McCleskey v. Kemp Order

Public Court Documents

November 23, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCleskey v. Kemp Order, 1987. 8ef01e66-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ebbede40-ed1a-460e-80be-c90deb8bbc94/mccleskey-v-kemp-order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

V

l

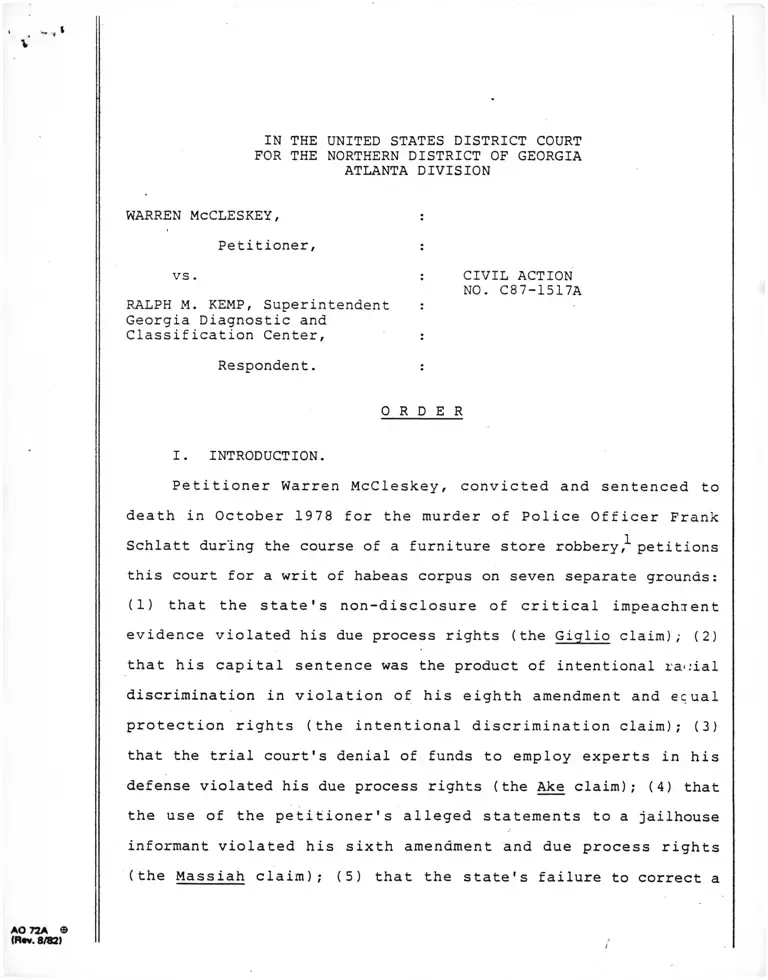

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ATLANTA DIVISION

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner,

vs.

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent

Georgia Diagnostic and

Classification Center,

Respondent.

O R D E R

I. INTRODUCTION.

Petitioner Warren McCleskey, convicted and sentenced to

death in October 1978 for the murder of Police Officer Frank

Schlatt during the course of a furniture store robbery,'1' petitions

this court for a writ of habeas corpus on seven separate grounds:

(1) that the state's non-disclosure of critical impeachment

evidence violated his due process rights (the Giglio claim); (2)

that his capital sentence was the product of intentional racial

discrimination in violation of his eighth amendment and ecual

protection rights (the intentional discrimination claim); (3)

that the trial court's denial of funds to employ experts in his

defense violated his due process rights (the Ake claim); (4) that

the use of the petitioner's alleged statements to a jailhouse

informant violated his sixth amendment and due process rights

(the Massiah claim); (5) that the state's failure to correct a

CIVIL ACTION

NO. C87-1517A

A 0 72A ®

(R*v. 8/82)

witness's misleading testimony violated his eighth amendment and

due process rights (the Mooney claim); (6) that the state's

reference to appellate review in its closing argument violated

his eighth amendment and due process rights (the Caldwell claim);

and (7) that the state's systematic exclusion of black jurors

violated his sixth amendment and equal protection rights (the

Batson claim).

For the reasons discussed below, the petition for a writ of

habeas corpus will be granted as to the Massiah claim but denied

as to all other claims. In Part II of this order the court will

detail the history of the petitioner's efforts to avoid the death

penalty. Then, because the successive nature of this petition

dominates the court's discussion and will be dispositive of many

of the issues raised by the petition, Part III will set out the

general principles of finality in habeas corpus actions. Next,

the court will address each of the seven claims raised in this

petition; first, the successive claims ir Part IV (the Giglio,

intentional discrimination, and Ake claims) and then the new

claims in Part V (the Massiah, Mooney, laldwel1, and Batson

claims). Finally, in Part VI, the court v'ill address the peti

tioner's other pending motions -- a motion for discovery and a

motion to exceed page limits.

II. HISTORY OF PRIOR PROCEEDINGS.

The petitioner was convicted and sentenced in the Superior

Court of Fulton County on October 12, 1978. The convictions and

sentences were affirmed by the Supreme Court of Georgia.

AO 72A ©

(R«v. 8/82)

-2-

I

McCleskey v. State, 245 Ga. 108 (1980). The United States

Supreme Court then denied a petition for certiorari, McCleskey v.

Georgia, 449 U.S. 891 ( 1980 ). On December 19, 1980, the peti

tioner filed an extraordinary motion for a new trial in Fulton

County Superior Court, but no hearing has ever been held on that

motion. On January 5, 1981 the petitioner filed a petition for

writ of habeas corpus in the Butts County Superior Court. On

April 8, 1981, that court denied all relief. On June 17, 1981

the Georgia Supreme Court denied the petitioner's application for

a certificate of probable cause to appeal. The United States

Supreme Court again denied a petition for a writ of certiorari.

McCleskey v. Zant, 454 U.S. 1093 (1981).

McCleskey filed his first federal habeas corpus petition in

this court on December 30, 1981. This court held an evidentiary

hearing in August and October 1983 and granted habeas corpus

relief on one issue on February 1, 1984. McCleskey v. Zant, 580

F. Supp. 338 (N.D.Ga. 1984). The Eleventh Circuit reversed and

denied the habeas corpus petition on January 29, 1985. McCleskey

v. Kemp, 753 F.2d 877 (11th Cir. 1985) (en banc). - This time the

United States Supreme Court, granted certiorari and affirmed the

Eleventh Circuit on April 12, 1987. McCleskey v. Kemp, ___ U.S.

___, 107 S.Ct. 1756, petition for rehearing denied, ___ U.S. ___,

107 S.Ct. 3199 (1987). McCleskey filed a successive petition for

a writ of habeas corpus in the Butts County Superior Court on

June 9, 1987, and a First Amendment to the Petition on June 22,

1987 (Civil Action No. 87-V-1028). That court granted the

AO 72A ®

(R«v. 8/82) -3-

state's motion to dismiss the petition on July 1, 1987. The

Georgia Supreme Court denied the petitioner's application for a

certificate of probable cause to appeal on July 7, 1987 (Ap

plication No. 4103).

This court issued an order on June 16 , 1987 making the

mandate of the Eleventh Circuit the judgment of this court and

lifting the stay of execution that had been entered when the

first federal habeas corpus petition was filed. On July 7, 1987

McCleskey filed the present petition for a writ of habeas corpus,

a request to proceed in forma pauperis, a motion for discovery,

and a motion for a stay of execution. The court granted the

request to proceed in forma pauperis and held an evidentiary

hearing on the petition on July 8 and 9, 1987. At that time, the

court granted the motion for a stay of execution. The court took

further evidence in a hearing on August 10, 1987 and, at the

close of the evidence, requested post-hearing briefs from the

parties. Tnose briefs have since been filed and the petitioner's

claims are ripe for determination.

