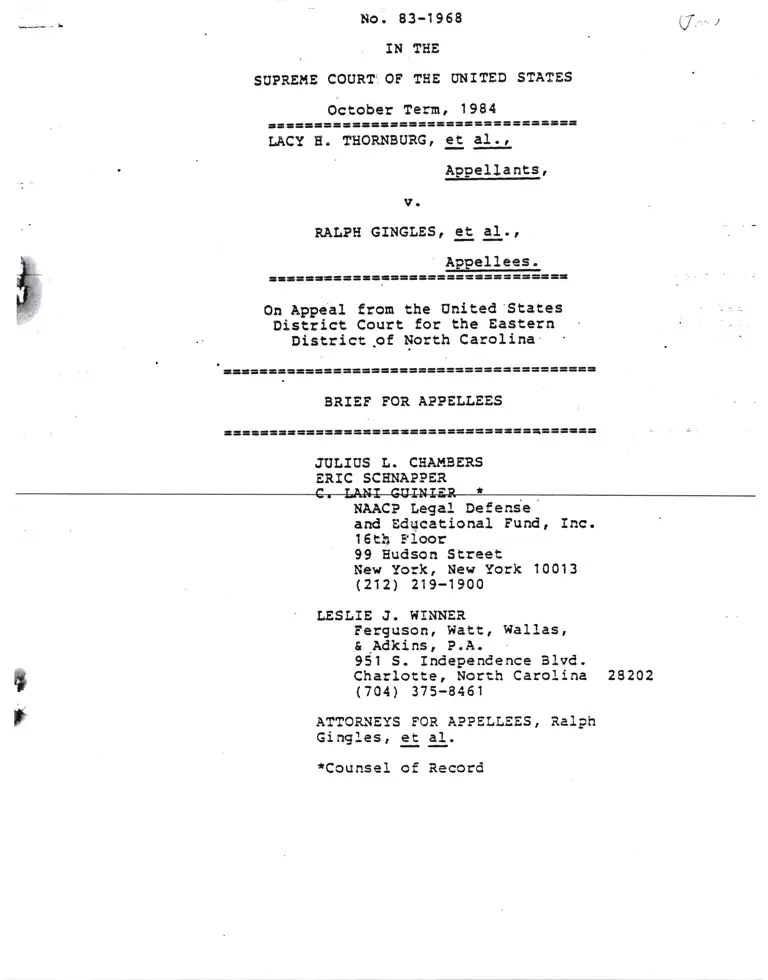

Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

August 30, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Brief for Appellees, 1985. dc97532b-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/16722f1a-5158-48b0-8ad5-80767b3a4341/brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

No. 83-1958 l/,-,., t

IN TEE

SUPREITE COURT: OF IEE UNITED STATES

OcEober Term, I 984

at a=ar8- - rt=8tr- t=r-=t -a a a - -= ---t

IACY E. THORNBURG, EE Af . T

l-tniln.",

V.

LPH GINGLES r !! 4. ,

' APPellees.

trt==--8= 3 r=--ttl=-===-=t = ==== -t

On Appeal fron the trnited.States

District Court for the Eastern '

District .of North Carolina

---ar--tt--ta =:t=!t=3= - =t-a====-= 3= = == ====:t

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

-!lat-t-a-atrl=--==--a=======-a==a==-r-g

: a

JULTUS L. CBAI.TBERS

ERIC SCENAPPER

I

r

NAACP Legal Defense

and Edueaeional FundI Inc.

16EI Eloor

99 Eudson Street

New York, New York 10013

1212) 219-1900

LESLTE J. WTNNER

FergusoR, Idatt, l{a1las,

g.Adkins, P.A.

951 S. Independence tslvd.

Charlotte, North CaroLina 28202

( 704 ) 37s-845 1

ATTOR.\EYS FOR APPELLEES, R,A1Ph

Gi ng1es, g! gI.

rCounsel of Record

a

il

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

( 1 ) Does section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act require Proof that

minority voters are totallY

excluded from the Po1itical

process?

(2) Does the election of a 'minority

candidate conclusively est,ablish

the existence of equal electoral

opportunity?

(3) Did the district court hold that

section 2 reguires either

proportional representation or

guaranteed minority electoral

success?

t

t

({) Did the dlstrlct eourt cor-

rectly evaluate the evldence of

raclally Polarized votlng?

(5) WaE the distrlct courtrs ftndlng

_ . of, unequal electoral opPortunity

' -=- -'- ---icl'early Grroneougt?

1t

t

p

i

e

r

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presgnted .. o........... i

Tablg of Authorlties ............. vi

Statement of thg Case ............ 1

Findings of the District Court ... 7

Suramapy of Argument ........o...o. 15

Argument

I. Section 2 Provides

It{inority Voters an Equal

Opportunit,Y to Elect

Representatives of their

Choicg ................. 19

A. The Legislative EistorY.of

$ha lOa, lnanAmani af

?

t

Section 2 .. .. o. o .. o. .. . 21

B. Equal Electoral Oppor-

tunity is the Statutory

Standard ............... 44

C. The Election of Some

l,tinority Candidates Does

Not Conclusively Establish

the Exist,ence of Equal

Electoral Oppor-

tunity ............... 50

111

II.

III.

rv.

