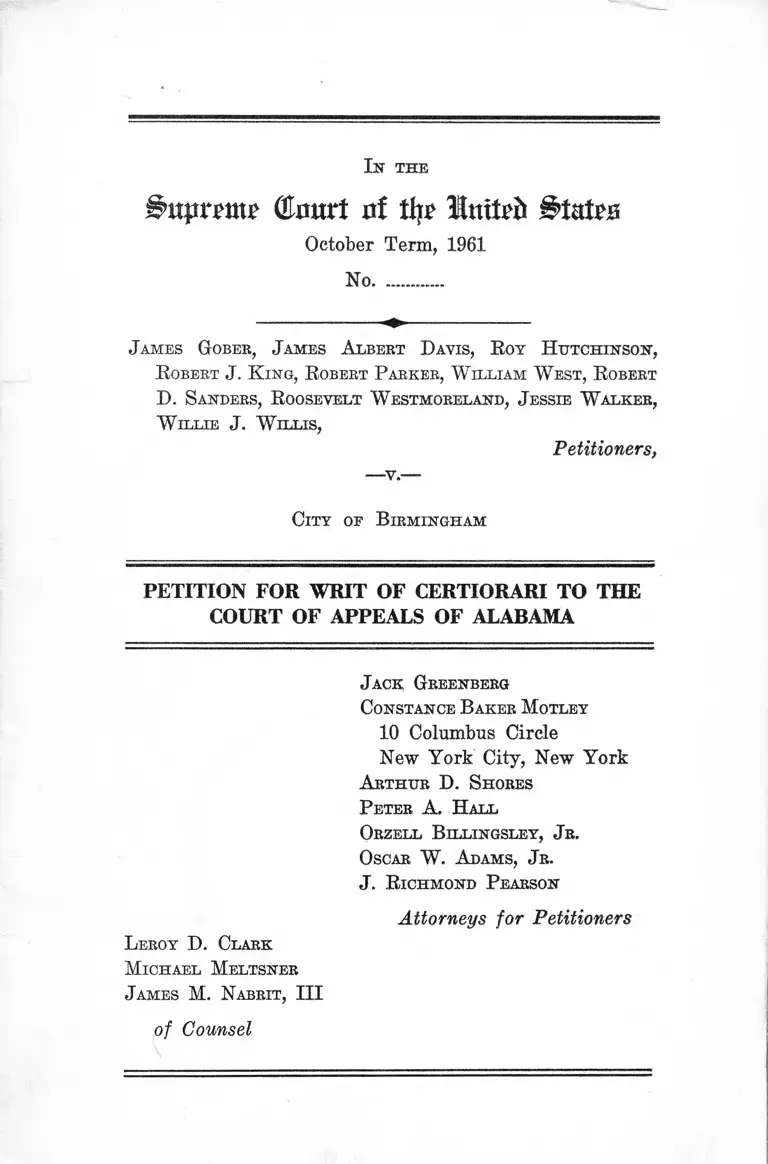

Gober v. City of Birmingham Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Alabama Court of Appeals

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gober v. City of Birmingham Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Alabama Court of Appeals, 1961. eaca3f7d-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e3d24fc7-7ceb-49d4-8c30-98c7409e99b8/gober-v-city-of-birmingham-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-alabama-court-of-appeals. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

©curt at th ̂ States

October Term, 1961

No. ...........

J ames Gobee, J ames Albert Davis, R oy H utchinson,

R obert J . K ing, R obert P arker, W illiam W est, R obert

D. Sanders, Roosevelt W estmoreland, J essie W alker,

W illie J . W illis,

Petitioners,

City of B irmingham

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York City, New York

Arthur D. Shores

P eter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

Oscar W. Adams, J r.

J . R ichmond P earson

Attorneys for Petitioners

L eroy D. Clark

Michael Meltsner

J ames M. Nabrit, III

of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Citations to Opinion Below ........... ............................... 1

Jurisdiction ..................... 2

Questions Presented ................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 3

Statement ............... ........... ........................................ ........ 4

Gober and Davis......................... 5

Hutchinson and King .... 8

Parker and West ................................ 9

Sanders and Westmoreland.................................. 10

Walker and Willis ............................................... . 12

Facts in Common ......................... ............ ........... 12

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below................................. .................................. ....... 14

Reasons for Granting the Writ ............................. ........ 18

I. Petitioners were denied due process of law and

equal protection of the laws by conviction of

trespass for refusing to leave white dining

areas where their exclusion was required by

City ordinance ....................... 18

II. Petitioners were denied due process and equal

protection by convictions for trespass for re

fusal to leave whites-only dining areas of de

partment stores in which all persons are other

wise served without discrimination ..... 23

PAGE

n

III. The convictions deny due process of law in that

they rest on an ordinance which fails to specify

that petitioners should have obeyed commands

to depart given by persons who did not estab

lish authority to issue such orders at the time

given .................................................... .............. 27

IV. The decision below conflicts with decisions of

this Court securing the right of freedom of

expression under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United S tates.......... 30

Conclusion ...................................................................... 34

A ppendix :

Judgment Entry in Gober Case ............................ la

Opinion in the Alabama Court of Appeals (in

Gober Case) ......................................................... 4a

Order of Affirmance in Gober Case ............... 13a

Order Denying Application for Eehearing in Gober

Case ................................................................. 14a

Order Denying Petition for Writ of Certiorari to

the Court of Appeals in Gober Case .......... ....... 15a

Order Denying Eehearing in Gober Case .......... 16a

Judgment Entry in Eoosevelt Westmoreland Case 17a

Order of Affirmance in Eoosevelt Westmoreland

Case ...................................................................... 20a

Order Denying Eehearing in Eoosevelt Westmore

land Case ............................................................. 21a,

PAGE

I l l

Order Denying Petition for Writ of Certiorari in

Roosevelt Westmoreland Case ........................ . 22a

Order Denying Rehearing in Roosevelt Westmore

land Case .................................................. ........... 23a

Table oe Cases

Abie State Bank v. Bryan, 282 U.S. 765 ....... ............. 8

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616.......... ...... ........ 30

Adams v. Saenger, 303 U.S. 59 .......... .......................... 8

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ...... 22

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 280 F. 2d

531 (5th Cir. 1960) ........... ........... .......................... 22

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U.S. 622 ....... .................... 31

Browder v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) ____ ____ ___ 25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ................. 22

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 ......... ...................22, 24

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 .................................................. ..................... 22,23,26

Central Iron Co. v. Wright, 20 Ala. App. 82, 101 So.

815 ............................ ......................................... ......... 29

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385 .... 28

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ............... ........................... 33

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala. 1949) aff’d

336 U.S. 933 .......... .......... ....................................... 21

Frank v. Maryland, 359 U.S. 360 ................... ................ 27

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, Washington Superior

Court, 45 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959) ................. 33

PAGE

IV

Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207 ..........5, 24, 29, 30, 31

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903, aff’g 142 F. Supp. 707

(M.D. Ala, 1956) ......................................................... 22

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 .......................... 21

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 ......................... 22

Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U.S. 349 .... 27

Junction R.R. Co. v. Ashland Bank, 12 Wall. (U. S.) 226 8

Lambert v. California, 355 U.S. 225 ............................ 28

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 .......................... ..... ....... 21

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451............................ 28

Louisiana State University and A. & M. College v.

Ludley, 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert, denied

358 U.S. 819 ........ ,....................................................... 21

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 ...... .................................... 26

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 ................................24, 32

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141 ................................ 31

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U.S. 877 ........................................................................ 22

McCord v. State, 79 Ala. 269 ....................................... 29

Monkv. Birmingham, 87 F. Supp. 538 (N.D. Ala, 1949)

aff’d 185 F. 2d 859, cert, denied 341 U.S. 940 .......... 7

Morissette v. United States, 342 U.S. 246 ..................... 29

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 ............................ 30

N.L.R.B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258

(8th Cir. 1945) ......................................................... 32

N.L.R.B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U.S. 240 .......... 32

Owings v. Hull, 9 Peters (U. S.) 607 ............................ 8

People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N.Y.S. 2d 277 (1948) 32

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497 ........................................... 27

PAGE

V

Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 8 8 ..................... 26

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 324 U.S. 793 .... 32

San Diego Bldg. Trades Council v. Garmon, 349 U.S.

