Summary of Discriminatory Practices at Hospitals Listed in April Letter

Press Release

April 17, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 2. Summary of Discriminatory Practices at Hospitals Listed in April Letter, 1965. 8ea487e0-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f64d45ee-bb90-4dc8-b548-23aca1b88194/summary-of-discriminatory-practices-at-hospitals-listed-in-april-letter. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

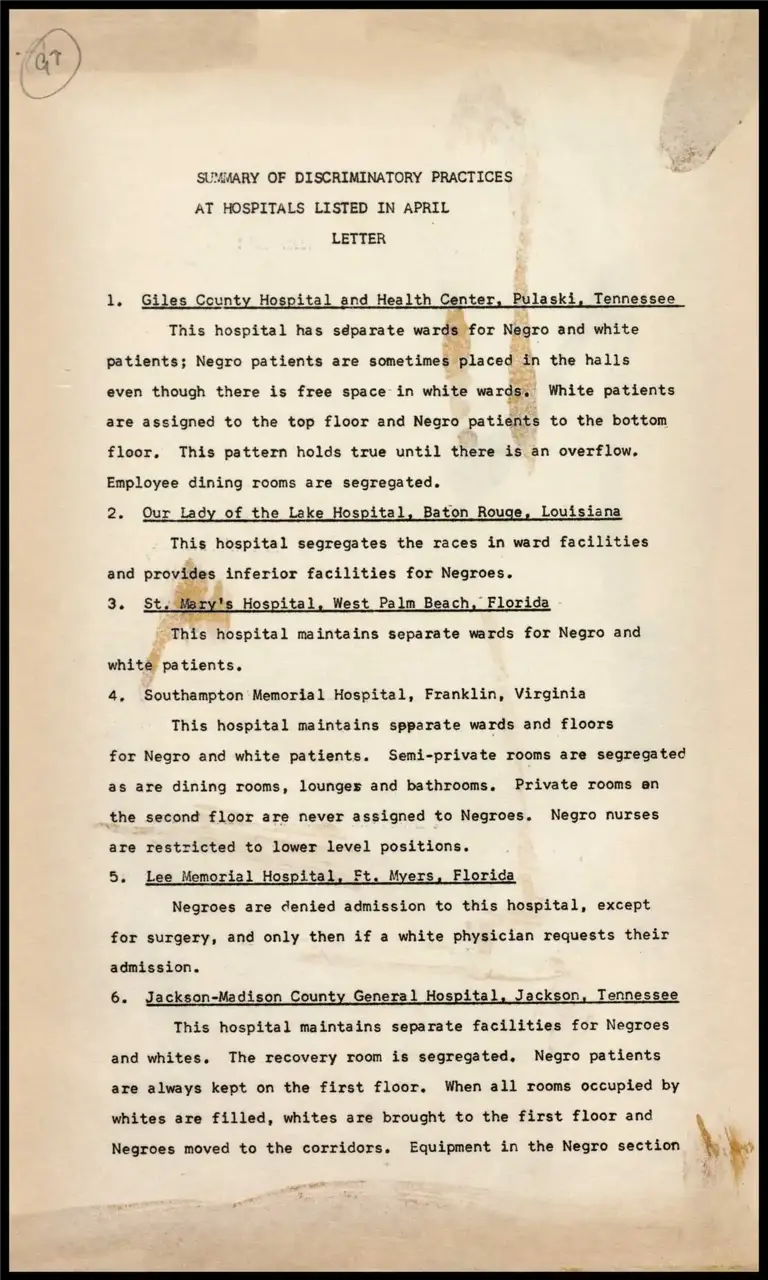

SUMMARY OF DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES

AT HOSPITALS LISTED IN APRIL

LETTER

1. Giles County Hospital and Health Center, Pulaski, Tennessee

This hospital has sdparate wards for Negro and white

patients; Negro patients are sometimes placed in the halls

even though there is free space in white wards. White patients

are assigned to the top floor and Negro patients to the bottom

floor, This pattern holds true until there is an overflow,

Employee dining rooms are segregated.

2. Our Lady of the Lake Hospital, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

This hospital segregates the races in ward facilities

and provides inferior facilities for Negroes.

7f

3. Sty fary's Hospital, West Palm Beach, Florida

This hospital maintains separate wards for Negro and

white patients,

4, Southampton Memorial Hospital, Franklin, Virginia

This hospital maintains spparate wards and floors

for Negro and white patients. Semi-private rooms are segregated

as are dining rooms, lounges and bathrooms. Private rooms an

the second floor are never assigned to Negroes. Negro nurses

are restricted to lower level positions.

5. Lee Memorial Hospital, Ft. Myers, Florida

Negroes are denied admission to this hospital, except

for surgery, and only then if a white physician requests their

admission.

6. Jackson-Madison County General Hospital, Jackson, Tennessee

This hospital maintains separate facilities for Negroes

and whites. The recovery room is segregated, Negro patients

are always kept on the first floor. When all rooms occupied by

whites are filled, whites are brought to the first floor and

Negroes moved to the corridors. Equipment in the Negro section

is inferior. Negro babies are always brought to the first

floor for parents to see, whereas white parents are allowed

to go to the second floor, or the obstetrics ward, to visit the

babies. There is a separate cafeteria for Negroes downstairs.

Ward-aids are provided for all floors with the exception of the

first floor, where Negroes are placed. Segregated hospital

lounges are maintained. Negroes are required to pay $50.00

deposit upon entrance to the hospital if they do not have some

type of hospitalization. This is not required of whites.

Negroes pay more for the rooms than whites and get inferior

service. At present a course in nurses aid work is in progress

at the hospital and no Negroes are enrolled although some

wanted to participate.

