Bowen v. Gilliard Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bowen v. Gilliard Brief for Appellees, 1986. e7e72841-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e5f45f2a-52b8-41d4-8661-27ddf498cbfa/bowen-v-gilliard-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

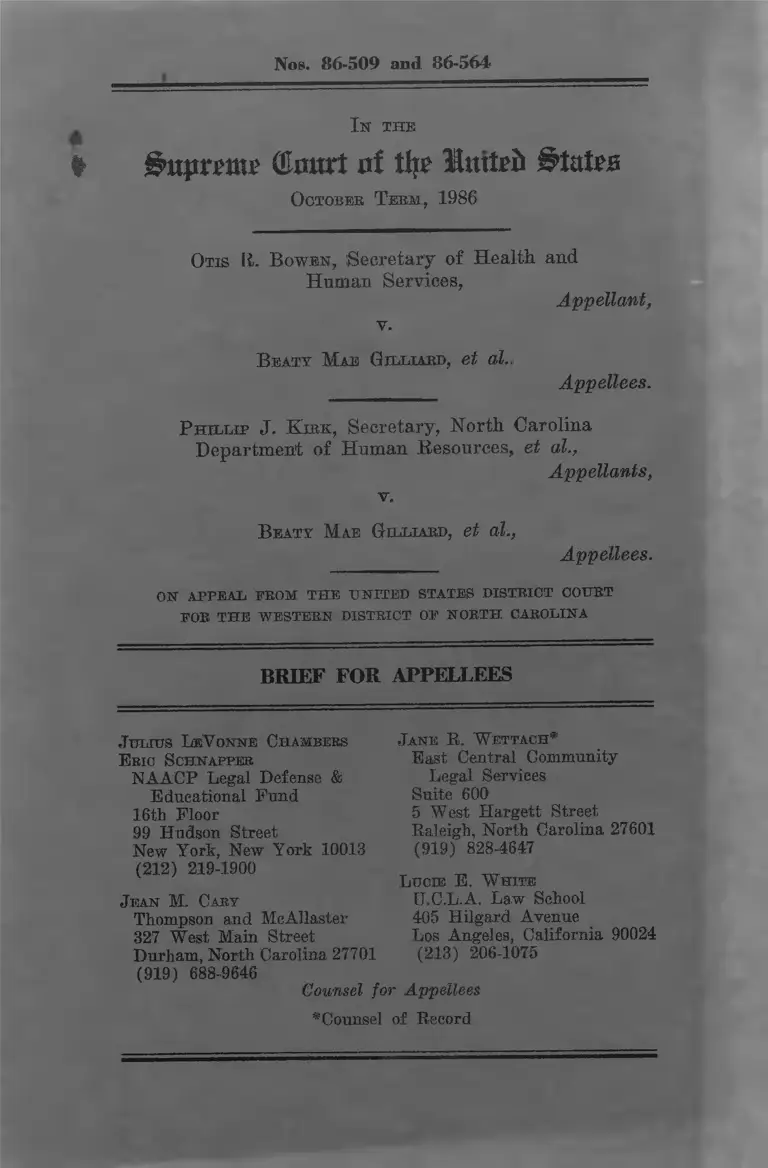

Nos. 86-509 and 86-564

I n THE

# Buptmt (Emtrt nt % Inttpft States

O ctober T erm , 1986

Otis It. Bowes, Secretary of Health and

Human Services,

Appellant,

v.

B eaty M ae B illiard, et al..

Appellees.

P h il l ip J. K ik e , Secretary, North Carolina

Department of Human Resources, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

B eaty M ae G illiard, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL prom t h e u n ited states district court

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OP NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

J ulius LbV onne Chambers

E ric Schnapper

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

J ean M, Cary

Thompson and McAllaster

327 West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina 27701

(919) 688-9646

J ane R. W bttach*

East Central Community

Legal Services

Suite 600

5 West Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina 27601

(919) 8284647

Lucie E. W hite

C.C.L.A. Law School

405 Hilgard Avenue

Los Angeles, California 90024

(213) 206-1075

Counsel for Appellees

* C ounsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does 42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(38)

authorize state officials to require

non-needy children to become welfare

recipients and to forfeit their

child support in order for their

custodial parents and indigent

siblings to receive Aid to Families

with Dependent Children?

2. If 42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(38) does

authorize such action on the part of

the state officials, is such a

procedure unconstitutional?

3. Where state officials knowingly and

deliberately violate a valid federal

injunction, does the Eleventh

Amendment preclude the federal

courts from ordering state officials

to return funds improperly taken or

l

withheld in violation of that

injunction?

Should Hans v. Louisiana. 134 U.S. 1

(1890), be overruled?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of the Case ............ 1

Statement of the Facts ........... 5

Summary of Argument ............. 15

Argument ........................ 22

I. The Appellants' Prac

tices Are Forbiddenby the Social Security

Act ...................... 22

II. The Appellants' Practices Work An Unconsti

tutional Taking ofPrivate Property ....... 64

A. Child Support Funds

Are Protected by the

Taking Clause ........ 65

B. The Constitution

ality of the Obligations Imposed

by Appellants' Prac

tices ........ 74

C. The Constitution

ality of Imposing Such Obligations As

A Condition of AFDC 83

iii

III. The Appellants' Prac

tices Unconstitutionally Burden Fundamental Rights ................

IV. The District Court

Properly Ordered The

State Appellants To

Return Funds Seized or

Withheld in Violation of that Court's 1971

Injunction ...........

Conclusion ..........

108

121

149

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Adickes v. S. H. Kress & Co.

398 U.S. 144 (1970)........ 70,73

Armstrong v. United States, 364

U.S. 40 (1960) ........... 75

Atascadero State Hospital v.Scanlon, 87 L.Ed.2d 171

(1985)................... .. 148

Bourque v. Commissioner of

Welfare, 6 Conn. Cir. 685,

308 A.2d 593 (1972)........ 62

Califano v. Jobst, 434 U.S. 47(1977)............ 113,114,115,118

California Federal S & L Assn,

v. Guerra, 93 L.Ed.2d 613 (1987)................ . 62

Carroll v. Commissioners of

Princess Anne, 393 U.S.

175 (1968)............ ... 137

Cleveland Board of Education

v. LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632

(1974)................... 110

Commmissioner v. Lester, 366

U.S. 299 (1961)........... 63

Craig v. Gilliard, 409 U.S.

807 (1972)............... .Passim

Dandridge v. Williams, 397

U.S. 471 (1970)......... 26

v

Ditmar v. Ditmar, 48 Wash.2d

373, 293 P.2d 759(1956)...... 67

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S.

651 (1974)......... 55,140,145

Gilliard v. Craig, 331 F.

Supp. 587(W.D.N.C.1971)...... Passim

Goodyear v. Goodyear, 257 N.C.

374, 126 S.E.2d 113

(1962) .............. . 66

Green v. Mansour, 88 L.Ed.2d

377 (1985)................. 148

GTE Sylvania, Inc. v. Con

sumers Union, 445 U.S. 375

(1980).................... . . 134

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890) .... ........... . . ii,148

Heckler v. Turner, 84 L.Ed.2d

138 (1985)................. 24

Hisquierdo v. Hisquierdo, 439 U.S. 572 (1979) .........____

Hobbie v. Unemployment

Appeals Commissioner (No.

61

8 5-9 9 3, Feb. 25, 1 9 8 7)...1 8,6 4,7 2 , 7 3

Howat v. Kansas, 258 U.S. 181

(1922)...................... 134

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S.

678 (1978)........... 21,144,145

In re Burns, 136 U.S. 588

(1890)...................... 61

vi

26

Jefferson v. Hackney, 406

U.S. 535 (1972)...........

Johnson v. Cohen, No. 84-6277

(E.D. Pa., Jan. 10, 1986).... 12

King v. Smith, 392 U.S. 309

(1968)............ ........ 25

Linda R.S. v. Richard D., 410

U.S. 614 (1973)............. 11

Lyng v. Castillo, 91 L.Ed.2d

527 (1986).................. Passim

Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v.