236 ........................... 32

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 ..................... . 33

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947), cert,

denied 332 U.S. 851 ................................................. 33

Shell Oil v. Edwards, 263 Ala. 4, 88 So. 2d 689 (1955) .. 7

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .......................... ...... . 24

Smiley v. City of Birmingham, 255 Ala. 604, 52 So. 2d

710 (1961) ............................................... 7

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 .................................... 34

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U.S. 533 ...... 22

State of Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City Court,

44 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2357 (1959) ........................ 33

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 .................. ...... 30

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 ................................ 33

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 326 U.S. 199 .............. 29

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 ............................ 30, 32

United States v. Willow River Power Co., 324 U.S.

499 ....... ...................... ............................._.................. . 24

United Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F.2d 593 (D.C.

Cir. 1956), reversed on other grounds, 357 U.S. 357 .. 32

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624 ........................................ ........................ 30

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 ........................ . 34

Williams v. Hot Shoppes, Inc., 293 F. 2d 835 (D.C.

Cir. 1961) ................................ ............. ................. _____ 22

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d

845 (4th Cir. 1959) ........................ ......... ................. 22

PAGE

VI

Statutes

United States Code, Title 28, §1257(3) ..................... 2

Alabama Constitution, §102 ......................................... 25

Alabama Constitution, §111, amending §256 .............. 25

Code of Alabama, Title 1, §2 ......................... .......... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 7, §429(1) (1940) ................ 7

Code of Alabama, Title 14, §§360-361 ............... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 14, §426 ............... 29

Code of Alabama, Title 44, §10 . 25

Code of Alabama, Title 45, §4 ........................ 25

Code of Alabama, Title 45, §§121-123, 52, 183 ... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 45, §248 ..................... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 46, §189(19) .... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 48, §§186, 196-197, 464 . 25

Code of Alabama, Title 48, §301 (31a, b, c) .... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 51, §244 ........ 25

Code of Alabama, Title 52, §24 ...................... 25

Code of Alabama, Title 52, §§452-455 ............. 25

Code of Alabama, Title 52, §455(1)-(4) .......... 25

General City Code of Birmingham, §369 (1944) .....3, 7,15

General City Code of Birmingham, §1436 (1944) ....3,5,14

Otheb A uthorities

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tentative

Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment ................................ 29

Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Columbia L. Rev.

55 (1933) ...................................................................... 29

PAGE

I n t h e

( ta r t of tfft Hnttrd States

October Term, 1961

No.............

J ames Gober, J ames Albert Davis, R oy H utchinson,

R obert J . K ing, R obert P arker, W illiam W est, R obert

D. Sanders, R oosevelt W estmoreland, J essie W alker,

W illie J . W illis,

Petitioners,

—v.—

City of B irmingham

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

Petitioners pray that writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Alabama Court of Appeals entered

in the above entitled cases as set forth in “Jurisdiction,”

infra.

Citation to Opinion Below*

The opinion of the Alabama Court of Appeals is not re

ported, and is set forth in the Appendix hereto infra p. 4a.

The denial of certiorari by the Supreme Court of Alabama

is unreported and appears in the Appendix, infra, p. 22a.

* The Appendix contains the following opinions and orders in

Gober: Judgment; Opinion of Alabama Court of Appeals; Judg

ment, Alabama Court of Appeals; Denial of Rehearing, Alabama

Court of Appeals; Denial of Certiorari, Supreme Court of Ala

bama; Denial of Rehearing on Petition for Writ of Certiorari,

Supreme Court of Alabama. All other cases were affirmed on au

thority of Gober. Pertinent orders and opinions are set forth for

the Westmoreland case; all the orders and opinions in the other

cases are identical and, therefore, are omitted.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the Alabama Court of Appeals were

entered on May 30, 1961 (Gober 57, Davis '60, Hutchinson

/X / 4 -fr 1 7 6 /ft- X S . o

42) King 42, Parker 45, Westg41, Sanders 36, Westmore

land 36, Walker 36, Willis 38); Appendix p. 13a infra.

Petitions to the Supreme Court of Alabama for Writs of

Certiorari were denied on September 14, 1961 (Gober 7-2,

Davis 67, Hutchinson 47, King 46, Parker 46, West 50,

Sanders 42, Westmoreland 36, Walker 48, Willis 39), infra,

p. 15a.

Applications to the Supreme Court of Alabama for re~7J

hearing^were overruled on November 2, 1961 (Gober 74,

Davis 69, Hutchinson 40, King ^ Parker 48, West 52,

Sanders 44, Westmoreland 40, Walker 45, Willis ,41), infra,

p. 16a.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

United States Code 28, Section 1257(3), petitioners having

asserted below, and asserting here, the deprivation of their

rights, privileges, and immunities secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Whether Negro petitioners were denied due process of

law and equal protection of the laws secured by the Four

teenth Amendment:

1. When arrested and convicted of trespass for refusing

to leave department stores’ dining areas where their ex

clusion was required by an Ordinance of the City of

qP Birmingham which orders segregation in eating facilities.

2. By conviction of trespass for refusal to leave whites-

only dining areas of department stores in which all per

sons are otherwise served without discrimination.

3

3. When arrested and convicted of trespass for seeking

nonsegregated food service at whites-only dining areas

upon records barren of evidence that any person making

the requests to leave identified his authority to make the

request.

4. Whether petitioner sit-in demonstrators were denied

freedom of expression secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment when arrested and convicted for trespass upon re

fusal to move from whites-only dining areas where the

managers did not call the police or sign any affidavit or

warrant demanding prosecution and were apparently will

ing to endure the controversy without recourse to criminal

process.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. 2

2. This case also involves the following sections of the

City Code of Birmingham, Alabama:

“Section 1436 (1944), After Warning. Any person who

enters into the dwelling house, or goes or remains on

the premises of another, after being warned not to

do so, shall on conviction, be punished as provided

in Section 4, provided, that this Section shall not

apply to police officers in the discharge of official

duties.

Section 369 (1944), Separation of races. It shall be

unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place for

the serving of food in the city, at which white and

colored people are served in the same room, unless

such white and colored persons are effectually sep

arated by a solid partition extending from the floor

4

upward to a distance of seven feet or higher, and un

less a separate entrance from the street is provided

for each compartment” (1930, Section 5288).

;y |

Statement

These are ten sit-in protest cases tried in five separate

trials.1 2 The protests—involving common facts relevant to

the Constitutional issues here presented—occurred the same

day in five department stores in each of which two peti

tioners were arrested and charged with commission of the

same acts; all were sentenced identically in a common

sentencing proceeding (Gober 52-56, Davis 51-55; Hutchin

son 34-38, King 34-38; Parker 36-40, West 33-37; Sanders

28-32, Westmoreland 25-29; Walker 28-32, Willis 25-29)2

after trials held seriatim with the same judge, prosecution,

and defense counsel. Identical constitutional and state law

questions were raised in each case. See infra, pp. 14-18.

The Alabama Court of Appeals wrote an affirming opinion

for the first case, Gober v. State of Alabama, see infra,

p. 4a, affirming all others in brief per curiam orders merely

citing Gober, see infra, p. 20a. The Supreme Court of

Alabama denied certiorari in all cases in identical orders.3

1 While there are ten separate records there is a single tran

script of testimony for each pair of defendants arrested in a single

establishment (or five transcripts in all) of which a carbon copy

appears in the record of each one of the pair.

2 The sentencing portion of each of the ten records is identical.

Record citations are indicated by the name of the defendant and

the page.

