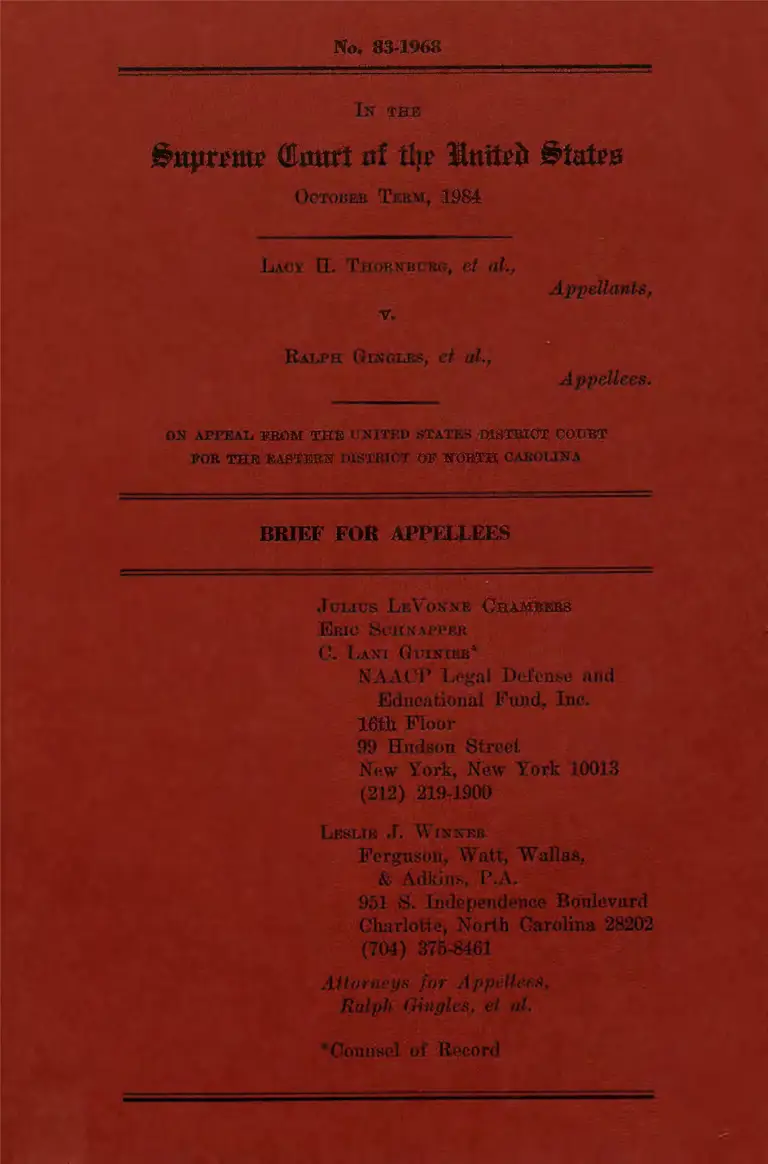

Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

August 30, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Brief for Appellees, 1985. 316ff476-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eaf2605d-330a-42a4-9687-b459f97c221c/brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

•

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

( 1 ) Does section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act require proof that

m ~ nority voters are totally

excluded from the political

process?

(2) Does the election of a minority

candidate conclusively establish

the existence of equal electoral

opportunity?

(3) Did the district court hold that

section 2 requires either

proportional representation or

guaranteed minority electoral

success?

- i -

(4) Did the district court cor

rectly evaluate the evidence of

racially polarized voting?

(5) Was the district court's finding

of unequal electoral opportunity

"clearly erroneous"?

- ii -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented •••••••••••••• i

Table of Authorities ••••••••••••• vi

State ment of the Case •.•.•••••••• 1

Findings of the District Court ••. 7

Summary of Argument ••••••••••••.• 15

Argument

I. Section 2 Provides

Minority Voters an Equal

Opportunity to Elect

Representatives of their

Choice . • • . • . • • • • • • • • • • . 19

A. The Legislative History of

the 1982 Amendment of

Section 2 •••••••••••••• 21

B. Equal Electoral Oppor

tunity is the Statutory

Standard ••••••••••••..• 44

C. The Election of Some

Minority Candidates Does

Not Conclusively Establish

the Existence of Equal

Electoral Oppor-

tunity •••••••••.••••• 50

- iii -

II. The District Court Re

quired Neither Proportional

Representation Nor Guaran

teed Minority Political

I II.

Success • • . • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 64

The District Court Applied

the Correct Standards In

Evaluating the Evidence of

Polarized Voting •••••••••. 70

A. Summary of the District

Cour~'s Findings...... 73

B. The Extent of Racial

Polarization was Sig

nificant, Even Where

Some Blacks Won....... 76

C. Appellees were not Re

quired to Prove that White

Voters' Failure to Vote

for Black Candidates was

Racially Motivated •••• 81

D. The District Court's

Finding of the Extent of

Racially Polarized

Voting is not Clearly

Erroneous •••••••••••.• 88

IV. The District Court Finding

of Unequal Electoral . Oppor

tunity Was Not Clearly

Erroneous ................. 95

A. The Applicability of

Rule 52 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 95

- iv -

Conclusion

B. Evidence of Prior

Voting Discrimi-:-

nation ••••••••••••••• 102

C. Evidence of Economic

and Educational Dis

advantages • • • • • • • • • • • 107

D. Evidence of Racial

Appeals by White

Candidates • • • . • • • • • • • 113

E. Evidence of Polar-

ized Voting • • • • • • • • . • 118

F. The Majority Vote

Requirement •••••••••• 118

G. Evidence Regarding

Electoral Success of

Minority Candi-

dates • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . 121

H. The Responsiveness

Issue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

I. . Tenuousness of the

State Policy for Multi

member Districts ••••• 131

135

- v -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Alyeska Pipeline Service v. Wilder

ness Society, 421 U.S.

240 (1975) •.••••.••••••••... 100

Anderson v. City of Bessemer

City, U.S. , 84

L.Ed.2cr----518 (1"91f5") ••• •• • 16,98,99

Anderson v. Mills, 664 F.2d

600 (6th Cir. 1981) •••.•••.• 84

Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union,

8 0 L. Ed • 2d 50 2 ( 1 9 8 4) • • • • • • . 9 8

Buchanan v. City of Jackson,

708 F.2d 1066 (6th Cir.

1983) • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • 96

City of Port Arthur v. u.s.,

517 F. Supp. 987, affirmed

459 u.s. 159 (1982-) •••••..• 85,120

City of Rome v. U.S., 446 u.s.

156 (1980) .••••••.••..•.

Collins v. City of Norfolk,

768 F.2d 572 (4th Cir.

72,99,120

July 22, 1985) ••.••••••••.•• 96

- vi -

Cases

Connecticut v. Teal, 457

u.s. 440 (1982) ••••••••• •••• 63

Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875

(5th Cir. 1979) •••••••••••.• 56

David v. Garrison, 553 F.2d 923 .

(5th Cir. 1977) ••••••••••••• 110

Dove v. Moore, 539 F.2d 1152

(8th Cir. 1976) . • ••••••••••• 110

Ernst and Ernst v. Hochfelder,

425 u.s. 185 (1976) ••••••••• 50

Garcia v. United States, u.s.

10s s.ct. 479 (1984) •••• 36

Gaston County v. United States,

395 u.s. 285 (1969) ••••••••• 107

Gilbert v. Sterrett, 508 F.2d

1389 (5th Cir. 1975) •••••••• 96

Harper & Row, Publisher v.

Nation, u.s. , 85 L.Ed.2d

588 (198m-•••••• -:::......... 98

Hendrick v. Walder, 527 F.2d 44

(7th Cir. 1975) • • • • • • • • • • • • • 110

Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d

1265 (5th Cir. 1977) •••••••• 96

Hunter v. Underwood, . U.S. ,

8 5 L. Ed. 2d 2 2 2 ( n8'5) • • • • • . • 9 9

- vii -

Cases

Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727

F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1984);

reh'g en bane denied, 730

F.2d 233 (1984) .• ~ •••••• 88,96,130

Kirksey v. Bd. of Supervisors, 554

F • 2d 1 3 9 ( 5th C i r • 1 9 7 7 ) • . • 56

Kirksey v. City of Jackson, 699

F.2d 317 (5th Cir. 1982) •••• 84

Lodge v. Buxton, Civ. No. 176-

55 (S.D. Ga. 10/26/78), aff'd

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 u.s.

