NAACP v. Thompson Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 29, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Thompson Brief of Appellees, 1965. d333111c-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f95f0359-16d2-4ba6-b75f-d6b133c86d34/naacp-v-thompson-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

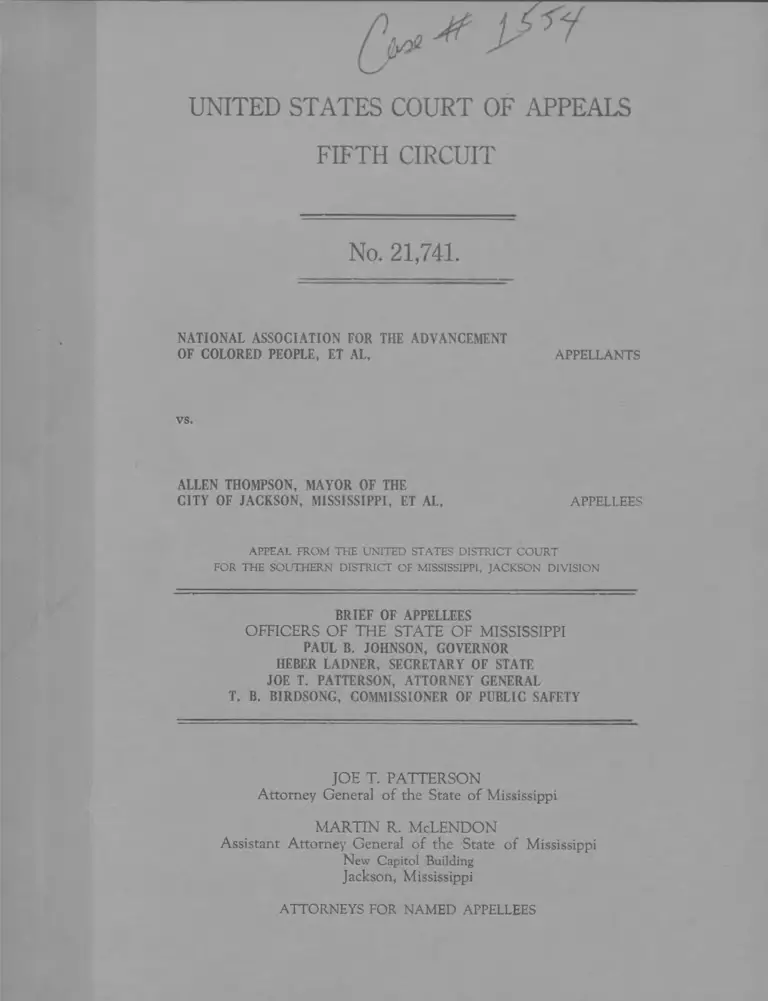

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 21,741.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL, APPELLANTS

VS.

ALLEN THOMPSON, MAYOR OF THE

CITY OF JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI, ET AL, APPELLEES

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI, JACKSON DIVISION

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

O F F IC E R S O F T H E S T A T E O F M ISSISSIPPI

PAUL B. JOHNSON, GOVERNOR

IIEBER LADNER, SECRETARY OF STATE

JOE T. PATTERSON, ATTORNEY GENERAL

T. B. BIRDSONG, COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC SAFETY

JO E T . P A T T E R S O N

A ttorn ey G eneral o f the State o f M ississippi

M A R T IN R . M cL E N D O N

Assistant A ttorn ey G eneral o f the State o f M ississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, M ississippi

ATTORNEYS FOR NAMED APPELLEES

I N D E X

SUBJECT INDEX: Page

BRIEF CF APPELLEES IQ fficers of State of M ississippi]:

PREFACE 1

STATEMENT CF THE CASE 1

1. Preliminary Statement 1

2. Procedural Background 2

3. Statement of Facts 4

4. Question Presented 8

INTRCDUCTICN TC ARGUMENT 8

ARGUMENT 10

PRCPCSITICN I: THE CCURT IS WITHCUT JURISDICTICN

CF THE PARTIES, THESE APPELLEES 10

PRCPCSITICN n: THE CCURT IS WITHCU^ JURISDICTICN

CF THE SUBJECT MATTER AND CF THE CLAIM

AGAINST THESE APPELLEES FCR THE REA SCN

THAT THE CCRPCRATE APPELLANT IS NCT A

CITIZEN ENTITLED TC "PRIVILEGES AND IM

MUNITIES" 13

PRCPCSITICN III: FCREIGN CCRPCRATICNS SEEKING

PERMISSICN TC DC BUSINESS IN ANCTHER STATE

MUST CCMPLY WITH THE LAWS CF THE CTHER

STATE 17

PRCPCSITICN IV: THE DISTRICT CCURT DID NCT

ABUSE ITS DISC RE TIC N IN DECLINING TC GRANT

THE RELIEF PRAYED FCR AND, UNDER ESTAB

LISHED RULES CF LAW AND EQUITY, THIS

CCURT SHCULD DECLINE TC CRDER THE ISSU

ANCE CF A PERMANENT MANDATORY INJUNCTICN

AGAINST THESE APPELLEES CN THE RECCRD

PRESENTED 20

APPELLANT'S CASES DISTINGUISHED 22

CCNCLUSICN 24

CERTIFICATE CF SERVICE 25

TABLE CF CASES:

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, North Dakota, 326 U.S.

207, 90 L . ed. 6 16, 20

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31, 7 L .e d .2 d 512,

82 S. Ct. 549 15

ii.