Page

The District Court Re-

quired Neither ProPortional

Representat,ion Nor Guaran-

teed Minority PoIitica1

Success .........o......... 64

The District Court ApPlied

the Correct Standards In

Evaluating the Evidence of

Polarized Voting ....... ...' 70

A, Summary of the District

Courtrs Findings ...... 73

B. The Extent of Racial

Polarization was Sig-

nificant, Even Where

Some Blacks lilon ....'... 76

C.- Appellees were not Re-

quired to Prove that White

Votersr Failure to Vote

for B1ack Candidates was

Racial.ly llotivated .... 81

D. The District Court's

Finding of the Extent of

Racially Polarized

Voting is not ClearlY

Errongous .o..........r 88

The District Court Finding

of Unequal E1ectora1 OPPor-

tunity Was Not Clearly

Erroneous ....o............ 95

A. The AppIicabilitY of

Rulg 52 .............. 95

1V

i

p

t

B.

c.

D.

B.

E

(lo

Page

Evidence of Prior

Voting Discrirni-

natiOn .............. . 102

Evidence of Economic

and Educational Dis-

advantages ........... 107

Evidence of Racia1

Appeals by White

Candidatgs ........... 113

Evidence of Polar-

ized Voti.ng ........o. 118

The t{ajority vote

Requirement .......... 118

Evidence Regarding

Electoral Success of

}{inority Candi-

dates ................ 121

Issug ................ 130

I. Tenuousness of the

State Policy for Multi-

member Districts o... o 1 31

Conclusion ... . . ... . .... .. .. . o..... o. 1 35

Page

Cases

Alyeska Pipeline Service v' Wilder-

ness SocietY, 421 U'S'

240 (1975) """""..""" 100

AndersoD v, CitY of Bessemer

City, U.S.

-,

84

;:;a: zrsia- i tgE'si .. o "' 16'e8'ee

Anderson v. t'tills , 664 F'2d 6,

500 (5th Cir. 1981) """"'

Bose CorP. v. Consumers-Union'

80 L.Ed.za-ic2 (1984) """' 98

Buchanan v. CitY of Jackson'--- -ioa F.2d 1055 (5th cir' o(

1983) tttt--"""t""""" zw

City of Port Arthur v' U'S' 7

517 F. SuPP. 981, 3j!.1!!ry| ^F r^A

459 U.S' 159 (1982) """" 6)1tzv

CitY of Rome v. U'S' t 446 U'S'

156 (1980) "".."'oo"' 72r99'120

Collins v. CitY of Norfolk'

758 F.2d 572 (4th Cir' A2

JulY 22r 1985) "o"""""' Yo

TABLE oF AUJgoRrrrEs

-vr

Cases

Connecticut v. Teal, 457

U.S. 440 (1982) """""o"

Baxter, 504 E.2d 875

Page

56

110

110

50

36

107

63

Cross v.

( 5th

David v.

( 5th

Cir. 1979) .......... o. '

Garrison, 553 F.2d 923

Cir. 1977 ) ...... ..... "

Dove v. Moore, 539 F.2d 1152

(8th Cir. 1976) ..."""""

Ernst and Ernst v. Hochfelder,

425 U.S. 185 (1975) --.-....--

Garcia v. United States, -

U.S'

105 S.Ct. 479 (196T) .-..

Gaston CountY v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969) --...o..-

1 389 ( 5th Cir. 1975) . .... ... 95

Harper & Row, Publisher v.

Nation, - U.S.

-.

85 L.Ed' 2d

588 (1985f.....-T--...-... 9E

Hendrick v. Walder, 527 F-2d 44

(7th Cir. 1975) ..-..-....... 110

IIe ndrix v . JosePh , 559 F. 2d

1265 ( 5th Cir. 1977 ) . ... .. .. 96

Hunter v. Underwood, U.S.

-l85 L.Ed.2d 222 (T5g5l ...7. 99

-vii-

Page

Cases

Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727

F.2d 364 (5th Cir" 1984);

rehrg en banc denied, 730

F.2d 233 (1984) o"ocooc.. 88r96r130

Kirksey v. Bd. of Supervisors, 554

F.2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977 )... 56

_ Kirksey v. City of Jackson, 699

.. F.2d 317 ( 5th Cir. .1982) . . . . 84

Lodge v. Buxton, Civ. No. 176-

55 (S.D. Ga. 10/26/78), aff 'cl

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S.

513 (1982) .oo........o...... 80

MajoE.vo Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325

(8.D. La. 1983) (three judge

COUft) ....o................ 56r71 r78

McCarty v. Henson. 74g F.zd

1 1 34 ( 5th Cir. 1984) , aff'd

753 F.2d. 879 (5th CirI-

(1985) ...................... 96

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F. Supp.

380 (N.D. Ga. 1984), affrd 753

P.zd 877 ( 5th Cir. 1985T:. . . 85

McGill v. Gadsden County

Commissionr 535 F.2d 277

( 5th Cir. 1976) .. .... ....... 96

Mcl'lilIan v. Escambia County, 748

F.2d 1037 (11th Cir. 1984) .. 108r130

Itletropolitan Edison Co. v. PANE,

450 U.S. 766 (1983)

viii-

98

Page

Cases

lrlississippi RePublican Execu-

tive Cornmittee v. Brooks,

u.s. , 105 S.Ct.