III. THE DOCTRINE OF FINALITY IN HABEAS CORPUS PETITIONS.

Althoagh successive petitions for a writ of habeas corpus

are not subject to the defense of res judicata, Congress and the

courts have fashioned a "modified doctrine of finality" which

precludes a determination of the merits of a successive petition

under certain circumstances. Bass v. Wainwright, 675 F.2d 1204,

1206 (11th Cir. 1982 ). In particular, Congress has authorized

the federal courts to decline to address the merits of a petition

-4-AO 72A ©

(R*v. 8/82)

if the claims contained therein were decided upon the merits

previously or if any new grounds for relief that are asserted

should have been raised in the previous petition. 28 USC

§-2244(a) & (b). The habeas rules have described these distinct

applications of the doctrine of finality as follows:

A second or successive petition may be dismissed if the judge finds that it fails to

allege new or different grounds for relief

and the prior determination was on the merits

or, if new and different grounds are alleged,

the judge finds that the failure of the

petitioner to assert those grounds in a prior

petition constituted an abuse of the writ.

28 USC foil. §2254, Rule 9(b).

A purely successive petition or successive claim raises

issues which have been decided adversely on a previous petition.

The court may take judicial notice of allegations raised by a

previous petition. See Allen v. Newsome, 795 F.2d 934, 937 (11th

Cir. 1986). Rule 9(b) requires that the issue raised by the

previous petition must have been decided adversely to the

petitioner on the merits before the doctrine of finality obtains.

A merits determination need not be a determination made after an

evidentiary hearing if the facts material to the successive claim

were undisputed at the time of the previous petition. Bass, 675

F.2d at 1206.

A truly successive petition may be distinguished from the

second category of petitions subject to the finality doctrine:

petitions alleging new claims that may be an "abuse of the writ."

28 USC §2244 (b) ; 28 USC foil. §2254, Rule 9(b). The state has

-5-

%

the burden of pleading abuse of the writ; the burden then shifts

to the petitioner to show that he has not abused the writ. Price

v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266, 292-93 (1948); see also Allen v.

Newsome, 795 F .2d 934, 938-39 (11th Cir. 1986). To meet his

burden, a petitioner must "give a good excuse for not having

raised his claims previously." Allen 794 F.2d at 93 9 . An

evidentiary hearing on an abuse of the writ defense is not

necessary if the record affords an adequate basis for decision.

Price, 334 U.S. at 292-93.

As this circuit has articulated the issue presented by an

abuse of the writ defense, "[a] district court need not consider

a claim raised for the first time in a second habeas petition,

unless the petitioner establishes that the failure to raise the

claim earlier was not the result of intentional abandonment or

withholding or inexcusable neglect." Adams v. Dugger, 816 F.2d

1493, 1494 (11th Cir. 1987) (citations omitted). See also Moore

v. Kemp, 824 F.2d 847, 851 (11th Cir. 1987). There are a number

of instances in which failure to raise an issue in a prior

petition is excusable. "A retroactive change in the law and newly

discovered evidence are examples." 28 USC foil. §2254, Rule 9

Advisory Committee Notes. See, e.g., Ritter v. Thigpen, 828 F.2d

662 , 665 ( 11th Cir. 1987 ); Adams, 816 F.2d at 1495. Of course,

failure to discover evidence supportive of a claim prior to the

first petition may itself constitute inexcusable neglect or

AO 72A ®

(R*V. 8/82)

-6-

Cf. Freeman v. Georgia, 599 F.2d 65, 71-72deliberate bypass. _______________

(5th Cir. 1979) (no procedural default where petitioner was

misled by police and could not have uncovered evidence supportive

of a claim in any event).2

Even if a particular claim is truly successive or, if it is

a new claim, is an abuse of the writ, a court may consider the

merits of the claim if "the ends of justice" would be served

thereby. See Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1, 16 (1963)

(successive claim); id. at 18 (new claim); Smith v. Kemp, 715

F.2d 1459, 1468 (11th Cir. 1983) (successive claim); Moore v.

Kemp, 824 F.2d at 856 (new claim). The burden is upon the

petitioner to show that the ends of justice would be served.

Sanders, 373 U.S. at 17.

The "ends of justice" exception has been subject to dif

fering interpretations. The Court in Sanders suggested some

circumstances in which the "ends of justice" would be served by

re-visiting a successive claim:

If factual issues are involved, the applicant

is entitled to a new hearing upon a showing

that the evidentiary hearing on the prior

application was not full and fair; we

canvassed the criteria of a full and fair

evidentiary hearing recently in Townsend v.

Sain, [372 U.S. 293 (1963)], and that

discussion need not be repeated here. If

purely legal questions are involved, the

applicant may be entitled to a new hearing

upon showing an intervening change in the law

or some other justification for having failed

to raise a crucial point or argument in the

prior application. ... [T]he foregoing

enumeration is not intended to be exhaustive;

the test is "the ends of justice" and it

cannot be too finely particularized.

-7-

373 U.S. at 16-17. This circuit has traditionally followed the

Sanders articulation of the "ends of justice" exception. See,

e . g. , Moore v. Kemp, 824 F.2d at 856; Smith v. Kemp, 715 F.2d at

1468 .

'A plurality of the Supreme Court recently challenged this

open-ended definition of "the ends of justice,"- arguing that a

successive claim should not be addressed unless the petitioner

"supplements his constitutional claim with a colorable showing of

factual innocence." Kuhlmann v. Wilson, ___ U.S. ___, 106 S.Ct.

2616, 2627 (1986) (Opinion of Powell, J., joined by Burger,

Rehnquist, and O'Connor, JJ.). Under this definition of the

"ends of justice," the petitioner "must make his evidentiary

showing even though ... the evidence of guilt may have been

unlawfully admitted." Id. That is, petitioner must "show a fair

probability that, in light of all the evidence, including that

alleged to have been illegally admitted (but with due regard to

any unreliability of it) and evidence tenably claimed to have

been wrongfully excluded or to have become available only after

trial, the trier of facts would have entertained a reasonable

doubt of his guilt." Id. n. 17 (quoting Friendly, Is Innocence

Irrelevant? Collateral Attack on Criminal Judgments, 3 8

U.Chi.L.Rev. 142 (1970)).

Following Kuhlmann, "[i]t is not certain what standards

should guide a district court in determining whether the 'ends of

justice' require the consideration of an otherwise dismissable

successive habeas petition." Moore, 824 F.2d at 856. The

//

-8-

Eleventh Circuit, in Moore, declined to decide "whether a

colorable showing of factual innocence is a necessary condition

for the application of the ends of justice exception." Id. The

court merely held that, "at a minimum, the ends of justice will

demand consideration of the merits of a claim on a successive

petition where - there is a colorable showing of factual inno

cence." Id.

IV. PETITIONER'S SUCCESSIVE CLAIMS.

Three of the petitioner's claims in this second federal

habeas petition duplicate claims in the first federal petition

and are therefore truly successive claims that should be dis

missed according to the dictates of Rule 9(b) unless the peti

tioner can show that the "ends of justice" justify re-visiting

the claims. Each claim will be discussed in turn.