613 (1982) • •• ••••• ••.• •• •• •• 80

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325

(E.D. La. 1983}(three judge

court) ..................... 56,71,78

McCarty v. Henson, 749 F.2d

1134 (5th Cir. 1984), aff'd

753 F.2d. 879 (5th Cir.

(1985) •••••••••••••••••••••• 96

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp.

380 (N.D. Ga. 1984), aff'd 753

F.2d 877 (5th Cir. 198!>) •• .•• 86

McGill v. Gadsden County

Commission, 535 F.2d 277

(5th Cir. 1976) •••••••••.•.• 96

McMillan v. Escambia County, 748

F.2d 1037 (11th Cir. 1984) •• 108,130

Metropolitan Edison Co. v. PANE,

460 u.s. 766 (1983) •••••••.• 98

- viii-

Cases

Mississippi Republican Execu

tive Committee v. Brooks,

u.s. , 105 s.ct.

4'f'b ( 1984}.................. 85

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 u.s. 55

(1980} ••••••••••••• • •••• 22,23,24,30,

NAACP v. Gadsden County School

Board, 691 F.2d 978 (11th

82

Cir. 1982} • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 80

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209

( 1 978) ••••••••••••••••••••••

Parnell v. Rapidas Parish School

Board, 563 F.2d 180 (5th

68,69

Cir. 1977) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • 96

Perkins v. City of West Helena,

6 7 5 F • 2d 2 0 1 ( 8th C i r • 1 9 8 2 ) ,

aff'd mem. 459 u.s. 801

( 1 gs2)-.-...................... ·ss

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 u.s. 613

(1982) •••••••••••• 79,80,85,99,130

South Alameda Spanish Speaking

Org. v. City of Union

City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th

Cir. 1970)................... 84

Str i ckland v. Washington, U.S.

, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (~4) 98

United Jewish Organizations v.

Carey, 403 u.s. 144

( 1977) • • . . . • • . • • • • • • • • • • • . • • 68

- ix -

Cases

U.S. v. Bd. of Supervisors of

Forrest County, 571 F.2d

951 (5th Cir. 1978) ••.•. . ... 56

u.s. v. Carolene Products Co.,

304 u.s. 144 (1938) ••• ~..... 71

u.s. v. Dallas County Commission,

739 F.2d 1529 (11th Cir.

1984} • • • . . . • • . . . . . . . • • • • . • • 97

u.s. v. Executive ~ommittee of

Democratic Party of Greene

County, Ala. 254 F. Supp.

543 (S.D. Ala. 1966) ••••••.•

u.s. v. Marengo County Commission,

731 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir.

84,85

1984) • ••. . .• ••• .••• ••• 56,57,85,96,

108,130

Velasquez v. City of Abilene,

725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir.

1980} • • • • • • • • . • . • • • • • • • • • . . • 56' 96

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619

(5th Cir. 1975) •••••••••••• 56,59

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 u.s.

1 24 ( 1971 ) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 29

White v. Regester, 412 u.s.

755 ( 1973) • • • • • • • • • Eassim

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1973) (en bane),

aff'd sub nom East Carroll

Par1sh-schooi Board v. Marshall,

424 u.s. 636 (1976) 30,55,58,96

- X -

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Statutes

Section 5, Voting Rights Act of

1965, 42 u.s.c.

§1973c ••••••••••••••• 3,4,22,133

Voting Rights Act Amendments of

1982, Section 2,

96 Stat. 131, 42 u.s.c.

s 1973 •• 8 ••••••••••••••••••

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

passim

Rule 52(a} •••••••••••• 67,98,100,101

Constitutional Provisions:

Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments ••••••••••••••••

House and Senate Bills

H.R. 3198, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.,

S2 •••••••••••••••••••••••

H.R. 3112, 97th Cong., 1st

Sess., S201 ••••••••••••••

Senate BillS. 1992 ••.••••••••

Congressional Reports

House Report No. 97-227, 97th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1981}

Senate Report No. 97-417, 97th

Cong., 2d Sess. ( 1982} •••

- xi -

passim

23

23

33,34,36

passim

passim

Congressional Hearings

Hearings before the Subcommittee

on Civil and Constit~tional

Rights of the House Judiciary

Committee, 97th Cong., 1st Sess

( 1 981) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 23

Hearings before the Subcom-

mittee on the Constitution

of the Senate Judiciary

Committeeon S.53, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1982) ••••••••• 28,34,35,41,

42,43

Congressional Record

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. Oct.

2' 1 981 ) .•..........•.•.. 25,26,29

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed., Oct.

5, 1981) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 26,27, 29

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. Oct.

15, 1981) ••••••••••••••• 29

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June 9,

1982) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35,37,40,47

48,54,82

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June 1 0,

1982) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35,37

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June 1 5,

1982) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29,34,37,82

128 Cong. Rec. {daily ed. June 16,

1 982) • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • 56

- xii -

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June 17,

1982) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 31 '34' 3 7' 39

48,53,82

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June

18, 1982) •••••••••• 29,37,46,48,53

72,82

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June

23, 1982) .••••••••••••••••

Miscellaneous

Joint Center for Political Studies

National Roster of Black

Elected Officials

34

( 1984) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1

Los Angeles Times, May 4,

1982 . • • . . . . . • • . • • • • • • • • • 43

Wall Street Journal, May 4,

1982 •••••••••••••••••••••• 43

New York Times, Dec. 18, 1981,

p. B7, col. 4 •••.•••••••• 41

- xiii-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE1

This is an action challenging the

dist~icting plan adopted in 1982 for the

election of the North Carolina legisla-

ture. North Carolina has long had the

smallest percentage of blacks in its state

legislature of any state with a subs tan-

tial black population. 2 Prior to this

litigation no more than 4 of the 120 state

representatives, or 2 of the 50 state

The opinion of the district court as

reprinted in the appendix to the

Jurisdictional Statement has two signifi

cant typographical errors. The Appendix at

J.S. 34a and 36a states, "Since then two

black citizens have run successfully in

the (Mecklenburg Senate district) ••. "

and "In Halifax County, black citizens

have run successfully ••• " Both sentences

of the opinion actually read "have run

unsuccessfully." (Emphasis added). Due to

tnese and other errors, the opinion has

been reprinted in the Joint Appendix, at

JA5-JA58.

2 See Joint Center fo~ Political Studies,

National Roster of Black Elected Officials

(1984) 14, lb-17; JA Ex. Vol. I, Ex. 1.

'

- 2 -

senators, were black. 3 Although blacks are

22.4% of the state population, the number

of blacks in either house of the North

Carolina legislature had never exceeded

4%. The first black was not elected to

the House until 1968, and the first black

state senator was not elected until 1974.

North Carolina makes greater use of at

large legislative elections than most

other states; under the 1982 districting

plan 98 of the 120 representatives and 30

of the 50 state senators were to be chosen

from multi-member districts. 4

In July 1981, following the 1980

census, North Carolina initially adopted a

redistricting plan involving a total of

148 multi-member and 22 single member dis -

3

4

Stip. 96, JA 94-5 .

Stip. Ex. BB and EE, Chapters 1 and 2

Sess. Laws of 2nd Extra Session 1982, JA

67.

- 3 -

. t 5 tr1c s. Under- this plan ever-y single

House and Senate distr-ict had a white

majority. 6 There was a population devia-

tion of 22% among the pr-oposed distr-icts.

Forty of Noeth Carolina's 100

counties are covered by section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act; accordingly, the state

was cequ iced to obtain preclearance of

those por-tions of the redistricting plan

which affected those 40 counties. North

Carolina submitted the 1981 plan to the

Attorney General, who entered objections

to both the House and Senate plans, having

concluded that "the use of large multi-

member districts effectively submerges

cognizable concentrations of black

5

6

Stip. Ex. D and F, Chapters 800 and 821

Sess. Laws 1981, JA 61.

The opinion states one district was

major-ity black in population, JA7,

referr-ing to the second 1981 plan,

enacted in October- after this lawsuit was

filed. Stip. Ex. L, JA 62.

population into

torate." Stip.

- 4 -

a majority white elec

Ex. N and 0, JA6 3. For

similar reasons, the Attorney General also

objected to Article 2 Sections 3(3)and

5(3) of the North Carolina Constitution,

adopted in 196 7 but not submit ted for

preclearance until after this lawsuit was

filed, which forbade the subdivision of

counties in the formation of legislative

districts. Stip. 22, JA 63.

