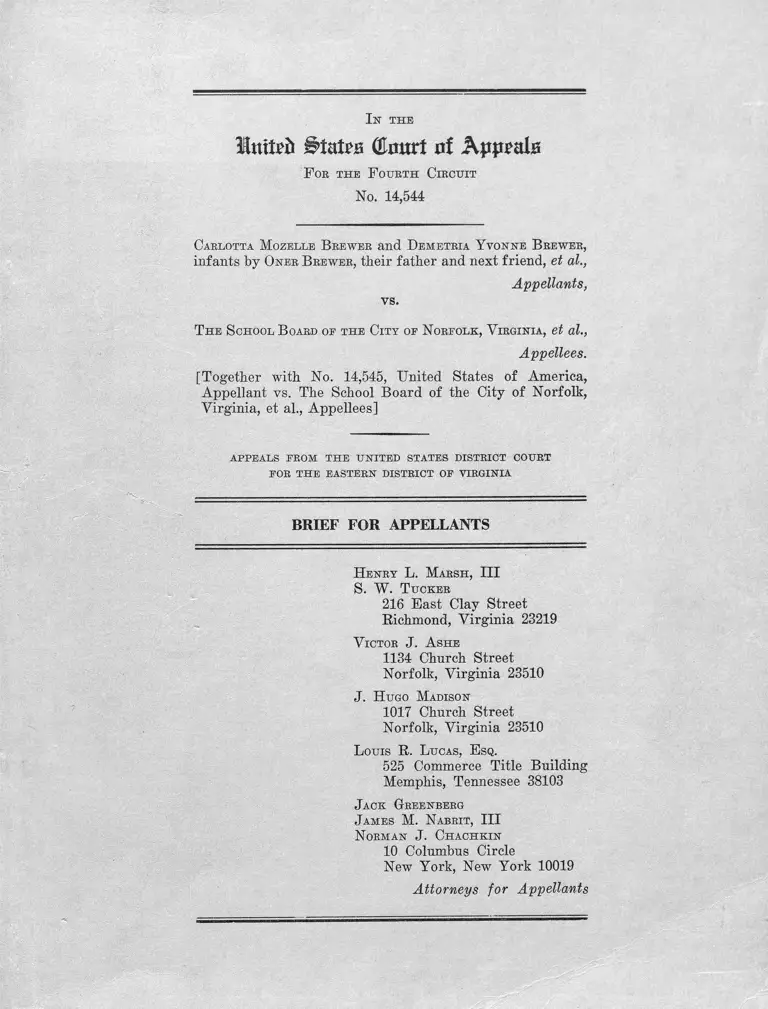

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia Brief for Appellants; Beckett v. School Board of the City of Norfolk Memorandum and District Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 19, 1969 - December 30, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia Brief for Appellants; Beckett v. School Board of the City of Norfolk Memorandum and District Court Opinion, 1969. 56c43357-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/feca6452-59e3-4b97-a2fc-18e76c8a4768/brewer-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-virginia-brief-for-appellants-beckett-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-memorandum-and-district-court-opinion. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Itttfrii #tate (Emirt nf Appeals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 14,544

Carlotta Mozelle B rewer and Demetria Y vonne B rewer,

infants by Oner B rewer, their father and next friend, et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

T he School B oard oe the City op Norfolk, V irginia, et al.,

Appellees.

[Together with No. 14,545, United States of America,

Appellant vs. The School Board of the City of Norfolk,

Virginia, et al., Appellees]

a p pe a ls pr o m t h e u n it e d states d ist r ic t co urt

POR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OP VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Henry L. Marsh, III

S. W . T ucker

216 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

V ictor J. A she

1134 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23510

J. H ugo Madison

1017 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23510

L ouis R. Lucas, E sq.

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities.................................... ii

Issues Presented for Review. . . . ................... 1

Statement. ................................................2

The Norfolk School System in 1970 ................ 6

Residential Racial Discrimination ............... 9

The Board's Plan.................................... 18

The Alternative Plan . . 2 6

ARGUMENT . . . . . 36

Introduction.......... 37

I Norfolk's Plan To Assign Black Students

To All-Black Schools On The Basis Of

Their Race, Which The District Court

Approved, Violates The Constitution Of

The united States And Cannot Be justified

On Grounds Of Educational policy . . . . . . 39

II This Court Should permit No Further Delay

In Eliminating Norfolk's Dual School System

But Should Order The Implementation Of The

Alternative plan In This Record Which Will

Make All Of Norfolk's Schools Unitary Schools 55

Conclusion . . . . . ................................... 59

Page

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S.

19 (1969) .......................................

Andrews v. City of Monroe, No. 29358 (5th Cir.,

April 2 3, ~ 1970) .................................

Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 148 F.

Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.), aff'd sub nom. School

Bd. of City of Newport News v. Adkins, 246

F .2d 325 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 355 U.S. 855

(1957)................. .........................

" v. " , 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 336 (E.D. Va.),

aff'd sub nom. School Bd. of City of Newport

News v. Adkins, 246 F.2d 325 (4th Cir.), cert,

denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957) ...................

" v.

" V.

" V.

Va.) , a i

" v . " , 181 F. Supp. 870 (E.D. Va. 1959),

aff'd sub nom. Hill v. School Bd. of City of

Norfolk, 282 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960) .........

" v. " , 185 F. Supp. 459 (E.D. Va. 1959),

aff'd 281 F .2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960). . . . . . .

" v. " , 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1315 (E.D. Va.

1964), vacated and remanded sub nom. Brewer v.

School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 349 F.2d 414

(4th Cir. 1965) ................................

" v. " , 11 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1278 (E.D.

Va. 1 9 6 6 ) .................................... .

" v. " , 269 F. Supp. 118 (E.D. Va. 1967),

rev'd sub nom. Brewer v. School Bd. of City of

Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968)........ •

" v . " , 302 F. Supp. 18 (E.D. Va. 1969) .

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964).............

20, 37, 44, 55

50

, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 945 (1958) . .

, 2 Race Re 1 <» L. Rep. 955 (1958) . .

, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1155 (E.D.

d 260 F. 2d 18 (4th Cir . 1958) . . .

4

4

4

4

6

6 , 48

47

xi

page

Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968).............................. .. 6 , 49

Brooks v. County School Bd. of Arlington County,

324 • F . 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963). .................... 50-51

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ........ 2, 36, 37, 38,

53, 54

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) . ............. 46

Cato v. Parham, 297 F. Supp. 403 (E.D. Ark. 1969). . . 50

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) . . . . . ......... 39

Coppedge v. Franklin County Bd. of Educ., 404 F . 2d

1177 (4th Cir. 1968). ............................. 39

Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac, Civ. No.

32392 (E.D. Mich., February 17, 1 9 7 0 ) ........... 49

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ......... 50

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), aff'd 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir.), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967)......... 46

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, Civ. No.

9452 (W.D. Okla., Aug. 8 , 1969), aff'd 396

U.S. 296 (1969) ................................... 50

Evans v. Abney, 396 U.S. 435 (1970) . . . . . . . . . . 17

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969). . 43

Goins v. County School Bd. of Grayson County, 186 F.

Supp. 753 (W.D. Va. 1960), stay denied, 282

F . 2d 343 (4th Cir. 1960).......................... 51

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968)................. ................. 37, 44, 52

Haney v. County Bd, of Educ, of Sevier County, 410

F . 2d 920 (8 th Cir. 1969).......................... 50

Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E.2d 636 (1959). . 5

Cases (continued)

iii

Page

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F .2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396

U.S. 940 (1969) . ................................. 46, 50

Holland v. Board of Public' Instruction of Palm Beach

County, 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958)............. 46

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va. 1959). . . 5

James v. Duckworth, 170 F. Supp. 342 (E.D. Va.),

aff'd 267 F.2d 224 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

361 U.S. 835 (1959)............................ . 5

Kemp v. Beasley, No. 19782 (8th Cir., March 17, 1970). 45

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 303 F. Supp.

