Whitcomb v. Chavis Court Opinion; Ketchum v. Bryne Court Opinion; McMillan v. Escambia County Court Opinion; Nevett v. Sides Court Opinion;

Annotated Secondary Research

June 7, 1971 - May 17, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Whitcomb v. Chavis Court Opinion; Ketchum v. Bryne Court Opinion; McMillan v. Escambia County Court Opinion; Nevett v. Sides Court Opinion;, 1971. 62a14fb5-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0167c275-4cb1-48fe-bc91-3fe0af3e6032/whitcomb-v-chavis-court-opinion-ketchum-v-bryne-court-opinion-mcmillan-v-escambia-county-court-opinion-nevett-v-sides-court-opinion. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

,Ed2d

yed. I

cism of

port of

tg this

'ly end.

r in the

t forth

whit-

165,29

1858;

'.2, 152,

ct 260

as, 377

6, 543.

ment in-

rl argu-

363

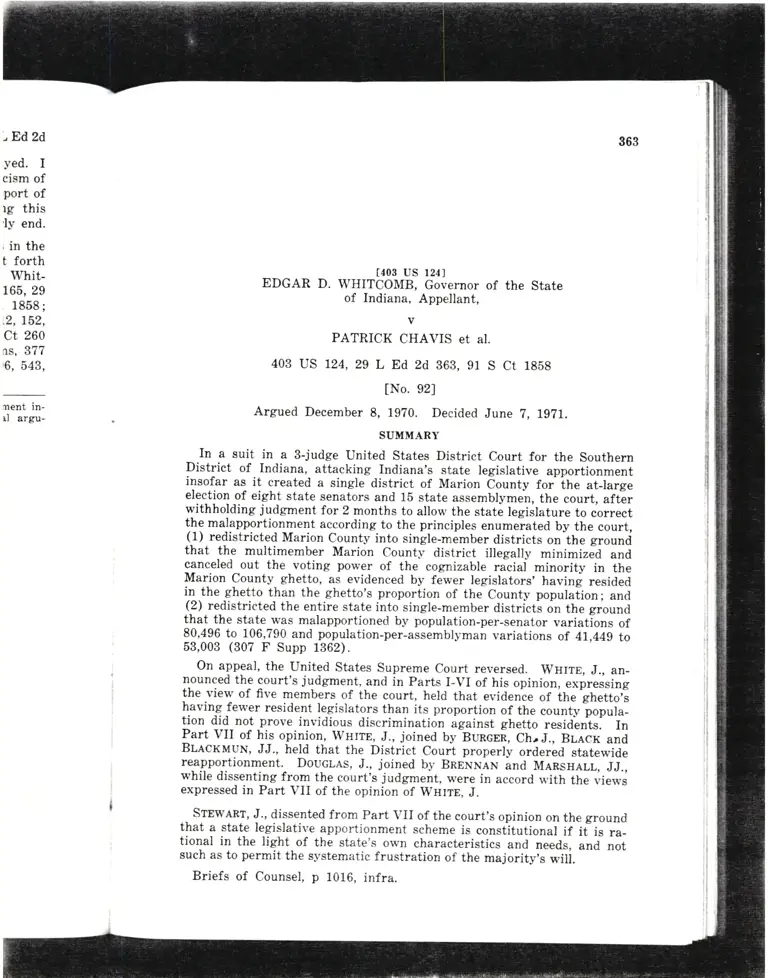

EDGAR D. wHIrS'3i\{H b2j}"-,. of the state

of Indiana, Appellant,

v

PATRICK CHAVIS et al.

403 US L24, 29 L Ed 2d 363, 91 S Ct 1858

[No. 92]

Argued December 8, 1920. Decided June Z, 1gT1.

SUMMARY

In a suit in a 3-judge united states District court for the southern

District of Indiana, attacking Indiana's state legislative apportionment

insofar as it created a single district of Marion county for ihe at-large

election of eight state senators and 1b state assemblym"n, th" court, aftir

withholding judgment for 2 months to allow the state legislature to correct

the malapportionment according to the principles enumerated by the court,

(1) redistricted Marion county into single-member districts on the g"ourd

that the multimember Marion county district illegally minimized and

canceled out the voting power of the cognizable "rliri minority in the

Marion county ghetto, as evidenced by fev'er legislators' having resided

in the ghetto than the ghetto's proportion of the county popula[ion; and

(2) redistricted the entire state into single-member districts on the g"ornd

that the state was malapportioned by population-per-senator variations of

80,496 to 106,790 and population-per-assemblyman variations of 4\,44g to

53,003 (307 F Supp 1362).

on appeal, the united States supreme court reversed. wHIrE, J., an-

nounced the court's judgment, and in parts I-vI of his opinion, expressing

the view of five members of the court, held that evidence of the ghetto{

having fewer resident Iegislators than its proportion of the county popula-

!r, {i4 not prove invidious discrimination against ghetto residLnts. In

Part VII of his opinion, WHrrE, J., ioined Uy guncBi, Ch, J., Bucx andBucruuN, JJ., held that the District courl properly ordered statewide

reapportionment. Douclas, J., joined by BnrNN.lN ind M.lnsn,ur,, JJ.,

while dissenting from the court's judgment, were in accord vvith the ui"*,

expressed in Part VII of the opinion of Wslrn, J.

sTnwlnr, J., dissented from part vII of the court's opinion on the ground

that a state legislative apportionment scheme is constitutional if ii is ra_

tional in the light of the state's own characteristics and need.s, and not

such as to permit the systematic frustration of the majority,s will.

Briefs of Counsel, p 1016, infra.

364 U. S. SUPRE}IE COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

HIBLAN, J., filed a separate opinion declaring that he would reverse

and remand with directions to dismiss the complaint on the ground that

the federal courts cannot restructure state electoral processes.

Doucl,.ls, J., joined by BnoNNeN and Mlnsxell,, JJ., dissented on the

grounds that multimember legislative districts are unconstitutional where

there are invidious effects, and that invidious effects had been proved in

this case. '

HEADNOTES

Classified to U. S. Supreme Court Digest, Annotated

Appeal and Error S 327 - appellate ance with the court's plan, and retain-

jurisdiction ing jurisdiction to pass on any future

1. The supreme court lacks juris- claims of unconstitutionality with re-

diction of and accordingly must dis- spect to any future legislative appor-

miss an appeal following a 3-judge tionments adopted by the state is not

District Court's opinion where, at the rendered moot by the holding of the

time the appeal was taken, no judg- 1970 elections and the adoption of new

ment had been entered and no injunc- apportionment legislation, not only be-

tion had been granted or denied. cause of the court's retention of juris-

Appeal and Error S f660 - mootness diction to pass on the legality of new

-2-.

An appeal from a federal court apportionment legislation in view of

decree enjoining state officials from its decision, but also because state

conducting any elections under exist- court invalidation of the new legis-

ing apportionment statutes, ordering lation would require reexamination of

that 1970 elections be held in accord- the same issues'

TOTAL CLIENT-SERVICE LIBRARY@ REFERENCES

25 Arvr Jun 2d, Elections $ 25

9 Au Jun Pl & Pn Fonus (Rev ed), Elections, Forms 7, 8, 10

US L Eo DIGEsr, Constitutional Law S 33a; Legislature $ 6

ALR Dtcpsts, Elections $$ 103, 104

L Eo INonx ro ANNo, Constitutional Law; Legislature; One

Man-One Vote

ALR QutcK INDEX, Elections

FponRlt, Qutcx INDEX, Elections; One Man-One Vote Rule

ANNOTATION REFERENCES

To what governmental agencies, Inequalities in population of election

units, officers, or subdivisions of a districts or voting units as rendering

state, other than the state legislature, apportionment unconstitutional. L2

is the "one man-one vote" rule appli- L Ed 2d 1282.

cable. 18 L Ed 2d 163?. Constitutionality and construction

Race discrimination. 94 L Ed 1121, of statutes providing for proportional

96 L Ed 1291, 98 L Ed 882, 100 L Ed representation or other system of

488, 3 L Ed 2d 1556, 6 L Ed 2d 1302, preferential voting in public elections.

10 L Ed 2d 1105, 15 L Ed 2d 990, 21 110 ALR L62r,123 ALR 262.

L Ed 2d 916.