Appellees filed this action in

September 1981, alleging, inter alia, that

the 1981 redistricting plan violated

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the

Fourteenth Amendment. Following the

objections of the Attorney General under

section 5, the state adopted two subse

quent redistricting plans; the complaint

was supplemented to challenge the final

plans, which were adopted in April, 1982.

Stips. 42,43; JA 67. In June 1982 Congress

5 .;..

amended section 2 to forbid election

practices with discriminatory results, and

the complaint was amended to reflect that

change; thereafter the litigation focused

primarily on the application of . the

amended section 2 to the circumstances of

this case. Appellees contended that six

of the multi-member districts had a

discriminatory result which violated

section 2, and that the boundaries of one

single member district also violated that

provision of the Voting Rights Act.

After an eight day trial before

Judges J. Dickson Phillips, Jr., Franklin

T • Dupree , J r • , and W • Ear 1 B r i t t , J r . ,

the court unanimously upheld plaintiffs'

section 2 challenge. The court enjoined

e l ections in the challenged d i stricts

pending court approval of a . districting

7 plan which did not violate section 2. By

7 Appellees did not challenge all multi-

- 6 -

subsequent orders, the court approved the

State's proposed remedial districts for

six of the seven challenged districts. The

court entered a temporary order providing

for elections in 1984 only in one dis-

trict, former House District No. a; after

appellants • proposed remedial plan was

denied preclearance under section 5. The

remedial aspects of the litigation have

not been challenged and are not before

this Court. ·

On appeal appellants have disputed

the correctness of the three judge

district court's decision regarding the

legality of five of the six disputed

multi-member districts. Although appel-

lants have referred to some facts from

member districts used by the state and

the district court did not rule that the

use of multi-member districts is E.~r.

se illegal. The district court's oraer

!eaves untouched 30 multi-member districts

in the House and 13 in the Senate.

- 7 -

House District No. 8 and Senate District

No. 2, they have made no argument in their

Brief that is pertinent to the lower

court's decision concerning either of

these districts. 8 Like the United States,

we assume that the correctness of the

decision below regarding House District

No. 8 and Senate District No. 2 is not

within the scope of this appeal.

THE FINDINGS OF THE DISTRICT COURT

The gravamen of appellees' cl.aim

under section 2 is that minority voters in

the challenged multi-member districts do

not have an equal opportunity to partici-

pate effectively in the political process,

8 The Court did not note probable juris

diction as to Question II, the question in

the Jurisdictional Statement concerning

these two districts, and even the

Solicitor General concedes that there is

no basis for appeal as to these two

districts. u.s. Br. 11.

- 8 -

and particularly that they do not have an

equal opportunity to elect candidates of

their choice. Five of the challenged 1982

multi-member districts were the same as

had existed under the 1 971 plan, and the

one that was different, House District 39,

was only modified slightly. The election

results in those districts are undisputed.

Until 1972 no black since Reconstruction

had been elected to the legislature from

any of the counties in question. The

election results since 1972 are set forth

on the table on the opposite page. As

that table indicates, prior to 1982 no

more than 3 of the 32 l~gislators elected

in any oRe election in the challenged

districts were black; in 1981, when this

action was filed, five of the seven

districts were represented by all white

delegations, and three of the districts

still had never elected a black legisla-

BLACK CANDIDATES ELECTED

1972-1982

District Prior

(Number to

of Seats) 1972 1972 1974 1976 1978 1980 1982

House 8 ( 4) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

House 21 ( 6) 0 0 0 0 0 1

House 23 ( 3) 0 1 1 1 1 1 1

House 36 (8) 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

House 39 (5) 0 0 1 1 0 0 2

Senate 2*(2) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Senate 22 ( 4) . 0 0 1 1 1 0 0

TOTAL (32) -0- -,- ·-3- -r -2- -2- 5

Source: Stio. 95

JA 93-94

* Senate District 2 was part of a two member district through the

1980 election; but no county in Senate District 2 was ever in a

district which elected a black Senator.

- 9 -

tor. The black popuia t ion of the chal

lenged districts ranged from 21.8% to

39.5%. JA 21.

The district court held on the basis

of this record and its examination of

election results in local offices that

"[t)he overall results achieved to date

••• are minimal." JA 39. The court noted

that, following the filing of this action,

the number of successful black legislative

candidates rose sharply.

however, that the results

It concluded,

of the 1982

election were an aberration unlikely to

recur again. It emphasized in particular

that in a number of instances "the

pendency of this very litigation worked a

one-time advantage for black candidates in

the form of unusual organized political

support by white leaders concerned to

fo~estall single-member districting." JA

39 n.27.

- 10 -

The district court identified a

number of distinct practices which put

black voters at a comparative disadvantage

when placed in the six majority white

multi-member districts at issue. The

court noted, first, that the propo~tion of

white voters who ever voted for a black

candidate was extremely low; an average of

81% of white voters did not vote for any

black candidate in primary elections

involving both black and white candidates,

and those whites who did vote for black

candidates ranked them last or next to

last. JA 42. The court noted that in none

of the 53 races in which blacks ran for

office did a majority of whites ever vote

for a black candidate, and the sole

election in which 50% voted for the black

candidate was one in which that candidate

was running unopposed. JA. 43-48. The

district court concluded that this pattern

- 11 -

of polarized voting put black candidates

at a severe disadvantage in any race

against a white opponent.

The district court also concluded

that black voters were at a comparative

disadvantage because the rate of regist r a

tion among eligible blacks was substan

tially lower than among whites. This

disparity further diminished the ability

of black voters to make common cause with

sufficient numbers of like minded voters

to be able to elect candidates of their

choice. The court found that these

disparities in registration rates were the

lingering effect of a century of virulent

official hostility towards blacks who

sought to register and vote. The tactics

adopted for the express purpose of

disenfranchising blacks included a poll

tax, a 1 i teracy test with a grandfather

clause, as well as a number of devices

- 12 -

which discouraged registration by assuring

the defeat of black candidates. JA 25-26.

When the use of the state literacy test

ended after 1970, whites enjoyed a , 60.6%

to 44.6% registration advantage over

blacks. Thereafter registration was kept

inaccessible in many places, and a decade

later the gap had narrowed only slightly,

with white registration at 66.7%, and

b 1 a c k reg i strati on at 52 • 7% • J A 2 6 and

n.22.

The trial court held that the ability

of black voters to elect candidates of

their choice in majority white districts

was further impaired by the fact that

black voters were far poorer, and far more

often poorly educated, than white voters.

JA 28-31. Some 30% of blacks had incomes

below the poverty line, compared to 10% of

whites; conversely, whites were twice as

likely as blacks to earn over $20,000 a

- 13 -

year. Almost all blacks over 30 years old

attended inferior segregated schools. JA

29. The district court concluded that

this lack of income and education made it

difficult for black voters to elect

candidates of their choice. JA 31. n.23.

The record on which the court relied

included extensive testimony regarding the

difficulty of raising sufficient funds in

the relatively poor black community to

meet the high cost of an at-large cam

paign, which has to reach as many as eig~t

times as many voters as a single district

campaign. (See notes 107-109, infra).

The ability of minority candidates to

win white votes, the district court found,

was also impaired by the common practice

on the part of white candidates of urging

whites to vote on racial lines. JA 33-34.

The record on which the court relied

- 14 -

included such appeals in campaigns in

1976, 1980, 1982, and 1983. (See page 115,

infra). In both 1980 and 1983 white

candidates ran newspaper advertisements

depicting their opponents with black

leaders. In 1983 Senator Helms denounced

his opponent for favoring black voter

registration, and in a 1982 congressional

run-off white voters were urged to go to

the polls because the black candidate

would be "bussing" [sic] his "block" [sic]

vote. (See pp. 116-18, infra).

The district court, after an exhaus

tive analysis of this and other evidence,

concluded that the challenged multi-member

districts had the effect of submerging

black voters as a voting minority in those

districts, and thus affording them "less

opportunity than .•• other members of the

- 15 -

electorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of

their choice." JA 53-54. 9

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

was amended in 1982 to establish a

nationwide prohibition against election

practices with discriminatory results.

Specifically prohibited are practices that

afford minorities "~opportunity than

other members of the electorate to

participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice".

(Emphasis added). In assessing a claim of

unequal electoral opportunity, the courts

are required to consider the "totality of

circumstances". A finding of unequal

9 Based on similar evidence the court made a

parallel fiooi ng concerning the fracturing

of the minority community in Senate

District No. 2. JA 54.

