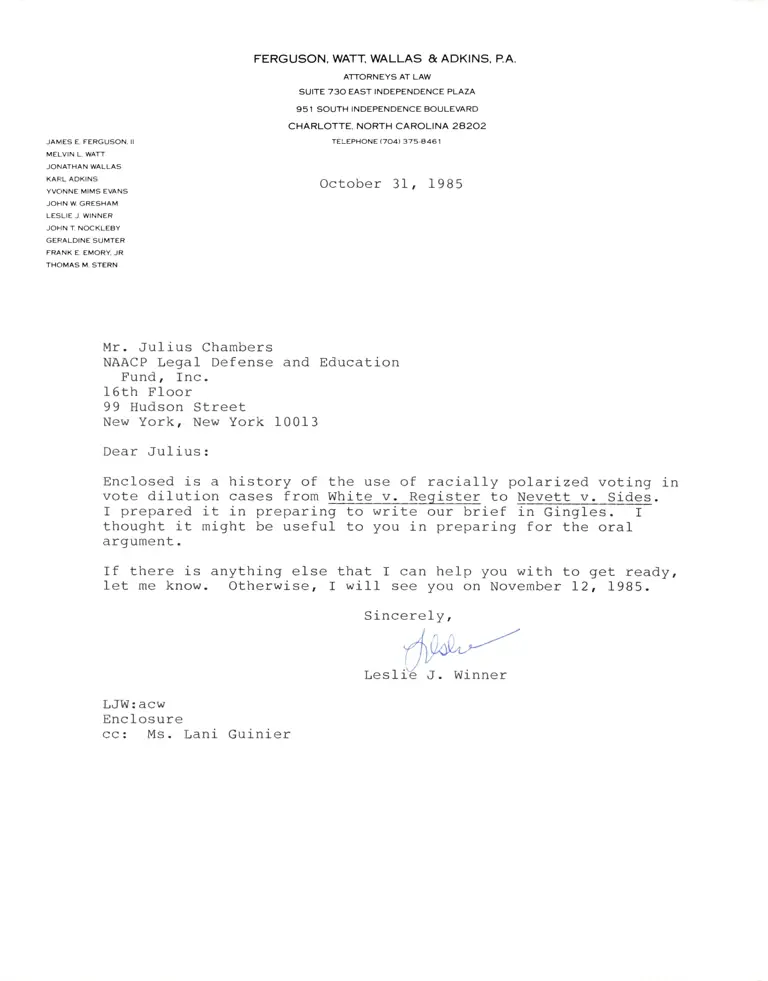

Correspondence from Winner to Chambers; From White to Nevett II - Court of Appeals Cases Which Talk About Racially Polarized Voting Research Paper

Correspondence

October 31, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Correspondence from Winner to Chambers; From White to Nevett II - Court of Appeals Cases Which Talk About Racially Polarized Voting Research Paper, 1985. 37a58b6b-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e69fd34d-1ee5-4395-b2dd-000a9453e18f/correspondence-from-winner-to-chambers-from-white-to-nevett-ii-court-of-appeals-cases-which-talk-about-racially-polarized-voting-research-paper. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

FERGUSON, WATI WALLAS & ADKINS, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 73O EAST INDEPENDENCE PLAZA

95 1 SOUTH INDEPENOENCE BOULEVARD

CHARLOTTE. NORTH CAROLINA 28202

TELEPHONE (704) 375,846tJAMES E. FERGUSON. II

MELVIN L. WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL ADKINS

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W, GRESHAM

LESLIE J. WINNER

JOHN T. NOCKLEBY

GERALDINE SUMTER

FRANK E, EMORY JR,

THOMAS M, STERN

October 31, 1985

Mr. JuIius Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense and Education

Fundr Inc.

I6th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New Yorkr New York 10013

Dear Ju1ius:

Enclosed is a history of the use of racially polarized voting in

vote dilution cases from Whrte v. neqister to Nevett v. Sides.

r prepared it in preparin@ier @

thought it might be useful to you in preparing for the oral

argument.

If there is anything else that f can help you with to get ready,

let me know. Otherwise, I will see you on November LZr 1985.

Sincerely r

LesIi"e

LJW: acw

Enclosure

cc: Ms. Lani Guinier

From White to Nevqtt fI - Court of Appeals Cases

wtrlEtr talk About Racially Polarized Voting

1. It is notable that there is not a word about polarized

voting in Zimmer v. McKeithen. The first case that mentions

racially polarized voting is Wallace v. House, 5I5 F.2d 6L9,622

(5tfr Cir. f975). It does not discuss how racially polarized

voting was determined but says, "they apparently voted right

down the line for racial solidarity, with whites voting for

whites and blacks voting for b1acks." The lower court (finding

#130) found "the record documents a history of bloc voting along

racial lines" such that "virtually all" whites vote for whites

and blacks vote for blacks. 377 F.Supp. L92, LL97 (L974).

There is no discussion of how it was proved. It was in the

context of only one black having ever won an election (which the

court found was a "mere stroke of luck" ). There was no

discussion of the importance of racially polarized voting, but

it was used to explain why the white candidates won.

2. In Perry v. City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th Cir.

1975 ), a decision mostly about the appropriate remedy, the court

discusses racially polarized voting in the course of discussing

unresponsiveness: "IT]he aII at large election plan has combined

with racially polarized voting patterns to produce aIl-white

Boards of Aldermen which have been able to ignore the interests

of their black constituents." Id. at 640. That is, since

whites had only a slight edge in voter registration, the

racially polarized voting was used to explain why white

candidates could ignore black concerns. There had never been

blacks elected. Bases finding of dilution on history of racial

discrimination, anti-single shot and majority vote reguirements,

and racially polarized voting patterns combined with a white

voting majority. There is no finding of intent and no

discussion of how racially polarized voting hras proved. The

district court findings are unreported. (375 F.Supp. 11 is

District Court remedy order).