TTE (1984J-.........-...--.! 85

llobile v. Bo1den, 445 U.S. 55

(198O) ..o... ot''''''''''22'23'24'30'

82

NAACP v. Gadsden CountY School

Board, 691 F.2d 978 (1lth

Cir. 1982) .........".."i.. 80

Nevett v. Sides r'571 F-2d 2Og

(1978) ......t''oo'o'o"""'

Parnell v. RaPidas Parish School

Board, 553 F.2d 180 (5th

Cir. 1977) ......".."""o'

Perkins v. CitY of West Helena,

675 F.2d 201 (8th Cir. 1982),

58r69

96

TT98217.... o....... -......-- 85

Rogers v. todge, 458 U-S. 613' (19821 ..o....o."' 79t80,85'99'130

Sout,h Alameda SPanish SPeaking

Org. v. CitY of Union

City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th

Cir. 1 970) .. ... . . .... .. .. ' " ' 84

Strickland v. ltashington, U. S.

_t 80 t.Ed.2d 674 (Ty64) - - 98

United Jewish organizations v-

Carey, 403 U.S. 144

(1977) ........"..""""" 68

1X

Page

Cases

U.S. v. Bd. of Supervisors of

Forrest County, 5'11 F"2d

951 (5th Cir" 1978) .ocooo..G 56

U.S. v. Carolene Products Co.7

304 u.s. 144 (1938) .....o.oo 71

U.S. v. Dallas County Commission,

739 F.zd 1529 (11th Cir.

1984) .........o...... ....... 97

'U;S. v. Executive Committee of

Democratic Party of Greene

County, AIa. 254 F. Supp.

543 (S"D. AIa" 1956) "o...... 84r85

U.S. vo [larengo County Comnission,

731 F.2d 1546 (1lth Cir.

1984) ................. 56r57 r85196,

Velasquez v. City of Abilene,

108,130

725 F.

1980)

2d 1017 (sth Cir.

56r95

$Iallace v. Eouse, 515 F.2d 619

(5th Cir. 1975) ............. 56159

Whitconb v. Chavis, 403 U"S.

124 (1971) .........o.o...... 129

White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 ( 1e73) passim

Z immer v. ttlcKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1973)(en banc),

affrd sub nom East Carroll

trtET-sh-Ehddf Board v. llarshal1 ,

424 U.S. 636 (1976) .... 30r55r58r96

-x

Page

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Statutes

Section 5, Voting Rights Act of

1965, 42 U.S.C.

S1973c .....,.....""' 3'4'22'133

Voting Rights Act Amendments of

1982r Section 2,

96 Stat . 1 31 , 42 U.S.C.

SigZf .........".."""" $!$

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

RuIe 52(a) ....o...... . 67 r98r100r101

Constitutional Provisions :

Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amgndmgnts ........' " "'." PaSSim

House and Senate Bills

H.R. 3198, 97th Cong., lst Sess.,

52 . .. . . . . . . . ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' 23

B.R. 3112, 97th Cong., lst

Sess., S2O1 ........""" 23

Senate Bill S. 1gg2 .. o........ 33 t34r36

Congressional BePorts

House Report No. 97-227, 97th

Con!., lst Sess. ( 1 981 ) Passim

I

Senate RePort No. 97-417 | 97th

cong. , 2d Sess. (1982) -.. Passim

-xi

Page

Congressional [learings

Hearings before the Subcommittee

on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House JudiciarY

Committee, 97th Cong., 1st Sess

(1981) .o.."""'""""" 23

Hearings before the Subcom-

mLttee on t'he Constitution

. of the Senate JudiciarY

Committeeon S.53, 97th Cong.r

2d Sess. (1982) ....-.... 28r34r35r411

42r43

Conqressional Record

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed- oct.

2, 1981) ....."'o"""" 25'26,-29

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed- r Oct-

5, 1981)....'o""""" 26. 27'29

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed. Oct.

15, 1981)......""""'

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed. June 9,

1982) ......"o"""' 35'37'40'47

48 r54 t82

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed. June 10t

1982)......c..."""-"o' 35'37

128 Cong. Ree. (dailY ed. June 15,

1982) ..o....."""".-' 29,34'3'7 r82

128 Cong. Rec. (dai1Y ed- June 16,

1982) ..o......"""""' 56

29

- xll -

Page

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed. June 17,

1982) .................. 31r34.37 r39

4g r53 rg2

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed. June

18, 1982) .......... 29r37r46148t53

72,82

128 Cong. Rec. (dailY ed. June

23r 1982) ................ 34

iliscellaneous

Joint Center for PoIitical Studies

National Roster of Black

Elected Officials

( 1984) .. .. .. . .. ...... . .. . .

Ios Angeles Times, IlaY 4 |

1982 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . ' ' '

WalI Street Journal, llay 4 |

43

New York Times,

p. B'7, coI.

Dec. 18, 1981,

4 ...aa....... 41

- xr11-

STATEMENT OF THE CASEI

This is an action challenging the

districting plan adopted in 1982 for the

election of the North Carolina Legisla-

ture. North Carolina has long had the

smallest percentage of blacks in its state

legislature of any.state with a substan-

t ia1 black popuIatio,..2 Prior to this

Iitigation no more than 4 of.the 120 state

representativesr oE 2 of the 50 state

l--

The opinion of the district court as

reprinted in the aPPendix to the

Jurisdictional Statement has two signifi-

cant tygrcgraphical errors. The Appendix at

J.S. 34a and 35a stAtes, "Since then two

black citizens have run successfully in

the (llecklenburg Senate district) ...'

and oIn Halifax County, black citizens

have run successfully...' Both sentences

of the opinion actually read trhave run

unsuceessfully.' (Emphasis added). Due to

EEese and other errors, the opinion has

been reprinted in the Joint Appendixr at

JA5-JA58t .

