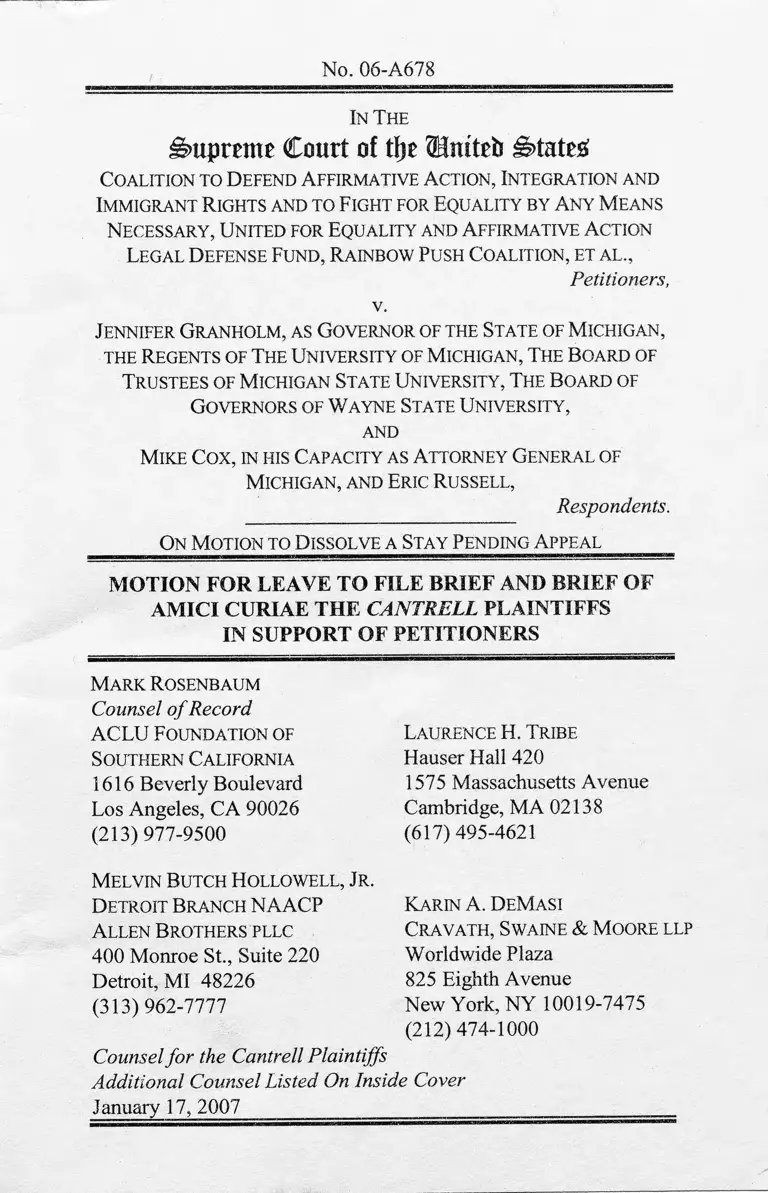

Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v. Granholm Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 17, 2007

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v. Granholm Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 2007. 1d5f34db-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ef064231-d4c6-4e58-afa3-48c69bd63673/coalition-to-defend-affirmative-action-v-granholm-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 06-A678

In T he

Supreme Court of tlje &lm'trb States;

C o alition to D efend A ffirm a tive A c tio n , In teg ra tion and

Im m igra nt R ights and t o F ight for E q uality by A n y M eans

N ecessa ry , United fo r Eq ua lity and A ffirm a tive Action

Lega l D efen se Fu n d , R a in b o w Push Co a litio n , et a l .,

Jennifer G r a n h o lm , as G o v ern o r of the State of M ic h ig a n ,

the R egents o f T he U n iv er sity o f M ich iga n , T he B o ard of

T rustees o f M ichigan State Un iv er sity , T he B oard of

G o verno rs o f W a yne State U n iv er sity ,

and

M ike C o x , in his Ca pa city as A tto rney G eneral of

M ich iga n , a nd Eric R u ssell ,

Respondents.

On M otion to D issolve a Stay P ending A ppeal

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AND BRIEF OF

AMICI CURIAE THE CANTRELL PLAINTIFFS

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

M a rk R osen bau m

Counsel o f Record

ACLU F o u n da tion of

So uthern Ca lifornia

1616 Beverly Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90026

(213) 977-9500

M elvin Butch H o llo w ell , J r .

D etro it B ran ch NAACP

A llen B roth ers pllc

400 Monroe St., Suite 220

Detroit, MI 48226

(313)962-7777

Counsel for the Cantrell Plaintiffs

Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover

January 17, 2007 _____ ____________

Laurence H. Tribe

Hauser Hall 420

1575 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

(617) 495-4621

Ka rin A. D eM asi

C ra v a th , Sw aine & M oore llp

Worldwide Plaza

825 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10019-7475

(212) 474-1000

T h eodore M . Shaw

V ictor B o lden

A n u r im a B h a r g a v a

NAACP Le g a l D efen se &

E d u c a tio n a l Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Erw in C h em erin sk y

D uke Un iv er sity School of

Law

Science Drive & Towerview Rd.

