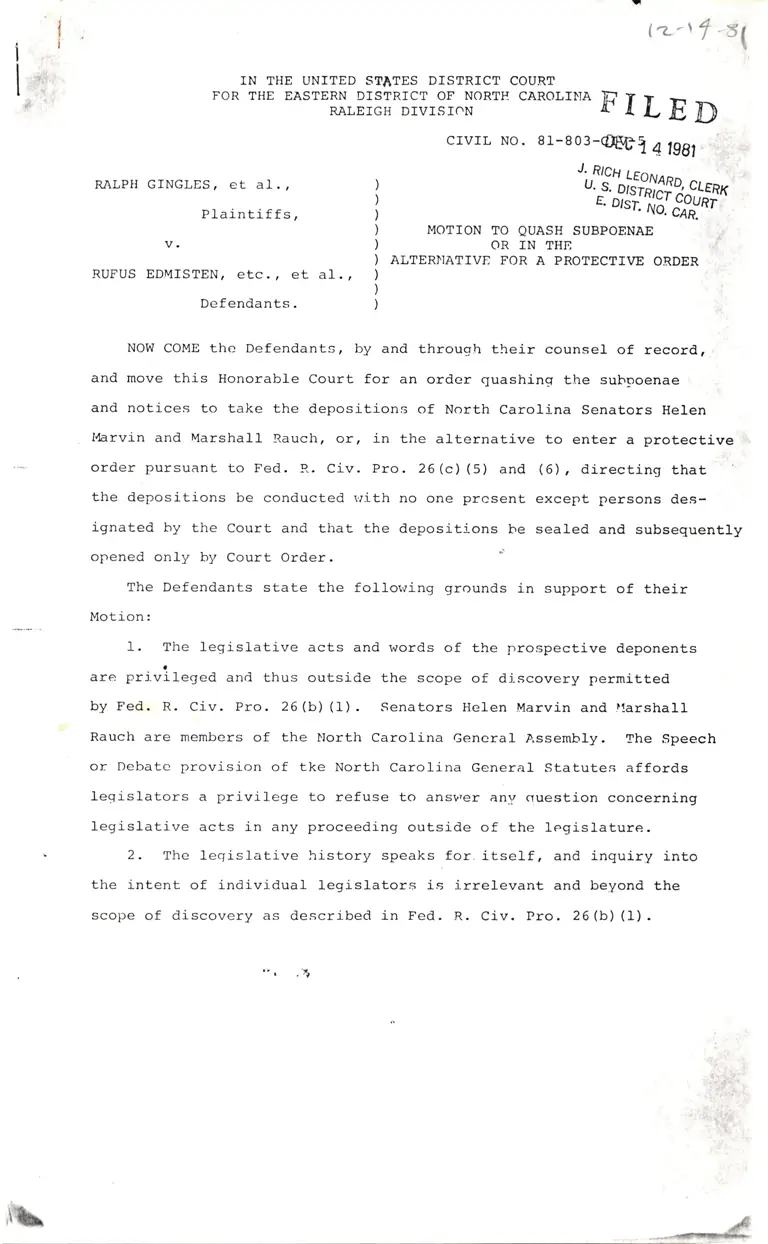

Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order

Public Court Documents

December 14, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order; Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Quash Subpoenae or in the Alternative for a Protective Order, 1981. bf342622-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f72a1436-f47a-4ec2-8b75-57e5ed0362a6/motion-to-quash-subpoenae-or-in-the-alternative-for-a-protective-order-brief-in-support-of-defendants-motion-to-quash-subpoenae-or-in-the-alternative-for-a-protective-order. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

t

,

li

l

(<_-, 1 3l

IN THE UNTTED STATES DTSTRICT COURT

J. R,CH T,: ;Xi.,Tdf?r?.rT,

MOTTON TO QUASH SUBPOENAE

OR IN THII

ALTER].IATIVE FOR A PROTECTIVE ORDER

FoR rHE totttlX"SlffTffr3lniln*'I{ cARoL*o

F.' I L E D

crvrl No. 81-8og-qts?

4

'g8l

RALPH GINGLES, €t aI. ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS EDMfSTEN, etc., et a1.,

Defendants.

NoW COME the Defendants, by and through their counsel of record,

and move this Honorable Court for an order guashing the suhS:oenae

and notices to take the depositions of North Carolina Senators Helen

l'larvin and Marshall Rauchr or, in the alternative to enter a protective

order pursuant to Fed. P.. civ. Pro. 26(c) (5) and (6), directing that

the depositions be conducted v.ith no one prcsent except persons des-

ignated hy the Court and that the depositrons he sealed and subsequently

opened only b), Court Order. ''

The Defendants state the follolvinq grounds in support of their

Motion:

1. The leqislative acts and words of the prospective deponents

a

are prj-vileged and thus outside the scope of discovery perm5.tted

by Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 26 (b) (1). Senators Helen Marvin and llarshall

Rauch are members of the }Iorth Carolina General Assembly. The Speech

ol: Debate provision of tke North Carolina General Statutes affords

leqislators a privilege to refuse to ansvrer anv fluestion concerning

legislative acts in any proceeding outside of the legislature.