See Joint Center for Political Studies,

National Roster of B1ack Elected Officials

)-

senators, were black-3 Although blacks are

22.4t of the state populationr the number

of blacks in either house of the North

Carolina legislature had never. exeeeded

4t. The f irst black was 'not elected to

the Eouse until 1958, and the first black

state s€nator was not elected until 19'74'

North Carotina .makes greater use of at

Iarge legislative elections than most

other states; under the 1g82 districting

plan 98 of the 120 rePresentatives and 30

of the 50 sEate senat'ors were to be chosen

from multi-member districts. 4

In JulY 1981, following the 1980

census, North Carolina initially adopted a

redistricting plan involving a total of

1 48 multi-member and 22 single member dis-

94-5.

and EE, ChaPters 1 and 2

2nd Extra Session 1982, JA

3

4

St ip.

sr iP.

Sess.

67.

96,

Ex.

Laws

JA

BB

of

{-

J

trtricts.' Under this plan every single

Eouse and Senate district had a white

majority.6 There was a population devia-

tion of 221 among the proposed districts.

Forty of North Carolina's 1 O0

counties are covered by section 5 of the

Voting Rights Acti accordirryly, the state

was required to obtain preclearance of

those portions of the redistricting plan

which affected those 40 counties. North

Carolina submitted the 1981 plan to the

who entered obiections

to both the House and Senate p1ans, having

concluded that'the use of large nulti-

member districts effectively submerges

cognizable concentrations of black

Stip. Ex. D and E', Chapters 800 and 821

Sess. Laws 1981, JA 51.

The opinion states one district rras

majority black in population, JA7,

referring to the second 1 981 pIan,

enacted in October after this lawsuit was

filed. Stip. Ex. L, JA 62.

4

population into a urajority white elec-

torate.r StiP. Exn N and O, JA53. For

similar reasons, the Attorney General also

objected to Article 2 Sections 3(3)and

5(3) of the North Carolina Constitution,

adopted in 1967 Oo: not submitted for

preclearance until after tbis lawsuit was

filed, which forbade the subdivision of

counties in the formation of legislative

districts. StiP. 22, JA 53-

ApPellees filed this action in

Septenber 1981, a11e9ing, inter alia, that

the 1 98 1 redistricting plan violated

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the

Fourteenth Amendment. Following the

objections of the Attorney General under

section 5, the state adopted two subse-

quent redistricting plans; t'he complaint

was supplemented to challenge the final

plans, Idhich were adopted in April, 1982.

Stips . 42r43i JA 57. In June 1982 Congress

,5:

_ amended section 2 to forbid election

practices with discrininatory results, and

the complaint was amended to reflect that

change; thereafter the litigation focused

primarily on the application of the

. amended section 2 to the circumstances of

this case. Appellees contended that six

of the multi-member districts had a

discriminatory result which violated

section 2, and that the boundaries. of one

single member district also violated that

provision of the Voting Rights Act.

After an eight day trial before

Judges J. Dickson Phil1ips, Jr.1 Franklin

T. Dupreel Jt.1 and W. Earl Britt, Jt.,

the court unanimously upheld plaintiffs'

section 2 challenge. The court enjoined

elections in the challenged districts

pending court approval of a districting

plan which did not violate section 2.7 By

Appellees did not challenge all multi-

6

subsequent orders, the coutrt approved the

State I s proposed remedial districts for

six of the seven challenged districts. The

court entered a temporary order providing

for elections in 1984 only in one dis-

trict, former House District No. 8, after

appellants I proposed renedial plan i'as

denied preclearance under section 5. The

remedial aspects of the Iitigation have

not been challenged and are not before

this Court.

On appeal appellants have disputed

the correctness of the three judge

district courtrs decision regarding the

Iegal ity of five of the six disputed

multi-member districts. Although appel-

lants have referred to some facts from

member districts used by the state and

the district court did not rule that the

use of nulti-rnember districts is Pe-r-

se il1ega1. The district courtrs orffi

Eaves untouched 30 nulti-member districts

in the House and 13 in the Senate.

7

House District No. 8 and Senate District

No. 2, they have made no argument in t,heir

Brief that is pertinent to the lower

court t s decision concerning either of

these districts.S tike the united states,

we assume that the correctness of the

decision .below regarding' House Distriet

No. I and Senate District No. 2 is not

within the scope of this appeal.

THE FINDINGS OF THE DISTRICT COURT

The gravamen of appellees I claim

under section 2 is .thaE minority voters in

the challenged multi-member districts do

not have an equal opportunity to partici-

pate effectively in the political process,

8 The Court did not note probable juris-

diction as to Question II, the question in

the Juripdictional Statement concerning

these two districts, and even the

Solicitor General concedes that there is

no basis for appeal as to these two

district,s. U.S. Br. 11 .

8

a'nd particularly that t'hey do not have an

egual opportunity to elect candidat,es of

their choice. Five of the chal.lenged 1982

multi-member districts were the same as

had existed under the 1971 pIan, and the

one that was different, Eouse District 39,

rras only modified sIightly. The election

results in.those district,s are undisputed.