3 A sixth pair of cases, Billups v. State of Alabama and Shuttles-

worth v. State of Alabama, arose in connection with the same situa

tion, but presents somewhat different issues in that Billups and

Shuttlesworth were convicted of having persuaded the petitioners

bringing this petition to engage in the sit-in protests which are

the subject of this petition. These two men were sentenced in the

same proceeding as the instant petitioners. A separate petition for

certiorari is being filed concerning Billups and Shuttlesworth.

5

See infra, pp. 15a, 22a. Hence, for convenient presentation,

although each pair of cases differs somewhat, the issues are

brought here by petition for writ of certiorari in a single

document. Cf. Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207, 211.

Petitioners were convicted in the Recorder’s Court of

the City of Birmingham for having trespassed after warn

ing in violation of City Code of Birmingham, Alabama,

§1436 (1944):

“Sec. 1436, After Warning. Any person who enters

into the dwelling house, or goes or remains on the

premises of another, after being warned not to do so,

shall on conviction, be punished as provided in Sec

tion 4, provided, that this Section shall not apply to

police officers in the discharge of official duties.”

Upon conviction they received trials de novo in the

Circuit Court of Jefferson County, were again adjudged

guilty, and sentenced to thirty days hard labor and $100.00

fine. (Gober 8, Davis 8-9; King 8-9, Hutchinson 8-9;

Parker 8-9, West 5-6; Sanders 8-9, Westmoreland 5-6;

Walker 8-9, Willis 5-6.)

Each complaint charged that petitioner “ . . . did go or

remain on the premises of another, said premises being

the area used for eating, drinking and dining purposes

and located within the building commonly and customarily

known as [the store in question] after being warned not

to do so, contrary to and in violation of Section 1436 of

the General City Code of Birmingham of 1944.” (Gober 2,

Davis 2; King 2, Hutchinson 2; Parker 2, West 2; Sanders

2, Westmoreland 2; Walker 2, Willis 2.)

Gober and Davis

The Gober and Davis cases arose from a sit-in protest

at Pizitz’s Department Store, Birmingham. Davis, on

6

March 31, purchased socks, toothpaste and handkerchiefs

at Pizitz’s, and with Gober attempted to order at the lunch

counter, but the waitress refused to approach (Gober 42,

Davis 43). Without identifying himself a man informed

them that Negroes could be served elsewhere in the store,

but did not ask them to leave the store or where they were

sitting (Gober 19-22, Davis 20-23). No sign indicated a

segregation policy or that the counter was solely for whites

(Gober 50, Davis 50).

That morning, Police Officer Martin testified, a superior

had reported (Gober 17, Davis 18) a disturbance at Pizitz’s

to him; he went to the dining area, found it closed to cus

tomers, and saw two Negro males seated conversing to

gether. No one spoke to them in Martin’s hearing, neither

did he speak to any person in the store (Gober 15-17,

Davis 16-18). He arrested them (Gober 17-18, Davis 17-19).

The store’s controller, Gottlinger (Gober 19, Davis 20),

saw two Negro boys seated in the lunch area, said nothing

to them, but heard one say “we should call the police”

(Gober 19, Davis 20).

This witness observed an assistant to the store president

speak to the boys, asking that they leave the tea room,

informing them they could be served in the basement Negro

restaurant because “it would be against the law to serve

them there” in the tea room area (Gober 22, Davis 23).

Here, in the first case tried, petitioners tried to inter

rogate concerning the segregation ordinance of the City

of Birmingham (Gober 22-24; Davis 23-25):

“Mr. Hall: . . . It is our theory of this case it is

one based simply on the City’s segregation ordinance

and Mr. Gottlinger, Mr. Pizitz, the police officers and

everybody involved acted simply because of the segre

gation law and not because it was Pizitz policy. . . .

* . * * # #

7

“Mr. Hall: As I understand it it is the theory of

the City’s case, it is trespass after warning. Our con

tention is that that is not a fact at all, it is simply an

attempt to enforce the segregation ordinance and we

are attempting to bring it out.

“The Court: Hoes the complaint cite some statute?

“Mr. Hall: Trespass after warning. If we went only

on the complaint it would seem that some private

property has been abused by these defendants and

that the owner of this property has instituted this

prosecution. From the witness’ answers it doesn’t seem

to be the case. It seems it is predicated on the segre

gation ordinance of the City of Birmingham rather

than on the trespass. So what we are trying to bring

out is whether or not the acts of Pizitz were based on

the segregation ordinance or something that has to do

with trespass on the property.”

(And see Parker 25-28, West 22-25.)

The Birmingham Segregation Ordinance to which coun

sel referred is General City Code of Birmingham §369

(1944),4 requiring that Negroes and whites be separated

4j§‘Sec. 369. Separation of races.

It shall be unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place

for the serving of food in the city, at which white and colored

people are served in the same room, unless such white and

colored, persons are effectually separated by a solid partition

extending from the floor upward to a distance of seven feet

or higher, and unless a separate entrance from the street is

provided for each compartment” (1930, §5288).

This ordinance is judicially noticeable by the Alabama courts,

7 Code of Alabama, 1940, §429(1). See 8'hell Oil v. Edwards, 263

Ala. 4, 9, 88 So. 2d 689 (1955) ; Smiley v. City of Birmingham,

255 Ala. 604, 605, 52 So. 2d 710 (1951). “The act approved June

18, 1943, requires that all courts of the State take judicial knowl

edge of the ordinances of the City of Birmingham.” Monk v.

Birmingham, 87 F. Supp. 538 (N. D. Ala. 1949), aff’d 185 F. 2d

859, cert, denied 341 U. S. 94(5J And this Court takes judicial notice

8

in restaurants by solid partition and that they have sep

arate entrances. The evidence was excluded (Gober 24,

Davis 25).

Gottlinger did not call the police (Gober 24, Davis 25);

when asked by the police whether he witnessed the episode,

petitioners already had been arrested and were being es

corted out of the store by the police (Gober 24, 25; Davis

25, 26). It does not appear that any store official summoned

the police or made a complaint (Gober 24, 25; Davis 25, 26).

Hutchinson and K ing

Police Officer Martin proceeded to Loveman’s Depart

ment Store, Birmingham, along with Officer Holt who told

him to accompany him on his motorcycle (Hutchinson 17,

King 17). At the dining area entrance Martin found a

rope tied from one post to another; a sign stated the area

was closed. (Ibid.) He saw two Negro boys at a table

but had no conversation “ . . . other than to tell them that

they were under arrest”. (Ibid.)

He did not know of his own knowledge that anyone from

Loveman’s had asked them to leave (Hutchinson 18, King

18). Apparently at the same time Police Lt. Purvis ap

proached Mr. Schmid, the dining area concessionnaire,

stating that “ . . . someone called us that you had two

people in here that were trying to be served . . . ” Schmid

pointed to petitioners (Hutchinson 22, King 22).

The Protective Department had been notified because,

as Mr. Schmid testified, “naturally”, in this case, there was

a “disturbance of the peace” (Hutchinson 22, King 22).

The only disturbance, however, was that “ . . . the waiters

of laws which the highest court of a state may notice. Junction

B.B. Co. v. Ashland Bank, 12 Wall. (U. S.) 226, 230; Abie State

Bank v. Bryan, 282 U. S. 765, 777, 778; Adams v. Saenger, 303

U. S. 59; Owings v. Hull, 9 Peters (U. S.) 607, 625.

9

left the floor.” {Ibid.) Petitioners were not boisterous or

disorderly (Hutchinson 28, King 28).

Mr. Kidd of the Protective Department who apparently

was in charge of the situation at no time spoke to peti

tioners (Hutchinson 25, King 25). He merely asked the

white persons there to leave. {Ibid.) Neither did he call

the police, but was notifying patrons that the restaurant

was closed when they arrived. So far as he knew no one

called the police (Hutchinson 26, 29, King 26, 29).

