Smith v Allwright Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1943

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Allwright Brief for Petitioner, 1943. 641b7ec1-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fe7a4b35-d3b3-4a09-944b-fac534d38639/smith-v-allwright-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

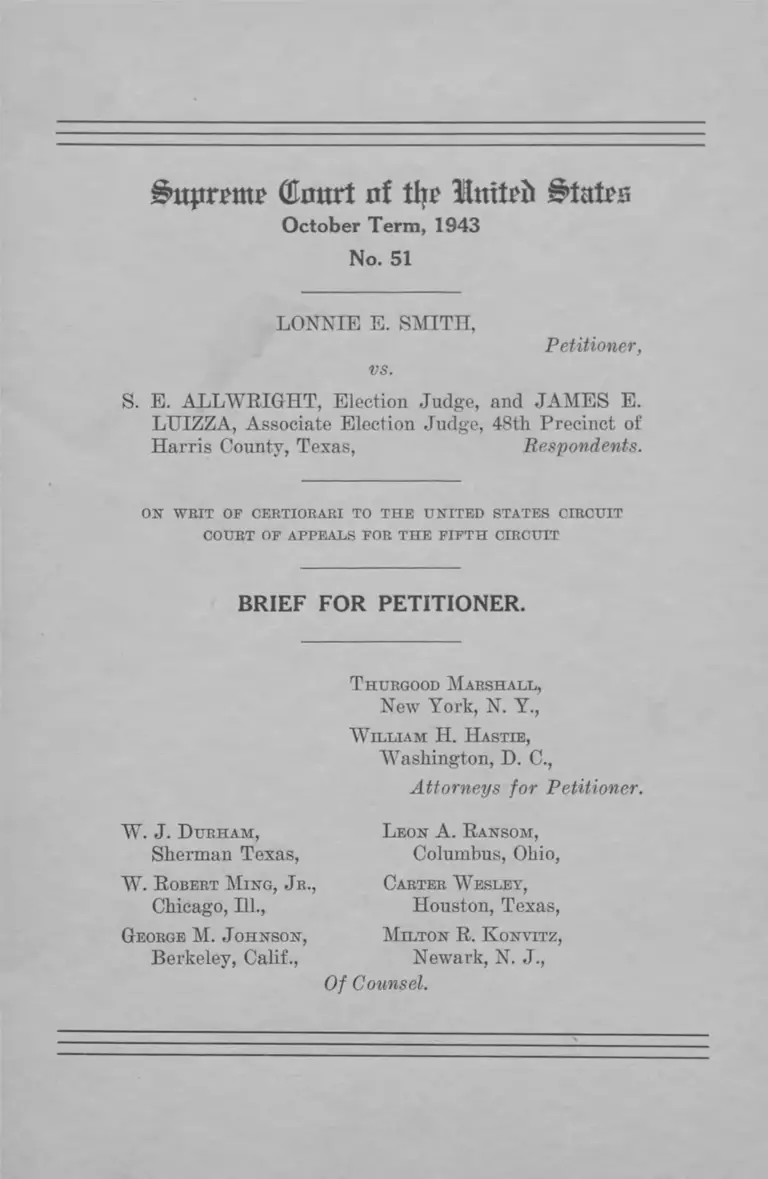

Gkmrt nf tin lluttrii States

October Term, 1943

No. 51

LONNIE E. SMITH,

vs.

Petitioner,

S. E. ALLWRIGHT, Election Judge, and JAMES E.

LUIZZA, Associate Election Judge, 48th Precinct of

Harris County, Texas, Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES CIRCUIT

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E F IF T H CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER.

T hurgood Marshall,

New York, N. Y.,

"William H. H astie,

Washington, D. C.,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W. J. D u r h a m ,

Sherman Texas,

W. R obert M ing, J r.,

Chicago, 111.,

George M. J ohnson,

Berkeley, Calif.,

L eon A. R ansom,

Columbus, Ohio,

Carter W esley,

Houston, Texas,

M ilton R. K onvitz,

Newark, N. J.,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion of Court Below---------------------------------------------- 1

Jurisdiction_________________________________________ 1

Summary Statement of Matter Involved-------------------- 2

I. Statement of the Case-------------------------------------- 2

II. Salient Facts --------------------------- 3

The Democratic Party in Texas _------- -------------------- __ 5

Expenses of the Primary----------------------------------------- 5

Errors Relied Upon___________________ ___ ______-..... 6

Argument:

I. The Constitution and laws of the United States

as construed in United States v. Classic prohibit

interference by respondents with petitioner’s

right to vote in Texas Democratic Primaries___ 8

A. The rationale of the Classic case applies to

a civil action for denial of the right to vote

because of race or color in a Louisiana Pri

mary election ____________________________ 9

B. There is no essential difference between pri

mary elections in Louisiana and in Texas___ 11

1. Texas like Louisiana has made primary

elections “ an integral part of the proce

dure of choice” _________________________ 12

PAGE

11

PAGE

2. In Texas as in Louisiana the Democratic

primary in fact “ effectively controls the

choice” of Senators and Representatives 16

C. The respondents herein are subject to the

controlling federal statutes------------------------ 17

II. The action of respondents herein was in viola

tion of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments _______________________________________ 22

A. The conduct of respondents in denying peti

tioner a ballot to vote in the Texas Demo

cratic primary was state action------------------- 22

B. New matter disclosed in the present record

destroys the factual basis for the decision in

Grovey v. Townsend_______________________ 24

Conclusion---------------------------------------------------------------- 30

Table of Cases.

Avery v. Alabama, 308 U. S. 444 (1940)---------------------- 26

Barney v. City of New York, 193 U. S. 430 (1904)______ 21

Bell v. Hill, 123 T̂ ex. 531, 74 S. W. (2d) 113 (1934)_____ 26

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940)_________ 26

Des Moines v. Des Moines City Ry., 214 U. S. 179 (1909) 21

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 346 (1879)_________ 20, 23

Great Northern Railway v. Washington, 300 U. S. 154

(1937)___________________________________________ 27

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935)___21, 23, 25, 27, 29

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915)__________ 18

Ill

PAGE

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 469, 507, 519 (1939) __ ____________________20, 23

Home Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227

U. S. 278 (1913)_____________________________20,21,23

Iowa-Des Moines National Bank v. Bennett, 284 U. S.

