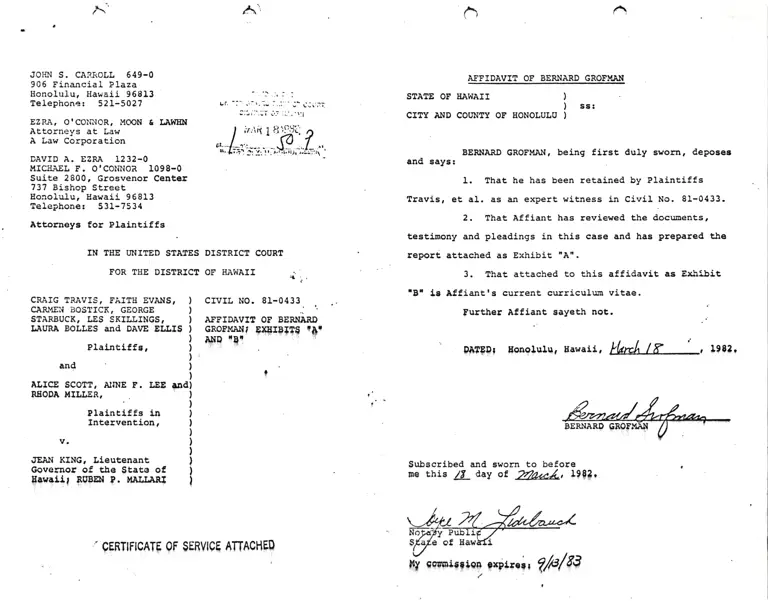

Affidavit of Bernard Grofman

Public Court Documents

March 18, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Affidavit of Bernard Grofman, 1982. d1c24cd8-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f0935077-8f61-4be0-8f84-533e473aeb60/affidavit-of-bernard-grofman. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

JOHN S. CAFTOLL 649-0

905 Einancial Plaza

Honolu1u, Hawaii 96813

Telephonez 32L-5027

EZRA, OTCONIIOR, MOON S IAWEN

At,torneys at Law

A Law Corporation

DAVID A. EZRA 1232-0

MICSiEL F. O'CONNOa 1098-0

Suite 2800, Grosvenor Center

737 Bishop Street

Eonolulu, Eawaii 96813

Telephone: 531-7534

AttorneyE for Plaintiffs

A. n

ATFIDAVIT OF BERNARD GROF!.TAIT

STATE OF tsAWAII )

)

CITY AIID COUNTY OE EONOLULU )

sgr

*/;1,1,:ff:1,-,

IN TBE UNITED STATES

FOR TUE DISTRICI

DISTRICT COURT

OF HAWAII {

AFAIDAVIS OE'BERNiRD

clgEYlY, Ex$rBI8g r0r

ANQ'Ei

BERIIARD GROF!{AI{, being fj.rst duly sworn, deposee

and says:

l. fhat he has been retained by Plaintiffs

Travis, et aI. as an expert witness i.n Civil No. 8l-0433.

2. That Affiant has reviewed the docr.uents,

testimony and pleadings in this case and hag prepared the

report attached as Exhibit "A".

3. That attached to this affidavit as E:&lbit

'B' ls Aff,iantrs current curriculum vitae.

Further Aff,lant sayeth not.

.

CRAIG TRAVIS, EAITB EVN{S,

CARIT{EN tsOSTTCK, GEORGE

STARBUCK, LES SKILIINGS,

IAURA BOLLES and DAI/E ELLIS

Plalntiff,e,

and

ALICE SCOTT, ArINE f . LEE .Dd

REODA MII.I.ER,

Plaint,lffs ln

Intervention,

v.

irEAlI KING, Lieutenant

@vernos of, tbe State ot

Enwalll RUBEII P. IIAI.IARI

DATFDT Eongluru, Bawall, l'boln * '--, 1983,

I

a

Subscrlbed and sworn to before

pe this /t day ot Ha -/, 19fl3,

OF $ERVI9E ATTACHED

Fy eemnfr?lon irplrctr ?/p/ra

'9ERT|FICATE

REPORT REGARDING THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF IIIE

SIATE LEGISIAIM REAPPOBTIONI'IENT PLAIIS PROPOSED By tHE

EAitArI BEAPPORIIONI{EN8 CO!{UISSTON, SEPIEI,IBER 28, t98l

-

TPROFESSIONAL BACKGROUND

Professor Bernard Grofman ls a nationally and

lnternatlonally known specialist 1n representation and re-

districtlng ts6ues, who is author of nearly a dozen articles

on this toptc over the last decade and senior editor (along

with Arned Ltjphart, Professor of Political Science and

former chalman, Department of Political Science, university

of California, San Diego, *ob"ra !{cKay, Director, Institute

for Judicial Adrnlnlst,ration, and Professor of, Lawr New York

Unlverstt,y; and lloward Scarrow, Professor of PoIi'tical

Science and forrrer chairman, DePartment of Polltical Science,

State Untversity of New. York at St,ony Brook) of a. special

issue of the PoIicv S.tudies Journal, (April l98l) on 'Reapgor-

tlonment Policyr and of a sympostun volume on Reoreser.rtation

and Redistrictinc Issueg, Bostons Lexington Books, APril 1982

forthcoming. The conference which generaced thqse edited

collectiona was Jointly funded by the National Science Foun-

dation, Program ln Polltica1 Science, and the Anerican Bar

Associatlon, on grants on whlch Professor Grofman iras the

Principal Investigator. Ee has also received other najor

funding fron the Natlonal Science Eoundation to study repre-

rontaElon lgeuesr 'ElecBotal Sy3tcol l{bat, Dlflsrcnc. Doca

Bernard Grofman, Ph.D.'

Professor of Political Science

School of, Soclal Sciencee

Universlty of Callfornla, Irvlnc

Iwlne, Callfornla 92717

llarctr 15, I 982

Exblblt 'A'

-t-

t tl.k.?' xsE soc 77-22a7a. 19?8-79, .nd rR.search on potltl- ootllllE

at G.ra:dandering' llSB SES 8l-0755a, t98l-82. In addr,tion

t. Ona far3on, one vole standarda ol toPul.llon Equ.Iltlt

c 13 lha prlnclpal org.nlrar of I Speclrl Scaslon on rtha

t. tntroductlon and Case Rcvle{

ollllcrl Cona.guancaa o! Elcctoral Lrwarr at th€ Inter- 8. aa{alt is Not ln CotrPllance t,lth 'O'nc Parson, Ona .

ltlon.l Pol,ltlcrl 5c1enc6 A3socl.tiont6 Erl6nnl.l rc€tlng, voter Slandardg

1o d. itanolro, lugus! 9-17, 1982, .nd la th. co-chrlr C, Imploprlely of Use o! Reglsler€d vol.r-Biaa-Ratho!

lhan census o! Cillzan PoPu}.tlon in 19E05 larall

e3lgnata ol lha lDarlcan Polltlcsl Sclence tssocl.tlorr a Redlslrlctlng

onfaronca Croui, on e€praa€nlatlon and Elactoral SystenB. Ee tt. Bias in Elactlon Outcom€s- and gsa o! ltultttretrbcr-- Dialr1cls as a llech.nt3o lor gnconatlt{tlonal Dllullon

'E alto salv.d .a t conaultan! !o the Ancrlcan Bar Assocla- o! [inorlly vollng Rlghtt

ionrt

'olEnrttre

oo Electlon La"n'l h's been lnvorvod ln a l' :nlEoductlon

onalrltattva EoI€ ln ravcrat raDEasertatlon or EadlstElctlnE Er Cas. Sevles

53u.3, inc:,udlng E.lom ot !h. lfr.sru County (U.v IoEh) C, Is .n Intent test Requtrad?

csisr.!ui., crncr,nn.lr, cb.!r.r r.!oa, .nr coisr.s.ronrr r il:$i::".:i: H::*:i?:1,3::i'l!iirillEEiii; *i

adlatalctlnE La Color.d,c. vota Dllulion in 8ax.it

l. volc Dllution

2. con6trlinls on potlElc.I cotp.tlllon Aggrivat.d

by ltultlrie[b.r Dlstricla

r t"' g::ili:1:iffnatttv o! n.ll.lt'!' tesr Lest't'tlv'

. t. Overvler

B' Ccn't'l'!rtto[ ot tDDloDEi'l' !tr'di"

-3-

raa

-2-

One Person, One vote Standards of Populatlon Equallty

A. Introduction

In Baker v. Carrr 369 U.s.186 (1962), the U. S. suPreme

Court afflrrned that Judicial redress could be souqht' Eo

eompel a state to reapportlon lts legislature ln accord wlth

nee cengug data. In a number Of subseguent cases, the court

addressed ltsel! to the lssue of voEer representatlon and the

constitutlonal accePtabtllty of various apportlonment and

votirig schenes. Most of those cases involved an expllcation

of the meaning of the l{th tunendment 'equal protection'

clause as tt applled to Congresslonal, state, and local

apportionment issues.

The notion of 'egual Protectlon' suggests varlous

crit,eria which we might wish any electoral schene to sat'lsfy.