Durham, NC 27708

(919)613-7173

D ennis P a rk er

A lexis A gatho cleo us

A m erican C iv il L iberties

U n io n F o u n d a tio n R a cial

Justice P rog ram

125 Broad St., 18th Floor

New York, NY 10004-2400

(212)519-7832

Ka ry L. M oss

M ichael J. Steinberg

M a rk P. Fa ncher

A m erican C ivil L iberties

Un ion Fund of M ich iga n

60 W. Hancock Street

Detroit, MI 48201

(313)578-6814

Jerom e R. W atson

M iller , Ca n field , Pa d d o c k and

Sto n e , p .l .c .

150 West Jefferson, Suite 2500

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 963-6420

D aniel P. Tokaji

The Oh io State U n iv er sity

M o ritz Co llege O f La w

55 W. 12th Ave.

Columbus, OH 43206

(614) 292-6566

Counsel for the Cantrell Plaintiffs

No. 06-A678

In T he

Supreme Court of tfjc ©nttriJ i§>tatE£

C o alitio n to D efend A ffirm a tive A c tio n , In teg ra tio n

a nd Im m igra nt R ights and to F ight for Eq ua lity by

A n y M eans Ne cessa ry , Un ited for Eq ua lity and

A ffirm a tive A ction Lega l D efen se F u n d , R a inbo w

Push C o a litio n , et a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

Jenn ifer G ra n h o lm , as G o v ern o r of the State of

M ic h ig a n , the R egents of Th e Un iversity of M ich ig a n ,

Th e B oard of T rustees of M ichigan State Un iv er sity ,

T he B oard o f G overnors of W a yne State U n iv er sity ,

and

M ike Cox, in his Capacity as A tto rney G enera l of

M ich iga n , and Eric R u ssell ,

Respondents.

On M otion to D issolve a Stay Pending A ppeal_____

MOTION OF AMICI CURIAE THE CANTRELL

PLAINTIFFS FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Plaintiffs in Cantrell, et al. v. Granholm, No. 2:06-cv-

15637 (E.D. Mich.), who represent a proposed class of all

present and future students and faculty at the University of

Michigan who applied to, matriculated at, or continue to be

enrolled at or employed by the University of Michigan in

reliance upon the University’s representation that it would

continue to admit and enroll a diverse group of students

consistent with the University’s former admissions policy,

respectfully move this Court pursuant to Supreme Court Rule

37.2 for leave to file the accompanying brief in support of

Petitioners in Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action,

2

Integration and Immigrant Rights and To Fight For Equality

By Any Means Necessary, et al. v. Granholm, etal..

On January 5, 2007, the District Court for the Eastern

District of Michigan consolidated Petitioners’ case with the

Cantrell litigation. See January 5, 2007 Order. Indeed,

these cases raise common questions of law and fact, and the

interests of the plaintiffs in both litigations are equally at

stake with respect to the stay order entered by the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit that Petitioners

have asked this Court to vacate.

Amici, the Cantrell Plaintiffs, respectfully seek to

submit their brief to further explain the extent to which the

Sixth Circuit panel failed to recognize and uphold this

Court’s political restructuring jurisprudence as set forth in

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) and Washington v.

Seattle School District No. 1, 458 U.S. 457 (1982). The

panel’s flawed discussion of Hunter and Seattle should not

be permitted to stand, even as dicta. Moreover, the Cantrell

Plaintiffs support Petitioners’ request that this Court vacate

the Sixth Circuit’s opinion, which, if left to stand, would

seriously and irreparably harm the rights of high school

students around the country whose applications to the

University of Michigan are being evaluated according to two

different sets of criteria as a result of the Sixth Circuit’s

decision. Amici, the Cantrell Plaintiffs, believe that they will

present arguments to this Court that will not be, and have not

been, presented in the same form by the parties.

3

For the foregoing reasons, amici, the Cantrell Plaintiffs,

respectfully request that this Court grant their motion for

leave to file the accompanying brief in support of Petitioners.

January 17,2007

Respectfully submitted,

Is/ Mark Rosenbaum ______.

M a rk R osenbaum

Counsel o f Record

La urence H.T ribe

Hauser Hall 420

1575 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

(617) 495-4621

M elvin B u tch H o llo w ell , J r .

G eneral C o u n sel ,

D etro it B ran ch NAACP

A llen B roth ers pllc

400 Monroe St., Suite 220

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-7777

Ka rin A. D eM asi

C ra v a th , Sw aine & M oore llp

Worldwide Plaza

825 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10019-7475

(212) 474-1000

4

T h eodore M. Shaw

V ictor B olden

A n urim a B hargava

NAACP Leg a l D efense &

E d u c atio na l F und

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

K ary L. M oss

M ich ael J. Steinberg

M a r k P. F a ncher

A m erican C ivil L iberties U n ion

Fu nd of M ichigan

60 W. Hancock Street

Detroit, MI 48201

(313)578-6814

Erw in C hem erin sky

D u k e Un iv er sity School o f Law

Science Drive & Towerview Rd.