- 16 -

opportunity is a factual finding subject

to Rule 52. Anderson v.City of Bessemer

City,_ U.S.__._ (1985).

The 1982 Senate Report specified a

number of specific factors the presence of

which, Congress believed, would have the

effect of denying equal electoral oppor

tunity to black voters in a majority white

multi-member district. The three-judge

district court below, in an exhaustive and

detailed opinion, carefully analyzed the

evidence indicating the presence of each

of those factors. In light of the

totality of circumstances established by

that evidence, the trial court concluded

that minority voters were denied equal

electoral opportunity in each of the six

challenged multi-member districts. The

court below expressly recognized that

section 2 did not require proportional

representation. JA 17.

- 17 -

Appellants argue here, as they did at

trial, that the presence of equal elec

toral opportunity is conclusively estab

lished by the fact blacks won 5 out of 30

at-large seats in 1982, 14 months after

the complaint was filed. Prior to 1972.,

however, although blacks had run, no

blacks had ever been elected from any of

these districts, and in the election held

immediately prior to the commencement of

this action only 2 blacks were elected in

the challenged districts. The district

court properly declined to hold that the

1982 elections represented a conclusive

change in the circumstances in the

districts involved, noting that in several

instances blacks won because of support

from whites seeking to affect the outcome

of the instant litigation. JA 39 n.27.

- 18 -

The Solicitor General urges this

Court to read into section 2 a per ~ rule

that a section 2 claim is precluded as a

matter of law in any district in which

blacks ever enjoyed "proportional repre

sentation", regardless of whether that

representation ended years ago, was

inextricably tied to single shot voting,

or occurred only after the commencement of

the litigation. This p~ ~approach is

inconsistent with the "totality of

circumstances" requirement of section 2,

which pcecludes treating any single factor

as conclusive. The Senate Report ex

pressly ~tated that the election of black

officials was not to be treated, by

itself, as precluding a section 2 claim.

s. Rep. No. 97-417, 29 n.115.

The district court correctly held

that there was sufficiently severe

polacized voting by whites to put minority

- 19 -

voters and candidates at an additional

d i sad vantage in the majority white

multi-member districts. On the average

more than 81% of whites do not vote f or

black candidates when they run i n primary

elect ions. JA 42. Black candidates

receiving the highest proportion of black

votes ordinarily receive the smallest

number of white votes. Id.

ARGUMENT

I. SECTION 2 PROVIDES MINORITY VOTERS

AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO ELECT REPRE

SENTATIVES OF THEIR CHOICE

Two decades ago Congress adopted the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 in an attempt to

end a century long exclusion of most

blacks from the electoral process. In

1981 and 1982 Congress concluded that,

despite substantial gains in registration

s ince 1965, minorities still did not enjoy

t he s ame opportunity as whites to parti-

- 20 -

cipate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice, 10and

that further remedial legislation was

necessary to eradicate all vestiges of

discrimination from the political pro-

11 cess. The problems identified by Congress

included not only the obvious impediments

to minority participation, such as

registration barriers, but also election

schemes such as those at-large elections

which impair exercise of the franchise and

dilute the voting strength of minority

citizens. Although some of these practices

had been corrected in certain jurisdic-

t ions by operation of the preclearance

provisions of Section 5, Congress con-

10 s. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.,

34 (1982} (hereinafter cited as "Senate

Report"}.

11 Senate Report 40; H.R. Rep. No. 97-227,

97th Cong., 1st Sess., 31 (1981} (here

inafter cited as "House Report").

- 21 -

eluded that their eradication required the

adoption, in the form of an amendment to

Section 2, of a . 1 12 h . b . . ~t1o~ pro 1 1t1on

against practices with discriminatory

results. 13 Section 2 protects not only the

right to vote, but also "the right to have

the vote counted at full value without

dilution or discount." Senate Report 19.

A. Legislative History of the 1982

Amendment to Section 1

The present language of section 2 was

adopted by Congress as part of the Voting

Rights Act Amendments of 1982. (96 Stat.

1 3 1 ) • The 1 982 amend.ments altered the

Voting Rights Act in a number of ways,

12 House Report, 28; senate Report . 15.

13 Appellants and the Solicitor General

concede that the framers of the 1982

amendments established a standard of proof

in vote dilution lawsuits based on

discriminatory results alone. Appellants'

Br. at 16; u.s. Brief II at 8, 13.

- 22 -

extending the pre-clearance requirements

of section 5, modifying the bailout

requirements of section 4, continuing

until 1992 the language assistance

provisions of the Act, and adding a new

requirement of .assistance to blind,

disabled or illiterate voters. Congres-

sional action to amend section 2 was

prompted by this Court's decision in

Mob i l e v • Bo 1 den, · 4 4 6 U • S • 55 , 6 0-6 1

(1980), which held that the original

language of section 2, as it was framed in

1 96 5, fore bade only election practices

adopted or maintained with a discrimina-

tory motive. Congress regarded the

decision in Bolden as an erroneous

i n t e r pre t a t ion of section 2 , 1 4 and thus

acted to amend the language to remove any

such intent requirement.

---------

14 House Rep. at 29; Senate Report at 19.

- 23 -

Legislative proposals to extend the

Voting Rights Act in 1982 included from

the outset language that would eliminate

the intent requirement of Bolden and apply

a totality of circumstances test to

practices which merely had the effect of

discriminating on the basis of race or

color. 15 Support for such an amendment was

repeatedly voiced during the extensive

House hearings and much of this testimony

was concerned with at-large election plans

that had the effect of diluting the impact

of minority votes. 16 On July 31 the House

1 5 H. R. 311 2 , 97th Co ng . 1 1 s t S e s s • , § 2 0 1 ;

H.R. 3198, 97th Cong., 1st Sess., § 2.

16 The three volumes of Hearings before the

Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Judiciary Committee,

97th Cong. 1 1st Sess., are hereinafter

cited as "House Hearings." Testimony

regarding the proposed amendment to

section 2 can be found at 1 House

He a r i ng s 1 8- 1 9 , 1 3 8 , 1 9 7 , 2 2 9 , 3 6 5 ,

424-25, 454, 8 52; 2 House Hearings 90 5-07 1

993-95,1279, 1361, 1641; 3 House Hearings

1880, 1991, 2029-32, 2036-371 2127-28,

2136, 2046-471 2051-58.

- 24 -

Judiciary Committee approved a bill that

extended the Voting Rights Act and

included an amendment to section 2 to

remove the intent requirement imposed by

Bolden. 17 The House version included an

express disclaimer to make clear that the

mere lack of proportional representation

would not constitute a violation of the

law, and the House Report directed the

courts not to focus on any one factor but

17 House Report, 48:

"No voting qualification or prere

quisite to voting, or standard, practice,

or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any state or political subdivision [to

deny or abridge] in a manner which results

in a qenial or a6ri<lgment of the right oT

any c1tizen to vote on account of race or

color, or in contravention of the guaran

tees set forth in section 4(b)(2). The

fa~t that .members of a minority group

nave not 6een e!ected in num6ers

~~ual to tfie grout's proportion ·-or

t e fop u 1 at ion s fi a I . not , i n and of

i tsei, constitute a viOlation of this

s~ction."

- 25 -

to look at all the relevant circumstances

in assessing a Section 2 claim. H. Rep.

at 30.

The House Report set forth the

committee's reasons for disapproving any

intent requirement, and described a

variety of practices, particularly the use

of at-large elections 18and limitations on

h . nd 1 f . . 19 . h t e t1mes a paces o· reg1strat1on, w1 t

whose potentially discriminatory effects

the Committee was particularly concerned.

On the floor of the House the proposed

amendment to section 2 was the subject of

considerable debate. Representative

Rodino expressly called the attention of

the House to this portion of the bill, 20 to

which he and a number of other speakers

18 Hous e Report, 17-19, 30.

19 Id. 14, 16, 17, 30, 31 n.105.

20 128 Cong. Rec. H 6842 (daily ed. · Oct. 2,

1981) .

gave 21 support.

- 26 -

Proponents of section 2

emphasized its applicapility to multi-

member election districts that diluted

minority votes, and to burdensome regis-

. nd . . 22 A b f trat1on a vot 1 ng pract 1ces. num er o

speakers opposed the proposed alteration

. 2 3 . . .

to sect1on 2, and Representat1ve Bl1ley

moved that the amendment to section 2 be

deleted from the House bill. The Bliley

2 1 1 2 8 Co ng • Re c • H 6 8 4 2 ( Rep • Rod i no ) , H

6843 (Rep. Sensenbrenner), H 6877 (Rep.