279 (D. Colo.), stay vacated, 396 U.S. 1215

(1969)(Mr. Justice Brennan, in Chambers)........ 50

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 (1968)......................................... 37, 39

Nesbit v. Statesville city Bd. of Educ., No. 13,229

(4th Cir., Dec. 2, 1 969)......................... 23, 44, 55, 56

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 2 ) ........... 51

School Bd. of Warren County v. Kilby, 259 F.2d

497 (4th Cir. 1 9 5 8 ) .............................. 51

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)................. 46, 48

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., Civ. No.

68-1438-R (C.D. Cal., March 12, 1970) ........... 50

Stanley v. Darlington County School Dist., No.

13,904 (4th Cir., Jan. 16, 1970)................. 44, 55

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 300

F. Supp. 1358 (W.D.N.C. 1 9 6 9 ) ................... 4 9 , 5 0 , 51

v - " / Civ..No. 1974 (W.D.N.C., Dec. 1, 1969)44

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

No. 28880 (5th Cir., March 9, 1 9 7 0 ) ............. 56

United States v. Greenwood Municipal seprate School

Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969)............. 45, 50

Cases (continued)

IV

Page

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966)........... 49

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

Dist., 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 1011 (1969). . ............................ 44, 50

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp.

786 (N.D. 111.), aff'd 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1 9 6 8 ) ............................................. 49

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., No. 29237 (5th

Cir., March 6 , 1970). ...................... .. 50

Walker v. County School Bd. of Brunswick County, 413

F.2d 53 (4th Cir. 1969) (per curiam)............. 39

Other Authorities

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors (1955) . . . . . ......... 48

Pettigrew, Thomas F., De Facto Segregation, Southern

Style, integrated Education, June-July, 1967. . . 13

Racial isolation in the Public Schools, A Report

of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1967) . . 47, 48

Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (1948)........................ 48

Weinberg, Race and Place -- A Legal History of the

Neighborhood School (U.S. Gov't Printing Office,

Catalog No. FS 5.238:38005, 1967) ............... 51

Cases (continued)

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 14,544

CARLOTTA MOZELLE BREWER and DEMETRIA YVONNE

BREWER, infants by ONER BREWER, their

father and next friend, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF NORFOLK,

VIRGINIA, et al.,

Appellees.

[Together with No. 14,545, United States of America, Appellant

vs. The School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, et al.,

Appellees]

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented for Review

1. Whether Norfolk may avoid its immediate affirmative duty

to eliminate root and branch its state —imposed dual school system

by adopting or applying any policy, educational theory or device

which has the effect of perpetuating racially identifiable schools.

2. Whether this Court should order implementation of the

alternative presented by appellant's expert witness which all

parties agreed was the best plan to totally desegregate the school

system.

Statement

The Norfolk school system has affirmatively acted to segregate

77% of its black elementary schoolchildren in all-black schools, in

the context of what purports to be a "desegregation plan." Stripped

of rubric, artifice and rationalization, the plan adopts white

hostility to integration as a predicate and justification to limit.

to a "tolerable" number the attendance of black children at white

1/, 2/

schools (28 Tr. 39-40; Principle X, DX 1, 10/69).

In this fourteen-year-old litigation to desegregate the Norfolk,

Virginia public schools, this court has repeatedly been required to

direct further action by the district court. Nearly every conceivable

tactic to delay, frustrate or avoid the mandate of Brown v. Board of

Educ,, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) has been raised by the defendants.

1/ Under this plan, 32 of Norfolk's 67 public schools will

enroll only students of one race. An additional seven schools

will enroll less than 10% minority students. See Table 1,

Appendix, infra.

2/ The following abbreviations will be used in citations in

this Brief: plaintiffs,' United States', and School Board's

exhibits (see Certificate of the Clerk on the Exhibits) will

be identified as PX, GX and DX, respectively, with the addition

of the date of the hearing, e.g., GX G-19, 4/69. The

transcripts of the hearings and the November 11, 1969 deposition

will be referred to by the volume numbers contained in the

Clerk's transmittal letter of April 10, 1970, Table of Contents

pp. 7-8. The proceedings in the spring of 1969 are recorded in

volumes XII-XX inclusive, and the proceedings in October-November,

1969 in volumes XXI-XXXI inclusive. Appellants have requested

that the Clerk mark these transcript volumes with corresponding

arabic numeral designations to facilitate their citation and

reference to them by the Court. Pleadings will be referred to

by date and title as listed in the Table of Contents, Clerk's

transmittal letter of April 10, 1970.

-2-

initially the school board claimed immunity from suit as an agency

of the Commonwealth of Virginia, which had not consented; it denied

any responsibility for pupil assignment during the era of the

Virginia placement Board; subsequently, it established its own

pupil placement apparatus with placement criteria similar to those

3/

contained in the voided state law. The Board has consistently

sought (and again seeks) to divert the courts' attention from the

lack of adequate results of its desegregation plans by putting in

issue so-called "principles" or theories which it adopted in each

instance to explain retention of its segregated system. Thus,

until 1963 the case was focused upon the validity and application,

by either the school board or the Virginia Pupil Placement Board, of

placement principles and standards by which individual applications

to transfer across racial lines were disposed of. Subsequent hearings

and appeals have involved the effect of the Norfolk choice within

zones" method of pupil assignment, faculty desegregation and school

3/ The obscene gauntlet which Negro students seeking to attend white

schools were forced to run included "interviews" conducted by

the Superintendent at which they were questioned as to their

"fitness" to attend "white" schools, achievement tests and

evaluations of their scores in relation to the scores at the

sending and receiving schools, family background (social class),

etc. Two examples of such interviews, test scores and

evaluations which illustrate the process have been included in

this record. Court Exhibit 12, 13,1959.

3

construction. The detailed history of this case is set out in

4/

a footnote.

4/ After the complaint was filed in 1956, all action was

deferred pending the holding of a planned special session of

the Virginia Legislature on the subject of school integration,

and then again pending the effective date of the "massive

resistance" legislation passed at the special session.

January 11, 1957, the district court denied the school board's

motion to dismiss, and on February 12, 1957, the district court

entered an injunction against the school board restraining it

from:

refusing, solely on account of

race or color, to admit to, or

enroll or educate in, any school

under their operation, control,

direction or supervision, directly

or indirectly, any child otherwise

qualified for admission to, and

enrollment and education in such

school.

Beckett- v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 148 F. Supp. 430,

2 Race Rel. L . Rep„ 336 (E.D. Va.), both aff1d sub nom.

School Bd. of City of Newport News v. Adkins, 246 F.2d 325

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957). However, all

proceedings were again stayed pending disposition of appeals

and petitions for certiorari. It was not until July, 1958

that the school board adopted pupil placement criteria and

procedures. The board thereupon denied all 151 applications

filed by black students to attend previously all-white

facilities during the 1958-59 school year. 2 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 945 (1958). The district court ordered the board to

reconsider and on August 29, 1958, the board announced that

seventeen of the transfer requests would be granted. 2

Race Rel.. L. Rep. 955 (1958). The board sought an additional

delay in admitting the seventeen black students, but the

district court denied it and this court affirmed. Beckett v.

School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1155 (E.D.