State Energy Resources

Comm'n, 461 U.S. 190(1983).................... . 62

Papasan v. Allain, 92 L.Ed.2d

209 (1986)... ........... 148

Pasadena City Bd. of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S.

424 (1976)............. 134,137,139

Pennsylvania v. Wheeling &

Belmont Bridge Co., 59 U.S.

421 (1856).................. 138,139

Pierce v. Society of Sisters,

268 U.S. 510 (1925)....... 109

Portsmouth Harbor Land &

Hotel Co. v. United States,260 U.S. 327 (1978)........ 93

Pruneyard Shopping Center v.

Robins, 447 U.S. 74(1980)...................... 60

vii

Pumpelly v. Green Bay Co.,

80 U.S. 166 (1872).......... 93

Rand v. Rand, 40 Md. App.

550, 392 A.2d 1149

(1978)..................... 67

Rosado v. Wyman, 397 U.S.

397 (1970).................. 24,26

Schweiker v. Gray Panthers,

453 U.S. 34 (1981)...... 23,25,42,49

Scott v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 46 Pa.

Commwlth. 403, 406 A.2d594 (1979)........ 67

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham,394 U.S. 147 (1969)......... 137

Smith v. Organization of

Foster Families, 431 U.S.

816 (1977).................. 110

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.S. 337

(1969)....... ........... 71

Swann v. Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971).......... 138

System Federation v. Wright,

364 U.S. 642 (1961) 138,139

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 394 (1977)........ 53

United States v. Causby, 328U.S. 256 (1946)............. 93

viii

United States v. Central

Eureka Mining Co., 357

U.S. 155 (1958)............. 75

United States v. United Mine

Workers, 330 U.S. 258

(1947)..... 134

Van Lare v. Hurley, 421 U.S.

338 (1975).................. 25

Wake County ex rel. Fleming v .

Staples, 86 CVD 446 (Wake

County, N.C., Oct. 1,

(1986)...................... 15

Walker v. City of Birmingham,388 U.S. 307 (1967)...21,134,136,137

Watkins v. Blinzinger, 789

F.2d 474 (7th Cir. 1986).... 53

Watts v. Watts, 240 Iowa 384,

36 N. W. 2d 347 (1949)........ 67

Wetmore v.Markoe, 196 U.S. 68

(1904)...................... 62

Zablocki v. Redhail, 434

U.S. 374(1978).. 108,113,114,115,116

Statutes

7 U.S.C. §2013. 32

7 U.S.C. § 2020(e) (2)....... 33

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (7)......... 27

ix

42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(8)(A)

(iii)...................... . 6

42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(8)(A)(vi)... 47

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (10) (A)..... 33

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (14)........ 31

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (17)........ 23

42 U.S.C. § 602(a) (18)....... 23

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (19) (A)..... 31

42 U.S.C. § 602(a) (23)........ 23

42 U.S.C. § 602(a) (26)........ 31

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (26) (B)..... 31

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (31)..... 23,25,48

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (35)........ 31

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (38)........ Passim

42 U.S.C. § 602 (a) (39)........ 25,49

42 U.S.C. § 615. .............. 25

42 U.S.C. § 657 (b) (i)......... 6

42 U.S.C. § 1396a (a)(17)

(D) . . . ...................... 49

N.C. Gen. Stat.§ BO-

13 . 4 (b)..................... 59

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 50-13.4(c)......................... 66

x

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 50-13.4

(d).......... ............. 58,66

Regulations:

45 C.F.R. § 232.11............ 3

Other Authorities:

Hearings before the Subcommittee on Labor,

Health and Human Services

of the Senate Committee,

95th Cong.,1st Sess.(1983)..................... 41

Hearings before the Subcommittee on Labor,

Health and Human Services of the Senate

Finance Committee, 97th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1982)..... 41

50 Fed. Reg. 9517

(March 8, 1985)............ 10

xi

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case originated in 1970 as a

challenge to a North Carolina practice of

improperly imputing income to recipients

of Aid to Families with Dependent

Children (AFDC) . At the time, North

Carolina automatically included all

children living in a household as members

of an AFDC assistance unit if an

application was made for any of the

children. This was true even when a

particular child received adequate child

support from his absent parent. The

whole family's grant was reduced by the

child support belonging to just one

family member. A three-judge court held

that to treat child support paid for a

specific child as a resource available to

the entire family worked an unlawful

appropriation of the funds of the

supporting parent and the recipient

child, in violation of the intent of the

2

Social Security Act and constitutional

principles. Gilliard v. Craig. 331 F.

Supp. 587, 593 (W.D.N.C. 1971). A

permanent injunction was entered,

prohibiting North Carolina from directly

or indirectly reducing AFDC payments to

eligible children by the amount of

legally-restricted child support income

received by other children in the

household. North Carolina Jurisdictional

Statement. A-108 to A-114, (hereinafter.

N.C.J.S.). This Court affirmed that

order. 409 U.S. 807 (1972).

In July, 1984, Congress enacted the

Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 (DEFRA),

which contained an amendment to the

Social Security Act regarding the

treatment of AFDC recipients who shared a

home with siblings not receiving AFDC.

Pub. L. No. 98-369, § 2640(a), 98 Stat.

1145, 42 U.S.C. (Supp. Ill) § 602 (a) (38).

The Department of Health and Human

3

Services interpreted section 602(a)(38)

to require termination of AFDC to such

recipients unless these non-recipient

siblings were also added to the welfare

rolls. 45 C.F.R. §206.10(a) (1) (vii) .

Once drawn into AFDC, their separate

income was counted as available to the

whole group and any child support

payments were required to be assigned to

the state. 45 C.F.R. § 232.11. North

Carolina officials, although aware that

this interpretation of section 602(a)(38)

conflicted with their obligations under

the 1971 injunction, did not return to

court to seek a modification of that

order. (N.C.J.S. A-78). Instead, in

October, 1984, the state officials began

systematically to violate the 1971

decree.

In May, 1985, a group of class

members injured by that violation

submitted to the district court a request

4

for further relief. (J.App. 30-34).

North Carolina then filed a third-party

complaint against Secretary Bowen,

claiming that the state's actions were

required by the new HHS regulations.

(J.App. 66-72). The district court

upheld the disputed HHS regulations as

consistent with section 602 (a) (38), but

held the statute and regulation

unconstitutional as applied to child

support recipients, and enjoined their

enforcement. (N.C.J.S. A-l to A-80).

The district court also concluded that

North Carolina officials had knowingly

violated the outstanding 1971 injunction,

and directed those officials to return

all funds seized or withheld in violation

of that earlier decree. (N.C.J.S. A-78

to A-80). The district court stayed its

order pending appeal. (N.C.J.S. A-148).

Both the federal and state defendants

5

appealed; on December 8, 1986, this Court

noted probable jurisdiction.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

In October, 1984, North Carolina

notified all AFDC recipients who lived

with non-AFDC siblings that their AFDC

grants would be terminated unless they

reapplied for AFDC and agreed to put

those siblings on public assistance.

Prior to that date, for example, Dianne

Thomas and her daugher Crystal had been

receiving a monthly AFDC grant of $194

because Crystal's father paid no child

support. Ms. Thomas had not requested

assistance for her son Sherrod, however,

because he was adequately supported by a

$200 monthly support payment from

Sherrod's father Ms. Thomas was told

that she could not receive AFDC for

herself and Crystal unless Sherrod also

went on welfare. (N.C.J.S. A-14). When

Ms. Thomas and other AFDC parents

6

submitted the required application, they

were also told that all aid would be

denied unless they assigned to the state

the support payment of the non-indigent

child. (N.C.J.S. A-16). The state

retained most of each support payment,

providing the applicants with a small

additional grant for the non-indigent

applicant, plus in most instances a

statutory $50 pass through.1 The actual

additional grant for a child such as

Sherrod Thomas was $29 (Table 4 J. App.

