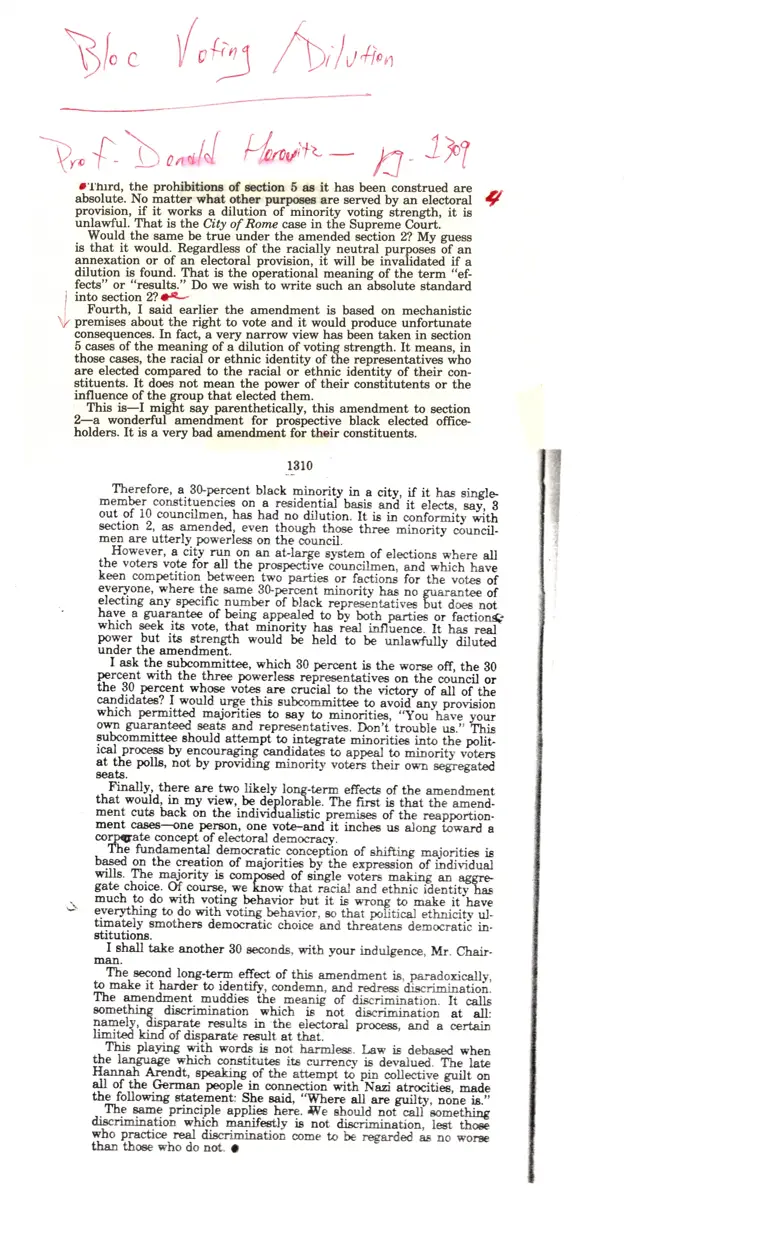

Statements by Professor Donald Horowitz RE: Bloc Voting/Dilution

Annotated Secondary Research

February 12, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Statements by Professor Donald Horowitz RE: Bloc Voting/Dilution, 1982. dfd4e696-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e4ab82c6-b58b-4f47-a841-f3e5a4bbc4c6/statements-by-professor-donald-horowitz-re-bloc-votingdilution. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

\

./ t

\' ,'y /\ ts!4iop1hc

,^u/J

-4-F4'>*--

l*il*oi*.- - n ih1

t

t

.:r

?,fb

t'l'trrrd, the prohibitiolrs of rstion 5 aa it has been construed are

absolute. No matter what other purpc€s are serrred by an electoral 7

prgvislon, if it works a dilution of minority voting strength, it is

unlawful. That is the City of Rome case in the Supreme Court.

