Motion to Dismiss, Or in the Alternative, To Affirm

Public Court Documents

May 25, 2000

41 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Motion to Dismiss, Or in the Alternative, To Affirm, 2000. 88ff1407-d90e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ff263b37-61b8-4d10-b49b-42cae5d05aeb/motion-to-dismiss-or-in-the-alternative-to-affirm. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

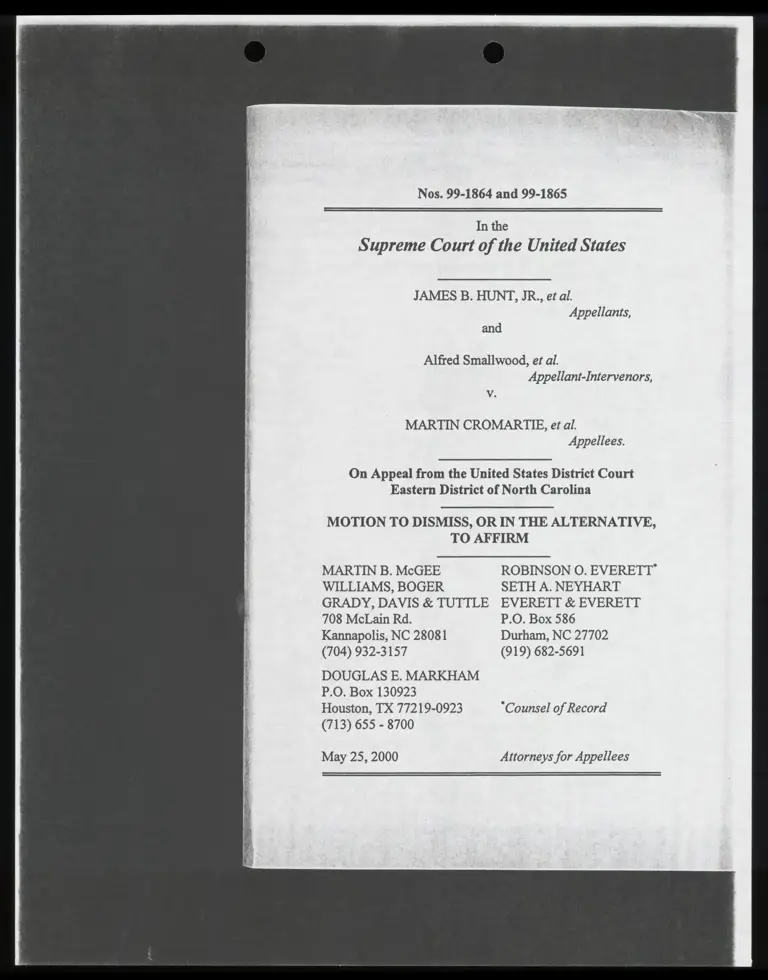

Nos. 99-1864 and 99-1865

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., et al.

Appellants,

and

Alfred Smallwood, et al.

Appellant-Intervenors,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

MOTION TO DISMISS, OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE,

TO AFFIRM

MARTIN B. McGEE ROBINSON O. EVERETT’

WILLIAMS, BOGER SETH A. NEYHART

GRADY, DAVIS & TUTTLE EVERETT & EVERETT

708 McLain Rd. P.O. Box 586

Kannapolis, NC 28081 Durham, NC 27702

(704) 932-3157 (919) 682-5691

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

P.O. Box 130923

Houston, TX 77219-0923 "Counsel of Record

(713) 655 - 8700

May 25, 2000 Attorneys for Appellees

va

Py

Ex

ie

Ao

3

&3

&

al

Eb

§ H

a

i

3

%

=

3]

u 4

i

:

3

¥

&

]

i

ro

&

=

5

i

Es

%

*

£. 5

is

57

{2

4

=

8

¥

i

=

§ &

x

0H

3

E

i%

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Is there evidence to support the district court’s

finding that race predominated in creating the

Twelfth District?

bo

Was the district court correct in finding that the

racially gerrymandered Twelfth District did not

survive strict scrutiny?

(U

S)

Did the district court properly reject Appellants’

claim preclusion argument?

4. Did the district court act within its discretion when it

prohibited use of the unconstitutional Twelfth District

in future elections?

ii

[This page is intentionally left blank.]

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ........ .. . ir svi dui,

L

II.

THE EVIDENCE AT TRIAL AMPLY SUPPORTED

THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDING OF A

PREDOMINANT RACIAL MOTIVE ............

A. Circumstantial Evidence Clearly Establishes

The Twelfth District’s Race-Based Purpose .. .

B. The Expert Testimony Supported the

Finding that Race Predominated in the

Formation of the Twelfth District ...........

C. Direct Evidence Produced at Trial Confirms

the Overwhelming Circumstantial Evidence

that the Twelfth District is Racially

12

Gerrymandered. S00. 2 oe vo Sin, 22

THE TWELFTH DISTRICT FAILS THE

STRICT SCRUTINY TEST... i. vias 25

1v

III. APPELLANTS’ CLAIM PRECLUSION

ARGUMENT LACKS MERIT ........... 5.0.

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ACTED WELL

WITHIN ITS DISCRETION IN PROHIBITING

FURTHER USE OF THE TWELFTH DISTRICT ..

CONCLUSION... i ist hte a ea F200 30 woke ithe. oa

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Anderson v. City of Bessemer,

R70 U.8864 (1983). ol. ah i 11

Bush v. Vera, :

S17:0.8:952 (1996) ........ .. hein i. 16, 21

Cromwell v. County of Sac,

U.S 331876). or, a a ae 26

Federated Dept. Stores, Inc. v. Moite,

4520.8. 30008) oo. vse NE 26

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 UU8.33001960) oo. ES 12

Hays v. Louisiana, :

936.F.Supp. 3604W.D.La. 1996) ..........0. 00. 28

Hunt v. Cromartie,

S26U.8. 541 (1999) ..... 00 oa a 34,12, 13

Klugh v. United States,

BIR F.2d 294 (4 Cir. 1987). cu hi 27

McQueeney v. Wilmington Trust Co.

JI9F.24 916 (39 Cir, 1988)... ui’ ii TR 25

vi

Miller v. Johnson,

5150.8. 800(1995) 6.5 coos vn sn The sais Ee 4 12

Public Service Comm ’n of Missouri v. Brashear Freight

Lines, Inc. 306 U.S.204 (1939) ....... 000 teas ss 6

Reynolds v. Sims,

377.1).S.533,585(1964) i... aa Saleh os 27.28

Shaw v. Hunt,

5171).8. 89941996), «sie os + vb nis she 1,25,27

Shaw v. Reno,

S09 US. 63001993)... ii. ul ome, 6,12.14

United States v. Hays,

SIS3U.S. 737(1993) cut ies vdieo e5leminian « sie niaens 26

Vera v Bush,

933 F.Supp. 1341.(S.D. Tex..1996) ..........s 28, 29

vii

STATUTES & RULES

QAUSC. 81973 ci ih Th BR Ee 4

PED: RCIVLP. 52(a) «ovo Same Bs a Td dans I

1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, ch.2, § 1.1

SECONDARY AUTHORITIES

Pildes & Niemi, Expressive Harms, “Bizarre Districts,” and

Voting Rights: Evaluating Election-District Appearances

After Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 483 (1993) ....... 13

MOTION

Pursuant to Rule 18.6 of the Rules of the Supreme

Court of the United States, Appellees move that the Court

summarily affirm the judgment sought to be reviewed, or in the

alternative, dismiss the appeal on the ground that the questions

it raises are so insubstantial as to require no further argument.