Chisholm) (daily ed.; Oct. 2, 1981); 128

Cong. Rec. H 7007 (Rep. Fascell)(daily

ed. , Oct. 5, 1 9 81 ) •

22 128 Cong. Rec. H 6841 (Rep. Glickman;

dilution), H 6845-6 (Rep. Hyde; registra

tion barriers), H 6847 (Rep. Bingham;

voting practices, dilution); H 6850 (Rep.

Washington, registration and voting

barriers); H 6851 (Rep. Fish, dilution)

(daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981).

23 128 Cong. Rec. H 6866 (Rep. Collins), H

6874 (Rep. Butler) (daily ed., Oct. 2,

1981); 128 Cong. Rec. H 6982-3 (Rep.

Bliley), H 6984 (Rep. Butler, (Rep.

McClory), H 6985 (Rep. Butler) (daily ed. 1

Oct. 5 1 1981) •

- 27 -

amendment was defeated on a voice vote. 24

Following the rejection of that and other

amendments the House on October 5, 1981

passed the bill by a margin of 389 to 24.

25

On December 16, 1981, a Senate bill

essentially identica l to the House passed

bill was introd uced by Senator Mathias.

The Senate bill, S. 199 2, had a total of 61

initial sponsors, far more than were

necessary to assure passage. 2 Senate

Hearings 4, 3 0, 15 7. The particular

subcommittee to which S.1992 was referred,

however, wa s dominated by Senators who

were high l y critical of the Voting Rights

Act arne ndme nts. After extensive hear-

24 128 Cong. Rec. Fi 6 (-H$2-85 {daily ed., Oct.

5, 1981).

25 Id. at H6985.

- 28 -

ings, 26most of them devoted to section 2,

the subcommittee recommended passage of

S.1992, but by a margin of 3-2 voted to

delete the proposed amendment to section

2. 2 Senate Hearings 10. In the full

commit tee Senator Dole proposed language

which largely restored the substance of s.

1992; included in the Dole proposal was

the language of section 2 as it was

ultimately adopted. The Senate Commmittee

issued a lengthy report describing in

detail the purpose and impact of the

section 2 amendment. Senate Report 15-42.

The report expressed concern with two

distinct types of practices with poten-

tially discriminatory effects--first,

restrictions on the times, places or

26 Id. Heari ngs be f ore the Subcommitee on

tne Constitution of the Senate Judiciary

Committee on S.53, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1982) (hereinafter cited as "Senate

Hear i ng s " ) •

- 29 -

methods of registration or voting, the

burden of which would fall most heavily on

. . . 27 d d 1 . m1nor1t1es, an , secon , e ect1on systems

such as those multi-member districts which

reduced or nullified the effectiveness of

minority votes, and impeded the ability of

minority voters to elect candidates of

their choice. 28 The Senate debates leading

to approval of the section 2 amendment

29 reflected similar concerns.

The Senate report discussed the

various types of evidence that would bear

on a section 2 claim, and insisted that

the courts were to consider all of this

evidence and that no one type of evidence

27 Senate Report, 30 n.119.

28 Senate Report, 27-30.

29 128 Cong. Rec. S 6783 (daily ed. June 15,

1982)(Sen. Dodd); 128 Cong. Rec. S 7111

(daily ed. June 18, 1982) (Sen. Met

zenbaum), S7113 (Sen. Bentsen), S 7116

(Sen. Weicker), _ S 7137 (Sen. Robert

Byrd) .

- 30 -

should be treated as conclusive. 30 Both the

Senate Report and the subsequent debates

make clear that it was the intent of

Congress, in applying the amended section

2 to multi-member districts, to reestab-

lish what it understood to be the totality

of circumstances test that had been estab-

lished by White v.Regester, 412 u.s. 755

(1973), 31 and that had been elaborated upon

by the lower courts in the years .between

White and Bolden. 32 The most important and

frequently cited of the courts of appeals

d . 1 . . M . h 33 1 ut1on cases was Z1mmer v. cKe1t en,

30 Senate Report, 23, 27.

31 Senate Report, 2, 27, 28, 30, 32.

32 Senate Report, 16, 23, 23 n.78, 28, 30,

31 , 32.

33 Zimmer was described by the Senate Report

as a "seminal" decision, id. at 22, and

was cited 9 times in the Report. Id. at

22, 24, 24 n.86, 28 n.112, 28 n. 1TI, 29

n • 1 1 5 , 2 9 n • 1 1 6 , 3 0 , 3 2 , 3 3 • S e na tor

DeConcini, one of the framers of the Dole

proposal, described Zimmer as "[p]erhaps

the clearest expression of the standard of

- 31 -

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)(en bane),

aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish School

Board v. Marshall, 424 u.s. 636 (1976).

The decisions applying White are an

important source of guidance in a section

2 dilution case.

The legislative history of section 2

focused repeatedly on the possibly

discriminatory impact of multi-member

districts. Congress was specifically

concerned that, if there is voting along

racial lines, black voters in a majority

white multi-member district would be

unable to compete on an equal basis with

whites for a role in electing public

officials. Where that occurs, the white

majority is able to determine the outcome

of elections and white candidates are able

proof in theoe vote dilution cases." 128

Cong. Rec. S6930 (daily ed. June 17,

1982).

- 32 -

to take positions without regard to the

votes or preferences of black voters,

rendering the act of voting for blacks an

empty and ineffective eitual. The Senate

Repoet described in detai l the types of

ciecumstances, based on the White/Zimmer

factoes, undee which blacks in a multi

membee disteict would be less able than

whites to elect representatives of their

choice. Senate Report, 28-29.

The Solicitor General, in support of

his contention that a section 2 claim may

be decided on the basis of a single one of

the seven Senate Report factors--electoral

success--regardless of the totality of the

ciecumstances, offees an account of the

legislative histoey of section 2 which is,

in a number of eespects, substantially

i naccu rate. Fiest, the Sol ici toe asseets

that, when the amended veesion of S. 1992

was eeported to the full Judiciary

- 33 -

Commit tee, there was a "deadlock." U.s.

Br. I, 8; Br. II, 8 n.12. The legislative

situation on May 4, 1982 when the Dole

proposal was offered, could not conceiv-

ably be characterized as a "deadlock," and

was never so described by any supporter of

the pr-oposal. The entire Judiciary

Committee favored reporting out a bill

amending the Voting Rights Act, and fully

two thirds of the Senate was committed to

restoring the House results test if the

Judiciary Committee failed to do so.

Critics of the original S.1992 had neither

the desire nor the votes to bottle up the

bill in Committee, 34and clearly lacked the

votes to defeat the section 2 amendment on

the floor of the Senate. The leading

34 2 Senate Hearings 69 (Sen. Hatch)

(" [W] hatever happens to the proposed

amendment, I intend to support favorable

reporting of the Voting Rights Act by this

Commit tee")

- 34 -

Senate opponent of the amendment acknowl-

edged that passage of the amendment had

been foreseeable "for many months" prior

to the full Committee's action. 35 Senator

Dole commented, when he offered his

proposal, that "without any change the

House bill would have passed." 2 Senate

Hearings 57. Both supporters 36 and oppo

nents37of section 2 alike agreed that the

35 2 Senate Hearings 69 (Sen. Hatch).

36 Senate Report, 27 (section 2 "faithful to

the basic intent" of the House bill); 2

S e n a t e Hear i ng s 6 0 ( S e n. Do 1 e ) ( " [ T ] he

compromise retains the results standards

of the Mathias/Kennedy bill. However, we

also feel that the legislation should be

strengthened with additional language

delineating what legal standard should

apply under the results test ••• ") ( Empha

sis added), 61 (Sen. Dole) (language

"strengthens the House-passed ·bill") 68

(Sen. Biden)(new language merely "clari

fies" 8.1992 and "does not change much"),

128 Cong. Rec. S6960-61 (daily ed. June

17, 1982) (Sen. Dole); 128 Cong. Rec.

H3840 (daily ed. June 23, 1982) (Rep.

Edwards) •

37 2 Senate Hearings 70 (Sen. Hatch) ("The

proposed compromise is not a compromise at

all, in my opinion. The impact of the

- 35 -

language proposed by Senator Dole and

ultimately adopted by Congress was

intended not to water down the original

House bill, but merely to spell out more

explicitly the intended meaning of

legislation already

House. 38

approved by the

The Solicitor urges the Court to give

little weight to the Senate Report

accompanying S.1992, describing it as

proposed compromise is not likely to be

one whit different than the unamended

House measure" relating to section 2; .

