Respondents' Memo in opposition To The Applicant To stay The Mandate of The U.S. District Court For The Eastern District of N.C.

Public Court Documents

February 27, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Respondents' Memo in opposition To The Applicant To stay The Mandate of The U.S. District Court For The Eastern District of N.C., 1984. ac9b8e16-d592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e857cc6f-7c37-4a2c-b477-8c85590097d6/respondents-memo-in-opposition-to-the-applicant-to-stay-the-mandate-of-the-us-district-court-for-the-eastern-district-of-nc. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

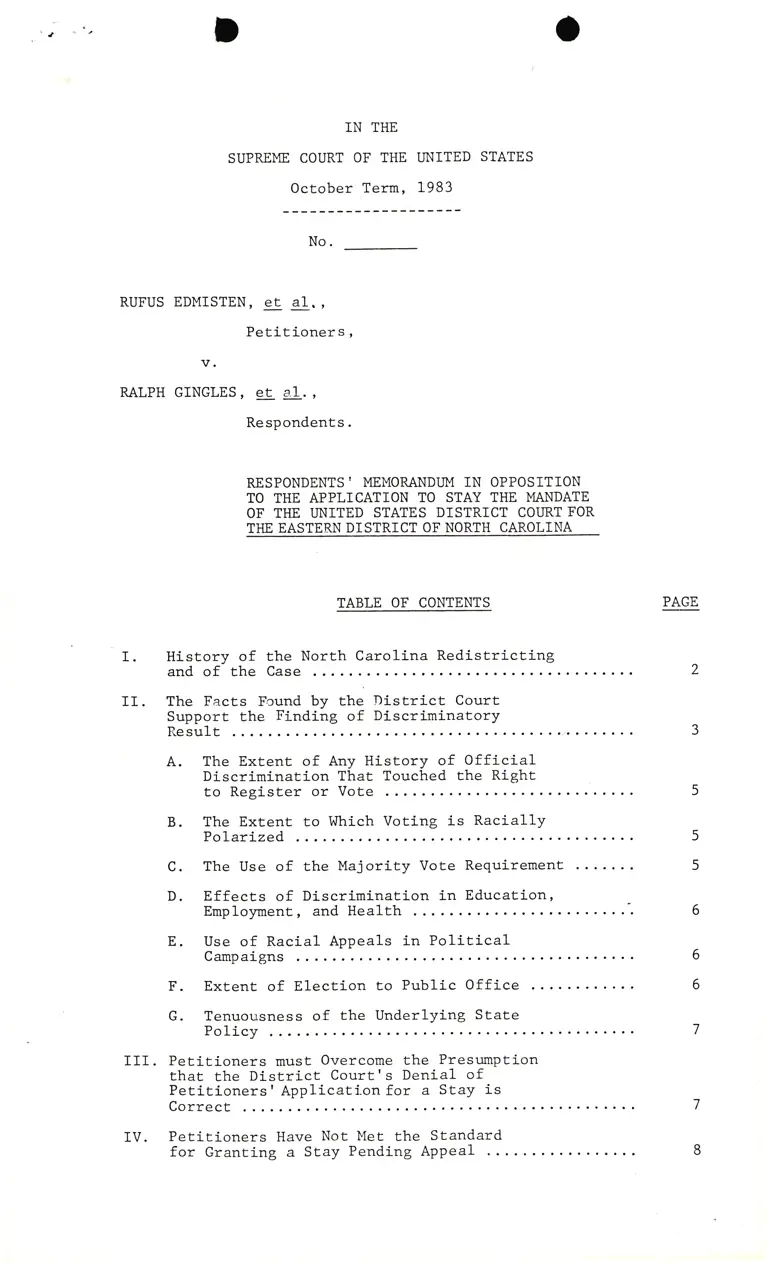

tN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1983

No.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et 31.,

Petitioners,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et o.L.,

Respondents.

RESPONDENTS' },IEMORANDI]M IN OPPOSITION

TO THE APPLICATION TO STAY THE MANDATE

OF THE I]NITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. History of the North Carolina Redistricting

and of Ehe Case

II. The Facts Fcund by the District Court

Support the Finding of Discriminatory

Result

A. The Extent of Any History of Official

Discrimination That Touched the Right

to Register or Vote

B. The Extent to l,Ihich Voting is Racially

Polarized

C. The Use of the Majority Vote Requirement

D. Effects of Discrimination in Education,

Employment, and Health

E. Use of Racial Appeals in Political

Campaigns ...

F. Extent of Election to Public Office

G. Tenuousness of the Underlying State

Policy

III. Petitioners must Overcome the Presumption

that the District Court's Denial of

Petitioners' Applicati.on for a Stay is

Correct

PAGE

6

6

IV. Petitioners Have Not Met the

for Granting a Stay Pending

Standard

Appeal

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. Petitioners Have Not Established

a Probability That TheY Will

Ultimately BL Successful on the

Merits of the ApPeal

1. Section 5 Preclearance does

not Preclude Section 2 Review

2. The District Court did not

err in aPPlYing the standard

for findlng a violation of

Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act

The District Court was not

clearly erroneous in deter-

mining that there is severe

and persistent raciallY

polarized voting in the dis-

tricts in question

The District Court did not

erroneously reject Ehe State's

evidence

PAGE

l0

t1

3.

t4

L7

4.

B. Petitioners Have Failed to Show

That They Will be lrreParablY

Harmed if a StaY is Denied

1. Complianee with the District

Court Order will not undulY

disrupt the 1984 election

2. A stay is

serve the

meaningful

not needed to Pre-

State's right to a

appeal

19

19

2L

23

26

C. The Irreparable Harm to Respondents

and the Injury to the Public

Interest oi Glanting a Stay Outweigh

any Possible Harm to Petitioners of

Denying a Stay

v. Conclusion

- II-

On January 27 , f984, the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of North Carolina, sitting as a three

judge court, entered a unanimous Order which (1) declares

that the apportionment of the No-rth Carolina General Assembly

(hereafter the "General Assembly") in seven challenged districts

violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

42 U.S.C. S1973 (hereafter "the Voting Rights Act"), (2) enjoins

elections in those districts, and (3) gives petitioners seven

weeks to enact a districting plan which does not violate the

Ll 2/

Act.

This matter is before the Court on the application of

Rufus Edmisten, Attorney General of the State of North Carolina,

(hereafter "petitioners") for a stay of the January 27, 1984

Order.

