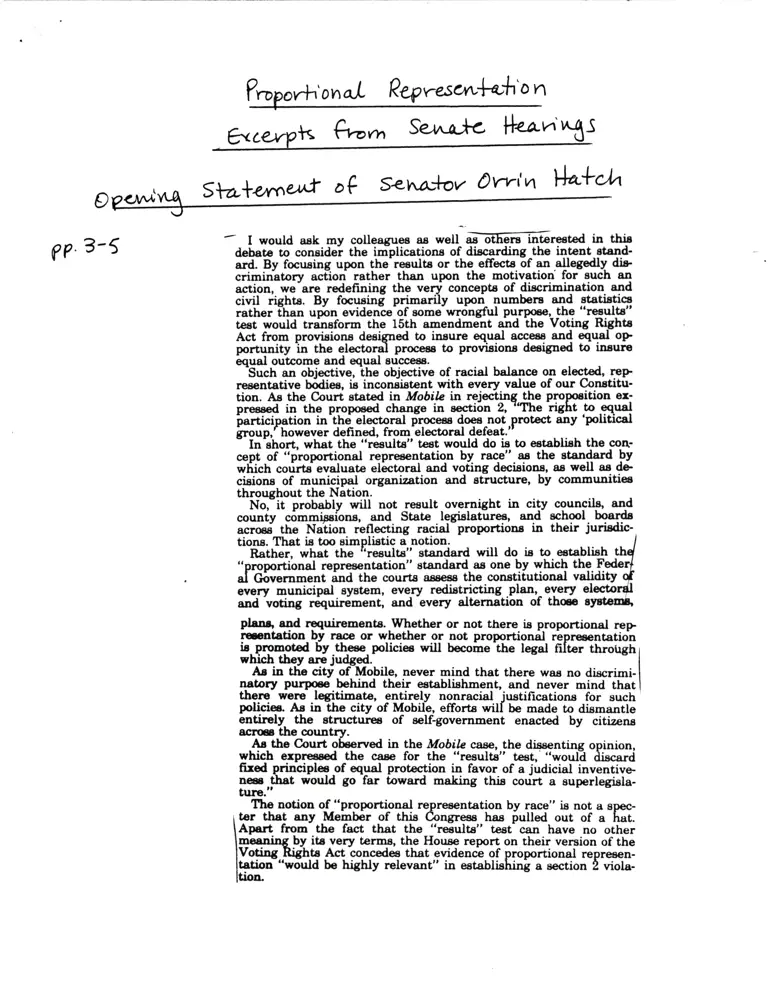

Excerpts from Senate Hearings: Proportional Representation (Opening Statement of Senator Orrin Hatch)

Unannotated Secondary Research

April 28, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Excerpts from Senate Hearings: Proportional Representation (Opening Statement of Senator Orrin Hatch), 1982. 2a671141-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e74afe50-006c-46e2-aa75-e9f6772619d3/excerpts-from-senate-hearings-proportional-representation-opening-statement-of-senator-orrin-hatch. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

Propovh‘onal. Represmi-d-u‘on

Etna/pk Ham SW6 Hem/{was

, samba 09 sewov own We“

ngvhg

Pp. 3‘5

I would ask my colleagues as well as others interested in this

debate to consider the implications of discarding the intent stand-

ard. By focusing upon the results or the effects of an allegedly dis-

criminatory action rather than upon the motivation for such an

action, we are redefining the very concepts of discrimination and

civil rights. By focusing primarily upon numbers and statistics

rather than upon evidence of some wrongful purpose, the “results"

test would transform the 15th amendment and the Voting Rights

Act from provisions designed to insure equal access and equal op-

portunity in the elector process to provisions designed to insure

equal outcome and equal success.

Such an objective, the objective of racial balance on elected, rep-

resentative bodies. is inconsistent with every value of our Constitu-

tion. As the Court stated in Mobile in rejecting the pro ition ex-

pressed in the proposed change in section 2, ‘The rig t to equal

participation in the electoral process does not protect any ‘political

group, however defined, from electoral defeat.’

In short, what the “results" test would do is to establish the con-

cept of “proportional representation by race” as the standard by

which courts evaluate electoral and voting decisions, as well as de-

cisions of municipal organization and structure, by communities

throughout the Nation.

No, it probably will not result overnight in city councils, and

county commissions. and State legislatures, and school boards

across the Nation reflecting racial proportions in their jurisdic-

tions. That is too simplistic a notion.

Rather, what the ‘results” standard will do is to establish th

“ roportional representation" standard as one by which the Feder

Government and the courts assess the constitutional validity

every municipal system. every redistricting plan, every electoral

and voting requirement, and every alternation of those systems,

plans, and requirements. Whether or not there is proportional rep-

resentation by race or whether or not proportional re resentation

1s promoted by these policies will become the legal f ter through

which they are judged.

As in the city of Mobile, never mind that there was no discrimi-

natory purposebehmd their establishment, and never mind that

there were legitimate, entirely nonracial 'ustifications for such

policies. As in the City of Mobile, efforts wil be made to dismantle

entirely the structures of self-government enacted by citizens

across the countrg'ée

5.“ the Court 0 rved in the Mobile case, the dissenting o inion.

which expressed the case for the “results” test, “would ' d

fixed princ1ples of equal protection in favor of a judicial inventive-

:iessnthat would go far toward making this court a superlegisla—

ure.

The notion of “proportional re resentation by race" is not a s -

ter that any Member of this ng'ress has pulled out of a at.

Apart from_the fact that the “results" test can have no other

In . by its very terms, the House report on their version of the

Voting‘ hts Act concedes that evidence of roportional re resen-

tstiotwn ‘would be highly relevant" in establis ' a section viola-

n.

