Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Brief Amici Curiae, 1982. d58c4597-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f661b58a-3d2a-4676-a351-15c7a2c651fb/washington-state-v-seattle-school-district-no-1-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

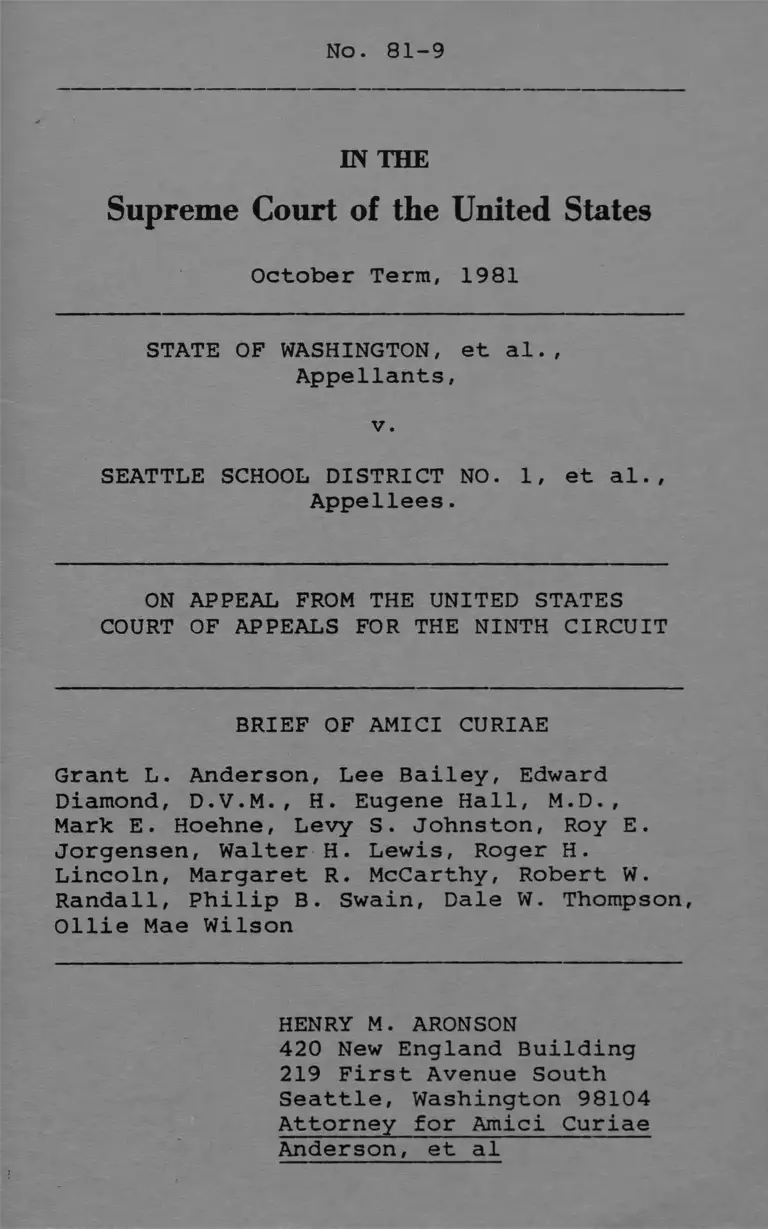

No. 81-9

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1981

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al. ,

Appellants,

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

Grant L. Anderson, Lee Bailey, Edward

Diamond, D.V.M., H. Eugene Hall, M.D.,

Mark E. Hoehne, Levy S. Johnston, Roy E.

Jorgensen, Walter H. Lewis, Roger H.

Lincoln, Margaret R. McCarthy, Robert W.

Randall, Philip B. Swain, Dale W. Thompson,

Ollie Mae Wilson

HENRY M. ARONSON

420 New England Building

219 First Avenue South

Seattle, Washington 98104

Attorney for Amici Curiae

Anderson, et al

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

Table of Contents i

Table of Authorities ii

Motion for Leave to

File Brief as Amici 1

Interest of Amici 3

Summary of Argument 6

Argument 7

Conclusion -_r 14

• •11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Martin _Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ., 626 F.2d 1165

(4th Cir. 1980), cert. denied

68 L.Ed.2d 238 (1980)

Miscellaneous

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

With All Deliberate Speed:

1954-19?? at 1 (1981)

Rossell, School Desegregation

and Community Social Change,

57~Law & Contemp. Probs. 133,

163-67 (1978)

14

8, 9

11

No. 81-9

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al.,

Appellants

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE '

This motion for leave to file the

accompanying Brief as amici curiae is

respectfully made pursuant to Rule 36 of

this Court. Written consent to the filing

of this brief has been granted by appellee

school districts and appellee Seattle

intervenor plaintiffs, and a true copy of

2

such consent is attached to the certificate

of service filed herewith. Amici expect

that written consent of the other parties

to this proceeding is forthcoming.

