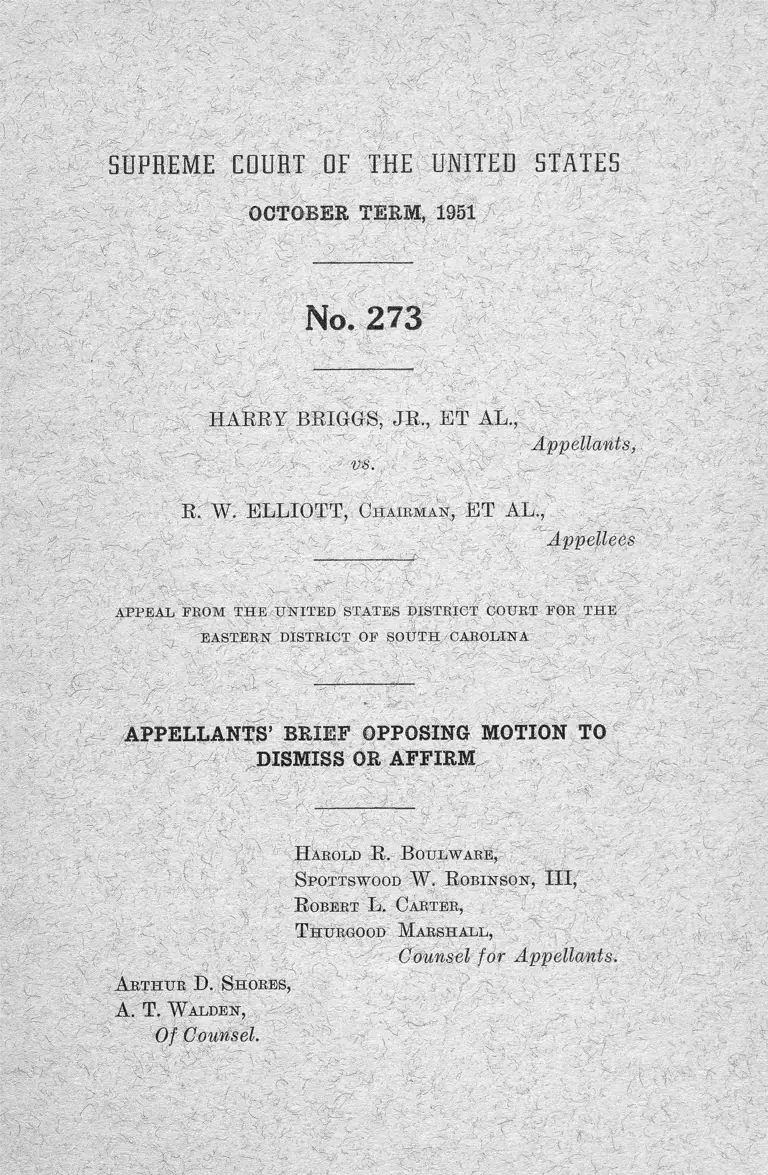

Briggs v. Elliot Appellants' Brief Opposing Motion to Dismiss or Affirm No. 273

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Appellants' Brief Opposing Motion to Dismiss or Affirm No. 273, 1951. 1af1517b-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f46b26c3-6ee1-44ba-922d-00231d111565/briggs-v-elliot-appellants-brief-opposing-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm-no-273. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

S U P R E M E COURT OF THE UN ITED S T A T E S

No. 273

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL.,

Appellants,

R: W. ELLIOTT, Chairman, ET AL.,

Appellees

APPEAL FROM TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF OPPOSING MOTION TO

DISMISS OR AFFIRM

H arold R. B oulware,

Spottswood W . R obinson, III,

R obert L. Carter,

- T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Appellants.

A rthur D. Shores,

A. T. W alden,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Appellees ’ Motion to Dismiss Should Be Denied. . . . 1

Appellees’ Motion to Affirm Should Be Denied......... 5,9

Conclusion .................................................................... 9

T able of Cases

Bostwick v. Brinkerhoff, 106 U. S. 3 ............................ 8

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Civil Action

No. T-316, — F. 2d — (D. C. Kansas), Decided

August 3, 1951.................................... 4

Carondelet Canal & Navigation Co. v. State of Louisi

ana, 233 U. S. 362 .............._ : ......................................... 8

Cumming v. Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528......... 1

Eichole v. Public Service Commission, 306 IT. S.

