Loral Corporation v. McDonnell Douglas Corporation Opinion

Public Court Documents

July 29, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Loral Corporation v. McDonnell Douglas Corporation Opinion, 1977. a1c36797-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e58bfdb9-9d52-4737-8369-ae5d0bcaba8c/loral-corporation-v-mcdonnell-douglas-corporation-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

f * * ® r ® -

^ c ' u f b ; f

AUG

\9U

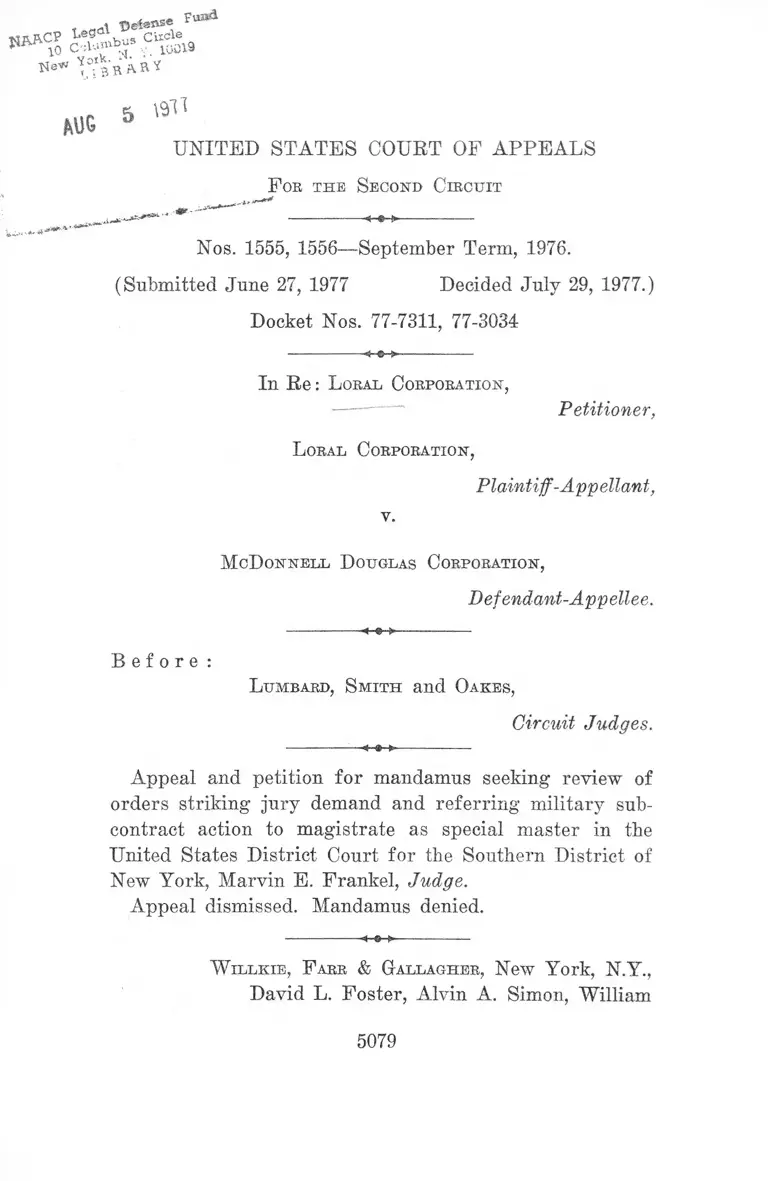

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe the S econd C ircuit

Nos. 1555, 1556— September Term, 1976.

(Submitted June 27, 1977 Decided July 29, 1977.)

Docket Nos. 77-7311, 77-3034

In R e : L oral C orporation,

Petitioner,

L oral C orporation,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

M cD onnell D ouglas C orporation,

Defendant-Appellee.

B e f o r e :

L umbakd, S m it h and O akes,

Circuit Judges.

Appeal and petition for mandamus seeking review of

orders striking jury demand and referring military sub

contract action to magistrate as special master in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

New York, Marvin E. Frankel, Judge.

Appeal dismissed. Mandamus denied.

W il l k ie , F arr & Gallagher, New York, N.Y.,

David L. Foster, Alvin A. Simon, William

G. Scarborough and Francis J. Menton, of

counsel, for Plaintiff-Appellant Loral Corp.