239 (1931)_______________________________________ 21

Kaufman et al. v. Parker, 99 S. W. (2d) 1074 (1936)— 14

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939)_________________ 11

Mason Co. v. Tax Commission, 302 U. S. 186 (1937)------ 27

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1915)-------------------11,18

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932)— 1---------- -------- — 18

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 540 (1927)__________ 9,18

Norris v. Alabama, 294 IT. S. 587 (1935)-------------------- 26, 27

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, at p. 358 (1939)------- 27

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932)------------------------ 26

Raymond v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20 (1907)_ 21

Siler v. Louisville and Nashville R. R., 213 U. S. 175

(1909)___________________________________________ 21

Small v. Parker, 119 S. W. (2d) 609 (1938)___________ 14

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, at p. 130 (1940)_________ 26

State v. Meharg, 287 S. W. 670, 672 (1926)____________ 17

United Gas Co. v. Texas, 303 U. S. 123 (1937)_________ 27

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (i941) -1, 9,12,15,16

17, 20, 22, 23, 24

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 (1942) 26

Statutes and Authorities Cited.

Article 1 United States Constitution__________________ 8

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the United

States Constitution__________________________ 22, 23, 24

Seventeenth Amendment of the United States Constitu

tion --------------------------------------------------------------------- 8

United States Code:

Title 8 Section 31 _______________________________ 17

Title 8 Section 43 _______________________________ 22

Title 18 Section 5 2 _______________________________ 10

Title 28 Section 41 (1 1 )___________________ 2,8,18

Title 28 Section 41 (1 4 )__ ________________ 2, 8,18

Title 28 Section 400_______________________ 2, 8,18

General Laws of Texas, 1903 Chapter 51______________ 4

General Laws of Texas, 1905 Chapter 11______________ 4

Vernon’s Revised Civil Statutes of Texas:

Article 2930, 2940 ________________________________ 19

Article 2956 _____________________________________ 15

Article 2975 _____________________________________ 15

Article 3090, 3096 ______________________________ 14,19

Article 3104 _____________________________________ 19

Article 3120, 3128 _______________________________ 15

Congressional Directory (1943) at p. 250____________ 17,18

United States Census (1940)______________ __________ 29

iv

PAGE

(Emtrt of tlje United States

October Term, 1943

No. 51

Lonnie E. S m ith ,

Petitioner,

vs.

S. E. A ll weight, Election Judge,

and J ames E. L uizza, Associate

Election Judge, 48th Precinct of

Harris County, Texas,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CIRCUIT

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER.

Opinion of Court Below.

The opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reported

in 131 F. (2d) 593, as well as in the record filed in this cause

(R. 150-151).

Jurisdiction.

The date of the judgment in this case is November 30,

1942 (R. 152). Petition for rehearing was filed within the

time provided by the Rules of the Circuit Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit and was denied on January 21, 1943

(R. 160).

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under Section

240(2) of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. Sec. 347 (A ) ).

Certiorari was granted June 7, 1943.1

187 L. Ed. 1167.

2

Summary Statement of Matter Involved.

I.

Statement of the Case.

The amended complaint alleged that on July 27, 1940,

and on August 24, 1940, the respondents, acting as election

judges of the 48th Precinct of Harris County, Texas, denied

the petitioner and other qualified electors the right to vote

in the primaries for selection of candidates upon the Demo

cratic ticket for the offices of United States Senator and

Representatives in Congress. Petitioner sought damages

for himself and a declaratory judgment on behalf of him

self and others similarly situated that the actions of the

respondents in refusing to permit qualified Negro electors

to vote in these primaries violated Sections 31 and 43 of

Title 8 of the United States Code in that they had subjected

him to a deprivation of rights secured by Sections 2 and 4

of Article I, and the 14th, 15th and 17th Amendments of

the United States Constitution (R. 4-16)J The amended

answer admitted that respondents refused to permit peti

tioner to vote, but denied that their actions violated the

United States Constitution or laws, because the Democratic

primary in Texas was “ a political party affair” and, there

fore, not subject to federal control (R. 59-71). The parties

agreed to stipulations as to certain material facts (R.

71-76).

The case was heard upon the stipulations (R. 71-76),

depositions (R. 118-147), and oral testimony (R. 96-109).

On May 11, 1942, District Judge T. M. K ennerey filed Find

ings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (R. 80-85), and on

May 30, 1942, entered a final judgment : (1) that the peti- 1

1 Jurisdiction of the federal courts is invoked under Sections 41

(11), 41 (14) and 400 of Title 28 of the United States Code..

3

tioner “ take nothing against” respondents, and (2) issued

a declaratory judgment “ that the practice of the defendants

[respondents here] in enforcing and maintaining the

policy, custom, and usage of which plaintiff [petitioner

here] and other Negro citizens similarly situated who are

qualified electors are denied the right to cast ballots at the

Democratic Primary Elections in Texas, solely on account

of their race or color, is constitutional, and does not deny

or abridge their rights to vote within the meaning of the

14th, 15th, or 17th Amendments to the United States Con

stitution, or Sections 2 and 4 of Article I of the United

States Constitution” (R. 86).

II.

Salient Facts.

All parties to this action, both petitioner and respon

dents, are citizens of the United States and of the State of

Texas, and are residents of and domiciled in said State

(R. 71).

Petitioner is a Negro, native born citizen of the United

States residing in Houston, Harris County, Texas, a duly

and legally qualified elector under the laws of the United

States and the State of Texas, and is subject to no dis

qualification (R. 71).

Petitioner is a believer in the tenets of the Democratic

Party and, as found by the district judge, is a Democrat

(R. 81). Petitioner has never voted for any other candi

dates than those of the Democratic Party in any general

election at all times material to this case; has been and is

ready and willing to take the pledge of persons voting in

the Democratic Primary (R. 71, 81).

A primary and a “ run o ff” primary were held in Harris

County, Texas, on July 27, 1940 and August 24, 1940, for

nomination of candidates upon the Democratic ticket for the

4

offices of United States Senator, U. S. Congressman, Gov

ernor and other State and local officers. Prior to this time

the respondents were appointed and qualified as Presiding

Judge and Associate Judge of Primaries in Precinct 48,

Harris County, Texas (R. 72, 81).

On July 27, 1940, petitioner with his poll tax receipt pre

sented himself to vote in the said Democratic primary, at

the regular polling place for the 48th Precinct and requested

to be permitted to vote. Respondents refused him a ballot

solely because of his race and color, in accordance with

alleged instructions of the Democratic party of Texas (R.

73, 81).

The State of Texas has prescribed the qualifications for

electors in Article 6 of the Texas Constitution and Article

2955 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas. This statute

prescribes identical qualifications for voting in both “ pri

mary” and “ general” elections (R. 11, 12, 23).

