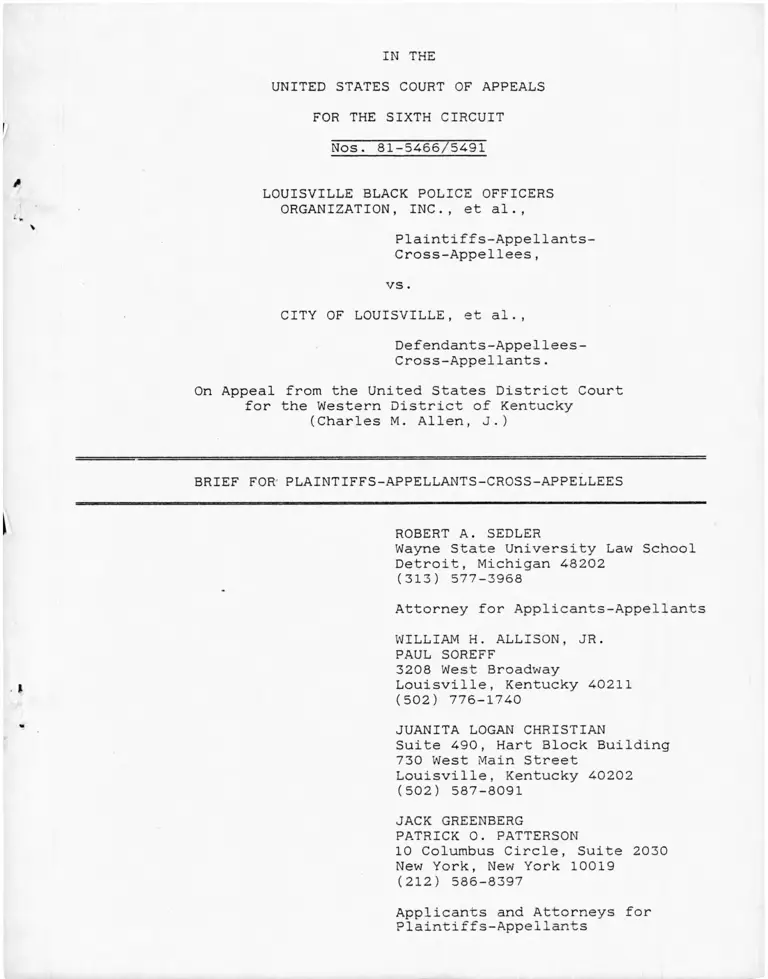

Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross-Appellees

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross-Appellees, 1981. 46cacaec-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fa6aa343-1c7d-4e30-a9f8-16c4e799932c/louisville-black-police-officers-organization-inc-v-city-of-louisville-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants-cross-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 81-54-66/5491

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appel1ants-

Cross-Appellees,

vs.

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-

Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Kentucky

(Charles M. Allen, J.)

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS-CROSS-APPELLEES

ROBERT A. SEDLER

Wayne State University Law School

Detroit, Michigan 4-8202

(313) 577-3968

Attorney for Applicants-Appellants

WILLIAM H. ALLISON, JR.

PAUL SOREFF

3208 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 4-0211

(502) 776-1740

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 490, Hart Block Building

730 West Main Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

(502) 587-8091

JACK GREENBERG

PATRICK 0. PATTERSON

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Applicants and Attorneys for Plaintiff s-Appellants

Table of Contents

Table of Authorities ..............................

Statement of the Issues Presented ................

Statement of the Case ......... ...................

Argument ..........................................

I. The actions of the District Court in

refusing to adjust the award for the

effect of inflation, in refusing to

award attorneys' fees to the NAACP

Legal Defense Fund on a basis that

represents the reasonable value of

services furnished by the Fund, and in

reducing documented hours spent in good

faith representation of the plaintiffs,

are inconsistent with the fundamental

purpose and underlying policies of the

federal civil rights attorneys' fees

statutes ................................

II. The District Court erred in entering

an award of attorneys' fees in 1981 for

services performed in the period 1974-

1979, on the basis of the value of

attorney services at the time they were

performed without adjusting the award

for the effect of inflation ............

III. The District Court erred in refusingto award attorneys' fees for the services

performed by NAACP Legal Defense Fund

attorneys on the basis of the reasonable

value of those services, taking into

account the Fund's institutional repu

tation and expertise, the background and

experience of its attorneys and the

customary rates charged by comparable

attorneys and law firms for similar

services.................................

Page

IV. The District Court erred in reducing,

without any evidentiary basis, the

documented hours spent in the prepara

tion of the plaintiffs' post-trial brief,

proposed findings of fact and conclusions

of law, and post-trial reply brief, on

the ground that, in the opinion of the

District Court, the amount of time spent

in such preparation was "excessive." .... 46

Conclusion ......................................... 50

Addendum A: Summary of Rates Requested

and Awarded

Addendum B: Statutes Involved

i

11

Table of Authorities

Cases

Aamco Automatic Transmissions, Inc. v.Tayloe, 82 F.R.D. 405 (E.D. Pa. 1 979) ........ 31

In re Ampicillin Antitrust Litigation,

81 F.R.D. 395 (D.D.C. 1978) ....................... 32

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S.

350 ( 1977) ................................... 17

City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 560

F. 2d 1 093 (2d Cir. 1977) ..................... 19,32

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C.

Cir. 1980 ) (en banc) ......................... 19

Page

Gates v. Collier, 616 F.2d 1268 (5th Cir.

1980) 18

Gulf Oil Co. v. Bernard, ___U.S. ___, 101

S. Ct. 2193 ( 1 981 ) ........................... 34

Harkless v. Sweeney Independent School District,

608 F. 2d 594 (5th Cir. 1979) ................. 21

Harkless v. Sweeney Independent School District,

466 F. Supp. 457 (S.D. Tex. 1978),

aff'd, 608 F. 2d 594 (5th Cir. 1 979) .......... 31

Jones v. Armstrong Cork Co., 630 F.2d 324 (5th

Cir. 1980) ................................... 44

Knutson v. Daily Review, Inc., 479 F. Supp.1263 (N.D. Cal. 1 979) ......................... 32

Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc. v. American Radiator

& Standard Sanitary Corp., 487 F.2d

161 (3d Cir. 1 973) ............................. 19

Lockheed Minority Solidarity Coalition v.

Lockheed Missiles, 406 F. Supp. 828

(N.D. Cal. 1976) .................

- iii -

32

Page

McPherson v. School Dist. No. 186, 465 F. Supp.

749 (S.D. 111. 1 978) ......................... 32

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 41 5 ( 1963) .............. 34,36

Northcross v. Board of Education, Memphis City

Schools, 611 F.2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979),

cert, denied, 447 U.S 91 1 (1980) ............. passim

Seals v. Quarterly County Court, 562 F.2d 390

(6th Cir. 1977) ............................... 18

Vecchione v. Wohlgemuth, 481 F. Supp. 776

(E.D. Pa. 1 979) ............................... 31

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................... 3,15

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................... 3,1 5

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of

1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1 988 ...................... passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq......... passim

Legislative History

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976) 16,17,40

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.(1976) 15,16,19,20,40,44

Other Authorities

A. Miller, Attorneys' Fees in Class Actions

(Federal Judicial Center 1980) ........ 19,32-33,41-42

Attorney Fee Awards in Antitrust and Securities

Class Actions, 6 Class Action Reports

82 ( 1980) ..................................... 44

New York Times, Aug. 26, 1981 28

- iv -

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 81-5466/5491

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-

Cross-Appellees,

v s .

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-

Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Kentucky

( Charles M. Allen, J.)

