Congressional Record H6937-H7010

Annotated Secondary Research

October 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Congressional Record H6937-H7010, 1981. abda116a-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f3a7b201-88c8-49b1-8ccf-9d548f26a2eb/congressional-record-h6937-h7010. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

) btobr 5, lgEl CONGRESSIONAL RECOR"D - HOUSB

v.\ .J

H 6eir

t

;

Ii

:

I

t

I

I

i

t

I

a\

b

{

i;

i.

Shrt thb body woultl rcrect thc noUon pllcd for ,ob. got ,obc rnd 9(X) morc {, ancserud "pre8ent" l, not rottnl ?t,

of an experulve, ner &ructure for the tndlvldualr got thcm on thetr owr" es followr

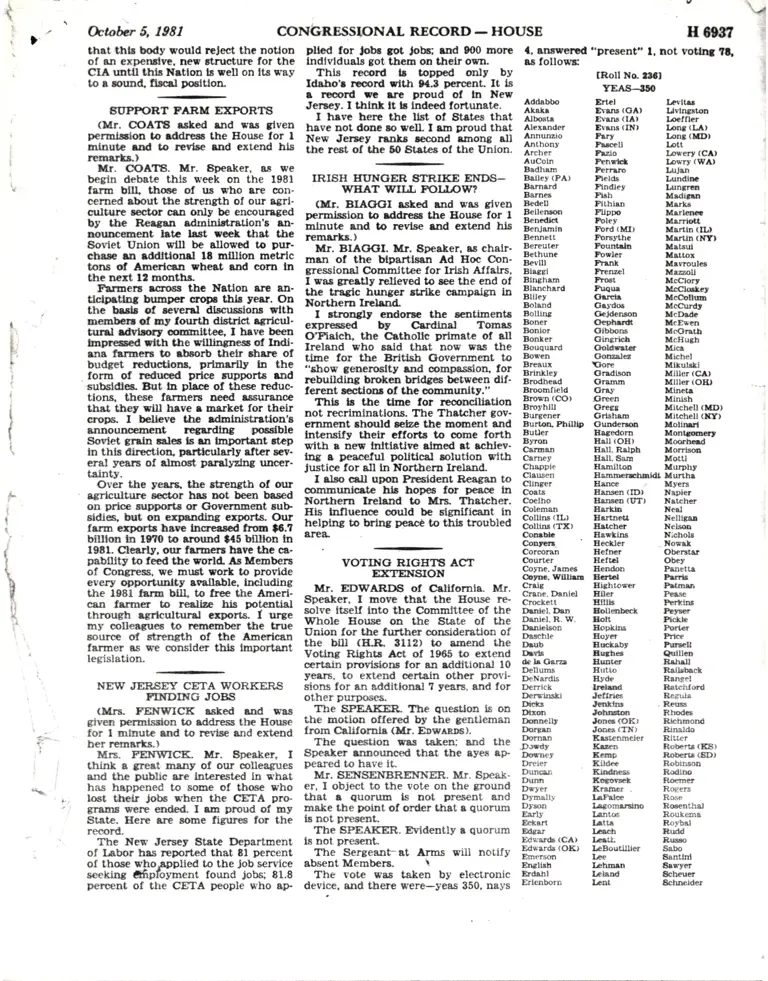

CIA unUl thl,r Nrtlon lr sell on lts way Thls reootd b toppe<l only by tRoll No ttlltoepun4g yg'ffiI**r*iL%*il1 Il"5 rEAH'o

BupFoRr FARu ErpoRrB. '1TI;]?S ff [$T';*Hf;, iltr Hftl*1, H#f(ltr. GOATB esled rnd rrr SlveD hgve not donC rO well I 11a Drogd that liex-aor Dr.us (rN) r.ons (r.A)

permlrrlon to rddrec the_Eouce lor -l New Jersey nntr recond

-rmorU all l*.-"plg Fuy Lon3 (xDt

mlnute .Dd to rtd!€ lnd ertend hls trri reet of

-ttre

60 6ta1es o:t trre-Uiro.r l#X:|, mu il11"o,"^,rernertr') r

-

Aucotn FehrB r.sry(wA,Mr. COATB. lf,r. Bpeaker, ar we

-

Bsdh&m Ferrrro l,uJ8n

be8in debate thls week on the t98l IRISH EITNGER S|AI?rrE! ENDS- Blttev (PA) Pteldt Lundlr

fr.rE bul thce of us wbo rne son- WEAT WILL FoIJ.Ow? **Y f,lno'", H*:Heerned rbout tbe rtrength ol our 88rl: (Ul. BII|OOI rsked end sas glven B"a;r Frrhrrn lrsrks

culture rector cru only be encounSled permlcslon to rddress tJre Eouse tor t Pglt:I=l Fuppo MrrtelE

by ttre Rercrn adminirtratlon o ,rn- fiGutc rnd to revrse raA extend-iG ffftffi. *]ir,rr, ill[l**,Douncenent lrtc ltlt r-eek -ttrgt tbe remerfg.l Benne* rbrslth€ urr,tr(Ny)

Eovlet Unlon wtu be }qofts to pJ,rl - -ur. areool. Mr. Epeater, ar chetr. P:11y.!'1 nounteln -;t""r

c-lr8se tn uldltlonrl l8 rllbn Eetrlc *----J-+L-^;i--*i;:-;;-'tr--;;_ Bethun? Foslcr xatlor

toruorAmedcaa,oS"fffi#fTf *R;tlJ5m;,^*m,m: ffft," ffi, tgt'*tlre nert 12 mouthr.Fennerae.oss*d$:i&H -f"#tr*H*": ilHil m*" ffiFttclDrtlDt bumpct crq

the berlr ef rvenl ,

memDcrror qv rourtb^dldrtst^g,t* eiruoea- - uy crrarnar -Eornrs YT:_ od,hr,il xcE*.*en

ffi"ffiffi"Pfiffi| g;igi;*"i?j",*,,#"*]',S ff;;'il LryH" [Hr#rns frmers to rDsorb.the[ {rre^-of ilie fo" Ure arittsU Ooveranegt to sori" oonltc, Michel

tm,*ttJ",,i"Xffi,H$ffiffi#;!*,ffi?ii,;ffi*," gfr" gii&,rubsldlea But h plect

rff.rlH,'ffi:TffilEffi dHeffi,ffitrffiy# ir*n*_ En"t xlffi,*crops. I belleve ttre

announceocnt *8tl*3!-lflb^t: t't"*11v tJrelr cifortr to E-e -iortfi luuer- - rageaorn M;t o'€r,

ffn"*ffiff&&ffi#"sx ffi,3kqffi"",* ffi gilE" gffieral years of rlmost D

13.11; *" reara !,"e"g;1g-.1.;5 jffigy*'mg;*"ren $H:l Effif-$JHjagrlculture secior tus

"1t'**ee""'"'Hffi Hffiffi ffi*, m*' $ffi

stdie6" but on exfadi

frnn exportr have lnq

btlllon h lYI0 to rrou

rgEt. ctearly, our frrmen heve tlrc ca. .

-

Hffi EHi' 3g:Sr*

pablllty to lecd the world. .Aa Memben VOTING RIGETS AcT courtrr_ Il.ft l obey

of Consress, we must sort to provlde ErrENsrON B#!:*fif;- EllS" moeverv opportunltv EeuHtiJ$ffil

^Dtr.

EDwAn,Ds or cerro*rta. Mr. #;;; Elf"l'-- #g*the l08l faro btll to

cen termer to "u"yo-f,i"-ioffiii"r

Speaker, I move that the Eous! 1e- c;;;ii*' Emb Ferrtnr

ffiffi#r-fl'ffssffi+*: ffiifr ffi ffi;rermer es we consrd"" tilG r--i5ii-,i l["*['.[H'rf,1'3] lfo . exrend o.vts Er'r"" eurueDlegislation'

_ certain provtstons for an "iaiiio,iJlo *^f.S--" auuter R.tdr

: - yeers, tb extend ertain ottrii i-*;i: *li:H" Hlf B:l?Y-

NEW JERSEY CETA WORI(EA,S sions for an additlonel ? years, and for D€rr,ck trd.d Rat hrord

FINDING JOBS other purposes. rren'lnski &frri{x R€sula

(Mr6. IIENWISK rsked and was -The SPEAEER- TLe questloa_ts on ffi ffi *f.*

given perurlsdon to rddress 0he Houee the motion offered by the gentleman Ddrneuy Jona (oK, Rbhmond

ior t mtnutc a,nd to revise and extend from Califonrle (Mr. Eoweam)' Dorgu JG(TN) Rineldo

hertcmarts.) The question Eas ! ken; and the trH Efn*du' Elfft,ru,

Mrs. FEIfWICK. Mt. Epeaker, I Speaker ennounced that the ayes 8p- -p"r."I'v Ecup noberr. (ED)

thinl B 3reet prny Of OUr COlleagUeS peared to have it. Dreier Eilde Robimon

and tJre -public ere'lnterested in i'trat Mr. SE}{SEL{BRBINER..yr. Sneax; BXH' *HS ExH:',

has happened to some of those who er, I object to the vote on the gound 6;;;r K,a,,'! Rorers

let ttreir .lobs wben tJ.Ie CEIA pro- ttrBt i quoruE b not present and Dl'In8llr t^fblce Rcse

gra'Its were ended- I rm proud of my meke the potnt of order that a quorum ilTrl ffi** ltr*'jlStat€. Ilere erre Bome fiSures for the lB not present. Eckarr rrttr Rol,bar

record. The SPEAI(ER. Evidently a quorum Eluar I-..ch Rudd

Ttre New Jersey StBt€ Department lsnotpresent. Edv'8tds(cA) IatL lr'ts

of r,abor basrepo-rted ttrai ai percent -The sergea.nt-at Arms will notify **:8rlH(oE' LeBoutil'ller

*H,n,

of those who,applled to the Job service absent Members. ! sng6n r-€h,rn sr*,er

seekiru Cfipfoyment found jobs; 81.8 The vote was taken by electronic ryq+l blsnd scheuet

per^eent of itre CETA peoplC who ap. device. and there were-yeas 350, nays Erlcnborn r'nt schmids

:.

1H 6938

&hrlGdcr Epcnct Wcbcr (OIt,

Echulra gt Ocrodn Welrs

Echumer St ntclrnd Whlte

Sclbcrunt Etrnton Whltehurst

&rucnbrennrr Slarl Whltley

ahuilruIy Strton Whlttrlcr

thrnnon Stenholm Whltt n

ShrrD 8toke. WUson

Shrr Strattan Wlnn

Etrclby Stud& wlrth

thummy Stump Wol,

thuster Syngr WolP€

8lmo6 Trlble WortleY

S\ecn VrDder Jrgt Wrl8ht

ELelton Vento Wydeo

Smtth (AL) Volkmer tylle

SEtth (lA) WrlSren Yst€s

Smith (NE) \trrclter Yotton

Emlth (NJ) Wsmpler IounS (AK)

Smlth (OR) W.shlnaton Youna (fT,)

Amjth (pA) Wstti,s yerrng (IUO)

Snosc Waxman ZablocE

Enydcr Weaver Z€terettl

Solomon Web€r (ttN)

NAYS{

Oooduns Jelrords ltcDondd

Ja.obs

ANSWER.ED "PRESBTT''-I

Ottlnger

NOTVOTING_?8

AndeBon Dlngell lfoort

Andrcs6 DoughertY O'Brlen

Applegat Edrsrdr(AL) Oatar

Ashbrool bery OtleY

Arptn Evsn8 (DE) hsbaYBD

Atllnron Fledler Prtt

'l!ooBsIsIlB Florlo Psuf

BaUey(UO) Foguett PcPDGt

Besd tlord (TN) Petrl

Boca! Ollrnso Prlt bsrd

Brool! GtnD Roe

BrilD (CA, CucIE.D Rct Dlor'lH

Bror! (OE) Ousrln! Rotb

Burton,Johtr Eouand Rouss€lot

CaEpbell EortoD sevr8c

Chlppcu Bowsrd siusoder

Chency Eubbord Sole,tr

ChlsholE Jon€s (NC) 6U(t

Cluy lrrl! Tbut€

Conta [ArLeD T3udn

Coughln ld.rtey Trylor

Crr.DC, PhiID Df,lrtin (NC) ftromrs

D'Amour! XcEirurey Itlxler

DaDDeEeyer _ lllo!f,ley Irdrll

Dect$d Xoffett Wllltril (!fT)

DlctlDsoD lollobrD WiUiaElIOB)

tr 1230

Mr. EENDON changed his vote frpm

"n8y" to "ye&"

So the Eotion was egreed to.