A. Giglio Claim.

Petitioner's Giglio claim is based upon the state's failure

to disclose its agreement with a witness, Offie Evans, which led

him to testify against petitioner at trial. McCleskey argues

that the state's failure to disclose the promise by a police

detective to "speak a word" for Offie Evans with regard to an

escape charge violated McCleskey's due process rights under

Giglio v. United States, 405 U.S. 150 (1971). Giglio held that

failure to disclose the possible interest of a government witness

will entitle a defendant to a new trial if there is a reasonable

likelihood that the disclosure would have affected the judgment

of the jury. Id. at 154. This court granted habeas corpus

AO 72A ®

(H*v. 8/82)

-9-

relief on this claim in passing upon the first federal habeas

petition, but the Eleventh Circuit reversed en banc. McCleskey

v- Zant, 580 F. Supp. at 380-84, rev'd sub nom. McCleskey v.

Kemp, 753 F.2d at 885.

McCleskey argues that the ends of justice require re

visiting his Giglio claim for three reasons. He argues that the

discovery of a written statement by Offie Evans provides new

evidence of a relationship between Offie Evans and the state

supportive of a finding of a quid pro quo for Offie Evans'

testimony. He also proffers the affidavit testimony of jurors

who indicate that they might have reached a different verdict had

they known the real interest of Offie Evans in testifying against

petitioner. Finally, petitioner contends that there has been a

change in the law regarding the materiality standard for a

finding of a Giglio violation.

None of these arguments is sufficient to justify re-visiting

the Giclio claim. The written statement of Offie Evans offers no

new evidence of an agreement by state authorities to do Offie

Evans < favor if he would testify against petitioner. Conse

quently, the conclusion of the Eleventh Circuit that the de

tective ' s promise did not amount to a promise of leniency

triggering Giglio is still valid. See McCleskey v. Kemp, 753

F . 2d at 885 . Because the threshold showing of a promise still

has not been made,. the ends of justice would not be served by

allowing petitioner to press this claim again.

-10-

Petitioner also has no newly discovered evidence with

respect to the materiality of the state's failure to disclose its

arrangement with Offie Evans. The affidavit testimony of the

j.urors is not evidence that petitioner could not have obtained at

the time of the first federal habeas petition. In any event, a

juror is generally held incompetent to testify in impeachment of

a verdict. Fed. R. Evid. 606(b); Proffitt v. Wainwriqht, 685

F.2d 1227, 1255 (11th Cir. 1982). See generally McCormick on

Evidence §608 (3d Ed. 1984).

Finally, petitioner can point to no change in the law on the

standard of materiality. The Eleventh Circuit concluded in this

case that there was "no 'reasonable likelihood' that the State's

failure to disclose the detective's [promise] affected the

judgment of the jury." McCleskey, 753 F.2d at 884. The same

standard still guides this circuit in its most recent decisions

on the issue. See, e.g., United States v. Burroughs, No.

86-3566 , Slip Op. at 381 (11th Cir., Nov. 3, 1987); Brown, 785

F.2d at 1464 (citing McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F.2d at 885).

B. Intentional Discrimination Claim.

Having lost in the Supreme Court^ on his contentions re

garding the Baldus Study, the petitioner nevertheless trotted it

out to support the more narrow contention that McCleskey was

singled out both because he is black and because his victim was

white.

-11-

The Baldus Study is said to be the most ambitious yet. It

is. The part of it that is ambitious, however -- the 230-vari-

able model structured and validated by Dr. Baldus -- did not

adduce one smidgen of evidence that the race of the defendants or

the race of the victims had any effect on the Georgia prose

cutors' decisions to seek the death penalty or the juries'

decisions to impose it. The model that Dr. Baldus testified

accounted for all of the neutral variables did not produce any

"death-odds multiplier" of 4 or 6 or 11 or 14 or any of the other

numbers which the media have reported.

To be sure, there are some exhibits that would show discrim

ination and do 'contain such multipliers. But these were not

produced by the "ambitious" 230-variable model of the study. The

widely-reported "death-odds multipliers" were produced instead by

arbitrarily structured little rinky-dink regressions that

accounted for only a few variables. They are of the sort of

statistical analysis given short shrift by courts and social

scientists alike in the past. They prove nothing other than the

truth of the adage that anything may be proved by statistics.

The facts are that the only evidence of over-zealousness or

improprieties by any person(s) in the law enforcement estab

lishment points to the black case officers of the Atlanta Bureau

of Police Services, ̂ which was then under the leadership of a

black superior who reported to a black mayor in a majority black

city. The verdict was returned by a jury on which a black person

sat and, although McCleskey has adduced affidavits from jurors on

AO 72A ©

(Rtv. 8/82)

- 12 -

other subjects, there is no evidence that the black juror voted

for conviction and the death penalty because she was intimidated

by the white jurors. It is most unlikely that any of these black

citizens who played vital roles in this case charged, convicted

or sentenced McCleskey because of the racial considerations

alleged.

There is no other evidence that race played a part in this

case.

C. Ake Claim.

Petitioner's last truly successive claim is based upon the

trial court's denial of his request for the provision of funds

for experts, particularly for a ballistics expert. Petitioner

alleges that this ruling by the trial court denied him his right

to due process of law as guaranteed by the fourteenth amendment.

Petitioner raised this same claim in the first federal habeas

petition and this court held that the claim was without merit.

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp. at 388-89 (citing Me ore v. Zant,

722 F . 2d 640 (11th Cir. 1983 )). At that time the law held that

the appointment of experts was generally a matte.' within the.

discretion of the trial judge and could not form the basis for a

due process claim absent a showing that the trial judge's-

decision rendered the defendant's trial fundamentally unfair.

Moore, 722 F.2d at 648 . With that case law in mind, this court

concluded that the state trial court had not abused its dis

cretion because the petitioner had the opportunity to subject

-13-

the state's ballistics expert to cross-examination and because

there was no showing of bias or incompetence on the part of the

state's expert. McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp. at 389.

Arguing that the ends of justice require re-visiting the

claim, petitioner points to the cases of Ake v. Oklahoma, 470

U.S. 68, 83 (1985) and Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 323

n. 1 (1985) (plurality), as examples of a change in the law

regarding the provision of experts. It may be that these cases

did change the law; this matter, which was traditionally thought

to rest within the discretion of state trial judges, now has

heightened constitutional significance. Compare Moore v. Zant,

722 F . 2d at 648 , with Moore v. Kemp, 809 F.2d 702, 709-12 (11th

Cir. 1987).

Even so, this new law does not justify re-visiting this

claim. The new Supreme Court cases require "that a defendant

must show the trial court that there exists a reasonable proba

bility both that an expert would be of assistance to the defense

and that denial of expert assistance would result in a funda

mentally unfair trial. Thus, if a defendant wants an expert to

assist his attorney in confronting the prosecution's proof ... he

must inform the court of the nature of the prosecution's case and

how the requested expert would be useful." Moore v. Kemp, 809

F . 2d at 712. A review of the state trial record indicates that

petitioner did nothing more than generally refer to the extensive

expert testimony available to the state. Petitioner then

specifically requested the appointment of a psychiatric expert.

AO 72A ©

(R»v. 8/82)

-14-

The petitioner never specifically requested the appointment of a

ballistics expert, nor did he make the showing that this circuit

has held is required by Ake and Caldwell. The state trial court

could hardly have been expected to appreciate the importance of a

ballistics expert to petitioner's case if petitioner himself

neither requested such an expert nor explained the significance

of such an expert to the court.

V. PETITIONER'S NEW CLAIMS.

A . Massiah Claim.