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS-CROSS-APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether the District Court erred in entering an

award of attorneys' fees in 1981 for services performed in

the period 1974-1979, on the basis of the value of attorney

services at the time they were performed, without adjusting

the award for the effect of inflation, either directly or by

awarding the current value of attorney services.

2. Whether the District Court erred in refusing to

award attorneys' fees for the services performed by NAACP

Legal Defense Fund attorneys on the basis of the reasonable

value of those services, taking into account the Fund's

institutional reputation and expertise, the background and

experience of its attorneys, and the customary rates

charged by comparable attorneys and law firms for similar

services.

3. Whether the District Court erred in reducing the

documented hours spent in preparation of the plaintiffs'

post-trial brief and reply brief because, in the Court's

opinion, the amount of time spent in such preparation was

"excessive," and whether the Court erred further in arriving

at this determination without holding an evidentiary hearing

on the question.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The appellants (hereinafter referred to as the

"applicants") are the attorneys for the plaintiffs in

Louisville Black Police Officers Organization, Inc., et al.

v. City of Louisville, et al., Civil Action No. C 74-106

L,(\A) , in which the plaintiffs successfully challenged the

racially discriminatory employment practices of the City of

2

Louisville Police Department. See 20 F.E.P. Cases 1195 (W.D.

Ky. 1979). (App. 28, 57). The present appeal is from the

District Court's award of interim attorneys' fees covering

the period from the commencement of the action in March,

1974, to September 18, 1979, when the District Court ruled in

favor of the plaintiffs and entered a preliminary injunction

with respect to the hiring of black police officers.

The discrimination suit was brought initially under 42

U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983, and alleged a violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment rights of the plaintiffs. The complaint

was amended in January, 1976, and March, 1977, to allege

claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq. Class certification orders

were entered on June 27, 1975, and April 22, 1977. The

Fraternal Order of Police intervened as a defendant in 1975

but is not involved in this appeal.

On March 7, 1977, trial commenced in the District Court

on the issues of discrimination in recruitment, entry-level

testing, selection and hiring. The case was tried in stages,

and took five weeks of trial time. After the final transcript

of the proceedings was completed and filed in May, 1978, the

parties jointly requested and the Court granted additional

time for filing post-trial briefs in order to allow settlement

negotiations. These negotiations were unsuccessful, and in

3

September, 1978, counsel for plaintiffs filed their post

trial brief and proposed findings of fact and conclusions of

law. The defendants then retained a Washington, D.C., law

firm and, after being granted a series of extensions of time,

filed their post-trial briefs, proposed findings of fact and

conclusions of law in February, 1979. The plaintiffs filed

their post-trial reply brief in May, 1979.

On September 18, 1979, the District Court issued findings

of fact, conclusions of law and a memorandum opinion, and

entered a preliminary injunction. 20 F.E.P. Cases 1195

(App. 28, 57). The Court found, inter alia, that the City

had a history of racial segregation and discrimination in its

police employment practices. Moreover, until 1974 the City

had selected officers by means of unvalidated written tests

and unstructured, subjective oral interviews. In the ten

years preceding the filing of this lawsuit, only 11 of the

328 officers accepted into recruit classes were black. As

late as 1976-1977, the City used an unlawful discriminatory

ranking system which kept qualified black applicants from

getting jobs on the police force. In 1974, when the suit

was filed, black officers held only 5.6% of the positions on

the Louisville police force, and by 1977, when the case was

tried, blacks still constituted only 7.4% of the force. In

contrast, in 1970 23.8% of the residents of the City of

4

Louisville were black, and the Court found that the relevant

labor market was approximately 15% black. Based upon these

and other findings of fact and conclusions of law, the Court

entered a preliminary injunction requiring the City to appoint

at least one black police recruit for every two white recruits

appointed for the next five years. The Court also held that

plaintiffs' counsel were entitled to recover interim attorneys'

fees. (App. 54) .

In May, 1980, after extensive settlement negotiations,

the parties signed a consent decree which subsequently was

approved by the District Court. As the Court stated in its

findings with respect to the fee application:

"On May 2, 1980, the parties signed a consent decree which substantially incorporated the remedies

set out in the Court's preliminary injunction, and

which, in part, provided relief over and beyond

that which has been set out in the preliminary

injunction. The consent decree mandates that one

out of every three persons appointed to the Police

Recruit School during the next five years be persons

of the black race. It is contemplated that at the

end of five years approximately 15% of the Force will

be composed of black persons.

"In addition the consent decree sets forth

detailed provisions regarding testing, medical

examinations, background investigations, and

recruiting; it provides for regulation of recruit

training with the objective in mind of all applicants

who enter the recruit school shall graduate [sic]; it

provides for the assignment of black officers within

certain units so as to overcome their historic

underrepresentation; it contains an affirmative

promotional remedy with a promotional schedule to

achieve 15% black representation. It sets forth

detailed standards and procedures regarding discipline;

it contains extensive reporting requirements; it pro

5

vides back pay settlement funds for claims of

discrimination in promotion in the amount of

$150,000, and for claims of discrimination in

discipline in the amount of $85,000.'' (App. 324-25).

The consent decree did not resolve the question of interim

attorneys' fees, and despite substantial negotiations, the

parties were unable to agree on this matter.

The principal attorney for the plaintiffs at the time

the suit was filed in 1974 was William Allison of Louisville,

who had been admitted to practice in 1969. (App. 62, 325).

In 1974-1975 he was assisted by Henry Hinton of Louisville.

(App. 62, 327). Paul Soreff first became involved in the case

in 1975, while still a law student. He was admitted to

practice in 1976, and then joined Mr. Allison in practice

and in this case. (App. 62, 326). Because of the complexity

of this case and its determined and vigorous contention by

the City, Attorneys Allision and Soreff concluded that they

would need expert assistance in litigating the case. They

first asked the United States Department of Justice to become

involved in the case. When that request was denied, they

turned to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(hereinafter "Legal Defense Fund" or "LDF"). The Legal

Defense Fund agreed to participate, and Fund lawyers entered

the case as counsel for the plaintiffs in 1976. (App. 62, 63,

326). )

The necessity for the involvement of the Legal Defense

Fund and the contributions of the Fund's attorneys to the

6

successful prosecution of the case are detailed at length in

an affidavit filed by Mr. Allison. (App. 360-61). Patrick

0. Patterson, an experienced LDF specialist in employment dis

crimination litigation, was the primary Legal Defense Fund attorney

assigned to the case. He was assisted by Deborah M. Greenberg,

another experienced LDF staff attorney specializing in employment

litigation; by Kristine S. Knaplund, a volunteer attorney at LDF;

and by paralegals and other members of the LDF staff. Although

other Legal Defense Fund attorneys reviewed documents and confer

red with Mr. Patterson on the case, no compensation was claimed

for their services. (App. 72-73). Juanita Logan Christian

performed substantial services for the plaintiffs while serving as

an Earl Warren Fellow at the Legal Defense Fund in 1977, and then

served as additional counsel for the plaintiffs when she subse

quently entered private practice in Louisville. Some work was

also performed by Frederic Cowden of Louisville in 1977. (App.

63, 213).

The application for the award of interim attorneys'

fees, costs and expenses was filed on August 28, 1980. (App.

