Thomas v. County of Los Angeles Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

November 13, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thomas v. County of Los Angeles Brief for Appellees, 1991. e1697ff8-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f8d5d5ba-4ac6-4b16-b97e-83f93965eda5/thomas-v-county-of-los-angeles-brief-for-appellees. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Copied!

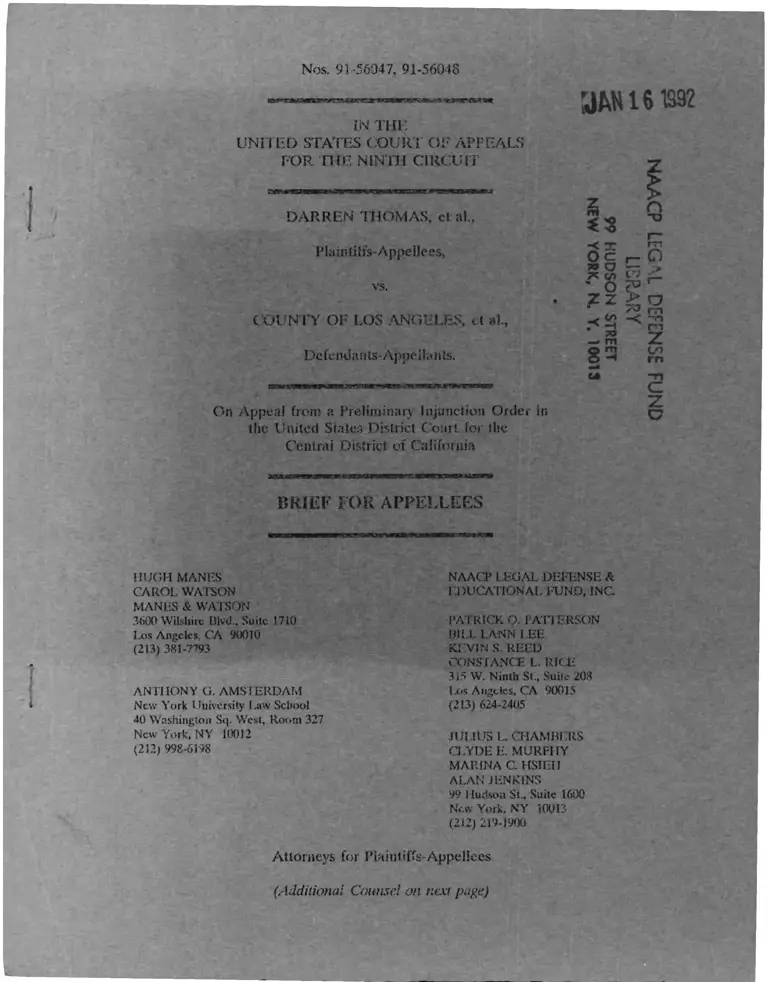

Nos. 91-56047, 91-56048

y AN 1 6 1S92

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

DARREN THOMAS, et al.,

Plain tiifs-Appellees,

vs.

COUNTY- OF LOS ANGELES, et a!.,

L>c fe n dan Is- Appellants.

On Appeal from a Preliminary Injunction Order in

the United States District Court for the

Central District of California

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

HUGH MANES

CAROL WATSON

MANES & WATSON

3600 Wilsliire Bivd.. Suite 1710

Los Angeles, CA 90010

(213) 381-7793

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University Law School

40 Washington Sq. West, Room 327

New York, NY 10012

( 212) 998-6198

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

PATRICK O. PAT1ERSON

BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

CONSTANCE L. RICE

3i5 W. Ninth St., Suite 208

lx>s Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CLYDE E. MURPHY

MARINA C. HSIEII

ALAN JENKINS

99 Hudson St., Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

(Additional Counsel on next page)

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

LIBRARY

99 HUDSON STREET

NEW

YORK, N. Y. 10013

Additional Plaintiffs-Appellees’ Counsel:

JOHN C. BURTON

JAMES S. MULLER

BURTON & NORRIS

301 North Lake Street, 8th Floor

Pasadena, CA 91101

(818) 449-8300

GARY S. CASSELMAN

11340 West Olympic Blvd., Suite 250

Los Angeles, CA 90064

(310) 478-8388

SCOTT CRAIG

CRAIG & GOLDSTEIN

10866 Wilshire Blvd., 15th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90024

(310) 441-4111

RICHARD EIDEN

2110 South Hill St., Suite O

Oceanside, CA 92054

(619) 967-9101

JAMES FOSTER

4929 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 915

Los Angeles, CA 90010

(213) 936-2110

ART GOLDBERG

SANDOR FUCHS

GOLDBERG & FUCHS

1467 Echo Park Ave.

Los Angeles, CA 90020

(213) 250-5500

ROBERT MANN

DONALD COOK

MANN & COOK

3600 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1710

Los Angeles, CA 90010

(213) 252-9444

TED YAMAMOTO

1200 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 206

Los Angeles, CA 90017

(213) 482-2248

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Nos. 91-56047, 91-56048

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

DARREN THOMAS, et al„

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from a Preliminary Injunction Order in

the United States District Court for the

Central District of California

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

HUGH MANES

CAROL WATSON

MANES & WATSON

3600 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1710

Los Angeles, CA 90010

(213) 381-7793

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University Law School

40 Washington Sq. West, Room 327

New York, NY 10012.

(212) 998-6198 ,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

CONSTANCE L. RICE

315 W. Ninth St., Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CLYDE E. MURPHY

MARINA C. HSIEH

ALAN JENKINS

99 Hudson St., Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW ........................................................................................... 3

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION.............................................................................................. 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE....................................................................................................... 3

A. Nature of the C a se ......................................................................................................... 3

B. Proceedings Below ......................................................................................................... 4

C. Attorneys' Fees ...................................................................................................................................... 9

D. Statement of Facts ......................................................................................................... 9

1. Introduction......................................................................................................... 9

2. The Pattern of Constitutional Violations by Lynwood Deputies ................ 10

a. Beatings ................................................................................................ 13

b. Use of Firearms To Terrorize, Maim, and K ill............................... 18

c. Abusive Searches................................................................................ 20

3. Racially Motivated Harassment........................................................................ 23

a. Racial Slurs, Intimidation and Ridicule . . ........................................ 23

b. The Vikings .......................................................................................... 24

c. Policy of Targeting Gangs for "Special Attention"............................... 26

4. Retaliation......................................................................................................... 30

5. Cover C harges.................................................................................................. 32

6. Discouragement of Complaints........................................................................ 33

7. Department-Wide Assignment Policies .......................................................... 35

8. Tacit Authorization of Unconstitutional Conduct........................................... 35

ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................................... 39

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER GRANTING A PRELIMINARY

INJUNCTION IS SUBJECT TO REVIEW ONLY FOR ABUSE OF

l

39

41

42

45

46

49

50

51

52

55

55

55

58

60

60

DISCRETION

NO LEGAL RULE INVOKED BY DEFENDANTS REMOTELY

REQUIRES REVERSAL ON THIS RECORD.............................................

A. RIZZO DOES NOT BAR THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

ISSUED BELOW..................................................................................

B. LYO N S INTERPOSES NO OBSTACLE TO THE

INJUNCTION........................................................................................

C. THE INJUNCTION DOES NOT TRESPASS ON ANY

PRINCIPLE OF FEDERALISM.........................................................

D. ANDERSON V. CREIGHTON DOES NOT REVERSE THE

BALANCE OF EQUITIES THAT TIPS IN FAVOR OF

ISSUANCE OF THE INJUNCTION..................................................

THE DISTRICT COURTS FINDINGS OF FACT ARE FULLY

SUPPORTED BY THE RECORD..................................................................

THE DISTRICT COURTS APPLICATION OF THE LAW TO THE

FACTS DID NOT RESULT IN AN ABUSE OF DISCRETION.................

A. THE COURT FOLLOWED THE CORRECT PROCEDURES IN

ISSUING THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION...............................

B. THE SCOPE OF THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION IS

PROPER................................................................................................

1. The Court Did Not Order Any Classwide Relief. ................

2. The Court’s Order Is Narrowly Tailored To Minimize

Federal Intrusion And Is Limited To The Scope Of The

Probable Constitutional Violations Established By The

Record........................................................................................

3. The Geographic Scope Of The Order Derives From

Defendants’ Representations To The Court Below................

C. THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER COMPLIES WITH THE

FORMAL REQUIREMENTS OF RULE 65(d), FED. R. CIV. P. .