268 ............................................................................. 8

For gay v. Conrad, 6 How. 201 .................................... 8

Gong Lum v. Bice, 275 IT. S. 72.................................... 1

Gospel Army v. City of Los Angeles, 331 IT. S. 543... 8

Knox National Farm Loan Association v. Phillips,

300 U. S. 194.............................................................. 7

Market Street Railway Co. v. Railroad Commission,

324 IT. S. 548.............................................................. 7

McLaurin v. State Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637... 1, 3,4

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949; cert, denied

— IT. S. —, decided June 4, 1951.............................. 9

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337. . . . 9

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 FT. S. 537................................ 1

Radio Station WOW v. Johnson, 326 IT. S. 120. . . . . . 8

Rice v. Arnold, — IT. S. —, decided Oct. 10, 1950....... 5

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 332 IT. S. 631........................................... 6

Smith v. Al hr right. 321 IT. S. 649............................ 3

St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway Co. v.

Southern Express Co., 108 IT. S. 24........................ 8

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629................................... 1, 4

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 94 L. Ed. (Ad. Op.)

200 .......................... 9

Winthrop Iron Co. v. Meeker, 109 IT. S. 180............... 7

—7079

S U P R E M E COURT OF THE UNITED S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

No. 273

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL.,

vs.

Appellants,

R. W. ELLIOTT, Chairman, ET AL.,

Appellees

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF OPPOSING MOTION TO

DISMISS AND MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellees seek to avoid review of the decision of the

Court below by asserting: (1) that the question of the

validity of statutes requiring segregation. of the races in

elementary and high schools can not be questioned in the

light of the decisions of this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U. S. 537; Gumming v. Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528; and Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 IT. S. 78; and (2) that more

recent decisions of this Court including the cases of Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; and McLaurin v. State Board of

Regents, 339 U. S. 637 are not applicable because the Sweatt

case involved a law school and the McLaurin case was

limited to graduate education.

2

Neither Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, Gumming v. Board of

Education, supra, nor Gong Lum v. Rice, supra, preclude a

review of the decision in this case. Plessy v. Ferguson was

presented to this Court on a record which itself assumed

equality. The validity of racial segregation was not in issue

in Gumming v. Board of Education which was decided on

the question of the impropriety of the remedy sought. In

Gong Lum v. Rice, the gravamen of the action was the

objection of a Chinese child to being classified as a colored

person for school purposes.

The record in the instant case presents for the first time

competent, uncontradicted expert testimony sufficient to

enable this Court to make a critical analysis of the constitu

tionality of statutes requiring racial segregation in ele

mentary and high schools. No such evidence appeared in

the records of any of the cases considered controlling by

the appellees.

The testimony in the record in this case clearly distin

guishes it from the above cited cases. If, however, the

separate but equal doctrine of these cases is considered

applicable then it should be reexamined in the light of facts

now revealed for the first time in the present record.

“ In reaching this conclusion we are not unmindful

of the desirability of continuity of decision in constitu

tional questions. However, when convinced of former

error, this Court has never felt constrained to follow

precedent. In constitutional questions, where correc

tion depends upon amendment and not upon legislative

action this Court throughout its history has freely

exercised its power to reexamine the basis of its con

stitutional decisions. This has long been accepted

practice, and this practice has continued to this day.

This is particularly true when the decision believed

erroneous is the application of a constitutional princi

ple rather than an interpretation of the Constitution to

extract the principle itself. Here we are applying,

3

contrary to the recent decision in Grovey v. Townsend,

the well established principle of the Fifteenth Amend

ment forbidding the abridgement by a state of a citi

zen’s right to vote. Grovey v. Townsend is overruled. ”

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 665-6.

The issue in the case of McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 IT. S. 637, was “ whether a state may, after

admitting a student to graduate instruction in its state

university, afford him different treatment from other stu

dents solely because of his race.” (at p. 638). The unani

mous opinion of this Court decided: ‘ ‘ Appellant, having

been admitted to a state-supported graduate school, must

receive the same treatment at the hands of the state as

students of other races.” (at p. 642).

The issue in the instant case is whether a state which

undertakes to provide public education on the elementary

and high school levels for its residents can satisfy the

requirements of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment if it compels the segregation of Negro

pupils from all other pupils. The uncontradicted testimony

of appellants’ expert witnesses show that compulsory racial

segregation of pupils was harmful to the segregated stu

dents on the elementary and high school levels and deprived

them of educational opportunities and advantages equal to

those enjoyed by white students.

This Court found racial separation harmful and a depri

vation of the equal protection of the laws in the McLaurin

and Sweatt cases based upon expert testimony of the nature

presented at the trial of this case. In the majority opinion

the court below distinguished these two cases on the

grounds that they were meant to be applicable to only

graduate and professional education, whereas the dissent

ing judge felt that rationale of the McLaurin and Sweatt

cases should be applied in the disposition of this case.

