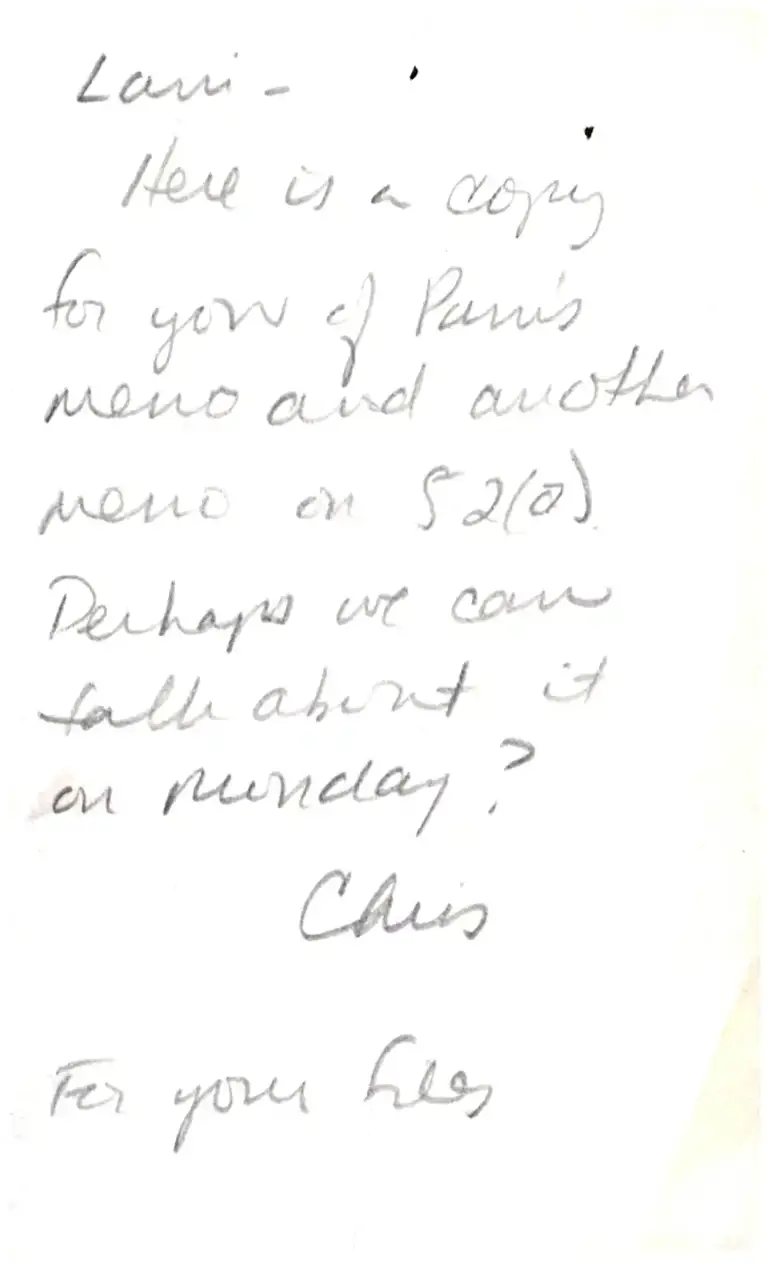

Attorney Notes; Legal Research on Rule 52(a)

Working File

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Attorney Notes; Legal Research on Rule 52(a), 1985. ae0ea1dc-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/08a6962c-3453-48e0-ab93-bbda5e8f8971/attorney-notes-legal-research-on-rule-52-a. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

/(p.ru' - '

,

/h^l Li .

[', Lt.'vv r) ffi

^rd^, ^-!a a't'c//-t^

ptQzttL c.'tt fsp\

D*lq* 4r( ctuu\)

4-tl a"l'">-/' ;l

. M /?/A4A/a7 ,'

f.a f* fu+

NIL D)

?arn Karlan

F.ul e 52 (a)

TI.

I. 'i.r:i LIl-STrl,liIC:1 L DE\JE|-()':t.;ili.|' (-:,.'' .,rrl "r-ll- -'''-:t'':f

Llrl.rl -

j ii(,\US " Sf .1ilDil.IiD riJ l: i;?,i ':-'' A (-i- i-' iT 1r'> i ;11 r- -iS

'.'iir'l '.()I-E OF Sii?REl'E tlC'URI] P'-"'rlllii lN 'i-I'"f

D I S CIir.': r.l'l-::',' I ON AI'ID C (]ii.'-iS S I (-N C'\ S F S

A. JURY SELECTION CASES. .

2

r.1

11

I5B. TI{E QUESTION OF VOLI'NTARTNESS

III. APPLICATIoN oF IIHE ,.CLEARLY ERRoNEoUS'' RULE:

THREE DISTINCTIONS AND THEIR RETIEVENCE TO

DISCRIMINATION CASES. .

A. SUBSIDIARY AND ULTII4ATE FACTS

B. MATTERS OF FACT,/MATT.ERS OF I.AW.

O +-Q' rr'r(t-

c. PAPER SAFFS/fr-jr-bTEss cREDrBrLrsY CASES

IV. RULE 52 (A) A}Ib SWIMT V. PULLMAN-STAITDARD

A. THE DISIRICT COURT AITD COURT OP APPEALS.

DECISTONS . t.

. B. THE BRIET iU OPPOSITION AND ITS CIAIT4S

OF LEGAL ERROR

C. MIE USW PETITION FOR CERTIORARI AND ITS

ARGU}4ENTS CONCER}IING RULE 52 (A)

t9

19

28

32

40

.4I

.50

.56

Before the adoption of Fed'R'civ'P' 52(a) ' the scope of an

appellate court's power to review a trial court's findings depended

on whether the case involved sounded in Iaw or in equity. The

Seventh Amendment's provision that'no fact tried by a jury sha1l be

otherwise reexamined in any Court of the United States than according

c to the rules of common Iaw" eras expanded over the years to include

even non-jury cases when they involved common 1aw issues, and the

. factual findings of a trier of fact Lrere held nearly inviolate.

Unless the error had been truly egregious, a finding of fact was

very rarely overturned. In equity c.?ses, appellate courts had a

relativeLy free h:nd in rcvi,:-'..ri;ig b,:t:h n,ltt::r.s r:f fact and natte(s

of Iaw. pul€ 52(a), rhich su-uq-:rscrjed f.af't the o.Ld larv and equity

star.larCs, -did r,ot even ;tlriress f indings of 1erv, in regard to r'hich

i

appellete courLs re:ail':erl free to,;verrul.e trial courts'Ceterminatictrs.

In regard to .f .l.ntiings of f act, it 1ea:le,l sr:mewhat tovrard the o1d

conmon-law s'ca;-.Card: "Findin,js of f;ct shal1 not be set asicie

unless clearly erroneous, and due regard sha11 be given to the

opportunity of the trial court Lo judge of the credibility of the

. witnesses.', Feri.R.Civ.P. 52(a) 28 U.S.C. What I hope to Co in this

memo is: (I) Tr:ace the developnent, in the Supreme Court, of the

,,c1earIy €rro.-r.:ous'r standard; (II) Examine Suprerne Court Cecisions

in two ccnstitutional areas (A) Jury Discrimination anC

(B) Confessi,)n cases -- to see what 1i9ht the Court's stanCarcs for

review in these natters night shed on Title VII litigation;

(III) Look at cases, both in the circuits and in the Suprene Court,

which focus on three distinctions critical to a Proper aPPlication

) of Lhe "c1ear1y erroneous" stanrjard: (A) The sulrsidiary f act,/u1ti:irate

fact distinction; (B) The matter of facl/matter of law distinction;

and- (C) The docuinentary case,/,,titness credi.bilitt case distinction;

2

and (IV) Given the case 1aw, analyze ies impact on Swint v. Pu1lman.,)

I. THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TIIE ''CLEARLY ERRONEOUS' STANDARD

IN SUPRET"IE COURT OPINIONS

fn Baumgartner v. United States, 322 U.S. 555 (1944), the Court

examined the bona fides of Baumgartner's oath aE the time he became

an .\mer ican citizen. f n its discussion of what sort of appellate

review was appropriate, the Court laid out many of ihe considerations

that have since become mainstays of Rule 52(a) inter9retation:

The phrase "finding of fact" may be a sunmary characterLzation

of c6nplicated facLors of varying significance for judgnent.

Such a "finding of fact" may be the ultimate judgnent on a inass

of ,.jetails inv6lvir,g not meiely an assessirr€ilt of the trr:r:t:',orthi'-

ness of witnesses, but other aElpropriate inferences that nay be

dra'*n from living test!.:licny which elude print,. The L-onclusi're:.:ess

of a "f i.nding of f act" de pinCs .ro the nature of [he :ar-er ials

on which the findiirg is based. The finding even of a so-(-'a11cd

"subsidiary fact" may be a tnore or less difficult Prccess

varying according to the simgliciey or subtlety of the tyPe of

"faLt" in coniroverSy. Fi;'ltiing so-ca11ed ultimate "faCtS"

more clearly implies the application of stanCards of 1aw. Aad

So the "finding. of fact" even if made by two Courts may 90

beyond the determination that should not be set aside,here.

Though Iabelled "finding of'fact," it rnay involve the very

blsii on which judEnenE of fa1lib1e eviCence i.s to be naCe.

Thus, the conclusion that may approPriately be drawn from the

whole mass of evidence is not, always the ascertainnent' of

the kind of "fact" that precludes consideratj.on by this Ccurt-

. particularly is this so where a Cecisicn here for review

cannot escape Urotaty social judgr,rents judg:iients ).yrng close

to opinion iegarding the whole nature of our Covernnent and the

duties and j.mmunities of citizenship. 322 U.S. at 570-I.