52) .

The appellants' practice of

mandating participation in AFDC by non-

needy siblings had two immediate

consequences. First, approximately 15%

1 42 U.S.C. § 657(b)(1) requires

the child support enforcement agency to

pass through to the family the first $50 paid in child support in a particular

month. 42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(8)(A)(vi)

requires the AFDC program to disregard

this $50 in calculating the family's income.

7

of the affected AFDC recipients were

terminated from the North Carolina AFDC

program from 1984 through 1986 because

state officials calculated that the

support payments to their siblings were

sufficient to support the entire family.

Second, in about 85% of the cases a child

with independent support was conscripted

onto the rolls and his child support was

taken by the state. See lists of Class

Members filed Dec. 11, 1986, J. App. 16.

State officials then disbursed for that

child an additional AFDC allotment which

was substantially less than the amount

the state had actually received. Prior

to October, 1984, for example, Diane

Jefferys was receiving $204 a month in

child support for two of her children,

Latoya and Anthony, who were not on AFDC;

after Ms. Jefferys complied with the

state's direction to put both children on

AFDC, the state received the $2 04 each

8

month, but disbursed for the children

only an additional $71. After passing

through the $50 disregard, the state

retained the balance of $83 to help

defray the overall cost of the AFDC

program. (N.C.J.S. A-29). Similarly, in

August, 1985, North Carolina received a

check for $810 to cover several months of

accumulated support payments for two

children of Arvis Waters; state officials

actually disbursed to Ms. Waters only $50

of that amount, and retained the

remaining $760. (N.C.J.S. A-27)

This practice of expropriating most

of the child support payments involved

several direct and foreseeable

consequences. First, of course, it

drastically lowered the standard of

living of the supported children whose

support payments were partially

expropriated by the state. The money

available for Latoya and Anthony

9

Jefferys, for example, immediately fell

by more than half. Ms. Jefferys and her

children were soon evicted from their

house, and Ms. Jefferys was unable to buy

either clothes or shoes for children who

had had both prior to 1984. (J. App.

134-135) . Other supported children

suffered in a similar manner because the

state was seizing a substantial portion

of their support funds. (N.C.J.S. A-13

to A-30). The state retains on average

$50 to $100 from each monthly child

support payment, one third to one half of

each such payment.2 Having been thus

conscripted onto the AFDC rolls, the

2 See N.C.J.S. A-14 (monthly

support payment of $200; net additional

allotment of $29 plus $50 pass-through);

A—21 to A-22 (monthly support payment of

$189; net additional allotment of $44 plus $50 pass-through; A-23 to A-24

(monthly support payment of $190; net

additional allotment of $44) ; A-28 to A- 29 (monthly support payment of $204; net

additional allotment of $36 plus $50 pass-through) ; cf. J. App. 109 (average

"reduction" of $103).

10

formerly self-sufficient children were

forced to subsist on grants equal to

about 30% of the federal poverty level.3

Second, once the fathers of the

supported children learned that most of

the support payments were actually going

to the Department of Human Resources,

rather than to their own children, many

of them terminated or reduced those

payments. The father of Latoya and

Anthony Jefferys stopped making support

payments several months after the

assignment began, because, Ms. Jefferys

reported, "he feels like when he pays,

his children do not really benefit."

(N.C.J.S. A-29). State officials were

evidently unable to bring about a

resumption of those support payments.

The father of Sherrod Thomas had

Compare table 4, J.App. 52

(North Carolina payment standard) with 50 Fed. Reg. 9517-18 (March 8, 1985) (federal poverty guidelines).

11

regularly and voluntarily been paying

$200 a month for the child's support, but

ceased making those payments as soon as

they were assigned to the state;

subsequently state officials were able to

induce the father to resume support

payments, payable to the state, of $87 a

month. (N.C.J.S. A-16 to A-17; see also

id. at A-20, A-68 to A-73).

A state judge explained that as a

practical matter North Carolina courts

have few effective tools for compelling

an unwilling father to make support

payments, since garnishment of a father's

wages frequently results in his

dismissal, and imprisonment "rarely

results in income for the family."

(N.C.J.S. A—53). Cf. Linda R.S. v.

Richard D. . 410 U.S. 614 (1973). Prior

to 1984, the most effective judicial tool

for inducing fathers to make support

payments was emphasizing the importance

12

of keeping the child at issue off the

public assistance rolls. (N.C.J.S. A-72

to A—73). The judge explained that she

expected 81 to continue hearing father's

refusals to pay child support when they

learn that their child support is being

paid to the Department of Human Resources

instead of to their children, and when

they discover that their child is on

welfare even though they are paying

support regularly." (N.C.J.S. A-72).4

4 The district court in Johnson

v. Cohen. No. 84-6277 (E.D. Pa. Jan. 10,

1986) , appeal pending, No. 86-1101 (3d

Cir.) found the disputed practices,

reduce the incentive a father might

have to provide child support

willingly. The sibling deeming r u l e s will i n c r e a s e the

unwillingness of fathers to pay

child support because payments by

the father will not have demonstrable benefits to the child,

and because the child support payments will be subsidizing other

members of the household. The sibling deeming rules will result in

increased resistance to paying child support.

13

Third, the disputed practices

poisoned in a variety of ways relations

among the family members involved. Non

custodial fathers ready and willing to

support their children.were predictably

angered to learn that they were

effectively forbidden to do so because

the mother, having had one or more

children by another less responsible man,

was seeking AFDC for those other

children. (N.C.J.S. A-14, A-71).

Because the mandatory assignment

terminated the normal support

relationships between the non-custodial

parent and the child, some of those

parents reduced or ended their non-

financial relationship with the children,

in turn inducing emotional problems among

the children. (N.C.J.S. A-17). Some

custodial parents have surrendered

custody of supported children in order to

avoid seizure of the children's support

14

funds. (N.C.J.S. A-19).

Finally, the state officials have

moved aggressively to prevent non

custodial parents from providing in-kind

support which the state cannot

effectively seize and profit from. After

the birth of his son Jermaine, for

example, James Richardson regularly

provided the child with food, clothing

and diapers, and paid directly some of

the related household bills. When

Richardson refused to agree instead to

pay the state $165 a month, of which only

$50 would go to Jermaine, he was

prosecuted for criminal non-support.

(N.C.J.S. A-20). Similarly, Rick Staples

was directly providing to his child

Kristen clothing, food, furniture,

medicine and other needed items. After

Kristen7 s child support rights were

assigned by the child's mother as a

condition of her receipt of AFDC for two

15

other children, state officials brought a

civil action against Staples to enjoin

him from continuing to provide such in-

kind assistance to his daughter. The

Wake County district court judge found

that it would not be in Kristen's best

interest for the father to pay monetary

support rather than purchase necessities

directly and denied the agency's

complaint. Wake County, ex rel. Carol

Fleming v. Rick Staples. 86 CVD 4461

(Wake County) (Oct. 1, 1986) appeal

dismissed, 86 10DC1351 (N.C.Ct. App. ,

Feb. 2, 1987).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

(1) Section 602(a)(38), as the

government construes it, requires as a

condition of ADFC eligibility that an

applicant's non-needy siblings also go on

welfare, and forfeit to the state any

child support payments. The actual

language of section 602 (a) (38), however,

16

makes no reference to requiring anyone to

actually apply for or receive public

assistance. Rather, the statute simply

mandates that an adjustment be made in

"the determination" of the size of the

grant to those individuals who actually

desire AFDC assistance.

The history of the statute does not

contain, as the Solicitor suggests,

"legislative findings that family members

who live in the same household pool their

resources." (U.S. Br. 41) . Section

602 (a) (38), unlike the statute in Lvnq v.