Citizensh

parti

3. Eacl

inalienab

participa

of his st:

Elections

of vr

4. The

mands t

equally e

of membr

Constitut

porti

5. APP'

give the

tives to t

ents un

value of

tricts.

Constitut

ment

6. The

quires th

of bicam

portioned

tion basir

Constitut

meml

7.4 r

trict is r

equal pr,

Courts g

8. The

electoral

able issur

Constitut

meml

9. Mull

systems r

where th

ticular c:

or cancel

racial or

ing popu

district ir

tial prop,

house of

where it

houses o1

lacks pro'

running I

subdistrir

IVHITCOMB

,103 us 121, 29 L Ed

Citizenship S 2 - lesislative bodies -participation

3. Each and every citizen has an

inalienable right to full and effective

participation in the political processes

of his state's legislative bodies.

Elections S 3 - legislature - equality

of votes

4. The Federal Constitution de-

mands that each citizen have an

equally effective voicd in the election

of members of his state legislature.

Constitutional Law S 334 - malap-

portionment

5. Apportionment schemes rvhich

give the same number of representa-

tives to unequal numbers of constitu-

ents unconstitutionally dilute the

value of the votes in the larger dis-

tricts.

Constitutional Law S 334 - apportion-

ment

6. The equal protection clause re-

quires that the seats in both houses

of bicameral state legislature be ap-

portioned substantially on a popula-

tion basis.

Constitutional Law S 334 - multi-

member districts

7. A multimember electoral dis-

trict is not per se illegal under the

equal protection clause.

Courts S 236.5 -

justiciable issues

8. The validity of multimember

electoral district systems is a justici-

able issue.

Constitutional Law $ 334 - multi-

member districts

9. Multimember electoral district

systems may be subject to challenge

where the circumstances of the par-

ticular case may operate to minimize

or cancel out the voting strength of

racial or political elements of the vot-

ing popuiation, especially where the

district is large and elects a substan-

tial proportion of the seats in either

house of a bicameral legislature, or

where it is multimembered for both

houses of the legislature, or where it

lacks provision for at-large candidates

running from particular geographical

s ubdi stricts.

v CHAVIS

2d 363, 91 S Ct 1858

Evidence S 101 - burden of proof -invalidity of statute

10. The challenger carries the bur-

den of proving that multimember dis-

tricts unconstitutionally operate to

dilute or cancel the voting strength

of racial or political elements.

Evidence S 90.1.3 - invalidity of multi-

member districts

11. A mathematical anal;rsis of the

voting po$'er of residents of multi-

member districts, on the hypothesis

that the true test of voting porver

is the ability to cast tie-breaking

votes, but theoretical and omitting

any political or other factors which

might affect the residents' actual

voting power, such as party afhlia-

tion, race, previous voting character-

istics, or any other factors which

enter into the entire political vot-

ing situation. does not sufficiently

demonstrate the real-life impact of

multimember districts on individual

voting power to warrant holding such

districts to be constitutionally imper-

missible.

Constitutional Law S 334 - multi-

member districts

12. Even if the legislative delega-

tion from a multimember district

tends to bloc-voting, a multimember

district does not overrepresent its

voters, as compared with voters in

single-member districts, so as to be

constitutionally impermissible.

Civil Rights S2 constitutional

amendments

13. The Civil War Amendments of

the Constitution were designed to pro-

tect the civil rights of Negroes.

Evidence S904.3 - discrimination

14. Absent evidence and findings

Lhat ghetto residents had less oppor-

tunity than other residents of a mul,

member legislative district to

ticipate in the political process'

to elect legislators of their c)

vidious discriminaton agai'

not shou'n by the fact tb

has fewer legislators /

365

366

than its proportion of the district pop-

ulation.

Constitutional Law S 331 - multi-

member districts

15. That one interest group or an-

other concerned rvith the outcome of

elections in a multimem\pr legislative

district has found itself outvoted and

without legislative seats of its own

provides no basis for invoking consti-

tutional remedies where there is no

indication that this segment of the

population is being denied access to

the political s)'stem.

Constitutional Law S 334 - multi-

member districts

16. District-based elections de-

cided by plurality vote are not uncon-

stitutional in either single-member or

multimember legislative districts sim-

ply because the supporters of losing

candidates have no legislative seats

assigned to them.

CourtsST-powers t/

17. The remedial powers of an

equity court must be adequate to the

task, but they are not unlimited.

Legislature S6 - malapportionment

- remedy

18. A United States District Court

errs in disestablishing an entire coun-

tyrvide multimember legislative dis-

trict and creating single-member dis-

tricts therein in contravention of state

apportionment policy, manifested by a

state constitutional provision forbid-

ding the division of any county for

senatorial apportionment, and with-

out expressly putting aside on sup-

portable grounds the alternatives of

(1) creating single-member districts

in the county's ghetto and leaving the

district otherwise intact or (2) re-

quiring that some at-large candidates

each year reside in the ghetto.

Legislature S6 - malapportionment

- relief

19. A United States District Court

properly orders statewide legislative

redistricting where one district had

80,496 residents for one senator while

another district had 106,790 residents

U. S. SUPRE}IE COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

for one senator. one district had 41,449

residents for one representative while

another district had 53,003 residents

for one representative, and the court

refrained from action until the state

legislature ignored the court's find-

ings and suggestion that it call a

special session for the purpose of re-

districting. IPer White, J., Burger,

Ch. J., Black, and Blackmun, JJ. Ac-

cord, Douglas, Brennan, and llarshall,

JJ. ]

Legislature S6 - malapportionment

- relief

20. In reapportioning a state's leg-

islative districts, a Llnited States Dis-

trict Court acts properly in dividing

some counties into several districts,

notlvithstanding a state constitutional

provision that no county shall ever be

divided for senatorial apportionment,

where none of the statervide redis-

tricting plans submitted for the

court's consideration follow the state

constitution in this respect. and rvhere

the court strives to preserve the in-

tegrity of county and totvnship lines

wherever possible, although it ulti-

mately concludes that the difficulty of

devising compact and contiguous dis-

tricts within a framework of mathe-

matical equality largely precludes

preservation of county lines. fPer

White, J., Burger, Ch. J., Black, and

Blackmun, JJ. Accord, Douglas, Bren-

nan, and Marshall, JJ.l

Courts S 775 - adherence to former

decision

21. A 1965 decision of the United

States District Court, upholding a

state's legislative apportionment un-

der the "substantial equality" test

of Reynolds v Sims (1964) 377 US

533, 12 L Ed 2d 506, 84 S Ct 1362,

does not render the legislative appor-

tionment beyond attack, on the grounds

that disparities among districts

thought to be permissible at the time

of the Reynolds Case have been shown

by intervening Supreme Court deci-

sions to be excessive. IPer White, J.,

Burger, Ch. J., Black, and Blackmun,

JJ. Accord, Douglas, Brennan, and

Marshall, JJ.l

lYilliar

James

Briefs

t{

llr. Justice

opinion of the

the validity

election distri

Indiana (Part

an opinion (Pr

Chief Justice,

Mr. Justice BI

propriety of

of the entire

announced tl

Court.

We have b

the validity t

tection Clausr

tricting and a

of Indiana for

elections. Th

ters on those 1

Marion Count

city of Indiane

district for el

and representr

Indiana has

assembly cons

l. As later ind

nouncement of tt

informed that tl

will soon be supe

ment legislation

Indiana Legislatu

ernor. That legis

member districtl

including llarion

stated below the

and, as will be e

ceeds as though

us remain undistr

2. The provisio

.{ets 1965 (2d S1

c. 4, S 3, and ap;

SS 34-102 and 3{-

lows:

"34-102. App,

I ioea.-Re presentr

from districts cr

IVHITCOIIB v CHAVIS 367

103 LiS 12{,:19 L Ed:d 363,91 S Ct 1858

APPEARANCES OF COUNSEL

\Yilliam F. Thompson argued the cause for appeilant.

James Manahan argued the cause for appellee.

Briefs of Counsel, p 1016, infra.

