Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier; Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jackson Court Opinion; United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Court Opinion

Working File

July 13, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier; Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jackson Court Opinion; United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Court Opinion, 1984. fecf58e6-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e989d3bf-76e0-4546-8964-d1546c8cc416/memorandum-from-gibbs-to-guinier-monroe-v-board-of-commissioners-of-the-city-of-jackson-court-opinion-united-states-v-scotland-neck-city-board-of-education-court-opinion. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

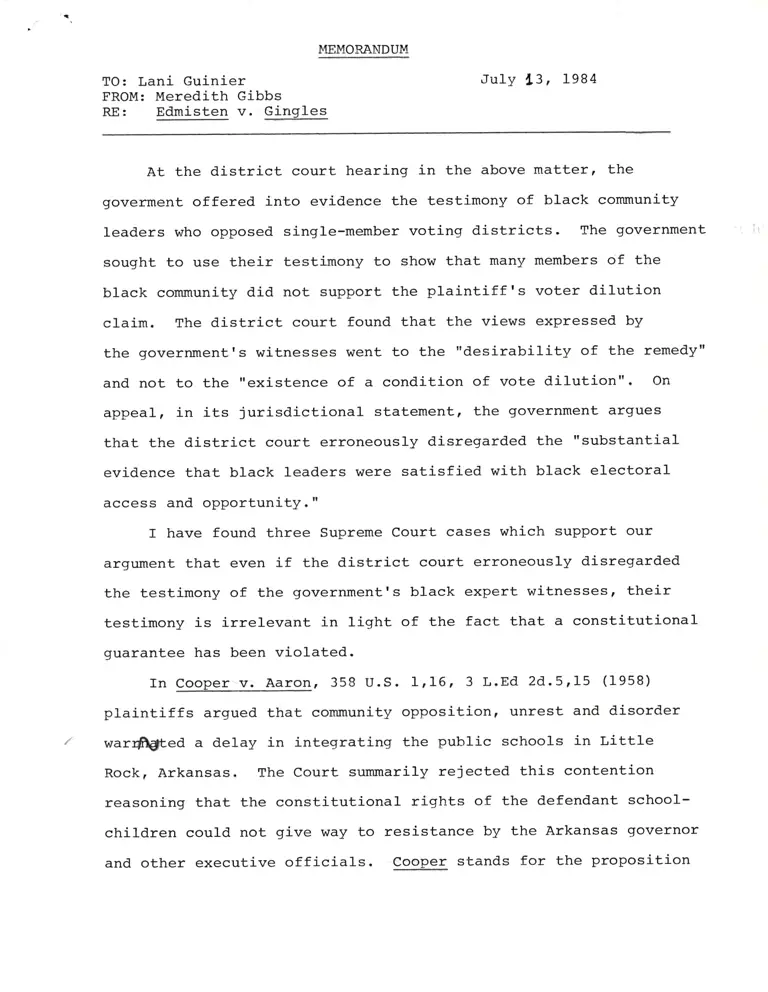

MEMORANDUM

TO: Lani Guinier

FROM: Meredith Gibbs

RE: Edmisten v. Gingles

July 1.3, 1984

At the district court hearing in the above matter, the

goverment offered into evidence the testimony of black community

leaders who opposed single-member voting districts. fhe government

sought to use their testimony to show that many members of the

black community did not support the plaintiff's voter dilution

claim. The district court found that the views expressed by

the government's witnesses went to the "desirability of the remedy"

and not to the "existence of a condition of vote dilution". On

appeal, in its jurisdictional statement, the government argues

that the district court erroneously disregarded the "substantial

evidence that black leaders were satisfied with black electoral

access and opportunity. "

I have found three Supreme Court cases which support our

argument that even if the district court erroneously disregarded

the testimony of the government's black expert witnesses, their

testimony is irrelevant in light of the fact that a constitutional

guarantee has been violated.

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1r16, 3 L.Ed 2d-5 rL5 (1958)

plaintiffs argued that community opposition, unrest and disorder

warfig;ted a delay in integrating the public schools in Little

Rock, Arkansas. The Court summarily rejected this contention

reasoning that the constitutional rights of the defendant school-

children could not give way to resistance by the Arkansas glovernor

and other executive officials. Cooper stands for the proposition

that individual or community opposition to a proposed court or

legistative mandate will not override the vindication of a

federal constitutional guarantee.

In U.S. v; Sgotland l{eck City Bd. of'9d., 407 U.S. 484t49L,

33 L.Ed.2d 75,81 (L972) the Court held that "white flight"r dD out-

ward and obvious denonstration of community opposition to school

desegregation, is an invalid justification for disregarding a

constitutional mandate to completely uproot a dual school system.

In that case, the North Carolina legislature enacted a statute,

Chapter 31, authorizing the creation of a new school district

which, in effect, created a refuge for white students to avoid

desegregation. One of the school board's main arguments in support

of Chapter 31 was that it was necessary to avoid "white flight"

into private shcools by Scotland Neck residents. Affidavits were

introduced into evidence at the district court hearing documenting

the degree of "white flight" since the inception of a unitary

school p1an. The court was unswayed by this evidence of community

resistance; such evidence being analogous to the evidence in our

case of black comrnunity opposition to single member districts.

Similarly, in-Mo+roe'v.:Bd: o-f Commissignersr 391 U.S. 4501

20 L. Ed. 2d 7 33 t7 39 Ogl2l the court re j ected the school board' s

argument that its free transfer p1an, which permitted students

to transfer to another school within their attendance zone, was

necessary in ord.er to prevent white student's from fleeing the

school system. Citing-Brown II, the court stated that "it

should go without saying that the vitatity of these constitutional

principles cannot be allowed to yield simply because of dis-

agreement with them."'Id, at 739

733

,'BRENDA

".

;8ii*'dttt"T ,r., Petitioners,

v

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY

OF JACKSON, TENN., et al.

391 US 450,20 L Ed 2d 733, 88 S Ct 1700

lNo. 7401

Argued April 3, 1968. Decided May 27, 1968.