Until 1972 no black since Reconstruction

had been elected to the legistature from

any of the counties in question. The

election results since 1972 are set. forth

on the table on the opposite page. As

that table indicates, prior to 1982 no

more than 3 of the 32 legislators elected

in any one election in the challenged

districts were black, in 1981, when this

action was filed, five of the seven

districts were rePresented by all white

delegations, and three of the districts

still had never elected a black legisla-

9

tor. The black population of the chal-

Ienged districts ranged from 21.8t to

39.5t. JA 21.

, The district court held on the basis

of this record and its examination of

election results in loca1 offices' that

'It]he overall results achieved to date

.o. are minimal.o JA 39. The court noted

thatl following t,he filing of this action,

the number of successful black legislative

candidates rose sharply. It concluded,

however, that the results of the 1982

election were an aberrat,ion unlikely to

recur again. ft emphasized in particular

that in a number of instances trthe

pendency of this very litigation worked a

one-time advantage for black candidates in

the form of unusuaL organized political

support by white leaders concerned to

forestall single-member districting." JA

39 n.27.

10

The district court identified a

number of distinet practices which Put

black voters at a comparative disadvantage

whe n placed in the six ura jority white

multi-member districts at issue" The

court noted, first, that the proportion of

white voters who ever voted for a black

candidate was extremely low; an average of

81t of white voters did not vote for any

black candidate in primary elections

involving both black and white candidates,

and those whites who did vote for black

candidates ranked them last or next to

last. JA 42. The court noted that'in none

of the 53 races in which blacks ran for

of f ice did a rnajority of whites ever vote

for a black candidate, and the sole

election in which 50t voted for the black

candidate was one in which that candidate

was running unopposed. JA. 43-48. The

district court concluded that this pattern

11

of Polarized voting Put black candidates

at a severe disadvantage in any race

against a white oPPonent'.

The district court also concluded

t,hat bl ack voters were at a comparative

disadvantage because the rate of registra-

tion among eligible bLacks was substan-"

. tially lower than among whites- This

disparity further diminished the ability

of black voters to make common cause with

sufficient numbers of like minded voters

!e bC able tO eleer r.a nri i rrates of the ir

choice. The court found that these

disparities in registration rates were the

Iingering effect of a century of virulent

official hostility towards blacks who

sought to register and vote. The tactics

adopted for the exPress PurPose of

disenfranchising blacks included a polI

tax, a literacy test with a grandfather

clauser 6s well as a number of devices

12

which discouraged registration by assuring

the defeaE of black candidates. JA 25-26.

When the use of the state Iiteracy test

ended after 1970, whites enjoyed a 60.6t

to 44.6t registration advantage over

blacks. Thereafter registration was kept

inaceessible in many places, and a decade

later t,he gaP had narrowed only s1ight1y,

with white registration at 66.7*, and

black registration at 52.7*. JA 26 and

n.lz.

The trial court held that the ability

of black voters to elect candidates of

their choice in majority white districts

was further impaired by the fact 'that

black voters were far poorer, and far more

of ten poorly educated, t'han white voters.

JA 28-31. Some 30t of blacks hgd incomes

below the poverty line, compared to 10t of

whites; conversely, whites were twice as

like1y as blacks to earn over $20r000 a

13

year. Almost a1I blacks over 30 years oId

attended inferior segregated schools. JA

29. The district court concluded that

this lack of income and education made it

difficult for black voters to elect

candidates of their choice. JA 31.. n.23.

The. record on which 'the court relied

included extensive testimony regarding the

difficulty of raising sufficient funds in

the relatively Poor black community to

meet the high cost of an at-1arge cam-

Paign-which hac to rl'ar.h as many as eight I'

.

times as many voters as a single district

campaign. (See notes 107-109r infra).

The ability of minority candidates to

win white votes, the district court found,

was also impaired by the common practice

on the part of white candidates of urging

whit.es to vote on racial lines. JA 33-34.

The record on which the court relied

14

included such appeals in camPaigns in

1976, 1980, 1982, and 1983. (See page 115,

infra). In both 1980 and 1983 white

candidates ran newsPaPer advertlsements

depicting their opPonents with black

leaders. In 1983 Senator Fielms denounced

his opponent for favoring black voter

regist,ration, and in a 1982 eongressional

run-off white voters were urged t'o. go t,o

the polls because the black candidate

would be 'bussing" lsicl his 'block" lsicl

vote. (See PP. 116-18, infra).

The district court, after an exhaus-

tive analysis of this and other evid€DC€2

concluded that the challenged multi-member

districts had the effect' of submerging

black voters as a voting minority in those

districts, and thus affording them "Iess

opportunity than ... other members of the

15

electorate to Participate in the political

process and to elect rePresentatives of

their choice." JA 53-54.9

SUI.iUARY.OF ARGUMENT

Section 2 of the Voting' Rights Act

rras amended i n 1982 to establ ish 'a

nationwide prohibition against election

practices with discrlminatory results.

Specifically prohibited are Practices that

afford minorities "Iess opPortunity than

nt.har mamhorq af thc cl ectorate to

participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choiceo.

(Emphasis added). In assessing a claim of

unequal electoral opportunity, the courts

are required to consider the 'totalit,y of

circumstancesr. A finding of unequal

9 Based on similar evidence the court made a

parallel firding concerning the fracturing

. of the minority community in Senate

District No. 2. iIA 54.