At minimumr of course, rre would wish to guarantee each

citizen the right to exercise his vote.. Iloweverr once we

move beyond thls basic r19ht, the guestion of what'equa1

prot,ectlon'requtres (or rather, dlsallows) becomes a very

difflcult one. one answer ls that each tndlvldual who votes

should have hts vote count requallyr with that cast by each

other individual, 1.e., glven 'one persoor oll€ vote' we wish

'one vote, one valuet (Professor of Law, CarI Auerbachr 'The

Reapportlonnent RevoluElon' ln phtltp Kurland (Ed. ), The

suprene court Revleur chlcago: unlversl,ty of chlcago Pro8s,

1954, pp. 1-87). The dlfflculty comes ln operatlonallzing

such a criterion.

In @, 376 U.s. I (195{), a case which

struck down ag unconstitutlonal gross population disparities

among Georgia Congressional districts, the U. S. SuPreme

Court (376 U.S. at 8) held that'(O)ne man's vote. is to

be worth . . . as much as anotherrs.r In @!|5g$!g,

377 U.S. 533 (1954)r itDd its companion cases, the Court

extended this .One person, one vote' doctrine to state legis-

latures holdtng, tn diflerenE but equivalent, language (3?7

U.S. at 558), that'(A)n individualrs rlght to vote f,or state

leglslators lE unconstitutionally impaired when its weight, is

tn a subst,antlal fashion diluted when cornpared with votes of

citlzens living in other parts of the sEate.' In Aven' v'

ltidrand countv, 390 u.s. 474 (1968), the court extinded the

scope of its rullngs'down to the local level for units with

.general responsibitity.. Afl these cases inctuaea plurality

elections with slngle-menber districts in whlch there were

Iarge differences in the distrlct populat'lons.

In Revnolds v. Sins the Court asserted that Ehe'egual

protectlon, clause of the U. S. Constitution did not require

precise numerical equality but 'honest and good faith effort

to construct dlstricts . . . as nearly of equal populatlon as

1s practlcable.r The Revnolds decision acknouledged the

poss.ibillty of considerations other than strict populatlon

eguallBy cntertng lnco apporgiontrenE decietons.

-a\

-{- -5-

So long as the divergences from a strict population

standard are based on tegltimate considerations

incident to the effectuation of a ratlonal state

policy, some devlations from the egual population

principle are constitutionally permisslble (377 U.s.

ar 579).

Eosever, whlle Revnolds ldentlfled some areas where Etates

night rrlsh to act, e.9., 'to naintaln the lntegrtty of

various polltical subdivtsions, lnsofar as Posslble, and

provide for compact dlstricts of contiguous terrltoryr 1377

u,S. at 578), as Lawrence Tribe, Professor of Law at Harvard

Lan Sihool, notesl the Court was 'quick to ll.mit the range of

acceptable Justlfications for deviatlon from the egual

populatlon ruler (Tribe, Constitutional Law, 19782745-7471.

In subseguent declsiong the Court has reiterated the need for

very strlct populat,lon eguality 1n Congressional districting

decisions. ISee esp. Kirkpatrick v. Preisler; 394 U.S.'526

( I 959) , rhere the Court reJected as unconstit,utional a

distrlctlng rith an average devlatlon of .J{5 percent from

st,rict egua),ity. . In that case, the largest district exceeded

the ideal of, perfect distrlct populatlon equality by 2.43

percent, the snallest, distri,ct was below the ldeal by 1.7

percent for a 'range' of 4.13 percent.l While the Court has

allosed for somewhat greater flexibttlty ln state and local

districtsing decislons than ln Congresstonal dtstricting Isee

esp. Mahan v. Eowell, 410 U.S. 315 (1973)r tod Abate v.

$]!r 403 U.S. 182 (1971), where ranges of 15.4 percent and

ll,9 percang, respcctlv.ly, uere permittedl, !g@@II

(a vlrginia case) is the only state legislatlve case in uhich

the range of deviatlon permitted exceeded l0 percent.

In @@!g!! where a range in excess of l0 Percent

was permitted, rJustice Rehnquistrs majority opinion suggests

Ehat the majority Percelved circumstances of that case as a

quite unusual and possibly unigue situatlon, where the

vlrginia constltutlon vests local potitical subdivlslon

' boundaries with a leglslatlve significance which ls

substantlve as well as historlcal and which does not apply in

most statesr [P.8. Burker D. A. Epstein, and S. A. Alito,

.gederal case Law: state LegislaEive and congressional

Distrlctlng', ln A. l{olloch (Ed.), Reapport,ionnent: Lae' and

Technoloqv, Denver: National Councll of St'ate Legislatures,

June 1980, pp. l7-lql. Moreover !n 1981 when a three-Judge

U. S. District court consldered Virglniar s proPosed 1980

house redistricting, its range oE 26 Percent uas held to be

beyond the pernlssible .one-person, one vote' linits (cosner

v. Dalton, Civ. 81-O492OR), and the State legislature of

Virginla was ordered to redraw house lines. The nen plan has

an overall, population range of only 5.25 percent. (The PIan

provides for 95 single-member districts and one five-menber

district.in Norfolk. A severabllity clause has been included

ln the bllt for the flve seals in Norfolk in the event, that

Ebc iluettc€ DePartllent undeE the VoBlng BighBs Act preclear-

-6- -7-

n

ance proviEion) falls to accePt the multlmember district. )

In adoptlng t,his plan, the Assembly Parted with Vlrginia's

tradition of, not crosslng Potitical subdlvislon boundaries.

t{e might also note that a North Carollna state constltutlonal

provlslon, prohibiting crossing of county boundarles ln

Iegislative reapportionment, waE struck down by thE Justice

Department early ln December 1981.

'One Pe

Table I I show che population range results ln each of

Ehe states which had completed state legislatlve distrtctlng

by Sebruary 161 1982, for rhich I could obtain the data. It

is apparent fron this table that the ranges in both houses of

the Eawati leglslature, but especlally in the Senate are

grossly out of tlne with those ln other staEes. Slnce a U.

S. District Court tn l98t struck donn a populatlon range of

26 percent ln Virglnla the state 1n whlch the. U. S.

Supreme Court had hithertofore recognized the grealest need

for deviatlons fron strict population standards in St'ate

legislative dlstrlcting -- and the Eawall electoral ranges ln

the Senate exceed that Permttted Virglnla tn Mahan v. Howell,

and in the Eouse are wel,l tn excess of the 10t norn -- it

seems obvioue that Bawaitra leglslative redistrictlng

.1s

violatlve of 'one Person, one vot6' standards as Ehose have

been enunciated by th. g. S. Suprlnc Courtr .end should bc

declared unconeEttuBtonal.

Partlat List of st,ates !{hich have Completsd

Scate Legislative Redistricting

as of BebruarY 16, 1982

Alabama: plans Etill under

Voting Rtght, Act challenge

Alaska

Ar izona

Arkansas: ftrst plans rejected bY

U. S. Distrtct aE violatlve of one

person, one vot,e standard (DarIin

v. while)

Californiar plans under referendum

chal lenge

Colorado: challenges to reaPportion-

nent commlssion plans stlll pending

Connecticut: under court, challenge

Georgia (Department of Justice haE

inrerposed vorlng Rights Act

objectlon 2/221

llawai i

Illinois: plans affirmed, in U. S.

District Court and allowed to stand,

U. S. Supreme Court refused to hear

appeal

Indiana: suit pending challenging

use of nnds l}1!!3g$!Q!

Conference, et aI. v. Rober D. Orr)

Iowa

Klnrag | _

, -9-

Senate

Overal, I

Ranqe

?

. 9.77

5.0

8.75

{.0

?

3.92

9.99

tl3. I 8

t .59

House

OveraI I

Ranqe nnds

3.6

.98 No

9.99. Ies

5.0 Y€s (Boqse

only)

9.15 Yes (Bouse

only)

?N9

8.3,1 No

9.92 . Yes (gouse

only)

16.02. Yes

1.97 les (Eouse

only)

3. 87

0 .l t[7

6.5

{. ,l

0 .27

9.9

Yes (Bouse

onIY)

NO

NO

B. Bawail I s

-8-

labl.e I ( continued )

Senate llouse

Overall OveralI

Ranqe Ranqe

8.{ 9.55

? 9.3

-- 9.{3 --

8.1 8 9.70

7 .70 7.70

9.8{ 9.67

9.46

9.93

5 .50

3.73

?

I 2.49

r .56

s .23

10. 55

6.9

mmds

No

No

No

lee (SenatE

onIY)

Yes (Bouse

only)

st,aggered

terlog

Loul s i ana

t{issouri: not, lully conpleted

Nebraska (Untcaneral)

Nevada

Neu Jersey

Ne,, lteiico: pendtng challenge to 8n

apportionment based on 'ellglble'

voEers

North Carolina: new plans

introduced after Justtce DepamonE

objections to tlrst proposala

North Dakoca

Oklahona

oregon: pendlng court challenge

Pennsylvanla

south Dakota'(challenge to nnds

pending)

Tennessec

Utah

Vi rg lnla

Washington

a. Sources: 'Eeapportionment Infor:nation Updatel' a nonthly

joint publlcation of the Natlonal Conf,erence o( Stagc Leglr-

lature3 and Ehe Councll of sEaee Governnentg

the calculatlons of total range for Eauaii are from data

presented in the September 28, 1981, Report of lhe Eawaii

Reapportionment Comnisslon, pp. 36, 38. The range for the

llouse is 8.28 (the greatest negative deviatton--Kauai) plus

7.74 (the great,est posit,tve deviation--distrlct 23 on Oahu) -

I 6.02. The range f or t,he Senat,e ls 8.30 ( the greatest nega-

tlve deviaEion--Oahu, dlst,rict 6) plus 3tl .88 (the great,est

Posl!lve devlation--Kauai) . {3.18.

