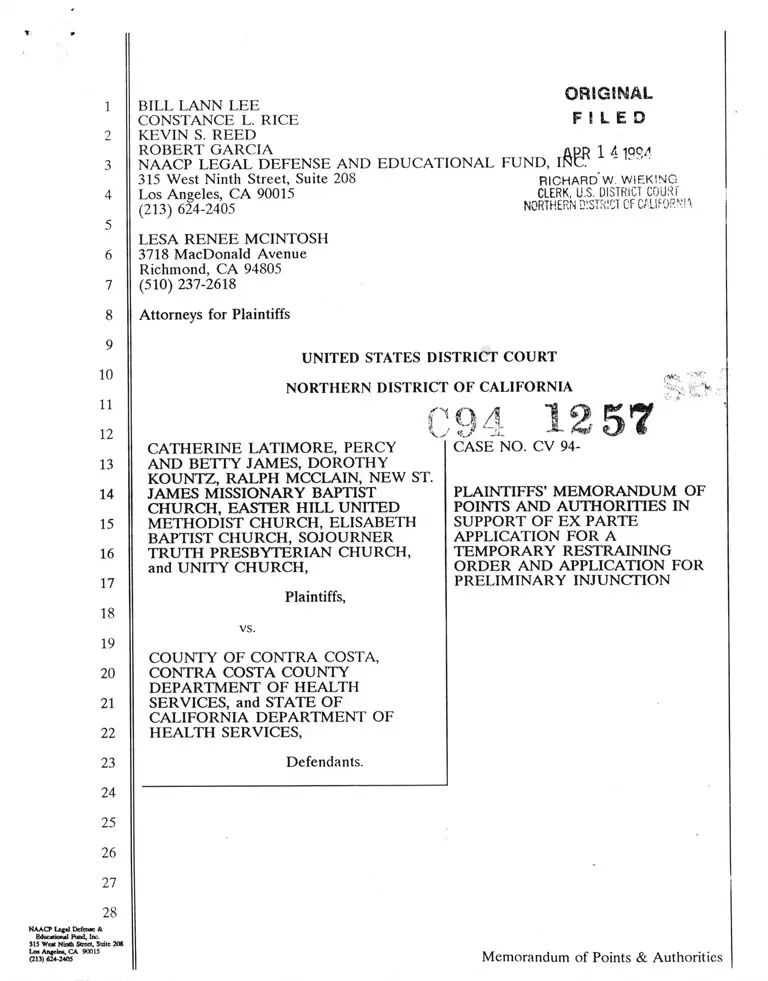

Latimore v. County of Contra Costa Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Ex Parte Application for a Temporary Restraining Order and Application for Preliminary Injunction

Public Court Documents

April 14, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Latimore v. County of Contra Costa Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Ex Parte Application for a Temporary Restraining Order and Application for Preliminary Injunction, 1994. e9c6f004-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f148d2c4-24cb-45ec-ac5a-b3621c9843f9/latimore-v-county-of-contra-costa-plaintiffs-memorandum-of-points-and-authorities-in-support-of-ex-parte-application-for-a-temporary-restraining-order-and-application-for-preliminary-injunction. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Sc

hritc 208

BILL LANN LEE

CONSTANCE L. RICE

KEVIN S. REED

ROBERT GARCIA

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

O R lG iM A L

F I L E D

1 4 1994

315 West Ninth Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

RICHARD W. W iE K I N G

CLERK, U.S. DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT Of CALIFORNIA

LESA RENEE MCINTOSH

3718 MacDonald Avenue

Richmond, CA 94805

(510) 237-2618

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

I

CATHERINE LATIMORE, PERCY

AND BETTY JAMES, DOROTHY

KOUNTZ, RALPH MCCLAIN, NEW ST.

JAMES MISSIONARY BAPTIST

CHURCH, EASTER HILL UNITED

METHODIST CHURCH, ELISABETH

BAPTIST CHURCH, SOJOURNER

TRUTH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH,

and UNITY CHURCH,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA,

CONTRA COSTA COUNTY

DEPARTM ENT OF HEALTH

SERVICES, and STATE OF

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH SERVICES,

Defendants.

- u .

CASE NO. CV 94-

PLAINTIFFS’ M EM ORANDUM OF

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN

SUPPORT OF EX PARTE

APPLICATION FOR A

TEMPORARY RESTRAINING

ORDER AND APPLICATION FOR

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

fc

irate 208

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1

II. STATEMENT .................................................................................................................... 3

A. Demographics........................................................................................................... 3

B. Public hospital services for the poor................................................................. 6

C. Contra Costa County Health Plan..................................................................... 8

D. Proposed Merrithew Replacement............................................................ 10

E. Proceedings............................................................................................................. 13

III. THE STANDARD FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTIVE R E L I E F ........... 13

IV. THE BALANCE OF HARDSHIPS TIPS SHARPLY IN PLAINTIFFS’

F A V O R .............................................................................................................................. 14

A. Harm to Plaintiff.................................................................................................. 14

1. Preconstruction and construction costs............................................. 14

2. Joint Community Hospital Proposal.................................................. 16

3. Adverse Health Risks to the Minority Poor.................................... 18

B. Absence of Harm to Defendants..................................................................... 19

C. Harm to the Public.............................................................................................. 19

V. PLAINTIFFS HAVE DEMONSTRATED A LIKELIHOOD OF

SUCCESS ON THE M E R IT S .................................................................................... 20

A. Disparate Impact Claim..................................................................................... 20

B. Purposeful Discrimination Claims................................................................... 22

VI. CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................. 25

Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

&

Suite 208

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Alexander v. Choate,

469 U.S. 287, 105 U.S. 712, 83 L. Ed. 2d 661

(1985) ................................................................................................................................ 21

Arlington Heights v. Metro Housing Corp,

429 U.S. 252, 97 S. Ct. 555, 50 L. Ed. 2d 450

(1977) ........................................................................................................................... 22, 23

Assoc, of Mexican American Educators v. State of

California,

836 F. Supp. 1534 (N.D. Cal. 1993) ........................................................................... 21

Cannon v. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. 677, 99 S. Ct. 1946, 60 L. Ed. 2d 560

(1979) ............................................................................................................................ 21

Gilder v. PGA Tour, Inc.,

936 F.2d 417 (9th Cir. 1991) ................................................................................. 13, 14

Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commission,

463 U.S. 582, 103 S. Ct. 3221, 77 L. Ed. 2d 866

(1983) ................................................................................................................................ 21