The extensive record before the district court amply supported

its findings that race predominated in drawing the Twelfth

District in the 1997 Plan and that the district failed the strict

scrutiny test. In light of these findings the court properly

concluded that this District should not be used in Congressional

primaries or elections.

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE

After over four years of legal battle requiring two

appeals to this Court, North Carolina’s “bizarre” Twelfth

District as drawn in the 1992 Plan was finally held

unconstitutional. See Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996).

Three weeks later, on July 3, 1996, Martin Cromartie and two

other registered voters in Tarboro filed a separate action in the

Eastern District of North Carolina to have the First

Congressional District also declared unconstitutional.! District

Judge Malcolm J. Howard, to whom the case was assigned,

entered a stay order and periodically extended it awaiting final

resolution of the Shaw case.

' None of the original plaintiffs in the Shaw litigation had standing to

challenge the First District because none of them resided there. On July 9,

1996, a second amended complaint was filed in Shaw, listing Cromartie and

the other two Tarboro voters in the caption as plaintiffs. (See Appellants’

J.S. App. at 283a-304a.)

2

On April 1, 1997, the General Assembly submitted its

1997 Redistricting Plan to the Shaw district court for review.

On September 12, 1997, that court filed an order approving the

1997 Plan. In so doing, however, the Court emphasized the

limited nature of its approval.’

On October 10, 1997, after termination of the Shaw

litigation in the previous month, the Cromartie plaintiffs filed

an “Amended Complaint and Motion for Preliminary and

Permanent Injunction.” This amended complaint included as

plaintiffs not only the three original plaintiffs from the First

District, but also other plaintiffs who were registered voters in

the 1997 Plan’s Twelfth District. When the State then moved

to have the Shaw panel take jurisdiction over the Cromartie

suit, that panel denied the motion; and the State did not appeal.

On January 15, 1998, the Cromartie case was

2 The district court stated:

We close by noting the limited basis of the approval of the plan

that we are empowered to give in the context of this litigation. It

is limited by the dimensions of this civil action as that is defined

by the parties and the claims properly before us. Here, that means

that we only approve the plan as an adequate remedy for the

specific violation of the individual equal protection rights of those

plaintiffs who successfully challenged the legislature’s creation

of former District 12. Our approval thus does not—cannot--run

beyond the plan’s remedial adequacy with respect to those parties

and the equal protection violation found as to former District 12.

(Appellants’ J.S. App. at 320a.)

* At the same time the State also sought to have the Shaw panel consider

a case, Daly v. Leake, No. 5: 97-CV-750-BO (E.D.N.C filed July 3,

1996), pending before what became the Cromartie panel and which

challenged not only North Carolina’s 1997 congressional redistricting

plan but also the State’s House and Senate apportionment plans.

its

ier

~

>

reassigned from Judge Howard to a three-judge district court

panel consisting of Circuit Judge Sam Ervin III, and District

Judges Terrence Boyle and Richard Voorhees. On January 30,

1998, the Cromartie plaintiffs renewed the prayer for relief

contained in their amended complaint by filing a motion for

preliminary injunction; and on February 5, 1998, they moved

for summary judgment. On March 3, 1998, defendants

responded with their cross-motion for summary judgment.

On April 3, 1998, the district court granted plaintiffs’

motions for summary judgment and for preliminary and

permanent injunctions. The defendants unsuccessfully

requested a stay from the district court and this Court. The

district court granted the legislature an opportunity to draw a

new plan (the “1998 Plan”) and to conduct the 1998

congressional primaries and elections under that plan. The 1998

Plan reduced the African-American population of the Twelfth

District to about 35% from almost 47% in the 1997 Plan.

Moreover, unlike the 1997 Plan, in which all six counties of the

Twelfth District had been divided, the corresponding district in

the 1998 Plan had one undivided county and split four others.*

The law enacting the 1998 Plan contained a proviso that

this plan would be used in the 1998 and 2000 primaries and

elections, unless the Court rendered a favorable decision in the

appeal the State was pursuing with respect to the district court’s

summary judgment for plaintiffs. See 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws,

ch. 2, §1.1. On May 17, 1999, the Court reversed the summary

judgment that had been entered in the plaintiffs’ favor. See

4

Instead of splitting four major cities—Charlotte, Winston-Salem,

Greensboro, and High Point—-as well as Statesville, Salisbury, and

Lexington, the 1998 Plan’s Twelfth District split only Charlotte and

Winston-Salem. Furthermore, the 1998 Plan accomplishes the same

purported objectives that were put forward as rationales for the 1997 Plan.

4

Hunt v. Cromartie, 526 U.S. 541 (1999). The effect of this

decision was to reinstate the 1997 Plan for use in primaries and

elections in the year 2000.

In Cromartie, the Court discussed the evidence and

concluded that, although a predominant racial motive of the

Legislature could be inferred from the plaintiffs’ evidence, the

State had raised an issue of fact to be decided in a trial. In

remanding for determination of the legislative motive, the

Court observed that “the District Court is more familiar with

the evidence than this Court, and is likewise better suited to

assess the General Assembly’s motivations.” Id. at 553-54.

Preparation for trial was extensive and was conducted

on an expedited schedule. After the sudden death of Judge

Ervin, District Judge Lacy H. Thornburg was assigned to the

panel as Circuit Judge Designate; and he presided at the trial,

which lasted from November 29, 1999 until December 1, 1999.

The plaintiffs called eight witnesses to testify and defendants

called four. The court received voluminous documentary

evidence.

On March 7, 2000, the district court delivered its

opinion, finding race the predominant motive in the creation of

the 1997 Plan’s Twelfth and First Districts. The court also

found “no evidence of a compelling state interest in utilizing

race to create the new 12" District has been presented.”

(Appellants’ J.S. App. at 29a.) On the other hand, the court

found the First District survived strict scrutiny because of the

State’s compelling interest in avoiding possible liability under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. See 42 U.S.C. §1973.

Concurrent with filing notice of appeal on March 10,

2000, Appellants requested a stay from the district court. After

denial of that request on March 13, 2000, the same day

Appellant-Intervenors gave notice of appeal, the Appellants

5

applied to this Court for a stay; it was granted on March 16,

2000.> Almost immediately thereafter Appellees moved

unsuccessfully to expedite the schedule for appeal. After

Appellants sought a thirty-day extension to file their

jurisdictional statement and Appellees filed their opposition,

the Court allowed a ten-day extension until May 19, 2000.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Neither the Appellants’ nor the Appellant-Intervenors’

jurisdictional statement raises an issue that merits the attention

of this Court. Indeed, the Questions Presented ignore the

plaintiffs’ extensive evidence’ and relate only tangentially to

the record of trial.” Moreover, Appellants disregard the

* The Court’s order dated March 16, 2000, provided that “[i]f the appeals

are dismissed, or the judgment affirmed, this order shall terminate

automatically. In the event jurisdiction is noted or postponed, this order will

remain in effect pending the sending down of the judgment of this Court.”