The result of the Yote was an-

normced as above recorded.

Ttre SPEAKER, pro tetnpore (Mr.

Morrcomv). The Chair requests

that the gentleman from California

(Mr. BErrrnrsoN) a.ssume the chalr

temporarily.

IN THE CIOIIITITIEE OI TIIE WEOLI

Accordingly the Eouse resolved

Itself lnto the Committee of the

![hole llouse on the State of the

Union for the further consideration of

the btll, E-R. 3112, with Mr. BEU.EC{-

soN, Chalrman pro temPore, ln the

chalr.

The Clerk read the title of the bill.

trr 1245

T'he CEAIRMAN pro tempore.

When the Commlttee of the Whole

rose on Fdday, October 2, 1981, 8ll

time fonFnbral debate had expired.

Pursuant to the rule, the Clerk will

read the substitute committee amend-

ment recommended by the Committee

on the Judiciary Dow prlnted in the re-

!

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE

portfd blll as en orlglnal blU lor ttte

purpNe of amendment.

The Clerk read a6 follows:

Be {t ctl?4kd, W t,c Senote and, Houe of

Rcpreseatatloa al thc Unltztt Stotzt ct

Anurlco h Cononu a.seerflbl/,4 T'lrat rub-

lectlon (a) of Bectlon I of t}te Votlru Rtghts

Act ol 1006 E emended by atrltlng out "!ev-

enteen year!" crch pl8ce lt eppeara 8nd tD-

sertlna ln lleu thereol "nlnet en yerrB".

(b) E fectlve on and rtt€r Awust D, 1084.

EubsectloD (!) of loctloD a of the Votkul

Rhfits Act oI 1905 ls amended-

I I ) by lrucrtlDs "( I )" att r "(a)";

(2) by lnscrttng "or ln any Dolltlcal subdl-

vlElon of such Stste (as auch subdlvlBlon cx'

lsted oD the dstc such detemlnatlonf werc

m8de slth respect to such Etate), though

auch detctalnatloa! were not nede slth !G'

speet to nrch tubdlvlslon a3 a aepsrata

untt," before "or ln rny poltucel gubdlvlslon

rrtth respect to rhich" each Dlrce lt r&

De8r8;

(3) by strttlng out "ln en rctloa tor r de,

clsrstory ,udg@ent" the ttrst plece lt .P

pears and rll tJret lollowg throwlh "color

through the use of mcb teetr or devlca

have occurred eDyvbere lD t&e t€rttory ol

such plalnttff.", tnd lnsertlng ln lleu thereof

"lssues r declarstory ,ualgment under t'bl,s

8€ctlon";({) by gtrlklng out "ln an ecuoD lor r de'

clartot, fudgEent" the BccoDd plr.e lt sp

p€Brs and ru th8t followa through "sestlon

a(fx2) tbrou8h the us€ of t€cts or devlocs

bave occurred eaywhere tn the terrltory ol

ruch plllrtltl,",.nd lnsertlng ln lleu tbereol

tJxe fouosllIg:

'lssuer a declsntor" fudsnent under ttrl8

sectlotL A declaratory ,udginent under tblr

aectlon elrrll lssue only lf such court detcr.

mlnes tJrrt, durtng tJre tcn year8 precedlns

the flfhg ol th€ &tlo!r" end durlns tlre

pendeaca of such rctlon-

"(A) no eirch test or devlce har Deen used

rlthtn suc.h Ststr or Douucal tubdlvldon lor

the puDose or rlttr the elfcct, of d,enylng or

a,brtdgrng the rlsht to yotc on $couttt ol

raoe or color or (lD tlre esc ol I 8t8t€ or

gubdlvlslou seekhg r declaretory ,udStrent

under tlre lecoDd seDt€rrce of thl lubsec-

Uon) ln coltravcDuon ol thc susri,nte€. ot

Bubsestion (txz):

"(B) no llnal Judpent ol a,ny court of the

United Ststes, other tha,i t.llc <tenlal of de,

claratory ludgent under tbls scstton" has

determlned tha,t dentrh or sbrldgemeDts of

the rlght, to got€ oD lccoutrt ol nce or color

have occurred snyrhere b the t€rfltory of

6uch St8te or polltlcal subdlvlslon or (tn the

case of r 6tctc subdlvlslon seeklng e declar&

tory Judpent uDder tJle sccoDd seDt€nce of

tJrtg subsectloD) that deul8ls or abrldge

nents ol t&e rlSbt to Yote ln contnBventloD

o, the nrara.Dtee8 ol subsectlon (fX2) b8ve

occuned anywhere lD tJxe t€rrltory of such

Etat€ or subdivl,Bion a,Dd Do con8€nt decree,

settleneDt. or agreenent h8s been entered

tnto resultlng ln eqv ebandonment of a

vottna ptrctice challen8ied on such grounds;

and no declarstory ,ualsDent under thls 8ec-

tlon ahall b€ ent€rbd durlng the pendency of

an abtton allesing such denlals or obridge-

ments of the rtght to vot€;

"(C) no Fbderal exanlners under thls Act

have been asslgned to such State or political

subdivision;

"(D) such Stste or polltlcel subdlvlslon

end all governmental unlts slthln lts t€rrl-

tory have complied sith s€ctlon 6 o, thirB

Act. includlng compliane€ crlth the requlre-

ment that no change @vered by rectlon 6

has been enforced slthout preclearance

under seetion 6, end have repealed all

changes covered by Eection 5 to which the

Attorney General has successfully obJected

or as to whtch the United Sretes Distrtct

October 5, 1981

Court lor the Dbtrlct ot Columbl. hes

denled r declantory ,udgment;

"(E) the Attorney Oeneral has not lnter-

posed lny objectlon (that ha! not been over-

turned by a fln8l Judgment ol r court) snd

no declaratory tudgment has beco denled

under rcctlon A. vlth rcsDect to sly rubmls.

rlon by or on behelf ot the plalntlff or sny

goveramental untt dthtn lt! t€rrltory under

lectloD 0; end no ruch ,ubmlsslonr or de-

clarBtory JudSiment actloru are pendtnSi; and

"(F) such 8t8te or poutlc8l rubdlvi:sion

tnd ell liovetlmentsl unlts wlthln lts t€rrl-

tory-

"(l) have sllmlngt€d votlng procedures end

Dethods ot electlon rhlch lnhlblt or dllut€

equa,l access to the electoral prcoess;

"(lI) hovG cngaged ln constnrctlve eflortr

to ellmlnrta tntlEldatlon rnd herasrnent ol

Deraons ex€rctdng rlghtc Drotectcd under

tDlB Asi; .nd

'(lll) bave cmss8ed la other conatruettve

efforts, ruch es cxpsnded opportunlty for

conveulent regirBtratlon and votlng for every

geraon of gotng eae and the rppotntnent

sf mlnet'lty p€rsoDr as electloD ofliclals

tlrroutihout the turlrrllctloD and st tll stsges

ol the electloD a,nd reglctratioD prooes&

'(2) To arsl5t tbc-court ln determinlng

rhether to lirsue r declaratory ,udameDt

under thls anbcoctlon, tbe platntlff shall

pres€ot cvldeoce ol hinorlty participstlon,

lDcluding cvldcnce o, tbe l€velB ol mlnorlty

Sroup reSilalrstloD rnd votlng, changes to

such levels oyer Ume, aotl dlsparltles be-

tween nlnorlty{roup rnd DoD-mlnorlty-

Sroup partlclpatloD.

"(g) No declrntory ,udsEeDt ahall lrsue

uDder thrR slrhctloD vltn recpect to such

Etate or polltlcal nrbdlvldon lI cuch plain-

tlff an<l toyenueDtrl rrnlfs vltfua tts terrl-

tory hcve, durlns teG pertod beclDnfng tan

years before tJre dete the fud8oent ls

bsued, cogaged h vlolatlons of roy provl-

don ol the Coactltutlon or lrr! of the

Untted Strt€! or eny &rte or polltlcal erb-

dlvlslon rlth rcgpect to drrcrlmlnatlon lD

yotlng on lccouDt or raoe G color or (rn the

crse ot r Btete or rubdlvLlon reelhg r de'

clarrtory ,ud3qncDt uld€s thc EDd acD-

tence o( thls rubsectloD) ln contnvcouon ol

the lurlaolees ol rubectioo (fx2) unless

tJre plalntllf eata,blhb€s that 8Dy suctr vlola-

tlons wer€ trlvlsl were prompuy correct€d,

a,Dd tlere Dot repeatad.

"(a) Ttre Etste 6r Doltical cuMivision

brlngtng cuch rctlou ghdl publlclze ttre lD-

tcaded comnenccEeDt $xd r,qv propeed

lettlemeDt of cuch ictlo! tn the neda sen-

tD8 suc,b Etate or polltlcal nrulvtslon end ln

apprcprlate Unltcd St8teE pgt offic6. Any

aggrleved party Ery lntcrrene rt 8qy stsae

ln luch rcuon ":

(5) tn fhe second panfra,Dh-

(A) by lnsertlng "(tf' before "An action";

and

(B) by Etrlking out "flve" end Bll that fol-

lows through "section (lX2).", 8nd tnsert-

lng ln Ueu thereof "t€n y"ars after ,udg-

ment and shall r€open the action upon

EotioD ol the Attomey General or any ag-

grieved perBon alleednS tJlat conduct h8s oc-

curred rrhlch, h8d thst @nduct occurred

durlng the t€n-year Deriods referred to in

thls Eubsection, would have precluded the

lssu8nce of a declaratory ,udgment under

this subsectloD."; and

(6) by strtkinS out 'If the Attomey Gen-

eral" the first place lt oppears and all that

follows thro-uah the end of euch subsection

and inserttns ln lleu thereof the following:

"(6) If. aft€r tso years from the dat€ ot

the filing of e decl.rstory JudSiment under

this subsection, no dat€ has been set for a

hearing in Buctr &cton, and that delay has

not been the result of an avoidable delay on

the part of counsel for sny pslty, the chlef

i

I

Oetobr 5, 1981

,udse of LtrG Untt d 8t ie. Dlstrlct Court

tor thc Dbtrlct of colrhbli rD(y rcquest

the JudlcLl Coumtl for tb. Clrcult of the

Dbtrbt of ColuDbl,r to provldc t&e ne&

erry Judlclrl nr.ouroe. to crpedlt rny

rctlon llled uo.ler thL retlon U errch re

aouloa3 rtl! unrvrllrblc wllhln tbc cdlcurt"

tbc elhicf lu<lge rhrlt lllc r.ccruflcrt of nG'

cc!6lty b ecoordrnoc rltb rctlon 202{d) of

tttle 28 ot ttle Untted Etates Code.".

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE

ane exagSierrted" Ttrere rre Federal

rules thrt prpvlde thet cults could be

dtsmlssc{ npldly, rlth rttorneys' tees

srsessed lor the party rho tlled the

sult.

There lre no cucb cases nos end we

cennot lnrdne lt to bc a great denger.

However, lt b of oonoenr to rome of

our oouerf,Ue! rnd rc I heve lntro-

the Utlgatlon ou the ballout ttself-

wlll not act rs e bar to the ballout.

