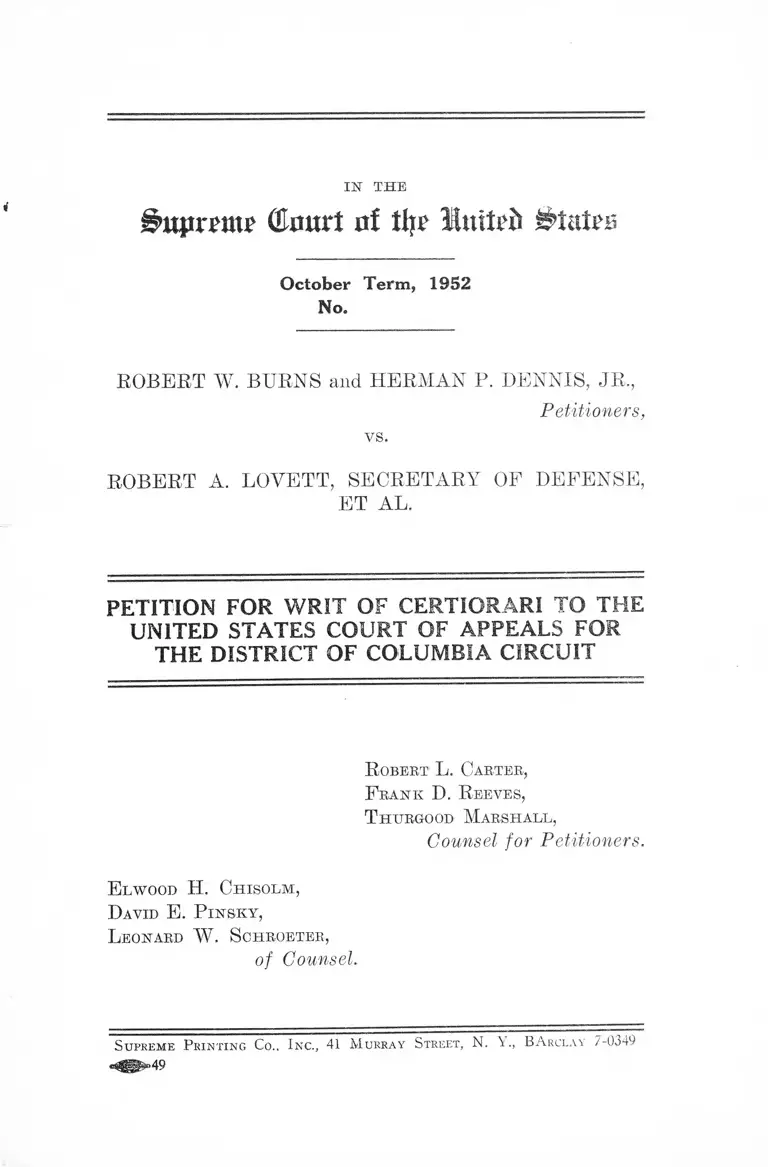

Burns v Lovett Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1952

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burns v Lovett Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals, 1952. 1bad1e19-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fbde368f-7306-432d-bbdc-0816e36d9373/burns-v-lovett-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

(Hour! rtf tljr luttr^ States

October Term, 1952

No.

EGBERT W. BURNS and HERMAN P. DENNIS, JR.,

Petitioners,

vs.

ROBERT A. LOVETT, SECRETARY OF DEFENSE,

ET AL.

PETITION FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COU RT OF APPEALS FOR

THE DISTRICT OF COLUM BIA CIRCUIT

R obert L. Carter,

F rank D. R eeves,

T httrgood M arshall ,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H. Ch iso lm ,

D avid E . P in s k y ,

L eonard W . S chroeter,

of Counsel.

S upreme P rin tin g Co., I nc ., 41 M urray S treet, N. B A rcla 'i 7-0349

<4@ M 9

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion Below ................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction.......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ......................................................... 2

Statutes Involved .................................................... 2

Statement............................................................................. 3

Specifications of Error ................................................. 5

Reasons for Allowance of tlie Writ ............................. 6

Conclusion .......................................................................... 26

Appendix ............................................................................ 27

Table of Cases Cited

Anderson v. United States, 318 U. S. 350 .................. 14, 24

Becker v. Webster, 171 F. 2d 762 (C. A. 2d 1949) . . . . 9

Belirens v. Hironimus, 166 F. 2d 245 (C. A. 4th 1948) 7

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 ............................. 12

Darr v. Burford, 339 U. S. 200 ..................................... 22

De War v. Hunter, 170 F. 2d 993 (C. A. 10th 1948),

cert. den. 337 U. S. 908 ............................................. 19,19

Ex parte Hawk, 321 U. S. 1 1 4 ........................... 19, 20, 21, 22

Ex parte Lange, 18 Wall 1 6 3 ....................................... 6

Ex parte Milligan, 71 U. S. 2 .....................................

Ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1...................................... 9

Ex parte Royall, 117 U. S. 2 4 1 ..................................... 6

Ex parte Siebold, 100 U. S. 3 7 1 ................................... 9

PAGE

11

PAGE

Gallegos v. Nebraska, 342 U. S. 55 . . . |....................... 14, 24

Gambino v. United States, 275 U. S. 3 1 0 ............14, 24, 25

Ganlt v. Burford, 173 F. 2d 813 (C. A. 10th 1949) .. 20

Goodwyn v. Smith, 181 F. 2d 498 (C. A. 4th 1950) .. 20

Graham v. Squier, 132 F. 2d 681 (C. A. 9th 1942) .. 7

Gusik v. Sehilder, 340 U. S. 1 2 8 ................................. 19fn.