Va.), aff1d 260 F.2d 18 (4th Cir. 1958). On plaintiffs'

cross-appeal from the district court's refusal to order the

admission of the remaining 134 students, the matter was

remanded since the district court had indicated he would

consider separately the validity and application of the

criteria under which the applications were denied. The schools

to which the seventeen Negro students were assigned, however,

were closed pursuant to Virginia's "school closing" laws from

4

4/ (continued)

the fall of 1958 until February, 1959, when the laws

and similar Norfolk City ordinances were declared

unconstitutional in James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331

(E.D. Va. 1959)3-judge court); Harrison v. Day, 200

Va. 439, 10.6 S.E.2d 636 (1959); James v. Duckworth, 170

F. Supp. 342 (E.D. Va.), aff'd 267 F.2d 224 (4th Cir.),

cert. denied, 361 U.S. 835 (1959). At that time plaintiffs'

supplemental 3-judge court complaint was dismissed as moot,

and late in the 1958-59 school year, the district court

refused to overturn the board's denial of the 134 transfer

applications, holding its placement principles facially

constitutional. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk,

181 F. Supp. 870, 870-81 (E.D. Va. 1959)', aff'd sub nom. Hill

v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 282 F.2d 473 (4th Cir.

1960). The district court subsequently permitted the board

to assign pupils by these principles, although holding that

the board need not utilize the procedures of the Virginia

Pupil Placement Board in view of that agency's policy of

not granting any transfer requests. Beckett v. School Bd.

of City of Norfolk, 185 F. Supp. 459 (E.D. Va. 1959), aff'd

281 F.2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960). During 1961 and 1962, the

district court had occasion to review and overturn school

board denials of black students' transfer requests (unreported

opinions) although there was no across-the-board attack on

assignment procedures. However, when in 1963 the plaintiffs

filed a motion for further relief, the board discarded pupil

placement and proposed what has come to be known as the

"Norfolk choice" plan -- transfer between black and white

schools located within the same attendance area. This plan

was approved by the district court and on plaintiffs' appeal

this Court reversed and remanded for reconsideration in light

of its then recent decisions in this field. The district

court was specifically instructed to consider the legality or

propriety of superimposing a city-wide zone for all-black

Booker T. Washington High School on all other city high school

zones. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 9 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1315 (E.D. Va. 1964), vacated and remanded sub nom.

Brewer v. School Bd, of City of Norfolk, 349 F.2d 414 (4th Cir.

1965). Proceedings subsequent to that remand and negotiations

between the parties resulted in the entry of a consent order

on March 17, 1966, approving a new desegregation plan. Beckett

v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 11 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1278 (E.D.

Va. 1966). Under that plan, reluctantly approved by the district

court, there were multiple-school zones but at the high school

level, transfers between the three white high schools and Booker

T. Washington High were permitted only to facilitate integration.

The following year, completion of Lake Taylor High School

necessitated the filing of an amended plan by the school board,

proposing five high school zones, and allowing only Booker T.

Washington students to transfer to schools outside their zone

of residence. The district court required that transfer

privileges be extended to all high school students but rejected

5-

The Norfolk School System in 1970

The School Board of the City of Norfolk presently operates

5/

seventy-one regular schools within the corporate limits of Norfolk,

which are coterminus with the school district boundaries.

Geographically, the furthest extension of the city from north to

south is approximately 8-3/4 miles (DX 1-C, 10/69). The city is

bisected from southeast to northwest by Interstate Route 64, a

limited access highway, and the Chesterfield-Campostella bridge

areas near the small (black) portion of Norfolk south of the Eastern

4/ (continued)

plaintiffs' attacks upon the zone lines and upon the proposed

replacement of Booker T. Washington High School on the same

site. This Court reversed and remanded, directing the district

court to consider, with respect to both issues, whether

segregated neighborhood patterns in Norfolk resulted from

racial discrimination, of which the board was seeking advantage

in its zone lines. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk,

269 F. Supp. 118 (E.D. Va. 1967), rev'd sub nom. Brewer

v. School Bd. of city of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4tF~Cir7

1968). The district court found this Court's decision "vague

and confusing." 302 F. Supp. at 20. Negotiations between the

parties following the remand failed to produce agreement. As

an interim plan for 1969-70 the school board proposed zone line

changes between Lake Taylor and Booker T. Washington to increase

integration, and similar changes between Maury and Granby.

After hearings in the Spring of 1969, the district court approved

the interim plan for 1969-70. Beckett v. School Bd. of city of

Nor folk, 302 F. Supp. 18 (E.D. Va. 1969) . After extensive

hearings in the fall of 1969 on the long-range plan of

desegregation for 1970-71 and thereafter, which is the subject

of this appeal, the district court approved the school board's

submission on January 9, 1970.

5/ Excluding the facility serving children with cerebral palsy,

the vocational-technical school, and treating Sewells Point

Elementary and Sewells Point Annex as a single unit.

6

Branch, Elizabeth River, are linked to the Lake Taylor section

in the eastern part of the city by another limited access highway,

Interstate 264. Norfolk abuts the cities of Virginia Beach to the

east, Chesapeake to the south, Portsmouth to the west (across the

Southern and Western Branches of the Elizabeth River) and Hampton

and Newport News to the north (across Hampton Roads and Chesapeake

Bay) .

6/

The 1969-70 school enrollment was 56,603 -- 57.6% white and

42.4% black (DX 3,20, GX 3, 10/69). Assignments are based upon

geographic attendance zones at the high school level and free

choice within attendance zones in the elementary and junior high

schools, with the following results in 1969-70:

Grades Students Teachers

HIGH SCHOOLS: Served White Black White Black

Granby 9-12 2022 291 102 9

Norview 1 0 -1 2 2062 394 106 8

Maury 1 0 -1 2 926 1047 1001; 13

Lake Taylor 9-12 2220 220 104 8

7230 1952 412^ 38

Booker T. Washington 1 0 -1 2 7 2268 28 92

Total 7237 4220 440^ 130

(1 1 ,457) (570h)

6/ Regular enrollment exclusive of the school for children

with cerebral palsy and the vocational-technical school.

7

Grades Students Teachers

JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOLS: Served White Black White Black

Azalea Gardens, Lake

Taylor, Northside,

Norview* and Willard 7-9* 6387 558 284 30

Blair 7-9 651 759 64 12

Rosemont* 7-9* 41 409 10 14

Campostella 7-9 1 )Madison* 7-9* 1) 2994 41 124

Ruffner 7-9 1)

jacox 7-9 0 1183 13 61

Total 7082 5903 412 241

(1 2 ,985) (653)

(* Junior high schools marked with an asterisk have sixth grades

assigned from overcrowded elementary schools).

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS:

7/

During the 1969-70 school year, 50 of the 55 elementary

schools remained almost totally segregated, enrolling 90% or

greater majorities of one race. Seventeen elementary schools were

all-black (the 1970-71 plan projects an increase to 19 all-black

schools), and a total of 22 had fewer than 10% white pupils; there

were 8 all-white elementary schools (there will be 10 in 1970-71)

and a total of 28 had less than 10% black students. The remaining

five elementary schools enrolled but 8% of Norfolk's elementary

students. Thus, 92% of the 32,161 elementary students presently

attend almost totally segregated schools.

7/ There are 55 elementary schools not counting the cerebral

palsy center and treating Sewells Point Elementary and Annex

as a single unit.

8

The total elementary school teaching staff was 38% black

in 1969-70 but the combined faculties assigned to the 22 virtually

all-black elementary schools were 71% black, and the combined

faculties assigned to the 28 virtually all-white schools were

88% white.

Few of the 71 schools had principals or other administra

tive personnel assigned to supervise either faculties in which

teachers of a different race predominated (DX 3, 10/69) or

student bodies in which the majority of the pupils were of a

different race (compare DX 3, 10/69 with GX 3, 10/69).

Residential Racial Discrimination

In 1968 this court directed the district court to determine

the extent of racial discrimination with regard to housing

in the City of Norfolk. Evidence was taken in conformance

with the remand during the April, 1969 hearings. The district

court in its 1968 opinion, and again in its May 19, 1969

opinion, 302 F. Supp. 18, described in a summary fashion some

of the instances of public and private activity which has had

the effect of containing or restricting the residential

mobility of black citizens to certain areas of the City of

Norfolk (16 Tr. 23).

