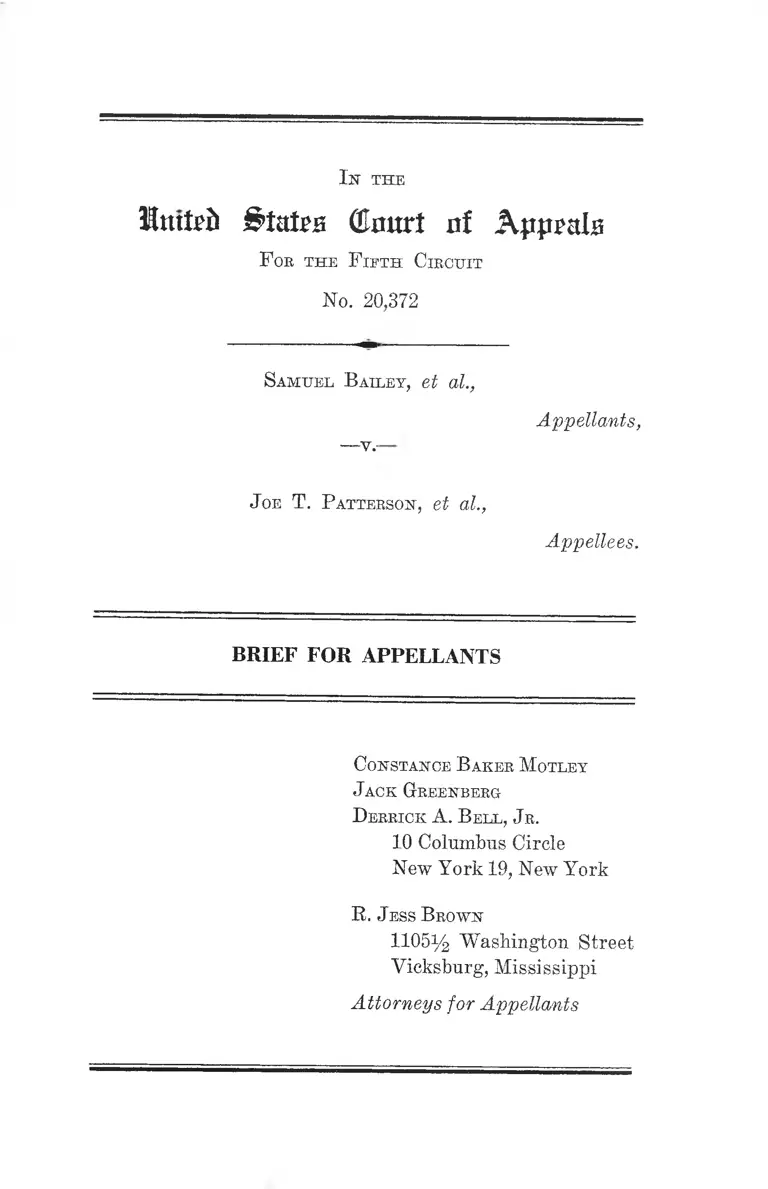

Bailey v. Patterson Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 24, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bailey v. Patterson Brief for Appellants, 1962. f73dd391-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/efcca0b6-8761-4845-ab52-095821b9c398/bailey-v-patterson-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Hutted ^tateu ( ta r t nf Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 20,372

Samuel Bailey, et al.,

—v.-

Appellants,

J oe T. P atterson, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

B. J ess Brown

1105% Washington Street

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .............................................. 1

A. Procedural Summary......................................... 1

B. The Evidence Prior to Ruling by Supreme

Court .................................................................. 4

1. State of Mississippi .......... ......................... 5

2. City of Jackson ........................................... 6

3. Jackson Municipal Airport Authority ...... 7

4. Continental Southern Lines, Inc. (Trail-

ways) ............................................................. 7

5. Southern Greyhound Lines ......................... 9

6. Illinois Central Railroad, Inc....................... 10

7. Jackson City Lines, Inc............................... 10

C. The Supreme Court Decision............................ 11

D. District Court Findings, Conclusion and Judg

ment of May 3, 1962 ........................................... 11

E. The Evidence After District Court’s Ruling of

May 3, 1962 ......................................................... 12

F. District Court Supplemental Findings, Conclu

sions and Judgment of July 25, 1962 .............. 15

G. The Evidence Following District Court’s Rul

ing of July 25, 1962 ........................................... 16

H. District Court’s Amendments to Supplemental

Findings, Conclusions and Judgment of August

24, 1962 .............................................................. 16

Specifications of E rro rs..........................................—- 17

11

PAGE

Argument .......................................................................... 18

I. The District Court by refusing to grant injunc

tive relief failed to carry out the U. 8. Supreme

Court’s mandate, enabled discriminatory prac

tices to continue, and thereby deprived appel

lants of an enforceable right to use public travel

facilities in Mississippi on a nonsegregated

basis .................................................................... 18

II. The lower court’s failure to recognize this case

as a class action and grant relief for the class

denies effective relief to appellants....... .......... 24

Conclusion........................................................................ 26

Appendix

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Declara

tory Judgment, May 3, 1962 ................................... la

Supplemental Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law

and Declaratory Judgment, July 25, 1962 .......... 9a

Order Amending Supplemental Findings of Fact,

Conclusions of Law, Declaratory Judgment, and

Letter, August 24, 1962 ......................... 14a

Citations

Cases:

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss.

1961), 368 IT. S. 346; 369 U. S. 31 (1962) .............. 2,11

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958);

287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ................................ 18,19

Boman v. Birmingham Transport Co., 280 F. 2d 531

(5th Cir. 1960) ......................................................... 19

Ill

PAGE

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 (1960) .............. 18

Brooks v. City of Tallahassee, 202 F. Supp. 56 (N. D.

Fla. 1961) ........................................... ................... 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495

(1954) ...................................................................... 24

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of Clarendon County,

311 F. 2d 107 (4th Cir. 1962) .......... .............................................. 24, 25

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) ................................................. 19

Bush y. Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156,

165 (5th Cir. 1957) .................................................. 24

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp.

42 (E. D. La. 1960) .................................................. 22

Bush y. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491,

499 (5th Cir. 1962) .................................................. 25

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (4th Cir. 1951),

cert, denied, 341 U. S. 941 (1951) ........................ 19

Clark v. Thompson, No. 19961 (5th Cir. Mar. 6, 1963) 25

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio,

228 F. 2d 853, 857 (6th Cir. 1956), cert, denied, 350

U. S. 1006 ................................................................ 23

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied, 353 U. S. 924 (1957) ........................ 22, 24

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 (1958) ........................ 24

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1956) ................. 18,19, 20

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284 F. 2d

631 (4th Cir. 1960) .................................................. 22

I. C. C. and United States v. City of Jackson, 206 F.

Supp. 45 (S. D. Miss. 1962) 14

iy

PAGE

Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M D

Ala. 1961) ..........................................................

Meredith v. Pair, 298 P. 2d 696; 305 P. 2d 343 (5th

Cir. 1962) ...................

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946) .................

NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co., 297

I. C. C. 335 (1955) ..............................

20

18, 23

18

20

Potts v. Flax, F. 2d----- (5th Cir. Feb. 6, 1963) 24, 25

Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord, 202 P. Supp. 59 (N. D. Ala.

1961), affirmed, Hanes v. Shuttlesworth, 310 P. 2d

303 (5th Cir. 1962) .......................................... 26

Union Tool Company y. Wilson, 259 U. S. 107, 112 .... 22

United States v. City of Montgomery, 201 P. Supp.

590, 594 (M. D. Ala. 1962) ...................................... ’ 19

United States v. Lynd, 301 F. 2d 818 (5th Cir. 1962) 23

United States v. Parke, Davis & Co., 365 U S 125

(1961) ...................................................................... 22

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S 629 633

(1953) .............................................................. 22

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert. den. 369 U. S. 850 ........................ ’ oq

Statutes, Regulations, and Rules

Mississippi Code, Sections:

2351 .....................................

2351.5 ..........................

2351.7 ....................