Several facets of the Court's opinion bear noting. First, the

Court distinguishes between findings of subsidiary fact i.e.,

docu:rentary or empirical findings -- and findings of ultimate fact,

which the Court analogizes to the application of 1egal standarCs; the

Court feels less obli-oated to defer to a lower court's f indings when

they involve the latter. Second, t.he Court states that the source

of a particular factual deternination may influence the deference

with which higher courEs view it. FinalIy, the Court a11ots itself

l

a wider scope of review in cases involving "broadly social judgmentsll"

this view of the Supreme Court as the only ProPer ultimate arbiter

of consitutional questions is borne out in its decisions in the

jury discr irnination and conf ession cases

the first major case in which the Supreme Court dealt specifically

with the requirements of 52 (a) was an antit.rust action,

United States v. UniEed Seates Gvosum Co. , 333 U. S.. 364 (L947) ,

where it defined both the scope of the Rule and !h. meaning of the

phrase "c1ear1y erroneous." ir'hen findi;rgs involve "inferenceS

drawn f rom docuinents or undisputed f acts, here'c,ofore Cescr ibed or

set out," Rule 52(a) applies. 333 U.S. at ?94. )!ore than sirnple

enpirical f indings are therefore incluC.-d rvithin 52 (a) 's SCoPe'

An appellate COurt Can reverse a Loi;u=r L-ourt'S f indings of f aCt

"when although tiiere is evide rce to Su?Port 'it, the revieiving court

is left with.the definite and firn conviction that a mistake has been

conmitted." Ibid., at 395. This definition of "c1early erroneous"

is firmly entrenched in the case 1aw.

In United States v. Ye1low Cab Co., 338 U.S. 338, 34L-2, (I9{9),

also an anLitrust c3se, the Court included within the sccpe of 52(a)

',findings as to the design, motive, and intent with which i:'ien:ct

Si."." tneyJ depend peculiarly upon the creCit given to wit;resses

by those who hear them. " ThiS statement, ;nakes cl.ear, ES some later

views seem to have forgotten,'.hat the maior reason why questions

of intent are often left to the determination of trial courts is the

influence which the demeanor of witnesses may have on findings

concerning the hidden feelings of Particular actors.

Three cases Cecided the following tern furLher clarified the

Court'S conception of the ProPer bounds of apPellate review. In

United St.ates v. National Association of Real Estate Boards, 339 U- S.

485 (1950), the Court elaborated on its statement in Yellow Cab:

"ft is not enough that we might give the facts another construction,

resolve the ambiguities differently, and find a more sinister cast

to actions which the District Court apparently deemed innocent. "

339 U.S. at 495. Thusr do appellate court could not pit its ourn

subjective feelings as to how a piece of evi.dence ought to be

interpreted against a trial court's subjective feeling; the lower

court's interpretation must be objectively mistaken Eo permit

appellate reversal. In Graver Tank and ir.fg. Co. v. Linde Air

Products Co. , 339 U. S. 605 (1950) , t,he Court extenCed this high Cegri:e

of deference to .l case in'*hich fin,Jings of ultinate fact involved

assessing iiiarty typ,:s of evidence and balancing tneir credibility

against one anoiher. in a Patents Case, "a finding of equivalence

is a determination of fa'ct. I'lhat constitutes equivalency

must be determined against the context of the patent, the prior art,

and the pedicular circumstances of the case. Equivalence, in the

patent law, is not i,he prisoner of a formula and is not an acsolute

to be considered in a vacuum." 339 U.S. at,509. That a finding

of equivalence is not "the prisoner of a formula" will beccrne an

important consideration in light of later cases whose results seemingly

contradict Graver Tank. This inportance of this factor was hinted

at in another patent case decided that term, Great Atlantic a Pacifi<:

Tea Co. v. Su-oermarket Equipment Co. , 340 U.S. L47 (1950). In A&P,

the Court saw itself as dealing with the applj.cation of particular

standards involving combination patents to undisputed facts, and

therefore as reviewing something which was nnore a matter of law than

a finding of fact. Graver Tank, therefore, did not app1y. 340 U.S

5

at 153-4. The Court seems to be distinguishing, then, between

the subjective judgments involved in inferring attitudes from facts

and the more "objective" type of judgment involved in applying

enunciated lega1 standards to the particular facts of a case.

united sEates v. oregon Medical society,'343 u'S' 32r (1951) '

reiterated the Court's commitment to the Yellow Cab-N.A.R.E.B.

"clearly erroneous" standard of review for questions of intent:

There is no case more aPProPriate fof adherence to this

rule than one in which the complaining party creates a

vast record of cumulative evidence aS to long-PaSt trans-

actions r litoiives, and purPoses, the ef fect of which

depenCs largely on credibility of witnesses- 313 U.S. at 332.

I{ere again, the Cour t's senti,rent seeins to rest on the assunptio.n

that a Large part of the value of Rule 52(a) is i,ied to the trial

court's advantage is assessing witiless creCibiliey.

?o the ACvisory Ccnmittee on Rule 52, l-,ouever, it Sr:€ir€d that'

lower courts were often applying the "clearly errcneouS" rule g.!.]f

in cases in which witness Cemeanor played a crucial roIe. In

1955, it reconnended changing Rule 52(a) to read: "Findings of faet

sha11 not be set aside unless clearly errcneous. fn the aPPlication

of this principle regard shal} be given to the special opportuniiy

of the trial court to judae of the credibility of t.hose witnesses who

appeared personally before it. " 5A Moore's FeCeral Practice 1152.01t71

at 2609 (1980). The effect of this amendment, would have been to

reinforce the applicability of Ehe "clearIy erroneous" standard to

all findings of factr ES the Committee's Note makes clear: "The amend-

ment is designed to end the confusion and show definitely that ihe

"clearly erroneous" test is not modified by lhe lang€a9e which for;ner1y

followed it, but is appl i.cable in a]I c.:ses. " Ibid. This ainend;aent,

however, was rejectedr So the perhaps ambiguous standard of the

original Rule-52(a) renains in effect.

Jn United States v. Parke, Davis & Co., 362 U.S. 29 (1950),

another antitrust action, the Supreme Court reversed the loygr courtrs

determination that the defendant's price maint&{ne{'tce policy hadn't

violated SI gf the Sherman Act. The iourt's opinion here applied

the analysis developed in the "application of 1egal standards" cases

(Baumgartner and AgP) :

The District Court gremised its ulEimate finding that Parke

Davis did not violate the Sherman Act on an errcneous inter-

pretation of the standard to be apglied. . tsecause of the

District Court's error we are reviewing a question of 1aw,

narnely whether the District Court applied the ProPer sta;rard

to essentia]1y undisputed facts. 362 U.S. at 14.

?his tack r.-arkcd a departure f rom the approach taken in sur:h r:arl ier

anti irust .jc,: j sions as U. S. Gy-g-I and Yellcw Cab, 'rhL:re the Court

ha,J al Lr:.r,,e,J 'r:r ia1 courts a gocd deal of g{titude in na<ing ccncius:.ons

from docui,'entary eviCe;ice es to inotive and intent.

The follcwing year, the Court continued its movemenE away from

52(a)'s restrictions on appellate rev iew in United States v.

yi:ers=-ppi Getlerating Co. , 364 LI.S. 520 (i961). This case involved

a conflict of interest on the part of a governnient employee in Lhe

negotj.ar-ion of a governnent contract. fn naking its iecislon,

ihe Court relied on docunentary firrdiags by the trial court. lione-

theless, "our reliance upon the findings of fact does not preclude

us f rom nak ing an independent Iny e:nphas isJ dei,ernination as to the

1ega1 conclusions. and inferences which should be drawn rrom them. "

364 U-S.'at 526. This case marks the nost expansive statement of

ihe Court's pouer of review. fn 1ight. of later statements, its

seems unlikely that the Court would stil1 define its Powers this

broad 1y.

united states v. Singer }tfg. co-, 374 u-s. L74 (L952) ' contains

the CourE,'s attempC to reconcile its somewhat contradictory Pronounce-

ments on the proper standard for appellate review of findings of

ultimate fact- rn footnote 9, 374 u's' at 194, the court stated

that " f nsof a1 as t,hat conclusion I that t,he manuf acturers' actions

manifested a common purposel derived from the court's aPPlication

of an improper standard to the facts, it may be corrected as a matter

of law. fnsofar as the conclusion is based on 'inferences drawn from

rlocuments or undisputed facts, . Rule 52(a) of the Rules of Civil

Procedure is aPPlicable."' In light of this distinction, a good

dea] of the Court's prior rulings can be understood.

On the one side, in Baungartner, A&P, and Parke Davis, the Court

sew the lower courts' act-ivieies as involving how certain f ac'.s o.:ght

to be interpreted, given a Cefinite 1e,;a1 standard. fn ihese cases,

there was a single correct lens ihro,igh rhich the particular facts

ouEht to be vierved; it was relatively si:i..ple for an appellate court

to determine -if it had done so. Cn the other s i'Je, in Graver fank '

N.A:R.E.B., and Oregon lledica1 Society, the lower courts' PersFectives

on the facts did not have to conform to a single predetermined 1ega1

sian6ard. ft was therefore not as easy for an appellate court to

determine errori as a result, it should be iTiore hesitant to do so.

This difference, ds we sha11 see in Section IfI, may be particularll

iinportant in a Title VII case: to the extent that a deternination

of discrimination rests on the application of certain standards to

the peculiar facts of the caser Bn appellate court becomes freer

to set aside that lower court finding; to the extent that a finding

a discrimination rests more on the judge's subjective inference from

those factsr do appellate court should be loathe to disturb it.