Hamilton Watch Co. v. Benrus Watch Co.,

206 F.2d 738 (2d Cir. 1953) 20

Larry P. v. Riles,

793 F.2d 969 (9th Cir. 1984) ................................................................................. 21, 22

Linton v. Com’r of Health and Environment,

779 F. Supp. 925 (M.D. Tenn. 1990) ...................................................................... 21

Republic of the Philippines v. Marcos,

862 F.2d 1355 (9th Cir. 1988) ............................................................................... C , -d

Scelsa v. City University of New York,

806 F. Supp. 1126 (S.D.N.Y. 1992) ............................................................................... 13

State of Alaska v. Native Village of Venetia,

856 F.2d 1384 (9th Cir. 1988) .................................................................................... 13

Statutes: Pages:

Cal. Health & Safety Code §1340 et seq .............................................................................. 9

Cal. Health and Safety Code §32000 et seq ....................................................................... 7

Cal. Welfare and Inst. Code §14200 ...................................................................................... 8

Cal. Welfare & Inst. Code §§14085.5 ....................................................................................... 11

ii Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

fc

iuile 208

Pages

Cal. Welfare Inst. Code §17000 6

28 U.S.C. §§1343(3)(4) ............................................................................................................. 13

42 U.S.C. §1981 ....................................................................................................................... 13, 22

42 U.S.C. §1983 ................................................................................................. •................... 13, 22

42 U.S.C. §2000d ................................................................................................................... passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e ............................................................................................................................ 21

U.S. Const., Amend. XIV ................................................................................................. 13, 22

in Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

St

Suite 206

INTRODUCTION

This proposed class action is brought on behalf of the minority poor of Contra

Costa County, who principally reside in West and East County areas, e.g., in the cities of

Richmond, Antioch and Pittsburg, to challenge both the location of a proposed County

hospital for the poor in a Central County area that is largely inaccessible to the minority

poor, and the failure of the Contra Costa Health Plan (hereafter "County Health Plan"),

the County-operated health maintenance organization to provide the opportunity to

obtain prepaid hospital care in areas of minority population in West and East County.

Plaintiffs ex parte application for a temporary restraining order and application for

preliminary relief seeks to enjoin pending trial any further expenditure or any further

preconstruction or construction activity for the proposed County hospital for the poor

until equal access to County hospital services is made available to the minority poor in

West and East County.

Balance of Hardships. First, Administration and congressional health reform

legislative proposals have jeopardized the federal MediCal reimbursement funding that

the County cited in its bond documents as the ultimate source for capital construction.

The proposed legislation largely eliminates the reimbursement, although the precise

outcome will not be known, if then, until the end of the present term of Congress when

any health reform package is enacted. The cost of preconstruction and any construction

is irrecoverable. If the project is cancelled or enjoined, the County can recover the cost

of the and prepayment penalty by putting the proceeds in taxable bonds and engaging in

arbitrage but the County cannot recover preconstruction and construction costs. Left to

its own devices, the County will encumber millions of the County’s already-inadequate

health services budget on preconstruction and construction.

Second, in response to a request by the County Health Services Department, the

three community district hospitals in Contra Costa County submitted a formal joint

proposal to the County Board of Supervisors in December 1993 to provide County

I.

1 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1 1

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

fc

hrite 208

hospital services in West, East and Central County areas at their respective facilities

immediately at far less cost and greater accessibility than construction of a replacement

Merrithew. At present the community hospitals have twice the number of vacant beds as

the replacement Merrithew would put into service. The joint proposal would provide to

the minority poor instant accessible hospital services in well-maintained, modern, local

institutions. In contrast, the present Merrithew hospital is dilapidated and any

replacement Merrithew is not only financially risky, but would not be ready for several

years. The County failed to respond to the joint proposal and one of the community

facilities has been taken over by a receiver. Rather than impose a moratorium on

construction, the County has moved up the groundbreaking for construction from August

to June 1994.

Third, the expenditure of funds to build a Central County hospital for the poor

perpetuates the County’s system of hospital services for the West and East County

minority poor inferior to that available to predominantly white Central County residents.

As a result, the West and East County poor will continue to suffer from adverse health

risks.

The County, on the other hand, will suffer no hardship because of the injunctive

relief.

Likelihood of Success. Plaintiffs can demonstrate likelihood of success under the

claim made pursuant to the implementing regulations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, because they merely have to prove disparate impact. The adverse effect of

building a Central County hospital on the minority poor in West and East is clear and

unmistakable. The location cannot be justified on the basis of necessity. Even if it could,

the joint community hospital proposal is a nondiscriminatory alternative that negatives any

necessity justification. Plaintiffs also are able to show that their intentional discrimination

claims raise serious questions going to the merits.

2 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

iuitc 208

II.

STATEMENT

A. Demoeraphics.

The poor in West and East County, most of whom are minority persons, have the

greatest unmet need for health services, including accessible hospital care, in Contra Costa

County.

Contra Costa County is California’s ninth most populous county with a 1990

population of 803,732. The County is commonly recognized to have four regional

subdivisions: West, East, Central and South County. Overall, the County is 70 percent

white, 12 percent Latino or Hispanic, nine percent African American and nine percent

Asian American. The minority population, however, is concentrated in West County

(principally in the City of Richmond and several smaller cities along the coast) and in

East County (principally in the cities of Pittsburg, Brentwood and Antioch). West County

is 55 percent minority and East County is 35 percent minority; in contrast, Central County

is over 80 percent white and South County is almost 90 percent white. See Exh. A, App.

4-5, 13 (Public and Environmental Health Advisory Board, 1992 Report on Status of

Health in Contra Costa and Recommendations for Action, October 26, 1992).

Ninety percent of the black population in the County resides in West or East

County; 63 percent of the County Latino population and 62 percent of the County Asian

American population resides in West or East County. The minority population of the

County, which is concentrated in West and East County, is increasing at the highest rates:

The 1990 Asian American population increased 156 percent over the 1980 population, the

Latino population grew by 63 percent, and the African American population by 23

percent. The County’s white population increased by only 11 percent in the same period.

See Exh. A, App. 13.

The majority of the County’s poor reside in West and East County. Of 78,679

MediCal eligible County residents in September 1991, fully 78 percent lived in West or

East County, 47 percent in West County and 31 in percent East County. Only 22 percent

3 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

&.