Ralph Gingles, €t 41., on behalf of the certified class

of all black citizens of North Carolina who are registered

to vote (hereafter "respondents") oppose the application

on the grounds that (1) a stay of the District Court's Order,

whieh would enable the Lg84 elections to be held under a

districting Plan which the three judge Court has determined

is illegal, woul-d irreparably harm respondents ; (2) peti-

tioners have not demonstrated that comPliance with the

District Court's Order will i-rreparably harm them, and (3)

Ll The January 27, 1984 Order was entered concurrently-with

I,lemorandum Op inion-which is , hereaf ter , cited as "Mem. Op . "

copy of the i{emorandum Opinion is provided herewith.

2/ The North Carolina House of Representatives consists of

l-20-seats apportioned into 53 districts. The District Court's

Order coverl- 26 of those seats in the following 5 House DisEricts:

(1) House District ll8, composed of tJilson, Edgecombe, and Nash

iounties, has 4 repiesentatives; (2) House District llzl, composed

of Wake County, has six representatives; (3) House District t123,

composed of Durham County,-has 3-representatives; (4) House

Dislricr !139, composed oi part of Forsyth County, !a-s- 5 lePfe-

sentativei; and til House bistrict 1136, composed of Mecklenburg

County, has 8 representatives.

The Court's Order leaves the state free to proceed with

elections in the remaining 48 House districts, as the violations

of Section 2 can be correited in each of these five districts

without affecting any other district.

The North Carolina Senate consists of 50 seats apportioned

into 29 districts. The District Court's Order covers 5 of these

(Footnote 2 cont'd)

a

A

petitioners have not demonstrated a likelihood that this

Court will reverse on the merits.

I. History of the North Carolina Redistricting

and of the Case.

The District Court's Order followed a lengthy redistrict-

ing process in North Carolina. A brief summary of the process

is helpful to understanding the Order.

North Carolina initially enacted redistricting of its

House of Representatives and Senate in response to the 1980

Census in July, 1981. This action was fiLed on September L6,

1981-, claiming, inter alia, that the districting of the General

Assembly was iLlegal and unconstitutional in that (1) it had

population deviations of over 202 in each house in violation

of one person, one vote requirement of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution; (2) it had been enacted pursuant to provisions

of the North Carolina Constitution which were required to

be but had not been precleared under Section 5 of the Voting

3/

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. S1973I and (3) the use of multi-member

districts illegaIly submerged minority population concentra-

tions and diluted minority voting strength in violation of

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

After the Complaint was fi1ed, the State of North Carolina

submitted the provisions of the North Carolina Constitution,

which prohibit dividing counties in the formation of a

legislative district, to the Attorney General of the United

2l (cont'd) seats in two Senate Districts: (f) Senate

District #22, composed of MeckLenburg and Cabarrus Counties,

has 4 senators; and (2) Senate District ll2, composed of

Bertie, Chowan, Northampton, Hertford and Gates Counties and

parts of Halifax, Martin, Edgecombe, and Washington Counties,

has one senator.

The Court's Order leaves the State free Eo proceed with

elections in most other districts although remedying the

violation in Senate District ll2 wLLL necessarily affect the

adjacent districts as we11.

3/ Forty of North Carolina's 100 counties are covered by

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

-2-

States for preclearance under Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act. The Attorney General, in a letter signed by William

Bradford Reynolds, objected to the provisions finding that

the use of large multi-member districts "submerges cognizable

population concentrations into larger white electorates. "

Mem. Op. at 5.

The Attorney General, acting through Reynolds, also

found the 19Bl House, Senate and Congressional plans, as

well as two subsequent House plans and one subsequent Senate

plan to be racially discriminatory insofar as they affected

the 40 of North Carolina's 100 counties subject to Section

5 review. Despite warnings from special- counsel, black

eitizens' groups and various i-egisl-ators that this method

could result in impermissible dilution of black citizens'

voting strength, the General Assembly continued to use multi-

member districts in the five House districts and one Senate

district in question. Mem. Op. at 62. Five of these six

districts consist entirely of counties not covered by Section

5 and, therefore, were not subject to the Attorney General's

review.

After a full evidentiary tria1, the District Court found

that, considering the totality of the relevant circumstances,

Ehe specified six multi-member districts result in the sub-

mergence of black registered voters as a voting minority

and in black voters' having less opportunity than do other

members of the electorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representaLives of their choice. The

District Court further concluded that, Senate District No. 2,

because it fractures minority voting strength, has the same

result. (Mem. Op . at 65 -66)

II. The Facts Found by the District Court

Support the Finding of Discriminatory

Result.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was

by the VoLing Rights Amendments of L982, 96

29, 1982) . The amendment was enacted after

amended in L982

Stat. 131 (June

extraordinary

-3-

national and congressional debate. The congressional

examinaEion includes over 5,000 pages of committee hearings, and

extensive debate in the comrnittees and on the floor of both

houses over the course of a year and a half.

The result of this monumental- congressional effort

was an amendrnent to SecLion 2 which provides that a claim

of unlawful vote dilution is established if, "based on the

totality of circumstances, ',' members of a racial minority

"have less opportunity than other members to participate in

the political Process and to el-ect representatives of their

choice," 42 U.S.C. S1973, as amended. The Committee Reports

accompanying the amendment make plain the congressional intent

to reach election plans that minimize or cancel out the

voting strength of minority voters, S. Rep. No. 97-4L7,

97th Cong., 2d Sess. at 28 (L982) (hereafter Senate Report);

H. Rep. No. 97-227, 97t]n Cong., 1st Sess. at 17-18 (1981)

(hereafter House Report).

The Senate Report, at pages 27-30, sets out a detailed

and specific road map for the application of the amended

Section 2. Although the amendment embodied a clear change

in the 1aw, the inquiry it requires is familiar to the trial

courts from a decade of applying the analytic f::amework of

white y. Regester, 4L2 U.S. 755 (1973). Thus the "totality

of circumstances" approach specified by Congress is not novel.

I,rlhen called upon to aPply the statute, as amended, to a

claim of unlawful dilution, Congress directed the federal

courts to determine racial vote dilution by engaging in an

intenseLy local appraisal of the interaction of the challenged

electoral mechanism with the relevant factors enumerated in

the Senate Report at 28-29.

It is apparent from the analysis of Section 2 contained

in the Memorandtrm Opinion, see especially Mem. Op. at 14, and

from the detailed assessment of the facts, that the District

Court understood its congressional charge, and applied the

intent of Congress to the facts of this case'

-4-

Upon consideration of numerous stipulations, voluminous

documentary submissions, and eight days of trial testimony,

the District Court, whose members were three life long North

Carolina residents, carefully and thoroughly examined each

of the relevant factors. The District Court deLermined that

there was amPle evidence of six of the seven factors set

out by Congress before concluding that a violation was

established by the totality of circumstances.

A. The Extent of Any History of Official

Discrimination That Touched the Right

to Register or Vote.

