Order Dismissing Motion

Public Court Documents

May 11, 1995

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Order Dismissing Motion, 1995. a2b615ca-a846-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f39e48d3-3daf-42c9-802c-0f0b37ebfbcf/order-dismissing-motion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

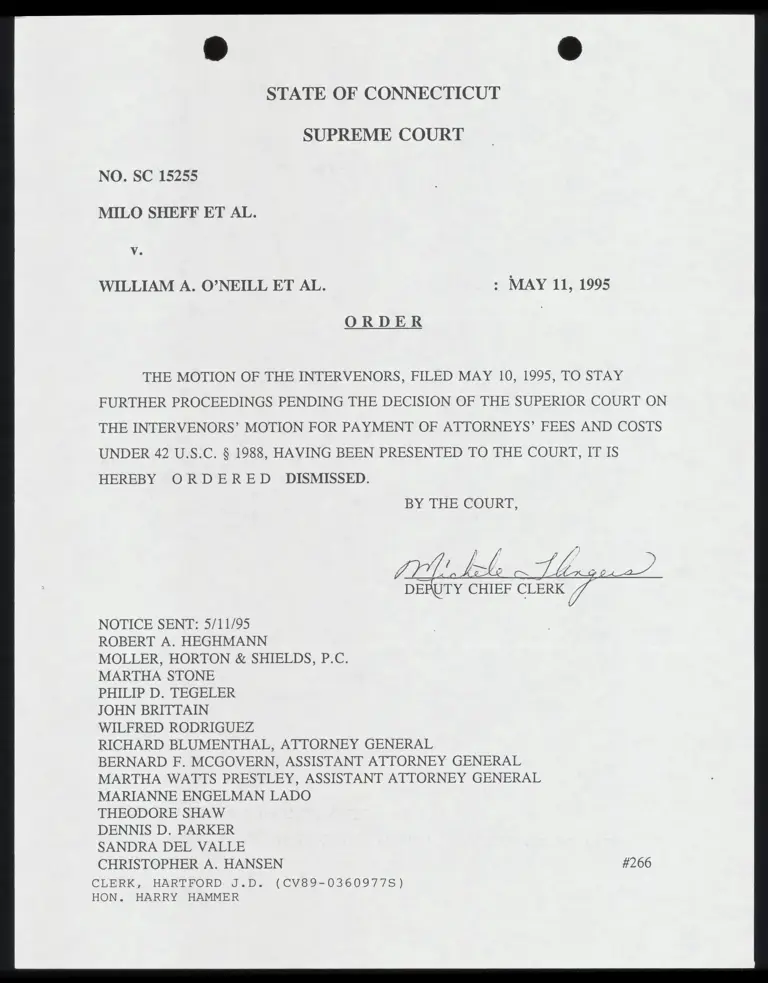

STATE OF CONNECTICUT

SUPREME COURT

NO. SC 15255

MILO SHEFF ET AL.

V.

WILLIAM A. O’NEILL ET AL. : MAY 11, 1995

ORDER

THE MOTION OF THE INTERVENORS, FILED MAY 10, 1995, TO STAY

FURTHER PROCEEDINGS PENDING THE DECISION OF THE SUPERIOR COURT ON

THE INTERVENORS’ MOTION FOR PAYMENT OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND COSTS

UNDER 42 U.S.C. § 1988, HAVING BEEN PRESENTED TO THE COURT, IT IS

HEREBY ORDERED DISMISSED.

BY THE COURT,

rf dole opera? yr ¥i AO (Ko Gin es nn

DEBUTY CHIEF CLERK

NOTICE SENT: 5/11/95

ROBERT A. HEGHMANN

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

MARTHA STONE

PHILIP D. TEGELER

JOHN BRITTAIN

WILFRED RODRIGUEZ

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, ATTORNEY GENERAL

BERNARD F. MCGOVERN, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARTHA WATTS PRESTLEY, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

THEODORE SHAW

DENNIS D. PARKER

SANDRA DEL VALLE

CHRISTOPHER A. HANSEN #266

CLERK, HARTFORD J.D. (CV89-03609775)

HON. HARRY HAMMER