V

PAGE

4065.3 .................................................................... 2

7784 ..................................................................... 1

7785 ........................................................................ 1

7786 ........................................................................ 1

7786-01 .................................................................. 1

7787.5 .................................................................... 1

Jackson City Ordinance, Jan. 12, 1956, Minute Book,

“FF ”, p. 149...... ..................................................... 1,19

Regulations

49 C. F. R. 1802 ................................................. 19

Rules

F. R, C. P. 23(a)(3) ............................................ 24

I k the

Hutted States Olmtrt nf Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 20,372

Samuel Bailey, et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

J oe T. P atterson, et al

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

A. P rocedu ra l S u m m ary

This case was brought by appellants, three Negro resi

dents of' Jackson, Miss., on June 9, 1961, as a class action

to end state-imposed racial segregation in public trans

portation facilities in the City of Jackson and State of

Mississippi (R. Vol. I, 2-16). When the suit was filed,

Mississippi and the City of Jackson, required and enforced

racial segregation in intrastate and interstate transporta

tion and related terminal facilities by state statutes and

a city ordinance.1 The State expresses its general policy in

1 Title 11, Sections 2351, 2351.5 and 2351.7, and Title

7734, 7785, 7786, 7786-01, 7787.5, Mississippi Code

(1942) ; Jackson

“F F ”, p. 149.

City Ordinance, Jan. 12, 1956,

18, Sections

Annotated

Minute Book

2

17 Miss. Code, Ann., Section 4065.3 which is : “to prohibit

by any lawful, peaceful, and constitutional means, the

causing of a mixing or integration of the white and Negro

races” in public facilities. The suit seeks an injunction

against the enforcement, throughout the state, of such stat

utes and enforcement of the city ordinance. This suit also

seeks to enjoin defendant common carriers, operating in

the City and/or State, including the Jackson City Lines,

Inc., the Illinois Central Railroad, the Continental South

ern Lines and the Southern Greyhound Lines, from main

taining segregated seating on their carriers and/or sepa

rate depots and services for passengers wherever located

in the State. Finally, the suit seeks injunctive relief against

segregated facilities in the Jackson Municipal Airport.

A three-judge court was designated (R. Vol. I, 20), and

the case was heard on September 25-28, 1961, following

which the court ruled 2-1 on November 17, 1961, to invoke

the doctrine of federal abstention “to give the State Courts

of Mississippi a reasonable opportunity to act.” 199 F.

Supp. 595 (R. Vol. IV, 705-06). On appeal, the United

States Supreme Court in a per curiam opinion on Febru

ary 26, 1962 vacated and remanded the case. 369 U. S. 31

(R. Vol. IV, 714). The Court ruled that the question

whether a state may require racial segregation on inter

state or intrastate transportation facilities is so well settled

that a three-judge court is not required.2 And on March

23, 1962, the case was returned to the District Court “for

expeditious disposition of appellant’s claims of right to

unsegregated transportation service” (R. Vol. IV, 718).

2 Plaintiffs’ motion for an injunction enjoining certain state

court breach of the peace prosecutions to which these appellants

were not parties, denied by the District Court, and the United

States Supreme Court pending appeal, 368 U.S. 346, was affirmed.

3

Upon remand, appellants, on April 19, 1962, moved in

the District Court for immediate relief in accordance with

the opinion and judgment of the Supreme Court (E. Vol.

IV, 719). The motion prayed for injunctive relief against

all appellees as set forth in the amended complaint. Appel

lants also filed a proposed judgment (E, Vol. IV, 745).

The District Court entered findings of fact and conclu

sions of law on May 3, 1962, based on which, all injunctive

relief was denied. A declaratory judgment issued by that

court (E. Vol. IV, 740) stated merely that each of the ap,

pellants has a right to unsegregated transportation service

from the appellees. Class relief was denied. In addition,

all Mississippi segregation statutes and the city ordinance

attacked in the case were declared void as violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The court retained jurisdiction in

the case for “the entry of such further orders and relief as

may be subsequently appropriate” (E. Vol. IV, 741).

Appellants promptly filed motions to Amend the Find

ings of Fact and for Further Eelief (E. Vol. V, 814), and

filed in support thereof affidavits concerning continuing

segregation (E. Vol. V, 751-784).

On May 31, 1962, a hearing was held on this motion (E.

Vol. V, 813-48), following which the District Court on July

25, 1962 filed supplemental findings of fact and conclusions

of law (E. Vol. V, 785). Based on these findings a supple

mental declaratory judgment was issued again merely af

firming the right of the three appellants to unsegregated

service, and again denying class relief and injunctive relief

(E. Vol. V, 790). The order made no mention of appellants’

complaint that the carriers were continuing to maintain

separate waiting rooms outside of which the City is con

tinuing to maintain racial signs.

On August 4, 1962, appellants for the third time moved

the court to further amend and supplement its findings of

4

fact alleging that Negroes were still being discriminated

against in the Jackson Municipal Airport restaurant (R.

Vol. V, 791). Attached to this motion were several affi

davits reporting instances of discrimination at the Airport

restaurant (R. Vol. V, 793-812). On August 24, 1962, the

District Court entered an order sustaining in part and

overruling in part appellants’ motion. Based on its find

ings the court concluded that all travel facilities were avail

able to plaintiffs without discrimination of any kind and

that no injunctive relief was required (R. Vol. V, 848-49).3

The plaintiffs appealed on August 30, 1962 stating as

the basis therefor: (a) the court’s refusal to grant injunc

tive relief against the defendants, (b) the court’s refusal

to recognize the class nature of the action by limiting relief

granted to the three named plaintiffs, and, (c) the court’s

refusal to enjoin the City of Jackson from maintaining signs

designating the dual waiting rooms of the Illinois Central

Railroad, Continental Southern Lines and Southern Grey

hound Lines, as “colored” or “white” (R. Vol. V, 852).

B. The E vidence P r io r to R u ling by S u p rem e Court

The bulk of the evidence introduced in support of appel

lants’ claims was obtained during a three day hearing before

the three-judge District Court in September 1961 (R. Vol.

I, 66-Vol. IV, 627). At this hearing, the three appellants,

all Negro residents of Jackson, Mississippi, testified that

they had experienced racial segregation while using vari

ous carriers and facilities of the appellees. They indicated

that they sought through the case to obtain relief from

such d isc rim in a to r travel practices not only for them

selves, but for all Negroes similarly situated (R. Vol. I,

3 The findings of fact, conclusions of law and declaratory judg

ments entered by the court below on May 3, 1962, July 25, 1962

and August 24, 1962 are set forth in the Appendix to this brief.

5

109, 121, 141). None of the appellants had been arrested

or threatened with arrest for breaching any of the Missis

sippi segregation statutes, and none had attempted to vio

late them (R. Yol. I, 120, 142). However, appellant Broad

water as early as 1957 wrote to each carrier, complaining

of its segregation policy, but to no avail (Pis. Exhs. 1-8,

R. Yol. I, 96-99).4

In addition to appellants, several witnesses, all members

of the class on whose behalf this action is prosecuted,

testified concerning the means by which racial segregation

has been imposed upon them and others throughout the

State in the use of the various travel facilities involved in

this suit. Representatives of the State, City, Airport Au

thority and the common carriers were also called to testify,

and information obtained via discovery procedures from

some of the appellees was introduced, all of which evidence

confirmed the allegations of segregation in Mississippi

travel facilities.

1. S tate o f M ississippi.

Attorney General Joe T. Patterson testified that he was

familiar with the state travel segregation statutes (R. Vol.

Ill, 411), and indicated that “if conditions arise to such a

point that I thought it necessary to bring them in effect

• • •” he would enforce them (R. Vol. Ill, 425, 433). He

denied having prosecuted or threatened to prosecute any

one under them (R. Vol. Ill, 416, 420), but admitted that

he had certainly not made any public announcement or

written any opinions as attorney general to the effect that

these laws would not be enforced (R. Yol. Ill, 439).

4 On cross-examination, the plaintiffs admitted that not all mem

bers of their class agreed with their action, and indicated that

they had not told others in the class of their plans to file suit

(E. Yol. I, 109-110, 121, 141).

6

2 . City o f Jack so n .

