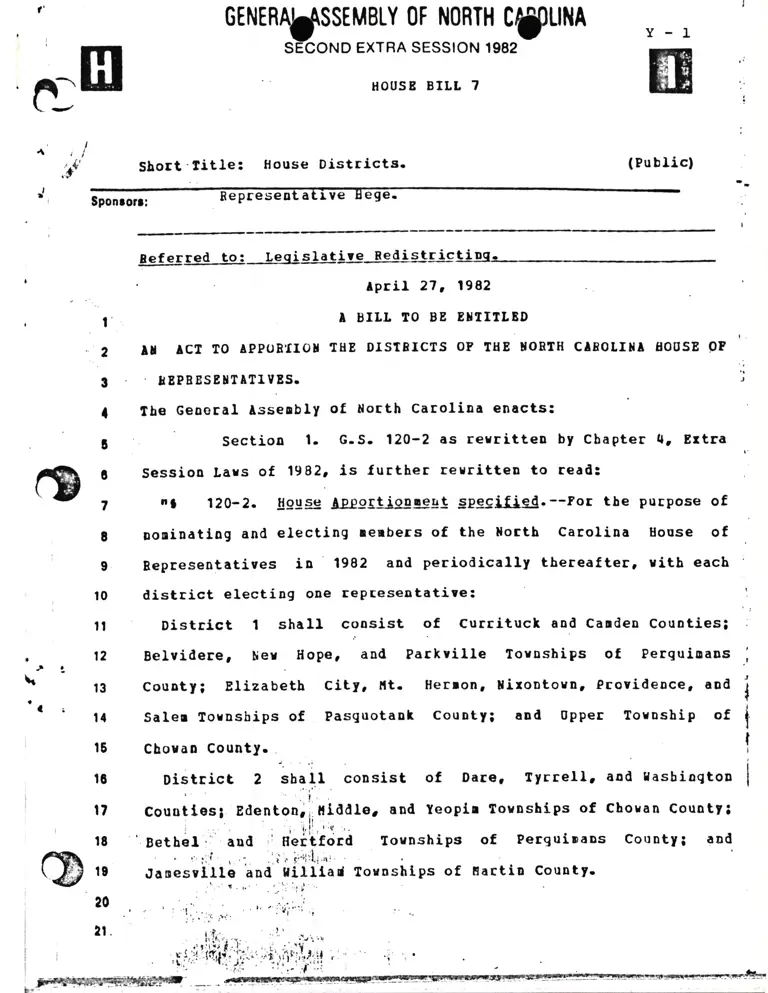

General Assembly of North Carolina House Bill 7 - House Districts

Unannotated Secondary Research

April 27, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. General Assembly of North Carolina House Bill 7 - House Districts, 1982. 622096a0-d392-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e4ba0e1e-79f8-46ed-878a-8e55754f8b22/general-assembly-of-north-carolina-house-bill-7-house-districts. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J,

f!

I

.:t(

GENERA5\SSEMBLY OF NORTH CryUilA

SECOND EXTRA SESSION T982

HOUSB BILI 7

Sbort'title: House Districts.

Y-l

(Publicl

Sponrorr: Eepreseotatrve Eege.

I

i

:

.t

t

I

t

t

a

,l

\

a i;

t

'2

t

I

t

c

7

t

9

t0

It

l2

l3

tf

l6

t6

t7

r8

t9

2o

f,eferred to: Leoislative Redistrictioq.

lprll 27, t982

I tsILL TO BE EUTIILBD

II ACT TO APPOBIIOU IHE DISTEICTS OP TUB UOBTN CINOTITIA SOUSE OP

. TEPB 8SE UTATI V8S.

fbe Geaoral Asseobly of North Caroliaa enacts:

Sectioo l. G.S. 120-2 as rerritteu by Cbapter ll, Ertra

Sessioo Lars of 1982. I's further rerritteo to readl:

nt 120-2. lggse Appggtign5g! Spggifisg.--PoE tbe puEpose of

ooniuatlog and electing rerbers of the Horth Caroliua House of

Bepresentatiyes in 1982 aod periodically thereafter, ritb each

dlistrict electiug ole rePreseatative:

DistEict 1 shall coosist of Curritucl antt Cardeu Couoties3

Belvidere, lier. Hopel aud Parkrille foruships of Perquioaus

Couoty; Elizabeth City, llt. Herron, UirontouD, Provideoce, aocl

Salel foruships of Pasguotaok Couoty3 auil Opper foroship of

Cboraa CountY. , ..i

District 2 sU1,|f . coDsist of Oar€, Tyrrell, aacl Iasbiogtou

.l

Couotles3 Edentonr,j f ltttller aDal Ieopll f ornships of Choran Couott 3

' :. i.l: '

,( ,,

Eetbel . auil :r R'ei['ford fornships of Perguiraos CountyS tDd

r' ;;I,.',, .'i, 1t-";1'

dlaoesyLlle

'antl filltaC toroshLps of Eartla County.

b.

ffinmm $6ffii8lYffi ilmfl

District 3 shall

Griffia, Beargrass,

, iartio Couoty.