529 U.S. (2000).

® For example, in each jurisdictional statement the first Question Presented

refers to the Twelfth District as “somewhat irregular” or “slightly irregular”

in shape. Such a description is at odds with any “eyeball” perception of that

district as portrayed in maps thereof and with the statistics indicating that the

district is one of the least compact in the nation. The Appellants’ first

Question Presented refers to the State’s having “considered race,” but the

district court found that race was the predominant motive, a finding going far

beyond “consideration” or “consciousness” of race.

5

The Appellants’ second Question Presented asks whether the strict

scrutiny of Shaw is invoked simply by showing that the challenged district

was intentionally created as a majority-minority district. Since the Twelfth

District in the 1997 Plan was not majority-minority, this Question obviously

concerns only the First District, which the court below found to be

constitutional since it passed the test of strict scrutiny. As to that district,

6

statement made by their lead counsel at trial to the effect that

the Twelfth District involves “purely a factual matter”—whether

race had been the legislature’s predominant motive in drawing

the District. (Tr. at 31.)

At trial the plaintiffs did not rely solely on the

circumstantial evidence they presented some eighteen months

earlier in seeking summary judgment. Instead, as a result of

extensive discovery and trial preparation, they presented

additional persuasive evidence that race had been the

predominant motive in creating the 1997 Plan’s Twelfth

District. This evidence included testimony of three prominent

legislators who were serving when the 1997 Plan was enacted

and were convinced that a predominant racial motive existed.

The plaintiffs also offered testimony of several other persons

active in politics and familiar with the contours and voting

patterns of the Twelfth District. Each testified from his broad

the Appellants’ Question is misstated because the district court found that

race predominated in its creation, and the evidence amply supported this

finding. The First District in the 1997 Plan unnecessarily splits nine major

cities and towns by race, divides half of its counties, and violates

compactness and other traditional redistricting principles. Under the

circumstances described by the district court, (see Appellants’ J.S. App. at

18a, 30a), clearly Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), applies and the only

substantive issue concerning the First District is whether the district court

ruled correctly that it satisfied the test of strict scrutiny. The matter of the

First District would be a question for plaintiffs to present--if they chose to

do so—rather than for the State defendants. Appellees doubt that Appellants

even have standing at this point to seek from the Court an advisory opinion

as to whether the evidence concerning the predominance of race in the

Majority-Minority First District triggered the test of strict scrutiny. Cf.

Public Service Comm'n of Missouri v. Brashear Freight Lines, Inc., 306

U.S. 204, 206 (1939).

® Unlike the two legislators who testified for the defendants, the plaintiffs’

witnesses had no reason to offer post hoc rationalizations as to the

predominant motive of the General Assembly.

ffs’

the

7

experience that race was the only explanation for the manner in

which the Twelfth District had been drawn.

The plaintiffs offered in evidence portions of the 1997

Plan’s legislative history which made clear the predominance

of race. In addition, plaintiffs presented a “smoking gun” e-

mail authored by Gerry Cohen, who operated the General

Assembly’s computer to create the 1997 Plan.’ Cohen sent the

e-mail to Senators Roy Cooper and Leslie Winner, who both

were very involved in preparing the 1997 Plan.!° This e-mail

revealed clearly that race predominated in shaping the First and

Twelfth Districts."

* Cohen played a similar role in drawing the 1992 Redistricting Plan.

'® As a retained counsel for the General Assembly, Senator Leslie Winner

had played a major role in creating the unconstitutional 1992 Plan.

'! The e-mail, Ex. 58, was sent on February 10, 1997, and reflected, inter

alia, the change which gave the 1997 Plan Twelfth District its ultimate form.

By shifting areas in Beaufort, Pitt, Craven, and Jones

Counties, I was able to boost the minority percentage in the

first district from 48.1% to 49.25%. The district was only

plurality white, as the white percentage was 49.67%.

This was all the district could be improved by switching

between the 1% and 3" unless I went to Pasquotank,

Perquimans, or Camden. 1 was able to make the district

plurality black by switching precincts between the 1% and 4%

in Person/Franklin Counties (Franklin was all in the 1 under

Cooper 3.0, but had been in the 4" District in the 80's under

Price. By moving four precinct [sic] each way, I was able to

boost the District to 49.28% white, 49.62% Black. About

0.6% is native American (Haliwa). I could probably improve

thins [sic] a bit more by switching precincts in Granville and

Franklin between the 1st and 4th.

I have moved Greensboro Black Community into the 12th,

and now need to take bout [sic] 60,000 out of the 12th. I

await your direction on this. I am available Tuesday.

8

At tnal, plaintiffs offered as an expert Dr. Ron Weber,

a political scientist with extensive experience in redistricting

litigation.'? His detailed expert testimony, (Tr. at 143-321), and

related reports established that race clearly predominated as the

motive for drawing the Twelfth District. Appellants, on the

other hand, offered as an expert Dr. David Peterson, a

statistician who lacked prior contact with redistricting. He used

an untested methodology which had never received any peer

review and was shown to be defective and unreliable.

At the outset of the trial, counsel for Appellants

conceded that no “compelling state interest” existed to justify

the Twelfth District if the court found race had been the

predominant motive in creating that district. (See Tr. at 32.)

Counsel for Appellant-Intervenors took the same position."

(See Tr. at 596.) In any event, the district court properly found

no evidence had been offered to show any compelling state

interest or that the Twelfth District had been narrowly tailored.

Appellants seek to raise an issue of claim preclusion.

(See Appellants’ J.S., Question 3.) The district court properly

rejected this defense because the Shaw panel made clear in its

Memorandum Opinion of September 12, 1997, that claim

2 As the Court may be aware, Dr. Weber has been involved extensively as

an expert in redistricting litigation in North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana,

Virginia, and Texas.

"> Appellant-Intervenors did not raise this issue in the pretrial order or

during the trial, or offer any evidence in this regard. Under these

circumstances, Appellees are surprised that Appellant-Intervenors now

contend that the“District Court Erred by Failing to Determine Whether the

State had a Compelling Justification for Creating a Narrowly Tailored

District 12.” (Appellant-Intervenors’ J.S. at 22.) It would seem that

Appellant-Intervenors would be precluded from raising this issue on appeal

because they did not preserve it at trial.

9

preclusion would not apply.” (See Appellants’ J.S. at 2a-3a &

n.1.) Furthermore, even if the Shaw panel had intended to bind

non-parties, its order would not have this effect under familiar

principles of res judicata.

The final Question Presented by each jurisdictional

statement concerns the district court’s discretion to enjoin the

State from using the unconstitutional Twelfth District to

conduct primaries and elections this year. However, the court

below had ample precedent for enjoining use of an

unconstitutional district at this stage in the electoral process."

Appellants and Appellant-Intervenors have no basis in the

precedents they cite for overturning the district court’s decision

to prevent use of an unconstitutional congressional district."