Bowever, tl the estton ltsel, ts 8u@ess-

ful, rlter t.he Jurlsdtctlon lc brUed out,

then tJrere b ea automrtlc recapture

and ttrc Jurladlctlon lr once rgaln oub

I do not loow of ar\y obrectlon to

thlc a^mendvrent, Ur. Chalrman.

lD all other fDstanc6, recaptur

would lsrnnln ylthlD tJre dlscretlon of

the ourt'

I believe uly rhenal6ent ls g work'

able solution to thlg problem and I

ul8le you to support lL

Mr. ErDE. Mr. Chetrman, I move to

strlke the requtdte number ol rords.

Xr. Chdrmen, I a,m not gotrs to

obJect [p thh rmendrnenL It does

rnrke t[s dturtlou slisDW bgttcr, but

It doea not c}irlfy t&e rerloui problem

tnvolvlDg coomt decr€e& The prob

lern !r thet consent decrees are ofte5r

entered to buy pecoe. Aexeem€nt 18

reaChed rnd rather thgD dtRrntfs t[g

caae, ar tlroryh tJre clatm were rlth-

out Eerlt the Derttes agree and au

order b entered ln tbe nsture of & con.

seut dectee but the coDsent decree

me5r not ldnlt llrbllty. It may be on e

Drtt€r thrt b not tunda^aental or ln-

portr.nL Ad lt eeems to me that the

court bearlns the batlout ought to

have dlscretton to loot et the consent

decree to see wh8t led to tt. wh.at was

the rstlonale, wbrt ses the problem

compla,lDed ol' ud tbe correetion

nbde.

I want to see mrrimum discretion in

the court ro tJret r bcllout is not frus-

trated on r teehnhellty.

Now, I rlII not personelly-I do

know I elnnot speat for other mem-

bers of the comnltt€e--obJect to the

nmendment of the gentleman from

California" hut I will ln a moment

offer ao rmendnent that I t&ink fuIy

coveris the slturtlon-

Mr. RAILSBACK. llr. Cbelrman, I

move to strile tJre rcqujsite ntrmber of

words.

(1f,r. R.AIISBACK esked rnd was

gilverr permlsglon to rwlse end extend

his remarks.)

M!. RAILSBACK. lf,r. Chatrman"

last Ftidsy I was not able to be pres-

ent. f was back la r.y Ststa of Illlnots.

But I have been very much tcterested

ln l,hls particular blll r,nd I want to

beClD by rlmply saytng thst tn my

Juttgment there hrs been e tremen-

dous amount of sork done by the

members ol the zubcommlttee.

I 81ve a Sreat deal of credlt to the

chelrman" the gen&leman from Califor-

H 6939

nll (Mr. EDwAnr), end I belleve thtt

the ranklng mlnorlty member, the

gentleman lrom lDtnols (Mr. ByDt)

has done yGonra,tr vort along wlth the

gentleman from Callfornta (Mr. Lur-

cRE) lrld tlle gentlemrn from l[lacon-

sln (Mr. CirrcsEcaarrwrn) rnd tJre

members of the meJorlty ol tbe rub,

committee.

In my oplnloo" I oonaeDtu! har bcen

reached thrt there rhould be lndeed

aD cxt€nslon ol the Votlng Righte Act

and ttrgt tbe extenslon etrould be cou-pled ylth r re.sonrble bellout to

penntt Etrtea rnd county aubdlvlslons

to reek r declrratonz,udexaent thst

would rcleu€ tiem from oovera,gie

under aectlon 6 of t&c rct lf tbey can

meet certeln condlUonr.

Now. we cen quetrel rbout whet on-gtltutee r rcrrona,ble h,llouL but re

csaDot qurrtel rbout tbe need lor ea

exteordou of the rct ttrelf. nor ctn ?equrrrel rbout tbe eDor.rDous beoefltr

Setoed by btsctr, Elgpanfca, or rqy of

those rho hrve been dbcrimlnetad

agsinst h the clectoral proces6, tor'J

thlnt when re rctd tlre record there

have been trenendour atrtdes.

Prlor to the pssage ol the rct ln

1965, the pereentaae of blacE resls-

t€red voten lrr ttre now overcd St^Btes

was 29 pcrcat rblle rcdstratton for

whltcr c/81 ?l percent. Tbdry tn many

Ststes covered by the ect, morc than

onerhrlf of the ellgrble black cttlzens

are regtstered end ln rome Stetea tbe

fleure ls eveu hlgher.

1 mlght fust mention ln ondderlng

the statlstlcs that beve been made

Bvallable to us, tJrer,e ere nor Ersny

covered Strtes thd ere dolng I Euch

bett€r Job than somc ol our Northern

Ststes. I personally have been lnllu-

enced la addttlo4to my past suppoft

for t&is klnd of legislstlon to strongly

support rn extenaioD of the Vottng

RlSbts Act by conversetlons and meet

lrUs tttat I hove had wlth thce mem-

bers of the clvil rleihts communlty sho

have tn the past been tn the forcfront

of worklng to eombgt dlscriminstton lD

the eleetorel process,

In eddltion to tlre few examples of

problems ttrrt heve been clte<L these

people hrve expressed to ae thetr

genuine oonoern rbout perDlttlng the

Vottng Rights Arj,, tD explre. I em ln-

fluenced by the fact thst the thrce Et-

norlty members of the anbemmlttee,

includlng tbe ranklng mtnortty

mcnber, tbe gentlemu from Illlnois

(Mr. IIyDE), vho, I belleve, et oue Ume

had reeernrUons a^bout erteodlng the

act without nationallzing tt The fact

that he has hrd the coureSe to reverse

his orisinal stsace rnd llog' is bsstcsuy

supportl.ng en extenslon of the Vottne

Rithts Act lends lmpetug to my rup.

porL

The lct was orl8lnaDy destgned toprovlde lwlft admlnlstnttve rellef

where there sras coBpeltlng evtdence

thet rsclal dlscrlminattou plagued tJre

electoral prooess, thereby denylng mt-

norlties the rlght to effectively exer.

cise their franchise.

lllr. EDWARD8 of Calllorlne- lf,r. uced thlrl amendnent.

T'lrls emendment makeg lt cleer thatChetrme,n, I ltk ttnrnlmou!

thst tlre rectloD be consldered rr reed,

prlnted h the Rrcona, rod open to

elnendnent at any potnt.

The CEAIRMAN pro temporc. Is

there obJectlon to the rcguest o, tbe

Its fued dudng peardmey of the ball-

actlon-durlng the pendency of

gentleman from Callf ornla?

Thore wes Do obJectlon

AIIIIDIEIO''ED

'Y

E" TIIFAID' C

CJTLI'IOI'LI

Xr. EDWARDB ol Callforala. Er.

Chelrmln' I olfer rn rnenfuenL

The Clert reed ea lollowr

Ancadment oltercd by Ir. EryaE of

Ctlllornl*

Pr8r 5. UDa ?. hr€rt "comeoced beforr

the mhsf ol in utton undcr t.bls -ctlonend" efter "pendency of sr rctton".

hse C, ltne 6, lnrri rftar tbe pcr*od but

befor" ttre clc quotrtloD Etrt thc lollow-

lng

The eourt, uDoD anctr reopcnln8, rbrU

vrcatc thc declrntory fudjment lned

under tbL rcctlon lf. dt4r rhe lrutre of

Buch &lrrrtor, ,udSEnt r lhel Xrdg-Elrt .Srlhrt tbe Etrlc a xrbdlvldm vltlr

r€spect to sbic,h f,rcb d€clr.rdory fudgmentwlr llsrcal or rgrlnst t.EJr goyerDmental

unlt plt&In tlLt Strt or subdlvlsion, deter-

mlDcs that dcnf8Js or rbrirrSeneDts of the

rlsht to *ot€ @ aEou.at of raoe or @Ior

hrve occurcd tnyshel? la the terrltory oI

sucb Stste or polltlcel .ubdlvlrioD or (h the

case of I Stste or Bubdhlslon shich so{rAht

s declar8tory ,ud@ent uder Lbe second

EeDt€rroe sf thtr rub8ecuou) tbrt d6l-1. or

abrl@eoentr of tb€ rtbt to vot€ lo contn-

venuoD of the 8urrrlt€a ol srbcectlon

(lX2) have ooeured rnlrsbere lD tb3 t€rrl-

toly ol &rch Strf€ or rubdlvldon, or ll. atter

the i6s rrprre ol ruch decla,nfory Judglent,

a coDs€Dt decree, tsgUeDent" or aSrecment

hrs beeD enter€d lDto resuldhlt ln rny abrn-

donherit d e votlng prrctice shrrlspg6{ qn

Buch Srounds.

Page {, line 22, lnsert "or" aft€r "ln thE

case of r Stst€".

Mr. EDWARDS of Caltfornta

(durlns ttre rcading). l{r. Chairmaa, I

ask rrnrrnlmgq5, @Drent that the

a^mendnent bc @nsidered rs read end

printed ln the Rrcoro.

The CEAIRUAN pr.o tmpore. Is

tlere obtestlon to the rcquest of ttre

gentleman from Cellforala?'There rla no obJectlon.

Mr. EDWAA,DS of Callrornla. Mr.

Chalrma.n, I be[eve thrt tbls rmend-

ment ls not controversial. Ttre blll oow

provides t.hat a bailout ls barred lt 8

votlng discriminal,ion sult ls flled a,fter

the bcllout ectlon ls fUed- Durlng the

commlttee debate ln the full Eouse

Commltl,ge on tlre Judlclary, lt was

suggested thet rqvbody could prevent

a clean Stete or oounty from balllng

out Just by ftllng a gult or a serles of

sults cft€B/tht JurMiction had f[ed

for brilout.

The majorlty ol the subcommittee

believes that ttre dangers of frivolous

to sectloD 6 preclearance.

I

t

.

i

H 6940

It reems to me that tn Bome arers

clmller prcblems stfll exlEt end aueh

rellef, I thlnk, ls vltally lmportant tn

order thrt mtnorttles have an opportu-

nity to vote.

I want to say lD closlng, l&. Ch8tr.

man, thBt at one polnt we had a rcrles

of meetlngr trylng to work out what

could have been a compromlse btll re

latlng to the batlout. I belleve that the

barge,hfng partlee on' both ddes-I

had the responslblllty ol trylng to ect

ss a go.between-tbe partles on both

sldes ln my oplnlon bargalned ln good

faith. I worked wlth the gentleman

from Elouth Carollne (Mr. CAupBExr),

who I beUeve reflects a,nd speekg for r

rather l8r8:e Drrt"ltpr of southern Re.

publlcans, some of whom were helped

by blacks ln thelr electtons, some of

wtron for a long tlme hsve belleved ln

baslc due process and fundamental

rlshts, end I gtve I great deel of credtt

to them fgy rnaklng whet I thlnf,, sas r

good-falth effort to try to resolve the

dlspute over the bellout provlslons.

I would llke to cell the Members'et

tentlon to a letter end accompanylng

data thlt I recelved lrom the Justtce

Depertment whlch ts relevant to thls

debete:

Ir.8, Dr^arrcrr or Jssrrcr,

Crvn Rrcmr Dnlllton,

Vaddigtot\ D.e., @tD&r r, 19tr,

IIorL Tor R.eusrrcx,

Horse qf Reprereibboes, Wothtlgtor\ D.C.

Dree Corcnrssulx RartsB cr: Tbls ts tn

reply to your letter ol Aus:u8t t2, requestlng

lnformstion on operstlon ol the legJslsUon

to rEend ttre belhut provlslons of the

Votlng Rlghts AcL Please excus€ our delay.

You asked us to comDsre, wltb respect to

each of the objectlve crltarl8 lor a bail-out

,udgEent, ttre blll report€al by the Bouse

Judiciary C@mittee and drsft amendments

prepaned by Congresssn Eyde.r Under

either the Comnltt e blll or Coneresm.an

Eyde's draft, s @unty ltir I covered st^at€

cpuld brtng a 8eparat€ ball-out sutt and, It

Lhe oounty artd lts lncluded government

unit6 met tJ1c st8ndards, the county could

obtaln e bo,Il-out Jud8ment. Under the Com.

mitte€ bill, a Btat€ could obtstn a ball-out

,udement only lf lt rnd 8U lts counties Eet

the standards. Under Congressman Eyde's

draft, 8 state th.t met the Btandards could

obts.in 8 ba,il{ut Judgment, even though

some of tts counties could not do !o.