The Mayor of the City of Jackson testified that the city

ordinance enacted in 1956 requiring segregation of the

races in travel facilities reflected the city’s policy of main

taining peace and prosperity by a “separation” of the races

(R. Vol. II, 348, 351-52). Chief of Police, William D. Ray-

field, testified that racial signs over local terminal facilities

were erected at his direction in 1956 in order to “direct

the races to their respective waiting room facilities and

also to assist the police department in maintaining peace

and order” (E. Vol. II, 359). He testified further that

signs were placed pursuant to the city ordinance, but that

to his knowledge no Negro has ever been arrested for vio

lating the signs, per se (E. Vol. II, 359-60).

Appellants introduced into evidence Exhibits 32, 33, 34

and 35, four volumes of approximately 190 affidavits and

judgments of breach of the peace convictions of persons

arrested in waiting rooms of defendant carriers while

peacefully testing the segregation policy during the sum

mer of 1961 (E. Vol. Ill, 482).

Jackson Police Chief Bayfield acknowledged that Negroes

and whites have been arrested by city police in the terminals

and charged with breach of the peace (E. Vol. II, 367-69).

Captain J. L. Eay, who made many of the arrests, admitted

that the persons arrested were not loud or otherwise dis

orderly but justified their arrest by claiming that other

persons, not arrested, threatened to cause trouble unless

these persons were removed. Captain Eay also claimed

the police officers exercised their judgment by removing

what he referred to as the “root of the problem” (E. Vol.

II, 370-75).

7

3. Jack so n M un ic ipal A irp o r t A u th o rity .

At the time this suit was filed, the Authority operated

segregated restroom facilities, water fountains (R. Vol. I,

101, Vol. II, 232), and leased the restaurant (Exh. 27, R.

Vol. II, 237) to a lessee who admittedly discriminated

against Negro patrons (R. Vol. II, 210-12).

Witness Medgar Evers, a field representative of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People (NAACP), testified that he had observed the racial

signs in the airport waiting room, and had been refused

service in the restaurant by a waitress who told him that

they didn’t serve colored people (R. Vol. II, 215). Be

cause of the humiliation and futility of seeking service,

he has never attempted to eat in the restaurant again al

though he uses the airport fifteen to twenty times a year

(R. Vol. II, 229).

The lessee of the Airport restaurant, Cicero Carr, testi

fied that Negroes were served only at a counter located in

a back room (R. Vol. II, 209-11).

4 . C on tin en ta l S o u th e rn L ines, Inc. (T ra ilw ay s).

The Trailways Bus Company admitted that its terminal

in Jackson, Mississippi, contains two separate waiting

rooms with separate facilities, and that a sign over the out

side door of each waiting room, installed pursuant to

Mississippi statute, designates the waiting room for either

white or colored passengers. Signs placed on the sidewalk

in front of each waiting room further designate the waiting

room for white or colored by order of the police depart

ment. Trailways denies having placed or maintained the

sidewalk signs. In addition to the Jackson terminal, Trail-

ways admitted operating or utilizing terminal facilities in

18 Mississippi communities: Biloxi, Canton, Columbia,

Columbus, Corinth, Greenville, Greenwood, Grenada, Gulf

port, Hattiesburg, Laurel, Meridian, Natchez, Oxford,

Starkville, Tupelo, Vicksburg and Winona (E. Vol. I, 183).

Trailways Bus Lines received complaints about its segre

gated terminal facility in Jackson, as far back as 1957

(Pis. Exh. 7, E. Vol. I, 99). In 1958, Medgar Evers was

ordered to the back of a Trailways Bus by the driver (E.

Vol. II, 216). When he refused, the driver called a police

man (E. Vol. II, 217). After conversing with the police

officers, Evers was permitted to reboard the bus and again

seated himself in the front (E. Vol. II, 219). The bus

started on its way but was halted by a taxicab driver sev

eral blocks from the terminal, who boarded the bus and

physically attacked Evers in the presence of the bus driver

(E. Vol. II, 220).

Johnny Frazier, a high school student, reported that a

Trailways Bus driver cursed him for refusing to move to

the rear and as a result of complaints made by this driver

to the police in Winona, Mississippi, Frazier was taken

from the bus, beaten into unconsciousness, thrown in jail,

and charged with breach of the peace (E. Vol. II, 282-85).

Mrs. Mildred Cozy purchased reserve seats on a Trail-

ways Bus from Jackson to Vicksburg, Mississippi which

seats were not honored by the hostess on the bus who forced

her to sit in the rear (E. Vol. II, 330).

Thomas Armstrong, a college student was arrested when,

having purchased a bus ticket from Jackson to New Orleans,

he entered the Trailways Bus terminal marked for white

passengers (E. Vol. II, 261). Armstrong was subsequently

tried and convicted for a breach of the peace although there

was no evidence of any disturbance by him (E. Vol. II, 268-

69, Exh. 28, E. Vol. II, 271).

9

5. S o u th e rn G rey h o u n d L ines,

The Greyhound terminal in Jackson is divided into two

separate self-sufficient waiting rooms, over the door to each

of which, pursuant to state statute, there is a sign designat

ing the waiting room for either white or colored intrastate

passengers. Signs on the sidewalk in front of each waiting

room, not placed or maintained by the defendant, designate

the room for colored or white only, by order of the police

department. This defendant admitted operating or utiliz

ing terminal facilities in 15 other Mississippi communities:

Biloxi, Brookhaven, Clarksdale, Columbus, Greenville,

Greenwood, Gulfport, Hattiesburg, Laurel, McComb, Merid

ian, Natchez, Tupelo, Vicksburg, Yazoo City (R. Vol. I,

178-79).

Witness Johnny Frazier reported that in 1960, he boarded

a Greyhound Bus in Atlanta bound for Mississippi and

was ordered by the driver to move to the rear (R. Vol. II,

279) , and was again asked to move to the rear by another

driver when the bus arrived in Montgomery (R. Vol. II,

280) .

In September 1961, witness Helen O’Neill boarded a

Greyhound Bus in Jackson intending to go to Clarksdale,

Mississippi (R. Vol. II, 304), the driver intimated that she

would have to move to the rear, she refused and the driver

summoned a policeman who ordered her to the rear and

arrested her when she again failed to move (R. Vol. II,

307-08).

Mrs. Vera Pigee, intending to ride a Greyhound Bus

from Clarksdale, Mississippi to Memphis, Tennessee, was

not permitted to board the bus by the driver until white

patrons had boarded (R. Vol. II, 324-26).

10

6. Illino is C en tra l R a ilro a d , Inc.

The Illinois Central train depot in Jackson, Mississippi

contains separate waiting rooms and facilities for Negro

and white passengers. Each waiting room is designated

for either the colored or white race by signs placed both

on the sidewalk in front of each facility and in the railroad

terminal at the bottom of the stairs leading from the train,

which signs the Railroad denies any “maintenance, super

vision or control thereasto.” Illinois Central maintains a

depot or terminal facility at each Mississippi community

where Illinois Central Railroad trains make regular stops,

which stops are set forth in the copy timetable (Ptls. Exhs.

21-24, R. Vol. 1,196).

It appears that the railroad actively segregated its pas

sengers both in the terminal and on the trains. Appellant

Broadwater reports having been subjected to such segre

gation in 1957 (R. Vol. I, 76-8), and wrote a letter of com

plaint to the railroad (R. Vol. I, 80).

In August 1961, Wilma Jean Jones, a high school stu

dent, reported that she and two companions intending to

travel from Clarksdale, Mississippi to Memphis, Tennes

see on the Illinois Central were refused tickets by a railroad

employee because they were in the waiting room reserved

for whites (R. Vol. II, 316-20). Local police were called

and they were arrested and placed in jail. Miss Jones was

15 years old at the time (R. Vol. II, 321).

7. Jack so n City L ines, Inc.

When this suit was filed each Jackson City Lines Bus

carried a sign directing Negroes to seat from the rear and

whites to seat from the front (R. Vol. I, 102). The Super

intendent admitted that signs designate certain sections

of the bus for Negro and white (R. Vol. II, 197-98), and

11

indicated that signs were required, not by company policy,

but by the City ordinance (R. Vol. II, 199). However, a

driver testified that the signs have been used for 25 years

(R. Vol. Ill, 521), and under company policy, if a passen

ger seats himself in a section reserved for the other race

and refuses to move at the direction of the driver, the driver

is instructed to refuse to move the bus (R. Vol. II, 200-201).