Indeed, to allow congressional elections to take place in

North Carolina under the unconstitutional 1997 Plan would be

an abuse of discretion. The Court would be rewarding the

Legislature for its refusal to accept the instruction provided by

this Court in the Shaw litigation."” If the General Assembly had

'“ Two years earlier the district court took the same view in rejecting this

claim preclusion defense. (See Appellants’ J.S. at 245a-46a.) Apparently

neither Judge Ervin nor Judge Thornburg disagreed with the majority on this

issue.

'* For example, in the summer of 1998 the North Carolina Legislature

enacted a new redistricting plan, and congressional primaries took place that

Fall without incident. In Texas, in 1996, thirteen congressional districts

were redrawn and congressional primaries took place uneventfully at the

time of the general election.

'* The 1997 Plan had not been used previously; and so the issue was not

whether to allow continued use of a plan, but instead whether to permit the

initial use of an unconstitutional district for an election.

1 ’ Instead of applying traditional race-neutral redistricting principles, the

State seeks to retain as much as possible of the unconstitutional 1992 Plan.

The legislative history states an intent to retain in the 1997 Plan the “cores”

of the districts in the earlier 1992 Plan. In the words of Senator Cooper, the

10

proceeded promptly to enact a constitutional redistricting plan

after the district court’s decision early in March 2000,

confusion and cost could have been avoided in various ways.

Appellants now seek to invoke the problems created by their

own obstinance as the reason for compelling the district court

to allow use of the unconstitutional 1997 Plan in current

elections. The Court should not reward such tactics and deprive

the district court of the opportunity to consider the many

feasible alternatives to using the unconstitutional Twelfth

District.

ARGUMENT

I. THE EVIDENCE AT TRIAL AMPLY SUPPORTED

THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDING OF A

PREDOMINANT RACIAL MOTIVE.

Carefully adhering to the instructions of this Court on

remand, the district court conducted a three-day trial from

November 29, 1999 to December 1, 1999. It heard evidence

from twelve witnesses, received over 1100 pages of deposition

designations from seventeen depositions, and had before it over

350 trial exhibits--including 225 maps bound in seven three-

ring binders of four-inch thickness.

Sustaining the findings of fact based on this vast array

of evidence requires only that the findings not be “clearly

erroneous.” This standard of review recognizes that the trial

Twelfth District “uses as a foundation the basic core of the existing

Congressional districts. No district is dramatically changed.” Feb. 20, 1997

meeting of the Senate Committee on Congressional Redistricting, 97C-28F-

4D(2) at 3, (Ex. 100). The Twelfth District “core” obviously was viewed

in racial terms. 90.2% of the African-Americans in the 1997 Plan’s Twelfth

District had been in that district in the 1992 Plan, but only 48.8% of the

whites had been in the 1992 Plan’s Twelfth District. (See Tr. at 123.)

|

|

|

|

OO

=~

QA

7

N

U

R

11

court is better positioned to determine the facts than is an

appellate court. Cf. Feb. R. Civ. P. 52(a). Appellants have

previously asserted that “[t]he application of the principles laid

out by this Court in Shaw and its progeny is not a simple

exercise and requires an exacting and fact-intensive inquiry,”

(Appellants Application for Extension of Time to File

Jurisdictional Statement at 3), and they apparently contend that

it has become “necessary for this Court to undertake the

[factfinding] task itself” to determine whether race did in fact

predominate in the drawing of the Twelfth District. (Id, at 3-

4.) Similarly, the Appellant-Intervenors asserted that “on

appeal, this Court will have to determine what role, if any, that

race played in the redistricting process.” (Appellant-

Intervenors’ Application for Extension of Time to File

Jurisdictional Statement at 2.)

Both Appellants and Appellant-Intervenors apparently

have forgotten that “[t]he reviewing court oversteps the bounds

of its duty under Rule 52(a) if it undertakes to duplicate the role

of the lower court.” Anderson v. City of Bessemer, 470 U.S.

564, 573 (1985). “If the district court’s account of the evidence

is plausible in light of the record viewed in its entirety, the court

of appeals may not reverse it even though convinced that had it

been sitting as the trier of fact, it would have weighed the

evidence differently.” Id at 574. Moreover, “[w]here there are

two permissible views of the evidence, the factfinder’s choice

between them cannot be clearly erroneous.” Id. (citations

omitted). “This is so even when the district court’s findings do

not rest on credibility determinations, but are based instead on

physical or documentary evidence or inferences from other

facts.” Id.

The plaintiffs’ burden was “to show, either through

circumstantial evidence of a district’s shape and demographics

or more direct evidence going to legislative purpose, that race

was the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision

12

to place a significant number of voters ‘within or without a

particular district.” Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 916

(1995). The district court properly found that Appellees have

met their burden. Appellants now go so far as to maintain that

the plaintiffs’ evidence offered at trial was insufficient. This

contention seems somewhat at odds with the Court’s statement

in remanding the case for trial that “reasonable inferences from

the undisputed facts can be drawn in favor of a racial

motivation finding or in favor of a political motivation finding.”

Cromartie, 526 U.S. at 552.

Appellees construe this observation to mean that the

evidence they offered in 1998 was legally sufficient. However,

this becomes academic, because when the case was tried in

November 1999, Appellees presented not only all the evidence

previously before the district court in 1998, but also extensive

additional direct and circumstantial evidence that race

predominated as the motive for the Twelfth District. Not only

was the evidence legally sufficient to establish this, but it

overwhelmingly supported this contention. Obviously, the

district court was not “clearly erroneous” in making its findings

in accord with this evidence.

A. Circumstantial Evidence Clearly Establishes

The Twelfth District's Race-Based Purpose.

This Court has recognized that some districts are “so

highly irregular that [they] rationally cannot be understood as

anything other than an effort to ‘segregat[e] . . . voters’ on the

basis of race.” Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 646-47 (quoting

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 341 (1960)). The

Twelfth is such a district.

The undisputed facts show it to be one of the least

compact congressional districts in the Nation, ranking either

432 or 433 out of 435 districts in “perimeter compactness” and

oOo

QQ

oo

tn

O

13

430 or 431 in “dispersion compactness.” (Tr. at 206.) The

district court found the Twelfth District's dispersion score of

0.109 and its perimeter score of 0.041 were both below the

suggested “low” compactness measures articulated in Pildes &

Niemi, Expressive Harms, “Bizarre Districts,” and Voting

Rights: Evaluating Election-District Appearances After Shaw

v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 483, 571-73, tbl.6 (1993). (See

Appellants’ J.S. App. at 16a.) The Twelfth District is the only

district in the 1997 Plan with such minimal compactness and

which splits every county. The district court also found the

Twelfth District was less compact than districts elsewhere that

had previously been held unconstitutional. (See id. at 26a.)

Although the Twelfth District is somewhat wider and

shorter than its unconstitutional predecessor, it generally

follows the path of the 1992 Plan’s Twelfth District and retains

its basic “snakelike shape.” Cromartie, 526 U.S. at 544. In

fact, one legislator, in comparing the 1997 version of the

Twelfth District with its 1992 predecessor, complained that “all

you have done with the 12" District in this bill is knock sixty

miles off of it.” Mar. 26, 1997 Floor Debate of HB 586 on

House Floor 97C-28F-4F(1) at 12, (Ex. 100).