In. !lnj-tsd--F.!C!ej"-g.---General Motors. 384 U-S- L27, L4L-2, (1965) ,

the Suprene Court held thaE the lower court had erred "in its failurer

to apply the correct and establisnea standard for ascertaining the

Act. " In a footnote, the Court fleshed out its views:

we note that that ultimate conclusion by the trial

judge. . is not to be shielded by the "clearly erroneous"

test embodied in Rule 52 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. . The question hire is not one of "factr'

but consists rat,her of the legal standard required to be

applied to the undisputed facts of the case. . Moreover,

the trial court's customary oPPortunity to evaluate the

demeanor and thus the credibility of the witnesses, which

is the rationale behind Rule 52(a) , . plays only a

restricted role here. This was essentially a "paper" CaSe.

384 U.S. at L42, fn. 16.

The Court's belief here seems to be that Rule 52(a)

I

existence of a combination or

whi1e the appellai.e c,)urt has

In ceses where the trial and

identical evidence, the appel

conspiracy under 51 of the Sherman

restrict appellate review cnly in those nat'uers in

court pcssessed unique advantaEes. Ultinatelyr. all

can be traced i',aek t-o o;:e factor: the trial court

was meant t.o

which a Erial

ihese aCvantages

sees 1i're uitnesses

overruling the lower court if it believes that a mistake has been

made.

Zenith Radio CorP. v. Hazeltine Pesearch, fnc-, 395 U.S. 100,

(I969), a patents case, retreated scneivhat from ihe liberal review

standarCs enunciated in G.M. Tnis case involved the correr:iness

of certain inferences drawn by the trial judge regarding the

damages Zenith had sustained as a result of a conspiracy in restraint

of trade. After restatirlg its commitment to the Gypsum standard

(see p. 3), the Court wenE on to state that "Trial and appellate

courts alike must also observe ihe practical limits

of proof. The Court has rePeatedly held thaE

of more precise proof, the factfinder may 'conclude as a matter of

at L23, that a prcscribedjust and

activity

reasonable inference," 395 U.S

has damaged the plaintiff. In some ways, this statenent

seens to be the flip side of the Court's belief in 3aumgeltne! that

"the conclusiveness of a 'finding of fact' depends on the nature 4i

onLy a transcc ipt in f ront- of it.

appellate courts are Eir.:senLed vrieh

laie court shculd noE be hcsitant in

of the burden

in the absence

9

of the materials on which the finding is based," 322 U.S. at 670-L,

and suggests again the Singer distinction -- when a trial court

judge's determination is, by its very nature, discretionary, appellaLe

courts oughE to respect that, discretion, while when a judge's

determination ought to fo11ow some well-defined 9ath, the appellate

court is free to drag him back should he stray.

rn Kelley v. Southern Pacif iq ta_., 4!9 u.s. 318 (1974) , an

enrpioyee injury compensation case, the court, citing singer,

reiierated ir-s ccnviction that appellate review of trial ccurts'

ii-,proper appl ications of 1ega1 staniards '.Ias noi at. all limi ted by

52 (a) :

I.ie need not reach the questicn whether any of ti:e Drstrict

Court's findings in this case were clearly erroneous, since

we agree with the court of P.ppeals that the trial court

applied an erroneous 1e9al stanCard in hcJ.ding ihat the

piiintif f r,,as within the (€E,--h of Lhe rELA. 119 U. S. at 323

ihe Supreme Qourt then wenE on to discuss ihe'vrays in which the

plaintiff could have shown that, rS a natier "of cc=,mon-1aw princiPles,

i':e was an employee. Ibid. at 323-4. Thus, the Court showed its

*i11ing;ress in J.ega1 staniarCs caseS to exanine caref u11y the

actual Cata in the trial record io deternine if the standaris had

been correctly aPPlied.

Davton tsoard of Education v. Brinknan, 443 U.S. 526 (L979),

was the first case I found in which the Court discussed the aPPlicat:on

of the ":1"arIy errcneous" rule in the ccntext of a civil right's

case. In a footnote, the Court stated that "',ie have no guarrel with

our Brother S.tewart's general conclusion that t.here is great value

in appellate courts showi.ng Ceference to the factfinCing of l-ocal

trial judges. The clearly erroneous starCard serves that Purpo:ie

we11. But under that staniard the Court of Appeals performeci

its unavoiCable duEy in this case a,'ta concluded that the Distr ict

10

Court had erred." 443 U.S. at 534t fn. 8. fn the text itself,

however, the Court characterized the District Court's error as

-having "ignored the 1egal significance"'of the empirical fact that

Dayton's school system had been segregated at the time of Brown I.

443 U.S. at 535-6. bnder the Court's Previous analysis, such a

mistaken application of a 1egal stanCard need not be clearly

erroneous to be overruled.

The mcst recent case having a potential i,rpact on the scoPe of

Rule 52 (a) is Burdine v. Texas. Departrnent of Conrnunity Af fairs,

49 U.S.L.W- 42L4 (1981). There, the Court declined to. decide whether

the Fifth 6i6sr:it had erred in declining to abide by the "clearly

erronecus" standard in its review of the District Court's finding

of no .J iscr inination bacause "the Court of Lppeals appl ied the v;rcng

Lggal_siandard to the evidence. [ny einphasis]" 49 U.S.L.'/i. at 42L7,

fn. L2. This suggestion that, the i'lcDonne]1 Douglas three-step

process for showing a violation of S703 [1..r-gDon.ngll Douqlas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 802-4 (1973)1, is a 1ega1 standard which

must be folLowed in each Tit,1e VII case could nean that intenticnal

discrinin.:tion ought to be viewed in the persPective set out in the

Baungarr-ner-?arke Davis-Dairton ]ine of cases, where the more restr ic-

tive stanCard of review rnandated by 52(a) is inapplicable.

Overafl, then, the development of Rule 52(a) in Supreme Court

cases suggests that the Court takes a restrictive view of aPpellate

review primarily in cases where it believes that Ehe lower courts,

through their actual contact with witnesses hold a significant advantage

in balancing different forns of evidence in making findings of ultinate

fact. fn areas in which controversies over the actual facts are

absent, the Court views appellate courts as equally capable of applying

the correct 1egal standards and therefore as not being as strictly

bound by prior lower court determinations.

t.,

..'...'

-f':'' j

rr"

ffi"XSH.$t#ff* couRr REvrEw rN rrrRy DrscR&*!{ArroN

AND, -'t

)

1 ; This.vierr is particularly atrong in eases j.nvolviag what the

ffi;ff:;T:i,:;:"';; ,iljl -: judsrnen,s lyins

nature of or:r eov""rr.ent and theduties and i.rmuniti oo at -r L! ;;=,:.:;;:"T:::.iwas further disti.lled in codisnerr-i

v'e' qL o

constirutional rights turn on the resorr;;;

liroc.€dangsr ,,when

i:T::,'.':::'J"the record." 4Ig U.S. 506, 517 5Ir. 6 (LgZ4).' lhis responsibi*ly to scn:tinize'carefurly

any state action whicb,might deprive citizens of their federal constitutionar rights wasreiterahd in .fackson v. virqinia , 443 [r.s. 3oZ ,.gzg), a caseconcern-ing the sufficj.ency of evidence" \

rard - -r^-----:,-'

er evtdence and the "beyond a reasonablei-ubt" standard, where- Ehe court wrote that ,.A federal court has a dutyto assess the historic f,acts when it is ealled upon to apply aconstitirtional standard to a conviction obtaiaed i-n a state court.,.443 L'S' at 31g- This approach is compa!.i.!!g, of course, witb theone laid out ia the "leg'al standards,, cases exarurned in section r.''ro 35g3t in which the phil0sophy of supreme court review is particularlyuell-deveroped are Possibre raciar dj.scrimination ia grand jury serectionrnd the dete:=nination of vorr:'tariness iu confessions.

A. JTIRY SELECTTON CESES

For over 9o years, it n::_begn establish_ed that a criminal

convinctic

c1;;;;-;;"to3="3,I:3::. :"anc r =

t"ii"

dictment o

-reasonor'f .:.i;;;1ili'Hff1-i;1"1Tria'+i"5,i$*-9".'=":;""i""iJi"L', ?3i=u:r":i#l?jaiffi;l'*;..i;;i. "fu .

-rTury cases involve violation of a consti.tutional provision, theurteenEh Amendment, and not of a statute, such as Tit1e VII. This

j

...{'t

rl.|

:::rJ

'14 /

tAls the Court recognieed in Arlington Heights, " ls]ometimes

' i clear pattern, unexplainable on grounds other than race,

energes frcmr the effect of the state action even when the

'goveining legislation appears neutral on its f,ace. . . Id.,

at 255."

washincton'i'. Davis

appropriate in jury

430 Ir.S. at 4932

itself recogni;zed this standard of sc:nrtiny aa

cases, the Castaneda eourt went on to point out,

It is also clear [the Washinqton v. Davis Cor:rt wrote] from

ttre cases

-aeiring'witaffiion in the selection

of juries that thd systematic exclusion of Negrges-is i$!!.- [my-emphasisJ such an'rrnequal application of the law . . . as

I to-show intentional discrimination." 426 u.s. at 241.

Fi.nal]y, in Rose v. Mitchell , 443 U.S. 549 (1979) , the Court reaffirmed

its obligation to'exanine-possible defects in a grand jury's composition"

even irr light of Stor-re v. Powell , 428 g.S.