Direct primary elections in Texas were created and are

required and controlled in minute detail by an intricate

statutory scheme.1

According to the stipulations of facts made a part of

the Findings of Facts of the District Court: “ At all times

material herein the only State-Wide Primaries held in Texas

have been for nominees of the Democratic Party” (R. 72).

1 The present election laws of Texas originated with the so-called

“ Terrell Law” , being “ An Act to regulate elections and to prescribe

penalties for its violation” (General Laws of Texas, 1903, Chapter

51, p. 133). Sections 82-107 of this statute set out the requirements

for the holding of.primary elections. In 1905 that Statute was re

pealed and in place thereof Chapter 11 of the General Laws of Texas,

1905, was enacted. These statutes established almost identical require

ments for both the “ primary” and “ general” elections as integral parts

of the election machinery for the State of Texas. A comparative

table of present election laws is set out in Appendix C heretofore filed.

Sections of the Constitution of the State of Texas and Sections

of the Texas Election statutes are set forth in Appendix D heretofore

filed.

5

The Democratic Party in Texas.

The Democratic Party is the only party in Texas re

quired by law to hold primary elections (R. 72). The Demo

cratic Party in Texas is a voluntary association of indi

viduals without any rules or procedure for becoming a

member (R. 119). There is no constitution, nor are there

by-laws or fixed rules for the Democratic Party (R. 133,

146). It is admittedly run in a “ slip-shod” manner (R.

146). There are no permanent records (R. 131). There are

no fixed rules for the “ government of the affairs of the

Party” other than the election laws of the State of Texas

(R. 133-134). The policy of the party is dictated by the

conventions held every two years. There are no permanent

officers of the party (R. 125). Officers of the convention

are elected at each convention and their duties end at the

adjournment of the convention (R. 146).

Every two years primary elections are held pursuant to

the elections laws of the State of Texas (R. 131-132). In

the holding of these elections the laws of Texas are followed

(R. 131). There are no rules for holding these elections

other than the election laws of Texas (R. 133-134). At these

primary elections any white elector, regardless of party

affiliation, is permitted to vote (R. 106, 81).

After the elections are held the successful candidates

are certified to the Secretary of State of Texas (R. 128).

This likewise is done pursuant to and by virtue of the elec

tion laws of Texas (R. 128).

Expenses of the Primary.

The County Clerk, the Tax Assessor and Collector, the

County Judge of Harris County all performed their duties

under Articles 3100-3153, Revised Civil Statutes of Texas,

6

in connection with holding of the primaries on July 27,1940,

and August 24, 1940, without cost to the candidates or the

Democratic Party or any official thereof (R. 73).

After such primary the names of the candidates receiv

ing the nomination were certified by the County Executive

Committee, and the State Executive Committee, in turn,

certified such nominees to the Secretary of State who placed

the names of such candidates on the General Election Bal

lot to be voted on in the general election. All services ren

dered in this connection by the Secretary of State were

paid for by the State of Texas (R. 74).

Although some of the expenses of the primary elections

are paid by the Harris County Democratic Executive Com

mittee, it is admitted: “ . . . that it received the funds

therefor by levying an assessment against each person

whose name was placed upon the Primary Ballot for the

two Primaries named, and that the funds unused therefor,

and which remained in the possession of the Harris County

Democratic Executive Committee, were returned prorata

to each candidate for Democratic nominee who had made a

contribution to the Harris County Democratic Executive

Committee, following the assessment so levied” (R. 76).

Errors Relied Upon.

The question presented by the Petition for Certiorari

heretofore granted was:

“ Does the Constitution of the United States pro

hibit the exclusion of qualified Negro electors from

voting in primary elections which are an integral

part of the election machinery of the State and which

are determinative of the choice of Federal officers?”

The Circuit Court of Appeals erred in affirming the

judgment of the trial court denying petitioner relief and

7

issuing a declaratory judgment “ that the practice of the

defendants [respondents here] in enforcing and main

taining the policy, custom and usage, of which plaintiff

[petitioner here] and other Negro citizens are denied the

right to cast ballots at the Democratic Primary Elections

in Texas, solely on account of their race or color, is constitu

tional, and does not deny or abridge their rights to vote

within the meaning of the 14th, 15th, or 17th Amendments

to the United States Constitution, or Sections 2 and 4 of

Article I of the United States Constitution” (R. 86).

The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit should be reversed for the following reasons:

I .

T he Constitution and laws of the U nited States as

CONSTRUED IN U N IT E D STA TE S V. CLASSIC PROH IBIT INTERFER

ENCE BY RESPONDENTS W IT H PE TITIO N E R ’ S RIGH T TO VOTE IN

T exas D emocratic primaries.

A. T he rationale of the Classic case covers a civil

action for denial of the right to vote in a L ouisiana

PRIM ARY ELECTION BECAUSE OF RACE OR COLOR.

B. T here is no essential difference between the

STATUS OF PRIM ARY ELECTIONS IN LO U ISIA N A AND IN

T exas.

(1) Texas like Louisiana has made primary elec

tions “ an integral part of the procedure of

choice ’ ’.

(2) In Texas as in Louisiana the Democratic pri

mary in fact “ effectively controls the choice” of

Senators and Representatives.

C. T he respondents here are subject to the control

ling F ederal Statutes.

8

n.

T he action of eespondents herein was in violation of

the F ourteenth and F ifteenth A mendments.

A. T he conduct of respondents in denying petitioner

A BALLOT TO VOTE IN TH E T E X A S DEM O CRATIC PRIM ARY

was State action.

B. New matter disclosed in the present record de

stroys THE FACTUAL BASIS FOR THE DECISION IN GrOVEY

v. T ownsend.

ARGUM ENT.

I.

The Constitution and laws of the United States as

construed in United States v. Classic prohibit interfer

ence by respondents with petitioner’s right to vote in

Texas Democratic primaries.

In his complaint petitioner charged that respondents

had violated Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8, United States

Code, in that they had subjected him to a deprivation of

rights secured by Sections 2 and 4 of Article 1 and the

Seventeenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States (R. 4-5).1 The courts below held that the petitioner,

a qualified elector of the State of Texas, could not maintain

an action for damages against the respondents, Democratic

primary election judges, who refused to permit petitioner

1 Jurisdiction of the District Court was invoked under sub-divi

sions 11 and 14 of Section 41 and Section 400 of Title 28 of the United

States Code (R . 4-5),

9

and other qualified electors to vote in the Democratic pri

mary elections held July 27, 1940, and August 24, 1940, in

voting precinct 48, Harris County, Texas. These rulings

are inconsistent with the decision of this Court in United

States v. Classic.1

A. The rationale of the Classic case applies to a

civil action for denial of the right to vote be

cause of race or color in a Louisiana primary

election.