Hiatt v. Brown, 339 U. S. 103 ....................................... 8,17

Hicks v. Hiatt, 64 F. Supp. 238 (M. D. Pa,, 1946)___ 24

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 4 2 ......................................... 11

Humphrey v. Smith, 336 U. S. 695 ............................ 8

In re Wrublewski, 71 F. Supp. 143 (N. D. Cal. 1947) 9

Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U. S. 763 ........................ 9

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 ................................. 7, 8,18

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 2 1 9 ........................... 7,13

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401 .................... 13

McClaugkry v. Deming, 186 U. S. 4 9 ......................... 23

McNabb v. United States, 318 U. S. 332 ..................... 24

Mooney v. Holonan, 294 U. S. 1 0 3 ..................... 7,14,15,16

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 8 6 ............................... 7,18, 21

Pyle v. Kansas, 317 U. S. 2 1 3 ................................. 14,15,16

Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 1 6 5 ............................. 13

Schita v. King, 133 F. 2d 283 (C. A. 8th 1943).......... 10

Sunal v. Large, 332 U. S. 1 7 4 ....................................... 7

United States v. Baldi, 192 F. 2d 540 (C. A. 3rd 1951),

cert, grant. 343 U. S. 403 ........................................... 20, 21

United States v. Crystal, 131 F. 2d 576 (C. A. 2d

1943), cert. den. 319 U. S. 755 ................................... 9

United States v. Grimley, 137 U. S. 1 47 ..................... 6

United States v. Hiatt, 141 F. 2d 644 (C. A. 3d 1944) 10

United States v. Swenson, 165 F. 2d 756 (C. A. 2d

1948) ............................................................................ 9

I l l

Wade v. Hunter, 336 U. S. 684 ................................... 8

Waite v. Overlade, 164 F. 2d 722 (C. A. 7th 1947),

cert. den. 334 U. S. 8 1 2 ................................. ........... 10

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101 ............................... 7, 8,18

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275 ............................. 11

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 ..................................... 13

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 4 9 ..................................... 12

Weeks v. United States, 232 U. S. 358 ..................... 24

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530 ..................................... 13

Whelchel v. McDonald, 340 U. S. 122 ........................... 8

Wrublewski v. Mclnerney, 166 F. 2d 243 (C. A. 9th

1948).............................................................................. 9

PAGE

Statutes Cited

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1488 ............... 2

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1495 ............... 2

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1542 ............... 2

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2254 .............. 20

Penal Code of Guam:

Section 27 ................................................................ 27

Section 686 ............................................................ 2,12, 24

Section 780 ............................................................. 2,12,24

Section 825 ............................................................. 2,12,24

IV

Other Authorities

PAGE

Hearings Before Sub-Committee of the Committee

on Armed Services on S. 857 and H. R. 4080, United

States Senate, 81st Congress, 1st Session (1949) 22

Report of the War D ep’t. Advisory Committee on

Military Justice (1946) ............................................. 23

Farmer and Wells, Command Control—or Military

Justice, 24 N. Y. U. L. Q. Rev. 263 (1949 ).............. 22

35 Cornell L. Q. 15 (1949) ........................................... 22

2 Stanford L. Rev. 547 (1949) ..................................... 22

IN THE

§>upnw Court of tljr llnxtib States

October Term, 1952

No.

---------------------- o----------------------

R obert W . B urns and H erman P . D en n is , J r .,

Petitioners,

vs.

R obert A. L ovett, S ecretary of D efense, Et A l.

— -------------------------- o-----------------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Robert W. Burns and Herman P. Dennis,

Jr., pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judg

ment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Dis

trict of Columbia Circuit entered in the above-entitled case

on July 31, 1952.

Opinion Below

The memorandum opinions of the United States Dis

trict Court for the District of Columbia are reported at

104 F. Supp. 310, 312 (R. 18). The opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia is not yet reported

(R. 21).

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

on July 31, 1952 (R. 57). The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under Title 28, United States Code, Section

1251(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether an American citizen solider, after trial and

conviction by military authorities, may obtain a review

of the court-martial conviction in a civil court by habeas

corpus where the military proceedings, as a totality, show

a complete absence of that fundamental fairness essential

to a fair trial under Anglo-American jurisprudence.

2. Whether on the basis of allegations averring flagrant

denials of fundamental rights, which in the present posture

of these cases are admitted as true, petitioners are entitled

to a hearing on the merits and to an independent determina

tion by a civil court as to whether their military trials and

convictions violated constitutional due process.

3. Whether these courts-martial were ousted of juris

diction by the admission of damaging evidence against peti

tioners when such evidence had been illegally extracted by

federal civil authorities while they held petitioners in

custody.

Statutes Involved

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1488

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1495

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1542

Sections 686, 780, 825 of the Penal Code of Guam

These are set out in the Appendix

3

Statement

Petitioners, who are citizens of the United States and

members of the United States Air Force, are individually

seeking petitions for writs of habeas corpus to secure their

release from military custody. One petition is being filed for

both petitioners since the issues raised in each case are the

same. They are now being detained by the Japan Logistical

Command and are awaiting execution of sentences of death

pursuant to convictions by general courts-martial of the

United States Air Force for the murder and rape of Buth

Farnsworth, a civilian employee on the Island of Guam.

The crime took place on or about December 11,1948 (E. 1-2).

On January 7, 1949, petitioners, who were stationed on

Guam, an insular possession of the United States and at

that time under the civil administration of the United

States Navy, were surrendered by the military authorities

to the civil police authorities (E. 2-3). The civil authorities

took them into custody and held them incommunicado with

out process (E. 3). They were subjected to continuous

questioning (E. 3), beaten (E. 3), denied sleep and edible

food (E. 3) and were not allowed to consult counsel during

the entire time they were held in custody (E. 3). Herman.

P. Dennis, Jr., was subjected to a lie detector test and held

in solitary confinement (E. 11), and Bobert W. Burns was

placed in a death cell (E. 3). Petitioner Dennis had certain

pubic hairs taken from his person without being advised

of his rights against self-incrimination, and these specimens

were subsequently used in evidence against him (E. 12).

As a result of coercion, threats and promises, after being

told what to say by police officers and without being advised

of his rights, he made four confessions on or about Janu

ary 11, 12 and 13, implicating himself in the crime for

which he was subsequently charged (E. 11).

On or about January 30, 1949, the civil authorities re

turned petitioners to the custody of the United States Air

Force (E. 3). On February 1, 1949 (E. 11) and on Febru

ary 20, 1949 (E. 3) charges were filed against Dennis and

4

Burns respectively, and they were separately tried and con

victed by military courts-martial (R. 3). Their trials were

conducted in an atmosphere of hysteria and terror created

by both the military and civil authorities on Guam (R. 4).

In this connection it should be pointed out that petitioners

are Negroes and Ruth Farnsworth was white.

The request of petitioner Dennis for counsel of his

choice was denied (R. 12). Defense attorneys were not

appointed for him until April 8, 1949, and he did not have

the opportunity to receive the advice of counsel until

shortly before his trial convened on May 9, 1949 (R. 13).

At his trial, the involuntary confessions made by him to

the civil authorities were received in evidence despite his

repudiation of them and testimony as to their involuntary

character (R. 12). Evidence tending to show his inno

cence was suppressed (R. 12); some witnesses were solicited

by the prosecution to perjure themselves (R. 12), while

others who sought to help petitioner were intimidated and

threatened (R. 12); and manufactured evidence was ad

mitted and used against him at the trial (R. 13).