SUMMARY

This case, a companion case to Green v County School Board of New

Kent County supra, p. 716, and Raney v Board of Education of Gould

School District, supra, p. 727, similarly presents the question whether

a school board's "free-transfer" plan, which permits a child, after regis-

tering in his assigned school in his attendance zone, to freely transfer to

another school of his choice if space is available, is adequate to comply

with the board's responsibility to effectuate a transition from a racially

segregated school system to a racially nondiscriminatory system. The

school system in question consisted of eight elementary schools, three

junior high schools, and two senior high schools. Under the former state

law, five of the elementary schools, two of the junior high schools, and

one of the senior high schools were operated as "white" sehools, and the

remainder of the schools were operated as "Negro" schools. [n an action

by Negro children arising out of the administration of such "free-transfer"

plan, the United States District Court for the Western District of Ten-

nessee approved the plan in its application to the junior high schools,

but not in its application to the elementary schools. (244 F Supp 353.)

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed, except

on an issue of faculty desegregation, as to which the case was remanded

for further proceedings. (380 F2d 955.)

On certiorari, the United States Supreme Court vacated the judgment

of the Court of Appeals insofar as it affirmed the District Court's approval

of the plan in its application to the junior high schools, and remanded the

case for further proceedings. In an opinion by BnrNNlN, J., expressing

the unanimous views of the court, it was held that the "free-transfer"

plan was inadequate to comply with the school board's responsibility to

effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school system, where,

3 school years after such approval by the District Court, the "Negro"

tlt.

1'

'i

l

i

$

:.

:

r

]IONROE v BOARD OF COMIIiSSIONERS 736

3eiG rso' io L Ed 2d ?33' 88 s ct 17oo

still almost all white' Inie"' of tne some'cirtumstances-as effectuating a

piaht elementary ..tuoi.'^r*re- still transition from a racially segregated

"tienaea

only b1' Xtg''o-"-t'-"nJitreott'- ttt'oof system to a racially nondis-

er five had t'otn u'"'tlw as three "ti*inutotv llt'l?3:-'3f"ffi:l ::XHi

Negroes in a student [oii'of 281-to^as fer plan or provlslon

many as 160 in " t'ua"""n?Uoay of 682t ttgt"g'tion is the inevitable conse-

the board mrtst be "quitta

t"o formu- qu"nt-" may stand under the Four-

late a nerv pl"n. ond''uil'iiJr'i""i "ir'"t t't*;i imlnamtnt; if it cannot be

causes rvhich 'ortu'

";;;''

T'lt -i;;:; ii'"f ='"t' a plan rvill further

fashion steps which';;";i'.;";"ai1sti; rrirt.t than delay conversion to a unr-

callv to convert promptl;; to. a system t"t''

' nont"i'i' nondiscriminatory

without a "w'hite"

'stlhool and '

*l'tit'ot system' it is unacceptable'

:i;;' scrroot, but iust schools' civit Rights S 1.2.5 . relief - racial

Civil Rishts s 12.5 _ racial discrim.

-.'.ai""?i'oi'."ti,'. in schools

ination - "free'tri;ti;;" plan to 4'

-fi;;lt"lttv of the principle that

desegregate schools ra;i"i;tt;i;in"ation in public educa-

3. while "f""-t-'In-tft'" plans' ti";'it-;;;;t"iit'tiot''t cannot be al-

which permit " .t,iij"io"^r'*"tv i;;.- i""ri-i"r"'r"rJ. simply because of dis-

fer from his assignla-sctooi to an- ;;;;;;"i rvith such principle'

;;i,.;;;i;;i migi't be varid under

.\PPEAR.\NCES OF COUNSEL

James M' Nabrit III argued the cause for petitioners'

Russell Riee argued the cause for respondents'

Louis f' Cf"iUo"'"e argued the cause for the United States' as

amicus ."i"t,-Lv special leave of Court'

Briefs of Counsel' P 1600' infra'

OPINION OF THE COURT

*691 us 1521 The respondent. Board of Com-

*Mr. Justice #;il" delivered *i..i"r"r.-ry tt-r. School Board for

tt.'opinio' Li tr'' court'

*""rr:lY.i:r',1'r$::' ff:t:l.itt1"t-

This case was arsued with Green i;;;;";;iltid9s -wrt-tr

the citv limits'

" i;;tv s;r'oor go-"id of Newx-ent iot" o""third-of the citv's popu-

countv, 391 us 4;fi0 i na za z-ro' i""ii; ot ao'ooo -are

Negroes' the

88 S Ct rOSg, aniil,r*v u Souta "f il;; -r:"rity of whom live in the

Education of ths a;;id Scho-ol Dis- iiti"

"""1"a1

area' The school sv-s-

trict, 3e1 us 143'-;d'i

-fi 2d 727' ;;;"t,',-. ;ight' elementarv schools'

88 S Ct 169?. f-fi" qu.*tion for de- i1.." Junioi high schools' and two

cision is similar i" tt't question de- t"nio'" t'igtt schools' There are

cided in those case-s.--ff.i" however, ;;#0 chillren enrolled in the-sys-

the principat teaiure of a desegrega- ;eiib ;;h;"ls' about 40% of whom'

ii;;;;:which calls in qlttli9,n over 3,200, are Nesroes'

l[.'*oJ X','., li,r"Tffitu13::,fl 'L:Til

rn 1 e E4 renne ssee bv raw requi red

system in compliance with- Erown *tiui"-t"g"g'ti"' in its public

v Board or eau'jr1iii, iig'ui zga, ;;;..---AcJordinslv, j*i"r',"Tt?;

99 L Ed 10$, # s"ili 1rg (B-Io-wl tarv - schools'

-

1

II)-is not "freedom of choice" but

'Iil"oort'

and orte senioi high school

a variant commonly referred to as ;;;'A;;'ied as "white" schools'

,.free transrar.,)o'''

rererreu uu aD

,ra- tt "a"

elementary schools' one

rF':

t'

i

!

at

?

*

L

;

f

A

*

I

736 U. S. SUPREME

junior high school, and one senior

high school were operated as

"Negro" schools. Racial segrega-

tion extended to all aspects of school

Iife including faculties and staffs.