In United States v. Classic, supra, all of the Justices

agreed that the right to vote in a direct primary election

which the State has made an integral part of the procedure

of choice among candidates for Congress or which in fact

effectively controls such choice is secured by the Constitu

tion as fully as is the right to vote in a general election.2

The majority of the Court then concluded that the

criminal sanctions of Sections 19 and 20 of the Criminal

Code in terms directed at “ the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Con

stitution and the laws of the United States” were applicable

to the deprivation of the right of a voter to have his ballot

counted in such a primary election.

It necessarily follows that the defendants, Classic, and

others, were likewise liable civilly to the complaining wit

ness under Section 43 of Title 8 of the United States Code,

which is part of the same original Act as Sections 19 and

1 313 U. S. 299 (1941).

2 Compare statement by Holmes, J., in Nixon v. Herndon, 273

U. S. 536, 540 (1927) : “ If the defendants’ conduct was a wrong to

the plaintiff the same reasons that allow a recovery for denying the

plaintiff a vote at a final election allow it for denying a vote at the

primary election that may determine the final result.”

10

20 of the Criminal Code and the language of which closely

approximates the language of Section 20.1

If the person seeking civil remedy has been debarred

from participation in the primary because of race or color,

he need not rely upon the general language of Section 43

alone because the act complained of is expressly prohibited

by Section 31 of Title 8 of the United States Code, under the

heading “ Race, color or previous condition not to affect

right to vote” , which provides as follows:

“ All citizens of the United States who are other

wise qualified by law to vote at any election by the

1 After the adoption of the 13th Amendment, a bill, which became

the first Civil Rights Act (14 Stat. 27) was introduced, the major

purpose of which was to secure to the recently freed Negroes all the

civil rights secured to white men. The second Civil Rights legisla

tion (16 Stat. 140; id. 433) was passed for the express purpose of

enforcing the provisions of the 14th Amendment. The third Civil

Rights Act, adopted April 20, 1871 (17 Stat. 13), reenacted the same

provisions.

Section 43 of Title 8 and Section 52 of Title 18 (Section 20 of

the Criminal Code) of the United States Code are both parts of the

same original bill and although one provides for civil redress and the

other for criminal redress, the language of the two sections is closely

similar:

Sec. 43 of T itle 8

“ Every person who, under color

of any statute, ordinance, regula

tion, custom, or usage, of any

State or Territory, subjects, or

causes to be subjected, any citizen

of the United States or other per

son within the jurisdiction there

of to the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured

by the Constitution and laws,

shall be liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding for

redress. R. S. Sec. 1979.”

Sec. 20 of Criminal Code

“Whoever, under color of any

law, statute, ordinance, regula

tion, or custom, willfully sub

jects, or causes to be subjected,

any inhabitant of any State, Ter

ritory, or District to the depriva

tion of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured or protected

by the Constitution and laws of

the United States, . . . shall be

fined not more than $1,000, or

imprisoned not more than one

vear, or both.” (R . S. Sec. 5510,

Mar. 4. 1909, c. 321, sec. 20, 35,

Stat. 1092.)

11

people in any State, Territory, district, county, city,

parish, township, school district, municipality, or

other territorial subdivision, shall be entitled and al

lowed to vote at all such elections, without distinction

of race, color, or previous condition of servitude;

any constitution, law, custom, usage, or regulation of

any State or Territory, or by or under its authority,

to the contrary notwithstanding. E. S. sec. 2004.”

The dissenting Justices in the Classic case were of opin

ion that Section 20 as a criminal statute should be given a

restrictive construction which would exclude frauds in pri

mary elections from the wrongs embraced by that section.

However, the allowance of a civil remedy is not impeded by

the special restrictive canons of construction which are

peculiarly applicable to criminal statutes. Indeed, Section

43 of Title 8 has been used repeatedly to enforce the right

of the citizen to vote without discrimination because of race

or color.1

This problem of statutory construction is obviated alto

gether by Section 31 of Title 8, supra, since it is directed at

the very wrong now under consideration; namely, the denial

of the right to vote at any election because of race or color.

Once a primary becomes an election within the purview

of federal authority, Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8 provide

the voter with a civil remedy calculated to protect his right

to vote in such primary election without distinction because

of race or color. It follows that if the present petitioner

were a Negro citizen of Louisiana complaining of acts in

that State identical with those which occurred in Texas, he

would have a cause of action under the doctrine of this

Court in United States v. Classic, supra.

1 See Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1915) ; Lane v. Wilson,

307 U. S. 268 (1939).

12

B. There is no essential difference between pri

mary elections in Louisiana and in Texas.

A comparison of primary elections and primary election

laws in Texas with primary elections and primary election

laws in Louisiana, demonstrates that in Texas, as in Louisi

ana, “ the state law has made the primary an integral part

of the procedure of choice [and that] . . . in fact the pri

mary effectively controls the choice’ ’.1

1. Texas like Louisiana has made

primary elections “ an integral

part of the procedure of choice

In United States v. Classic, this Court decided that a

direct primary election is subject to federal control under

Article I “ where the state law has made the primary an

integral part of the procedure of choice’ ’. 2 The Court

pointed out that these constitutional provisions do not cease

to be applicable when a state “ changes the mode of choice

from a single step, a general election to two, the first of

which is a choice at a primary of those candidates from

whom, as a second step, the representative in Congress is

to be chosen at the election’ ’. 3 In another formulation of

the same principle the Court said “ that the authority of

Congress . . . includes the authority to regulate primary

elections when, as in this case, they are a step in the exer

cise by the people of their choice of representatives in Con

gress” . 4 To determine the applicability of the stated prin

ciple in the Classic case, this Court considered the statutes

of Louisiana concerning direct primary elections. While

the Court did not in terms indicate which statutory pro

1 United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. at p. 318.

2 313 U. S. at p. 318.

3 313 U. S. at pp. 316-317.

4 313 U. S. at p. 317.

13

visions were of greatest significance in establishing the pri

mary as part of the procedure of choice, the opinion does

specify the two decisive types of state action from which

this consequence had resulted; namely, (1) “ setting up

machinery for the effective choice of party candidates” ;

and, (2) eliminating or seriously restricting “ the candidacy

at the general election of all those who are defeated at the

primary” .1

Comparison of the Texas and Louisiana statutes demon

strates that the legislatures of both states have taken the

same type of action.2

In Louisiana all political parties casting five per cent,

or more of the total votes at the preceding elections are re

quired to nominate by direct primary election (Louisiana

Act No. 46, Regular Session, 1940, Sections 1 and 3). In

Texas all political parties casting 100,000 or more votes at

the last general election are required by statute to nominate

by direct primary election. (Vernon’s Revised Civil Stat

utes, Article 3101.) It is agreed by both parties that: “ At

all times material herein the only state-wide primaries held

in Texas have been for nominees of the Democratic Party”

(R. 72).

v

Texas eliminates or restricts the candidacy of persons

other than primary victors to a greater extent than does

Louisiana. The Texas law provides restrictions equivalent

to those in Louisiana.3 In addition the Texas law requires

‘ 313U . S. at p. 311.