Doris Grayson, a college student, testified that in April

1961 she and two companions were arrested when they sat

in the section reserved for whites and refused to move at

the order of the bus driver and police (R. Vol. II, 244-45,

247-49). The group was subsequently charged and con

victed of breach of the peace and fined $100 and 30 days

in jail (R. Vol. II, 250).

C. T he S u p rem e C ourt D ecision

Based on the evidence summarized above, the United

States Supreme Court in its per curiam opinion of Febru

ary 26, 1962 (R. Vol. IV, 714-717), stated: “We have

settled beyond question that no State may require racial

segregation of interstate or intrastate facilities . . . the

question is no longer open; it is foreclosed as a litigable

issue” (R. Vol. IV, 716). The Court then remanded the

case to the District Court “for expeditious disposition, in

light of this opinion, of the appellants’ claims of right to

unsegregated transportation service” (R. Vol. IV, 717).

D. D istric t C ourt F indings, Conclusion and

Judgm ent o f May 3 , 1 9 6 2

The District Court, however, when it entered its find

ings of fact and conclusions of law on May 3, 1962, denied

all injunctive relief sought by appellants. The court below

found that appellants were neither arrested nor threatened

with arrest under state segregation or breach of the peace

12

statutes, that they did not represent a class, and that the

evidence of racial discrimination in city and state travel

facilities indicated no effort to control the travel activities

of Negroes, but constituted merely “isolated instances of

improper behavior on the part of certain law enforcement

officers” (R. Yol. IV, 734).

E. The E vidence A fter D istric t C ourt’s

R uling of May 3 , 1 9 6 2

Following the failure of the District Court to grant any

injunctive relief to appellants or their class in its order

filed May 3, 1962 (R. Vol. IV, 740-41), appellants filed a

motion for further relief alleging continuing racial discrim

ination in appellees’ travel facilities, in response to which

certain of the appellees filed affidavits of their own.

The manager of the Jackson City Bus Lines averred that

he had removed all racial signs from his buses and had

advised all drivers to operate the buses without regard to

race (R. Vol. IV, 727-28). Officials of the Greyhound and

Trailways Bus Lines each reported that all racial signs

previously placed on their terminals in compliance with

state statute had been removed by November 1, 1961, in

accordance with a new regulation of the Interstate Com

merce Commission (R. Vol. IV, 729-31).

On May 18, 1962, appellant Broadwater inspected travel

facilities in Jackson and reported to the court that in the

Municipal Airport terminal signs designated water foun

tains and rest rooms as “White” and “Colored”, a Jackson

City Lines bus contained a sign “City Ordinance—White

passengers take front seats. Colored passengers take rear

seats”, and the terminals of the Illinois Central Railroad,

the Greyhound Bus Lines and the Continental Trailways

Lines continued to operate dual waiting rooms designated

by signs outside of each reading either “Colored Waiting

13

Room” or “White Waiting Room,” which signs were placed

on the sidewalk by the Jackson police force (R. Vol. V,

751-53).

In response, the Jackson City Lines filed an affidavit by

its manager admitting that signs such as reported by

appellants had not been removed from the Lines’ buses

through an oversight, and that all of such signs have been

removed (R. Vol. V, 753-56). The Municipal Airport Au

thority acknowledged the continued presence of racial signs

on its rest rooms and drinking fountains, and denied that

the signs are enforced, claiming they “are maintained for

the sole purpose of assisting members of both races who

voluntarily desire to use said facilities separately and for

no other purpose” (R. Vol. V, 757, 829). Similarly, Chief

of Police Rayfield reported that the signs placed by the

Jackson Police Department on the sidewalks outside the

railroad and bus terminals were installed to facilitate volun

tary segregation, stating that the “signs are not now being

enforced and have never been enforced by the City of Jack-

son or its Police Department” (R. Vol. V, 759). In support

of this claim, an affidavit prepared by a city detective was

filed reporting that during the period from April 3 to May

24, 1962, colored persons including Negroes, Chinese, an

Indian and a soldier from Pakistan had been seen using

“all” waiting room facilities without hindrance (R. Vol. V,

761).

Appellants filed affidavits indicating that Negroes are

being hindered in attempts to use travel facilities on a non-

segregated basis, not only in Jackson but in terminals op

erated by appellee carriers in other sections of the State.

Royce Smith, a college student, was refused service by a

white waitress in the Trailways Bus Terminal restaurant in

Meridian, Mississippi, on May 30, 1962, and was then har

assed by a local police officer (R. Vol. V, 763). Mrs. Clarie

14

Collins Harvey, a Mississippi businesswoman, on May 22,

1962, was forced out of the white waiting room of the

Continental Trailways Terminal in Gulfport, Mississippi by

local police officers, and requested to take a rear seat by the

hostess on the Trailways bus (R. Vol. V, 765-66). Derrick

Bell, one of appellants’ attorneys flew into Jackson on May

30, 1962, for the hearing on plaintiffs’ motion for further

relief and was refused service in the Jackson Airport ter

minal restaurant, and asked to leave by City police officers

(E. Vol. V, 768-69).

Following the filing of the above affidavits, and during

the course of the May 31st hearing on appellants’ motion

for further relief, the court below specifically rejected ap

pellants’ contention that the carriers must not maintain

separate waiting rooms. “I think the carriers have a right

to have as many rooms as they want—two, four or what-not

—as long as there are no signs or any effort to compel any

separation of the races” (R. Vol. V, 830). Appellants also

argued that the Jackson police should not be permitted to

maintain signs on the sidewalks designating the waiting

rooms of the carriers for one race or the other. However,

the court below did not reply to the City’s response that

the sidewalk signs are maintained to facilitate voluntary

segregation, and that such use of the signs had been ap

proved by the court in I. C. C. v. City of Jackson (R. Vol. V,

831).

The court below did indicate at the May 31st hearing

that the signs on the airport facilities and the restaurant’s

discriminatory policy are improper (R. Vol. V, 844). Sub

sequently, the manager of the airport reported to the court

that all signs on water fountains and on the doors of the

rest rooms had been removed (R. Vol. V, 770-71); and the

manager and lessee of the airport restaurant, Cicero Carr,

averred his intention to serve all persons without discrim-

15

ination because of race, creed or color in the restaurant

which he was converting into a stand-up counter service

(R.Vol. Y, 772).

On June 12, 1962, David Campbell, a white ministerial

student visited the airport restaurant and reported that

the conversion consisted of a partition separating a stand-up

lunch counter, at which a policeman was stationed, from a

larger dining area containing tables and chairs. A waitress,

without solicitation, offered Campbell a seat and escorted

him into the dining area over the entrance to which a sign

was placed which read “Employees and flight personnel

only.” Several other white persons were being served in

this area (R. Vol. V, 773-74). After ordering, Campbell

attempted to question the waitress about the sign, but

she refused to comment (R. Yol. V, 775). Another waitress

indicated that the sign and partition was intended to

frustrate integration attempts (R. Vol. V, 776). The

waitress who served Campbell later stated that she be

lieved that he was an airline employee, and that sit-down

service was restricted to airport employees and flight per

sonnel (R. Vol. V, 783-84).

F. D istric t C ourt S u pp lem en ta l F indings, Conclusions

and Judgm ent o f July 2 5 , 19 6 2

In this order, the District Court took notice that the

racial signs over the airport terminal’s water fountains

and rest rooms had been removed, that the Jackson City

Lines had removed all racial signs from the buses, that

facilities of all carriers and the airport authority are now

being used by all races without discrimination, and that

the airport restaurant lessee has discriminated against

Negro passengers but such discrimination has terminated

(R. Vol. V, 788-89). The court again found that appellants

were not entitled to any injunctive relief (R. Vol. V, 790).