The nature of amici's interest in this

matter and amici's reasons for seeking this

leave are stated in the accompanying brief

under "Interest of Amici"; that discussion

is incorporated in this motion.

Dated January 25, 1982.

Respectfully submitted,

HENRY M. ARONSON

Attorney for Amici Curiae

Anderson, et al

3

No. 81-9

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al. ,

Appellants

v .

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI

Amici Grant L. Anderson, Lee Bailey,

Edward Diamond, D.V.M., H. Eugene Hall,

M.D., Mark E. Hoehne, Levy S. Johnston, Roy

E. Jorgensen, Walter H. Lewis, Roger H.

Lincoln, Margaret R. McCarthy, Robert W.

Randall, Philip B. Swain, Dale W. Thompson,

and Ollie Mae Wilson are individual

4

citizens of the State of Washington who

believe in the educational value of deseg

regated public schools. Each of these 14

amici is one of the 15 members of the

Washington State Board of Education ("State

Board"). With the exception of one indi

vidual, who in his official capacity

represents Washington State's private

schools on the State board, amici represent

a geographical cross-section of private

persons in the State of Washington, since

the State Board consists of two persons

from each of Washington's seven Con

gressional districts. In their official

capacities, the members of the State Board

neither authorized nor consented to the

filing on their behalf of the appeal in

this case, see J.S. D-3.

The State Board of Education in

October 1978 adopted the language of the

Joint Policy Statement with the Washing

5

ton State Human Rights Commission, J.A.

65-69, defining racial isolation and

declaring the responsibility and duty of

Washington school boards "to assign chil

dren to buildings in ways which result in

the maximum desegregation possible by

whatever means that are necessary."

These amici as individuals subscribe to the

views expressed in the Joint Policy State

ment .

Also in October 1978, the State Board

passed a resolution condemning Initiative

350 as "motivated by the sole purpose of

overturning the Seattle Plan for desegrega

tion of that District's schools" and

"harmful for education." J.A. 69-70 (The

Joint Appendix fails to clearly indicate

the division (in the middle of J.A. 69)

between the Joint Policy Statement and the

Resolution, and omits the word "harmful" at

J.A. 70. ) See PI. Ex. 117.

6

Amici seek to present to the Court

some of the educational and social policy

reasons for public school desegregation,

including the views of the U.S. Commission

on Civil Rights, which the parties, due to

their concentration on legal issues, have

not emphasized.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amici believe that this Court should

affirm the Court of Appeals' judgment in

this case, 633 F.2d 1338 (9th Cir. 1980),

so as to encourage the voluntary action of

local authorities designed to promote equal

educational opportunities and protect

constitutional rights. First, there are

important and significant educational

advantages for all children, and especially

minority children, in a school system which

is desegregated. Second, the argument that

mandatory desegregation is counterproduc

7

tive because it causes massive "white

flight" is a dangerous myth, often cited

as a reason to maintain segregation, which

must be dispelled. Third, if laws like

Initiative 350 are permitted to stand, then

the most effective desegregation plans—

those devised and supported by local school

authorities— will give way to exclusively

court-ordered plans, which are not infre

quently accompanied by hostility and

turmoil. This Court must not block the

successful, voluntarily-enacted desegrega

tion plans of Seattle, Tacoma, and Pasco,

and plunge those cities into the years of

racially polarizing, divisive litigation

that would certainly follow.

ARGUMENT

A . Initiative 350 Would Interfere with the

Nation11 s Essential Task to Desegregate

Public Schools

Amici agree with the U.S. Commission

on Civil Rights that

8

school desegregation is the single

most important task confronting the

Nation today in the field of civil

rights. Any retreat in our efforts to

achieve this goal will seriously harm

our efforts to move forward in other

civil rights areas. Further, ...

progress in desegregating our Nation's

schools will not be achieved without

the clear support and leadership of

government officials at the national,

State, and local levels. ... [T]hose

in positions of responsibility [must]

make such a commitment.

