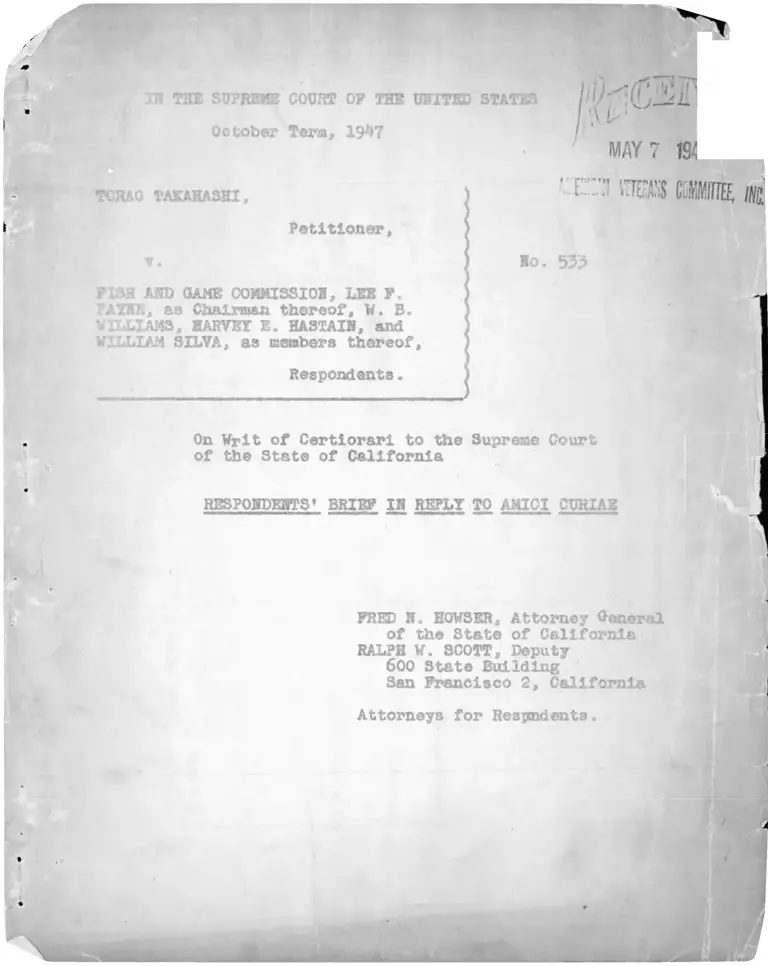

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission Respondents' Brief in Reply to Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission Respondents' Brief in Reply to Amici Curiae, 1948. 4c297153-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f15621c1-ba9a-45bb-814e-5c2daf1259cc/takahashi-v-fish-and-game-commission-respondents-brief-in-reply-to-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

13 THE SUPREME COURT OP THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 19**7

0 TAKAHASHI,

Petitioner,

v.

FISH AND GAME COMMISSION LEE P.

PAYNE, as Chairman thereof, W. B.

WILLIAMS, HARVEY E. HASTAIH, and

WJ'jLIAM SILVA, as members thereof,

Respondents.

i’ i / f ' t ' J L i

MAY 7 m

'x:::;' n ® 5 can

Ho. 533

INC.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

RESPONDENTS * BRIEF IN REPLY TO AMICI CURIAE

FRED N„ HOWSER. Attorney General |

of the State of California

RALPH W. SCOTT, Deputy

600 State Building

San Francisco 2, California

Attorneys for Respondents.

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

SECTION 990 IS NOT BASED ON RACE OR COLOR

THERE WAS NO EVIDENCE INTRODUCED BY THE PETITIONER IN THE TRIAL COURT

CHAPTER 181 (CALIF. STATS. 1.945 ) SHOULD

BE CONSTRUED AS A WHOLE 0 IF 50 CONSTRUED

ITS HISTORY SHOWS THAT IT IS NOT ANTI-JAPANESE

COMMERCIAL FISHING IS NOT A COMMON OCCUPATION

THE CHALLENGED STATUTE IS A CONSERVATION MEASURE , I

SECTION 990 WAS CONSTRUED AS A CON

SERVATION MEASURE BY THE HIGHEST COURT

IN CALIFORNIA» THIS CONSTRUCTION SHOULD

BE FOLLOED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREMECOURT.