1. The District Court's Oral And Written Findings Of Fact And

Conclusions Of Law Set Forth The Reasons For Issuance Of

The Preliminary Injunction.......................................................

2. The District Court’s Order Is Sufficiently Specific In Its

ii

Terms, And It Describes In Reasonable Detail The Acts

Sought To Be Restrained.......................................................

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases . page

Allee v. Medrano, 416 U.S. 802 (1971) ................................................................................ passim

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985) ............................................... 7, 44, 45

Anderson v. Creighton, 483 U.S. 635 (1987) .............................................................................. 43

Aoude v. Mobil Oil Corp.. 862 F.2d 890 (1st Cir. 1988)............................................................ 48

Bennett v. City of Slidell, 728 F.2d 762 (5th Cir. 984) ............................................................... 41

Bethlehem Mines Corp. v. United Mine Workers of America,

476 F.2d 860 (3d Cir. 1973) ........................................................................................... 47

Bracco v. Lackner, 462 F. Supp. 436 (N.D. Cal. 1978) .............................................................. 46

Caribbean Marine Services Co. v. Baldrige,

844 F.2d 668 (9th Cir. 1988) ........................................................................................... 49

Chemlawn Services Corp. v. GNC Pumps, Inc.,

823 F.2d 515 (Fed. Cir. 1987)......................................................................................... 48

City of Canton v. Harris, 103 L.Ed. 2d 412 (1989)..................................................................... 41

City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95 (1983).................................................................passim

Clark v. County of Los Angeles, CV 91-3689 TJH (GHKx) ...................................................... 4

Combs v. Ryan s Coal Co., 785 F.2d 970 (11th Cir. 1986),

cert, denied, 479 U.S. 853 (1986) ..................................................................................... 55

Davis v. City and County of San Francisco, 890 F.2d 1438 (9th Cir.

1989), cert, denied sub nom. San Francisco Firefighters Local 798

v. City and County of San Francisco, 111 S.Ct. 248 (1990) .......................................... 54

Eng v. Smith, 849 F.2d 80 (2d Cir. 1988)..................................................................................... 43

Flynt Distributing Co. v. Harvey, 734 F.2d 1389 (9th Cir. 1984)............................................... 46

Fuller v. County of Los Angeles, No. CV 90-1601 (C.D. Cal.) ................................................. 3

Gibbs v. Buck, 307 U.S. 66 (1938)................................................................................................ 48

IV

Giles v. Ackerman, 746 F.2d 614 (9th Cir. 1984) ................................................... ................... 41

Gonzales v. City of Peoria, 722 F.2d 468 (9th Cir. 1983) .......................................................... 42

Griggs v. Provident Consumer Discount Co., 459 U.S. 56 (1982) ............................................. 48

Harris v. City of Pagedale, 821 F.2d 499 (8th Cir. 1987)............................................................ 41

Henry Hope X-Ray Products, Inc. v. Marron Carrel, Inc.,

674 F.2d 1336 (9th Cir. 1982) ......................................................................................... 54

Hoffritz v. United States, 240 F.2d 109 (9th Cir. 1956)............................................................... 46

Hvbritech Inc. v. Abbott Laboratories,

849 F.2d 1446 (Fed. Cir. 1988)......................................................................................... 48

ICC v. Rio Grande Growers Co-op, 564 F.2d 848 (9th Cir. 1977)............................................. 53

International Longshoremen’s Association v. Philadelphia

Marine Trade Association, 389 U.S. 64 (1967) ............................................................... 57

Johnson v. Radford, 449 F.2d 115 (5th Cir. 1971) ............................................................... 51, 58

LaDuke v. Nelson, 762 F.2d 1318 (9th Cir. 1985)....................................................................... 40

Lawrence v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 274 U.S. 588 (1927).......................................... 55

Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission v. National

Football League, 634 F.2d 1197 (9th Cir. 1980) ...................................................... 43, 49

Lynch v. Baxley, 744 F.2d 1452 (11th Cir. 1984).......................................................................... 43

Masalosalo v. Stonewall Ins. Co., 718 F.2d 955 (9th Cir. 1983) . . .-.......................................... 48

Matter of Thorpe, 655 F.2d 997 (9th Cir. 1981)..........................................................................48

McLaughlin v. County of Riverside, 888 F.2d 1276 (9th Cir. 1988)........................................... 43

Missouri v. Jenkins, 109 L.Ed.2d 31 (1990) ................................................................................ 44

Monell v. Department of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658 (1978) ................................................. 41

Nelson v. IBEW Local 46, 899 F.2d 1557 (9th Cir. 1990)................................................... 40, 58

Nicacio v. INS, 797 F.2d 700 (9th Cir. 1985) .............................................................................. 40

NLRB v. Express Publishing Co., 312 U.S. 426 (1941).............................................................. 58

v

NORML.v. Mullen. 608 F. Supp. 945 (N.D. Cal. 1985);

affd in part, mod. in part, 796 F.2d 276 (1991) .......................................................................... 43

Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halderman,

465 U.S. 89 (1984)............................................................................................................. 52

Perfect Fit Industries v. Acme Quilting Co., 646 F.2d 800

(2d Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 832 (1982)............................................................ 56

Professional Assn, of College Educators v. El Paso Community

College District, 730 F.2d 258 (5th Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

~ 469 U.S. 881 (1984)........................................................................................................... 54

Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U.S. 522 (1984) ......................................................................................... 44

Regal Knitwear v. NLRB, 324 U.S. 9 (1945) .............................................................................. 53

Republic of the Philippines v. Marcos, 862 F.2d 1355

(9th Cir. 1988), cert, denied 490 U.S. 1035 (1989)................................................... 36, 46

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976).....................................................................................passim

Ross-Whitney Corp. v. Smith, Kline & French

Laboratories, 207 F.2d 190 (9th Cir. 1953)............................................................... 35, 55

Samples v. City of Atlanta, 846 F.2d 1328 (11th Cir. 1988)............. : ........................................ 41

Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61 (1974)....................................................................................... 55

San Francisco-Oakland Newspaper Guild v. Kennedy,

412 F.2d 541 (9th Cir. 1969) ........................................................................................... 46

Schmidt v. Lessard, 414 U.S. 473 (1974) ..................................................................................... 55

Smith v. City of Fontana, 818 F.2d 1411 (9th Cir. 1987)............................................................ 41

Supreme Court of Virginia v. Consumers Union. 446 U.S. 719 (1980) .................................... 44

Tribal Village of Akutan v. Hodel, 859 F.2d 662 (9th Cir. 1988)............................................... 44

United States v. Crookshanks, 441 F. Supp. 268 (D. Ore. 1977)............................................... 53

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364 (1948)............................................. 45

Vision Sports, Inc. v. Melville Corp.,

888 F.2d 609 (9th Cir. 1989) ........................................................................................... 36

vi

White v. Washington Public Power Supply System,

669 F.2d 1286 (9th Cir. 1982) ......................................................................................... 55

Zepeda v. INS, 753 F.2d 719 (9th Cir. 1983)....................................................................... passim

Statutes and Rules page

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ............................................................................................................................... 8

Cir. Rule 28-2.3 ................................................................................................................................. 8

Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. P ............................................................................................................... 3, 4

Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. P .................................................................................................... passim

Rule 65(d), Fed. R. Civ. P .................................................................................................... passim

Others page

7 Moore’s Federal Practice H 65.12 (2d ed. 1991)....................................................................... 47

9 Moore’s Federal Practice 11 203.11, p. 3-48 (2d ed. 1991)........................................................47

C. Wright & A. Miller, 11 Federal Practice and

Procedure § 2949, pp. 469-473 ............. 46

ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether the district court properly exercised its discretion in granting a preliminary

injunction requiring the Los Angeles County Sheriffs Department to follow its own stated policies

and guidelines governing searches and use of force pending a trial on the merits, where:

a. The record established a persistent pattern of constitutional violations:

b. The court applied the correct legal standards;

c. The court's findings of fact are clearly supported by the record; and

d. The court carefully weighed the relevant factors and issued an injunction in the proper

form.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

Appellees accept the appellants' statements of jurisdiction.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Nature of the Case

This appeal arises from an action under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1983 and 1985 challenging a pattern

of pervasive misconduct by sheriff s deputies assigned to the Lynwood station of the Los Angeles

County Sheriffs Department ("LASD"). Defendants have appealed from the district court’s grant

of a preliminary injunction requiring that, pending final determination of the action, LASD

employees shall (1) follow the LASD's own stated policies and guidelines regarding the use of force

and procedures for conducting searches, and (2) submit to the Court, in camera and under seal,

copies of reports alleging the use of excessive force. ER 1888-89.1

'This brief uses the following abbreviations: "ER" refers to Appellants' Joint Excerpts of

Record; "Supp. ER" refers to Appellees' Supplemental Excerpts of Record; "CR" refers to docket

entries in the Clerk's Record; "Cty. Br." refers to the opening brief tiled on behalf of Appellants

County of Los Angeles. City of Lynwood. Los Angeles County Sheriffs Department. Sheriff

Sherman Block. Undersheriff Robert Edmonds, Assistant Sheriffs Jerry Harper and Richard

Foreman, and Captain Bert J. Cueva; "Dep. Br." refers to the opening brief filed on behalf of 21

individual deputy Appellants; "LASD Manual" refers to the Los Angeles County Sheriffs

Department Manual of Policy and Procedures.