Pnpovh'oml Pep- 9‘

In addition, we see many civil rights leaders stating rather ex-

Elicitly that roportional representation is their goal. Dr. Willie

ibson, presi ent of the South Carolina NAACP, for exam 1e, has

stated that, “Unless we see a redistricting plan in South arolina

that has the possibil‘fifi of blacks bein elected in proportion to

their po ulation, we ' push hard for ternative plans.

In ad ‘tion. the Supreme Court has been forthright in its charac-

terization of the “results" or “effects” standard as one designed to

promote pro rtional representation by race. To refer to the Mobile

case again, Court observed, “The theory of the dissenting opin-

ion appears to be that every political group, or at least every such

group that is in the minority, has a Federal constitutional right to

elect candidates in roportion to its numbers . . . the equal protec-

tion clause of the 4th amendment does not require proportional

re resentation as an imperative of political organization."

ore I conclude. let me make an observation about a so-called

disclaimer provision in section 2 that we will all be hearing a great

deal about during these h ' . This provision, it has been sug-

gested. disclaims the idea that k of proportional re resentation

constitutes a section 2 or 15th amendment violation. t is pure

and unadulterated “smokescreen.”

Rather, what the language following the “results" test in section

2 as is that lack of “ roportional representation" “in and of

i ' is not a violation. t then proceeds to describe merel a few

factors that, in conjunction with the absence of proportion repre-

sentation, will consummate a violation.

These factors include the existence of at-large electoral systems,

racial bloc voting. a history of discrimination, majority vote re-

uirements, prohibitions on single-shot votin , and numbered posts.

factors that have been su ested by t 0 civil rights commu-

ni or that have been used by e Justice Department in the past

' uds disparate racial registration figures, history of English-only

lballots, the maldistribution of services in racially definable neigh-

borhoods, staggered electoral terms, impediments to third party

voting, numbers of minority registration officials, “inconvenient’

registration hours, reregistration requirements, registration purg-

in requirements. et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, ad infinitum.

other words, given the lack of proportional representation,

any of these factors which the House report calls “objective" fac-

tors of discrimination will suffice to complete a Voting Rights Act

violation. Given the absence of proportional representation, virtual-

ly an jurisdiction in the country will be vulnerable to a section 2

suit. ndeed, the Court in Mobile rejected a similar attempt to dis-

claim the charge of proportional representation by calling it "illu-

sory” and restin upon “gauzy sociological considerations having

in CQMW- 4.

/

TeS‘i‘imOim/ 0i: EWJIQMCH Hoots

Q . 2 ’5 2. ‘ ‘5 3'

”Senator HATCH. You indicate that you know of no one in the civil

rights community that has advocated glroportional re resentation.

Permit me. if gou will, to quote from e Greenville, .C. “News,"

of December 1 , 1981, the remarks of Dr. Willie Gibson, whom I am

sure you know. He is the president, I believe, of the South Carolina

NAACP. He indicates his "opposition to a redistricting plan in

11

South Carolina by stating, ‘ ess 6 see a plan that has the pos-

sibility of blacks having thW-

up n to this Equation, we m d for a new p .

Can you exp am e subcommittee what Dr. Gibson is talkin

about here? It appears to me that he is talking about proportion

representation.

fro porb‘OV‘Ovl Pep 3

Mr. HOOKS. I understand precisely what Dr. Gibson is talking

about._ These are not unusual statements to be made. I think there

is a big difi'erence between proportional representation and repre-

sentation in proportion to t eir population. It simply means that-

we are not 100 for 00 e ints—if we have 42 percent,

we wan percen representation. ut i oes mean there must be

W—mt we would not be satisfied with a

p , or instance—

t‘ioSe?nator HATCH. Is that not a form of proportional representa-

n

Mr. Hooxs. If youaget to the nth degree, any representation is

somewhat proportion . It is a part of our Constitution. It is not ad-

hered to generally, but the whole business of redistricting was to

adhere to the concept of 250,000 members for a Congressperson, 2

for every State no matter what size for the Senate. It was set up

like that.

Ge mandering is somethin that has been in our language long

before lack folk got involved. hese are not new concepts.

If you understand what happens in South Carolina—that in the

State senate even today there is not a single black serving, unless

it hap ned in the last 3 months. We are involved in a lawsuit

there, ficause we do have blacks in the State house of representa-

tives, but not a single black has been elected to the senate because

of the we they do it.

What r. Gibson was dealing with was a precise situation where

somebody said, “There are 30 members of the senate; would you be

happy to settle for 1?” In that kind of rhetorical statement to a

people, the answer alwa s is, “Certainly not. We want something

that resembles our popu ation." That is a far different cry from a

mathematical proportional representation, which is the term that

is being used here over and over again.

In the human existence of our lives, if I were to go to any State

and was asked to put the NAACP seal of approval on a particular

plan, like a Democrat in Utah or a Republican in Cook County, I

would probably enter that very suspicious about what was happen-

ing. I would want to know, “Does it deal with equity?” And equity

does not mean exact mathematical proportions.

I know Dr. Gibson. He is the president of the NAACP Conference

for South Carolina. He knows NAACP licy. He would not know-

ingly violate it. That statement—and have heard him make it

many times—has to do with_ promrtions and not proportionate,

mathematical, precxse re resentationbased on population.

‘ Wu. To use your illustrafion, ii nof‘ZZ percent, what

percentage would you be satisfied with?

Mr. HOOKS. Senator, we have had to wrestle with that over and

over again, and new occasions teach new duties. Time makes an-

cient good uncouth. We have never been able to come up with any

precise definition.

Just like the standard of granting broadcast licenses, you must

serve the ublic interest, convenience, and necessity. No writer, not

the most earned professors like Willesden, have ever been able to

explain it. Like the Sn reme Court Justice said about pornography,

“I may not be able to efine it, but I know it when I see it.” Equity

to us is something we may not be able to define, but we know it

when we see it in a iven case.