PETITIONER CANNOT LIMIT HIS FISHING TO THE HIGH SEAS

PETITIONER DOES NOT PRESENT A RECORD

WHICH SHOWS HE CAN BE AFFORDED ANYRELIEF

1

3

6

1 1

13

15

17

2C

TABLE OP AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Alsos v . Kendall, 227 ?ae„ 286

Bayside Pish Flour Co. v. Gentry, 297 U.S. 422

Geer v. Connecticut, 161 U.S. 519

In re Ah Chong, 2 Fed. 753

Koramatsu v„ United States, 323 U.S, 239

Llndsley v. Hatural Carbonic Gas Co-

220 u. S. 61, 78, 79

Lubetlch Vo Pollock, 6 Fed. 2d 237

McReady v. Virginia, 90 U. S, 391

Morehead v.Hew York, 298 U. S. 587

State v. Catholic, 75 Ore. 367, 147 Pac. 372

State v. Leavitt, 105 Me. 76, 72 Atl. 875

Terrace Y. Thompson, 263 U. 3. 197

Thomson v. Dana, 32 Fed 2d 759

Statutes:

Calif. Stats. 1945, Chap. 181

Calif. Stats. 1947, Chap. 1329

56 Stat. 182

58 Stat. 827

59 Stat. 658

Texts:

Webster's International Dictionary,

2d edition

IN THE SUPREME COURT OP THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 19^7

TORAO TASAHASHX j )

Petitioner, \

v. | Ho. 533

PISH AND GAME COMMISSION, LEE F„ \

PAYNE3 as Chairman thereof, W„ Be I

WILLIAMS, HARVEY E. HASTAIN, and. )

WILLIAM SILVA, as members thereof, |

Respondents, }

RESPONDENTS * BRIEP IN REPLY TO AMICI CURIAE

SECTION 990 IS NOT BASED ON RACE

OR COLOR

Of all the amici curiae briefs, the one filed by

the United States comes closest to a dispassionate consid

eration of section 990 of the Pish and Game Code, It avoJ.ds

such tangential Issues a3 to whether California is ’’anti-

Japanese'* and was actuated by dislike for the Japanese when

chapter 181, Calif, Stats. 19^5* was enacted. It comes

directly to the proposition that any alien Ineligible to

citizenship may attack section 990 with as much propriety

as the petitioner, Irrespective of whether he Is a Malayan

02? a member of any of the so-called Asiatic races (pps. 4

and 5, brief for the United States). It argues that the

difficulty with section 990, as amended in 1945, is that It

draws the line "based on race and color" (p. 4) and that if

the petitioner wore a Malayan his attack "would surely have

no less merit” (p. 5). The contention is then made that

section 990 of the Pish and Game Code is based on race and

color. Such a conclusion, however, can only be reached by

reading the Nationality Act of 1940 (54 Stat. 1157, as

amended) into the California statute.

The fundamental difficulty with this argument is

that California did not base chapter l3l on race and color.

It based Its statute on Ineligibility to citizenship and on

the relative proximity of the particular groups to beneficial

ownership of the fish and game. The Congress determined

which groups of persons are eligible and which are ineli

gible to citizenship. California as a sovereign state had

no part In the determination. If tomorrow Congress should

decide that any group of white aliens thereafter would be

ineligible to citizenship, such persons would be affected

by section 990 of the Fish and Game Code irrespective of

race or color. Conversely, the Congress might at any time

permit alien Japanese to become citizens. It presently con

-2-

templates such action (H. R. 500̂ )., In the past It did so

in the case of Chinese and persons Indigenous to India. It

could similarly deny eligibility to citizenship to persons

or nationals now eligible and such persons could not then

contend with propriety that the California statute was

aimed at them on account of their race, color or nationality.