W h ite & Case, New York, N.Y., Thomas Mc-

Ganney and Todd B. Sollis, New York, N.Y.

and Bryan, Cave, McPheeters & McRoberts,

■St. Louis, Mo., George S. Heeker and Charlie

A. Weiss, St. Louis, Mo., of counsel, for De

fendant-Appellee McDonnell Douglas Corp.

B abbaba A llen B abcock, Assistant Attorney

General, Department of Justice, Washing

ton, D.C., Robert E. Kopp, David J. Ander

son and R. John Seibert, Attorneys, Dept,

of Justice, of counsel, for United States as

Amicus Curiae.

S m it h , Circuit Judge:

Loral Corporation, a subcontractor designing and pro

ducing classified equipment for the Air Force, in August

1973 sued the prime contractor, McDonnell Douglas Cor

poration, on the subcontract in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York. McDonnell

Douglas counterclaimed for alleged breaches by Loral.

After extensive discovery over a long period a pretrial

order was prepared under the supervision of a magistrate

and adopted by the court.

The court, Marvin E. Frankel, Judge, struck the demand

of Loral for a jury trial, found the case suitable for

reference to a magistrate in view of its complexity and

probable length of trial, the heavy demands on the court’s

time in the foreseeable future of criminal cases under the

Speedy Trial Act, and the necessity for protection of much

classified material which would be essential to trial of the

5080

issues on the complaint and counterclaims. The court or

dered the case referred generally to a magistrate as special

master for hearing and the preparation and submission

of proposed findings and conclusions.

Loral sought review of the orders by application for writ

of mandamus and later filed what it termed a “protective

appeal” which McDonnell moved to strike. The motion to

dismiss the appeal is granted. The order of reference is

not a final judgment or order and is not reviewable on

appeal. See United States Tour Operators Ass’n v. Trans

World Airlines, Inc., — F.2d —— , slip op. 3903, 3906

(2d Cir. May 27, 1977); EcJdes v. Furth, —— F.2d — —,

slip op. 4213, 4219 (2d Cir. June 16, 1977). See also

American Express Warehousing, Ltd. v. Transamerica In

surance Co., 380 F.2d 277, 280 (2d Cir. 1967).

We dismiss the appeal since it was taken from orders

not final and not presently appealable. The application

for an extraordinary writ is properly before us. LaBuy v.

Howes Leather Co., 352 U.S. 249, 254-55 (1957). We deny

on the merits the petition for mandamus or other extraor

dinary relief.

We have examined the material submitted to us suffi

ciently to determine that a large amount of material prop

erly classified confidential and secret must be submitted to

the trier of fact in the case. We are persuaded that this

circumstance is enough to make it inappropriate for jury

trial. United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1, 10 (1953). '

The Department of Defense has cleared, or can and will

clear, for access to the material the judge and magistrate

assigned to the case, the lawyers and any siipporting per

sonnel whose access to the material is necessary. The

United States as amicus curiae objects, however, to any

requirement for jury clearance in like manner. Id, at 7-8.

We are satisfied that jurors may not feasibly be handled

by such a process. Long delays through investigation of

5081

prospective jurors, the lack of the usual job-related in

ducements and training for long-term commitments to

secrecy by jurors picked from the general population and

the difficulty in monitoring long-term compliance on the

one hand, and the chilling effect of clearance investigations

on proper functioning of the jurors as triers of fact on the

other, support the court’s conclusion that jury trial is not a

practicable possibility. In any case, we note that both

parties, in the contracts which are the subject matter of the

litigation, have bound themselves to preserve the confiden

tiality of classified material.1 Under the circumstances

they have effectively waived the right to jury trial of

issues involving the contracts. We will not disturb the

order striking the claim for jury trial.

The determination of the propriety and necessity of a

general reference to a magistrate presents questions of

even greater difficulty. We are satisfied, however, that the

reference, even though without the consent of both parties,

was within the expanded powers of the court under the

Federal Magistrate’s Act of 1968, 28 U.S.C. §631 et seq.,

as amended,2 and that it was a proper determination under

those circumstances. Mere length and complexity of the

prospective trial and the great demands of the pending

1 Compare E.W. Bliss Co. v. United States, 248 U.S, 37, 46 (1918) ;

United States v. Marchetti, 466 F.2d 1309 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 3063 (1972).