?rU (1976), which had held-

that a federal habeas corpus clain could not be invoked by state

prisoners who bad been afforded the opportr:nity for full and fair

consideration in state court of their clai^ms re1aLi-ng to the adnrission

of illegal.ly sei.zeid evidence at their trial.s. taking into accorrnt both

this decision and,fustice ilackson's dissent in Cassell v. Tecas, 339 Ir.S.

2A2 (1950), another jur'y discri-mination case in whj.ch a conviction had

been over;urned because of biased grand jury selection procedutes,

.Tustice Stenart, argrreil that conviction by a properly constituted petit

jury eonvinced of the defendant's guiJ.t "beyond a reasonable doubt"

cured any taint in the grand jur:r selection procedure and therefore,

that neither on dj.rect appeal nor on collateral review, should a con-

viction be set aside. The Court rejected this argument rrnequivocally:

This Court, of course, consistently has rejected this.argument.

rt has done so implicit'Iy. . . . faJnd it has done so expressly'

. . . We decli-ne not to depart from this longstanding consistent

practice, and we adhere to the Cor:rtts previous decisions.

443 Ir.S. at 554. .

-:. The Cor:rt, then, has continued its conrnilment to providing the

fullest Srcssible review in constitutional rights deprivations cases

involving discrirninatory practies even after it significantly lirnited

{l

t5

acces6 in other criminal constitulionAl rights malters. this decision

,

E eem!, to spring from ttro f,actorg which may also aff ect its views ir^

. regard to Title r/II litigation. First, tlre pre6'bnce or absence of

'.discrj:uinatioa ia an iesue of, ulti.nate fact, dependent on judgrment :

and the applicag:ion of analytlcal standards to ttre raw materj.al peculiar

to the case; appellate courts a:ie as qualified as lower courts to

make anaLltic decisions which approach the status of questions of Iaw.

Second, discri:ruinatoly jr:ry selection Procedures, unlike, SBte the

admission of iIIegaIIy seized evidence at a trial, have a social

irnpact far in excess of theii irupact on the individual. The Supreure

Court has recognized this since its seminal decisioa in Strauder v.

West'Vircjnia, 1OO U.S. 303 (1881) . there, it pointed out that in '

addi.tion .to denying equal Brotection to blacks tried before juries

frqn which their Peers had been excluded:

lhe very fact that colored peopte afe singled out and expressly.

denied iy " statute al], rigirt -to

EarliciPat? in ttre adrninistration

of 'the.i"w, as jurors, beeause oi their color, thgugh they are

citizens "rri r"y-be in other respects fully quaLj.fied, is practically

a brand upoD, tb-en, aff,i:<ed by thE law; an assertion of their

inferioriiy, and a stimulanCto that race prejudice.which is 2.'

ir,p"ai.-"n{ to securi-ng to indivlduals of the race that equal

jiGti"" which tJre law-ai^ms to secr:re to aI1 others.'100 U-S. at 3-.

Tbe same analysis holds in Title \III cases. If minorities are barred

from certaia Srcsitions, either outright or through the'workings of

intentionally dj,scrj.:ninatory testing or Promotional systems, their

ensuing economically disadvantaged condition will place a badge of

inferioiity on them and harmfuJ' stereotlpes about their lack of

ability wiJ.l be PerPetuated.

B. TEE QUESTION 0E' VOLUITARINESS

The fifth Ameadment provides that no Person "shall be compelled in

any criminal case to be a witness against hirnself." Through the

Fourteenth Amendment, ttris prohiJ:ition has been held applicable to

stateProsecutionsasweI1.@,.378U.S.1,6(t964).

t5

Since thLs ie a federal right,, the Court went or. P adlY, it should be

judggd by the etandards developed ia federal cases. -I!.&, at 10.

Evea prior to the wholesale incorporation <i,f ttre EelE-incrimlnation

clause, the'supreme Court had held, in Brown v. liississippi, 297 U-S.

278 (1936), Elrat tbe use of coerced confessions fr:ndaraentally

violated due process and was thus prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment.

-@., aL 287. The question whj.ch the Court addressed in ttrese cases

which is of the most interest to us is: what shouLd be the role of the

Supreme Cou:t in dete::ruinifig the voluntariness of a confession?

Payne v. Arkansas, 355 Ir.S. 550 (1958), involved the murder

conviction of a l9-year-o1d r:nedtrcated black man who was held incomrnunicado

rrltjl his confession. After confinring that use of a confession obtained

by either physical or rnental coercion violated the Fourteenth Amendruent,

the Court continued:

Enforcement of the criminal laws of the States rests principally

witS tlre state corrrts, and generally their findings of fact.,

falrly nade upon substaintiil and conflicting-testirnony as to

the circr:mstances producing the contested confessioa . - . are

not this Court's c6ncern; let when the clai-m is that the-prisone-r's

eonfession is the product of, coercion we are bor:nd to make our

eqfil e:(--inaLion of- the record to dete::mine whettrer t-he claj-u is

meritorious. . . . That question can be answered only by_reviewing

the cricr:mstances under wfrictr the confession was made. 356 U.S-

at 561-2.

The scope of rerriew the Supreme Court allows itself here is even more

extensive than that which it ca:rred out i.n jury cases, since here it,

will make an independent judgment even in cases involving conflicting

evidence aad live testimony -- factors whieh the Cor:rt usually had

for:1d to give the trial cor:rt a decided advantage in dete:=ain-ing the

issue involved. Cf Graver Tank, -SEg at 4, where tbe existence of

confU.cting evidence was taken as a jusUlfication for appellate

deference. Again, it seeus that the Corrrt's feeling ttrat it should'

ultimate arbiter of, constitutional rights overrides its sense

deference that ought to be Paid to the'advantages held by

courts in assessing credibility.

be the

of the

trial

. ..17

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U.S. 199 (1950) made clear the resolution,

/^, the Suprene Court had nade between this cirnpeting clai-us. Af ter

. ataeing that it had "accord[edJ all of the deferEnce to the trlal

- t' a

' judge'e decision. which is corapatible with our duty to ,deteranine

constitutional queslionsr" 351 Ir.S- at 2O5, the Court reminded its

readers tlrat 'we cannot escaBe Ehe responsibility of scnrtinizing the

record ourselveg.' I-l:id., fa. 5.

Brookhart v. Janie, 384 g.S. 1, 4, fn.4 (1966), expressed the

view that voluntariness was a matter or law or ultimate fact suitable

for r:nhampered appellate review: "When Constitutional rights tu:ra oa

the resolution of a factual dispute we ate duty bound to make aa

indep€ndent oramlnaEioa of the evidbnce in the record. r'

'

Davis v. North Carolina,.384 U.S. 737 (1965), was decided after the

Conrtrs landmark deej.sion in ld.randa v. Arizona, 38,4 U.S. 436 (L956).

The Court made clear tha! its process of revier was not in any way

limited by the decision in ttiranda, but rather that Miranda provided

a usefu1 tool ia assessirg votuntariness. 384 U.S. at 740. The

Court once again for:nd that its duty reguired it "to examine the entire

record and to make an independent dete:::n-ination of, ttre .g!!s{!g, issue

of volr:atariness [uy emphasis]." &!]*, at 741-2. This view was confi:med

ia1aterdecision,e.9.,,397U.s.564,565(t97o},.

Beclapith v. gnited States, 421 Ir.S. 34L. 348 (1976).

Two relatively recent cases have aruplified the Courtr s 5rcsition.

1g Drope v. l.tissouri, 42O U.S. 162, the State had argrred that the

Supreme Court owed a good deaL of deference to the findings of, tbe Missor:ri

Supreme Court. After replying tJrat it "share[d] resgrcndent's concern

for tlris neces53ry balancer" 420 U.S. aE !74, the Court went on to

say ttrat this case involved making inferences from established f,acts

and that it was "incumbent on us to analyze the facts in order that the

.-: I

18

appropriate right, nay b9

.i

.59O (1935)." 42O V.S. at

it,s view of the

strongly:

lawyer

Arizona

wai''ell

aSEUted. Narri q v A't alrarna - 294 U .S . 587 , ,

L75. In a footnote, the Cor:rt stressed

nature of a f,lnding of volrurtariiesE even more

But 'igsuee of factn is a coats of many colorg.' Xt doee not'

cover a conclusion drawn from r:ncontroverted happenings:.wh?l

that conclusion incorporaEes standards of conduct or crit'erta

ior juagnent whicb "ri in themselves decisive of constitutional

righls. Such slandards and criteria, measured against ttre.

r"fui""r.rrt= drawn frcm eonstitutional.provisi?ns, and their

proper "ppii.ilions,

ale issues for thi; court's adjudication.

. . . n=il"ially ia cases aris_ing r:nder the Due Process Clause

it i" lnfortanf m disinguish_betr+een issues of fact that are

here to"I"iJ.ea ana issu6s which, tlrough cast i.n the form of

determinations of fact, ale ene veri ilsues to review which this

court sits. watts v. indiana 338 a.S. 49, 51, (1949) (opinion

of Srankfurter, a-) ;Jl:Lc!=-, fn' 10'

The most recent case involving voltrnEariness was decided this

te:in, Edwards v. Arizona, 49 U.S.IJ.W. 4496 (1981). In the majority

opinion, the Court overturned Edwardsr conviction since, although he' had

requested a lawyer, detectives interrogated hirn again before the

had arri-ved. The Cor:rtt s rationale -- that " . . . [tJ ne

Supreme Cogrt applied an erroneoust standard for deter:a:tniag

when gre accused has specif,ical.ly invoked his right to couns€I,'

49.U.S.t.If. aE 449'7 -

f,alls sguarely within thei.r Eraditional

approacb- iluetice PowelJ.'s concurrence, in which Justice Rehnqu5-st

joined, however, argued thaE, the "re1evant inquiry -- whether the suspect

desires to talk to ;rcIice without counset -- is a question of fact

[my enphasis] to be determi.::ed i-n light of alJ. the circrtrnstances."

