Response To Defendant-Intervenors Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment

Public Court Documents

February 22, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Response To Defendant-Intervenors Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, 1983. 80dfce2c-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e7025012-5bcd-47df-ab54-3c4140e17560/response-to-defendant-intervenors-cross-motion-for-summary-judgment. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

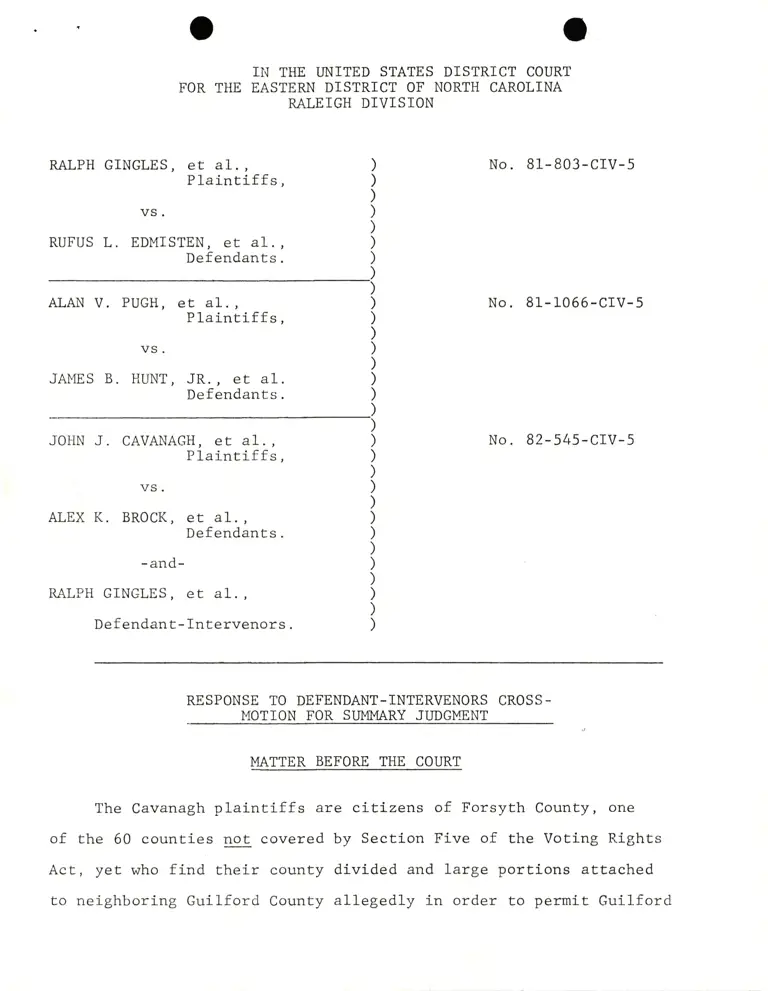

II{ THE I]N]TED STATES

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF

RALEIGH DIVISION

DISTRICT COURT

NORTH CAROLINA

MLPH GINGLES, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, €t 41.,

Defendants.

AIAN V. PUGH, €t dL.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., et al.

Defendants.

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, €t aL.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

ALEX K. BROCK, €t 41.,

Defendants.

-and-

RALPH GINGLES, et &1.,

Def endan t - Intervenors .

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

No. 81-803-CIV-5

No. 81-1056-CIV-5

No. 82-545-CIV-5

RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS CROSS.

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

MATTER BEFORE THE COURT

The Cavanagh plaintiffs are citizens of Forsyth County, one

of the 60 counties not covered by Section Five of the Voting Rights

Act, yet \^rho f ind their county divided and large portions attached

to neighboring Guilford County allegedly in order to permit Guilford

to comply with the Voting Rights Act.

Plaintiffs show that this division of their county clearly

violaEes the provisions of Article Ir, Section 3(3) and Section

5(3) of the North Carolina Constitution.

This case appears to be one of first instance wherein the

question arises, "mry the ambit of the voting Rights Act Section

Five Preclearance requirements be so construed as to extend the

effect of that section to political subdivisions which the Congress

excluded from its provisions?"

cross-motions for summary judgment have now been filed by

the plaintiffs, the original defendants and the defendant-inter-

venors. This memorandum responds to that filed on February I by

de f endant - intervenors .