2 See Comparative Tables of Louisiana and Texas election statutes

in Petitioner’s Appendices filed herein under separate cover.

3 Candidacy at the general election by means of independent nom

inating petition is restricted by the pledge required by statute of all

persons participating in primary elections and the further statutory

provision that persons participating in primary elections in which a

candidate is chosen for office may not sign a petition in favor of an

other’s nomination to said office (Article 3160).

14

that all party or organization candidates for Senator must

be chosen at a primary election, and goes so far in making

this restriction explicit as to preclude any candidates de

feated in a senatorial primary from running as an inde

pendent or non-partisan candidate in the general election.1

It is submitted that the foregoing are controlling factors

sufficient in themselves to make a primary election an inte

gral part of “ the procedure of choice” . Other statutory

provisions may be relevant but they are not decisive. A

large number of such subsidiary items appearing in both

the Texas and Louisiana statutes are assembled for the

purpose of comparison in parallel columns in Petitioner’s

Appendices. Only one of these cumulative circumstances

appears in the Louisiana statutes but not in the Texas stat

utes. In Louisiana the State collects a fee from all candi

dates participating in primary elections and thereafter con

ducts the primary at its own expense, while in Texas, the

statutes require the payment of certain prescribed fees by

candidates to the Executive Committees of the Democratic

Party to be used for the purpose of paying certain of the

expenses of said primary.2 In Texas many of the expenses

of the primary are paid in their entirety and directly by the

1 Vernon’s Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, Arts. 3090, 3096.

2 These funds contributed by candidates are considered a trust

fund solely for the purpose of paying of certain expenses for the pri

mary election and cannot either be appropriated by the Democratic

party or used for any purpose other than those purposes specifically

set out in the primary election statutes. Kaufman et al. v. Parker, 99

S. W . (2d) 1074 (1936); Small v. Parker, 119 S. W . (2d) 609

(1938).

15

state.1 However, this factoi*, in the Texas scheme does not

make the primary either more or less a part of the pro

cedure of choice. It does not change the effectiveness of the

primary in eliminating candidates, nor does it make pri

maries more or less mandatory or more or less completely

defined by law. Thus tested by the criteria set up by this

Court in the Classic case, this factor is in no sense con

trolling.

1 Pursuant to Article 2975 of the Revised Statutes of Texas the

County Collector of Taxes of Harris County, Texas, prepared a list

of qualified voters of said county who paid their poll tax prior to Jan

uary 31, 1940. Pursuant to Article 3121 of the Revised Statutes of

Texas, the County Collector for Harris County, Texas, delivered a

copy of this list to the defendants in their official capacities as Judges

of Primary Elections, to be used by them in determining the qualifi

cations of voters in said primary election. The expenses for the list

ing of qualified electors and the furnishing of these lists in the primary

elections are paid for by the State of Texas and Harris County; pur

suant to statute as follows:

“ The tax collector shall be paid fifteen cents for each poll

tax receipt and certificate of exemption issued by him to be

paid pro rata by the State and County in proportion to the

amount of poll tax received by each, which amount shall include

his compensation for administering oaths, furnishing lists of

qualified voters in election precincts for use in all general and

primary elections and primary conventions where desired. . . .”

(Article 2994.)

Pursuant to Article 3120 of the Revised Statutes of Texas, voting

booths, ballot boxes, and guard rails prepared for general elections

may be used for primary elections.

Pursuant to Article 2956 of the Revised Statutes of Texas, the

County Clerk of Harris County, Texas, is authorized and required

to receive absentee ballots for voting in the primary elections.

Pursuant to Article 3128 of the Revised Statutes of Texas, the

County Clerk is required to cause the names of the candidates who

have been nominated to be printed in some newspaper published in

the County and to post a list of such names in at least five public

places in the county, one of which shall be upon the courthouse door.

16

2. In Texas as in Louisiana the

Democratic primary in f a c t

“ effectively controls the choice”

of Senators and Representatives.

In United States v. Classic, supra, this Court decided

that “ where in fact the primary effectively controls the

choice, the right of the elector to have his ballot counted at

the primary” is protected by the Constitution. In that

case, an allegation that selection in the Democratic primary

in Louisiana was decisive of election to Congress was ad

mitted by demurrer to the indictment.

In the present case, it was alleged by the petitioner in

his complaint and demonstrated by a summary of election

statistics appended thereto that nominees of the Demo

cratic Party have been elected in all major elections in

Texas with but two exceptions since 1859 (R. 9, 29-59).

Thereafter, by stipulation of the parties duly incorporated

in the trial record, it was established as a fact that “ since

1859 all Democratic nominees for Congress, Senate and

Governor, have been elected in Texas, with two exceptions”

(R. 72). In his trial findings the District Judge stated that

“ the facts in detail have been stipulated, but it seems only

necessary to refer to the Stipulations and to make them a

part thereof” (R. 81 )J

As a matter of fact, in 1940 when petitioner tried to vote

the only opportunity for any Texas voter to exercise his

choice for United States Senator was in the Democratic 1

1 The full import of this is made clearer upon consideration of the

fact that during this period two senators have been elected each six

years, 21 members of United States House of Representatives have

been elected every two years, and a governor elected every two years.

The fact that during this period of more than eighty years there have

only been two instances of election of candidates other than those of

the Democratic Party demonstrates clearly that nomination at the

Democratic primary in Texas is tantamount to election.

17

primary election. It was the only primary election held in

1940 (R. 72). The figures for the 1940 general election in

Texas show the following vote for United States Senator:

Democrat 978,095 and Republican 59,34c.1

The Texas Court of Civil Appeals has pointed out that

it is “ a matter of common knowledge in this state that a

Democratic primary election, held in accordance with our

statutes, is virtually decisive of the question as to who shall

be elected at the general election” .1 2

It is adequately established in this record that in Texas,

as was the case in Louisiana, the Democratic primary in

fact “ effectively controls the choice” . The legal conse

quence of this, under the Classic case, is that the right to

vote in Texas primary elections is secured by the Consti

tution.

C. The respondents herein are subject to the con

trolling federal statutes.