Suite 208

of MediCal eligible residents lived in Central County. The County’s MediCal population

is 59 percent minority and 41 percent white. West County is home to the largest number

of households headed by women and contains over half of the county’s homeless

population. East County has the lowest average household income of any region and

contains one-third of all the County’s AFDC recipients, despite having only one-fifth of

the total population. Over 57,000 Contra Costans live in poverty, including 22,000

children. Of children in poverty, four times as many are African American as white. As

a result of the higher rates of poverty, residents of West and East County are at increased

risk for serious health problems. See Exh. A, App. 4-5; Wills Deck 113; Exhibit V, App.

303-307 (California Medical Association statistical data).

Most of the minority poor live in West or East County. Most of the Central

County poor are white. See Id.

Richmond, Pittsburg, and Antioch, which have the highest minority populations,

have the highest hospitalization rates for chronic diseases, indicating lack of prevention

and adequate health care programs in West and East County. West County residents fare

substantially poorly in low birth weight, inadequate prenatal care and other indicators of

perinatal health. Half of all homicides in the County occurred in West County. Children

in West and East County are twice as likely to be hospitalized due to injury as children

in other regions. Exh. A, App. 8. After a comprehensive review of County’s state of

health, the County’s Public and Environmental Health Advisory Board concluded in 1992

as follows:

Poverty, poor education and housing, and limited access to health care place

growing numbers of [poor] families, particularly those living in West and

East County, at risk for poor health status.

* * *

[Hjealth problems . . . are occurring more frequently in West and East

Counties, where higher percentages of low income families, single heads of

households, homeless and other disadvantaged and undeserved groups

4 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Ec

trite 208

reside. These areas and subpopulations must be a priority for services . .

.. Services should be located in West and East County and must address

barriers to care such as . . . transportation . . . concerns.

Exh. A, App. 2, 11.

The fact that there is only one County Hospital, located in the central part of the

County, means that access to non-emergency hospital care is limited for large numbers

of patients because:

The geography of the County is such that poor people who reside in the western

and eastern portions are far removed from any central site and those areas are the

most rapidly growing;

The difficulties posed by the geographic spread are compounded by the

inadequacies of the public transportation system, particularly during evening, night

and weekend hours; and

Transporting patients to the County Hospital by ambulance or ambuvan offers

some relief from the access problem but it is very costly and currently limited to

patients with very specialized needs.

A majority of the patients served by Merrithew Memorial Hospital are poor or medically

indigent. They are significantly affected by the access problem since many live in western

and eastern portions of the County and often lack reliable means of private

transportation. As a consequence, they frequently delay seeking treatment until a minor

condition has escalated into an emergency. Exh. B, App. 19 (1988-89 Contra Costa

Grand Jury, "County Hospital Replacement," May 26, 1989).

The State of California has promulgated standards for accessibility to hospitals for

MediCal participants in prepaid plans of 30 minutes regular travel time or 15 miles

distance. See Exh. M, App. 231-32 (Cal Dept, of Corp., "Health Care Services Plan Act,

Instructions for Exhibits to Plan License Application, Item H," January 1986). The

County operates a special bus service, the "Martinez Link," between Richmond and

Merrithew, consisting of five round trip bus runs during work week daytime hours. The

5 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

&

Suite 208

scheduled running time between the Richmond/Bart stop and Merrithew is approximately

48 minutes. The distance is approximately 30 miles. Regular bus service takes

substantially longer. Travel from Richmond to Central County on BART requires

doubling back to Oakland to change to trains to Central County; there is no BART stop

in Martinez. There is no special bus service between East County and Merrithew; bus

transportation can take over an hour. The distance between Antioch and Merrithew is

approximately 19 miles. See Exh. B, App. 29.

B. Public hospital services for the poor.

The County has historically failed to provide accessible hospital services on an

equal basis throughout the County, concentrating services in Central County to the

detriment of the minority poor in West and East County.

Merrithew Memorial Hospital was established in Martinez in Central County in

1881 as the County hospital for the poor pursuant to Cal. Welfare Inst. Code §17000.

The County maintains Merrithew as the only County facility providing hospital services

for the poor throughout Contra Costa County, although most of the poor reside in West

and East County. Merrithew is also the centerpiece of the County Health Plan. The

County operates a principal clinic in Martinez, at the same site as Merrithew, and outlying

clinics at Concord, Pittsburg and Richmond, which feed patients who need hospital

services to Merrithew even when closer facilities are available in West and East County.

Anderson Deck U2. The County receives federal and state funds to provide hospital

services to MediCal and other poor persons. County hospital services are provided by

staff physicians employed by the County. See Exh. C, App. 67 ("Certificates of

Participation (Merrithew Memorial Hospital Replacement Project),” April 29, 1992).

Merrithew is a dilapidated facility that has been cited repeatedly for its failure to

provide accessible, effective hospital services. The major portions of the current main

hospital were constructed in the 1940’s and 1950’s. Although still in service, a majority

of the hospitals physical plant and systems are out-of-date and at or beyond the limits of

their projected useful life. Many of the facilities generally do not meet the standards of

6 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

S t

Suite 208

current health, safety, building and engineering codes, although code divergences have

been grandfathered in. See Exh. C, App. 67. The 1993 State Health Services Department

Medical Audit assessed the County Health Plan at the Martinez flagship clinic, which

feeds patients to Merrithew, for a "major deficiency" for persistent problems in patient

access to non-emergency care. The clinic had received the same major deficiency

assessment in its prior audit. (A major deficiency means "a problem of non-compliance

with policy, regulations, and contract standards that has the potential to endanger patient

care and/or operations.") The Audit found that waiting time for new patient

appointments is eight weeks to three months. Patients wait up to four hours in the

emergency room. The initial time for initial appointments is over six weeks and routine

appointments are not available within six weeks. There is no procedure to determine the

number of non-English speaking persons to assess adequacy of translators and

multilanguage information materials. Handicapped parking is not accessible. Exh. D,

App. 78, 81-82 (MediCal Review, "Report of the 1993 Annual Medical Audit of Contra

Costa County Health Plan," undated).

In contrast to the County’s central hospital system, privately-operated Raise*-

Permanente provides accessible hospital services to middle class persons under the same

Contra Costa County demographic conditions using a system of regional hospitals. See

Exh. Q, App. 271 (O ’Rourke curriculum vitae) O ’Rourke Decl. H2.