The current disparity in black and white voter regis-

tration is a legacy directly tracable to the direct denial

and chilling by the State of registration by black citizens'

The use of a literacy test until L970 and anti-single shot

voLing laws and numbered seat requirements until L972 Lrad

the intended effect of diminishing minority voting strength.

The racial animosities and resistence with which white citizens

have responded to attempts of black citizens to Participate

effectively in the political process are still evident today.

Mem. Op. at 26-3L.

B. The Extent to Which Voting is Racially

Polarized.

Within each challenged district racially polarized

voting is persistent, Severe, and statistically significant'

Mem. 0p. at 49-50. fn House District No. 8 it is so extreme

that, all other factors aside, no black has any chance of

winning. Mem. Op. at 57. To have any chance of electing

candidates of their choice, black voters must rely on single-

shot voting, thereby forfeiting their right to vote for a

fu1l sl-ate of candidates. Mem. Op . at 52.

C. The Use of the ttaj ority Vote neq .

North carolina has a majority vote requirement which

necessarily operates as a general, ongoing impediment to any

cohesive voting minority's opPortunity to elect candidates

of its choice in any contested primary. Mem. Op. at 38.

-5

Effects of Discrimination in Education,

Emplovment, and Health.

North Carolina has a long history of public and private

racial discrimination in almost all areas of 1ife. Segregatory

laws were not repealed until the late 1960's and early 1970's.

Public schools were not significantly desegregated until the

early 1970's. Thus, blacks over 30 years ol-d attended qualitatively

inferior segregated schools. Virtually al1 neighborhoods

remain racially identifiable, and past discrimination in

employment continues to disadvantage blacks. Black house-

holds are three times as likely as white households to be

below poverty level. The lower socio-economic status of

blacks results from the long history of dibcrimination,

gives rise to special group interests, and currently hinders

the group's ability to participate effectively in the

political process. Mem. Op. at 31-36.

E. Use of Racial Appeals in Political Campaigns.

From the reconstruction era to the present time, appeals

to racial prejudice against black citi zer:s have been used

effectively as a means of influencing voters in North

Carolina's political campaigns. As recently as 1983, political

campaign materials used in North Carolina reveal an unmistakable

intention to exploit white voters'existing racial fears and

prejudices and to create new fears and prejudices. Mem.

op. 38-40.

F. Extent of Election to Public Office.

The overalL extent of election of blacks to public office

at all leveLs of government is minimal in relation to the

percentage of blacks in the total populaEion, and black

candidates continue to be at a disadvantage. With regard

to the General Assembly in particular, black candidates have

been significantly less successful than whites. For example,

black candidates who have won Democratic primaries were three

times as likely to lose in the general election as were their

white Democratic counterparts. I4em. 0p. at 4L-42, 47.

The 1evel of participation of black citizens in the

political process is also minimal and is largely confined to

the relatively few forerunners who have achieved professional

D.

-6-

status or otherwise emerged from the generally depressed

socio-economic status which remains the present lot of the

great bulk of black citizens. Mem. Op. at 59.

G. Tenuousness of the Underlying State

Policy.

The poLicy was to divide counties when necessary to

meet population deviation requirements or to obtain Section

5 preclearance. Many counties, both those covered by Section

5 and those not covered by Section 5, vlere divided. The

specific dilution of black voting strength in the districts

chall-enged was known to and discussed in legislative deLi-

berations. The policy of dividing counties to resolve some

problems but not others justify districting which resul-ts

in racial vote dilution. Mem. 0p. at 63-64.

The policies behind the creation of Sentate DistricE

No. 2 were to protect the incumbent and to have the lowest

permissible sLze of black population which would survive

Section 5 preclearance. These do not outweigh a racial

dilution result. Mem. 0p. at 64.

In response to the District Court's findings, petitioners

challenge only one aspect of one of the findings of fact.

Petitioners challenge the level of severity, but not the

existence, of racially polari-zed voting.

These findings taken as a whole are more than adequate

to demonstrate that the District Court foll-owed the con-

gressional intent in analyzLng the facts of the case and

to support the ultimate finding of Ehe District Court that

the use of the multi-member districts in question and the

configuration of Senate District No. 2 have the result of

denying to respondents an equal opportunity to eleet candi-

dates of their choice.

III. Petitioners must Overcome the Presumption

that the District Court's Denial of

Petitioners' Application for a Stay is

Correct.

On February 9, 1984, the three judge District Court

unanimously denied petitioners' Motion for a Stay of the

-7-

injunction pending appeal. The District Court had before

it the memoranda of the defendant-petitioners which set forth

substantially the same arguments that the petitioners have

presented to this Court. The three North Carolina judges

are familiar with the districts in question, the time needed

to comply with the Court's Order, the election and political

process, and the normal election timetable in North Carolina.

Their determination that a stay is not warranted is entitled

to great deference in this Court. As Justice Powel1 stated

for the Court in Graddick v. Newman, 453 U.S. 928 (1981):

tAl Circuit Justice should show great

"reluctance, in considering in-chambers

stay applications, to subsiitute thisl view

for that of other courts that are closer

to the relevant factual considerations

that so often are critical to the proper

resol-ution of these questions. " 453 U. S.

at 934-935, citing Times-Picayune Pub.

Corp. v. Schulingkamp, 4L9 U.S. 1301-,

I3O5, (Powelll Circuit Justice, L974) and

Graves v. Barnes, 405 U.S. L20L, L203

@ Justice, L972).

This deference to the lower court gives rise to a pre-

sumption that the decision of the District Court on the proper

interim disposition of the case is correct. Rostker v. Gol-dberg,

448 U. S . 1306 , 1308 (Brennan, Circuit Justice , 1980 ) ; Inlhalen

v. Roe, 423 U.S. 1313, 1316 (Marsha1l, Circuit Justice, ]-975);

Breswick v. United States, 100 L.Ed. 1510, 1513 (Harlan,

Circuit Justice, 1955). In order to prevail on their

application, petitioners must overcome this presumption.

IV. Petitioners Have Not Met the Standard

for Granting a Stay Pending Appeal.

A single justice will grant a stay pending appeal on1-y

in extraordinary circumstances. Graddick v. Newman, 453 U.S.

at 933; Whalen v. Roe, 423 U.S. at 1316; Graves v. Barnes,

405 U.S. at L203; MaEInum v. Coty, 262 U.S. 1-59, 164 (1923).

"To prevail here the applicant must meet a heawy burden of

showing not only that the judgment of the lower court was

erroneous on the merits, but atso that the applicant will

suffer irreparable injury if the judgment is not stayed pending

appeal." Whalen v. Roe, supra at 1316.