'[.39] US {53]*After Brown v Board of Educa_

tion, 347 US 488, 98 L Ed 879,74

S Ct 686, 38 ALR2d 1180 (Brown

I), declared such state-imposed dual

systems unconstitutional, Tennessee

enacted a pupil placement law, Tenn

Code S 49-L74L et seq. (1966). That

law eontinued previously enrolled

pupils in their assigned schools and

vested local school boards with the

exclusive authority to approve as-

signment and transfer requests.

No white children enrolled in any

"Negro" school under the statutl

and the respondent Board granted

only seven applications of Negro

children to enroll in ..white,, scho6ls,

three in 1961 and four in 1962. In

March 1962 the Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit held ttrii ttre

pupil placement law was inaclequate

"as a plan to convert a biracial sys_

tem into a nonracial one.,, Norih-

cross v Board of Education of City

of Memphis, 302 F2d 818, g21.

In January 1963 petitioners

brought this action in the District

Court for the Western District of

Tennessee. The complaint sought a

declaratory judgment that respond-

ent was operating a compulsory

racially segregated school system,

injunctive relief against the con-

tinued maintenance of that system,

an order directing the admission to

named "white" schools of the plain-

tiff Negro school children, and an

order requiring respondent Board to

formulate a desegregation plan. The

District Court ordered the Board to

enroll the children in the schools in

question and directed the Board to

formulate and file a desegregation

plan. A plan was duly filed and,

COURT REPORTS 20LEd2d

after modifications directed by the

court were incorporated, the plan

was approved in August 1g68 to be

effective immediately in the elemen-

tary schools and to be gradually ex-

tended over a four-year period to

the junior high schools and senior

high schools. ZZL F Supp 96g.

The modified plan provides for the

automatic assignment of pupils liv_

ing within attendance zoneJ drawn

by the Board or school officials alongr[39r US ,151]

geographic or "natural', *boundaries

and_"according to the capacity and

facilities of the [school] buiidings

." within the zones. Id., at

974. However, the plan also has the

"free-transfer" provision which was

ultimately to bring this case to this

Court: Any child, after he has

complied with the requirement that

he register annually in his assigned

school in his attendance zone, may

freely transfer to another school o1

his choice if space is available, zone

residents having priority in cases of

overcrowding. Students must pro-

vide their own transportation; the

school system does not operate

school buses.

By its terms the "free-transfer"

plan was first applied in the elemen-

.tary schools. After one year of op-

eration petitioners, joined by 27

other Negro school children, moved

in September 1964 for further relief

in the District Court, alleging re-

spondent had administered the plan

in a racially discriminatory manner.

At that time, the three Negro ele-

mentary schools remained all Negro;

and 118 Negro pupils were scattered

among four of the five formerly all-

white elementary schools. After

hearing evidence, the District Court

found that in two respects the

Board had indeed administered the

plan in a discriminatorv fashion.

First, it had systematically denied

Negro children-specifically the 27

intervenors-

from their al

schools wher

in the maj

students se

Negro schoo

been allowed

held this to

lation, see (

tion, 373 US

S Ct 1405, t

the terms o:

Supp 353, i

found that

the lines of

ance zones

three eleme

clude Negrr

white schor

rthose are

schools loct

at 361-362.

In the st

Board filed

posed zone

high schoc

the "white'

Merry, th

school. Ar

the three

racial ider

did have o

otherwise

The facull

spective r

gated. Pr

proposed :

guing firs

gerryman

to assign

"Negro"

children t

Tigrett s

that the

adequate

on a nol

through

that the

a "feedet

[20 L

,;

a.

*,

a:'tt

!.i-

&$

*T*

rt.

Er*

5

TIONROE v BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS 737

3ei u' {50, 20 L Ed 2d 733' 88 s ct 1?oo

intervenors_the,igt,t-totransfermethodofassigningstudentswhere-

from their utl-N"grot'j;.;*;;;;;; uv "u"rt

junior high school would

schools where white;;;;;tr

-;.".

draw its siuclents from specified ele-

in the majority, 'fif'"'gt'

white mentary schools' The groupings

students seeking tt'"ttttt from could be made so as to assure

Negro schools t" *hi;'r;h*t, n"a ru.iuilv integrated.student bodies in

been allowea to transler. The court *ri-ir,r." ju"nior high schools, with

held this to be a ."..iiirti"""i "i"-

au"-r"gu"a for etlucational and ad-

lation, see Goss , B;;;d of Educa- minirtirtiue considerations such as

tion, BTB US 683, 1;L il ii 6Bi, Sg nriiairg capacity.and proximitv of

S Ct 1405, as well ;;;i"'mn ol students to the schools'

ir,"i.t t'of the plan itself' 244F rt,r,L^ r\iorrinr (

Supp 353, 359. St""'* tf'e court tll The District Court held that '/

found that the Board, in drawing petitioners had not sustained their

the lines of the geographic attend- ailegations that the proposed junior

ance zones' h"d'"?;;;*una"t"a high school attendance zones were

three elementary sch6ol ztnes to ex- gerrymandered' saying

;ffi; N;;" residential areas from "Tiqrett lwhite] is located in

-the

white school zones and to include *;;i;; .;;ii;;,'llerrv lNegro] is

fthose ,r.;:t'lru?Jf:l of Negro tocatea in the central section and

schools located farbher away' Id'' i*ffi [white] is located in the

at 861-862.

rf,ner a\'v'lr' ru''