Castillo. 91 L.Ed.2d 527 (1986), was not

preceded by or based on any congressional

hearings regarding the actual practices

of AFDC recipients. The legislative

history of section 602(a)(38) suggests,

at most, that Congress intended to

require the states to "take into

consideration" the extent to which the

income of non-AFDC children was in fact

17

reducing the net needs of AFDC recipients

with whom they lived.

The HHS regulations effectively

strip state judges of the power to direct

a child support payment to a specific

child if he or she resides in a household

with AFDC recipients. The regulations

have the practical effect of converting

any such state decree into an award to

the entire family, despite the intent of

the state court and despite the fact that

state law does not permit child support

funds to be used for others in the

household. Neither the language nor the

legislative history of section 602(a)(38)

indicate an intent to pre-empt state

domestic relations law in this way.

(2) This is not, as was true in

Lvnq. simply a case in which aid

recipients are complaining that the

amount of their benefits has been

reduced. Indeed, in most instances, the

18

HHS regulations actually result in a

small increase in the AFDC grant. The

issue here, rather, is whether the HHS

regulations attach an unconstitutional

condition to the receipt of that aid.

Cf. Hobbie v. Unemployment Appeals

Commission. (No. 85-993, Feb. 25, 1987).

In this case a custodial parent seeking

AFDC is required to turn over to the

state the child support payments for her

non-needy children, even though those

children neither want nor need AFDC.

North Carolina turns a substantial net

profit by thus conscripting supported

children into AFDC, paying out in

additional benefits for those children

several million dollars less than the

total amount of support funds which the

state receives for them.

The government's practices

constitute a taking of private property

without just compensation. The child

19

support payments diverted to and retained

by the state are undeniably the private

property of the supported child. In

diverting those funds to the government

rather than spending them on the

designated child, the mother acts at the

behest and on behalf of the state. The

consequences of a loss of AFDC to her

other children are so catastrophic that

the mother has no choice but to act as an

agent of the state and make the demanded

assignment; the child on whom the funds

should have been spent literally has no

choice in the matter.

The Solicitor argues that the amount

of each child's support funds thus

expropriated is "not so great as to

effect a taking." (U.S.Br. 37). But the

amount of money taken is of enormous

importance to the comparatively poor

individuals affected. The government

asserts that no taking has occurred

20

because the incremental grant paid for

each affected child, although less than

the amount seized, nonetheless "reflects

the needs of the child." (U.S.Br. 39).

The Taking Clause, however, does not

permit the government to take from each

according to his ability, merely because

it purports to provide to each according

to his needs.

(3) The actions of the state

appellants violated a 1971 injunction

which had been affirmed by this Court.

Craig v. Gilliard. 409 U.S. 807 (1972).

The district court concluded that the

state officials knew that their conduct

was forbidden by the terms of the 1971

order. (N.C.J.S. A-78, A-79).

The state appellants argue that the

1984 adoption of section 602 (a) (38)

removed the legal basis on which the 1971

injunction rested. These appellants now

assert that the 1971 opinion relied

21

solely on the Social Security Act as it

was then written; in their 1972 appeal to

this Court, however, the state appellants

insisted that the 1971 opinion rested on

constitutional grounds. If the state

officials believed that the enactment of

section 602(a)(38) did undercut the basis

of the 1971 injunction, they were

obligated to obey that injunction until

it was modified by the court. Walker v.

City of Birmingham. 388 U.S. 307 (1967).

The state appellants assert that,

even if they knowingly violated the 1971

injunction, the Eleventh Amendment

precludes the district court from

directing a refund of money seized or

withheld in violation of that decree.

"Federal courts are not reduced to

issuing inj unctions against state

officers and hoping for compliance. Once

issued, an injunction may be enforced."

Hutto v. Finnev. 437 U.S. 678 (1978).

22

The remedial order of the district court

simply enforces the prospective 1971

injunction by requiring state officials

to do today what the 1971 injunction

required to be done in 1984-86.

I. THE APPELLANTS ' PRACTICES ARE

FORBIDDEN BY THE SOCIAL SECURITY ACT

Congress enacted section 602(a)(38)

to require that where a parent and child

receiving AFDC live together with a child

receiving income such as child support

payments, the AFDC grant to the parent

and indigent child would be adjusted to

take into account the economic benefits

which those AFDC recipients receive as a

result of the presence of that non-AFDC

child. The statutory issue presented by

this case concerns the nature of the

adjustment which is authorized by section

602 (a) (38) . The actual language of

section 602 (a) (38) , like much of the

Social Security Act, is "almost

unintelligible to the uninitiated."

23

Schweiker v. Gray Panthers. 453 U.S. 34,

43 (1981) . To understand the meaning of

that section, it is necessary to begin

with the statutory scheme onto which it

was engrafted, and the state of the law

prior to 1984.

(1) The states participating in the

AFDC program are given discretion in

determining the size of the grants they

will make, subject to certain limitations

embodied in the Social Security Act and

the applicable regulations.

Generally, a state must begin with a

"standard of need."5 This is the amount

which the state determines is necessary

to meet essential needs; the level

generally varies with the number of

individuals in the household, on the

theory that those who are part of the

The state standard of need is

referred to in several parts of the

statute. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 602(a)(17),

602(a)(18), 602(a)(23), 602(a)(31).

24

same household experience certain economy

of scale savings. Cf. Lvnq v. Castillo.

91 L.Ed.2d 534-35. A state cannot alter

its standard of need merely to lower the

benefit to be paid; the state may choose

to make actual grants too small to meet

the standard of need, but it cannot

achieve or obscure that result by

doctoring the standard of need itself.

Cf. Rosado v. Wvman. 397 U.S. 397, 413-14

(1970).

Second, a state computes the

countable income of each applicant. This

computation is subject to the "actual

availability principle," which precludes

a state "from relying on imputed or

unrealizable sources of income

artificially to depreciate a recipient's

need." Heckler v. Turner. 84 L.Ed.2d

138, 150 (1985). The most important

application of this principle is to bar

states from reducing or denying benefits

25

on the theory that an applicant is

receiving presumed but non-existent

income from another person in the

household. King v. Smith. 392 U.S. 309

(1968); Van Lare v. Hurley. 421 U.S. 338

(1975). In some instances, however,

Congress has created an express exception

to the principle, permitting a state to

"deem" available to an AFDC applicant a

specified portion of the income of

another party, regardless of whether it

is in fact received. The amount "deemed"

available is determined by subtracting

from the third party's income that

party's own standard of need, and making

certain other adjustments. 42 U.S.C.

§ 602(a)(39) (grandparents), § 602(a)(31)

(stepparents); § 615 (alien sponsors).

Cf. Schweiker v. Gray Panthers. 453 U.S.

34 (1981) (spouses).

Third, having computed a countable

income for the applicants, the state

26

calculates the grant amount. The Social

Security Act does not mandate a

particular method of calculation.

Jefferson v, Hacknev. 406 U.S. 535

(1972). For example, the state may pay a

specified percentage of the difference

between the countable income and the

applicants' needs. Rosado v.Wyman. 397

U.S. at 409 and n. 13. Alternately, the

state might choose to set a maximum on

the size of the grant, regardless of the

applicants' needs. Dandridcte v.

Williams. 397 U.S. 471 (1970). Or, like

North Carolina, a state may apply a

percentage reduction to the standard of

need, and then subtract countable income

from that figure. (J. App. 77-78).

Prior to 1984, states participating

in the AFDC program did not as a general

practice take into consideration how the

need and income of an applicant might be

affected by the presence in the home of a

27

child who was not seeking AFDC because he

or she had a separate source of income

such as child support. Section

602(a)(38) was enacted to require the

states to make an adjustment in their

AFDC grants because of the presence of

such children; what that adjustment was

to be remains in dispute.

(2) Section 602(a)(7) provides

that, "in determining [the] need" of an

AFDC applicant, a state "shall take into

consideration any ... income" of the

applicant or certain other individuals.