Would the same be true irnder the amended section 2? My guess

is that it would. Regardless of the racially neutral purpose! of an

annexation or of an electoral provision, ii will be invalidated if a

dilution is found. !!at is the operationil meaning of the term "ef-

fects" or "results." Do we wistr- to write such an ibsolute standard

I into section n *-

i Fourth, I said earlier the amendment is based on mechanistic

\jz premises about the right to vote and it would produce unfortunate

consequences. In fact, a very narrolv view has been taken in section

5 cases of the meaning of a dilution of voting strength. It means, in

those-cases, the racial or ethnic identity of t-he repiesentatives who

are elected compared to the racial or -ethnic identity of their con-

stituents. It does not mean the power of their constitutents or the

influence of the group that elected them.

- This is-I might say parenthetically, this amendment to section2-a wonderful amendment for prospective black elected ofiice.

holders. It is a very bad amend"'ent foi their constituents.

_1310

Therefore, a BGpercent black 4inoFly-in.a city, if it has singlemember constituencies on a residentiat ursG a"'ti iI "t*t". ;;.

g

out of 10 councilme-n,_has had no dilution- it is-i" "i"rir-ify-#t[section 2, as smended, even f.frough ttroee three-minorily d"iiiii-men are utterly powerleas on the council.

.. However, a 6iqy rc! g', "" #tarBe syitem of erections where allthe voters vote f6r- all the proepective 6ounahd;;d ;*il h"*keen competition -between

-two'parties

oiiacti,oG r"itne

"dt"iibieveryone, where the same- 30-peicent minority has no guarantee oielecting any specific number bf black

"ep"er6oGuves

tut does;;

hgv.e_ a gu-arantee of being appealed to 5y both parties or factioni.which aeek its vote, tt'at minbrity has ;at irft[";. I; ti|f;tpower but its slrength would hi held to be unG*tuliy-dil;t"d

under the nmendmenl.

I ask the subcopmittee, which B0 percent is the worBe off, the B0

g9rc91t with the -three lrcwerless relreaentatives on the council o"the flQ perceat wbqse votee are cm6iat to ttre

"i"t""y-"r "lt o?-ti;

candidatea? I would yrg.g.th+ subcommitt€€ to a"oia"a"V p"o"isio;

which permitted majoiities to eay to minoriti;;-;y;"$ne vou"own guaranteed seats and representatives. Don'L trouble us.,, ttrG

subcommittee ehould attpmpt to-ptqrate minodtiea i"t th" 6iit,gl.plqggf by encouraging-"""+d"6 to rpp""t t";Gohir-v6L;

at the polls, not by providing minority vote* their own segregat€d

seats.

.. Finallyr-tlere ane two likely long-term effects of the amsn.rmgaf

that would, in_my view, be deplorable. The first is that the nmend-

ment cuts back on the iafividuaristic-prerises of thJ reapp""tfi-

ment cases-one pe-rgotr, one vote-and-it inchee us along fi*ara acolpCqte concept of electoral democ.racy.

fire fundamental democratic concepiion of shifting maioritiee ie

based on the creation of majorities uy trre exprosrri oflh-di;&"I

wills. the rnargrity is comp6eed of siigle votirs ma[iig an as,qr*gate-choicg. Of gor"rq,wg lnow that ricial and ethnicid*iiflrr".. much to do with v.oting Fhg"ipr but it iB xr,ong to ;"k;lt"h;;r-\ fl:lt$ q to.$o wilh

"-oting

beG"irrt;Th"r-p"fiti""t-*ir"ii,ity

"f:tipately smothers democratic choice and thr&tens democratia in-

stitutiong.

I shall take another 30 seconds, with your indulgence, Mr. chair-

malr.

The eecond long-term effect of this emsldmgat is. paradoxicallv.

to make it hardei to identify, @ndemr', and rediees'di"" i-iiltid:lls nmsndment muddies [Le meanig of-aisc-"imi"atro"Jt-cax;

something diecrimination which is -not discriminaiion at alt,

Iaryely,, results in the electoral pro@Ba, and a certainlimiffi kind of dieparate result at that.

- T\ir piaying yrih words is not barmless. Law is debased when

f}e langu^age w-hich constitutes its currency is devalued. The lateflenna[ Arendt, speaking.of the attempt !q pin collective guilt onall of the c,erman-people- in coq4eciiqD witn-Nari-it"ociti;l;de

thg.,following slate.qenl: S_be said, .,Wherr all arc g"ilry;;;" i".;

,.'Ih9 Tag prirgrple app{gs !ere. fle should noicetisopsthing

discrimination which manifestly is not discrimination, teet thd

who practice- real discriminatioi come to b" ".c"rd"dt oo wor*

than thae who do not. O