::::Tt"?i'JT};."Jlt. i,111i, XJI-

In the same 1g64 proceeding the ltu,v,-l,ocate the western section

Board filed with the court its pro- to- tigr"tt' the central section to

posed zones for

';i',""";h;;" junior ilit"v] "'u.fl'f, ilt'r?1l "uttt:l.to

[i;h ..h";ls, Jackson and Tigrett' *Jackson. irr" L"rraaries follow

ih;':{hit"" junior high schoolt'.1n9 ;;;;i;".tt ot tigr,*avs and rail-

irritv,---it. "Negro"- junjor, hiql ;;;[. According- to ihe school

school. As of the 1964 school year p"irfrti". maps, there are a con-

th;-l;";;- schools retained their lia'"our" number oi N"g.o pupils in

racial identities, although Jackson iii"- .ouif,"r-n part of the Tigrett

aia tra"e one Nesro child among its ;;;.;-;-- ;onsiherable number of

"if,."*i.. all-white student bodv' ;hl; pupils in the middle and

The faculties and staffs of the re- ;;;th.;-;""t. ot the Merrv zone'

spective schools were also segre-

""J"

.rnr'iderable number of Negro

gated. Petitioners objected to the

"rri[-ir-

fhe southern part o{ !lt"

proposed zones on two gtounds' ar- i;;k;;--r";". The location of the

suing first that they were- racially iili"""-."f,o"t. in an approximate

s*ri*rrraered because so drawn as east-west line makes it inevitable

to assigxr Negro children to the it ri it " three zones divide the city

"Negro" Merry

-str'oot

and white il th;;; parts from north to south'

children to the "*iii";'r"kson 'nd while it appears that pro-ximity of

Tigrett schools,

"

u'J ttt"*atively pupirt and

-natural

boundaries are

that the pt'n *"t*ii anv-event in- ;;; ;t important in zoning for

adequate to reorganize the system .iuniot-ttigf" as in zoning for ele-

on a nonr"iur

'f,"it'

Petitioners' mentary ichools"it does not appear

through

"*p""t"?ir""-."t,

u"gto ;h"t" N;;" pupils will be discrim'

that the Board be required to adopt ;;;;; u'g'intt'1' 244 F Supp' at

a "feeder system," a commonly used 362'

[ 20 L Ed 2Al-47

U. S. SUPRE}IE COURT REPORTS738 U. S. SUPRE}IT]

As for the recommended "feeder

system," the District Court con-

cluded simply that "there is no con-

stitutional requirement that this

particular system be adopted."

Ibid. The Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit affirmed except on an

issue of faculty desegregation, as to

which the case was remanded for

further proceedings. 380 F2d 955.

We granted certiorari, 389 US 1033,

19 L Ed 2d 821,88 S Ct 771 and

set the case for oral argument im-

mediately follorving Green v County

School Board, supra. Although the

case presented brr the petition for

certiorari concerns only the junior

high schools, the plan in its applica-

tion to elementary and senior high

schools is also necessarily impli-

cated since the right of "free trans-

fer" extends to pupils at all levels.

t2l The principles governing de-

termination of the adequacy of the

plan as compliance with the Board's

responsibility to effectuate a transi-

tion to a racially nondiscriminatory

system are those announced today

in Green v County School Board, su-

.t39r us tsTl

pra. Tested by those *principles the

plan is clearly inadequate. Three

school years have followed the Dis-

trict Court's approval of the attend-

ance zones for the junior high

schools. Yet Merry Junior High

School was still completely a

"Negro" school in the 1967-1968

school year, enrolling some 640

Negro pupils, or over 80% of the

system's Negro junior high school

students. Not one of the "consid-

erable number of white pupils in

the middle and northern Parts of

the Merry zone" assigned there un-

der the attendance zone aspect of

the plan chose to stay at MerrY.

Every one exercised his option to

transfer out of the "Negro" school.

The "white" Tigrett school seem-

OURT REPORTS 20 L Ed 2d

ingly had the same experience in

reverse. Of the "considerable num-

ber of Negro pupils in the southern

part of the Tigrett zone" rqentioned

Ly the Districi Court, only ieven are

enrolled in the student body of 819 ;

apparently all other Negro children

assigned to Tigrett chose to go else-

where. Only the "white" Jackson

school presents a different picture;

there, 349 rvhite children and 135

Negro children compose the student

body. How many of the Negro chil-

dren transferred in from the

"rvhite" Tigrett school does not ap-

pear. The experience in the junior

high schools mirrors that of the ele-

mentary schools. Thus the three

elementary schools that were op-

erated as Negro schools in 1954 and

continued as such until 1963 are still

attended only by Negroes. The five

"white" schools all have some Negro

children enrolled, from as few as

three (in a student body of 781) to

as many as 160 (in a student bodY

of 682).

This experience with "free trang-

fer" was accurately predicted by the

District Court as early as 1963:

"In terms of numbers the

ratio of Negro to white pupils is ap-

proximately 40-60. This figure is'

horvever, somev'hat misleading as a

measure of the extent to which in'

't391 us .1581

tegration will actually occur *under

the proposed plan. Because the

homes of Negro children are con-

centrated in certain areas of the

city, a plan of unitary zoning, even

if prepared without consideration oI

race, will result in a concentration

of Negro children in the zones of

heretofore'Negro' schools and white

children in the zones of heretofore

'white' schools. Moreoaer, this

tentlettcy of concentration in schools

u',ill b; f urther accentttated Ay

th,e errr"ise of choice of schools

t20 L Ed 2dl

I

I

i

t

t

t

E

ilI

. ." 221F

phasis suPPlied.

PlainlY, the I

resPondent's "a

take whatever s'

sary to convert

in which racial t

be eliminated

Green v Count;

pra, at 437-438,

Only by dism

imposed dual s

be achieved. I

end has not bee

does the plan a1

courts for the

promise meani

ward doing so.

ther the dismr

system, the ["

has operated si

dren and their

sponsibility wh

squarely on 1

Green v Count

pra, at 441442

That the Boarc

a mtthod achie

tion of the ol

from its long

effort whatsor

and the delibe

manner in whi

istered the plar

District Court

t3, at The

proved the

attendance-zon

that as drawr

dents to the t

that was capal

ing'ful desegr

schools. But.[:

option has *p

erable numbe

students in

zones to retu.

vitation of tt

fortable secur

lished discrim

Sr

MONROE v BOARD

391 us 450, 20 L Ed

. ." 221F SuPP, at 971. (Em-

phasis supplied.)