INDEX (Cont'd):

TABLE CF CASES (Cont'd): Page

Bates v. City of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516,

4L .ed ,& 480 , 80 S.Ct. 412 23

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294,

8 L. ed. 510, 82S.C t. 1502 10

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organizations,

307 U.S. 496, 83 L. ed. 1423, 59 S.Ct. 954 14

Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Commerce

C orp ., 337 U.S. 682 11, 12

Louisiana, ex rel, Jack Gremillion v. N .A .A .C .P .,

e ta l, 366 U.S. 293, 6 L .ed .2d301 , 81S.C t. 1333 23

Malone v. Bowdoin, 369 U.S. 643, 8 L .ed . 2d 168,

82 S.Ct. 980 11, 12

Miguel v. McCarl, 291 U.S. 442, 54 S.Ct. 465, 78 L .ed . 902 19

N .A .A .C .P . v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449,

2 L .ed .2d 1488, 78 S.Ct. 1163 23

Crientlns. Co. v. Daggs, 19 S.Ct. 281, 282, 172

U.S. 557, 43 L .ed . 552 14

Panama Canal Co. v. Grace Line, Inc.,

356 U.S. 309, 78 S. Ct. 752, 2 L .ed . 2d 788 20

Parr v. United States, 351 U.S. 513, 76 S.Ct. 912,

100 L .ed . 1377 20

United States v. Greene County Board of Education,

332 F. 2d 40 21

Whitehouse v. Illinois Cent. R. C o.,

349 U.S. 366, 75 S.Ct. 845, 99 L .Ed. 1155 20

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

United States Constitution:

Eleventh Amendment 9, 10, 12, 13, 24

Fourteenth Amendment 8, 15, 23, 24

18 C. J. S. 413, Corporations, § 35(b) 19

Mississippi Code of 1942, Recompiled:

Section 4065. 3 5

Section 5310.1 17

Section 5339 18

Section 5340 10, 18, 19

Section 5341 18

28 U. S. C. 1652 20

Words & Phrases, Permanent Edition, Vol. 7, p. 261 14

Vol. 32, p. 351 15

[Emphasis in quoted matter herein is supplied].

1.

PREFACE

We do not agree entirely with corporate appellant's statement of

the case or facts. Although the facts, concerning the issues to which this

brief is addressed, are not in substantial dispute, corporate appellant

makes statements not supported by the record and relies entirely upon

allegations of its complaint, not supported by the proof, to support its

claim for relief here. We believe that time and convenience of the Court

and the interest of justice will be best served by our submitting the follow

ing statement of the case as we submit it is shown by the record herein.

STATEMENT CF THE CASE

1. Preliminary Statement.

In this case, appellants seek to obtain an order of this Court man-

datorily enjoining and directing these appellees to approve the application

of the corporate appellant for domestication of the foreign, New York,

non-profit corporation. Since none of the appellants introduced any evi

dence whatsoever of any act of these appellees that might even be construed

as tending to deprive any citizen of any federal constitutional right, this

brief is addressed to the lack of authority of the Court to issue the manda

tory injunction sought, the right of a state to refuse to permit foreign co r

porations to qualify to do business within its borders or place conditions

upon the permission so granted and the correctness of the District Court'

refusal to issue the mandatory order sought. Incidental to the above is

the absence of any right of the corporate appellant to affirmatively assert

constitutional rights of and for its members.

The undisputed proof shows that the policy of the State of M issis

sippi, of refusing to grant permission to any foreign non-profit corpora

tion to do business in Mississippi, is applied indiscriminately. The cor

porate appellant was treated no differently from any other foreign non

profit corporation similarly situated.

There is no evidence whatsoever of any citizen of Mississippi be

ing denied an opportunity to become a member of the corporate appellant.

No interference with membership was shown. In fact, the evidence shows

that the corporate appellant, through its officers and members, has been

very active in Mississippi for several years. The members of the corpon

ation have vigorously espoused their cause, and they have done so in the

name of the corporate appellant.

The District Court, Honorable Sidney C. Mize, heard the evidence

on the application for preliminary injunction on Count II and concluded that

the preliminary injunction should be denied. Cn the hearing on the merits

in the District Court, Honorable Harold Cox, no additional evidence sup

porting the allegations of Count H was offered. Both of the Judges of the

District concluded, as a matter of fact, that there was no discrimination

against the corporate appellant and, as a matter of law, that the manda

tory injunction against these appellees should not be granted.

The conclusions of the District Court are amply supported by the

record and prior judicial decisions.

2. Procedural Background

This action was filed by the corporate and individual appellants on

June 7, 1963. In Count I of the complaint, it was alleged that certain of

ficials of the City of Jackson, Hinds County, and the State of Mississippi

had violated constitutional rights of appellants and the prayer asked that

the alleged violations be enjoined. In Count II all allegations of Count I

were realleged; and in addition thereto, it was alleged that the corporate

appellant had sought to become domesticated as a Mississippi corporation;

and the prayer asked that the Court enjoin these appellees from refusing

to register the corporate appellant, i. e . , that they be mandatorily en

joined to approve the application for domestication of the corporate appel

lant, (T. 2-23).

Requests for admission were filed directed to the corporate appel

lant (T. 63-64) and to the individual appellants (T. 65-67). Although there

was a mixup in the requests, they were denied (T. 67-76), and the denials

became a part of the record (T. 131), in the light of the total lack of proof

to the contrary, the requests fairly state the case and the issues as to

these appellees.