59). In support of their application, the applicants

submitted detailed time logs showing the hours that each

attorney expended on the case, affidavits showing the

qualifications and experience of each of the applicants, and

affidavits of Louisville practicing attorneys relative to

7

the prevailing rates for attorney services in the Louisville

area. The applicants sought interim attorneys' fees in the

amount of $629,182, and costs and expenses in the amount of

$23,468.03. (App. 65-66). The City of Louisville vigorously

contested the application, contending that the applicants

were entitled to recover no more than $136,336 as interim

attorneys' fees. (App. 230). The City submitted affidavits

of other Louisville practicing attorneys on the issue of

prevailing rates for attorney services in the Louisville

area. The District Court concluded that it was not necessary

to hold an evidentiary hearing on the application.

On February 12, 1981, the Court issued its findings of

fact, conclusions of law and memorandum opinion (App. 324 ),

and entered a judgment thereon. (App. 2 3 9 ). On March 17,

1981, the Court issued a memorandum opinion clarifying its

judgment (App. 341) and entered a final judgment. (App. 346).

The District Court resolved all of the principal controverted

issues in favor of the City, except for the issue of the

entitlement of the applicants to a contingency adjustment,

and awarded interim attorneys' fees in the amount of $256,271.89-

(App. 339, 346). The Court also awarded the costs and expenses

requested by the applicants. (App. 340).

The principal controverted issues between the applicants

and the Cityfand the resolution of these issues by the District

Court, may be summarized as follows: There was substantial dis

8

agreement as to the prevailing rates for attorney services

in the City of Louisville, both at the time the services in

question were rendered and as of 1981. The District Court

resolved this issue substantially in accordance with the

City's submission as to prevailing hourly rates at the time

1/the applicants' services were performed. The Court held

that the hourly rate to be awarded to the Legal Defense

2/Fund for services Ms. Greenberg performed in 1977, when

she had been admitted to practice for 20 years, was $75 for

office services and $106 for in-court services. (App. 333,

344). The District Court held that the hourly rates for

the other attorneys should be based on attorney experience at

the time the services were rendered, and divided the attorneys

into three categories: (1) "inexperienced," zero to two

years; (2) "intermediate," two to seven years; and (3) "fully

experienced," over seven years. There was also to be a 40

percent differential for courtroom work. (App. 333).

1/ While the applicants continue to disagree with the District

Court's findings with respect to prevailing Louisville rates

during the period 1974-1979, they concede that those findings

are not "clearly erroneous," and so cannot be challenged in

the present appeal.

2/ The applicants requested that fees for the services of

LDF staff attorneys be awarded directly to the Legal Defense

Fund itself. Fees awarded individually to attorneys employed

by the Fund are turned over to the Fund. (App. 69, 353).

9

The District Court placed Mr. Allison, who was admitted

to practice in 1969, in the "intermediate" category for the

years 1974-1976, and awarded him $50 per hour for office

services. For the years 1977-1979, Mr. Allison was placed in

the "fully experienced" category and was awarded $65 per hour

for office services. Mr. Patterson, an LDF specialist in

employment discrimination litigation who was admitted

to practice in 1972, was placed in the "intermediate" category

and awarded $50 per hour for office services rendered in

1976 through 1979. Mr. Soreff, who was admitted to practice

in 1976, was awarded $40 per hour for office services performed

during his first two years of practice, and $60 per hour for

°ffice services thereafter.— Mr. Hinton was compensated at

the rate of $50 per hour for office services, and Mr. Cowden,

. . 4 /Ms. Christian, — and Ms. Knaplund were each compensated at

the rate of $40 per hour for office services. The rates

requested by the applicants and awarded by the Court are

summarized in chart form in Addendum A to this brief.

3/ There is an inconsistency here. Mr. Soreff was compensated at the rate of $60 per hour for office services when he was

in the "intermediate" experience category, but Mr. Allison

and Mr. Patterson were compensated at the rate of $50 per

hour for office services while they were in the same category.

£/ Here there is another inconsistency. Ms. Christian was

in her third year of practice in 1979 and therefore should

have been placed in the Court's "intermediate" category for

that year. However, the Court set her rate for 1979 at the

lowest, "inexperienced" rate of $40 per hour.

10

The parties also disagreed as to the appropriateness of

a contingency adjustment. The City, despite its determined

and vigorous defense of the discrimination case and its

retention of a Washington, D.C., law firm to represent it,

contended that there should be no contingency adjustment at

all. The applicants sought a 50 percent contingency adjust

ment.’ The District Court awarded a 33.3 percent contingency

adjustment. (App. 342). —^

The third point of contention related to an adjustment

of the award to take account of inflation. The applicants

based their claim for the value of attorneys' services on

the market value of those services at the time they were

rendered, and contended that the award should be adjusted

for inflation directly according to the Consumer Price Index.

(App. 65). They also set forth in detail how such an ad-

67justment should be made. (App. 201-02, 277-81, 316-20)r The

5/ Although the applicants continue to believe that a higher

contingency adjustment would be appropriate, they recognize

that the District Court has a wide range of discretion in

determining a proper contingency adjustment. The applicants

therefore have not challenged this aspect of the award in

the present appeal.

6/ For example, the requested rate of $75 an hour for work

done by Mr. Allison in 1974 was adjusted to $130.35 in

November 1980 dollars to account for the decline in the

value of the dollar in the intervening period, as reflected

in the Consumer Price Index. The historical rates, CPI

inflation factors, and adjusted rates requested by each

attorney are set forth in Addendum A hereto.

11

City argued in response that "an hourly rate based on hourly

rates prevailing at the present time will adequately

compensate for inflation since 1974 and no additional

adjustment is warranted." (App. 226) (emphasis added). On

this issue, the District Court gave the City more than it

asked for. The Court held that the value of attorney services

had to be determined at the time the services were rendered

and refused to make any adjustment at all for inflation.

(App. 337).

The other main point of disagreement was over the

reduction in documented hours. The City claimed that there

should be a sweeping reduction in the documented hours

claimed by the applicants, but did not identify any particular

hours that should be reduced. The District Court, without

holding an evidentiary hearing on the question, held that the

amount of time spent by the applicants in preparation of

their posttrial brief, their proposed findings of fact and

conclusions of law, and their post-trial reply brief was

"excessive." The Court reduced the documented hours for the

post-trial brief and proposed findings and conclusions by

25 percent, and for the post-trial reply brief by 50 percent.

(App. 335).

The applicants filed a motion to alter or amend the

judgment on March 30, 1981. (App. 348 ). In this motion

12

the applicants asked the District Court, inter alia, to

award attorneys' fees based on the present value of attorney

time, since it had refused to adjust directly for inflation,

and to restore the documented hours spent in preparation of

the post-trial brief, proposed findings and conclusions, and

post-trial reply brief that it had eliminated. In addition,

because the value of attorney time according to prevailing

rates in the City of Louisville, as determined by the District

Court, was so much lower than the value of such time as set

forth in the affidavits previously submitted by the applicants,

an award based on such hourly rates would not adequately

reflect the reasonable value of the attorney services furnished

by the Legal Defense Fund. Accordingly, the applicants

requested that the District Court award fees to the Legal

Defense Fund on the basis of prevailing hourly rates which are

reasonable in light of the Fund's institutional reputation

and expertise, the background and experience of its attorneys,

and the customary rates charged by comparable lawyers and

law firms for similar services. —^ The current (1981) rates

requested in the applicants' motion to alter or amend the

7/ In this regard the applicants submitted an affidavit of

Marvin E. Frankel, a former United States District Judge for

the Southern District of New York who is now the managing

partner of a major New York City law firm. Judge Frankel's

affidavit, which was not challenged by the City, states

that, based on the facts of record concerning the experience

and ability of the Legal Defense Fund attorneys in this

case, current (1981) base rates of $160 per hour for Ms.