Plainly, the Plan does not meet

respondent's "affirmative dutY to

takl whatever steps might be neces-

sary to convert to a unitary sYstem

in which racial discrimination would

be eliminated root and branch.''

Green v CountY School Board, su-

pra, at 437438,20 L Ed 2d at 723'

bnly by dismantling the state-

imposed- dual sYstem'can that end

be achieved. And manifestlY, that

end has not been achieved here nor

does the plan aPProved bY the lower

courts for ttre junior high schools

promise meaningful Progress -to-

ward doing so. "Rather than fur-

ther the dismantling of the dual

system, the f"free transfer"] PIan

has operated simply to burden chil- '

dren and their Parents with a re-

sponsibility which Brown II placed

squarely on the School Board."

Green v County School Board, su-

pra, at 441442,20 L Ed 2d at 726.

That the Board has chosen to adoPt

a m6thod achieving minimal disrup-

tion of the old pattern is evident

from its long delay in making anY

effort whatsoever to desegregate,

and the deliberately discriminatory

manner in which the Board admin-

istered the plan until checked by the

District Court.

t3, rl The District Court aP-

Proved the junior high school

attendance-zone lines in the view

that as drawn they assigned stu-

dents to the three schools in a waY

that was capable of producing mean-

insful desegregation of all three

schools. gut the "free-transfer"

'[391 Lis l59l

option has *permitted the "consid-

erable number" of white or Negro

students in at least two of the

zones to return, at the implicit in-

vitation of the Board, to the com-

fortable securitv of the old, estab.

lished discriminatory pattern. Like

OF COMMISSIONERS

2d ?33, 88 S Cb 1?00

739

the transfer provisions held invalid

in Goss v Board of Education, 373

us 683, 686, 10 L Ed 2d 632, 635'

83 S Ct 1405, "[i]t is readilY aP-

parent that the transfer [provision]

iends itself to perpetuation of segre-

g:ation." While we there indicated

thrt "free-transfer" Plans under

some circumstances might be valid,

we explicitly stated that "no official

transfLr plan or provision of which

racial segregation is the inevitable

consequence may stand under the

Fourteenth Amendment'" Id., at

689, 10 L Ed 2d at 636. So it is

here; no attemPt has been made

to justify the transfer provision as

a device designed to meet "legiti-

mate local Problems," ibid.; rather

it patently oPerates as a device to

allow resegregation of the races to

the extent desegregation would be

achieved by geographicallY drawn

zones. ResPondent's argument in

this Court reveals its PurPose. We

are frankly told in the Brief that

without the transfer oPtion it is

apprehended that white students

wiit flee the school sYstem alto-

gether. "But it should go without

saying that the vitality of these con-

stitutional prineiples cannot be al-

il;;; t; vlera Jimplv because of i

disagreement with them." Brown

i

tt, ai goo, 99 L Ed at 1106. -)

We do not hold that "free trans-

fer" can have no place in a desegre-

gation plan. But like "freedom of

choice," if it cannot be shown that

such a plan will further rather than

delay conversion to a unitary' non-

racial, nondiscriminatorY school

system, it must be held unaccePt-

able. See Green v CountY School

Board, supra, at 439-441, 20 L Ed

2d at 724-726.

t2I We conclude, therefore, that

the Board "must be required to

formulate a new Plan and, in light

of other courses which appear open

740

to the Board, fashion steps

which promise realistically to con-rt39l us 4601

vert promptly to a rsystem without

a'white' school and a'Negro' school,

but just schools." Id., at 442,20 L

Ed 2d at 726.t

The judgment of the Court of Ap-

peals is vacated insofar as it af-

U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 20LEd2d

firmed the District Court's approval

of the plan in its application to the

junior high schools, and the case is

remanded for further proceedings

consistent with this opinion and

with our opinion in Green v County

School Board, supra.

It is so ordered.

f We imply no agreement with the Dis-

trict Court's conclusion that under the pro-

posed attendance zones for junior high

sehools "it does not appear that Negro

pupils will be discriminated against.'l We

note also that on the record as it now

stands, it appears that petitioners' recom-

mended "feeder system," the feasibility of

which respondent did not challenge in the

District Court, is an effective alternative

reasonably available to respondent to abol-

ish the dual system in the junior high

schools. 39

Defendant war

magazines to a n

repealed, which

the lust of mino

ferences betweer

Term of the Ner

On appeal, th

per curiam opin

it was held that

DoucLAs, J.,

even obscene m

freedom of spee

HARLAN, J.,

(1) the majorit

ute than the cou

in this area of

act to strike do

already been re

75

t407 us r84l

UNITED STATES, Petitioner,

v

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION

(No. 70-130)

et al.

PATTIE BLACK COTTON et al., Petitioners,

v

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION et al.

(No. 70-187)

407 US 484,33 L Ed 2d 75,92 S Ct 2214

[Nos. 70-130 and 70-187]

Argued February 29 and March l, 1972. Decided June 22, t972.

SUMMARY

After the United States Department of Justice had obtained an agree-

ment whereby a county school board undertook to desegregate a dual,

racially segregated county school district consisting of. 22 percent white

students and77 percent Negro students, and after the state department of

public instruction, acting on a request from the county school board, had

recommended a detailed desegregation plan, the North Carolina state

legislature enacted a statute authorizing a city within the county to create

a separate school district. About 57 percent of the students in the city's

public schools were white, and about 43 percent were Negro, and if

the city had its own school district, a formerly all-white school in the city

would retain a white majority, while a formerly all-Negro school just

outside the city would be 91 percent Negro. In the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, the United States sought

injunctive relief against the establishment of a separate school district

for the city. The District Court granted an injunction, holding that the

state statute was enacted with the effect of creating a refuge for white

students, and that the statute interfered with the desegregation of the

county school system (314 F Supp 65). The United States Court of Ap-

peals for the Fourth Circuit reversed, holding that the effect of the separa-

tion of the city's schools and students on the desegregation of the remainder

of the county was minimal and insufficient to invalidate the state statute

(442 Fzd 576).

Briefs of Counsel, p779, infra.