In short, it is the respondent9e contention that

chapter l8l, California Stats. 19^5 is not racial and tho

Nationality Act of 19^0 does not make it so. How can it

logically be urged that section 990 is based on race and

color when persons of the yellowand brown races are eli

gible to citizenship and hence may fish commercially in

California? Chinese and Hindus belong to the so-called

yellow or brown races; yet they qualify for commercial

fishing licenses. The argument that the statute is based

on color falls of its own weight, since persons of all

color are penaltted to fish commercially in California.

THERE WAS NO EVIDENCE INTRODUCED BY

THE PETITIONER IN THE TRIAL COURT

The petitioner as veil as the amici are imbued

with the erroneous idea that there is any evidence in this

case. At pages 9 and 10 of the brief for the United States

-5-

It Is assarted that the “impressive evidence assembled by

the petitioner" refutes the idea that section 990 was in

tended as a conservation measure. Counsel for the peti

tioner pointed out in oral argument that thore was no evi

dence offered because only issues of law are involved.

nevertheless after the trial and during the appeal the

petitioner and the amici would Inject into the case, argu

endo, statements which are largely the conclusions and

opinions of various persons and would not be admissible if

offered in evidence in the trial court. They seem to

think that the printed word Is beyond challenge. For ex

ample, at pages 27 and 28 of his brief the petitioner

points out that Mr. Howard Goldstein says there were no

fishermen ineligible to citizenship who fished in Cali

fornia except two Koreans and a Guamese. Apparently the

amici rely on the same incompetent evidence. They neglect,

however, to point out that Mr. Goldstein was the employee

of petitioner or his counsel and that the magazine “Pacific

Citizen" which contained the Goldstein "Survey" Is the

official publication of the Japanese American League. The

petitioner and the amici leave it to respondents to do so.

The respondents took pains at pages 24 and 25 of their brief

to point to two possible errors In the Goldstein report,

-4-

the purpose being to show that If the report la incorrect

in some respects it is apt to be Incorrect in others.

The only evidence In this case Is the deposition

of Miss Geraldine Connor, a witness for the petitioner

(R. 26-29),. This deposition was only introduced by stipu-

lation. Respondents also have no objection to the con

sideration of any statistical data contained in its Pish

Bulletins or Biennial Reports. But they do object to the

consideration of the mass of Incompetent '’evidence'1 pro

duced for the first time on appeal by petitioner and some

of the amici which ”evidence"was never offered In the trial

court.

The briefs of the Japanese American Citizens

League and other amici are replete with excerpts from mag

azines, books, etc. and with the conclusions and opinions

of various persons. The respondents, of course, have never

had an opportunity to crosa-exaalne Mr. Goldstein, or any

other persons whose conclusions are set forth In the briefs.

The difficulty here lies in an attempt by the petitioner

and the amici to prove the case in the reviewing courts.

That, of course, is contrary to normal procedure where all

the pertinent evidence is or whould be produced at the

trial. Here, however, we have exactly the normal process

-5-

in reverse.

As no proof was offered by petitioner in support

of the allegations of his petition and as the answer denied

that section 990 of the Fish and Game Code was enacted for

the purpose of discriminating and administered in a manner

to discriminate against the petitioner solely because of

his race, the allegations of the answer must be taken as

true {see cases citod at page 5 2, brief in opposition to

petition).

CHAPTER 181 (CALIF. STATS. 19^5)

SHOULD BE CONSTRUED AS A WHOLE.

IF SO CONSTRUED ITS HISTORY SHOWS

THAT IT IS NOT ANTI-JAPANE3E

The amici and the petitioner alike fail to con

sider the rule of the statutory construction that a stat

ute must be considered as a whole (R. 4l). As pointed out

at page 5 of our brief in opposition to the petition the

statute dealt not only with commercial fishing licanses

but also the hunting licenses and sport fishing licenses.

The brief of the Japanese American Citizens

League goes to considerable length to try to show anti-

Japanese sentiment in California during the war years.