Durham, NC 27708

(919)613-7173

Jero m e R. W atson

M iller , Ca n field , P a dd ock and

St o n e , p .l .c .

150 West Jefferson, Suite 2500

Detroit, MI 48226

(313)963-6420

5

D ennis Parker

A lexis A gathocleous

A m erican C ivil L iberties U n ion

Foundation Ra cial Justice

P rogram

125 Broad St., 18th Floor

New York, NY 10004-2400

(212)519-7832

D aniel P. Tokaji

T he O hio State Un iversity

M oritz College O f Law

55 W. 12th Ave.

Columbus, OH 43206

(614) 292-6566

Counsel for the Cantrell Plaintiffs

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................................ iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE..........................................1

JURISDICTION....................................................................2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT..............................................2

ARGUMENT........................................................................ 4

I. STANDARD FOR GRANTING RELIEF.....................4

II. THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT PETITIONERS ’

MOTION TO DISSOLVE THE STAY ENTERED

BY THE SIXTH CIRCUIT............................... 5

A. Petitioners’ Rights May Be Seriously And

Irreparably Injured By The Sixth Circuit’s

Stay And This Court Could And Likely

Would Review The Underlying Case Upon Its

Final Disposition............. 5

B. The Sixth Circuit Is Demonstrably Wrong In

Its Application Of Accepted Standards In

Deciding To Issue The Stay...................................7

1. This Court Held In Hunter and Seattle

That A State May Not Selectively

Burden The Process Of Securing

Legislation Predominantly Advancing

The Interests Of Racial Minorities................ 7

2. Hunter and Seattle Remain Good Law

And Have Controlling Force In The

Underlying Case.......................................... 11

11

Page

3. The Sixth Circuit Fundamentally

Misconstrued and Misapplied This

Court’s Political Restructuring Doctrine

As Set Forth in Hunter and Seattle.............12

CONCLUSION 16

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

Cases

Adarand Const., Inc. v. Pena,

515 U.S. 200(1995).......................................................11

Certain Named and Unnamed Non-Citizen

Children and Their Parents v. Texas,

448 U.S. 1327(1980)........................................... 2

Coleman, Jr. v. Paccar Inc.,

424 U.S. 1301 (1976)................................................... 2,5

Crawford v. Bd. ofEduc.,

458 U.S. 527(1982).................................................13, 15

Grutter v. Bollinger,

539 U.S. 306 (2003)............................................... .passim

Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385 (1969)............................................... .passim

Hunter v. Underwood,

471 U.S. 222(1985).................................................11, 14

Layne & Bowler Corp. v. W. Well Works,

261 U.S. 387(1923)................................ 6

Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.,

488 U.S. 469(1989)........... 11

Washington v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1,

458 U.S. 457 (1982)............................................... .passim

Statutes & Rules

Sup. Ct. R. 10(c).................................................................... 6

IV

Page(s)

28 U.S.C. § 1651 (2000)...................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 2101(f) Supp. Ill 2002.......................................2

Mich. Const. 1963, art. I, § 26........................................ 3, 12

Other Authorities

Amar & Caminker, “Equal Protection, Unequal

Political Burdens, and the CCRI,” 23 Hastings

Const. L.Q., 1019(1996)................................................ 16

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

Amici, the Cantrell Plaintiffs, represent a proposed class

of all present and future students and faculty at the University

of Michigan who applied to, matriculated at, or continue to

be enrolled at or employed by the University of Michigan in

reliance upon the University’s representation that it would

continue to admit and enroll a diverse group of students at

the school consistent with its former admissions policy.

Having already described their interest in this case in their

motion for leave to file a brief in support of Petitioners (pp.

1-3), amici repeat here that the stay order entered below may

have a substantial impact on thousands of students around the

country, including amici, who already have applied to public

universities in Michigan and who will have their applications

assessed according to two different sets of criteria depending

upon the sheer fortuity of when in the cycle their applications

came up for consideration. Moreover, amici seek to have the

Sixth Circuit’s stay dissolved so that the important

constitutional issues at the core of the underlying

consolidated cases might be fully developed and briefed, and

so that the panel opinion not set this litigation on a

fundamentally misdirected track at the very outset of these

lawsuits.

1 Counsel for Petitioners did not author, in whole or in part, this

brief; nor did any person or entity, other than amici and their counsel,

make a monetary contribution to the preparation or submission of this

brief.

2

JURISDICTION

A temporary injunction was entered by the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan on

December 18, 2006.2 On December 29, 2006, the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered an

Opinion and Order staying, pending appeal, the district

court’s temporary injunction.3 Accordingly, the relief sought

by Petitioners is not available from any other court or judge.