Petitioner Burns was not furnished counsel, nor allowed

to obtain the advice of counsel until one day before his

trial (R. 3). Important evidence in his favor was sup

pressed (R. 4 ); and testimony against him by Calvin

Dennis has since been repudiated as being perjury suborned

by the prosecution (R. 4).

The convictions and sentences of the courts-martial

were approved by the convening authority (R. 1), and the

records forwarded to Washington, D. C., for appellate

review in the Office of the Judge Advocate General, United

States Air Force (R. 2). The appellate proceedings

provided by the military establishment were completed by

petitioners when on January 28, 1952, their petitions for

new trials were denied by the Judge Advocate General and

the sentences of death were ordered executed (R. 2).

5

Having thus exhausted all available remedies provided

by the military, petitioners filed petitions for writs of

habeas corpus in the United States District Court foi the

District of Columbia (R. 1). The convictions and sentences

were attacked as void and beyond the jurisdiction of the

military courts-martial because of gross irregularities,

improper and unlawful practices amounting to a depiiva-

tion of fundamental rights guaranteed to petitioners by

the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the United States

Constitution and by the Articles of War (R. 4-5). Respon

dents, without controverting the allegations in the peti

tions, moved to discharge the rules to show cause and dis

miss the petitions on the ground that they failed to state

a claim upon which the relief sought could be granted in

that the petitions did not state requisite jurisdictional

facts (R. 5-8). Upon consideration of these motions, and

without factual inquiry, the District Court on April 10,

1952, filed memorandum opinions sustaining respondents’

position (R. 18), and on April It, 1952, entered oideis dis

charging the rules to show cause and dismissing the peti

tions (R. 20).

Petitioners appealed to the United States Couit of

Appeals and on July 31, 1952, that court, one judge dis

senting, affirmed the judgment of the District Court (R. 57).

On September 19, 1952, an order was issued by this Court

staying execution of sentences of death imposed pending

timely filing and disposition of petitions foi writ of

certiorari.

Specifications of Error

The court below erred:

1. In refusing to order a hearing on the merits in the

district court on petitioners ’ allegations of denial of funda

mental due process by military authorities.

6

2. In refusing to make its own independent evaluation

of the merits of petitioners’ claimed denial of constitu

tional rights in the conduct of the military proceedings.

3. In refusing to hold that these courts-martial lost

jurisdiction in permitting the prosecution to use evidence

which had been illegally obtained by civil authorities to abet

the conviction of these petitioners.

Reasons For Allowance of the Writ

1. This Court has never expressly determined whether

violations of the guarantees of fundamental due process

in court-martial proceedings can be corrected in a habeas

corpus proceeding*. The question is one of great import

ance to the administration of military justice. Moreover,

recent opinions of this Court lend support to both a broad

and a narrow view of the reach of habeas corpus in this

area. As a result there is considerable confusion and

uncertainty in the federal courts.

Early cases set forth the rule that the scope of habeas

corpus is limited to a test of the jurisdiction of the tribunal

rendering judgment. Ex Parte Lange, 18 Wall 163;

Ex Parte Siebold, 100 U. S. 371. Thus, a federal district

court, in a habeas corpus proceeding, could only determine

whether the judgment was void for want of jurisdiction.

This test was applied by this Court to convictions had in

state and federal trial courts as well as in courts-martial.

See Ex Parte Siebold, supra; Ex Parte Royall, 117 U. S.

241; United States v. Grimley, 137 U. S. 147.

In the case of state and federal convictions, however,

the reach of habeas corpus has been gradually expanded

in a number of landmark decisions. This has been accom

plished conceptually by two different approaches. In one

7

line of eases the concept of jurisdiction has been widened.

In Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86, it was recognized that a

trial dominated by mob hysteria constituted a denial of due

process and was thus absolutely void. In Johnson v.

Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458, where a petitioner had been denied

the right to counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment,

this Court held that the trial court thereby lost jurisdic

tion. As recently as Sunal v. Large, 332 U. S. 174, it was

indicated that a denial of the protection of the Fifth

Amendment was “ jurisdictional” in nature. See also

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219, 237.

In a second line of cases, lack of jurisdiction and denial

of due process have been considered as two separate and

distinct grounds for habeas corpus. Mooney v. Holohan,

294 U. S. 103 (involving the knowing use by state authorities

of perjured testimony), pointed the way by holding that

such a conviction could be attacked in habeas corpus pro

ceedings as a denial of due process. More recently, in

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101, where the petitioner

alleged that his plea of guilty had been coerced, this Court

recognized both lack of jurisdiction and denial of due

process as bases for the issuance of a writ of habeas corpus.

Irrespective of whether denial of due process has been

embraced in an expanded concept of jurisdiction or whether

it has been considered as a separate basis for the issuance

of the writ of habeas corpus, little confusion has resulted

in the area of federal and state convictions. Both ap

proaches have led to the same result. See Behrens v.

Hironimus, 166 F. 2d 245 (C A 4th 1948); Graham v. Squier,

132 F. 2d 681 (C. A. 9th 1942), cert. den. 318 U. S. 777.

With respect to the scope of habeas corpus in the case

of court-martial convictions, however, there has been con

siderable confusion and uncertainty. This Court has never

expressly declared that a court-martial conviction in vio

8

lation of the guarantees of due process can be corrected

in a habeas corpus proceeding, either on the theory of

Johnson v. Zerhst, supra, or the theory of Waley v. John

ston, supra.

In Wade v. Hunter, 336 U. S. 684, the same test used in

civil cases was applied in determining whether petitioner’s

conviction by a court-martial was in violation of the double

jeopardy provision of the Fifth Amendment. Since it was

found that petitioner had not been placed in double jeop

ardy, it was unnecessary to decide whether a court-martial’s

overruling of a plea of former jeopardy may be subject

to attack in habeas corpus proceedings. In Humphrey v.

Smith, 336 U. S. 695, it was indicated that a court-martial

trial not fairly conducted could be collaterally attacked

in habeas corpus proceedings. There, Mr. Justice Black

stated at page 701:

‘ ‘ This court-martial conviction resulting from a trial

fairly conducted cannot be invalidated by a judicial

finding that the pre-trial investigation was not car

ried on in the manner prescribed by the 70th Article

of W ar.”

The two most recent cases, Whelchel v. McDonald, 340 U. S.