Such argument is idle. The League concedes, however, that

the legMation of 19^7 and 1948 showed a turn for the*

-6-

bettor as far as Japanese are concerned because In 1947

there vas only one "unfavorable measure passed" In

19^8 "there vas nothing" (page 45). The League, however,

fails to say there vas anything favorable passed. It does

jiCt mention Stats. Cal. 1947, Chap. 1529, whereby sections

4^7 and 428 of the Fish and Game Code was amended so as to

permit aliens ineligible to citizenship to enjoy hunting

and sport fishing privileges. If California Is"anti-Japanese"

this action of the 1947 legislature does not so Indicate.

It is undoubtedly true that in 1945 Californians

as well as all persons in the United States wore not fav

orably impressed by the Japanese. The action of the leg

islature at that time in denying alien Japanese hunting

as well as sport fishing and commercial privileges would

unquestionably have been upheld under the clear and present

danger doctrine (Korematsu v. United States. 525 U.S. 259).

In 1945 the Korematsu case had not been decided and Cali

fornia did not know whether the Japanese would be returned

from the concentration camps. If this Court had decided

that the Japanese should be returned, it wou3.d manifestly•

be absurd to give them hunting privileges whereby they

could arm themselves with a 50 caliber rifle to hunt deer

or to give them commercial fishing licenses to fish In

ocean waters. While It Is quite possible the United States

-7-

Coast Guard would have never permitted them to leave port,

nevertheless, the possession by alien Japanese of* commer

cial fishing licenses during var time might have complicated

an already aggravated situation.

In 19^5 there was a large influx of military per

sonnel into California,, The State was practically an armed

camp. Such military personnel were granted the privilege

of sport fishing free of charge. This put a tremendous bur

den on the sport fishes of California. By the same token

such persons hunted virtually at will, and there was simi

lar pressure on the game. At that time also there had been

a large Influx of commercial fishermen into the State (see

respondents * brief, page 5 1 ) and by the end of19*5 it was

very evident to the legislature that the ocean fisheries

were facing exhaustion (see Pish Bulletin 67, page 7} see

also pages 10 and 11 respondents’ brief). At that time it

was clear that If the ocean fisheries were to be maintained

there must be a curtailment in the number of commercial

fishermen.

The brief of the National Association For The Ad

vancement of the Colored People (page 7 ) cites the 19^0 Cen

sus, page 2 , as authority for a classification of aliens ac-

1. Fish Sulietin bj has been lodged with the Clerk.

-8-

cording to eligibility to citizenship. The petitioner makes

the same statement (page 14 of his petition). Our perusal

of that Census does not disclose any ol&sslftcation accord

ing to citizenship eligibility. The classifications are

based on nativity. The foregoing amicus reports at page 7

of it3 brief that there were 33*369 alien Japanese in Cali

fornia in 1940. Assuming for argument alone that there

were only 2,962 other aliens ineligible to citizenship,

the ratio to Japanese would be about 1 to 11. We estimated

that the ratio of alien Japanese to other ineligible alien

fishermen was 89 to 1 1 or approximately 9 to 1 (brief,

page 29). Thus if a mean is taken, It would appear that the

ratio of alien Japanese to other ineligible aliens in Cali

fornia would be about 10 to 1. Therefore in 1945 the leg

islature increased by ten percent (1C$) the number of per

sons ineligible to hunt or fish. Hence it is obvious that

the 1945 legislature took a greater step in the direction

of conservation when it enlarged the classification of per-

sonsAdenied the privilege of hunting and fishing to all

’persons ineligible to citizenship".

Moreover in 1945 it may have been apparent to the

legislature that all alien Japanese were not ineligible to

citizenship (56 Stat. 182; 58 3tat. 827; 59 Stat. 658), and

that it would be manifestly unfair to deny fishing and hunt-

-9-

Ing privileges to an alien Japanese who was eligible to cit

izenship. If a statute is susceptible of two constructions

the one which will uphold the statute will be adopted rather

than the on© which will defeat it (Llndsley v. Natural Car

bonic Qaa Co.. 220 V. S. 61, 78, 79).

In 19^7 the pressure on California sport fishes

and game was greatly relieved by the termination of hostil

ities and by the dispersal of the large number of persons

in the armed forces temporarily quartered in California.