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Defendant-intervenors list (on page 3 of their memorandurn)

five contentions: first, that this court has no jurisdiction to

review the Attorney General's objection to Article II, Section 3(3)

and Section 5(3) of the North Carolina Constitution; second, that his

decision that those North Carolina constitutional provisions re-

quired preclearance is correct; third, that the apprication of

Section Five of the Voting Rights Act to onry the 40 counties

designated by Congress, and not to the remaining 60 counties ex-

cluded by congress, amounts to a denial of equal protection to

the 60; fourth, that the North Carolina constitutional.provisions

-2

cannot be so "severed" as to be enforceable in 60 counties, while

not in the 40 remaining counties; and fifth, that the Supremacy

Clause makes the division of Forsyth County necessary.

The Supremacy Clause contention is not argued in defendant-

intervenors memorandum and will therefore not be addressed here.

Nor will their contentions that the unbroken 3L7 year North

Carolina rule of not breaking county lines somehow required pre-

clearance; that issue has been belabored to the point of tedium

in the briefing of all parties. The history is a matter of record

and we will not presume to recite it again here.

But three of defendant-intervenors contentions do deserve

response, and they wilI be addressed, hopefully succinctly, in

the following order:

I. The extent of this court's jurisdiction,

II. The equal protection question,

III. The severability of the relevant North

Carolina constitutional provision as

between the 40 Voting Rights Act and

the 60 non-Voting Rights Act counties.

This court has jurisdiction to determine whether

FoEsyth County (and the other 59 North Carolina

Counties similarlv situated) is covered under

Section Five of the Voting Rights Act and there-

fore sub.iect to the Attornev General's determina-

tion

I

-3

Defendant-intervenor spends much time arguing that this court

does not have jurisdiction Lo review the Attorney General's deter-

minaEion that the adoption of Article II, Section 3(3) and Section

5(3) by the people of North Carolina as amendments to their Consti-

tution, required preclearance.

Conceding this point for the purpose of discussion, plaintiffs

would point out that the cases nevertheless seem to uniformly hold

that, while Congress expressly reserved such questions as discrimina-

tory purpose or effect to the Attorney General or the District Court

of the DistricE of Columbia, (Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393

U.S. 544, 89 S. Ct. 8L7, 22 L.Ed. 2d. L (f969); Perkins v. Matthews,

400 U.S. 379, 91 S. Ct. 43L, 27 L.Ed. 2d. 476 (L97L); Rome v. U.S.,

450 Ir. Supp. 37 B(D), D.C. 1978); affd. 446 U.S. L56, 100 S. Ct. 1548,

64 L.Ed. 2d. LLg, Reh. den. 447 U.S. 9L6, 100 S. Ct. 3003, 64 L.Ed. 2d.

865 (1980) ) local three judge courts are properly vested with jur-

isdiction to determine whether a given voting requirement is covered

by Section Five. Perkins v. Matthews, supra.

And, of course, coverage is the very question at bar in this

cause.

Thus, in Clayton v. North Carolina Board of Elections, 3L7 F.

Supp. 915 (EDNC 1970) the North Carolina General Assembly in L969

passed an elections law which applied only to 6 of North Carolina's

100 counties, and which required electioneering to be kept more than

500 feet from the polls. Four of the 6 counties were subject to the

Voting Rights Act. The District Court did not hesitate to decide

the coverage question: "[rIith respect to the 4 counties covered by

the Act...we conclude that Chapter 1039 is unenforceable because of

a failure to comply vrith Section Five of the Act." (P. 9L7).

Later the court added in deciding that it could consider the

application of the Act to non-Voting Rights Act counties under

the doctrine of pendant jurisdiction, "However, with respect to

the 4 counties to which the Voting RighLs Act applies, Section

Five of that Act clearly vests jurisdiction in a three judge court."

(P. 920, emphasis supplied) .

Again in , 3LT F.

Supp . L299 (EDNC 1970), considering a rotation agreement among coun-

ties in a senatorial district, one of which counties was a Voting

Rights Act county, the court concluded as Eo its jurisdiction,

". .the specific grants of jurisdiction to the District Courts in

Section T2(t) indicates Congress intended to treat 'coverage' ques-

tions differently from'substantive discrimination' questions."

Finally, in Dgnqqarr_v. Scott, 336 F. Supp . 206 (EDNC L972)

which involved both "numbered seat" and "anti-single shot" election

1aws, a three judge courL was properly convened in a Voting Rights

Act case, although the court ultimately held the questioned laws

unconstj-tutional as against the equal protection clause both in the

Voting Rights and non-Voting Act counties.

So it seems clear that this court has jurisdiction to determine

whether the effective coverage of the Voting Rights Act in North

Carolina can be extended beyond the 40 counties explictly listed

as being subject to its constraints.