Section 31 of Title 8 of the United States Code declares

the federal right of otherwise qualified electors to vote at

1 Congressional Directory (1943), p. 250.

2 State v. Meharg, 287 S. W . 670, 672 (1926). One of the major

reasons for the development of the primary election was that in “ the

South, where nomination by the dominant party meant election, it

was obvious that the will of the electorate would not be expressed

at all, unless it was expressed at the primary” . Charles Evans

H ughes, The Fate of the Direct Primary, 10 National Municipal

Review, 23, 24. See also: H asbrouck, Party Government in the

House of Representatives (1927), 172, 176, 177; Merriam and

O veracker, Primary Elections (1928), 267-269.

On the great decrease in the vote cast in the general election from

that cast at the primary in the “one-party” areas of the country, see

George C. Stoney, Suffrage in the South, 29 Survey Graphic 163,

164 (1940). In Louisiana there were 540,370 ballots cast in the

1936 Congressional primaries, as against 329,685 in the general elec

tion. In the 1938 Texas primaries, 34.5% of the adults voted, while

in the general election the figure dwindled to 15%.

18

all elections without distinction of race or color.1 It is ad

mitted that respondents prevented petitioner from voting

because of his race and color. Sub-division 11 of Section 41

of Title 28 of the United States Code 2 gives the District

Court jurisdiction of all suits to enforce rights of citizens of

the United States to vote in the several states.3 Similarly

Section 400 of Title 28 conferring jurisdiction over pro

ceedings for a declaratory judgment contains no limitation

significant for present purposes as to the person against

whom such proceedings may be brought. Thus it is neces

sary only that the petitioner show that the respondents are

persons who have in fact infringed the right which he as

serts, and it is not necessary that he shows that respondents

acted under color of any state law.

It is only under Section 43 of Title 8 and under Sub

division 14 of Section 41 of Title 28 that a question arises

whether the respondents acted “ under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of any state” . The

1 See: Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915); Myers v.

Anderson ( supra) ; Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927) ; Nixon

v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932).

2 “ The district courts shall have original jurisdiction. . . .

“ Eleventh. Of all suits brought by any person to recover

damages for any injury to his person or property on account

of any act done by him, under any law of the United States,

for the protection or collection of any of the revenues thereof,

or to enforce the right of citizens of the United States to vote

in the several States.”

3 Section 31 of Title 8 is codified from Section 1 of the Act of

May 31, 1870 (16 Stat. 140) which was amended by the Act of Feb

ruary 28, 1871 (16 Stat. 433). Section 15 of this amended statute

provided that the Circuit Courts of the United States should have

jurisdiction of all cases in law and equity arising under the original

and amended acts. By Act of March 7, 1911 (36 Stat. 1092) the

jurisdiction over these actions was transferred to the District Courts

o f the United States. This section has now become Section 41 (11)

of Title 28 of the United States Code.

19

facts show that they did so act. It is the State of Texas

which, by its election laws, creates, requires, regulates and

controls the direct primary election as an integral part of

the election machinery in that state. It is the statutes of

Texas which require the appointment of primary election

judges and prescribe the qualifications and disqualifications

for such office, which are the same as the qualifications and

disqualifications for judges of general elections. (Vernon’s

Revised Statutes, Articles 3104, 2930, 2940.) The statutes

of Texas prescribe in minute detail the powers of primary

election judges, which are likewise the same as those of

general election judges. Specifically, respondents as such

primary election judges were under statutory mandate to

administer oaths, to preserve order, and to appoint special

officers to assist in the maintenance of order (Art. 3105).

They were required to compel the observance of the law

prohibiting loitering and electioneering near the polling

places and to arrest any person engaged in conveying voters

to the polls in carriages or other conveyances except as

permitted by statute (Art. 3105). All of these significant

police powers of the respondents as election judges are

derived solely from and exercised under the sovereign

authority of the State of Texas. It is particularly signifi

cant that respondents as election judges are required by

Article 3104 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas to take

an oath which is the same oath that is required of officials

serving in general elections and, moreover, Articles 217 and

231 of the Penal Code of the State of Texas make it a crim

inal offense subject to fine for any election judge to refuse

to deliver a ballot to or receive the vote of a qualified

elector in a primary election.

It is the usual procedure in Harris County, Texas, for

the same individuals who are appointed election judges

in the general elections also to serve as election judges in

20

the Democratic primary elections (R. 74). The respondents

conducted the Democratic primary elections of 1940 in the

same manner as the general elections and in conformance

with the statutes of the State of Texas (R. 74, 103-108).

With their offices thus created and defined by the State

and with their duty to receive and count ballots imposed by

statute, respondents so exercised their official function

under the laws of Texas as to deny petitioner the right to

vote. Thus the action of which petitioner complains comes

squarely within the test of action under color of state law

as formulated in United States v. Classic: “ misuse of

power, possessed by virtue of state law and made possible

only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority

of state law, is action taken ‘ under color’ of state law” .1

Respondents “ possessed” their “ power . . . by virtue of

state law” and their rejection of the petitioner’s ballot was

“ made possible only because [they were] clothed with the

authority of state law” . Controlling effect should be

given here as in the Classic case, to the relationship of the

State to the enterprise in which the primary election judges

were engaged. Once the state’s relationship to the enterprise

in which the offending persons are engaged is established, it

is immaterial what sanction, if any, is claimed for a par

ticular act done in performing an official function. Indeed,

1 313 U. S. at 326.

Cf. E x Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 346 (1879); Home Tele

phone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278 (1913) ;

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307 U. S. 469, 507,

519 (1939).

21

if the matter of such sanction were controlling, the Court

would necessarily have concluded in the Classic case that

the alleged election frauds were not “ under color o f” state

law because they were not authorized by the State.1 2

It is submitted that this reasoning should have been but

was not adopted when the status of Texas primary elections

was considered by this Court in Grovey v. Townsend? In

that case, the conduct of election judges was considered to

be private rather than State action because the act com

plained of—the exclusion of Negroes from voting—was not

authorized by the State. Under the correct approach of the

Classic case, authority for the particular act is immaterial

so long as the relationship of the State to the enterprise in

which the election judges are engaged is such as to bring

their whole course of official conduct “ under color of state

law” . This conflict between the theories of United States

v. Classic and Grovey v. Townsend should now be resolved

in accordance with the sound reasoning of the Classic case.

1 In an unbroken line of decisions this Court has held that an

officer of a state finds no shield from enforcement of federal consti

tutional and statutory limitations in the fact that the state law did not

authorize the acts complained of. Even prohibition of misconduct by

state statute does not operate to limit the federal authority to enforce

constitutional restrictions as against state officers. See: Raymond v.

Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20 (1907) ; Siler v. Louisville and

Nashville R. R., 213 U. S. 175 (1909) ; Des Moines v. Des Moines

City Ry., 214 U. S. 179 (1909); Home Telephone and Telegraph Co.

v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278 (1913); Iowa-Des Moines National

Bank v. Bennett, 284 U. S. 239 (1931). These cases must be taken

as overruling the earlier and inconsistent Barney v. City of New York,

193 U. S. 430 (1904).

2295 U. S. 45 (1935).

22

II.

The action of respondents herein was in violation of

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

The refusal of the respondents to permit petitioner to

vote in the Democratic primary in Texas because of race or

color also violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States. In the State

of Texas, where the state law has made the primary an in

tegral part of the procedure of choice and where in fact the

primary effectively controls the choice, the prohibitions of

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments apply to pri

mary elections to the same extent as in the case of general

elections.

A. The conduct of respondents in denying peti

tioner a ballot to vote in the Texas Democratic

primary was state action.

In the Classic case this Court indicated that in primaries

which are an integral part of the election machinery of a

state the protection afforded by the Fourteenth Amendment

to Negro voters is even clearer than the more generalized

protection of Article I. Interpreting Section 19 of the

Criminal Code the Court stated: “ It does not avail to at

tempt to distinguish the protection afforded by Sec. 1 of the

Civil Rights Act of 1871, 8 U. S. C. A. Sec. 43, to the right

to participate in primary as well as general elections,

secured to all citizens by the Constitution, . . . on the

ground that in those cases the injured citizens were Negroes

whose rights were clearly protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment” .1

1313 U. S. at p. 323.

23

The action of the respondents herein in refusing peti

tioner a ballot to vote in the Texas Democratic primary was

“ state action’ ’ within the meaning of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the same extent that the action

of the defendants in the Classic case was “ under color o f ”

state law within the meaning of Section 20 of the United

States Code. In the Classic case this Court after finding

that the Democratic primary in Louisiana was “ an integral

part of the election machinery” of that state concluded that

the election officials who refused to count the ballots of

qualified electors in the primary elections were rightfully

charged with violation not only of Section 19 of the Criminal

Code, prohibiting such action by private individuals, but

also Section 20, prohibiting such action by persons acting

“ under color o f” state law. This conclusion was reached

by applying the principle that: “ misuse of power, possessed

by virtue of state law and made possible only because the

wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law, is

action ‘ under color o f ’ state law” .1 It has been established

in preceding sections of this brief that there is no essential

difference between the legal character of the primaries in

Louisiana and Texas and that respondent election judges

acted “ under color o f” state law just as did the Louisiana

election judges in the Classic case (pp. 12-21). Where con

duct of the individual is so related to the state as to be

“ under color o f” state law it necessarily follows that such

conduct is likewise state action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.2

The District Court conceded that the right to vote in a

primary election which is “ by law made an integral part

of the election machinery” would be a right protected by the

1 313 U. S. 299, 326.

2 Cf. E x parte Virginia, supra; Home Telephone & Telegraph

Co. v. Los Angeles, supra; Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organ

ization, supra.

24

Federal Constitution. The District Judge, however, con

sidered the decision of this Court in Grovey v. Toumsend

as controlling and that he must therefore “ follow Grovey v.

Townsend and render judgment for defendants” (E. 85).

The United States Circuit Court of Appeals also considered

the decision in Grovey v. Townsend as controlling and con

cluded that “ we may not overrule it. On its authority the

judgment is affirmed” (R. 151).

In thus following the Grovey case rather than the Classic

case, the District Court and the Circuit Court of Appeals

made a choice between inconsistent methods of determining

whether conduct in primary elections is public or private

action. It is respectfully submitted that the ratio decidendi

of the Classic case rather than of the Grovey case should be

followed.

B. New matter disclosed in the present record

destroys the factual basis for the decision in

Grovey v. Townsend.

The record before this Court in Grovey v. Townsend,

supra, failed to reveal or present facts essential to an ade

quate legal appraisal of the so-called “ white primary.”

That decision had no proper basis in the actualities of the

Texas system, and should be re-examined in the light of

facts now revealed for the first time in the present record.

In Grovey v. Townsend, supra, this Court decided that

the method of excluding Negroes from voting in the Texas

Democratic primary elections did not involve such state

action as is comprehended by the 14th and 15th Amend

ments. Because the exclusionary practice was predicated

upon a resolution of the State Democratic Convention, and

in the light of the record then at hand, this Court failed to

find any decisive interposition of state force in the primary

election.

25

Grovey v. Townsend, supra, was decided upon demurrer

to a petition for damages filed in Justice Court, Precinct

No. 1, Position No. 2, Harris County, Texas. That record

provided no factual picture of the organization and opera

tion of the so-called Democratic Party of Texas and per

mitted the assumption that the party had the basic struc

ture and defined membership which are characteristic of an

organized voluntary association. Moreover, on that record,

this Court assumed that the privilege of voting in the Demo

cratic primary election was an incident of party member

ship and restricted to members of an organized voluntary

association called the “ Democratic Party.” 1 The present

record and the following analysis will show that these sup

posed facts, vital to the decision in Grovey v. Townsend,

supra, did not exist.

The problem in Grovey v. Townsend, supra, as in the

present case, was the determination and evaluation of the

participation of government on the one hand, and the so-

called “ Democratic party” on the other hand, in Texas

primary elections with a view to deciding whether the con

duct of these elections was, in legal contemplation, a gov

ernmental function subject to the restraints of the 14th and

15th Amendments or a private enterprise not so restricted.

The complaint described in detail the state statutes creat

ing, requiring, regulating, and controlling the conduct of

primary elections in Texas. These circumstances were

summarized in the opinion of this Court (295 U. S. 45, 49-

50).

1 “ While it is true that Texas has by its laws elaborately provided

for the expression of party preferences as to nominees, has required

that preference to be expressed in a certain form of voting, and has

attempted in minute detail to protect the suffrage of the members of

the organization against fraud, it is equally true that the primary is a

party primary . . . ” (295 U. S. 45, 50).

26

In contrast, the nature, organization and functioning of

the Democratic Party were nowhere adequately described.