-8-

Specifically, the petitioners bear the burden of demon-

strating each of the fo11-owing:

(A) Four justices will vote to note probable juris-

diction and that five jusEices are likely to conclude that

the case was erroneously decided below;

(B) Petitioners will- suffer irreparable harm pending

the appeal if the stay is not granted; and

(C) In balancing the equities, the harm to peLitioners

denying the sEay outweighs the harm to respondents and

the public interest of granting it. Rostker v. Gol-dberg,

U.S. at 1308; Graves v. Barnes, 405 U.S. at L203;

of

to

448

Re ublican State Central Comqrttee v. Ripon Soii .'

409 U.S. 1222, L224 (Rehnquist, CircuiL Justice, 7972).

A. Petitioners Have Not Established a

Probability That They Will Ultimately

Be Successful on the Merits of the

Aooeal.

The Memorandum opinion of the District court is a 7L

page careful, thoughtful and schol-arLy oPinion issued

unanimously by the District Court after receiving full-

briefing by the parties. Its findings of fact are thorough,

detailed and meticulous and were made after an eight-day

trial, and after receipt of voluminous materials including

depositions, exhibits, and stipulations of fact.

The unanimous opinion of the District Court, after ful1

consideraLion of the merits, is presumptively correcL.

Graddick v. Newman, 453 U.S. at 933; Rostker v. Gold-berg,

U.S. at 1308; Whalen v. Roe, 423 U.S. at 1316; Graves v.

448

Barnes,

405 U.S. at L20Z-L203.

While petitioners attempt to suggest thaE the acLion raises

novel- questions of 1aw concerning the amendment of Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act, in fact there is littl-e new in the Dis-

trict Court's approach. The District Court's Opinion indicaLes

that the District Court used the analytic framework of White v.

Regester, Supra and its progeny. Petitioners do not argue that

it was appropriate to follow that line of cases, or to util-ize the

factors listed on pages 28-29 of the SenaEeReport. Instead, with one

-9-

exception petitioners suggest questions which deal exclusively

with the proper application of established case law to the

-!-tfacts of this case.

None of the four questions raised by the petitioners

is sufficient to suggest that this Court will reverse on the

5l

merits. -

L. Section 5 preclearance does not preclude Section 2

Review. House District No. 8 and Senate District No. 2 con-

tain counties which are covered by Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act and were precleared by the Attorney General of

the United States. Petitioners assert that this Section 5

preclearance has a collateral estoppel effect on respondents

with regard to their claim under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act. Petitioners cite no authority to supPort their

position except Morris v. Gressette, 432 U.S. 49L (L977).

The court in Morris v. Gres_get'lg, El1pfa, did not hold that

Section 5 preclearance precludes independent Section 2 review.

Instead, the Court held that a private Party can not seek

District Court review of the Attorney General's action under

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. In fact, in addressing

a parallel issue to the issue raised here by petitioners,

the Court rejected the claim. "Where the discriminatory

character of an enactment is not detected uPon review of the

Attorney General, it can be challenged in traditional con-

stitutional litigation." 432 U.S. at 506-07.

The District Court noted that two critical elements

of collateral estoppel are lacking in this instance. First,

the Attorney General's determination was made in a non-

adversarial administrative proceeding to which respondents

were not a party. Second, the standard by which the Attorney

4 I The single exception is the qugstion of whether Section

5 precl-earance-has coliateral estoppel ,effect in a Section 2

prbceeding. This question is discussed in Part IVA.1, infra.

5 / Petitioners state that the standard for determining

th6-appropriateness of a stay is whether-any of the matters

proporla to be raised "are oi such significance and difficulty

th"t there is a substantial prospect that they will .command

four votes for review." Rpplication at p. 2. Petitioners

cite for this proposition Gra,e-q-tf.-tgmg", 405..!'-S' l-29L (L912)

F"titionei6-omLi-'tr[;-imporffice t "Of equal

importance in cases presented on direct appeal --where we lack

discretionary power to re{use to decide the merits is the

iefatea qrr".Lib.t whether five justices are likely to conclude

that the case was erroneously decided below." Id. at L203'

-10-

General assesses voting charges under Section 5 are different

from those by which judicial claims under Section 2 ate to

be assessed. See Mem. Op. at 68-69 and citations therein.

Moreover, Section 5 exPressly provides that the Attorney

General's failure to object to a voting change pursuant to

Section 5 does not pretermit a subsequent challenge.

"Neither an affirmaLive indication by the Attorney General

that no objection will be made, nor the Attorney General's

failure to object sha1l bar a subsequent action to

enjoin enforcement of such qualification, prerequisite,

standard, practice, or procedure." 42 U.S.C. S1973c.

In view of the express statutory provision contemplating

a de novo action, the lower court correctly denied the

petitioners' cl-aim that the preclearance had a collateral

estoppel effect in this case. Mem. Op. at 68-69. Accord,

United States v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 594

F .2d 56, 59 n. 9 (5tlr Cir. 1979) ; Ma.ior v. Treen , 574 F. Supp.

325, 327 n.L (E.D.La. 1983) (three judge court) .

As there is no authority to supPort petitioners' con-

tention, it is not likeIy that this Court will conclude that

6/

the District Court is in error in this regard.

2. The District Court did not err in applying the

standard for finding a violation of Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act.

Petitioners assert that the District Court erred as a

mattser of 1aw because it "concl-uded that because the election

of blacks to the GeneraL Assembly in the challenged districts

was not guaranteed, Secton 2 had been violated." Application

at p. 4.

This assertion is a gross distortion of the District Court's

analysis of the facts. The Distri.ct Court assessed each of the

factors suggested by Congress and their interaction with each

other before concluding that, under the totality of the cir-

cumstances, the challenged districts had a discriminatory result.

6 I Even if the Court were to so rule, the ruling would affect

onTt House District No. 8 and Senate District No. 2 and not any of

the other five districts in question.

- 11-

This assertion further ignores the extensive discussion

of the District Court as to the meaning of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, Mem. 0p. at 8-21, and its explicit state-

ment that, "In determining whether, 'based on the totality

of circumstances, ' a staters electoral mechanism does so

'resuLt' in raciaL vote dil-ution, the Congress intended that

courts should look to the interaction of the challenged

mechanism with those historical, social and political factors

generally suggested as probative of dilution in W-hite v.

Regester l4L2 U.S. 755 (1973)l and subsequently elaborated

by the former Fifth Circuit in Zinrner v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d

L297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff 'd on other grds. sub.. ngg.

East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636

(L976) (per curiam)." Mem. 0p. at L4. See also Mem. Op. at

L7, "[T]he fact that blacks have not been elected under a

challenged districting plan in numbers proPortional to their

percentage of the population Idoes not alone establish that

vote dilution has resultedl . "

Thus petitioners have miscast the analysis of the District

Court and then have complained that their distorted inter-

pretation, not the District Court's actual analysis, was an

error of law.