The Reapportionment Commission suggests that the data

from House and Senate should be combined, ind presents a

Eable (p. 38a) which purportedly reflects t,his calculation.

The data ln the t,able ls supposed to buttress assertions that

basic lsland underrepresentatlon in one House of the Eawaii

leglslature ls compensated for by comparable overrepresenta-

tion ln the other house. Sowever, the method of calculation

ln this tabl,e is mistaken, even lhough t,his method is used by

a U.S. State District Court ln Burns v. Gill, 316 F. Supp

1235 at 1297 (1970i, since state senators and stat,e represen-

tativeE are weighted equal.Iy. Appropriat,e calculations which

do not nix apples and oranges (see Reapportionnent Corurission

RePort Tables, p.35, p.38) show that Easal1 is over-

represented in both Bouse and Senate seats (-3.90 percent

deviation f,ron statewide average for the Senate and a -2.30

P€rcant dcvlatlon frou the stat,ewldo average for the Hous€) i

9.65 Yes

9.93 Ies

10.98 No

5.3{ No

,?

NO

t 2.49 Yes

3.1,1 No

7.8 No

5.2{ Yes

6.9 yes ( Ilouse

only)

-10-

- ll -

'rfriie Kauairs relatlvely sllght (8.28 percent) overrepresen-

tation at the Bouse level does not comPensate for its gross

underrepresentatlon at the Senate level (34.88 percent,).

SiniIarly, }{au1r9 6.1 average percent overrePresenEation ln

ilouse seats does not compensate for lts 15.07 pereent average

underrepresenEation in the Senate. Analogous, though lese

dranatic, resul.ts obtain for Oahu.

. In drawlng lts legisl,at,lve naps the Eawail Reapportion-

:Bent Comrnission used registered voters rather than census

population or (estlmated) citizen population as lts basls for

assessing populatlon eguality acrosE distrlcts. As the U. S.

Supreme Court nade clear in @, 38tl U.S. 73

at 90-93 (1955), Eawalirs reglstered voters basls, depending

in part upon political actlvtty and chance factors 1s not

Itself a permisslble population baser but may be used so lonq

as it oroduces a distributlon of leqislators not siqnifi-

cantlv different from .that whlch would result from use of a

oer:uissible populatlon base. Such pernissible bases would

f,or Hawalt either be census populatlon or cittzen populatlon

with the latter preferred (Burns v. Richardson, 38,1 u.S. 73

at, 93-95). while a registered voter standard was accePted on

an inBeriu baslg tn 1966, ghac wa8 so glX because tha U. S.

Dtst,rlct @uEt conclud€d that u3. ol rcgtsEeE.al votor

standard substantially approximated that nbich would have

occurred had state citizen population been the guide. In the

Suprene Court's own words (at 93 emphasis ours),'In view of

these consideratlons, we hold that the Present aPPortionment

satisfies the Egual Protection Clause gla because on this

record it raE found t,o have produced a distribution of

Ieglslators not substantially different from that nbich eould

have resulted from the use of a permissible population base.'

The 1981 Hawall Reapportionnent Comrnission did not seek

to deternine a'citizen population estlmater' lnstead they

generated an estimate of eliglble civilian voters and assert

(p. 19 of their September 28, 1981 report) that, while the

senate reapportionments would have been unchanged .had an

eliglble cttizen base rather than a registered voter base

been used, the Eouse aPPortionnenEs would have changed, but

these changes are labeled as 'a slight dtfference 'in the

dlstribution' 1p. l9). '

There are two key problens here. Pirst, as lnspection.of

Eheir own table (bottom of p. l9) shousl use of an estimated

eligible voter (civlllan population) standard rather than a

reglstered voters basis, would have affected 5 of the 5t

seats; roughly l2t of all the seats. Horeover, the rePresen-

tatlon of Maui nould have decreased 20t (fron 5 to it), the

representaglon of Kaual would have decraased 33.3t (fron 3 to

2) .nd tho rcarecentatlon o! oahu could have lncreased

moroorietv of Use of Reqistered Voter

st rr. ct 1n

-72- - t3 -

roughly 5t from 3? to 39. The descriptlon of these changes

by the Reapportion,nent Commission as a'slight dlfference ln

the distribution' ls clearly erroneous. Thus, 1f eligible

voters 1g taken to be a permlssible populatlon basls, then

the use by the Bawali Reapportionment Corunlssion of regls-

te(ed voters as a surrogate for a permissible populallon

basis fallE to meet the substantial concordance guidelines of

Burns v. Rlchardsonr lnd should be struck down as unconstltu-

tional. (Of course, the same basis of assessment for aPPor-

tionment must be used for both houses of a state legialature.

Bence, lt would be trnproper to use a registered voters basis

for the Senate and a dlfterent, nore eul,table, basls for the

Eouse. )

Second, lt ls far fron clear that ellgible voters (espe-

ciaIIy as thls basis tras estinated by the Reapportlonment

Commission, with lts peculiar treatment, of Armed Eorces Per-

sonnel) is a perinissible populat,ion basts under t,he Burns

v. Richardson guldeltnesr since nlnorlty population may have

a different age mix and thus be dlscrlminated against 1f only

.potential voters and not aI1 citizens are counted. If e1igl-

ble voters ls held to not be a permlEsible populatlon basis,

tben the cornmission has failed to dernonstrate concordance of

registered v6ter apportlonnents wtth those of a permissible

population basig, in violaEton o! Ehe Burns v. Richardson

requlreneng that they do 8o. thugr ln thls case, Eoor use of

a registered voter basis for apportionnent, muet be declared

unconsti t,utional.

llhtle Hawatl has distinctive charactertstlcs which sutr

port use of ciLizen resident basisl use of a reglstered voter

basis, when 1t glves results different from a permissible

apportionment basls, has the conseguence of denying full

represenEation to eEhnic minoritles (and other ninorities,

e.g. the aged) whose voter registration is lorr. this is.

constitutionally impermlssible, as welI as a vi,olation of

uinority rights under the voting Rights ect in the section of

the state which lE covered by that Act.

Andrew Masonrs study "Oahu Legislative Districts, 1981,

Analysis of Reapportionment Plan of the 1981 ReaPPorEionnrent

Commisslon of llawall [dated January 29, 1982 -- Defendant's

Exhibit 1 (Mason) I makes clear t,haE if perrnissible population

basls is defined on a' civilian basis excluding aII military

and their dipendents, thenr under the most ionservative

estlnates possible of malapportionment, 'It 1s Iikely that

ten of oahurs 20 disErict legislatlve districts dlffer from

each other by 20t or nore' (Page following Table l, no Page

nunber). These devtationsl comlng wlthin a single island,

are far ln excess of nhat 1s congt,it,utionally penaissible

under u.s. one person, one vote standards. t{ason al,so

calcrilates the estlnated devlatlone of Oahurs dlstricts fron

ldeal (equal rePBasenEatton Per populacion) slze tl se take

- l{ - -t5-

I.

the pernissible populatlon basis to be all civilians plus 15t

of the military and thelr dependents. Again, his conclusion

1s that 'it 1s likely that ten of, oahurE 20 legislatlve

districts dlffer fron each other by at least 20tr. The exact

ligures whlch underlle thege calculattons are specifled by

l{ason ln hlg Table l.

Bias in Electlon Outcomes and Use of Multlnember DtstrictE a

Mechanism for unconstitutlonal Dilution of Vottng Rights

A. Introduction

At, the aggregate level, for partlsan electlons, l, along

with a number of, other poliElcal science experts on redls-

tricting (e.9., Richard Niemi, Chairman of the Polltical

Science Department, Untversity of Rochesteri and Charles

Backstrom, Professor of Political Science, Untversity of

l.linnesota) belleve that a major goal of any districtlng

system is that i,t not be biased against any one or t,he other

of our two maJor partles. This criterion has been termed

'neut,rality'by R. Nleni and J. Deegan in their 1978 article

in the American Political Science Review on the nature of

redistrictlng. iy neutrality rre mean that both parties

should have to poll approxlmately the same proportlon of the

votes in order to sin a gtven proportion of the seats. Note

thats the trajority rule prlnctple ls subsumed ln the prlnciple

of neutrallty. Any tuo-party systen rrhich sattsfles neutra-

Itcy vttl, necesgarlly givc a votlng naJortty at leaeE a bare

najorlty of legislative seats. why should one Party have to

poll 55t of the state vote in order to win a majority of the

Iegislature, while the other party has to pol1 onlyl saY,

{8t? Why should a party be denied najority control of the

legislature if it polls a maJorlty of the vote? Anyone,

or any group, whlch designs a districting systen which

achieves these results -- €v€n lf the system is the product

oE well intentioned, blindfolded nonpartisans -- has designed

a system which has achieved the very opposlte of falr and

effective representation.