4

In another recent case1 expert testimony similar to that

introduced in the instant case showed the effect of racial

segregation upon public school pupils in Topeka, Kansas.

The three-judge court of the United States District Court

for the District of Kansas included in its Findings of Fact

a finding that: “ Segregation of white and colored children

in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored

children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of

the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually

interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group.

A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to

learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has

a tendency to retard the educational and mental develop

ment of Negro children and to deprive them of some of the

benefits they would receive in a racial integrated school

system.”

In its opinion the Court said: “ It is vigorously argued

and not without some basis therefor that the later decisions

of the Supreme Court in McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U. S.

637, and Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 . . . show a trend

away from the Plessy and Lum cases.”

“ . . . If segregation within a school as in the McLaurin

case is a denial of due process, it is difficult to see why

segregation in separate schools would not result in the

same denial. Or if the denial of the right to commingle with

the majority group in higher institutions of learning

as in the Sweatt case and gain the educational advantages

resulting therefrom, is lack of due process, it is difficult to

see why such denial would not result in the same lack of due

process if practiced in the lower grades.”

The court, however, was of the view that the Stveatt and

McLaurin cases were limited to graduate and professional

1 Brown v. Board of Education o f Topeka, Civil Action No, T-316,

Decided August 3, 1951,

5

education. “ We are accordingly of the view,” the court

concluded, “ that the Plessy and Lwm cases . . . have not

been overruled and that they still presently are authority

for the maintenance of a segregated school system in the

lower grades. ”

“ The prayer for relief will be denied and judgment will

be entered for defendants with costs.”

Thus both in this case and in the Topeka case, supra,

lower courts have concluded that the principles enunciated

in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases are applicable to ques

tions of equal educational opportunities at the graduate

and professional school level only. Yet, that this is not the

view of this Court is apparent from its disposition of Rice

v. Arnold, ■— U. S. —, decided Oct. 10, 1950.

If a question involving segregation in the use of a mu

nicipal golf course must be remanded to the court below for

reconsideration in the light of the Sweatt and McLaurin

cases, as in Rice v. Arnold, it seems evident that the ra

tionale of these two decisions necessarily governs a deter

mination as to whether equal educational opportunities

have been furnished at the elementary and high school level.

Certainly the instant cause should be reviewed to remove

any ambiguity with respect to this question.

Appellees’ Motion to Dismiss Should Be Denied

The appellees take the position that this was an action

for a declaratory judgment to declare the Negro schools of

Clarendon County, South Carolina, unequal to the white

schools of that county and to enjoin the enforcement of the

statutes of South Carolina requiring racial segregation in

public schools—that there were two causes of action, one

which was finally determined and one which has not been

finally decided.

Appellants contend that there is but one cause of action,

that is, the effort to enjoin the enforcement of the statutes

6

of South Carolina requiring the segregation of the races in

public schools. This issue was clearly raised in the plead

ings, was supported by competent testimony and was de

cided by the District Court.

The appellees, having amended their answer to admit the

inequalities in physical facilities of the schools and having

consented to an injunction against these inequalities, the

only question in the case at the beginning of the trial was

the question of the constitutionality of the statutes. This

question was decided by the majority of the Court in its

decree which held that the enforcement of these statutes

did not violate the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment

and that appellants were “ not entitled to an injunction for

bidding segregation in the public schools of School District

No. 22.” The second paragraph of the decree ordered the

appellees to “ proceed at once to furnish to [Appellants]

and other Negro pupils of said district educational facilities,

equipment, curricula and opportunities equal to those

furnished white pupils. ’ ’

Appellees contend that this order is not final or review-

able by this Court because of the last statement in the

decree: “ And it is further ordered that the defendants

make report to this Court within six months of this date as

to the action taken by them to carry out this order. And

this cause is retained for further orders.”

The one issue requiring a three-judge Court has been

finally determined. The District Court refused to issue an

injunction restraining the enforcement of the statutes in

question. The other portion of the decree requiring equali

zation of physical facilities was likewise final. The court

could not have intended, as appellees contend, that the

appellees be given six months to equalize facilities, for to

do so would be contrary to the decisions of this Court.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631. In the absence

7

of a review by this Court all that remains is the question of

enforcement of the decree. All that is required is that the

appellees report to the Court within six months of the

“ action taken by them to carry out this order.” (Italics

ours.)

The latent powers of a court to reopen or revise its

judgment does not prevent a judgment from being final.