The District Court thus clearly and exhaustively examined

the totality of the circumstances by assessing each of the

factors suggested by Congress in the legislative history.

In contrast to the District Court's complete and extensive

findings of fact, petitioners have focused on isolated facts,

taken out of context, to suPport its proposition that the

District Court required "guarantees" or "safe seats."

Petitioners focus on electoral success in Forsyth County

to demonstrate their point. They ignore electoral f ailures

such as (f) the uniform defeat of appointed black incumbents

which resulted in no blacks being elected to the House of

7l

Representatives from Forsyth County in L978 and 1980; (2)

7 / The evidence showed that

the General Assembly and ran

blacks who were appointed to

bids for election at the end

while blacks who were elected to

as incumbents were successful, all

the General Assembly lost their

of the appointed term.

-L2-

the defeat in 1980 of the black who had been elected to the

County Commission in L976 which resulted in a return to an

all white County Commission; and (3) the defeat in 1978 and

1980 of the black who had been elected to the Board of

Education in L976 returning the Board of Education to its

previous all white status in 1978.

Furthermore, the District Court concluded that 1982 was

"obviously aberrational" and that whether or not it will be

repeated is sheer speculation. Among the aberrational factors

was the pendency of this lawsuit and the one time help of

black candidates by white Democrats who wanted to defeat

single member districts. Mem. Op. at 47. This skeptical

view of post-litigation electoral success is supported by

the legisLative history of the Voting Rights Act and the case

law. Senate Report at 29, n.l-l-5; Zinnner v. McKeithen, 485

F.2d at 1307; NAACP v. Gadsden Co. School Board, 69L F.2d

978, 983 (l1th Cir. L982).

The DistricL Court didnot, ss suggested, require a

guarantee of election, but instead examined the whole pattern

of election :Ln Forsyth County and elsewhere. For examPle,

Mecklenburg County, which is big enough to have two majority

black House Districts out of eight seats and one majority

black Senate District out of four seats has this century

elected only one black senator (from L976 to 1979) and one

black representative (in L982, after this lawsuiL was filed).

Mem. Op. at 43. House District No. 8 which is 397" bLack

and has four representatives has never elected a black

representative. Mem. Op. at 45

After noting the black successes and the black failures,

the District Court concluded, "IT]he success that has been

achieved by black candidates to date is, standing a1one, too

minimal in total number and too recent in relation to the long

history of complete denial of any elective oPportunities to

compel or even arguably to support an ultimate finding that a

black candidate's race is no longer a significant adverse

factor in the political processes of the state either

-1 3-

generally or specifically in the areas of the challenged

districts. " Mem. OP. at 47 -48 -

Rather than requiring guaranteed election, and rather

than simplistically considering erratic examples of

electoral success alone, the District Court properly con-

sidered Lhe extent of election as one factor in the totality

of circumstances leading to its conclusion of discriminatory

result.

As Petitioners have misstaterl the standard actually applied

by the District Court, they have not demonstrated a likelihood

of ultimate success on appeal in this regard.

3. The District Court was not clearlv erroneous in

determining that there is severe and persist

pol-arized voting in the districts in question.

Of the six factors set out by Congress which the District

Court determined existed in this case, petitioners question

on1-y one finding of fact: that elections in the challenged

districts were marked by severe and persistent racially

polarLzed voting. Application at 5. Petitioners do not

deny the existence of racially polatLzed voting but differ

with the three judges' determination of the degree of polarLza-

tion. The standard for assessing petitioners' likelihood of

success on this issue is that the District Court's findings

of fact will not be reversed on appeal unless they aTe clearly

erroneous. Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 281 (1982)

Rule 52(a), F.R.Civ.P. Petitioners limit this argument to the

8/

four districLs not covered by Section 5.- Application at p. 6.

Petiti-oners support their argument with examples from one

post-1-itigation el-ection year, L982, ignoring the data from

1980 and L978.

In addition, the data listed by petitioners is misleading

and deceptively out of context. For example:

(f) Peritioners point out that in the L982 Mecklenburg

House primary, black candidate Berry received 502 of the white

8/ PeEitioners have apparently miscounted. There are

actiially five districts not covered by Section 5 which are

subject to the DistricE Court's Order: House DistricE Nos.

39 (Forsyth), 36 (Mecklenburg), 23 (Durham) and 2L (Wake) and

Senate District No. 22 (Mecklenburg and Cabarrus).

-14-

vote. The District Court noted this stating that it "does

not alter the conclusion that there is substantial racially

polarized voting in Mecklenburg county in primaries. There

were onl-y seven white candidates for eight positions in the

primary and one black candidate had to be elected. Berry,

the incumbent chairman of the Board of Education, ranked first

among black voters but seventh among whites." Mem. Op. at 53

(2) Petitioners point ouE that in the 1982 House election

in Durham County, bLack candidate Spaulding received votes

from 477" of the white voters and won. Petitioners fail to

note thaE in the Lg82 general election there was no Republican

opposition, and spaulding was, for a1-1 practical purposes,

unopposed. Thus a majority of white voters failed to vote

for the black incunrbeng even when Lhey had no other choice.

Mem. Op. at 55

(3) Petitioners point to Dan Blue's electoral success

in Wake County but fail to note that in primaries 60i: to

807. of white voters did not vote for the black candidate

compared to 767" and 807. of black voters who did. Mem. op.

at 56.

(4) Petitioners point out that in Forsyth county the

two black candidates in 1982 were successful but fail to

note that white voters ranked the two black candidates

seventh and eighth out of eight candidates in the general

election while black voters ranked them first and second'

Mem. Op. at 54

(5) As a final example, while noting that black elected

incumbents have been re-e1ected, petitioners fail to note

that black Democratic candidates who survive the primary are

only one-third as 1ike1y as white Democrats to win in the

general

,

elections.

Thus, petitioners focus on bits and pieces of evidence

taken out of context. Petitioners do not, as is required,

examine the record as a who1e. The three judges who heard

the evidence did consider each of the facts which petitioners

-15 -

point out, together with the surrounding circumstances,

and concluded that these pieces did not alter the conclusion

of severe and persistent racially poLarized voting. This

conclusion is not clearly erroneous.

Petitioners erroneously claim that the District Court

determined racially polarization by labeling every election

in which less than 507" of the whites voted for the black

candidate as racially polarLzed. A1-though it is true that

no black candidate, whether or not opposed and whether or

not an incumbent, ever managed to geL Votes from more than

507. of white voters, this is not the standard the District

Court used.