16

G. The E vidence Follow ing D ictric t C ou rt’s

R uling o f July 2 5 , 19 6 2

Appellants, in support of a motion filed to amend the

July 25th supplemental findings as to Cicero Carr, the

restaurant lessee, filed five affidavits prepared by one Negro

and four whites, each of whom attested to the continued

operation of the airport restaurant on a racially dis

criminatory basis (E. Yol. V, 793-810). The affiants re

ported that while tables in the restaurant’s dining area all

contained “reserved” signs, no reservations were necessary

for white patrons, while Negro patrons were denied en

trance to the dining area entirely and served only at the

lunch counter (E. Vol. V, 801-05).

Following the filing of these affidavits, the manager of

the Jackson Municipal Airport Authority filed an affidavit

admitting that appellants’ complaints indicated continuing

discrimination in the operation of the airport restaurant

facilities (E. Vol. V, 811) and as a result the Airport

Authority had terminated the lease under which the lessee,

Cicero Carr, had operated the airport restaurant (E. Yol.

V, 811).

H . D istric t C ourt’s A m en dm en ts to S u pp lem en ta l

F indings, Conclusions and Judgm ent of

A ugust 2 4 , 19 6 2

The court below took notice that the restaurant lessee,

Cicero Carr, had been continuing to operate the airport

restaurant on a segregated basis, but that he no longer

held any interest therein. The court then found that each

of the three appellants has a right to unsegregated service

at the airport restaurant but again denied all injunctive

and class relief (B. Vol. V, 847-49).

17

Specifications of Errors

1. The court below erred in refusing to enjoin all appel

lees from enforcing any statute, ordinance, policy, practice,

regulation or custom requiring, permitting or encouraging

racial segregation on common carriers and terminal fa

cilities.

2. The court below erred in refusing to grant injunctive

relief for the class which appellants represented as pro

vided for in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule

23(a)(3).

3. The court below erred in refusing to enjoin the City

of Jackson, including the Mayor, City Commissioners and

Chief of Police from:

(i) continuing to arrest, harass and intimidate ap

pellants and members of their class, in connection with

the exercise of their right to use public transportation

facilities and services without segregation or discrimi

nation ;

(ii) continuing to post signs or other indicia desig

nating segregated or separate facilities for Negro and

white passengers on or near passenger facilities or

services.

4. The court below erred in refusing to enjoin Con

tinental Southern Lines, Southern Greyhound Lines and

Illinois Central Railroad, Inc., from continuing to maintain

and operate separate or dual waiting rooms, and other

facilities previously required for segregation of the races

in the State of Mississippi, from posting or permitting to

be posted racial designations on or near such terminals or

facilities, and from in any way enforcing, encouraging, or

permitting any racial segregation of passengers on carriers

or in terminal facilities.

18

ARGUMENT

I

The District Court by refusing to grant injunctive re

lief failed to carry out the U. S. Supreme Court’s man

date, enabled discriminatory practices to continue, and

thereby deprived appellants of an enforceable right to

use public travel facilities in Mississippi on a nonsegre-

gated basis.

In its per curiam decision of February 26, 1962, fore

closing as a litigable issue the question of whether Negroes

may be required to submit to racial segregation in public

travel facilities, the Supreme Court referred to three de

cisions dating back to 1946. Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S.

373 (1946); Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1956);

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 (1960). The intention

of these and many other decisions by federal courts and

agencies has been to remove the burden of racial discrimi

nation from public travel.

But despite the almost solid line of precedent stretching

back fifteen years, appellants in mid 1961 were able to

allege and prove that in Mississippi these decisions have

been almost completely ignored.

(a) The State of Mississippi by statute required, and

its Attorney General was willing to enforce by prosecution

if necessary, racial segregation on common carriers and

in waiting room facilities maintained by common carriers

in total disregard of Morgan v. Virginia, supra; Boynton

v. Virginia, supra; and Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750

(5th Cir. 1961). The segregation statutes have been de

clared void, but the general state policy of racial segrega

tion recognized by this Court in Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d

343 (5th Cir. 1962), has not been altered.

19

(b) The City of Jackson’s ordinance requiring racial

segregation on local buses was enacted in 1956, and bliss

fully maintained in spite of the Supreme Court’s decision

in Gayle v. Browder, supra, later in the same year, and this

Court’s ruling in Boman v. Birmingham Transport Co.,

280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960). The court below voided the

ordinance, but the City’s police force continues even now

to maintain racial signs outside of terminal waiting rooms

in the face of this Court’s holding in Baldwin v. Morgan,

287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961), that such signs even to fa

cilitate “voluntary segregation” are constitutionally im

permissible. Policemen continue to arrest and harass pas

sengers who seek to use such facilities on a nonraeial

basis, ignoring Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (4th Cir.

1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 941 (1951); Boman v. Birming

ham Transport Co., supra, and Baldwin v. Morgan, 251

F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958).

(c) The Jackson Municipal Airport Authority maintained

segregated rest rooms and drinking fountains in its terminal

waiting room and condoned a policy of racial discrimina

tion by the lessee of its terminal restaurant, and later at

tempted, notwithstanding Baldwin v. Morgan, supra;

Brooks v. City of Tallahassee, 202 F. Supp. 56 (N. D. Fla.

1961); and United States v. City of Montgomery, 201 F.

Supp. 590, 594 (M. D. Ala. 1962), to justify the continued

maintenance of racial signs as aids to voluntary segrega

tion (R. Vol. V, 828-29). The Authority’s counsel even

contended for a time (R. Vol. V, 828) that it could not

control the segregated seating policy of the lessee of its

restaurant, ignoring Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 IT. S. 715 (1961).

(d) The Greyhound and Trailways Bus Lines maintained

racial signs over their separate waiting rooms until No

vember 1, 1961, when an I. C. C. order (49 C. F. R. 180a)

20

specifically required their removal. Moreover, these car

riers, along with the Illinois Central Railroad, have per

mitted without protest the arrest, harassment and humilia

tion of their passengers by local police officers and, sub

mitted meekly to the clearly illegal placing of signs by

local police designating their dual waiting rooms as for

white or colored passengers, Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199

F. Supp. 210 (M. D. Ala. 1961), and by the I. C. C.

in NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co., 297

I. C. C. 335 (1955). In the State of Mississippi, it may be

necessary to require the carriers to close the usually small,

inadequate waiting room facility formerly designated for

Negro use. This action would end the recurring problem

of police officers, carrier employees and private citizens

who “voluntarily” enforce segregation rules, against pas

sengers seeking to use facilities formally designated for

whites.

(e) The Jackson City Bus Lines continued without pro

test to obey the city ordinance requiring segregated seating

long after the invalidity of such laws was clearly estab

lished in Gayle v. Browder, supra, and on their own initia

tive, instituted a policy of requiring bus drivers to refuse

to move a bus when passengers seated themselves in viola

tion of the segregation ordinance (R. Vol. II, 201). This

policy had the effect of a call to local police officers who

generally responded by ordering the offending passenger

off the bus and arresting him if he refused to leave (R.

Vol. II, 248-49, Vol. Ill, 522-24).

Notwithstanding this clear evidence that some appellees

were continuing policies of segregation, and that others

had abandoned such policies with obvious reluctance, the

court below three times refused to grant any injunctive

relief to appellants (App. 8a, 13a, 16a). Appellants’ evi

dence of discrimination was dismissed as “isolated instances

21

of improper behavior” (App. 3a), even though the record

supports a finding that the infrequency of incidents is due

to the fact that in Mississippi, segregation is so deeply

embedded that protest is futile.

When Medgar Evers, an official of the NAACP, admits

that having been refused service once at the airport restau

rant, he was so humiliated that he neither reported the

incident nor attempted to be served there again (R. Vol.

II, 229), he makes out an a fortiori case for a large per

centage of Mississippi Negroes.

When Dr. Jane McAllister, a Doctor of Philosophy at

Jackson State College who for ten years has commuted

by bus from Jackson to Vicksburg, Mississippi, testified

that she was ordered to the rear seat of the bus by a

Jackson policeman, the court found “she was treated

rudely,” but added “As a colored person, she had always

sat where she wished on the bus” (App. 3a). The court

failed to place any significance on the fact that as a colored

person in Mississippi, even with a doctor’s degree, Dr.