The jurisdiction of an individual Justice to vacate a stay

order entered by a lower court pending appeal of an order

entered by a court below is invoked under Sup. Ct. R. 22-23,

28 U.S.C. § 1651 (2000) and 28 U.S.C. § 2101(f) (Supp. Ill

2002). See Coleman, Jr. v. Paccar Inc., 424 U.S. 1301, 1304

(1976) (Rehnquist, Circuit Justice) (finding that “a Circuit

Justice has jurisdiction to vacate a stay” under certain

circumstances); see also Certain Named and Unnamed Non-

Citizen Children and Their Parents v. Texas, 448 U.S. 1327,

1330 (1980) (Powell, Circuit Justice) (“The power of a

Circuit Justice to dissolve a stay is well settled.”) (internal

citation omitted).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case raises the issue of the constitutionality of

Proposal 2, an amendment to the Constitution of the State of

Michigan which (among other things) proponents contend

bars continuation of existing race-conscious policies and

programs designed to achieve diversity in classrooms at

2 A copy of the district court’s Order Granting Temporary

Injunction And Dismissing Cross-Claim In Part is attached as Exhibit B

to Petitioners’ motion.

3 A copy of the Sixth Circuit’s opinion granting Respondents’

motion for a stay of the temporary injunction entered by the district court

(“Opinion”) is attached as Exhibit A to Petitioners’ motion.

3

colleges and universities throughout Michigan, including at

the University of Michigan. This Court affirmed just over

three years ago that the University of Michigan may employ

race-conscious admissions programs that are narrowly

tailored to achieve its compelling interest in student body

diversity. See Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

An emergency motions panel of the Sixth Circuit,

without benefit of full and deliberate briefing or any

evidentiary record, stayed a limited injunction entered by the

district court that enforced a stipulation among the state

entities involved in the litigation,4 including the Governor of

the State of Michigan, the Attorney General, and the

University of Michigan, Michigan State and Wayne State

(“State Universities”), which would have kept in place

existing programs only until July 1, 2007, so as not to disrupt

the ongoing admissions cycle. No party had more than

48 hours to prepare and file papers, and all principal briefing

was ordered to be filed on December 28, 2006.

The emergency panel issued its opinion on

December 29, 2006, staying the injunction and extinguishing

the stipulation. Although stating that “the merits of the

appeal of the order granting the preliminary injunction . . .

[is] not before this panel” (Opinion at 5), the Opinion issued

is breathtaking in its aggressive scope and sweep as to the

4 The stipulation, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit C to

Petitioners’ motion, states in relevant part:

“It is hereby stipulated, by and between the parties that

this Court may order as follows:

(1) that the application of Const[.] 1963, art[.] 1, § 26 to

the current admissions and financial aid policies of the

University parties is enjoined through the end of the current

admissions and financial aid cycles and no later than 12:01

a.m. on July 1, 2007, at which time this Stipulated Injunction

will expire[.]”

4

underlying constitutional issues in the case.5 More

particularly, the panel devoted barely a page of its decision to

this Court’s political restructuring doctrine under the

Fourteenth Amendment as set forth in Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S, 385 (1969) and Washington v. Seattle School

District No. 1, 458 U.S. 457 (1982). In fact, the

Hunter/Seattle claim was never even presented to the district

court as grounds for a stay or approval of the stipulation.

Perhaps as a consequence, the panel, in its few-paragraph

discussion of the issue, got this Court’s jurisprudence

fundamentally wrong. The panel failed to recognize and

uphold the Hunter/Seattle principle that a state may not

selectively burden the process of securing legislation

predominantly advancing the interests of racial minorities.

Accordingly, the stay of the stipulation should be dissolved

to avoid serious and irreparable injury to the rights of the

parties to the underlying action, and so that the important

constitutional issues at the core of this case might be fully

developed and briefed such that the panel opinion not set this

litigation on a fundamentally misdirected track, derailing it

with so weighty a misguided precedent at the very outset of

the lawsuit.

ARGUMENT

I, STANDARD FOR GRANTING RELIEF

Former Chief Justice William Rehnquist, deciding a

motion addressed to him individually to vacate a stay order

5 It seems highly irregular, if not jurisdictionally improper, that the

Sixth Circuit panel asked the parties to brief and then ruled upon the

likelihood of success for all of the claims filed by all parties to the action,

rather than limiting itself to the single claim advanced in support of a stay

in the district court below. Moreover, the purported reason for the stay—

that the district court no longer had jurisdiction over the matter once the

stipulation was entered—is a dubious one because the stipulation did not

extinguish the action.

5

entered by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit in a case then pending before that court, found that “a

Circuit Justice has jurisdiction to vacate a stay where it

appears that the rights of the parties to a case pending in the

court of appeals, which case could and very likely would be

reviewed here upon final disposition in the court of appeals,

may be seriously and irreparably injured by the stay, and the

Circuit Justice is of the opinion that the court of appeals is

demonstrably wrong in its application of accepted standards

in deciding to issue the stay.” See Paccar Inc., 424 U.S. at

1304.

Accordingly, an individual Justice has jurisdiction to

vacate a stay entered by a lower court if the petitioners can

demonstrate that (1) their rights “may be seriously and

irreparably injured by the stay,” provided that the underlying

case to which they are a party “could and very likely would

be reviewed [by this Court] upon final disposition” and (2)

the lower court “is demonstrably wrong in its application of

accepted standards in deciding to issue the stay.” Id.

II. THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT PETITIONERS’

MOTION TO DISSOLVE THE STAY ENTERED

BY THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

A. Petitioners’ Rights May Be Seriously And

Irreparably Injured By The Sixth Circuit’s

Stay And This Court Could And Likely Would

Review The Underlying Case Upon Its Final

Disposition.

Reinstating the district court’s temporary injunction to

preserve the status quo is necessary to avoid serious and

irreparable injury to thousands of students who already have

applied to the State Universities, and perhaps not applied

elsewhere, with the justifiable expectation that current

admissions policies would provide the basis for evaluating

their applications and determining their educational future.

6

As it stands now under Proposal 2—and with the injunction

stayed—high school students around the country are having

their applications assessed according to two different sets o f

criteria depending upon the sheer fortuity of when in the

cycle their applications came up for consideration. That is

plainly unfair.

In addition to the unfairness that will result if the Sixth

Circuit’s stay is not lifted, Petitioners seek relief from this

Court to avoid the irreparable injury that so misguided a

precedent will cause if left in place at this early stage in the

underlying litigation. As Petitioners themselves set forth in

their brief, Proposal 2 poses a serious threat to the interests of

both present and future applicants to colleges and universities

throughout Michigan. These interests will suffer irreparable

harm if this Court blesses the Sixth Circuit’s hasty disposal

of the constitutional issues at stake in these consolidated

cases by declining to lift the stay.

For these reasons, among others, the underlying case in

this matter could and likely would be reviewed by this Court

upon final disposition on the merits. Pursuant to Supreme

Court Rule 10(c), this Court has the discretion to grant a

petition for a writ of certiorari if a lower court “has decided

an important question of federal law that has not been, but

should be, settled by this Court, or has decided an important

federal question in a way that conflicts with relevant

decisions of this Court.” As this Court has made clear, it

seeks to “be consistent in not granting the writ of certiorari

except in cases involving principles the settlement o f which is

o f importance to the public, as distinguished from that of the

parties.” Layne & Bowler Corp. v. W. Well Works, 261 U.S.

387, 393 (1923) (emphasis added).

Of obvious concrete importance to the public is the fact )

that high school students around the country are having their

applications assessed according to two different sets of

criteria as a result of Proposal 2’s enactment. Moreover, at

7

the core of the underlying litigation are principles

inextricably tied to questions that this Court already has

found to be of “national importance.” See Grutter v.

Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 322 (2003) (“Whether diversity is a

compelling interest that can justify the narrowly tailored use

of race in selecting applicants for admission to public

universities” is a “question of national importance.”). If this

Court considered the question of whether it is constitutional

for a public college or graduate school to use race as a factor

in its admissions process “a question of national importance,”

id., certainly the important federal question of whether it is

constitutional for a state to amend its constitution to make

such a consideration impermissible must be of equal national

importance.

B. The Sixth Circuit Is Demonstrably Wrong In

Its Application Of Accepted Standards In

Deciding To Issue The Stay.

1. This Court Held In Hunter and Seattle

That A State May Not Selectively Burden

The Process Of Securing Legislation

Predominantly Advancing The Interests

Of Racial Minorities.

Nearly four decades ago, this Court held that a state law

violates the Equal Protection Clause when it “mak[es] it

more difficult for certain racial. .. minorities [than for other

members of the community] to achieve legislation that is in

their interest.” Hunter, 393 U.S. at 395 (Harlan, J.,

concurring). In Hunter, this Court invalidated a referendum

adopted by a majority of voters of the City of Akron, Ohio

that amended the city charter to require popular approval of

any ordinance regulating real estate transactions “on the basis

of race, color, religion, national origin or ancestry.” Id. at

387. The charter amendment thus not only repealed a fair

housing ordinance previously enacted by the city council,

“but also required the approval of the electors before any

8

future [housing discrimination] ordinance could take effect.”

Id. at 389-90.

This Court, by a vote of 8-1, struck down the Akron

amendment, finding that it “drew a distinction between those

groups who sought the law’s protection against racial,

religious, or ancestral discriminations in the sale and rental of

real estate and those who sought to regulate real property

transactions in the pursuit of other ends.” Id. at 390. This

Court readily discounted the facial neutrality of the charter

amendment, which “dr[ew] no distinctions among racial and

religious groups,” finding that it would nonetheless uniquely

disadvantage those principally benefiting from race

conscious fair housing laws—i.e., minorities—by forcing

them to run a legislative “gantlet” of popular approval that

other laws were spared. Id. at 390-91. As this Court

concluded, “the reality is that the law’s impact falls on the

minority.” See id. at 391.