1

B. Proceedings Below

On September 26. 1990. 75 victims of police misconduct (the "Thomas plaintiffs")2 filed this

suit as a class action, alleging systematic lawlessness and wanton abuse of power by sheriffs

deputies assigned to the LASD station in Lynwood, a city whose population of 62.000 is 24 percent

African-American and 70 percent Latino.3 The complaint (ER 1-53) alleged 42 separate incidents -

- all occurring within the span of 104 days between February 10 and May 25, 1990 — of what the

district court characterized as "systematic and unjustified shootings, killings, beatings, terrorism, and

destruction of property caused by Los Angeles County deputy sheriffs at the Lynwood sub-station."4

ER 1957-58. The complaint named as defendants the County of Los Angeles, the LASD. the City

of Lynwood. Los Angeles County Sheriff Sherman Block, the Undersheriff and two Assistant

Sheriffs, the Commander of the Lynwood station (Captain Bert J. Cueva), 21 individual LASD

deputies, and 500 doe defendants.5 ER 4-5. Because the defendants had not taken sufficient

action to correct abuses uncovered by prior individual damage suits,6 the Thomas plaintiffs sought

to litigate their damage claims jointly and requested declaratory and injunctive relief on behalf of

2Six additional named plaintiffs appear solely as guardians ad litem on behalf of minor children.

ER 1-3.

3United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Summary Population &

Housing Characteristics (1990), California p. 67. According to the 1980 census, the population of

Lynwood was approximately 55,000, of whom 34 percent were African-American and 43 percent

were Latino. ER 15. The 1980 per capita taxable income for residents of Lynwood was $6,222,

compared to a Los Angeles County per capita taxable income of $11,842. Id.

4One additional incident occurred on October 18. 1989. ER 98 (Demetrio Carrillo).

'The complaint also named as defendants the California Attorney General and the Los Angeles

Countv District Attorney. The district court later dismissed all claims against both of these officials.

CR 63, 137.

6Los Angeles County paid approximately $8.5 million in settlements and jury awards in

individual excessive force lawsuits against LASD in 1986-1989, and the number of such lawsuits has

steadily mounted in the last five years. Supp. ER 23. Sheriff Sherman Block has testified that his

department does not keep records of lawsuits filed against deputies, nor does it keep records of

judgments entered in such suits against deputies or against the department. ER 158-59.

2

a class pursuant to Rule 23. Fed. R. Civ. P.

The district judge who ultimately issued the preliminary injunction in Thomas, Hon. Terry

J. Hatter. Jr., at first declined even to consider the Thomas plaintiffs’ claims. In July and August

1990. the plaintiff in a separate action pending before Judge Hatter, Fuller v. County of Los Angeles,

No. CV 90-1601 (C.D. Cal.), had moved for leave to file an amended complaint, to join additional

parties, and to associate additional counsel in his case. Appellees' Request for Judicial Notice on

Appeal, p. 4. In essence, these motions sought to amend the complaint in Fuller - a § 1983 case

alleging police misconduct by Lynwood deputies — to state all of the claims later pleaded in

Thomas. The district court denied this motion, expressing concern about the effect that the

proposed amendment might have on the rights of the individual deputy defendants in Fuller.

Appellees’ Request for Judicial Notice on Appeal, pp. 13-14.

The Thomas complaint was filed together with a "notice of related case" advising the court

of the Thomas plaintiffs’ position that their case and Fuller were related. See ER 1963 (CR 2).

The Thomas case was initially assigned to Hon. A. Wallace Tashima. Thereafter, in accordance

with the district court's local rules. Judge Tashima determined that the Thomas case was properly

transferable and, with Judge Hatter's consent, ordered that it be transferred to Judge Hatter's

calendar. See ER 1963 (CR 25).3

In November and December. 1990, defendants County of Los Angeles. City of Lynwood.

LASD, Sherman Block, and Bert J. Cueva filed numerous motions, including motions to dismiss

part or all of the complaint on various grounds: to stay all discovery and other proceedings in the

action on various grounds; to stay all discovery relating to class certification and to dismiss the class * *

As the district court noted, a motion to certify the case as a class action had not been filed at

the time the court issued its preliminary injunction. ER 1958. On October 28. 1991. plaintiffs filed

such a motion, which is currently pending in the district court. Supp. ER 230 (CR 162).

sContrary to the assertion in the individual deputy defendants’ brief in this Court, plaintiffs did

not file their notice of related case "(ujpon learning that the instant case had been assigned to

Judge Tashima." Dep. Br., p. 10. The record shows that plaintiffs filed the complaint and notice

of related case at the same time. See ER 1963 (CR 1, 2).

3

allegations of the complaint: and to sever plaintiffs' claims of entity and supervisorial liability from

their claims against individual deputies. CR 28-30. 34-35. On January 2, 1991, the California

Attorney General moved to dismiss all claims against him. CR 37. These motions were fully

briefed, and the district court took them under submission in January 1991. See CR 36.

Anticipating that the district court’s disposition of these motions would significantly affect the

course of future proceedings, the parties stipulated to, and the Court ordered, a stay of further

discovery pending a ruling on the motions. CR 36. 54-55.

On July 19, 1991, the district court granted the Attorney General's motion to dismiss the

claims against him but denied the defendants’ other motions.9 Supp. ER 220 (CR 63). Meanwhile,

plaintiffs' counsel had learned that the pattern of misconduct and abuse by Lynwood deputies was

continuing. On July 9, 1991, 35 additional plaintiffs (the "Clark plaintiffs") filed a complaint

alleging further unlawful acts by Lynwood deputies. Clark v. County of Los Angeles, CV 91-3689

TJH (GHKx) (see Appellees’ Request for Judicial Notice on Appeal, p. 23). On July 15, 1991, the

Thomas plaintiffs filed their motion for a preliminary injunction, seeking protection against specific

forms of misconduct during the pendency of the lawsuit. Supp. ER 200.

In support of their preliminary injunction motion, plaintiffs filed over 200 pages of

documentary evidence, including 58 declarations detailing the deputies' misconduct and 33 color

photographs10 of injuries and property damage suffered by the victims. ER 54-260. Plaintiffs also

relied on documents they had previously filed in opposition to defendants’ pending motions,

including certified copies of the declarations of 11 deputies and news reports concerning the

existence and activities of the "Vikings," a white-supremacist gang of deputies operating within the

Lynwood substation. Supp. ER 48-199. Defendants responded with more than 1,200 pages of

9On August 21, 1991, the Los Angeles County District Attorney moved to dismiss the claims

against him. CR 77, 78. The court granted this motion on September 24, 1991. CR 137.

10In their Excerpts of Record, defendants supplied the Court with indecipherable black and

white copies of most of these photographs, and they omitted one altogether. Plaintiffs have

provided the Court with accurate color photocopies to be substituted for the unintelligible copies

filed by defendants.

4

declarations and other documents in an effort to refute plaintiffs’ claims. ER 352-780, CR 73-76.

In reply, plaintiffs filed 25 additional declarations and other documents. ER 875-904, 1395-1577.

Plaintiffs, but not defendants, requested an opportunity to present oral testimony on the motion.

See ER 1967 (CR 79); see also Plaintiffs' Reply Memorandum in Support of Motion for Preliminary

Injunction, p. 3 (CR 116).

On September 9, 1991, the district court heard the arguments of counsel, asked counsel for

all parties to review LASD’s stated policies and guidelines, and directed counsel to report to the

Court regarding the extent to which those policies and guidelines covered the misconduct alleged

in plaintiffs’ motion. ER 1921-22. Counsel for the parties subsequently conferred and submitted

a joint statement to the court which set forth each specific item of relief sought by plaintiffs in

conjunction with the language of each LASD policy and guideline the parties agreed was relevant.