1. Findings of Fact.

Petitioner relies primarily on the testimony of Ulysses

Worthy before this court and the recently disclosed written

statement of Offie Evans to support his Massiah claim. Ulysses

Worthy, who was captain of the day watch at the Fulton County

Jail during the summer of 1978 when petitioner was being held

there awaiting his trial for murder and armed robbery, testified

before this court or. July 9 and August 10, 1987. The court will

set out the pertinent parts of that testimony and then summarize

the information it i eveais.

On July 9, Worthy testified as follows: He recalled

"something being jaid" to Evans by Police Officer Dorsey or

another officer about engaging in conversations with McCleskey

(II Tr. 147-49).5 He remembered a conversation, where Detective

Dorsey and perhaps other officers were present, in which Evans

was asked to engage in conversations with McCleskey (II Tr. 150).

-15-

Later, Evans requested permission to call the detectives (II Tr.

151). Assistant District Attorney Russell Parker and Detective

Harris used Worthy's office to interview Evans at one point,

which could have been the time they came out to the jail at

Evans' request (Id.).

In other cases, Worthy had honored police requests that

someone be placed adjacent to another inmate to listen for

information (II Tr. 152); such requests usually would come from

the officer handling the case (Id.); he recalled specifically

that such a request was made in this case by the officer on the

case (II Tr. 153). Evans was put in the cell next to McCleskey

at the request of the officer on the case (Id.); "someone asked

[him] to specifically place Offie Evans in a specific location in

the Fulton County Jail so he could overhear conversations with

Warren McCleskey," but Worthy did not know who made the request

and he was not sure whether the request was made when Evans

first came into the jail (II Tr. 153-54); he did not recall when

he was asked to move Evans (II Tr. 155-56).

On August 10, 1987 Worthy testified as follows: Evans was

first brought to his attention when Deputy Hamilton brought Evans

to Worthy's office because Evans wanted to call the district

attorney or the police with "some information he wanted to pass

to them" (III Tr. 14). The first time the investigators on the

Schlatt murder case talked to Evans was "a few days" after Evans'

call (III Tr. 16-17). That meeting took place in Worthy's office

(III Tr. 17). Worthy was asked to move Evans "from one cell to

-16-

who asked, "but itanother" (III Tr. 18). Worthy was "not sure"

would have had ... to have been one of the officers," Deputy

Hamilton, or Evans (III Tr. 18-19). Deputy Hamilton asked

Worthy to move Evans "perhaps 10, 15 minutes" after Evans'

interview with the investigators (III Tr. 20). This was the

first and only time Worthy was asked to move Evans (Id.). Deputy

Hamilton would have been "one of the ones" to physically move

Evans (III Tr. 22). Worthy did not know for a fact that Evans

was ever actually moved (Id.). The investigators later came out

to interview Evans on other occasions, but not in Worthy's

presence (III Tr. 23). Neither Detectives Harris, Dorsey or

Jowers nor Assistant District Attorney Parker ever asked Worthy

to move Evans (III Tr. 24).

On cross-examination, Worthy re-affirmed portions of his

July 9 testimony: He overheard someone ask Evans to engage in

conversation with McCleskey at a time when Officer Dorsey and

another officer were present (III Tr. 32-33). Evans requested

permission to call the investigators after he was asked to engage

in conversation with McCleskey (III Tr. 33). Usually the case

officer would be the one to request that an inmate be moved and

that was the case with Evans, though he does not know exactly who

made the request (III Tr. 46-48). Worthy also contradicted

portions of his July 9 testimony, stating that the interview at

which Assistant. District Attorney Parker was present was the

first time Evans was interviewed and that Worthy had not met

Officer Dorsey prior to that time (III Tr. 36). On further

-17-

cross-examination, Worthy testified as follows: Deputy Hamilton

was not a case officer but was a deputy at the jail (III Tr. 49).

When Worthy testified on July 9 he did not know what legal issues

were before the court (III Tr. 52-53 ). After his July 9 testi

mony he met with the state's attorneys on two occasions for a

total of forty to fifty minutes (III Tr. 53-54). After his

July 9 testimony he read a local newspaper article mentioning him

(III Tr. 56 ) .

In response to questions from the court, Worthy stated that

he was satisfied that he was asked for Evans "to be placed near

McCleskey's cell," that "Evans was asked to overhear McCleskey

talk about this case," and that Evans was asked to "get seme

information from" McCleskey (III Tr. 64-65). Worthy maintained

that these requests were made on the date that Assistant

District Attorney Parker interviewed Evans, but he could not

explain why the investigators would have requested a move on the

same day that Evans had already told the investigators that he

was next to McCleskey, that he had been listening to vrlat

McCleskey had been saying, and that he had been asking McClcshey

questions (III Tr. 64).

In summary, Worthy never wavered from the fact that somec-e,

at some point, requested his permission to move Evans to be near

McCleskey. Worthy's July 9 testimony indicates the following

sequence: The request to move Evans, the move, Evans' request to

call the investigators, the Parker interview, and other later

interviews. Worthy's August 10 testimony indicates a different

AO T2A ®

<R*v. 8/82)

-18-

sequence: Evans' request to call the investigators, the Parker

interview, the request to move Evans by Deputy Hamilton, and

other later interviews. Worthy's testimony is inconsistent on

O.fficer Dorsey's role in requesting the move, on whether Deputy

Hamilton requested the move, and on whether the request to move

Evans preceded Evans' request to call the investigators. Worthy

has no explanation for why the authorities would have requested

to move Evans after the Parker interview, at which Evans made it

clear that he was already in the cell adjacent to McCleskey's.

All of the law enforcement personnel to whom Worthy informed

-- Deputy Hamilton, Detectives Dorsey, Jowers and Harris, and

Assistant District Attorney Parker -- flatly denied having

requested permission to move Evans or having any knowledge of

such a request being made (III Tr. 68-71; 80-81, 95; 97-98;

102-03; 111-12, 116). It is undisputed that Assistant District

Attorney Parker met with Evans at the Fulton County Jail on only

one occasion, July 12, 1978 , and that Evans was already in the

cell next to McCleskey's at that time (III Tr. 113-14; 71-72).

Petitioner also relies on Evans' twenty-oie page statement

to the Atlanta Police Department, dated August 1, 1978, in

support of his claim that the authorities deliberately elicited

incriminating information from him in violation of his sixth

amendment right to counsel. Evans' statement relates conversa

tions he overheard between McCleskey and McCleskey's co-defendant

DuPree and conversations between himself and McCleskey from

July 9 to July 12, 1978. McCleskey's statements during the

-19-

course of those conversations were highly incriminating. In

support of his argument that the authorities instigated Evans'

information gathering, McCleskey points to the methods Evans used

to secure McCleskey's trust and thereby stimulate incriminating

conversation. Evans repeatedly lied to McCleskey, telling him

that McCleskey's co-defendant, Ben Wright, was Evans' nephew;

that Evans' name was Charles; that Ben had told Evans about

McCleskey; that Evans had seen Ben recently; that Ben was

accusing McCleskey of falsely identifying Ben as the "trigger

man" in the robbery; that Evans "used to stick up with Ben too;"

that Ben told Evans that McCleskey shot Officer Schlatt; and that

Evans was supposed to have been in on the robbery himself.

In addition, McCleskey argues that Evans' knowledge that

McCleskey and other co-defendants had told police that co

defendant Ben Wright was the trigger person demonstrates Evans'

collusion with the police since that fact had not been made

public at that time. Finally, McCleskey points to two additional

pieces of evidence about Evans' relationship with the police:

Evans testified at McCleskey's trial that he had talked to

Detective Dorsey about the ca i e before he talked to Assistant

District Attorney Parker (Per. Exh. 16 at 119); and Evans had

acted as an informant for Detective Dorsey before (II Tr. 52-3).