, District tf shall coosist o[ Pallico Couot;; aad Ioroships l, 2,

,l

!*' 3, 8, antl ,9 of Craveu County.

District 5 shall coasist of Joaes coontl: tornships 5.6, aad 7

of CEaven Couoty; and Bichlands fornship of ooslou County.

District 6 sball, consist of Carteret County; aDd ttills and

Itortoo Precincts, Ihite Oak Torosblp, ooslor County.

District 7 shall corsist of ]lortheast Precinct, Ihite oak

tornship; Sransboro tornsbip; Crossroad Preciact, Jacksourille

Tornship; aod Stusp Sourd foruship, Ouslor County.

District I shall coosist of Jaclsonrille, Neu Biyer, East

dorthd, Iest tlortbd, tsalfroool TaE Lantling, antl lngola Precincts,

Jacksonville tounsbip, Ooslor County.

District 9 shaII consist of Holly, Topsail, Uoioa, BuEgau,

Rocly Point, aud Longcreel Tocnships, Pender County3 Precinct l,

Cape Pear tornship, Ner Hanover Couaty; and f,orthcest, Touncreek,

SnithviIJ.e, aoti Lockuoorls Folly Iornships, Brunsuick County.

District 10 shal.L consist of Preciucts t, 21 3, lt, 61 7r 9,10,

I l. 13, aud 26 of tlilaiagtoo Tornship3 Precinct 32 of ttasooboro .

Tornship; Preciucts 1. 2. antl 3 of Eetleral Point forusbipS and

Precincts 2 Fnd 3 of Cape Pear tornship, Neu Banover Couoty.

District 1l sball coosist of Preciocts t, 2.3, {r 5, 61 7, aod

frigbtbh Preciucts, HarDett Tounsbip; Precincts 5; 8, 72, and 10,

filringtoo Torushlp; and Preciocts 7t 2. .1, and 5, iasonboro

founsbip, ller Hanovec Couoty.

sstrcrutD stEssolsllw

1

2

,

L

,

6

7

6

I

10

LI

L2

1'

11.

t5

16

17

18

19

20

2t

22

?,

?\

25

?6

27

?8

c-basist

Crossroads,

of Hyde and Beaufort

and Pop1ar Poiot

Counti,es: antl

fornsbips of

' o,'

1

-/

io

it

a

)

2i

I

:

I

i

It.r-

t,

Bouse tsilt 7

(o

J'

SECOT\If EXTRA SESSION 1982

2

,

. lr'

.1 District l2.SbalI consist of Bug Bill, Cerro Gorilo, Chadbourn,

Fair Dluff, Lees, South lilliars, taturs, Ielch Creek, testbqj)

Prong, IhitevilJ,e, and filliars tovnships' Colulbus County; and

Shallottc aod taccdDdu Torastrips, Eruosricl, Couuty.

District 13 shall consist of Bladen County: Canetuck, Casrell,

Grady, and Coluobia foynships, Pender County; Raoson, Bolton,

laccalat, and Bogue Tornsbips, Coluubus Couoty; and Franklia

ar,5

6

7

E

9

10

11

12

1'

Ilr

., L5

I6

I?

1E

19

20

2L

22

t2)

2L

25

26

27

20

Iorasbip, SanPson Couatr.

District 14 shall consist of all

Erauklio Tounstrip.

DistEict 15 . shall coosist of uuplin Couoty antl Trent, Piuk

Hill, aud tloseley HalI Tornships, Lenoir County.

District l6 shall consist of Conteotaea, Saad HitI, VaDce,

f,instoa, Ueuse, Ealling CreeLr Southvestr Institute, aDd

,-l

tootlingtoo Tornships, Lenoir County. t,

District 17 shall consist of Xahuota, Indian Spriuqs,

Pikeville, Brogden, Great Suarp, Buck Sranp, Porkr and Grautbal

Tornsblps, antl Stoay Creek founsbip ercePt Goldsboro City

Precincts, llaYae CountY.

District l8 stra 11 consist

f ovnsbi ps, aud Goltlsboro citY

of Salpson Couuty excePt

of Goldsboro, Ber Hope, and Saulston

Precinct, StoDy Creek TornshiP,

Couaty antl lrth ur, A ytlen,

Creek, and Ilinterville

Belvoir, Grioeslaod,

a

lr-

a

( Iayne CountY.

District 19 shaII consist of Greeae

!aItrland, Parnville, Griftoa, srift

louoships, Pitt CouotY.

District 20 shall cousist of Greenville,

Chicodr and Pactolus IovnshiPs, Pitt County.

I

l"-

L

Bouse tsi:

o

ENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH

I

+t

' \./

,

.L

,

'6

7

I

I

10

u

12

I]

It

r6

I?

18

t9

20

2t.