In Seattle, 458 U.S. at 467-71, this Court reaffirmed its

holding in Hunter, upholding once again the principle that,

while the state may make it more difficult for everyone

across the board to enact or enforce laws on a particular

subject matter, it may not make it selectively more difficult

to secure legislation predominantly advancing the interests of

racial minorities. Specifically, Seattle invalidated Initiative

350, a statewide measure that provided in a facially neutral

fashion (it made no mention whatsoever of race or of racial

minorities) that “‘no school board . . . shall directly or

indirectly require any student to attend a school other than

the school which is geographically nearest or next nearest the

student’s place of residence.”4 458 U.S. at 462. The

initiative, however, contained so many exceptions to this

general prohibition that its sole (and clearly intended)

practical effect was to bar race-conscious busing to respond

to de facto segregation, while permitting busing for any other

reason. See id. at 462-63. After Initiative 350, it became

9

politically and legally pointless for advocates of race

conscious busing ever to approach their local or state school

boards to seek such measures, no matter the relative strength

of their pleas. While this Court expressly recognized that of

course both minority and non-minority citizens might well

favor busing programs, it concluded nonetheless that

Initiative 350 “allocate[d] governmental power nonneutrally,

by explicitly using the racial nature of a decision to

determine the decisionmaking process” in flat violation of the

Hunter principle. See id. at 470. More particularly, “by

specifically exempting from Initiative 350’s proscriptions

most nonracial reasons for assigning students away from

their neighborhood schools, the initiative expressly requires

those championing school integration to surmount a

considerably higher hurdle than persons seeking comparable

legislative action.” Id. at 474; see also id. at 483 (“[Initiative

350] burdens all future attempts to integrate Washington

schools in districts throughout the State, by lodging

decisionmaking authority over the question at a new and

remote level of government.”).

Seattle therefore held that the Equal Protection Clause

prohibits any law that “subtly distorts governmental

processes in such a way as to place special burdens on the

ability of minority groups to achieve beneficial legislation”.

See id. at 467. Precisely like Hunter, Seattle barred a state

from selectively burdening attempts to secure programs that

“inure[ ] primarily to the benefit of the minority.” See id. at

472; see also Hunter, 393 U.S. at 390-91. This constitutional

rule remains the law today, and neither this Court nor any

Justice has ever intimated that it should be otherwise.

Proposal 2 works precisely the same sort of

fundamental change in the rules of political engagement that

this Court condemned in Seattle. Here, just as in Seattle, the

political process prior to the initiative gave discretion to state

agencies (state universities, graduate and professional

10

schools) over the matters (race-conscious affirmative action

admissions programs) reached by the initiative. Here, as in

Seattle, that prior political discretion included the power to

adopt constitutionally permissible measures to promote racial

integration and the benefits of a diverse student body. Here,

as in Seattle, the initiative leaves that discretion in place—

such that state universities and their constituent

undergraduate, graduate and professional schools may

consider and adopt as part of their admissions process

“preferences”6 in favor of any group or criteria (e.g.,

geographical, legacy, athletic)—with the exception of race-

based “preferences” that, like the particular busing measures

barred by the Seattle initiative, inure to the primary benefit of

racial minorities. And here, as in Seattle, the political

restructuring effected made it as difficult as any state

measure could for minorities to achieve legislation on their

behalf, requiring enactment of a new constitutional

amendment as the only possible means of restoring

admissions criteria previously put in place at the university

level.

Thus, as applied here, Proposal 2 imposes, just as

Initiative 350 had in Seattle, a “comparative” burden on

minority interests by its reconstructing of the political

process in “remov[ing] the authority to address a racial

problem—and only a racial problem—from the existing

decisionmaking body.” Id. at 474, 475 n.17. Proposal 2

leaves the political process untouched with respect to the

permissibility' of state university officials to determine

admissions policies by weighing the interests of those

seeking “preferences” other than race, no matter the weight

sought to be accorded all such “preferences,” their manifest

6 By the use of the term “preference” in this brief, the Cantrell

Plaintiffs do not adopt the definition of that term advocated by

proponents of Proposal 2.

11

unfairness, or their lack of any relationship whatsoever to

merit-based outcomes.7

2. Hunter and Seattle Remain Good Law And

Have Controlling Force In The Underlying

Case.

Hunter and Seattle remain good law. If anything, this

Court’s recent decision in Grutter underscores the controlling

force of Seattle as to this case. It was perhaps the most

natural counter-argument prior to Grutter that post-Seattle

developments in this Court’s jurisprudence—notably,

Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989), and

Adarand Construction, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200 (1995}—

raised a concern that “race-preferential” treatment in public

higher education (as well as elsewhere) would be deemed

subject to and then fail strict scrutiny, thereby becoming

racially discriminatory measures barred by federal equal

protection norms. Although the racial restructuring principle

underlying Seattle had never been questioned, the argument

could have been at least colorably made that a measure like

Proposal 2 was defensible as a means of avoiding what

imminently would be viewed as a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

After Grutter, however, no such “neutral” concern

could even plausibly be advanced to support Proposal 2.

This is of course so because, as the state has been

authoritatively informed in Grutter, the very race-based

“preferences” that proponents of Proposal 2 claim are barred

(or at least elevated to a different decision-making unit and

7 As discussed infra, the racial nature of Proposal 2 is no less

simply because “preferential treatment” based on gender is also

purportedly banned. See infra at p. 14; Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S.

222, 231-32 (1985) (observing that measures discriminating along racial

lines are not constitutional simply because they also discriminate along

lines that do not trigger strict scrutiny).