Greenberg and $120 per hour for Mr. Patterson are reasonable

and comparable to the rates charged by attorneys of

comparable experience and ability in first-class New York

law firms. (App. 428). The applicants also submitted copies

of recent decisions from various parts of the country awarding

base rates of $125 to $135 an hour for services performed by

LDF staff attorneys and other comparable specialists in civil

rights litigation. (App. 371-426) .

13

judgment are set forth in Addendum A to this brief- The

District Court refused to amend its judgment in any

respect and, on June 3, 1981, denied the motion. (App.

431). A notice of appeal was filed on June 19, 1981.

(App. 435).

ARGUMENT

I.

The Actions of the District Court in Refusing to

Adjust the Award for the Effect of Inflation, in

Refusing to Award Attorneys' Fees to the NAACP

Legal Defense Fund on a Basis That Represents the

Reasonable Value of Services Furnished by the Fund,

and in Reducing Documented Hours Spent in the Good

Faith Representation of the Plaintiffs, Are

Inconsistent with the Fundamental Purpose and

Underlying Policies of the Federal Civil Rights

Attorneys' Fees Statutes.

In the subsequent sections of the Argument, the

applicants will set forth in detail the reasons why the

District Court erred in taking each of the actions that is

challenged in the present appeal. In this section, the

applicants will address what may be called the "common

ground of error" — that the challenged actions of the

District Court are inconsistent with the fundamental purpose

and underlying policies of the federal civil rights attor

neys' fees statutes, as recognized and implemented by this

Court's decision in Northcross v. Board of Education,

Memphis City Schools, 611 F.2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979), cert.

14

denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980).

Fees were awarded in the present case pursuant to the

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988, and § 706(k) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k). See Addendum

B. The fundamental purpose of these fee award statutes

is to insure the effective enforcement of the substantive

federal constitutional and statutory rights established by

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983, Title VII and related civil

rights statutes, by providing adequate compensation for the

attorneys who have successfully represented victims of civil

rights violations. As the Senate Judiciary Committee stated

in its report recommending passage of the Civil Rights

Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976 (hereinafter the "Fees

Act"):

"[The] civil rights laws depend heavily

upon private enforcement, and fee awards have

proved an essential remedy if private citizens

are to have a meaningful opportunity to vindicate

the important Congressional policies which these

laws contain.

"In many cases arising under our civil rights

laws, the citizen who must sue to enforce the law

has little or no money with which to hire a lawyer.

If private citizens are to be able to assert their

civil rights, and if those who violate the Nation's

fundamental laws are not to proceed with impunity,

then citizens must have the opportunity to recover

what it costs them to vindicate these rights in

court.

15

" . . . 'Congress therefore enacted the

provision[s] for counsel fees . . . to encourage

individuals injured by racial discrimination to seek

judicial relief . . .'" S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. 2-3 (1976), quoting Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

Congress enacted these fee-shifting statutes to insure

"vigorous enforcement of . . . civil rights legislation, while

at the same time limiting the growth of the enforcement

bureaucracy." S. Rep. No. 94-1011, at 4. As the House

Judiciary Committee stated in its report on the Fees Act:

"The effective enforcement of Federal civil

rights statutes depends largely on the efforts of

private citizens. Although some agencies of the

United States have civil rights responsibilities,

their authority and resources are limited. In

many instances where these laws are violated, it

is necessary for the citizen to initiate court

action to correct the illegality . . . . [The Fees

Act] is designed to give such persons effective

access to the judicial process where their

grievances can be resolved according to law." H.Rfl,

Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 1 (1976).

8/ The present case is one in which it was clearly necessary Tor the plaintiffs to initiate court action to vindicate

their civil rights and those of the classes they represented.

Indeed, the plaintiffs' Louisville attorneys specifically

requested that the Department of Justice intervene in the

case. Only when the Government declined to participate did

the NAACP Legal Defense Fund become involved, and only after

years of hard-fought litigation was the City compelled to

make sweeping changes in its discriminatory employment

practices.

16

Congress was also cognizant of "the real-life fact that

lawyers earn their livelihood at the bar," Bates v. State Bar

of Arizona, 433 U.S. 350, 368 (1977), and that relatively few

attorneys were available to represent victims of racial

discrimination and other civil rights violations. Not only

would such representation generally involve controversial and

politically unpopular cases, with the resulting personal and

professional repercussions for the attorney, but the victims

of civil rights violations rarely were able to afford to pay

for the attorney's services. The House Judiciary Committee

found that there was a "compelling need" for the Fees Act,

citing evidence that "private lawyers were refusing to take

certain types of civil rights cases because the civil rights

bar, already short of resources, could not afford to do so."

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, at 3. As this Court has stated: "The

entire purpose of the statutes was to ensure that the

representation of important national concerns would not depend

upon the charitable instincts of a few generous attorneys."

9 /Northcross at 638. —

9/ As stated in the affidavit of Shelby Lanier, the President

of the Louisville Black Police Officers Organization and a

named plaintiff in this action, in 1973-1974 the organization

approached a number of attorneys who "either were not

interested [in representing the plaintiffs], due to the

controversial and complex nature of the suit, or demanded

the payment of some fee before proceeding." (App. 313). If William Allison had not agreed to represent the plaintiffs

without payment in advance, "this suit may never have been

brought and the discrimination against Blacks in hiring,

promotion, assignments and discipline by the Louisville

Police Department would not even have begun to be dealt

with." (App. 314).

17

Recognition of the purpose of the federal civil rights

attorneys' fees statutes is illustrated by the extremely

liberal construction given to those statutes by the courts.

As this Court has noted, these statutes "should be liberally

construed to achieve the public purposes involved in the

congressional enactment." Seals v. Quarterly County Court,

562 F.2d 390, 393 (6th Cir. 1977). As another court has

observed in regard to the Civil Rights Attorney's Fees

Awards Act of 1976: "Recognizing Congress' clear signals

to apply the Act 'broadly to achieve its remedial purpose,'

Courts have taken an extremely liberal view on nearly every

interpretative question that has arisen thus far under

§1988." Gates v. Collier, 616 F.2d 1268, 1275 (5th Cir.

1980) (citation omitted).

In Northcross, this Court held that the fundamental

purpose and underlying policies of the federal civil rights

attorneys' fees statutes would be best implemented by adopting

an analytical approach to awards of attorneys' fees. Such

an approach, this Court found, "will result in an award

reflecting those considerations traditionally looked to in

making fee awards, but will also provide a logical, analytical

framework which should largely eliminate arbitrary awards

based solely on a judge's predispositions or instincts."

Northcross at 643. The essence of the Northcross approach is

to base the award on the fair market value of the attorney's

services, which is primarily determined by looking to (1)

the number of documented hours expended on the case and (2)

the reasonable value of the time of the particular attorney.

Id. at 642-643. As this Court concluded in Northcross:

"Focusing on the fair market value of the attorney's services

will best fulfill the purposes of the Fees Awards Act, by

providing adequate compensation to attract qualified and

competent attorneys without affording any windfall to those

who undertake such representation." Id. at 638. i2/

What the Northcross approach means in the final analysis

is that the services of attorneys in civil rights cases are

deemed to have the same market value as the services of

attorneys in any other case. Congress expressly stated its

intention that "the amount of fees awarded under [the Fees

Act] be governed by the same standards which prevail in

other types of equally complex Federal litigation, such as

antitrust cases and not be reduced because the rights involved

may be nonpecuniary in nature." S. Rep. No. 94-1011, at 6.