22

2)

Alt

2,

26

SECOND E A SESSION 1982

District 21 sball Vonsist of Bertie Cout ,: Goose Uest,

Itartia Couoty;

Couuty; carolioa

and Soseneath

Hariltoo, Rooerson.vllle, and tilliats 1ovoshlps,

darrellsville aad St. Johns foroships, Hertford

, and BetheI Tornslri ps, pttt Couoty: and palryra

,t* louoshipsr'. tsalifax Couoty.

District 22 shall cousist of Gates County; Ahoskie, lraDers

recl, tturfreesboro, aod rintoo rornships, Hertford county;

Jaclson, Kirby, ocoueechee, pleasant flill, Eicb s{uare, goaDote,

seaboard, aod ticcacooee Toraships, Hortharptoo couDty: aad

Ueuland Tornship, Pasguotanl CouatT.

Disttict 23 sball consist of CoooconnaEa, Entield, Faucett,

Halifar, Roaoole Bapids, Scotlaod Necte antl teldoo Tornships,

Halifar couDtyl aod Gastou roroship, Iorthalpton county.

oiitrict 2{ sbalt consist of Saody Creek anrl Henderson

toraships, vaoce couoty; Judkins, Iutbush, RireE, Boaaole, sandy

creel, sirpound, SDith Creek, and Iarrenton Tornships, Iarreg

couutl; Brinkleyvllle, f,ittleton, aod ButteErood Tornsbips,

Ilalif ar Couoty 3 aoil Grif f lns Touuship, f,ash Couaty.

District 25 shall consist of Granville County; ilaDgun Tounship,

Durbar county; Nevligbt rounsbip, rake county: aod Tornsvirle,

Daboey, latklas, llilllansboro, fiittrelll and tidilleburg-trutbush

Toraships, Vaoce County.

District 26 sbal1 consist of Tcirnships 6, ', . 8. and g. Franklio

Couotl; lishiog Creelr Sork, aod Shocco Toynships, Iarrea Couotri

oldfield dud faylor Tornshlps, llilsoo County3 Upper Fishiog Creek

tornshlp, Bdgeconbe couotJ; and castalia, lraoniugs, .Iacksoo,

Ferrellsr Bailey, DrI tells, f,orth tbitahers, Red Oak, Iasbville,

(r

' r)

t,,

--,.-.i,:'l

{

?'l

\'

I

:-

t.-

House Bill 7

.i

I

o'

,

r., ,ltkrs

6

?

I

9

10

tt

12

1'

t!

li"\

lBrs

r5

17

18

,1'

20

.'21

.22

2'

aL

zS

26

d"\-z 28

GENEBAL ASSEIIBLY ()I NORI LINA SE EXTRA SESSION 1982

Oak Level, and Coopers fouoships, and South lbitaters Toraship

ercept Hocky ttouDt City Precioct, llash County.

District 27 shall coasist of Bocly llouut Clty Preciuct,

fornship 12, Edgecorbe County; Stooy Creel aod Eocky tlouot

tounshlps, and Bochy llount City Precinct, South Ibitakers

forosbip, t{ash CouDtI.

District 28 shall consist of founships t, 2.3, 0, 5, 7r 8, 9,

10, 11, 12, 13, aud 10, Edgecolbe CouDtI/; Gardnerr foisoot, aorl

Saratoga fornships, Iilson County; antl Fountain lornship, Pitt

County.

oiitrict 29 shall consist of tilson, Black creek, CrossEoads,

Springh:.11, aod Staatoos Torusbips, rilson Couoty.

District 30 sirall consist of Touoships 1r 2.3, rar 5, aotl

Pranklirr Couuty; aad tlilders, Ot Neals, se1ra, Claytonl ticro,

Iilson ttills Touuships, Johnston Couaty. t

District 3l shall consist of Groee Iornship, llarrett Couott3

aod Beulab, Pioe LeYel, Boon Hill, Beltonsville, Slithfieltl,

BaDneE, .Cleveland, Elevatioa, Ingrars, lleatlor, and Pleasaot Gaore

f ornships, Johtrs ton CountY.

Distrrct 32 shall coasist of caEL tleredith, rbite oak,

3uckbor1, Suift Cceeh and Holly Springs lornships of lal,e County.

Distrrct 33 shaIl consist of Paather Branch, tidclle Creel, St.

ttaryrs, Baleigh, and St. ltattheurs Totnships oi Iake Countl.

Distrrct 3lt snaII consist of llarks Creek, Little 8ivec, lale

lorestl tleuse (oiuus Raleigbl I Bartons Creek, Leesville, llouse

Creek autl Cedar Fork Tovoships of lJale County.

I

t0,

aod

I

I

House Bt-' '

tTlTNT ASSEMBLY OF NORTH

1

2

)

L

5

6

7

E

9

10

u

t?

13

1L

t5

16

I7

18

19

20

2t

2?

2)

zlt

z5

z6

27

2E

SECOND SESSION 1982

District 35 sball ist of Precincts t9, lilll. 20,. 22. 25,. 26,.