The standards whlch we sill discuss rre

those relsttng to use of a test or devlce, com-

pliance wlth Eection 6, denial of preclesr-

anee under Sectlon 6, flD8t Judgments flnd-

ing voting discriminatloa a^nd uge ol federal

exaEriners. In accord vlth your letter. we

Ili.ll not address ihe "constructlve eflork"

provisions or the general provislons con-

cerning violation of c.onstltutlona.l or Btatu-

tory prohlbitlons aaalnst voting discrimina-

tion.

,. Ase oJ a tesl or dcolce

With re8Erd to thl8 aspeet of the bail-out

ste,ndard, the Comhltte€ bllt and Congress-

man Hyde's draft are the aame. For a Jurls.

diction subject to the Act's Epeclal provl-

sions on the bssls of the 1965 or l9?0 cover-

age formula, thls element r€lates to use of e

lit€racy test or other':test or device" s'lthln

the meaning of Dcttdh a(c). For a Jurisdic-

tion covered on the basis of the 19?5 amend.

! We us€d Congressman Byde's dralt dated Juty

30. l98l (a:Oo p.m.).

CONGRESSIONAT RECORD - HOUSE

m€nts, thls clement relatoc Erlnly to use o,

Engllshonly clectloD! (sec Srtlon a(tx3)).

Wc do not hrve @mplet lDtorm8tlon on

the urc by covercd ,urbdlctloru, alncc

Aucust C. l9?a, ot "t sts or devlce8." Wlth

regsrd to thc Jurrsdlctlou covertd on tfic

basls of ttrc 1966 or l9?0 tormul8, wre ltre un-

eware ol rny rurbdlcttoru not ln coEpllllrce

f,rlth thc prohlbltlon rs8lrut ule ol lltera.y

tests. Res8rdfns the l9?6-covere<t Jurlrdlc-

Uon8, a basls lor oovera8le war utc ol Erg-

Ush{nly clectlons lD NoveEber l0?{; thc

Act'B prohlbltlon toot cfrect dt€r August

l9?5.

Z Cornplionce wllh Sectbn 5

Under Congressman Eyde'! drBtt, one DnF

reqrtl.lt€ for r ball-out Judpent woulc! bc

compllaDoe rrlth Eecuon 6 durhg the t n-

year Derlod. TIre Connltt€€ blll contelnr

th8t rtrDdsrd rnd adds thrt lt Deanr that

no chroSe ln votlng l8rrs rrer entorced rrlth.

out precleanDce and that rny change lor

whlch precleera,nce was denled murt have

been repeeled. A'he Dep8rthent do€s not

teep lecord! on letilalatlve repeals loUostna

r fallure to obtsla preclearance (unle88 the

,urlsdlctlon aubmlts aew leglsletlon to rF

place the orlalnal lss lubrect to obrectlon).

We thereforc are uanble to determlne the

lmprct of txl addlttonsl tequlreroent.

Ttle Eatt€r ol aoucompllence vltl 8eq

Uon 5, tb.st lC t&e fs[ure ot covered ,urte

dletlonc to obtoln preclearance of changee

lL votlng l8s& srs dlacusaed durtng the

r€cent heertnss of tbe Subcomnltt€e on

CtvU rnd Constltutlonel Rlght& lfhen ee

learn thst f€vercd turhdlctlon nay be ln.

plementtnS a Dew votln8 lis tlrst had aot

been precleare4 our pmrtlce 18 to rcDd ttre

,qrtsdlctloD . lett€r EqueEtlng coEDllsnce

with SectloD 6. (ThI! pnactloe fr dbsus8€d ln

the December 2{. f980, letter lrom tomer

Assistant Attomey G€nerd Dry8 to CoD-

gressman Ddrards.) In celendar yesr 1980,

for example, we 8ent l2a letterE ol thts typ€,

8nd Eost of them r,e6uftad ln e Eectlon 6

submlssioa to this DepsrtnenL OtJrer evl-

deacr ol the probleD of noDcoBDllsnce

crtth sectlon 5lr lit&oflon to €4oln enlorce-

ment of a chan8e tDst h8d Dot reoelved pre,

clearance. Thls lncludes sults to bor lmple

heDtatioD ol chaneea obJected to by the At

tomey GeDeraI Eince Awnut l0?{, there

hsve beeD aome 60 rulta le€klng to enforc.e

compliance wtth 8€ctlon 5.

Our afulnlsttBtlve effortr .Jrd tJre l&cr-

suits brought by ttrtc DepsrtmeDt or by Drl-

vEt€ p€rsons tndlcste that non@mpllance

wlth SectioD 5 is a recurrlng ptlblem- There

ar€ undoubtedly lnstances of noncompliance

that have never becD brougbt to our stten-

tion. For thl,s reason, se c8nllot Eesningful.

ly estimst€ the nuEber of Jurlsdlctions that

mlsht be effeeted by ttrls eleheDt of I bail.

out, staDCa,rrd.

3. Defi.al al precleorwce

This aspect ol the ball-out provislon is

skdlar under the Conmltt€€ blll a,nd Con.

eiressman Eyde's draft. ODe dllfercnce 8p-

pears to be that, under the lBttcr, r stete's

sbil.ity to obt8lD 8 bsil-out jud@ent would

not be affected by denlsl of preclearance for

a county ot Eunlcipsl lav. Under the Com-

mlttee blll, rn objectloD to a county ordi.

nance, (or example. Eou]d be s b8r to bail

out by the state es well as by the oounty.

Also, under the Commltt€e bll], the pend-

ency of I Sectlon 6 submlssion or a gectlon

6 preclear8Dce sult Tould be e bar to tBsu-

ance of a ball-out rudgDent.

Slnce August 6, 197{, tJrLs Department has

obJected to 8 total of 620 chsnges submitt€d

under S€ction 5. Thls tota,l lncludes obree-

tions to 168 changeE ln 8tat€ lrss. fhere

\f,as an objectlon to at least one change sub.

mitted by each of the followlnSi lully c.ov-

ered Etat€s: Alabama, Georfia" Iruislans"

&tofur 5, 1981

Mlsslsstppl, South Carouna, Texas, and Vir-

ftnlr. AJro lncludcd rre obrctloru to 452

chrnSes .ubmlttGd by I "Dolltl6l .ubdlvl-

rlon" or by r unlt bclor tlle county level:

therc chrnSies rcletc to pollucsl rubdlvlelona

(or thelr tncluded unlt!) ln claht ot thc Dlne

lully covercd rtste! rnd to t2 Dolttl6l ruur.

vblons not looted ln r lully coveted ltotc,

Att chrDent A le a Ust ol ob,ectloor by

rtat .

Slrt€eD ,ur&dtctlou whlch recelved obJec.

Uons brought dcclsntory rudgmmt rctloDs

under gectlon 0. Tro of thelc actloD! trsult

ed tD r prcclerraocc tudgoent. tD 3so lD-

lt&nceG . ,urhdlcuoD brought ruch rn

r.tloB sltb respect to r chaDge th8t had Dot

been lubEltt€d to tbe AttorDey GeDerall

Delther one lesultcd ln ,udclsl preclear-

lnoe.

Att8chEent B b r llrt of tJre!€ cales.

Pleas€ notr tJrrt ttrc Attotaey Geuem,l

lub8equeDtly rlthdrcv ttrc obJectloDs to 260

oI the chenrca Fecsrrtlng 182. the obJec.

tloD ear sltbdr8sD rftcr trhe ,ultrdlctlon

bodltled ttrrG proD6ed c,broSc or . tlel8td

law; ln the other f87 hstsDce& the obJec-

tlon rea slthdrawn ln the ebsence ol mch

modlflcstlon (a9., dtndrswsl rfter ttre Ju-

r[dlctlon provlded rd<llttonal lnfomstion

to thlq ElepsrtrDent).

Attachnent A hdlce,t4s, by tootDot€, the

obJecdons th8t sere vltbdrrwn"

l. J@ntilt dctamlnttg tlbdmlnotlat

The bell.out prcvtsloDs of both tJre Com-

Eltt€e blll rDd Contlessmen Eydet drrft

reler to r flnal fudgment ol . tederrl court

(other thsD dcDlal ol I ball-out ,ud@eDt)

deterElnlns tbrt, dcnlr,l or rbrlchmmnt of

the rlAht to vota on lcoouDt of race or color

or (ln tlre care of r lyl5€vered Jurlsdle

tlon) Dehbershtp h r lenguage ElDorlty

3roup occurred en5rrherc ln ttle t€rrltory ol

the stste or polltlBl rubdlvlaloD.t Such r

Judgbent could r.e8ult fivm r Eutt lDltisted

elther by tJrts DepsrtEent or by . prlvst€

persorL

Stnce Au$rst G, lYlL at least ten flnal

,udSments determlnlng votlng dlscrhnlne-

tloD gct! lssued.t Ttreee JudgngDtE Elste to

or rflect ten poIttcst subdlvlslons wlthln

live ot the covercd rtatea-Alabema, iSeor-

gla, Ioulshnr, Mlslmlppt, rnd Texar" In

eight of these sults, ttrrB Dep8rtmeDt tnlttst-

ed the rctlon or pertlclpated a! a.Elcus

curla€. lte rrnqlnin8 two were prtvah Euits

tn whlch the Department did aot parilci-

p8te..

Attachment C ls I Ust of these cases.

6' Federal glrmlng6

Under both the Commlttee bll! and Con-

Sresshan Eyde'e dratt, s ball-out Judgment

would b€ bsrred lt, durtng ttre eppllcable

period, feileral eratnlner8 hotl been "as-

slcned" to the Jurlsdlction. I'ber€ are tso

posslble lDter?retatlons to tlrls provldon

It could rcfer only Lo use of examlners for

the purpose o, Usting peraorut who ar€ quali-

fied to vote.r U eo,.t5c effect would be lrmtt

ed. Since Aug:ust 0, l0?{, federal examlners

have been used for tJrls purpose in only two

counties, both ln Mtssissippt.

-6"-co--rt

"" blll referg b rddlttorL to any

rctuement rcsultins lD !,bendonment of a votina

Dra.tlce chdleDsed l. dtlcrlnlnatory lrtd to t'be

pcDdency ot rtry ruft aueSlns yotlrr8 dlscrlDinstim..Slrrcc AuSiurt lCIa. sh votlDa dlscrlElnation

sults lD rh,lcb tJrl8 DeprrtEmt particlpst€d rcsult-

ad ln -tucEent& 8ee AttrctEent D.

'Wc hrve oaly llnltcd |nfonB8tloD on tuch Drt.

vatr Eult8; trre totsl ls prcbably hl8her.

. Under 8€ctlon 6 ot the AeL the basic lunction of

,ed€ral exunherr ll3 to det rmlne th. q'r.tlflcatlotrs

of persons who 8€eL to rcalst€r to 9ot€. Ercmlnel!

are rlso uscd to rec?lve complslnts reirrdlnS ehy

electlon to whlch bdersl observ€rs rre sE8lgned.

8€e Scctlons 8 rnd 12(e) of the Act.

f

(:1

t

htobr 6, 1981

The other Do8slble tnt€rpret8tlon ls that

the provblon also refers to astlSnlng exrrn'

lners lor the purpose of rccelvlnS com'

plrtnts rt the tlme ol an clectlon .t whlch

lederel obs€rver6 are present. Elnce AuSust

0,'t9?{, lederal observeE-8nd therefor€ ex'

rrnlners-heve been used tn a total of ?9

CONGR.ESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE

@untlcr ln nlor atrt€.. Att .hment E shows

the use of obseraeE by rtste by year. Please

note thst dehued lnlormatlon on the use of

ob6erveE th,rrtru the Derlod Jonuary I, 1976,

thrcugb December 19, 1980, war !€nt to

Coruressmea Edwards on December 2{,

H 6941

1C80, by lormer Assbtrnt Attorne, Generel

Days.