McAllister chose regularly to sit in a seat just in front

of the rear seat (R. Vol. Ill, 395), stated “I just never

thought of sitting in front” (R, Vol. Ill, 409), and was

subpoenaed to appear in court to testify to an experience,

“I have tried to forget * # # because it was very humili

ating, * * * ” (R. Vol. Ill, 394-95).

Despite the testimony of Medgar Evers, Dr. McAllister

and several other Negro witnesses, including one of ap

pellants’ attorneys, each of whom testified to an “isolated

instance of improper behavior” when they sought to use

travel facilities on a non-segregated basis, the trial judge,

following the entry of an amended supplemental declara

tory judgment where for the third time, all injunctive relief

was denied (App. 16a), wrote to all counsel advising that

all defendants are complying with the declaratory judg-

22

ment, “and I am definitely of the opinion that they will

continue to do so” (App. 17a).

Such “compliance” as was required by the declaratory

judgment cannot be enforced by the three appellants except

“by one or more supplemental complaints reciting the

matters and facts complained of” (App. 16a). The car

riers continue to maintain dual waiting rooms, outside of

which the City continues to maintain racial signs. Some

City policemen continue to harass and intimidate persons

seeking to use travel facilities on a nonsegregated basis,

and if any of the appellees evolve new methods of retain

ing the old racial system, appellants will have to file an

other lawsuit to obtain what the United States Supreme

Court ordered they be given in February 1962.

The appellants submit that the District Court’s refusal

to grant injunctive relief in this case where the evidence

is undisputed that they and other Negroes similarly situated

are being denied a constitutional right was an abuse of

discretion. Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284

F.2d 631 (4th Cir. 1960); Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 187 F. Supp. 42 (E. D. La. 1960). As Justice

Brandeis wrote in Union Tool Company v. Wilson, 259

U. S. 107, 112:

“Legal discretion # * does not extend to refusal

to apply well-settled principles of law to a conceded

state of facts.”

Even if appellees had discontinued all policies of racial

discrimination, justice, sound precedent and the public in

terest would require injunctive relief in this case. United

States v. Parke, Davis <& Co., 365 U. S. 125 (1961); United

States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629, 633 (1953). It was

this Court’s view in Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F.2d 922

(5th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 353 U. S. 924 (1957), that

23

equitable relief is as necessary in civil rights cases as in

antitrust litigation.

Even if there had been a voluntary cessation of the

alleged illegal conduct, the public interest in having

the legality of the practice settled militates against

a mootness conclusion in the absence of an affirmative

showing that there is no reasonable expectation that the

alleged wrong will be repeated. 240 F,2d at 925.

The Sixth Circuit has reached a similar conclusion. In

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, 228

F.2d 853, 857 (6th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 350 U. S. 1006:

If injunction will issue to protect property rights and

‘to prevent any wrong’; * * # it will issue to protect

and preserve basic civil rights such as these for which

the appellant seeks protection. While the granting

of an injunction is within the judicial discretion of

the District Judge, extensive research has revealed

no case in which it is declared that a judge has judicial

discretion by denial of an injunction to continue the

deprivation of basic human rights.

The unyielding attitude of the State of Mississippi and

its officials to the constitutional demand of nondiscrimina

tion is, by now, sufficiently well known to this Court to

render further discussion superfluous. Meredith v. Fair,

298 F.2d 696, 701 (5th Cir. 1962); United States v. Wood,

295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 369 IT. S. 850;

United States v. Lynd, 301 F.2d 818 (5tli Cir. 1962). Simply

stated, if the U. S. Supreme Court’s decision in this case

and the several federal decisions upholding appellants’

right to use public travel facilities on a nondiscriminatory

basis is to have practical meaning to appellants, then in

junctive relief as requested in the Complaint must be

granted.

24

II

The lower court’s failure to grant relief for the class

denies effective relief to appellants.

Appellants had standing to represent not only themselves

but, under the provisions of the Federal Eules of Civil

Procedure, Eule 23(a)(3), all Negroes similarly situated.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495 (1954);

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 (1958); Derrington v.

Plummer, 240 F.2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 353

U. S. 924 (1957).

The court below concluded that this is not a proper

class action stating that “the testimony of the plaintiffs

was conflicting as to the identity of the class purported

to be represented. They proved no authority to represent

any other person and admitted that other Negroes did not

approve of this action” (App. 4a). But there was no

conflict. Each of the appellants testified as the complaint

alleged (E. Vol. I, 6) that the suit was brought not only

for themselves, but for other Negroes similarly situated

(E. Vol. I, 109, 121, 141), a fact no less true because of

their admission that they had not discussed the suit with

other members of the class some of whom might not agree

with their actions (E. Vol. I, 109-10, 121, 141).

The requirements for a class action under the Federal

Eules of Civil Procedure, Eule 23(a)(3), are satisfied to

no less an extent in this case than in literally hundreds of

other similar actions. Potts v. F lax,----- F.2d ----- - (No.

19639, 5th Cir. Feb 6, 1963); Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 242 F.2d 156, 165 (5th Cir. 1957); Brunson v. Board

of Trustees of Clarendon County, 311 F.2d 107 (4th Cir.

1962). There was a common question of law concerning the

validity of various segregation laws, policies and prac

tices, arising out of the common fact situation that all

Negroes using public travel facilities are subjected to the

questioned racial procedures. The number of persons in

terested is far too great to make joinder practicable or

helpful, and while appellants stated a truism that some

members of the class might not agree with their actions,

there was no effort made by appellees to show that the

number of Negroes opposed to the suit was large, nor

appellants submit, could such a showing have been made.

For this reason, appellants also submit that the interests

of the group were adequately and ably represented, and

the relief sought was appropriate.

Indeed, it is the thrust of this Court’s opinion in Potts

v. Flax, supra, that appropriate relief for appellants re

quires relief for the class. As was there said, “By the

very nature of the controversy, the attack is on the un

constitutional practice of racial discrimination.” Potts v.

Flax involves public schools, but its teaching is entirely

appropriate here. Appellants did not bring this suit merely

to gain admission to white facilities, and thereby con

tribute actively to the class discrimination proscribed by

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F.2d 491, 499

(5th Cir. 1962). They seek desegregation of these facilities,

wdiich relief, by its very terms, requires that all Negroes

similarly situated must be included. Thus as was said in

Potts v. Flax, assuming arguendo a correct ruling by the

court below on the class action point, the relief to which

appellants were entitled required the entry of a general

decree. See also, Brunson v. Board of Trustees of Claren

don County, supra.

Appellants are aware that a panel of this Court has

affirmed in a recent per curiam decision a ruling of the

court below denying class relief in a case involving segre

gated recreational and library facilities in Jackson, Mis

sissippi, Clark v. Thompson, No. 19961, March 6, 1963. A

26

petition for a rehearing en banc was filed on March 22,

1963, and it is appellants’ position as set forth above that

the district court’s refusal to grant general relief in cases

seeking to desegregate public facilities is contrary to almost

all of the cases decided in the civil rights area. See Shuttles-

worth v. Gaylord, 202 F. Supp. 59 (N. D. Ala. 1961),

affirmed, Hanes v. Shuttlesworfh, 310 F.2d 303 (5th Cir.

1962). More importantly, it serves to deny effective relief

even to those directly involved in the suit.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for all the foregoing reasons, it is respect

fully submitted that the judgment of the court below should

be reversed and the case remanded with specific directions

that the appellants be granted the relief sought and such

other and further relief as may be just.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R. J ess Brown

1105% Washington Street

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellants

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

—R-1470—

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law,

and Declaratory Judgment

(Title Omitted—Filed May 3,1962)

This action was brought by three Negro citizens and

residents of Jackson, Mississippi, to enjoin the alleged en

forcement of certain Mississippi statutes which are alleged

to be unconstitutional. The statutes sought to be enjoined

are Title 11, Sections 2351, 2351.5 and 2351.7, and Title 28,

Secs. 7784, 7785, 7786, 7786-01, 7787, 7787.5, Mississippi

Code Annotated (1942), hereinafter referred to as Missis

sippi segregation statutes. Plaintiffs attack the constitu

tionality of said statutes.

