,s asserc EhaE Ehe Eestimony of legislators

is noE relevanE when analyzing legislacion. Plaintiffs do not seek

Eo use Ehe cesEimony Eo inEerprec any aurbiguicy in che legislaEion,

as Ln D & W, Inc. v. Charlqtle, 268 N.C. 577 (1966), ciEed by

defendancs. Racher, plainciffs seek t.he tesctmony Eo establish

purpose. See Arlington Heighis, .ggpE. To this end, Ehe tesEimony

is relevanE.

IV. CONCLUSION

"Exceptions Eo che demand for every rnanrs evidence are noc

lightly created nor expansively conscrued, for they are in dero-

gacionofchesearchforEruEh.''@,441U.S.ac170.

"These rules shall be consErued Eo secure fairness in adninls-

Eration, .,. Eo che end t,hat the truch may be ascert.ained or pro-

ceedings justly deEermined." RuIe 102, F.R.Ev.

The search for EruEh requires chac defendanEs noE be allowed

Eo ascerE a privilege which wilk deprive plainciffs of the proof

of one of the necessary elemenEs of their claios. To require

plainciffs Eo prove purpose and Eo refuse to allow Ehem co lnquire

abour ic is neirher fair nor jusc.

PLaintiffs, Eherefore, request, thac che subpoenae of SenaE.ors

Rauch and Marvin noE be quashed.

This 30 day of December, 198 1.

t1u,a" / U",**,

J . Le VONNE ,'CHAIIBERS

LESLIE J. WINNER

Chambers, Ferguson, WaEE, Wallas,

Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suice 730 Easc Indepence Plaza

951 Souch Independence Boulevard

Charlocre, NorEh Carollna 28202

704/ 37 5-846L

AEcorneys for Plainciffs

-L2-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

r certify EhaE r have served che foregoing plaintiffs' Response.

To Defendant.s' Motion To Quash subpoenae or rn The Alternacive For

A ProcecEive order on all oEher parEies by placing a copy thereof

enclosed in a postage prepaid properly addressed wrapper in a posc

office or official depository under Ehe exclusive care and custody

of che Unlced SEaEes Poscal Servtce, addressed Eo:

Mr. James Wallace, Jr. Mr. Jerris Leonard

NC Actorney General's Office 900 lTEh SE. NW

Posc Office Box 629 Suire 1020

Raleigh, NC 27502 Washingron, DC 20006

This ?O day of December, 1981.

-13-

I

f'-^

a_ {ffirrvEg:I

i i- J :FTIJED

I I 'ftrlraac

^-** rtf, r, r lrq4l.Ss:,.1t*;Jiltrh" uNrrED srArES DrsrRrcr couRr\ u'*r ' rtbn'rtne EASTERN DrsrRrcr oF NoRrH cARoLTNA UAll 5 1982

RALETGH DrvrsroN

:r.RlcH TJoNARD, v-tRh

I'. S. DISTRICT COURT

E DIST. NO. CAR.

RALPH GINGLES, 6t al.,

Plaintiffs NO.8r-803-CrV-5

vs.

RUFUS EDllISfEll , et aI. r

De fendants

ER

Ihis action brought by black citizens of North carolina chal-

Ienging the apportionment of the North Carolina General Assembly and

the Unitedl States Congressional districts in North Carolina is before

the court for a ruling on defendants I motion to quash sgbpoenae or in

the alternative for a Protective order. on Decerober 3, 1981, Plaln-

tiffs noticed the depositions of and subpoenaed Senator Marshall

Rauch, the Chairman of the Nortlr Carolina Senatets Committee on

Legislative Redistricting, and senator Helen Marvin, the chairman of

the North Carolina Senaters Comnittee on Congressional Redistricting'

Defendants have moved to quash the subpoenae on the grounds that the

testimony sought is lrrelevant and privileged. In lieu of an order

guashing ttre subpoenae, defendants seek a pr'otective order.directing'

that the transcripts be sealed andt opened only upon court order.

Plaintiffs oPPose the motion to quash but have not resPonded specifi-

cally to the motiotl for a protective order'

The testimony sought is plainly material to questions presented

inthis1itigation.InordertoPrevai1onat1eastoneof,

claims, plaintiffs must shor,, that the reapportionment plans were

qonceived or uraintained with a PurPose to discrininatc. citv of

Mobile L @, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). The matters concerninE which

testimony ls eought, lncludtng the sequenqe ol eventa leadlng uP te

the adoption of the aPPortionment plans, departures from the nornal

procedural sequence, the crlteria congldered inportant in tlre aPPor-

tionment decision, and contemporaly scatements by members of the

legislature,areallrelevanctothedeterninationofwhetherarr

invidiousdiscriminatoryPurposeUasaEotivatingfactorinttre

ORD

\ >.4

decision. Village of Arlington Hei'ghts v' MetroPolitan Housing

Developmen! corporation ' 42g l)'S' 232' 261-268' (19?7)' In general'

without addressing any particular guestion which toight be asked during

the depositions' the matters sought are material and relevant'

the .legisLative privilege" asserted on the senators' behalf does

!

not prohibit their depositi'ons here' fhey are not Parties to ttris

Iitigation and are in no way being made personally to answer for ttreir

statements during legislative debate' Compare' e'g" Dombrowski v'

Eastland, 387 U's' 82 (1967)' Because federal lav' EupPlies the rule

of decision in this case' the guestion of the Privilege of a witness

is ngoverned by the principles of the conunon larv as they rnay be inter-

preteal by the courts of the United states in the fiTfrt of reason and

experience." F'R'Evid' 50I' No federal statute or constitutional

provision estabtishes such a privilege for state legislaLors ' nor does

the federal common law' See United States v' Gillock' 445 U'S' 360

(f980). It is clear that principles of federalism and comity also do

not Prevent the testimony sought here' See United States v' Gillock'

Ilerbert v. I4l19' 44I U'S' I53 (1979)'

for these reasons ' the motion to quash must be denied' In an

effort ,to insure regisrative independence,' unitecl slates v' Girlock'

Sra, 445 u's' at 371' and to minirnize any possible chilling effect

on legislative debate' the court will grant defendants' uotion for a

protectiveorderanddirectthatthetranscriPtsofthedePositionsbe

sealed uPon filing with the court'

SO ORDERED 4-

emJ

;;iffii iiimrct rUDGE

JanuarY 5, 1982'

:*H,,#l#'.fii.HfT,l

#E::riDffi

I

I

I

Page 2

6rty q"tt'