Section 602(a)(38) states in pertinent

part that

in making the determination

under paragraph (7) with

respect to a dependent child

. . . the State agency shall .. . include

* * *

(B) any brother or sister of such child ... if such

brother, or sister is living in

the same home as the dependent child, and any income of or

available for such ... brother,

28

or sister shall be included in

making such determination ....

Section 602(a)(7) and 602(a)(38), read

together, require that, in determining

the need of the parent and indigent child

or children applying for AFDC, the state

will "include" any children who may not

be seeking AFDC, and "take into

consideration" the income of those

children. Section 602(a)(38) clearly

requires that some sort of adjustment be

made in an AFDC grant when there are

supported children in a household, but

the statutory language itself provides

little guidance as to what that

adjustment is to be.

Here, as has occurred before in

other contexts, section 602(a)(38) was

framed in the sort of opaque language

that so often facilitates the legislative

process but complicates the work of the

judicial branch. Although the vague

language of section 602(a)(38) is

29

susceptible of several quite different

interpretations, each of those

alternatives is itself quite simple.

Either the Administration, which

originally proposed this amendment, or

the Senate Finance Committee, which first

approved it, could readily have framed a

statute or explanation free of ambiguity,

but they chose not to do so. In the face

of this studied opacity one cannot assume

that the framers of section 602(a)(38)

intended to reject any of the benefit

adjustment methods set forth with greater

specificity in other parts of the Social

Security Act; the only thing which the

framers of section 602(a)(38) clearly

rejected was clarity itself.

(3) The Solicitor General argues,

however, that the purpose of section

602(a)(38) was not to alter the method of

calculating the grants for individuals

who actually wanted AFDC assistance.

30

Rather, he asserts, Congress enacted

section 602(a)(38) to require, as a

condition of AFDC assistance to a needy

child, that all the child's siblings be

put on AFDC, including children who

neither wanted nor needed government aid,

and that all the child support payments

of those conscripted siblings be assigned

to the government. The effect of the HHS

regulations implementing this view has

been to add several hundred thousand

unwilling participants to the AFDC rolls.

The language of section 602(a)(38)

is difficult to reconcile with the

Solicitor's proposed interpretation.

Section 602(a)(38) contains no language

suggesting that supported children or

anyone else must apply for AFDC, or live

on welfare rather than rely on support

from a non-custodial parent. Indeed,

sect ion 602 (a) (38) , unlike other

31

provisions of the statute,6 does not

impose any obligations at all on AFDC

applicants themselves; the commands of

section 602(a)(38) are directed solely at

the state AFDC officials calculating the

size of the grant to be awarded to actual

applicants. Section 602(a)(26), which

requires the assignment of child support

funds, is expressly applicable only to an

“applicant or recipient;" a member of

Congress familiar with section 602 (a) (26)

would have had no reason to think that

602 (a) (38) would extend that mandatory

assignment provision to children who

neither wanted nor needed AFDC.

If Congress had intended actually to

° See, e.q.. 42 U.S.C. §§602(a)(14) (recipients required to submit

reports) , 602 (a) (19) (A) (certainrecipients required to register for

employment-related activities) ;

602 (a) (26) (B) (recipients required to assist state in establishing paternity of

children born out of wedlock), 602(a)(35)

(state may require recipients to look for work).

32

require that supported children go on the

AFDC rolls, it certainly knew how to do

so. The Food Stamp Amendments of 1982,

enacted the same year that section

602(a)(38) was first proposed, expressly

contained just such a requirement. The

Food Stamp Program provides funds, not to

individuals, but to "households" whose

composition is specified by statute. An

application must be made on behalf of a

"household;" thereafter it is the

statutorily defined "household" whose

needs and income are considered, and to

whom the foods stamps are allotted. 7

U.S.C. §§ 2013 et sea. In 1982, when

Congress redefined the Food Stamp

household to encompass siblings, that

statutory change clearly mandated that

such siblings apply for and comply with

the provisions of the Food Stamp program.

Cf. Lvncf v. Castillo. 91 L.Ed.2d at 532

n. 1. AFDC, on the other hand, remains

33

as it was prior to 1984 a statutory

scheme which focuses on individuals.

Requests for AFDC are made, not by a

statutorily defined entity, such as a

"household, *' but by "individuals wishing

to make application for aid." Compare 7

U.S.C. § 2020(e)(2) with 42 U.S.C. §

602 (a) (10) (A) . Thus the 1984 AFDC

legislation clearly did not compel

participation in that program by

individuals who did not wish such

assistance.

The legislative history of section

602(a)(38) provides no support for the

government's interpretation of the

statute. The Solicitor does not suggest

that any member of Congress ever actually

said that additional children would be

required to go on AFDC, or that support

payments for children who did not want

AFDC would be assigned to the government.

For years critics of AFDC had argued that

34

the very status of being on welfare had a

debilitating effect on the morale and

aspirations of children; surely one of

these critics would have spoken out if it

were understood that section 602(a)(38)

would require placing on the welfare

rolls several hundred thousand children

who were then being supported directly by

their own parents. At the time when

DEFRA was adopted, the overriding issue

dividing Congress was whether the deficit

should be cut through reductions in

spending or increases in taxes. Section

602(a)(38) as the Solicitor construes it,

was intended literally to take $150

million a year from fathers and children

not then on AFDC, and funnel it back

through the states to the federal

government. Had it been generally

understood that this was to be the effect

of section 602(a)(38), it seems likely

that someone would have objected that it

35

had all the trappings of an

extraordinarily retrogressive tax.

The Solicitor bases his statutory

argument on an assertion that there were

"legislative findings that family members

who live in the same household pool their

resources" (U.S. Br. 41), but this

enticing assertion is not accompanied by

any reference to the phrase "pool their

resources" in the legislative history.

Elsewhere in his brief the Solicitor

describes these purported findings in

very different terms, suggesting

variously, that Congress found that such

indigent families "share":

-"the expense of common necessities"

(U.S. Br. 20)

-"the cost of obtaining life's

necessities" (U.S. Br. 21)

-"expenses" (U.S. Br. 10, 41)

-"resources" (U.S. Br. 29, 41)

-"income" (U.S. Br. 10, 41)

These quite different "findings" would

36

support very different interpretations of

the statute. If Congress acted on a

finding that such families share the

"expense of common necessities," such as

rent and utilities, it presumably

contemplated only an economy of scale

adjustment based on the lower per capita

cost of those common needs. Attempting

to escape the palpable distinction

between the sharing of certain common

expenses and a pooling of all income, the

Solicitor asserts that not only shelter

and utilities, but also "transportation

and clothing ... are ordinarily regarded

as shared expenses." (U.S. Br. 33). If

a mother were to spend $10 on diapers for

an infant son, a dress for a young

daughter, or a blouse for herself, it

would be strange indeed to describe that

expenditure as meeting a "shared expense"

of all three. Similarly, for the

majority of AFDC recipients who travel on

37

public transportation, the fares

involved, unlike the cars of more

affluent families, are not a shared

expense.

(4) The Solicitor General urges the

Court to apply to the disputed HHS

regulations the deference usually

accorded an agency responsible for

administering a statute. (U.S. Br. 24) .

That deference is appropriate in the

ordinary case in which the agency at

issue not only has relevant technical

expertise, but also agrees with the

purposes and priorities that prompted

Congress to enact the underlying statute.

But there are some instances in which

such agreement does not in fact exist.

The very independence of the executive

and legislative branches guarantees that

there will be important, deeply felt

differences regarding federal policies;

such differences will inevitably mean

38

that Congress will at times adopt

legislation opposed by executive

officials, or will reject in whole or

part administration legislative

initiatives. The courts, in determining

the significance of an agency's

interpretation of a statute, must as a

general rule bear in mind the possible

existence of such differences.