The factual issue for the court to resolve is simply stated:

Either the authorities moved Evans to the cell adjoining

McCleskey's in an effort to obtain incriminating information or

they did not. There is evidence to support the argument that

-20-

Evans was not moved, that he was in the adjoining cell fortu

itously, and that his conversations with McCleskey preceded his

contact with the authorities. Worthy's testimony is often

c.onfused and self-contradictory, it is directly contrary to the

testimony of Deputy Hamilton and Detective Dorsey, it is contrary

to Evans' testimony at McCleskey' s trial that he- was put in the

adjoining cell "straight from the street" (Trial Tr. 873), and it

is contrary to the opening line of Evans' written statement

which says, "I am in the Fulton County Jail cell # 1 north 14

where I have been since July 3, 1978 for escape." Worthy himself

testified that escape risks where housed in that wing of the jail

(III Tr. 13-14). Moreover, the. use of Evans as McCleskey

alleges, if it occurred, developed into a complicated scheme to

violate McCleskey*s constitutional rights — its success required

Evans and any officers involved to lie and lie well about the

circumstances. For these reasons, the state asks this court to

reject Worthy's testimony that someone requested permission to

move Evans next to McCleskey's cell.

After caiefully considering the substance of Worthy's

testimony, his demeanor, and the other relevant evidence in this

case, the court concludes that it cannot reject Worthy's testi

mony about the fact of a request to move Of fie Evans. The fact

that someone, at some point, requested his permission to move

Evans is the one fact from which Worthy never wavered in his two

days of direct and cross-examination. The state has introduced

no affirmative evidence that Worthy is either lying or mistaken.

-21-

The lack of corroboration by other witnesses is not surprising;

the other witnesses, like Assistant District Attorney Parker, had

no reason to know of a request to move Evans or, like Detective

Dorsey, had an obvious interest in concealing any such arrange

ment. Worthy, by contrast, had no apparent interest or bias that

would explain any conscious deception. Worthy's testimony that

he was asked to move Evans is further bolstered by Evans'

testimony that he talked to Detective Dorsey before he talked to

Assistant District Attorney Parker and by Evans' apparent

knowledge of details of the robbery and homicide known only to

the police and the perpetrators.

Once it is accepted that Worthy was asked for permission to

move Evans, the conclusion follows swiftly that the sequence of

events to which Worthy testified originally must be the correct

sequence; 'i.e., the request to move Evans, the move, Evans'

request to call the investigators, the Parker interview, and

other later interviews. There are two other possible con

clusions about the timing of the request to move Evans, but

neither is tenable. First, the request to move Evans could have

come following Evans' meeting with Assistant District Attorney

Parker, as Worthy seemed to be testifying on August 10 (III Tr.

20). However, a request at that point would have been non

sensical because Evans was already in the cell adjoining

McCleskey's. Second, it could be that Evans was originally in the

cell next to McCleskey, that he overheard the incriminating

statements prior to any contact with the investigators, that

-22-

McCleskey was moved to a different cell, and that the authorities

then requested permission to move Evans to again be adjacent to

McCleskey. As the state concedes, this possibility is mere

speculation and is not supported by any evidence in the record.

Post-Hearing Brief at 53.

For the foregoing reasons, the court concludes' that peti

tioner has established by a preponderance of the evidence the

following sequence of events: Evans was not originally in the

cell adjoining McCleskey's; prior to July 9, 1978, he was moved,

pursuant to a request approved by Worthy, to the adjoining cell

for the purpose of gathering incriminating information; Evans was

probably coached in how to approach McCleskey and given critical

facts unknown to the general public; Evans engaged McCleskey in

conversation and eavesdropped on McCleskey's conversations with

DuPree; and Evans reported what he had heard between July 9 and

July 12, 1978 to Assistant District Attorney Parker on July 12.

2. Abuse of the Writ Questions.

The state argues that petitioner's Mass iah claim in this

second federal habeas petition is an abuse of the writ because he

intentionally abandoned the claim after his first state habeas

Petition and because his failure to raise this claim in his first

federal habeas petition was due to inexcusable neglect. As was

Noted earlier, the burden is on petitioner to show that he has

^Ot abused the writ. Allen, 795 F.2d at 938-39. The court

-:l*'inc ludes that petitioner's Mass iah claim is not an abuse of the

> Ut.

-23-

First, petitioner cannot be said to have intentionally-

abandoned this claim. Although petitioner did raise a Massiah

claim in his first state petition, that claim was dropped because

it was obvious that it could not succeed given the then-known

facts. At the time of his first federal petition, petitioner was

unaware of Evans' written statement, which, as noted above,

contains strong indications of an ab initio relationship between

Evans and the authorities. Abandoning a claim whose supporting

facts only later become evident is not an abandonment that "for

strategic, tactical, or any other reasons ... can fairly be

described as the deliberate by-passing of state procedures." Fay

v • No i a, 372 U.S. 391 , 439 ( 1963), quoted in Potts v. Zant, 638

F.2d 727, 743 (5th Cir. 1981). Petitioner's Massiah claim is

therefore not an abuse of the writ on which no evidence should

have been taken. This is not a case where petitioner has

reserved his proof or deliberately withheld his claim for a

second petition. Cf. Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1, 18

(1963). Nor is the petitioner now raising an issue identical to

one he earlier considered without merit. Cf. Booker v. Wain-

wriqht, 764 F .2d 1371, 1377 (11th Cir. 1985).

Second, petitioner's failure to raise this claim ;.n his

first federal habeas petition was not due to his inexcusable

neglect. When the state alleges inexcusable neglect, the focus

is on "the petitioner's conduct and knowledge at the time of the

preceding federal application. ... He is chargeable with

counsel's actual awareness of the factual and legal bases of the

-24-

/

claim at the time of the first petition and with the knowledge

that would have been possessed by reasonably competent counsel at

the time of the first petition." Moore, 824 F.2d at 851. Here,

petitioner did not have Evans' statement or Worthy's testimony at

the time of his first federal petition; there is therefore no

inexcusable neglect unless "reasonably competent counsel" would

have discovered the evidence prior to the first federal petition.

This court concluded at the evidentiary hearing that petitioner's

counsel's failure to discover Evans' written statement was not

inexcusable neglect (I Tr. 118-19). The same is true of coun

sel's failure to discover Worthy's testimony. Petitioner's

counsel represents, and the state has not disputed, that counsel

did conduct an investigation of a possible Massiah claim prior to

the first federal petition, including interviewing "two or three

jailers." Petitioner's Post-Hearing Reply Brief at 5. The state

has made no showing of any reason that petitioner or his counsel

should have known to interview Worthy specifically with regard to

the Massiah claim. The state argues that petitioner's counsel

should have at least interviewed Detectives Harris and Dorsey and

Deputy Hamilton. Given that all three denied any knowledge of a

request to move Evans next to McCleskey, it is difficult to see

how conducting such interviews would have allowed petitioner to

assert this claim any earlier. See Ross v. Kemp, 785 F.2d 1467,

1478 (11th Cir. 1986) (remanding for evidentiary hearing on

-25-

inexcusable neglect where petitioner's counsel may have relied on

misrepresentations by the custodian of the relevant state

records).