-9

PUBLIC ACTION

1. Public Housing projects

Twelve of the 14 public housing projects operated by the Norfolk

Redevelopment and Housing Authority are occupied exclusively by

blacks. The remaining two projects are racially mixed (16 Tr. 122-25)

The Assistant Regional Administrator, HUD, having jurisdiction

over Virginia, qualified as an expert on racial housing patterns.

He testified that prior to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

tenants were assigned to public housing projects on the basis of

race (Tr. 114). From 1964 to June of 1967, most local authorities

in the region adopted either a freedom of choice or a first come,

first serve policy. Since June of 1967, the HUD regulations have

required all housing authorities to adopt the first come, first served

9/

method of tenant selection and assignment (16 Tr. 114).

Although Norfolk adopted the freedom of choice method of tenant

selection following the passage of the Act, and the "first come,

first served" method in April of 1968, there has been "little change

in the racial character of the occupancy of projects operated by

the Norfolk Housing and Redevelopment Authority." (16 Tr. 116).

8/

8/ Of the federally-assisted projects (the Authority totally owns

3), the ten all-black projects house a total of 3719 families

or 89.4% of the total number of project families. The one

racially mixed project houses 394 families or 10.6% of the total.

(See GX M, M-l, 4/69).

9/ The new policy actually operates as a limited freedom of

choice. Depending on the number of projects operated by the

local authority, an eligible applicant may have up to a

maximum of three opportunities to refuse assignment to a

particular project as long as such refusal is not based on

race (16 Tr. 15).

-10 -

Generally speaking, prior to the passage of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, public housing sites were selected in areas where they

would serve only one race. (16 Tr. 112-115). From 1964 to February

of 1967, the general criteria for acceptability of sites v/as to the

effect that they should be in areas reasonably accessible to both

white and black citizens.

The HUD expert testified that because public housing projects

generally generate 3.5 school age children per family, the location

of the project has a direct effect on the school system; that in

many cases it is necessary to build additional schools to absorb the

children coming from the projects; and that when those schools are

built within or contiguous with existing public housing projects,

the schools tend to reflect the racial character of the project

(16 Tr. 118-19).

An example of the relationship between public housing projects

and the racial character of the surrounding public schools is found

in the "Four Year Construction program" dated July 6 , 1950 (GX F-16,

4/69) which lists many new schools necessitated by housing projects,

and the School Board minutes of September 13, 1951 (GX F-20, 4/69).

A clear indication of the interaction between the two agencies is

also found in the 1949 program Statement of the Housing Authority

which identifies numerous schools to be constructed for pupils of a

particular race or converted from white to black because of public

housing development (GX G-l, 4/69, pp. 35, 37-38). Thirteen of the

14 projects were constructed prior to 1955 (GX M, 4/69).

H

Since February of 1967, the regulations of the Department

(of H.U.D.) have required local authorities to select sites which

will permit the inclusion of applicants from all races and will

provide an opportunity for minority groups to obtain federally

assisted housing outside their area of concentration (16 Tr. 112).

All of Norfolk's 13 projects were constructed prior to 1964. (See

GX M-l, 4/69).

Since the announcement of the 1967 criteria for site selection,

the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority has made eight

submissions for new sites to federal authorities. Six of these site

were rejected because they were located in areas of racial

concentration and were the only sites submitted for review (16 Tr.

121) .

2. Public School Location

The location of schools has always been an important factor

in the development of the residential patterns in Norfolk. The

deliberate location of Booker T. Washington High School, built in

1929 as a school for black students, adjacent to a 95% white area

had the predictable effect of transforming it to an all-black area

10/

within a period of 7 to 8 years (16 Tr. 128, 131). At least 63 of

of the 73 schools in Norfolk were constructed during the period when

10/ other examples of the impact of school siting may be

found in GX D-16, F-20, G-l, pp. 36-38, 4/69.

12

they were deliberately planned for pupils of one race (GX D, 4/69).

In addition to its cooperation with the housing authority in

the location and construction of segregated schools, the Norfolk

board has acted in other ways to build its exclusionary attendance

areas upon both public and private racial discrimination.

. . . the test of residential proximity

is rigorously applied.

Honors go to Norfolk for executing "the

northern plan" to the point of caricature.

To strengthen its exploitation of existing

housing patterns, many of the city's new

schools are small, three-to-four room

structures for the first three-to-four

grades. These little boxes are carefully

located to maximize de_ facto school

segregation. At one point, Norfolk's

city council considered a proposal for

constructing sixty-eight of these tiny and

inefficient schools. Negroes joked the

city would soon provide a separate school

for every Negro child in his own backyard.

Pettigrew, Thomas F., De Facto Segregation, Southern Style,

12/

Integrated Education, June-July, 1967.

3. State Statutes and City Ordinances

Several Virginia statutes and Norfolk City ordinances

prohibited black people from living in the same area of Norfolk as

11/

11/ GX D shows that 28 of the existing schools were constructed

prior to 1930, 33 between 1930 and 1960 (with 25 of these

between 1950 and 1960) and only 10 since 1960.

12/ The rest of the quoted material is pertinent: "The city

has its own placement criteria: achievement test performance,

'ability to adjust,' and place of residence. In assigning

students to schools, only Negro test scores are considered

. . . ." See pp. 2 - 4 supra.

13

1 3 /white people.

PRIVATE ACTION

In addition to the policies and practices of the federal,

state and city governments, private discrimination or non-governmental

actions have played a substantial role in establishing Norfolk's

segregated housing patterns.

Historically, some of the black areas developed from areas

inhabited by servants who lived just adjacent to the very affluent

areas of the city. Blacks who migrated to the city from rural areas

were almost automatically directed to the pockets where black people

lived (16 Tr. 211-12 ). Some examples of the areas which developed

13/ Chapter 157 of the Acts of 1912 is captioned "An Act to

provide for designation by cities and towns of segregation

districts for residence of white and colored persons; for

the adoption of this Act by such cities and towns and for

penalties for the violations of its terms." (12 Tr. 165).

This Act reappeared in 1916 and 1919 (12 Tr. 167), and

these sections were not included with other acts which were

repealed in the 1944 and 1946 supplements. The 1948 Code

reflects that these sections (3043 and 3053) were omitted.

This enabling legislation permitted cities to adopt local

ordinances requiring residential segregation.

The city of Norfolk adopted such an ordinance in 1920.

Chapter 7 is entitled "Segregation of White and colored

residents" and Section 11 is headed "Residence in same block

prohibited." (Code of 1920, pp. 107, 108). The Code of the

city of Norfolk of 1944 indicates that between 1920 and 1944

the ordinance had been amended to forbid residence by white

and Negro persons in the same community, except by agreement

by the majority of the residents of the community, as well

as those in the same block (12 Tr. 167-68). (Code of the

City of Norfolk, Va., chapter 12, Sections 153 and 154,

pp. 159-61). The ordinances were not repealed until May 1,

1951.

14

in this manner are Bowling park, Titustown and the area adjacent

to Chesterfield Heights (16 Tr. 212).

1. Real Estate Sales and Rentals

It is estimated that 99.9% of the real estate market in

Norfolk is controlled by white realtors (16 Tr. 203).

Prior to the recent thrust for open housing, it was extremely

difficult for white real estate agents to sell property to blacks

in traditionally white neighborhoods. During the early fifties a

white real estate agent was practically run out of town for selling

a house in the (then) all-white Campostella area to a black

purchaser (16 Tr. 166). Racial discrimination against black

purchasers was "a very prevalent practice" 18 or 20 years ago

(16 Tr. 167) .

Unitl 1967, real estate sales in the daily paper were listed

separately for whites and blacks (16 Tr. 182). Black realtors could

not advertise any property for sale except in a column designated

"for sale to colored." The only property they could offer at all

was that located "in an established colored neighborhood." (16 Tr.