Caution is particularly appropriate

in construing legislation framed by the

executive branch and enacted by a

reluctant Congress. Such legislation

necessarily represents a compromise of

the differing policies and priorities

which animate the two branches of

government involved. Because of those

differences, such a statute, like a

contract drafted by one of two parties

with adversarial interests, must be

construed to embody only those

concessions to administration policy

39

which Congress would clearly have

understood it was making. It is vital to

the integrity of the legislative process

that executive agencies not be permitted

to give to a statute, after enactment, an

interpretation more favorable to the

administration's perspective than the

construction clearly offered by the

agency when the legislation was still

before Congress.

During the years immediately

preceding the enactment of DEFRA, the

most consistent and heated differences

between Congress and the executive branch

concerned the level of benefits to be

provided to the indigent under various

social welfare programs. The

administration strongly favored reducing

the deficit by cutting such social

welfare spending, while Congress often

objected to placing the burden of deficit

reduction on the less affluent Americans

40

who depended on federal aid. The debate

over proposals to reduce AFDC benefits to

households with supported children was

not an isolated skirmish, but part of a

wide-ranging and continuing struggle,

rooted in fundamental differences

regarding economic and fiscal policy.

For two and a half years officials

of the executive branch lobbied a

reluctant Congress to reduce AFDC

benefits for recipients in households

that included supported children.

Executive branch officials proposed

statutory language which contained no

reference to requiring that supported

children be placed on AFDC, and no

reference to requiring assignments of the

support payments of children who did not

want AFDC. Between January 1982 and July

1984 executive branch officials commented

on their proposals in testimony,

41

correspondence, and budget messages.7

Not once during this entire process was

there any mention of compulsory welfare

or mandatory assignments. Only weeks

after congressional approval had been

obtained, however, HHS produced explicit

regulations mandating the disputed

practices.

The rules of statutory construction

should take account of the difficulties

often faced by Congress in framing

legislation. Executive branch officials

trying to win enactment of a contested

piece of legislation, like any other

' Departments of Labor, Health

and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies Appropriations for 1984:

Hearings before Subcommittee on the

Department of Labor, Health, and Human

Services, Education and Related Agencies,

98th Cong. 1st Sess. 528-529 (1983): Departments of Labor, Health and Human

Services, Education and Related Agencies Appropriations for 1983: Hearings before

Subcommittee on the Departments of Labor,

Health, and Human Services, Education and

Related Agencies, 97th Cong. 2d Sess.

572-573 (1982). J. App. 168-69.

42

lobbyists, are unlikely to warn that the

measure might have a meaning which would

increase opposition on the Hill. An

unfortunate but undeniable part of

relations between these two branches of

government is that executive officials at

times utilize their particular expertise

and knowledge to frame proposals,

statements and testimony which, although

not literally inaccurate, may convey to a

busy Congress an impression somewhat at

odds with the actual understanding or

intent of those executive officials. The

danger of such "misunderstandings" is

particularly great in dealing with the

Social Security Act, whose very

terminology is "an aggravated assault on

the English language, resisting attempts

to understand it." Schweicker v. Gray

Panthers, 453 U.S. at 43, n. 14.

Whatever the drafting problems posed

by the Act itself, it is very easy to

43

articulate in ordinary English the

construction which the government now

wishes to place on section 602(a) (38).

The Secretary of HHS was able to do so

with ease and dispatch as soon as the

statute was adopted; the Solicitor

General explains that proposed

construction with his usual clarity, and

offers the Court a helpful "simplified

example" to illustrate his meaning. But

neither that straightforward construction

nor that example was ever offered to

Congress. Prior to September, 1984,

executive branch officials systematically

avoided referring either to compulsory

AFDC or mandatory assignments of child

support. It is of no importance that the

words used by those executive officials

might have carried a second meaning,

apparent to the cognoscenti within the

HHS bureaucracy, different than the

understanding that would have been

44

conveyed to an ordinary member of

Congress, for it is the understanding and

intent of Congress that controls.

(5) Our view that section

602 (a) (38) was intended to adjust the

grants of actual recipients, rather than

to conscript unwilling individuals onto

the public assistance rolls, does not by

itself provide a full explication of the

meaning of the statute. There remains to

be resolved what type of adjustment is

authorized by the statute. Congress

certainly did not intend to give HHS

unlimited discretion to devise whatever

draconian adjustment scheme would most

severely slash AFDC grants. Neither the

statute nor the relevant committee

reports specify what sort of grant

reduction is to occur under what

particular circumstances. In light of

the vague record, and of the much vetted

differences between the legislative and

45

executive branches regarding the

appropriate level of support for indigent

recipients of federal aid, the Court must

attempt to determine what type or types

of grant reduction Congress could clearly

have understood it was authorizing when

it adopted section 602(a)(38).

We believe that section 602(a)(38)

might plausibly be read to support either

of two interpretations. First, it may be

that, as the Solicitor appears to

suggest, Congress was concerned that AFDC

recipients in homes with supported

children were less needy because they

enjoyed the benefit of the economies of

scale that occur in larger households.

(U.S. Br. 29? cf. Lvng v. Castillo. 91

L . Ed.2d at 532-33). Although some

expenses, such as clothing, school

supplies, and public transportation, are

largely individual, other expenses—

particularly rent and utilities — can

46

readily be shared, and are ordinarily

lower per capita in a larger household.

North Carolina AFDC practice quantifies

the economies of scale that occur,

providing for a lower per capita AFDC

grant in larger families.8 If the

purpose of section 602(a)(38) was to

require an economy of scale adjustment,

that could be achieved simply by basing

the grant on the per capita level

appropriate for the total number of

applicants and supported children in the

8 The per capita AFDC, the

standard of need and payment standard in

1984 were as follows:

Persons In Household

Per Capita

Standard of

Need

Per capita

Payment

1 $296 $148.00

2 194 97.00

3 149 74.50

4 122 61.00

5 107 53.50

6 96 48.00

7 88 44.00

8 80 40.00

J. App. 51-52, Tables 2 and 4.

47

household, rather than on the higher per

capita level for a household including

only the applicants.9 This economy of

scale reduction in the grant would

"include" the non-needy children and

their income in the "determination" of

the per-capita need and grant, doing so

in a manner which would "take into

consideration" the economies of scale

realized because of the incomes of those

non-needy children.10

y For example, prior to the adoption of section 602(a)(38) the grant

for a parent of one child would have been

$194, regardless of the number of non-

needy children in the home. Under an

economy of scale adjustment, the presence

of one such non-needy child would lower

the per capita payment level from $97.00

to $74.50, thus reducing the actual grant to $149. Similarly, if a mother and two

needy children shared their home with two

non-needy children, their grant would be reduced from $223 to $160.00.

10 O n t h i s r e a d i n g 42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(8)(A)(vi) would

prohibit such an economy of scale reduction if the total child support received by children in the family was less than $50.

48

Section 602(a)(38) might be read, in

the alternative, to mandate effective

state measures to assure that any income

of non-AFDC children which was in fact

provided to AFDC siblings would be

counted as income to those siblings. It

is unlikely, however, that Congress

intended to permit the state to count all

of a non-AFDC child's income as income to

the AFDC recipients in the household.

Because any such deeming rule would

violate the principle of availability,

Congress has always spoken unambiguously

when it wished to deny grant applicants

the opportunity to prove that they were

not actually receiving presumed income.

The statute in Lvnq. for example,

expressly denied siblings the chance,

afforded to unrelated individuals in a

common home, to prove that they were not

sharing the cost of preparing meals. See

91 L .Ed.2d at 534-35. Sections

49

602(a)(31) and 602(a)(39) establish

specific fixed formulas for calculating

the amount of stepprent and grandparent

income which must be treated as available

to AFDC recipients in the household.