The plaintiffs also seek to enjoin the arrests and prose

cutions of persons other than the plaintiffs under Sections

2087.5, 2087.7 and 2089.5 of the Mississippi Code Annotated

(1942), as amended in 1960, hereinafter referred to as Mis

sissippi breach of peace statutes. Plaintiffs do not contend

—R-1471—

that these statutes are unconstitutional. A three-judge Dis

trict Court was convened in this case under Title 28 TJ. S. C.

Section 2281. A hearing on plaintiffs’ motion for a pre

liminary injunction was consolidated with a hearing on the

merits. The three-judge Court abstained from further pro

ceedings pending construction of the challenged laws by

the state courts. 199 F. Supp. 595. Plaintiffs appealed,

and the Supreme Court of the United States denied a mo

tion for an injunction pending disposition of the appeal.

368 U. S. 346. The Supreme Court of the United States

held that this was not a proper matter for a three-judge

District Court, vacated the judgment, and remanded the

case to this Court for expeditious disposition of plaintiffs’

2a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Declaratory Judgment

claims of right to unsegregated transportation service.

----- IJ. S . ----- , 7 L. Ed. 2d 512. Accordingly, an order

has been entered herein dissolving the three-judge Court.

F i n d in g s o f F a c t

1. None of the plaintiffs has been arrested or threatened

with arrest under any of the segregation statutes attacked

in this case. The plaintiffs have not been arrested or threat

ened with arrest under any of the Mississippi breach of

peace statutes referred to in the amended complaint. The

plaintiffs have not been denied any right, privilege or

immunity claimed by them by virtue of said segregation

statutes.

2. The interests of the plaintiffs are antagonistic to and

not wholly compatible with the interests of those whom they

-R-1472—

purport to represent. They do not belong to a class which

would include the persons arrested and prosecuted in the

Mississippi Courts under the breach of peace statutes.

3. There have been no arrests or prosecutions under

the segregation statutes attacked in this case for many

years, and said statutes have not been enforced in Mis

sissippi.

4. Evidence offered by the plaintiffs affirmatively es

tablishes as a fact that none of the defendants has made

any effort to control the action of Negroes in any of the

terminals or on any of the carriers involved in this case.

3a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Declaratory Judgment

5. The evidence discloses isolated instances of improper

behavior on the part of certain law enforcement officers.

The fact that they are relatively few in number emphasizes

their absence as a general practice or policy. As much as

we would like to see it otherwise, law enforcement officers

are not infallible. Being human, there are those who are

guilty of improper conduct, but the evidence in this case

proves that such conduct is a rare exception rather than

the general practice. While we cannot condone the mistakes

made by a few law enforcement officers, we cannot indict a

municipality or a State because of isolated errors in judg

ment on the part of such officers. For instance, one of

plaintiffs’ witnesses testified that he used the Jackson air

port from fifteen to twenty times a year. On one occasion

an unidentified waitress refused to serve him in the res

taurant. He did not report this incident to anyone in

—B-1473—

authority with the airport or with the City. Plaintiffs’ wit

ness, Dr. Jane McAllister, testified that she had commuted

daily by bus from Jackson to Vicksburg, Mississippi, for

ten years. As a colored person, she had always sat where

she wished on the bus. On one occasion she was treated

rudely by a Jackson policeman. The same is true of several

other isolated instances reflected by plaintiffs’ evidence.

6. There was no evidence of any arrest in the City of

Jackson of a Negro prior to April, 1961, when the Freedom

Eiders began their much publicized visits to that City.

The arrests of those persons involved both white and col

ored people who were arrested at the same place and for

the same reason. Neither race nor color nor location of

facility being used had anything to do with those arrests.

4a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Declaratory Judgment

No such arrest was made under any of Mississippi’s seg

regation statutes. The cases arising out of those arrests

are now pending in the Courts of the State of Mississippi,

and this Court should not attempt to determine the merits

of those State Court actions.

7. All segregation signs have been removed from the

premises of all of the carrier defendants. All facilities in

all terminals of the carrier defendants are now being freely

used by members of all races, and there is no justification

for the issuance of an injunction in this case.

—R-1474—

C o n c l u s io n s o f L a w

1. This Court has jurisdiction of the parties hereto and

the subject matter hereof.

2. This is not a proper class action, and no relief may

be granted other than that to which the plaintiffs are per

sonally entitled. In the complaint plaintiffs purported to

represent themselves and “other Negroes similarly situ

ated”. In the amended complaint plaintiffs purported to

represent “Negro citizens and residents of the State of

Mississippi and other states”. Plaintiffs’ right to represent

anyone but themselves was put in issue by the pleadings.

The testimony of the plaintiffs was conflicting as to the

identity of the class purported to be represented. They

proved no authority to represent any other person and

admitted that other Negroes did not approve of this action.

On appeal an attempt was made to broaden the alleged

class to include white and colored freedom riders. Whether

this is a proper class action involves a question of fact.

Flaherty v. McDonald, D. C. Cal., 178 F. Supp. 544. The

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Declaratory Judgment

plaintiffs cannot make this a legitimate class action by

merely calling it such. Pacific Fire Ins. Co. v. Reiner, D. C.

La., 45 F. Supp. 703. The burden of proof on this issue

was on the plaintiffs. Oppenheimer v. F. J. Young £ Co.,

D. C. N. Y., 3 F. R. D. 220. The plaintiffs failed to meet

this burden. In addition, a class action cannot be main

tained where the interests of the plaintiffs are antagonistic

to and not wholly compatible with the interests of those

whom they purport to represent. Flaherty v. McDonald,

D. 0. Cal., 178 F. Supp. 544; Redmond et al. v. Commerce

—R-1475—

Trust Co., C. C. A. 8th, 144 F. 2d 140; Brotherhood of Loco

motive Firemen and Enginemen v. Graham, et al., C. C. A.

Dist. of Columbia, 175 F. 2d 802; Kentucky Rome Mut. Life

Ins. Co. v. Duling, C. C. A. 6th, 190 F. 2d 797; Advertising

Specialty National Association v. Federal Trade Commis

sion, C. C. A. 1st, 238 F. 2d 108; and Troup v. McCart,

C. C. A. 5th, 238 F. 2d 289. The efforts of the plaintiffs to

bring white and colored freedom riders within the class

represented make it clear that this is not a proper class

action. Bailey v. Patterson,----- IT. S .------ , 7 L. ed. 2d 512.

3. The three plaintiffs are entitled to an adjudication of

their personal claims of right to unsegregated transporta

tion service by a declaratory judgment herein.

4. It is mandatory upon this Court to declare the Mis

sissippi segregation statutes and City ordinance attacked

in this case to be unconstitutional and void as violative of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. Bailey v. Patterson, ----- - U. S. ——, 7 L.

Ed. 2d 512.

6a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Declaratory Judgment

5. Under the facts of this case, the plaintiffs are not now-

entitled to injunctive relief. In so holding, this Court is

seeking to observe a vital and fundamental policy which for

m a ny years has been pronounced and followed by the

United States Supreme Court and by other Federal Courts

to the effect that Federal Courts of equity shall conform to

clearly defined Congressional policy by refusing to inter

fere with or embarrass threatened prosecution in State

Courts except in those exceptional cases which call for

—R-1476—

interposition of a Court of equity to prevent irreparable

injury which is clear and imminent. The issuance of a writ

of injunction by a Federal Court sitting in equity is an

extraordinary remedy. Bailey v. Patterson (on motion for

stay injunction pending appeal), 368 U. S. 346. Injunctive

relief will never be granted where the parties seeking same

have adequate remedies at law. Douglas v. City of Jean

nette, 319 U. S. 157, 87 L. Ed. 1324; Cobb v. City of Malden,

C. C. A. 1st, 202 F. 2d 701; Brown v. Board of Trustees,

U. S. C. A. 5th, 187 F. 2d 20; and State of Mo. ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 83 L. Ed 208. It is discretionary

with the Court as to whether it will enjoin enforcement of

an unconstitutional statute, and it will not do so in the ab

sence of a strong showing that the plaintiffs will suffer

immediate and irreparable injury in the absence of injunc

tive relief. Kingsley International Pictures Corp. v. City

of Providence, 166 F. Supp. 456. The Court will not enjoin

enforcement of an unconstitutional statute in the absence

of evidence that said statute is being enforced. Poe v. Ull-

man, 367 U. S. 497, 6 L. Ed. 2d 989. In Bailey v. Patterson,

-----U. S .------ , 7 L. Ed. 2d 512, the Supreme Court of the

United States correctly held that plaintiffs were not entitled

7a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Declaratory Judgment

to enjoin the criminal prosecutions of the freedom riders,

and said:

“Appellants lack standing to enjoin criminal prosecu

tions under Mississippi’s breach of peace statutes, since

they do not allege that they have been prosecuted or

threatened with prosecution under them.”