OPINION OF

t{03 us t27l

11r. Justice lVhite delivered the

opinion of the Court with respect to

the validity of the firulti-member

election district in Marion County,

Indiana (Parts I-VI), together with

an opinion (Part VII), in rvhich The

Chief Justice, lIr. Justice Black, and

Mr. Justice Blackmun joined, on the

propriety of ordering redistricting

of the entire State of Indiana, and

announced the judgment of the

Court.

We have befr;re us in this case

the validity uncler the Equal Pro-

tection Clause of the statutes dis-

tricting and apportioning the State

of Indiana for its general assembly

elections. The principal issue cen-

ters on those provisions constituting

Marion County, which includes the

city of Indianapolis, a multi-member

district for electing state senators

and representatives.

I

Indiana has a bicameral general

assembly consisting of a house of

THE COURT

representatives of 100 members and

a senate of 50 members. Eight of

the 31 senatorial districts and 25 of

the 39 house districts are multi-

member clistricts, that is, districts

that :rre represented by trvo or

more

ir03 us l28l

legislators elected at large by

the voters of the district.l Under

the statutes here challenged, Marion

County is a multi-member district

electing eight senators and 15 mem-

bers of the house.

On January 9, 1969, six residents

of Incliana, five of whom were resi-

dents of Marion County, filed a suit

described by them as "attacking the

constitutionality of two statutes of

the State of Indiana which provide

for multi-member districting at

large of General Assembly seats in

Marion County, Indiana . .",

Plaintiff.s3 Chavis, Ramsey, and Bry-

ant alleged that the two statutes

invidiously diluted the force and

effect of the vote of

I{03 US l29l

Negroes and

l- As later indicated, shortly before an-

nouncement of this opinion. the Court was

informed that the statutes at issue here

will soon be superseded by new apportion-

ment legislation recently adopted by the

Indiana Legislature and signedby theGov-

ernor. That legislation provides for single-

member districts throughout the State

including Marion County. For the reasons

stated below the controversy is not moot,

and, as will be evident, this opinion pro-

ceeds as though the state statutes beiore

us remain undisturbed by new legislation.

2. The provisions attacked, contained in

.{cts lg65 (2d Spec. Sess.), c. b, g 3, and

!.^ 1, S 3, and appearing in Ind .{nn Stat

IS 3{-102 and J4-10{ ( 1969) were as fol-

lows:

.. "3{-102. Apportionment of rcprescnta-

ttuee.-Representatives shall be electedfrom districts comprised of one tf] or

more counties and having one [1] or more

representatives, as follows: Twen-

ty-sixth District Ilarion County: fifteen

[15] representatives . ."

"34-10.1. Apportionment of senators.-

Senators shall be elected from districts,

comprised of one or more counties and

having one or more senators, as follows:

. Nineteenth District-Marion Coun-

ty: eight [8] senators, two [2] to be

elected in 1966."

The District Court denied plaintiffs'

motitrn to have the suit declared a class

action under Fed Rule Civ Proc 23 ( b) .

305 F Supp 1359, 1363 (SD Ind 1969).

Se,e n. 17, infra.

3. Plaintiffs in the trial court are ap-

pellees here and defendant Whitcomb is

the appellant. lVe shatl refer to the par-

ties in this opinion as they stood in the

trial court.

368 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

poor persons living within certain

Marion County census tracts con-

stituting what was termed "the

ghetto area." Residents of the area

were alleged to have particular dem-

ographic characteristics rendering

them cognizable as a minority in-

terest group with distinctive inter-

ests in specific areas of the substan-

tive law. With shgle-member dis-

tricting, it was said, the ghetto area

would elect three members of the

house and one senator, rvhereas un-

der the present districting voters in

the area "have almost no political

force or control over legislators be-

cause the effect of their vote is can-

celled out by other contrary interest

groups" in Marion County. The

mechanism of political party organ-

ization and the influence of party

chairmen in nominating candidates

were additional factors alleged to

frustrate the exercise of power by

residents of the ghetto area.

Plaintiff Walker, a Negro resident

of Lake County, also a multi-member

district but a smaller one, alleged

an invidious discrimination against

Lake County Negroes because Mar-

ion County Negroes, although no

greater in number than Lake County

Negroes, had the opportunity to in-

tluence the election of more legisla-

tors than Lake County Negroes.{

The claim was that Marion County

rvas one-third larger in population

and thus had approximately one-

third more assembly seats than

Lake County, but that voter influ-

ence does not vary inversely with

populatiop and that permitting

Marion County voters to elect 23

assemblymen at large gave them a

clisproportionate advantage over

voters in Lake County.s The

tr03 us r30l

two re-

maining plaintiffs presented claims

not at issue here.8

A three-judge court convened and

tried the case on June 17 and 18,

1969. Both documentary evidence

and oral testimony were taken con-

cerning the composition and char-

acteristics of the alleged ghetto

area, the manner in which legisla-

tive candidates were chosen and

their residence and tenure, and the

performance of Marion County's

delegation in the Indiana general

assembly.T

The thr,

opinion cor

conclusions

for plaintif

305 F Sup

See also 3,

(pre-trial t

1362 (1969

ment plan :

In sum, it

County's

must be dit

of populatir

related to I

the compla

be redistri,

it first de

minority g

tifiable ghe

That area,

were unrepr(

and that Neg

er and oppo

assemblymen

power of po

ments was c

assembly elt

or the other I

minor excepl

numbers larl

so located as

or more gen(

County werr

without repr

assembly ele

The defer

County's pr<

that its dele

the various i:

ed at large r

as a whole

single-memb,

mented by p

ies. They

census figur

for redistric

posed the co

portionment

issue proper

pleadings ar

8. A ghett

area with a

and greater

housing thar

area and inl

I29 L Ed 2d

4. Walker also alleged that "in both

Lake and Marion County, Indiana there

are a sufficient number of negro [sic]

voters and inhabitants for a bloc vote by

the said inhabitants to change the result of

any election recently held."

5. The mathematical basis for the as-

sertion was set out in detail in the com-

plaint. See also n. 23, infra. It was also

alleged that "[b]oth Marion County

and Lake County are the sole

matter for consideration before two sep-

arate state legislative committees, one

directed to the affairs of each county.

The laws enacted which directly

effeet [sic] Marion or Lake County

typically apply to only one county or the

other." App. 15.

6. Plaintiff Marilyn Hotz, a Republican

and a resident of what she described as the

white suburban belt of Marion County

lying outside the city of Indianapolis, al-

leged that malapportionment of precincts

in party organization together with multi-

member districting invidiously diluted her

vote.

Plaintiff Rowland Allan (spelled "A1-

len" in the District Court's opinion), an

independent voter, alleged that multi-

member districting deprived him of any

chance to make meaningful judgments on

the merits of individual candidates because

he was confronted with a list of 23 can-

didates of each party.

7. In their final arguments and proposed

findings of fact and conclusions of law

plaintiffs urged that the Center Township

ghetto was largely inhabited by Negroes

who had distinctive interests and whose

bloc voting potential rvas canceled out by

opposing interest groups in the at-large

elections held in Marion County's multi-

member district, that the few Negro

legislators, including the three then serv-

ing the general assembly from Marion

County, were chosen by white voters and

WHITCONIB

103 US 121, 29 L Ed

tr03 US 1311

The three-j udge court filed its

opinion containing its findings and

conclusions on July 28, 1969, holding

for plaintiffs. Chavis v Whitcomb'

305 F SuPP 1364 (SD Ind 1969)'

See also '3Of f SuPP 1359 (1969)

(pre-trial orclers) and 307 F SUPP

rioz t 1969) (statewide reapportion-

ment plan and implementing order) '

In sum, it concluded thot Marion

County's multi-member district

must be disestablished and, because

of population disparities not directly

retatea to the phenomena alleged in

the complaint, the entire State must

be redistricted. More particularly'

it first determined that a racial

minority group inhabited an iden-

tifiable ghetto area in Indianapolis'E

That area, located in the northern

2d 363, 91 s ct 1858

half of Center Township and termed

the "Center Torvnship ghetto," com-

prised 28 contiguous census tracts

and parts of four others'e The area

contained a 1967 PoPulation

v CHAVIS

tJ03 us 1321

369

of 97,-

000 nonwhites, over 99% of whom

were Negro, and 35,000 whites' The

court proceeded to compare six of

these tracts, representative of the

area, with tract 211, a Predominant-

ly white, relatively wealthy subur-

ban census tract in Washington

Township contiguous to the north-

west corner of the court's ghetto

area and with tract 220, also in

Washington TownshiP, a contiguous

tract inhabited bY middle class

Negroes. Strong differences were

touna in terms of housing condi-

tions, income and educational levels,

were unrepresentative of ghetto Negroes'

"r,d

thrt l.i"g"*. should be given-the pow-

.i-""a opp6rtunity to choose their own

".."-ifv,i'ti,r.