7. Qrange Memorial Hospital, Orlando, Florida

All Negro patients are restricted to the second floor

of the hospital (with the exception of "prominent" Negroes

who are sometimes given privat cual ot sections of

the hospital). The me training program and the student

nurses residence are restricted to whites only.

8. St. Vincent's Hospital, Birmingham, Alabama

This hospital maintains segregated facilities for

Negroes and whites.

9. Providence Hospital, Mobile, Alabama

This hospital segregates Negro and white patients in

rooms, wards, clinics, and eating places. Lounges, restrooms,

toilets, and other m also segregated. Negro doctors,

nurses, and technicians are not employed by the hospital.

Cualified Negro girls and young women are not admitted to the

hospital nursing school,

10. Mobile Infirmary, Mobile, Alabama

This facility maintains separate facilities of all

kinds for Negroes and for whites iy

11. Montgomery Baptist Hospital, Montgomery, Alabama

This hospital has refused to admit Negroes to medical

staff membership. It presently requires membership in e County

medical sdciety for staff membership. The County society ex-

ot a

_ cludes Negroes.

72-

12. Sarah Mayo Hospital, New Orleans, Louisiana

This hospital maintains separate facilities cor Negroes

and whites. Negro physicians are refused the privilege of

practising in the hospital, which requires that a physician

be admitted to the Orleans Parish Medical Society. The Society

restricts its membership to Caucasians.

13. Tours Infirmary, New Orleans, Louisiana

This hospital maintains separate facilities for Negroes

and whites. It refuses staff membership to Negro physicians.

It requires that, to be admitted to hospital privileges, a

doctor must be a member of the orleans Parish Medical Society.

The Society does not admit Negroes.

14. St. Patrick Hospital, Lake Charles, Louisiana

Negro patients, with the exception of obstetric cases,

are segregated by being placed at the east end of the hospital

on the basement floor. Towels and linen for Negro patients

are segregated from those used by whites.

Ree.

15. _Anniston Memorial Hospital, Anniston, Alabama

Separate wards are maintained; Negro petients generally

are placed in a section called Block I. Maternity facilities

are segregated and those accorded Negroes are inferior,

16. _Druid City Hos : uscaloosa, Alabama

This hospital maintains segregated wards, lobbies and

maternity facilities. Negro facilities are inferior to those

used by whites.

17. University Hospital, Birmingham, Alabama

Segregated general wards, nurseries, psychiatric wards,

emergency clinics, waiting rooms, registration desks, cashier

“lines and cafeterias are maintained. Many of the facilities

and services for Negroes are grossly inferior to those offered

whites. Negroes seeking emergency assistance are often treated

without consideration and relegated to inferior facilities.

Negroes are excluded from the School of Nursing and other

education programs as well as restricted to menial positions

and lower pay.

=ae siiieteniiin

18. Children's Hospital, Birmingham, Alabama

Spearate patient care areas are maintained a& well as Salet

segregated waiting rooms, registration windows and cafeterias.

Negroes are barred from employment in certain job categories.

19. Eye Foundation Hospital and Clinic, Birmingham, Alabama

Negro patients are segregated and receive inferior treat-

ment and a lower standard of care than whites. The cafeteria

is segregated. Negro employees are not permitted to use the

parking lot. Negro employees are excluded from promotion

opportunities and not eligible for certain jobs.

20. Crippled Children's Clinic and Hospital, Birmingham, Alabama

Negroes are not freely admitted to this hospital and

when permitted to receive treatment they are segregated in

patient care areas.» Lunch room and hot meal service are availabl«

for white employees only. Ne employment opportunities are

restricted. ~

21. Jefferson County Public Health Center, Birmingham, Alabama

Segregated waiting rooms are maintained. Negroes may

only attend out patient clinics on days when Negro patients

are being seen at the several clinics.

22, Good Samaritan Hospital, West Palm Beach, Florida

This hospital does not admit Negro patients. The presi-

dent of the hospital Board, Philip T. Sharples, recently stated

publicly that Negroes would not be admitted because "costs

would go up and income would come down."

23, Bethesda Memorial Hospital, West Palm Beach, Florida

Negroes and whites are placed in separate parts of the

building.

24. Okaloosa Memorial Hospital, Crestview, Florida

Negro and white patients are assigned to separate wings

of the hospital.

25. Jackson County Hospital, Marianna, Florida

This hospital assigns patients on the basis of race to

segregated wards.

Bek

26. Manatee Veterans Hospital, Bradenton, Florida

The wards in this hospital are segregated.

27. Florida Sanitorium and Hospital, Orlando, Florida

Wards and eating facilities are. segregated.

28. Morgan Memorial Rehabilitation Facility, Orlando, Florida

Wards and eating facilities are segregated.

29. Brevard Hospital, Melbourne, Florida

Segregated wards are maintained.

30. Indian River Memorial Hospital, Vero Beach, Florida

Segregated wards are maintained.

31. Tallahassee Memorial Hospital, Tallahassee, Florida

Negro patients are not accepted in this hospital.

32. Santa Rosa County Hospital, Milton, Florida

Segregated wards are maintained.

33. Baptist Hospital, Pensacola, Florida

Segregated wards and other facilities are maintained

in this hospital.

34. Americus-Sumter County Hospital, Americus, Georgia

3

pis hospital are rigidly segregated on

the basis of race.

35. Fort Walton Beach Hospital, Okaloosa, Florida

Patients are segregated in separate wards on the basis

of race. = xh

- Y et

36. Southeast Florida Sanitorium. Lantana, Florida

Separate wards and wings for Negro and white patients

are maintained.

ay

e

ra

yt

y:

-5-