28r 3{, 35, 13, ta.l 21r 2t, aotl 27 of take County.

' District 35 shall consist of Preciocts 37,36, 38, 39, 42r 30,

i 15, 16, 17, 18, Uouse Creel-l and House Creek-2 of IaLe Couoty.

:r Distrlct'. 37 shall consist of Precincts 1, 2. 3, 0, ll, 5, 6, 7.

10, E, g. 72, 29r 31, 32, 2{, {1, aod 33 of IaIe couDty.

District 38 shall coosist of all touosbips of Lee County; of

Gulf , Cape Fear, tt au Biyer and Oaklantl f ornships of Chat hal

Couuty; aud of Buckhorn aatl Upper tittle Eiver founships of

Harnett Couuty.

District 39 shall cousist of Anclerson Creel, lverasboEo,

Barbecuer tslacL 8iver, Duke, Hectors Creek, Johnsooville,

tilfingtoo, NeiIIs Creel aod Sterart Creet tornships of Haroett

Couoty.

Distrlct ll0 shall consist of Precincts 11 31 5.9, t3, 16, t?

and 19 of Cross Creek Toroship, testol€Er BeaveE Lake, and

IlorgaDton Road I Precincts of Curberland County.

District 01 sball consist of CEoss Creek Precinct 22 anil Beaver

Dat, Black River, Liadeo, Loag HilI, Cedar Creel, Judsoo,

Stedraa, Vaocter, U ade, Eastover, Pearces ilill 3, Hope ltills 1 and

2, Alderoao and Shervoocl Preciacts of Curberland County.

Distrlct 42 sLall coosist of Cross Creek Prcciucts ll, 6, 7. 8,

10, ll, 12, 14, 15, 18, 20 aod 21, Pearces tiII 1, 2 aud ll,

lootclalr, and Cuoberlaud 2 Preclncts of Curberland County.

Distrlct q3 sba[l coosist of llaocbester, Spring Lake, Cottonade

antl College Lakes Preciucts of Corberlaad Couoty.

District tttl sha 11 consist of Cunberland t, Brentvood, Seventy-

IIouse Bill 7

c

I

i

o

.a

a\,

I

rl.

-, - E,',:-- ---. -irO:o^*.1---

GENERAL ASSEMBLY ()F NORT

1

2

t

SEC EXTRA SESSION 1982

C

6

7

E

9

10

u

12

13

Ur

,' \'

VL5

16

I?

18

19

20

'2t

,?2

2)

Zlt

?5

?6

U.,,\- zB

LI

lirst t, 2 aod 3, and torganton Road 2 Preciucts of Culberland

District 45 shall cousist of Lurbertoo, BacL SralP, Britts,

East Horellsyille, Pairront, tlarietta, Orrul, Sryraa, SterliaqS,

Iest itorel-Lsville, Iishart and Baft Suarp totnsbips of Sobesoo

Couotl.

District tl6 shaII consist of llforilsville, Burnt Suarp, lartou,

Parktoa, Peobroke, Philatlelpbus, Red Springs, Rennert, Borlaotl,

Satldletree, St. Pauls, Sliths, Union, Tholpboo atrtl Gatltly

forosbips of Robbson CountY.

District ttl shall cousist of all toraships of Hote County; of

Lunber tsrittge a.ocl Shannoo Iornships of Robesoo County3 aud of

Laurel HilI, Spriug llill and Stevartsville Tornships of Scotlancl

Couoty.

District tl8 shall consist of BeaYerdar, Blacl Jack, tlarks

Creek, Eoclinghau, Steeles and Uolf Pit fornsbips of Bicblond

couoty; aod rilliarsoDs Tornship of scotlaod couDtI.

District q9 sball consist of LilesYille, lnsonville, fadesboEol

Cirlledge autl 6orren foraships of lnson CountIS tlineral Springs

Tornsbip of Richnontl couDty3. aatl all tornships of tlontgorerT

County.

District 50 shall cousist of all tovnships of lloore Couoty.

District 51 shall consist of Back Creek, Cetlar Grovel Concord,

Level Cross, tler llope, Uer tlarket, Providence, Bantlleoau,

faberuacle, Trinity anil Union Tornships of Bandolph County.

Distrlct 52 shall coosist of lsheboEo, Colunbia, Libecty,

tianklioville, Coleriilge, Brorer, Grant, Bichlantl aud Pleasant

a

a

t,

I

I

!

I

t

r*

House BilI 7

UTNTHAL AUUTMULY trr il()RIH SECOND RA SESSION 1982

1 Grove touaships of dolph Couutri and Bear eek anil rlbriqht

founsbips of Cnathat Couoty.