Instead, the Distric! Court based its ultimate conclu-

sion of severe and Persistent racially po1-arized voting on

an exhaustive analysis of the evidence. The District Court's

assessment can be summarized in three findings:

1. The correlation between the race of the voter and

the race of the eandidate voted for was statistically

significant at the .00001 level- in every election analyzed.

Although correl-ation coefficients above an absolute value

of .5 aTe relatively rare and those above ,9 aTe extremely

rare, aLl correl-ation coefficients in this case were between

.7 and .98 with most above .9. Mem. Op. at 50 and n.30.

2. In all but two elections the degree of polarization

was so marked that the results of the election would have

been differenE depending on if it had been held among only

white voters or among only black voters. The two exceptions

were elections in which black incumbents were re-e1ected,

one unopposed, and neither receiving votes from a majority

of the white voters. The Court accePted respondentsr expert's

use of the term "substantively significant" in these circum-

stances. Mem. Op. at 50 and n.31. Although petitioners'

expert disagreed with this definition, he offered no alterna-

tive definition supported either by case 1aw or political

science literature. Mem. Op. at 51, n.32.

-L6-

3. The District Court considered voting patterns to

support its conclusion of severe racial poLatization as

follows:

On the average, 8L.72 of white voters did

not vote for any black candidate in the

primary elections. In the general elec-

tions, white voters al-most always ranked

black candidates either l-ast or next to

last in the multi-candidate field except

in heavil-y Democratic areas; in these

latter, white voters consistently ranked

black candidates last among Democrats if

not last or next to last among a1l can-

didates. In fact, approximately two-

thirds of white voters did not vote for

black candidates in general elections

even after the candidate had won the

Democratic primary and the only choice

was to vote for a Republican or no one.

Black incumbency allevi-ated the general

leve1 of polarization revealed, but it

did not eliminate it. Some black incum-

bents were reelected, but none received a

majority of white votes even when the

election was essentially uncontested.

These findings are more than adequate to support

conclusion

polarized.

that voting in the districts in question is

This Court is not 1ike1y to conclude that the

the

racially

finding

is clearly erroneous.

4. The District Court did not erroneousl ect the

State I s evidence.

Petitioners claim that the District Court erroneously

concluded as a matter of 1aw that certain elements of the

State's evidence were not relevant. Application at p. B.

Without citing the opinion below, P€titioners give three

examples of factors they claim the Court failed to consider.

In fact, the District Court specifically admitted' considered,

and weighed each of the Stage's evidentiary points, and did

not summarily rejecg them as a matter of 1aw. In essence,

petitioners are complaining of the weight given Lhese factors

by the District Court in making its findings of fact.

Petitioners claim that the lower court, as a matter of

law, improperly rejected their evidence (1) that some black

voters did not support the respondents' allegations , (2) that

some black and white politicians who testified for the State

were opposed to respondents' claims, and (3) that recently

there has been some increase in the ability of blacks to

participate in the state's political processes. Application

at p. 8. In fact, the District Court carefully evaluated the

-L7 -

State's evidence on each of these points. With regard to the

first contention, the Court considered the testimony of all the

State's witnesses, including the putative members of the plain-

tiff class and, although noting that they were a "distinct

minority" within the plaintiff class as certified, acknowledged

"their experience, achievement and general credibility as wit-

nesses." Mem. Op. at 60. The Court further noted that even the

State's witnesses did not deny the present existence of vote

dilution but simply disagreed with the remedy. Mem. Op. at 60-61.

The Court also considered the other two factors mentioned

by petitioners. It noted that in some, but not all areas of the

State an "increased willingness on the part of influential white

politicians" to support the candidates of some minority group

members, and a "measurable increase" in the ability of some

black ciEizens to participate in the State's political processes.

Mem. Op. at 58-59.

What the Court did not find was that any or all of these

developments were sufficiently pervasive or strong to overcome

its finding that the leve1 of political participation of black

citizens was stil1 minimal and that their voting strength was

being diluted in each of the challenged districts. Id. The

District Court found, on the factual record made in this action,

an identifiable black community whose "ability to participate"

and "freedom to elect candidates of its choice" (emphasis in

original) is diminished by the challenged legislative districts.

Mem. Op. at 60-61. Following the Congressional determination

Ehat such dilution constituted a violation of Section 2, the

District Court properly weighed the State's evidence in its

factual findings before concluding that a violation of Section

2 was established.

Since petitioners have not established that the District

Court erroneously failed to consider its evidence, this argument

is not sufficient to cause this Court to reverse on appeal.

Because petitioners have

the District Court's 0rder is

shown no basis for concluding

on the merits, the application

not overcome the presumption that

correct on the merits, and have

that the Court is likely to reverse

for a stay must be denied.

-18-

B. Petitioners Have Failed to Show

That They Will be lrreParablY

Harmed if a StaY is Denied.

In assessing whether or not there is sufficient irreparable

injury to justify staying the injunction of the District Court,

it is particularly appropriate for the Circuit Justice to defer

to the judgment of the lower court judges who are closer to

the facts. The District Court's refusal to grant a stay

indicates Ehat it was not sufficiently persuaded that irre-

parable harm would result from the enforcement of the judgment

in the interim. whalen v. Roe , 423 U.S. at L317, citing

Graves v. Barnes, 405 U.S. at L203'L204'

This is particularly true when, as here, a three judge

court has given careful consideration to the motion and has

denied it unanimouslY.

Petitioners make two arguments to show that they will be

harmed if a stay is not granted. The first is that the injunc-

tion will interrupt and cause confusion in the 1984 elections

for the General Assembly. The second is that defendants' com-

pliance with the injunction will foreclose the possibility

of a meaningful appeal. Neither of these arguments is adequate

to require that this Court stay its injunclion'

1.

undulv disrupt the 1984 election.

The Court stated in Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (L964),

"[O]nce a State's legislative apportionment scheme has been

found to be unconstitutional, it would be the unusual case in

which a court would be justified in not taking appropriate

action to insure that no further elections were conducted under

the invalid plan." 377 U.S. at 585'

Petitioners offer no evidence or facts in support of the

assertion that requiring them to comply with the District

Court's Order would make the 1984 elections chaoLic. To the con-

trary, the election is not only not imminent, it is hardly under-

way. The general election is scheduled for November 2, 1984' The

injurrcEion was entered on January 27, t984, before the candidate

liance with the District Cour!-lrder

- 19-

filing period ended on February 6, 1984. Counsel for petitioners

has informed counsel for respondents that the State Board of

Elections plans to reopen candidate filing, at least in the

districts in question, whether or not a stay is granted because

some candidates who knew of the court's injunction may not have

filed. No one can even know who the candidates are.

The District Court's Order gavepetitioners almost two

months to devise a new districting method. This is more than

ample time.