Thus, the victim of a civil rights violation should be entitled

10/Qther Circuits have adopted substantially similar approaches to the calculation of counsel fees under federal statutes

providing for fee awards. See Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F. 2d

880 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (en banc); City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 560 F.2d 1093 (2d Cir. 1977); Lindy Bros. Builders^

Inc, v. American Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corp., 487 F.2d

161 (3d Cir. 1973). See generally, A. Miller, Attorneys1

Fees in Class Actions, at 60-184 (Federal Judicial Center 1980) .

19

to go into the legal market and purchase the services of the

most competent and qualified attorney to redress that vio

lation, in the same manner as a corporation or commercial

enterprise can go into the legal market and purchase attorney

services to vindicate its legal rights. If a civil rights

attorney has the same experience and expertise in the civil

rights area as a corporate or commercial attorney has in the

corporate or commercial area, the services of the civil

rights attorney are deemed to have the same market value as

the services of the corporate or commercial attorney and must

be compensated on the same basis.

So too, under the Northcross approach — which in this

regard is particularly related to the purpose of the federal

fee award statutes — counsel for the plaintiffs in civil

rights actions are to be encouraged to do everything possible

to vindicate the federally protected rights of their clients,

just as other attorneys are encouraged — by the prospect of

being paid the market value of their services — to do every

thing possible to vindicate the rights of their clients. "In

computing the fee, counsel for prevailing parties should be

paid, as is traditional with attorneys compensated by a fee

paying client, 'for all time reasonably expended on a

matter.'" S. Rep. No. 94-1011, at 6. Civil rights attorneys

20

are to be encouraged to work on each aspect of the case as

thoroughly and diligently as they would if the case involved

the interests of a corporate or commercial client. They are

to be encouraged to pursue every line of inquiry and to

engage in "innovative and vigorous lawyering in a changing

area of the law," and to "take the most advantageous position

on their clients' behalf that is possible in good faith."

Northcross at 636. They are to be encouraged to take the

same team approach to complex litigation involving civil

rights as a "high-powered" law firm would take to complex

litigation involving the antitrust laws or corporate control.

There cannot, consistent with the purpose of the federal fee

award statutes, be any notion that a civil rights case is

"not worth that much," or that a civil rights case must be

"litigated on the cheap." See Harkless v. Sweeney

Independent School District, 608 F.2d 594, 597-598 (5th Cir.

1979). It is these objectives that the Northcross approach

seeks to accomplish by providing that the attorney shall be

compensated for the market value of the attorney's services.

The actions of the District Court that are challenged

on the present appeal strike at the heart of the Northcross

approach and deny compensation to the applicants in accordance

with the fair market value of their services, thus undermining

the fundamental purpose and underlying policies of the

statutes providing for awards of counsel fees in civil rights

21

cases. Each of these actions of the District Court will be

specifically addressed in the following sections of this

brief.

II.

The District Court Erred in Entering an Award of

Attorneys' Fees in 1981 for Services Performed in

the Period 1974-1979, on the Basis of the Value of

Attorney Services at the Time They Were Performed

Without Adjusting the Award for the Effect of

Inflation.

In the Court below, there initially was no dispute

between the parties that the award had to be adjusted by

some method to compensate the applicants for the effect of

inflation. The applicants contended that the award should be

based on the market value of the attorney services at the

time the services were rendered, and that the award should be

adjusted for inflation directly according to the Consumer

Price Index. (App. 65, 277-81). The City's position in this

regard was as follows:

"While the Court in Northcross did authorize

a consideration of inflation in determining the

reasonableness of the fee awarded, it did not specify

the method of this consideration. The Court did

approve, however, the standard method used by the

federal courts of setting a single hourly rate based

upon a reasonable rate at the time of the award . . .

"Only if the hourly rate set at the time of

award is not sufficient to balance the lower rate which

prevailed at the time the services were provided should

22

an adjustment for inflation be made.

"Defendants submit that an hourly rate

based on hourly rates prevailing at the present

time will adequately compensate for inflation

since 1974 and no additional adjustment is

warranted." (App. 226) (emphasis added).

On this issue, the District Court gave the City more than it

asked for: The Court determined the value of attorney ser-

ices at the time the services were rendered and refused

to make any adjustment at all for inflation. (App. 337,

432) .

The District Court took the position that it had the

discretion to refuse to adjust the award for the effect of

inflation, and that Northcross merely authorized, but did11/not require, such an adjustment. (App. 432). It then ex

ercised that "discretion" against making an adjustment, be

cause the services in the present case had been performed "only"

two to seven years prior to the award and because "substan

tial delay in the instant case resulted from actions of the

12/plaintiffs' attorneys." (App. 432-33). The applicants

11/ In responding to the applicants' motion to alter or

amend the judgment, the City revised its position and supported

the District Court's view. (Memorandum of Law in Support of

Defendants' Response to Motion To Amend Findings of Fact,

Conclusions of Law, and To Alter or Amend Final Judgment, at

1-2 ).

12/ In its original memorandum opinion, the District Court

said that "long periods of time ensued between the trial of

the action and final decision of the Court due, in considerable

measure, to the parties' desire for extensions of time in

which to file briefs." (App. 337-38). In its order overruling

the motion to amend, however, it put the blame entirely on

the plaintiffs' attorneys. (App. 433).

23

submit that the District Court does not have such "discretion"

under Northcross; to the contrary, an adjustment must be

made for the effect of inflation, either directly, as

proposed by the applicants, or by basing the award for past

services on the present value of the attorneys' services.

Moreover, as set forth below, there is no basis in the

record for the District Court's finding that plaintiffs'

counsel were responsible for "substantial delay." See pp.

29—31, infra.

In Northcross this Court, referring to an award of

attorneys' fees for services performed prior to 1977,

stated:

". . . . the district court will be required to

consider whether the inflation of the intervening years

must be taken into account, or whether the lower rate

which prevailed for services at the time they were

rendered has been balanced by the long delay which will

reduce the purchasing power of the award's dollars in

the present marketplace." Northcross at 640.

In that case the District Court had made the award on the

basis of the 1977 value of the attorney services, notwith

standing that the attorneys sought recovery for services

dating back to 1960, when the suit was first filed. See

Northcross at 641. The question that the District Court was

directed to consider was whether an additional adiustment

was necessary because of the inflation which had occurred

between the time the services were performed and the time

the award was rendered, during which time the attorneys had

received no money whatsoever. If an additional adjustment

24

for inflation was not necessary, it was because the attorneys

were being compensated at 1977 rates for services which had less

value (both in terms of lesser attorney experience and in terms

of lower prevailing rates) at the time they were performed. But

one way or another, some adjustment for the effect of inflation

on the purchasing power of the award would be made.

In the present case, the award rendered in 1981 was

for services performed from 1974 to 1979. Unlike the award

made by the District Court in Northcross, which was based on

the 1977 value of attorney services, the award in the present

case was based on the lower value of attorney services (both

in terms of lesser attorney experience and in terms of lower

prevailing rates) at the time the services were performed,

iand there was no adjustment at all for inflation. The appli

cants, then, got the worst of both worlds. The award was

based on the value of attorney services as calculated in 1974,

1975, and so forth, but the money was not received until 1981,

and the inflation of the intervening years was not taken into

account. The long delay between the time the services were

performed and the time the award was made most assuredly "will

reduce the purchasing power of the award's dollars in the present

marketplace." Northcross at 640. Thus, the applicants are not-

recovering the fair market value of their services, as required

25

13/by Northcross.

The District Court, failing to relate this Court's discus

sion of the matter of adjusting the award for inflation in

Northcross to the Northcross approach of basing the award

on the fair market value of the attorney's services, attempted

instead to distinguish Northcross on its particular facts.

The District Court stated:

"We find no indication that Northcross gives

the District Court the 'either-or' alternative of

adding an inflation factor into attorney fee

awards, or granting fees based on the present

value of comparable work by the same attorneys.