District 53 shall coosist of tittle Bi.rer, ?no,

tlirlsborouglr, chcels aud Bioghar Toroslrips of orauge

Iilliar, .ltey Hope, Baldrin, Center, Hadleyr Sickory

lattbers toraships of Chathal County.

t ,r

srq

Ceclar G Eore,

Couoty; and

louotaiu aod

a:

.16

7

I

9

10

u

12

13

1L

t5

16

17

18

19

20

2t

22

2)

zlt

2,

?6

2?

?8

District 5ll shall coosist of chapel Hilt Tornship of oraoge

Couotl.

District 55 sha1l consist

Durbauf, Lebanon, Oak Grore aad

Couaty.

of Carr, Durhat (niaus City of

friaogle Tovnsbips of Durhau

8, 9, 10, I l, 12,

Durbaa Toroship

13,

of

District 56 shall consist of preciocts

I {1, 15, 16, 17 , 18 , l g, 20, 22, lt 1 aod rl2 of

Durbal Courrty.

District 57 sharl ccnsist of precincts 1. 2, 3, rl, 5, 6, 7 0 21,

23r 24r 361 39 and q0 of Durhar rovnsbip of Durhao county.

District 58 shall consist of all tovnsbl.ps in Casvell Couoty

aud all tornships in persoa Couaty.

District 59 sbrll consist of tluntsville, rillialsburg,

Leaksrirle, llentrortb, price aud ltayo rornships of Bockiogbal

Couaty.

District 60 sball coosist of oak Bidge, Bruce, center Grove aad

llooro€ rovaships of Guilforrl Couuty; and Sitpsonville, Beidsrille

and der Bethel fornsbips of goctinghat Countl-

District 61 shall coosist of tashingtoo, gock creek, aLA-cBvL,

Jeffcrson, Gf,eeoe, Chaz, Fentress, Surner aod iladison toroships3

Preciuct 2q of Greensboro rornship of Guilford county.

House BilI 7

C

t

a

I

I

(?

.i.i.

.:,

.

- !'r'i

t 'r t'-l

. rr.-r..,'-'!.:tI

I

i' rl

9

(D,

)

.d

,.(t5

6

7

I

9

10

u

L2

13

D}

1.6

1?

18

19

20

'21

.22

2'

2L

?5

26

(

I

,s:;

District 62 sha.l.l coosist of Prec.iocts 1. 2, 3, ll, 5, 6. 7. 19,

29, 3O and 33 of Greensboro tornshiP of Guilford CouDty.

District 63 shall consist of Precincts 9. 8. 25, 15, 18, 26,

21,- 19, 22 antl 17 of Greensboro Tornship of Guilford County-

District 6tl shall coosist of Greeasboro Preciacts ll, 12, 13,

ltl, 28, 10, 16, .31, 20, 21, 32 aud 22 of Guilford Couoty.

District 65 shar.l coosist of Deep River aod SrieodsLip

Tornships, Greensboro Precioct 3{, and Higb Point Preciucts 20,

161 8, 9. 1, 2, 3t ll, 10, 15 and tq of Guilforcl Couoty.

District 66 shall coosist of Janestoru Tornship aocl lliqh Poiut

Precincts 5, 6, 7 , t l, 72, 13, 1l , lt), 19 and 2l of Guilf ord

Couoty.

District 6? shall consist of Grahar and Burlington Toruships iu

Alaoance County.

District 68 shaII coosist of Patterson, Cobb, Boo8estolD,

llorton, Faucette, AIbright, NevIin, ThorPsoD, !l€IYille, Pleasant,

aod Har Eiver'Tounships of Alanance County.

District 69 sball consist of Stokes County, ltaclison Tornship of

Bockinghal Couuty and Pilot, llestfield aDd South restfield

tornships of SurrY CountY.

District 70 slrall consist of Pocsyth County Precincts 2O-2. 20-

3, 2O-q . 20-5, 20-6, 30- 1, 30-2, 30-3, 30-0, 30-5, 30-6, tl0-1,

tt}-z, 40-3, tl0-tl, 00-5 aad q0-6-

District ?1 shall consist of Forsytb Couuty Precincts 50-1, 50-

2. 50-3, 50-q, 50-5, 50-6, 50- t, 60'2, 60-3, 60-tl, 60-5, 60-6,

60-7 t 7O-2. ?0-3, ?0-ll, 70-5 and 70-6.

District 72 shall consist of Forsyth Couoty Precincts 80-1, 80-

I

I

I

I

{

't

EXTRA SESSION

Housa B

TEI\IERAL ASSEMBLY OF I{ORIH

1

2

,

It

,.

6

7

I

9

10

u

t2

13

1b

t5

16

1?

18

L9

20

2t

22

2'

?1.

25

?6

2?

28

It

SECOND RA SESSION 1982

2, 80-3, 80-4, 80-5,

90-5, 90-6. and 20.1.

6, 80-8, 70-1, 7o-7, 9 I, 90-2, 90-3,

District 73 shall coosist of fbb Creel Preciocts I and 2.