12

process) by this initiative, if properly designed to promote a

diverse student body, are fully consistent with equal

protection norms. See Grutter, 539 U.S. at 343 (“the Equal

Protection Clause does not prohibit the Law School’s

narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to

further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational

benefits that flow from a diverse student body.”). Indeed,

Grutter makes the case against Proposal 2 stronger

constitutionally than the case against the measures

invalidated in either Hunter or Seattle', the racial matters

subject to the political restructuring in those earlier cases

were legitimate interests for individuals to champion but they

were not then (and are not now) held to be compelling state

interests satisfying strict scrutiny analysis.

3. The Sixth Circuit Fundamentally

Misconstrued and Misapplied This Court’s

Political Restructuring Doctrine As Set

Forth in Hunter and Seattle.

In the extreme haste of its decisionmaking, the panel not

only reached the wrong result, but also relied upon a

purported distinction from Hunter immaterial to the holding,

and misapprehended Seattle so radically as to require that

decision to have come out the other way. This is how the

panel sought to distinguish Proposal 2 from this Court’s

political restructuring jurisprudence:

“Unlike the laws invalidated in Hunter [and]

Seattle . . . , Proposal 2 does not burden minority

interests and minority interests alone. The

proposal prohibits the State from discriminating

against or granting preferential treatment to

individuals on the basis of “race, sex, color,

ethnicity, or national origin.” Mich. Const, art. I,

§ 26. No matter how one chooses to characterize

the individuals and classes benefitted or burdened

by this law, the classes burdened by the law

13

according to the plaintiffs—women and

minorities—make up a majority of the Michigan

population. As Hunter indicates, the “majority

needs no protection against discrimination and if it

did, a referendum might be bothersome but no

more than that.” 393 U.S. at 391. Unlike the

Hunter line of cases, then, Proposal 2 does not

single out minority interests for this alleged burden

but extends it to a majority of the people of the

State.

Even were we to consider only the law’s

restrictions on racial preferences, this political-

process claim still would not be likely to succeed.

The challenged enactments in Hunter [and]

Seattle . . . made it more difficult for minorities to

obtain protection from discrimination through the

political process; here, by contrast, Proposal 2

purports to make it more difficult for minorities to

obtain racial preferences through the political

process. These are fundamentally different

concepts. The Hunter [and] Seattle . . . decisions,

moreover, objected to a State’s impermissible

attempt to reallocate political authority. See

Seattle, 458 U.S. at 470 (prohibiting a government

from ‘explicitly using the racial nature of a

decision to determine the decisionmaking

process’). Instead of reallocating the political

structure in the State of Michigan, Proposal 2 is

more akin to the ‘repeal of race-related legislation

or policies that were not required by the Federal

Constitution in the first place f Crawford, 458 U.S.

at 538, an action that does not violate the Equal

Protection Clause.” (Opinion at 11.)

With respect to the first assertion that Proposal 2’s

coupling of minorities and women somehow undoes this

14

Court’s restructuring doctrine, the panel negates the holdings

in Hunter and Seattle in two ways. First, it treats the

interests of minorities and women as if they were one and the

same. Beyond the conspicuous absence of any empirical

basis for this far-fetched (and, we think, unsustainable)

claim, the rights implicated, as in all Fourteenth Amendment

race cases, are personal to members of separate minority

groups. See, e.g., Seattle, 458 U.S. at 474 (“For present

purposes, it is enough that minorities may consider busing

for integration to be ‘legislation that is in their interest.’ . . .

Given the racial focus of Initiative 350, this suffices to

trigger application of the Hunter doctrine.. . . The initiative

removes the authority to address a racial problem . . . in such

a way as to burden minority interests.”) (internal citations

omitted); see also Hunter, 393 U.S. at 391 (“although the law

on its face treats Negro and white, Jew and gentile in an

identical manner, the reality is that the law’s impact falls on

the minority.”). That Proposal 2 is still more draconian in its

reach than either Initiative 350 or the Akron ordinance does

not annul the constitutional violation; if anything it multiplies

the restructuring problem as to members of each

classification who must “surmount a considerably higher

hurdle” politically. See Seattle, 458 U.S. at 474. See also

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222, 232 (1985) (holding

that an additional purpose to discriminate against a group not

subject to strict scrutiny “would not render nugatory the

purpose to discriminate against all blacks.”).