Market Street Railway Co. v. Railroad Commission, 324

U. S. 548, 551. In Knox National Federal Loan Association

v. Phillips, 300 U. S. 194, in an action to retire shares of

stock of a federal farm loan association where the lower

court granted the relief, appointed a receiver and reserved

the right to control the conduct of the officers and to rescind

or modify its order, this Court stated at page 137:

‘ ‘ The primary purpose of the suit was the recovery

of a judgment for the par value of the shares. Any

other relief prayed for or awarded was tributary to

that recovery; it was a form of equitable execution to

make collection possible. When the amount invested

in the stock was adjudged to constitute a debt, whatever

followed in the decree was auxiliary and modal. ’ ’

In Winthrop Iron Co. v. Meeker, 109 U. S. 180, 183 a

judgment containing a provision—“ And the Court reserves

to itself such further directions as may be necessary to

carry this decree into effect, concerning costs, or as may be

equitable and just” —was nevertheless a final judgment.

This Court stated:

“ The whole purpose of the suit has been accom

plished . . . the litigation of the case is terminated,

and nothing now remains to be done, but to carry what

has been decreed into execution. Such a decree has

always been held to be final for the purpose of an

appeal.”

8

See also: Carondelet Canal and Nav. Co. v. Louisiana,

233 U. S. 362; St. Louis Iron Wit. and Southern Railway Co.

v. Southern Express Co., 108 U. S. 24.

In the instant case the District Court ordered appellees

to furnish to the Negro pupils of the district “ educational

facilities, equipment, curricula, and opportunities equal to

those furnished white pupils.” Under this decree the only

thing remaining to be done is to furnish the facilities

ordered. No further judicial question exists. The litiga

tion of the parties as to the merits of the case is terminated.

All that remains for the Court to do is to police its order.

Such a decree is similar to the decrees where an equity court

decides the issues in a case and orders an accounting. This

Court has repeatedly held that such decrees are final.

For gay v. Conrad, 6 How. 201, 202; Radio Station WOW

v. Johnson, 326 U. S. 120.

Thus, where the judgment disposes of the whole case on

its merits and the court below has nothing to do but execute

its decree its order is final. Bostwick v. Brinkerhoff, 106

U. S. 3.

In making that determination this Court “ will examine

both the judgment and the opinion as well as other circum

stances which may be pertinent.” Gospel Army v. City of

Los Angeles, 331 U. S. 543, 548.

It should further be pointed out that there is no question

but that the Court finally and definitely refused to grant

the injunctive relief appellants were seeking—to enjoin

enforcement of the Constitution and statutes of South

Carolina, requiring segregation of the races, on the grounds

of unconstitutionality. Such an order is clearly reviewable

where the appeal is made pursuant to Title 28, Sections

1253 and 2101. Eichholz v. Public Service Commission, 306

U. S. 268.

9

Appellants, it is submitted, must seek a review of the

lower court’s decision at this time in order to avoid any

obstacle to this Court’s final determination as to whether

the statute and constitutional provisions of South Carolina

which require segregation of the races in public schools

conform to the requirements of the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Appellees’ Motion to Affirm Should Be Denied

Appellants’ rights to the equal protection of the laws are

present and personal. Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra;

Sweatt v. Painter, supra; McLaurin v. Board of Regents,

supra. At the time of the judgment in this case appellants

were entitled to a decree enforcing these rights. The only

way this could have been done would have been to order

that appellants be admitted into the schools set aside solely

and exclusively for white pupils in School District No. 22

and in the Summerton High School District without segre

gation or discrimination. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337; Sweatt v. Painter, supra; Wilson v. Board of

Supervisors, 94 L. Ed. (Ad. Op.) 200; McKissick v. Car

michael, 187 F. 2d 949.

To affirm the judgment in this case would be to establish

a precedent that the rationale of the Sweatt and McLaurin

decisions could not be applied to a case involving ele

mentary and high school education. An affirmance of the

judgment in this case would also mean that appellants’

rights to the equal protection of the laws could be postponed

to a future date.

Conclusion

The majority opinion of the District Court subordinated

the individual rights of appellants to the state’s segregation

policy. The rationale of the Sweatt and McLaurin cases,

10

swpra, was disregarded. Although the Supreme Court has

clarified the issue as to graduate and professional schools,

the Court has never had the opportunity to consider the

question as to elementary and high schools on the basis of

a full and complete record with the issue clearly drawn and

with competent expert testimony as appears in the record

in this case. A clear-cut decision on this issue will remove

all doubts in the field of public education.

For the foregoing reasons, appellees’ motion to dismiss

and motion to affirm should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

H arold R. B oulware,

Spottswood W . R obinson, III,

R obert L. Carter,

T huegood Marshall,

Counsel for Appellants.

A rthur D. Shores,

A. T. W alden,

Of Counsel.

(7099)