, Belers Crcel, Uroad itay Preciacts t and 2. l(oroerscitle Preciacts

1 apil 2r tttid'lle Fork Preciacts 2 and 3, Saler Chapel Precincts 1

aoil 2, and Soutb Fork Preciacts l, 2.3. aad ll of Forsyth Couoty.

District 7.t sh;.Il consist of Betbaoia l, 2. aod 3,

Clenroosville 1 aud 2. Lerisville 1 and 20 old Bichlootl, Old Tora

2, 3, aacl q. Uic una 1 aotl 2 aud Uinston-6a1et 90-7 Precincts of

Forsyth CouDtI.

District 75 shall coosist of Lerington, lbbots Creek, 6iclrayr'

Arcadia, antl llaoptou Toloships of David.son Couaty-

District 76 shall consist of Thorasville, Conrad Hill, Eoooos,

Jacksoo HiII, Alleghaoy, Silrer nill, and Bealing Sprirgs

lounsbips of Davidsoo CouatY.

District 77 sbaJ.I coosist of Eeedy Creek, fyro, B9ooe, Cottoo

Groye, aud Iadkio College Tornsbips of Daviilsou Couoty, DaYie

Couoty, East Bend and Porbush tovnships of fadkin Couuty, and

Eagle flilIs and Turnarsburg Tornships of Iredell Couuty.

District ?8 sbaLl consist of Salisbury, Locke, Ffanklio, Uuity,

Scotcb Irish, Clevelaad, and Steele Iounships of Rouan Couoty.

District ?9 shall coosist of Providence, Litaker, Goltl fiill,

Cbina Grove, Atrell, and !t. UIla fovnsbips of Bovan Couotl.

District 80 shaIl coosist of Stanly Couoty.

District 8l sball coDsist of Gold Hillr Bilertornr ller Gilead,

fianDapolis, Odell, and Poplar Teot lornships of Cabarrus Couaty,

and lorgan IovnsbiP of Sovau County.

t

.:)

o

10 tsouse BiII 7

r"'

1

2

,

It'

5

6

?

E

9

10

11

12

u

t!

a

.l*

I

GENEBAL ASSEMBLY OT NON CABOLINA SE D EXTRA SESSION 1982

District 82 -hall coosist of ceatiir cabacrus, concord,

didlaud, Harrisburg, ceorgevilre, antl it. pleasaut rounsbips of

cabarrus county, aad Goose creek tovoship of uoioa couotr-

District 83 shall consist of lter Saler, ;arsbvitle, Laoes

creeli, tlonroe, and Buf ord Tornships of 0oion courrty, aDd

-

Lanesboro, Ihite Storer nDd Burnsrille Tovnships of las.rD Couoty.

District 84 shall coosist of ltattheus, 95, t'int Hill I aad 21

iorDiDg Star and ProYitlence Precincts of tteclleaburg Corroty, and

Sanily 8oad, Jackson, and Yance foynships of Union Count.r.

District 85 sball cotrsist of Crab orchard' 1 and 2, CIrriE Creek,

aud Preciucts 83, 6, 80, 29, ,t. 33, rl5, 61,- 5, aod J of

llecklenburg County.

District B6 shaII consist ?f Precincts 1rl, 15,30, 2gr 42r 26,

60, ll3r 0ll,82, and ilarlard creek 2 Precincts of fiecklenburg

Count y.

District 87 shall consist of Par creek I aud 2, oakdell, Loog

creei l, Leurey, Davidson, cornelius, Huntersvirre, lallard creek

7, aod 81, 79, 80, and 53 Precincts of fieckleuburg Couaty aad

Preciocts 39 and tt0 of Gaston County.

District 88 shall consist of Loug creek 2 and pceciocts 16, 25,

01, 55, 56, 54,- 9, 27 , 13, 11, aod (0 of ttecklerrburg Couaty.

District 89 shall cousist of Precincts 12, 23, 24,. 22, 31, 39,

52, 1'1, aod 78 of llecklenburg County.

($,,

16

1?

18

19

?o

2t

??

2'

2\

2,

?6

2?

28

District 90 strait coDsist of Precincts

32, g, l, 18, 10, 20, 2l , 38, 46, 3rt, aorl

CouEtr.

17,. 2. 35, ?. 36, 66,

5l of ueclleuburg

i

Uouse BiII 7 1l

iI

GENtHAL AUUIMULI UI NUII IH UANULINA

2

,

L

5

6

7

8

I

10

u

12

1'

1L

15

16

17

18

19

20

2t

22

2)

?L

2'

r6

2?

2E

\Ja-\rty.M., Ln I nff \)L\)!)l\rll l9(16

1 Di'trict gt sball !$ist ot Preciucts 59, 41, 71, 72 , 70,

73r 86, 19, 67r 62...631 681 64, aod 65 of ttecllenbuEg CouDtt.

District gZ shall cooslst of Steel Creel t aod 2. Pioerille,

,Par Creel 3, Berryhill, tntl PreciDcts'15r 3?, ll9, 50, 59, 58, 14,

57, 76, aDd. 87 of tteclleBburg couoty.