ER 1741-58. The parties also filed separate statements supplementing their joint report. ER 1607-

1740, 1759-1887. Plaintiffs’ separate submission included a modified proposed order which, in

language taken from LASD’s stated policies and guidelines, specifically set forth the temporary

relief requested with respect to search procedures, use of force, racial slurs, photographs of injured

persons, and reports to the court. ER 1593.

On September 23, 1991, after hearing further argument and after reading and considering

the thousands of pages of declarations, memoranda, reports, and other documents submitted by the

parties, the district judge stated that he did not "relish getting involved in a situation where the

court is asked to indeed supervise ongoing law enforcement activities," but that he could not

"overlook the evidence that’s been presented so far." ER 1949. Faced with credible evidence of

a pattern of widespread constitutional violations by LASD deputies in Lynwood, the district court

made oral findings that serious issues had been raised and that the balance of hardships clearly fell

on the side of the plaintiffs, and stated that it was therefore his intention to grant provisional relief

in the form of "a very simple order." Id. By requiring the defendants to follow their own policies

and guidelines regarding the use of force and the conduct of searches until such time as the factual

5

record could be more fully developed at trial, the order would provide the plaintiffs with a measure

of temporary protection from further violations of their constitutional rights while minimizing the

degree of federal intrusion into the operation of a local law enforcement agency and also

safeguarding the rights of individual deputies. See ER 1948-55.

After the hearing, the district court signed an order requiring that, pending final

determination of the action, all employees of LASD, whether sworn or civilian, shall: (1) "Follow

the Department’s own stated policies and guidelines regarding the use of force and procedures for

conducting searches"; and (2) "Submit to the Court, in camera and under seal, copies of reports

alleging the use of excessive force that are in the possession of the Department on the first of every

month."11 ER 1889.

The district court stayed its order until 5:00 p.m. the following day, September 24, 1991, in

order to permit defendants to seek emergency appellate relief. ER 1889. Defendants then sought

and obtained orders of this Court granting a stay pending appeal and expediting the appeal. Orders

of Sept. 24 and Oct. 1, 1991.

On October 8, 1991, the district court filed written findings of fact and conclusions of law

which supplemented its previous oral findings. ER 1957-61. The Court concluded that plaintiffs

had established their probable success on the merits and the likelihood of irreparable injury, and

that issuance of the preliminary injunction "will serve the public interest in that it will prevent, or

at least minimize the physical, emotional, and psychological harm being suffered by plaintiffs and

the Lynwood community at the hands of Lynwood area deputies." ER 1960. Defendants

subsequently requested and obtained an extension of time in order to address the district court's

written findings and conclusions in their briefs in this Court. Order of Oct. 16. 1991.

uAt the district judge’s direction, plaintiffs’ counsel submitted a proposed order after the

hearing. The judge struck out language in the proposed order that would have limited its

application to "the jurisdiction of the Lynwood station of this Department," and he also struck out

language requiring that copies of departmental reports alleging the use of excessive force be served

on plaintiffs’ counsel, subject to an appropriate protective order. ER 1889.

6 •

C. Attorneys’ Fees

To the extent they are prevailing parties, plaintiffs intend to seek attorneys’ fees for this

appeal pursuant to 42 LLS.C. § 1988. See Cir. Rule 28-2.3.

D. Statement of Facts

1. Introduction

The district court’s findings of fact frame the issues for consideration on this appeal unless

they are "clearly erroneous" under Rule 52(a). Fed. R. Civ. P.12 In the present case, the district

court made its findings in the context of ruling on a motion for a preliminary injunction. Such

findings — made on the basis of a necessarily incomplete factual record, under properly relaxed

evidentiary standards, and in support of temporary relief to deal with an emergency situation -- are

subject only to the most limited appellate review.13 Here, each of the district court’s findings of

fact is supported by ample evidence in the record.

2. The Pattern of Constitutional Violations by Lynwood Deputies

The district court found that, "[a]s a result of the terrorist-type tactics of deputies working

in Lynwood, and policy makers' tolerance of such tactics, plaintiffs are being irreparably injured --

both physically and mentally — and their civil rights are being violated." ER 1959. Plaintiffs’

complaint set forth at least 130 abusive acts committed by Lynwood deputies — almost exclusively

against African-Americans and Latinos — within the first few months of 1990. These acts included

at least 69 warrantless, harassing arrests and detentions; 31 incidents of excessive force and

unwarranted physical abuse against handcuffed and otherwise defenseless detainees (beating,

kicking, pushing, striking with flashlights, choking, slamming doors on legs, slapping, shooting to

12Rule 52(a) requires a court of appeals to respect a district court's factual findings even though

the appellate court might have weighed the evidence differently. Where there are two permissible

views of the evidence, the district court's choice between them cannot be clearly erroneous.

Anderson v. City o f Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564, 573-74 (1985).

13In such a case, the appellate court is "foreclosed from fully reviewing the important questions

presented. Review of an order granting or denying a preliminary injunction is much more limited

than review of an order granting or denying a permanent injunction." Zepeda v. INS, 753 F.2d 719,

724 (9th Cir. 1983).

7

maim); seven ransackings of homes and businesses; 16 incidents of outright torture (interrogation

with stun guns, beating victims into unconsciousness, holding a gun in a victim’s mouth and pulling

the trigger on an empty chamber, pushing a victim's head through a squad car window); quick-stop

driving to bang a victim’s head against the squad car screen; and uninhibited expressions of racial

animus by deputies, including use of epithets such as "niggers" and "wetbacks." ER 16-38.

The declarations submitted in support of plaintiffs' motion for a preliminary injunction

provided sworn statements supporting the allegations of the complaint. These declarations — which

the district court found "more credible than [the evidence] presented by the defendants" (ER 1959)

- also demonstrated that the pattern of gross misconduct by Lynwood deputies did not end with

the filing of plaintiffs’ complaint in September 1990, but continued to subject plaintiffs to

irreparable injury and continued to deprive plaintiffs of their civil' rights.14 ER 1959. In addition

to documenting 14 of the specific incidents described in the complaint, plaintiffs' declarations

attested to 28 further and strikingly similar incidents. The original complaint names 21 individual

deputies as defendants,15 and the declarations filed by the parties identity an additional 45 deputies

by name as being involved in such incidents.16 This total of 66 specifically identified deputies -

14In the Excerpts of Record they filed in this Court, defendants inserted the portion of their

memorandum of points and authorities below in which they argued their version of the facts set

forth in plaintiffs' declarations. ER 781-812. However, defendants did not include in their Excerpts

of Record any portions of the memoranda filed by plaintiffs in the court below. In accordance with

Circuit Rules 30-1.3 ("excerpts of record shall not include briefs or other memoranda of law filed

in the district court" unless they have independent relevance) and 30-2 (sanctions for "inclusion of

unnecessary material in excerpts of record"), plaintiffs have not included any such memoranda in

their Supplemental Excerpts of Record. Plaintiffs, however, wish to refer the Court to the detailed

statements of the facts set forth in their memoranda below. See CR 62, pp. 3-46; CR 116, pp. 13-

44.

15The complaint names as defendants deputies Rosas. Mato. Delgadillo. Garcia. Courgin. Mann.

Nordskog, Raimo. Gillies. Kiff. Brown-Vover. Boge, Mossotti. Smith. Campbell. Thompson. Pippen.

Leslie. Sheehy, and Archamba'ult.

16The declarations (ER 54-260, 352-780, 1395-1577) identity the following additional deputies

(victims of the misconduct are indicated in parentheses): Cormier (Darren Thomas), Pinesett

(Darren Thomas), Ripley (Darren Thomas, Tracy Batts). Wilkerson (Tracy Batts), Wallace (William

Leonard), Sgt. Yarborough (Jose Ortega), Pacina (the Maya family), Goran (the Rodriguez family,

the Villegas family), Orosco (the Calderon family), Benson (Richard Hernandez), Running (Richard

Hernandez), Brownell (Richard Hernandez, Alan Brahier, Thomas Monreal), Brannigan (the

8

which does not take into account the numerous deputies whom plaintiffs have named as doe

defendants but have not yet been able to identify — constitutes more than 50 percent of all deputies

assigned to the Lynwood station.17

Defendants in their briefs seek to create the impression that most if not all of the plaintiffs

and declarants subjected to abuse by Lynwood deputies are dangerous criminals.18 This assertion,

even if true, would hardly justify condoning a massive pattern of police misconduct, abusive

searches, excessive force, and physical brutality. In fact, defendants' assertion is not true. The

record shows that the great majority of the plaintiffs and declarants who were beaten and otherwise

abused by deputies have not been convicted of any criminal activity in connection with those

incidents, and that most were not even arrested during their encounters with the deputies. The

figures are as follows:19 60 plaintiffs and declarants were not'arrested;20 4 were arrested but not