Petiticners conpiliation of the data necessary to comply

with the District Court's Order is now complete. See Letter

of February L4, L984 from Gerry F. Cohen, Director of Legisla-

tive Drafting, to Representative Frank W. Ba11ance, Jr. atEached

as Exhibit A. Thus, the State , Lf it wants to, has time to

redistrict before the Court's March L6, f984 deadline.

If a new plan is adopted by March 16, 1984, the election

will not be unduly delayed. In 1982, the General Assembly did

not finally enact its redistricting until April 27, LgB2, and

planned to have a primary on June 10, 1982. On objection of

the United States Attorney General, the primary date was moved

to June 29, L982, Lwo months after the plan was enacted, and

general elections were held on schedule in November. (Stipula-

tions of Fact 42-47)

Thus, there is adequate time for the State to comply with

the District Court's Order, hold primary elections, and hold

the general election in November, 1984, all in an orderly

f ashion.

This Court has refused to stay i-njunctions which prohibited

the use of i1lega1 or unconstitutj-onal districting or apportion-

ment plans even when elections were c1ose. See Busbee v. Smith,

549 F.Supp . 494 (D.C. D.C . 1982) (Georgi-a Congressional

Reapportionment), applications for stays denied, U.S.-,

A-95 (Brennan, Circuit Justice; Stevens, Justice, L982) (letters

of Supreme Court Clerk attached as Exhibits B and C); trIise v.

Lipscomb, application for stay denied, 434 U.S. 935 (Mem. L977)

-20 -

rev'g 434 U.S. L329 (Powel1, Circuit Justice, L977 ) (appli-

cation for stay granted) (Dal1as City Council Structure);

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F.Supp.704,737 (W.D. Tex. L972) (Texas

Housing Representatives), application for stay denied, 405 U.S.

1201 (Powell, Circuit Justice, 1972) ; Mahan v. Howe11, 330

F.Supp. 1138 (E.D. Va. 197f) (three judge court), application

for stay denied, 404 U.S. 1201 (B1ack, Circuit Justice, 1971)

(Virginia General Assembly apportionment) .

Petitioners claim that the need for Section 5 preclearance

will further interfere with their ability to comply with the

Court's Order. This does noL justify a delay in compliance

in House Districts 2L,23,36 and 39 or Senate District No. 22

which can be subdivided without affecting counties covered by

Section 5 and without Section 5 preclearance. Even for House

District 8 and Senate District No. 2, the State can, as it did

in L982, request expedited review by the United States Attorney

General under 51 C.F.R. S51.32. In 1982, the Attorney General

issued its letter preclearing the April 27 apportionments on

April 30. (Stipulation of Fact No. 45) If preclearance should

cause a problem, then the District Court has the power to order

the use of an interim remedy. Revnolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. at

586. Thus, the need for preclearance does not make it impossible,

or even impraetical for the State to comply with the Court's

Order.

Petitionershave not born the burden of showing that

compliance with Ehe District Court's Order will unduly disrupt

the orderly processes of holding 1984 elecLions and have not,

therefore, established irreparable harm.

2. A stav is not needed to preserve the State's right

to a meaningful appeal.

Petitioners' second claim of irreparable harm is that com-

plying with the District Court's Order will make an appeal

meaningless because it will irreversibly alter the political

landscape. Application at 9. Petitionerssupply no facts to

support this conclusory statement.

-2L-

The argument that holding an election under a districting

plan which compl-ies with the District Court Order would irrevo-

cably al-ter the political landscape was raised and rejected in

Wise v. Lipscomb, appl-ication for stay denied, 434 U.S. 935

(Mem. L977) , rev'P, 434 U. S. L329; l-334 (Powell-, Circuit Justice,

L977). If this argument $/ere accepted, then stays would have

to be granted in all apportionment cases in which an election

might be held whil-e the appeal is pending. This has not been

the practice. See cases cited at Pp. 20-2L, supra.

Petitioners attempt to bolster this argr:ment by suggesting

a stay should be granted because novel questions are raised.

This case does not raise noveL issues but is simply the

application of a clearly deLineated Congressional scheme to

the facts of this Particular case using much the same method

of inquiry used by District Courts since this Court decided

White v. Regester, supra, a decade ago.

Nor do the cases cited by petitioners support the position

either that the mere existence of an unresolved question warrants

a stay on appeal or that the holding of an election during an

2/

appeal requires a stay.

Although the opinion on the merits in Georgia v. United

States, 4Ll U.S. 526 (L973) refers to the novelty of the question

at hand, there is nothing in the opinion or in the order granting

the stay which suggests the circumstances under which the stay

was granted or the reasons for its issuance. (See Orders grant-

ing stay and denying application to vacate stay, Georgia v.

United States, A-1106 (412L172 and 5 /5/72), attached hereto as

Exhibit D). Oden v. Brittain, 396 U.S. L2L0, L2LL-2 (1969),

arose in a completely different context. No relief had been

granted bel-ow and plaintiffs sought a preliminary injunction.

Justice Bl-ack denied plaintiff's motion for an injunction Eo prevent

holding an eLection not because there was a legal question unresolved

9 / The presence of a

quirement for granting

hood that five justices

405 U.S. at L203.

novel question would not meet the re-

a stay which is that there is a l-ikeli-

will vote to reverse. Graves v. Barnes,

-22-

by the Supreme Court but primarily because the lower court had

neither considered the merits of the case nor ruled on the

motion for an injunction. Plaintiff had not exhausted the

possibility of obtaining relief from the DistricL Court. In

contrast, in this instance, not only has the District Court

ruled against petitioners on the motion for a stay but the

District Court has ruled against petitioners on the merits.

In six of the seven challenged districts, the District

Court's Order requires a simple subdivision of existing

legislative districts without affecting surrounding districts.

In the unlikely event that the District Court's Order is

reversed on appeal, it would be a simple matter to recombine

these subdivided districts. There is no reason why the General

Assembly cannot enact a plan in compliance with the District

Court's Order and, if the Order j-s reversed on appeal, revert

to the use of Chapters 1 and 2 of the North Carolina Session

t0l

Laws of the L982 Second Extra Session for the 1986 election.

C. The Irreparable Harm to Respondents

and the Injury to the Public Interest

of Granting a Stay Outweigh any Possi-

ble Harm to Petitioners of Denying a

S tav.

In acting on an application for a stay, a Circuit Justice

should "balance the equities and determine on which siCe

the risk of irreparable injury weighs most heavily. "

Graddick v. Newman, 453 U.S. at 933, quoting Holtzman v.

Schl-esinger , 4L4 U. S. 1304, 1308-09 (Marshall, Circuit Justice,

Lg73). In this case both the irreparable harm to respondents

of granting a stay and the public interest require that the

application for a staY be denied.