In short, the petitioner's Massiah claim as it is currently

framed is not an abuse of the writ because it is distinct from

the Massiah claim originally raised in his first state petition

and because it is based on new evidence. Petitioner's failure to

discover this evidence earlier was not due to inexcusable

neglect. Because this claim is not an abuse of the writ it is not

a successive petition under section 2244(b) and therefore the

court need not inquire whether the petitioner has made a color

able showing of factual innocence, if that showing is now the

equivalent of the "ends of justice." Kuhlmann, 106 S.Ct. at

2628 n. 18.

3. Conclusions of Law.

The Eleventh Circuit recently summarized the petitioner's

burden in cases such as this:

In order to establish a violation of the

Sixth Amendmer. t in a jailhouse informant

case, the accused must show (1) that a fellow

inmate was a government agent; and (2) that

the inmate de:iberately elicited incriminating stateim r.ts from the accused.

Lightbourne v. Dugger, 829 F.2d 1012, 1020 (11th Cir. 1987). The

coincidence of similar elements first led the Supreme Court to

conclude that such a defendant was denied his sixth amendment

right to assistance of counsel in Massiah v. United States, 377

U.S. 201 (1964). In that case, the defendant's confederate

-26-

cooperated with the government in its investigation and allowed

his automobile to be "bugged." The confederate subsequently had

a conversation in the car with the defendant during which the

defendant made incriminating statements. The confederate then

testified about the defendant's statements at the defendant's

trial. The Supreme Court held that the defendant had been

"denied the basic protections of [the sixth amendment] when it

was used against him at his trial evidence of his own incrim

inating words, which federal agents had deliberately elicited

from him after he had been indicted and in the absence of his

counsel." id. at 206.6

The Supreme Court applied its ruling in Massiah to the

jailhouse informant situation in United States v. Henry, 447 U.S.

264 (1980). In that case, a paid informant for the FBI happened

to be an inmate in the same jail in which defendant Henry was

being held pending trial. An investigator instructed the

informant inmate to pay particular attention to statements made

by the defendant, but admonished the inmate not to solicit

information from the defendant regarding the defendant's in

dictment for bank robbery. The inmate engaged the defendant in

conversations regarding the bank robbery and subsequently

testified at trial against the defendant based upon these

conversations. The Supreme Court held that the inmate had

deliberately elicited incriminating statements by engaging the

defendant in conversation about the bank robbery. Id. at 271. It

-27-

was held irrelevant under Mass iah whether the informant ques

tioned the defendant about the crime or merely engaged in general

conversation which led to the disclosure of incriminating

statements about the crime. Id. at 271-72 n. 10. Although the

government insisted that it should not be held responsible for

the inmate's interrogation of the defendant in light of its

specific instructions to the contrary, the Court held that

employing a paid informant who converses with an unsuspecting

inmate while both are in custody amounts to "intentionally

creating a situation likely to induce [the defendant] to make

incriminating statements without the assistance of counsel." Id.

at 274.7

Given the facts established earlier, petitioner has clearly

established a Mass iah violation here. It is clear from Evans'

written statement that he did much more than merely engage

petitioner in conversation about petitioner's crimes. As

discussed earlier, Evans repeatedly lied to petitioner in order

to gain his trust and to draw him into incriminating statements.

Worthy's testimony establishes that Evans, in eliciting the

incriminating statements, was acting as an agent of the state.

This case is completely unlike Kuhlmann v. Wilson, 106 S.Ct. 2616

(1986), where the Court found no Massiah violation because the

inmate informant had been a passive listener and had not de

liberately elicited incriminating statements from the defendant.

AO 72A ©

( R * v . 8/82)

-28-

• *

Here, Evans was even more active in eliciting incriminating

statements than was the informant in Henry. The conclusion is

inescapable that petitioner's sixth amendment rights, as inter

preted in Massiah, were violated.

However, "[n]ot every interrogation in violation of the rule

set forth in Mas s i ah ... mandate-s reversal of. a conviction."

United States v. Kilrain, 566 F.2d 979, 982 (5th Cir. 1978).

Instead, "the proper rule [is] one of exclusion of tainted

evidence rather than a per se standard of reversal if any

constitutional violation ha[s] occurred." _Id. n. 3, citing

Brewer v. Williams, 430 U.S. 387, 407 n. 12 (1977); United States

v. Hayles, 471 F.2d 788, 793, cert, denied, 411 U.s. 969 (5th

Cir. 1973). In other words, "certain violations of the right to

counsel may be disregarded as harmless error." United States v.

Morrison, 449 U.S. 361, 365 (1981), citing Chapman v. California,

386 U.S. 18, 23 n. 8 (1967). To avoid reversal of petitioner's

conviction the state must "prove beyond a reasonable doubt that

the error complained of [the use at petitioner's trial of his own

incriminating statements obtained in violation of his sixth

amendment rights] did not contribute to the verdict obtained."

Chapman, 386 U.S. at 24. See also Brown v. Dugger, No. 85-6082,

Slip Op. at 511-12 (11th Cir. November 13, 1987).

Once the fact of the Massiah violation in this case is

accepted, it is not possible to find that the error was harmless.

A review of the evidence presented at the petitioner's trial

AO 72A ©

(R«v. 8/82)

-29-

reveals that Evans' testimony about the petitioner's incrim

inating statements was critical to the state's case. There were

no witnesses to the shooting and the murder weapon was never

found. The bulk of the state's case against the petitioner was

three pronged: (1) evidence that petitioner carried a particular

gun on the day of the robbery that most likely fired the fatal

bullets; (2) testimony by co-defendant Ben Wright that petitioner

pulled the trigger; and (3) Evans' testimony about petitioner's

incriminating statements. As petitioner points out, the evidence

on petitioner's possession of the gun in question was conflicting

and the testimony of Ben Wright was obviously impeachable.® The

state also emphasizes that Evans testified only in rebuttal and

for the sole purpose of impeaching McCleskey's alibi defense. But

the chronological placement of Evans' testimony does not dilute

its impact -- "merely" impeaching the statement "I didn't do it"

with the testimony "He told me he did do it" is the functional

equivalent of case in chief evidence of guilt.

For the foregoing reasons, the court concludes that peti

tioner's sixth amendment rights, as interpreted in Ma ssiah, were

violated by the use at trial of Evans' testimony about the

petitioner's incriminating statements because those statements

were deliberately elicited by an agent of the state after

petitioner's indictment and in the absence of petitioner's

attorney. Because the court cannot say, beyond a reasonable

doubt, that the jury would have convicted petitioner without

-30-

Evans' testimony about petitioner's incriminating statements,

petitioner's conviction for the murder of Officer Schlatt must be

reversed pending a new trial.®

Unfortunately, one or more of those investigating Officer

Schlatt's murder stepped out of line. Determined to avenge his

death, the investigator(s) violated clearly-established case

law, however artificial or ill-conceived it might have appeared.

In so doing, the investigator(s) ignored the rule of law that

Officer Schlatt gave his life in protecting and thereby tainted

the prosecution of his killer.

B . Mooney Claim.

Petitioner's Mooney claim is based upon the state's use at

trial of misleading testimony by Offie Evans, which petitioner

contends violated his eighth amendment rights and his right to

due process of law under the fourteenth- amendment. See Mooney v.

Holohan, 294 U.S. 103, 112 (1935) (criminal conviction may not be

obtained using testimony known to be perjured) . In particular,

petitioner contends that the state failed to correct Evans'

misleading testimony regarding his rial interest in testifying

against petitioner, regarding the circumstances surrounding his

cooperation with the state, and regarding petitioner's confession

of having shot Officer Schlatt. Petitioner alleges that the

newly discovered statement of Offie Evans reveals these mis

leading elements of Offie Evans' testimony at trial.