DistEict 93 shall coosist of Coiltlle Creel, Pallstora, Dttiilsoo,

Coacord, aad Sbiloh touoshlps, Iredell Couoty: aud Sharpes,

tillers, raylorsville, Little Biver, and Ellendale TornsbiPs,

llerander CountY.

DistEict 90 sball cousist of Graltneys qDd Sugar Loaf

toroships, Alerautier CouDty3 Chalbersburg, Cool Sprisg, Uaioo

GroYe, OIi,n, BethtoI, Statesville, Xer [oPe, SharpesbUEgr aDd

Barrioger Tornships, Iredell Couoty.

District 95 shall coasist of Liberty, DeeP Creel, FaIl Creel,

Booaville, troobs, aDd BucI Shoal touoships, latlkio CouutyS Xeu

Castle, SoDers, An tioch, Lovelace, BEushy lountain, Eetltlies Biver

loraships, North Iiltesboro Tornsbip (ercept Uorth Ililkesboro

f6r0 Preclncts! and lillesboro fouoship (ercept Dorth llilkesboro

rodfr Itreelactal , r 11kes couotT.

District 95 shall , colslst of Shoalsl llount liry, Loog Hill,

Eldora, silonl, 6terarto Creehe Dobson, Bochford, tlarsb,

!raoklial SDdl btyao founsblPs, Surry Couuty.

Distridt 91 euall coDalst of llleghany couuty3 Trap 8i11r

Bduoi.tS, galritjt 0rdVe1 loct Creek, iulberry, Uoioo, loravian,

Strftitriiir l,eUts fOfhl Soouerr,Jobs Cabiu, Elk, aod Beaver CEeel

tOUnehtpBl ,t06 tho Iorn of tlortb lllllesboco, Uilhes County; aod

Elkin Tounship, Surry CountT.

Ci

,,y't

.a

.t

6

House BifI 7

ffi'Igffi$SrffiSffF$i'

l2

-a

r_'tL'

.l

(D:

, ,'t

l'5

6

?

E

9

10

u

L2

rt

ilr

TD,'

Bloriog Bocl, Blue

teat Carp, der

Iatauga County.

SE D EXTRA SESSION 1982

lshe County; aod gatd touotaio,

Brushy Pork, Cole Creel, Elf,

PorLe rod Stoay fork touostipsr

aidge, Boone,

8iver, Iorth

District 100 sball coosist

Kiags Creekr I,it tle niver,

tornsbips, Calflrell Count I.

District 101 shall consist

of Lorer Creet, Hudsoo, Leooir,

Iadkio Yalley, antl patterson

of Dysartsville Toruship, lcDouell

a j.

,l

16

17

10

19

20

?t

?2

2)

2b

?5

26

CouatlS and Sooky Creel, Drerel, [organtoo, Upper pork, Louer

creekr Quaker deador, and silver creek rornships, Burke couoty.

District 1OZ shall consist of llitteaberq Tornship, lleraader

Couaty; Lovelady autl North Catavba Torashlps, CaldreLl CouDty3

Icarrlr Lorer Fork, and Lovelady founships, Bucke Couuty; and

Bandyrs Tornship, Catarba countr.

District 103 shall consist of tturberry, Grober.Iohns River, and

tilsoo creek Tornships, calclcell county; upper creel, Lioville,

antl Jooas Bidge Tornships, Burke County; Braclett, Croohed Creek,

Gletvoodr tsi99ins, ^Iarionr tlontford Coye, Nebo, Nortb Coye, and

Olfl Fort Tornsbi ps, tlcDoyell Couoty; and Catp Creel, !toEqaD,

Chirney 8ock, GiIkey, Green BiIl, aod Logan Store Tornsbips,

Butherford Couoty.

Dlstrict l0lt shaII consist of Hickory Tornship, Catauba couaty.

DlstEict 105 sball consist of Calduell, Catarba, Cl.ioes, Jacobs

Porl, aatl Herton Tornshlps, Catarba Couaty-

GENERAL ASSEMELY t)F NOR

District 98 all coasist of

DiStrict 99 shall coosist of Avery, titchellr aod ialcey--

couuties3 and rataugnr Beayerdan, Laurel creet, and sharueehar

Iornships, Iatauga countl.

G::

---tt

Houso Bill 7 13

1"

1.--'GEr.lEnil

ASSEUSLY 0t NoRTH C{!qU5-

I

2

3

District 106 sball

Spriag, Butberfortltoo,

Butherford CouotY.

nsist

Sul pbur

of Polk CountIS

Springs, and

SECOND EX SESSION 1982

d Colfar, CooI

..