16

opportunity is a faetual finding subject

to Rule 52.

City,

-

U.S.

-

,rt*

The 1982 Senate RePort sPecified a

number of specific factors the Presence of

which, C.ongress believed, would have the

effect, of denying equal electoral oPpor-

tunity to black voters in a majority white

multi-member district. The three-judge

district court below, in an exhaustive and

detailed opinion, carefully analyzed the

evidencb indicating the Presence of each

of those factors. In light of the

totality of circumstances established by

that evidence, t,he trial court concluded

that ninority voters were denied equal

electoral opportunity in each of the six

challenged multi-member districts. The

court below expressly recognized that

section 2 did not require proportional

representation. JA 17.

17

Appellants argue herer BS t,hey did at

t,r ial , that the Presence of equal elec-

toral opportunity is conclusively estab-

lished by the fact blacks won 5 out of 30

at-large seats in 1982, !! months after

the conplaint was filed. Prior to 1972,

howdver, although blacks had run, no

blacks had ever been elected from any of

these districts, and in the eleetion heLd

immediately prior to. t,he commencement of

this action only 2 blacks were elected in

the challenqed districts. The district

court properly declined to hold that the

1982 elections represented a conclusive

change in the circumstances in the

districts involved, noting that in several

instances blacks rron because of support

fron whites seeking to affect the outcome

of the instant litigation. JA 39 n.2'7.

18

The Solicitor General urges this

Court to read into section 2. " PSg se rule

that a section 2 claim is precluded as a

matter of law in any district in which

blacks ever enjoyed 'proportional repre-

sentation" r regardless of whether that

representation ended years 89or was

inextricably tied to single shot voting,

or occurred only after the conmencement of

the l itigation. This .Per E approach is

i nconsistent with t,he "t,otality of

circumstances" requirement of section'2,

which precludes treating any single factor

as conclusive. The Senate RePort ex-

pressly stated that the elect'ion of black

officials was not, to be treated, bY

itself, as precluding a section 2 claim.

Sn Rep. No. 97-417 , 29 n.1.15.

The district court correctlY held

that there was sufficiently severe

polarized voting by whites to put minority

19

voters and candidates at an additional

disadvantage in the majority white

multi-member districts. On the average

more than 81t of whites do not vote for

bLack candidates when they run in primary

eleetions. 'JA 42. Black candidates

. feceiving the highest proportion of black

votes ordinarily receive the smallest

number of white votes. Id.

ARGUI{ENT

r. sEcTroN 2 PRovrDEs MrNoRrrY vorEBs-

AN EOUAL OPPORTT,NITY TO ELECT REPRE-

SENTATIVES OF THEIR CHOICE

iwo decades ago Congress adopted the

Voting Rights Act of 1955 in an attempt to

end a century long exclusion of most

blacks from the electoral Process. In

1981 and 1982 Congress concluded that,

. despite substantial gains in registration

since 1965, ilinorities stil1 did not enjoy

the same opportunlty as whites to Parti-

20

cipate in the political Process and to

elect rePresentatives of their choice'1otnd

that further remedial legislation was

necessary to- eradicate all vestiges of

discrimination from the political pro-

".=".11

The prbblems identified by Congress

included not' only the obvious impedinents

to minoritY ParticiPation, such as

regist.ration barriers, but also election

schemes such as those at-Large elections

which impair exercise of the franchise and

dilute the voting stpe.ngth of minority

citizens. Although some of these practices

had been corrected in certain jurisdic-

tions by oPeration of the preclearance

provisions of Section 5t Congress con-

S. Rep. No. 97-417 | 97th

34 (1982) (hereinafter

Reportn ) .

Senate RePort 40; [I.R.

97th Cong., 1st Sess.,

inafter cited as "House

Cong. , 2d Sess. ,

cited as "Senate

Rep. No. 97-227,

31 (1981) (here-

Report" ) .

10

11

21

cluded that their eradication required the

adoption, in the form of an amendment to

Section 2, of a n3tionall 2prorribition

against practices with discriminatory

results.l3 section 2 protects not only the

:':right to voter but, also {the right to have

the vote counEed at fulI value'without

dilution or discount.i Senate Report 19.

A. Leqislative Historv of the 1982

Amendment to Sectron 2

The present language of section 2 was

adopted by Congress as part of the Voting

Rights Act Amendments of 1982. (95 SEat.

1 31 ) . The 1 982 amendments altered the

Voting Rights Act in a number of ways,

House Report , 28t Senate RePort 1 5.

Appellants and the Solicitor General

concede that the framers of the 1982

amendments established a standard of proof

in vote dilution lawsuits based on

discrininatory results a1one. Appellants I

Br. at 16; U.S. Brief II at 8, 13.

12

13

22

extendlng the pre-clearance requirements

of section 5, modifYing the bailout

requirenents of section 4t continuing

until 1992 the languhge assistance

provisions of the Act, and adding a new

requirenent of assistance to bIind,

disabled or illiterate voters. Congres-

sional action to amend section 2 was

prompted by this Courtts decision in

trlobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 50-61

( 1 980) ' which held that the original

language of section 2, as it was framed in

1965, forebade only election practices

adopted or maintained with a discrirnina-

tory motive. Congress regarded the

decision in Bolden as an erroneous

interpretation of section 2r 1 4and thus

acted to amend the language to remove any

such intent requirement,.