Loveman’s invites the general public to trade and sells

general merchandise (Hutchinson 31, King 31). Its eating

facilities, however, are for whites only (Hutchinson 24,

King 24).

Parker and W est

Police Officer Myers received a radio call from head

quarters to proceed to Newberry’s, Birmingham; visited

the eating area and found “Two colored males [petitioners

West and Parker] were sitting at the lunch counter”,

which was “out of the ordinary” (Parker 16-17, West

13-14). He did not speak with them nor did they converse

with any store employee in his presence (Parker 17, West

14), but he arrested them for trespass after warning, it

having been his “understanding” that his partner had re

ceived a complaint from a Mr. Stallings, whose capacity

at the store the witness did not know, nor did the witness

know whether he was employed there (Parker 18-19, West

15-16).

West had met Parker at the store where West had pur

chased some paper and small comic books (Parker 29,

West 26). When they seated themselves some white people

were eating, but petitioners were not served (Parker 30,

West 27). No sign at the counter indicated service for

10

whites only. {Ibid.) (At a Negro counter elsewhere in the

store a sign stated “for colored only”. (Parker 24, West

21).) The officers, upon arrival, ordered the white people

to get up, but all did not leave (Parker 31, West 28).

Mrs. Gibbs, the store detective, told petitioners they

could be served at a Negro snack bar on the fourth floor

but not where they were seated (Parker 21, West 18).

(Nor could they be served at another lunch counter for

whites only in the basement (Parker 22, West 19).)

Assistant Store Manager Stallings also asked petitioners

to patronize the Negroes-only counter. Stallings, however,

did not call the police, but was informed that “someone”

did. He made no complaint to the police at the time of

arrest, nor subsequently, and did not know whether any

one else did (Parker 23-24, West 20-21).

Newberry’s advertises and sells merchandise to the gen

eral public. Negroes and whites shop together on the first

floor (Parker 24-25, West 21-22).

Petitioners’ counsel attempted to establish that the lunch

counter segregation policy was the City of Birmingham’s,

not Newberry’s (Parker 25-27, West 22-24). This line of

inquiry was held incompetent (Parker 27, West 24).

Sanders and W estm oreland

Officer Caldwell of the Birmingham police was called to

Kress’s five and ten cent store, Birmingham, the same morn

ing (Sanders 16, Westmoreland 13). Upon arrival he pro

ceeded to the basement and observed “two black males”

{ibid.) seated. He heard the manager inform petitioners

they could not be served, the lights were turned out and

the counter closed. Caldwell arrested them (Sanders 17,

18, Westmoreland 14, 15), but did not hear any request

11

that petitioners leave; no one in Kress’s asked him to arrest

them {ibid.).

When petitioners had seated themselves at a lunch

counter bay the steward or manager, Pearson, closed it,

informed them they could not be served, and turned out

that bay’s lights. They then requested service at a second

bay. Pearson said: “Boys, you will have to leave because I

can’t serve you and the bay is closed. We are closing”

(Sanders 19, Westmoreland 16). A woman already seated

at the counter, however, remained after “closing” and so

far as the steward knew, was not arrested and he was not

called to bear witness against her (Sanders 26, Westmore

land 23).

One petitioner told him, “Well, we have our rights”

(Sanders 19, Westmoreland 16); Pearson called the man

ager who approached the counter and asked Pearson

whether he had asked them to leave. While the witness at

this point stated that the manager asked them to leave the

store (Sanders 20, Westmoreland 17), on cross-examination

he explained:

“Q. To leave that section, yes. In the store? A.

The store was not mentioned” (Sanders 21, Westmore

land 18).

When Pearson and the manager left the bays, the police

entered, asked petitioners to get up, additional police en

tered, and the first two officers escorted petitioners from

the store. Neither Pearson nor the manager called the

police, neither asked for the arrest, neither signed the

complaint (Sanders 21-23, Westmoreland 18-20).

Kress’s is a general department store advertising to the

general public (Sanders 22, Westmoreland 19), but has no

food service facilities for Negroes (Sanders 23, Westmore

land 20), although they are solicited to and may buy food

12

to carry out (Sanders 26, Westmoreland 23). Whites and

Negroes, however, purchase from the same counters at all

other departments (Sanders 24, Westmoreland 21).

W alker and W illis

The Birmingham Police Department radio dispatched

Officer Casey to Woolworth’s. There he observed something

“unusual or out of the ordinary” : two Negro males, peti

tioners Walker and Willis, at the lunch counter (Walker

16-18, Willis 13-15). Mrs. Evans, manager of the lunch

counter, he testified, told petitioners to leave (Walker 19,

Willis 16). Neither Mrs. Evans, nor anyone from the store,

instructed him to arrest them, nor did she complain other

than to say she wanted them to leave the counter—not the

store (Walker 19, Willis 16). The police informed persons

connected with the store that “they would have to come

to headquarters or be contacted to sign a warrant” (Walker

19-20, Willis 16-17), but Officer Casey did not know whether

such a warrant was signed (ibid.).

Walker and Willis had purchased various articles and

then went to the counter (Walker 21, Willis 18). Walker

denied that Mrs. Evans had spoken to them at all and testi

fied that only the police asked him to leave (Walker 22,

Willis 19). He testified also that white persons at the

counter were served while he was seated. No white person,

however, was arrested (Walker 22, Willis 19). No signs

at the counter designated it for whites or Negroes (Walker

23, Willis 20).

Facts in Common

All the cases have salient facts in common. The protest

demonstrations occurred in department stores open to the

general public, including Negroes, but whose dining areas

were segregated (Gober 48-49, Davis 49-50; Hutchinson 24,

13

31, King 24, 31; Parker 21, 24, 25, West 18, 21, 22; Sanders

22, 23, 24, 26, Westmoreland 19, 20, 21, 23; Walker 21; Willis

18). Nevertheless, apparently no racial signs were posted

at any of the “white” dining areas (Gober 50, Davis 50;

Hutchinson 28, King 28; Parker 27, West 30; Sanders 24,

Westmoreland 21; Walker 23, Willis 30). In no case is

there evidence that a person asking petitioners to leave

identified himself as having authority to do so5 * (Gober

19-22; Davis 20-23; Hutchinson 18, 22, 25; King 18, 22, 25;

Parker 23; West 20; Sanders 19, 20; Westmoreland 16, 17;

Walker 18; Willis 15).

In each case the police immediately arrested petitioners

without a request from anyone connected with the store

(Gober 15-18, Davis 16-19; Hutchinson 18, 26, King 18,

26; Parker 23-24, W7est 20-21; Sanders 21-23, Westmore

land 18-20; Walker 19, Willis 16). In no case does it appear

that anyone connected with the store called the police or

subsequently signed a complaint, affidavit or warrant

(Gober 25, 26, Davis 24, 25; Hutchinson 29, King 29;

Parker 23-24, West 20-21; Sanders 21-23, Westmoreland

18-20; Walker 18, 19, 20, Willis 15, 16, 17). In no case

were petitioners requested to leave the store itself as op

posed to the counter area (Gober 23, Davis 22; Hutchinson

25, King 25; Parker 21, 22, West 18, 19; Sanders 20, 21,

Westmoreland 17, 18; Walker 19, Willis 16). In each case

petitioners were charged that they “did go or remain on

the premises of another, said premises being the area used

for eating, drinking and dining purposes . . . after being

warned not to do so” (Gober 2, Davis 2; Hutchinson 2,

King 2; Parker 2, West 2; Sanders 2, Westmoreland 2;

Walker 2, Willis 2).

5 In Parker and West, the store detective testified that he “iden

tified” himself (Parker 18; West 21) but he nowhere testified that

he identified himself as a person who had authority to ask them

to leave the counter or that, in fact, he had such authority or,

for that matter, as to what about himself he identified.

14

In each, case the store management was prohibited from

serving Negroes and whites in the same dining area by an

Ordinance of the City of Birmingham which compelled

racial segregation. See supra pp. 7-8, note 4, p. 7.