Instead, the Court found it necessary to rely upon a general

conclusion of the Supreme Court of Texas in Bell v. Hill,1

that the Democratic Party of Texas is a voluntary associa

tion for political purposes, functioning as such in determin

ing its membership and in controlling the privilege of vot

ing in its primaries.2

This Court was not bound to accept the conclusion of the

Supreme Court of Texas as to the legal character of the

primary election and the Democratic Party in Texas; for it

is well settled that where the claim of a constitutional right

is involved, this Court will review the record and find the

facts independently of the state court.3 This Court should

1 123 Tex. 531, 74 S. W . (2d) 113 (1934). ^

2 Bell v. Hill was decided by the Supreme Court of Texas on an

original motion for leave to file a petition for mandamus. As in the

Grovey case there were no facts presented or evidence of either the

“ Democratic Party” or the actual functioning of the election ma

chinery.

3 In Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932), the Court decided

for itself what duties counsel performed, in considering the question

of adequate representation by counsel appointed by the state court.

In Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940), the Court made

independent findings of fact as to the character of phonograph records

played by Jehovah’s Witnesses. In Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587

(1935), the Court weighed evidence showing that Negroes had been

excluded from jury service by reason of race prejudice, against evi

dence that they had been excluded for other reasons, and held that

the former outweighed the latter.

Accord: Avery v. Alabama, 308 U. S. 444 (1940).

In Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, at p. 130 (1940), this Court

said:

“ But both the trial court and the Texas Criminal Court of

Appeals were of opinion that the evidence failed to support the

charge of racial discrimination. For that reason the Appellate

Court approved the trial court’s action in denying petitioner’s

timely motion to quash the indictment. But the question

decided rested upon a charge of denial of equal protection, a

basic right protected by the Federal Constitution. And it is

therefore our responsibility to appraise the evidence as it re

lates to this constitutional right.” (Italics supplied.)

Accord: Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 (1942).

27

have reserved to itself the right to pass upon the mixed

question of law and fact involved in the decision whether

the conduct of primary election officials in Texas constituted

state action.1

Now, for the first time this Court has significant facts

before it which permit an independent examination of the

“ party” and its functioning and a meaningful comparison

of the roles of state and party in Texas primary elections.

The present record shows that in Texas the Democratic

primary is not, as was assumed in Grovey v. Townsend,

supra, an election at which the members of an organized

voluntary political association choose their candidates for

public office.

1 In Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, at p. 358 (1939), the

Court said:

“ In our consideration of the facts the conclusions reached

by the Supreme Court of Louisiana are entitled to great respect.

Yet, when a claim is properly asserted— as in this case—that

a citizen whose life is at stake has been denied the equal pro

tection of his country’s laws on account of his race, it becomes

our solemn duty to make independent inquiry and determina

tion of the disputed facts— for equal protection to all is the

basic principle upon which justice under law rests.”

In Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, at p. 590 (1935), Mr. Chief

Justice Hughes, in his opinion for the unanimous Court, said:

“ When a federal right has been specially set up and claimed

in a state court, it is our province to inquire not merely

whether it was denied in express terms but also whether it

was denied in substance and effect. If this requires an exam

ination of evidence, that examination must be made. Other

wise, review by this Court would fail of its purpose in safe

guarding constitutional rights. Thus, whenever a conclusion

of law of a state court as to a federal right and findings of

fact are so intermingled that the latter control the former, it is

incumbent upon us to analyze the facts in order that the appro

priate enforcement of the federal right may be assured.”

A ccord: Great Northern Railway v. Washington, 300

U. S. 154 (1937). United Gas Co. v. Texas,'303 U. S. 123 (1937),

Cf. Mason Co. v. Tax Commission, 302 U. S. 186 (1937).

2 8

First, any white elector, whether he considers himself

Democrat, Republican, Communist, Socialist, or non-parti

san, may' vote in the “ Democratic” primary. The testi

mony of the respondent Allwright is positive on this point.

“ Q. Mr. Allwright, when a white person comes

into the polling place during the primary election of

1940 and asks for a ballot to vote do you ever ask

them what party they belong to? A. No, we never

ask them.

Q. As a matter of fact, if a white elector comes

into the polling place to vote in the Democratic pri

mary election, he is given a ballot to vote; is that

correct? A. Right.

Q. And Negroes are not permitted to vote in the

primary election? A. They don’t vote in the pri

mary.

Q. But any white person that is qualified; regard

less of what party they belong to, they can vote? A.

That is right.

Q. And you do let them vote? A. Yes” (R. 106).

Second, the Democratic party of Texas has no identified

membership and no structure which would make its mem

bership determinable. Under these circumstances, it is im

possible to restrict voting in the primary election to “ party

members.” The testimony of E. B. Germany, Chairman

of the Democratic State Executive Committee, illustrates

this point (R. 119).

Third, the Democratic party of Texas is not organized.

Officials claiming to represent the party testified positively

that the party has no constitution nor by-laws (R. 146), and

is a “ loose jointed organization” (R. 126). No minutes or

records of the periodic party conventions are preserved

(R. 131). The party has no officers between conventions

29

(R. 125, 143). Beyond the lack of organic party law, there

is no formulated body of party doctrine. No resolutions of

the state conventions are preserved (R. 137). Even the

resolution upon which the exclusion of Negroes frorq the

primaries is predicated is not a matter of record and has

no existence as a document (R. 136). At the trial, the al

leged contents of the resolution were proved, over the objec

tion of the petitioner, by the recollection of a witness who

testified that he had introduced such a resolution, and was

present when it was adopted (R. 138).

The only rules and regulations governing the Demo

cratic Party and the Democratic primary elections are the

election laws of the State of Texas (R. 133-134). This

startling state of affairs is perhaps the most striking evi

dence of a one-party political system where for all prac

tical purposes the Democratic Party is co-extensive with

the body politic and, hence, needs no private organization

to distinguish it from other parties.

In such circumstances the legal character of the pri

mary elections, and the status of those who conduct them,

can be derived only from the one organized agency, which

creates, requires, regulates and controls these elections,

namely, the State of Texas. The factual material supplied

in this record, but not available in the record of Grovey v.

Townsend, supra, compels this conclusion. Inadequately

informed, this Court sanctioned the practical disenfran

chisement of 540,565 adult Negro citizens, 11.88% of all

adult citizens of Texas.1 Grovey v. Townsend should be

overruled.

1 United States Census (1940). (Figures include native born and

naturalized adult citizens.)

30

Conclusion.

Wherefore, it is respectfully submitted that the

judgment of the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood Marshall,

New York, N. Y.,

W illiam H. H astie,

Washington, D. C.,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W. J. D urham ,

Sherman Texas,

W. R obert M ing, J r .,

Chicago, 111.,

George M. J ohnson,

Berkeley, Calif.,

L eon A. R ansom,

Columbus, Ohio,

Carter W esley,

Houston, Texas,

M ilton R. K onvitz,

Newark, N. J.,

Of Counsel.

L a w y e r s P ress, I n c ., 165 William St., N. Y. C.; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300