-5

II

The Equal Protection clause of the l4th

Amendment does not require identical treat-

ment of the 40 covered counties and the 60

non-covered counties.

Plaintiffs contend thaE the operation of the North Carolina

Constitutional prohibition against division of counties in defin-

ing legislative districts has been suspended on1-y in the 40 counties

under the Voting Rights Act, because of the objections of the

Attorney General. In the 60 other counties - not covered by the

Voting Rights Act nor subj ect to Attorney General preclearance

the North Carolina Constitutional provision remains in effect. It

is this potential differentiation of treatment which the defendant-

intervenors contend is violative of Equal Protection.

It should be remembered that, normally, it is only the invidious

discrimination, the wholly arbitrary act, which cannot stand consis-

tently with the 14th Amendment, and that a presumption is made in

favor of the Iegislative or constitutional classification. See

164 Am. Jur. 2d. Constit. Law, S 749. The ordinary test imposed

is whether a law is rationally suited to achieve a lawful objective

of the state. I4cGowan v. Marvland, 366 U.S. 420, 81 S. Ct. "110I,

6 L.Ed. 2d. 393 (1951) .

And, of course, in the case at bar, the question is whether the

North Carolina Constitutional provision prohibiting division of

county lines is rationally suited to achieve a lawful objective of

the state. That question has been answered affirmatively in

-6

Mahan v. Howell , 4L0 U.S. 315, 93 S. Cr. 979, 35 L. Ed. 2d. 320

(L973), where respect for Iocal political subdivisions is

(P. 329); NAACP v. Riley, 533

366 F.S. 924 (MD Ala. L972).

held

F. S. 1178"a rational

(DSC L982);

state policy"

Sims v. Amos,

INeedless to sdy, the preservation of county

lines while a rational objective of state

policy, must nevertheless bow should it con-

flict with the overriding federal policy of

one man/one vote. But such a conflict does

not exist here, since it has been demonstrated

Ehat the state can be satisfactorily redis-

tricted within those constraints. Michalec,

deposiLion and affidavitl .

The defendant-intervenors, however, contend that rather than

this court applying the "rational objective" test to the constitu-

tonal provision, a "strict scrutiny" standard should be applied

because the preservation of county lines in some counties, while

they are split in others, "affects the fundamental right to vote."

(Memorandum, defendant-intervenor, P. 2L). They do not pursue

this argument to the point of stating precisely how the differen-

tiation affects the right to vote, but we can surmise that this is

because in the 60 counties whose integrity would be preserved under

the North Carolina Constitution, 8t large voting and multi'member

districts might tend to "dilute" an elector's vote, while in frag-

mented counties under the Voting Rights Act, such might occur.

Suffice to say, the courts have not agreed with defendant-

intervenors that possible dilution is such a fundamental right as

to require "strict scrutiny. r' Rather they have asked only if the

law questioned rationally furthers a legitimate state purpose or

interesE. The maEter is encapsulated in an annotation on dilution

-7

of l,linority Votes, in 27 ALR Fed. 29 (L976) at P. 50:

"Thus the degree of constitutional inquiry

which is applied in vote-dilution cases de-

pends on whether courts regard the right of

'voting equity'...as a 'fundamental' right

or not. Unlike the right to an equal vote,

the right to an equitable vote is apparently

not considered 'fundamental', for the courts

in the following cases have held or recog-

nized that an election plan or districting

scheme is entitled to a presumption of

consEitutional validity, and that there-

fore the 'stricter scrutiny' test will not

be applie

challenged on dilution grounds under the

14th Amendment. " (Cases cited. Emphasis

suppfied) I .

I^le have thus far seerr that the preservation of county integrity

is a rational state policy and can stand equal protection examination.

The other aspect of the question is whether the differentiation of

treatment in the 40 covered counties is reasonable. Defendant-

intervenors contend (P. 22) "it is hard to justify the differentiation

between counties". The identical argument was made by South Carolina

in South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 86 S. Ct. 803, 15 L.Ed.

2d.769 (1966) and the Supreme Court there held (P. 329)

"South Carolina contends that the coverage

formula is awkwardly designed in a number of

respects and that it disregards various local

conditions which have nothing to do with ra-

cial discrimination. These arguments, however,

are largely beside the point. Congress began

work with reliable evidence of actual voting

discrimination in a great majority of the

states and political subdivisions affected

by the new remedies of the Act. The formula

eventually evolved to describe these areas

was relevant to the problem of voting dis-

crimination, and Congress was therefore

-8

entitled to infer a significant danger of the

evil in the few remaining States and political

subdivisions covered by Section 4(b) of the Act.