The late Robert Dixon, the leading U.S. expert on realF

portlonment,, argued, and I agree, lhac ue should avoid A

districting process which can be characterized by either one

of two extremes--the extreme of partisan lust or Ehe extreme

of leoislative maps dragn bv blindfolded cartoqraohers. (See

Dixonr s posthunously. published essay in Grofman, et, a1. ,

1982.) Rath.er, we should see the districtlng Process as one

in which we try to realize certain articulaced values, recog-

nizing that some of these values are nutually incomPatible in

uhole or in part, and that tradeoffs are reguired. (See

especiallyr Nieni and Deeganr l9?8.) There are no 'neutral'

choices among the great variety of available redistrictors

options. rWhether the lineE are drawn by a ninth-grade

civlcs clasE, a board of Ph.D.rs or a comPuter, every llne on

. atP allgns partisans and tnteresE blocs ln a ParBlcular

- t5 -

-17-

UIY,

are

nn

' and electlon results wtll vary according to whlch lines

chosen.

While 'partisan lustr ia clearly lnpermissible, g!g!g

consideratlon of the probable partisan (and also racial,/

1 inguistic) inrplications of alternatlve dist,rictlng schemes

1s, in tny view, desirable. Of course, drawing the line

between permisslble and lmpermissible'politlcal' considera-

Eions in the districting process is not easy. But we should

note that the Supreme Court has clearly lndicated in Gaffnev

v. Curmninqs that taking lnto account the expected partisan

'impact, of a dlstrlctlng scheme as one of the factors ln chooE-

ing among alcernative schemes 1s not prohiblted, and indeed,

in lhe case of impacc on racial/li,nguistic rePresentatlonr

anticipation of probable conseguences for ninority rePresenta-

tion has been held to be necessary for Jurlsdictlone covbred

by the voting Rights Act.

Moreover, in tlawail, the provtsion of the Bawail Constilu-

tion, Article VIr'section 5, No. 2 requirlng thaE no dlstrlct

be drawn so aE to unduly favor a person or polltical factlon

implies, tt, seens to.'me, that the Reapportionment, Conmisston

and this court nust concern themselves wit,h the antlctpated

conseguencea of the proposed redistricting proposals, lest

inadvert,ent undue discrirninatton agalnst minorlties (esPecial-

1y gartisan ninortties) occur, especially since such discrini-

natlon is oade nore llkely by use of oulEl-aenber dlgtrtcts.

As I read the report of the Bawaii ReaPportionment Comnission,

it does not seem to me thaE the corunission Paid adeguate

attention to the probabte conseguences of lls redistricting

proposals for politlcal party represenEation. I In Particu-

Iar, in Oahu, t,he decislon implicitly ratifled by the Comnis-

sion when it adopted a scheme which reduced expected Dernocrat-

lc ltouse representatiOn by one and expected Republican Eouse

representation by on€1 1{8s completely arbitrary and rested on

no analysis whatsoever of changing patterns of partisan suEF

port. This decision also falled to recognize the unequal and

dlscrimlnatory lmpact a one seat reduction tdlll have on the

much smaller representation basts of the Party wlth feser

representat lves.

B. The constitutionality of t{u}tiple-Hember Elections: case

Apportlonment echefies at the staE,e and local levEl often

make use of multlmenber districts, the Polar typ'5 of nhich

ls, of course, the at-Iarge election. Such plans tyPically

allocate the nunber of rePresentatives Eo a dlstrict tn

dlrect proportton to that districtrs populaElon. In the

lAfternatlvelyr it may be the case that majority of th9

Commissionr s- members trere aware of the probable inpact of

t,heir proposals on Republican rePres-entatio-n - in oahu and

Democralii representation in Hawaii and intended those conse-

quences. t im not in a positlon to directly evaluate the

issue of the varloue comnisston nenberr s lnteng. It ls the

ef lects o! ghe CouigsLonr s ProPoeals cith which I aE

concorned. !

\

- l8 - -19-

aftermath of the suPreme Courtr E entrance into the 'polltical

Eicket' of reapportionmen!, the constitutionality of multi-

nember districts has been challenged on several grounds.

Firstr and most lmportantlyl multlnember districts often

act so as to subnerge political (or other) minorities. The

'winnetr-take-all' character of t,he typical election gcheme

create8 the strong possibility that, a specific naJority will

elect atl the rePresentatives fron a multlmember dlEtrictl

rrhereas the outvoted minorlt,y mlgtrt have been able to elect

sone representatives if t,he multimember district had been

broken donn lnto several slngle-menber diEtrictsr especially

if nlnorlty strength le geographlcally concentrated. Two

probable consequences of such submergenee are reduced turnout

anong voters in the (partisan) ninorityl and even more

inportantlyT reduced competitlveness of the pollttcal

process. (Eor denonstraElon of how thls latter phenomena

nanifests ltself in Bawallr see Sectlon II-D below.)

A second (and closely related) challenge against multt-

nember dlstrlcts ls based on the propensity of rePresenta-

tives from such districts to act as a bloc. Chosen from the

same constlt,uency, alrrost certalnly o€ the same party, the

identlty of interests among such representatlves could be

expected to be greacer than those choEen from dlstinct dis-

trictlr and thue they aight noc tully uirror the vierrs ol all

r\

the citizens in the dlstrict (espectally those ln the overall

votlng mi.norlty) .

A third (and related) problen wtth multimenber districts

ls lhat they often lead to the electlon of rePresentatlves

who are not broadly geographically rePresentalive of Ehe area

which they are supposed to rePresent. Frequentfy, in uulti-

member districts, many or all of the rePresentatives sill

reside wlthin a narrob, geographic area, unless lhere ls

rule reguirtng geographic designated represent,atives. (Eor

evidence which clearly substanEiateg thls argument as tt

applies to Eawall, see DePositlon No. 2. l{arch 15, 1982, by

Reapportlonment Connission member James ltaIlr and Exhibit

t2O.) We might note that, unlike Eawaii, seven states have

designaEed seat provisions for their multimember districts,

so. as to lnsure that rePresentatives come from each najor

geographic area within'the larger districE.

A fourth argument against nultimember districts is that

the tie between a representaclve and his constituency is

weakened when a voter d6es nog have a single rePresentative

to regard as 'his own.' Sunrey data for llawaii directly

verifylng this argunent are found ln Exhibit 126 1pp. 2-3) to

James sai:.tE second Deposltlon, March 15, 1982- The exhibit

reflects evidence conpiled by a Denocratic State Senator.

(Algo sco Jerrell, 1982, forthcorolngT lor further evidentiary

-20- -21 -

A n

support of thls argument, based on Eurveys of state 1e91s1a-

tors from states other than tlawail.)

A fifth argument against multimember districts ts that'

they signlficanEly lncrease the cost of campaigning by re-

quirlng canpaigning among a much larger electorate. This

will often work to dlscourage minortty candldates. (See

Jewellr lgS2r.forthcoming, for data bearing on lhis point

from a nunber of states.) Data from Eawaiian sIn91e and

multlmernber' electlong, whlch substantiites this argunent

against, multiroenber districts, ts found in lhe transcripts of

testimony taken by the llawaii ReapporEionnenE Commission (see

e.9. remarks by Representative Toguchl) i and a comPlete body

of evidence for Earrail legislatlve electlon drawn from actual

campaign expendlture records, is found in Exhlblt t27 ln

Deposltion No. 2, t{arch 15, 1982, by Janes HaIlr' a

Reapportionment Conunission member. This data suPPorts the

basic polnt that multimenber campalgns are considerably more

costly than those for elngle rnember districts and thug

nultimember distrlcts will act to discourage candidates,

especially less wealthy oo€s1 from runnlng for office. I

have tabulated the data ln Exhiblt 27 deating with campalgn

costs lor winners of the 1980 general elections for the

Eawai,i Eouse. Ihe data came fron the llawali staEe campalgn

Spendlng Conolsslon' In 1980, Bhe nedlan canPalgn expendl-

ture ln Ehe general elecElon lor rePresengattvee electcd fEoE

f)

single-member districts uas S8r989; while the nedian campaign

expenditure in the general electlon for representatives

elected from multimember districts was between Sll,473 and

S11r749. Thus, in 1980, nultimember campaignE sere roughly

27t more costly than single-menber campaignsl and Ehis corr

parison actually understates the difference in campaign costs

between slngle-member and multirnember Eaces, since a greater

proportion of the multimember campaigns were uncontested or

not fully contested, Ieaving candidates in turn littIe incen-

tive to engage ln campaign expenditures. I toight also note

that in Exhiblt 25r Senator Carpenter Presents data on 197{

and 1976 campalgns which shot, thal (for the winners) nulti-

nember campalgns in those years nere 50t Bore exPensive than

single-member canpaigns.

A sixth accusatlon agalnst multimember distrlcts is based

on a mathematlcal argument advanced by ,John Banzhaf (1955)

which shows that, resldent,s of smaller districts .t" being

denied equal representation because resldents 1n the larger

dlstrlcts who are electing rePresentatlves proportional to

their numbers have a more than proportlonate chance of af-

fecting election outcomes. (This issue and the rlathematics

underlying this argument are discussed at length in Grofnan

and Scarrow, 'l 98'l , and Grofnan t 981b. )

None of these argunents were menEloned tn the ftrst o!