Melendrez family), Schneider (Ron Dalton. Marcello Gonzales), Reeves (Ron Dalton, Marcello

Gonzales), Sgt. Coleman (Ron Dalton, Marcello Gonzales), Lt. Jackson (Ron Dalton, Marcello

Gonzales), Owen (Elzie Coleman), Costleigh (Jeremiah Randle, Cesar Guerrero), Goss (Jeremiah

Randle), Alvarado (Jeremiah Randle), Steinwand (Leopoldo Ortega), Enos (Alan Brahier), O’Hara

(Gregory Mason), Sennett (Gregory Mason), Frazier (the Villegas family), Jonsen (the Villegas

family), Roche’ (the Brown family), McCarthy (the Charles family), Anderson (Thomas Monreal),

Corina (Thomas Monreal), Caldwell (Thomas Monreal), Santana (Enrique Bugarin), Wilber (Larry

Clarke, Stanley Jones, Kelvin Davis), Archer (Kelvin Davis), Rossman (Cesar Guerrero), Dunn

(Jose Luis Hernandez), Saucedo (Richard Cruz), Luna (Lloyd Polk funeral, Ernesto Avila, Jesse

Melendrez), Chapman (Carlos Maya), Santee (Steven Thomas), Payne (Henry Castro), Sgt. Holmes

(Lloyd Polk funeral), Sgt. Golden (Demetrio Carrillo), Lt. Rudelaff (Demetrio Carrillo).

17The record indicates that there are 125 deputies at the Lynwood station, and that 85 of those

deputies are assigned to patrol duties. Supp. ER 50. See also ER 1484 (approximately 85 deputies

assigned to the Lynwood station). Without citing any reference in the record, the County

defendants have claimed in their brief on appeal that the Lynwood station has "approximately 140

sworn officers" and/or "140 patrol officers." Cty. Br.. p. 36 n.24. Using defendants' unsubstantiated

figure, the 66 deputies whom plaintiffs have identified by name constitute 47 percent of all deputies

assigned to Lynwood.

lsThe County defendants assert, for example, that "[tjhose arrested were prosecuted, usually

successfully. Of the named plaintiffs who were arrested, virtually all have been convicted or are

currently being prosecuted. ..." Cty. Br., p. 31 n.16. See also, e.g., id. at 11. 27 n.14, 42; Dep. Br..

p. 41.

19The record does not reveal the status or disposition of any charges against 12 persons: Larry

Clarke, Richard Cruz, Kelvin Davis, Raul Gonzalez, Bernardo Guzman, Stanley Jones, Fernando

Martinez, Gregory Mason, Jesse Melendrez, Raphael Ochoa, Salvador Preciado, and Teresa

Rodriguez.

9

charged with any crime;20 21 12 were charged but later had the charges dismissed by the District

Attorney or by a court;22 2 were tried and acquitted;23 9 still have pending cases;24 and only 7

pleaded guilty or were convicted of a criminal offense, of whom only 2 were convicted of crimes

involving violence.25

20Adolpho Alejade (ER 30), Brian Alejade (ER 30), James Brown (ER 21), Jose Bugarin (ER

85), Antonio Caballero (ER 30), Carolina Calderon (ER 90), Christiana Calderon (ER 90), Jorge

Calderon (ER 90), Linda Calderon (ER 90), Mary Charles (ER 107), Marianne English (ER 36),

Jeffrey Holliman (ER 142), Candi Leonard (ER 92), Sandi Leonard (ER 92), Yidefonza Lorenzana

(ER 33), Antonio Guzman (ER 134), Jose Luis Hernandez (ER 136), Alfredo Maya (ER 168),

George Maya (ER 168), Gilbert Maya (ER 168), Irene Maya (ER 168), Lupe Maya (ER 168),

Marguerita Maya (ER 168), Raul Maya (ER 168), Raul Maya, Jr. (ER 168), Ruben Maya (ER

168), Lilia Melendrez (ER 170), Natalie Mendez (ER 175), Georgia Mendibles (ER 181), Estella

Montoya (ER 31), Rebecca Montoya (ER 31), Alice Orejel (ER 192), Maria Orejel (ER 192), Delia

Osita (ER 130), Frances Palacila (ER 90), Rudy Perez (ER 170), Jeremiah Randle (ER 199),

Estella Rojas (ER 33), Aurelo Salazar (ER 208), Marta Sanchez (ER 33), Charles Scott (ER 226),

Anthony Sorto (ER 90), Elsa Tovar (ER 237), Herman Tovar (ER 237), Jaime Tovar (ER 237),

Jesus Tovar (ER 237), Marcelo Tovar (ER 237), Francisco Tovar, Sr. (ER 237), Francisco Tovar,

Jr. (ER 237), Yesenia Tovar (ER 237), Crystal Trevino (ER 31), Monique Trevino (ER 31), Brenda

Villegas (ER 246), Demesio Villegas (ER 246), Jose Villegas (ER 246), Maria Villegas (ER 246),

Ramona Fuamatu Villegas (ER 246), Herman Walker (ER 254), Alvin Washington ER 256), and

Danny Williams (ER 1570).

21 Aaron Breitigam (ER 28), Calvin Charles (ER 104), Cesar Guerrero (ER 131), and Thomas

Monreal (ER 183).

"Ernesto Avila (ER 1483, CR 27), Enrique Bugarin (ER 84), Henry Castro (ER 102-03), Kevin

Marshall (ER 702), Carlos Maya (ER 1536), Lloyd Polk (ER 151, 1506-15), William Scott (ER

702), Darren Thomas (ER 778), and Steven Thomas (ER 622).

:3Demetrio Carrillo (ER 101) and Elzie Coleman (Appellees' Request for Judicial Notice on

Appeal, p. 16).

24Tracy Batts (ER 609-10), Ron Dalton (ER 121-23. 1540-41), Marcelo Gonzales (ER 1541),

Eric Jones (ER 1541), Jose Ortega (ER 683-87), Alfonso Sanchez (Appellees' Request for Judicial

Notice on Appeal, pp. 17-20). Alfredo Sanehez (id.), Jose Sanchez (id.), and Sergio Sanchez (id.).

The Compton Municipal Court recently granted a motion to hold an evidentiary hearing into

alleged juror misconduct at the trial of the Sanchez brothers. Id.

25Jesus Avila (receiving stolen property) (ER 512-18); Alan Brahier (assault) (ER 597); Ruben

Calderon (taking vehicle for temporary use) (CR 48); Sergio Galindo (receiving stolen property)

(ER 519-22); Richard Hernandez (evading a police officer) (ER 614-18); Leopoldo Ortega (charged

with attempted murder; docket provided by defendants illegible regarding nature of conviction) (ER

543-45); and Michael Sterling (drinking in public) (ER 702).

10

a. Beatings

The record before the district court established a pervasive practice of unjustified beatings

by Lynwood deputies. The beatings, frequently accompanied by racial slurs and taunts (see

Statement of Facts, Section 3, infra), often included blows to the head and other vital parts of the

body with impact weapons.26 Plaintiffs’ declarations document 22 such incidents.

The case of plaintiffs Darren Thomas, Kevin Marshall, William Scott, and Michael Sterling

illustrates the pattern of unjustified beatings by Lynwood deputies. At about 11:30 p.m. on April

25, 1990, Darren Thomas was standing in a private yard in Lynwood, socializing with some African-

American and Latino relatives and friends after a funeral. As they talked and drank beer, two

LASD patrol cars drove up; one deputy flashed a light on the men in the yard and ordered them

to come out into the street, while two other deputies entered the yard and began pushing and

shoving, ordering the men to "get out of the goddamn yard." Once they were out on the street, they

were ordered to put their hands on the hot hood of one of the patrol cars.27 ER 228-29.

The men asked, "What’s the problem? What did we do wrong?," but the deputies ignored

their questions. Then a deputy repeatedly hit Mr. Thomas's cousin, Kevin Marshall, in the back

of the head while telling him to be quiet. Another deputy handcuffed Thomas tightly and ordered

him to go to the patrol car, repeatedly shoving and jerking him around while he attempted to

comply. The deputy also threw Thomas to the ground, causing his glasses to fall off and the frames

to crack. ER 229.