Brookside Hospital in West County with 217 active beds, Los Medanos Hospital

in East County with 101 active beds and Mt. Diablo Hospital in Central County with 260

active beds are community district hospitals established pursuant to Cal. Health and Safety

Code §32000 et seq. The community hospitals are governed by elected boards and have

authority to levy taxes within their districts. Each is a modern, well-maintained facility

which serves an economically integrated patient population. Brookside and Los Medanos

treat large numbers of MediCal patients on a fee for service basis, although the MediCal

reimbursement rate received by the community hospitals is lower than that received by

the County. In addition, Brookside and Los Medanos provide substantial amounts of

7 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

!aitc 208

unreimbursed care to medically indigent patients (for which the County receives funding)

through their emergency rooms because the travel time to Central County often renders

Merrithew practicably inaccessible, and County clinics in West and East County are closed

in the evenings and weekends and have long waiting lists. The provision of below-cost

MediCal reimbursed care and unreimbursed care to the medically indigent have put

Brookside and Los Medanos under severe financial pressure, and Los Medanos was put

in receivership in March 1994. See O’Rourke Deck, 113.

The community district hospitals, which have high hospital bed vacancy rates, have

declared their desire to assist the County to provide accessible hospital services for the

poor in their districts at their facilities. They are unable to do so on the below-cost

MediCal reimbursement fee for service rate or unreimbursed basis in a comprehensive

way, but have proposed providing accessible hospital services for the poor, including the

West and East County minority poor, on a prepaid basis through the Contra Costa Health

Plan at the same rates the Plan now receives for hospital-based services. See id. at H4.

C. Contra Costa County Health Plan.

The County has failed to provide equal access to hospital services in its prepaid

health maintenance organization, the Contra Costa Health Plan, for the West and East

County minority poor.

The County Health Plan is a federally and state subsidized and qualified prepaid

health maintenance organization operated by the County at Merrithew and County clinics.

The County Health Plan has a contract to serve MediCal-eligible and other poor persons

receiving public assistance as well as commercial paying patients. The Health Plan is

governed by a board consisting of the County Board of Supervisors. The Plan is funded

by prepayment and an annual County subsidy. The County subsidy in 1994 was eight

million dollars. Exh. E, App. 119 (Contract between State Department of Health Services

and County of Contra Costa, January 18, 1994); O’Rourke Decl.1I5.

The County Health Plan was originally established in 1973 to serve MediCal-

eligible and other poor persons exclusively pursuant to Cal. Welfare and Inst. Code

8 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

&

Suite 206

5

§14200. The Plan was subsequently expanded to commercial patients and licensed by the

California Department of Corporations pursuant to the Knox-Keane Health Care Service

Plan Act of 1975, Cal. Health & Safety Code §1340 et seq. See O’Rourke Deck 116. The

Plan is operated pursuant to a contract, last renewed in January 1994, between the State

Health Services Department and the County which requires that the County will not

discriminate against members or eligible beneficiaries because of race or color in

accordance with Title VI and the Title VI regulations, and that the County "agrees to

serve a population broadly representative of the various . . . so c ia l. . . groups within the

service area.” The contract specifies that the service area is the entire County. Exh. F,

App. 124, 128-29.

The County Health Plan’s single Central County hospital, on its face, cannot

comply with the MediCal hospital accessibility standards of 30 minutes travel or 15 miles

distance for the West and East County minority poor. Although more than three-quarters

of MediCal-eligible persons live in West and East County, the County Health Plan

principally serves Central County patients. Almost all of the Central County poor are

white. The Health Plan has failed to enroll any appreciable number of West and Eas4

County MediCal-eligible and other poor persons because it offers no hospital services in

West and East County. In contrast, the Plan’s commercial patients are almost exclusively

Central County residents because of the availability of an accessible Central County

hospital. See O’Rourke Deck H 7.

The County recently declined to permit the County Health Plan to provide prepaid

MediCal coverage to West and East County in collaboration with the Contra Costa

County Coalition for Managed Care (an organization of physicians, nurses, pharmacists

and other health professionals who provide health care to the minority poor in West and

East County), other West and East County traditional MediCal providers and the

community district hospitals. Such an arrangement would have permitted the County

Health Plan to provide hospital services to the West and East County poor as well as

Central County poor. Instead, the County has stated that its Health Plan should provide

9 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

itrite 208

prepaid hospital services only in Central County. The County Health Plan thereby seeks

to cater to the predominantly white commercial participants and Central County poor to

the detriment of the minority poor in West and East County. See Wills Decl. 114.

The State Department of Health Services has failed to enforce requirements that

the County make Health Plan hospital services available on an accessible basis throughout

its entire service area and make County Health Plan hospital services accessible to the

minority poor in West and East County.

D. Proposed Merrithew Replacement.

The County proposes to use MediCal and Medicare reimbursement funding to

build a replacement Merrithew facility in Central County that will fail to provide

accessible hospital services for West and East County, where three-quarters of the

MediCal-eligible patients and most of the minority poor reside. While permitting the

County to provide upgraded hospital services for commercial County Health Plan

participants, the replacement will siphon off and encumber health services funds that the

County properly should use to provide equal access to hospital and other health services

for the minority poor in West and East County.

At any given time, only 50 percent of beds at the community district hospitals are

utilized. The total number of vacant beds at the community district hospitals, figured on

the basis of that utilization level, is 288 beds: West County (Brookside), 108 beds; East

County (Los Medanos), 50 beds; and Central County (Mount Diablo), 130 beds. The

long term trend in medical care is toward lower hospitalization rates, suggesting that the

low community district hospital utilization rate will fall even more. See O ’Rourke Decl.

118.

The County has considered various proposals for a replacement for Merrithew for

over a decade. Proposals for a larger facility have been rejected largely for financial

reasons. The County did not consider the needs of the West and East County minority

poor or seek to justify the adverse impact of locating the replacement in Central County

on the poor, most of whom are minority residents of West or East County. The County

10 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

ta te 208

failed to consider proposals to implement plans to provide County hospital services in

community hospitals. For instance, a 1978 report to the County Board of Supervisors

recommended that Merrithew should not be rebuilt and that most of the functions of

Merrithew be placed in community hospitals in order to provide more accessible hospital

services. See O’Rourke Deck 119; Exh. R, App. 274-86.

The County Board of Supervisors submitted plans to the State Health Services

Department for the construction of a 144-bed replacement for Merrithew, less than half

the number of vacant beds currently available at the community district hospitals, in May

1993. Construction contracts limited to site work were let in 1993. State Department of

Health Services reviews of the plans and final contracts are expected to be completed in

May 1994. See Exh. C, App. 69.

In order to finance the Merrithew replacement, the County has issued certificates

of participation or bonds of over 125 million dollars, and created a non-profit public

benefit corporation that will actually own the replacement and lease it back to the County.