The motion for a preliminary injunction on Count II was heard

(T. 312-369) on June 24, 1963. The motion was denied by the Court (T.

125-128), and the Court included in its opinion that the motion for a sever

ance of the two counts would be denied.

Answer of these appellees was filed (T. 76-85). The answer de

nied the charges, admitted that the application for domestication of the

foreign non-profit corporation had been denied and raised the questions

of the jurisdiction of the Court of the parties and of the subject matter.

Answer of appellee T. B. Birdsong was filed (T. 88-91). This

answer denied that this appellee was guilty of any wrongdoing. There was

no showing whatsoever that he had committed any of the acts charged

against him, either in the preliminary hearings or on the hearing on the

merits.

The case was tried on its merits by the Court without a jury on

February 4, 5, 6, 7, 27 and 28, 1964. Although counsel for the corporate

appellant stated (T..913) that they recognized a need to develop additional

evidence in light of the fact that the application for domestication had been

denied, no evidence was introduced at the hearing on the merits concern

ing the application for domestication or any showing that any of the appel

lants had been discriminated against by these appellees.

The opinion of the Court was rendered on June 1, 1964 and filed on

June 3, 1964 (T. 135-163). The final judgment dismissing the complaint

both as to Counts I and II was entered on June 5, 1964 (T. 164).

3. Statement of Facts

Contrary to the statement beginning on the bottom of page 17 of

appellant's brief, the record does not show that any notice or other com

munication was sent from the Secretary of State to the corporate appel

lant prior to the filing of the application for domestication. The ex parte

statement of the corporate appellant's counsel referred to above should

therefore be disregarded. It simply is not true.

The corporate appellant filed its application for domestication

with the Secretary of State and that application was denied by the Govern

or (T. 83-84) and returned to the president of the corporate appellant

(T. 84-85).

At the hearing before Judge Mize, the corporate appellant called

5.

appellee, Heber Ladner, who testified that the corporate records of his

office were handled by his deputy and that he did not know whether such

applications for domestication of foreign non-profit corporations were re

jected or approved (T. 321).

Appellee, Joe T. Patterson, was called as a witness. He testified

that the application of the corporate appellant for domestication had been

called to his attention and that it was handled by one of his assistants as

other such applications are handled. He read into the record (T. 326-327)

a letter written by his assistant, Martin R. McLendon, advising the Gov

ernor that the application did not comply with Mississippi statutes. He,

also, testified that, in his opinion, domestication of the corporate appel

lant would not be to the best interest of the State of M ississippi. He posi

tively denied that the provisions of Section 4065. 3, Mississippi Code of

1942, Recompiled, were a factor considered by him in arriving at his con

clusion that such domestication was not to the best interest of the State

(T. 338).

The Assistant Attorney General in charge of corporate matters

was called as a witness for and on behalf of plaintiffs (corporate appellant)

(T. 345). The testimony of that witness was positive and unequivocal that

no foreign non-profit corporations had received the recommendation, of

the witness or the office, to the Governor that its application for domesti

cation be approved (T. 346).

This witness also testified that this policy of excluding foreign non

profit corporations was based upon the fact that domestic non-profit co r

porations cannot be formed by persons other than adult resident citizens

of the State and that to permit a foreign corporation, organized by non

residents, to become domesticated would be permitting them to do indir

ectly what they were not permitted to do directly (T. 348), and he stated

that the Legislature deemed it best and proper that unincorporated asso

ciations taking on non-profit corporate structure, and thereby becoming

entitled to tax exemption and other advantages, should be reserved to

residents of the State.

The witness testified that his understanding of the law had been

applied indiscriminately and without regard to the identity of the applicant,

and that he had personal recollection of having handled both a Florida cor

poration and another New York corporation in the same manner.

The evidence for these appellees consisted of a certificate of the

Secretary of State, as custodian of the corporate records of the State of

Mississippi, and attached thereto were all of the record of his office deal

ing with the corporate appellant. These records consisted of copies of

the certificate of incorporation of the corporate appellant and various

amendments thereto supported by a certificate of the Secretary of State

of New York, a resolution designating a Mississippi agent and letter of

transmittal from appellant's counsel to the Secretary of State, letter of

transmittal from former Governor Barnett to the Secretary of State, and

letter of transmittal from the Secretary of State back to the corporation.

The certificate of incorporation of the corporate appellant shows

that the original incorporators certified and declared that they were " . . . .

of full age and two-thirds of us are citizens and residents of the United

States and residents of the State of New York, . . . "

Notwithstanding the fact that this testimony was taken in June,

1963, and the case was not heard on its merits until February, 1964,

neither the corporate appellant nor any of the individual appellants pro

duced any evidence at the hearing on the merits to contradict the evidence

taken at the time of the motion for preliminary injunction.

In fact, not one whit of evidence was introduced at the hearing on

the merits concerning any of these appellees concerning their handling

of the application for domestication.

Thus it is clear that appellants own evidence shows conclusively

and without dispute that all applications for domestication of foreign non

profit corporations have been regularly denied by the State of Mississippi.

Such denials are based on the theory that a corporation may not do indir

ectly that which it is prohibited from doing directly and thereby avoid the

requirements of Mississippi law that all incorporators of non-profit co r

porations be adult resident citizens of the State of Mississippi.