Ibid. at 450O. Whi].e at first this n-ight seaE a dangerous departure

frcm earlier views on the nature of tb,e f,j.ndings involved in volrrntariness

cases, the tone Of the concurrence as a whOle is somewhat less

radical. .Justice Powell is objecting to making the

of who "initiated" a conversation between !rclice and

dislrcsitive of the entire constiEutional question of

Ee still seess J-oyal to the corrrtts general approach

factual dete:mination

the suspect

voluntariness.

of loohing

19

at, "vatious facts that may be relevants to dete:mining whether t'here

has been a valid waiver, " &i& aE, 4500, independent'ly' and applying

a constitutional Etandard in making the final detse::minatj'on' such

a does noE nec 'est' that ene iuprene Corrrta persPective does noE necessarily sugg

itself play a less aetive role in reviewi-ng eases of this sort'

WiEh this general overview of, tbe Supreme Court's Srcsition as

background, I wiII not discuss Srcssible applicat'ions of these

f,omulations of the role of appellate review to discriraination cases -

Because the supreme court itself lras not sPoken very clearly as

to the role of appellate review in ttrese matters, most of my

examination will be based on casles decided by the various courts of

Appeals

III. APPLICATION OF TIEE "CLEARLY ERROIIEOUS" RULE:

AIID TIIEIR RELETWA}TCE TO DISCRIIIINATION CASES

TI{REE DISTINCTIONS

When asked during his testimony at the Chicago 7 trial to stick

totlrefacts,Nornant'tailerretorted.'Factsarenothingwithoutt}reir

nuances, sir." Three nuancec which the courts have divined in the

phrase ,.findings of fact" have substantially loosened the strictures

placed on appellate rerriemr. by Rule 52(a)'s "clearly erroneous" requirement'

A. SI'BSIDIARY FACTS AND TILTIIIATE FACTS

Ever since Baumgartner, supra, courts have recognized a difference

between issues of subsidiary fact and issues of ultj:nate fact' A

finding of subsidiary fact involves specific, quasi-ernpirical, details'

AIso, in tight of the decisions in Gvpsum' Yello!9 cab' @L'

and zenith, it seelos that "freestyle" inferences from basic facts

are subsidiary; that is, cbnclusions not dependent on a particular

and well-defined legal standard, deductions which could be made by

a layman, are findings of fact ,xithin the meaning of 52 (a) ' In the

language of the Baumsartner opinion, a finding of ultimate fact,

'20

more elearly iruplies the application of standards of law'

rfrougfi-fabeilea- ;iitairrg oi- fact, " it may involve the very basis

/-., on'rf,icn judgnent of taitifte evidence is to be made- Thus the

.conelusion that may appropriately be drawn from the whole mass

of evidence is not'aliiys-the aslertainment'of the kind of

;f""t;-tfrit pr."foa"" .Sn"ideration by this .Court.' 322 U.s. at 571

.

over the years, appellate eourts have struggled with the application

of what often seems to be a hzay guideline as to how to distinguish

between lower courtst inferences, which ate subject to Rule 52(a)"

protection, and tlreir findings of ultimate fact, which are not'

Sseuenot v. Norbirq,zLO t.zd 615 (9th Cir., 1954), involued a District

coult order that certain employees be rehired.by the court-appointed

trustee in a Chapter X reorganization proceeding. In explaining its

decision to overrule the Oistrict Court, the Court of Appeals €x-

plained that:

When a finding is essentially one dealing with the effect of

certain transactions or euents, rather than a finding which resolues

disputed facts, 3D appellate court is not bound by the rule

I ttrai tinaings shall not Ue set aside unless clearly erroneous

but-i;;;."-i" dt"t, its ohrn conclusions. 2lO F.2d at 619

At f,irst glance, the Ninth Circuit's Position seems at odds with the

stance taken by the Supreme Court in Gypsum, Yellow Cib, and Graver

Tank.Eerehowever,theCourtofappealssawthisDistrictCourt's

findings of the effect of rehj.ring the fired ernployees as being

connected to its assumption that the discharges were "in direct violation

of the subsisting contractual rights of the appellees'" Ibid' What

these contractual rights are, the boundaries of a court's Power to

order specific performance, and the ProPer supervisory role of a

District Court in Chapter X proceedings, are all legal questions'

Thus, the inferences drawn by the lower eourt did not depend so1ely

on the basi facts; they also involved the application of legal standards

. and therefore were not, protected by the "clearly erroneous" test.

Much the same position was taken by ttre Third Circuit in Sears,

Roebuck and Co. v. Johnson, 2!g F.2d 59O (1954) . Johnson had'set up

the ,,AII-State School of Driving.." Sears, which had spent millions of

2T

,1

(

t'ollars promoting its "Allstate" brands of automobile accessories and

automobile insurance, sue , claiming that it was being damaged by the

"confusing similarity" of the two names. Citing'a previous case'

o-Tios. Inc. v. Johnson alqd-EohrlE-on, 2OG F.2d L44 (3d Cir', 1953) ' cert'

denied, 346 u.s. 867 (1953), the Court explained that the evidence

used to prove ,'confusinf similarity" was protected by 52(a), but

that the conclusion itself, was not:

Rule 52 (a) is not applicable where, 3s here, the dispute is

not as to'tft. basic lacts, but as to what inference (i'e'

ultirnate tacit should reasonably be derived from the basic

facts. Thi; court, by exami.ning tfre basic facts found by

the district court, can determine, ES aduantageously -as-!!e

di.strict ""t=t-".t,

whether or not an inference of likelihood

of eonfusion is warranted. 219 F'2d at 591'

The court,s equation of inference and ultimate fact here is somewhat

ruisguided in light of the supreme court's attempts to differentiate

the two. This case can be reconciled with the mainstream, hor'ever,

since the shird ci-rcuit seems to view likelihood of confusion as

involving not merely inferences drawn from the case at hand' but also

the application of an evolving legal standard developed through the

prior case law. The Court gives credence to this interpretation

when it cites the Restatement, Second, oE Torts, ES setting forth

"the generally accepted factors to be considered in determining

whether a particular designation is confusingly similar t'o another's

trade t1ame." 219 F.2d at 592. The weight given the four factors

Iisted in the Bestatement removes the findings in this case from the

class of freestyle inferences lo which the "clearly erroneous"

standard applies, and places them in the category of "application

of leagl standards,', which are accorded 'a m:ch freer review. Thus,

the ,'inferences,,to which the Third circuit refers ought really to

be prefaced with "Iegi'al."

Galena Oaks Corp. v. Scofield, 218 E.2d 217 (Sth Cj'r" 1954) is

the seminal case underlying the Fifth circuit's distinction between

s:hsidia'rv and ultimate facts. In Ga1ena Oaka, the Ccurt addressed

22

the

I

qlestion of the PurPose for which the plaintif,f had held certain

that

Lobello v.

property. In an earlier ca.se, the Fifth Cilcuit had declared

ultirirate facts fell under the "clearly erroneousl' standard'

Dunlap, 210 F.2d 465, 468 (1954). In Galena oaks, hotrever,.

as the so-called "ultimate fact" is simple !h. result recched

by procei"-oi legal reasoning f,rom, or the interpretation of

iire-legai-"igrrificanee of,, tf,e evidentiary f,acts, it ic

';"rrlj.it to ieview free of the restraining impact of the

so<alIed

-iciearly erroneous' rule. " LehmaBr] v: iFltqson'

206 F.2d, sgi: 5g4 (3d Cir-, 1953). 218 s'2d at 2L9'

Recent cases have continued to uiew less deferential treatment

of loger courts' findings of ultimate fact as appropriate' In

University EilLs, Ine. v. Patton, 427 F.2d LO94, 1099 (1970) ' the

Sixth Circr.rit exPlained that

Although findings of fact adopted by a-District court are

Uitait6 ot-.t, aipellate court unlesl clearly erroneous' Fed'R'

Civ.p. 52(a), ii:Lerpretation of written conlracts, conclusions

of law, ;il;a questions of fact and law, and findings as

an ultim"t"-i"Et, adoPted by the court, are not subject to lho

rule and are within the comletence of an appellate court' -,Cordovan

essociates, lrlg, v- PavIoB iulEer.9o' , -2?9

F'2d-858' 859-60

(6rh cir

dtat.t, 4LS E'.2d (6th cir., 1970)

The group of determinations ttre sith circuit exempts from the "clearly

elroneous" fule ate all areas in which the lower eourts Possess nO

advantage in interpretation. This theme runs throughout both the

supreme court and the courts of Appeals' discussions of tEe applicability

of RuIe 52(a): the :rrle was designed to take advantage of the-'

trial court's opSrcrtunity to observe live testimony; when that ability

has no applicability to an individual case, the rule loses its foree

and appellate courts should not hesitate to review.