No more was required to justify tl're application

to these areas of Congress's express power under

the 15th Amendment. " (Cases cited) .

So it would seem that the Congress in enacting the Voting

Rights Act, as well as the people of North Carolina who adopted

the Constitutional Amendments are entitled to some presumption of

rational purposel

It remains to consider the two North Carolina cases cited by

defendant-intervenors. Clayton v. Board of Elections, 3L7 F.S. 915

(EDNC L970) seems to support what plaintiffs have contended throughout.

The court bifurcates iUs deci-sion, declining to apply the Voting Rights

Act to non-Voting Rights Act counties, then having held the legisla-

tive enacEment "inoperable" in the Voting Rights Act counties because

of failure to preclear under Section Five, proceeds to anaLyze the

non-Voting Rights Act counties. The court begins by noting (P. 920)

"Not every discrimination or classification

denies equal protection, and classifications

made by state legislatures are presumptively

supported by valid state purposes...unequal

treatment constitutes a denial of equal pro-

tection only if the classification lacks a

'reasonable basis' and no state of facts

reasonably may be to concede Eo justify it...

but where fundanental rights and liberties

are asserted under the Equal Protection

clause, such as the right to vote, tclassi-

fications which might invade or restrain

them roust be closely scrutinized and care-

fully confined' . "

-9

The court'Ehen finds that there is simply no evidence whatsoever

to show why the 6 counties should be differently treated from the

remaining 94: no legislative history, Do argument or briefirg,

no evidence of disturbance. 0n that record, the court had no

choice but to find a denial of equal protection. 0f course, this

is not our case at all: here the reason for the differentiated

treatment lies in Congress's enactment of the Voting Rights Act,

anci in the formula therein approved expressly by the Supreme Court

in Katzenbach, supra.

support what plaintiffs

supra, the court found

336 F. Supp. 206 (EDNC L972) also seems to

have urged all along: here, too, 3s in Clayton,

(P. 2L3)

". . .The state has shown no justification or

even rationale for discriminating between

voters of covered and exempted areas. Such

an unexplained classification is inherently

suspect and fails even the ordinary test of

equal protection. "

Again, 3s in Clayton, the reason for the differing treatment in

the case at bar lies in the applicability of the Voting Rights

Act.

IPlaintiffs cannot forbear noting that in Dunston the State

urged that, after the U.S. Attorney General had declaied

the law unenforceable in Voting Rights Act counties, the

Iaw became "much more local" and beneath the dignity of

ttre three judge court. Judge Craven in disposing of that

argument, disposed simultaneously of defendant's principal

argument in the case aE bar to the effect that the Voting

Rights Act renders the North Carolina Constitutional pro-

visj-ons "void" in covered counties: "However, the action

Dunsto4 v. Scott,

of the Attorney General has not rendered the law void

in the counties covered by the Voting Rights Act of

L965, but rather temporarily unenforceable there. The

law can be rendered enforceable by the Attorney General's

withdrawal of objection or by a declaratory judgment by

Ehe District Court for the District of Columbia in accor-

dance with 42 USC, S L973C. In addition the law is sti11

enforceable in 5 Senate disEricts and 7 House of Repre-

sentative districts. "]

III

No question as to "severabilitv" arises in

this case. since no Law has been found un-

constitutional or invalid.

DefendanE-intervenors suggest that the statutory construction

rules of "severability" should be applied inasmuch as the people of

North Carolina obviously intended their constitutional prohibition

Eo apply in all 100 rather than a mere 60 counties.

And plainLiffs would agree that the people of ltrorth Carolina in

overwhelmingly approving the constitutional amendments continuing the

unbroken rule of county integrity, intended that salutary practice

to apply in all 100 counties. But to leap from this proposition

to the contention that, since it is not enforceable in 40 counties,

it should not be enforced in any counEies is lacking in logic. For

several reasons:

First: the Ehree cases cited by defendant-intervenors all

involved judicial declarations of total invaliditv of part of an

offending statute. The case at bar involves a temporary suspension

of enforceability - for a stated period of time Gz usc Lg73b) or

until the AtEorney General or the District Court of the District of

columbia sooner lift rhe suspension (42 usc 1973c). rn fine, the

North Carolina Const:'-tutional provision remains law in the 40 as

well as the 60 non-covered counties: as Circuit Judge Craven put

it in Dunston v. Scott (supra),

' ;;;ll3 u^:;:"1,;'":l; t:':il:"l"ffti:3' ":i:,::'by the Voting Ri-ghts Act of f965, but rather

temporarily unenforceable there. The law can

be rendered enforceable by the Atto?ney-Teneral's

r oi by a declaritory

judgment by the District Court for the District

of Columbia in accordance with 42 USC S 1973c.