183) .

Black realtors were not permitted to advertise property in

white neighborhoods for sale in the "for sale to colored" column

even though the owner had requested that we sell it to colored, or

anybody for that matter" (16 Tr. 182-83).

The availability of housing which black brokers can offer for

sale is further limited because they are not permitted to become

members of Multiple Listing (16 Tr. 190). As a member of Multiple

Listing, a broker would have hundreds of houses at his disposal to

15

show clients as compared with the present average of "eight or

nine houses for sale at any one time" (Ibid.). The black brokers

are denied the right to participate in Multiple Listing solely

because of race (16 Tr. 193).

Additional limitations on the availability of housing offered

for sale or rent to black purchasers are caused by the unwillingness

of white brokers to co-broke on houses that are offered to blacks in

mixed or white areas (16 Tr. 190), although they are quite willing

1 4 /

to co-broke predominantly black areas (16 Tr. 232).

Other practices by white brokers include the outright refusal

to show houses in white areas to black purchasers or the discouraging

of white purchasers or the discouraging of black purchasers with

statements such as "your client won't be happy here" (16 Tr. 190)

or "you don't want to live in this neighborhood." "You want to

live where you'd be happy." (16 Tr. 177).

The few black agents who managed to sell homes in white

neighborhoods often did so at great financial sacrifice. In some

cases the black agent had to relinquish'his commission on the sale,

because, in an effort to block the sale, the white agent would

refuse to co-broke the transaction. Most of the houses sold in

mixed areas or in previously all-white neighborhoods were sold

under the government programs, such as FHA and VA repossessions or

foreclosures and were thereby available to all purchasers without

discrimination (16 Tr. 185, 240).

14/ Co-broking . means the listing agent agrees with the

selling agent to split the commission (16 Tr. 233).

- 16

2. Restrictive Covenants

Many of the deeds to residential property in Norfolk contain

racial restrictive convenants (16 Tr. 259). Some of these

convenants contain a reverter condition which requires a release

from a trustee (Ibid.), and some of the restrictions will not

expire until 1997. (See GX E-l; E-2, E-4 and 16 Tr. 258-69). The

extra expense of securing a release ranges from $20.00 to $75 per

deed (16 Tr. 251). Such convenants, like the repealed city

ordinances (which may have no present standing in the law) contribute

to segregated residential patterns, and the regressive effects of

these restrictions continue long after they have been lifted (16

15/

Tr. 137-38) .

3. The Continued pattern Of Discrimination

Racial discrimination against blacks seeking housing has not

ceased in recent years (16 Tr. 187-188, 230, 232). On at least 20

occasions immediately preceeding the April 28, 1969 hearing, a

black real estate agent was expressly told that certain houses would

not be shown to or was not available to black purchasers or renters

(16 Tr. 190).

The president of a local fair housing organization personally

received several hundred complaints from black families seeking

housing during each of the past two years (16 Tr. 208).

In a survey taken by the Fifth Naval District Headquarters in

May of 1967 only 41% of the facilities surveyed and 46% of the units

affected had a policy of renting to black armed services personnel.

15/ Compare Evans v. Abney, 396 U .S . 435 (1970).

17

Of the 393 facilities (containing 29,209 units) listed in the

survey, only 162 facilities (containing 13,504 units) indicated

16/

that they followed a non-discrimination policy (16 Tr. 152).

The district court misconstrued the mandate of this Court

in holding that the evidence "falls far short of establishing

any discrimination which would be tantamount to governmental

action realistically affecting residential areas." 302 F. Supp.

at 27. For it is clear that the combination of governmental

decisions determining the zoning and the use of land, together

with the actions of persons and institutions who control housing

and land, such as property owners, builders, real estate agents,

lending institutions, brokers and other governmental agencies,

have resulted in Norfolk in a severe limitation of the choices

available to blacks seeking housing and consequently resulted in

racial residential segregation (16 Tr. 126-27).

The Board's Plan

The Board's proposed plan incorporates two different methods

of pupil assignment: a single geographic zone for each elementary

and high school and a feeder pattern for junior high schools.

However, the high school assignments will take effect in two stages,

which the board has denominated Phases 1 and 2, respectively.

16/ After a period of time during which those facilities not

agreeing to accept black servicemen were made unauthorized

for military occupancy (16 Tr. 163), 97% of the facilities

containing 99% of the units)agreed to accept military personnel

of all races.) As of April of 1969, 381 facilities (containing

36,290 units) of a total of 392 facilities (containing 36,587

units) agree to accept black servicemen (16 Tr. 157).

18

The elementary school plan (DX 1-A) creates contiguous

17/

attendance zones around each of the 52 schools. These zones

are then combined in a feeder pattern so that the elementary

zone residence of a pupil determines his junior high school

18/assignment.

The Phase 1 high school zones (DX 1-B, .10/69) to be

employed until the construction of the new high school on Tidewater

19/

Drive is completed — retain the zone boundaries in effect in

17/ Initially there will be 53 zones? however, upon completion

of a new elementary school under construction in the

Ballentine—Lafayette area, use of those, facilities will be

discontinued and a zone for the new school established

encompassing both attendance areas and a portion of the initial

Lindenwood attendance area (DX 1, 10/69). Also, Little Creek

Elementary and Little creek primary School share the same

geographic zone (DX 1-A, 10/69).

18/ The junior high school assignment plan may thus also be

expressed as zones. Such zones are contiguous, unlike the

phase 2 high school zones, but otherwise hardly resemble the

elementary school zones. Like the high school zones, they

cover very extensive areas of the city and are sectored by

many natural and man-made boundaries (28 Tr. 22-28) . ̂ The

result is not even a reasonable racial distribution in the

junior high schools, however. The projected racial composition

of each junior high school practically mirrors its 1969-70

free choice composition (GX 3, 10/69). The only signifxcant

change is at Rosemont. Whereas one junior high school is

attended solely by students of one race in 1969-70, the board

projects three such schools under its plan, enrolling 31/ of

all junior high students. Forty-five per cent of the black

junior high students will attend all-black schools. (See

Table 1, Appendix, infra).

19/ At the October 1969 hearings, the earliest completion date

for the new high school was estimated to be the 1972-73 school

year assuming no construction or other delays interfering with

the building (27 Tr. 52). Dr. McLaulin recognized that such

delays could postpone the opening of the new high school for a

"substantial period of time" (28 Tr. 4).

19

1969-70, with no significant modifications (27 Tr. 126, 202).

Under this plan, Booker T. Washington High School will remain

20/

virtually all-black and the other high schools will experience no

shifts in their racial composition.

The district and the court below, despite an Alexander motion,

rejected alternatives which would desegregate Booker T. Washington

High School under phase 1, because desegregation of this school

would require assignment of white students to this traditionally

black school -- a move unpopular with whites (28 Tr.l4). The

district also claimed its decision not to integrate Booker T.

Washington was based upon its desire to avoid two substantial

student reassignments within a short period of time and to avoid

the busing necessary to make Washington a majority-white school

reflective of the system-wide population and consonant with the

"principles" of its plan. (28 Tr. 11-13). Since Washington serves

grades 10-12, however (GX 3, 10/69), and the new facility could not

open before 1972-73, the same pupils would not be shifted twice if

Washington were desegregated in September, 1970; and the number of

black students who must be transported from the Washington area to

other schools under Phase 2 is nearly the same as the number requiring

transportation if Washington were to be desegregated now (28 Tr. 7-11) .

When construction of the new facility is completed, Booker

T. Washington will be discontinued as a regular high school

20/ The present Washington zone was first delineated by the

board for the 1967-68 school year, when as now, less than

ten white children attended the school (27 Tr. 129).