It was also urged that tte

p"*"" ,it political as well as racial ele-

ments wai canceled out in that in every

assembly election since 1922, one party

or the oiher had *'on all the seats rvith two

minor exceptions; hence many voters, -in

numbers laige enough and geographically

so located as to command control over one

or more general assembly seats if Marion

County were subdistricted, were wholly

without representation whichever way an

assembly election turned out.

The defendants argued that Marion

County's problems were countywide and

that iis delegation could better represent

the various interests in the county if elect-

ed at large and responsible to the county

as a wholle rather than being elected in

single-member districts and thus frag-

ntunted by parochial interests and jealous-

ies. They- also urged that the 1960

census figures were an unreliable basis

for redistricting Marion County and op-

posed the court's suggestion that the ap-

portionment of the whole State was an

issue properly before the court on the

pleadings and the evidence.

8. A ghetto was defined as a residential

area with a higher density of population

and greater pioportion of substandard

housing than in ihe overall metropolitan

area and inhabited primarily by racial or

[29 L Ed 2dl-24

other minority groups with lower than

.""."g" socioeconomic status and whose

.u.-ia.-".. in the area is often the result

oi-, .oci"t, legal, or economic restriction

or custom. 305 F SuPP, at 1373'

9. The court's ghetto area was not con-

""r"n1--i"iit

that-alleged in the complaint'

i;

-i";l";;a five census tracts and parts

;i i;;; others not within the ghetto area

;i#; ;; ih" comPlaint, but it- omitted

cens=us tract 220 which the complatnt-nao

ii"i"a..i.

-io5 F Supp, at 13?9-1381' That

a'i.irf.t. which was contiguous to both

tract 211 and the ghetto area' was rn-

;;itJ primarilY bY Negroes b9! Yas

i;;il;" [L u -iait" class district differing

.rl]a"iftttv in critical elements from the

."*rf"a.i ,it ihe ghetto' The court also

;;;' li unmistakably clear that its

shetto area "does not represent the entlie

ehettoized portion of Center 'I'ortr-nsnrp

;;a;;iy the portion which is predominant-

i.I-i"ii.tit"a bv Negroes and which was

"if.e"J

in the-complaint"' 305 F Supp'

,i'1140-iser. Although census tract 563'

"-ti""i "randomly selected to typify tracts

.

'.- . within ihe predominantly white

gt"tto po.iiot of Cenler Township"' id''-at

iii4; ;"t shown to have characteristics

rliu' .i.ifrt to the tracts in the court's

gi"lto

"t""

except for the race of its

i;;;itr.t=, the size and configuration.of

i'fr.-*f,it" ghetto area were not revealed

by the findings'

370

rates of unemployment, juvenile

crime, and welfare assistance. The

contrasting characteristics between

the court's ghetto area and its in-

habitants on the one hand and tracts

211 and 220 on the other indicated

the ghetto's "compelling interests in

such legislative areas as urban re-

newal and rehabilitation, health

care, employment training and op-

portunities, welfare, and relief of

the poor, law enforcement, quality

of education, and anti-discrimina-

tion measures." 305 F Supp, at

1380. These interests were in addi-

tion to those the ghetto shared with

the rest of the county, such as met-

ropolitan transportation, flood con-

trol, sewage disposal, and education.

The court then turned to evidence

showing the residences of Marion

County's representatives aud sena-

tors

t403 us 1331

in each of the five general as-

semblies elected during the period

1960 through 1968.r0 Excluding

tract 220, the middle class Negro

district, Washington Township, the

relatively wealthy suburban area in

rvhich tract 21L was located, with

an average of. 1338% of Marion

County's population, was the resi-

dence of.47.52/o of its senators and

34.33% of its representatives. The

court's Center Township ghetto

area, with 17.8% of the population,

had 4.75% of the senators and

5.97% of the representatives. The

nonghetto area of Center Township,

with 23.32% of the population, had

done little better. Also, tract 220

U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

alone, the middle class Negro dis-

trict, had only 0.66% of the county's

population but had been the resi-

dence of more representatives than

had the ghetto area. The ghetto

area had been represented in the

senate only once-in 1964 by one

senator-and the house three times

-with one representative in 1962

and 1964 and by two representatives

in the 1968 general assembly. The

court found the "Negro Center

Torvnship Ghetto population" to be

sufficiently large to elect trvo repre-

sentatives and one senator if the

ghetto tracts "were specific single-

member legislative districts" in

Marion County. 305 F Supp, at

1385. From these data the court

found gross inequity of representa-

tion, as determined by residence of

legislators, betrveen Washington

Toivnship and tract 220 on the one

hand and Center Township and the

Center Township ghetto area on the

other.

The court also characterized Mar-

ion County's general assembly dele-

gation as tending to coalesce and

take common positions on proposed

legislation. This was "largely the

result of election at large from a

common constituency, and obviates

representation of a substantial,

though minority, interest group

within that common

t{03 Lrs l34l

constituency."

Ibid. Related findings were that,

as a rule, a candidate could not be

elected in Marion County unless his

party carried the election;rr county

Votes

144,336

144,235

L44,032

143,989

L43,972

lZe L Ed zdl

political orga

tial influence

election of as

influence tha

by single-me

well as upon I

ty's delegatio

that at-large

cult for the

make a ratior

The court's

the merits r

follows:

1. There (

County an i

ment, "the N

Center Torvns

cial interests i

l4

stantive law,

from interesl

the ghetto.lr

2. The vot

racial group I

Marion Count

Democrats

Jones .

DeWitt

Logan .

Roland

Walton . ,

Huber

Costello

Fruits

Lloyd

Ricketts

Though nearly

House, the high

votes. And, as

ceived 48.699? o

12. "The firgt

Fortson v Dorse3

that of an ideni

element within t

is met by the Net

Torvnship Ghetto

have interests in

such as housing

welfare prograrr

dependent childr

garnishment stal

compensation, am

10. See Appendix to opinion, post, 164, the importance of party alfiliation and the

29 L Ed 2d 389. "winner take all,, effect is shown by the

ll. A striking but typical example of 1964 llouse of Representatives etection.

Democrata

Neff

Bridwell

Murphy

Dean

Creedon

Votee Repttblicane

151,822 Cox

151,756 lladley

15L,7 46 Baker

15L,702 Burke

151,5?3 Borst

political organizations had substan-

ii"l inflrence on the selection and

election of ;rssembly candidates (an

influence that would be diminished

b]' single-member districting), as

rvell as upon the actions of the coun-

ty's delegation in the assemblY; and

that at-large elections made it diffi-

cult for the conscientious voter to

make a rational selectiotl.

The cottrt's conclusions of law on

the merits may be summarized as

follows:

l. There exists within Marion

County an identifiable racial ele-

ment, "the Negro residents of the

Center Township Ghetto," with spe-

cial interests in various areas of

t1o3 us 1351

sub-

stantive law, diverging significantly

from interests of nonresidents of

the ghetto.u

2. The voting strength of this

racial group has been minimized bY

Marion County's multi-member sen-

WHITCOMB V CHAVIS

{03 us r2.1, 29 L Ed 2d 363, 91 S Ct 1858

37r

ate and house district because of the

strong control exercised by political

parties over the selection of candi-

dates, the inability of the Negro

voters to assure themselves the op-

portunity to vote for prosPective

legislators of their choice and the

rrtrsence of any particular legislators

who were accountable for their leg-

islative record to Negro voters.

3. Party control of nominations,

the inability of voters to know the

candidate and the responsibility of

legislators to their party and the

county at large make it difficult for

any legislator to diverge from the

majority of his delegation and to be

an effective representative of minor-

ity ghetto interests.