78 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 33LEd2d

Burger, C. J., filed an opinion concur- py9llt11d Rehnquist, JJ., joined post,ring in the result, in whlch Si".L*rn, p +of, eS L Ed 2d p g1.

APPEARANCES OF COUNSEL

Lawrence G. rvarace argued the cause for petitioner in No.70-130.

Adam stein argued the cause for petitioners in No. T0-1g2.William T. Joyner and C. Kitchin Joeey

".g*a-if," cause forrespondents in both cases.

Briefs of Counsel, p 77g, infra.

UNITED

city limits o

approval by :

voters.r Th,

March 3, 19

the 1969 Se

Carolina. Tl

Neck approvr

t

trict in a reft

and the new

steps towarc

school systet

The effect

carve out of

trict a new r

of whom 399

2s6 (43%\

transfer plat

appointed Sc

of Educatio

white and 1

side the city

fer into the

while 44 stt

plied to tran

tem to a ne:

fax County

district plan

of the forrr

Neck High

building loc

limits that

the eounty.

The Unitt

suit in June

and county t

gation of th

1. An earlie

the 1966 sessi

would have cr

trict for Scotl

rounding towr

to-one Negro

plated that th

under a freed

that existing

The bill wac r

2. The vote

to 332 in favr

Ol Scotland

voteru, 360 trr

3. After th,

OPINION OF

t{07 us 4851

Mr. Justice Stewart delivered the

opinion of the Court.

The petitioners in these con-

solidated caseg challenge the imple-

mentation of a North Carolina siat_ute authorizing the creation of a

n-ew- school district for Scoiland

Neck, a city which at the time oi

the statute's enactment was part of

a larger school distriet then'in the

process of dismanfling a dual school

system. In a judgment entered the

same day as its judgment in Councilor Urty of Emporia v Wright,

442 Fzd 570, a decision which-we

Jev:rjse^ today, 402 US p 4b1, BB

: rrg z-d .p Et, 92 S Ct 2196, the

Cgurt of Appeals held that the Dis_

trict..Court erred in .n:oinirrg tf,1

creation of the new school disirict.

Scotland Neck is a community of

about 3,000 persons, located in the

southeastern portion of Halifax

County, North Carolina. Since 1g86,

the city has been a part of the Hali-

fax County Adminiitrative Unit, a

school district eomprising the entire

county with the exception of two

towns located in the northern sec_tion. In the 1968-1969 school year,

10,655 students attended schois inthis system, of whom 77Tc *.""

Negro, 22% white, and lTo Amer_

ican Indian.

The schools of Halifax County

wer-9 completely segregated by race

until 1965. In that year, the school

board adopted a freedom_of-choice

THE COURT

plan that produced very

t,107 us 4861

desegregation. In rn" "lSt ii'rH

school year, all of the white students

in the county attended the four tra-

{itlgnatly all-white schoots, whiie

97% of. the Negro students aitendedth-e L4 traditionally all-Neero

schools. The school-busing .v.iJ*,

used by 90% of. the studenti, was

segregated- by race, and faculty

desegregation was minimal.

_ In 1968, the United States

Department of Justice

"nte""a

irrionegotiations with the HalifaxCounty School Board to b;i;;the county's school system l"i;

compliance with federai law. An

agreement was reached wherebythe school board undertook 6provide some desegregation in thefall of 1968, and to effect a com_

pletely unitary system in the 1969_

1970 school year. The State Depart_

ment of Public Instruction, ,ctirg

on a request from the county board,

recommended a detailed plan (the

Interim -Plan) for thg uniiary

system that would have put somlwhite students in every school in

the county, and that *orta have lefi

a white majority in only one school.

In January 19Gg, after the Interim

Plan had been submitted to the

county school board but before any

action had been taken upon it, a biil

was introduced in the state legisla_

ture to authorize the creation of a

new school district bounded by the

UNITEDSTATESvSCoTLANDNECKCITYBD'oFED.79

{0? us {8{, 33 L Ed 2d 75, 92 S ct 2214

citylimitsofScotlandNeck,upontyschools.sThecomplaintasked

,pir"t"i uv ; -r:oritv "]

th; ciiv's for preliminarv and. permanent in-

;;;;i tn" Uitj was enacted on junctions against the implementa-

March 3, 1909, u...Ctupt.. 31 o-f iion of Chapter 31. Various Negro

the 1g6g Session f,o*.'of Xortfr children, parents, and teachers, the

C'".rfi.". The citizens of Scotland petitioners in No' 70-187 ' were per-

x".t ,ppr"ved the new school mitted to intervene as plaintiffs'

t407 us 4871

dis- After a three-day hearing before

trict in a referendum a month tater,t two district judges on both this case

andthenewdistrictbegantakingandasimilarcaseinvolvingtwo

steps toward beginning

"a separate newly created school districts in

..i,Lr

-;t.d i. *,.'i',ri "i-ie-6e.- ts::tH:t:f,"rY,1",i,i11,,?i,i""Y;",lli

The effect of Chapter 31- was.to the implementation of Chapter 31,

carve out of the Halifax schoo-l dis- finding that "the Act in its appli-

trict a new unit with 695 students' cation creates a refuge for white

of whom ggg (57%') were whlte and students, and promotes segregated

iia t+g%) were Negry' .-under,a schools in Halifax couniy,"- and

transfer plan deviseg !v j|t" ::Y-i{ further that,,[t]he Act impedes and

appointed Scotland-Neck L.ity lJoard

Cefeats the Halifax County Board of

oI'Pau.rtio", 360 students (350 :

*r,it" and 10' N.g.oi-i*iqi"g ",1- f,}ltjl .JilT,r'#::H#,1:t",1;

fer into the Scotland Neck schools, the public schools in Halifax County

while 44 students

"O'!

IT;gro) ap' by the opening of the school vear

plied to transfer out of the city sy,s- 1969-70'"{ After further hearings'

tem to a nearby ..t *t i" tf,e ffiti- t407 us 4881

fax County system. The new the District Court on May 23' 1970'

district planned to use the facilities found Chapter 31 unconstitutional

of the formerly att-wfrite Scotland and permanently enjoined its en-

Neck High School, including one forcement' 314 F Supp 65' The

building located outside the city court of Appeals reversed, 442 F2d'

limits that would be leased from 575' and we granted certiorari' 404

the county Us 821, 30 L Ed 2d' 49,92 S Ct 4?.