26The declarations include accounts of beatings on the head with clubs, flashlights, saps, and

other objects (Sergio Sanchez, ER 220; Alfonso Sanchez, Supp. ER 217; Jose Sanchez, ER 216;

Richard Hernandez, ER 140; Ron Dalton. ER 121; Alan Brahier, ER 73; Larry Clarke. ER 115;

Stanley Jones, ER 147; Steven Thomas. ER 235); slamming heads into curbs, a brick wall, a trailer,

and a car (Sergio Sanchez, ER 220; Alfredo Sanchez. ER 212; Calvin Charles, ER 104; Alan

Brahier, ER»73; Jose Luis Hernandez. ER 136); and kicking in the face and eyes (Leopoldo Ortega,

ER 196; Gregory Mason, ER 165). See also Complaint H 35. ER 25 (Lloyd Polk's head beaten with

billy clubs); If 38, ER 26 (Fernando Martinez's head shoved through patrol car window); 11 54. ER

31-32 (Ruben Calderon choked with flashlight).

27The record shows that it is a common practice for Lynwood deputies to force persons to place

their unprotected faces and hands against the hot hoods of patrol cars. See ER 99 (Demetrio

Carrillo); ER 229 (Darren Thomas); ER 137 (Jose Luis Hernandez); ER 120 (Richard Cruz).

11

Mr. Thomas, his unde, William Scott, and two cousins, Kevin Marshall and Michael Sterling,

were all arrested and driven to the Lynwood station. Despite repeated requests, they were not told

why they had been arrested. A deputy drove the patrol car recklessly on the way to the station,

making wild turns and slamming on the brakes so that the three handcuffed men in the back seat

would bang their heads against the metal screen separating the front seat from the back.28 ER

229.

When they arrived at the Lynwood station, the men were taken to the back room of an

"OSS" ("Operation Safe Streets," or "gang") trailer, where the deputies told them they had "fucked

up" and that the deputies would "kick [y]our ass" if they didn't shut up and quit asking so many

questions. As a deputy began to book him, Thomas asked what he was being charged with, and why

his rights had not been read to him. The deputy became angry, put the handcuffs back on Thomas,

and said, "Lve had enough of this shit." ER 229-30.

After another deputy entered, hitting his hand with his flashlight in a menacing manner, the

first deputy put Thomas in a carotid chokehold and choked him unconscious. The next thing

Thomas remembers is being hit with a jolt of electricity from a taser gun. He was on his knees,

handcuffed, and repeatedly hit and kicked while he was subjected to racial slurs. One of the

deputies said, "Yeah nigger, you ain't got no rights. We are going to make sure you don’t ask any

more questions." Thomas looked down and saw his blood and broken teeth on the floor of the

trailer. ER 230.

Thomas was again put in a chokehold and choked into unconsciousness, and he was again

shot with the taser gun. He then found himself flat on the floor, face down. As a deputy picked

him up by the neck, he heard someone say, "That's enough." He also heard Scott and Sterling

yelling, "What are you doing to him?" In response, a deputy grabbed Scott, pointed a shotgun in

Sterling's face, and told them to be quiet or they would be next. Scott and Sterling were then taken

28This is known as a "screen test" in the jargon of the deputies. See also ER 27 (Complaint 1111

39-40, Fernando Martinez).

12

out of the room, and Thomas was taken to the hospital after being threatened again with the taser

gun. His lip required stitches, his two front teeth were knocked out, and he was in severe pain.

ER 230-31.

Thomas was falsely charged with attempted assault on an officer (dismissed before trial),

drinking in public (dismissed during trial because there is no Lynwood ordinance prohibiting

drinking on private property), and resisting, delaying, and obstructing an officer (dismissed after the

jury was unable to reach a verdict). ER 231. As the district court found, several other plaintiffs

were also charged with crimes pursuant to an unwritten policy of charging persons injured by

deputies. ER 1958. See Statement of Facts, Section 5, infra.

Examples of the many other unjustified beatings by Lynwood deputies that are documented

by the record are the following:

• Deputies arrested Lloyd Polk, kicked him and repeatedly beat him with billy clubs,

breaking both his arms and inflicting other serious injuries. See ER 151, 154-57; ER 25. A

Municipal Court judge later dismissed charges that Polk had assaulted a police officer, finding that

there was "abundant evidence that the officer was using excessive force" and that "the conduct on

the part of these officers was outrageous." ER 1510, 1513. Almost ten months after the beating,

Jason Mann (one of the deputies who beat Polk) signed a declaration stating that he had never

been under investigation for the use of excessive force. Supp. ER 142.

• After Demetrio Carrillo criticized deputies for driving over a sidewalk and almost

hitting him with their patrol car in a school driveway, the deputies handcuffed Carrillo and severely

beat .him in a secluded area behind the Lynwood Civic Center while calling him "mother-fucker"

and "God-damn Mexican." ER 98-100.

• Deputies struck Jose Louie Ortega across the back and ribs with a flashlight,

denied him medical attention, and arrested him for resisting or obstructing an officer. ER 194-95.

• Deputies handcuffed Richard Hernandez, dragged him through gravel and broken

glass, and beat him with batons and flashlights while calling him "son of a bitch" and "asshole." ER

13

140-41.

• Deputies beat Ron Dalton with fists and batons. A month later, they picked him

up again, kicked him repeatedly and beat him with fists, batons, and flashlights. They then hogtied

him and kicked and beat him some more. ER 121-23.

• Deputies kicked Calvin Charles in the testicles, spread his arms and fingers back,

dragged him across asphalt by the handcuffs, shoved his head into the side of the "gang" trailer at

the Lynwood station, and punched him in the face and stomach. ER 104-106.

• Deputies dragged Alan Brahier out of his car, threw him to the pavement, hit him

on the head and body with flashlights, punched him in the eye. dragged him face down on the

pavement, slammed his head into a brick wall, and hogtied him and beat him with flashlights. ER

73-75.

• Deputies handcuffed Leopoldo Ortega and then beat, kicked, and struck him with

a flashlight or baton. A deputy also tried to break his fingers. Deputies then took him to the OSS

trailer at the Lynwood station, where he was subjected to further kicking and beating about the

face, arms, and legs. Later, at the County Jail, a large number of deputies beat him severely after

they learned that he had been charged with the attempted murder of Lynwood deputies. After this

beating, he was strapped to a bed in the hospital ward for two days. ER 196-98.

• Deputies punched Thomas Monreal in the eye. beat him in the back of a patrol

car, and slapped him at the OSS trailer at the Lynwood station. ER 184-86. Several deputies also

repeatedly beat and kicked Cesar Guerrero, who was handcuffed, at the OSS trailer. ER 131-32.

186.

• Deputies slammed Jose Luis Hernandez's face onto the hot hood of a patrol car.

grabbed him by the neck and threw him down, bent back his arm and thumb, threw him into the

patrol car, slammed the door shut on his leg, and threatened to shoot him. ER 136-38.

Deputies handcuffed Larry Clarke and Stanley Jones, and then proceeded to kick

them in the groin, lift them off the ground by their handcuffs, and beat them repeatedly with saps.

14

ER 115-16. The deputies also held guns to their heads and pulled their triggers on empty

chambers. ER 115. 147. During the beatings. Clarke told a deputy three times that Jones was an

epileptic. ER 116.

• A deputy handcuffed Richard Cruz and then hit him on the hip with a club,

saying, "I can hit you in places where there won't be any bruises." ER 119. The deputy later used

his car to force Cruz off the bicycle he was riding, and then made Cruz put his hands on the hood

of the car and punched him in the eye. ER 120.

• Deputies kicked Aurelo Salazar with their boots, repeatedly beat him with their

fists, and squashed his hand with a boot as if putting out a cigarette, breaking his thumb. One of

the deputies, who had falsely arrested Salazar before, said, "Remember me from court?" The

deputies then laughed at him and left him lying on the sidewalk as they drove away. ER 208.

• Deputies handcuffed and hog-tied Gregory Mason at the Lynwood station and

kicked him in the eye, face, and arm while calling him "asshole" and "stupid-ass nigger." ER 166.

• After they observed him driving his new BMW, deputies handcuffed and

repeatedly kicked Jeremiah Randle — a black Los Angeles school teacher — in the knee while

calling him "nigger" and heaping other verbal abuse on him. ER 201. They also severely twisted

his fingers and wrists. Id.

b. Use of Firearms To Terrorize, Maim, and Kill

The record shows that Lynwood deputies have repeatedly used their firearms to terrorize

members of the public. They routinely enter homes and other premises with their weapons drawn

and give armed orders to men. women, and young children without regard to whether their captives

pose any threat to deputies or others. See, e.g., ER 108 (deputy cocked gun and pointed it. without

provocation, at Mary Charles' 13-year-oJd son); ER 85 (when Enrique Bugarin asked if he had a

search warrant, deputy grabbed his gun and said, "This is my search warrant"); ER 80 (when told

that he was violating James Brown's constitutional rights by illegally searching his home, deputy

responded by telling Brown to shut up and putting his gun closer to Brown's face); ER 142-43

15

(while Jeffrey Holliman lay on the ground in response to deputies’ commands, deputy shoved the

muzzle of his shotgun into Holliman's neck and threatened to kill him).