Thus it is clearly shown that the matter contained in the request

for admissions does fairly state the case and the issues as against these

appellees. The requests were that each of the following statements are

true:

(a) The facts alleged in Count I of the complaint are charged and

directed to defendants other than these and none of the allegations of

Count I are made against these defendants.

(b) The alleged failure of these defendants to completely process

the application for domestication of the foreign corporation, to-wit:

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a

__________________________________________________ 7.

New York corporation, is the sole ultimate fact charged against these de

fendants in Count II of the complaint.

Thus, it is readily apparent that the question before this Court

concerning these appellees is controlled by corporate and constitutional

law.

Question Presented

The issue presently before the Court and presented herewith is

whether this Court should order the issuance of a permanent mandatory

injunction ordering the State of Mississippi, acting through its duly consti

tuted officers, to-wit: its Governor, Attorney General and Secretary of

State, to approve the application for domestication of the foreign non

profit corporation, National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, a New York corporation. A preliminary to such a holding would

require that this Court hold that both Judges of the District Court abused

their discretion in declining to issue such an order.

INTFCDUCTICN TC ARGUMENT

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

has never been construed to vest "privileges and immunities" in corpora

tions. "Privileges and immunities" protected by that constitutional amenc

ment are limited to ". . . citizens of the United States, . . . " The ver}

nature of the "privileges and immunities" granted by the amendment are

such that an artificial legal entity, i . e . , a corporation, is incapable of

exercising or enjoying them. The "privileges and immunities" of citizen

ship can only be enjoyed by citizens. Corporations are not and cannot be

made citizens capable of exercising "privileges and immunities of citizen

s h ip /

In our affirmative argument, we will first show that jurisdiction

of this Court over these appellees, who acted for the State of Mississippi

in this matter, is prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

Secondly, we will show that the Court does not have jurisdiction of

the subject matter of the claim against these appellees for the reason that

a corporation is not a citizen entitled to "privileges and immunities, " and

the right of a state to exclude foreign corporations from doing business in

the State has been consistently upheld by the United States Supreme Court.

We will next show that, under the statutes of Mississippi, all in

corporators of non-profit, non-share corporations must be adult resident

citizens of the State of Mississippi, and no foreign non-profit, non-share

corporation can become domesticated unless it meets this requirement.

Finally, we will show that the Judges of the District Court did not

abuse their discretion, and this Court, in the exercise of sound judicial

discretion, should decline to issue a permanent mandatory injunction

against these appellees on the record presented.

Following the four points of our affirmative argument, we will dis

tinguish appellant's cases and show that none of the cases relied upon by

the appellants to support the claim for relief against these appellees dealt

with a problem analogous to the question presented herein by this record.

Thus, we will show this Court that the appellants should be denied

relief in this Court as was done in the District Court and the Judgment of

the District Court should be affirmed.

10.

ARGUMENT

PROPOSITION I

THE COURT IS WITHOUT JURISDICTION

OF THE PARTIES. THESE APPELLEES

Jurisdiction of the Court is fundamental and ". . . a review of

the sources of the Court's jurisdiction is a threshold inquiry appropriate

to the disposition of every case that comes before u s ." Brown Shoe Com

pany v. United States. 370 U.S. 294, 8 L .ed . 510, 82S.Ct. 1502.

The appellees, the Governor, the Attorney General and the Secre

tary of State of the State of Mississippi, in withholding the approval of

the application for domestication of the appellant corporation acted in ac

cordance with authority vested in them as such state officials and their

action therefore was state action. Section 5340, Mississippi Code of 1942

Recompiled, authorizes the Governor to take the advice of the Attorney

General and to approve, require* amendments prior to approval, ". . . o r

if deemed expedient by him he may withhold his approval entirely. "

The record shows without dispute that the application for domesti

cation has, in fact, been denied and the approval of the state withheld en

tirely.

There cannot then be any doubt that if the Court orders the issu

ance of the permanent mandatory injunction it will be exercising jurisdic

tion over one of the United States in a suit by citizens and persons of

another state.

Jurisdiction of the Court to grant such relief was removed by the

Eleventh Amendment, supra, which provides:

The Judicial power of the United States shall not

be construed to extend to any suit in law or equi

ty, commenced or prosecuted against one of the

United States by Citizens of another State, or by

Citizens or subjects of any Foreign State.

This amendment and the principle of sovereign immunity have

been the subject of considerable litigation in the Courts of the United

States.

In Malone v. Bowdoin, 369 U. S. 643, 8 L .ed . 2d 168, 82 S.Ct.

980, the Court said:

While it is possible to differentiate many of these

cases upon their individualized facts, it is fair to

say that to reconcile completely all the decisions

of the Court in this field prior to 1949 would be a

Procrustean task.

The Court's 1949 Larson decision makes it unne

cessary, however, to undertake that task here.

In Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Commerce C orp ., 337 U. S.

682, the Court announced the rules applicable to this case:

The question becomes difficult and the area of

controversy is entered when the suit is not one

for damages but for specific relief: i . e . , the re

covery of specific property or monies, ejectment

from land, or injunction either directing or re

straining the defendant officer 's action. In each

such case the question is directly posed as to

whether, by obtaining relief against the officer,

relief will not, in effect, be obtained against the

sovereign. For the sovereign can act only through

agents and, when an agent's actions are restrained,

the sovereign itself may, through him, be restrain

ed. As indicated, this question does not arise be

cause of any distinction between law and equity. It

arises whenever suit is brought against an officer

of the sovereign in which the relief sought from

him is not compensation for an alleged wrong but,

rather, the prevention or discontinuance, in rem,

of the wrong. In each such case the compulsion.

which the court is asked to impose, may be compul

sion against the sovereign, although nominally di-

12.

rected against the individual officer. If it is, then

the suit is barred, not because it is a suit against

an officer of the Government, but because it is. in

substance, a suit against the Government over which

the court, in the absence of consent, has no juris

diction.