When the District’s bizarre shape is combined with its

demographics, the single unifying factor explaining its

geographical anomalies is race. As the district court found,

“[t]he only clear thread woven throughout the districting

process is that the border of the Twelfth District meanders to

include nearly all of the precincts with African-American

population proportions of over forty percent which lie between

Charlotte and Greensboro, inclusive.” (Appellants’ J.S. App.

at 25a.) The circumstantial evidence presented to the district

court exhaustively demonstrates this fact.

The Twelfth District’s total African-American

population is 46.67%, a percentage the district court doubted

was “sheer happenstance.” (/d. at 28a n.8.) The percentage of

J

African-Americans in the six counties split by the Twelfth

District is 23.6%, half of 46.67%. Guilford County has the

highest percentage of African-Americans in the six split

counties at 26.4%. The district court further found that almost

75% of the total population in the Twelfth District came from

mostly African-American portions of the three urban counties

at the ends of the district, along with parts of the three rural

counties that have “narrow corridors which pick up as many

African-Americans as needed for the district to reach its ideal

size.” (Id. at 12a.) As the district court also noted, in further

disregard of political subdivisions the Twelfth District split its

four cities and many towns along racial lines.

The district’s distorted shape, therefore, results from its

twisting through the Piedmont area of North Carolina to include

within its boundaries as many African-Americans as possible

without exceeding 50% of the total population.'® This is

depicted clearly in a map offered in evidence by Appellees."

(See Ex. 106.) As shown there, the Twelfth District starts in

Mecklenburg County near the South Carolina border and moves

north to include all 26 majority African-American precincts in

that County, as well as all precincts with an African-American

population exceeding 40%.%°

'* The General Assembly mistakenly believed that so long as the African-

American population was not a majority, Shaw v. Reno would not apply and

it would be free to draw the Twelfth District in any manner it chose in

disregard of traditional race-neutral redistricting principles. See infra note

33.

** This map is lodged with the Court, as are two other maps. Exhibit 253

shows the partisan voting performance in the 1988 Court of Appeals race in

the area of the Twelfth District. Exhibit 305 shows the evolution of the

Twelfth District from the 1992 to the 1997 and 1998 versions.

Mecklenburg County’s Precinct 77 bordering South Carolina is divided

between the Twelfth and the Ninth Districts to provide a narrow “land

bridge” between the eastern and western portions of the Ninth District. This

15

As the Twelfth District continues-its journey north out

of Mecklenburg into Iredell County, it narrows to a mere

precinct --as it does frequently in other areas of the district in

order to prevent including concentrations of white voters. Upon

reaching Statesville, it juts west to include two precincts with

high African-American concentrations. Then its path meanders

east into Rowan County, where it snakes to the south to pick up

concentrations of African-Americans in Salisbury.?! Next, the

Twelfth District moves north into Davidson County, where it

also includes all precincts exceeding 40% in African-American

population.

The district then branches into two directions--into

Forsyth County and into Guilford County. The boundaries of

the Twelfth District in Forsyth County are almost perfectly

tailored to maximize its minority population. (See Ex. 106.)

The district court observed that “[w]here Forsyth County was

split, 72.9 percent of the total population of Forsyth County

allocated to District 12 is African-American, while only 11.1

percent of its total population assigned to neighboring District

5 is African-American.” (Appellants’ J.S. App. at 12a.) In

Forsyth County only two precincts with African-American

populations less than 40% of the total population were included

in the Twelfth District. Those two precincts comprise part of

the Twelfth District’s land bridge into Forsyth County.”

“land bridge” prevents the Twelfth District from cutting the Ninth District

in half and thereby making it non-contiguous.

*! Plaintiff R.O. Everett, a Salisbury resident, testified in minute detail as

to how that town had been divided along racial lines. (Tr. at 80-100.)

= Hamilton Horton, who represents Forsyth County in the North Carolina

Senate, testified that the Twelfth District’s boundaries reflected its racial

predominance in that area by splitting Winston-Salem along racial lines,

noting that the mostly white and Democratic Salem College community was

bypassed to reach African-American areas. (See Tr. at 32-47).

16

Similarly, the branch of the district shooting into Guilford

County also includes virtually all precincts in that county with

an African-American population in excess of 40%.

As the district court found, “where cities and counties

are split between the Twelfth District and neighboring districts,

the splits invariably occur along racial, rather than political,

lines - the parts of the divided cities and counties having a

higher proportion of African-Americans are always included in

the Twelfth.” (Id at 25a.) This observation by the district court

is true whether measuring voting performance or party

registration. As Dr. Weber testified, his analysis of voting

performance was “very consistent” with a registration analysis.

(Tr. at 240.)

This can be quickly confirmed by a comparison of the

racial percentage map of the Twelfth District, Exhibit 106, and

the voting results map of the Twelfth District for the Court of

Appeals race.” (See Ex. 253.) There is some correlation

between party and boundaries of the Twelfth District; but this

correlation pales in comparison to the precision match between

the boundaries of the Twelfth District and the predominately

African-American precincts. In mixed motive cases, a line

which corresponds more precisely to racial demographic data

than partisan demographic data is important evidence of a

predominantly race-based district. See Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S.

952, 970-75 (1996).

Exhibit 106 and scores of similar maps reviewed by the

district court emphatically support its finding that race was the

predominant factor in the creation of the Twelfth District. They

show exactly why 75% of the district’s population is pulled

from the extremes of the district, why the district meanders as

2 According to Gerry Cohen, the primary draftsman for both the 1992 and

1997 plans, the 1988 Court of Appeals race was loaded onto the redistricting

computer in order to be an indicator of generic party voting strength. (See

Cohen Dep. at 49.)

gQ

A,

e

17

it does, and why it narrows to the width of a single precinct in

numerous places.*

As the district court found, Dr. Weber “showed time and

again how race trumped party affiliation in the construction of

the Twelfth District and how political explanations utterly

failed to explain the composition of the district.” (Appellants’

J.S. App. at 26a (citing Tr. at 162-63, 204-05, 221, 251, 262,

288).)

Moreover, as Dr. Weber testified, and as was

demonstrated by Congressman Watt’s comfortable re-election

under the State’s 1998 redistricting plan, a solid Democratic

performance district can be created without the contortions

contained in the Twelfth District. (See Tr. at 205, 220-21.)

** The district court also had the benefit of hundreds of other maps and

other exhibits primarily detailing breakdowns of all the measurements of

party performance as recorded in the State’s redistricting computer

according to precinct, county, and district. While the Republican victory

maps in the Appellants’ appendix are accurate, they are misleadingly

designed. They do not show the corresponding Republican victories within

the boundaries of the Twelfth District, but only the victories in the

immediate precincts outside. Nor do they show relative levels of party

support. (See Appellants’ J.S. App. at 213a-21a.)