4. Although each legislator in

Nlarion County is arguably respon-

sible to all the voters, including

those in the ghetto, "[p]artial re-

sponsiveness of all legislators is

[not] equal [to] total re-

sponsiveness and the informed con-

cern of a few specific legislators."ls

ll

t:

ti

l!

Democrats

Jones

DeWitt

Logan

Roland

Walton . .

Huber

Costello

Fruits

Lloyd

Ricketts

Votes

151,481

151,449

151,360

151,343

r't,282

151,268

151,153

151,079

150,862

150,797

Elder

Zerfas

Allen

Votos

143,918

143,853

143,810

L43,744

143,688

143,553

L43,475

143,436

143,413

143,369

Repttblicans

Madinger

Clark

Bosma

Browrr

Durnil

Gallagher . .

Cope

Though nearly 300,000 Marion County voters cast nearly 4l million votes for the

House, the high and low candidates within each party varied by only about a thousand

votes. And, as these figures show, the Republicans lost every seat though they re-

ceived 48.69f? of the vote. Plaintiffs' Exhibit 10.

12. "The first requirement implicit in

Fortson v Dorsey and Burns v Richardson,

that of an identifiable racial or political

element within the multi-member district,

is met by the Negro residents of the Center

Township Ghetto. These Negro residents

have interests in areas of substantive law

such as housing regulations, sanitation,

welfare programs (aid to families with

dependent children, medical care, etc.),

garnishment statutes, and unemployment

compensation, among others, which diverge

significantly from the interests of non-

residents of the Ghetto." 305 F Supp, at

1386.

13. Ibid. The District Court implicitly,

if not expressly, rejected the testimony of

defendants' witnesses, including a profes-

sor of political science, to the effect that

Marion County's problems and all its

voters would be better served by a delega-

tion sitting and voting as a team and re-

sponsible to the district at large, than by

a delegation elected from single-member

372

t{03 us 1361

5. The apportionment statutes of

Indiana as theY relate to Marion

County oPerate to minimize and

.un."i out the voting strength of a

minority racial group' namelY Ne-

groes residing in the Center Town-

ihip ghetto, and to dePrive them of

ths equal Protection bf the laws'

6. As a legislative district, Marion

County is large as compared with

the total number of legislators, it is

not subclistricted to insure distribu-

tion of the legislators over the coun-

ty and comPrises a multi-member

clistrict for both the house and the

senate. (See Burns v Richardson,

384 US ?3,88, 16 L Ed 2d 376,388,

86 S Ct 1236 (1966).)

7. To redistrict Marion CountY

alone would leave impermissible var-

iations between Marion County dis-

tricts and other districts in the

State. Statewide redistricting was

required, and it could not await the

19?0 census figures estimated to be

available within a Year.

8. It maY not be Possible for the

Indiana general assembly to comply

with the state constitutional re-

quirement prohibiting crossing or

U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

dividing counties for senatorial ap-

portionmentt{ and still meet the re-

quirements of the Equal Protection

Clause adumbrated in recent cases'u

9. Plaintiff Walker's claim as a

Negro voter resident of Lake County

thal he was discriminated against

because Lake CountY Negroes could

vote for onlY 16 assemblYmen while

Marion CountY Negroes could vote

for 23 was deemed untenable. In

his second caPacitY, as a general

voter in Lake County, Walker "prob-

ably has received less effective rep-

reslntation" than Marion CountY

voters because "he votes for fewer

legislators and, therefore, has fewer

Iegislators to sPeak for him," and,

since

1103 US 1371

in theorY voting Power in

multi-member districts does not

vary inverselY to the number of

voters, Marion CountY voters had

greater opportunity to cast 1i":

breaking or "critical" votes' But

the couit declined to hold that the

latter ground had been Proved, ab-

sent more evidence concerning Lake

County.ro In this respect considera-

tion of lValker's claim was limited

to that to be given the uniform dis-

tricting principle in reapportioning

the Indiana general assemblY'r7

districts and split into groups represent-

ing special interests.'--ir.-.c,.ti.t" 4, S 6' of the Indiana con-

stitution Provides:--;;.q. i""ito.ial or Representative district'

where more than one county shall con-

"tftrt" . ditt.i.t, shall be composed .of

.ontigooua-aounties; and no county' for

s-iiiTii;it apportio'nment, shall eoer be

d.ioided." (EmPhasis added')

15. See Part VII, infra.

is. ':t" iis second status, we find that

nlaintifr Walker is a voter of Indiana who

i".ia". outside Marion County' Applying

ih"

-r"ifot- district principle, discussed

infra in the remedy section, we find that he

orobablv has received less efrective rep'

resentaiion than Marion County voters'

it h"i, b""t shown that he votes for fewer

i"ri.t"to.. and, therefore, has fewer legis-

iriot" to speak for him. He also, theoret-

ically, casts fewer critical votes than

Itarion County voters, but we decline to

.o tofa in the absence of sufficient evidence

as to other factors such as bloc and party

uoting it Lake County. We hold that, in

the alsence of stronger evidence of dilu-

tion, his remedy is limited to the considera-

tion'which should be given to the uniform

district principle in any subse-quent -reap-

portionment of tte Indiana General As-

iembly." 305 F SuPP, at 1390.

17. The court found a failure of proof

on-blhalf of plaintiff Hotz, a resident of

ift" *ftit" suburban belt, and on behalf

of plaintiff Allan, an independent voter'

Two other plaintiffs were entitled to no re-

fi"f, pi.i"tif Chavis because he resided

"rt.ia-"

the Center Township ghetto and

plaintiff Ramsey because he failed to show

[fr"t fr" was a resident of that area' OnlV

p1"i"tiff BrYant, in addition to the

I I ] Turnir

the court I

llarion Cour

though reco

was directed

the court tho

evidence ind

State requi:

Judgment w

spects, horve

until October

lation

t

ren

districting i

found to exis

doing the cc

"might wish

certain prinr

portionment

in these proc

First, the co

cation that

ghetto were

number of

should be drr

color blind, a

mandering

tenanced. S

was advised

theoretical i

voters in n

that is, their

to cast more

legislative e

the testimc

multi-membe

proportionatr

single-membr

thought that

plication he

member of tl

sponsible to

elected the

County voter

qualified recog

found to have

entitled to the

18. See part'

lll 19. The

lowing this opi

judgment had I

tion had been

t

i

t I I Turning to the proper remedy,

the court found redistricting of

Marion County essential. Also, al-

though recognizing the comPlaint

was directed only to Marion CountY,

the court thought it must act on the

evidence indicating that the entire

State required reapportionment.ls

Judgment rvas withheld in all re-

spects, horvever, to give the State

until October 1, 1969, to enact legis-

lation

u03 us r38l

remedying the improper

districting and malapportionment

found to exist by the court.le In so

doing the court thought the State

"might lvish to give consideration to

certain principles of legislative ap-

portionment brought out at the trial

in these proceedings." Id., at 1391.

First, the court eschewed any indi-

cation that Negroes living in the

ghetto were entitled to any certain

number of legislators-districts

should be drawn with an eye that is

color blind, and sophisticated gerry-

mandering would not be coun-

tenanced. Second, the legislature

was advised to keep in mind the

theoretical advantage inhering in

voters in multi-member districts,

that is, their theoretical opportunity

to cast more deciding votes in any

Iegislative election. Referring to

the testimony that bloc-voting,

multi-member delegations have dis-

proportionately more power than

single-member districts, the court

thought that "the testimony has ap-

plication here." Also, "as each

member of the bloc delegation is re-

sponsible to the voter majority who

elected the whole, each Marion

County voter has a greater voice in

IVHITCO}IB v CHAVIS

103 US 124, 29 L Ed 2d 363, 91 S Ct 1858

373

the legislature, having more legis-

lators to speak for him than does a

comparable voter" in a single-mem-

ber district. Single-member dis-

tricts, the eourt thought, would

equalize voting power among the dis-

tricts as well as avoiding diluting

political or racial groups located in

multi-member districts. The court

therefore recommended that the

general assembly give consideration

to the uniform district principle in

making its apportionment.m

t{03 us 1391

On October 15, the court judicially

noticed that the Indiana general as-

sembly had not been called to re-

district and reapportion the State.