Therefore, the legislature apparently saw no further need

for denying aliens ineligible to citizenship the privilege

of hunting or fishing for pleasure. Hence sections 427 and

of the Pish and Same Code were amended to permit ineli

gible aliens to enjoy the privilege of hunting and sport

fishing. However,the situation with respect to commercial

fishing was becoming worse. As indicated in our brief

(pages 3 1 , 3 2) the number of commercial fishermen had gone

up during the war years but the take of fish had dropped

off until in 1947 the sardine supply was virtually extinct.

In 1947 and 1948 fishing boats were obliged to go from

Monterey and San Francisco to southern California waters.

Hone of the fish packing plants received enough fish to

keep them in operation. Fish were at a premium because

there were no fish. As shown by Fish Bulletin 67 there

-10

are approximately 7^6 eligible aliens engaged in commer

cial fishing in California. According to the petitioner's

brief there are at least 700 alien Japanese who vould like

to enjoy the privilege. Assuming, aa w© pointed out at

page 29 of our brief that the ratio of alien Japanese to

other alien fishermen presumably ineligible to citizen

ship Is approximately 89 to 11 or 9 to 1. Therefore if

all aliens vere eligible to fish at this time approxi

mately one-half vould be eligible aliens and the other

one-half vould b© ineligible aliens. Consequently, it

is dear that denying the privilege to ineligible aliens

California made a big step in the direction of conserva

tion as each fisherman alone accounts for more than

78,000 pounds of fish.^

COMMERCIAL PISHISQ IS HOT ACOMMON OCCUPATION

All the amici stress the rule in Truax v. Ralsch,

that an alien cannot be denied the means of livelihood in

one of the "common occupations'5. They assume that commer

cial fishing is a '’common occupation" but cite no authority

in support thereof other than their ovn conclusions. Web-

1. This figure is computed from Pish Bulletin 67 by dividing

the annual take of fish by the number of commercial fishermen.

-11-

3tor’s International Dictionary, 2d edition, defines the

adjective "common” as belonging or pertaining to manyj

frequent; customary; usual. There are approximately

12,500 commercial fishermen in California out of an esti

mated population of 10,000,000. There are also 13*655

lavyer3 in California. This number compares favorably

with the number of fishermen. In other words, if com

mercial fishing is a "common occupation” so is the prac

tise of the law.

However, Truax v. Raisch excepts fishing from

the classification of a common occupation (McReady v,

Virginia. 90 U. 3. 591).

Pishing is not a common occupation for the rea

son that it is not open to all persons against the legis

lative will or the will of the state because it Involves

the appropriation of the property belonging to the citi

zens, residents of the State (Alsos v. Kendall, 227 Pac.

286).

State v. Catholic, 75 Ore. 367, 1^7 Pac, 372,

also indicates that commercial fishing is not a common

occupation. It holds (page 375);j

. . that before the Fourteenth Amend

ment Is Infringed by preventing one from

engaging in such a business (commercial

-12-

fishing) It must appear that Catholic

had a right to catch salmon which is

guaranteed to and way be exercised by

every citizen of the United States

though a non-rssident of the State.

. . . The business which is protected

from Interference by state legislation

must be a calling vhich any person can

pursue in any place of the United States

as a common, right." (parenthesis and

emphasis added)

In short, the case holds that fishing is not a common

right and it follows that fishing is not a common occupa

tion. This case va3 cited vith approval in Thomson v.

Dana. 52 Fed. 2d, 759, which, in turn, was affirmed by

this Court at 285 U. S. 52 9.