While we do not doubt that Northcross authorizes

either such course, there is some distance

between authorization and requirement, and we

found in our memorandum opinion of February 12,

1981 that the Louisville Black Police attorneys

have been fairly and adequately compensated

without the addition of an inflation factor or the

use of a present-value based calculation. We

distinguish Northcross from the instant case in

that the passage of time in Northcross had been

13/ The following chart illustrates the eroding effects of

inflation on the purchasing power of a rate of $50 an hour

awarded in 1980 for

1979, based on the

U.S. Department of

App. 201-02, 271-81

services performed between 1974 and

Consumer Price Index as calculated by the

Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (see

, 316-20).

Year Services Performed Consumer Price Index

Purchasing Power

of $50 Awarded

in 1980

Decline in Purchasing

Power

1979 217.7 $42.49 15.0%

1978 195.3 $38.11 23.8%

1977 181.5 $35.42 29.2%

1976 170.5 $33.27 33.5%

1975 161.2 $31.46 37.1%

1974 147.7 $28.83 42.3%

26

much greater between the performance of much of the

work involved and the ultimate entry of the order

awarding attorney fees, and the fact that sub

stantial delay in the instant case resulted from

actions of the plaintiffs' attorneys." (App. 432-33).

What the District Court ignored, of course, was the

relationship between an adjustment for inflation and recovery

of the fair market value of attorney services, as mandated

by the Northcross approach. Because of the "reduction of the

purchasing power of the award's dollars in the present market

place" due to the effects of inflaction, the present applicants

will not in fact recover the fair market value of their services

unless an adjustment is made for inflation. In the absence

of such an adjustment, contrary to the assertion of the District

Court, attorneys cannot be "fairly and adequately compensated"

when there is a delay of some years between the time the services

were performed and the time the attorneys receive compensation

for those services.

The District Court's attempt to distinguish Northcross

on its particular facts does not undercut the rationale of

Northcross with respect to the required adjustment for in

flation. Even if Northcross properly could be so distinguished

— which, as will be demonstrated, it cannot — the rationale

of Northcross is applicable to any award of attorneys' fees

that is made some years after the services were performed.

That rationale does not depend on the degree of inflation

during the intervening years or on the reasons for the lapse

of time between the performance of the services and the issuance

of the fee award. Rather, it is based on the guiding principle

27

of Northcross: that attorneys should be compensated for the

fair market value of their services. Where there has been a

substantial delay between the performance of the services and

the award of compensation, the attorneys will not receive the

fair market value of their services unless an adjustment is

made for the effect of inflation.

Not only was this Court's decision in Northcross not

based on the particular facts of that case, but there are no

factual distinctions between Northcross and the present case

which would justify the refusal of the District Court to

adjust for inflation here. While the passage of time between

the performance of the services and the rendition of the

award in Northcross may have been greater than in the present

case, double-digit inflation is a product of the 1970's, and

it has continued into the 1980's. Thus, the greater extent

of the inflation of the intervening years in the present case

counterbalances the longer delay between the performance of

the services and the rendition of the award in Northcross.

The Consumer Price Index, based on a scale of 100 in 1967,

increased from 147.7 in 1974 to 256.2 in November, 1980. In

other words, the 1967-based consumer dollar was worth 67.8

cents in 1974; by November, 1980, its value had declined to

14/39 cents. (App. 281). In the present case, therefore,

14/ Thus, a 1980 dollar would buy only as many goods and

services as 58 cents bought in 1974. Stated another way, it

took $1.74 in 1980 terms to equal the purchasing power of

$1.00 in 1974 terms. By July 1981, the most recent date for

which figures were available at the time this brief was

written, the Consumer Price Index had risen to 274.4. N . Y.

Times, Aug. 26, 1981, at A1, col. 6. Thus, it now takes

28

-just as in Northcross, the applicants will be seriously undercom-11/pensated if the award is not adjusted for inflation.

Secondly, even if an adjustment for inflation could be

disallowed because of "responsibility for delay" — which,

under the Northcross approach, it cannot — the District Court

could not properly refuse to adjust for inflation on the ground

that "substantial delay in the instant case resulted from actions

of the plaintiffs' attorneys." (App. 433). As the District

Court acknowledged, this was not a simple case. (App. 335). A

five to six year period between the filing of such a suit and its

favorable resolution for the plaintiffs is not at all uncommon in

complex civil rights cases. Extensive discovery was necessary

before the plaintiffs could begin to develop their case. A

persual of the docket entries (App. 1-27) demonstrates the

14/ Continued

$1.86 in 1981 terms to equal the purchasing power of $1.00

in 1974 terms. A detailed description of the method of

calculating an inflation factor based on the Consumer Price

Index for each year is contained in the Appendix. (App. 279-

81, 316-20). The CPI inflation factors for each year from

1974 through 1979, based on the CPI for November, 1980, are

set forth in Addendum A to this brief.

15/ For example, the District Court set Mr. Allison's rate at

$50 an hour in 1981 dollars for services he performed in 1974.

In order to adjust for the effects of inflation up to November

1980, this rate must be multiplied by a factor of 1.738. See

Addendum A. Thus, a rate of $50 an hour in 1974 dollars is

equivalent in purchasing power to a rate of $87 an hour in

1980 dollars. Conversely, a rate of $50 an hour in 1980 dollars

is worth only $29 in 1974 dollars. By awarding Mr. Allison a

rate of only $50 an hour in 1981 for services he performed in

1974, and by refusing to make any adjustment for the effects

of inflation, the District Court cut the purchasing power of

this part of his award by more than 40 percent . See n.13,

supra.

29

extensive nature of the discovery conducted by all parties and

the multifaceted nature of the proceedings. Insofar as there

were requests for extensions of time, particularly between

the trial of the action and the decision of the District Court on

the merits, the requests were made by both parties, as the

District Court recognized. (App. 337-38). Approximately 20

months elapsed between the completion of the trial of the

case in September, 1977, and the filing of all post-trial

briefs and reply briefs by the parties. The first eight months

were taken up with transcriptions of the trial testimony.

After the transcript was completed in May, 1978, the parties

attempted to negotiate a settlement, but were unable to do

so, and counsel for the plaintiffs filed their post-trial

brief and proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law

in September, 1978. The City thereafter retained a Washington,

D.C., firm to represent it, and was granted a series of exten

sions amounting to more than 3 months beyond the original period

of 60 days within which it was to file its post-trial brief.

On February 20, 1979, the City submitted its 176-page proposed

findings of fact and conclusions of law and its 94-page post-trial

brief. The intervening defendants also submitted a 90-page

post-trial brief and proposed findings and conclusions. After

being granted extensions of less than a month, counsel for the

plaintiffs served their post-trial reply brief on May 18, 1979.

Thus, the record simply will not support the District

Court's conclusion that "substantial delay in the instant

30

The plaintiffs' attorneys prosecuted the case on behalf of

their clients thoroughly and carefully, and as diligently as

they could in light of the complexity of the case, the determined

opposition of both the defendants and the intervening defendants,

and the multifaceted nature of the proceedings. Extensions

of time were requested by both sides and were granted by the

District Court. In Northcross, there were delays of up to

two years from one phase of the case to another, Northcross

at 628-629, but this was not considered sufficient to justify

a refusal to adjust the award for the effects of inflation.

The opinion of this Court in Northcross is not alone

in recognizing the need to take inflation into account in

awarding fees for services performed in past years. Many

reported fee decisions in prolonged and complex federal litiga

tion — including fee awards in antitrust and securities cases,

applying the same standards which are to govern fee awards in

civil rights cases (see Northcross at 633) — simply award

current rates without discussion of the inflation problem. See,

e.g., Harkless v. Sweeney Independent School District, 466 F.