122, and Hiatt v. Brown, 339 U. S. 103, reiterated the rule

that the scope of habeas corpus proceedings is limited to

an inquiry into the jurisdiction of the court-martial. Both

cases, however, indicate the concept of jurisdiction has been

expanded in this area also. In Whelchel v. McDonald,

supra, this Court said that a court-martial proceeding

which denied to an accused the right to tender the issue of

insanity would be divested of its jurisdiction, but refused

to decide whether a denial of due process by a court-martial

offers a separate and independent ground to support a

petition for habeas corpus. Mr. Justice Douglas, at page

124, stated:

9

“ We put to one side the due process issue which re

spondent presses, for we think it plain from the law

governing court-martial procedure that there must

be afforded a defendant at some point of time an op

portunity to tender the issue of insanity. It is only

a denial of that opportunity which goes to the question

of jurisdiction.”

Dicta in other opinions have intensified the uncertainty

in this area. In Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U. S. 763, 783,

this Court stated that, “ American soldiers conscripted into

the military service are thereby stripped of their Fifth

Amendment rights * * Similar expressions can be

found in Ex Parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1, 40, 45.

This confusion and uncertainty has been reflected in

the opinions of district courts and courts of appeals. Dicta

in Ex Parte Quirin, supra, led the Court of Appeals for

the Second Circuit to declare that the Fifth and Sixth

Amendments are inapplicable to a court-martial. United

States v. Crystal, 131 F. 2d 576, 577 n. 2 (CA 2d 1943), cert,

den. 319 U. S. 755.1 In In re Wrublewski, 71 F. Supp. 143,

the District Court for the Northern District of California,

confronted with a petition alleging conviction by a court-

martial in violation of the double jeopardy provisions of

the Fifth Amendment, held that it lacked jurisdiction, rely

ing on Ex Parte Quirin, supra; Ex Parte Milligan, 71 U. S.

2; United States v. Crystal, supra. On appeal the court

assumed for the purpose of the decision, that the provision

was applicable. Wrublewski v. Mclnerney, 166 F. 2d 243

(CA 9th 1948).

Other courts have acted similarly, apparently reluctant

in the absence of a clear pronouncement from this Court

1 But cf. United States v. Sivenson, 165 F. 2d 756 (C. A. 2d

1948) ; Becker v. Webster, 171 F. 2d 762 (C. A. 2d 1949), cert. den.

336 U. S. 968.

10

to expressly hold that habeas corpus was available to cor

rect violations of due process. See Schita v. King, 133 F.

2d 283 (CA 8th 1943); De War v. Hunter, 170 F. 2d 993

(CA 10th 1948), cert den. 337 U. S. 908; Waite v. Overlade,

164 F. 2d 722 (CA 7th 1947), cert, den. 334 U. S. 812.

On the other hand, the Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit, in United States ex rel. Innes v. Hiatt, 141 F. 2d

664 (CA 3d 1944), expressly held that an individual does

not lose the protection of the Fifth Amendment because

he has joined the armed forces and that a civil court in a

habeas corpus proceeding may determine whether the

court-martial proceeding was in accord with standards of

due process.

The decisions in the instant case are typical of this con

fusion. The District Court dismissed the petition, holding

that it lacked jurisdiction to inquire into alleged denials of

fundamental due process. The Court of Appeals, while

refusing to issue the writ, concluded that habeas corpus is

available to correct a denial of due process by military

authorities. Its opinion also illustrates the difficulty of

resolving this issue in the absence of a clear pronouncement

by this Court.

The vital importance of this question to the administra

tion of military justice need not be belabored. Millions of

American citizens—members of the armed forces as well

as civilians—are now subject to military jurisdiction. The

present state of international affairs gives every indication

that our armed forces will not be reduced for many years.

Military law can no longer be looked upon as a mere in

strument for the maintenance of discipline. With so many

Americans now affected and likely to be affected in the

future, the time is ripe for a clear-cut determination by this

Court that those subject to military jurisdiction are not

beyond the reach of the protective guarantees of the Federal

11

Constitution, and that where constitutional guarantees have

been abridged under military law, resort may be had to a

civil court to secure that protection which the Constitution

affords to all American citizens.

2. The decision of the Court of Appeals in not remand

ing the case to the district court for a hearing is in conflict

with Walker v. Johnston, 312 IT. S. 275 and House v. Mayo,

324 U. S. 42.

Petitioners allege that they were convicted in outrage

ously unfair proceedings. Buttressed by affidavits of dis

interested persons, the petitions for writs of habeas corpus

make out cases of grave denials of due process. Respond

ents denied none of these allegations. Hence, it was in

cumbent upon the District Court and the Court of Appeals

to assume the allegations to be true. House v. Mayo, supra.

Since the District Court held no hearing to determine the

validity of petitioners’ allegations, the Court af Appeals

should have remanded the cause for hearing on the merits.

Its failure to do so constituted serious error. Walker v.

Johnston, 312 U. S. 275. There the Court stated in an opin

ion by Mr. Justice Roberts at page 287:

“ Not by the pleadings and the affidavits, but by

the whole of the testimony, must it be determined

whether the petitioner has carried his burden of

proof and shown his right to a discharge. The

Government’s contention that his allegations are

improbable and unbelievable cannot serve to deny

him an opportunity to support them by evidence.

On this record it is his right to be heard. ’ ’

a. Both petitioners allege that they were arrested by

the civil police authorities of Guam on January 7, 1949,

and that they were held without arraignment by any au

thority until January 17, 1949. During this time they were

12

held incommunicado and subjected to continuous question

ing; they were also beaten, denied sleep and deprived of

edible food. They were not allowed to consult counsel

despite their requests (R. 2-3,10-11; Affidavits of Grimmett,

Herman Dennis, Daly and Hill). Further, their detention

was in violation of Sections 686, 825 and 780 of the Penal

Code of Guam.

Petitioner Dennis further alleges that as a result of

physical and mental duress, four confessions were ex

tracted from him on January 11th, 12th and 13th and were

introduced against him at his trial. All the confessions

were repudiated before, at and after the trial. If these alle

gations are true, the confessions were clearly coerced and

their use at the trial constituted a denial of due process.

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227; Watts v. Indiana, 338

U. S. 49.

The uncontradicted facts as revealed by the court-

martial record lead to the inescapable conclusion that the

confessions were involuntary. One of the chief witnesses

for the prosecution, Albert E. Riedel, a police investigator

brought from California, testified that the murder of Ruth

Farnsworth had created an atmosphere of extreme tension

on Guam (Herman Dennis, C. M. Trans. 207). In this

atmosphere a large group of Negro soldiers were asked to

take lie detector tests in connection with the investigation

with respect to this crime (Herman Dennis, C. M. Trans.