* * *

In a suit against an agency of the sovereign, as in

any other suit, it is therefore necessary that the

plaintiff claim an invasion of his recognized legal

rights. If he does not do so, the suit must fail even

if he alleges that the agent acted beyond statutory

authority or unconstitutionally. But, in a suit against

an agency of the sovereign, it is not sufficient that he

make such a claim. Since the sovereign may not be

sued, it must also appear that the action to be re

strained or directed is not action of the sovereign.

The mere allegation that the officer, acting official

ly, wrongfully holds property to which the plaintiff

has title does not meet that requirement. True, it

establishes a wrong to the plaintiff. But it does not

establish that the officer, in committing that wrong,

is not exercising the powers delegated to him by the

sovereign. If he is exercising such powers the ac

tion is the sovereign's and a suit to enjoin it may

not be broucrht unless the sovereign has consented.

Even though the Court, in both Malone, supra, and Larson, supra,

vas dealing with sovereign immunity as it applies to agencies of the Feder

al Government, the principles announced are equally applicable to an action

against state officers because such action not only involves sovereign im -

munity but this Court is prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment, supra,

:rom exercising jurisdiction in such cases.

Since the relief sought is a permanent mandatory injunction direct-

3d against the State, it is clear that the rules quoted above prohibit the

granting of the relief sought.

The action of these appellees in this matter were acts of the State

af Mississippi. These appellees were only acting for the State in dealing

with the corporate appellant. If the Court, by ordering the issuance of

a permanent mandatory injunction, forces them to take the action request

ed, they will then be acting for the State. The State will be the party com -

pelled to act as effectively as though it were a party in name as well as

in fact.

The compulsion, which the Court is asked to impose, if imposed,

will be compulsion against the sovereign, although nominally directed

against the individual officers. It cannot be considered otherwise be

cause the present Governor, against whom the compulsion is sought, has

not even considered the matter.

The compulsion sought is clearly against the sovereign, which

has not consented to being so compelled, and is therefore barred by the

Eleventh Amendment, supra.

PBCPCSITICN II

THE CCUET IS WITHCUT XUBISDICTICN CF THE

SUBJECT MATTER AND CF THE CLAIM AGAINST

THESE APPELLEES FCB THE BEASCN THAT THE

CCBPCBATE APPELLANT IS NCT A CITIZEN

ENTITLED TC "PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES"

The claims of the individual appellants and the corporate appellant

are held together only by the astuteness of the pleader and brief-writer.

Notwithstanding the complete failure to connect, by proof, the al

legations of the two counts of the complaint, the individual appellants

seek to bolster the claim of the corporate appellant and the corporate ap

pellant seeks to affirmatively assert constitutional rights of the individual

appellants and other members not parties to this case. The corporate ap

pellant not only seeks to assert affirmatively constitutional rights of its

____________________________________________________________________________ 13.

members, which it cannot do, but it seeks to establish for itself "privi

leges and immunities" not heretofore known or enjoyed by corporations.

That a corporation is not a citizen entitled to privileges and im

munities has been consistently upheld by the United States Supreme Court

"A corporation is not a citizen, within the mean

ing of the constitutional provision, and hence has

not the privileges and immunities secured to cit

izens against state legislation. Orient Ins. Co.

v. Daggs, 19S.Ct. 281, 282, 172 U.S. 557, 43

L .ed . 552, citing Paul v. State of Virginia, 75

U.S. (8 W all.) 168, 19 L .ed . 357."

Citing numerous cases.

"A corporation is not a 'citizen', within U .S .C .A .

Const. Amend. 14, as to the abridgment of privi

leges and immunities of citizens, . . . "

Citing numerous cases.

See Words and Phrases, Permanent Edition, Volume 7,

page 261.

It is elementary that a corporation cannot assert for others rights

which it itself does not have or enjoy.

This is the obvious and compelling reason why the Court held

that a corporation cannot affirmatively assert First and Fourteenth A -

mendment Constitutional rights of its members. Hague v. Committee

for Industrial Crganizations, 307 U.S. 496, 83 L .ed . 1423, 59 S.Ct. 954.

In the Hague case, the United States Supreme Court dismissed an

injunction issued on behalf of a corporate plaintiff that was attempting to

assert personal First and Fourteenth Amendment Constitutional rights of

its members. In so doing the Court said:

Natural persons, and they alone, are entitled to

the privileges and immunities which Sec. 1 of the

Fourteenth Amendment secures for "citizens of

the United States." Cnly the individual respond

ents may, therefore, maintain this suit.

* * *

The bill should be dismissed as to all save the

individual plaintiffs, and Section B, Pars. 2, 3,

and 4 of the decree should be modified as indi

cated.

The personal constitutional rights, which corporate appellant

herein seeks to assert for its members, i . e . , freedom of speech, of as

sociations and the right to petition for redress of alleged grievances,

were involved in Hague, supra. The Court held that those rights were

personal and could only be asserted by those to whom they belonged.

A more recent case, Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31, 7 L .ed .