Supp. 457 (S.D. Tex. 1978), aff*d, 608 F.2d 594 (5th Cir. 1979).

The courts which have expressly addressed the impact of inflation

have employed various methods to compensate counsel for the loss

16/

resulting from delay in payment. As the D.C. Circuit

case resulted from actions of the plaintiffs' attorneys."

16/ See, e.g., Vecchione v. Wohlgemuth, 481 F. Supp. 776,

795 (E.D. Pa. 1979) (upward adjustment of base fee "to compensate

counsel for the delay in recovery of their fee"); Aamco

31

stated in a recent eri banc opinion,

". . . payment today for services

rendered long in the past deprives the

eventual recipient of the value of the

use of the money in the meantime, which

use, particularly in an inflationary

era, is valuable. A percentage

adjustment to reflect the delay in

receipt of payment therefore may be

appropriate . . . . 23/

[Footnote 23] " On the other hand,

if the 'lodestar' itself is based on

present hourly rates, rather than the

lesser rates applicable to the time

period in which the services were

rendered, the harm resulting from delay

in payment may be largely reduced or eliminated." Copeland v. Marshall, 641

F.2d 880, 893 and n. 23 (D.C. Cir. 1980)

(en banc) (emphasis in original).

A recent wide-ranging study of counsel fee awards in

class actions, commissioned by the Federal Judicial Center,

has confirmed the principle expressed in Northcross and

other decisions that the effect of inflation ordinarily

should be taken into account in awarding fees. A. Miller,

Attorneys' Fees in Class Actions, at 362-364 (Federal Judicial

Center 1980). This study includes a thorough review of the

case law, id. at 363 nn. 30-31, and it concludes in pertinent

part that:

16/ Continued

Automatic Transmissions, Inc, v. Tayloe, 82 F.R.D. 405 (E.D.Pa.

1979) (similar); Knutson v. Daily Review, Inc., 479 F. Supp.

1263, 1277 (N.D. Cal. 1979) (similar); Lockheed Minority

Solidarity Coalition v. Lockheed Missiles, 406 F. Supp.

828, 834-35 (N.D. Cal. 1976); In re Ampicillin Antitrust

Litigation, 81 F.R.D. 395, 402 (D.D.C. 1978) (inflation

accounted for by application of current rates); McPherson v.

School Dist. No. 186, 465 F. Supp. 749, 760 (S.D. 111. 1978)

(school desegregation case; same).

32

"Fee awards should include some

compensation for the costs of delay in

receiving the fee award. This can be

accomplished through application of

discounted current rates or through use

of historic rates adjusted for,7/

inflation." Id. at 362-363. — •

The applicants in the present case, no less than the

attorneys for the plaintiffs in Northcross and the other

cases cited above, are entitled to recover the fair market

value of the services they performed in vindicating federally-

protected rights. As these courts have recognized, and as

the recent Federal Judicial Center study has confirmed,

plaintiffs' counsel will not recover the fair market value

of their services unless the award is adjusted for inflation.

The applicants submit that the most appropriate way to adjust

for the effects of the inflation is to do so directly by

awarding the value of the services at the time they were

performed and adjusting the award for inflation according to

the Consumer Price Index. See App. 279-81. Basing the award

on the value of attorney services at the time of the award

17/ The study further found that, "[i]n addition to adjusting

the fee for inflation to take into account the declining

value of the dollar, many courts also order an award of

interest to pay for the loss of the use of those dollars

between the time the work is performed and the time the fee

is finally paid. Such orders are within the proper scope of

the court's discretion and are not inappropriate, especially

in the longer cases." Attorneys' Fees in Class Actions, at

364. (The applicants did not request an award of pre-judgment

interest in the present case.) The study also concluded that, if

current rates are used, they should be discounted to take into

account the lower costs incurred at historic rates as well as

any increase in rates attributable to professional growth rather

than inflation. Id. at 363-364.

33

may be a "rough and ready" way of accomplishing the same

objective. See Addendum A. But the award must be adjusted

for the effects of inflation, and the adamant refusal of the

District Court to do so in the present case was clear error.

III.

The District Court Erred in Refusing to Award Attorneys'

Fees for the Services Performed by NAACP Legal Defense

Fund Attorneys on the Basis of the Reasonable Value of

Those Services, Taking into Account the Fund's

Institutional Reputation and Expertise, the Background

and Experience of Its Attorneys, and the Customary

Rates Charged by Comparable Attorneys and Law Firms for

Similar Services.

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund is a "nonprofit organization

dedicated to the vindication of the legal rights of blacks

and other citizens." Gulf Oil Co. v. Bernard, ____U.S. _____,

101 S. Ct. 2193, 2199 n. 11 (1981). The Legal Defense Fund,

like the NAACP by which it was founded, has played a unique

role in the struggle for racial equality in this Nation.

That role, particularly in sponsoring and developing civil

rights litigation, has long been recognized by the courts.

The Legal Defense Fund has been cited by the Supreme Court

as having a "corporate reputation for expertness in presenting

and arguing the difficult questions of law that frequently

arise in civil rights litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.

415, 422 (1963). Precisely because the Fund has long been

involved in civil rights cases, it has acquired an institutional

expertise that makes the time of its attorneys necessarily more

34

valuable than the time of most private attorneys providing

representation in such cases. This point was specifically

recognized by this Court in Northcross. As it stated:

"The services provided by the Legal Defense Fund

clearly had to be provided by someone, and in fact, the

attorneys' intimate familiarity with the issues involved

in desegregation litigation undoubtedly meant that their

time was far more productive in this area than would be

that of a local attorney with less expertise."

Northcross at 637.

The Legal Defense Fund has the same "intimate familiarity"

with the issues involved in employment discrimination litigation,

and as set forth in the affidavit of Mr. Allison (App. 361), the

local attorneys believed that the Fund's participation in

the present litigation was absolutely necessary to its successful

prosecution. The uncontroverted affidavits of Mr. Allison

(App. 360-62) and Mr. Patterson (App. 364-69) set forth in detail

the crucial role played by the Legal Defense Fund in the

litigation of this case. After entering the case in 1976,

the LDF attorneys, Mr. Patterson and Ms. Greenberg, assumed

the role of lead counsel with respect to several major aspects

of the litigation. Mr. Patterson was responsible for overall

strategy; he generally determined, in consultation with the

other attorneys, what testimony and documentary evidence

would be needed at trial; he advised the Louisville attorneys

on numerous questions of law; he functioned as lead counsel

in conducting legal research and writing motions and legal

memoranda; he was in change of the research and writing of

the plaintiffs' post-trial briefs. (App. 365-66). Until her

departure from the Fund in June, 1977, Ms. Greenberg served

35

as lead counsel with respect to the issues of testing and

test validation. Thereafter Mr. Patterson assumed full respon

sibility as lead counsel on these issues. (App. 366). As Mr.

Allison stated in his affidavit, his office had never before

handled such a complex class action. The experience and

expertise of the Legal Defense Fund attorneys in the special

ized field of employment discrimination law "were invaluable

and caused hundreds of fewer hours to be spent in trial

preparation." (App. 361). Moreover, "[b]ecause of LDF's

experience in these types of cases and familiarity with the

law in this area, less time was actually spent replying

to legal challenges by the defendants and [in] the writing of

briefs." (App. 361).