We hope 0hrt thls lnformatlon wlll be of

esslstance.

8lncerely,- Wn. BRADToRD Rcyrot.Da.

Asslslant Attornelt Ckneml el1dl,l R{ghtt

DioialorL

Enclosures.

AIIACflitEr{T A

-LtSTfiG

0f o8.lEcnoilS R [Sl rfl m sEcnoil 5 0f IHt vonnG RlGl{Is Act AUG 6, 197{ I}lR0uGH S[PI. lE, t98l

tbffir &! d (ffi o* ts 6rcffi rE Ifiryy l. 1975) r--&ol.o iH lts tcl r E s{b.fsur. &-trtrgatm sc 5 qrrrErsrl lctn{hrld srt6 c---tjbrrhr-sc_ 5 dsm,tt +si--trrr''-TfI;tr sr s'&i(;iiry-iiit- iilii-tjrtiain dmD [Isa 5 dim d .t{a (ri tbd rdr6 nd;innt nrr : S.lErsc). f--h rtf6sm---r_ollctgl, Hla str6sGJoorrtd'. ll-

6"ifrirnfr-r5.ii';6;il il Ur"otitu'--ur* diX *U.}-IA O|doo--@rrrr hnS '!ffi Ur!, otF6or' 6 f,Urfrrlru, * I'nErq GCGr. r Mil! ftrG tl!

iir a rrUr il in|o;r oiar,rd rtr tr irEd(to0 [rL ! dtu dir r lB.E Fldrc fi.i llrud D t,.lt E ,Illlq Ur t@U

trislclirE rlhcbd tF d.llrl!6 otccla b &b ol diEht hdFcln

:tm

x.lSlrA

rlTDiU

cxfo8ls^

ffiil.:-:-.---:::::::*--::.-:::::::::-:::-:'::':::::.:::::-::ffiffiIffi;fi',nd;i;iffi;iiEiEi:.::::::-::.::H.T,|ff-1-*:-::.*l

bo

lh.t

hhtr.....-........ ECdE...---

naGrt Ilrflrm E r8m c dl.'m,.naGE Ilfft[pn E Em C dl.'mr.

I

I

*LrOgt,.....

Sbr (I5rn 0

ma Cndr 0o.d

Iffid.tct! (ngry*sil

H$6 d 6u (,l.lrga nf,{atr a

;riffi 'ffii-ililii;' iGi.-.-::.:::::-::. H il: l8ii,:.::::.::.:-::. b

iil ;i;;:--:-.:-:::-:::-.:::::.:::-:-- ff rTi,li/j ::::--.:-.:..:.:. $

II 6942 CONGRESSIONAL R"ECOBD - I{OUSE W 5, 1981

fiTmlffiI r.-$lm r nf,cm ilgilT E sril 5 t m wm mlll E tn 1 197. nf,u,ot !t?t. 11 ltt--ffi

EEl**'8r:i-i*EJffilk r ffi lr fitEm Ero Jrr t

-

rt, ffiI rIF t raD rE a E r I E I rf n .IDl

a

lriftuBffi I,FC.lralr dir! b tr.€ EF

!E lrr s,l, .0q,ltc hg..-_.,_..-._ ffir d pIE cE (i@

'tc

r ca, sr asr,!, ds[n, .*.. tE, t !tl......._ rIr IEr ttlr lt

-.

I E i- Itb .IEr r EE @' fg- ft !9S! i

mcr0"I

qrhslul lffiO-t)..-_-- l-th t{a Ult'.-

-c_'.4 EaE-+a-r3E-|EtDrrEEE. hltr--ffi.il r-..aEf rIE

-t--lEtLIE-e,'

:.SJ.-

lst.o!l8.=.-.-.: EdrI- gtJlt) h le Uil.0irrno^(cEacr0)..---.- bq*I ._ ,a ll Ur( f.orrflh-Quq-'..-.--_---_- rya C .fb (E !

-l

Q ;ir-. 5 t U7s A

).rEceiJm-i,ED-, Ecr-Er -r s.lir.t$6_IsulricunttuMhtr--bcElcb{c*rFltFtcrh*) d.LIg,6

--r

!dr!0ur ([icq*] bi.b tr#r*s-E)- b.26. 1976.___ f.

lf,aBl0.'r,.:n EcE{r+FI.. ,- h'3.r9r6..

-&C

Cl.m tt (E^rq) ..__ ru r.Idb {!.ilty Er!)*--- h. U. 1916 a -

Fidnn.(oEiBrr9)__._._HdeH*)_-- Ear977 aItdld (oue tu1)------ trtd .l .E (*{t o)- .n i.lgn_.*__ |'

QndrfrilrFrlhtr-...

-I-a.E{rIr-rrEl

h, Etl.--EffiOi--il;r-, - 5aE.i!-I-r.--..- til UtG;- Etra-|}ctrGltrr-,

a[.Ea+l

ErES_lIr,OScblEI- IlEdrEb [rl.trt!r..-...---_- Ar 31 197r._

P.ier qnt!'!..-- hde (i{rB GrqrE:4d-rrny{tbdl- d ?& l9r, _ffilrc-lanv'.-. EJ&!(r{a8e!fJEEd!rrEE)- b 21!-qrr..-.--__;

l3ffirffi-rcLffiffi-i,Sffiili:'q--::*--- rrr.te,E.--.---*rrarB (EEl Cur!:- te d 6 (r& c)- - .Ir 5 !!4 _ fB (r..Ec!4) H d *cE ("rainu lldr)._.--* !!it h. 19n.. a

Lfi5ler (LmEt C!n0)...-- 5 a ib (ria rcl-..- S-r- n tg4 .._ I

S GdlF (ooqt E Cqnty) ....--...-.......- . tlH d et[' (sa!s?rd 66)......-..--.:--:.-.--..........___.....::.:. _. d-t.]Cri .....__Il tb Hil (Yot Cqrt) ltu d.XcI (oriilr nfrl.----- rlr ri rcrr

^

EOI IICT

G. L m.._.__. t.EA, l'rg...--*lr

hnbr 5, 1981 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE H 6948

AnmilE[I A.-tfflllc 0f 0SJtCTlOtlS nnS,rfiI I0 StfiUl 5 0f l]lt lUltlG $GHIS ACI Al,C 6, l97l I]lR0t GH $n. lE, lgEl-Contlrud

' 0-{ffi * S -rrtrr r*f din. t--{nr'tm ttr m{.c 5 don ffi, ttfla (ad dlG, !rd'.G rtdy'n8 ft E. 5 cnx&i, I-irr -0rrrdt{ trdE. G--.ir !!r6or--Otrm, H-

Od; iffim. L4|rlr'i!.mr|u 6r !r a|fr0-.Eu|.tr rlb tmr ocrn!4}-b01 .qdm-.qtt0t,f,. En& mrbd nEr x Otdm E *lt(lxi t, U. Alurt Grrl. r ffi ,rlcrtc tr

o*, a rror D rEil clIru d|r h Flddo m* a 6mr ciqi h lb.b IilrE $.i Enuu ur u!t! lu irutlrtr 0r o,Elutl

fftin dlicid IrF d fiB.. otl.cil b lltt d otlltbi tlddirtdl

Jlb

tria !a

fd hrn

L0rod o, docl[! (ftgsd

ffln d for,nilEl (fiflt

E0st'rliu (SUE saah) ...,

Bdbbrctin8 ($re hle d a

.olithfr! Set ?Z lgm. .r lithdoxc Id 13, lgEl aor .iaqe h *cfo.d 9X$r. .rlithorn 0a 21, 197a. .tUlthdarD AF 12, l9rl rFr fr[e n ffifid srsen.

Srol 23, 1971.t............-.

,rry 11. 1975.r................. t, ll.

Srpt 27, 1979......-........... L

oct 27. 1980.........*......... l.

td) lr, 1981..................... J.

,o 31. t9E1.....................,1.

u 69{r @NGRESSIONAL RECORD - IIOUSE

rmorpfl 3.-squ t Errfim rDmr EIm (mE onr m m Erf c cn0nu)

13 lt,llBI,nl

&tobr 5, 19gl

h!b bT tIi,EA. bdE

.ar!@e tL@h.

{IUOIIE{I C.-4tUl. n 0Hs(Is slict ra 6, ltta, ri ffiflo{ A flf,Rfl. m,m iAI[ A ilDfG 0f D60ailfifimil n v0IrG

baEir brfE

trffi!!t,1---:E=- .tAIn

tr&E1qE'A.---Fc*r_Eill#

lm

t9t,

rn.

ELrLt&wr. &JItrlrr iiCllEir-r H!r. ffi,i EFSlll

."}ioE.- - l rr $r a - rliift. h Ht! r tt + i t[ nlrlr, tr r E, r H r ta l! rt rra

lnffiflI lt-sEllfltlls gErn E rg7{, (r lolllc ECSlIlnAIUt CIIS H WtfrH It[ Dpr$Itm prmup^IE)

}J

-E tr I flffifi0ri;'Si&, rl_:: ffi(ffi

tH lt r. llu (trr, C,r' b. D+3ii o ut.._.-'_l'--_-1l:::::::l-- Gfj;,:f fifi F; ; a!fi-rE"r-lci.ri ir--i, 0 r rnt:-_::=.__*.. -: ffi Bffi,?-

L1r9r.r D. utlhz rmrrl tlfb.trnb1 n,

fluoiloff E{llr8t8 s culffis 8y yar s IH mI ffiBvE 0tHAGr t

t- 3-- .3

r 2 t==----T52r.

x

I

o

I,

t

,

Il

II'

t

2,-- l..-...--

m5

- I E Ht Hfil,:|qi i tsb! cr4'd ! it r34 r" 6!* rt b.r.i q .

tAiLIAIE!:Irtt DJQUIIt

Mr. KINDNESS. tr. Chrlrman, I

bave a perlia,meutary ttqdry.

The CEAIRIIAI prc tenpore. T?re

gentlemaD vlll str,t€ bls parltrmenter5r

tnouiry.

Mr. I(NEiNESS. ltr. Chatrma.n" I

heard et en eerlter tsne tlre Ueglnningof the reedng of the commftteenmendneirtt, lollmdng rhictt ttre

arDendrDeDt sblelr ls eurreauy belng

rliscuseed carne rmder dissussion vtth.

Out rCtlm On tb3 (drnmlttee mn*

ncntr, rr I otoervcd lt, h rhh crcrrL@ !.dmr-crhld bc telen m tbe

'@Enlttee amendments prlor to coo-

olqslon Of Or further proCc; 6rp thts

nmpndmenL I tpfleyg.

U my obseratlon ts eorrect. I would

relse t&e poiDt of order Uut lt h tt

order lor tJre comnittee eaenfueotr

to be ar:*ed upotr"

The CEAIRMAIV pro tempore.

TbeEe Sre rDeDdEerlts t6 the aOrrrntta

tee rnendnerrt h the netuc of r srb.

stltut€ rnd t&:rdorc h aG.

lf,r. LITNGREY. Ir. Chrtran, Im"e to strtle tlre Equtdta u'rwrbcr ol

rords.

ltrr. Chal:rnea, lt I could ask ny dla-

tinfuhhed ehairman of tbe rulcom-

rnittee r question yitJr rrrpett to bb

rne:ndlneart that ts Dendng before us

Ar I undcrrte,nd one prt of tb Se.

tJornan'S rynanrlrn€r{ f;!3 tO d6lrtth thc qucrtlm hsq3Lt up (turhS

conslderation ol tDa bIU. trd tJrat G

Pendlns suits ln lrd of +han.etrEr

behg r hr Etirt be rhccd nrcb

tXet oe could Ile r peodoggrlt eltcr

DeuttloD by r corEt heft beeo ntst, frlcd,

rrd tfrererore actr rs en grtmr$c ber

to bdlotrq ll ftrrt cattrt?