Senator HATCH. I now proportional representation when I see it

too. I think anybody who looks at this knows it.

Let me just ask you this: Let us assume that I am right in my

belief that this bill will lead to proportional representation and this

bill passes. Of course if it has 62 firmly committed an porters;

there is no question it is going to pass. If it passes an it does

result in proportional representation, will you accept that?

Mr. HOOKS. I did not quite—

Senator HATCH. Let us say this bill passes in its present form

and it results in proportional representation. Would you be satis-

fied with that?

Propovi'ibml 25? ‘7"

Mr. Hooxs. I do not know how it would result in proportional

representation, unless you had a lawsuit that would declare that it

meant that. I am simply saying to you, sir, that we propose in the

future, as we have in the past, to monitor and look at the practices.

Remember, when we talk about proportional representation, we

seen: toIhaJe forgotten one ifhmgBal We talk babout tlgat Baltimorel ex-

am e. t not matter ' timore mes percent b a .

Jiftheyelecta is u o .

:v. :5: e "L th.t,

you can pinpOint tha

maie ha n.

e cause is the black folk in Baltimore happen to like that

white mayor and those white council people, that is not a cause for

justiciable arrangement of a grievance.

All I am saying is that I think we have forgotten what precedes

the language, and that is there must be a practice, there must be a

condition, and in my written testimony I have outlined about 30

things that happen. _

If you could prove that voting from midnight until 8 in the morn-

ing kept blacks from voting or putting the precincts in the police

department—there are all kinds of things—if you could not prove a

practice, a custom, or something that happened, you would not

ever get to the results. The results trigger looking at practices, and

you have to do both.

I have been in these suits, and let me tell you, sir, they are nf

easy to win.

Senator HATCH. I understand that.

Mr. H00 ou prove the results,

ir, may you one 0 er q .

tion, but may I pose one other situation? If indeed the word “re-

sults" would lead to all of this, why not then would the word

“intent” lead to the same result, except that the proof would be

higher? What magic is there about the word “results" or “effect,"

if we use either one?

Senator Hamstfizcamfintzlnt” focuses discrimination analysis

upon recesses, ra r t res ts.

Mr. Hooxs'. Sir?

fS‘olizlator HATCH. Because it involves an entirely different method

0 .

Mr. 0038. If you could prove that they intended to deliberately

discriminate, segregate, to keep blacks out of office, and never let

them serve, then would the result be, if the Court finally adopted

that finding that, “In this city we find that they deliberately in-

tended never to let blacks be a part of it, and therefore we man-

date that they must now get proportional representation, since

they have sinned?”

And if they do not have to do it, suppose the Court says, “We

find that the result was that they did not let blacks have office,

and we therefore mandate proportional representation?" What is

the difference between result and intent that would lead to the

concept of proportional representation? I do not understand.

evolve H’VOVWL ’26? 5

Senator HATCH. The difference is, under intent the Court exam-

ines the processes which lead to a given results. Under a result test

only results, regardless of whether anybody intended to discrimi-

nate, are of significance in making a determination as to whether a

violation has occurred or not.

MI Hooxs. I thought you said that you prove intent largely by

resu ts.

Senator HATCH. No. That may be part of the circumstantial evi-

dence in raising the ultimate inference of intent. It is not disposi-

tive in and of itself, however.

Let me just cite the Greenville News about another statement

Mr. Gibson made. ”South Carolina's population is approximawa 30

percent black, and 30 percent of the senate should be black." There

is another illustration of a call for proportional representation.

Mr. Hooxs. Yes, sir, I understand that. I can tell you right now

that you might find there are many statements that we make in

the heat of battle out on the lines and in the trenches that do not

have anything to do with the results we seek.

I wonder also if there were not included in the House bill what I

think is the Sensenbrenner amendment, if I remember correctly,

which says that any language in this bill can never be construed as

to ask for proportional representation.

I think the civil rights community even went along with that

language, so that we could not be accused of seeking proportional

representation.- I think that was an amendment to section 2 which

was proposed by a very conservative Republican from the State of

Wisconsin, if I remember correctl .

Senator HATCH. That that really is no restriction; all you have

got to show is one other factor and you have grounds, for a viola-

tion, whether truly warranted or not.

let me quote another remark of a colleague of yours in the civil

rights community. Rev. Jesse Jackson was quoted in the Columbia

Sun on October 25, 1981, as saying, “Blacks comprise one-third of

the State of South Carolina's population and deserve one-third of

its representation. We believe that taxation without representation

is tyranny." -

I think that the point I am making, Mr. Hooks, is that maybe

these are simply statements made in the heat of battle. But the

fact is this: they are being made. And the fact is this: I do not see

how anybody interpreting that language in the House bill can in-

terpret it any other way. It would ultimately lead to proportional

representation, assuming that the Supreme Court would not find it

unconstitutional.

You have made the point here today that the Supreme Court

may very well decide—I think it would be improper for them to

decide it this way—but that the Court may decide that Congress

has the right to set a legal standard of proof in excess of the consti-

tutional standard. I do not think they will find that in the ultimate

result, but personally I feel that the country should not have to un-

dergo the experiment in the process.

Mr. Hooss. Sir, may I make one other statement? I have on

many occasions in some cities made the statement that, “This city

ought to have a black mayor.” Sometimes I make that statement to

.

pro porHDWlL W G

the white power structure; sometimes I make it to black folk en-

couraging them to vote and register.

Senator HATCH. I find no fault with that.

Mr. Hacks. I am not at all sure that Jesse Jackson ma not have

been talking to a black audience about what they to do in

order to get it.

