Answer in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion Requiring Defendants to Cooperate and Pay for a Desegregation Plan Prepared by Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

April 6, 1972

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Answer in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion Requiring Defendants to Cooperate and Pay for a Desegregation Plan Prepared by Plaintiffs, 1972. b03ac90c-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f4280ff6-db59-4463-8c0f-7969a66b6f1e/answer-in-opposition-to-plaintiffs-motion-requiring-defendants-to-cooperate-and-pay-for-a-desegregation-plan-prepared-by-plaintiffs. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

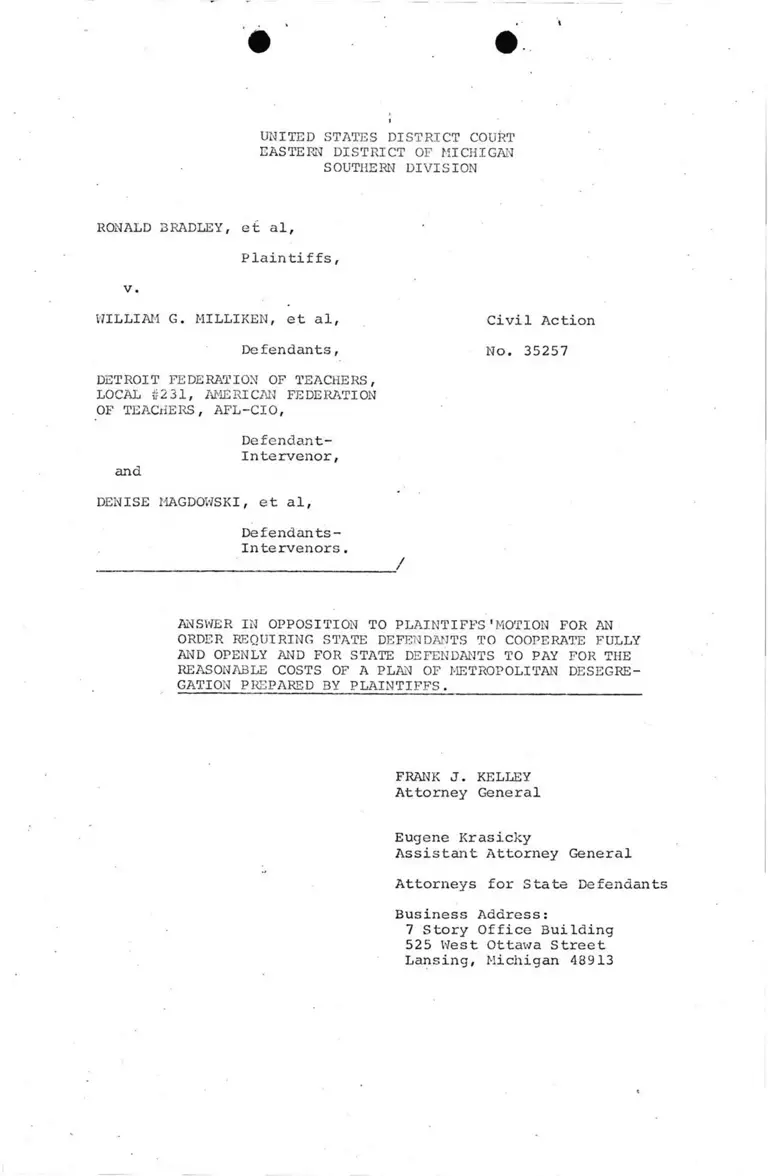

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, e t a l ,

P l a i n t i f f s ,

v .

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, e t a l , C i v i l A c t i o n

D e f e n d a n t s , N o . 3 5257

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #2 3 1 , AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

D e f e n d a n t -

I n t e r v e n o r ,

a n d

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, e t a l ,

D e f e n d a n t s -

I n t e r v e n o r s .

_______ ___________ /

ANSWER IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'MOTION FOR AN

ORDER REQUIRING STATE DEFENDANTS TO COOPERATE FULLY

AND OPENLY AND FOR STATE DEFENDANTS TO PAY FOR THE

REASONABLE COSTS OF A PLAN OF METROPOLITAN DESEGRE

GATION PREPARED BY PLAINTIFFS.

FRANK J . KELLEY

A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l

E u g e n e K r a s i c k y

A s s i s t a n t A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l

A t t o r n e y s f o r S t a t e D e f e n d a n t s

B u s i n e s s A d d r e s s :

7 S t o r y O f f i c e B u i l d i n g

525 W e s t O t t a w a S t r e e t

L a n s i n g , M i c h i g a n 48913

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN . DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, e t a l , .

P l a i n t i f f s ,

v .

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, e t a l , C i v i l A c t i o n

D e f e n d a n t s , No. 3 5257

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #2 3 1 , AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, '

D e f e n d a n t -

I n t e r v e n o r , ■

a n d

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, e t a l ,

. D e f e n d a n t s -

I n t e r v e n o r s . '

____________________________ ___ __________________/

ANSWER IN OPPOSITION TO PLA IN TIF FS ' MOTION FOR AN

ORDER REQUIRING STATE DEFENDANTS TO COOPERATE FULLY

AND OPENLY AND FOR STATE DEFENDANTS TO PAY FOR THE

REASONABLE COSTS OF A PLAN OF METROPOLITAN DESEGRE

GATION PREPARED BY P L A I N T I F F S . _________________________

Now come s t a t e d e f e n d a n t s W i l l i a m G. M i l l i k e n , G o v e r n o r

o f t h e S t a t e o f M i c h i g a n , F r a n k J . K e l l e y , A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l o f t h e

S t a t e o f M i c h i g a n , M i c h i g a n S t a t e B o a r d o f E d u c a t i o n a n d J o h n W.