217). Petitioner Dennis submitted to the test on January

7 and was thereafter immediately arrested without being

informed of its results. He was held incommunicado until

after four confessions were extracted (Herman Dennis,

C. M. Trans. 193, 221). After occasional questioning on

January 7, 8 and 10th and prolonged questioning on Jan

uary 11 by two interrogators working in shifts, petitioner

Dennis made his first confession (Herman Dennis, C. M.

13

Trans. 188-200). It should be noted that petitioner Dennis

was only 20 years old, with a limited education; he was a

member of the armed forces, thousands of miles from home,

and accused of a most heinous crime ( United States v.

Dennis, 4 A. C. M. 872, 906). In the light of these facts, we

submit, the involuntary character of these confessions is

clearly established. Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401;

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547; White v. Texas, 310 U. S.

530.

The Court of Appeals disposed of petitioner’s allega

tion concerning these confessions on the theory that their

involuntariness was a disputed issue of fact which had

been decided adversely to petitioner. It accepted the de

termination of the military without making an independent

evaluation of the evidence for itself. This Court, however,

has emphasized that it will make an independent examina

tion of the record to determine the validity of a claim

that a coerced confession was used to convict. Lisenba v.

California, supra. Even assuming arguendo that the un

contradicted facts do not necessarily lead to a conclu

sion that the confessions were coerced, the allegations of

the petition, considered against the background of the un

contradicted facts, entitled petitioner to a hearing on the

merits and to an independent determination by the court

of the character of these confessions.

b. Petitioner Dennis also alleges that certain pubic

hairs taken from his person during his unlawful detention,

and without his being advised of his constitutional rights,

were used against him at his trial (R. 12). This, we submit,

is compulsory self-incrimination in violation of the Fifth

Amendment. See Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165. The

Court of Appeals, however, ignored this allegation.

c. Petitioner Dennis further alleges that specimens of

his pubic hair presented at the trial were deliberately

14

planted in an effort to create evidence tending to establish

his guilt (R. 13; Affidavit of Herman Dennis). Such con

duct on the part of the prosecution would certainly con

stitute a flagrant violation of due process under the general

principles enunciated by this Court in Mooney v. Holonan,

294 U. S. 103 and Pyle v. Kansas, 317 U. S. 213. The Court

of Appeals disposed of this allegation on the ground that

so long as a disputed question of fact had been presented

to the duly constituted military authorities, it had no duty

to consider it. Again, we submit, that as to this allega

tion petitioners were entitled to a hearing on the merits in

the District Court. Petitioners urge that at the very least

the Court of Appeals was required to evaluate the evidence

independent of the conclusion reached by military authori

ties.

d. Both petitioners allege that, important evidence relat

ing to Filipino dog-tags and a navy uniform found near

the scene of the crime was suppressed by the prosecution

(R. 4, 12; Affidavit of Daly). If the allegations are true,

these convictions are in violation of the Fifth Amendment.

Mooney v. Holonan, supra; Pyle v. Kansas, supra.

The Court of Appeals disposed of this on alternative

grounds. First, it asserted that the affidavit of Lt. Col.

Daly in support of the allegation was insufficient in that

it did not show that the prosecution had knowledge of the

Filipino dog-tags and the navy uniform. Since the affidavit

of Lt. Col. Daly avers that both items were in the pos

session of the Guam Police Department, and the records

in these cases reveal that there was an intimate working

relationship between the civil government of Guam and

the Air Force, petitioners contend that the civil govern

ment acted here as the agent of the Air Force and its knowl

edge must be imputed to the Air Force. See Anderson v.

United, States, 318 U. S. 350 and Gambino v. United States,

275 U. S. 310. Compare Gallegos v. Nebraska, 342 IT. S.

55, 70.

15

The alternative holding of the Court of Appeals was

that a federal court had no duty to consider this allegation

since it was based on a disputed question of fact which

had already been presented to the duly constituted military

authorities. Again, we submit, petitioners were entitled

to a hearing on the merits in the District Court, and that at

the very least the Court of Appeals was required to evalu

ate the evidence independent of the conclusion reached by

military authorities.

e. Petitioner Dennis avers that the prosecution sought

to procure witnesses to perjure themselves and intimidated

and threatened those who sought to help him (E. 12; Affida

vits of Grimmett, Daly and Hill). As the dissenting opinion

of Judge Bazelon pointed out, the allegation of attempts

to suborn perjury is given specific content by the affidavit

of witness Mary Hill. She avers that one of the prosecu

tion’s chief investigators tried to induce her to make a

false statement before the court-martial relating to the

voluntariness of Dennis’ confession. Moreover, the Judge

Advocate General of the Air Force admitted that there was

substantial evidence that Mrs. Hill was prevailed upon

by the prosecution’s investigator to make a false state

ment ( United States v. Dennis, 4 A. C. M. 872, 906).

Chaplain Grimmet avers that military authorities in

terfered with his efforts to obtain assistance and counsel

for petitioners. Furthermore, Lt. Col. Daly asserts, that

as Staff Judge Advocate of the Marianas Air Material

Command, he had personal knowledge of the fact that the

Chaplain’s cables and mail to the United States were in

tercepted and not delivered to the addressees.

Although the allegations, if true, would render the con

victions void, Mooney v. Holonan, supra; Pyle v. Kansas,

supra, they were ignored by the Court of Appeals.

16

f. Petitioner Burns alleges that the testimony of Calvin

Dennis was coerced and perjured (R. 3-4; Affidavits of

Daly and C. Dennis). Calvin Dennis was the principal

witness appearing against him: without this testimony, the

case against petitioner would be weak indeed. Affiant

Calvin Dennis admits that he committed perjury under

physical coercion, threats and promises. Corroborating

this is the affidavit of Lt. Col. Daly wherein he states that

he was present when an officer authorized to act on behalf

of the Commanding General promised Calvin Dennis that

his sentence would be commuted if he testified against

petitioners, and threatened that he would be sentenced to

death if he failed to do so.

If the above allegations are true, no court could avoid

the compelling conclusion that the convictions were con

trived and therefore void. See Mooney v. Holoncm, supra;

Pyle v. Kansas, supra.