The United States filed this law-

suit in June 1969 against both citY

and eounty officials, seeking desegre-

gation of the existing Halifax Coun-

tl-31 The Court of APPeals did

not believe that the seParation of

Scotland Neck from the Halifax

County system should be viewed as

1. An earlier bill had been introduced in

the 1966 session of the legislature, which

would have created a separate school dis-

trict for Scotland Neck and the four sur-

rounding townships, an area with a three-

to-one Neglo majority' It was contem-

plated that the new district would operate

under a freedom-of-choice plan similar to

that existing in the county at the time'

The bill wasr defeated in the State Senate'

2. The vote in the referendum was 813

to 332 in favor of the new school district'

Ol Scotland Neck's 1,382 registered

voten, 360 were Ne8ro.

3. After the preliminary injunction was

issued in this case, the District Court dis-

missed the Ilalifax County Board of Edu-

cation from that part of the case dealing

with Scotland Neck's efrorts to implement

a separate school sYstem' On MaY 19,

iSzo, tlr. court ordered the county-school

board to implement, beginning in the fall

of 19?0, the-Interim Plan proposed by the

State Department ol Public Instruction,

with certain modifications proposed by the

school board.

4. The opinion ol the District Court on

the issuance of the preliminary injunction

is unreported.

80 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 33LEd2d

an alternative plan for desegregating

!h" county system, because th;

"severance was not part of a aeseg_

lesation plan proposed by the scho6l

board but was instead an action bv

the Legislature redefining the founa"_

aries of local governmental units.,,

442Fzd, at E8B. This suggests that

an action of a state Iegislalure affect_

ing tt "

de,qegls*.1ion of a dual sys_tem stands on a footing ditrerent

from an action of a sch'ool b;a;d.

But in North Carolina Board of ear_

91tr,on v Swann, 402 US 48, Zg t Ed

2_d 586, 91 S Ct 12g4, decided aftei

the-decision of the Court

"t epp""i.

in this case, we held that ,,if ;;;;;;:

imposed Iimitation on a school au_

-t|-o-Iity'r discretion operates to in_hibit or obstruct the dis_

establishing of a dual school system,it mus-t falt; state policy ;di;t;;

way when it operatei to hinder ui-nJi_

cation of federal constitutionrt gur"_

311"".:_ Id., at 45, Zg L ea IJ at589. _The fact that ttr" .r"rtio, Jithe Scofland Neck school- ai-iir.iwas authorized by a special act oitne state legislature

t407 US 489I

the schoot board ," .i#1"Jr*?L,:l

thus has no constitrti";; ;lc"ifi:

cance.

[4, t] 1rys have today held that

any attempt by state or local officialsto carve out a new school clistrici

from an existing district that-is i;the process of dismantling a dual

school system .,must be jutgea-ac-

c-ording to whether it hind-erslr fur_

thers the Drocess of school d.*;;_sation. If the proposal would

imoede the dismaniting of , J;;i

system, then a district court, in the

exercise of its rbmedial discretion,

may enjoin it from being carriedort." Wright v Council o1 City oi

Emporia, supra, at 460, gS L Ud ZJ

at 60. The District Court in this case

concluded that Chapter Bl ,,was en-

acted with the effect of creating a

refuge for white students of the

Halifax County School system, anJ

interferes with the desegiegation oithe Halifax County School sys_tem . .,, 814 F Supp, atiA.

The Court of Appeals, however, did

not regard the separation of Scot-

land Neck as creating

" ".trg. fo"

white students seeking to escfre aL-

segregation, and it held that ,,the

9ffect of the separation of the Scoi-

land Neck schools ana students onthe desegregation of the ,"rnrina"iat the Halifax County ,y.t.rn-is

minimal and insufficient to invatiaaie

Chapter 81.,, 442 FZd at OAZ. Oui

review of the record leads us to con-

clude that the District Couri. ieilr_

mination was the only proper i;i;;-

ence to be drawn from the facts ofthis case, and we ttru,

".u"r."

ii"judgment of the Court "i A;;.;i;:

T!9 major impact of Chapter Bl

would fall on the southeastern por-

tion of Halifax County, designated

as District I in the Interim pLn for

Slitary schools proposed by the

State Department of public Instruc_tion. The projected enrollment in

the schools of this district under the

Interim PIan was 2,94g students, oi

whom 78/o werc Negro. If Chan_

ter 31 were implemented, the Scoi_

land Neck schools would be 57/o

t407 us 4901

white, while the schools remainingin District I would be gg/" N.;;;:

The traditional racial identities- ofthe schools in the area would be

maintained; the formerly all_white

Scotland Neck school would ,.trin

"l:lrit" majority,_while the for*.ify

atl-Negro Brawley school, a higir

scnoot tocated just outside Scofland

Neck, would be gl % Negro.

[6, 7I In Swann v Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 US L,2g L Ed 2d 654, 91 S C[

1267, we said that district judges or

UNITED

school autho

every effort t

possible degrt

tion," and tha

to remedy sta

regation therr

tion against

stantially dis

racial compos

LEd2datS

today in Writ

Emporia, sup

at 62, that

achieved by s

system opera

'Negro schoo

tems, each op

within its bor

two new syst

and the othe

tsl In this

ity in the ra,

Scotland Nt

schools remai

Halifax Cou

"substantial''

measuremenl

response am(

side Scotlan

board's proP,

firmed what

the Scotlanc

be the "whi'

while the ot

would remi

Mr. Chief

whom Mr.

Justice Pov

Rehnquist j

result.