The commitment ... must be made today

so that children may be educated in

environments where they will come to

know one another as human beings and

to learn that all people are truly

created equal....

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, With All

Deliberate Speed; 1954-19?? at 1 (1981)

(hereinafter cited as With All Deliberate

Speed).

There is no longer serious doubt that

school desegregation can be correlated with

long-term achievement gains for minority

students, with no corresponding decline in

white students' performance. See, e.g.,

9

the studies cited in With All Deliberate

Speed, supra, at 40-44. And of equal or

greater significance than scores on stan

dardized tests is th<e fact that minority

students who have attended desegregated

schools succeed in college at signifi

cantly higher rates than those who have

attended segregated schools and have

greater social mobility, id^ at 43-44.

It does not deemphasize the importance

of teaching fundamental skills to all

children to point out that the public

schools have yet another critical task:

preparing young people to become citizens

in this Nation's ethnically diverse democ

racy. We think it self-evident that

enhanced interracial understanding, so

crucial to curing some of the Nation's

social ills, can only occur through the

prolonged exposure, from an early age, to

persons of different backgrounds. Respect

10

and appreciation for different ethnic

groups simply cannot be taught strictly

from a book — it must be learned from

first-hand experience.

B . School Desegregation is a Prerequisite

to Achieving Residential Integration

All who believe in public school

desegregation would prefer that it could be

accomplished without "busing". But re

search shows that without school desegrega

tion, housing segregation will only worsen.

It is nearly an article of faith in

the popular media that busing causes so

much "white flight" from public school

systems that it is counterproductive. Much

of this misconception is attributable to

failure to recognize that with or without

desegregation, white enrollment in urban

areas has declined sharply over the past

two decades and continues to do so. But in

fact, while there is no dispute that white

11

enrollment loss increases in most school

systems in the year of implementation

of a mandatory desegregation program, the

long-term effects of school desegregation

appear neutral or even positive. Rossell,

School Desegregation and Community Social

Change, 57 Law & Contemp. Probs. 133,

163-67 (1978). As initial apprehensions

decrease and income constraints take

precedence, some whites return to the

public schools from private schools. More

importantly, however, the guarantee of

desegregated schools helps retain white

families who would otherwise move out of

minority or "transition"-area schools.

Over time, segregated schools result in as

much or more white enrollment loss than

desegregated schools, because without

school desegregation, whites in greater

numbers leave the areas undergoing change

from majority to minority status, and are

12

not replaced.

Thus, failure to desegregate schools

only feeds the relentless, mutually rein

forcing dynamic between school and housing

segregation, and guarantees that schools

will become more segregated. The District

Court in this case, after extensive testi

mony and voluminous documentary evidence,

recognized these facts. J.S. at A-25

(Finding of Fact 11.3). See, e .g ., PI.

Ex.. 36, Tr. 133; PI. Ex. 37, Tr. 132; Pi.

Ex. 93, Tr. 357; and PI. Ex. 138, Tr. 2005.

Because residential segregation

will only worsen without school deseg

regation, and in turn intensify

school segregation, school desegregation

must continue so as to permit residential

integration to occur.

C . Locally Controlled Rather than

Court-ordered School Desegregation

Must be Favored.'

Finally, if this Court upholds

13

Initiative 350, it will likely be replicat

ed all over the country. As a result, only

court-ordered, and not school board-

adopted, desegregation will occur in the

future. This Court should encourage and

protect the efforts of local officials

toward school desegregation, especially

since local leadership is such a critical

element in the success and peaceful imple-

mentation of desegregation plans. The

experience of Seattle, Tacoma, and Pasco,

where desegregation has been peaceful and

has successfully been "institutionalized"

by the school system, stands in sharp

contrast to the experience in Boston,

Cleveland, and other cities where local

political leadership fomented resis

tance to court orders and fanned the fires

of racial fears.

Once cities have desegregated their

schools and experienced desegregation's

14

benefits, there is widespread distaste for

returning to segregation. See, e^g^,

Mar t in_v_._Char lotte-Mecklenburg Bd ._of

Educ., 626 F .2d 1165 (4th Cir. 1980), cert,

denied, 68 L.Ed.2d 238 (1980) (upholding

school board's authority to continue

desegregation plan where federal court's

equitable powers have lapsed).

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, amici

respectfully submit that the judgment of

the Court of Appeals should be affirmed.

Dated this 25th day of January, 1982.

Respectfully submitted,

HENRY M. ARONSON

Attorney for Amici Curiae

Anderson, et al