The Court of Appeals disposed of this allegation also

on the ground that it had no duty to examine the merits

of a contention based on a disputed question of fact which

had been resolved by the duly constituted military authori

ties. As previously stated, we take the position that this

was error.

g. Petitioner Dennis alleges a gross abuse of discretion

in the denial by his commanding officer of counsel of his

choice (R. 12; Affidavits of Grimmett, Daly and Hill). The

record shows that petitioner Dennis requested Lt. Col.

Daly to act as his defense counsel and the Commanding

General, after first granting the necessary permission

later denied the request. Lt. Col. Daly alleges that charges

against him were contrived so that he might be made “ un

available.” Affiant Hill asserts that an investigator for the

prosecution attempted to induce her to give false testi

17

mony at the trial upon the promise that it would be helpful

to Col. Daly “ who was then in serious difficulties because

of his attempt to defend the accused.”

Petitioner Burns had only one day to consult counsel

of his choice (E. 4). It is true that he was represented by

duly appointed defense counsel, but in view of the serious

ness of the crime, we submit, his trial should have been

continued in order to permit counsel of his choice to ade

quately prepare his defense.

While this Court has never ruled that such a flagrant

abuse of discretion constitutes a jurisdictional defect or

violates due process, it is submitted that such conduct on

the part of the commanding officer deprives the proceeding

of any semblance of fundamental fairness. See Hiatt v.

Brown, supra. The opinion of the Court of Appeals com

pletely side-steps the essence of this contention.

The Articles of War in force at the time of these court-

martial proceedings accorded the accused the right to

counsel of his own choice if such counsel is reasonably

available. A. W. 17. That petitioners may have had ade

quate counsel does not cure the fact that they were denied

the counsel of their own choice by a flagrant abuse of dis

cretion. Similarly, the fact that petitioners may have had

competent counsel to prosecute their appeals to the Board

of Review and Judicial Counsel is likewise irrelevant.

Both petitioners were deprived of effective counsel of their

choice by a gross abuse of discretion on the part of mili

tary authorities.

h. Petitioners allege that the atmosphere surrounding

the trial was one of hysteria and terror (R. 4). This is

supported by the affidavit of Chaplain Grimmet who as

serts :

‘ ‘ That the feeling was so tense on the Island and the

rumor so strong that there was going to be a riot if

18

the accused were not convicted, that I called the mat

ter to the attention of Col. Tolin who said they were

aware of the situation and that riot troops had been

alerted in case of violence.”

If these allegations are true, the convictions are void. Moore

v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86.

The Court of Appeals was of the opinion that no fact

shown in the record supported this general allegation.

While this may be true,2 it is proper for a petition of

habeas corpus to rely on facts outside the record. Johnson

v. Zerbst, supra; Waley v. Johnston, supra. Petitioners

were entitled to a hearing on the merits in the District

Court and the Court of Appeals erred in not remanding the

cause for that purpose.

Even assuming arguendo that petitioners’ rights to a

hearing could have been satisfied had the Court of Appeals

considered their petitions on the merits, the consideration

given by the Court of Appeals to these cases can hardly

be deemed a hearing. The fact that the Court of Appeals

examined the records and wrote a lengthy opinion may tend

to create the illusion that petitioners were afforded a hear

ing. But the hearing to which these petitioners were en

titled necessitated an independent determination by the

Court of Appeals of all issues relating to alleged violations

of constitutional due process by military authority.

3. This Court should grant certiorari to determine

whether the Court of Appeals was correct in holding that

the doctrine of exhaustion of remedies as applied to state

2 But see the court-martial record of Herman Dennis at page

207.

19

convictions supplied an accurate analogy for tlie instant

fact situation.3

The Court of Appeals, while holding that an accused be

fore a court-martial is entitled to a fair trial within due

process of law concepts, placed upon the military authori

ties the principal responsibility for insuring such fairness.

It concluded that habeas corpus will not lie “ to review

questions raised and determined, or raisable and determin

able, in the established military process, unless there has

been such gross violation of constitutional rights as to deny

the substance of a fair trial and, because of some excep

tional circumstances, the petitioner has not been able to

obtain adequate protection of that right in the military

processes.” It analogized the doctrine of exhaustion of

military remedies to that of exhaustion of state remedies,

relying on the statement by this Court in Ex Parte Hawk,

321 U. S. 114, 118 that a federal court will not ordinarily

re-examine upon habeas corpus questions adjudicated by

state courts, except where resort to those courts “ has failed

to afford a full and fair adjudication of the federal con

tentions raised.”

a. Even if it be assumed pro arguendo that the Court

of Appeals was correct in its analogy, the Court should

clarify the confusion relative to the application of the

doctrine of Ex Parte Hawk to a collateral attack on military

convictions.

8 While this Court in Gusik v. Schilder, 340 U. S. 128, did indi

cate that the analogy was a proper one, the Court was there con

cerned only with the first aspect of the rule— namely that except in

exceptional circumstances, a federal court will not entertain a peti

tion for a writ on habeas corpus on behalf of one in state custody

unless he has exhausted all state remedies, including an appeal or

writ of certiorari from this Court. Gusik v. Schilder had no appli

cation at all to the second aspect of the rule of Ex Parte Hawk dis

cussed infra at page 20.

20

The doctrine of Ex Parte Hawk has a twofold aspect.

The first part of the rule states that federal district court

will not ordinarily entertain a petition for a writ of habeas

corpus from a prisoner in state custody until he has ex

hausted all state remedies, including the filing of a peti

tion for a writ of certiorari in this Court.4 The second

aspect of the rule relates to the scope of habeas corpus

after all of these state remedies have been exhausted.

The application of the latter portion of the Ex Parte

Hawk rule has been subject to considerable uncertainty and

there exists a conflict among the circuits. The Courts of

Appeals for the Fourth and Tenth Circuits have held that

where petitioner’s contentions have been adjudicated on

the merits by the state courts and this Court has denied

certiorari, a district court is justified in granting the writ

of habeas corpus only in unusual circumstances. Goodwyn

v. Smith, 181 F. 2d 498 (C. A. 4th 1950); Gault v. Bur ford,

173 F. 2d 813 (C. A. 10th 1949). On the other hand, the

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit under the same

circumstances has held that a district court must hear and

determine the petition on the merits. United States v.

Baldi, 192 F. 2d 540 (C. A. 3d 1951), cert, grant. 343 U. S.