14 House Rep. at 29i Senate Report at 1 9.

23

tegislative proposals to extend the

Voting Rights Act in 1982 included from

the outset language that Would eliminate

the intent requirement of Bolden and apply

a totality of circumstances test to

pracEices which merely had the effect of

discriminating on the basis'of race or'

color.l5 support for such an amendment was

repeatedly voiced during the extensive

Bouse hearings.and mueh of this testimony

rras concerned with at-large election plans

that had the effect of diluting the impact

15

16

of mi nor i ty ,ot.s . 1 5 on Jury 31 the llouse

fl.R. 3112, 97th Cong. , l st Sess. , S 201i

E.R. 3198, 97th Cong., 1st Sess., S 2.

The three voLumes of Hearings before the

Subconmittee on Clvil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Judiciary Committee,

97th Cong., lst Sess., are hereinafter

cited as nHouse Hearings.tr Testimony

regarding the proposed amendnent to

section 2 can be found at 1 Eouse

Hearings 18-19, 138, 197, 229, 355,

424-25, 454, 852i 2 House Hearings 905-07,

993-95, 1279t 1361, 1541; 3 House Hearings

1880, 1991, 2029-32, 2036-37, 2127-28,

2136, 2046-47 , 2051 -58.

24

Judiciary Committee approved a bill that

extended the Voting Rights Act and

included an amendment to section 2 to

remove the intent requirement imposed by

Bo1der,.17 The House version included an

express disclaimer to make clear that the

mere lack of proportional rePresentation

would not constitute a violation of the

1aw, and the Eouse Report directed the

courts not Co focus on any one factor but

17 House Report, 48:

'No voting qualification or Prere-

quisite to votitg, or standard, practice,

dr procedure sfrall be iinposed or applied

by iny state or political subdivision Ito

deny or abridgel !n e M!4g-E- which results

in i lerliar qi a

EnV cltizen to vote on account ot race or

color, or in contravention of the guaran-

tees set forth in section 4(b) (2). The

fact that memberi of a minoritY gr

have not been electecl 1n numDers

sect

e

25-

to look at all the relevant circumstances

in assessing a Section 2 claim. E. Rep.

at 30.

The House Report set forth the

committee I s reasons for disapproving any

intent . requirement,

.

and described a

variety of'practices, particularly the use

of at-large electionslS"rrd limitations on

the times ard plaees of registrationrl9with

whose potentially discriminatory effects

the Conmittee was particularly concerned.

On the floor of the House 66 proposed

amendment to section 2 was the subject of

considerable debate. Representative

Rodino expressly called the attention of

the House to this portion of the bil1r20ao

which he and a number of other speakers

18

19

20

House Report , 1'l-19,

128 Corg. Rec. E 6842

1981).

30.

31 n.1 05.

(daily ed. Oct. 2l

26

gave suPPor E.21 Proponents of, section 2

emphasized its applicability to rnulti-

member election districts that diluted

minority votes, and to burdensome regis-

tration ard voting practic"".22 A number of

speakers opposed the proposed alteration

to sect,ion 2 r23 and Representative Bliley

moved that the amendment to section 2 be

deleted from the Eouse biII. The 81i1ey

21

22

128 Cong. Rec. EI 6842 (ReP. Rodino), H

6843 (Rep. Sensenbrenner) r II 6877 (ReP.

Chisholm) (daify'€d. r Oct. 2, 1981); 128

Cong. Rec. H lOOt (ReP. Fascell) (daily

ed.1 Oct. 5, 1981).

128 Cong. Rec. [I 6841 (ReP. Glickman;

diLutionf, u gge5-5 (Rep. Hydet registra-

tion barriers), H 6847 (ReP. Bingham;

voting practices, dilutign); H 5850 (RgP.

Wash i nlgton, registration and voting

barrierl); B 5851 (ReP. Fish, dilution)

(daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981)-

128 Cong. Rec. EI 5855 (ReP. Collins), E

6874 (nep. Butler)(daily ed-, Oct. 2,

1 981 ); 128 Cong. Rec. H 6982-3 (ReP.

BliIey) , H 6984 (ReP. Butler, (ReP.

r.lcClory), H 6985 (ReP. But1er) (daiIy ed. r

Oct. 5, 1981 ).

23

27

amendment was defeated on a voice ,ote.24

Following the rejection of that and other

amendments the House on October 5, 1981

passed the bill by a margin of 389 to 24.25

On December 16, 1981 , a Sena-te bill

essentially identical to the gouie passed

bi 1f was i ntroduced by Se.nator t{athias.

The Senate bi1I, S.1992, had a total of 61

initial sponsors, far more than were

necessary to assure passage. 2 Senate

Hearings 4, 30, 157. The particular

subcommittee to which S.1992 was referred,

however, was dominated by Senators who

were highly criticaL of the Voting Rights

Act amendments. After extensive hear-

128 Corg. Rec.

5,1981).

!|. at H6985.

H 5982-85 (daily ed., Oct.24

25

28

ingsr26.o=a of them devoted to section 2l

the subcommittee recommended Passage of

5.1992, but by a margin of 3-2 voted to

delete the proposed amendment to section

2 " 2 Se nate Heari ngs 1 0. In ,the f uII

committee Senator Dole proposed language

which largely restored the substance of S"

1gg2; included in the DoIe proposal was

the language of section 2 as it was

ultimately adopted. The Senate Cornmmittee

issued a Iengt,hy rePort describing in

detail the PurPose and impact of the

seetion 2 amendmenE. Senate Report 15-42.