The rates which the District Court found to be the

prevailing hourly rates for attorneys practicing in the City

of Louisville seriously undervalue the services provided by

the Legal Defense Fund staff attorneys. By limiting the

award to prevailing hourly rates for attorneys engaged in

private practice in Louisville, the District Court completely

ignored the fact that the Legal Defense Fund staff attorneys

were not conventional private practititioners, but staff

attorneys of an organization that has a "corporate reputation

for expertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions

of law that frequently arise in civil rights litigation."

NAACP v. Button, supra. In the present case, it was not

merely the services of the staff attorneys that were available

36

to the plaintiffs, but also the institutional resources of

the Legal Defense Fund.

As staff attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund, Mr. Patterson

and Ms. Greenberg received training and experience in litigating

civil rights cases that simply could not be available to lawyers

who were engaged in private practice. Their uncontroverted

18/ 19/

affidavits establish that Mr. Patterson and Ms. Greenberg

are both highly qualified and experienced specialists in litigat

ing employment discrimination cases. Moreover, the institu

tional expertise and experience of the Legal Defense Fund,

derived from being in the forefront of civil rights litigation in

this Nation for over four decades, came with the staff attorneys

assigned to this case, and those attorneys drew on this institu-

18/ Since his graduation with honors from Columbia Law

School in 1972, Mr. Patterson has continuously specialized

in the field of employment discrimination law. He taught a

clinical course in fair employment law at the University of

Wisconsin Law School. He has lectured at conferences and

training programs on employment discrimination litigation

and related topics. Both before and since joining the staff

of the Legal Defense Fund in 1976, he has had major or

principal responsibility for the trial and appellate litiga

tion of many employment discrimination class actions. (App.

70-74).

19/ Ms. Greenberg graduated from Columbia Law School in

1957. While on the staff of the Legal Defense Fund from 1972 to

1977, she specialized in employment discrimination litigation

and was involved in at least 30 employment discrimination

class actions at the trial and appellate levels. As a lecturer

at Columbia Law School, she conducted a clinical seminar in

public interest litigation. She has also lectured at a number of

other law schools, conferences, and courses on such topics as

employment testing, affirmative action, discovery techniques,

class actions and legal ethics. She is a past or present member

of a number of bar association committees and other organizations

specializing in civil rights and equal employment opportunity law.

(App. 171-74).

37

20/

tional expertise and experience throughout the litigation.

Since this is so, the fair market value of the services furnished

by staff attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund necessarily must

include the value of the institutional expertise and resources of

the Fund itself.

In rejecting this principle, the District Court stated:

"We see nothing in Northcross which requires that attorneys

of a particular organization be accorded fees higher than

their other qualifications would suggest to be warranted, on

the assumption that their employment by that organization

presumptively makes them superior to other able attorneys

who specialize in the same area of law." (App. 433). However,

as Mr. Allison's affidavit made clear, he and the plaintiffs'

other Louisville attorneys were not "specialists" in the same

sense as the Legal Defense Fund attorneys. Indeed, his

office "had never before handled a complex class action law

suit of this nature." (App. 361).

As this Court specifically stated in Northcross, "the [Legal

Defense Fund] attorneys' intimate familiarity with the issues

involved in desegregation litigation undoubtedly meant that their

time was far more productive in this area than would be that of a

local attorney with less expertise." Northcross at 637. The

greater expertise of the Legal Defense Fund staff attorneys comes

not only from their personal qualifications and experience

20/ Other Legal Defense Fund attorneys reviewed documents

and conferred with the staff attorneys assigned to the case,

but no compensation was claimed for their services. (App. 72-73,

366-67) .

38

and their internal specialization at the Fund, but also from

the institutional expertise of the Fund itself and from the

institutional resources of the Fund that are made available

in any litigation in which the Fund participates. Lawyers

in private practice do not generally specialize in civil rights

21/law, but even if they did, they could not acquire the

institutional expertise of the Legal Defense Fund, which has

resulted from its being for so long in the forefront of the

struggle for racial equality in this Nation. The attorneys' fees

award goes to the Legal Defense Fund, not to the individual

attorneys, and the award therefore must be based on the reason

able value of the total services furnished by the Legal Defense

Fund, including the Fund's institutional expertise and resources.

Totally apart from the fact that the District Court

erred in failing to take into account the specialized qualifications

of the Legal Defense Fund attorneys in this case, their

leading role in the litigation, and the Fund's institutional

expertise and resources in determining the fair market value

of the services they furnished, the District Court further

erred in looking to a "local market" rather than to the

"national market" in determining the fair market value of

21/ This is in large part because prior to the advent of

the federal civil rights attorneys' fees statutes, compensa

tion generally was not available to lawyers who represented victims of civil rights violations. "The entire purpose of

the statutes was to ensure that the representation of

important national concerns would not depend upon the

charitable instincts of a few generous attorneys." Northcross

at 638.

39

those services. The relevant "market" for purposes of determin

ing the fair market value of services provided by a particular

attorney or law firm necessarily must be the "market" in which

the particular attorney or law firm practices. If a New York law

firm, specializing in antitrust matters and operating in the

"national market," successfully represented a plaintiff in

an antitrust action in Louisville, it would be compensated

on the basis of the rates it normally charges, not on the basis

of prevailing Louisville rates for other kinds of litigation.

For the same reason, the Legal Defense Fund, which operates in

the "national market" to vindicate federally-protected civil

rights, should be compensated according to the fair market value

of its services in the national market in which it operates, not

on the basis of prevailing Louisville rates. As this Court noted

in Northcross, Congress determined that the amount of fees to be

awarded under the Fees Act should be governed by the same stan

dards which prevail in other types of equally complex Federal

litigation, such as antitrust cases," and should not be reduced

because the rights involved may be nonpecuniary in nature. 611

F.2d at 633, quoting S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 6

(1976). See also H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 9

(1976) ("civil rights plaintiffs should not be singled out for

different and less favorable treatment"). Since national law

firms which successfully represent plaintiffs in antitrust and

securities actions are not required to "discount" the value of

their services in accordance with prevailing local rates, the

functional equivalents of such national law firms, such as the

- 40 -

Legal Defense Fund, which successfully represent plaintiffs in

civil rights actions on a nationwide basis, likewise should

not be required to "discount" the value of their services,

and should be entitled to recover the fair market value of their

services based on the rates that prevail in the "national market"

in which they operate.

Plaintiffs in civil rights cases, like plaintiffs in antitrust

cases, cannot be limited to their local area in obtaining legal

representation, but are entitled to be represented by the func

tional equivalent of national law firms with special expertise in

such cases. In enacting the fee award statutes, Congress intended

to give the victims of civil rights violations the best possible

representation they could obtain. In order to effectuate the intent

of Congress, the attorneys and organizations that provide such

representation must be compensated at rates which take into account

the nature and location of their practice, their reputation and

expertise, and the prevailing rates charged by comparable firms for

comparable services.

The Federal Judicial Center's recent study of counsel

fee awards includes detailed consideration of the problems

raised by the existence of varying rates for legal services

throughout the country. The study found in part that,

". . . if the schedule for the community where

the litigation takes place is chosen, some attorneys may be compensated

at rates much higher or lower than they

normally would command. This system

might contribute to inequities in the

availability of high quality legal

services. For example, an experienced

41

and successful attorney from a major

urban area might be unwilling to take a

case in a rural community if he or she knew

the rate of compensation would be much

lower than what could be earned at

home . . . A. Miller, Attorneys'

Fees in Class Actions, at 365-366

(Federal Judicial Center 1980) (footnote

omitted).

This is precisely what happened in the present case: the

services of specialized staff attorneys from the Legal Defense

Fund's New York City office were compensated at far lower