The County planned to make lease payments to the corporation for 30 years, which will,

in turn, be paid to the bond holders as debt service on the certificates. See Exh. S

(Gilbert curriculum vitae); Gilbert Deck 114. The source of the lease payments was

supposed to be supplemental MediCal service reimbursement payments under Cal.

Welfare & Inst. Code §§14085.5; 14105.98 (federal and state matching funds for hospitals

serving a "disproportionate share" of Medicaid patients). See Exh. C, App. 51-53; Exhs.

F and U (statutes). Under these programs, the County is liable for any reduced federal

financial participation. Cal. Welfare & Inst. Code §§14085.5(h)(i); 14105.98(p). Id.

Health reform proposals imperil the federal financing for debt service for the

replacement Merrithew. The Medicaid disproportionate share program was budgeted in

1993 at 17.9 billion dollars nationally. However, the Administration’s health reform bill,

S.1757, eliminates the disproportionate share program and replaces it with a discretionary

program. The Administration’s program is budgeted at only 800 million dollars annually

on a nationwide basis and restricts a hospital to only five years of payments. See Exh. G,

11 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

to te 208

App. 186 ("Public hospitals fear funding gap after disproportionate payments end," Nov.

22, 1993); Exh. H, App. 192 (S. 1757). The bill proposed by Rep. Pete Stark that passed

the Subcommittee on Health of the House Committee on Ways and Means in March 1994

replaces the disproportionate share program with a discretionary share program totalling

I. 2 billion dollars annually for the entire nation. See Exh. I, App. 198-203 (Stark bill

description). Should federal funding become unavailable or reduced, County general

funds for health services for the next 30 years would be encumbered to construct the

replacement Merrithew to the detriment of the West and East County minority poor. See

Exh. C, App. 53 Health care services would have to be sacrificed for an unnecessary

hospital.

On April 13, 1993, plaintiffs filed an administrative complaint of discrimination

with the Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The complaint challenged the location of the replacement Merrithew in Central Count)'

as racially discriminatory in violation of Title VI and Title VI regulations. The

administrative charge is still pending. See Exh. F, App.__ (letter administrative

complaint).

The County requested the Central County community district hospital, Mount

Diablo, to prepare a plan to provide countywide County health services at Mount Diablo

in lieu of a replacement Merrithew in fall 1993. On December 11, 1993, Mount Diablo

together with the other community district hospitals, Brookside and Los Medanos,

formally presented a joint proposal to provide accessible County hospital services in West,

East and Central County areas in their respective facilities at far less cost and greater

accessibility than construction of a replacement Merrithew. The County has failed to

respond to the joint proposal. See Exh. J, App. 205 ("Joint Hospital District," December

II, 1993); Exh. K, App. 218 (Letter to Supervisor Powers from Hospital Districts, April

1, 1994).

Groundbreaking and construction of the replacement Merrithew have been

advanced to commence in June 1994 instead of the original August 1994 date. The

12 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Ic

Mite 208

County has rejected all requests for a moratorium on expenditure of funds for the

proposed hospital. See O ’Rourke Deck 1111; Exh. K, App. 218.

The State Department of Health Services has failed to enforce requirements that

the County provide accessible hospital care on an equal basis throughout the Count}' and

make County hospital services accessible to the minority poor in West and East County.

E. Proceedings.

The applications for a TRO and preliminary injunction are being filed with a class

action civil rights complaint by several minority West and East County MediCal-eligible

individuals who allege that they have been adversely affected by the proposed location of

the Merrithew replacement and the restriction of County Health Plan hospital services to

Central County, Catherine Latimore, Percy and Betty James, Dorothy Kountz, and Ralph

McClain. Joining as plaintiffs were several churches with MediCal-eligible and other poor

members and persons served in their ministries, the New St. James Missionary Baptist

Church, Easter Hill United Methodist Church, Sojourner Truth Presbyterian Church and

Unity Church Complaint.

The complaint is brought under 28 U.S.C. §§1343(3) and (4) and 42 U.S.C. §1983

to enforce the Title VI regulations, Title VI, 42 U.S.C. §1981 and the Fourteenth

Amendment/42 U.S.C. §1983 for preliminary and permanent injunctive relief. Id.

III.

THE STANDARD FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

The Ninth Circuit has stated that plaintiffs are entitled to preliminary injunctive

relief if they demonstrate either (1) a likelihood of success on the merits and the

possibility of irreparable injury, or (2) the existence of serious questions going to the

merits and the balance of hardships tipping sharply in their favor. Gilder v. PGA Tour,

Inc., 936 F2d 417, 422 (9th Cir. 1991); Republic o f the Philippines v. Marcos, 862 F2d 1355,

1362 (9th Cir. 1988)(en banc); Slate o f Alaska v. Native Village o f Venetia, 856 F2d 1384,

1389 (9th Cir. 1988); see Scelsa v. City University o f New York, 806 F. Supp. 1126 (S.D.N.Y.

1992)(granting preliminary injunction in Title VI challenge to location of ethnic studies

13 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

fc

trite 206

institute);

"The critical elem ent in determining the test to be applied is the relative hardships

to the parties. If the balance of norm tips decidedly toward the plaintiff, then the plaintiff

need not show as robust a likelihood of success on the merits as when the balance tips

less decidedly." Gilder, 936, F2d at 422, quoting Benda v. Grand Lodge o f International

Association o f Machinists & Aerospace Workers, 584 F2d 308, 315 (9th Cir. 1928), cert,

dismissed, 441 U.S. 937, 99 S. Ct. 2065, 60 L. Ed 2d 667 (1929).

IV.

THE BALANCE OF HARDSHIPS TIPS SHARPLY IN PLAINTIFFS’ FAVOR

A. Harm to Plaintiff.

Continued expenditure of funds and preconstruction and construction activities for

the new hospital works three distinct hardships on plaintiff. First, federal funding is in

jeopardy and construction costs may very well encumber County health and other services

for the poor. Second, preliminary injunctive relief until equal access to hospital care is

assured the West and East County minority poor is necessary to prompt immediate

consideration of the joint community hospital proposal, a less costly, nondiscriminatory

alternative that would provide accessibility. Third, the construction of a Central County

hospital perpetuates racially disparate County hospital service policies, that impose

adverse health risks on the minority poor.