Proportional representation was not a question, as far as I can

see it, between 1965 and 1980, when at least we behaved that the

effects test was the law. We did believe that.

I must tell you that we were shocked when we discovered in the

Mobile v. Bolden case that it required intent. We certainly did not

believe that at all in preparing that case and taking it up.

I do not recall proportional representation or the mirror image of

the pulation being a present roblem up to that point. I do not

thin it was; I do not think it ' be now.

Senator HATCH. These statements are fine, but the problem we

are raising here today is that these statements are being codified

into law, in my opinion.

Let me quote from the House report on H.R. 3112. It states there

th of proportional representation is y rele-

vant.”

—MF.' Hooxs. I beg giant pardon?

Senator HATCH. 'dence of lack of proportional representation

is highly relevant in proving a section 2 violation under the results

test. Indeed, there is no other factor that they describe in this

manner. What does that language mean, in our view?

Mr. Hooxs. It means exactly the same t 'ng to me, Senator, if

they had said that proof of proportional representation or lack

thereof is very important to prove intent. I just do not think there

is any difi‘erence at all between intent and results when you talk

about pro rtional representation.

Certain y, if I were trying a lawsuit, or if you were, for some

reason, hired b my organization to try a lawsuit—and maybe one

day we will be in that hapr circumstance—you. would not say that

even under intent lack o roportional representation deals with

the fition of results, whic deals with the question of intent. I do

not t ‘ k it means any more or less.

I do think certainly, if I were trying a lawsuit, I would deal with

the fact that there were five city council ple elected and no

blacks over a 40-year history, which has to o with representation,

whether'you put proportional in front of it or not. I would make

that same argument whether I was arguing under an intent test or

results test. do not see how I could make any other argument. I

would have to use it.

I just fail to see where the word “result” in denying or abridging

the rights is any different from intending, except someone tells me

that ou cannot rove intent, therefore it becomes a nullit .

I ‘ —and have said before—that the primary dif erence is

that the Administration bill would make it difficult, if not impossi-

ble, to ever win a case, because it would demand that you prove

intent, and intent is a subjective matter.

I believe, with Senator Mathias, that the Court in Mobile v.

Bolden did more or less a dim view of ' ' '

m-

stantial ‘ an emand in n in the strictestf There-l

Ropmdfimal Eqa. ?—

fore, if result tests resulted in iroportional representation, the

mtent‘tfit’wofld if you could prove it.

MAybe—certainly not from yourWiEWpoint, because you would

not think like that, but maybe from the viewpoint of some—they

are saying. “Let’s get intent in there, and since it can never be

proven, we won’t have to worry about it." But I maintain the re-

sults would be absolutel no different, except the standard of proof.

I fit hearing the ttorney General say that the reason he

wan intent was that the standard of proof would be much

higher. Yet he kept saying that results would be a part of that

standard of roof. You have to look at results, and it may be, in

some cases, t e onl proof you do have.

nator HATCH. t me just say this: I appreciate your courtesy

to me and your kind remarks, but the issue is greater than that.

This is a critical constitutional issue. As a practicing trial lawyer

before I came to the Senate, I had very few cases where I did not

have to prove some kind of intent. In fact, in every criminal case, I

had to demonstrate intent, and beyond a reasonable doubt. And in

many of the civil cases I had to prove intent by a preponderance of

the evidence. It is done every day in every court of law in this

country; If the proposed changes in section 2 would make no differ-

‘ence, t en why are you fighting so_vehemently for the change?

’ ' ‘ hat any rea-

' indin that the chairman refuses to think t .

gabfgypgrson 8or group of. persons might make3—both the White

decision and the Chavez deCision, in 1971 and 197 . h' h licitl

It is our intention to enbrace those deCisions w ic exp Ml?

barred proportional representation based upon percentage? as me

Hooks has testified to. It is an attempt to take what t e upurcel be

Court has said in both of those calzets)e and to insuf:1 tthat it wo

ard b which there wou measurem. .

thfifainng move): on. Quite frankly, Mr Hooks, With all dueJresgpsegt,

whatever was stated by my good friend and yours, Jesse ac ,

and by others who made comments or statements that were read

' ' ' th law. The

into the record, they are not gomg to be codified into epropriatel;

one of viewpoints, but as you quite ap

mtiitebd' :fifres‘s; law is what is in the statute; it is more, walla

gen than what is in the report, although we have heard commen

about report language almost as if it were included in the statute

itself. My understanding as one of the prime sponsors is in accord

with yours and with the casechiwu.

2 (p ) / Senator KENNEDY. Sure. The Supreme Court effectively made

$1"an at WWW Mal/HVWZ.

Prgpared

l J

S _ 0(0 ’ ' en an is stan inoo y conten

F - go enact a requirement of "proportional representation” of minorities in governmental

bodies. Clearly the standard outlined above requires far more than proof of lack of

“proportional representation." At a minimum. minorities would have to show racial-

l polarized voting together with other objective factors which effectively preclude

eir participation in the political process or dilute the value of their vote.”

The issue then, is not proportional representation, but equal aooeu to the political

process. This does not guarantee that minorities will be elected to oflioe; it does

gmantee that minorities who are barred from holding office or whose votes are de-

because of their race or membership in a language minority group will have

legal channels through which to challenge their exc usion. I?“ exclusion I mean far

more than an outrig t bar on voting or running for office. e Supreme Court has

consistently held that “the ' ht of suffrage can be denied by a debasement or dilu-

tion of the weight of a citizen s vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the

free exercise of the franchise." Reynoldsav. Sims, 377 US. 533, 555 (1964); see also

I

Pmpo vl-w‘oma/L Pep. 8

Testimony o¢ E. Fvfiemm Levevei’l'

iii/9?

fit“

' Se tor HATCH. ' . What is the standard? what does the

urII:1 2s itse under the effects test? Can you define that?