THE CHALLENGED STATUTE IS A

CONSERVATION MEASURE

.The brief of the American Veterans Committee at

pages 6, 7 , 8 and 9 argues that the statute is not a con-

servation measure because the "needs of the market will in

fact be met by the capture of fish by others than in the

restricted class". The reeds of the market have not been met

-13-

"by the capture of fish toy others, There is a greater de-

msxid for the fish than there is a supply. It is urged by

the amici that other measures of conservation such as size

limits, bag limits, etc. have been adopted by California

with respect to the commercial fisheries, and that section

990 which denies ineligible aliens the privilege of fish

ing does not follow that pattern. From a practical stand

point there is only one sure and safe way to oonserve com

mercial fisheries where the fishing is chiefly carried on

toy the use of nets. That way is to reduce or limit the

number of fishermen. It Is not practical to prescribe

a size limit or bag limit on fish which are taken with a

net. When fishermen encompass a school of fish with a

net, they do not know the size or the amount of the fish

until taken ashore and veighed. JHoreover, to count the

individual fish and measure them for size would be Im

practical because by the time the count and measure

ments were made the fish would spoil, Therefore the

only logical way of conserving the commercial fisheries

1 b to reduce the number of fishermen eligible to take

them or to prohibit the taking of them entirely. The

latter course has been adopted in the case of 3triped

bass, for example.

Sardines constitute 75 percent of the California

fisheries and the other fish greatly rely on then for food.

If the sardines are eliminated the other species would soon

disperse and seek food elsewhere. At this time California

does not believe it is necessary to stop all fishing for

sardines. Otherwise it would have done so. However, by

eliminating a group of persons constituting about one-half

of all alien fishermen, the first step in the direction

of conservation has been taken. If It la found necessary

to further reduce the number of persons eligible to take

them presumably this will be done by the elimination of

all aliens, then non-resident citizens and finally by

denying the privilege to everyone..

SECTION 990 WAS CONSTRUED AS A CON

SERVATION MEASURE BY THE HIGHEST

COURT IN CALIFORNIA. THIS CONSTRUC

TION SHOULD BE FOLLOWED BY THE UNITED

STATES SUPREME COURT.

The Supreme Court of California construed Sec

tion 990 of the Fish and Oame Code as a conservation

measure (R. 58, 59). It reasoned that if the legislature

desires to conserve fish and game, it could reasonably

do so by reducing the number of persons eligible to take

fish or game. This idea is not novel. In State v.

-15-

Laavltt, 105 Ms, 76, 72 Atl. 875* It was Bald: (page 879)

"» . . Indiscriminate taking might be

destructive of the fishing Itself . .

. That a state may by regulation

prevent such destruction we think

must be conceded, To do this the

state oust necessarily limit the

times within which or the number of

persons by whom they (olams) may be

taken." (parenthesis and emphasis

added)

The same principle is recognized in State v. Catholic.

75 Ore, 367, lVf Pac. 572, where it was said at page 575

that for the purpose of protecting its fish the state

nmay wholly exclude persons who are

not residents from catching or tak

ing fish in its waters,"

'Ph© Catholic case was cited with approval in Thomson v,

Cana, 52 Fed. 2d, 759* end as pointed out hereinabove,

affirmed by this Soiirt.

Moreover, the construction placed on the cod©

section by the California Supreme Court is or should be

followed by this Court. In Morehead v. Mew lrork. 298

-16-

U. S. 58 7, it was said:

"This Court Is without power to put a

different construction on the state

enactment from that adopted by the high

est court of that state. We are not at

liberty to consider petitioner's argu-

ment based on the construction repudi

ated by that Court. The meaning of

the statute as fixed by its decision

must be accepted here as if the meaning

had been specifically expressed in th©

enactment." (page 609)

PETITIONER CANNOT LIMIT HIS

PISHING TO THE HIGH SEAS

Mr. Takahashi intends to fish on the territorial

waters as well as the high seas. Counsel for Mr. Takahashi

in the companion case of Tsuchiyame concedes that it is

impossible and impractical to fish on the high seas alone

(see pagss 6, 7 and 8, respondents' brief).

If it is impossible for Mi*, Tsuchiysma and the

200 Japanese fishermen in whose behalf he sued to limit

their activities to the high seas it is equally impossible

for Mr. Takahashi to do so. Mr. Takahashi virtually con-

-17-

coflea this in his brief by Indicating that th© fish and

the fishermen pay little attention to the three-mile

territorial ocean boundary line (see page 1 2 ). Jloreover

his brief disputes the allegation of his amended petition

that h® fished on the high seas since 1915 (Cf. R. 1 and

6 and page 1 1 , petitioner's brief).