Ehe posE-EgESI caEea challenglng nulElnenber districts,

-23--22-

Portson v. Dorsev, 379 U.S. 433 (1965). Rather, in t,hat

case, the complaint was that voters tn the Georgia legisla-

turets single-member districts could elect thelr own rePre-.

sentatlvesi whlle voters, in the multlmember dtstricts (who

elected representatives at large but with the candidates

required to be residenEs of a subdistrict, 'dith each subdis-

trict allocated exactly only one rePresentative) rrere, 1t was

proposedl being denied thelr own representativer since voters

from outside the subdlstrict helPed to choose the subdls-

trict's rePresentatlve. rThe Court upheld Georgiars dls-

tricting system, concluding that voters ln multirnenber dis-

t,ricEs did indeed elect their orrn rePresenEatives the

representatives of the 99, rather than of t,he subdistrlct

ln rhich they happened to reslder (lrlber 197827521 emphasls

ours)

In Fortsonr 3Tg U.S.,t33, the U. S. Supreme Court held

(as 1t had in Revnolds at 5771 that'egual protection does

not necessarily reguire format,lon of alI single-menber

districEs in a statet s legislative aPportionment scheme.'

the Court asserted in Fortson 0 379 U.S. at {39, (emPhasis

ourE) t,hat, 'the legislaEive choice of multinenber districts

ls subJect to constltutional challenge only uPon a showing

that the plan was deslqned to or would operate to minimize or

cancel out the voting strength of racial or political

grouPgr' a

come up on this issue, surqE !,_BiS!-e!0gon, 384 U.S. 7'l at 89

(1965), a case dealing with State legislatlve disEricting tn

Eawai i .

The challenge to a nultimember aPPortionment scheme in

the next major case tn thls area, Whitcomb v. Chavisr 403

U.S. 124 (19?l), rested on two gulte distinct bases. The

first tdas t,he assertion that the ttarion County district

'tllegally minimizes and cancels out the voEing power of a

cognlzable racial mlnorlty in Uarion Countyr ({03 U.s. at

144). this cl6irn was rejected by the Court on the grounds of

an lnadeguaEe showing aE to the facts. The second was the

claim (based on the argument in Eanzhafr 1965; see Lucas,

1974 and Grofman 1981b) that 'voting PoHer does not.vary

lnversely with the size of the dlstrtct and that to increase

legislattve seats ln proportion to lncreased population gives

undue votlng power to lhe voter tn the multimenber district

since he has more chances to deternine electlon out'comes than

does the voter in the single-menber district' (403 U.S. aB

I 441{5) . ThiE second argument uas also rejected by the

Supreme Court. However, ln Whitcomb the court, continued to

assert that the const,itutlonallty of multinenber districting

could be challenged on a case-by-case basis.

In llhite v. Reqester, 412 U.S. 766 (1973), the U. S.

Suprene Courc tound that nultloember districts, as designed

and oP€raEed ln Bexar County, Tera8r invldiouely excluded

l2s:

/,.1

-2t-

blacks and ltexican-Americans from political partlclpation, and

that single-member distri,cts t ere reguired to remedy the

eEfects on past and present discrimination against blacks and

i{e:lcanAmerlcans. In Whlte the Court lived uP to tts promise

ln g!!9! and &|Egq that a properly mounted challenqe to

multimenber districting, when suetained by an evidentlal baee

couldr ln factr succeed.

In aubsequent cases, some apportionments whlch make use of

at-large elections or multimenber districts have been struck

down as unconstit,utional by the federal courtsi but the courts

have r€lterated that mulEimember districts are not per E

unconstltutional. Eowever, the Supreme Court [ln Connors v.

{chnson' 402 u.s. 5eo (1971) and S!3!manv Me:!sl, 420 U.s. I

(l975)lhasindicatedapresumptionagainst.s9@

nultirnember district plans tn the absence of exigent ciicunt-

stances' (tribe 1978: 755, emphasis ours); whlle the voting

Rights Act has, since the early 1970s, been so consErued by

t,he Justlce Department as to virtually ban a Jurtsdiction

covered by the Act from replaclng sing1e-nember districts t lt,h

nultlmember ones (se€ Grofman, 1981a, for further details).

In state legislatures, multimenber districts are becornlng

less common as their nany disadvantageE colse t,o be reallzed.

Por eraruplel ln state lower (upPer) houses ln 1968, 65t ({5t)

used Eone uultinenber di6trict6, but by 1978, only {0t (26t)

dld so. (Bcrr7 and Dycl 19791 86-87). BY 1980, Eh. Perc€ng-

ages were further reduced to 38t for state lower houses and

22t for state upper houses. In 1981, the American Bar Associ-

ation adopted a resolution urging thaE pure single-menber

districtlng be adopted in both housee of alI state leg!sla-

tives. (This reEolution is included as an exhlbit to Jatres

Eall's March 15, 1982 DePosition.)

In remarks before the 1981 Reapportionment Cotttutission,

Mondayr July 6t 1981, Corunlssion Chairman Ruben P. !'lallari

addressed the lssue of the relative desirability of single-

member v. multimember districts. Be provides a long Para-

phrase of polnts made in an artlcle by Professor Joseph F.

zimmerman of the Graduate school of Public Affairs of the

state universlty of, New York in A).bany (National civic Review,

Vol. ?0, No.5 (Hay 1981), pp.255-259) purporting to show the

flaws in slngle-nembeE dtstricttng. I aur quite farniliar rrtt,h

Professor ZinnermanrE work and have read the cited artlcle as

well as other work (including some as yet unpubllshed re-

search) by Professor zimmerman. l{hil,e the paraghrases fron

the }Is article are accurate, the naterial is taken out of

context ln such a rray as to suggese Professor Zinnernan t,as

asserting that multiroenber diEtrlct plurality elections sere

free of'the defecBa engnerated lOr single-roenber dlsgrict

-26- -27-

plurality electlons. Actually, Professor Zimmermanrs chief

point ln thls article ls an argument on behalf of the alterna-

tive voter, a single member district scheme used ln

Australla, nhlch modlfles the usual single- menber district

electione to requlre voters to rank order alI candidates, and

requires a raajortcy rather than plurallty vote. with one

except,ton the alleged claim that multimenber districts

generate a'nlder'perspectlve as compared to a more local-

istic viewpoint for representatives from sin9le-member dis-

tricts (a point thri force of which ln ttawali ls vlttated by

the fact that, representat,lves from multimember dlstricts often

are concentrated ln a small geographlc part of the wider unlE

they represent, and llay thus be Iike1y to rePresent the

'local' concerns of their geographic area as agalnst the wider

vieus of t,he entlre dlstrict) -- each of the other points made

by Professor Zirunerman against, slngle-member plurality elec-

tlons in his NCR article applies with egual or greater force

to multimember plurality electiong. For examPle, a multi-

nember district plurality systen, even more than a elngle-

menber dlstricl syst'em 'disenfranchises citizens .to a large

extent, and also dilutes the voters' influence on a governlng

body ln direct relation to its increaslng size.r (ExcerPt

from zirunerman quote polnt b, 9.2, JuIy 6. l98l ninutes of

the Reapportionment Commission. ) Similarly, in a multimenber

plurality systelo even more than in a single-nember district

plurallly system, it may happen that 'In partisan elections,

the most poorly qualified candidate can defeat the best quali-

fied candidate of each of the smaller Party.' (ExcerPL fron

Zimmernan quote, Polnt c, p.3, July 6, l98l ninutes of the

ReapportionmenE commlsslon. ) Finally, in a mix of single and

a mul.timember pluraltty districtsT €v€B more so Ehan in a

straight single-member district system, 'resuits.... can be

deliberately dlstorted to tavor the controlling Party or grouP

(gerrymanderlng).' (ExcerPt from Zimherman quote, polnt d,

p. 3, JuIy 5, '1981 minutes of, Ehe Reapportionnent commission.)

whlIe it is certainly true, as l{r. t{al1arl Points out (cotr

rnission minutes, July 6, 1981, P. 3) that 'no systero has a

monopoly on aII the defects tn the electoral processr' as my

discussion above has I believe made clear, schemei involving

multimember dlstricts (and I might add, especially ones nhich

mlx single-menber and multlmember distrlcts of various sizesr

particularly when aggravated in their egregious inpact on

mlnority represencatlon by the use of staggered elections, as

in the Eawaii Senace), have both gs..@, and @

defects Ehan does einple atngle-oenbet disEricging done in a

lalr dnd neugral faehlon.

^

tlhe alt,ernaclve vote, often also known as the preferential

vote, is a speclal case of the Eare slngle transferable vote

electlon Eethod -- a scheae for proPorttonal rePresentation.

-28- -29-

/\

Three argumenEs tn favor of multimember districts given by

Ruben i{allarlr Commission Chairmanr in his January 7, 1982

deposltlon are also aL best only partly substanElated, esPe-

cially given Ehe .ctual way the Commission did its redistrict-

ing.

Pirstr whlle the use of multinember dtstrlcts to avoid

disruption of communlty lines ts reasonable, the Commisslon

actually used nultimember districts in ways whlch dlsrupted a

nunber of natural communiEies, as is made clear in the variouE

unanimous comnunlcations from the Island Advisory Counclls

(and in nlnority views of the Oahu Council representattves).

Por detailsr see varlous exhlblts to Eall Deposition No. 2,

l{arch 15, 1982.

Second, ur. Mallari said the CommisElon sought to avotd

the posslbility of lrrational dlstrlct Ilnes by using.multl-

member distrlct.s. Here againl t,his is a Perfectly reasonable

stance, in principle, but does not aPPear io have been fully

carried oug in practice -- as the strong complaints from the

varlous Island Advisory Counclls and other concerned citlzens,

rhlch we alluded to'above, make very clear.

