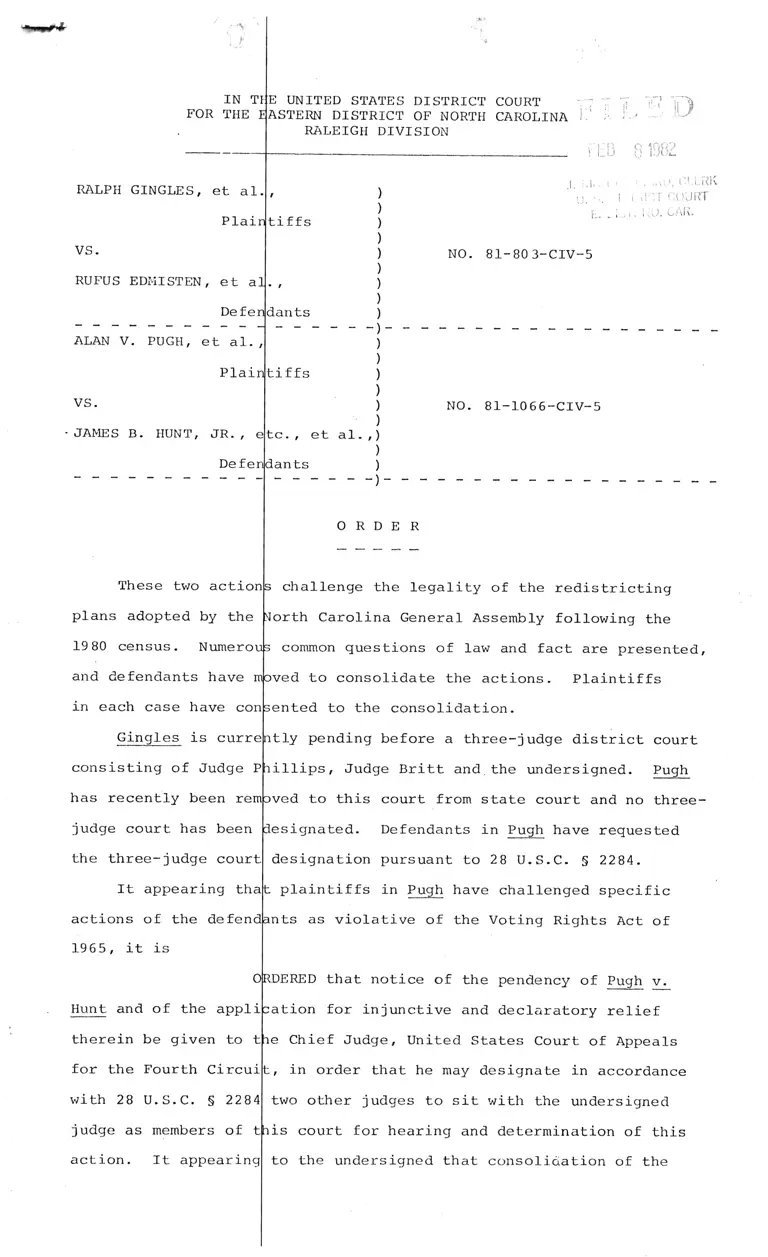

Order of February 8, 1982, Signed by F.T. Dupree, Jr., U.S.D.J.

Public Court Documents

February 8, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Order of February 8, 1982, Signed by F.T. Dupree, Jr., U.S.D.J., 1982. a3d37006-d392-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e58cf8c3-9b55-42b7-9088-01fc8dde8e10/order-of-february-8-1982-signed-by-ft-dupree-jr-usdj. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

\Err&

INT

FOR THE

RALPH GINGLES, et aI

Plai

VS.

RUFUS EDI{ISTEN, €t a

Defe

ALAN V. PUGH, €t al.,

VS.

JAIVIES B. HUNT, JR. ,

De fe

These two acti

plans adopted by the

19 B0 census. Numero

and defendants have

in each case have co

Gingles is curr

consisting of Judge

has recently been re

judge court has been

the three-judge cou

It appearing th

actions of the defen

1965, it is

Hunt and of the appli

therein

for the

with 28

judge as

action.

be given to

Fourth Circui

u. s. c. s 2284

members of

It appearin

E UNITED STATES DTSTRICT

ASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH

RALEIGH DIVISION

i ffs

NO. B1.BO 3-CIV-5

i. ilr',-

. ,, . l r,iii(

' r , i1.Jtl'I

' i'''l' t-,''ii'

,

ants

COURT

CAROLINA

Plai i ffs

DERED that noti-ce of

ation for injunctive

t.i,

li.,;_r

i,'

the pendency of Pugh v.

and declaratory relief

States Court of Appeals

NO. B1-1066-CrV-5

et aI.,

ants

ORDER

challenge the legality of the redistrictj_ng

orth Carolina General Assembly following the

common questions of 1aw and fact are presented,

ed to consolidate the actions. Plaintiffs

ented to the consolidation.

tly pending before a three-judge district court

iI1ips, Judge Britt and.the undersigned. pugh

ved to this court from state court and no three-

esignated. Defendants in Pugh have requested

designation pursuant to 28 U.S.C. S 2284.

plaintiffs in Pugh have challenged specific

nts as violative of the Voting Rights Act of

e Chief Judge, United

, in order that he may designate in accordance

two other judges to sit with the undersigned

is court for hearing and determination of this

to the undersigned that consoliciation of the

{*" i,

.,

I

two actions would be

requested to give c

hear Pugh as has bee

The Clerk is di

the Honorable Harri

Court of Appea1s, Ba

February 8, 1982.

-i

ppropriate, the Chief Judge is respectfully

ideration to designating the same panel to

designated to hear Gingl-es.

cted to mail a certified copy of this order

n L. Winter, Chief Judge of the United States

timore, Maryland, jud to counsel of rer/

74

UNITED

DUPREE, JR.

STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

,l''m'Ml#,m*I.*,.{:P-ffiHEa;ffiX,:--*offi{ffid**

:,?,;i;$ro_oi&U

Page 2