Senate Report, 95 (additional views of

Sen. Hatch); 128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed.

June 9, 1982) S 6515, S.6545 (Sen. Hatch);

128 CODJ. Rec. (daily ed. June 10, 1982) S

6725 (Sen. East); 128 Cong. Rec. (daily

ed., June 15, 1982) S.6786 (Sen. Harry

Byrd).

38 The compromise language was designed to

reassure Senate cosponsors that the White

v. Regester totali ty of circumstances test

e-naorsed in the House, and espoused

throughout the Senate hearings by sup-

porters of the House passed bill, would be

codified in the statute itself. 2 Senate

Hearings 60; Senate Report, 27.

- 36 ..:..

merely the work of a faction. u.s. Br. I,

8 n.6; u.s. Br. II, 8 n.12, 24 n.49.

Nothing in the legislative history of

section 2 supports the Solicitor's

suggestion that this Court should depart

from the long established principle that

committee reports are to be treated as the

most authoritative guide to congressional

intent. Garcia v. United States, 105

S.Ct. 479, 483 (1984). Senator Dole, to

whose position the Solicitor would give

particular weight, prefaced his Additional

Views with an acknowledgement that "[T]he

Committee Report is an accurate statement

of the intent of S.1992, as reported by

the Commit tee." 39 On the floor of the

Senate both supporters and opponents of

39 Senate Report 193; see also id. at 196 ("I

express my views not to ta~ issue with

the body of the report") 199 ("I concur

with the interpretation of this action in

the Committee Report."), 196-98 (addi

tional views of Sen. Grassley).

- 37 -

section 2 agreed that the Committee report

constituted the authoritative explanation

of the legislation. 40 Until the filing of

its briefs in this case, it was the

consistent contention of the Department of

Justice that in interpreting section 2

"[t]he Senate Report. •• is entitled to

greater weight than any other- oE the

legislative history." 41 Only in the spring

of 1985 did the Department reverse its

position and assert that the Senate report

was merely the view of one faction that

40 128 Cong. Rec. S6553 (daily ed., June 9,

1982)(Sen. Kennedy); S6646-48 (daily ed.

June 10, 1982) {Sen. Kennedy); S6781 (Sen.

Dole)(daily ed. June 15, 1982); S6930-34

(Sen. DeConcini), S6941 7 44, S6967 (Sen.

Mathias), S6960, 6993 (Sen. Dole), S6967

S6991-93 (Sen. Stevens), S6995 (Sen.

Kennedy)(daily ed. June 17, 1982);

57091-92 (Sen. Hatch), 57095-96 (Sen.

Kennedy) (daily ed., r.June 18, 1982).

41 Post-Trial Brief for the United States of

America, County Council of Sumter County,

South Carolina v. United States, No.

82-0912 {D.D.C.), 31.

- 38 -

"cannot be taken as determinative on all

co u nts." u.s. Br. I, p. 24, n.49. This

newly formulated account of the legisla-

tive history of section 2 is clearly

incorrect.

The Solicitor urges that substantial

weight be given to the views of Senator

h 42 nd h. 1 . 1 . . 43 Hate , a 1s eg1s at1ve ass1stant. In

fact, however, Senator Hatch was the most

intransigient congressional critic of

amended section 2, and he did not as the

42 In an amicus brief in ~ity Council of the

City of Chicago v. Ketchum, No. 84-~~7,

rererreo"to ln his brief in this case,

u.s. Br. II 21 n.43, the Solicitor asserts

that Senator Hatch "supported the com

promise adopted by Congress." Brief for

United States as Amicus, 16 n.15.

43 The Solicitor cites for a supposedly

authoritative summary of the origin and

meaning of sec t ion 2 an article written by

Stephen Markman. U.S. Br. II, 9, 10.

Mr . Markman is the chief counsel of the

Judiciary Subcommittee chaired by Senator

Hatch, and was Senator Hatch 1 s chief

assistant in Hatch 1 s unsuccessful opposi

tion to the amendment to section 2.

- 39 -

Solicitor suggests support the Dole

proposal. On the contrary, Senator Hatch

urged the Judiciary Committee to reject

44 the Dole proposal, and was one of only

four Committee members to vote against

' t 45 1 • Following the Committee's action,

Senator Hatch appended to the Senate

Report Additional Views objecting to this

modified version of section 2. 46 On the

floor of the Senate, Senator Hatch

supported an unsuccessful amendment that

would have struck from the bill the

amendment to section 2 that had been

adopted by h C . 47 d t e omm1ttee, an again

de nou need the language which eventually

44 2 Senate Hearings 70-74.

45 Id. 85-86.

46 Senate Report, 94-101.

47 128 Cong. Rec. S6965 (daily ed. June 17,

1 982) •

- 40 -

48 became law.

Finally, the Solicit6r urges that the

views of the President regarding section 2

should be given "particular weight"

because the President endorsed the Dole

proposal, and his "support for the

compromise ensured its passage." u.s. Br.

I, 8 n.6. We agree with the Solicitor

General that the construction of section 2

which the Department of Justice now

proposes in its amicus brief should be

considered in light of the role which the

Administration played in the adoption of

this legislation. But that role is not,

as the Solicitor asserts, one of a key

sponsor of the legislation, without whose

48 Immediately prior to the final vote on the

bill, Senator Hatch stated, "these

amendments promise to effect a destructive

transformation in the Voting Rights Act."

128 Cong. Rec. S7139 (daily ed. June 18,

1982); 128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June 9,

1982) S6506-21.

- 41 -

support the bill could not have been

adopted. On the contrary, the Admi nis-

tration in general, and the Department of

Justice in particular, were throughout the

legislative process among the most consis-

tent, adamant and outspoken opponents of

the proposed amendment to section 2.

Shortly after the passage of the

House bill, the Administration launched a

concerted attack on the decision of the

House to amend section 2. On November 6,

1981, the President released a statement

denouncing the "new and untested 1 effects 1

standard," and urging that section 2 be

limited to instances of purposeful

discrimination, 2 Senate Hearings 763,

a position Mr. Reagan strongly redffirmed

at a prf:'-~s c onference on December 17.

49

When in ,1 <J. :,ua:cy i 982 the Senate commenced

4 9 New York Times 1 Dec • 1 8 1 1 9 8 1 , p . B 7 ,

col. 4.

- 42 -

hearings on proposed amendments to the

Voting Rights Act, the Attorney General

appeared as the first witness to denounce

section 2 as "just bad legislation,"

objecting in particular to any proposal to

apply a results standard to any state not

covered by section 5. Senate Hearings

70-97. At the close of the Senate

Hearings in early March the Assistant

Attorney General for Civil Rights gave

extensive testimony in opposition to the

adoption of the totality of circumstances/

results test. Id., at 1655 et seq. Both

Justice Department officials made an

effort to solicit public opposition to the

results test, publishing critical analyses

in several national newspapers 50and, in the

50 2 Senate Hearings 770 (Assistant At

torney General Reynolds) (Washington

Post), 774 (Attorney General Smith) (

Op-ed article, New York Times), 775

(Attorney General Smith) ( Op-ed article,

Washington Post).

- 43 -

case of the Attorney General, issuing a

warning to members of the United Jewish

Appeal that adoption of a results test

would lead to court ordered racial quo-

51 tas. The White House did not endorse the

Dole proposaJ. until after it had the

support of 13 of the 18 members of the

Judiciary Committee and Senator Dole had

warned publicly that he had the votes

necessary to override any veto. 52

Having failed to persuade Congress to

reject a results standard in section 2,

the Department of ,Justice now seeks to

persuade this court to adopt an interpre-

tation of section 2 that would severely

limit the scope of that provision. Under

these unusual circumstances the Depart-

--·-------

51 Id. at 780.

52 Los Angeles Time s, May 4, 1982, p. 1; Wall

S t r e e t Jour na 1 , May 4 , 1 9 8 2 , p • 8 ; 2

Senate Hear1ngs 58.

- 44 -

ment's views do not appear to warrant the

weight that might ordinarily be appro-

priate. We believe that greater deference

should be given to the views expressed in

an amicus brief in this case by Senator

Dole and the other principal cosponsors of

section 2.