1. Preconstruction and construction costs.

Funds to pay these and other construction costs were raised by the County through

issuance of 125 million dollars of certificates of participation or bonds. The prospectus

for the issuance states that the two large sources for financing are SB 1732 and AB 855,

which are funded by Medicaid "disproportionate share" funds. Exh. C, App. 14-16. In

1993, the disproportionate share program provided hospitals with 17.9 billion dollars for

construction. SB 1732, codified as California Welfare and Instit. Code §140 85.5, provides

supplemental MediCal reimbursement for the cost of capital construction for 53 percent

of the debt service. These supplemental MediCal funds, most of which are passthrough

14 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

&

Suite 208

federal disproportionate share funds, are to be used for hospitals that contract to provide

inpatient MediCal services affected by serving a "disproportionate share" of MediCal

patients. Welfare & Institutional Code §1408.5.5(a). SB 1732, however, does not

guarantee continued funding. Cal. Welfare & Instit. Code §14085.5(h)(i) ("[a] hospital

receiving supplemental reimbursement pursuant to this section shall be liable for any

reduced federal financial participation resulting from the implementation of this section").

Exh. T, App. 295.

SB 855, codified as Cal. Welfare & Instit. Code §14105.98, provides MediCal

payment adjustments to hospitals for care of uninsured and underinsured patients, that

the County projected in its prospectus to pay for 36 percent of the debt service. Exh. C,

App. 15-16. SB 855 funds are federal disproportionate share and state matching monies.

SB 855, like SB 1732, contains an express disclaimer of continued financial support. Cal.

Welfare & Instit. Code §14105.98(p) ("If, for any payment adjustment year, the amount

in the fund, when matched by federal funds . . . are insufficient to pay some or all of the

payment adjustment amounts otherwise due under this section, payment amounts should

be reduced . . . "). Exh. U, App. 300.

The Administration’s health reform bill, S.1757, eliminates the state

disproportionate share allotments that fund SB 1732 and AB 855. See S.1757, §4231(c)

("the state DSH allotment shall be zero"). Exhs. G, & H, App. 189. Section 3481(b)

replaces the current disproportionate share program with a discretionary program in which

"[a]n eligible hospital shall receive a payment under this section for a period of 5 years,

without regard to the year for which the hospital first receives a payment." Exh. H, App.

192. The discretionary program is projected to fund only 800 million dollars annually on

a national basis, for a reduction of 95 percent from 1993 funding levels. A replacement

bill authored by Rep. Pete Stark, passed the Subcom. on Health of the House Committee

on Ways and Means in March 1994. The Stark bill similarly creates a much-reduced

discretionary program for capital construction at hospitals to replace the disproportionate

share program. See Exh. I, App. 196. Under the Stark bill, the replacement program

15 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Sc

hate 208

totals 1.2 billion dollars annually on a nationwide basis, for a reduction of 93 percent from

1993 levels. See Exh. I, App. 198-203.

The Stark bill caps capital expenditure grants to any hospital at 25 million dollars.

See Exh. I, App. 203. In contrast the County has projected disproportionate share funds

of 110 million dollars under both SB 1732 and AB 855. Under either the Administration

or Stark bills, most of the federal financial funds anticipated by the County will not be

forthcoming.

In the event the project is cancelled for fiscal or other reasons or enjoined by this

Court, the County can defease or pay off the 1992 issuance to cover the cost of the

prepayment penalty by using the proceeds from the issuance to invest in higher-yielding

taxable bonds and engaging in arbitrage. See Gilbert Deck 115. Preconstruction and

construction costs, however, cannot be defeased though arbitrage. Id. The County has

covenanted under its lease arrangement with the special benefit corporation that will

actually own the replacement Merrithew to "take such action as may be necessary to

include all Base Rental Payments and Additional Payments for such properties in its

annual budgets and to make the necessary annual appropriations therefor." Exh. C, App.

53. If, as is likely, federal funding should fail, the County would have to pay

preconstruction and construction costs out of the same pool of funds it uses for County

health services for the poor, using service dollars for bricks and diminishing the already-

inadequate level of health services for the plaintiff minority poor and the other poor of

Contra Costa County. Prudence requires that hospital costs be curbed in the face of fiscal

uncertainty.

2. Joint Community Hospital Proposal.

As early as 1978, the county was advised to consider having the community district

hospitals provide county hospital services instead of rebuilding Merrithew. See O’Rourke

Deck 119, Exh. R, App. 285-86. The community district hospitals jointly have 288 vacant

hospital beds available in institutions accessible to residents of West, East and Central

County. See O’Rourke Deck 11113,8. That is fully twice the 144 beds that the replacement

16 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Sl

Suite 208

Merrithew will supply. In fall 1993, the County Health Services Department requested

the Central County community district hospital, Mount Diablo, to prepare a plan to

provide County hospital services for the entire County instead of proceeding with

Merrithew. Mount Diablo requested the two other community hospitals, Brookside in

West County and Los Medanos in East County, to join it in devising a plan. See Exhs.

J & K, App. 205, 218. On December 11, 1993, the three community hospitals submitted

a joint proposal to provide County hospital services in their three regions of the County

at their respective facilities at less cost and with greater accessibility than the construction

of a replacement Merrithew. Id.

However, County Supervisor Mark DeSaulnier has submitted a request, to be heard

at the April 19, 1994 County Board of Supervisors meeting, directing County staff to

negotiate with the community district hospitals concerning their joint proposal. Exh. P,

App. 269-70.

The joint proposal offers a compelling, nondiscriminatory alternative. The joint

community hospital proposal would provide the plaintiff class with the accessible County

hospital care they seek. On March 18 , 1994, the East County community hospital, Los

Medanos, was taken over by a receiver for failure to meet its obligations, largely because

of financial distress caused by providing below-cost MediCal reimbursed care and

unreimbursed care of the medically-indigent. If Los Medanos were permitted to

participate in the joint proposal, its financial distress - resulting from the existence of the

Merrithew facility which prevents Los Medanos form obtaining a more favorable MediCal

reimbursement rate and which receives reimbursement for care of the medically indigent -

- would be cured. However, if the receiver were to sell Los Medanos or otherwise use it

as other than a community hospital, the joint proposal would be jeopardized and plaintiffs

precluded from obtaining meaningful relief. See O’Rourke Deck 1112. Preliminary

injunctive relief enjoining expenditure for the Merrithew replacement until equal access

to County hospital service is made available to the minority poor in West and East County

should assure prompt consideration of the joint proposal.

17 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

1 2

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

Suite 206

3. Adverse Health Risks to the Minority Poor.

The provision of inaccessible hospital services imposes the following adverse health

risk on the minority poor:

In emergencies, and for urgent care needs nights and weekends after local county

clinics have closed, the minority poor use the often crowded emergency rooms of

community district hospitals. Their medical records are unobtainable to the private

physicians who attend them and follow up care at county clinics lacks continuity for this

reason. See O’Rourke Deck H 10.