20

21/ 22/

(DX 1, 10/69). The projected zoning of the remaining high

schools (DX 1-C, 10/69) contemplates the attendance of relatively

equal percentages of black students at each high school through

the use of non-contiguous zoning and school district transportation

23/

of pupils (GX 3, 10/69; 22 Tr . 98-99, 27 Tr. 188, 28 Tr. 35-36).

21/ There was vague testimony at the hearings about using

Washington for special education (28 Tr. 15) or reopening it

as an all-black high school should the system-wide percentage

of black students exceed the "optimal" percentage as expressed

in the principles (28 Tr. 21). When this occurs, the plan

calls for the reopening of the school as an all-black

"warehouse" for excess blacks (28 Tr. 20-22).

22/ The location of this new senior high school and the

closing of Booker T. Washington present different legal

issues in the present context of the Board's plan, which

contemplates the assignment of students in such a way as to

achieve racial balance in each high school.

23/ (Dr. Foster):

The senior high projection -- if we assume that

Booker T. Washington would remain in force for

at least three or four years, or however long it

takes to get a new high school built, according

to this year's figures, there are 3,315 blacks

assigned to schools of over 40 per cent Negro

population. This makes a total of 78.6 per cent

of all the senior high blacks, and there are 933

whites or 12.9 per cent of the senior high whites

assigned to such schools...

Well, the figures I have for the long-range plan

on that would be sort of a balance, which would

mean there would only be one school above the 40

per cent level, according to this, and that would

be Maury, which would be at the 45 per cent level.

All the rest would be under the 40 per cent outside

limit that the Board's principles stated.

(22 Tr. 98-99) .

21

Although Norfolk's student population is 42% black (cf.

27 Tr. 17), the effect of the plan is to create eleven (11)

all-white and twenty-one (21) all-black schools. All the schools

retain the- traditional racial identities they developed under

previous dual zoning, pupil placement, and free choice (see GX 3,

24/

10/69). Table 1, printed at the beginning of the Appendix to

this Brief, infra, provides complete detailed information on the

effect of the school board's plan.

The Board admits these are the results obtained under its

plan and seeks to justify them by adopting certain purportedly

nondiscriminatory, educational "principles" which it says guided * I

24/ (Dr. Foster):

I figured these out a little bit last night, and if we

assume considerable desegregation it may not occur in many

elementary schools. For example, they have projected a ten

per cent desegregation figure, which may not be too realistic,

but the long-range plan, as I understand it, will result in

the Board's relegating the following numbers to what, by their

own definition in the principles, would be the academic scrap

heap if you use 40 per cent Negro, as they have, as the top

figures for racial mixture:

Now, at the elementary level, as I read these figures,

there would be 11,585 blacks in schools more than 40 per

cent black. This includes 19 elementary schools which would

be all black and two which would be mostly black. One would

be Campostella, which the figure states as 75 per cent black.

The other is Chesterfield, which would be 85 per cent black.

So, this indicates that 83^ per cent of the black elementary

student population would be assigned to these 19 all-black

schools or the two, Campostella and Chesterfield, which are

largely black. In addition, there would be a hundred and

sixty-five whites assigned to these two mixed schools at the

elementary level.

At the junior high level my figures indicated 3,700 blacks

would be assigned to schools over 40 per cent black, which

makes a total of 62.7 per cent of the total black junior high

population. Five hundred and fifty whites would be assigned

22

25/

it in developing its plan.

There is no mention of the area-based assignment concept

in the formal statement of principles portion of the board's

plan. Its selection as the basic method of assignment limits

all of the other principles upon which the district purports to

base its plan (28 Tr. 99); operating within this framwork, the

Principles have the effect of further limiting desegregation under

2 6/

the area-based plan.

24/ (continued)

to these schools, which is, according to my figures 7.8

per cent of the junior high whites. (Tr II 96-98).

25/ A considerable portion of the extended hearings below,

and particularly the examination of the expert witnesses

for all parties, was devoted to a minute analysis and

explication of the principles. The further one delves into

these postulates to test their inaccuracies of formulation

or application, the more difficult it is to extricate

oneself and to return to a consideration of what the plan

actually does. The forest is lost for the trees.

This Court has indicated that results, not rhetoric, are

the central issue in school desegregation cases. E_.c[. ,

Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ., No. 13,229 (4th

Cir., Dec. 2, 1969). We accordingly do not treat the

principles at length here, (they are set out in full in

the district court's opinion at pp. 15-22) but merely

suggest their function and relation to the final result

achieved by the plan.

26/ The utility of geographic zoning alone is limited because

of racial residential segregation in Norfolk. See discussion

supra, pp. 9 - 18

23

The Principles purport to be conclusions drawn

by the Board from research studies to support the thesis

that no school which white students attend should have

2 8/

more than a 40%-Negro enrollment.- The district judge

commented during the cross-examination of Dr. McLaulin

(28 Tr. 69) :

27/

. . . I daresay the principles

were primarily drawn, although

I have no knowledge of it, by

Mr. Toy D. Savage, who is a

lawyer in this case. You

cannot put him on the witness

stand.

27/ See note 25 supra.

28/ It is difficult to succinctly state the "Principles

without some oversimplification. The Board admits

the greater educational desirability of desegregated

schools over all-black schools, but distinguishes

between majority-white and majority-black desegregated

schools, using research based on achievement test

scores. The former are said to afford increased

educational opportunity to black children, but the

latter are said to decrease the opportunities of

both white and black children. This conclusion

is stated in terms of social class, but the Board

determines that in Norfolk race and class are

synonymous.

■24-

Dr. McLaulin attempted to apply these principles in the

29/

process of circumscribing a zone around each school. Since

he did not possess particularized socioeconomic data for each

street or block in any zone (28 Tr. 47-48) or for any individual

zone in gross (28 Tr. 49-50), he relied upon generalized data

for planning districts and a school system Title I study (28 Tr.

46, 60). Since the principles also assume an identity between

black and lower class, the process really involved drawing lines

around white schools (which Dr. McLaulin assumed were middle-class

schools) to limit the number of Negro students who could attend

these schools (28 Tr. 73).

This effectively minimized integration (28 Tr. 74) and resulted

in anomalous patterns between adjacent zones. For example, Monroe

Elementary School will be all-black and must house 75 students

over its 1969-70 capacity, while the adjacent Stuart Schoolwill have

so-called "optimal" desegregation but also 295 vacant spaces (28

30/

Tr. 63-63).

29/ The resultant zones sometimes followed, sometimes ignored

natural and artifical boundaries such as railroads and

highways (28 Tr. 102-105).

30/ Dr. McLaulin testified that shifting pupils from overcrowded

to underutilized schools, would require school district-

furnished pupil transportation and would lead to demands that

all children be bused at school expense (28 Tr. 90-91).

25

The Alternative plan

The United States, as plaintiff-intervenor in this matter,

presented to the district court an alternative plan to disestablish

the Norfolk dual school system prepared at its request by its

expert witness Dr. Michael j. Stolee, Associate Dean of the School

of Education at the university of Miami and formerly the Director

of the HEW-funded Title IV consulting center at that university.

Plaintiffs in the district court supported the government's request

for implementation of this alternative plan, and we seek similar

relief from this Court.

The Stolee plan referred to in the record as "Overlay c"

31/

(GX 18-C-l through 18-C-6) combines, at the elementary level, three

basic techniques of pupil assignment: single school geographic

32/, 33/

zoning, contiguous, and non-contiguous groupings or pairings.

31/ The exhibits consist of compatible transparent overlays

designed to be placed upon a map of the school system such

as DX 1-A, 10/69, and which together illustrate how pupil

attendance at each school for each grade level is determined.

The senior high school feeder zones are illustrated on the

transparent sheet labelled GX 18-C-l and each high school is

treated separately on sheets 18-C-2 through 18-C-6 for a

clearer appreciation of how elementary and junior high

attendance at the feeder schools is determined.

