Brown v. Rippy Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Rippy Appellants' Brief, 1956. 97ac78ab-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fee87141-8736-49e3-baf6-c525c474ce4c/brown-v-rippy-appellants-brief. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

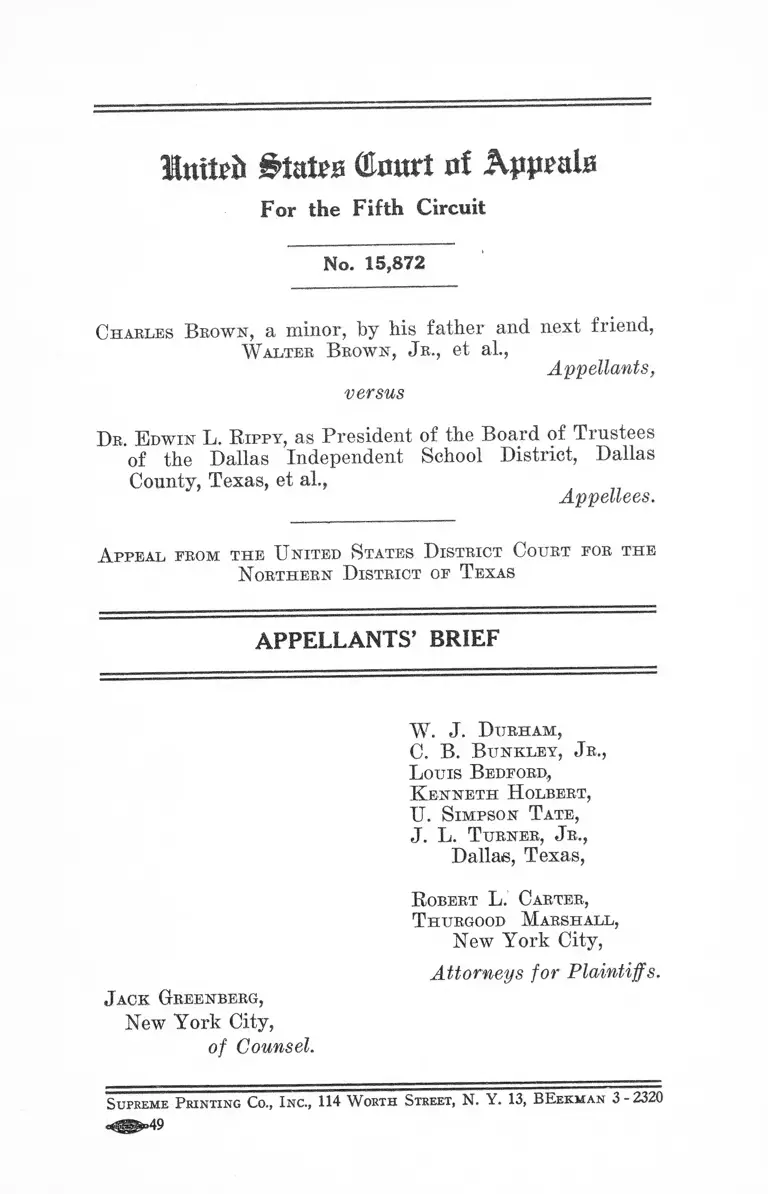

I n r n f t Bum © B u r t B f A p p e a ls

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 15,872

Charles Brown, a minor, by Ms father and next friend,

W alter Brown, Jr., et ah,

Appellants,

versus

Dr. E dwin L, R ippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas

County, Texas, et ah,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the United States D istrict Court for the

Northern D istrict of T exas

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ack Greenberg,

New York City,

of Counsel.

W . J. Durham,

C. B. B unkley, Jr.,

L ouis Bedford,

K enneth H olbert,

U. Simpson Tate,

J. L. T urner, Jr.,

Dallas, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

New York City,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

Supreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekm an 3 - 2320

lUuti'ii (tart nf Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 15,872

C harles B row n , a m in or, b y his fa th er and next frien d ,

W alter B ro w n , J r ., et al.,

Appellants,

versus

D r . E dw in L. H ip p y , as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas

County, Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal prom th e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt por the

N orthern D istrict op T exas

—-------------------o---------------------

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

On September 12, 1955, plaintiffs, Negro children, filed

a complaint (B. 4) by their next friends seeking to tem

porarily and permanently enjoin defendants 1 from segre

gating them in elementary and high school education. They

prayed for a declaratory judgment that Section 7, Article

VII of the Constitution of Texas and Articles 2900, 2922-13

and 2922-15 (Vernon’s Ann. Civ. Stats.) are unconstitu

tional under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution in so far as they may require racial

segregation in elementary and high schools in Texas. The

complaint requested that the district judge convene a three-

1 President of the Board of Trustees of the Dallas Independent

School District, members of the Board of Trustees of the Dallas

Independent School District, the Superintendent of Public Schools

of the Dallas Independent School District and six principals of

elementary and high schools in the Dallas Independent School

District.