Third, Hr. Mallarl said t,he ComnisElon used multlmember

distrlcts to protect agalnst vtolent population shifts. If a

large geographlc area ls unlformly belng subJect to an ln-(or

out-) ulgration ehlch would dramattcally change lts populatlon

baser gben ghe cllcct wtll be ag narked (ln teros of dsvlatlon

fron the ideat population Per rePresentative) regardless of

whether the area is divided up into slngle member districts or

ls one Iarge mul,timemer district. Multimember districts do

have an advantage when they atre used to combine areas nith

expected declining PoPulat,ton with areas of expected increas-

ing populatlon so as to yietd a district erhich will not

deviate much from expected statewide poPulatlon changes over

Ehe course of the next decade. However, as I read the Colr

misEion September 28, l98l Report, this rationale of cornbining

declining and growlng areas aPpears to aPPIy to onl'y a handful

of the nultimember districts created by the Comroission. The

Commisslon certainly did noc systematlcally seek to project

population trendE throughout the various preclncts ln Ehe

S t ate.

C. Is an Intent Test Required?

contrary to popular bellef,

qerrl11aqde! !y-l!E-Ehepg. Cartography ls not whaE deternines

a gerr)rmander. One can have a gerrymander rrith d istricts

which appear on sight to be htghly regular and fair district-

ing schenes which may appear to the eye Eo contain grossly

gerrlnnandered dtstricts. What defines a gerrymander is the

fact that some group or groups (e.9. r a given Polltical Party

or a given racial/Ilnguistic Aroup) is discrirainated aqainst

aorpared go one or nore other grouP8 ln that a greater nuaber

a

-30- - 3l -

n

of votes is needed for the former to achleve a given propor-

tion of legislative seats than 1s true for the latter, and

this blas ls not one which can be attributed soIely to the

dtlferlng degree of geographlc concentration among the grouPs.

In generalr tt is my view thaE, rrhen Ehe lmpact of a

districtlng scheme (or electlon system) can be projected (or

judged ln retrosPect) with a very high degree of certalnty,

schemes which can be shoen to be grossly discriminat,ory ln

Eheir impact on the rePresentation of cognlzable grouPs beyond

Hhat might be exPected by chance, should be struck down as

unconstitutional. t do not believe that schemes which canrt

be direcqly shown to have been lglggiggl}I gerrymandered can

therefore be made inviolable lo constitutlonal challenge.

In this context it, ls useful to conslder the Supreme

Courtrs comment ln the 1973 case of @ i{12

U.S. 735 at 752-753, emphasis added).

case which reached the u. S. Court of Appeals, Eifth Circuit,

wedge-shaped single-menber districts which cut up the black

populatlon so as to deprive then of majority control of any

district were rejected as discriminatory even though direct

discriminat,ory lntent lras not proved. SimilarIy, in anoEher

Eifth Circuit Court case, Nevitt v. Sides (1978), 571 E. 2d

aE 221r that, court held that a plan 'racially neutral at its

adoption. may be unconstltutional 1f lt furthers preexisting

discriminatlon or ts used to 'naintain' it.

It iE sometimes asserted that lhe l98O case, lrlobile v'

BoIden established direct proof of lntent as necessary to

invalidate any plan alleged to dllute the voting scrength of

a racial or part,lsan ninority. (This was the lnterPretation

I made in my own flrst reading of this case in 1981.) uore

careful reading and consultat,ion wlth other constituEional

experts had led me to be convinced thls is too slnPlistic a

reading of the complex, confused, nulti-oplnloned, and far

from definltive ruling in Mobile.

First, Mobile does not overturn earlier cases such as

White v. Reqester. All that, there ts a clear majority hold-

lng on in Mobil.e is that the criEeria for establishing the

unconstitutionality o! multimember districts enunciated by

the Bifth circuit in zinmer v. McKeithen are not sufficient.

Second, as Burke, Epsteln, and Alito (1980:29) Point ouB,

Moblle tnvolved a Coranlsslon tom of governnent utrich ningles

It may be suggest,ed that those who redistrict and

reapportion sfrould work with census, not political

data and achieve population eguality without,

regard for polit,ical impact. But this politically

mj.ndl.ess alprogch may fro-auce,

-wfret@

@rossly gerryrnande-d resurtsi and,

ln any eventr it, is mosE unlikely that the politi-

cal impact of such a plan would renain undis-

covered- by the time it rras proposed or adopted, E

shich event the results would be both known and,

I roight also note that in Kirksev v. Board of supervlsors

o! Elnd Countv; uississippt (197?)r 5{4 F.2d 139, a 197?

-32- -33-

leglslative and administratlve functton, and 'as a dlrect

precedent for multimember state leglslative dlstricts, the

Uobile case may wel,I be irrelevant."

lhlrd, ln Cltv of Rome, Georqia v. united States, 100 S

Ct. l5/t8 (1980), a case declded by Ehe supreme Court on the

same day as I@!I9,, a change of election system whlch

introduced runoffsr numbered posts, and staggered electlons

ras held to violate the Voting Rights Act even though no

lntent to discriminate was proved.

Eourth, in an earlier case dealing wi.th racial dlscrlmi-

'natlon, Villace of Arlinqton Heiqhts, 429 U.S. at 241-242,

the Supreme Court has endorsed what has been calIed the

'egreglous impact' doctrine. This ls the view that when the

inpact of a law has a sufficiently disproportlonate lmpact

on one group, that, egregioue tmpact may constttute piima

Eacle evidence for intentional discrlminat,ion.

Fifth, the Justlce Department ln an amicus brlef, to an

important, challenge to a multimember districting scheme now

pendlng ln the U. S. Supreme Court, Roqers v. Lodqe (SIip tto.

8O-l2OO, October l98b), has offered the doctrine, based on

that in Kirksevr that'where a planr though ltse1f neutral,

carriee fonrard int,entlonal and purposef u1 discrininatory

denial of accesa that ls already in effectr lt ls not

constltutional.' This 'remedy' doctrine holds t,hat present

tntant to dlscrinlnate need nog be proved wtrerc Aurposolul

and intentional discrlmination already exists which trould be

perpetuated into the fuEure by othemise'neut,ral' official

action.

FlnaIIyr and we believe most tmportantlyl as the Suprene

court asserted in Gaffnev at, 752-753, enphasis ours (see full

quote above), if a plan exhibits gross gerrlrmandering 'it is

most unlikely that Ehe.polit,ical impact of such a plan would

remain undiscovered by the time it, was proposed or ado-oted,

in which event the'results woufd be both known, and if not

chanqed, intended. r Thus, if Hawaii I s overreliance on

multi-mernber dlstricts can be shown lo constitute aad/or

PerPeEuate gross politlcal gerrynandering so aE to

effectively and significantly dilute the voting strength of

partisan minorities, then I believe that the supreme courtrs

ruling in Mobile provides no barriers to declaring such

egreglous gerr'mandering unconstltutional on lts faCi, since

suchegregiousgerrlrmanderingwouldprovideadeguateevidence

of lnEent. In the uordg of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 'Some

clrcumstantial evtdence is better than others, as when you

flnd a trout, in your milk.-

lhe discussion above refers to standards of egual

protection under the g:L constitution. Even if it were held

that proof of intent to discrininate was required under the

U.S. Constitution, the Bawati ConstiEuEion, Article IV,

sectlon 6r No. 2 provides that rNo dlstrlct sball be so drasn

an

-3{- -35-

as to unduly favor a Person or political factlon', and thus

establishes an reff,ects testi as sufficient under Hawaii

glggg law. Thusr lf it can be shown that whlch I belleve to

be the case (see Section II-D below), to wit, that the lmpact

of the ReaPPortlonment Commisslonrg proposed mix of eingle

and nultinenber distrlcts (of varlous sizes) will be to

unduly favor a partlcular political party comPared lrith whag

night be expected under single member distrlcts, then I

belleve that such disErlcts should be Etruck down as ln

violation of Article VI, Section 6, No. 2 of the Eawall

Constlt,ution, independent of any Judgments on the merit,s ot

Eederal'equal Prot,ectlont argunents.

In Burns v. Richardson, Ehe Court said (at 88) that 'the

demonstration that, a parEicular multimember qcheme effects an

invidlous result fiust apPear from evldence i'n the record.

that denonstration was not made here.' The Court speciflcal-

1y rejected conjecture as t,o the effects of a multlmember

district syst,em and demanded a speciflc evidentlary record.

until the presen! case, such an evidenttary record has never

been presented to a federal court in a natter lnvolving sub-

aergence of oartisan Dinorlties, although such documentatlon

bas been offcrcd (and ln Dany case8 .ccePted) ln naEters of

racial vote-riilution (see case revierr above). Thus, the

pending Iltigatlon challenglng the progosed flawai i State

legislatlve redistrictlng will ber as far as I an arrare, the

first case in which a Federal court has recelved a challenge

to the constitutionallt,y of a mixed single and nultimenber

district scheme based (at least in part) on @!g!!g as

to the effects of that Particular scheme on submergence of

partisan minorlty rlghts, and as co lhe claim of denial to

partisan minorltles of full access to the political system.