Following further hearings and ex-

amination of various plans submit-

ted by the parties, the court drafted

and adopted a plan based on the

1960 census figures. With respect

to Marion County, the court followed

plaintiffs' suggested scheme, which

was said to protect "the legally cog-

nizable racial minority group against

dilution of its voting strength."

307 F Supp 1362, 1365 (SD Ind

1969). Single-member districts

were employed throughout the State,

county lines were crossed where

necessary, judicial notice was taken

of the location of the nonwhite pop-

ulation in establishing district lines

in metropolitan areas of the State

and the court's plan expressly aimed

at giving "recognition to the cog-

nizable racial minority group whose

grievance lead [sic] to this litiga-

tion." Id., at 1366.

qualified recognition given Walker, was

found to have standing to sue and to be

entitled to the relief prayed for.

18. See part VII, infra.

I I | 19. The Governor appealed here fol-

lowing this opinion. Since at that time no

judgment had been entered and no injunc-

tion had been granted or denied, we do

not have jurisdiction of that appeal and

it is therefore dismissed. Gunn v Univer-

sity Committee, 399 US 383, 26 L Ed 2d

684,90 S Ct 2013 (1970).

20. The trial court's discussion of this

subject may be found in 305 F Supp, at

1391-1392.

374 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

tion abolishing multi-member dis-

tricts in Indiana, the issue of moot-

ness emerges. Neither PartY deems

the case mooted bY recent events.

Appellees, plaintiffs below, urge that

if the appeal is dismissed as moot

and the judgment of the District

Court is vacated, as is our Practice

in such cases, there lvould be no out-

standing judgment inr-alidating the

Marion County multi-member dis-

trict and that the new aPPortion-

ment legislation would be in conflict

rvith the state constitutional provi-

sion forbidding the division of

Marion County for the PurPose of

electing senators. If the new sena'

torial districts were invalidated in

the state courts in this resPect, it

is argued that the issue involved in

the present litigation would simply

reappear for decision.

t.r03 LIS l41l

The attorney

general for the State of Indiana, for

the appellant, taking a somewhat

different tack, urges that the issue

of the Marion CountY multi-member

district is not moot since the District

Court has retained jurisdiction to

pass on the legality of subsequent

apportionment statutes for the pur-

pose, among others, of determining

whether the alleged discrimination

against a cognizable minority group

has been remedied, an issue that

would not arise if the District Court

errecl in invalidating multi-member

districts in Indiana.

The court enjoined state officials

from conducting any elections under

the existing apportionment statutes

and ordered that the 1970 elections

be held in accordance with the Plan

prepared by the court. Jurisdiction

was retained to Pass uPon anY fu-

ture claims of unconstitutionality

with respect to anY future legis-

Iative apportionments adoPted bY

the State.2l

tr03 L:s lr0l

Appeal rvas taken following the

final judgment bY the three-judge

court, we noted Probable jurisdic-

tion, 397 US 984, 25 L Ed 2d 392' 90

s ct 1112, 1113, 1125 (1970), and

the State's motion for stay of judg-

ment was granted Pending our final

action on this case, 396 US 1055, 24

L Ed 2d 757,90 S ct 748 (1970)'

thus permitting the 1970 elections to

be held under the existing apportion-

ment statutes declared unconstitu-

tional by the District Court. On

June 1, 1971, we were advised bY the

parties that the Indiana Legislature

Lad passed, and the Governor had

signed, netv apportionment legisla-

tion soon to become effective for the

19?2 elections and that the new leg-

islation provides for single-member

house and s'bnate districts through-

out the State, including }farion

County.

II

With the 1970 elections long Past

and the appearance of new legisla-

t2l We agree

moot and that

before us must

not, however' Pi

of the Plan adol

Court, since tha

rvould have requ

of the 1970 cen

t3-61 The lin

v Sanders, 372

821, 83 S Ct 8(

nolds v Sims, 3

2d 506, 84 s

Kirkpatrick v I

22LF,d 2d 519'

and Wells v Ro'

22LEd 2d 535,

recognizes that

ernment is in

ment through I

representativet

each and ever

alienable right

particiPation I

esses of his S

ies." ReYnold

565, 12 L Ed 2

citizens find it

only as qualif

their rePresen

fective Partici

in state gover'

fore, that eacl

ly effective vt

members of

ture." Ibid.

schemes "whi

ber of rePre

numbers of <

at 563, 12L1

tutionally dil

votes in the

22. In Fortst

three-judge Dis

violation of the

that voters it

were allowed to

but that voters

were not. The

21. The court also Provided for the

possibility that the legislature would fail

to redistrict in time for the 1972 elections:

"The Indiana constitutional provision for

staggering the terms of senators, so that

one-half of the Senate terms expire every

two years, is entirely proper and valid

and would be mandatory in a legislatively

devised redistricting Plan.

"However, the plan adopted herein is

provisional in nature and probably will be

applicable for only the 1970 election and

the subsequent 2-year period. This is true

since the 19?0 census will have been com-

pleted in the interim, and the legislature

can very well redistrict itself prior to the

19?2 election. On the other hand, it is con-

ceivable that the legislature may fail to

redistrict before the 1972 elections. In

such event, all fifty senatorial seats shall

be up for election every two years until

such time as the legislature properly re-

districts itself. It will then properly be

the province of the legislature in redis-

tricting to determine which senatorial dis-

tricts shall elect senators to {-year terms

and which shall elect senators to 2-year

terms to reinstate the staggering of

terms." 307 F SuPP, at 136?.

V CHAVIS

2d 363. 91 s ct 1858

375WHITCO}IB

-103 us 124, 29 L Ed

t2l lVe agree that the ease is not

moot and that the central issues

;;f;;" us must be decided' lVe do

not, however. Pass uPon the details

,i ifr" plan adoPted bY the District

Court. iince that Plan in anY event

iuoufa have required revision in light

of the 1970 census flgures'

III ,

t3-61 The line of cases from GraY

v Sanders, 372 US 368, 9 L Ed 2d

821, 83 S Ct 801 (1963), and ReY-

noia. t Sims. 3?7 US 533, 12 L Ed

2d 506, 84 S Ct 1362 (1964), to

Kirkpairick v Preisler, 394 US 526'

iz r,'ea 2d 519,89 s ct 1225 (1969)'

ancl lVells v Rockefeller, 394 US 542'

22LEd,2d 535,89 S Ct 1234 (1969)'

recognizes that "representative gov-

ernment is in essence self-govern-

ment through the medium of elected

representatives of the PeoPle, and

each and everY citizen has an in-

alienable right to full and effective

participation in the political proc-

1..". o1 his State's legislative bod-

ies." Reynolds v Sims, 377 US, at

565,12 L Ed 2d at529. Since most

citizens fincl it possible to participate

only as qualified voters in electing

their representatives, " [fl ull and ef-

fective participation by all citizens

in state governrrlent requires, there-

fore. that each citizen have an equal-

ly effective voice in the election of

members of his state legisla-

ture." Ibid. Hence, aPPortionment

schemes "which give the same num-

ber of representatives to unequal

numbers of constituents," 377 US'

at 563, 12 L Ed 2d at 528, unconsti-

tutionally dilute the value of the

votes in the larger districts. And

hence the requirement that "the

seats in both houses of a bicameral

state legislature

t{03 us 1'r2l

must be appor-

tioned on a PoPulation basis'" 377

US, at 568, 12 L Ed 2d at 531'

t7-tol The question of the con-

stitutional validity of multi-member

districts has been Pressed in this

Court since the first of the modern

reapportionment cases. These ques-

tions have focused not on PoPula-

tion-based apportionment but on the

quality- of representation afforded by

the multi-member district as com-

pared rvith single-member districts'

in Lucas v Colorado General Assem-

bly, 377 US 713, 12 L Ed 2d 632,

si's ct 1459 (1964), decided with

Reynolcls v Sims, we noted certain

uniesirable features of the multi-

member district but expressly with-

held any intimation "that apportior-

ment schemes which Provide for the

atJarge election of a number of

legislators from a county, or any

political subdivision, are -constitu-

iionally defective." 377 US, at 731

n. 27, 12 L Ed 2d at 644. Subse-

quently, when the validitY of the

multi-member district, as such' was

squarely presented' we held that

such a clistrict is not per se illegal

under the Equal Protection Clause'