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE

I

Ocbbr 5, 1981

Mr. EDWARDB ol Callfornla. Mr.

Chslrman, wlD the gentleman Yleld?

Mr. LIINGREN. I Yleld to the gen-

tlemen from Celllornla.

Mr. EDWARDS ol Calilornls. MY

amendment only eppHes to sults liled

after the flllru ol the ballout actlon.

Mr. Lt NOREN. 8o glth respect to

the queatlon thBt hts arlsen ln the

Btnds of some about pendlng luits

whlch rvrny hlve bcen brought prlor to

the petltlon of ttre Jurlsdlctlon betng

Itled wltlt the partlcular court, whtch

mey or mey not be frlvolous, that sltu'

atlon would dlll prevell ls thet not

correct?

Mr. EDWARDS of Ca[fornla. Tbat

Ls correct, they would stfll be e b8r.

Mr. LITNOREN. 8o tJrere ls nothlng

wlth respect to the bsr thst ls ln the

blll now whlch sould dlsallow r Juris-

dlctlon from belllng out lf anybodv

had t[ed e sult clalnlDg an ebrldg'

ment of the rlsht to vote, lD gny Jurls-

dlction, lnslud{ng Eny Stste 'court,

even under any Stste law, 8s long as lt

was done pr{or to the date thrt the pe-

tltion was flled by e Jurlsdlctlon aeek'

lns to get out lrom under: ls that cor'

rect?

Mr. EDWARDS of Callfornb. fbat

ls conecL but we belleve that the

danger ls mlnlrnel. T'bere are pro-rri-

slons both lu the Federel courts end ln

the State eourts for dismlsssl of frlvo'

lous suits and for the asslennent of

court costs end attorney fees to the

plalntlff. 'We suggest that whet the

gentleman lears is really not of 8reat

moment.

Mr. LIINGREN. I thank the gentle.

man.

lte CEAIR,MAN pro tempore. The

questlon ls on tJre mendment offered

by the gentleman from Celtlornia (Mr.

' Mr. rrYDE. Mr. chairman, r ofier

en nrnendment.

The Clerk read as follows

AEendment oflered by Mr. Evlr On

page 5, une 2, ctrlke "end no" through the

remicolon in line 5.

On peae 8, Une E, bcfor€ the perlod insert

"and vitlr rcspect to rhlch th€ pldntif,

d€moD.strrt€s that euch toting practice

would have precluded the issuance of a dec-

l8r&tory ,udaEent under thl! sub6ection

brd cuch practlce occut?ed durlng the ten-

year pcriods referred to lr1 tlls subsectlon".

tr 1300

(Mr. IfYDE asked and was Eiven per-

nlssion to revtse and extend his re-

kE.)

Mr. EYDE. Mr. Chalrman, this

amendrsent tahen in conjunction with

tJre last s.mendment adopted elirnt-

nates the provislon tn the bill whtch

equst€s consent decrees and settle-

ments vrlth final Judernents for pur-

poses ol sreating e bor to ellgibillty for

ballout.

I sugcett that consent degrees and

settleme-nts should be favored by the

law, not discouraged. AII I want is to

restore discretion to the court, and it

wiU be a three-judge court, to look

H 6945

(^:

behlnd eny tgreeEents, !€ttlements or t€chnicaltty. It ls to make thlr work-

consent decrees to see why they were sble.

made and whst the substance ls. Mr. McCLORY. Mr. Chairman, will

Thls btll ea unemended by my the gentleman yleld?

ernendment makes t conaent decree an Mr. HYDE. I yleld to the gentleman

absolute bar to eny ballout lor l0 from lllhols. -

years. (Mr. McCL,ORY rsLed and was glven

I rm suggestlns thq court ouSlht to oermisston to revlse and extend ils re-

plerte the form end look at the sub- foarks.l

i'"T$'"f, 3$.Hif,S:S:.!.ff-U",t,tg3?"';,iff;3#1ft"3;ip :

do not Bll have to trek_to^Wasl[#^1 m"" oo his efforts to try to iesolveto-lldset€ tJreae lssues-9^!I.-fJt!:I thG wnote prourem ot extdnston of ttre

end. U ttrey cs,n rea"!_1qryg"l!:l1t V;r"s -nriuts

ect- rn i urpartrssnua encoulage aSlreetllenta llq |!Ey-q manner ena u I Ergnner whlcir cen benents and conaent d€T"' -bll,9iT! Iiltnenuv ls.lr to the covered gre8s ol

Byi.*ilr.:rsir'"xHx_r""t"n:trfff:ltrJffi ffi H#r#'ffi

I3_

for 10 years. Irt ttte c

sltuation.

The t8ngua^ge of the blll wlth tJre wlthout discrlmlncuon e

ffiHffin*sig%ffiflli 3?iffitr{iffi* ",th

mv co,- !

ffie-rew has tradt6o;fr,-Gdffi;;fr feasue from Illlnols end urse tbe

Eetgement. membershlp ol this body to approach--i- ;nA;est to my collea3ues who this Drtt€r 1g1r'lJ: consenl 9ItPT 1y.9 t

mtght want to oppose-iU6= amena- commonplace tn law' and can be the

me-nt, f they look iri page iot itte UiU product of s ntmber of varylng moti'

ana ieaA fnes 1 UGlisn -td,- thgt vatlons. They ca,n, rs the chairman of

Dobodt G goine to get awiy with any- tbe. comnlttee would ruggeet, reprre-

UrG.-XoUoaV- G -S.ir.1g-i"--6"ililt sent repreherrqlble elfort to disen' I

tberiselves tn-ag ebgEiv; manner con- franchlse mlnorlty voterr. 'On tbe i

;rntnS vottng rlshtt and ruccessfully other ban4 tle_V- ge-.more lll.dy to

;etnasirx e bail out. Look at the lari- represent Sood hlth lr"agreement oa

guaige: varlous questlona of law and a Sood

(B) No declaratory ludpcnt rhnlt tssue faith effort to recolve tJroce dissSfee' ;

unOer ttris subaecd6n rtth rcspect to ruch menta short of Utlggttqt" Rarely b lla"

6Bte or poutlcal zubdlvlslon U such plstn- blUty determtned ln consent decrees,

tlff and government8l rtnlts rrlthln its terrt' a6d Wbjle there mAy be !,n Ssfeement

tory have, durlng the nertgd beSlrmtns ten between the partiee es to rhrt the rea.

years before lqe d8!€ ,!!9 ^r,"lg"lJ-j olution miShi be, no effort ts mad€ to

HH*;rffiE"S,HlH%

o[$fl,iT*; estiuGri i"ponsiuuttv ror the rronr.

Unit€d Srgres or any gtrtc 6i poiitror e,it Tbe law has trrdltionally epcour'

division sith rGspea to <tticrimlnatton b aged oui-of-court s€ttJcpegts rDd

vour,g oo mrnt of r.oe or color or (ln the l"consent decrees" where posstble. I

cese of I Stst€ or subdlvldoD reektng r <le would questlon tbe che,trmru ae to

claratory Judgnent under the rcond sen- whether tXre Judtctal Conlerence was

tence of thls subsectlon) hcontrav€ntloD ot consult€d on thls polnt becar.rse the

ttre Snrarent€es of aubeectlon (fx2),tn?less use-of consdlt alecrees es an abGolute

t1""3$*'ilffi,Ylffil3lil[tr**S:: pT to eugtuiutv ror bauout rrut doubt"

and wer€ not rcpeated. less have t&e effest of discouraglng

#*, umr, xn""""; m sl Hi'"ff;8:#'"gffiFg:violation..-wni-ira.-

the door because they !1"_9_119T-"f-.YoP9_Il"e spprcved

HjffiF*tffi :##i"Tfi [:i'#.'Tf"""]"]"3,iff*":i:il""ii!

have the court look at iilati-' perptt the content of consent decDeeg

-if-wJfooX et pagg 6,-liD; a through to be exa,mined lor purposes ol sn

ra, tne Starc 6r -p"Uiiof-iriUiiui"i6ri equlteble determination of whether

has ro have eltnln"tiiloifiililJ- constructlve efforts heve been 'com-

dures and methods oilfi:cifoi i'nrct, pUed wlth, a,nd whetber 8t8t€ or Fed'

inniUit or dilute "q"if-a".J*i-6 iil

eral lawe have been broken, I believe

eleetoral proce$ arr-a EavJ-Jng"C"d tr there ls sulficlent protection already

construetive efforts to e1ii"ila-te

-ip- present in the blll.

timidation ancl harassmen-t - In edditlon, lr the Department of-

Wni h"- itre Oooi beeause a con- Justice feels that the furtsdiction ls

sent d-eeree has been lssued? indeed at f8ult and that lts ease ls

Now, tt m8y b€ that ttre consent strong enough, tlrere ls no reason why

decree did setile a flaerant situation, it should aSree to a consent decree and

but cen we not gtve discretion to the insteed push toward I ffural Judgment

court to look et tlret? Nobody is going and ultimate recaptur€ under the

to file a batlout lf they have ageed parole provislon of the bill. I urge the

that they have been abuslng people's adoptlon of the amendment'

voting rights; but the technicality Mr. HYDE' Mr. Chairman, I thank

ought not to foreclose a bailout. my friend.

All I am asking ls give the eourt All I am asklng is let the eourt look

some discretion and elininate this behtnd the paper to see the reality.

-'t ,l

' H 6946 coNGREssIoNAL RECoRD Jnousr htober s, IuBI

I thank the gentleman' efter slgnlflcant expenses- have been Mr. BUTLER. Does lt cost more toMr. EDWARDS of Californla. Mr. lncurredl' chalrman, iiGe rn oppoiiiio;-i; ii; inc opereu*e ransuase rn the srar. ""ljf tffi""3lrB*Hrili"R. * arwaysamendment' I conslder lt a weakenlng utes ls tiraiinJcJnenio"ciellieiii"- cosrs more to try a case; but reclarm-of the ballout provlslon. mentor agree-ent.-na,

""t i"i"fti,lil-" ii, _v ilme, somettmes most of theThe amendment offered bv the gen' auanaonm-;na;? th; cn"iru"Lua t'iti,id

"*o"*", rn preparatton for trrar andqeman trom llttnols tMr. Hyoel w6uld ;;ffi:" " -. ,...

. - _ ln discovery have already been ln-ellmlnate consent decrees as a bar to ' atv-

"o.""rns that frivolous sults iu.."o at the ilme the consent decreeballout' Now' all lawvers know and t orio a"I-"v-ii-rt uiiro"t luagmeni aie is entered, such as the case that I crtedcertalnly all the courts know that even n-ot suppoiied by th; facts. ft

"-i;uaer- fivolvlng McDuffle County, Ge.though consent decrees rarely coniain al Rul'Ci ;f c,vti ana appirr.t; pfi;- " Mr. ptrTLER. well. t ask the genge-admlssions of liabllltv, thev are treat' aureJ piovrai i;;;;;;;j[;&!;; man lr he wilr yield further.ed generally as ,udgments. We have no and penatiles tur- iuch ;uiG.-- M;;t ..

trtr. 6SNSENBRENNEF1,, Delightedcholce but to treat consent decrees 5i.tu-"iiiii'ioi1"r" -iir";;t".I ;ffii- ,o.and settlements ln thts bfll as a Judg- srons ln the]r *Gi ir procedure,-otien *Mr.

SUT1SR. U we use the consentment.