B. ~q~al Electoral Opportunity is

~ Statutory Standard

Section 2 provides that a claim of

unlawful vote dilution is established if,

"based on the totality of circumstances,"

members of a racial minority "have less

opportunity than other members to partici-

pate in the political process and to elect

. f h . h . " 53 h representat1ves o t e1r c o1ce. In t e

instant case the district court concluded

that minority voters lacked such an equal

opportunity. JA 53-54.

53 42 U.S.C. S 1973, Section 2(b) is set

. forth in the opinion below, JA 13.

- 45 -

Both appellants and the Solicitor

General suggest, however, that section 2

is limited to those extreme cases in which

the effect of an at-large election is to

render virtually impossible the election

of public officials, black or otherwise,

favored by minority voters. Thus appel

lants assert that section 2 forbids use of

a multi-member district when it "effec

tively locks the racial minority out of

the political forum," A. Br. 44, or

"shut[s] racial minorities out of the

electoral process" Id. at 23. The Soli

citor invites the Court to hold that

section 2 applies only where minority

candidates are "effectively shut out of

the political process". U.S. Br. II 27;

see also id. at 11. On this view, the

election of even a single black candidate

would be fatal to a section 2 claim.

- 46 -

The requirements of section 2,

however, are not met by an election scheme

which merely accords to minorities some

minimal opportunity to participate in the

political process. Section 2 requires

that "the political processes leading to

nomination or election" be, not merely

open to minority voters and candidates,

but "equally open". (Emphasis added). The

prohibition of section 2 is not limited to

those systems which provide minorities

with no access whatever to the political

process, but extends to systems which

afford minorities "less opportunity than

other members of the electorate to

participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice."

(Emphasis added).

This emphasis on equality of opportu

nity was reiterated throughout the

legislative history of section 2. The

- 47 -

Senat~ report insisted repeatedly that

s ~ction 2 required equality of political

. 54 s t l opportun1ty. ena or Do e, in his

54 s. Rep. 97-417, p. 16 ("equal chance to

participate in the electoral pro cess";

"equal access to the electoral process")

20 ("equal access to the political

process"; at-large elections invalid if

they give minorities "less opportunity

than ..• other residents to participate in

th~ political processes and to elect

legislators of their choice"), 21 (plain

titfs .must prove they "had less opportu

nity than did other residents in the

district to participate in the political

processes and to elect legislators of

their choice"), 27 (denial of "equal

access to the political process"), 28

(minority voters to have "the same

opportunity to participate in the politi

cal process as other citizens enjoy";

minority voters entitled to "an equal

opportunity to participate in the

politcal processes and to elect candi

dates of their choice"), 30 ("denial of

equal access to any phase of the electoral

process for minority voters"; standard is

whether a challenged practice "operated

to deny the minority plaintiff an equal

opportunity to participate and elect

candidates of their choice"; process must

be "equally open to participation by the

group in question"), 31 (remedy should

assure "equal opportunity for minority

citizens to participate and tp elec~

candidates of their choice").

- 48 -

Additional Views, endorsed the committee

report, and reiterated that under the

language of section 2 minority voters were

to be given "the same opportunity as

others to participate in the political

process and to elect the candidates of

their choice". 55 Senator Dole and others

repeatedly made this point on the floor of.

the Senate. 56

The standard announced in White v.

Regester was clearly one of equal oppor-

tu ni ty, prohibiting at-1 arge elect ions

which afford minority voters "less

opportunity than ••• other residents in

55 Id. at 194 (emphasis omitted); See also

TO. at 193 ("Citizens of all racesare

entitled to have an equal chance of

electing candidates of their choice •••• 11

),

194 ("equal access to the political

process).

56 128 Cong. Rec. S6559 , S6560 (Sen.

Kennedy)(daily ed. June 9, 1982); daily

ed. June 17, 1982); 128 Cong. Rec.

S7119-20 (Sen. Dole), (daily ed. June 18,

1982).

- 49 -

the district to participate in the

political processes and to elect legisla-

tors of their choice." 412 u.s. at 765.

(Emphasis added). The Solicitor General

asserts that during the Senate hearings

three supporters of section 2 described it

as "merely a means of ensuring that

minorities were not effectively 'shut out'

of the electoral process". u.s. Br. II,

11. This is not an accurate description

f h . . d b h l. . 57 o t e test1mony c1te y t e So 1c1tor.

57 David Walbert stated that ·minority

voters had had "no chance" to win elec

tions in their earlier successful

dilution cases, 1 Senate Hearings 626,

but also noted that the standard under

White was whether minority voters had an

..,.equal opportunity" to do so. Id. Senator

Kennedy stated that under section 2

minorities could not be "effectively shut

out of a fair opportunity to participate

in the elect1on". Id. at 223. Clearly a

"fair" opportunityis more than any

minimal opportunity. Armand Derfner did

use the words "shut out", but not, as the

Solicitor does, followed by the clause "of

the political process". Id. at 810. More

importantly, both in his-oral statement

( i d • at 7 9 6 , , 8 0 0 ) a nd h i s prepared

statement (id. at 811, 818) Mr. Derfner

- 50 -

Even if it were, the remarks of three

witnesses would carry no weight where they

conflict with the express language of the

bill, the committee report, and the

consistent statements of supporters. Ernst

and Ecnst v. Hochfelde~, 425 u.s. 185, 204

n.24 (1976).

C. The Election of Some Minority

Candidates Does Not Conclusively

Establish The Existence Ot Equal

Political Opportunity

The c~ntral argument advanced by the

Solicitor General and the appellants is

that the election of a black candidate in

a multi-member district conclusively

establishes the absence of a section 2

violation. The Solicitor asserts, u s.

Br. I 13-14, that it is not sufficient

that there is underrepresentation now, or

expressly endorsed the equal opportunity

standard.

- 51 -

that there was underrepresentation for a

century prior to the filing of the action;

on the Solicitor's view there must at all

times have been underrepresentation. Thus

the Solicitor insists there is no vote

dilution in Senate District 22, which has

not elected a black since 1978, and that

there can be no vote dilution in House

District 36, because, of eight represen-

tatives, a single black, the first this

century, was elected there in 1982 after

this litigation was filed.

This interpretation of section 2 is

plainly inconsistent with the language and

legislative history of the statute.

Section 2(b) directs the courts to

consider "the totality of circumstances,"

an admonition which necessarily precludes

giving conclusive weight to any single

. 58 " 1 ' f . circumstance. The tota 1ty o c1rcum-

58 The Solicitor's argument also flies in the

- 52 -

stances" standard was taken from White v.

Regester, which Congress intended to

codify in section 2. The House and Senate

reports both emphasize the importance of

considering the totality of circumstances,

rather than focusing on only one or two

portions of the record. Senate Report 27,

34-35; House Report, 30. The Senate .

Report sets out a number of "[t]ypical"

factors to be considered in a dilution

case, 59 of which "the extent to which

members of the minority group have been

face of the language of section 2 which

disavows any intent to establish propor

tional representation. On the Solicitor's

view, even if there is in fact a denial of

equal opportunity, blacks cannot prevail

in a section 2 action if they have, or

have ever had, proportional representa

tion. Thus proportional representation,

spurned by Congress as a measure of

liability, would be resurrected by the

Solicitor General as a type of affirmative

defense.

59 The factors are set out in the opinion

below. JA 1 5.

- 53 -

elected to public office in the juris-

diction" is only one, and admonishes

"there is no requirement that any partie-

ular number of factors be proved, or that

•

a majority of them point one way or the

other." Senate Report 28-29. 60 Senator

Dole, in his additional views acpompanying

the committee report, makes this plain.

!

"The extent to which members of a pro-

tected class have been elected under the

challenged practice or structure is just

one factor, among the totality of circum-

stances to be considered, and is not

dispositive."

added) . 61

Id. at 194. (Emphasis

60 See also Senate Report 23 ("not every one

o f the factor s ne eds to be proved in ucuer

to obtain re l ief").

61 128 Cong. Rec. 56961 (daily ed. June 17,

1982) (Sen. Dole); 128 Cong. Rec. S7119

(daily ed. June 18, 1982) (Sen. Dole).

- 54 -

The arguments of appellants and the

Solicitor General that any minority

electoral success should foreclose a

section 2 claim were expressly addressed

and rejected by Congress. The Senate

Report explains, "the election of a few

minority candidates does not 'necessarily

foreclose the possibility of dilution of

the black vote.'" I d • at 2 9 n. 1 1 5 • Both

White v. Regester and its progeny, as

Congress well knew, had repeatedly

disapproved the contention now advanced by

appellants and the Solicitor. 62 In White

itself, as the Senate Report noted, a

total of two blacks and five hispanics had

62 "The results test, codified by the

committee bill, is a well-established

one, familiar to the courts. It has a

reliable and reassuring track record,

which completely belies claims that it

would make proportional reeresentata

tion the standard tor avoid1ng a vio

latio,n." (Emphasis added). 1:l8Cong. Rec.