Fortson v DorseY, 3?9 US 433, 13

L Ed 2d 401, 85 S Ct 498 (1965);

Burns v Richardson, 384 US 73, 16

L Ed 2d 3?6, 86 S Ct 1286 (1966);

Kilgarlin v Hill, 386 US 120, l7 L

Ecl 2d 77r,87 S Ct 820 (1967)' See

also Burnette v Davis, 382 US 42'

15 L Ed 2d 35,86 s ct 181 (1965) ;

Harrison v Schaefer, 383 US 269,15

L Ed 2d ?50, 86 S Ct 929 (1966).!r

22. In Fortson, the Court reversed a

three-judge District Court rvhich found a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause in

that voters in single-member district,s

were allowed to "select their own s€nator"

but that voters in multi-member districts

were not. The statutory scheme in Fort-

son orovided for subdistricting within the

.nrniv, so that each subdistrict was the

.".ia#"e of exactly one senator' How-

ever- each senator rvas elected by the

."t"iv at large. The Court said, "Each

i."Utilttti.t'Jsenator must be a resident

of tfr"t [sub]district, but since his tenure

376 U. S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 29LEd2d

That voters in multi-member

t{03 us 1431

tricts vote for and ,r" ,.0".."n1LT

by more legislators than voters in

single-member districts has so far

not demonstrated an invidious dis-

crimination against the latter. But

we have deemed the validity of

multi-member district systems jus-

ticiable, recognizing also that they

may be subject to challenge where

the circumstances of a particular

case may "operate to minimize or

cancel out the voting strength of

racial or political elements of the

voting population." Fortson, 379

US, at 439, 13 L Ed 2d at 405, and

Burns, 384 US, at 88, 16 L Ed 2d at

388. Such a tendency, we have said,

is enhanced when the district is

large and elects a substantial pro-

portion of the seats in either house

of a bicameral legislature, if it is

multi-member for both

t1o3 us u4l

houses of

the legislature or if it lacks provision

for at-large candidates running from

particular geographical subdistricts,

as in Fortson. Burns, 384 US, at

88, 16 L Ed 2d at 388. But we have

insisted that the challenger carry

the burden of proving that multi-

member districts unconstitutionally

operate to dilute or cancel the voting

strength of racial or political ele-

ments. We have not yet sustained

such an attack.

IV

Plaintiffs level two quite distinct

challenges to the Marion County dis-

trict. The first charge is that any

multi-member district bestows on its

voters several unconstitutional ad-

vantages over voters in single-mem-

ber districts or smaller multi-mem-

ber districts. The other allegation

is that the Marion County district,

on the record of this case, illegally

minimizes and cancels out the voting

power of a cognizable racial minority

in Marion County. The District

Court sustained the latter claim and

considered the former sufficiently

persuasive to be a substantial factor

in prescribing uniform, single-mem-

ber districts as the basic scheme of

the court's own plan. See 307 F

Supp, at 1366.

Itll In asserting discrimination

against voters outside Marion

County, Plaintil

Fortson, Burns,

ceeded on the ar

dilution of votint

a r.oter who is

10 times the Po'

is cured by alloc

to the larger dis

one assigned to

PIaintiffs challer

at both the voter

They clemonstrr

that in theorY vt

vary inversely t

district and thal

tive seats in Pro

popLrlation gives

to the voter in

district since hr

to determine ele

t'103

does the voter i:

district. This ,

23. The mathem

theory is as follov

n voters, where e

between two alt,

there are 2n possil

For example, witl

voters, A, B, and

X and Y, there art

A

#t. x+2. x

#s. x

#4. X

#5. Y

#6. Y

#7. Y

#8. Y

The theory hYPc

test of voting pow

tie-breaking, or '

population of thre

any voter can cas

situations; in thr

the vote is not

change the outcot

exanrple, C can r

only in situation

number of com

voter can cast

2.-

n-1

0

depends upon the coutrty-wide electorate

he must be vigilant to serve the interests

of all the people in the county, and not

merely those of people in his home [sub]-

district; thus in fact he is the county's

and not merely the [sub]district's senator."

3?9 US, at 438, 13 L Ed 2d at 404. The

question of whether the scheme "oper-

ate[d] to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength of racial or political elements of

the voting population" was not presented.

In Burnette, we summarily affirmed a

three-judge District Court ruling, Mann v

Davis, 245 F Supp 241 (ED Va 1965),

which upheld a multi-member district

consisting of the city of Richmond,

Va., and suburban Henrico County over the

objections of both urban Negroes and sub-

urban whites. Since the urban Negroes

did not appeal here, the affirmance is of no

weight as to them, but as to the subur-

banites it represents an adherence to Fort-

son. Similarly, Ifarrison summarily af-

firmed a District Court reapportionment

plan, Schaefer v Thomson, 251 F Supp 450

(Wyo 1965), where multi-member districts

in Wyoming were held necessary to keep

county splitting at a minimum.

Burns vacated a three-judge court de-

cree which required single-member dis-

tricts except in extraordinary circum-

stances. The Court in Burns noted that

"the demonstration that a particular multi-

member scheme effects an invidious result

must appear from evidence in the record."

384 US, at 88, 16 L Ed 2d at 389.

In Kilgarlin, the Court affirmed, per

curiam, a district court ruling "insofar as

it held that appellants had not proved their

allegations that [the Texas House of Rep-

resentatives reapportionment plan] was a

racial or political gerrymander violating

the Fourteenth Amendment, that it uncon-

constitutionally deprived Negroes of their

franchise and that because of its utiliza-

tion of single-member, multi-member and

floterial districts it was an unconstitutional

'crazy quilt.'" 386 US, at 121, 17 L Ed 2d

at 774.

\YHITCO}IB

{03 us 12{, :9 L Ed

Countl-. piaintiffs recognize that

Fortson, Burns. and Kilgarlin Pro-

ceeded rtn the assttmption that the

dilution rrf voting power suffered by

a voter rvho is Placed in a district

1() times the population of another

is curetl by' allocating 10 legislators

to the larger district instead of the

one r-.signed to the smaller ciistrict'

Plaintifs challenge thig assumption

at both the voter and legislator level'

They clemonstrate mathematically

that in theory voting power does not

vary inverselY with the size of the

clislrict rrncl that to increase iegisla-

tive seats in proportion to increased

population gives undue voting power

to the voter in the multi-member

clistrict since he has more chances

to determine election outcomes than

t t03 L*S lr5l

cloes the voter in the single-member

district. This consequence obtains

v (IHAVIS

2d 363, 91 s ct 1858

377

rvhoily asicle from the quality or ef-

fectiveness of representation later

furnishecl by the successful candi-

clates. The District Cor-rrt did not

qr.rrrrrel with plaintiffs' mathematics,

nor do rve. But like the District

Court lve note that the position re-

mains a theoretical oner3 and, as

plaintiffs' rvitness conceded, know-

ingll'

t103 us 1n6I

avoicls and cloes "not take into

ilcconnt any political or other factors

rvhich might affect the actual voting

power of the residents, rvhich might

include party al'filiation, race, previ-

ous voting characteristics or any

other factors rvhich go into the en-

tire political voting situation."m

The real-life impact of multi-mem-

ber districts on individual voting

power has not been sufficientlY dem-

li

lr

li

23. The mathematical backbone of this

theory is as follows: In a population.of

n vo{e.s, rvhere each voter has a choice

between two alternatives (candidates),

there are 2n possible voting combinations.

For example, with a population of three

voters, -4,, B, and C, and two candidates,

X and Y, there are eight combinations:

ABC*r. x x x

*oyyY

#3.XYX

#4. x Y Y

i+5.Yxx

#6.YXY

,t7.YYX

#8.YYY

The theory hypothesizes that the true

test of voting power is the ability to cast a

tie-bleaking, or "critical" vote. In the

population of three voters as shown above,

any voter can cast a critical vote in four

situations; in the other four situations,

the vote is not critical since it cannot

change the outcome of the election. For

exanrple, C can cast a tie-breaking vote

only in situations 3, 1, 5, and 6. The

number of combinations in rvhich a

voter can cast a tie-breaking vote is

(n-1) !

o-

n-1 n-1

!