32/ pairing of schools or Princeton grouping (26 Tr. 88-91)

(Madison-Larchmont-Taylor) is a common educational device

utilized as a part of regular school assignment practices

as well as in the context of plans to disestablish dual

school systems (24 Tr. 64-65).

Non-contiguous grouping or pairing involves the matching

of school facilities of related size and grade structure

although the traditional service areas are not contiguous

26

No single method would, if applied to every school in the system,

provide the degree of flexibility, in light of the existing

facilities, the segregated pattern of school construction and the

related segregated housing patterns, which is offered by the

application in various areas of the differing methods of assignment.

The junior and senior high schools are desegregated under the

Stolee plan by the use of feeder patterns; thus, the flexibility

offered by the use of different techniques at the elementary school

level carries through to the other grades.

32/ (continued)

and in some instances may actually be a substantial distance

apart. This pattern of pupil assignment is also found in the

educational process where desegregation is not at issue. For

example there may be an area of high density of pupil

population with a corresponding lack of sufficient classroom

facilities in the immediate area while at the same time there

exists within the system other school facilities with excess

space. The school board to relieve overcrowding or to avoid

large construction expenditures assigns either certain grades

or all of the students living in a portion of the overcrowded

zone to the school with excess capacity. (24 Tr. 64) .

In the context of a school desegregation plan the use of this

technique of assignment enables a school board to overcome the

effect of segregated construction and assignment policies,

which in conjunction with a community-wide pattern of

discrimination and in particular housing have contained black

patrons of the system. With the enormous investment in school

plants in areas of black or white residences where there are no

contiguous black and white schools, non-contiguous grouping or

pairing with the students transported to the respective schools

provides the cheapest method of meeting the Board's affirmative

duty to disestablish the pattern of state imposed segregation

in those schools.

Dr. Stolee's testimony expressed the option as a method

of transporting substantially fewer children over longer

distances (24 Tr. 76-77). particularly in Stolee's plan

whereby the non-contiguous pairings are made between the

schools in the most northern section (East Ocean View) and the

most southern portion (Diggs) (23 Tr. 134) the distances which

the majority of the other children in the system must walk or

be transported to school is thereby minimized (23 Tr. 125, 133-

34) -

- 27

Dr. McLaulin, who prepared the Board's plan, frankly

admitted that given Dr. Stolee's purpose (desegregating all of

the schools without regard to an area based limitation) , the

Stolee plan was as good as could be drawn (28 Tr. 97-98).

In the respective areas in which Dr. Stolee recommended

their use, both contiguous and non-contiguous grouping or cluster

pairing serve to preserve some aspects of the neighborhood school

32/ (continued)

In some instances the Stolee plan uses a single zone

drawn around a particular school where the use of such a

zone results in substantial desegregation (24 Tr. 63).

33/ The defendants' long-range plan utilized pairing to a

degree at the elementary level (28 Tr. 36-37). At other

grade levels, it employed the concept of non-contiguous

zoning:

Q. . . . [U]nder the Board's long-

range plan you do use the concept

of non-contiguous zoning; is that

correct?

A. Yes.

(27 Tr. 38) .

28

Each child would attendand to minimize bus transportation,

the closest school during some part of his elementary experience

(24 Tr. 86-87). The evidence in the record demonstrates that

existing regular line service of the transit authority, in a

number of instances, already provides ample bus service within

the grouped, cluster of schools.

The amount of bus transportation necessary and the capacity

needed to execute the Stolee plan is in some dispute. The Board

estimated the number of pupils required to be transported by

assuming the use of transit authority buses and limited its

34/

34/ "Now, let me — let me talk, sir, if I may, about the

Madison-Larchmont-Taylor group which on the overlay, (GX18-A)

which is outlined in blue, is the third group on the legend.

Q. All right, sir. A. Under this sort of a plan, Madison

might handle grades 5 and 6 for the entire area on the

overlay, which is outlined in blue, and then the Larchmont

and Taylor schools might each house grades 1 through 4.

Now, it anticipates, then, for these two 1 through 4

schools that there would be a boundary line drawn somewhere

through the existing Madison attendance area on the base

map so that all children south of that line in grades 1

through 4 would attend Taylor and all the children in the

whole area, as I said in grades 5 and 6 would attend Madison.

Now, the reason I say this would serve to minimize

transportation is because, in this sort of thing the children

in grades 1 through 4, I believe, would all be within walking

distance of their schools if they are, indeed, within walking

distance today.

The children in grades 5 and 6, I believe there might be

some transportation necessary at the extreme northern end

of the Taylor area." (23 Tr. 101-02).

29

consideration to gross estimates without allowance for pupils

who customarily utilize regular existing "line routes" of the

transit company (26 Tr. 91). Similarly, the transit company

based its cost estimates of the number of buses needed for the

Stolee plan solely on figures furnished by the Board, without

consideration of its existing regular transit routes (5 Tr. 137;

6 Tr. 90). The Board's projections, adopted by the district court

in its May, 1969 opinion, fail to take into account the transit

company's ability to carry approximately 2400 additional students

by filling the special buses in use at the present time to their

35/

capacity (26 Tr. 77-81). (The present average load is 45 students,

ibid.). The estimates also do not consider present excess capacity

on regular transit line service routes which serve almost all the

36/

schools, nor the possible operation by the district, with state

aid, of a school bus service to supplement the present Virginia

Transit Company capacity (25 Tr. 79-80).

The Norfolk school board operates now district-owned buses to

provide transportation to its vocational-technical school and for

handicapped children (25 Tr. 85). in 1968-69, four such buses were

operated and the board received $5,184.40 in state aid for their

35/ Mr. Armstrong of the transit company admitted the obvious

by agreeing that the per pupil cost to the company would be

reduced if each bus was filled to capacity (29 Tr. 83-84).

36/ Mr. Armstrong testified that the average load per hour

on regular transit routes was 30.5 passengers (29 Tr. 78).

30

37/

maintenance (id., at 82) .

The Virginia Transit Company presently operates special school

buses in conjunction with the Board of Education. These buses are

routed to pick up students near their homes each morning and

.transport them to the school of their assignment. Routes are

jointly established, changed or added to meet changes made by the

38/

School Board in its assignment patterns. in 1968-69, 82 such

buses (26 Tr. 50), with a capacity of sixty and an average load of

39/

forty-five students, operated each morning (26 Tr. 58).

37/ Since 1942 Virginia has offered assistance to local school

district transportation programs (25 Tr. 60) covering

maintenance, operating expenditures bus replacement costs, etc.

(Id. at 74) . Up to 100% of operating expenditures qualify

for reimbursement upon the application of a school district

(5 Tr. 69).

38/ The Virginia Transit Company is required under the terms

of its franchise with the City to provide such service with

a reduced fare to the student.

39/ Norfolk has historically required black students to make

transportation arrangements to get to school. "The location

of public schools for Negro children generally follows the

density pattern of the Negro population. However, two small

areas, Atlantic City and Bolling Brook, are not served by

schools at all, which means that the children living there

must travel great distances to and from school, at their own

expense." (GX G-l, 4/69, p. 36). Similarly, from 1963-64 to

1969-70, when black children were afforded choices between

black and white schools within attendance areas, no transportation

assistance was afforded by the school system -- even when the

Booker T. Washington High School zone overlapped the entire city

boundaries. Finally, under the Board's proposed phase II plan,

nearly 2300 black high school students will be required to

travel from the Booker T. Washington area to distant facilities

in other parts of the city (28 Tr. 5-6) .

31

These buses are in addition to those operating on regularly

scheduled transit routes. Plaintiffs introduced a large map

prepared by the transit company showing all existing regular

transit routes (DX 7, 10/69) . The record (25 Tr. 120 e^ secy. )

and the exhibit demonstrate that most schools in the system are

already served by one or more regular transit routes passing in

close proximity to the schools.