In testimony by James EalI (DePosition uo. 2, March 15,

1982) submitted to District Court by attorneys for Plaintiffs

Travis, et 61. r t{r. tlall, a menber of the Commission who

dissented from its ftnal rePort, specifies in considerable

detail the probable lmpact of the proposed multi-nerier

dlstrlctlngs in both Eouse and Senate on the representation

of Republican voters. Wbile, my orrn independent, analysis has

led me to beli'eve that, the use of multi-nenber districts will

substantially dilute Republican voting strengEh (by submerg-

lng Republlcan voters in multi-menber districts uhich are

predominantly Denocratlc) for llaui, Kauai (the llouse only)

and Oahul lhe linchpin of the argument for the egregious

lmpact of multl-menber distrlcts on minority representation

is, in ny vi6w, Oahu (espEcially the Bouse distrlcts) r since

the estl,mated effects on the other islands, though Present,

are o! a nuch les'ser nagnitude, because these islands have

n-

Mult imember

-35- -37-

,^f'\-

considerably fewer leglslative representatives than does

Oahu.

Using dat,a on the Carter-Reagan (and also Carter-Pord)

lac€r l,lr. EaIlr ln hls depoEitlon and accompanying exhlbitsr

identifles the areas of Republtcan votlng strength2 on Oahu

and denonstrates how that, strengt,h ls substantially submerged

ln the Comnlsslonr s proposed multimember plan, such that

probable Republlcan Senate representatlon on Oahu would be

reduced by two (from the seven anEicipated under the Commis-

sion plan as compared to t,he nine that could be anticipated

under the sort of slngle-menber distrl.ct plan whlch would not

subnerge Republlcan voting strength and which would satisfy

bot,h U.S. and tlawail Constttuttonal guideltnes) I while Repub-

lican llouse representatton on Oahu woul.d be reduced by as

nuch as five or slx (from the nlne anticlpated under the Com-

nisEion plan as compared to the 14 or 15 anticipated under the

sort of singLe-menber district plan which would not subnerge

Republican voting strength and which would also saEtsfy U.S.

2Using two-party vote share in Presidential races as a

basis for judging Republlcan,/Democratic strength in llawaii

seens guite reasonable, since t.he many uncontested (or not

fully contested) state legislative races in the multi-member

districts would reduce the apparent nagnituCe of Republican

voting strength, and party registration figures are well

known co be an unreliable guide to voters' partisan at,t,i-

tudes, especially with an ever lncreasing portion of the

electorat,e opt,ing for the label of independent, even though

actually leanlng Borc to ons party than anoEher.

and llawaii constitutional guidelines). Clearly, such sizeable

dilutions of minoriEy voting strenglh constitute egregious

gerrymandering, whether consciously intended or not.

lhe l3 official state maps of t,he preclnct boundaries for

Oahu (Ha1l l{arch 15, 1982 Deposition, Exhibits l8A-l8l{), have

been colored in by Ball to indicate vtsually areas of Repub-

lican and Democratlc st,rength (the deeper the blue, the more

Republlcan; the deeper the red, the more Democrat,ic). Hr.

HalI uses these maps to show the dilution of Republican voting

strength caused by multimenber districts in ttre previous dis-

trlctlng -- and also discusses how that discrimination trill be

prepetuated (and in some cases intensified) under the ReaP-

portlonment Commisslon plans which continue almost exclusive

use of multimember districts. In his r{arch 15, 1982 Deposi-

t lon ( pp. I 5-20 ) , l.tr. Ilall lndicates that there are s ix to

to seven concentrations'of Republican st,rength which are (and

'riIl be) submerged by DemocraEic vot,ing strength' in multi-

member dlstricts. Hence, a fair slngle-member district system

might be expected to increase Republican represencation from

the nine llouse seats anticipated under the Corunission plan

(Republicans now hold ten seats on Oahu) to perhaps as inany as

15 or 15. Certainly, ln r,y view, af ter revlewing all the roaps

(l8A-l8l{) and the voting returns, data from the 1980 Election

prepared by the office of the Lieutenant Governor any reason-

able (const,ltut,lonal under g.S. and Bawaii guldelines)

-38- -39-

single-nember districting would gain Republlcans an additional

five to seven itouse seats on oahu over what Ehey would achieve

under the Conmission'g proposed predorninantly multimenber plan

in which Republican strength is regularly subnerged by joining

it with areas of Democratic concentratlon. the proposed plan

unconstllutionally dllutes Republlcan voting Ecrength and 1s

biased in favor of DenocraEic votersr PerPetuatlng an already

existing dlscrininatlon caused by over-reliance on multimember

districts and the etfects of rault,lrnernber dlstricts on sub-

Eergence of minority vot,lng strength.

Let us now look at this multlmember submergence effect in

detail. 8or our flrst example, we may look at the sizeable

concentration of Republican voting strength in the boEtom left,

of tlap Exhlbit, l8A which ls divided between two multim.ember

districcs, the lTth and the l8th, nelther of whlch elected any

Republlcan represent,ative in 1980 because Republican strength

eas so thoroughly subnerged that no nepubllcan candldate even

chose to run ln either of theEe districts in 1980. (See

discussion in Eall Depositlon No. 2, March 15, 1982, p. 15' of

the ninority voting rights dilutlon effects of the Commisslon

proposed plan whlch will be simllar to that of the exlsting

g1an. )

Other exauples of the subnerged concentrations. of

Bepublican voters aro shocn ln uap Exhibtt 188. There is a

sizeable pocket of Republican voting strength in the uPPer

right hand corner, r.rhich is compleEly submerged ln lhe 3-

member l3th Eouse District, whlch in 1980 did not elect any

Republican representatlves. Similarly, the 2-member I {th

liouse Districtr whlch contains a reasonably sized bloc of

Republican voting strength (the Patch of blue 1n the lorrer

right part of the rnap) elected no Republican rePresentative in

1980. (See Eall DePosltlon uarch 15, 1982, pp. 15-17 for

discuEeion of the guite sinilar effects of the proposed new

plan. )

In my view, reasonable stngle-menber distrlcting for the

ilouse in the portion of oahu shown in l{aps l8A and l8B soufd

have galned the Republicans about three additional seats, lost

tn the proposed and present plans to submergence.

If we no'd turn to Ball's March 15, 1982 Deposition, uaP

Exhlbtt 18C, and conpare 1t rrith the proposed n"Y. linesr He

can see how the waialae-Kahala area (the blue and thus heavily

Republlcan area ln the botton left of the tnap) has been

grossly gerrymandered under the conmlssion's proposed Bouse

pIan. Under the old distrlctlng, this area r,as I'n Bouse

Distrlct 8, an overwhelmingly Republican area which elected

two Republlcan representatlves. Under the ne'r proposed lines,

it will be split four ways -- part of it to be retained in the

ne,,, Eighth Eouse Dlstrict, a district which wiLl now becone an

ovenrhelningly Bepubllean @, Part of, tts.

-'00- -{l-

n

Republican voting strength will be submerged by Democratlc

votes in new Eouse Dlstrict 9 (a mult,imember distrlct whlch

will almost certainly elect tuo Democrats), another Part of

its Republican votlng strengtit wll1 be submerged by Denocratlc

votes ln new Eouse Distrlct 10 (another multinember district

almost certain to efect two Democratic rePresentatives); and

the final snall portion of this district has had its Repub-

lican voting strength nerged with the already predomlnantly

Repub),iean votlng etrength of new Bouse District I 1 (a dlstrlct

which would in any case have elected two Republicans.) Thls

'treatment of Republican voting strength ln the l{aialae- Kaha1a

area is a ttextbook' example of how to combtne nconcenEration'

and 'dlspersal' gerrlnaandering technigues to dllute minorlty

voting representatlon. In District 8, two nember dlsErlct'

which had elected two Republlcans ts being reduced by' the

Commisston plans to a slngle member district which is over-

whelningly Republican (a 'concentration' gerrymander) -- thus

losing one Republican rePresenEative; while the lower portion

of the area is rnerged nith an already strongly Republican

district (ilouse Distrlct ll)r another rconcentration gerry-

nander; and another two pleces of Waialae-Kahala are submerged

tn predorninantly Democratlc nrultlmember dlstricts (a forn of

'dispersal' gerrynander). Al,I in alI, Republican vot,ing

st,rength clearly sufflclent to elect tto representatlves has

been 'nagtcally' reduced 60 as to yteld only one (not already

A

winnable) seat, the new single-member 8th. such a multiPlex

combination of multimenber district submergence of minority

strength (an especially pernicious form of dispersal gerry-

nandering) and concentratlon gerrymandering to further reduce

lhe seats winnable by the ParElsan minorityl ls clearly, in mY

view, violatlve of the llawaii Constitution, Article IV,

Section 5, No. 2, as well as a denial of the Sederal'equal

protectionr righls of minority voters. (8or further dis-

cussion of thls pointl see Ha}l'g March 15, 1982 DePosition,

p. 17. )

In l,tap Exhlblt l8J and l8K, if we look at the 20th Bouse

Distrlct, we see Republican strength (see HaP l8J) is present-

1y totally submerged by Denocratlc voters (see MaP l8K) so

that in 1980, no Republlcan candidate even contested t,he

mulEimember disErict. clearly, tf Ehe District uere reason-

ably divided lnto two .single-member districts, one of its

aeats would alirost certainly go to a Republican can6idate.