2d 512, 82 S.Ct. 549, held that individuals possessing "privileges and

immunities" may not be heard to complain of the alleged deprivation of

those rights on behalf of others when they, themselves, were unable to

show that they had been deprived of their constitutional rights.

Appellant relies upon cases holding that a corporation is a person,

and appellant attempts to rely on the equal protection and due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. It is equally as well established

that a corporation is a person entitled to due process and equal protection

as it is that a corporation is not a citizen entitled to privileges and im

munities guaranteed to citizens. Cf course, a corporation is a person,

Words & Phrases, Permanent Edition, Volume 32, page 351, entitled to

due process and equal protection.

The action against these appellees does not involve due process

or equal protection. It involves an attempt by a corporation to establish

16.

itself as a citizen of a state other than that of its origin and a further at

tempt by that corporation to assert constitutional rights of its members,

which it itself does not or cannot enjoy.

Cne of the privileges of a citizen of the United States is that of

moving freely from state to state. This is a personal privilege guaran

teed to citizens that is not enjoyed by corporations.

A corporation cannot move from the state of its origin to another

state without approval of the other state. The right of a state to exclude

a foreign corporation from operating and doing business within its boun

daries has been consistently upheld by the United States Supreme Court.

The rule of that Court is illustrated by Asbury Hospital v. Cass County.

North Dakota, 326 U.S. 207, 90 L .ed . 6, wherein the Court said:

The Fourteenth Amendment does not deny to the

state power to exclude a foreign corporation from

doing business or acquiring or holding property

within it. Horn Silver Min. Co. v. New York,

143 US 305, 312-315, 36 L .ed . 164, 167, 168,

12S.Ct. 403, 4 Inters. Com. Rep. 57; Hooper

v. California, 155 US 648, 652, 39 L .ed . 297,

298, 15 S.Ct. 207, 5 Inters. Com. Rep. 610;

Munday v. Wisconsin Trust C o ., 252 US 499,

6 4 L .ed . 684, 40 S.Ct. 365; Crescent Cotton

Cil Co. v. Mississippi, 257 US 129, 137, 66 L.

ed. 166, 171, 42 S.Ct. 42.

Cf course, there are exceptions to this rule; (1) those involving

interstate commerce, and (2) the deprivation of a recognized constitu

tional right. Neither of the recognized exceptions to the rule are involvec

in this case because no interstate commerce is shown to be involved and

no denial of any currently recognized constitutional right has been shown.

Thus, it is clearly shown by the record that the individual appel

lants have not and are not now asserting any claim against these appellees.

17.

The proof is clear on this point.

As heretofore shown, the State of Mississippi has a right to ex

clude the foreign non-profit corporation. The corporate appellant has

failed wholly to show that it has any right under the law of Mississippi,

or the Constitution of the United States, to force itself upon the State of

Mississippi through the processes of this Court. No discrimination what

soever was shown to have been practiced against this particular corpor

ate appellant, nor any of its members by these appellees when they de

clined to approve the application for domestication.

PRCPCSITICN in

FCREIGN CCFPCRATICNS SEEKING PERMISSICN

TC DC BUSINESS IN ANCTHER STATE MUST

CCMPLY WITH THE LAWS CF THE C THEIR STATE

Under the statutes of Mississippi, all incorporators of non-profit,

non-share corporations must be adult resident citizens of the State of

Mississippi, and no foreign non-profit, non-share corporation can be

come domesticated in this State unless it meets this requirement.

Section 5310.1, Mississippi Code of 1942, Recompiled, is the

statute of the State providing for the incorporation of non-profit corpor

ations. The statute provides for the incorporation of various types of

organizations which are generally considered to be eleemosynary in na

ture and consequently subject to being granted the privileges incident to

and generally accorded to such organizations. The statute provides that

such organizations may,

. . . be incorporated on the application of any

three (3) members, all of whom shall be adult

resident citizens of the State of Mississippi,

authorized by any of the said organizations, in

its minutes, to apply for the charter.

Sections 5339, 5340, 5341, Mississippi Code of 1942, Recompiled,

provide for the domestication of certain foreign corporations.

Section 5340, supra, provides that when such applications for

domestication have been submitted to the Governor that,

. . . he shall first take the advice of the attorney-

general of the state as to the constitutionality and

legality of the provisions of said charter or articles

of incorporation or association, and if the attorney-

general shall certify to the governor that he finds

nothing in said charter or articles of incorporation

or association that are violative of the constitution

or laws of this state, the governor of the state

may approve the same, . . . or if deemed expedi

ent by him he may withhold his approval entirely.

As heretofore pointed out, on page 6 of this brief, two-thirds of

the incorporators of the appellant corporation were resident citizens of

the State of New York. Consequently, they could not have been resident

citizens of the State of Mississippi as required by statute.

Therefore, the Attorney General had no alternative but to advise

the Governor that the application did not comply with Mississippi statutes

The undisputed proof in this case is that that provision of law has been

applied indiscriminately, and the appellant corporation was treated no

differently thatiany other foreign non-profit, non-share corporation ap

plying for domestication that did not have as its incorporators adult resi

dent citizens of the State of Mississippi.

As heretofore shown, the corporate appellant was required to be

incorporated by resident citizens of the State of New York, in compliance

with the requirements of the law of that state. Such a requirement is not

peculiar to the State of Mississippi. In fact, in 18 C. J. S. 413, Corpor

ations, Section 35 (b), the following appears:

. . . and the statutes usually require that at least

a certain number of the original subscribers or

incorporators, and sometimes that all of them,

shall be residents or citizens of the United States

and of the state, and such a provision is manda

tory.