I

Unioo Toroships,

L r District 107 sh.rll cooslst of Duocaos Creek, Goldeu UclJey, aod

S

'!1' Hlgb Shoa is Ioroships, Butherfortl Couuty 3 antl 8iver, Boillag

6 Sprlagr PoIkriIIe, saacly Bun, caesar, BiPPrs, l(ings lount;rin, aod

Knob Creek tornships, CleYeland County'

Dlstrict 10S sball coosist of tarlick, Shelbyr ctlL

ShoaIs fornships, Cleuelaotl County; aotl North Erook and

Creek TounshiPs, Liocola CountY.

DistEict 109 sball consist of Precincts llr 6.8, 16,

30, 31, 32, 33 , 3ll , and )7 , Gastoo CouotY'

District 110 shall consist of Precincts 1. 2, 3' 5, 7,

11, 12, 13, lll, antl 29,. Gaston CouatY-

District 1ll shall coasist of Precincts 15, 17,.2Qr 21r 22r 23,

Ztl , 25, 26, 27 , 28 , lt 1, ancl 42, Gaston county'

District 112 sball consist of Preciocts 35, 36, aocl 38, i;astoo

couotl; catarba springs, lrouton, aDd Liocolotoo Torosbips,

Liocoln couoty; aud ilouatain cEeek roYuship, catarba county.

District 113 shall consist of Blue Ridge, Clear Creek, Crab

Croek, goopers Creetr, Green River, and Hendersonville Tornshipsl

Eendersou Countl.

District 11tl shall coasist of Precincts Bun-1, tsuu-2, Bua-3,

8uu-ll, BUO-5, 8uu-6, BUO-7, BuD-8, Bun-9, Bun-10, Bun-ll, Buo-171

Bun-20, Buu.30, EUn-31, aod Buu-51, Buncorbe Couoty.

Distrtct ,115 shall consist of Precincts 8un-12, Buu-13., Bun-t{,

'I

Buo-15, Buo-16, Uuo-t8r, Bun-19e 8uo-21, Bun-26' Bun-27' Buo-331

House Bi lI 7

t

'1

7

E

9

10

1I

t2

13

1L

t5

16

17

1E

19

20

2l

22

2t

zlt

2,

26

??

2E

Double

Borards

1 8, 19,

g. 10,

lll

t

.1

t@r'

lr*--

J'-

't,

t'

:,

c@,

*I

CEIITNT ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CABOLINA SECOND EXTRA SESSION 1982

,

It

5

6

7

I

9

10

lt

L2

13

1b

Buu-40, Buu-{t, Aun-lt3r Buncorbe Couuty; aod Btlueyville Torosbip,

Uenderson CouDtr.

Di.strict 116 sirall consist of rransylraaia countY; tliLls niver

f orlshi p. lleldersou CouIt I: Canada, Cashiers, tla obucg, a od Biver

fornsblps, Jackson CouDty3 and Preciucts Bun-3t1, 8un-35r aad Buo-

36, Buncolbe CountY.

District 117 sbaIl cousist of Precincts Buo-22, Bun-23, 8ua-24l.

Buo-25, 8un-28, Buu-29, Bun-32, Buo-3?, Bun-38, Buo-39' tsuo-q2'

irtrD-tt{, 8un-45, Burr-t16, BuD-{7, 8uu-t08, Bun-tl9e ?tt'l Bun-50,

Buncoobe CountY.

District llg shaLl consist of Beaverdar, Pigeon, East Pork,

Crabtree, Clycle, IayDesville, Cecil, aod IYY Hitl Tornsbips,

Hayrood Couuty; and Caney ?ork aud Cullouhee Torosbips, Jackson

County.

District I l9 shall cousist of llaclison, Svaio, and Grabar

Countiesi Ptnes Creek, IroD Duff, Citaloochee, Ihite 0ak, aofl

Jonatbaas Creek Tornships, Hayuood Couuty; and Barkers Creek'

Dillsboro, Greeos creek, gualla, scott creelr otttl sylva

fornshiPs, Jacksoo County'

District 120 shall consist of cherokee, clay, aud tacoo

Counties; and Savannah, llountaio, anil Iebster TovushiPs, Jackson

Couotlt. tr

I6

1?

1E

I9

20

21

22

2'

2L

25

26

lo

of

Sec. 2. The DaEes and boundaries of tounships specifietl

this sectiou aEc as they uere tegally defioed and in effect as

Januaryl,lgE0rnDdrecognizediothel9S0U.s.Census.

Precinct boundaries are as shovn otr tbe DaPs oD file

titb the state Boartl of Elections on Jauuary 1, 1982, iOqe;:

i

i

,!!

Houso Etll 7 15

GENENAL ASSIMBLY t}T IIORTH CAB

accordaoce rith G. S. 163

If aay

areas os the raP

Sec. 3.

I

1'

,

I

5il

6

7

E

I

10

11

12

1'

11.

L,

16

17

18

19

20

2t

22

2)

2L

'25

?6

27

2a

(b) -

clraoges in precl,nct

shall still reraiD io

this act is effective

SECOND E roN 1982

bountlaries are rade, tbe

the sare House District.

upor rititicatioa.

€)

.$

.-l'

I

a

L

.t

House BrlIt6