How the Federal Questions W ere Raised

and Decided Below

After conviction in the Recorders Court of the City of

Birmingham petitioners appealed to the Circuit Court of

the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama for trials de novo,

prior to which they filed motions to strike the complaints

and demurrers, alleging that Section 1436 of the General

City Code of Birmingham was unconstitutionally applied

to them in that while patronizing stores open to the general

public they were charged with trespass on account of race

and color contrary to the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment; that Section 1436

denied due process of law secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment in that it was unconstitutionally vague by not

requiring that the person making the demand to depart

identify his authority; that the ordinance was unconstitu

tionally applied in that they were engaged in sit-in demon

strations and were denied freedom of assembly and speech

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment (Gober, Davis;

Hutchinson, King; Parker, West; Sanders, Westmoreland;

Walker, Willis, 2-4).

The motions to strike and the demurrers were overruled;

exceptions were taken (Gober 7, Davis 8; Hutchinson, King

8; Parker 8, West 5; Sanders 8, Westmoreland 5; Walker

8, Willis 5).

During the trial of Gober and Davis, the first trials of the

series, petitioners attempted to introduce evidence that the

stores were acting in conformance to General City Code

15

of Birmingham §369 (1944), which requires racial segrega

tion in establishments serving food. This line of inquiry

was held incompetent (Gober 22-24, Davis 23-25).

At the close of the State’s evidence, petitioners moved to

exclude the evidence alleging, among other things: that

the complaints were invalid because the trespasses charged

were based solely on race, depriving them of due process

and equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth

Amendment; that petitioners were peacefully assembled to

speak and protest against the custom of racial discrimina

tion in public establishments and were prosecuted for the

purpose of denying them freedom of assembly and speech

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment; that the ordi

nance was unconstitutionally vague in not requiring that

the persons requesting petitioners leave produce any evi

dence of authority to make the demand, whereby petitioners

would be apprised of the validity of the demands to leave,

thereby, denying the petitioners due process of law under

the Fourteenth Amendment; that all of the stores involved

are vitally affected with the public interest and have as

sumed functions which the state would assume were they

not in existence, whereby denial to petitioners of equal

access to all their facilities solely because of race is a denial

of due process and equal protection under the Fourteenth

Amendment (Gober, Davis 5-7; Hutchinson, King 5-7;

Parker 5-7, West 25 (and see Parker 5-7); Sanders 5-7;

Walker 5-7, Willis 17).

The motions to exclude the evidence were overruled and

exception taken (Gober,. Davis 8; Hutchinson, King 8;

Parker 8, West 5; Sanders 8, Westmoreland 5; Walker 8,

Willis 5).

At the end of each trial petitioners moved for new trials

alleging, among other things, that: the trespass ordinance

was unconstitutionally applied to deprive them of free

16

speech, equal protection of the laws and other liberties

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution; that the Court erred in overruling

the motions to strike the complaint, the demurrers and the

motions to exclude evidence (Gober 9-11, Davis 10-12;

Hutchinson, King 10-12; Parker 10, 11, West 7, 8; Sanders

10, 11, Westmoreland 7, 8; Walker 10, 11, Willis 7, 8). The

motions for new trial were overruled (Gober 9, 11, Davis

9, 12; Hutchinson, King 9, 12; Parker 9, 12, West 6, 9;

Sanders 9, 12, Westmoreland 6, 9; Walker 9, 12, Willis 6,

9).

Appeals were taken to the Alabama Court of Appeals and

Assignments of Errors were filed against the action of the

trial court in overruling the motions to strike the complaint

(Assignment 1), the demurrers (Assignment 2), the mo

tions to exclude the evidence (Assignment 3) and. the

motions for new trial (Assignment 4) (Gober 55, Davis 58;

Hutchinson, King 41; Parker 43, West 40; Sanders 25,

Westmoreland 32; Walker 35, Willis 32).

In Gober v. City of Birmingham, 6th Division 797, Ala.

App. Ms. the Court of Appeals of Alabama wrote a full

opinion (Gober 58) and all other cases were affirmed on

the authority of Gober (Gober 58, Davis 60; Hutchinson 42,

King 42; Parker 45, West 41; Sanders 36, Westmoreland

33; Walker 36, Willis 33).

While the Court held the motions to strike the complaint

an improper means to raise a constitutional objection and

refused to consider the demurrers, it did pass upon all of

the constitutional questions raised by rejecting, adversely,

on the merits, the objections to overruling the motions to

exclude the evidence and the motions for new trial: “We

find no merit in appellant’s Assignments numbers 3 and 4”

(Gober 64).

Specifically the court held that petitioners had not been

denied freedom of speech:

17

“Counsel has argued, among other matters, various

phases of constitutional law, particularly as affected

by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Consti

tution, such as freedom of speech, in regard to which

counsel stated: ‘What has become known as a “sit-in”

is a different, but well understood symbol, meaningful

method of communication.’ Counsel has also referred

to cases pertaining to restrictive covenants. We con

sider such principles entirely inapplicable to the pres

ent case” (Gober 62).

Further, the court held the petitioners had not been denied

due process and equal protection of the laws secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment:

“The right to operate a restaurant on its own prem

ises under such conditions as it saw fit to impose was

an inalienable property right possessed by the Pizitz

store. The appellant would destroy this property right

by attempting to misapply the Fourteenth Amendment,

ignoring the provision in that Amendment that grants

the right to a private property owner to the full use.

of his property, that is : ‘Nor shall any state deprive

any person of life, liberty or property without due

process of law’ ” (Gober 63).

Moreover:

“As stated in Williams v. Howard Johnson Restau

rant (C.C.A. 4), 368 Fed. 2d 845, there is an ‘important

distinction between activities that are required by the

State and those which are carried out by voluntary

choice and without compulsion by the people of the

State in accordance with their own desires and social

practices’ ” (Gober 64).

18

Applications for rehearing before the Court of Appeals

were overruled (Gober 66, Davis 61; Hutchinson, King 43;

Parker 46, West 42; Sanders 37, Westmoreland 34; Walker

37, Willis 34). Writs of certiorari, sought in the Supreme

Court of Alabama, were denied (Gober 72, Davis 67;

Hutchinson 47, King 48; Parker 46, West 50; Sanders 42,

Westmoreland 38; Walker 43, Willis 39). Applications for

rehearing before the Supreme Court of Alabama were over

ruled (Gober 74, Davis 69; Hutchinson 49, King 50; Parker

48, West 52; Sanders 44, Westmoreland 40; Walker 45,

Willis 41).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The court below decided these cases in conflict with prin

ciples declared by this Court as is further set forth below:

I.

Petitioners were denied due process o f law and equal

protection o f the laws by conviction o f trespass for

refusing to leave white dining areas where their exclu

sion was required by City ordinance.

Despite the fact that petitioners ostensibly were con

victed for “trespass after warning” they actually were

sentenced to jail and fined by Alabama for having violated

the segregation policy of the City of Birmingham. This

policy is expressed in the General Code of Birmingham

§369 (1944) requiring all eating establishments to main

tain separate facilities for Negroes and whites “ . . . sep

arated by a solid partition extending from the floor up

ward to a distance of seven feet or higher . . . ” and re

quiring that separate entrances be maintained for each

race. Efforts to establish by evidence that this ordinance

prevented the managers of the stores from rendering the

19

nonsegregated service sought by petitioners was excluded

at the trial in the very first of the cases tried (G-ober 22-23,6

Davis 23-24).

Moreover, corollary efforts to inquire concerning whether

exclusion from the dining areas was demanded pursuant

to the policy of the stores as distinct from that of the City

also were rejected. Counsel for petitioners argued to the

trial court:

“The meat in this coconut is whether or not the New

berry’s Department Store has complained or the City

of Birmingham. It is our theory of the case it is nec

essary for the owner of the premises to be complain

ing and we are trying to find out if they have com

plained.”