903. There Judge Goodrich said at 544:

“ Each point raised by the relator is to be tested

by whether it alleges a violation of rights under

the United States Constitution: nothing more. That

these allegations have been decided on the merits

by the highest state court is a fact to be given weight

by a District Court in passing upon petitions for

habeas corpus. But the fact does not relieve the

federal court of the duty to pass upon the merits

of the petition.”

4 Sec. 28, U. S. C. § 2254.

21

This confusion with respect to the application of the doc

trine of Ex Parte Hawk is multiplied manifold when the doc

trine is transplanted from its home soil to a completely

new area—collateral attack on military convictions. Since

the Baldi case is now pending before this Court, it is espe

cially appropriate that this related issue be decided.

If the view of the Third Circuit is correct, then clearly

the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia erred in

the instant case by not remanding the cause to the District

Court for a hearing. Even should the approach of the

Third Circuit be rejected, the decision of the court below,

it is submitted, is in conflict with Moore v. Dempsey, supra.

There petitioner alleged that his trial was conducted in

an atmosphere of mob hysteria and this Court held that

the presence of a state appellate corrective procedure was

not a sufficient ground for a federal court to refrain from

examining the facts for itself. Mr. Justice Holmes stated

at p. 91:

“ But if the case is that the whole procedure is

a mask—that counsel, jury, and judge were swept

to the fatal end by an irresistable wave of public

passion, and that the state courts failed to correct

the wrong * * * perfection in the machinery for

correction * * * [cannot] prevent this court from

securing to the petitioners their constitutional

rights. ’ ’

When the allegations in the instant cases are considered

in their totality, they paint a bleak picture—a proceeding

nothing less than shocking which deprived the two accused

of the most minimal standards of justice. If these allega

tions are true, the convictions stand exposed as contrived

through a “ pretense of a trial” and are as utterly void as

the one considered in Moore v. Dempsey.

22

b. Appellants further submit that the Court of Appeals,

in resolving the instant case by a rule analogous to the

doctrine of exhaustion of state remedies, ignored the fact

that collateral attack on military convictions brings into

play many considerations which are significantly different

from those pertinent to a collateral attack on state convic

tions.

First, an important aspect of the Ex Parte Hawk rule

is that in exhausting state remedies, the petitioner must

seek a writ of certiorari in this Court. Darr v. Burford,

339 U. S. 200. Thus, even before petitioning a federal dis

trict court for a writ of habeas corpus, one convicted by

a state court has the right to ask this Court to grant cer

tiorari. Those convicted by a military court-martial, on

the other hand, have no similar right to ask this Court to

review the proceedings. At the time petitioners were

convicted, a writ of habeas corpus offered the only way for

any kind of non-military review of the proceedings.

Second, underlying the rule of Ex Parte Hawk is the

necessity for maintaining a harmonious federal-state rela

tionship. Darr v. Burford, supra. A collateral attack on

court-martial convictions, however, presents no such prob

lem. Once military remedies are exhausted, it can hardly

be considered unseemly for a federal district court to upset

a determination by a military agency of the federal govern

ment.

Third, the court below completely ignored the tremend

ous differences between military and civil proceedings.

The dangers of command control have been the subject of

much concern. See Hearings Before Sub-Committee of

the Committee on Armed Services on S. 857 and H. R. 4080;

United States Senate, 81st Cong. 1st Session (1949); Farmer

and Wells, Command Control—or Military Justice, 24 N. Y.

IJ. L. Q. Rev. 263 (1949); Notes, 35 Cornell L. Q. 15 (1949);

2 Stanford L. Rev. 547 (1950). A fair and impartial trial

23

is obviously difficult in an atmosphere of command control.

An officer who the commander believes is too lenient can be

removed from service on courts; and defense counsel who

is too successful may not remain a defense counsel very

long. All the personnel connected with the trial are de

pendent on the commanding officer for assignments, leaves

and positions. Cf. Report of War Dept. Advisory Com

mittee in Military Justice (1946). Under these circum

stances, officers are necessarily susceptible to command

influence.

Similarly, the review procedure in force at the time of

petitioners’ convictions is a far cry from civilian stand

ards. Review by the Judge Advocate General’s depart

ment is review by a partially interested party. When as

here, motions for new trials are presented to the Judge

Advocate General, no hearing is held to permit a petitioner

to prove his allegations, no counter-affidavits are sub

mitted; the Judge Advocate General investigates the

charges, satisfies himself as to the substance of the allega

tions, and there is no appeal from his decision. Such pro

ceedings produce no record and a federal district court

on habeas corpus must either accept the fairness of the

proceedings as a matter of faith, or make an independent

inquiry into the truth of the allegations.

In view of the above considerations, we urge this Court

to grant the writ and hold that the limitations which some

courts have placed on the writ of habeas corpus where

state convictions are attacked should not apply to military

convictions.5 Where there are allegations of gross denials

5 It has long been held that there is no presumption that a court-

martial possessed jurisdiction, since it is a tribunal of limited juris

diction. McClaughry v. Deming, 186 U. S. 49, 63. It would seem

to follow logically from the above rule that a petitioner alleging

such gross denials of due process which would oust the court-martial

of its jurisdiction should have the right to prove his allegations in

a civilian court.

24

of due process, as in the instant cases, it is the duty of the

district court to make an independent inquiry into the

facts.6 If petitioners are denied their right to a hearing

before a civilian court, their rights under the Fifth and

Sixth Amendments become mere empty, hollow guarantees.

4. The use of evidence unlawfully obtained by the civil

authorities of Guam impaired the jurisdiction of the court-

martial proceedings. Petitioners were placed under arrest

by the civil authorities on Guam. They were subject to

the jurisdiction of the civil government of Guam.7 Their

detention was in flagrant violation of Sections 686, 780 and

825 of the Penal Code of Guam 8 which provide for arraign

ment before a judge within 24 hours and grant the prisoner

on request the right to consult an attorney any time after

arrest. As hereinbefore set out, it was during this period

that petitioners were held incommunicado without process,

denied counsel, subjected to physical and mental duress,

and the confessions extracted. Had petitioners been tried

by the civil authorities and had the evidence obtained

during this period been used to convict them, the con

victions clearly could not stand. See McNabb v. United

States 318 U. S. 332; Weeks v. United States, 232 U. S. 358.

Convictions obtained by the Air Force with the use of

such evidence can stand on no stronger ground. One arm

of the federal government cannot reap the unlawful fruits

of another arm. Anderson v. United States, 318 U. S. 350 ;

Gambino v. United States, 275 U. S. 310. See Gallegos v.

Nebraska, 342 U. S. 55, 70.