In addition the law is still enforceable in 5

Senate districts and 7 House of Representative

districts. " (Emphasis supplied) .

Second: the defendant-intervenors'argument that the people of

North Carolina would surely not have enacted the Constitutional amend-

ment had they foreseen its partial suspension, is conjecture at best.

Should defendant-intervenors' guess be correct, however, the people of

North Carolina can amend their Constitution themselves (N.C. Constitu-

tion, Article XIII) and remove any doubt as to their preferences. Thus

far, they have not chosen to do so.

Third: even if it were suggested that the rules of severability

should apply, those who would invalidate the North Carolina Constitu-

tionarl provision statewide have a heavy burden: succinctly put,

"Courts will indulge every presumption in favor of constitutionality. "

Painter v. I^Iale, 2BB N.C. L65, 2L7 S.E. 2d. 650 (L975). Blasicki v.

Durham, 456 F. 2d. 87 (4th Cir. L972), cert. den. 409 U.S. 9L2. See

cases cited in original Memorandum of plaintiffs, P. 6. And "where

Ehe unconstitutional portions are stricken out, and that which remains

is complete in itself and capable of being executed in accordance

with the apparent legislative intent, it must be sustained." Lowerv v.

School Trustees, 140 N.C. 33, 52 S.E. 267 (f905) citing 26 Am. and Eng.

Enc. (2d.Ed.) 570.

That this strong presumption obtains in election law is seen

in Clark v. Mevland, 261 N.C. L40, L34 S.E. 2d. 168 (L964) involving

a requirement that a voter desiring to change his registration should

take an oath first thaE he wanted to change his party affiliation in

good faith, and second that he would support thaE party in future

elections. The good faith portion was permitted to stand while the

party loyalty clause in that same oath was stricken" It would seem

that application of the North Carolina rule of severability presents

a hard road indeed for defendant-intervenors.

CONCLUSION

This court has jurisdiction to determine that the Voting Rights

Act, beirrg inapplicable to Forsyth County, cannot provide legal

excuse for a violation of the explicit commands of the North Carolina

Constitution that Forsyth County's boundaries remain intact in re-

-13

districting: it's writ simply

for it by the Congress.

does not run beyond the bounds defined

This 22nd day of February, 1983.

Respectfully submitted,

Attorney for Plaintiffs in 82-rt#-CIV-5

450 NCNB PLaza

Inlinston-Salem, North Carolina 27LjL

(919) 723-L826

OF COUNSEL:

HORTON AND HENDRICK

450 NCNB PLaza

Winston-Salem, N.C. 27L0L

!{ayne T. EllioEE, Esq

SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDATIOItr, INC.

1800 Century Boulevard, Suite 950

Atlanta, Georgia 30345

(404) 325-22s5

-L4-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served the foregoing Response to

Defendant-Intervernors Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment on all

other parties by placing a copy thereof enclosed in a postage pre-

paid properly addressed wrapper in a post office or official de-

pository under the exclusive care and custody of the United States

Postal Service, addressed to:

I(aEhleen Heenan, Esq.

Jerris, Leonard & Associates', P.C.

suire 1020, 900 l"7rh srreet, N.w.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Arthur J. Donaldson,Esq.

Burke, Donaldson, Holshouse & Kenerly

309 N. Main Street

Salisbury, North Carolina 28L54

Robert N. Hunter, Jr., Esq.

Attorney at Law

Post Office Box 3245

Greensboro, N.C. 27402

James Wallace, Jt., Esq.

Deputy Attorney General for Legal Affairs

Attorney General's 0ffice

North Carolina Department of Justice

Raleigh, Itrorth Carolina 27602

J. Levonne Chambers, Esg., and

Les lie J . l'Ij-nner, Esq.

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, €t aI.

951 South Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Jack Greenberg, Esq. and

Lani Guinier, Esq.

Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Hamilton C. Horton, Jr.

Attorney for John J. Cavanagh,

et al

450 NCNB PLaza

Wins ton- Salem, [l . C . 27 L}L

(919) 723-L826