Mr. szms'i'r. No, sir.rI would think, though, from-reading the

committee report, that the intention is to impose a discriminatory -

impact or effect standard that is no less than the standard in sec»

tion 5, and in fact I think it will be even more stringent because of

the Supreme Court decisions that limited the literal langu e of

section 5 in the Beer case based upon the peculiar purpose 0 sec-

tion 5, which background is not applicable to section 2. _

Senator HATCH. Maybe that is one of the reasons why I never get

an answer to that question from anybody, and we have the top

legal experts in this particular field on the other side of this issue.

Nobody yet has answered that question very satisfactorily, and I

think one of the reasons they are afraid to answer it is because

they know section 2 must lead inevitably to proportional represen-

tation. Do you agree with that assesment? _ .

Mr. vanam. Yes, sir; there is no doubt about it. ' ‘

. J

Senator HATCH. Do you see any other result the section 2 change:

could have, under the im lications of term “result”?

Mr. LEVERE'I'I'. No, sir; think the word “result” is just as strong-

as “effect" or “impact" and rhaps even more so.‘

Senator HATCH. OK. you. ' 'f

Mr. Lzmm. The second point I wish to make Concerning the

amendment to section 2 is that in my opinion it will go even fur-

ther than the effect language of section 5. In Beer v. United States,

which is the New Orleans case, the Supreme Court held that the

literal language of section 5 was limited, that it would not be given

complete effect according to its terms because it had to be read in

its context, and its context was to prevent changes in laws that

would result in retrogression in the position of minorities in cov-

ered States. ~ .

Consequently, in the Beer case the Supreme Court rejected the

contention of the‘Attorneivl General and the District Court of the

District of Columbia, whic had said that under section 5 the reap-

portionment laws were required to maximize the political gower of

minorities. There is nosimilar basis, however, in section for im-

posing) such a limiting construction. Consequently, there is a real

probe ility in my opinion that section 2 as amended will be con-

strued as requiring the maximization of the political power of mi-

norities in connection with any reapportionment law.

" Another basic point m needs to be pointed out here is

that while we have used in this debate terms of discriminatory

effect or discriminatory impact, this term really in civil rights ju-

risprudence means disparate im act. It does not have necessarily

the connotation of something e ' or something malicious or mean.

It simply means that in its actual operation it produces an effect

on one group that is different than it produces on another. This

has been borne out in the similar language in title 7 of the 1964

Civil Rights Act.

Propovdw‘orxal QCP' ?

Now coming to the consequences of the amended section 2, the

first area that I think this will dramatically affect is with respect

an“ = II" -er -‘ I -.:: ‘ - , H W'lative and local district-

- : a result of the release of the 1980 census, m ‘ = a: are

~ -- the process of revising their congressional district 1' es,

their legislative seats, their legislative districts in State legisla-

tures, and political subdivision elections.

At present these laws are governed by the traditional constitu-

tional standard of discriminatory intent or purpose. That was so

held in Wright v. Rockefeller in 1964 involving New York. Section

2, however, would now apply the new race-conscious impact or

result test to State legislative districting and con essional district-

ing, and in consequence it would mean that all 0 these laws would

have to be jud ed by how they affected a particular minority, if it

was a protected minority under section 2.

The likelihood is that these laws will have to maximize the polit--

ical strength of protected minorities. Redistricting consequently is

going to become much more race-conscious and much more difficult ‘

as a resJult. \ I

The second area that will be affected by the amendment to sec-

tion 2 is in connection with municipal annexations and governmen-

tal consolidations. When new areas are annexed and are subject to

section 5 preclearance, and the effect is to reduce the overall mi-

nority percentage in the political subdivision, the Supreme Court

has'held that the city or the political subdivision must convert to

single-member district elections with districts gerrymandered so as

to insure that the minorities would have proportionate representa-

tion in the e '

fact, it was only with great diffi

rejected—and even then with three judges dissenting—the conten-

tion that there could not be any annexations anyway unless the

minorities had the same fififical strength in the new community

that they had in the old. e Supreme Court rejected that but not

without great difficulty, and even then three jud es dissented.

_ However, keep in mind that in connection wit section 5, the lit-

eral consequences of that section have been limited by the Su-

preme Court’s decision in Beer, which says that this section was de-

signed only to prevent a retrogression and therefore it was not re-

quired to maximize the power of minorities, but no similar rovi-‘

sion or policy consideration would be applicable to section 2. ere-

fore, the fact of the matter is that section 2 is likely to be applied

so as to prevent annexations or consolidations in their tracks in

situations; ~

O

P ' qo {Wr that is set forth in the proposed amendment to

section.2 in my opinion will not accomplish anything. The reason is

that this disclaimer does not add anything new. It has already been

enunciated in the very cases that established the dilution doctrine.

These cases have required the abolition of at—large districts, not-

mthstanding that they have expressly articulated this disclaimer.

However, more important, as has been pointed out here earlier

today, this disclaimer will be construed in the light of the language

at (page 30 of the report of the House which says that all you have

to. o is to show that over a period of time candidates offered by the

minorities have been consistently defeated. This goes further than

any court decision has ever gone, and in fact this was expressly re-

jected, this argument was expressly rejected in Lodge v. Buxton at

pages 1362-13 3.

Fropov‘i'VOW 26p. ’0

Frapavaq Stew Of' 5' 966mm Leaves/2+?