The system of special school bus transportation has operated

in Norfolk for many years. During the 1969-70 school year, 8,190

students were transported each day by special bus to public schools

(26 Tr. 76). In addition, many other students are transported to

public schools by private automobile (6 Tr. 42). The determination

of the number of students using transit authority buses is based

on the number of reduced fare tickets turned in to the transit

company. Of the 8,190 daily round trips reflected in reduced fare

tickets collected (26 Tr. 76), between 23 and 25% of the pupils do

not ride the special buses but instead utilize the regular "line"

transit routes (25 Tr. 118).

The National Education Association reports that each day

during the 1967—68 school year, 17,271,218 pupils were transported

to school at public expense (GX 20, 10/69). That same study shows

that pupil transportation is a growing facet of public education.

From 1954-55 to 1967-68, the national total almost doubled: up

from 9,509,699 to 17,271,718. As the District Court noted (24 Tr.

56) :

- 32

I will take judicial notice

of the fact that there are fewer

children now who walk to school

than walked when I went to school.

I can tell you that. They all

have automobiles and ride buses.

In Virginia the number of pupils transported at state expense

during the 1967-68 school term was 573,207 (25 Tr. 65). The state

appropriations for transportation in 1969-70 were $9,140,460., up

from $5,705,800. in 1960-61 (25 Tr. 64-65). Within the cities of

Virginia alone, the number transported at state expense was 82,700

40/

pupils.

The Annual Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction

for 1967-68 (PX 5, 10/69) states at page 103 that "[m]ore than

60% of the pupils attending public schools in the State are

transported in school buses. The number of pupils has been

increasing at an annual rate of approximately three per cent." In

cities adjoining the City of Norfolk, pupil transportation by the

school district with state assistance is a common factor. During

1967-68 in Virginia Beach, to the east of Norfolk, 33,431 pupils

were transported; in Chesapeake City 18,600 pupils were transported

to the north, Newport News transported 20,197 pupils and at Hampton

41/

Roads it was 5,495 students. (PX 6, 10/69). Some of the larger,

40/ These figures do not include bus transportation to private

schools, nor students riding, as in Norfolk, public transit

at their own expense.

41/ The table in PX 5 at pp. 118-19 shows that school buses

operated with state aid in cities carried a higher "Average

Number of Pupils per Bus" and a lower "Average Miles per

Bux Per Day" than in the counties.

33

highly urban counties including Arlington (9,840 pupils), Fairfax

(64,293), Chesterfield (20,160), Henrico (21, 369) and Roanoke

(15,696) receive State assistance for their transportation

programs (Ibid).

The average per pupil transportation cost for the State in

1967-68 was $26.91 (PX 5, 10/69). For cities in Virginia it was

42/

$19.91 (Id at 118-19).

Dr. Stolee considered both the existing modes of pupil

transportation and the means available to meet additional capacity

needs in drawing his plan;

[The Court]:

I take it, Doctor, as to any bussing, we are now

abandoning any thought of public transportation and we

are going into school operated bussing; isn't that

true, under any -- any plan, at least, that you have

advocated here, that public bussing is out of the

question?

THE WITNESS: Nq sir, and you're getting at the

reason why I did not compute the cost of the bussing,

because there are so many ways it could be done. One

is for the School Board, as you state, to purchase a

fleet of school buses. . . and operate them. The

second one is to continue the arrangement with the

Virginia Transit Company for that sort of transportation.

The third --

THE COURT: Well, I understand that. But how in

the world could you ever allocate these -- and schedule

these drivers, with all this interchange that you

propose? After all, they have to do something besides

just drive a bus for school children. They are hired

on an eight-hour schedule proposition. And is that

feasible?

42/ The record reveals that buses meeting the state

requirements could be purchased by the transit authority

for $8,200 (29 Tr. 80) and by contract with the system

receive state assistance (25 Tr. 98-99). The record also

reflects that buses when owned and operated by school

systems actually result in lower per pupil costs and

consequently higher levels of state assistance (25 Tr.

97-100).

34

I thought now that we were probably disregarding

entirely any question of the Virginia Transit Company

providing transportation, no matter who pays for it.

THE WITNESS: Well, Your Honor, there are many

ways of taking care of this. One of the best ways I

have seen is used by the school system in Broward

County, Florida -- that's the Fort Lauderdale area --

in which the schools start at different times. There

is no real reason why every school in the city must

start at the same time, and their fleets of buses serve

as many as four separate schools in the afternoon, and

they keep their men pretty busy during the whole time,

and they work three or four hours in the morning; they

work three or four hours in the afternoon. They might

have a much longer lunch hour than most of us would

have, but they get in a full day by that, but the

school system — by changing times of schools or by

having schools open at different times and close at

different times results in considerable savings in

terms of equipment and salaries.

That's one of the things that might strongly be

considered here.

(23 Tr. 204-06).

35

ARGUMENT

Q. If the school board says to the Negro

child, when [s]egregation is required by

law, that "You stay in this all-black

school" and if under your plan he is still

in the same school and [it] is still all

black, what's the difference as far as the

effects of your action as a school board?

A. Well, we are saying to the child . . .

that his faculty will be ultimately the

equal of other faculties; that the building

and material things will be the same . .

and that other compensatory procedures

will be afforded to make up for our

inability . . . to put him in a desegre

gated situation.

---School Board president Thomas

October 8, 1969 {21 Tr. 205)

We come then to the question presented:

Does segregation of children in public

schools solely on the basis of race,

even though the physical facilities and

other "tangible" factors may be equal,

deprive the children of the minority

group of equal educational opportunities?

We believe that it does.

-- Brown v. Board of Educ^, 347 U.S.

483, 493 (May 17, 1954)

-36-

Introduction

Sixteen years after Brown v. Bd. of Educ.; fourteen years

after 150 black pupils and their parents commenced this litiga

tion; twelve years after this city closed its public schools

rather than permit a single black child to enter a "white"

school, the Norfolk School Board is telling black children that

they may not attend public schools because they are black.

The district court's approval of a so-called "desegregation

plan, " which operates to increase segregation, not to facilitate

integration, is another slap in the face to thousands of black

parents in Norfolk who have watched as an entire generation of

their children attended and departed segregated schools, while

they put their faith in the law.

The commands of the Constitution could not be more plain,

simple and direct. in Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, 437-38, 442 (1968), the Supreme Court noted

that Brown required school districts to take "whatever steps might

be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial

discrimination would be eliminated root and branch . . . to convert

promptly to a system without a 'white' school and a 'Negro' school,

but just schools," large districts and small districts alike,

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968). In

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19, 20 (1969),

the Court reaffirmed the law's command that "no person is to be

-37-

effectively excluded from any school because of race or color."

The conflict between the board's plan, which minimizes integration,

and these rulings is perfectly obvious. Yet the district court

approved the plan.

In 1968 this Court warned that geographic zones which

produced heavy proportions of students of one or the other race

in various schools could not be employed if "residence in a

neighborhood is denied to Negro pupils solely on the ground of

color . . . [i]f residential racial discrimination exists, it is

immaterial that it results from private action." 397 F.2d at 41.

The evidence in this record of consistent and continuing public

and private action to keep blacks from living in "white" areas

(see pp. 9-18 supra) compels the conclusion that the board's

zoning plan, which results in 32 schools attended solely by student

of one race, is unconstitutional. Yet the district court approved

the plan.

In Brown v. Board of Educ., supra, 347 U.S. at 494-95, the

Court wrote:

To separate [black children] from

others of similar age and qualifica

tions solely because of their race

generates a feeling of inferiority

as to their status in the community

that may affect their hearts and

minds in a way unlikely ever to be

undone. . . . Separate educational

facilities are inherently unequal.

Norfolk's "plan" itself explicitly tells black children that they

are being placed in all-black schools because they are "low

socio-economic class," a term which can hardly be said to connote

superiority. Yet the district court approved the plan.