* Appellants criticize the district court for failing to give proper deference

to the General Assembly because it noted that “a much more compact,

solidly Democratic Twelfth District could have been created.” (Appellants’

J.S. at 18 n.21.) However, the Appellants mischaracterize the language and

logic of the district court as saying that because such a district could have

been created, it should have been created. (See id) In fact, the district court

was not dictating any choice to the General Assembly by making this and

similar observations. Instead, it was attempting to determine after the fact

whether a racial or political motive had predominated. The district court

properly considered relevant the fact that the General Assembly did not

conform to standard procedures and guidelines usually employed when

drawing lines for political reasons, but rather drew a district whose shape

and demographic breakdowns conform to patterns usually found when race

is the predominant motive.

18

Approximately 95% of North: Carolina African-

Americans are loyal Democrats. Consequently, the State’s

effort to set the Twelfth District’s African-American population

at just under 50% resulted in making the district so

overwhelmingly Democratic that it cannot be explained by

partisan purposes.” Rather, it was designed to ensure that the

vast majority of those voting in the Democratic primary would

be African-American and to make sure that an African-

American Democratic nominee would win the seat.

B. The Expert Testimony Supported the Finding

that Race Predominated in the Formation of

the Twelfth District.

Dr. Weber is a nationally recognized expert in

redistricting who has been involved in nearly all the major

racial gerrymandering cases in the 1990s, as well as numerous

other redistricting cases. He also has extensive experience

assisting legislators in drawing redistricting plans. In a futile

effort to disparage his persuasive testimony in this case,

Appellants have made several misstatements to the Court.

First, they claim that the district court had followed Dr.

Weber's footsteps in not considering voter performance data.

However, as Dr. Weber testified extensively, he analyzed

voting performance and the results were “very consistent” with

a registration analysis. (Tr. at 240.)

* The district is also electorally too safe to be explained as a Democratic

political gerrymander. (See Tr. at 161-63.) Democratic candidates for other

elections conducted within the boundaries of the Twelfth District receive

voting percentages of 65% or higher. (See Tr. at 162.) The election results

contained in Dr. Weber’s analysis are considerably above the 60% threshold

used to determine whether a district provides a safe seat, (See Tr. at 162),

and they reflect a waste of some Democratic votes in order to achieve a

racial goal.

tic

her

ve

Its

old

2),

2a

19

Second, Appellants incorrectly state that the district

court, like Dr. Weber, “based its conclusion on an examination

of a few select precincts along the district’s borders, rather than

all of them.” (Appellants’ J.S. at 20.) In fact, Dr. Weber

analyzed every precinct in all six counties of the Twelfth

District. (See Weber Decl., tbl.5, Ex. 47.)

Third, Appellants insinuate that the only basis of Dr.

Weber’s opinion that race predominated was his incorrect

assumption that the State’s computer program had no political

data, as was the case for similar software in Louisiana.

(Appellants’ J.S. at 10 n.13.) However, Dr. Weber’s opinion

that race predominated was primarily based on the demographic

facts of the Twelfth District--not his belief as to what was on

the State’s computer. Also, before trial, Dr. Weber obtained the

correct information concerning the State’s computer data and

took this data into account when he testified. (See Tr. at 261 5

Fourth, Appellants contend that when Dr. Peterson used

Dr. Weber’s methodology for analyzing the split counties

according to partisan as well as racial data, this analysis

“established equally conclusively that Democratic performance

dictated the splitting of counties and towns in both Districts 12

and 1.” (Appellants’ J.S. at 10 n.13.) To the contrary, Dr.

Weber noted that the racial differences in this data were

significantly greater than the political differences. (See Tr. at

265-66.) This was also admitted by Appellants’ expert, Dr.

Peterson, on cross-examination. (See Tr. at 507-08.)

Finally, Appellants refer to Dr. Weber as having an

“ingrained personal bias,” (Appellants’ J.S. at 10 n.13), but

state that Dr. Peterson is “an unbiased statistical expert.” (Id.

at 21.) In any event, it is not the function of this Court to

-

7 Ironically, Dr. Peterson was compensated at a rate of $335.00 an hour,

which was over twice as much as what Dr. Weber--the alleged “hired gun”--

charged for his time.

20

determine which expert witness was more “biased” or

“credible.” That was the factfinding function of the district

court, which found Dr. Weber’s testimony to be convincing.

The district court also recognized that Dr. Weber had

“presented a convincing critique of the methodology” used by

Dr. Peterson. As it noted:

Dr. Weber characterized Dr. Peterson’s boundary

segment analysis as non-traditional, creating

“erroneous” results by “ignoring the core” of each

district in question. In summary, Dr. Weber found

that Dr. Peterson’s analysis and report “has not

been appropriately done,” and was therefore

“unreliable” and not relevant.

(Appellants’ J.S. App. at 27a (citations omitted).)

Dr. Peterson’s rejected analysis--the so-called “segment

analysis”--was unprecedented. Not only was he unaware of any

application of this analysis to any other political district, (see

Tr. at 508), but his “segment analysis” had not been presented

at any academic institution or published in any scholarly journal

for peer review. (Tr. at 509.) Where the analysis had used a

number of instances of faulty data--such as data indicating there

were over twice as many African-American registered voters as

African-Americans residents of a precinct--Dr. Peterson made

no attempt to correct that data. (See Tr. at 512.)

Upon careful review of Dr. Peterson’s work, it was clear

he had given no consideration to the “core” of the district.

Thus, it was irrelevant to his “segment analysis” whether or not

inner precincts in the Twelfth District--precincts not directly on

the boundary--were 100% white, 100% African-American,

100% Democrat or 100% Republican. (See Peterson Dep. at

70.) Nor did he attempt to take into account the larger scale

decisions that went into creating the Twelfth District. (See

—+

h

n

O

P

R

Q

21

Peterson Dep. at 63.) Thus, he paid no attention to whether or

not the precinct segments he considered involved rural

connector precincts or urban core precincts, or whether the

General Assembly chose to follow a county boundary in certain

areas.” (See Tr. at 511.) In his “segment analysis,” he

arbitrarily discounted approximately 80% of the total border

precincts which he deemed “convergent.” (See Tr. at 490.)

Moreover, of the segments he did consider, each was given

equal weight regardless of population or the relative differences

in their respective populations.” Instead of counting people, he

counted segments and ignored the circumstance that a long land

bridge had been constructed to connect large concentrations of

African-Americans in Mecklenburg County with similar

concentrations in Forsyth and Guilford Counties. >

These and many more flaws in Dr. Peterson’s “segment

analysis” turned his study into a meaningless mathematical

exercise unrelated to the demographic realities of the Twelfth

District. This exercise does not focus on the areas where racial

gerrymandering was possible to see if it in fact occurred.

Instead, it submerged these probative precincts in a sea of

irrelevant rural corridor precincts where there was no

* In rejecting Dr. Peterson’s analysis, the district court properly followed

the guidance given by this Court. See Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. at 972 n.1

(criticizing the dissent for ignoring “the necessity of determining whether

race predominated in the redistricters’ actions in light of what they had to

work with”).

* For example, with respect to one boundary segment, between High Point

Precincts 1 and 4, Dr. Peterson observed that seven African-Americans out

of a total registered voter population of 2,114 on the outside was a higher

proportion than four out of 1, 212 on the inside. This trivial difference, less

than .01%, was used as evidence counting against the “racial hypothesis.”

(See Peterson Dep. at 59-60.)