2. The legislative history speaks.for itself, and inquiry into

the intent of individual legislators is irrelevant and beyond the

scope of discovery as described in Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 26(b) (1).

| . ,,

,lt\

irl\l\ I \r,Lrt\.1.

ltllf i'i11 t:AS1'ERN DIs'r'ltlr-l'i' 0[' N()R'l'I, CAllr.rLf]lA ]f f r

-RALEI(;IIDIVISTON X.'LLf,tr)

crvrL No. 81-803-(}Fe'l

4

'gB,I I I tt I

I

I

I t r ,t t,,tt l,r 'rIl t,ll l,tlltl,ltlllltltt

I tl r tlt.

, r. . . t/,t) :.,"/t. /.fi,#r?

Nol\7 coME the Defendants, b), and throuoh their counsel of record,

and mc\-e this Honorat,le Court for an order guashinq the suhpoenae

and notices to take the depositions of North Carolina senators Helen

I{:rvin atrd r'hrshal I \'rr.tt'tt, o\r, in t t,.e :r1t orn.rt ivrr to ottt.er s pto[eetlvg

order pursuant to Fed. p.. Civ. pro. 2G (c) (5) and (6), directing that.

the depositions be conducted rrith no one prcsent except persons des-

ignated by the court and that the deposit'i ons be seared and subsequentry

opened only b), Court Order

The Defendants state the follorving gr,rrl.ra= in support of their

Motion:

1 ' The fegislati-ve acts and words of the prospective deponents

are pri'vileged and thus outside the scope of di-scovery permitted

a

by Fed' R' Civ' Pro. 26(b) (1). senators Helen Marvin and tlarshall

Rauch are members of the llorth carolina Gencrar AssemLrly. The speech

o:: Debate provision of tke North carolina General statutes affords

legisrators a privilege to refuse to ansv,er anv ouestj-on concerning

legislative acts in any proceeding outside of the legisl_ature.

2. The legislative hi_story speaks for. itself, and inquiry into

the intent of individual regislators is irrerevant and beyond the

rtc()l,o rtf t'li t;crr )vnl-y ir,i rjr:rjr_-rilrrtrl in [,.cr]. n. C j v. pro. 26 (h) (l) .

', l',',!,'','

t,

!1,1,1,1,,i 1,1 )t, f 1

11,i,,

h lM

.I

b

FTT ED

IN TTIE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COUI1T flTn

FOR THE DASTERN DTSTRTCT OF NORTH CAROLT)'IA -(-t', I 4 lg}l

RALET.H Drvrs'olrur"

*o. r-'$rtg?ffflo3*

RALPH GINGLES, €t. a1.,

Plainti ffs ,

v.

RUFUS EDMISTEN, etc., et af.,

Defendants.

BRIEF' IN SUPPOP.T OF DEFENDANTS I

I'IOTION TO qUASH SUBPOENAE OR IN

THE ALTEPNATTVE FOR A PROTECTT\TE ORDER

I.

INTP.ODUCTION

Plaintiffs have subpoenaed Nortir Carolina Senators Helen Marvin

and l4arshal1 P.auch for the purpose of taking their depositj-ons on

December l?, 198I. The prospective de1'ronents, members of- the }Iorth

Carolina General AssembIy, are not parties to thls action. Defendants

contend that the matters about which l4arvin and Rauch rvould be

.asked

to give testimony are prj-vi1eged, hence non-discoverable under Fed. R.

Civ. Pro. 26(b) (1), and that such matters are irrelevant to the action,

hence also non-<liscoverahle under Fed. P.. Civ. Pro. 26 (b) (1) .