We submit that the corporate appellant by its failure to comply

with the provision of the statute quoted above was barred from becoming

domesticated in the State of Mississippi because it could not have been in

corporated in this State in the first instance.

Assuming, arguendo, that the corporate appellant had in all re

spects complied with the law of this State, we submit that this Court is

without authority to order these appellees to approve the application for

domestication by writ of permanent mandatory injunction.

The issuance of such an injunction to affirmatively require a pub

lic official to perform an act is, in effect, equivalent to a writ of manda

mus, and is governed by like considerations, Miguel v. M cCarl. 291 U.S.

442, 54 S. Ct. 465, 78 L .ed . 902.

Section 5340, supra, clearly and beyond question vests discretion

in the Governor of the State of Mississippi as to whether or not he will

grant an application for domestication of a foreign corporation when it

provides for the granting of such an application and then provides " . . .

or if deemed expedient by him he may withhold his approval entirely. "

The remedy of mandamus is, in the main, re

stricted to situations where ministerial duties

of a nondiscretionary nature are involved, as

where the matter is peradventure clear, or an

20.

administrative agency is clearly derelict in fail

ing to act, or the action or inaction turns on a

mistake of law. Panama Canal Co. v. Grace

Line, Inc. . 356 US 309, 78 S.Ct. 752, 2 L .ed .

2d 788.

As heretofore shown, the act performed by the former governor

of Mississippi in rejecting the application of corporate appellant was

clearly the exercise by him of discretion vested in him by the statutes

and laws of the State, which said laws shall be regarded as rules of de

cision by this Court, 28 U. S. C. 1652.

Mandamus is governed by equitable considera

tions and is to be granted only in the exercise

of sound discretion. Whitehouse v. Illinois

Cent. R. Co. . 349 U.S. 366, 75 S.Ct. 845, 99

L. Ed. 1155.

The power of federal courts, under 28 USC Sec.

1651, to issue the extraordinary writs of manda

mus and prohibition is discretionary and is spar

ingly exercised. Parr v. United States. 351 US

513, 76 S.Ct. 912, lOOL.ed. 1377.

PRC PC SI TIC N IV

THE DISTRICT CCURT DID NCT ABUSE ITS DISCRETICN

IN DECLINING TC GRANT THE RELIEF PRAYED FCR.

AND UNDER ESTABLISHED RULES CF LAW AND EQUITY

THIS CCURT SHCULD DECLINE TC CRDER THE ISSUANCE

CF A PERMANENT MANDATCRY INJUNCTICN AGAINST

THESE APPELLEES CN THE RECCRD PRESENTED

As a matter of federal constitutional law, the State of Mississippi

is not prohibited from barring foreign corporations from doing business

within its boundaries. The right to exclude foreign corporations similar

to the corporate appellant carries with it the right to provide certain con

ditions upon which such foreign corporations may be permitted to do bus

iness within the State. Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, North Dakota,

supra.

21.

The undisputed proof shows that this right of the state has been ex

ercised without discrimination, and the corporate appellant has failed

wholly and completely to show that it has a right in law or equity to have

its application for domestication approved by these appellees. Failing

wholly and completely to show a legal or equitable right the corporate ap

pellant has failed to meet the burden which it assumed by coming into this

Court.

Additionally, neither the corporate appellant nor the individual ap

pellants have shown by competent proof any injury whatsoever to the cor

poration, or to them as individual members thereof, by the refusal of the

State of Mississippi to grant the corporate appellant permission to do bus

iness in this State.

Having failed wholly to establish any legal or equitable right to the

relief sought against these appellees, we submit that no cause for relief

against these appellees has been shown which would authorize this Court

to order the issuance of a permanent mandatory injunction.

A mandatory injunction is an extraordinary reme

dial process which is granted not as a matter of

right, but in the exercise of sound judicial d iscre

tion. Morrison v. Work, 266 US 481, 45 S Ct 149,

69 L ed 394.

A mandatory injunction is not granted as a matter

of right, but is granted or refused in the exercise

of a sound judicial discretion. Moor v. Texas &

N .C .R . C o., 297 US 101, 56S.Ct. 372, 80 L .ed.

509.

In United States v. Greene County Board of Education, 332 Fed.

Rep. 2d. , 40, this Court summarized the rule for appellate review of a

District Court's denial of a permanent mandatory injunction in the follow

ing language:

The rule applicable to injunctions was announced

early in the history of this country by Justice Bald

win, sitting at Circuit in 1830 in Bonaparte v. Cam

den, (C .C .N .J . 1830) Fed. Cases No. 1617: "There

is no power the exercise of which is more delicate,

22.

which requires greater caution, deliberation, and

sound discretion, or more dangerous in a doubtful

case, than the issuing an injunction; * * The

rule applicable in the Fifth Circuit was succinctly

stated by Judge Hutcheson in Reliable Transfer Com

pany v. Blanchard, (5th Cir. 1944) 145 F.2d 551.

"In thus arguing, appellant proceeds upon the whol

ly incorrect assumption that, conceding power, the

issuance of the injunctions was mandatory. It is

horn book law that 'Courts of equity exercise dis

cretionary power in the granting or withholding of

their extraordinary remedies, and that although

this discretionary power is not restricted to any

particular remedy, it is particularly applicable to

injunction since that is the strong arm of equity and

calls for great caution and deliberation on the part

of the cou rt.1 [Citing cases. ] "Here again it is

horn book law that whether an injunction will or

will not issue rests within the sound discretion of

the court, and that the exercise of this discretion

will not be disturbed unless there has been a clear

abuse of it, 45 Am. J u r ., Sec. 180, p. 936."'