- we have no evrd-ence and the gen6e- y*i"iff.tt-e rule number as che Fed- decree as- an.Inde-x of poor' perform-

qtffi.;itrii11'ffi-#l;pi:1tr"j:i:lx,,iq*"H,**.i$Jr:r,l,]$l#t,q#fr

tr{+Lt#i:,i'irff '*:"rlsdiction esreelns to a consent deciee consent decree. fne eviaJici';:':;"iJ _^1.^ l_ot-

the on-ly motivatton, the only

has ensased ln'dlscrtmtnatlon and by i-tre wrtnessd ;;t ili-t""irlri,iili!: I::o_tltu thev have tn the event of i

ffii::-t:f i:1"#tr?!3"::,"cfTiH trHXT*"*J"h;;;

il;i;ilil'iiil: ixl""ii!i{i":l}fi:yx!, fiil:,['fithe discrtmlnatlon. The key to this "I asr.e

-wittr

tne genleman from H:TrTrf"

motivation left to setile a

:#:gT?: "*Jli'. J*i,"JEHt,Tilll i"?'#",ffi,iJHr, xr*il"jie:rfltv "?.';;

a fair statement?

,tr*j*i*lim*** n:r,i*:.,gxt iffi$ir ;fr,s*l*9.ru*ffi;I ryPgpq q"q. retitrgatc it;-i;ii i,pon tn" eddence orlj'1ll?""roT.il tlemanexplqinto-J'*-tilmouvation

| fl'#-i[f'STffi;g"lf,?ff T:]: other,.rather inan "isi"il ";;;;; H"ffitsll'S,$ ii'" ?"i?i;ffil?,:"";

J '"i"ii"',:fifi,o#-;Hl,1%1,!9:irtserr un. ,#l;"?,ffii",T,'' "n"oman'

w,r :H,tf,E;*"""1l1*ldisappear

rn voiing

falrlv accused of dlscrtmtnation should Mr. SEIvSENBRENNER. I am -.Mr. SENSENBRENNEn. I strongly

i,:'tr!'!!ffi#,'t""iffii:.t[T; ]:il,*:i.'j;f;h1ilH#;' 'n'" 'Hl fl1i]1!i",,["1"*li-xlli."i $,,-,"""I

l5#"#t!;l:."xt:f;',1 ;?s',T?,i ;#if8l*"*;tl. ft"'JHti:-,"st 'o{.i""Hffii,tn#St

".lor conrainsare the facts of the consenr decree starement ueroie _L, 6,it il.il;ff.il an admission oaiGbitfr; io tf ttre evi-later ln a ballout suit in washinston, me the ;";ai;;;b';;;ir* .r.j#.i;

dence-.is q"rt"- cieai- t"tra]t- ttrere trasD'c.; but tf tt decides to enter into ri Gaic"lid-iiiif}".nJff"r,ir'"iiilli b.ee-1<liscrihGation in iiiiirg and I ju-

iit"il ii"JT;i'"?3$'3J';8."0:?:"J ffi; r;":R"*:{ij:ii*i,"iiiflii iHflf:iT"fx?xi:lr,r:*i%,iil3;fil-ing for bailout' of that nature. rs that

"-i-iitllii'i1,1

deree to ivoia rravil;; j';ac-enr en-I suggest that this.proylslon ls not a' Iion or the statement? tered agslnst it.si,dficant deterrent to consent de- Mr. sENSENBRENNER. Either con- (Mr. sENSENBRENNER, esked andcrees' Jurisdictioru usually fold up and sent decrle,Ettr"nlirii, or some other was given permission to revise andq-ult tn litigation because ttrev itrinr [La or as;uml;i.-----' exiend tris rimarrs.t - -- '

thev wiu lose. r doubt, lf the decision -rr,rr. aifrl,Elii.'ih" ,"r"o1 they are . . The -CHATRMAN pro tempore. Thew9ul9 have an,'thlns.--to do with settled is bec.us";1h;;;;i ollitie"- time of ttre gentiem;"- i.;; wisconsinwhether or not there wlll be a bailout [ion, tne u*p"*L,-."ii-tn" courri'-J" hasexpired.suit on the way. doubt encoui"guJ".n-retilement; has (At the reguest of Mr. Ii,rsH. Bnd byMr' SENSENBRET{NER- Mr. chair- that ueen the experien;; ;I'i;;'c;; unanimous consent, Mr. seNssxsnu'_man' I move to strike the requisite iigryran_in tne pasi:------ NER sas allowed to proceed for 2 addi-numberof words'

^E .^ rL^ _ - rvrr. sENSi:fradnNNeR. It is part tionalminutes.)I rise in opposition to the amend- of the canoru oi- p-ii."ional ethics Mr. FrsH. Mr. ctrairman, wiII thement. for the tegaf proieiio" to attempt to genileman yield?Mr. chairman, I oppo-se an amend- iItttuc.."luj"ie-tnlJ'so totrial, but .-Mr. SENSENBRENNER. r yield toment to treat consent decrees differ- i woua aGp"rc it e-g-"".ri.t"-"rr,, ,""".- the genuema,n from New york.ently than final Judcments. Approxl- Iion tnat 6o*""f -aZ.i"es

are signed Mr. FISH. Just to elaborare on thismately half of the voting rlghts-cases u"ro.J exl"n"i.--

"ip"*". aie- in- situation, particularly the one of costare resolved as consent decrees, settle- cunea. that we keep hearing ebout, is it notments or agreements' As a general -bor

ex"mple, in McDuffie county, true that virtually all of the consentpractice such decrees a's in other legal Ga., there was a ,oiirg rights suit decrees that we are concerne<t wlth in-matters rarely contain admlssions of niea in rs?6 ;nd aiier extensive di,s- volve m_ajor issues, such as ilistrictingliability' The agreem-elF are signed iou".v, a consent decree was siexned in and multimember elections, that theybeeause litlgation is highlv likelv to isza. Tne iunai;;r;;; t uot[ tnow sere proronsed processes that in-result fur 8 Judgment that the lurGaic' that discov-ery' ir;;-"*t;"mely expen- volyed a considerable amount of ex-tion's voting praetices or methods of iire proceouie i" a"l iino 6f riiiia_ pense and would be time consuming toelection are discrtninatory. The Juris- ;i;". relitigate at this time?diction's election not to go foruard -Mr.

BUTLER. since we are getting ur] sersuNBRENNER. The gen-

$liid:lii:ff, h*# t#"",':,'"",1ffi:T l"tru r:1.-*,ry':y_;ia;'ili "#:';,i:H1il?"T,'i|#ii rrue rharln che latter stages of a proceedings, - r"rr. surSuNgRgNNrR. I am de- tt ui"

"o*urrt

decrees have been rarge-often afler trial has begun and th-us tiinteA to. ly entered late i:r the proceeclings and

f1

-l

r-,

&tofur 5, 1981

sometlmes Jus! 8t the eve of trlal'

whlch proves the polnt thet the Jurls'

dictlon eould see that lt ls about to

lose.

Mr. SENSENBRENNER. The gen-

tleman ls also correct.

Mr. FISH. I would say the faci of

late aettlement takes some of the

sterch out of the argument thst con-

sent decrees are entered lnto because

of eost, because by the time they are

entered lnto most of the cost as the

gentleman has lndicated has already

been lncurred.

Would the gentleman not also say

that one of the most telling facts ls

that tn most ca.ses we have been talk-

lng sbout the court has decided that

the plai:ntiff should be pald court costs

and attorney'e fees, which means that

the court has decided that the plaln-

tiff is the prevalling party.

Mr. SENSENBRENNER. The sen-

tleman ls correct specifically on theL

If there were no feeling by the court

on the merits of the case, the court in

its dlscretlon could have denied court

costs and ettorney's fees to the plgh-

ttff and ln most of the corlsent decree

cases, ttre plelnttffs have reeelved the

cost of fees.

Mr. LIINGREN. Mr. Chairman, I

move to strike tJte requisite number oI

words.

Mr. Chalrman, I rise tr support of

this emendment. I-et me make it clear

to a number of the Members who are

not or have not been as involved as

those of us on the committee have

been, this particular amendment ln no

way suggests that the court which

would be making the decision as to

whether a Jurisdietion could bail out,

this in no way says they cannot look

at a consent decree. What it says is

that 8 consent decree, an agreement ln

the nature of a settlement, will not be

an absolute bar.

Now, q'hy ls that important? Even if

Ee accept the argument Just given by

the last tqo gentleman that most of

the settlements indicate tha.t there is a

liability on the side of the jurisdiction,

it still leaves the question as to those

others. Anyone who has been litigat-

ing in court in the last 1.0 years knows

that on the State level as well as of

the Federal level there is a premium

given tonard settlins cases.

As a nratter of fact, ln a regular civil

case if there is any agreement whatso-

ever that something ought to be set-

tled in the context. of arbitration, in

fact you will find yourself in arbitra-

tion instead of in the eourts them-

seh'es.

tr 1315

The courts encourage settlement for

any number of reasons, including the

costs involved. But the point is this,

we are talking about extending this

section of the Voting Rights Act

u'hich would other$ ise expire. Some

jurisdictDhs.'having viewed the expi-

ration da.te of this section of the

Voting Rights Aet. could in good faith

have entered into a settlement during

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD _ HOUSE

the past 10 years, havlng no knowl-

edge whstsoever that the fset thst

they would enter lnto thBt Eettlement

would bar them for 10 years thereaf-

ter, In other words, tt waa an unln-

tended consequence of thetr act. In no

way could they heve been aware of the

feci that lt would have thls effect.

So, whst we are talklng about are Ju-

rlsdictions who may ln good faith,

having had a dlsa8reement over the

merits of a particular case from the

Justice Department or from an Bg-

grieved party, have entered lnto a Bet-

tlement, It seems to me that lt ls very

lmportsnt to r€co8xf,lze ttlat the Judt-

cial Council has, over the last l0 years,

recommended to those of us ln the

Congress that we do everythlng we

can to suggest that settlements ought

to be uttlized more end Eore. Here, we

ane saylng to Jurlsdlctlons thst have

followed that directlon over the last

decade, "Because you did that the

court wlll not even have the opportu-

nity to look lnto the merlts of the case

as far as the settlement rras con.

erned."

That ln no way sayE that Jurlsdic-

tions that Bre recalcltrant, where

there was overwhelming evidenec ln

fact that they wer€ in error, would not

have to respond to the facts whlch

make up the substance of the settle-

ment. As e matter of fact, I would ask

the gentleman from lllinois, (Mr.

Ifyor) whether it is true that those

facts th&t led up to the consent decree

or s€ttlement of whatever nature

would be relevant and would be before

the courts to consider on their merits.

Mr. IIYDE Mr. Chalrman, wlll the

gentleman yleld?

Mr. LIINGREN. I will be happy to

yield.

Mr. HYDE. This ls a matter that

could have been handled in a colloquy

on the floor or tn the report. Consent

decrees may be very serious matters or

they could be trivial matters. It aU de-

pends on the substanee behind the

form of disposing of a controversy. All

I want is to permit the trial court to

look to the reality and the substance

rather than the form; that is all. I do

not want to let someone get out from

under preclearance iJ they have

abused an''one's voting rlghts, but I

want to encourage the-settlement of

litigation, let the parties get t,ogether.

Let us say that someone wanted four

voting booths in a black neighbor-

hood, and the election board gave

them three. The suit was filed. They

say, "You want tour, we will give you

five." Rather than dismiss the suit.

they put lt h the form a consent

decree. I would like the court to look

at that and say, "That does not bar

you from your bailout suit."

Or the courts could say it does. They

do not have to relitigate it, we do not

ha1'e to produce witnesses, but let the

court look at it and say to counsel,

"What is this all about?"

This ls simply a matter of not letting

a technicality bar a State from bail-

out.

H 694?

Mr. SENSENBRENNER. Mr. Chalr-

man, $rlll the gentleman yleld?

Mr. LUNGREN. I wlll be happy to

yield.

Mr. SENSENBRENNER. I ask the

gentlematr from Illinols (Mr. HyDE)

does not that tnvolve a trylng of sll

the lssues that were posed ln the sult

resolved by the conrent decree, wheth.

er they were guilty of votbng diserlml-

natlon?

Mr. IIYDE. No; lt Just means, nead

the decree, 6ay to couruel, "What a.re

the cireumstanees here, what was ln.

volved here," end mahe a determina.

tion-not relitigation.