86559 (Sen. Kennedy) (daily ed. June 9,

1982).

- 55 -

been elected from the two multi-member

districts invalidated in that case. Senate

Report 22. Zimmer v. McKeithen, in a

passage quoted by the Senate Report, had

refused to treat "a minority candidate's

success at the polls [a]s conclusive." ~·

at 29 n.115. The decision in Zimmer is

particularly important because in that

case the court ruled for the plaintiffs

despite the fact that blacks had won

two-thirds of the seats in the most recent

at-large election. 485 F.2d at 1314. The

dissenters in Zimmer unsuccessfully made

the same argument now advanced by appel

lants and the Solicitor, insisting "the

election of three black candidates

pretty well explodes any notion that black

voting strength has been cancelled or

minimized". 485 F.2d at 1310 (Coleman,

J. , dissenting) . A number of other

lower court cases implementing White had

- 56 -

also refused to attach conclusive weight

to the election of one or more minority

d ' d 63 can 1 ates.

There are, as Congress anticipated, a

variety of circumstances under which the

election of one or more minority can-

didates might occur despite an absence of

63 Kirksey v. Board of surervisors, 554 F.2d

139, 149 n.21 (5th C1r. 1977); Cross v.

Baxter, 604 F.2d 875, 880 n.7, 885 (5th

Cir. 1979); United States v. Board of

Supervisors of Forrest County, 571 F.2d

951, 956 (5th C1r. 1978); Wallace v.

House, 515 F.2d 619, 623 n.2 (5th Cir.

1975). See also Senator Hollings'

comments on the district court decision in

McCain v. Lybrand, No. 74-281 (D.S.C.

April 17, 1980), finding a voting rights

violation despite some black participation

on the school board and other bodies. 128

Cong. Rec. 86865-66 (daily ed. June 16,

1975). In post-1982 section 2 cases, the

courts have also rejected the contention

that the statute only applies where

minorities are completely shut out. See

~·, United States v. Marengo Cou~

Commission, 731 F.2d 1546, 1571-72 (11t

Cir. 1984), cert. denied, 105 s.ct. 375

(1984); Velasrz v. City of Abilene, 725

F.2d 1017, 10 3 (5th Cir. 1984); Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. f983)

(three-judge court).

- 57 -

the equal electoral opportunity required

by the statute. A minority candidate

might simply be unopposed in a primary or

general election, or be seeking election

in a race in which there were fewer white

candidates than there were positions to be

filled. 64 White officials or political

64 The Solicitor General suggests that the

very fact that a black candidate is

unopposed conclusively demonstrates that

the candidate or his or her supporters

were simply unbeatable. u.s. Br. ir, 22

n.46, 33. But the number of white

potential candidates who choose to enter a

particular at-large race may well be the

result of personal or political considera

tions entirely unrelated to the circum

stances of any minority candidate.

Evidence that white potential candidates

were deterred by the perceived strength of

a minority candidate might be relevant

rebuttal evidence in a section 2 action,

but here appellants offered no such

evidence to explain the absence of a

sufficient number of white candidates to

contest all the at-large seats. More

over, in other cases, the Department of

Justice has urged courts to find a

violation o f section 2 notwithstanding the

election of a bla c k candidate running

unopposed. See Unite d States v. Marengo

Count~ Commiss1on (S.D. Ala.) No.

7S-47 H, Proposed Findings of Fact and

Conclusions o f Law for the United States,

- 58 -

leaders, concerned about a pending or

threatened section 2 action, might .

engineer the election of one or more

minority candidates for the purpose of

preventing the imposition of single member

districts. 65 The mere fact that minority

candidates were elected would not mean

that those successful candidates were the

representatives preferred by minority

filed June 21, 1985, p. 8.

65 Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d at 1307:

"Such success might, on occasion, be

attributable to the work of poli

ticians, who, apprehending that the

support of a black candidate would

be politically expedient, campaign

to insure his election. Or such

success might be attributable to

political support motivated by

different considerations--namely

that election of a black candidate

will thwart successful challenges to

electoral schemes on dilution

grounds. In either situation, a

candidate could be elected despite

the relative political backwardness

of black residents in the electoral

district."

- 59 -

voters. The successful minority candi-

dates might have been the choice, as in

White v. Regester, 412 u.s. at 755; Senate

Report, 22, of a white political organiza-

tion, or might have been able to win and

retain office only by siding with the

white community on, or avoiding entirely,

those issues about which whites and

non-whites disagreed. Even where minority

voters and candidates face severe inequal-

ity in opportunity, there will occasion-

ally be minority candidates able to

overcome those obstacles because of

exceptional ability or "a 'stroke of luck'

h . h . t 1 . k 1 t b t d " 66 w 1c 1s no 1 e y o e repea e •..•

The election of a black candidate may

also be the result of "single shooting",

which deprives minority voters of any vote

at all in every at-large election but one.

66 Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 623 n.2

(5th Ctr. 1975).

- 60 -

In multi-member elections for the North

Carolina General Assembly where there are

no numbered seats, voters may typically

vote for as many candidates as there are

vacancies. Votes whi~h they cast for their

second or third favorite candidates,

however, may result in the victory of that

candidate over the voters' first choice. 67

Where voting is along racial lines, the

only way minority voters may have to give

preferred candidates a serious chance of

victory is to cast only one of their

ballots, or "single shoot," and relinquish

any opportunity at all to influence the

67 This is especially true in North Carolina

where, because of the multiseat electoral

system, a candidate may need votes from

more than 50% of the voters to win. For

example, in the Forsyth Senate primary in

1980, there were 3 candidates for 2 seats.

If the votes were spread evenly and all

voters voted a full slate, each candidate

would get votes from 2/3 or 67% of the

voters. In such circumstances it would

take votes from more than 67% of the

voters to win. N.C.G.S. 163.111 (a) (2).

- 61 -

1 . f h h 1 ff . . 1 68 e ect1on o t e ot er at- arge o 1c1a s.

Where single shot voting is necessary

to elect a black candidate, black voters

are forced to limit their franchise in

order to compete at all in the political

process. This is the functional equiva-

lent of a rule which permitted white

voters to cast five ballots for five

at-large seats, but required black voters

to abnegate four of those ballots in order

to cast one ballot for a black candidate.

68 For example, in 1978, in Durham County,

99% of the black voters voted for no one

but the black candidate, who won. JA Ex.

Vol. I Ex. 8. In Wake County in 1978,

approximately 80% of the black voters

supported the black candidate, but

because not enough of them single shot

voted the black candidate lost. The next

year, after substantially more black

voters concentrated their votes on the

black candidate, forfeiting their right to

vote a full slate, the first black was

elected. Similarly in Forsyth County when

black voters voted a full slate in 1980,

. the black candidate lost. It was only

after many black voters declined to vote

for any white candidates that black

candidates were elected ·in 1982. Id.

- 62 -

Black voters may have had some opportunity

to elect one representative of their

choice, but they had no opportunity

whatever to elect or influence the

election of any of the other representa

tives.69 Even where the election of one or

more blacks suggests the possible ex i s -

tence of some electoral opportunities for

minorities, the issue of whether those

opportunities are the same as the oppor-

69 There is no support for appellants' claim

that white candidates need black support

to win at-large. Black votes were not

important for successful white can

didates. Because of the necessity of

single shot voting, in most instances

black voters were unable to affect the

outcome of other than the races of the few

blacks who won. For example, white

candidates in Durham were successful with

only 5% of the votes cast by blacks in

1978 and 1982; in Forsyth, white can

didates in 1980 who received less than 2%

of the black vote were successful, and in

Mecklenburg in 1982, the leading white

senate candidate won the general

election although only 5% of black voters

voted for him. Id. See, JA 244.

- 63 -

tunities afforded to whites can only be

resolved by a distinctly local appraisal

of all other relevant evidence.

These complex possibilities make

clear the wisdom of Congress in requiring

that a court hearing a section 2 claim

must consider "the totality of circum-

stances," rather than only considering the

extent to which minority voters have, or

have not, been underrepresented in one or

more years. Congress neither deemed

conclusive the election of minority can-

didates, nor directed that such vic-