Primary care clinics are accessible geographically, but cutbacks in recent years have

curtailed preventive health programs and clinic hours, creating delays for appointments

of several weeks. When referrals are required for consultations, X-ray, laboratory and

imaging examinations not available in local clinics, patients must make the long trek to

Martinez each referral visit. Inability to comply is frequent and failure to do so, due to

lack of means of transportation, results in delays in treatment, exacerbation of illness, and

the need to be hospitalized when early intervention could have prevented this eventuality.

Id.

Case management for illnesses of major import is also seriously impaired when

hospital-based resources are not proximate. Preadmission procedures, hospital workup,

and effective discharge planning lose continuity when patients who are poor are forced

to use a hospital far from home. Visits by friends and family are discouraged, leaving

patients vulnerable to fear, apprehension, and depression in the absence of support critical

to their prompt recovery. Length of stay is prolonged and instructions for continuing care

at home made very difficult. Such circumstances conspire to bring about complications

and poor treatment outcomes. Id.

Health maintenance organizations, to be most effective, place hospital-based

technology and services as close as possible to both primary care providers and those

specialists who are in most common demand to serve the enrolled population in the

communities where they reside. This service strategy is absolutely critical for low income

18 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

1 2

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Sc

minorities whose mobility is much more restricted than middle class members of an health

maintenance organization. Id. See Decls. of Latimore, Kountz, Peicy James, McClain

& Bernstine (harm to plaintiffs).

B. Absence of Harm to Defendants.

In contrast, defendants County, and County and State Health Service Departm ent

will suffer no detriment by issuance of preliminary injunctive relief for plaintiffs. Final

state approvals on the County’s plans and contracts is not expected until May 1994. The

original construction date is not until August 1994. The County may argue that any delay

will jeopardize contracts it has already entered or delay its accelerated timetable. Such

"penny wise and pound foolish" arguments are counterbalanced by federal fiscal

uncertainty about the kind and level of support available for hospital construction. These

arguments also must be balanced against the significant public benefits of the joint

community district hospital proposal.

C. Harm to the Public.

The issuance of a preliminary injunction serves the public interest in obtaining

better health care for the minority poor and in avoiding waste of scarce public funds. As

the County’s Public Health and Environmental Advisory Committee found, the public

health of the County as a whole is best served by pr oviding accessible health care to West

and East County poor, particularly the minority poor. See Exh. A, App. __. A

replacement Merrithew is not needed in light of the large number of vacant beds at the

County district hospitals and the December 1993 joint proposal of the district hospitals

to provide County hospital services accessible to residents of West, East and Central

County. In an era of limited resources, proceeding with the construction is tantamount

to fiscal waste. Gilbert Decl. 113. At the same time, the joint community district hosprtal

proposal is a nondiscriminatory alternative that is not only fiscally attractive, but desirable

on public health and civil rights grounds.

19 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

St

Suite 208

V.

PLAINTIFFS HAVE DEMONSTRATED

A LIKELIHOOD OF SUCCESS ON THE MERITS

In light of plaintiffs’ showing on the balance of relative hardship to the parties the

Ninth Circuit requires merely the existence of serious questions going to the merits.1

In fact, plaintiffs can demonstrate likelihood of success on the merits or their

disparate impact Title VI regulatory claim as well as the existence of serious questions

going to the merits on their purposeful discrimination claims.

A. Disparate Impact Claim.

Title VI provides that: "No person in the United States shall on the ground of race,

color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or

be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial

assistance." The Title VI regulations provide, in pertinent part that:

(1) A recipient . . . may not, directly or through contractual or other

arrangements, utilize criteria or methods of administration which have the effect

of subjecting individuals to discrimination because of their race, color, or national

origin, or have the effect of defeating or substantially impairing accomplishments

of the objectives of the program as respect individuals of a particular race, color

or national origin.

(2) In determining the site or location of a facility, an applicant or recipient

may not make selections with the effect of excluding individuals from, denying

1 According to the Ninth Circuit:

For purposes of injunctive relief, "‘serious questions’ refers to questions which

cannot be resolved one way or the other at the hearing on the injunction and as to

which the court perceives a need to preserve the status quo lest one side prevent

resolution of the questions or execution pf any judgment by altering the status quo."

Republic o f the Philippines, 862 F2d at 1362. "Serious questions are ‘substantial,

difficult and doubtful, as to make them a fair ground for litigation and thus for

more deliberate investigation.’" Id. (quoting) Hamilton Watch Co. v. Benms Watch

Co., 206 F2d 738, 740 (2d Cir. 1953)." Serious questions need not promise a

certainty of success, nor even present a probability of success, but must involve a

‘fair chance of success on the merits’" Id. (quoting Natural Wildlife Federation v.

Coston, 773 F2d 1513, 1517 (9th Cir. 1985).

20 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

&

Suite 208

them the benefits of, or subject them to discrimination under any programs to

which this regulation applies, on the ground of race, color, or national origin; or

with the purpose or effect of defeating or substantially impairing the

accomplishment of the objective of the Act or this regulation.

The Supreme Court has judicially implied a right to bring civil actions to enforce

both Title VI, see Cannon v. University o f Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 99 S.Ct. 1946, 60 L.Ed.

2d 560 (1979) (Title IX case), and the Title VI disparate impact regulations. Alexander

v. Choate, 469 U.S. 287, 292-94, 105 U.S. 712, 716, 83 L.Ed. 2d 661 (1985); Guardians

Association v. Civil Service Commission, 463 U.S. 582, 103 S.Ct. 3221, 77 L.Ed.2d 866

(1983); Lany P. v. Riles, 793 F2d 969, 981-83 (9th Cir. 1984); Assoc, o f Mexican American

Educators v. State o f California, 836 F. Supp. 1534, 1545-48 (N.D. Cal. 1993) (Orrick, J.);

Linton v. C om ’r o f Health and Environment, 779 F. Supp. 925, 934-35 (M.D. Tenn. 1990)

(enjoining nursing home bed certification policy with unjustified adverse impact). In

order to prove a Title VI disparate impact regulatory violation, the Ninth Circuit has

adopted Title VII employment discrimination disparate impact standards. L a n y P., 793

F2d at 982 n. 9 and accompanying text and, 983; see also Mexican-American Educators, 836

F. Supp. at 1545. These standards have been legislatively codified in the 1991

amendments to Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(k)(l)(A), 2 requiring consideration of

plaintiffs’ showing of disparate impact of the facially neutral practice or policy, defendants’

showing of necessity for the practice or policy, and plaintiffs’ showing of a

nondiscriminatory alternative. * (i)

2 An unlawful employment practice based on disparate impact is established under

this subchapter only if

(i) a complaining party demonstrates that a respondent uses a particular

employment practice that causes a disparate impact on the basis of race, color . . .

or national origin and the respondent fails to demonstrate that the challenged

practice is job-related for the position in question and consistent with business

necessity; or

(ii) the complaining party makes [a] demonstration . . . with request to an

alternative employment practice and the respondent refuses to adopt such

alternative employment practice.