(And see the remainder of the colloquy (Parker 25-27,

West 22-24).) But whether the stores desired not to serve

was held inadmissible {Ibid.).

Indeed, in the King and Hutchinson cases no one con

nected with management had expressly asked petitioners—

as distinct from white patrons—to leave the dining area.

Rather, it was announced “in general terms that the tea

room was closed and for everyone please to leave” (King

20, Hutchinson 20). Yet, twenty-five “whites were still sit

ting there when the two Negroes were there, when the

police officers came” (King 23, Hutchinson 23). But, while

petitioners were arrested summarily, it does not appear

that any of the whites were arrested {Ibid.). White per

sons merely were requested to leave.

Further confirmation that the policy of enforcing seg

regation was the City’s, appears from how the arrests were

made. The police proceeded to the stores in question and

See pp. 6-8, supra.

20

without requests to arrest by the management (See “Facts

in Common,” supra p. 12), immediately arrested peti

tioners. There is no evidence that anyone connected with

the stores called the police {Ibid.). And petitioners were

arrested even when police had no knowledge that anyone

had refused to serve (King 23, Hutchinson 23) or had

asked them to leave the dining area (Gober 15-17, Davis

16-18; Parker 16-17, West 13-14). The conduct of the

stores in these circumstances gives rise to an inference

that the store managers were willing to tolerate the dem

onstrations. As Mr. Justice Harlan has written. There was:

“ . . . the reasonable inference . . . that the management

did not want to risk losing Negro patronage in the

stores by requesting these petitioners to leave the

‘white’ lunch counters, preferring to rely on the hope

that the irritations of white customers or the force

of custom would drive them away from the counters.

This view seems the more probable in circumstances

when, as here, the ‘sitters’ ’ behaviour was entirely

quiet and courteous, and, for all we know, the counters

may have been only sparsely, if to any extent, occupied

by white persons.” Garner v. Louisiana, 30 U. S. L.

Week 4070, 4082 (Mr. Justice Harlan concurring).

If the stores were willing to cope with the controversy

within the realm of social and economic give and take,

Birmingham had no constitutional authority to intervene as

an enforcer of segregation.

The discriminatory practices in these stores, the de

mands that petitioners leave and their arrests and convic

tions, result, therefore, directly from the formally enacted

policy of the City of Birmingham, Alabama, and not (so

far as this record indicates) from any individual or cor

porate decision or preference of the management of the

21

stores to exclude Negroes from the lunch counters. What

ever the choice of the property owners may have been, here

the City made the choice to exclude petitioners from the

property through its segregation ordinance. This city seg

regation policy was enforced by petitioners’ arrests, con

victions, and sentences of imprisonment in the Alabama

courts.

The Alabama Court of Appeals dismisses reference to

the city segregation ordinance by stating “there is no ques

tion presented in the record before us, by the pleading,

of any statute or ordinance requiring the separation of the

races in restaurants. The prosecution was for a criminal

trespass on private property” (Gober 63). (All other con

victions were affirmed on authority of Gober.) But the

Constitution forbids “sophisticated as well as simple-

minded modes of discrimination” Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S.

268, 275..

By enacting, first, that persons who remain in a restau

rant when the owner demands that they leave are “tres

passers,” and then enacting that restaurateurs may not

permit Negroes to remain in white restaurants, the City

has very clearly made it a crime (a trespass) for a Negro

to remain in a white restaurant.7

Exclusion by the trial court of evidence concerning the

ordinance and the policy of the City of Birmingham does

not negate the fact that Birmingham is enforcing segrega

tion. By Alabama statute all courts of the State are “re

quired” to take judicial notice of the ordinance of the City

7 Racial segregation imposed under another name often has been

condemned by this Court. Guinn v. U. 238 U.S. 347; Lane v.

Wilson, supra; Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala. 1949)

aff’d 336 U.S. 933; and see Louisiana State University and A. & M.

College v. Ludley, 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 358

U.S. 819.

22

of Birmingham. This Court can and will judicially notice

matter that the courts below could notice.8

The case thus presents a plain conflict with numerous

prior decisions of this Court invalidating state efforts to

require racial segregation. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S.

60; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483; Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U.S. 903, aff’g 142 F. Supp. 707, 712 (M.D.

Ala. 1956); Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879; Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877;

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U.S. 533; Cf.

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715.

Note the dissenting opinion of Judges Bazelon and Edger-

ton in Williams v. Hot Shoppes, Inc., 293 F. 2d 835, 843

(D.C. Cir. 1961) (dealing primarily with the related issue of

whether a proprietor excluding a Negro under an errone

ous belief that this was required by state statute was liable

for damages under the Civil Rights Acts; the majority ap

plied the equitable abstention doctrine). Indeed, Williams

v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845, 847 (4th

Cir. 1959), relied upon by the Alabama Court of Appeals

below, indicated that racial segregation in a restaurant “in

obedience to some positive provision of state law” would

be a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. See also

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 280 F. 2d 531

(5th Cir. 1960) ; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th

Cir. 1961).

See Note 4, supra.

23

II.

Petitioners were denied due process and equal pro

tection by convictions for trespass for refusal to leave

whites-only dining areas o f department stores in which

all persons are otherwise served without discrimination.

Even should the convictions be viewed as enforcing an

alleged “inalienable property right” (Opinion of the Ala

bama Court of Appeals, Gober 63) to order customers about

within a store the judgments below conflict with principles

declared by this Court.

The state by arrest and criminal conviction has “place [d]

its authority behind discriminatory treatment based solely

on color . . . ” Mr. Justice Frankfurter dissenting in

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 727,

by enforcing a policy of deploying customers within a store

on the basis of race. This appears immediately from the

complaints, all of which describe the premises upon which

petitioners allegedly trespassed as the “area used for eat

ing, drinking and dining purposes and located within the

building commonly and customarily known as . . . ” (em

phasis supplied). (See, e.g., Gober 2.) No question arose

about the legality of petitioners’ presence within the stores

—indeed, their patronage was actively solicited—but only

whether for reasons of race they might be convicted for

failure to move from particular portions of each store

where they sought sit-down food service. And when peti

tioners were asked to leave, they were rejected from the

dining areas only—not the stores. Moreover, in the cases

of Hutchinson and King (Hutchinson 25, King 25) they

were not even asked to leave the dining areas. We have

here, therefore, the state racially re-arranging by means

of a trespass ordinance the customers within a single store.

24

Petitioners submit that the state’s interest in maintain

ing such a “property” right is hardly sufficient to negate

the well-established principle that the Fourteenth Amend

ment forbids government to enforce racial discrimination.

That private property may be involved hardly settles a

claim that Fourteenth Amendment rights have been denied.

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 506; Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U.S. 60, 74; United States v. Willow River Power Co.,

324 U.S. 499, 510; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1. The

stores were open generally to the public, advertised, and

solicited it to purchase generally. The stores were “part

of the public life” of the community. Garner v. Louisiana,

supra at 7 L. ed. 2d 222 (Mr. Justice Douglas concur

ring). Negroes and whites were served without distinction

except at lunch counters where Negroes were served only

in separate sections or were permitted to purchase food to

take out. None of the lunch counters contained signs ex

cluding Negroes. All were integral parts of the establish

ments into which petitioners were invited. Petitioners

sought to use the dining areas in their usual, intended

manner. None of the dining sections were treated by the

proprietors themselves as private in any sense except that

upon being seated Negroes were denied service. Thus, the

“property” right which the state has enforced is a “right”

to discriminate among patrons on the basis of race in one

particular aspect of the service of a single establishment.

But beyond this, the record demonstrates that the alleged

property right being enforced was not in reality being as

serted by private proprietors—it was a manifestation of

state policy. This policy is, first of all and most clearly,

expressed in the Birmingham restaurant segregation Or

dinance §369. It is manifested also in a massive statutory

and state constitutional structure which impresses segre-

25

gation on innumerable activities of all of the citizens of

Alabama.