* Prior to the creation in 1992 of the racially gerrymandered Twelfth

District, no parts of Mecklenburg and Guilford counties had been

combined in a congressional district since 1793.

22

opportunity to racially gerrrymander. Moreover, even if the

district court had accepted at face value Dr. Peterson’s

testimony, the gist of his testimony was that he was unable to

determine whether race or party predominated over the other.

(Tr. at 487-88.) These admittedly inconclusive results lack

evidentiary value.

C. Direct Evidence Produced at Trial Confirms the

Overwhelming Circumstantial Evidence that the

Twelfth District is Racially Gerrymandered.

Appellees’ case is not purely circumstantial as

Appellants and Appellant-Intervenors have asserted to the

Court in their Questions Presented. Many contemporaneous

statements in the legislative record contradict Appellants’ post

hoc rationalizations. Moreover, three leading legislators who

were members of the General Assembly when the 1997 Plan

was enacted testified specifically that race had been the

predominant factor in its creation. Senator Hamilton Horton,

who represented Forsyth County, testified that this County and

its chief city, Winston-Salem, were split along racial lines, and

that the Twelfth District was created predominately with a

racial motive. (See Appellants’ App. at 5a.) Representative

Wood, who was the Speaker pro tem. of the House, testified

that “the 1997 Plan divided High Point and Guilford county

along racial lines for a predominantly racial motive.” (Id. at

6a.) Representative John Weatherly also testified that the

Twelfth District was drawn for predominantly racial reasons.

(See id.)

The “smoking gun” e-mail from Gerry Cohen to

Senators Cooper and Winner was also important direct

evidence. It referred to moving the “Greensboro Black

Community” into the Twelfth District from a prior plan that did

not include Greensboro citizens and the resulting need to “take

23

[a]bout 60,000 out of the 12%! (Id. at 8a.) See also full text

supra note 11.

The district court properly found this e-mail

demonstrated that the State “had evolved a methodology for

segregating voters by race, and that they had applied this

method to District 12.” (Appellants’ J.S. App. 27a.) The

district court also found that the e-mail’s discussion of plans to

“improve” the First District by “boost[ing] the Minority

Percentage” of that district was relevant “evidence of the means

by which the 1997 Plan’s racial gerrymandering could be

achieved with scientific precision.” (Appellants’ J.S. App. at

28a.)

As the district court perceived, some of the testimony

of the State’s witnesses lacked credibility. For example, the

court below doubted the claim by the state’s primary witnesses,

Senator Cooper and Representative McMahan, that there had

been no specific racial target for the Twelfth District.” Indeed,

the record is replete with indications that the State was

attempting to keep the African-American percentage in the

Twelfth District close to, but not over, 50% in order to make

>! This e-mail seems readily susceptible to the interpretation that 60,000

African-Americans had just been moved into the district and a

corresponding number of whites needed to be taken out.

** In footnote 8 of the lower court’s opinion, it stated that: “Senator Cooper

claimed that the final percentage of District 12 was sheer happenstance.

The explicit discussion of precise percentages in the e-mail belies this

characterization.” (Appellants’ J.S. App. at 28a.) Also, the district court

found that “exact racial percentages were used when constructing districts.”

(/d.) This was also shown by Representative McMahan’s statement to his

colleagues that “we have done our best--our dead level best--to draw two

Districts that are fair racially and do have one of them the majority of the

population and the other one over 46%, and that’s the very best we could

do on both sides, and we looked at this very, very closely.” House Floor

Statement of Rep. McMahan, March 26, 1997 97C - 28F - 4F(1), (Ex. 100).

24

the district immune to constitutional challenge.” The district

court concluded that Senator Cooper’s allusion to the need for

“racial and partisan balance” in the legislative record also

bolstered plaintiffs’ claim that race predominated in the

creation of District 12. (Appellants’ J.S. App. at 27a.) The

district court specifically found that Senator Cooper’s

“contention that although he used the term ‘partisan balance’ to

refer to the maintenance of a six-six Democrat-Republican split

in the congressional delegation, he did not mean the term

‘racial balance’ to refer to the maintenance of a then ten-two

balance between whites and African-Americans is simply not

# Senator Cooper said:

I believe that this new 12* District is constitutional for several

reasons. First, and maybe most importantly, when the Court

struck down the 12* District it was because the 12% District was

majority-minority and it said that you cannot use race as the

predominant factor in drawing the districts.

Well guess what! The 12* District, under this plan, is not

majority-minority. Therefore it is my opinion and the

opinion of many lawyers that the test outlined in Shaw v.

Hunt will not even be triggered because it is not a majority-

minority district and you won’t even look at the shape of the

district in considering whether or not it is constitutional.

That makes an eminent amount of sense because what is the

cutoff point for when you have the trigger of when a district

looks ugly? I think that the court will not even use the shape test,

if you will, on the 12" District because it is not majority

minority. It is strong minority influence, and I believe that a

minority would have an excellent chance of being elected under

the 12" District.

Mar. 27, 1997 Floor Debate of HB 586 in Senate Chamber, 97C-28F-

4F(2) at 5-6 (emphasis added) (Ex. 100).

8F-

25

credible.” (Id.)

II. THE TWELFTH DISTRICT FAILS THE STRICT

SCRUTINY TEST.

Appellant-Intervenors now contend that “The District

Court Erred by Failing to Determine Whether the State Had a

Compelling Justification for Creating a Narrowly Tailored

District 12.” (Appellant-Intervenor’s J.S. at 22.) This

argument is frivolous.

Neither Appellants nor Appellant-Intervenors presented

any factual or legal contention that a compelling government

interest supported the creation of the Twelfth District. Also,

the Appellants made quite clear at the opening of trial that they

were not claiming that the Twelfth District was supported by a

compelling state interest. Specifically, the Appellants’ lead -

counsel--with no dissent from Appellant-Intervenors’ attorneys

sitting at her side--stated, “we’re not arguing compelling state

interest” with regard to the Twelfth District. (Tr. at 30-31.)

Counsel for the Appellant-Intervenors only briefly addressed

the Twelfth District in his closing argument. He stated flatly

that “Ms. Smiley [Appellants’ counsel] covered our position.”

(Tr. at 595.) Further he stated that “once we understood the

law after Shaw v. Hunt, that there couldn’t be--there was no

basis for a majority-minority district in the 12*.” (Tr. at 596.)

Thus, the district court correctly found that “no evidence of a

compelling state interest in utilizing race to create the new 12%

District has been presented and even if such interest did exist,

the 12" District is not narrowly tailored and therefore cannot

survive the prescribed ‘strict scrutiny.’ (Appellants’ J.A. App.

at 29a.)

** The evasiveness and lack of candor of Appellants’ witnesses was both

impeaching evidence and substantive evidence against Appellants’ claim.

Cf. McQueeney v. Wilmington Trust Co., 779 F.2d 916 (3™ Cir. 1985).

26

III. APPELLANTS’ CLAIM PRECLUSION

ARGUMENT LACKS MERIT.