Karavos Compania Naviera S.A. v. Atlantica t<port Corp" 588 g'2A

1, 7-8 (2d Cit., 1978) , contains the most extensive recent discussion

of this issue. Appellee's contention that the district court's finding

of agency was a finding of fact which feII within the scoPe of 52 (a)

,,flies

T ur" face of this court's long-held position reiterated as

recently as in Kennecott Coooer Corp. v. Curtiss-Wriqht Corp', 584

.(

'23

!'.2d 1195,1200 n. 3 that'[tJhe application of a 1egal standard

,

i

to the facts is not a "finding of fact" within the rule.''' lhe Court

'

. went'on to point out that neven the advocates of'.a broad reading of the

' . t,erm I finding of factr I " concede that errors in the interpretation of a

1egal standard to be applied render the whole determination subject to

reversal without the necessity of finding clear error. After discussing

the interpretations of the various circuitsr Karavos concludes:

It simple appears to us to be more consistent with the language

of the Rule, with clarity of analysis, and with the aPProPriate

roles of the district courts and the courts of appeal to salr

as we have been doing for thirty-five years, that the aPPlication

of a 1.ega1 standard, whether it is a "question of 1aw" or

not, is not a question of fact within F.R.Civ.P. 52(a).

Several circuits have discussed the subsidiary facl/uttimate fact

distinction. specifically as it applies to findings of discrimination.

The Fifth Circuit has been expecially concerned wiE,h this question.

United Sates v. ,Jacksonville Terrninql Co., 451 P.2d 418, 423-424 (5th

Cir., 1971), cert. deniedr 406 U.S. 906 {L972), was its first major

statement on this issue. fn this casel involving alleged violations of

Title VIf on the parts of both the employer and the unions, the Government

claimed that the district court judge had nerred in his findings of'ultimate

fact (such as conclusory statements that particular acts or series of

acts, did not establish the existenmce of discrimination or discriminatory

intent as defined in Title VfI), as well as his lega1 conclusions dervied

from the factual milieu." 451 F.2d at 423. The Court announced that

"ti]nsofar as the Government's attack is predicated on these grounds, the

'clEarly erroneous' rule is not a bulwark hindering appellate review. "

I , at 423-424. The Court's citation of Ejlger, supra, shows at least

that it was sensitive to Che fine distinction between "inferential"

secondary findings of fact and "Iega1' ones.

The Circuit continued to pursue this line of analysis in such

cases as Hester v. Southern Railroad, 497 E.2d 1374, 138I (sth Cir., L974),

ri

(-\

24

where it held t,hat a"conclusory finding of discriminat'ion is among the

class of ultirnate facts dealt with a conclusions..of law and subject to

revi.ew outsi.de the constrictions of Rule 52(a).n In.Causev v- rord

Irtotor co., 5I5 r.Za 416 (5th Cir., 1975), it elaborated on this view;

citing Baungartner's definition of an ultimate fact as one equivalent

to judgment itself, the Court declared that

Although discriruination vel non is essentially a question

"i i".i it is, at the saiEtiffi, the ult,imate issue for

resolution in this case, being expressly Proscribed by

42 lt.s.C.s20OO(e)-2(a). As srfch,-a f inding of -discriminationor nondisirimination is afinding of ultimat,e fact- .

fn reviewing the district court's findings, therefore, we

will pro"""6 io make an independent deteimination of appellantfs

allegitions of discriminatioir, though bound by findings of

suUsidiary fact which are themselves not clearly erroneous'

516 r.2d at 42L.

The Fifth Circuit's analysis here also echoes Parke Davis, G.M-, and

p!}31,, supEar where the Supreme Court seemed to be saying that a trial

court could not insulate its actual resolution of the issue being

tried before it from appellate review simply by terrning its determination

a finding of fact. The Fifth Circuit has repeatedly affirmed its

commitment to this viewpoint. See, e.g., East v. Romine, Inc" 518 F'

depth

same

r970 )

2d 332, 338-9 (5th Cir, L975) i Wade ssl

Service, 528 F.2d 508, 515 (5th Cir., 1976) i ?"ames v' Stockham valves and

Fittings Co., 559 F.2d 3iO, 352 (5th Cir., Lg77), cert' denied' 434 U'S'

1034 (1978); ParEons v. Kaiser A1uni , 573 r.2d 1374, 1382-3

(tth cir.,1978), cert. denied,44L u.s. 968 (1979); Crawford v'

western Electric co., Inc., 6L4 F.2d 1300, 1311 (5th Cir.r 1980), and,

of course, Swint v- Pullman-Standard'

While they have not dealt with this question in quite as much

as the fifth Circuit, three other circuits have used roughly the

analysis. In S-LrgItz v. Whealon Gla ., 421 E.2d 25g (3rd Cir.,

,g*@,398U.s.9o5(l97o),,theCourtexaminedac1aimof

i)

t'

23

sex discriminttion arisi.ng under the Equal Pay Act. The district court had

found that the enployer had met.the burden of proving that the disparity

in pay ,"". b-ased on factors other than sex and found -thaerefore that

the differences in pay were due to real differences ir, *ort performed. :;

Such a finding was !99 ptotected by 52(a), the Court held: 'We are not

. bound by evidence which has not reached the status of finding

of factr rlor by conelusions which are but Iegal inferences from facts'

[citing Baumsartner, @, and Sinoer] 421 ?2d at 267'

The Seventh Circuit, specifically depending on the Fifth

Cir.cuit's analysis in East v. Rominer.gPE,, and its own previous

holding in Stewart v. General Motors '(see Section IIIB, !g$),

held in United States v. Citv of Chicaqo, 549

"'2a

415, 425 (7th'Cir'r L977) '

cert. denied, 434 U-S. 835 (L977), that ndistinction must be drawn between

subsidiary facts to which the tclearly erroneous' standard aPPlies, and

the ultimate fact of discrinination'necessary to t'rigger a statutory or

constitutional violation, which is the decisive issue to be determined

in this litigation.' In Flowers v. Crouch-Walker Corp', 552 ?'2d L277'

LZ}A (7th Cir., L977), a case involving alleged racial discrimj.nation

in the dismissal of'a bricklayer, the Seventh Circuit reiterated its

adherence to this view:

[W]hen the factual deternination is primarily a matter of drawing

interencei from undisputed facts or determining their- 1egal

implications, appellale review is much broader than where

di-sputed evidenil and questions of credibility are involved.

The Eight,h Circuit expressed much the same view in Christopher

v. State of Iowa, 559 F.2d 1135 (8th Cir., 1977). This was a sex

discriurination case where the Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court's

decision for the defendant. Nevertheless, in discussing the standard

of review which it planned to apply to the district court's findings,

the Court said

The acceptance of the trial court's findings of fact does not

26

require that ue aPPlv Ehe crea"Yrlilogffi"d:'Hi::11"."

areteiting whether the conclusions d:

in accordance wit,h "it"Utished

lan. The scope of the clearly

'

"iron"or=

standard does not preclude such'.lnquiry' 559 F'2d

at 1138

Only the First Circuit has i position subs'tanti'al1Y at odds with '

this general consensus. 1n Sweeney v. Board of Trustee: of Keene State

college, 504 F.zd 106 (Ist Cir., LgTg) and !'lanninq v. Trustees of Tufts

co11eqe, 513 F.2d 1200 (lst Cir., 1980), the circuit, stated its position'

InSweenevrtheCourtrespondedtotheplaintiff'ssuggestionthat

the clearly erroneous standard didn't aPPly to Title VII discrimination

eases, because the "f,actual" finding tas equivalent to resolution of the

1egal issue of discrinination:

'we are not inclined Eo that approach. This circuit has applied

to the clearly erroneous stani-ard to conclusions involving.

mixed d;;Ei;;"-"i law and fact except when there is some indication

that tiie court nisconceived the lega1 standards. 504 F.2d at I09,

rn. z.

I@9', 613 P.2d at, I2o3r. noted this theory with approval.

Upon closei examination, however, neiLher of these cases is

apposite to general Tit]e VIf litigation. Both cases involved 'temure

decisions on individual faculty members. This is an extremely

idiosyncratic Processr oo€ in which extremely personal judgments are

made by colleagues, it in no way resembles decisions about seniority

systems, which operate 1e11-nigh automaticallyr oE entry-1eve1 jobs

in which personalily trdits ha:re -1itlle signif icance' Indeed' the

Court noted in both cases that live testimony had had a major impact

on the district court's decision:

. the opportunity for firsthand observation may be

esiec:.aify iinportant in [a.case] such as this, where the

isiue is itreti:er "personility" reasons trere sexually biased.

[Sweenev] 604 E.2A at 109

. the district court's judgment about credibility,

formed during o,- necessarily short heari.ng, must.have a large

;;;;i;g-o"-rri" conclusion lbout the underlying issue of

whether the complainant has been a victim of sex discrimination.

r)

'27

[Manninq] 613 F.2d at L204

(^.., In Section III C, I'11, examine the impact of live testinony on the

applicability of 52(a) in more detail. Suffice it to say here that

' ' 3 the question 'addfessta li" tf'" ..the questi6n ia these cases, unlike the questior ,. Ene

:-

cases I cited in the Thirdr Eifth, Seventhr and Eight Circuits, does

not involve undisputed facts and the aPPlication of 1ega1 standards,

but rather concerns the actual determination of basic facts (whether

the personality issue was dependent on the plantiff's sex-) As footnote

2 in Sweeney, .gp3, admits, misconceptions of 1egal standards are

excepted from the clearly erroneous rule's scoPe. This exception seems

much more akin to the rule expressed in the other circuits, than the

rule the First Ciicuit'propounds.

_ Especially given the tone of the Supreme Court's recent opinions

in Eryton Board of Education and ryLLB- supra (see PP' 9-10), I think

I that the prevailing mood on Rule 52(a) is that the district courtrs

applications of particular Iega1 standards is not Particularly

privileged. In fact, as vre sha1l see in the next section, the

intermingling of issues of law and. fact is so complete that' many courts,

rather than attempting the futile task of disentangling them, have taken

to treating the whole melange as a matter of Iaw.