3. In Nevett I,533 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir. L976), the Court

of Appeals vacates the District Court's finding of dilution.

Blacks were 50t of the registered voters and had won 6 out of 13

seats in 1968. They lost all in L972 due to the failure of

blacks to turn out combined with "substantial bloc voting. " The

appendix does not say how this vvas determined. The Court of

Appeals suggested the District Court thought blacks had to be

guaranteed electoral success and remanded for reconsideration in

accordance with Zimmer

4. In McGill v. Gadsden Co. Commissioners, 535 F.2d 277

(5th Cir. 1976), the Court affirms the District Court's

determination of no dilution since blacks were over l/Z the

democratic registered voters. The Court of Appeals mentions

that the District Court found racially polarized voting in

context in which blacks had never been elected, but the Court of

Appeals does not discuss the effect of this or how racially

polarized voting was determined. ( r do not believe the lower

court decision is reported.) [S.540 F.2d 1084,1085]

5. In Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d 1265 (5th Cir. 1977),

the Court vacated the District Courtrs order in favor of

2-

plaintiffs and remanded for more complete findings. In passing

the court notes that the great disparity in registration, the

racially polarized voting and the fact that no blacks have been

elected support the finding that the system suffers from

lingering effects of previous racial discrimination. Id. at

L270. There is no discussion of the extent or method of

determining racial polarized voting and the District Court

decision is not published.

6. In Kirksey v. Board gf Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139 (5th

Cir. L977) (en banc), cert denied 434 U.S. 968 (L977), the court

reversed a District Court finding of no dilution. The Court

holds that a redistricting plan is constitutionally

inpermissible if it perpetuates past purposeful denial of access

to the political process. Id. at L42, 146-8. In its list of

facts which lead to its conclusion of perpetuation of lack of

access and "Iess opportunity" are that no blacks had been

elected and "alleged bloc voting. " The District Court , 402

F.Supp at 672 n.4, bases its conclusion of racially polarized

voting on high correlation coefficients (+.979 and +.957).

7. fn ParneII v. Rapides Parish School Board, 553 F.2d 180

(5th Cir. L977), the Court considers "the probability of racial

bloc voting" in assessing the Zimmer factors and affirms the

Iower court finding of dilution. The court states that in the

context of racially polarized voting here blacks are

consistently defeated in the multimember districts. Id. at 184.

The Iower court had used a Pearson correlation and retrogression

analysis to conclude "there was a 98t probability of bloc voting

3-

along racial lines" although some whites did vote for black

candidates. I assume that the 9BE was the correlation

coefficient or the statistical probability, not the percent of

whites who voted for the white candidate, but that is not clear

from the decision.

B. The Fifth Circuitrs first meaningful discussion of

racially polarized voting is in Nevett v. Sides , 57 I F.2d 209

(5th Cir. 1978) (Nevett II) in which the Court holds that

plaintiffs must prove discriminatory intent to prevail and that

the purpose of examining the Zlmmer factors is to determine

whether they raise a inference of discriminatory intent. Id. at

217. ( "When the more blatent obstacles to black access are

struck down, such an at-large plan may operate to devalue black

participation so as to alIow representatives to ignore black

needs. Where the plan is maintained with the purpose of

excluding minority input, the necessary intent is

established. . . " Id. at 222. )

It is in the context of determining if the method is

being maintained for the purpose of allowing the elected

officials to be unresponsive that Court discusses racially

polarj.zed voting. Noting that polarized voting aIIows

representatives to ignore minority interests with impunity the

Court states, "When bloc voting has been demonstrated, a showing

under Zimmer that the governing body is unresponsive to minority

needs is strong corrborative of an intentional exploitation of

the electorates bias. "

4-

As a footnote, the Court uses the often cited language,

"II]n the absence of polarized voting, black candidates could

not be denied office because they were black, and a case of

unconstitutional dilution could not be made. "

Note 18 discusses how bloc voting can be indicated. ft

states it can be indicated by showing the Zimmer factors (?), by

statistical analysis as in Bolden v. Mobile, 423 F.Supp. 384,

388-89, or by the "consistent lack of success of gualified black

candidates. I' The method used in Bolden was regression used to

establish correlation. In Bolden the Court finds, "There is no

reasonable expectation that a black candidate could be elected

in a citywide election race because of race polarization. " Id.

at 389.

Thus racially polarized voting was not mentioned at aII

in Zimmer, it was noted in some but not all cases from Wallace

v. House through Kirksev, although either without any statement

of importance or as an explanation of why blacks were not

getting elected. There was no discussion in any of these cases

about the extent of racially polarized voting necessary for it

to be significant, and no statistic used except correlation

coefficient. The first discussion was in Nevett If which

discussed racially polarized voting in its discussion of why the

Zimmer factors raise an inference of intentionat$-,maintenance ofv

a system which allows white politicians to be unresponsive.

That is, if there r^rere not enough polarized voting to assure

consistent black defeat, whites would not be able to be totally

tr

J_

unresponsive. This reasoning is not applicable to 52 which

focuses on neither purpose or unresponsiveness.

Of the cases cited by Parker from other circuits, three

do not mention polarized voting. fn pove v. Moore, 539 F.2d

1152 (Bth Cir. L976'), the Court uses an extreme case analysis in

two elections and concludes that "blacks and whites alike have

,'-lrejected" race as the overriding critefi*o/i" voting for

\/

candidates. (A black candidate got 44.5t of white vote in white

ward, a white card got 44* of black vote in black pct). The

court concludes that blacks have fuII and egual access to the

city's political process emphasizing the need of white

candidates to campaign in black areas to get elected.

6-