TIIE DOCTRINE OF LEGISLATIVE PRIVILEGE PREVENTS INQUIRY INTO

r,dGfs f,at r ve-AmS-6n rE-r-l,rbTmffi

Rule 26 (b) (1) specifically excludes from the scope of otherlise

discoverable material matters which are privileged. The common-law

doctrine, variously referred to as legislative privilege or legisla-

tive immunity, affords legislators a p::ivilegre to refuse to answer

any questions concerning legislative acts in anv proceeding outside

of the legislature. ges , 415 F-Supp. 1025

(O. Md. I976). This concept is codified in I'1.C. Gen. Stat. 5120-9,

which guarantecs freedom of speech and debate in the legislature and

in the legislative p.o."=".1

l', .)9

]rhe Section reads as follovrs:

,'The members shal1 have ^f reedom of speech and debate in

the General Assembly, and shall not hre liable to impeachment

or qucstion, in any court or place out of the General

Assembly, for vrords therein spoken; and shall be protected

except in cases of crime, frora all arrest and imprisonment,

or attachment of propertY, during the time of their going to,

coming from, ot attending the General Assembly. "

L

/

I

-z-

North Carolina's statutory provision paralleIs the Speech or

Debate Clause of the Federal Constitution (ert. T, 56), as well

as the statutory and constitutional enactments of most other

states. In interpretinq the federal constitutional version of

this doctrine the United State Supreme Court has written:

The reason for the privilege is clear. It i.ras

well summarized by James Wilson an influential

member of the Committee of Detail which r.ras

responsible for the provision in the Federal

Constitution. "In order to enable and encourage

a representative of the public to discharge his

public trust trith firmness and success, it is

indispensably necessary, that he should enjoy

the fullest liberty of speech, and tt.at he

should be protected from the resentment of every

one, however porverful, to vhom the exercise of that

liberty may occasion of fence. " Tenney v. p,roadhove,

341 U.S. 367 (1951) at 372-73 (cltaEions omr.Effil ._-

Legislativo privilege has a substantive as we-l-1 as evidentiary

aspect, and both are founded in the rationale of legislative

integrity and independence, enunciated by the Framers and propounded

two centuries later by the Suprerire Court. The substantive aspec,t

of the doctrine affords legislators immunity from civil anrl criminal

liability arising from legislative proceedinqs. The evidentiary

aspect. affords legislators a privilege to refuse to testify about

legislative acts i.n proceedings outside the legislative haIIs. United

State v. lIandel, supra at 1027.

At issue here -is the evidentiary facet of the privilege and,

specifically, whether such a state-afforderl evidentiary privilege

should have efficacy in the federal courts. It is clear that the

SPeech or Debate Clause of the federal constitution vrould preclude

the deposition of a member of Congress in an analogous situation.

In Brewster v. United States, 408 U.S. 508 (1975), the Court stated,

"It is beyond doubt that the Speech

inquiry into acts that occur j-n the,,, ,Tprocess and into the motivation for

or Debate clause protects against

regular course of the legislative

those acts," 40B U.S. at S2S.

I

/

/

-3-

Defendants acknowledge that even the privilege granted federal

legislators is hrounded by countervailinq considerations, particularly

the need for every man's evidence in federal criminal prosecution.

As Brewster further states, "the privilege is hroad enough to insure

the historic independence of the Legislative Branch . but narrow

enough to guard against the excesses of those who woul<i corrupt the

process by corrupting its memhers.,, 409 u.s. at 525. Defendants

motion attempts, however, to conceal no "corruption,,.

I{ith the boundaries of the federal legislative privilege in

mindr wQ turn to the question of the scope of paral1e1 state privileges.

Whatever thcir extent and range of applicability in state court, the

United States Supreme Court has ruled that state privileges vri1l, &t

times, yeild to overriding federal interests in federal courts.

ufgq Stateg v. 9i11ock, 100 S . Ct. 1185 (f 9BO ) . The Court has

recognized only one federal j-nterest of importance sufficient to

meri-t dispensing with this state-granted privilege: the prosecution

of federal crimes.

The Supreme Court has never sqt:arely adclressed the issue presented

here: ,whether a state legislator's evidentiary privilege remains

intact in federar civil proceedi-ngs. rr @r 9upra,

tl're Court ruled that a legis.l-ator's aglllentavg. irnmunity from suit

withstood the enactment of 42 U.S.C. 51983, and thus state legislators

were not susceptible to suit for r.rords and acts vrithin the purvievr

of the legislative process. Although it deals r+ith the substantive

aspect of the privilegc, Tenney is instructive, insofar as the Court

there gave great deference to the state's own doctrine. Recently,

in Eitea states v. ciloc]!, supra, a criminal case involving the

evidentiary facet of legislative immunity, the Cortrt cited Tenney

for the propositign thEt all federal courts must endeavor to apply

state legislative privilege. In Gillock, horever, the Court ruled

-4*

that the Tennessee speech or Debate clause would not exclude

inquiry into the legislative acts of the defendant-legislator

prosecuted for a federal criminal offense.