-r2

the number of voters. Dividing this re-

sult (critical votes) by !n (possible com-

binations), one arrives at that fraction

of possible combinations in which a voter

can cast a critical vote. This is the the-

ory's measure of voting power. In District

K with three voters, the fraction is j(, or

iO4. In District L with nine voters, the

fraction is 140/512, or 28'/c. Conven-

tional wisdom would give District K one

representative and District L three. But

under the theory, a voter in District L is

not 1 as powerful as the voter in District

K, but more than half as powerful. Dis-

trict L deserves only two representatives,

and by giving it three the State causes

voters therein to be overrepresented. For

a fuller explanation of this theory, see

Banzhaf, Multi-llember Electoral Districts

-Do They Violate the "One Man, One

Vote" Principle, ?5 Yale LJ 1309 (1966).

2.1. Tr. 39. Plaintiffs' brief in this Court

recognizes the issue: "The obvious ques-

tion which the foregoing presentation

gives rise to is that of whether the fact

[h:rt a voter in a large multi-nrember dis-

trict has a greater mathematical chance

to cast a crucial vote has any practical

significance." Brief of ^{ppellees (Plain-

tiff s ) 11.

378 U. S. SUPRE}IE

onstrated, at least on this record, to

warrant departure from prior cases.

The District Court was more im-

pressed with the other branch of the

claim that multi-member districts in-

herently discriminate against other

districts. This was ilie assertion

that whatever the individual voting

power of Marion County voters in

choosing legislators may be, they

nevertheless have more effectivL

representation in the Indiana gen_qral assembly for two

"uu.6nr.First, each voter is represented bv

more legislators and [herefore, in

theory at least, has more chances

to influence critical legislative votes.

Second, since multi-mlmber delega-

tions are elected at large and repie_

s_ent the voters of the entire district,

they tend to vote as a bloc, *frl.ii

is tantamount to the district'having

one representative with several

votes.85 The District Court did not

squarely

t103 US r47l

sustain this position,E butit appears to have found it sufficient-

ly persuasive to have suggested uni-

form districting to ttre t-niiana Les_islature and to have eliminaiJd

multi-member districts in the

"ou"i,own plan redistricting the State.

See 307 F Supp, at 1g6g_1g88.

tl2l We are not ready, however,to agree that multi-member ctis_

tricts, wherever they exist, over-

represent their voters as compared

with voters in single-membei dis_

tricts, even if the multi-member del_

egation tends to bloc voting. The

theory that plural representation it_self unduly enhances a district,s

power and the influence of its voters

COURT REPORTS 29 LEdzd

remains to be demonstrated in prac_

tice and in the day-to-day op""utio,

of the legislature. Neither ine nna_

ings of the trial court nor the record

before us sustains it, even *fr"""

bloc voting is posited.

. In fashioning relief, the three_

jyac" court appeared to embrace tL

idea that each member of a bloc-

voting delegation has more influence

than legislators from a single_mem_

ber district. But its findinis oif".i

fail to deal with the actuallnfluence

of Marion County's delegation in the

Indiana. Legislature. Nor did plain_

tiffs' evidence make such a showing.

That bloc voting tended to occur Is

sustained by the record, and clefend_

ants' own witness thought it was

advantageous for Marion County,s

delegation to stick together. Iiut

nothing demonstrates that senators

lnd representatives from Marion

County counted for more in the leg-

islature than members from singlE_

member districts or from ..uIl""

multi-member districts. Nor is

there anything in the court,s find_

ings indlcating that what misht bL

true of Marion County is also trueof other multi-member districts in

lndiana or is true of

t403 us 1481

multi-member

distr_icts generally. Moreover, Mar-

ion County would have no less ad-

vantage, if advantage there is, if it

elected from individual districts and

the elected representatives demon_

strated the same bloc-voting tend-

enc.y, which may also develop among

legislators representins single_mem-_ber districts widely scattered

throughout the State.iz Of .ou"r" t,

it is advantag

more than one

nothing before t

that any legisla

ing the State o

County in par

come out difft

County been s

delegation elect

ber districts.

Rather than

acceptable disr

out-state voters

County voters, 1

down Marion (

ber district be

scheme worked

a specific segrn

voters as com

The court idenl

city as a ghett

nantly inhabitr

with distinctivr

terests and t

unconstitutiona

because the pro

with residences

from 1960 to 19

ghetto's propor

tion, less than t

islators electec

Township, a ler

and less than th

have elected h

t{0t

sisted of singlt

We find major

approach.

tl3l Pi61, ;1

here that the

ments were des

civil rights of I

courts have be

portionment, t7

Legislation dealin

problems may be :

urban delegations

encounter insuperr

^25. 9,f. Banzhaf, Weighted

Doesn't Work: A Mathemitical

19 Rutgers L Rev g1? (1965).

. 2-q. I! is apparent that the District Court

declined to rule as a matter of law that

a multi-member district was per se iUeeai

as giving an invidious advantage to -riti_member district voters over voters in

single-member districts or smaller multi_

member districts. See 308 F Supp, at

1391-1392.

- 27. The so-called urban-rural division

has been much talked about. Ania;;"i.ti;

bloc .voting by_ the two camps may occurbut it_iras perhaps been overemphasized.

See White & Thomas, U.Uan .na nurat

ttepresentation and State Legislative .{p-

Voting

Analysis,

IVHITCO]IB v CHAVIS

103 us 12-1. 29 L Ed ld 3{i3, 91 S Ct 1858

it is :rdvantageotls to start with

more than one vote for a bill. But

nothing before tts shorvs or suggests

that any legislative skirmish affect-

ing the State of Indiana or Marion

Count-'* in particular would have

come out differentlY had Marion

Count-r- been subdistricted and its

delegation elected from singig-mem-

ber districts.

Rather than squarelY fincling un-

acceptable discrimination against

out-state voters in favor of llarion

County voters, the trial court strttck

dorvn ]Iarion County's multi-mem-

ber district because it found the

scheme worked invidiously trgainst

a specific segment of the cottnty"s

voters as compared rvith others.

The court identified an area of the

city as a ghetto, found it predomi-

nantly inhabited by poor Negroes

with distinctive substantive-law in-

terests and thought this group

unconstitutionally underrepresented

because the proportion of legislators

with residences in the ghetto elected

from 1960 to 1968 was less than the

ghetto's proportion of the popula-

tion, less than the proportion of leg-

islators elected from Washington

Township, a less populous district,

and less than the ghetto would likely

have elected had the

t103 us r49l

county con-

sisted of single-rnember districts.2s

We find major deficiencies in this

approach.

lt3l First, it needs no emphasis

here that the Civil War Amend-

ments were designed to protect the

civil rights of Negroes and that the

courts have been vigilant in scru-

tinizing schemes allegedly conceived

or operated as purposeful devices to

further racial discrimination. There

has been no hesitation in striking

down those contrivances that can

fairly be said to infringe on Four-

teenth Amendment rights. Sims v

Baggett, 247 F SupP 96 (MD Ala

1965) ; Smith v Paris, 257 F SUPP

901 (MD Ala 1966), aff'd, 386 Fzd

979 (CA5 1967) ; and see Gomillion

v Lightfoot, 364 US 339, 5 L Ed 2d

110, 81 S Ct 125 (1960). See also

Allen v State Board of Elections, B93

us 5.14, 22 L Ed 2d 1, 89 S Ct 817

(1969). But there is no suggestion

here that Marion CountY's multi-

member district. or similar districts

throughout the State, were conceived

or operated as purposeful devices to

further racial or economic discrim-

ination. As plaintiffs concede,

"there was no basis for asserting

that the legislative districts in

Indiana were designed to dilute the

vote of minorities." Brief of AP-

pellees (plaintiffs) 28-29. Accord-

ingly, the circumstances here lie out-

side the reach of decisions such as

Sims v Baggett, supra.

It4l Nor does the fact that the

nLlmber of ghetto residents who

r.l'ere legislators was not in propor-

tion to ghetto population satisfactor-

ily prove invidious discrimination

absent evidence and findings that

ghetto residents had less opportu-

nity than did other Marion County

resiclents to participate in the po-