See, Alabama Constitution §111 amending §256 (nothing

in the Constitution to be construed as creating a right to

public education; legislature authorized to provide for

education taking into account the preservation of “peace

and order” and may authorize parents to send their chil

dren to schools “for their own race”). Code of Alabama

Title 1 §2 (defines “Negro” and “Mulatto”) ; Title 52 §24

(authorizes appointment of an Advisory Board for Negro

Educational Institutions); Title 52 §§452-455 (maintenance

of Alabama A. & M. Institute for Negroes); Title 52

§455(1)-(4) (maintenance of Tuskegee Institute for

Negroes only); Title 45 §248 (schools for the mentally

deficient to be built taking into account separation of the

races); Title 45 §4 (prisoners in tubercular hospitals to

be separated on basis of race); Title 14 §§360-361 (mar

riage, adultery and fornication between Negroes and whites

a felony; officer issuing license for such a marriage commits

misdemeanor). Alabama Constitution §102 (legislature

may never permit interracial marriages). Title 46 §189(19)

(white women may not act as nurses in any public or

private hospital where Negro men are patients); Title 44

§10 (county homes for the poor to be segregated); Title 51

§244 (a breakdown of the poll tax on the basis of race must

be taken); Title 45 §§121-123, 52, 183 (white and Negro

prisoners must be separated); Title 48 §§186, 196-197, 464

(Negroes and whites must be separated in railroad coaches

and waiting rooms); Title 48 §301 (31a, b, c) (Negroes

and whites to be separated on intrastate buses). See Brow

der v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903 (1956).

Segregation is all of a piece. When the state decrees

and enforces it at myriad points it hardly can claim that

a proprietor who follows massive governmental policy in

26

racially segregating customers is exercising rights of “pri

vate property.”

Petitioners submit that it is “irony amounting to grave

injustice that in one part of a single building . . . all per

sons have equal rights, while in another portion, also ser

ving the public, a Negro is a second-class citizen, offensive

because of his race. . . . ” Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 724. While the excised language

(replaced by dots) in the quotation from Burton refers to

a building “erected and maintained with public funds by

an agency of the States,” 365 U. S. 715, at 724, the legal

significance of the omitted phrase, petitioners submit, wTas

to supply the Fourteenth Amendment element of state ac

tion. In Burton, where, petitioner was neither arrested nor

prosecuted, this element was furnished by the facts that,

inter alia, “the authority, and through it the state has not

only made itself a party to the refusal of service, but has

elected to place its power, property and prestige behind the

admitted discrimination.” 365 U.S. 715, at 725. In the in

stant suit state participation bites more deeply for peti

tioners have by Alabama courts been branded criminals

and relegated to “30 days hard labor for the City.”

The “property” right (racial discrimination in accord

ance with state custom supported by state law) within a

single store open to the public which Alabama seeks to

preserve by applying the Birmingham trespass ordinance,

is so narrow as to not deserve—in face of the Fourteenth

Amendment—state protection. Indeed, is the kind of “prop

erty right” which many states have taken away without,

this Court has held, denying due process of law. Railway

Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88, 93, 94. It is not the sort

of “property” right involving considerations entitled to

high constitutional protection as, for example, the right of

privacy treated in Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 and see Poe

27

v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497. Cf. Frank v. Maryland, 359 U.S.

360. Here, indeed, it is a case where the right of private

property in a store, part of the public life of the community,

should be “limited by the neighborhood of principles of

policy which are other than those on which the particular

right is founded. . . . ” Hudson County Water Co. v.

McCarter, 209 U.S. 349, 356. These principles of policy

are the principles of the Fourteenth Amendment which

forbid the state to enforce racial discrimination. To make

policemen ushers within public stores, whose duties are to

direct the respective races here and there under threat of

jail sentence, petitioners submit, far exceeds anything the

Fourteenth Amendment ever has permitted.

III.

The convictions deny due process o f law in that they

rest on an ordinance which fails to specify that peti

tioners should have obeyed commands to depart given

by persons who did not establish authority to issue

such orders at the tim e given.

In the courts below petitioners asserted that the ordi

nance in question as applied to them denied due process

of law secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States in that it did not require that

the persons requesting them to leave the dining areas estab

lished or, indeed, asserted their authority to make the

demands. In none of the ten records before this court did

the persons who demanded that petitioners leave, first

inform petitioners or demonstrate to them that they had

authority to request that the petitioners leave the areas

in question. Only in one pair of cases (Parker 18, West 21)

did the witness say that he “identified” himself. Yet there

was no evidence that he claimed authority to order peti

tioners out of the dining area, or indeed, that the witness

28

possessed such authority. No one ordinarily may he ex

pected to assume that one who tells him to leave a public

place, into which the proprietor invited him and in which

he has traded, is authorized to utter such an order when

no claim of such authority is made.

This is especially true in the case of a Negro seating

himself in a white dining area in Birmingham, Alabama—

obviously a matter of controversy and on which any

stranger might be expected to volunteer strong views. If

the statute in question is interpreted to mean that one must

leave a public place under penalty of being held a criminal

when ordered to do so by a person who later turns out to

have been in authority without a claim of authority at the

time, it means as a practical matter that one must depart

from a public place whenever told to do so by anyone; the

alternative is to risk fine or imprisonment. Such a rule

might be held a denial of due process. Cf. Lambert v.

California, 355 U.S. 225. But if such is the rule the statute

gives no fair warning; absent such notice petitioners surely

were entitled to assume that one may go about a public

place under necessity to observe orders only from those

who claim with some definiteness the right to give them.

Indeed, as a matter of due process of law, if it is the rule

one must obey all orders of strangers to leave public places

under penalty of criminal conviction if one uttering the

order later turns out to have had authority, petitioners are

entitled to more warning of its harshness than the ordi

nance’s text affirmed. Connolly v. General Construction Co.,

269 U.S. 385; Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451. Other

wise many persons—like these petitioners—may be held

guilty of crime without having intended to do wrong. This

Court has said however, that:

“The contention that an injury can amount to a crime

only when inflicted by intention is no provincial or

29

transient notion. It is as universal and persistent in

mature systems of law as belief in freedom of the hu

man will and a consequent ability and duty of the

normal individual to choose between good and evil.”

Morrissette v. U. S., 342 U.S. 246, 250.

■==-— ..- .................. ................. ....... ...... rc-'

Morrissette, of course, involved a federal statute as treated , C

in the federal courts. But it expresses the fundamental view

that scienter ought generally to be an element in criminality.

See Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Columbia L. Rev.

55, 55-6 (1933). The pervasive character of scienter as an

element of crime makes it clear that a general statute like

the ordinance now in question, in failing to lay down a

scienter requirement, gives no adequate warning of an /,

absolute liability. Trespass statutes like the one at bar

are quite different from “public welfare statutes” in which

an absolute liability rule is not unusual. See Morrissette

v. United States, supra, 342 U.S. at 252-260.

Indeed, the ordinance in question is significantly different

from Code of Alabama, Title 14, §426, which at least ex

culpates those who enter with “legal cause or good excuse”

a phrase missing from the Birmingham ordinance. Cf.

Central Iron Co. v. Wright, 20 Ala, App. 82, 101 So. 815;

McCord v. State, 79 Ala. 269; American Law Institute,

Model Penal Code, Tentative Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment.

On the other hand however, if Alabama were to read a

scienter provision into this ordinance for the first time—

which it has failed to do although the issue was squarely

presented in these ten cases—the lack of the necessary ele

ment of guilt, notice of authority, patent on the face of all

ten records, would require reversal under authority of

Garner v. Louisiana, supra; Thompson v. City of Louisville,

362 U.S. 199.

30

IY.

The decision below conflicts with decisions o f this

Court securing the right o f freedom o f expression un

der the Fourteenth Am endm ent to the Constitution o f

the United States.