28

!'TATTER.S OF FACT,A4ATTEES OF I'AW

{

B.

facts

Lg4, fn-

' "RuIe 52 (a) describes. the very narrow review t'hat may be

giventofindingsoffact.It,issilentaboutlegalconclusions.

This silence has been correctly interpreted as meaning that the

,clearly erroneous' restriction in not applicable and that the

trial court,s r:rrlings on questions of law are reviewable without

any sueh U:oitatiot1.., 9 wright, and Miller, Federal Procedure and

Practice 52588 (1971, P' 750) '

In $!gg95, $PE1, the Supreme Court decided that' a "conclusion

derived from the courtts application of an iruproper standard to the

. . may be corrected as.a matter of law'" 374 U'S' at

L, .*P31, also Presented

this view . 364 U.S. aE 526 (see p. 6, above.) since Baumqart+er

had already described this applicatiop of a standard of law to'

the particular facts of a case as a findj-ng of ultj:nate fact'

Iower appellate courts often have seemed confused as to which

catggory--questionoflaworqrrestionoffact--ureimatefacts

ought to be included in. lhe second circuit''s answer in Karavos'

supra -- Ehat whaEever a findS.ng of ultirnate fact turns out to be'

Rule 52(a) doesn't apply to it -- is probably the most prag:matic

o

approach.

AlthoughnoneoftheothercircuitshasComeoutwith quite

()

soPragmaticanaPProach,severalofthemhavetreatedt'he

issue of statutorily-prohibited discrimination in much this fashion'

The existence of discriminati-on in these cases straddles the

Iine between question of fact and question of law with almost

incredible agility. on the one hand, the existence of discrimination

is a factual, statisEic issue which the plaintj-ff must dernonstrat'e

in order to make out a prima facie case. on the other, it' is

29

the ultimaEe issue to be established by Ehe litigatsion, as

U.s,-y'-c-hig-aqo., .ggp,5,.3., amongr others, has poirrted 6ut' Given

the Suprerne Court's analysiS in the $*[ t""i, .9gp!1' that' t'he

"ullimate conclusion by the trial judge ' ' ' ' i's'+oE to be

shielded by the 'elearly erroneous' test embodied in Rule 52(a),"

384 IJ.S. at L42, fn 15, most Cor:rts of Appeals have reviewed district

courts, findisrgs in discrimination cases with less compunction

about interference in the trial courts' bailiwick than Ehey normally

show, Since to exercise no:mal deference here would be, in

essence, to rr:bber stamp any lower court decision.

.

'Ihe Fif,th circuit has frequently commented on the question

of the proper pigeonhole for discrinuination cases. In !!g!95,

-E3PE, it placed " [t,] he conclusory finding of discrimination

among tshe class

Iaw and subject

4g7 p.2d at 138I. In EEEgg, .Es!E., it elaborated on this view:

We are qi=o caref,ul in discriruination suits, where t'!re

elements of fact and law become Snrticularly j.ntermeshed, of

the distinction between findings of subsidiary fact and

findings of ultj:nate fact. A iina:-ng of nondiscrirni-nation is

; finding of ulti:oate fact that can be reviewed free of the

clearly lrroneous rule- 575 f.2d at 1382-3'

Crawford, EEEI, 614 F.2d aE 1311 also reflects this perspective:

"Ehe ultirnate lega1 issue i.n a Tit1e VII or section 198I case

is whether discriraination occurred, although this question is also

one of fact.. A1I of these opinions demonstrate the difficulty

of deciding whether or not the "clearly erroneous" rule governs

revie*r of findings in discrj:nination cases. The Fifth Circuit,'s

appreciation of the fine distj-nction -- shown in its differentiation

between the ultimate finding of discrimination and lh" subsidiary

factual findj-ngs which underlie this final determination (and

its deference toward the decisions of the trial court in regard

to the latter) -- certainly is not "symptomatic of a general disregard

of,

to

ultiaate facts dealt with as conclusions of

review outside the constrictions of Rule 52 (a).;'

(t

30

. . . disregarrd for the proper allocation of resPonsibilities betlveen

district courts and courts of appeals in deterrnining the

existnce of discrj:ninatory PurPose jJr Tit1e \rII cases, " Pet. Brief"

at fg-10.' Rathet, it manifests special sensitivity toward I'--

lEeserving the proper spheres of relative autonomy for both

judleial levels, since it authotj.z* broad intervention only in

that facet of a discrirainati.on cases which involves matters of

law.

The Seventh Circuit has also followed this hybrid approach-

U.S. v. Chicaqo and gry[9{a.!}cg, ElE5,1, (see p' 25 above)'

recognized the matter of Iaw eomponent in the question of discrirnination

and confi::ured the Circuit's decision in Stewart v. Gerleral liotors

g@-, 542 F.2d 445, 449 (7th Cj-r. , L976), cert. denied ' 433 u.s.

919 (tg76), reh. denied, 434 u.s. 881 (L977), not to adhere to

ttre ,,c1early erroneous" standard in reviewing trial court

dete:minagiong of discri:nination. Independent exaraination of the

dl.strict court,s interpretation of the subsidiary facts is therefore

appropriate.

In contrast to this more moderate aPProach,. the SiJ(th

Circuit has taken a far ruore interventj.onist Srcsition on the

nature of findings of ultimate fact. In Povner v. Lear Siegler, Inc.,

542 t.2d 955 (6th Cir., Lg76), cert. denj-ed, 433 u-s. 908 (1976),

a case concerning whether or not treatment as a corPorate entity

would lead- to an rrnfair hardship, the Court held ttrat:

The fact that a trial court labels determinations as

;findings" does not make thera so if they are in.reality

conclusions of law. In that case, they are subject to

r:nrestricted review. . . . If a determination concerns

whether the evidence showed that something occurred or

existed, it is a finding of fact. Elowever, if a determination

is made. by processes of legal reasoning from, or interpretation

of the legal significance of, Ehe evidentiary facts, it is

I

l/\

a matter of law [citing Galena Oaks, supra] '

at 959.

31

542 F.2d

It,: interesting to note how the Sj:<th Circr:-it transforms the

.Galeila,oaks presctiption. In salena oaks, tile Fifth circui.t

,r.:-

leve1i of review for

findings of subsidiary and ultimate fact (see section III C,

belOw , |1or a more complete discussion of ttre spect4:m of review

approach.) 218 E'.2d at 2tg. Although it exempted the application

Of legal standards frOm the "clear]y'erroneous" requirement,

the Fifth Circuit never went so far as to say that the question

involved soleJ.y legal matters. The Sixth Circrrit, has forcefully

expoundeo lust such a 5rcsition. In Detroit Police Officers'

Association v. Youns, 608 t.2d,67L (6th Cir', 1979), S@{'

4gg.s.t.w._(].981),theCourtspecifica1lyappIiedits

view to a discrirulnation case. In holding that the district court's

f,indJ-ng that, there had been no showing of prior dj-scrimination

against blacks by the Dettoit Police Departsnent was "based gn

errors of law and an i:npe:.uissably restrictive view of the

evidence,,, the court of Appeals came right out to say that

,.whether prior discriminaEion occurred is a conclusion of law lmy

eurphasis] based on sr:bsidiary facts [citi.ng U.S- v. Chicaqo, E-]1p53]'"

608 F.2d at 686. Eere too the Sixth Circuit goes beyond the

precedent on which it relies, since the Seventh Circuit in U-S- v.

Chicaqo found both factual gg! Iega1 considerations in the ulti:nate

finding of discri:aination -

Given the case law I've exa.urined in Sections III A and B, I

think it's accurate to say that the second' Third' Fifth' sixth'

Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Cireuits reflect a g:eneral consensus

that when treating an ultimate issue of fact as .a

question of

fact to which RuIe 52 (a) applies would preempt appellate consideration

(

;-\'.J

.32

I. of the trial corrlt,,s actr:al resolution o! the case, that ulti'mate-,

1,-',. fact ought to be viewed as a matter of law. The five circuits

whichbaveaddressedtlrisprobleminthecontoctofdiscrirnination. 'l

'' . Utigition seem fir:ily convj:rced that the only apSiropriate

treatment for discri.mination cases is to treat' them as matters

of,lawinwhichtheyhavefu].lPowersof,review.

C. PAPER CASESAET}TESS CREDIBILIT':T CASES

Both in those cases where it has justified adherence to

the ,,clearly erroneous" Standard, such as Igff@., gBE

gank, oreqon Meqical societv, and i-n those cases where it has

for:nd a broader scope of revien appropriate' such as G'9I19-4'

Motors and..L9!I.9J,, the Suprerre Court has taken pains to discuss

the relative advantages of trial and appellate courts j-n assessing

t6e evidence. The najor difference is Srciated to in the language

of the Rule itself: ,,. and due regard shall be given to the

opportrr'ity oi the trial cotrrt to judge of the credibility of

the witnesses-" While all cor:rts have'generally recognized that

this additional phrase does not mean that onlv in cases where

- witness credibility is a cn:sial issue should the "clearly erroneous"

standard applY,. many decisions suggest that the inportance of live

testimonyshouldbetakenintoaccor:rrtinfixingtheburdenof

showiag ,,erroneousness,, which the JPPellant must meet. rn addition

to the case Iaw, tacit approval for thj-s Srcsition can be gleaned

. from tbe rejection of the 1955 prolrcsed amendment to 52 (a), which

would have mandated egual standards for live and paper cases.

See P- 5 aI'ove.

{ Orvis v. Iliggins, l8O F.2d 537 (2d Cir., I95O), cert- denied, 340 U.S.