P I qo? I . I or equal significance to the general doubt and contusion

which the Section 2 amendment will produce. is the nature or the

change it will inflict. While the immediate issue is stated in

terms 6: 'ettect' vs. 'intent', the bottom line is proportional

racial representation, and reverse discrimination. As a lawyer who

has been of counsel in a number a! voting rights cases, I have par-

sonelly observed the emergence of new doctrine which says that a

minority, is entitled to representatives proportionate to their

numbers. and that any law which in practice disadvantages that group

in any way, regardless 0! its otherwise valid concerns. is by the

former {act alone rendered invalid. .An 'etfect' or 'impact' test

is nothing short of a formula for special privilege and reverse

discrimination, and necessarily tends to exacerbate and aggravate.

rather than to alleviate. racial ditterences and antagonisms.

‘

q). 0(0% "i ' W50] q-“

At page 30, th; Committee notes that as so revised, 52 would

include 'not only voter registration requirements and procedures, 225

also methods of election and electoral structuresI practices and

orocedures which discriminate.‘ While disavowing any effort to mandate

proportional representation in all cases, the report makes it clear

that this is the objective in most cases:

'It would be illegal for an at-large election scheme for

a particular state or local body to permit a bloc voting

majority over a substantial period a! time consistently

to defeat minority candidates or candidates identified with

the interest or a racial or language minority' (ld.).

THE DISCLAIMER IN SECTION 2 ADDS NOTHING

The House Committee Report asserts that the amended Section 2

will not be construed as mandating proportional representation.

because the amendment includes this language:

'The fact that members of a minority group have not been

elected in numbers equal to the group‘s proportion or the

population shall not, in and of itself, constitute a viola-

tion of this section.”

\

PmPOVthWL 26p H

This disclaimer is not valid. The principle contained in the

additional section just quoted is already theKla!,/£or the Supreme

Court and the lower courts have expressly so held in a number of

cases. Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 0.8. 124, 149 (1971); White v. Regester,

412 0.5. 755, 765-6 (1973): City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 0.5. 55, 66

(1930); Zimmer v. cheithen, 485 F2d 1297, 1308 (C.A. 5th 1973)] affd.

sub nom East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 0.5. 636

(1976): Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds CountyI 554 F2d 139

(C.A. 5th 1977), cert. den. 434 0.5. 968; David v. Garrison, 553 de

923 (C.A. 5th 1977): Nevett v. Sides, 571 F2d 209, 216 (C.A. 5th

197a), Lodge v. Buxton, 639 FZd 1358, 1362 (c.a. 5th 1981), stay

granted sub non Rogers v. Lodge, 439 0.5. 948 (1978), probable juris-

diction noted October 5, 1991, 0.5. ,_70 L.Ed.2d 80 .

In White v. Regester, supra, the only decision or the Court to

uphold invalidation or e multi-member district on constitutional grounds,

the Court declared:

'To sustain such claims. it is not enough that the racial

group allegedly discriminated against has not had legisla-

tive seats in proportion to its voting potential" (412 0.5.

at 765-6).

Yet, it is this same case, White v. Regester, which gave rise

to the ‘disparate impact' test which a later Court just disapproved

in City of Mobile v. Bolden, supra, and which has been used in many

cases to strike down at-large voting arrangements, and to require

deliberate gerrymandering of election district lines in order to achieve

varying degrees or racial balance in representation.

Consequently, since the disclaimer is already a principle firmly

established in the very cases which have given rise tothe 'disparete

impact' test in election cases, its restatement in the amendment to 52

in HR 3112 does nothing to alleviate the force of the disparate impact

language which precedes it, and in fact, it is obvious tram the

Committee Report that the sponsors of Bk 3112 intend'ior it to impose

an even more rigorous disparate impact standard than the one disapproved

in City of Mobile v. Holden, supra.

ENSTHE RULE THAT THE FAILURE

OF MINORITIES TO ELECT REPRESENTATIVES IN PROPORTION TO

THEIR NUMBERS DOES NOT ESTADLISH DISCRIMINATXON

The disclaimer added to 52 necessarily will be construed in the

light of the House Committee Report quoted above (p. 4) to the effect

that it would be illegal for an at-lsrge scheme . . . to permit a bloc

voting majority over a substantial period or time consistently to

defeat minority candidates. . . (Report, p. 29).

so being, it ii cledr that the statement of the Committee Report

goes further than any existing court decision in mandating proportionate

racial discrimination. No case yet decided has held that the mere fact

that minority candidates are consistently defeated operates to invalidate

an election plan. Indeed, the cases previously cited all held to the

contrary. They require some additional factors, such as a history of

past discrimination, unresponsiveness of legislators to minority needs,

and the like. Yet, the sponsors of HR 3112 andounced in the Committee

eport that such is their intent.

Pmpov-Homal (26(3- )7"

It hes the Lima; case which gave rise to the so-called 'zimmer

dilution analysis,‘ which is responsible for having ushered in a

virtual reconstruction of a staggering number of city councils, county

commissioners and boards of education in the southeastern United .

States. All of this has been accomplished without any showing of

discriminatory intent. In many instances, at-large election laws

in existence for over 60 years, adopted during a period when it is certain

they were not designed as engines of discrimination, were struck down

under the zimmer approach. In a number of other cases, at-large laws

enacted subsequent to 1964 were denied preclearance under Section 5.

I personally as familiar with a number of jurisdictions in Georgia which

sought to use at-large election simply as a convenient. ready means of

complying with the one-man-one-vote principle following the court's

1963 decision in Avery v. Midland County, 390 0.5. 474 (1963), and its,

1970 decision in Hadley v. Junior College DistrictI 397 0.5. 50-(1970),

holding the reapportionment principle to local governing bodies such

as boards of education and cities.