Petitioners were engaged in the exercise of free expres

sion, by verbal requests to the management for service,

and nonverbal requests to the management for service,

and nonverbal requests for nondiscriminatory lunch coun

ter service, implicit in their continued remaining in the

dining area when refused service. As Mr. Justice Harlan

wrote in Garner v. Louisiana: “We would surely have to

be blind not to recognize that petitioners were sitting at

these counters, when they knew they would not be served,

in order to demonstrate that their race was being segre

gated in dining facilities in this part of the country.”

7 L. ed. 2d at 235-36. Petitioners’ expression (asking for

service) was entirely appropriate to the time and place

at which it occurred. They did not shout or obstruct the

conduct of business. There were no speeches, picket signs,

handbills or other forms of expression in the store pos

sibly inappropriate to the time and place. Bather they

offered to purchase in a place and at a time set aside for

such transactions. Their protest demonstration was a part

of the “free trade in ideas” (Abrams v. United States, 250

U.S. 616, 630, Holmes, J ., dissenting), within the range of

liberties protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, even

though nonverbal. Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359

(display of red flag); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88

(picketing); West Virginia State Board of Education v.

Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 633-634 (flag salute); N.A.A.C.P.

v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (freedom of association).

Questions concerning free speech expression are not

resolved merely by reference to the fact that private prop-

31

erty is involved. The Fourteenth Amendment right to

free expression on private property takes contour from

the circumstances, in part determined by the owner’s pri

vacy, his use and arrangement of his property. In Breard

v. Alexandria, 341 U.S. 622, the Court balanced the “house

holder’s desire for privacy and the publisher’s right to dis

tribute publications” in the particular manner involved,

upholding a law limiting the publishers’ right to solicit on

a door-to-door basis. But cf. Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S.

141 where different kinds of interests led to a correspond

ing difference in result. Moreover, the manner of assertion

and the action of the State, through its officers, its customs

and its creation of the property interest are to be taken

into account.

In this constitutional context it is crucial, therefore, that

the stores implicitly consented to the continuance of the

protest and did not seek intervention of the criminal law.

For, this case is like Garner v. Louisiana, swpra, where

Mr. Justice Harlan, concurring, found a protected area of

free expression on private property on facts regarded as

involving “the implied consent of the management” for the

sit-in demonstrators to remain on the property. In none

of the cases at bar did anyone other than the police request

petitioners to leave the store. In one pair of cases there

was not even a request to leave. the dining area. The

pattern of police action, obviously, was to arrest Negroes

in white dining areas. In no case does it appear that anyone

connected with the store called the police or subsequently

signed an affidavit or complaint. In each case the police

officer proceeded immediately to arrest the petitioners with

out any request to do so on the part of anyone connected

with the store.

In such circumstances, petitioners’ arrest must be seen

as state interference in a dispute over segregation at these

32

counters and tables, a dispute being resolved by persuasion

and pressure in a context of economic and social struggle

between contending private interests. The Court has ruled

that judicial sanctions may not be interposed to discrim

inate against a party to such a conflict. Thornhill v. Ala

bama, supra; San Diego Bldg. Trades Council v. Garmon,

349 U.S. 236.

But even to the extent that the stores may have acqui

esced in the police action a determination of free expres

sion rights still requires considering the totality of cir

cumstances respecting the owner’s use of the property and

the specific interest which state judicial action supports.

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501.

In Marsh, this Court reversed trespass convictions of

Jehovah’s Witnesses who went upon the privately owned

streets of a company town to proselytize, holding that the

conviction violated the Fourteenth Amendment. In Re

public Aviation Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 324 U.S. 793, the Court

upheld a labor board ruling that lacking special circum

stances employer regulations forbidding all union solicita

tion on company property constituted unfair labor prac

tices. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra, involving picketing

on company-owned property; see also N.L.R.B. v. American

Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258 (8th Cir. 1945); United

Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F. 2d 593, 598 (D.C. Cir.

1956), reversed on other grounds, 357 U.S. 357, and com

pare the cases mentioned above with N.L.R.B. v. Fansteel

Metal Corp., 306 U.S. 240, 252, condemning an employee

seizure of a plant. In People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86

N.Y.S. 2d 277, 279 (1948) the Court held that picketing

within Pennsylvania Railroad Station was not a trespass;

the owners opened it to the public and their property rights

were “circumscribed by the constitutional rights of those

whose use it.” See also Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union,

33

Washington Superior Court, 45 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2334

(1959); and State of Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City

Court, 44 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2357, 2361 (1959).-

In the circumstances of this case the only apparent

state interest being subserved by these trespass prosecu

tions is support of the property owner’s discrimination in

conformity to the State’s segregation custom and policy

and the express terms of the City Ordinance. This is all

that the property owner can be found to have sought.

Where free expression rights are involved, the question

for decision is whether the relevant expressions are “in

such circumstances and . . . of such a nature as to create

a clear and present danger that will bring about the sub

stantive evil” which the state has the right to prevent.

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47, 52. The only “sub-~"~

stantive evil” sought to be prevented by these trespass

prosecutions is the stifling of protest against the elimination

of racial discrimination, but this is not an “evil” within-—)

the State’s power to suppress because the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits state support of racial discrimina

tion. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1; Terminiello v. Chi

cago, 337 U.S. 1; Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th

Circuit, 1947), cert, denied 332 U.S. 851.

Moreover, if free speech under these circumstances is

to be curtailed, the least one has a right to expect is rea

sonable notice in the ordinance under which convictions

are obtained, to that effect. Here, absent a statutory pro

vision that the person giving the “warning” have authority

to do so, and that he be required to communicate that

authority to the person asked to leave, petitioners were

convicted on records barren of evidence that such authori

tative notice was given. In effect they have been convicted

of crime for refusing to cease their protests at the request

of persons, who for all the records show, were strangers

34

at the time. The stifling effect of such a rule on free speech

is obvious; under the Fourteenth Amendment, therefore,

these convictions are doubly defective in curtailing First

Amendment rights. See Wiemcm v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 ;

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147.

W herefore, fo r the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

subm itted tha t the petition for w rit of certio rari should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

A rthur D. Shores

1527 Fifth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

P eter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

Oscar W. A dams, J r.

J. R ichmond P earson

Leroy D. Clark

Michael Meltsner

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

At a regular, adjourned, or special session of

the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama . . .

Judgment Entry in Gober Case

T he State

City oe B irmingham

—vs.—

J ames Gober

Appealed from Recorder’s Court

(Trespass After Warning)

H onorable Geo. L ewis Bailes, Judge Presiding

This the 10th day of October, 1960, came Wm. C. Walker,

who prosecutes for the City of Birmingham., and also came

the defendant in his own proper person and by attorney,

and the City of Birmingham files written Complaint in

this cause, and the defendant being duly arraigned upon

said Complaint for this plea thereto says that he is not

guilty; and defendant files motion to strike, and said mo

tion being considered by the Court, it is ordered and

adjudged by the Court that said motion be and the same

is hereby overruled, to which action of the Court in over

ruling said motion the defendant hereby duly and legally

excepts; and the defendant files demurrers, and said

demurrers being considered by the Court, it is ordered

and adjudged by the Court that said demurrers be and

the same are hereby overruled, to which action of the

Court in overruling said demurrers the defendant hereby

duly and legally excepts; and the defendant files motion

to exclude the evidence, and said motion being considered

2a

by the Court, it is ordered and adjudged by the Court

that said motion be and the same is hereby overruled, to

which action of the Court in overruling said motion, the

defendant hereby duly and legally excepts; and on this

the 11th day of October, 1960, the Court finds the defen

dant guilty as charged in the Complaint and thereupon

assessed a fine of One Hundred ($100.00) dollars and

costs against said defendant. It is therefore considered

by the Court, and it is the judgment of the Court that

said defendant is guilty as charged in said Complaint,

and that he pay a fine of One Hundred ($100.00) dollars