-..'' g1O (1950), vras t,he first case to suggest Ehat a spectrun of levels

of review was appropriate. [Whi1e Baumgartner had mentioned that

,

33

"ItJhe conclusiveness of a'finding of fact'depends on the nature

of the materials on which the finding is based," 322 u.S. at' 670,

oecificallv referred to the 'c1eirly erroneous' standardit neither specifically referred to the

nor addressed the problem in the context of'the "documenLary"/"1ive"'

distinction werre concerned with here.J Faced with the supreme

Court's placing "inferences drawn from documents or undisputed facts"

firmly within the protection of Rule 52(a) [Gvpsum, 333 U'S' at 3941'

Judge Frank stated that there were "approximate gradations" to be

made in the standard of review: "rf [a trial judge] decides a fact

issue on trrit.ten evidence aloner w€ are as able as he to determine

credibility anq so vre may disregard his finding." 180 F.2d at 539'

while Judge Frank's position that an appellate court is completely

free to disregard a trial courtrs findings of fact in a case decided

on documentary evidence has been roundly criticized, many opinions

have discussed the aPProPriateness of a broader standard of review

in cases whictr. do not depend on demeanor evidence.

The General Motors case, 9]gPI3., provides the Suprerne court's

clearest discussion of the question. The "rationale behind Rule 52 (a)

as set out in Oregon tledical Societvr ggplg, is nthe trial court's

customary opportunity to evaluate the demeahor :td thus the

credibility of the witnesses," the G.!t. opinion declared. In a case

where'of the 38 witnesses who gave testimony, only three appeared in

person [and] [ts]he testimony of the other 35 witnesses was submitted

either by affidavi.t, bY deposition, or in the form of an agreed-upon

narrative of the testimony given in the earlier criminal proceeding

before another judge," 384 U.S. at 14L-2, fn.16, this rationale

disappe,ars and the reviewing court should not be as hesitant in

revewing in the trial court's decision as it. normally might be. This

same G.M. footnote also Provided the appellation "paper cases" by

34

documentary cases have come bett'er known' ,

majority of the circuits have come to the eonclusion that

paper cases are to some degreee or another less protected by the

.'c1ear1y erioneous" rule than '!1iven cases' are. The Second Circuit''

as its leading case, Orvis v- Eiggins, !.g!E,,---indicates' has been

one of the most interventionist circuits. rn united stat'es ex rel'

Laskv v. LaVal1ee, 472 F.2d 960, 953 (2d Cit., L973), it reviewed

a habeas corpus action and, citing orvis v. Hiqgins with approval,

held that:

where the factual findings of the district _jldge are made

solely on the babis of an interpretation of docustentary

records, and the credibility of-witnesses is not in issue'

. we r.y *.k" oor own indepenlent factual determination. n

Although it never explicitly refers to this factor, the opinion hints

that the court may also be influenced by the deprivation of rights

issues invoLved in a habeas petition. See Section fI B, above ' foc

a more detailed discussion of the special responsibility of appellate

courts in cases involving the deprivation of constitutional rights'

The Fifth circuit has also discussed the aPProPriateness of

a 'spectrum' approach- fn Galena Oaks, ESPI9z it said:

tTlhe burden of showing a finding of fact "c1early erroneous"

is not a Eeasure of exact an uniiorm weight '1he burden

i" especiilly strong when the trial court has had the

oppbrtunity, not poss."i"a UV th9 appellate court, to see and

hear the witnesses, to obserie theii-demeanor on the stand'

andtherebythebel,tertojudgeoftheircredibi1ity.

The burden'is lighter, ,u.6 lighter, when we consider logical

inferences drawn from undisputed facts or from documents,

though lhe "clear1y erroneoi.rs" rule is sti1l applicable'

218 ?.?d at 219.

since t,he definition of "clear1y erroneous" in Gvpsum-is ultimately

so nebulous that- "the reviewing court lUel left with the definite

and firm conviction that a mistake has been mader'333 U'S' at

395 it should be clear that the Galena Oaks formulation affords

an appellate court ample latitude in revewing PaPer cases. That

makes eminent sense in light of the whole PurPose behind Rule 52 (a) :

(

(_:

I

,,

35

to Ehe extent that an appellate court has before it precisely

the same evidence as the trial court had had, its conviction

that a misi,ake has been made will certainly be fi'rmer and more

definite than if it has to reconstiuct the materiaL from which

the trial court made its determination. I t,hink this concePt

is crucial in understanding the "1ive case"/"paper casen distinction:

regardless of the appellate court's professions of inclusion in,

Or exemption from, the "clearly erroneous" rule, the threshhold fot

reversal will inevitably be lower in paper cases, since the reviewing

court will be less inclined Eo ascribe a trial court's determination

with which it disagrees to factors "which elude print'" Baumgartner'

322 at 670.

This analysis underlies the Fifth circuit's later cases as

o ^ i)'.,

*r'-"-

4g2 E.2d 508, 5L2 (5th Cir., Lg/4), the Court explained that:

the presumptions under this rule normally accorded the

tr1ai courl,s findings are lessened where the evidence

consists of documentiry evidence, depositions, and

isituations

"fr.i. crediUitity is not seriously.involved

"il

-ii it is, where t'he revilwing court is in jugt.l?

gooa-; ;;"iii.". ii the Erial couit to judge credibilitv"'

5a Uoorl 's Federal Practice t!52. 04 ( 2d Ed. 1959 )

ii

The circuit confirmed its de facto adherence to this spe-ctrum approach

in Jenkins v. Louisiana state Board of Educatign, 506 F.2a,992

(5th cir., 1975), where, after stating that in a who11y documentary

case, 'the appellant',s burden of showing that the trial court's

findings of fact are clearly erroneous is not as heavy as it would

be if the case had turned on the credibility of witnesses appearing

before the trial judge, n the Court went on to state that it would

not "overturn the decision of the trial court unless we are 1eft

with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been

36

made," 505 E.2d at 995 the language from qpsum, .=:upra,

,

describing the condition under which a lower court's finding of

/--t('; fact is nclearly erroneous.'r ft's cIear, t,henr,thatralthough the

Fif th Circuit -claims that it's. adhering to the "clearly erroneous"

standard, it's a much more lenient standard than the one which

normally applies.

The Seventh and Tenth Circuits

In Flowers v. Crouch-Walker., supra,

Seventh Circuit applied the "broad

enunciated in Yorke v. Thomas fseri

Recently, in Cit

also follow this aPProacb.

a discrirnination case, the

scope of review" first

Produce Co, 418 F.2a 811, 814

(7th Cir., 1969). ft exPlained

In revewing this finding we are bound by the "c1ear1y

erroneous' standard of Fed.R.civ.P. 52 (a) . Ilowever,

two factors in the case justify a broad scoPe of review

within the limits of thaL standard. First, the evidence

at trial consisted almost enli.-reIy,qE,-Ehe testimony o!

a single witness, I{9g9.c-r_ea_f'f ility was not cha1lenged.

The bisic facts of'EEF&-sE ?erir not in dispute'

[W]hen the factual determination is primarily a matter

of drawing inferences from undisputed facts-or

determiniig their lega1 implicationms, appellate review

is much broader than where disputed evidence and

questions of credibility are involved.

552 ?.2d at L284

This passage also sets out the connection between the "aPPlication

of 1eg?-1. standards" analysis we looked at earlier in Sections III-B.

and IfI.C. and the "p'"pe, case' anlysis we're considering here.

As the issue on aPPeal moves aeray from one dependent on witness

credibility, it tends inevitably to approach one which involves

the making of legal inferences and hence is not subject to 52 (a) 's

restrictions. The decision not to apply a rigid formulation

of Rule 52 (a) thus usually rests on two grounds -- the npaper case"

passage from G.M. and the 1ega1 standards arguments from Baumgartner

and its progeny.

of Mishawaka Indiana v. American Electric

Power Co.,616 F.2d 976,979.(7th Cir., l98O), the Circuit, although

declining to oPerate under

broader scope of review was

it, in this case' recognized Ehat a

appropriate in paPer cases. Aetna

Casualty and Surety Co. v. Hunt, 486 F.2d 81, 84 (10th Cir., L973)

set out the Tenth Circuit,'s approach to PaPer cases:

rn a series of cases, this court has held that in the

absence of oral testimony, the appellate court is egually

as capable as the trial court of examining the evidence

and diawing conclusions therefrom, and that we are under

a duty to do so. . [Documentary findings] do not

carry the same weight on appeal aS findings based entirely

on oral testimony. In dealing with all such documentary

evidence, the trial court is denied its normal advantage

of an opportunity to judge the credibility of the

witnessll. . Though this lack of oPPortunit'y to

observe the witnesses establishes the appellate court's

duty to evaluate documentary evidence in an equal capacity

witL the trial judger H€ are loath to overturn the

findings of a trial court unless they are clearly erroneous.'

Jenningsv.c,6o4F.2dI300,1305-5(IothCir.,

L979) reaffirmed this view.

lhe Sixth, Eighth, and District of Columbia Circuits take a

less cautious- Position and assert outright that the "c1early

erroneous" rule does not aPPIy in many PaPer record cases. In

Universitv Eil1s, Inc. v. Patton, 42i F.2d 1094, 1099 (6th Cir.,

1970), a case involving the question of contractual use restrictions

on some land tracts, the Sixth Circuit declared that the

interpretation of written contracts was "not subject to the rule

and . [is] within the competence of an appellate court. "

In Frito-Lay, fnc. V. €e-Sgod po!e!p-!h-tP-Co--, 540 F.2d 927, 929,

(8th Cir., l9?5), the Eight Circuit held that "where, ES here,

there is no dispute as to the evidence upon which the District Courtrs

findings are based, where Ehere.are no credibility issues before

this Court. ere are not confined by the clearly erroneous standard