21 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

k

taite 206

With respect to disparate impact, the construction of a Central County hospital for

the poor has a clear and unmistakable impact on the minority poor because of Contra

Costa County’s demographics. The Central County poor, who receive preferential County

hospital services, are predominantly white. Ninety percent of the African American

population, 63 percent of the Latino population and 62 percent of the Asian American

population live in either West or East County. Fully 78 percent of the mostly minority

MediCal eligible population lives in West or East County. Most of the minority poor live

in West and East County where they are outside the prepaid plan MediCal hospital

accessibility standard of 30 minutes travel and 15 miles distance for Merrithew. See supra.

Plaintiffs believe that defendants cannot demonstrate that the location of the sole

County hospital for the poor in Central County is justified on necessity grounds.

Even if defendants were able to justify the location, the joint community district

hospital proposal — which provides accessible care on an immediate basis at less cost in

existing local hospitals -- is a nondiscriminatory alternative that would negative any

showing of necessity. Any necessity justification, in any event, would be undermined by

the likely disappearance of much of the federal funding the County had relied upon for

hospital construction.

B. Purposeful Discrimination Claims.

Plaintiffs’ Title VI, 42 U.S.C. §1981 and 42 U.S.C. §1983/Fourteenth Amendment

claims acquire proof of intentional discrimination. See, e.g., Lany P., 793 F. 2d 981. The

Supreme Court has declared that "[determining whether invidious discriminatory purpose

was a motivating factor demands a sensitive inquiiy into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available." Arlington Heights v. Metro Housing Corp, 429 U.S.

252, 266, 97 S.Ct 555, 50 L.Ed 2d 450 (1977). Arlington Heights lists the following

evidence that should be considered in determining if discriminatory purpose exists: (1) the

impact of the official action, whether it bears more heavily on one race than another, may

provide an important starting point; (2) the historical background of the decision,

particularly if a series of official actions was taken for invidious purposes; (3) departures

22 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Sc

Suite 208

from the normal procedural sequence; and (4) substantive departures, particularly if the

factors usually considered important by the decisionmaker strongly favor a decision

contrary to the one reached. 429 U.S. at 266-67.

The instant record, in addition to the showing of adverse impact, shows:

Historical background. The proposed hospital construction perpetuates a

longstanding, historic pattern of providing County health services to the West and East

County minority poor inferior those provided by the County in Central County. The

pattern is exemplified by the failure to even provide County hospital services in West and

East County, thus imposing a unique transportation burden on the minority poor; by the

provision of inferior clinics with no evening or weekend hours in West and East County

while maintaining a 24 hour Central County Martinez clinic Anderson Deck 113; by the

centralization of preventive public health services for West and East County in Central

County Id. at H14.; and by the concentration in recent years of County health services

cutbacks in West and East County. See Exh. N, App. 233, (1992 cuts); Exh. O, App. 256

(1989 cuts); Anderson Deck H5.

The proposed hospital construction perpetuates an overall pattern of providing

County services to the minority poor inferior to those provided by the County in Central

County. For example, the Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

ruled on December 30, 1992, that the County’s centralization of its general assistance and

food stamp program in Central County would have an unjustified disproportionate impact

on minority residents in violation of Title VI regulations. The Department of Agriculture

found that: "While the plan appears to apply equally to all clients, it falls more harshly on

clients whose ethnic origin is African American, Hispanic, Vietnamese and Latino and

devices equal areas to service to persons with disability, the non-English speaking, the

homeless and aged [general assistance and food stamp] recipients." The Department of

Agriculture cited demographic data showing that the general assistance and food stamp

population in Martinez where the County had planned to centralize its operations was

three-quarters white, while clients of facilities in West and East County cities of

23 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

St

Richmond, Antioch and El Sobrante were predominantly minority. As a result, the

Department of Agriculture found that the transportation burden of the centralization

policy would fall disproportionately on minorities. See Exh. L, App. 220 (investigation

report, December 30, 1992).

Procedural Departures from Regularity. 1 he proposed hospital construction

departs from procedural regularity. For instance, the planning for the replacement

Merrithew and operations of the Health Plan have proceeded largely without public

scrutiny or participation. Certificates of participation for construction of the Merrithew

replacement were issued that avoided public scrutiny or debate instead of County general

obligation bonds, which would have required a 2/3 vote of County residents.

Notwithstanding the countywide service area of its Health Plan, the County has declined

to consider arrangements with the Coalition for Managed Care and the community district

hospitals that would effectuate the provision of accessible countywide hospital and other

services. Until December 1993, the County ignored the requests of community district

hospitals to provide hospital services in lieu of a Merrithew replacement. Even then, the

County sought a proposal solely from the Central County community hospital and has

failed to respond to the joint proposal of the community hospitals. The County has

proceeded with preconstruction and construction activities notwithstanding the pendency

of the Title VI administrative charge, and fiscal uncertainty, and the joint community

hospital plan. See supra.

Substantive Departures from Regularity. The proposed hospital construction

departs from substantive regularity. For example, the County is proceeding with

construction of a new 144-bed hospital notwithstanding that there are twice the number

of available vacant beds in community district hospitals. Both the location of the

replacement Merrithew in Central County and the restriction of County Health Plan

hospital services to Central City violate the prepaid MediCal plan standard of 30 minute

or 15 mile hospital accessibility rule for the West and East County minority poor. The

County maintains and subsidizes a Health Plan out of Merrithew that purports to have

24 Memorandum of Points & Authorities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

It

luite 208

a countywide service area, but in fact principally serves a predominately white Central

County participants. See supra.

Plaintiffs, at the very least, present serious questions going to the merits on their

claims of purposeful discrimination.

VI.

CONCLUSION

The Court should grant the exparte application for a temporary restraining order

and the application for preliminary injunction.

Dated: April 14, 1994

N A A C P L E G A L D E F E N S E A N D

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 West Ninth Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

LESA RENEE MCINTOSH

3718 MacDonald Avenue

Richmond, CA 94805

(510) 237-2618

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

25 Memorandum of Points & Authorities