I agree thr

rate school s

would tend t

5- The figurr

Appeals were r

mitted to this C

[33 L Ed 2dl-{

UNITED STATES V SCOTLAND NECK CITY BD. OF ED' 81

107 us 484, 33 L Ed 2d 75' 92 S ct 2214

schoolauthorities..shouldmakeGiventhesefacts'wecannotbut

everyefforttoachievethegreatestconctudethattheimplementationof

oossible degree "t u"iu'i'LJ"gt"g'- Chapter :31 ryoul{ have the effect

il#l;#'r.'hJi.^t"rt"rrrting a plan oi impeains the disestablishment of

toremedystate-enforcedschoolseg-tt,.au^tschoolsystemthatexisted

rlJi'ii"t ih"* strould be "a presump- in Halifax Countv'

Hl,;1il":1d:l;:lit"t#,t" 1l',;11; , t8r rhe primarv argument made

racial composition."""if, ]'u'" 2;,';i bv the ttto?i$"t'*t

rtJl,

L pa za ai slz. And we have said support of

today in Wright v Council-otC:ty:{ Chapter 31 is that the separation of

Emporia. supra, at 463, 33 L Ed 2d itu "i.otfuna Neck schools from

at 62, that "desegregation ls .nor those of Halifax County was neces-

achievecl by splitting a sinsle school ;;;;1;;rrid "white flight" bv Scot-

system operoting.'white schools' and i".i

-N".f.

residents into private

,Ttr:ffi';;5r","X?J#,X,l,"[1fi Xm:,ffi'#ltli:]i:J:il'$::

;tf **:}.",:ff ''Iir;;T';"1[: ;;;' -' sffirementar affi davits were

and the other is, in fact, ,Negro., ,' rrrrniti.d'to th. court of Appeals

ao.o..nting the degree to which

t5l In this litigation' the dispar- ir't tvttt*las undergone a loss of

itv in the racial tornpoliiio" 9f ll't ti'auntt since the unitary school

ilJ";iil;' NJJI t"iii"rt and the oiun toor' effect -in

the fall of 1e70'6

;;;;;i;;.*aining in District I of the sitt *t'itt this development mav be

Halifax county system would be cause for deep concern to the re-

'

,,substantial" by

"iry

.trnaard of spontients, i!--e?I,qqt, as the Cgurj of fl

;;;t;t;t"nt' And tire enthusiastic Appeals reciignized' be accepted- as

response among whites residing out- u tuuto" for achieving anything less

.iJ|-i."tf"nd

-Nect< to the school tf,r, ."-;fete uprooting oi the dual

[""ra;. froposed transfer plan con- public school system. See Monroe

nit "J

*r,it the figures suggest: I-.goota <if-fffimissioners' 391 us

ite- stotrund Neck school was to 450' 459'20 L Ed 2d ?33' 739' 88 s ct

be the "white school" of the area' 1700'

while the other District I schools

would remain "Negro schools'" Reversed'

SEPARATE OPINION

Mr. Chief Justice Burger, with

whom Mr. Justice Blackmun, Mr'

Justice Powell, and Mr' Justice

Rehnquist join, concurring in the

result.

I agree that the creation of a sePa-

rate school system in Scotland Neck

would tend to undermine desegrega-

tion efforts in Halifax CountY, and

i tf,r. join in the result reached bY

tf," Coutt. However, since I dis-

."nt"a from the Court's decision in

W"igftt v Council of CitY J! E-t-

porii, 407 us, p 471,33 L Ed 2d P

'OO, t'feel constrained to set forth

Uri"nv the reasons why I distinguish

the cases.

5. The figures supplied to the Court of

lpp."i. *"-"e updated by an affidavit. sub-

miltea to this Court, showing the total en-

[33 L Ed 2dl{

rollment in the Halifax County schoolg at

H;';A"t ot ttt" lg?r-1972 school vear-to

ii""" U*" S,Ogl, of whom 1474 were white'

82 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 33LEd2d

First, the operation of a separate

school system in Scotland Neck

would preclude meaningful desegre-

gation in the southeastern portion of

Halifax County. If Scotland Neck

were permitted to operate separate

schools, more than 2,200 of the

nearly 3,000 students in this sector

would attend virtually all-Negro

schools located just

t1o7 us n"o'ur.ro"

of the

corporate limits of Scotland Neck.

The schools located within Scotland

Neck would be predominantly white.

Further shifts could reasonably be

anticipated. In a very real sense,

the children residing in this rel-

atively small area would continue to

attend "Negro schools" and "white

schools." The effect of the with-

drawal would thus be dramatically

different from the effect which could

be anticipated in Emporia.

Second, Scotland Neck's action

cannot be seen as the fulfillment of

its destiny as an independent govern-

mental entity. Scotland Neck had

been a frart of the county-wide school

system for many years; special leg-

islation had to be pushed through

the North Carolina General As-

sembly to enable Scotland Neck to

operate its own school system. The

movement toward the creation of

a separate school system in Scotland

Neck was prompted solely by the

likelihood of desegregation in the

county, not by any change in the

political status of the municipality.

Scotland Neck was and is a part of

Halifax County. The city of Em-

poria, by contrast, is totally inde-

pendent from Greensville County;

Emporia's only ties to the county

are contractual. When Emporia be-

came a city, a status derived pursu-

ant to longstanding statutory pro-

cedures, it took on the legal responsi-

bility of providing for the education

of its children and was no longer en-

titled to avail itself of the county

school facilities.

Third, the District Court found,

and it is undisputed, that the Scot-

land Neck severance was substan-

tially motivated by the desire to

create a predominantly white system

more acceptable to the white parents

of Scotland Neck. In other words,

the new system was designed to

minimize the number of Negro chil-

dren attending school with the white

children residing in Scotland Neck.

No similar finding was made by the

District Court in Emporia, and the

record shows that Emporia's deci-

sion was not based on the projected

racial composition of the proposed

new system.

A

A state pr

Court of Ap

in the Unitr

alleging for

from the gr

had convicte

States Cour'

because the

unconstituti

F2d 370).

On certio:

Although nt

that the prir

systematic ,

oner's allegr

conviction t

Mlnsnnr

joined by I

his race, a

system on'

from grand

of law, it r

bias.

WHtts, J

ment, stati

provides tt

or state gr

central con

t33 L Ed 2dl Briefs o