2 90 Stat. 2729 (Oct. 21, 1976), 2 TJ.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News amended

§ 636(b) (2) of Title 28 to read as follows:

A judge may designate a magistrate to serve as a special master

pursuant to the applicable provisions of this title and the Federal

Buies of Civil Procedure for the United States district courts. A

judge may designate a magistrate to serve as a special master in

any civil case, upon consent of the parties, without regard to the

provisions of rule 53(b) of the Federal Buies of Civil Procedure

for the United States district courts.

The amended provision apparently is intended to allow reference with

the consent of the parties even where there is an uncomplicated ease and

no exceptional conditions.

5082

case load, particularly criminal, would not be enough under

the ruling of LaBuy v. Howes Leather Co., supra, to

justify such a reference. The length and complexity, of

course, are elements complicating the problem of the trier

in preserving the confidentiality of the classified material

and in this sense support the necessity of the reference.

There are additional elements involved here, moreover,

in the nature of the required evidence and the difficulty in

preserving its confidentiality.

In today’s version of what Winston Churchill termed the

Wizard War, the courts are faced with the problem of re

solving private civil disputes and at the same time pre

serving the confidentiality of developments by or for

governmental defense agencies. One alternative in the

most sensitive cases would be long-term postponement or

complete denial of the forum to the litigants. However,

Buie 53(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure pro

vides another alternative. The rule permits reference to

a master on a showing that some exceptional condition

requires it. Moreover, the Congress has provided pro

fessional, experienced officers in the magistrates available

to serve as special masters3 and encouraged the “district

3 See H.B. Bep. No. 94-1609 at 5 tl.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 6162,

6172 (1976):

Enactment of this new subsection 636(b)(2) and experience in

the use of magistrates as special masters, may serve to occasion a

reappraisal of the power of the court to appoint a special master,

i.e., the magistrate, to serve where one of the parties objects to the

reference. [See, LaBuy v. Bowes Leather Co. (1957), 352 U.S. 249.]

Indeed, the magistrate is not an attorney in private practice "ap

pointed on an ad hoe basis” and the magistrate is experienced in

judicial work.

The Senate report contains identical language. S. Eep. No. 94-625, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1976), at 10.

Both the Senate and the House Committees apparently invite a re

appraisal by the Supreme Court of the LaBuy rule where a magistrate

is available for appointment as special master even in the ordinary

LaBuy situation.

5083

courts to continue innovative experimentations in the use

of this judicial officer.” 4 S. Eep. No. 94-625, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1976), at 10. Courts of equity have the power and

duty to adapt measures to accommodate the needs of the

litigants with those of the nation, where possible.5 The

court here has properly utilized the tools provided in Rule

53(b) and the expanded Magistrate’s Act.

We recognize the constitutional problem posed by the

limitation of review of findings of a master under the rule

by the “clearly erroneous” standard. See Mathews v.

Weber, 423 U.S. 261, 269, 273 (1976). The ultimate respon

sibility, however, remains with the court. At least as

presently limited we perceive no deprivation of an article

III court or of due process.6

Further long-term delay in this case to await the avail

ability of a judge would compound the problems of pro

tecting the confidentiality of the classified material. There

already exists a dispute in the parties’ affidavits as to the

possible exposure in the office of the clerk of the district

court. The case should proceed promptly to resolution.

We approve the striking of the jury demand and reference

to the magistrate as special master. We decline to issue

the extraordinary writ sought.

The briefs, appendices and other papers filed with the

court are ordered sealed subject to further order of the

court.

4 28 TJ.S.C. § 636(b) (3) says:

A magistrate may be assigned such additional duties as are not

inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the United States.

5 See C.A.B. v. Carefree Travel, Inc., 513 U.2d 375, 379-81 (2d Cir.

1975).

6 Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 51 (1932). Note, Masters and Magis

trates in the Federal Courts, 88 Harv. L.Kev. 779 (1975).

5084

480-8-2-77 USCA— 4221

ME1LEN PRESS IN C , 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177

219