2

judge court pursuant to Section 2281-2284 of Title 28,

United States Code.

Defendants’ answer alleged (R. 30) that “ The adminis

trative staff and the district trustees are now and have

been making an honest, bonafide, realistic study of the facts

to meet the obligations the law has placed upon them to

provide adequate public school education and to perfect,

as soon as possible, a workable integrated system of pub

lic education” ; (R. 30) that the Dallas public school system

had theretofore been operated as a segregated school sys

tem and that fiscally and administratively it had been based

upon segregation. It alleged that on July 13, 1955, the,

president of the board issued a statement regarding de

segregation which outlined 12 points for study, largely mat

ters relating to school administration; that, “ A review of

scholastic census was immediately started and maps imme

diately prepared to fit the school building capacity to the

area producing the students on the assumption of a desegre

gated basis.” It cited alleged administrative difficulties

in immediately desegregating 2 and concluded with a prayer

2 The administrative considerations were :

“ 1. Scholastic boundaries of individual schools with relation to

racial groups contained therein.

2. Age-grade distribution of pupils.

3. Achievement and state of preparedness for grade-level assign

ment of different pupils.

4. Relative intelligence quotient scores.

5. Adaptation of curriculum.

6. The over-all impact on individual pupils scholastically when

all the above items are considered.

7. Appointment and assignment of principals.

8. The relative degree of preparedness of white and Negro

teachers; their selection and assignment.

9. Social life of the children within the school.

10. The problems of integration of the Parent-Teacher Associa

tion and the Dads Club organization.

11. The operation of the athletic program under an integrated

system.

12. Fair and equitable methods of putting into effect the decree

of the Supreme Court” (R . 32-33).

3

that injunctive relief be denied and no declaratory judg

ment entered.

On September 16, 1955 a hearing was held on the ques

tion of whether or not a preliminary injunction should be

issued (R. 66). Defendants’ allegations concerning admin

istrative difficulties, preparations and the legal conclusions

to be drawn therefrom were denied by plaintiffs.8

Notwithstanding this denial the court held that the

“ facts . . . are well pleaded in both the original petition and

the answer, [and] are admitted in open court, thus saving

the introduction of a string of witnesses which take time

and multiply costs.” (R. 63) The court further held that

“ there is no constitutional provision of either the state or

the nation, that is in controversy in this particular suit” ,

(R. 63) and consequently refused to convene a three-judge

court.

The court below acknowledged the decision of the United

States Supreme Court in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497.

However, it also found vitality in the “ separate-but-equal”

doctrine and. wrote that “ All of the law as declared by the

various Courts, appellate and trial, in the United States

are agreed upon the proposition that when similar and con

venient free schools are furnished to both white and colored

that there then exists no reasonable ground for requiring

desegregation. ’ ’ Desegregation, it held, was a matter solely 3

3 “ Mr. Thuss (counsel for defendant) : Well, I have other

evidence than that, your Honor; I have other things that the Board

had done. What Dr. White has done.

“ The Court: Do you plead that in your pleadings ?

“ Mr. Thuss: Yes, sir, we set it out step by step in our pleadings.

“ The Court: Well, do you agree, gentlemen, that those facts

are all right?

“ Mr. Durham (counsel for plaintiff) : Your Honor, we can't

agree to his pleadings” (R . 51).

On the argument it was admitted only that one defendant traveled

to Austin to discuss some school segregation problems with the State

Superintendent of Education (R . 49-50).

4

within the discretion of school officials stating that the

‘ ‘ direction from the Supreme Court of the United States

requires that the officers and principals of each institution,

and the lower courts, shall do away with segregation after

having worked out a proper plan. That direction does not

mean that a long time shall expire before that plan is

agreed upon. It may be that the plan contemplates action

by the state legislature.” (E. 65)

Taking judicial notice of the “ equality” of Negro and

white schools in Dallas the court concluded that the com

plaint therefore lacked equity and dismissed without preju

dice.

Specification of Errors Relied Upon

1. The court below erred in holding that where separate

but equal facilities are provided defendants may not be

required to desegregate.

2. The court below erred in dismissing the complaint.

ARGUMENT

1. The Court Below Erred in Holding That Where

Separate But Equal Facilities Are Provided Defend

ants May Not Be Required to Desegregate.