AO 72A ®

(Raw. 8/82)

-31- /

Petitioner's allegation that the state misled the jury with

Offie Evans' testimony that he was a disinterested witness is

actually a restatement of petitioner's Gig 1io claim. The

allegation that the state misled the jury with Offie Evans'

testimony that he happened to inform the state of petitioner's

incriminating statements, when in fact the evidence suggests that

Offie Evans may have been an agent of the state, is a restatement

of petitioner's Mass iah claim. Consequently, only the allega

tions of misleading testimony regarding the actual shooting need

to be addressed as allegations supportive of a separate Mooney

claim.

As a preliminary matter, the failure of petitioner to raise

this claim in his first federal habeas petition raises the

question of abuse of the writ. Because this claim is based upon

the newly discovered statement of Offie Evans, the same con

clusion reached as to the Massiah claim obtains for this claim.

It was not an abuse of the writ to fail to raise the Massiah

claim earlier and it was not an abuse of the writ to have failed

to raise this claim eirlier.

However, on its merits the claim itself is unavailing. In

order to prevail on :nis claim, petitioner must establish that

the state did indeed use false or misleading evidence and that

the evidence was "material" in obtaining petitioner's conviction

or sentence or both. Brown v. Wainwright, 785 F.2d 1457, 1465

(11th Cir. 1986). The test for materiality is whether there is

"any reasonable likelihood that the false testimony could have

-32-

affected the judgment of the jury." I_d. at 1465-66 (quoting

United States v. Bagley, ___ U.S. ___, 105 S.Ct. 3375, 3382

(1985) (plurality)). Petitioner's allegations of misleading

testimony regarding his confession fail for two reasons.

'First, no false or misleading testimony was admitted at

trial. A comparison of Offie Evans' recently discovered state

ment and his testimony at trial reveals substantially identical

testimony regarding McCleskey's confession that he saw the

policeman with a gun and knew there was a choice between getting

shot by the policeman or shooting the policeman. Compare Pet.

Exhibit E, at 6 with Trial Tr. at 870. While Offie Evans did use

the word "panic" in his written statement when describing this

dilemma, the addition of this word adds nothing to the substance

of the trial testimony, which conveyed to the jury the exigencies

of the moment when petitioner fired upon Officer Schlatt. Second,

even if the omission of this one phrase did render the testimony

of Offie Evans misleading, this claim would fail because there is

no reasonable likelihood that the jury's judgment regarding peti

tioner's guilt and his sentencing would have been altered by the

addition of the phrase "panic" to otherwise substantially

identical testimony.

C. Caldwell Claim.

Petitioner's third new claim is based upon references by the

prosecutor at petitioner's trial to appellate review of the jury

sentencing decision and to the reduction on appeal of prior life

-33-

sentences imposed on petitioner. These references are said to

have violated petitioner's eighth amendment rights and right to

due process of law as guaranteed by the fourteenth amendment.

To the extent petitioner claims that the reference to the

reduction of prior life sentences was constitutionally impermis

sible in that it led the jury to impose the death penalty for

improper or irrelevant reasons, see Tucker v, Francis, 723 F.2d

1504 (11th Cir. 1984), this claim comes too late in the day.

Petitioner was aware of these comments at the time he filed his

first federal habeas petition but did not articulate this claim

at that time. Because the state has pled abuse of the writ,

petitioner must establish that the failure to raise this claim

during the first federal habeas proceeding was not due to

intentional abandonment or inexcusable neglect. Petitioner has

offered no excuse for not raising this claim before. He was

represented by competent counsel at the time and should not be

heard to argue that he was unaware that these facts would support

the claim for habeas relief. Indeed, this court recognized the

potential for such a claim when passing upon the first federal'

habeas petition and concluded "it has not been raised'by fully

competent counsel." McCleskey v. Kemp, 580 F. Supp. at 388 n.

27.

Successive petition and abuse of the writ problems also

plague this claim to the extent that petitioner is arguing that

the prosecutor's reference to the appellate process somehow

diminished the jury'.s sense of responsibility during the sen

-34-

tencing phase. This claim in due process terms was presented to

this court by the first federal habeas petition and rejected.

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp. at 387-88 (citing inter alia Corn

v . Zant, 708 F .2d 549, 557 (11th Cir. 1983 )). Petitioner has

offered no reason that the ends of justice would be served by

re-visiting this due process claim.

Petitioner also argues that reference to the appellate

process violated his eighth amendment'rights . Although peti

tioner did not articulate this eighth amendment claim at the time

of the first federal habeas proceeding, the failure to raise the

claim at that time does not amount to an abuse of the writ. Only

after this court ruled upon the first federal habeas petition did

the Supreme Court indicate that it is a violation of the eighth

amendment "to rest a death sentence on a determination made by a

sentencer who has been led to believe that the responsibility for

determining the appropriateness of the defendant's death rests

elsewhere." Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. 320, 328-29

( 1985). This circuit has recently held that failure to raise a

Caldwel1 claim in a first federal habeas petition filed before

the decision does not amount to abuse of the writ because there

has been a change in the substantive law. Adams v. Dugger, 816

F.2d 1493, 1495-96 (11th Cir. 1987) (per curiam).

Although this court must reach the merits of the Caldwell

claim, the claim itself fails for the same reasons that the due

process prong of this claim failed. The essential question is

whether the comments likely caused the jury to attach diminished

-35-

consequences to their deliberations on the death penalty. See

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp. at 388. A review of the prose

cutor's actual comments at petitioner's trial does not reveal any

impermissible suggestions regarding the appellate process which

woulid have led the jury to believe that the responsibility for

imposing the death penalty rested elsewhere. As this court

observed when passing upon the due process claim raised by the

first petition,

The prosecutor's arguments in this case did

not intimate to the jury that a death

sentence could be reviewed or set aside on

appeal. Rather, the prosecutor's argument

referred to petitioner's prior criminal

record and the sentences he had received. The

court cannot find that such arguments had the

effect of diminishing the jury's sense of

responsibility for its deliberations on

petitioner's sentence. Insofar as petitioner

claims that the prosecutor's arguments were

impermissible because they had such an effect, the claim is without merit.

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp. at 388.

D. Batson Claim.

Petitioner's final claim rests upon the alleged systematic

exclusion of black jurors by the prosecutor a: petitioner's

trial. This exclusion is said to have violated petitioner's

right to a representative jury as guaranteed b/ the sixth and

fourteenth amendments.

This claim was not raised during the first federal habeas

proceedings. However, failure to raise this claim could not be

said to constitute abuse of the writ because prior to the Supreme

-36-

Court's decision in Batson v. Kentucky, ___ U.S. ___, 107 S.Ct.

708 (1987), petitioner could not have made out a prima "facie

claim absent proof of a pattern of using preemptory strikes to

exclude black jurors in trials other than petitioner's. See id.

at 710-11 (citing Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965)).

Although petitioner did not abuse the writ by failing to

raise this claim earlier, the claim itself lacks merit. The

holding in Batson, which allows defendants to make the prima

facie showing of an unrepresentative jury by proving a systematic

exclusion of blacks from their own jury, has not been given

retroactive application. The Batson decision does not apply

retroactively to collateral attacks "where the judgment of

conviction was rendered, the availability of appeal exhausted,

and the time for petition for certiorari had elapsed" before the

Batson decision. Allen v. Hardy, ___ U.S. ___, 106 S.Ct. 2878,

2880 n. 1 (1986 ) (per curiam). Although the Allen decision did

not involve a habeas petitioner subject to the death penalty,

this circuit has specifically held that Batson may not be applied

retroactively even to a habeas >etitioner subject to the death

penalty. See Lindsey v. Smith, 820 F.2d 1137, 1145 (11th Cir.