This Court found similar deeming

authorized under the Medicaid Act because

of a statutory provision permitting a

state to "take into account the financial

responsibility of any individual for any

applicant or recipient ...[if] such

a p 1 i cant or recipient is such

individual's spouse." 42 U.S.C. §

1396a (a) (17) (D) . Schweiker v. Gray

Panthers. 453 U.S. 34, 44-46 (1981).

Section 602 (a) (38), on the other hand,

contains no such express language

permitting a departure from the principle

of availability.

The circumstances leading toi the

adoption of section 602(a)(38) are

strikingly different than those which

50

amendments in Lvnq. The Congress that

adopted the Food Stamp amendments was

prompted by a substantial body of

evidence, garnered in a series of House

and Senate hearings, that Food Stamp

recipients were fraudulently denying that

they shared their food costs, and that

individualized detection of that abuse

was impracticable, Lvnq v, Castillo. 91

L.Ed.2d at 534-35 and nn. 4-6; Brief for

the Appellant, No. 85-250, pp. 18-19 and

nn. 13-19. The Food Stamp amendments

were a carefully considered legislative

response, albeit a drastic one, to a

clear and intractable problem. The

legislative history of section

602 (a) (38), on the one hand, contains no

allegations of any similar abuse

regarding the use of child support funds,

and no suggestion that the detection of

any such abuses would be so difficult as

to require the type of rigid rule

51

involved in Lvng. Congress did not hold

so much as a day of hearings regarding

the practices of AFDC recipients residing

with supported children. It seems

unlikely that Congress would have

resorted to the sort of harsh measure

involved in Lvng in the absence of any

evidence of an abuse requiring such a

remedy.

The legislative history does not, as

the Solicitor suggests, contain any

congressional finding that AFDC

recipients and supported children in the

same household in fact pool all their

income and use it to meet the expenses

incurred by each of them. The passage of

the Senate report on which the Solicitor

places primary reliance explains:

This change will . . . ensure that the income of family

members who live together and

share expenses is recognized

and counted as available to the

family as a whole. (S.Prt. 98- 169, at 980)

52

The Solicitor suggests that this sentence

constitutes a finding that family members

who "live together" generally or always

"share expenses."11 That might be a

plausible interpretation if the report

referred to family members "who live

together, and thus share expenses." But

the passage as actually written says

something quite different, that the

purpose of the statute is to "recognize"

that income is available to a family as a

whole if its members meet two distinct

requirements, i.e., they both "live

together" and "share expenses." It is

difficult to read into this sentence an

intent to count income as "available" to

an entire family if its members do "live

11 The Solicitor also argues that the record in this case demonstrates that

child support is generally diverted to

AFDC recipients. (U.S. Br. 41 n. 14) . The district court, however, found that

the testimony relied on by the government

showed that such diversions occurred, at most, in moments of "financial crisis." (N.C.J.S. A-64).

53

together" but do not "share expenses."

Although the Solicitor also refers to

several staff reports to the Senate

Finance Committee, and to a letter from

the Secretary of HHS to the Vice-

President, neither type of document

carries significant weight in

ascertaining the intent of members of

Congress itself. The Solicitor does not

actually assert, for example, that

Secretary Heckler's typewritten letter

was actually read or relied on by members

of Congress, or that it was ever referred

to or quoted in the legislative history.

Compare Teamsters v. United States. 431

U.S. 324, 351 (1977) (Justice Department

statement placed in Congessional Record

by floor managers of bill; See Watkins v.

Blinzinqer. 789 F. 2d 474, 479 (7th Cir.

1986) (" [T]he words of the staff are not

the equivalent of statements in committee

reports").

54

On this reading section 602(a)(38)

would mandate the state to inquire into

the manner in which AFDC parents are

utilizing child support funds. To

understand the significance of such a

statutory requirements it is necessary to

refer to the terms of the original 1971

decree in Gilliard v. Craig. Paragraph 3

of that injunction forbad state officials

from crediting to AFDC recipients the

income of others in the household

"without first detrmining that such

income is legally available to" the AFDC

recipients. (N.C.J.S. A-110). Under the

terms of the decree the critical issue

was whether the income in question was

"legally available" to the AFDC

recipients, not whether it was available

in fact. The language of the injunction,

if read literally, appeared to preclude

reducing an AFDC grant because a non-AFDC

child in the home was receiving child

55

support that was not "legally available"

to others in the household, regardless of

how the funds were actually being spent.

The 1971 opinion held that North Carolina

could not, in calculating the AFDC budget

of an applicant, consider the resources

of a non-applicant whose income exceeded

his or her standard of need, reasoning

that such a non-applicant had to be

disregarded because he or she had too

great an income to be eligible for AFDC.

The opinion made an exception for cases

in which there was "parental consent" to

inclusion of those resources but made no

provision for non-applicants whose income

was in fact being shared with actual AFDC

applicants. (N.C.J.S. A-98).

This Court's 1972 decision affirming

the opinion and order in Craig v.

Gilliard. 409 U.S. 807, made the

principles thus upheld binding throughout

the country. Edelman v. Jordan 415 U.S.

56

651 (1974). Although the precise legal

significance of that summary affirmance

might have been fairly debatable, North

Carolina, like other states, evidently

proceeded on the assumption that child

support, since not "legally available" to

anyone else in the household, could not

be considered no matter how it was

actually spent. Between the issuance of

the 1971 injunction and the 1984

implementation of the HHS regulations,

North Carolina simply made no effort to

ascertain how child support funds of non

recipients were in fact being used.

This was not, as in Lvnq. a case in which

inquiries into family practices proved

futile, but, rather, a situation in which

such inquiries simply were not attempted.

Section 602(a)(38) could fairly be

construed to forbid this practice of

disregarding whether support funds were

in fact being diverted to AFDC

57

recipients. On this reading the statute

would direct the states at the least to

subject child support payments to the

same, often exacting scrutiny applied to

other funds in the possession of the AFDC

parent, requiring the parent to provide

periodic reports regarding the manner in

which those payments were being

disbursed, and insisting on verification

of an applicant's representations. A

state which had reason to doubt the

accuracy of those reports would have to

invoke the same procedures available for

resolving any dispute about the

availability of income to an AFDC

recipient. If an applicant or recipient

failed to provide a state with relevant

requested information regarding the

disposition of support funds in her

possession, the state could undoubtedly

make an appropriate reduction in her

grant.

58

The language of section 602(a)(38),

as we suggested earlier, could plausibly

be read either to mandate such inquiries

and reductions or to require an economy

of scale adjustment in the grants of AFDC

applicants living with non-AFDC siblings.

Under these circumstances, we believe

that HHS should be accorded the

discretion to decide which method to use

in implementing section 602(a)(38).

(6) Section 602 (a) (38), as the

Solicitor construes it, would if

constitutional override state law in a

variety of ways. In North Carolina, as

is true throughout the nation, state

domestic relations law requires that

support payments be spent "for the

benefit of" the supported child, N.C.

Gen. Stat. § 50-13.4(d), but section

602 (a) (38), in the governments view,

requires that about one third to one-

half of those funds be spent to acquire

59

AFDC benefit for the child's parent and

siblings. North Carolina law directs

that the support payment be set by the

state court at a level sufficient to meet

"the reasonable needs of the child," N.C.

Gen. Stat. § 50-13.4 (b), but

§602 (a) (38), as the Solicitor reads it,

directs that the supported child actually

receive only a fraction of the funds

judicially determined to be necessary to

meet those needs. The inescapable effect

of the disputed HHS regulations is to

strip state judges of the power to direct

an award of child support to a child who

happens to reside with siblings on AFDC;

in such a case the child support will, as

a practical matter, have to be shared

with the siblings and custodial parent on

AFDC, despite the contrary intent and

direction of the state court which

ordered that payment, and despite the

terms of the North Carolina statute

60

authorizing child support orders. See

Br. of Amicus Curiae of National Council

of Juvenile and Family Court Judges.