Although the court below was aware of the Supreme

Court’s decision in the school segregation cases which, of

course, overruled “ separate but equal” at least so far as

public education is concerned it imported into the law a

novel doctrine which effectively revived “ separate but

equal.” By advancing “ equality” as grounds for dis

missal, its opinion read as if it was rendered prior to May

17, 1954, the date of the Supreme Court ’s opinion in Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

5

Appellant need not reiterate here the succinct and clear

holding in the school segregation cases that racial segre

gation in education is unconstitutional. Indeed the Su

preme Court has held that all laws requiring such segrega

tion “ must yield,” 349 U. S. 294. But nowhere did the

Court even intimate that “ equality” of facilities would

be grounds for dismissal of a complaint praying for de

segregation, or even grounds for a delay. Indeed, it can be

argued forcefully that where facilities are “ equal” there

is little or no reason for deferring desegregation for ad

ministrative reasons. For, in such cases the problem of

distributing equally educated students among equal class

rooms and other facilities should be minimal. Therefore

the trial court’s opinion, based upon the “ separate-but-

equal” doctrine, was erroneous and should be reversed.

2. The Court Below Erred in Dismissing the Com

plaint.

The court’s dismissal of the complaint was unprece

dented and contrary to prevailing authority. The grounds

for dismissal were (a) its erroneous assertion that the

“ separate-but-equal” doctrine retains vitality and perhaps

(b) that the grounds advanced for delay in defendants’

answer warranted delay and therefore, apparently, dis

missal. These grounds encompassing administrative con

sideration (see footnote 2 supra) were not admitted by

plaintiffs at the hearing,4 and no proof was presented.

Nevertheless the court in its opinion accepted them as true.

The mere averment of these controverted grounds in

the answer was certainly no grounds for delay. The United

States Court has held that certain administrative consid

erations may warrant delay in desegregating, but that the

burden is upon the defendant to establish the justification.

4 Ibid.

6

Surely this burden is not carried by a controverted asser

tion that grounds exist for delay.

However, the court below went further than accepting

defendants’ controverted averments without proof as

ground for delay. It dismissed. The proper procedure,

of course, would have been to put the defendants to their

proof. But even if it were found that their allegations

were correct and that delay was warranted the court should

have entered judgment requiring desegregation with all

deliberate speed, or at least the submission of a plan for

desegregation with all deliberate speed. In Willis v. Walker,

136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky.), the court held:

“ I am of the opinion that an integration of the

elementary schools in Columbia and Adair County

should be effective with the beginning of the school

year in August or September, 1956. I put this

August or September as it is apparent some regis

tration is had in Adair County in August.”

# # #

“ It is further pled by the defendants that they

contemplate the construction, reconstruction or en

largement of the school buildings, within the district

and that the Adair County Board of Education has

adopted a resolution requesting the Adair County

Fiscal Court to submit to the voters of Adair County

the question as to whether an annual special school

building tax shall be levied in the district for a

period of twenty five years in order to meet the

cost of construction and equipment. It is also pled

that the Board contemplates the leasing or purchase

of additional busses but that it is without funds.

It anticipates that such funds will be available if

the necessary appropriations are made by the

General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Ken

tucky. These plans are laudable and it is hoped they

7

will eventually be carried out. It must be admitted,

however, that such plans are rather vague and in

definite and depend for their ultimate success upon

so many varied elements that they cannot be con

sidered as lawful grounds for delay of the mandate

laid down by the Supreme Court. The court does

not question the good faith of the defendants but good

faith alone is not the test. There must be ‘ com

pliance at the earliest practicable date.’ ”

In McSwain v. County Board of Education of Anderson

County, Tennessee, — F. Supp. — (E. D. Tenn.), the court

ruled:

“ It is the duty of this Court to comply with the

clear mandate of the Supreme Court. The holding

of that Court, as applied to this case, requires adop

tion by school authorities of Anderson County of a

program of integration that will expeditiously permit

the enrollment of negroes of high school grade to the

high schools of that county. The Supreme Court

stated in substance that the school authorities should

make a ‘ prompt and reasonable start’ toward that

objective. The record here indicates that Anderson

County school authorities have had this problem

under consideration from time to time, apparently

in good faith, but have as yet taken no positive

action in the way of discontinuing segregation.

“ It is the opinion of this Court that desegrega

tion as to high school students in that county should

be effected by a definite date and that a reasonable

date should be fixed as one not later than the begin

ning of the fall term of the present year of 1956.’ ’

In Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, — F. Supp.

■— (E. D. La.), a judgment was recently entered requiring

that defendants proceed to desegregate.

8

In no case of which plaintiffs know has any court held

that “ separate hut equal” , a mere answer setting forth

reasons for delay which are controverted, or even proof

of grounds for delay, justifies dismissal of the complaint.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore appellants pray that the judgment below

be reversed and that the court below enter an order

requiring defendants to desegregate the schools under

their jurisdiction “with all deliberate speed” .

Respectfully submitted,

W. J. D urham,

C. B. B unkley, Jr.,

L ouis B edford,

K enneth H olbert,

U. Simpson T ate,

J. L. T urner, Jr.,

Dallas, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

New York City,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

J ack Greenberg,

New York City,

of Counsel.