As It is impossible for the petitioner to limit

his fishing activities to the high seas and as fish taken

on the high seas are indistinguishable from fish taken in

territorial waters (Bayslde Fish Flour Co. v. Gentry. 297

Ho 8 , 422), it follows that the doctrine of sovereign

state ownership is applicable here. Counsel for petitioner

concedes that he cannot "limit the issues . . . to the right

to fish on the high seas" (see respondent's brief, page 8)

in the companion case of Tsuchlyama v. Pish and Gam© Com

mission (K. 26) and It is again urged that the same limita

tion Is applicable to the case at bar.

Although not cited in petitioner's briefs, ref

erence was made by his counsel during argument to the oase

In re Ah Chong. 2 Fed. 753. That case Is also cited

by some of the amici. That cas© is discussed in the main

opinion of the Supreme Court of California (R. 41). That

case was decided in 1880 and Is superceded by Geer v. Con-

-18-

nectiout, 161 U „ S. 519 (1396), Lubetlch v. Pollocks 6

Pod. 2d 237 and others. Moreover, the Ah Chonre case ap

pears to have been superceded by Terrace v. Thompson.

263 U. S. 197 and allied cases holding that eligibility

to citizenship furnishes a reasonable basis for classifi

cation by a state. In the Ah Chong case the court re

viewed several statutes of California and section art

icle XIX of Its Constitution which singled out Chinese by

name. The Tenth Census of the United States showed no

miscellaneous group of aliens in California. The only races

disclosed were persons hailing from British America, Eng

land and Vales, Ireland, Scotland, other parts of Great

Britain, Germany, Prance, Sweden and Borway, Mexico and

China. The Ah Chong case turned on two other points,

namely (l) that th© statute would preclude Caucasian women

from fishing because they oould not become electors and

{2} that the statute violated the terms of an existing

treaty between the United States and China. The Ah Chong

case went no further than to hold that if one class of

aliens is permitted to fish the same privilege must b© ex

tended to all aliens who are protected by treaty. Said

th© Court:

\

-19-

"Conceding that the State may exclude

all aliens from fishing in its waters,

yet if it permits one class to enjoy

the privilege it must permit all others

to enjoy, upon like terms, the same priv

ileges, whose governments have treaties

securing to them the enjoraont of all

privileges granted to the most favored

nation." (2 Fed. 7 3 7) (emphasis added)

PETITIONER DOES MOT PRESEHT

A RECORD WHICH SHOWS HE CAM

BE AFFORDED AMY RELIEF

The amici as veil as the petitioner ask this

Court to reverse the Supreme Court of California. Pre

sumably in making such a prayer they desire the petitioner

to be licensed to fish commercially without limitation as

to place vhere the fish are to be taken. This, however,

cannot be done on the present state of the record.

The amended judgment of the trial court com

manded the issuance of a commercial fishing license with

out qualification as to place of use (R. 21). That judg

ment was made after the trial court lost jurisdiction and

Is void (R. 33). The invalidity of the amended judgment

-20-

: conceded by petitioner in. oral argument. Moreover,

.' a-landed judgment gave the petitioner more than h©

asked lie only wants a commercial fishing license "to

engage in commercial fishing on the high seas'* (R. 6).

That Is the substance of the prayer of his petition, as

amended and that is what he got from the trial court

(R. 7). The respondents cannot issue such a license in

the absence of legislation providing for a license in

such form. Moreover, they could not endorse across

the face of a license (as suggested by petitioner) that

it is good for fishing the high seas only without vio

lating their oath of office and the statutes made and

provided. If the Supreme Court of California is reversed

the respondents cannot comply with the original judgment

of the trial court until the 3tate Legislature amends the

statute and provides for licenses in the form which the

original Judgment directs. Until that time, the original

judgment is in effect nudum pactum. Hence all issues,' ex-

cept the issue raised under this point, are purely abstract

and hypothetical.

Respectfully submitted,

PISffiD SL HAWSER, Attorney Oen-er 3T

DATED‘.APRIL JO, 19^8

v. iscmr^mw- ■

Attorneys for Respondents