In the Anderson case appellants were tried and con

victed in a federal district court for damaging federal

6 See opinion of Chief fudge Biggs in Hicks v. Hiatt, 64 F.

Supp. 238, 249, n. 27 (M . D. Pa., 1946).

7 Penal Code of Guam (1947) Sec. 27.

8 Penal Code of Guam (1947).

25

property. They had been arrested by local authorities,

held incommunicado and denied counsel by local and state

officers; and coerced confessions were extracted from some

of them in violation of state procedure. Subsequently,

they were arrested by federal officers and convicted on the

basis of the illegal confession secured by the state and local

officials. The Court, in reversing the conviction, declared

at page 356:

“ There was a working arrangement between the fed

eral officers and the sheriff of Polk County which

made possible the abuses revealed by this record.

Therefore, the fact that the federal officers them

selves were not formally guilty of illegal conduct

does not affect the admissibility of the evidence

which they secured improperly through collabora

tion with state officers.”

And, this Court in the Gambino case said at pages 316,

317:

“ the rights guaranteed by the 4th and 5th Amend

ments may be invaded as effectively by such co

operation, as by the state officers acting under di

rection of the Federal officials * * * The prosecution

thereupon instituted by the Federal authorities was,

as conducted, in effect a ratification of the arrest,

search and seizure made by the troopers on behalf

of the United States.”

Thus, we submit, the courts-martial were divested of

jurisdiction by the use of evidence unlawfully obtained by

the civil government during the period of petitioners’

unlawful confinement, and these convictions cannot stand.

2 6

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, it is

respectfully submitted that this petition for writ of cer

tiorari be granted.

R obert L. Carter,

F ran k D. R eeves,

T hurgood M arshall ,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H . C h iso lm ,

D avid E . P in s k y ,

L eonard W . S chroeter,

of Counsel.

27

APPENDIX

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1488:

* * * rj’ju, accusec[ ghaii have the right to be repre

sented in his defense before the court by counsel of

his own selection, civil counsel if he so provides, or

military if such counsel be reasonably available,

otherwise by the defense counsel duly appointed

for the court pursuant to Article 11 (Sec. 1482

of this title) * * *

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1495:

* * * No witness before a military court, com

mission, court of inquiry, or board, or before any

officer conducting an investigation, or before any

officer, military or civil, designated to take a deposi

tion to be read in evidence before a military court,

commission, court of inquiry, or board, or before

an officer, conducting an investigation, shall be com

pelled to incriminate himself or to answer any ques

tion the answer to which may tend to incriminate

him, or to answer any question not material to the

issue when such answer might tend to degrade him.

Title 10, United States Code, Section 1542:

* * * When any person subject to military law is

placed in arrest or confinement, immediate steps

will be taken to try the person accused or to dismiss

the charge and release him * * *

Penal Code of Guam

Section 27. Crimes, persons liable to punishment for.

■—The following persons are liable to punishment under the

laws of this Naval Government of Guam:

2 8

(1) All persons who commit, in whole or in part, any

crime within this Island;

(2) All who commit any offense without this Island

which, if committed within this Island, would be larceny,

theft, robbery, or embezzlement under the laws of this

Naval Government, and bring the property stolen or em

bezzled, or any part of it, or are found with it, or any part

of it, within this Island;

(3) All who, being without this Island, cause or aid,

advise or encourage, another person to commit a crime

within this Island, and are afterward found therein;

(4) All who commit any offenses without this Island and

outside the territorial jurisdiction of any other country,

which if committed within this Island would be a felony,

and the offender and body of the crime are subsequently

found within this Island.

Section 686. Right of defendant in criminal action.—

In a criminal action the defendant is entitled:

(1) To a speedy public and oral trial.

(2) To be allowed counsel as in civil actions, or to

appear and defend in person and with counsel.

(3) To be informed of the nature and cause of the accu

sation against him.

(4) To be exempt from testifying against himself.

(5) To be allowed to testify in his own behalf; if he

fails to testify, such failure shall not be construed as evi

dence against him; but if he does so testify, he may be

cross-examined like other witnesses.

(6) To have compulsory process issue for obtaining

witnesses in his favor.

29

(7) To produce and examine witnesses in his behalf

and to be confronted with and to cross-examine any wit

nesses against him, in the presence of the court, except

that where the charge has been preliminarily examined

before a committing judge and the testimony taken down

by question and answer in the presence of the defendant,

who has, either in person or by counsel, cross-examined

or had an opportunity to cross-examine the witness; or

where the testimony of a witness on the part of the prose

cution, who is unable to give security for his appearance,

has been taken conditionally in the like manner in the pres

ence of the defendant, who has, either in person or by

counsel, cross-examined or had an opportunity to cross-

examine the witness, the deposition of such witness may be

read, upon its being satisfactorily shown to the court that

he is dead or insane, or cannot with due diligence be found

within the Island; and except also that in the case of

offenses hereafter committed the testimony on behalf of

the prosecution or the defendant of a witness deceased,

insane, out of jurisdiction, or who cannot, with due dili

gence be found within the Island, given on a former trial

of the action in the presence of the defendant who has,

either in person, or by counsel, cross-examined or had

an opportunity to cross-examine the witnesses may be

admitted.

(8) To appeal.

Section 780. Preliminary investigation by the police

department. How, when, and ivhere conducted. Powers

of the chief of police, Island attorney to attend.— (a) The

conduct of the preliminary investigation as to procedure,

time and place lie within the discretion of the chief of police

of Guam, (b) For the purpose of investigating public

offenses, the chief of police of Guam shall have the power

to summon witnesses before him for questioning but shall

30

provide government transportation to persons so sum

moned from outlying* districts, (c) Whenever any per

son accused of two public offenses is brought before the

chief of police for investigating, such person:

(1) Shall be informed of the accusation against him.

(2) Shall be infoi’med that any statement he may make,

may be used against him.

(3) Shall not be compelled to be a witness against him

self.

(d) Whenever the investigation indicates that a public

offense has been committed triable in the courts of Guam

other than in the police courts, the chief of police shall

notify the Island attorney. The Island attorney or his

deputy shall then attend the investigation by the police

department.

Section 825. Right of attorney to visit prisoner.—The

defendant must in all cases be taken before the judge with

out unnecessary delay, and, in any event, within 24 hours

after his arrest excluding Sundays and holidays; and after

such arrest, any attorney at law entitled to practice in

the courts of records of Guam may, at the request of the

prisoner or any relative of such prisoner, visit the person

so arrested.