The invalidation of at-large elections has been conjoined with

a requirement that election districts be gerrymandered so as to

achieve varying degrees of proportionate racial representation. In

remedying dilution, the courts in the Fifth Circuit have been quite

direct in holding that race must be considered, Zimmer v. Hokeithen,‘

supra (485 r2d at 1303); Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds

County, supra (554 Fld at 151); united States v. Board of Supervisors

of Forrest County, supra (571 FZd at 955), and in Kirksey, the Court

in effect mandated racial gerrymanders in order to insure some degree

of proportionate representation. (See particularly, 554 P2d at 151.

and Judge Gee's concurring opinion, at p. 153). The real pervasivenoss

of this reverse discrimination requirement is not usually spelled out in

words in most of the cases for obvious reasons. It simply is effectuated

by the Court's refusing, without explanation, to approve any plan except

e which does maximize minor‘tu “ , r _

"‘nc .A—-—— l_________*_—’,

It is the Zimmer disparate impact dilution principle, of course,

that City of Mobile v. Bolden disapproved, and which the amendment to

Section 2 seeks to restore in an even more rigorous form. That the

standard under a revised Section 2 will be even—fi::_:::::::z_:::-—-———ar’

First, heretofore, the rule was one solely of judge-made law,

designed to 'fill in the gap' in the common-law tradition. “hon, however.

Congress enacts it into law, this represents a policy-decision by the

proper policy-making body, and the Courts generally apply the statute

more forcefully than the judge-made rule. It is not even certain, for

example, as to whether the courts would continue to require the Fifth

Circuit's showing of the traditional 'aggregate of factors" to invalidate

at-large voting, or simply adopt a per 32 rule.‘

Secondly, Section 2 comes armed with a House Committee.roport

specifically declaring that Congress intends that in any community where

blacks have been unable over a period of time to elect representatives

commensurate to their numbers, at-large elections stand condemned by

Section 2. The report laments the fact that blacks have not registered

or been elected in the same proportion as whites (Report, pp. 7, 9),

making apparent that Section 2 is aimed at achieving proportional repre-

sentation.

pmpowh‘bhdl (Zap. '3

Even assuming, however, that the Courts continue after the

amendment of Section 2, to require a showing of something in addition

to the inability of minority persons to win elections in order to invalidate

at-large elections, the Zimmer formula will continue to provide that

'something 'else'. Essentially, as applied, the Courts have given

controlling significance to that part of the Zimmer analysis which is

concerned with a history of prior discrimination. ‘ The high point of this

development came in Kirksey v. Supervisors of Hinds County, 554 Md 139

(C.A. 5th 1977), cert. den. 434 0.5. 96!, where the Court held that'it

was necessary only to show a past history of discrimination in areas

unrelated to voting, and that the at-large‘scheme perpetuated 'an' I

existent denial of access by the racial minority to the political

process . '

P Q7 5 -2 a, f’ “I" “3,. "E 2.2m?s:z:3:.:s.:z-mama?”

P As previously stated, in every case where at-large elections have

been successfully invalidated by court decision. therehave been efforts

by the plaintiff's counsel, which usually have been successful, to

mandate a remedy which not only converts to single-member districts,

but also to racially gerrymander single-member districts which 'insure

varying degrees of racial proportionality. As a lawyer who has been '

of counsel in several of these cases, it has confronted me in every

one. lnvariably, the' effort is made to gerrymander election districts

that will have a minimum of 65‘ to 70‘ minority citizens, since it is

felt by civil rights groups that because of the tendency of many ‘

minorities not to register or vote, a substantially greater percentage

then a bare majority is necessary to insure election. This has also

invariably been the experience in connection with preclearance in '

covered jurisdictions‘undar $5 of the voting Rights Act. In one case

which I handled involving‘ Wilkes County, Georgia, I was advised by a

representative of the Justice Department that they would agree to pre- _

clear a single-member district plan if one district would be devised

so as to provide for a 70\ black majority.

This apparently has been the'experience with Justice Department

officials in the Voting Rights division in a number of other cases,

for in United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 0.5. 144 (1977). there

is a reference to an anonymous telephone call from a representative of'

the Justice Department to this effect:

”A staff member of the Legislative Reapportionment Comittee

testified that in the course of meetings and telephone

conversations with Justice Department officials, he got the

feeling that 65! would be probably an approved figure. for

the non-white population in the assembly district in which

the Hasidic Comnity was located, a district approximately

61\ non-white under the 1972 plan.‘ (430 0.3. at 152).

Vmpowhomal [2619’ W

"hat is being sought here is governmental action which forces

governments and public officials to think and act along racial lines.

(Ely, islative and Administrative Motivation in Constitutional

£33, 79 Yale L.J. 1207, 1260 (1970). It is, in effect, an insistence

upon segregated election districts, which reinforces the bloc-voting

syndrome. David v. Garrison, 553 F2d 923 (C.A. 5th 1977 ). Such

reverse discrimination exacerbates, rather than reducesj—rbcial tensions.

university of California Regents vz Bakke, £30 0.5. 265, 29! (Opinion

of Justice Powell) (1978).

Even Mr. Justice lrennan, who is no enemy of benign discrimination,(

has recnqnired that an effort to achieve proportional representat

could be used as a 'contrivance to segregate the group. . thereby

frustrating its potentially successful efforts at coalition building

across racial lines." United Jewish'Organizations v. Carey, supra, /

(430 0.5. at 172-173). He further notes that such a policy ”may serve

to stimulate our society's latent race consciousness, suggesting the

utility and propriety of basing decisions on a factor that ideally

bears no relationship to an individual's worth or needs,” (ld.,

p. 173), and that "we cannot well ignore the social reality that

even a benign policy of assignment by race is viewed as unjust by

many in our society, especially by those individuals who are adversely

‘affected by a given classification.” (Id., p. 17‘).

A more practical concern with proportional representation,

‘however, has been articulated in the two cases dealing most directly

with the subject of at-large voting.

In Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra, 403 0.3. at 156-157, it was said:

’The District Court's holding, although on the facts of this

case limited to guaranteeing one racial group representation,

is not easily contained. It is expressive of the more I

general proposition that any group with distinctive interests

must be represented in legislative halls if it is numerous

enough to command at least one seat and represents a majority

living in an area sufficiently compact to constitute a single

member district. This approach would make it difficult to

reject claims of Democrats, Republicans, or members of any

political organization in Marion County who live in what

would be safe districts in a single-member district system

but who in one year or another, or year after year, are

submerged in a one-sided multi-member district vote. There

are also union oriented workers, the university community,

religious or ethnic groups occupying identifiable areas of

our heterogeneous cities and urban areas.- Indeed, it would

be difficult for a great many, if not most, multi-member

districts to survive analysis under the District Court's

view unless combined with some voting arrangement such as.

proportional representation or cumulative voting aimed at‘.

providing representation for minority parties or interests.

At the very least, affirmance.of the District Court'would

(mpovh‘oml 26!? - ’5—

spewn endless litigation concerning the multi-member district

systems now widely employed in this country.‘ (403 0.5. at

156-157) . . . '

1n the plurality opinion in City of Mobile v. Bolden, supra,

Mr. Justice Stewart posed similar questions, in response to the

dissenting opinion of Justice harshall, which in effect, advocated

a constitutional requith of proportional representation for blacks

or other persons who had been subjected to a history of discrimination:

'It is difficult to perceive how the implications of

the dissenting opinion's theory of group representation

could rationally be cabined. Indeed, certain preliminary

practical questions imediately come to mind: Can only

members of a minority of the voting population in a particu-

lar municipality be members of a 'political group'? How

large met a 'group' be to be a 'political group'? Can

any 'group' cell itself a 'political group'?. If not, who is

to say which 'groups' are 'political groups”! Can a qualified

voter belong to more. than one 'political group'? Can there

be more thanvone 'political group' among white voters (e.g.,

Irish-American, Italian-American, Polish-American, Jews, A

Catholics, Protestants)? Can there be more than one

'political group' among nonwhite voters? Do the answers

to any of these questions depend upon the particular demo-

graphic composition of a given city? Upon the total size

of its voting population? Upon the total size of its

governing body? Upon its form of government? ,Upon its

history? Its geographic location? The fact that even

these preliminary questions may be largely unanswereble

suggests some of the conceptual and practical fallacies

' in the constitutional theory espoused by the dissenting '

opinion, putting to one side the total absence of support

for that theory in the Constitution itself.‘ (“6 0.5. at

78, f.n. 2‘).

He reiterate what we have said before:. The immediate question

here is discriminatory impact vs. discriminatory intent, but the

bottom line is proportional representation. Nothing could be more

impractical, more injurious, or more divisive

of national u i

the idea that discrete. n ty "“1

groups are entitled to proportional represen-

ӣ1611.

It V111 COMICCIIY destroy any hope thl! Ch. blacks and

DfihOI' racial minorities in Chi. count V111 0V0! b. lHEOQI'lt d

ry I into

the total society .

€Y‘DPOV‘l‘lefl 2(5)?- M7

Section 2, however, is a permanent law, and applies not just at the

q 3 l ”3% point in time of initial enactment, and unlike Section 5, is not limited

in its legislative purpose to preventing only retrogression arising from

changes, but is likely to be enforced according to its clear terms,

unlimited by the peculiar purposes of 55. The Egg; case itself demon;

atrates the tendency of the courts to enforce the Voting Rights-Act

in a bro 4, sweeping manner. While the case deals with preclearance

of a new reapportionment plan and not an annexation, the case is never-

theless pertinent here as being indicative of the general attitude of

the courts. In that case, a new reapportionment plan was devised so as

to give the blacks in New Orleans one black voter majority district.

Previously they had none. Both the attorney General and the district

court in the District of Columbia refused to approve the plan, however,

because if the district lines had been drawn in an East-Heat configura-

tion, rather than a North-South one, blacks likely would have achieved

districts guaranteeing them proportional representation. In other

words, the lower court held that the redistricting had to be done so as

to maximise black voting strengthI i.e.l prooostional representation.

The Supreme Court rejected this contention only by looking at the peculiar

purpose of 55, and than only by a 6-3 majority,JusticesHhite, Marshall

and srennan contending that Under 55, proportional representation was

reguired. The majority held that in 55, Congress was mainly concerned

with changes EELE! resulted ig retrogression.

.The considerations which prompted a majority of the Court to reject

proportional representation in the Egg; case will not be present under a

permanent law such as Section 2. The latter'a thrust is not just at

covered jurisdictions, and is not limited to preserving the status ggg

3553.

The foundation for such a distinction has already been laid by the

District Court in the District of Columbia in City of Port Arthur v. Unitef

States, 517 P. Supp. 987 (D.C. D.C. 1981), where the Court discussed the ,

r

implications of annexations at length, and in denying preclearance because

a plan was not gerrymandered so as to insure proportional representation

to blacks, held that the Beer rule did not apply to annexations, i.e..

merely insuring that there was no retrogression, was not sufficient here.

Similarly, in the City of Richmond case, supra, the district court

had disapproved the annexation altogether, despite the fact that the dis-

tricts had been devised so as to insure blacks proportional representation.

The Court was concerned mainly by the fact that blacks nevertheless would

no longer be a majority in the new enlarged city. The supreme Court re-

jected the district court's decision on this issue, but not without some

difficulty, and even then, by only a 6 to 3 majority. 422 0.5. 358 (1975).

The message of all this is clear: The amended Section 2 will stop

noet annexations and governmental consolidations in their tracks, for under

the wording of 52, without the limiting construction applicable to 55, any

annexation which reduces a black or language-minority majority is proscribed