Appellants rely for preclusion on an order entered on

September 12, 1997, in the Shaw litigation which allowed use

of the 1997 Plan as a remedy for the violation of the rights of

those Shaw plaintiffs who were registered voters in the 1992

Plan’s Twelfth District. The terms of the order make clear that

it did not intend to adjudicate challenges of the constitutionality

of the 1997 Plan made by persons who had not been held to be

entitled to relief in the Shaw litigation. Thus, to preclude

Appellees’ claim would give the order an effect never intended

by the Shaw court.

Furthermore, claim preclusion requires (1) a final

judgment on the merits, (2) the same claim or claims, (3) and

the same parties. See Federated Dept. Stores, Inc. v. Moite,

452 U.S. 394, 398 (1981); Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 U.S.

351 (1876). Here none is present. The language of the

Memorandum Opinion entered by the Shaw court on September

12, 1997, leaves no doubt that the Court was not rendering a

“final judgment” as to the constitutionality of the 1997 Plan’s

Twelfth District. Instead, it only decided that the Twelfth

District was an adequate remedy for violating the Equal

Protection rights of those Shaw plaintiffs who resided in the

1992 Plan’s Twelfth District. Since the 1997 Plan removed

those persons and their entire county from the Twelfth District,

their claim is quite different from challenges of the 1997 Plan’s

Twelfth District by registered voters in that District. The

parties also are not the same. Cf. U.S. v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737

(1995). Appellees J.H. Froelich and R.O. Everett, who live in

the 1997 Plan’s Twelfth District, were not parties to the Shaw

litigation; and therefore were in no way precluded by the Shaw

panel’s order of September 12, 1997.

In a futile effort to overcome this last defect, Appellants

27

invoke a theory of “virtual representation.” They contend that

plaintiffs Froelich and R.O. Everett had been “virtually

represented” by attorney Robinson O. Everett, who is counsel

of record in the Cromartie case and had been a plaintiff in the

Shaw litigation. This contention overextends virtual

representation. See, e.g., Klugh v. United States, 818 F.2d 294

(4" Cir. 1987). Also, it ignores the circumstance that, under the

holding in Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. at 904, Robinson Everett

lacked standing to be a plaintiff in that case because he did not

reside within the 1992 Plan’s Twelfth District. Thus, he could

not have “represented” the interests of Froelich and of his

cousin, R.O. Everett, even had he sought to do so. The Court

should reject the Appellants’ defense of claim preclusion as has

every judge who has considered it.

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ACTED WELL

WITHIN ITS DISCRETION IN PROHIBITING

FURTHER USE OF THE TWELFTH DISTRICT

Appellants and Appellant-Intervenors contend that the

lower court abused its discretion by prohibiting use of the 1997

Plan’s Twelfth District in an election after it had been held

unconstitutional. Appellant-Intervenors cite some cases in

which district courts exercised their discretion to delay

imposing a remedy for an upcoming election. (Appellant-

Intervenors J.S. at 25-27.) However, they have not cited--and

Appellees cannot find--any case where a district court had

abused its discretion by enjoining the use of an unconstitutional

redistricting or reapportionment plan.

“[Olnce a State’s legislative apportionment scheme had

been found to be unconstitutional, it would be the unusual case

in which a Court would be justified in not taking appropriate

action to insure that no further elections are conducted under

the invalid plan.” Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 585 (1964).

The district court was well aware that this was not “the unusual

28

case.” Id. Familiar with the history underlying this case, the

district court recognized that Appellants had consistently

refused over many years to enact a race-neutral redistricting

plan. If any “equitable considerations” were present, they

pointed toward granting immediate relief to the Appellees,

rather than to delay. The district court was well aware that

Appellants’ did not have clean hands because they had used

post hoc rationalizations to obscure the true facts, had offered

explanations that were “not credible,” (Appellants’ J.S. App.

at 27a), and had been steadfastly “defending the indefensible.”

Hays v. Louisiana, 936 F.Supp. 360, 372 (W.D. La. 1996).

Had the Appellants done the right thing and drawn a

constitutional plan in 1993 after the Court’s first decision, they

would not be in the situation of which they now complain.

However, as in Louisiana, Appellants have reacted to the

Court’s decisions, not by repudiating racial gerrymandering, but

by adopting a new plan with a “physically modified but

conceptually indistinguishable ‘new’ [district], again violating

historical political subdivisions and ignoring other traditional

redistricting criteria.” Id. at 372. Appellants’ shameless appeal

to the lateness of the decade deserves a firm rebuke from this

Court.”

The district court knew from the 1998 experience that

the State has the capacity to organize and conduct a special

Congressional primary in the Fall if it chooses to do so.

Moreover, the district court was undoubtedly aware that many

states hold their entire primary and general election cycle in the

Fall, and that there is a “typical post-Labor Day focus” to most

political campaigns. See Vera v Bush, 933 F.Supp. 1341, 1351

** In closing argument Appellants’ lead counsel accused Appellees of

laches. This evoked from Judge Boyle the observation that “[Y]ou can’t

make the argument that the decade has run when you have been fighting this

the entire last eight years.” (Tr. at 586.)

29

(S.D. Tex. 1996).%

The district court was further aware of the danger that

if the unconstitutional district were used in the 2000 election,

the State and the Department of Justice might seek to use it as

a benchmark for the drawing of districts for the year 2002 and

thereafter.

Finally, the district court was aware that after three

elections under a flagrantly gerrymandered Twelfth District as

created by the 1992 Plan, the 1998 elections had been

conducted in a district that adhered much more to traditional

race-neutral principles. Undoubtedly, the district court realized

that to allow initial use in the 2000 election of the

unconstitutional 1997 Plan that has twice been held

unconstitutional and is clearly more racially gerrymandered than

the plan used in the 1998 election would be an insult to the

Equal Protection rights of the Appellees and other registered

voters of the Twelfth District, would offend fair-minded

persons, and would enhance distrust of both the electoral

process and the judicial process.

Appellants have engaged in legislative and legal

maneuvers which deserve no reward from the Court. Indeed, if

the Court allows this meritless appeal to go forward for

argument in the next Term, Appellants’ tactics of delay provide

them an outcome--use of the 1997 Plan--which is entirely at

odds with the result of the trial which this Court ordered in May

1999. The Court should make it clear that delaying tactics will

not succeed in attaining unconstitutional objectives.

* In 1996, in Texas a primary election was set aside and a special election

held in thirteen redrawn districts in conjunction with the high-turnout

Presidential election, and a run-off in those few districts which required it.

See Vera, 933 F.Supp. at 1351. If that remedy was within the equitable

discretion of a district court, surely enjoining in March 2000 the first use of

the unconstitutional 1997 Plan was within the discretion of the court.

30

CONCLUSION

For the above stated reasons the Court should grant

Appellees’ motion for summary affirmance of the decision

below, or in the alternative dismissal of the appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

MARTIN B. McGEE ROBINSON O. EVERETT"

WILLIAMS, BOGER SETH A. NEYHART

GRADY, DAVIS & TUTTLE EVERETT & EVERETT

708 McLain Rd. P.O. Box 586

Kannapolis, NC 28081 Durham, NC 27702

(704) 932-3157 (919) 682-5691

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

P.O. Box 130923

Houston, TX 77219-0923

(713) 655 - 8700

"Counsel of Record

May 25, 2000 Attorneys for Appellees

|

|

|