1987); High v. Kemp, 819 F.2d 988, 992 (11th Cir. 1987).

VI. OTHER MOTIONS.

Also pending before this court are petitioner's motions for

discovery and for leave to exceed this court's page limits. The

court presumes that the above resolution of the petitioner's

various claims and the evidentiary hearing held in this case

AO 72A ®

(R*v. 8/82)

-37-

obviate the need for any further discovery. Petitioner's motion

for discovery, filed before the evidentiary hearing, does not

provide any reason to think otherwise. The motion for discovery

is therefore DENIED. The motion to exceed page limits is

GRANTED.

VII. CONCLUSION.

In summary, the petition for a writ of habeas corpus is

DENIED as to petitioner's Giglio, intentional discrimination, and

Ake claims because those claims are successive and do not fall

within the ends of justice exception. The petition for a writ of

habeas corpus is DENIED as to petitioner's Mooney, Caldwell and

Batson claims because they are without merit. Petitioner's

motion for discovery is DENIED and his motion to exceed page

limits is GRANTED. The petition for a writ of habeas corpus is

GRANTED as to petitioner's Massiah claim unless the state shall

re-try him within 120

SO ORDERED, this

days og the receipt of this order.

^~~ day of , 1987.

J. /OWEN FORRESTER

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

-38-AO 72A ©

(R*v. 8/82)

FOOTNOTES

1 . Petitioner was also convicted on two counts of armed robbery and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

̂ Another distinct ground for finding excusable neglect is a showing that the petitioner did not realize that the facts of

which he had knowledge could constitute a basis for which federal

habeas corpus relief could be granted. Booker v. Wainwright, 764

F.2d 1371, 1376 (11th Cir. 1985). Although "[t]he exact scope of

this alternative exception to the abuse of writ doctrine lacks

adequate definition," id., it would appear from the cases that applies only when the petitioner appeared pro se the first habeas petition.

1273, 1276 (5th Cir. 1980). See, e.g,, Haley v,

cases that it

in presenting Estelle, 632 F.2d

"... [W]e hold that the Baldus study does not demonstrate a constitutionally significant risk of racial bias affecting the

Georgia capital-sentencing process." (Powell, J., for the majority). McCleskey v. Kemp, U.S. , 107 S.Ct. 1759 at1778 (1987). ---

4 See the discussion of McCleskey's Massiah claim infra.

References to the transcripts of the July 8, July 9, and August 10, 1987 hearings will be to "I TR.," "II Tr.," and "III Tr.," respectively.

Dissenting Justice White, joined by Clark and Harland, JJ., protested the new "constitutional rule ... barring the use of

evidence which is relevant, reliable and highly probative of the

i-sue which the trial court has before it." 377 U.S. at 208. The

d.ssenters were "unable to see how this case presents an un

constitutional interference with Massiah's right to counsel.

Messiah was not prevented from consulting with counsel as often

as he wished. No meetings with counsel were disturbed or spied

upon. Preparation for trial was in no way obstructed. It is

only a sterile syllogism -- an unsound one, besides -- to say

that because Massiah had a right to counsel's aid before and

during the trial, his out-of-court conversations and admissions

must be excluded if obtained without counsel's consent or presence." Id. at 209.

The dissenters highlighted the incongruity of overturning

Massiah's conviction on these facts. "Had there been no prior

arrangements between [the confederate] and the police, had [the

confederate] simply gone to the police after the conversation had

occurred, his testimony relating Massiah's statements would be

readily admissible at the trial, as would a recording which he

might have made of the conversation. In such event, it would

simply be said that Massiah risked talking to a friend who

decided to disclose what he knew of Massiah's criminal activi

ties. But if, as occurred here, [the confederate] had been

cooperating with the police prior to his meeting with Massiah,

both his evidence and the recorded conversation are somehow

transformed into inadmissible evidence despite the fact that the

hazard to Massiah remains precisely the same — the defection of a confederate in crime." Id. at 211.

Justice Rehnquist, dissenting, questioned the validity of Massiah: "The exclusion of respondent's statements has no

relationship whatsoever to the reliability of the evidence, and it rests on a prophylactic application of the Sixth Amendment

right to counsel that in my view entirely ignores the doctrinal

foundation of that right." 447 U.S. at 289. Echoing many of the

concerns expressed by Justice White in Mass iah, id. at 290 ,

Justice Rehnquist argued that "there is no constitutional or

historical support for concluding that an accused has a right to

have his attorney serve as a sort of guru who must be present

whenever an accused has an inclination to reveal incriminating

information to anyone who acts to elicit such information at the

behest of the prosecution." Id. at 295-96. Admitting that the

informants in Henry and in Mass iah were encouraged to elicit

information from the respective defendants, Justice Rehnquist

"doubt[ed] that most people would find this type of elicitation reprehensible." Id. at 297.

For criticism of Henry for extending Massiah "despite that

decision's doctrinal emptiness" and for giving Massiah "a firmer

place in the law than it deserves," see Salzburg, Forward; The

Flow and Ebb of Constitutional Criminal Procedure in the Warren

and Burger Courts, 69 Geo.L.J. 151, 206-08 (1980).

There is some question whether Ben Wright's testimony on the

fact of the murder would have been admissible at all absent

corroboration by Evans' testimony. See O.C.G.A. §24-4-8 (uncorroborated testimony of an accomplice not sufficient to

establish a fact). But see McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F.2d at 885

(Wright's testimony corroborated by McCleskey's admitted par

ticipation in the robbery; corroboration need not extend to every material detail).

li

V

Massiah andy Here, as in _______the conviction consequently

evidence is "relevant, reliable

tioner's guilt.

There

Henry, the evidence is excluded and reversed despite the fact that the

and highly probative" of peti-

Massiah, 377 U.S. at 208 (White, J., dis

senting). There is no question that petitioner's incriminating

statements to Evans were made voluntarily and without coercion.

Had Evans been merely a good listener who first obtained

McCleskey's confession and then approached the authorities,

Evans' testimony would have been admissible. The substance of

the evidence would have been no different, McCleskey's risk in

speaking would have been no different, and McCleskey's counsel

would have been no less absent, but the evidence would have been

admissible simply because the state did not intentionally seek to

obtain it. While this court has grave doubts about the his

torical and rational validity of the Supreme Court's present

interpretation of the sixth amendment, those doubts have been

articulated ably in the dissents of Justice White and Justice

Rehnquist. See supra, notes 4 and 5. Until the Supreme Court

repudiates its present doctrine this court will be obliged to reach the result it reaches today.

i

iii

AO 72A ©

(Rev. 8/82) /

13

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, as well as those presented

by the petitioner, the decision of the court below should be

reversed.

Re spec-tfully subni itl ed,

M ilton A. Smith

General Counsel

Otto F. W enzler

Labor Relations Counsel

Chamber of Commerce of the United

States of America

1615 II Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

Lawrence M. Cohen

S. Richard Pincus

Lederer, Fox and Grove

111 West Washington Street

Chicago, Illinois 60602

Gerard C. Smetana

925 South Homan A venue

Chicago, Illinois 60607

Attorneys for The Chamber of Com

merce of the United States of

America