Throughout thc supreme court's activity in this fierd no

distinction has been drawn betvreen substantive and evidentiary

applicatj-ons of the privilege for the purpose of determining the

efficacy of legislative privirege in federal court. Thus, the

court's conclusions i" glrfgrx and Tcnney must be read together,

and their comhined effect dictates that the evidentiaryr privilege

granted a legislator by his state remains inviolahle except where

it must yield to the cnforcement of federal criminal statutes.

See Gil-l-ocl: at 1193 .

Unless fedcral criminal prosecution demands othen.zise, "the

rore of the state legislature is entitled to as much judicial

respect as that of Congress . The need for a Conqress vrhich may

act free of interference by the courts is neithe:: more nor less than

the need for an unimpaired state legis1ature." Star Distributors, Ltd

y-:_lggn_g,6l-3 F.2d 4 (1980) at 9. On this fundamental point the

supreme court has recently said, "To create a system in which the

a

Bill of Rights monitors more closely the conduct of state officials

than it does that of federal officials is to stand the constitutional

design on its head." Butz v. Economou, 428 Il.S. 478 (1978) at 504.

In the present civil action, brought by private citizens of

llorth Caro1ina, Legislators llarvin and Rauch are privileged to refuse

to testi-fy concerninq their legislative acts. Principles of comity

and the decided 1aw strongly suggest that federal courts honor this

evidentiary privilege in all civil actions.

IT THE I.TATERIAI SOUGHT TO BE DISCOVERED TS IRRELFVAI.IT.

The North Capoliqa House,

plans chal-lenged in this liti

Senate, and

gation speak

Congressional

for themselves

reapportionmen r

. Insofar as

f,n'

-l',-

the intent of the legislature is in question, the legislative history,

i'e', the contemporaneous record of debate anc enactment, reveals the

legislative intent. The remarks of any singre legislator, even the

sponsor of the bi11, are not controlling in analyzinc legislative

history. , 44L U.S. 2Bt (1929). That

such remarks have any relevance at all precludes that they were made

contemporaneously and constitute part of the record. See United

state v. Gila River pima-I1@community, 5g6 F.2d 2og

(ct' cl-' 1978). This proposition is adhered to even more strongly

by the appellatc courts of North carolina. The North carolina supreme

court, for example, stated the following in D & I^1,-.rnc. v. charlotte,

268 N.C. 577, 581, 151 S.E.2d 24t, 244 (1966):

". l.lore than a hundred years ago this Courtheld that Ino evidence as ta the motives of theLegislature can be heard to give operation to, orto take it from, their acts. . Dral<e v. Drake.15 N.c. 110, 117. The meaning of a sEEEEE-E-il-tlt'intention of the legisrature wtricr, passerl it cannotbe sho.n by the. testimony of a memhlr of the legisra-ture; it 'must be drarvn from the construction oi th;Act itself .' Goins v. Irdr_gr,_frgl11ing School , L6gN.C. 736, 739,-T6- ilE.-TTg,-?-IT:,

The testimony of Marvin and Rauch is

of the peneral Assembly and can have no

Thus, titeir dcpositions are outside thc

discovery.

not relevant to the intent

other discernable relevance.

scope of pcrmissible

IIT. PRESERVATION OF LEGTSry\lryq_JxqIlxliqE!.JcE REQUr RE.s THAT, SHOT.TLDTHE OS]TI ROCF:ED,

-THEY

MU SE.P,

rf the court orders the depositions to proceed, it is imperative

that thc transcripts he sealed and opened only upon court order. The

purpose of legisrative privilege is to "avoid. intrusion by the

Executive or the Judiciary into the affairs of a co-equal hranch,

and - to protect legislative inrlependence." Gillock at 1I9I.

.T

H

-5-

Legislators must feel free to discuss and ponder the plethora

of economic, social, and political considerations which enter into

legislative decision-making. Fear of subsequent disclosure of an

individual legislator's intent or rationale rvould ch111 <lebate and

destroy independence of thought and vote. In this case, sensitive

political considerations might be recklessly exposed by the Plaintiff's

proposed discovery. To maintain free expression of j-deas vrithin the

General Assembly, as well as to protect those ideas already freely

cxpressed therein, a protecti-ve order must issue, if the subpoenae

are not quashedr ds they should be.

Respectfully submitted, this the lLday of December, 1981.

Raleigh, I'Iorth Carolina 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377

Norma Harrell

Tiare Smi1e17

Assistant A.ttorneys General

John Lassiter

Associate Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

Jerris Leonard &

900 17th Street,

Suite 1020

Washington, D. C.

(202) 872-L095

Associates, P.C.

N.I\7.

20005

.Ta

P.UFUS L.

ATTORNEY

EDI,IISTEN

GE}]ERAL

aIIaCe, tJf .

Attorney Gene

Legal Affairs

rney Generalrs Office

. C. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629