Lynwood deputies also frequently use their firearms to terrorize people during beatings.

See, e.g., ER 230-31 (when William Scott and Michael Sterling protested the beating of Darren

Thomas, deputy grabbed Scott by the neck, pointed a shotgun in Sterling’s face, and told them to

be quiet or they would be next); ER 122 (during beatings, one deputy put a gun to Marcello

Gonzales' head, and another deputy put a gun in Ron Dalton's mouth and threatened to blow his

head off if he moved or tried to run); ER 115, 147 (during beatings, a deputy put a gun in Larry

Clarke’s right ear and pulled the trigger on an empty chamber, and another deputy twice placed the

barrel of his gun behind Stanley Jones’ head and pulled the trigger on an empty chamber).

The record further demonstrates that Lynwood deputies misuse their firearms to kill or

maim unarmed persons. See ER 149-50 (8 to 12 deputies surrounded, shot, and killed William

Leonard without justification); ER 63 (after deputies shot and wounded Tracy Batts in the leg,

deputy directed a Compton police officer to unleash his attack dog on Batts); ER 117 (deputy fired

at Elzie Coleman 23 times without justification, hitting him in the leg, thumb, torso, arm, and

testicles); ER 125-26 (after yelling to his partner to "[mjove so I can shoot his black ass," deputy

shot Kelvin Davis in the buttocks, causing him to lose one kidney and part of his intestines; as

Davis lay wounded on the ground, the other deputy kicked him in his side and face, saying, "You

shouldn’t have been running anyway, nigger").29

c. Abusive Searches

The record contains evidence of two searches of a business and ten searches of homes in

which Lynwood deputies stormed in during the early morning hours without giving notice of their

identity or time for the occupants to answer the door; they destroyed property; they threw property

Z9See also Supp. ER 31-45 (October 1990 newspaper study reporting that deputies shot at least

56 people under "seriously questioned circumstances" between 1985 and 1990); ER 1573, 903

(deputies shot and killed an unarmed African-American man in August 1991 and placed an object

near or under his body); ER 901-02 (deputies shot and killed an unarmed Latino man in August

1991).

16

on the floor or from room to room; they terrorized the occupants by brandishing weapons; they

forced whole families to stand or kneel, nearly naked, in the cold night air for long periods of time;

they confiscated property not identified in search warrants; they shoved or needlessly moved the

frail and ill; and they left people terrified and suffering psychologically and physically from the

experience.

The January 24, 1991, raid on the Villegas family's home is illustrative. At 5:30 a.m., Jose

and Maria Villegas and their adult children and young grandchildren were awakened by someone

breaking down the door to their Lynwood home. ER 243, 248, 250. Members of the Latino family

initially thought the intruders, who did not identify themselves, were gang members (ER 250) or

robbers. ER 252. It later became apparent, however, that they were Lynwood deputies. At

gunpoint, the deputies ordered the adults to go outside in their underwear or nightgowns, where

they were forced to stay in the cold night air for a long period of time while deputies searched the

house and photographed the two Villegas brothers holding name cards. ER 243-44, 246, 250.

Cynthia Villegas pleaded with the deputies to be careful with her 68-year-old father, Jose,

because he had diabetes and a heart condition and could not see much without his glasses. ER 243,

253. His wife, Maria, also told them that her husband was sick. ER 250. Nevertheless, the

deputies repeatedly pushed Mr. Villegas and, after hearing his wife’s and daughter's pleas, said they

did not care and again pushed him, almost knocking him to the ground. ER 243, 253. Additionally,

for a long period of time during the raid, deputies refused to let 58-year-old Maria Villegas go to

the bathroom. When they finally let her go, she was humiliated as three male deputies watched her

use the toilet. ER 251.

After Brenda Villegas was ordered outside at gunpoint, she told the deputies that her three

young children (ages 6, 5, and 2) were asleep in the house and that they would be frightened. After

a while, she was allowed to go as far as the living room to call for them; but when they appeared,

deputies pointed guns at them, refused their mother's request to get clothes for herself and her

children, and ordered all of them to go outside. Her 6-year-old daughter. Perla, became feverish

17

as they stood out in the cold, and she vomited and was sick the next day. Perla and her 5-year-old

sister, Christina, in particular, have experienced emotional distress since the raid. ER 244.

Despite repeated requests, Ramona Fuamatu Villegas also was not allowed to go back inside

to get her 5-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. After a deputy eventually went into Elizabeth’s room,

the child came out crying and freezing because she was without shoes or a jacket. Since the raid,

Elizabeth has been afraid that deputies will return and that everyone in the family will be arrested,

and she has had nightmares about someone shooting her. ER 252-53.

Although the deputies caused physical damage to the Villegas home and psychological harm

to the members of the family, their search revealed no guns or illegal items, and no one was

arrested. ER 244-45, 246-47, 248, 253.

The record contains evidence of many other abusive searches conducted by Lynwood

deputies, including the following:

• On February 15, 1990, deputies raided the J & A Towing and Repair shop, an

African-American-owned business, terrorizing customers and employees and needlessly destroying

property. ER 142-45, 226-27, 256-57. In September 1990, deputies returned to the shop, searched

it without a warrant, and threatened retaliation if the owners did not drop this lawsuit. ER 145-46.

• In the predawn hours of March 1, 1990, deputies raided several Latino families’

homes at gunpoint. They failed to give reasonable notice and an opportunity to open the door;

they needlessly destroyed property; they mistreated small children and elderly persons; and they

forced people to stay outdoors for long periods in night clothes or underwear. ER 88-90, 96-97,

168-69, 181-82, 192-93, 237-42.

• In another early morning raid, deputies broke down the gate in front of Thomas

Monreal’s house. They forced him to stand outside in his underwear while they searched the house,

causing damage and disarray. One of the deputies punched him in the eye while he was

handcuffed. ER 184-85.

• Deputies conducted two warrantless searches of the Bugarin home, during which

18

they intimidated the people there and unnecessarily destroyed property. ER 82-87.

• In an early morning raid of the Mendez family’s home, deputies failed to give

reasonable notice and an opportunity to open the door, needlessly destroyed property, and

mistreated small children and a pregnant woman. ER 170-77.

• Deputies raided an African-American family's home at gunpoint, pulling down the

support pole on the front porch and crashing through the front door without announcing who they

were. When James Brown stated to one of the deputies that they were violating his constitutional

rights, the deputy told Brown to "shut up" and put his gun closer to Brown's face. ER 80.

• Deputies raided another African-American family's home three times in nine

months. They held family members at gunpoint (including Maiy Charles’ 15-month-old

granddaughter), ransacked the children’s rooms, and needlessly destroyed property. ER 107-110.

3. Racially Motivated Harassment

a. Racial Slurs, Intimidation and Ridicule

The district court found that "[t]he actions of many deputies working in the Lynwood sub

station are motivated by racial hostility ...." ER 1958. This finding is amply supported by the

record, which shows that racial slurs — "nigger," "goddam Mexican," "stupid-ass fucking nigger,"

"mother-fucking Mexican," and the like — frequently accompany beatings and other abuse

administered by Lynwood deputies. The record contains the following examples, among others, of

such racial slurs:

• When Jeremiah Randle, a 28-year-old black school teacher, asked why he had

been stopped, a deputy replied, "Look, nigger, I don't have to tell you shit." Deputies then told

him, "Your black ass is going to jail," and "Yeah, nigger is going to jail, and going to jail tonight."

While the deputies then kicked him repeatedly as he screamed out in pain, the deputies called him

"nigger," "pussy," "bitch," and "cry-baby." After the beating was over, another deputy told him.

"We're not racist; we think everyone should own a nigger." ER 200-201.

• When Larry Clarke asked why a deputy had pulled Clarke up off the ground by

19

the handcuffs and had then put his gun in Clarke’s ear and pulled the trigger on an empty chamber,

the deputy told him, "Shut the fuck up,” and then called him a "stupid black guy" while beating him

on the head and back with a sap. Clarke lost consciousness twice during the beating. ER 115-16.

• While beating Demetrio Carrillo, deputies called him a "mother-fucker" and a

"God-damn Mexican." ER 100.