-Lgl In order to be entitled to a s-tay_pending lPPeal pgti-

tioners must show that compliance with the District Court's Order

will cause imminent irreparable harm, that is, before this Court

can rule on petitioners'-jurisdictional statement. ChaEEer 9f

Comr4erce v. Legal Aid Soc , 42? U.S. 1309 (Douglas, Circuit

dqrgl-lgYiles & Loan v. Federal Home

Loan Bank of San Francisco

t frstice, 1955) .

It is within petitioners' power to docket the appeal-and- file

its jurisdictional statement immediately. Respondents will then

have"3O days to respond. Rule 16.1, Supreme Court Rules. It is

thus quiie'po""iUfe'that the Court could act on the jurisdictional

statement, perhaps sununarily affirmlng, before even th-e prim3ry

election tra^s Ueen held. Beciuse petitioners have not shown the

imminence of ""V

po"sible injury, they have not established irre-

parable harm.

_23-

The starkly simple and obvious injury to respondents of

granting a stay is an addiEional Ewo years of denial of equal

opportunity to elect representatives of their choice. The

District Court found that respondents have less opportunity

than do other members of the electorate to participate in

the political process and to elect representatives of their

choice. Mem. 0p. aL 65-66. This dilution of voting strength

is, in part, the result of more than 70 years of intentional

disfranchisement. Id. at 65. The continuation of this vote

dilution is irreparable; there is no adequate remedy for its

denial.

The injury to respondents is exactly what Congress intended

to prevent in enacting the Voting Rights Act Amendments in 1982.

In anending Secti.on 2 of the Voting Rights Act, Congressrs

purpose was to increase minority participation in the political

process by eliminating election methods that deny minority voters

an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. Maior

v. TEee4, 574 F.Supp. 325, 343 (8.D. La. 1983) (three judge

court); Senate Report at 193 (additional views of Sen. Dole).

As Senator Moynihan said on the floor of the Senate, "Our

goal was to achieve enactment of the strongest Possible bipartisan

measure . to reaffirm this Nation's commitment to that most

basic and fundamental guarantee which is the right of every

citizen to exercise his or her right to vote for those who would

represent them in Government." 128 Cong. Rec. S. 67L6, 6718

(Daily ed. June L4, L982) (Remarks of Sen. Moynihan).

Congress not only intended to eliminate racial vote dilution,

but aLso it intended to do so effective immediately. After

extensive hearings and testimony documenting the persistent

problem respecting minority voting rights 16 years after the

initial enactment of the L965 Voting Rights Act, Congress con-

cluded, by overwhelming margins, that the federal courts must

intervene to address existing conditions of racial vote dilution.

Ma.i or v. Treen, 57 4 F. Supp. at 346-47 .

-24-

As Senator Moynihan remarked, "[T]he iSsue of voting

rights is an issue that was with us over four or five genera-

tions and now into the sixth one, scarcely precipitous in our

conduct and not altogether admirable in our willingness to be

patient. There are some things concerning which patience is

scarcely a virtue and after a point concerning which patience

becomes a form of avoidance." L28 Cong. Rec. S. 67L7 (Daily ed'

June 14, tg82) (Remarks of Sen. Moynihan) .

This legislative history demonstrates not only the public

interest in immediate remedies of violations of Section 2 but

also points to the vital importance to resPondents of the

rights which are at stake.

This Court has also repeatedly recognized that the right

to use one's vote effectively is fundamental to democracy and

of paramount significance. Revnolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533,

555 (1964); Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886). As

stated by this Court in Reynolds v. Sims,377 U.S. at 555:

The right to vote freely !or- the candi-

date of one's choice is of the essence

of a democratic society, and any restric-

tions on that right strike at the heart

of rePresentative government.

Denying to voters the opportunity to select candidates of

their choice has also been recognized by this Court to be

irreparable harm. MatLhews v. Little, 396 U.S. L223 (B1ack,

Circuit Justice , L96g) (denying stay in candidate filing fee

case). once 1ost, it simply cannot be recovered.

If the election is held under the current at large system,

respondents will be irreparably harmed by being denied an equal

opportunity to participate effectively in the election- on

the other hand, if the multi-member districts are subdivided

in a way that eliminates the discriminatory resul-t, no one

will be irreparably harmed by having elected representatives

LLI

from smaller districts. Everyone will still be representeil

lL/ Petitioner suggests that respondents will not be harmed

by hotting- eiections .rnE6r the p-Ian which the District Court deter-

mined is fttegat because four oi the six districts in qugstion !t3r.

black incumbeii" ,f,o will probably be elected. Application at 11.

In fact, ifl o.t1y tro of the seven districtg-in-question did incum-

bents fite for reelection. The other two black -incumbents filed

for other offices.

-25-

Because the continuation of a discriminatory redistricting

system is an affront to the public policy, as exPressed by

Congress, because delaying the right to use ones vote effec-

tively is the denial of a fundamental right in a democracy,

and because no one will be harmed by the use of subdivided

legislative districts, the application for a stay should be

denied.

V. Conclusion

Delaying respondents' opportunity to have an equal oPpor-

tunity to elect representatives of their choice to the North

Carolina General Assembly will cause respondents the irreparable

harm of denying their effective participation in representative

democracy. Balanced against this is, at worst, the inconvenience

to petitioners of eomplying with the District Court's Order

in an expeditious manner. Since the harm to respondents of

granting a stay clearly outweighs the harm to petitioners of

denying it, since petitioners have shown no likelihood of reversal

on appeal, and since the public interest is in immediate eradica-

tion of the vestiges of disfranchisement of black citizens, the

Application for a Stay should be denied.

This .Ab{+-eay of February, 1984.

CHAMB

SLIE J. WINNER

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, llallas

& Adkins, P.A.

951 S. Independence Boulevard

Suie 730

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

7 o4 I 37 5- 8461

JACK GREENBERG

LANI GUINIER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Attorneys for Respondents

-26-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served the foregoing RESPONDENTS'

MEMORANDIJM IN OPPOSITION TO THE APPLICATION TO STAY THE

},IANDATE OF THE I]NIIED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN

DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA on aLl orher parties by placing

a copy thereof in the post office or official depository

in the care and custody of Ehe United States PostaL service

addressed to:

James Wallace, Jr.

Deputy Attorney General for

Legal Affairs

North Carolina Department of

Justice

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Arthur Donaldson

Burke, Donaldson, Holshouser &

Kenerly

309 N. Main Street

Salisbury, North Carolina 28L54

Kathleen Heenan

Jerris Leonard & Associates, P.A.

900 LTth Street, N.W., Suite L020

Washington, D.C. 20006

Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

20L West Market Street

Post Office Box 3245

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

ThisJS_d"y of Februlry, 1984.

-27 -