The commlsgionr s proposed nen liouse plan for t,his region

of Oahu makes a bad situation even $rorse. IE is pernicious in

its diluting effect on Republican votlng strength and in its

violation of the socio-econonic and t,erritorial inUeqrity of

Milllani (see MaP l8J). Previouslyr the considerable Repub-

lican strength ln titililani had been submerged by Denocratlc

votes'in old Bouse Dist,rict 20 (nhlch elected two Democrats in

l98O). Under Ehe nee planr Milllanl ls slnpl,y being disnen-

-{2- -{3-

^

r'!\

beredt One half of it si]l be ln new llouse District 20 and

one half in new House District 22, both heavlly Democratic

mult,imember districts. Thus, under t,he Commission plan,

Mi,lilanl's Republlcan voters are having thelr ability to elect

legislators of their choice t,oca1ly eliminated through the

subrnergence of t,heir votes vla a comblnatlon of multimember

districts and dispersal gerrymandering. Not surprisingry,

Ehis dismemberment, which has in my vlew no legitimaLe justi-

ftcation since alnost all of Mililani could easily be enconr

passed within a eingle-member district, was bitterly protested

by !{iltlanl residents. (See Ball DePosition March 15, 1982,

pp. t8-19 and attached exhibits for furt,her discussion of the

inpact of t,he Reapportlonment Comnlsslon plan on Mllllanl and

of, local opposition to that Plan. )

Finally, if, we look at the two-menber 21st Eouse District,

a large pocket of Republican strength (shown ln l{ap 18L) ls

again submerged by being combined with Democratic voting

st,rength (see Hap'18M). Indeed, no Republican even contested

t,he distrtct in 1980. (For discuss!.on of the simllar egre-

gious irnpact of the new Reapportionnent Corunisslon proposall

see the HalI Deposition uarch 15, 19821 pp. t9-20.)

2. Constraints on Political Conpetitlon

In my viewr one of the greatest risks ln use of a biParti-

san dlstrlcttng conrolsston, whose nenbers are often hlghly

pol,lt,lcat, oulng thelr aPpolnEr0ents 'to legislatlve and Party

r\

leaders, is that the districting that results silI be an

rincumbent preservation gerrrymanderr' i'e', one uhich seeks

to preserve incumbents of both parties and to drastically

reduce the nunber of potentially competitive districts. such

a gerrymander would violate our basic democrattc belief that,

as Niemi and Deegan (1978) put 1t, rSeats in a representative

body should change as vole totals changer' i.e., a legislature

should not be totally insulated from changing currents in

public opinion over Ehe course of the nexE d.ecade. Eanaii

already suffers from a situation ln whtch incumbents are

largely locked into office and do not face challenge from

candidates of the other rnajor Party. For example, during the

1980 elections, 5{t l9/141 of the Bawali, Senate seats'and 73t

134/46) of the minority House seat,s went, uncontested. Absence

of contested electlong was partlcularly prevalent among the

multimenber constltuencies. Of the 22 multimember districts

tn the Eouse ln 1980, only two of the 22 (9t) t ere fully

compet,ltive. Of the five single-member disericts in the

House, two were fulJ,y competitive (40t) r l.e. had candidates

of both parties equal in nunber to the seats at contest. In

the llawaii Senate elect,ions in 1980, only 201 of the five

contesCed multinenber districts Here fully competitive (one of

flve), while on the other hand, 50t of the two contested

(effectively) single-nenber senate dlstricts sere fully

coBpeciEive. lloreoverr in the 1980 Bouse eleceton, che

-{{- -{5-

t\

largest district (l,ittr 3 nemberE) had three Democrats and

only one Republican runnlng tor offlce, and all three Demo-

crats were elected.

Cleartyr nultimember districts reduce cornpetltion tn

Bawail ln two imPortant rrays. Most lrnportanclyl they make lt

far less Iikely that mlnorlty candidates will eeek officer

and secondly and retatedty, they make more llkely a clean

sweep by one political Party of all the seatE ln any multi-

oesrber districts. thls clean srreep occurred ln 1980 in 60t

13/51 ot the (effectlvely) multimember districts in the senate

and 77.5t 117/221 of the llouse nultimember distrlcEs. (See

Ball DeposiElon No. 2, March 15, 1982, and Exhibit ll9 thereto

for details on svreeps in legislative electlons in the 1970s.)

These barriers to political competltion, combtned wlth the

barriers to candidate ent,ry generated by the higher cost of

canpalgning for multlmember dlstrtcts mean that, as multl-

nenber distrlcts operate tn Eawal1, both voters and minority

candidates are belng denled effective accesE to partlclpatlon

in the polltical process, 1n vlolatlon of constttutlonally

protected rlghts.

lhe new dist,rlctlng proposals Eor the Eawaii ttouse and

Senate wi]l continue llawail's already dramatic problems with

absence ol poiltical competltlon, since nultinenber distrtcts

contlnue to overarhelraingly predoninate ln both the llouse and

ghe Senate. In thc 1980e, 96t o! ghe State senatoa8 and 88t

of the ilouse members will be elected frorn nultimember

districts. FurtherroEeT since the Hawaii districting maps in

both House and Senate have been drawn to make it likely that

all but a handful of lncumbentE can be reelected from their

previous constltuencies (or sllghtly changed or enlarged

verslons of sane) I lt ls likely that the problen of absence

of, competltion.will grow even worse in the 1980s than it, t,as

in the 1970s.

The clalmed Link between the use of multinenber districts

and reduced competit,iveness has been challenged by Dr. Ruben

Mallari, the Reapportionment Commission Chairman, in state-

ments made before Ehe cornmission JuIy 6, 1981 . Dr. l'{allari

(P. 9) asgerts .I suggest, t,o the Conmission that Ehe.conten.

tion t,hat multlmember districts allow party sweePs cannot

easlly be tested in Bawaii because of the failure of both

poIltical parties to field fuIl st,ates of candidates in t,he

Iegislative contests.' ltallarl Ehen goes on (remalrider of p.

{ ) to demonstrate the hlstorical lack of competitiveness t..-.-,

Eawall leglslative contestE throughout the 1970s. The nis-

Eake Dr. Mallart nakes is a conmon form of logical fallacy;

called ln sEatlEtica books the'fallacy of the hidden 3rd.

factor. t '

whlle tt ls true that lack of conPetltion fosters sueePs

(and vlc€ versa), @ Iack of comPetition and sweeps are

largely the direct 6r lndirect result of th€ preponderant use

a

-{6- -{7-

of multimember dlstrlcts which submerge minority voting

strength and have led ( and will continue E,o lead) ninority

candidates to choose not to run in multimember races tn which

they can expect to be unsuccessful, and when they do run ln

such racesr !o be ln faet more likely than not to be

unsuccessfull As noted above, in 1980 (and I belleve similar

resul,cs woul,d obtain for other el,ection years) , multimember

districts irere considerably less llkely Ehan slngle-menber

dlst,ricts to lnvolve fully contest,ed electlons. The

elimina!ion of nultl-member dlstrlcts and their replacement

iit,h slngle-menber distrlcts woul.d thus, almost, certalnly,

enhance political competltion in Hawail, as well as leading

to a Bore eguitable representatlon of a1l groups or factions

within the electorate. (See further'discusslon of these

points in renarks by Comrntssion nrember Janes 8a11, mlnutea of

t,he Reapporttonnent Comralssion, July 5, 1981 , p. 9 I and see

Exhibit t9 in gall Deposttlon No. 2, !,tarch 15, 1982.)

cannot be sustained by a proclaimed need to Preserve the

Basic Island Units intact. The Reapportionment Comnissionsr

plans already contaln districts which span more than one

lsland, and Hawaii constitut,ional provisions must give Hay to

the U.S. constiEutional guarantee of voter Protectioni

2t the Comrnission's proposed schemes of mixed single and

multimenber districts have generated egregious political

gerrymanders which unconstitutionally dilute the voting

strengEh of partisan political ninortties, generally (but not

exclusively) Republican voters, and wilI be likely to deny

representation to voters in portions of t,he Iarger multi-

nember districts because of the election of rePresentations

from a narrow geographic area within the larger district;

3) the proposed schemes of mixed singIe and multimenber

districts wiII act so as to elininate the possibility of

oeaningful political competition for state legislative posi-

tions in both the Bouse and the Senate and will redtice incen-

tives to voter turnout by effectlvely freezing Present poli-

tlcal incumbents in office;

The Unconst itutional 1ty

Redistricting

A. Overvien

of, Eawallre 1981 Legtslatlve

Bawallrs 1981 legislatlve redistrictlng should

dosn as unconstitutional because

1 ) populatton deviattons fron 'one peEson, one

grcsEly erceed constitutlonally p€ralsslble llnlte

be struck

vote' so

that they

4) absent proof of concordance

base, the use of a registered voter

tive apportionments ls tnpermlssible

@.

I belleve tha! it the court accepts

lying gg clngle one of Ebese charges,

sith a permissible vote

base for Eawaii legisla-

-- in clear viol.atton ot

the reasoning under-

thig uould be suffi-

-48- -{9-

la

cient reason to declare Bawaiirs 1981 Legislative redlstrict-

lng unconstitutional on Federal equal protection grounds.

!{oreover, the proposed plans appear to have a number of

other critical defects. For examplel it has been argued (see

e.g. Deposition No. 2, March 15, 1982 by James llall and

selected exhlbits thereto) that, the Commissionr s proposed

redlstrlctton schemes subnerge certain socio-economic aroup-'

ings 1n violation of the Bawail Constitution, Article IV,

Section 5. It has al,so been argued t,hat the proposed re-

districclng schemer at least for Oahu, for the Rouse, (where

bne Republlcan and one Democrat seat rdere "sacrificed'1 3