• Deputies called Gregory Mason a "stupid-ass nigger" while beating and kicking him

at the Lynwood station. Mason was then taken to St. Francis Hospital, where he asked that medical

treatment be delayed until someone had called his wife and asked her to come to the hospital.

When a deputy learned that Mason’s wife was on the way. Mason was handcuffed and taken back

to the station, where a lieutenant called him a "stupid-ass fucking nigger," accused him of "trying

to be smart," and told him that they were going to "lose [him] in the system." ER 166-67.

• Deputies said, "nigger, you ain't got no rights" and subjected Darren Thomas to

other racial slurs while beating and kicking him at the Lynwood station. ER 230.

• Deputies called Alfredo Sanchez a "mother-fucking Mexican" and yelled other

offensive remarks about "Mexicans" while beating and kicking the Sanchez brothers into

unconsciousness. ER 213, Supp. ER 217.

• Deputies called Calvin Charles a "nigger" and kicked him in the testicles, and then

told him, "We are going to take you home to your Mammy." ER 105.

• Aiming at Kelvin Davis, a deputy yelled to his partner, "Move so I can shoot his

black ass," and then shot Davis in the buttocks. As Davis lay wounded on the ground, the other

deputy said, "You shouldn't have been running anyway, nigger," and then kicked him in his side and

in his face. Davis lost one kidney and part of his intestines from the gunshot wound, and he had

to wear a colostomy bag for five months. ER 125-26.

The district court also found that "many of the deputies and sergeants in Lynwood were out

to intimidate and ridicule Blacks and Hispanics." ER 1959. In addition to the evidence outlined

above, this finding is supported by evidence that Lynwood deputies regularly forced black residents

20

to posture themselves as gorillas to pass the "A.P.E. Test"; posted on the Lynwood substation

employee bulletin board and maintained for an extended period of time a map of Lynwood shaped

as Africa; and distributed to black residents advertisements for "Nigger Pills" and "Coon-ard Line

Boat Tickets to Africa." ER 1400-1402.

b. The Vikings

The district court found that "[m]any of the incidents which brought about this motion

involved a group of Lynwood area deputies who are members of a neo-nazi. white supremacist gang

— the Vikings - which exists with the knowledge of departmental policy makers." ER 1958.

Plaintiffs filed with the Court certified copies of the declarations of 11 LASD deputies concerning

the existence of a white-supremacist gang of Lynwood deputies known as the "Vikings." Supp. ER

59-199. These declarations show that, for more than a year, Sheriffs Department personnel within

the Lynwood station were aware of allegations of racially motivated, anti-black, white-supremacist,

hate crime activities by Lynwood deputies affiliated with the Vikings (Supp. ER 164-99

[Declarations of Danielle Cormier, Dan Figueroa, Lance Fralick, Doug Gillies, Kevin Kiff, Jerold

Reeves, and Jay Ritter, H 3]); that knowledge of these allegations was widespread throughout the

Sheriffs Department (id.., 11 6); and that on numerous occasions starting as early as April 1990, the

commander of the Lynwood station stated that deputies affiliated with the Vikings were linked to

criminal activities and were associated with "raping and pillaging" minority members of the

community (id., U 4; Supp. ER 153 [Declaration of Clifford Yates, U 6]).

Also before the Court was a lengthy investigative report on the Vikings, which found that

"[a] sizeable group of deputies in the Lynwood Sheriffs Station has taken on characteristics of a

street gang, and their harassing activities within the department have led their commander [Captain

Cueva] to label them a ’malignancy’ that must be dealt with quickly." Supp. ER 48. However, the

record indicates that the only action ever taken with regard to the Vikings did not occur until

several months after this lawsuit was filed, and it consisted merely of transferring four deputies from

21

Lynwood to other locations.30 Supp. ER 59-199.

c. Policy of Targeting Gangs for "Special Attention"

The Court’s findings with regard to racially motivated harassment and intimidation are

further buttressed by evidence that an official policy of targeting certain gangs in the Lynwood area

for "special attention" (ER 129) has resulted in racially motivated harassment. In accordance with

provisions of the LASD Manual (CR 130),31 the Commander of the Lynwood station has told his

deputies to target members of some 30 gangs and to arrest them for any kind of conduct that could

be construed as a violation of any statute or municipal ordinance. ER 129. Operation Safe Streets

("OSS") deputies are assigned to the Lynwood station to specialize in targeting suspected gang

members and in suppressing gangs. ER 762.

The record contains substantial evidence demonstrating the racial harassment associated

with this gang-targeting policy:

• When Herman Walker, a 23-year-old African-American, tried to calm a group of

younger men who were upset because someone they knew had been shot, Lynwood deputies picked

him up and held him in the back of a patrol car for approximately three hours. Instead of thanking

him for his assistance, Lynwood deputies asked him what gang he belonged to, and told him that

30Although plaintiffs have not yet had an opportunity to conduct thorough discovery, the record

at present shows that at least deputies Jason Mann, Michael Schneider, and Brian Steinwand are

members of the Vikings. Deputies Mann and Schneider were transferred from the Lynwood station

in December 1990 because the station's commander, Captain Cueva, suspected them of being

Vikings. Supp. ER 56-199. Deputy Steinwand’s mark of membership is in the form of a Viking

tatoo on his outer left ankle, with his moniker "Steiny" above it and the initials "LVS" below it. ER

1410. Deputy Mann inflicted savage beatings on Lloyd Polk (ER 151) and Alan Brahier (ER 73-

75), and he reportedly shot and killed Arturo Jimenez, who was unarmed. See ER 902. Deputy

Schneider was involved in the incident in which Ron Dalton was beaten. See ER 706. Deputy

Steinwand was involved in the Leopoldo Ortega incident (ER 546) and in the framing of Tracy

Batts (ER 1410).

31LASD Manual § 2-06\050.10 describes the "Safe Streets Bureau," which is comprised of two

Details: the "Gang Enforcement Team" and the "Operation Safe Streets Detail (OSS)." CR 130.

The responsibilities of the OSS Detail include "[targeting particularly violent or active street gangs

within assigned OSS team areas," "[participating in street gang suppression efforts within assigned

OSS team areas," and "[investigating all cases, otherwise routinely assigned to Station Detectives

that involve ’target’ street gang members." Id.

22

they knew he must be a gang member because he was black. ER 254-55.

• To investigate a robbery of four bicycles during which a victim was wounded by

shots from a handgun, deputies used a form search warrant to search eight different homes of

suspected Latino gang members for a wide variety of items, including all "evidence of gang

membership to include items of personal property with gang graffiti on them, doodles, writings,

plaques, phone books that tend to show membership in the ‘Young Crowd’ gang, also any clothing

to include, but not limited to, jackets, hats, sweatshirts, and common everyday objects [on] which

gang graffiti has been placed." ER 420-22. The "Statement of Probable Cause" in support of the

warrant application includes several pages of form allegations setting forth sweeping statements

about the behavior of supposed gang members in general (ER 424-30), with only limited reference

to the specific facts of the incident purportedly under investigation. See ER 426. Deputies used

a similar form search warrant in another investigation to search seven different homes of suspected

Latino gang members. ER 638-46.

• In the court below, deputies assigned to the Gang Enforcement Team at the

Lynwood station claimed that they initially approached Darren Thomas because he and others were

drinking in front of his house and were therefore "prime targets for gang drive-by shootings." ER

688-89, 693, 695. According to each of the deputies’ declarations, "it was dark enough so we could

not even tell what nationality or the specific characteristics of any of the individuals who were

standing around [sic]." ER 688, 693, 695. The deputies acknowledged that, "simply to get them off

the street and avoid their being our next victims, a decision was made to cite them for drinking in

public. This involves taking the individuals to the station where they are cited and released within

a few hours." ER 689, 694, 696. Deputies proceeded to subject Thomas to racial slurs and to

administer a severe beating in which they knocked out his two front teeth. ER 228-34.

• The "OSS" or "gang" trailer at the Lynwood station is a common site for beatings.

Darren Thomas (ER 229-30), Calvin Charles (ER 105), Leopoldo Ortega (ER 196-97), Thomas

Monreal (ER 186), and Cesar Guerrero (ER 131) were all beaten there.

23

Additionally, the record shows that deputies have subjected individuals suspected of gang

connections to recurring instances of abuse, including the following:

«

• Lloyd Polk, claimed by deputies to be a member of a gang (ER 752), alleged three

separate incidents of deputy misconduct on February 11, April 15, and April 22, 1990, including a

severe beating in which both his arms were broken. ER 25-26, 151, 154-57. Deputies later