The CHAIRMAN pro tempore. Tlre

time of the gentleman from Californle

has explred.

(At the request of Mr. Sen B. Iler.r"

Jn., and by unanirrious consent Mr.

LITxcREN wa-s allowed to proceed for 2

additlonal mlnutes.)

Mr. SAM B. IIAL& JR,. Mr. Ctrair.

man, wiU the gentleman yield?

Mr. LUNGREN.I yield.

Mr. SAM B. IIALL, JR. If you have

had e protracted case that had rea,m!

of testimony presen.ted before e dls-

trict Judge, who !s not present or ls not

avallable at the subsequent hearlng,

do you want that distrtct court to have

the right to go back Bnd look at that

prior case, &nd review all the evidence?

Mr. IfYDE. No, sir. If I were th

trial Judge end a consent decree w

brought to me, and I saw it was lhat

kind of heartng, I would say this

would be a har. There is fust too much

evldence.

Mr. SAM B. ITALI+ JR. Does not

that ln itself cut some of the merit out

of the gentleman's arnendment, lf you

just saw a thick record Lnd took that

to mean that, "Wel], we better not

erant this relief," that thick reeord

maybe would be Just as legitimate as a

short one.

Mr. HYDE. Yes, it would, but I Just

want to give the trial court some di:s-

cretion to make a judSment as to

whether this is a substantial situation

or whether it was just a settlement, ot

something that was trivial. The mere

fact that a consent decree was entered

into ought not to be a bar. They ought

to look to the reality and substance

behind it in a summary fashlon. That

is all, Other*'ise, you discourage ever

settling anything. You have to litigate

to the bitter end. I think that puts e

bar on the parties and the courts, that

is all. It is not an Earth-shaking

matter, just a matter of facilitating

the bailout procedure.

[Mr. BLIr.nY addressed the Com-

mittee. His remarks will appear here-

after in the Extensions of Flemarks.I

The CIIAIRMAN pro tempore. The

question is on the amendment offered

by the gentleman from Illinois (Mr.

Hyon).

The question was taken; and the

Chairman pro tempore announced

that the noes appeared to have it.

(

L

II 6948 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE Octofur 5, 1981

REORDED VOTE ldark5 porter Emtth (pA) AMENDMENT OFERED By ltR. BUTLEA

Mr. HYDE. Mr. chatrrnan, I demand U:[l;tlr", f,'S., !i&L.,. rrr..-surlER. Mr. chatrman, r offera fecOfded VOte. t[atsut R8hslt 6rark an amendment.

. +i:"i:t'i::" ry:rEl_1*,*,ie U#1,"' ilFffi Ei#,i:: ;ji':fs,:,?:.tr 1;,,;:1,.*R: paso

uiiilT' [iln;. *[i ;#:q''itilj**:***"gn;;;

A AyES--g2 Mc6rath Rt..er ii"ijl .r*, each place ll, appears and inserting ln lieu

'),".i.; fffltt Bll*. U:[l'fl", !St* V*Xi"," liiffi.t.,T appropriete unrted st.les dis'

Batrey (MO) n.nsen (rpr il;1, !1i"" Rmmer walFr€n RedesiSnate succeeding peragraphs ac--Bsrnard

'aruenito-

gffi* gii1ru ffi- g11Th #$**llffiffiffi;

Bedeu llartnett

Bliley HlltL6

Bowen Huckabt

Brinkley Hyde

BroyhlU Jeffrle!

Burgenet JenklruBue-'*n'"'

$Hii $I$f $iffi', $ilF,',, nt*,,,-*l-"ar,,*$},i,,$s$*.*#

C&mpbeu Eindneas

Camsn Krsmer

Chappie Lcgomrrsl

ColliE (T:r) Lce

Corcoran Loerner

Courtcr Irtt*ais - !-owervrcA, H"*l;' ili$i" $iHtit SSlt ..,B3gi,li#lii3;jjll." out "(B)" and rnsert

Crene, Donlel lerngren

D&nie'I Dan uarleni",

ffifl;. gf,rJ $l[,F*"' $l],$' ,,H!,,:,".*i#Ip"mtmtp:l

Dmiel. R. W. Martin (lir

Dem'lrEkl ldcclor'

Dickinson lf,ccollum

t Dreier u"Donsld ffiffi Panetta simon Yates Vottng Rlghts Act of 1965 are e&ch amended' Emerson rrrrrer iOnr i;-t';; Pattereon skm Yatron by striklna out "sectlon { or"..e'Ids M''k;'"v

ffiIh xi{* Efilil#,

Ysffitffii

:ti,if:ffi:*}##h:"gF:*

Ptndley l/loore

Flippo Moorherd

F'ount&ln MottlGoldser€r Myers yous (FL) NOT VOTING_56 ered As reAd and printed tn theGoodlinS NaDier Andrews Dingell Motfett FUrcoRo,

NOES-285 Ashbrcok Dosdy o Brien The CHAIRMAN pro tempore. IsAddabbo Derrrck g3T- f;il|"o, **::rd"

(At'}

#ff ",

there obJection to tn[ *q;"ri of theAkaka DicL6 unvanboGra Dtxon a;" t,araris piedl6r i,.;-*' gentleman from Virginia?

Atexmder oo-i-"rV d;;; *ltd Ford (TN) Pepper There wa-s no objection.

Anderson - D.'d;- g5".,Si"l !:fifi, !Iffi", *Tn",o _j:l3"""l-ous consent, Mr. Burr.snAnnunzlo Domananthony Dousherty E"ri. niLt :IT.a rleckler i*i""r.i'r.ri was allowed to proceed for an addi-

epplegitc D.fi;i-- fif,i: il#" Br.of,rr (cA) Horton Roth tional 5 mlnutes.)rrucoin D*;;

iifiigTlln-,o, EIi[#,i'* F"*S*", ilt?'- "#i,""fjfi.:#fld;?,1",f,lgLH;

Baile]'(PA) Dunn

Barnes Dr.yerBeilenson pl.ir"iry fiS[i. conable Iantos Thomas ls recognized for 10 minutes in support

Benedic Di;;- E;d;;. :91t" If,wis Traxler of his amendment.BenJsmtn d.lr'' H;;,iil Pulll*.., I,l,k:n llblS rrrr nrrm.nrr Lrr rt'.roim6n h^-+f,:HTI' ffi',L H;Hi gfliFi*n *:**.,", si,'fiL*,o", ort"iut"Yll*";#J;,"f""#H;,i?ilBereut€r EdgsBethune eaiara"rcel E;;;;. Dannemever Moaklev clearance requirements of sec,tion 5 ofBeIill Edrards (oK) rlertel - t D,^ the Voting Rights Act have beenBrasri Enettsh ltishtoler tr 1330 Under this requirement for 1? years.Bingham Erdahl HilerBranchard srrenborn . iili:r'r"o The Clerk announeed the following H.R. 3112 proposes to extend this 1?-Boland EHrl rtoDenbeck pairs: year period indefinitely with provisio

Borrer Eva$i (DE)

Bonior E'em(cA) 83I.,* Mr. psul for, cith Mr. Ford of rennessee !13!.-:l"h covered Staces or political

Bonker El.am gA) ;;il" asainst. subdi[ision will be relieved of this re-

B.gsr..a Eve.rB (rN) nugnes Mr. Edwards of Alabama for. with Mr. quirement Of preclearance if they canB'eaux IL'! HunLet JonesofNorthcarolinaagainst.'"'-'--' establish that certain facts or condi-Brodhead fbscellBroomrield rhzio f,:i*, Mr. Dannemever for, witn ur. Dingell tions desiSrred to a.ssure that the ob-

Brosn (co) r"*'icr j;;# sgainst. - jectires of the act have been achievedBroun(oH) Ferrr,ro Jefrords Mr. Chenel'for, c'ith Mr. O'Brien egainst. have existed fora period of more than

BI[r tt''o ffil,", j:lH [Ps), Mr. Baralis for. with u'. c.*"-"".t i.--' l0 years.

carnei plorto ;#;;;;i"r Mr. Philip M. Crane for. s'ith Mr. Horton In m}'' iudgment, many of these con-chisholm F'oclietta Kazen against. ditions &re unreasonable, if not impos-clrusen Folev 5:Tp Mr. Thomas for, with Mr. petrl aCainst. sible to-achieve; but the!, are the sub_Clal' Pord (MI)

clinser Fo^ythe H#ff="* Mr. Martin of North Carolina ior, nith ject -of other amend-ents. This

Cost.s rowtet i*rtr"i Mrs. Heckler ag&inst. amendment is addressed to the courtcotlho Fl.snk Latta Mr. Ttible for, wlth Mr. Lantos egainst. which must hear the petition for bail-Coleman ftenzel lf,achcouins(IL) ncsr Hatr, Messrs. IIUNTER, BENEDICT. oll'-^

-.conlen Ftqua rf,Bout,rier poRIqE, _ ryonriir,;,-"i^r,rl{g: o,Ii,i,,"I",,lll,r3i i|irl""l,j,ill?S ii!,,i-3|i;ll:#ilitr- 3"'iilL, ffllTo* siox, McDADE, wru,ric,mkerr cejdenson rant rana, and LEvITAS "n#"3'll??i :n*1!l' eonduc[ require-a--bv H.R.

D&nierson c.;6-.nt- r.€r.ir&s votes from ,.aye.' to;.no.;; -'""- 3ll2 clepends upon -its ability to prove

Da^schle ciuuons r,ii;t"e"ton '-.; -;;;;"^--;-

^::__ facts, many, many facts; and their rel-

tr*"' Sii#' ' *'ff:H, r.lH" f"*TI'*3" changed his vote ;;#fi; the rau'-berore us'

*1U,"" EitX'# frh-?#;,

--so

tr," amendmenr u'as reje*ed. r.ffi" ffii'T,iJii:"tffff[t""Jff.T

txuumi Gore roirain" The result of the vote \r,as an- them; and of course, to apply the lau.DeNardis Gradison uadisran nounced as above recorded. thereto.

l^7

(

October 5, 1981

In order for the courts to determlne

facts, the court must have access to

the people and the ctrcumstances they

observed and the mEnY other thtngs

whlch are relevant to lts determina'

tlon.

Indeed, lt would appear to be one of

the bases of due process that there

should be some reasonable relatlon-

shlp between the facts to be deter'

mlned and the locatlon of the court to

determine them.

Our Federal court sYstem' PartlY

through stBtute, and partlally through

case law, has developed the doctrine of

foram non conveniens which provldes

almost a rlght to a court trial tn the

most convenient place.

H.R. 3112 would provlde, however,

that 8ny State or polltical subdivlslon

desiring to be relieved of the preclear-

ance requlrements must prove lts facts

and argue before the U.S. District

Court for the District of Columbis;

and no other.

The amendment whteh I now offer

would permlt the case to be heard ln a

three Judse U.S. dlstrict court where

the petitioner is located where the

facts arose.

There are m&ny reasons whY thts

amendment ls an improvement upon

the biU and why lt ls more reasonable

to hear these cases where they arose

lnstead of Washlruton, D.C.:

In the first place, there is the matter

of convenience to the court. How can a

court br Washin€ton, D.C., really de'

termine the facts about a complex sit'

uation which could be as much as a

thousand miles eway?

Consider the expense to the parties:

On the one side, you have the unllm'

ited resources of the Federal Govern'

ment, with no real concern about the

cost of the litigation, a tremendous re-

source advantase, particularly when

you recall that the courthouse is but a

few blocks away from the Department,

of Justice.

On the other side, you will have the

petitioning political subdivision-let us'assume it is a county in Texas.

The county will have to have its own

local attorney in Texa.s, and, in addi-

tion, it will have to employ Washing-

ton counsel. And they are tremendous-

ly expensive-the litigating Washing-

ton lawyer is rapidly becorning the

highest paid specialist-if that is the

vord-within the legal profession.

Then you must consider the exPense