* * *

Discretion of the Trial Court must clearly be abused

before appellate courts will reverse for failure to

grant a mandatory injunction. United States v. W .T.

Grant Co. 345 U.S. 629. 73 S.Ct. 894. 97 L .Ed„

1303 (1952): "The chancellor's decision is based on

all the circumstances; his discretion is necessarily

broad and a strong showing of abuse must be made

to reverse it. "

APPELLANT'S CASES DISTINGUISHED

The cases relied upon by the corporate appellant fall in three cate

gories. Those categories are: (1) Those cases involving interstate com

m erce where the Court held that the rule that a state may exclude foreign

corporations from doing business within its boundaries must yield to the

superior right of the Federal Government to regulate and encourage the

free-flow of interstate commerce, (2) Those cases involving a state's

attempt to deprive a corporation of due process of law by placing as a

condition to the granting the corporation permission to do business within

the state a requirement that the corporation relinquish a constitutional

right protected by and involving due process, and (3) Those case involv

ing this corporate appellant wherein the Court held that the corporation

could defensively assert constitutional rights of its members, i . e . , free

dom of association, when its failure to do so might tend to effectively de

ny the right of association to the members.

The cases involving interstate commerce do not and cannot have

any bearing on the case at bar for the simple and obvious reason that

there is no showing whatsoever that this corporation has been, is now or

anticipates being engaged in interstate commerce. The first category

of cases relied upon are thus completely and wholly inapplicable to the

facts presently before the Court.

The second category of cases is likewise inapplicable because, as

heretofore shown, due process of law is not herein involved. There is in

volved an effort on the part of the corporate appellant to affirmatively as

sert constitutional rights of its members and establish for itself "privi

leges and immunities" under the Fourteenth Amendment, supra, which,

as discussed in Proposition II hereof, cannot be enjoyed by corporations.

I

The last category of cases relied upon by appellant are likewise

inapplicable because in those cases all the Court did was hold that if the

corporation was not permitted to defensively assert the constitutional

rights of its members, because as the Court said itself, failure to do so

would result in nullification of the right at the very moment of its asser

tion.

The situation before the Court in those cases was entirely differ

ent from the case presently before the Court. In those cases, states had

sought to obtain membership lists of the local members of appellant cor- 1

1 - N .A .A .C .P . v. Alabama. 357 U.S. 449, 2 L. Ed. 2d 1488, 78 S.Ct.

1163; Bates v. City of Little Pock. 361 U.S. 516, 4 L .E d ^ 4 8 0 ,

80S.C t. 412; Louisiana, ex rel. Jack Gremillion v. N .A .A .C .P ..

e ta l, 366 U.S. 293, 6 L .E d .2d 301, 81S.C t. 1333.

24.

poration. The states had taken the offensive and the Court simply held

that the corporation could stand between the state and its members when

its failure to do so might tend to deprive the members of a constitutional

right.

In the case presently at bar, no showing whatsoever had been made

that these appellants have or are seeking to deprive the individual members

of the corporate appellant of any constitutional rights. The record is total-

ly void of any such proof.

There is no showing whatsoever of discrimination by these appel

lees against the corporate appellant or the individual appellants. No de

nial of the freedom of association is shown.

C O N C L U S I O N

We have, therefore, shown in reason and authority that the judg

ment of the District Court dismissing the complaint against these appel

lees should be sustained.

The Court is without jurisdiction over these appellees because

their acts are the acts of the State of Mississippi and compulsion against

them by the Court will be compulsion against the State of Mississippi and

is, therefore, prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment, supra.

, The Court is without jurisdiction of the subject matter because a

state is not prohibited by any provision of the Federal Constitution from

denying foreign corporations the privilege of doing business within its

borders. The right to exclude or place conditions upon the granting of

the permission, is basic and has long been the law of this land. Corpora

tions are not vested with "privileges and immunities" granted by the

Fourteenth Amendment, supra, even though they are persons within the

meaning of the due process clause of that amendment. A corporation

cannot affirmatively assert personal constitutional rights of its members,

No discrimination in the application of Mississippi law has been

shown. In the absence of a showing of discrimination against the corpor

ate appellant, no relief should be granted.

The District Court did not abuse its discretion in declining to is

sue the permanent mandatory injunction and its Judgment in so doing

should be affirmed by this Court.

We, therefore, respectfully ask that this Court render its opinion

affirming the District Court's opinion in this case.

Respectfully submitted,

JCE T. PATTERSCN, ATTORNEY GENERAL

STATE CF MISSISSIPPI

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi

MARTIN R. McLENDCN, ASSISTANT ATTOR

NEY GENERAL, STATE CF MISSISSIPPI,

New Capitol Building,

Jackson, Mississippi

&L' ‘f r j

MARTIN R. McLENDCN

Attorney for Appellees

C E R T I F I C A T E CF S E R V I C E

I, MARTIN R. McLENDCN, attorney of record for these appellees

do hereby certify that I have this day served a true and correct copy of

the above and foregoing brief upon the attorneys of record for the appel

lants by mailing copies to them United States postage prepaid at the ad

dresses shown in appellants' brief.

THIS the 29th day of January, 1965.

o lL n r^ ,

MARTIN R. McLENDCN.