—E-1477—

6. The desire to obtain a sweeping injunction cannot be

substituted for compliance with the general rule that the

plaintiffs must present facts sufficient to show that their

individual needs require injunctive relief. Bailey v. Patter

son, -----U. S .------ , 7 L. Ed. 2d 512; McCabe v. Atchison

T. <& 8. F. By. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 59 L. Ed. 169; Brown v.

Board of Trustees, U. S. C. A. 5th, 187 F. 2d 20; and Kansas

City, Mo., et al. v. Williams, et al., U. S. C. A. 8th, 205 F.

2d 47.

7. Although no injunctive relief should now be granted,

this Court should retain jurisdiction over this action and

each of the defendants for such further orders and relief

as may subsequently be appropriate.

This May 1st, 1962.

S. C. Mize

8a

—R-1478—

D e c l a r a t o r y J u d g m e n t

I t i s o r d e r e d , a d ju d g e d a n d d e c l a r e d as follows, to-wit:

(1) That this is not a proper class action, and no relief

may be granted other than that to which the plaintiffs are

personally entitled.

(2) That each of the three plaintiffs has a right to un

segregated transportation service from each of the carrier

defendants.

(3) That the Mississippi segregation statutes and City

ordinance attacked in this case are unconstitutional and

void as violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States of America.

(4) That the plaintiffs are not now entitled to any in

junctive relief, but jurisdiction over this action and each of

the defendants is hereby retained for the entry of such

further orders and relief as may be subsequently appro

priate.

(5) That all Court costs incurred herein be and the same

are hereby taxed against the defendants.

O r d e r e d , a d ju d g e d a n d d e c l a r e d , this 1st day of May,

1962.

S. C. Mize

United States District Judge

Entered Jackson Division of the

Southern District of Mississippi

Order Book 1962, pages 20S through 216.

9a

—R-1572—

Supplem ental Findings o f Fact, Conclusions o f Law,

and Declaratory Judgment

(Title Omitted—Filed July 25,1962)

In its declaratory judgment previously entered herein,

this Court retained jurisdiction over this action and all of

the. parties hereto for the entry of such additional orders

and for the granting of such additional relief as may be

subsequently appropriate.

At the time of the entry of the declaratory judgment here

in, counsel for the plaintiffs submitted the form of a judg

ment which they suggested should be entered which granted

plaintiffs an immediate injunction against all defendants.

This was treated as a motion for judgment and was denied

for the reasons set out in full in this Court’s findings of

fact, conclusions of law and declaratory judgment in this

case.

—R-1573—

Prior to the entry of the declaratory judgment herein,

affidavits were filed in this action on behalf of Jackson City

Lines, Inc., the Greyhound Corporation and Continental

Southern Lines, Inc. to the effect that all signs indicating

use of any facility by any race had been removed from the

premises and buses of said defendants.

Subsequently, an affidavit was filed herein by the plain

tiff, Broadwater, to the effect that he had observed “white”'

and “colored” signs near the water fountains and rest

rooms of the Jackson Municipal Airport; that he had ob

served a sign on a Jackson City Lines Bus indicating that

white passengers were to take front seats and colored pas

sengers were to take rear seats; that two waiting rooms

were being maintained in the terminal of each carrier de

fendant, and that the City of Jackson maintained signs on

10a

Supplemental Findings of Fact, Conclusions of

Law, and Declaratory Judgment

the public sidewalks near the carrier terminals with desig

nations as to white and colored waiting rooms. In response,

affidavits were filed on behalf of the Jackson Municipal

Airport and the City of Jackson denying any enforcement

of the signs complained of and showing use of all terminal

facilities by members of all races without discrimination of

any kind. Jackson City Lines, Inc. filed an affidavit to the

effect that the failure to remove the sign on its buses was

an oversight and that same had been removed.

A hearing was afforded all parties to this proceeding, at

which counsel for plaintiffs requested and were granted

permission to file additional affidavits. Defendants were

given reasonable time within which to file responsive affi

davits. The Court ruled tentatively at that time that the

signs in the Jackson Municipal Airport should be removed

—-R-1574....

and that the evidence in the case in chief showed discrimi

nation on the part of Cicero Carr, the lessee of the Jackson

Municipal Airport Restaurant, in serving members of the

colored race and that said discrimination should be discon

tinued. This finding was supported by an affidavit of Der

rick A. Bell filed herein. Subsequently, an affidavit was filed

herein by Cicero Carr to the effect that the airport res

taurant was being converted to a standup-counter service

and that there would be no discrimination in serving mem

bers of the public in said restaurant because of race, creed

or color. An affidavit was filed on behalf of the Jackson

Municipal Airport Authority showing removal of all signs

from the water fountains and rest rooms in the airport.

An affidavit was filed herein by Boyce M. Smith that he

was refused service in a restaurant in the terminal of Con

tinental Southern Lines, Inc. in Meridian, Mississippi, by

11a

Supplemental Findings of Fact, Conclusions of

Law, and Declaratory Judgment

unidentified employees of said restaurant; that he was

asked to leave the restaurant by an unidentified police

officer of the City of Meridian, Mississippi.

An affidavit was filed herein by Mrs. Clarie Collins Har

vey to the effect that she was asked to leave a waiting room

of the Continental Southern Lines, Inc, terminal at Gulf

port, Mississippi, by unidentified police officers. Responsive

affidavits have been filed on behalf of Continental Southern

Lines, Inc. to the effect that none of its employees or repre

sentatives participated in or were responsible for any of

the acts complained of.

Subsequently, an affidavit was filed herein by David

Campbell to the effect that he was permitted to eat in a

room operated by Cicero Carr in the Jackson Municipal

—R-1575—

Airport exclusively for airport personnel. A responsive

affidavit was filed by Mrs. Myrtle Nelson, an employee of

Cicero Carr in said restaurant. It appears from both affi

davits that the occurrence arose out of a mutual misunder

standing as to the status of David Campbell and is not

pertinent to any issue of discrimination in this case.

S u p p l e m e n t a l F i n d in g s o f F a c t

The signs referring to race near the water fountains and

rest rooms of the Jackson Airport were improper but have

now been removed.

The sign on the bus of the Jackson City Lines complained

of was improper but has now been removed.

The defendant, Cicero Carr, has discriminated against

colored passengers in the restaurant operated by him in the

Jackson Municipal Airport, but such discrimination has

terminated.

12a

Supplemental Findings of Fact, Conclusions of

Law, and Declaratory Judgment

All facilities of all carrier defendants and of the Jackson

Municipal Airport Authority are now being used by mem

bers of all races without discrimination of any kind.

S u p p l e m e n t a l C o n c l u s io n s o p L a w

The defendant, Continental Southern Lines, Inc., did not

participate in and is not responsible for either the occur

rence at Meridian, Mississippi, or the occurrence at Gulf

port, Mississippi. Neither of said cities nor the persons

involved in said occurrences are parties to this action, and

said occurrences are not pertinent to the issues involved

herein.

—R-1576—

The Court finding that all matters of substance com

plained of have been corrected and that there will be no

re-occurrence of same, it is of the opinion that the plain

tiffs are not now entitled to injunctive relief, but that this

Court should retain jurisdiction over this action and each

of the defendants for such further orders and relief as may

subsequently be appropriate.

That all future complaints made herein by the plaintiffs,

or any of them, shall be by one or more supplemental com

plaints reciting the matters and facts complained of.

This July 23rd 1962

S. C. M iz e

Judge

13a