Congress, we believe, has no

authority to override state law in this

manner. Nothing in the powers

enumerated by Article I confers upon

Congress the ability to adopt a general

domestic relations law applicable to the

population at large. "Nor as a general

proposition is the United States, as

opposed to the several states, possessed

of residual authority that enables it to

'define' property in the first instance."

Prunevard Shopping Center v. Robins. 447

U.S. 74 , 84 (1980). The detailed

provisions of the Social Security Act are

an exercise of congressional power under

the Spending Clause; Congress undeniably

has the ability to impose on willing

participants in federal programs

obligations which could not be extended

61

to the public at large. A requirement

that supported children who want to

receive AFDC assign their support

payments to the government, to the extent

that it might displace state domestic

relations law, falls within the authority

of Congress under the spending power.

Cf. Hiscruierdo v. Hisquierdo. 439 U.S.

572 (1979). But where, as here, state

domestic relations law governs the

property rights of a child who neither

wants nor needs federal assistance, it is

difficult to see how the Spending Power

could provide the Congress with any

authority to displace those state rules.

This Court has repeatedly held that

"[t]he whole subject of the domestic

relations of husband and wife, parent and

child, belongs to the laws of the States

and not to the laws of the United

States." In re Burrus. 136 U.S. 586,

593-94 (1890). Federal statutes have

62

been construed to pre-empt state law in

this area only if Congress has

"positively required" the pre-emption of

state law "by direct enactment." Wetmore

v, Markoe. 196 U.S. 68, 77 (1904).

" [ P] re-emption is not to be lightly

presumed." California Federal S. & T,.

Assn. Guerra, 93 L.Ed.2d 613, 623

(1986). State law will prevail in the

absence of a "clear and manifest purpose"

by Congress to override that state

provision. Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v.

State Energy Resources Comm'n. 461 U.S.

190, 206 (1983). Nothing in the

legislative history of section 602(a)(38)

indicates any intent to override state

domestic relations law, or any

understanding that the proposed

legislation might have such an impact.

That history and the language of the

statute suggest, at most, a desire to

recognize misuse of support funds if and

63

when and when it actually occurred, not

an attempt by Congress to require such

violations of state domestic relations

law.

Where a statute such as 602(a) (38)

reasonably lends itself to two or more

different interpretations, the law should

be construed in a manner that avoids

serious constitutional questions. We

urge, for the reasons set out at length

below, that the Solicitor's proposed

interpretation of section 602 (a) (38)

would render it unconstitutional. The

interpretation of the statute which we

propose, on the other hand, would avoid

those constitutional problems. If, as we

urge, section 602(a)(38) is susceptible

of a constitutional interpretation, such

a construction would avoid the

administrative problems that would arise

if the statute were struck down and

64

Congress were required to enact a

constitutional substitute.

11. THE APPELLANTS' PRACTICES WORK AN

UNCONSTITUTIONAL TAKING OF PRIVATEPROPERTY

T h i s c a s e turns on the

interrelationship of two distinct and

longstanding legal principles. This

Court has repeatedly held, as the

Solicitor General correctly observes,

that the formula for allocating social

welfare benefits ordinarily need meet

only a rational basis test. Lvnq

v.Castillo. 91 L.Ed.2d 527 (1986). This

Court has also insisted, however, most

recently in Hobbie v. Unemployment

Appeals Commission (No. 85-993, slip

opinion February 25, 1987), that the

government cannot, in providing such

benefits, establish conditions which are

themselves unconstitutional, or impose

substantial and direct burdens on

constitutionally protected activities.

65

Where, as in Hobbie. a social welfare

program is operated in a manner which

imposes such an unconstitutional

condition, that restriction must be

struck down, even though it might

otherwise meet the minimal rational basis

requirement of Lvna. Hobbie. slip

opinion p. 5. The disposition of the

instant appeal turns largely on whether

the practices at issue merely reflect a

reasonable attempt, as in Lvna. to

ascertain the needs of benefit

recipients, or whether those practices,

as occurred in Hobbie. effectively

condition the distribution of those

benefits on the abandonment or violation

of a substantive constitutional right.

A. Child Support Funds Are Protected bv the Taking Clause

In North Carolina, as throughout the

nation, child support funds are the

private property of the supported child.

North Carolina statutes provide that

66

child support payments are to be paid to

the custodial parent "for the benefit of

such child." N.C.Gen. Stat. § 50-

13.4(d). In litigated support

proceedings, the amount of the payment is

carefully calibrated to meet the

particular needs of the supported child,

"including his or her health, education,

and maintenance." N.C.Gen. Stat. § 50-

13.4(c). Although support payments are

ordinarily made to the adult who is the

custodial parent, that parent

is not the beneficiary of the moneys . . . These monies belong

to the children. [The

custodial parent] is a mere

trustee for them.... She

cannot ... profit at the

expense of the children.

Goodyear v. Goodyear, 257 N.C. 374, 379,

126 S.E.2d 113, 117 (1962). "It is a

violation of a court order for a

custodial parent to spend the child

support on other children not designated

in the child support order." (N.C.J.S.

67

A—43 to A-44, quoting affidavit of state

court judge).12 The federal Internal

Revenue Code does not treat child support

payments as income to the custodial

parent, since that parent may use the

funds only to meet the needs of the

designated child, and cannot "spend the

monies ... as she sees fit" for herself

or third parties. Commissioner v.

See also Scott v. Commonwealth

of Pennsylvania. 46 Pa. Cmnwlth. 403, 406

A.2d 594, 596 (1979) (child support funds

"belong to that [designated] child and not to other children or the mother);

Ditmar v. Ditmar. 48 Wash. 2d 373, 374,

293 P. 2d 759, 760 (1956) ("a mother hasno personal interest in child-support

money and holds it only as a trustee") ,* Watts v. Watts. 240 Iowa 384, 391,36

N.W.2d 347, 351 (1949) (child support

payments "not the property of the

[mother]. She was merely the custodian

of the funds ...;" Rand v. Rand. 40 Md.

App. 550, 392 A.2d 1149, 152 (1978)

(child support funds must "be applied

exclusively to the ascertained needs of

the child ... not to any extraneous

purposes"). Bourque v. Commissioner of

Welfare. 6 Conn. Cir. 685, 308 A.2d 543,

546 (1972) (fact that support payments

are made to mother does "not alter the

fact that the benefits were for the use

of the child.").

68

Lester. 366 U.S. 299 (1961).

The Solicitor appears to base his

brief on the premise that the child for

whom support payments are made has "no

... property right" "to ... prohibi[t]

the mother from spending the money on

anyone other than the designated child."

U.S.Br. 33). If the Solilcitor or the

Attorney General of North Carolina are

suggesting that a custodial parent could

legally use support funds intended for

one child to purchase clothes for the

child's brother, pay bus fares for the

child's sister, or buy presents for a

friend, they are plainly mistaken.

The effect on child support payments

of the HHS regulations can readily be

illustrated by a simple example. Under

the 1984 benefit schedule, a mother such

as Dianne Thomas with one child on AFDC

would receive a monthly AFDC grant of

$194. If the mother gave birth to or

69

acquired custody of a second child, and

received support payments of $200 per

month for that child, the mother would be

required, on pain of forfeiture of her

AFDC benefits, to assign the child

support payments to the state, and to put

the second child on AFDC. In return for

this $2 00 which the state received each

month, state officials would pass onto

the mother the first $50 of that support

payment, and provide an additional AFDC

allotment of $29, for a total of $79.13

The difference of $121 would be retained

by the state as a net profit from the

transaction. No matter how large the

Depending on the number of

children who were previously receiving

AFDC, the additional grant for the new child could be as little as $13. (J.App. 52) .

The Solicitor General also suggests that by applying for AFDC, the supported

child also receives Medicaid. (U.S. Br.

39). Medicaid is available in North

Carolina, albeit on somewhat different

terms, to children not receiving AFDC.

70

child support payment which is received

by the state in a given month on behalf

of a supported child, the state will not

provide for the child in return more than