Nor does the restructuring principle established by this

Court depend one whit upon whether “[t]he challenged

enactments . . . ma[ke] it more difficult for minorities to

obtain protection from discrimination” as opposed to “racial

preferences through the political process.” (Opinion at 11)

(emphasis in original). While this distinction may describe

the facts of Hunter, it was irrelevant to the holding. See 391

U.S. at 392-93 (“the State may no more disadvantage any

particular group by making it more difficult to enact

15

legislation in its behalf than it may dilute any person’s vote

or give any group a smaller representation than another of

comparable size.”). And this proposed distinction is defeated

by both the facts and the holding of Seattle. Initiative 350

had nothing to do with “protection from discrimination”; the

busing at issue was not designed to remedy or forestall any

discriminatory treatment through de jure segregation, but

rather concerned voluntary busing to integrate schoolchildren

otherwise separated by de facto housing segregation. As this

Court observed, while the nullified busing program was not

an anti-discrimination program, Hunter governed the case

because it involved legislation “inur[ing] primarily to the

benefit of the minority.” See Seattle, 458 U.S. at 472.8

Indeed, were the touchstone of the restructuring doctrine, as

the panel would have it, a strict requirement that the

contested legislation impact “protection from discrimination”

as opposed to simply benefiting minorities, Initiative 350

would not have qualified for its application.9

Significantly, the dissent by Justice Powell did not identify the

panel’s purported distinction as a basis for its disagreement with the

majority opinion.

9 The panel’s one-sentence treatment of this Court’s decision in

Crawford v. Board o f Education, 458 U.S. 527 (1982), is also exactly

wrong. Crawford upheld Proposition 1, a popularly-enacted amendment

to the California constitution that overrode an unusually broad judicial

interpretation of the state constitution’s equal protection clause permitting

racial busing to redress de facto segregation. See id. at 530-36 & n.12

(noting that “[i]n this respect this case differs from the situation presented

in [Seattle].''). Proposition 1 thus effected a “mere repeal” of the

California Supreme Court’s busing order which stemmed from a finding

that the state constitution not only permitted but required state school

boards “to take reasonable steps to alleviate segregation in the public

schools.” See id. at 530 (internal citations omitted). Unlike Proposal 2,

the “mere repeal” in Crawford did not fundamentally alter the political

process for racial minorities.

16

It also appears that the panel did not grasp the nature or

extent of the restructuring of the political process that

Proposal 2 imposes if the affected institutions, and the people

of Michigan, are to maintain the admissions policies upheld

in Grutter. The panel’s assertion that “reallocating the

political structure in the State of Michigan” is not what

Proposal 2 requires if those policies are to be restored

suggests, at a minimum, that the panel neither saw nor

appreciated that what was previously the domain of

universities’ administrations and admissions committees is

achievable in the wake of Proposal 2 only by constitutional

amendment at a statewide level. See Amar & Caminker,

“Equal Protection, Unequal Political Burdens, and the

CCRI,” 23 Hastings Const. L.Q., 1019, 1049-53 (1996).

CONCLUSION

The state entities in this case stipulated to a preservation

of the status quo in order that the State Universities and

thousands of students could complete the current admissions

cycle in reliance upon the entirely justifiable expectations

with which they went forward. With barely a wink at these

interests, an emergency motions panel extinguished them on

the basis of a wholesale reconfiguration of this Court’s

political restructuring doctrine in the area of race, so

mistaken as to make that jurisprudence unsupportable on its

own terms. It effected this alteration, moreover, without any

evidentiary record, and without the benefit of consideration

by the district court and upon but two days for briefing by the

parties.

This case may well find its way to this Court. If and

when it does, it should be upon a properly developed and

briefed record. Until then, a premature and badly flawed

construction of this Court’s rulings in Hunter and Seattle

should not be permitted to quell the reasonable expectations

of applicants to the University of Michigan and require

respected universities to invent a brand new admissions

17

process overnight so as to create two sets of criteria by which

applicants will be admitted or denied, based on nothing more

than the dates on which they submitted their applications.

January 17, 2007

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ Mark Rosenbaum__________

M a rk R osenbaum

Counsel o f Record

La urence H. Tribe

Hauser Hall 420

1575 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

(617) 495-4621

M elvin Butch H o llo w ell , Jr .

G eneral C o u n sel , D etroit

B ranch NAACP

A llen B rothers pllc

400 Monroe St., Suite 220

Detroit, MI 48226

(313)962-7777

Ka r in A. D eM asi

C ra v a th , Sw a in e & M oore llp

Worldwide Plaza

825 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10019-7475

(212) 474-1000

18

T heodore M. Sh aw

V ictor B olden

A n urim a B harga va

NAACP Legal D efen se &

Ed u c atio na l Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Ka r y L. M oss

M ich ael J. Steinberg

M a r k P. Fa ncher

A m erican C ivil L iberties U n ion

Fu nd of M ichigan

60 W. Hancock Street

Detroit, MI 48201

(313) 578-6814

Erw in Ch em erin sky

D u ke U n iv ersity Sc ho ol o f La w

Science Drive & Towerview Rd.

Durham, NC 27708

(919)613-7173

Jerom e R. W atson

M iller , C a n field , P a d d o c k a nd

Sto n e , p .l .c .

150 West Jefferson, Suite 2500

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 963-6420

19

D ennis Parker

A lexis A gathocleous

A m erican C ivil L iberties U nion

Foun da tion Racial Justice

P rogram

125 Broad St., 18th Floor

New York, NY 10004-2400

(212)519-7832

D a n iel P. T okaji

T he O hio State University

M o ritz College O f Law

55 W. 12th Ave.

Columbus, OH 43206

(614) 292-6566

Counsel for the Cantrell Plaintiffs

\