P o r t e r , S u p e r i n t e n d e n t o f P u b l i c I n s t r u c t i o n , by t h e i r a t t o r n e y s ,

F r a n k J . K e l l e y , A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l , a n d E u g e n e K r a s i c k y , A s s i s t a n t

A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l , a n d make t h e i r a n s w e r i n o p p o s i t i o n t o t h e m o t i o n

o f p l a i n t i f f s , r e s p e c t f u l l y r e p r e s e n t i n g t o t h i s C o u r t a s f o l l o w s : 1

1 . The o r d e r o r d i r e c t i v e o f t h i s C o u r t o f N o v e m b e r 5 ,

1971 c o n t e m p l a t e d t h a t p l a i n t i f f s f i l e a l t e r n a t i v e m e t r o p o l i t a n

p l a n s a t t h e i r own e x p e n s e .

2 . The o r a l o r d e r o r d i r e c t i v e a n d w r i t t e n o r d e r o r

d i r e c t i v e o f t h i s C o u r t c o n t e m p l a t e d t h a t t h e S t a t e B o a r d o f

E d u c a t i o n , , a s t h e s t a t e a u t h o r i t y w i t h t h e p r i m a r y , b a s i c a n d

f u n d a m e n t a l r e s p o n s i b i l i t y i n t h i s f i e l d , s u b m i t a m e t r o p o l i t a n

p l a n a n d d e f i n e i t s p e r i m e t e r s ; t h a t d e f e n d a n t S t a t e B o a r d o f

E d u c a t i o n h a s c o m p l i e d w i t h t h e o r d e r o r d i r e c t i v e o f t h e C o u r t

a n d h a s s u b m i t t e d m e t r o p o l i t a n p l a n s , w i t h o u t r e c o m m e n d a t i o n , i n

s k e l e t a l f o r m , w h i c h d e f i n e t h e p e r i m e t e r s o f t h e m e t r o p o l i t a n

p l a n a n d d e s e g r e g a t e t h e D e t r o i t p u b l i c s c h o o l s y s t e m . S i n c e

t h e C o u r t ' s N o v e m b er 5 , 1971 o r d e r o r d i r e c t i v e h a s b e e n f u l l y

c o m p l i e d w i t h , a n d b e c a u s e t h e p l a i n t i f f s f a i l e d , w i t h i n t h e

t i m e a l l o t t e d by t h a t o r d e r o r d i r e c t i v e , t o p r o v i d e a l t e r n a t e

p l a n s a t t h e i r own e x p e n s e , t h e p l a i n t i f f s a r e e n t i t l e d t o n o

f u r t h e r r e l i e f a s s e t f o r t h i n t h e i r m o t i o n .

WHEREFORE, t h e s t a t e d e f e n d a n t s r e s p e c t f u l l y r e q u e s t t h a t

p l a i n t i f f s 1 m o t i o n b e d e n i e d .

FRANK J . KELLEY

A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l _

A s s i s t a n t A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l

A t t o r n e y s f o r S t a t e D e f e n d a n t s

B u s i n e s s A d d r e s s :

7 S t o r y O f f i c e B u i l d i n g

525 W e s t O t t a w a S t r e e t

L a n s i n g , M i c h i g a n 48913

D a t e d : A p r i l 6 , 1972

- 2 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I h e r e b y c e r t i f y t h a t on t h e 6 t h d a y o f A p r i l , 1 9 7 2 ,

I s e r v e d a t r u e c o p y o f t h e f o r e g o i n g A n sw e r i n O p p o s i t i o n t o

P l a i n t i f f s ' M o t i o n u p o n e a c h o f t h e f o l l o w i n g nam ed a t t o r n e y s o f

r e c o r d , b y m a i l i n g t h e same t o h im b y f i r s t c l a s s m a i l , p o s t a g e

f u l l y p r e p a i d , a d d r e s s e d t o h i s l a s t known a d d r e s s :

M e s s r s . L o u i s R. L u c a s '

a n d W i l l i a m E . C a l d w e l l

Mr. N a t h a n i e l R. J o n e s

M e s s r s . J . H a r o l d F l a n n e r y

P a u l R. Dimond a n d R o b e r t P r e s s m a n

Mr. E . W i n t h e r McCroom

M e s s r s . J a c k G r e e n b e r g a n d

Norman J . C h a c h k i n

M r r i o n\y~ r rm rP T J n n r n o 1 1 . T v

Mr. T h e o d o r e S a c h s

Mr. A l e x a n d e r B. R i t c h i e

Mr, K e n n e t h B . M c C o n n e l l

C o n d i t & M cG ar ry

Mr. W i l l i a m M. S a x t o n

M e s s r s . D o u g l a s H. W e s t a n d

R o b e r t B . W e b s t e r

Mr. R o b e r t J . L o r d