The report'expressed concern with two

distinct types of practices with poten-

rial1y discriminatorY effects--first,

restrictions on the times, places or

25 rd. ttearings before the Subcommitee on

ffi-e Constitution of the Senate Judiciary

Comrnittee on S. 53, 97th Cong - , 2d Sess.

( 1 982) (hereinafter cited as "Senate

Hearings') .

29

methods of registration or voting, the

burden of which would fall most heavily on

mirpriti es r27 drrd, secgnd, election syst,ems

such as those multi-member districts which

reduced or nullified the effectiveness of

minority votes, and impeded the ability of

' minority voters to elect candidates' of

their choice.28 The Senate debates leading

to approval of the section 2 amendment

reflected similar

"on""rn=.29

The Senate report discussed the

various types of evidence that would bear

on a section 2 c1aim, and insisted that

the courts were to consider all of this

evidence and that no one type of evidence

27 Senate Report, 30 n.119.

28 Senate Report | 27-30.

29 128 Corg. Rec. S 5783 (daily ed. June 15,

1982) (Sen. Dodd); 128 Cong. Rec. S 7111

(daiIy ed. June 18, 1982) (Sen. Met-

zenbaum), S7113 (Sen. Bentsen), S 7116

(Sen. Weicker), S 7137 (Sen. Robert

Byrd).

30

should be treated as conclusio'"'30 Both the.

Senate RePort and the subsequent debates

make clear that it' was the intent of

Congress, in aPplying the amended sect'ion

2 to multi-member districts, to reestab-

lish what it understood to be the totality

of circumstances test that had been estab-

lished by White v.Regester, 412 U'S' 755

(19731r3land that had been elaborated upon

by the lower courts in the years between

White and Bolden.32 The most important and

frequently eited of the courts of appeals

dilution cases was Zimmer v. t'lcKeithen,33

Senate RePort, 2?, 27 -

Senate RePort, 2t 27, 28, 30, 32'

Senate RePort , 16, 23, 23 n.78, 28, 30,

31, 32"

Ziruner was described by t'he Senate Report

a5-f seminal" decision, id. at 22, and

was cited 9 tines in the R-port' !|' at

22, 24, 24 n.85, 28 n.112, 28 n'1T3, 29

n.i I 5r- 29 n.1 15, 30, 32, 33. senator

oeConcini, one of the framers of the DoIe

pioposaf , described Llmmer as " lPl-erh-aps

the clearest exPressiffithe standard of

30

31

32

33

31

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)(en banc)r

aff rd sub Dorn. East CarroII Parish School

Board v. ltarshall, 424 U. S. 635 ( 1975 ) .

The decisions applying White are an

important source of guidance in a section

2'dilu.tion case.

'The legislative history of section 2

focused repeatedly on the possibly

discriminatory irnpact of multl-member

districts. Congress was specifically

concerned that, if there is voting along

raoial lines- hlaok rz.rtFl" in A maioril.w

white multi-member district would be

unable to compeEe on an equal basis with

whites for a role in electing public

officials. Where that occurs, the white

majority is able to det,ermine the outcome

of elections and white eandidates are able

proof in these vote

Cong. Rec. S5930

1 982) .

dilution cases. n

(dai1y ed. June

128

17,

32

to take positions without regard to the

votes or preferences of black voters,

rendering the act of voting for blacks an

empty and ineffective ritual- The Senate

Report described in detail the types of

eircumstances, based on the whiEe/zimmer

factors, under which blacks in a muLti-

member district would be less able than

whites to elect representatives of their

choice. Senate RePort, 28-29.

The Solicitor General, in support of

his contention that a section 2 claim may

be decided on the basis of a single one of

the seven Senate Report factors--electoral

success--regardless of the totality of the

circumstances, offers an account of the

legislative history of section 2 which is,

in a number of respects, substantially

inaccurate. First, the Solicitor asserts

that, when the amended version of S- 1992

was reported to the ful1 JudiciarY

33

Committee, there was a "deadlock." U.S.

Br. I, 8; Br. II, I n.12. The legislative

situation on ltay 4, 1982 when the Dole

proposal was offered, could not conceiv-

ably be characterized as a ideadlock, " and

was never so described by ahy-supporter of

the proposal. The entire Judiciary

Commi ttee f avored retrrcrting out a bill

amending the Voting Rights Act, and fu1ly

two thirds of the Senate vras committea to

restoring the'tlouse results test if the

Jud ic iar Committee failed to do so.

Critics of the original S.1 992 had neither

the desire nor the votes to bottle up the

bill in Committeer34"rrd clearly lacked the

votes to defeat the section 2 amendment on

the floor of the Senate. The leading

34 2 SenaEe Hearings

( " [W] hatever happens

amerdment, I intend to

reportirT, of t,he Voting

Committeer )

69 (Sen. Hatch)

to the proposed

support favorable

Rights Act by this

34

Senate oPponent of the amendment acknowl-

edged that Passage of the amendment had

been foreseeable rfor many months' prior

to the fuI1 Conmitt,ee's action.35 Senator

Dole commented, when he offered his

proposal, that "without any change the

House bill would have passed. " 2 Senat'e

Hearings 57. Both supportet"36""d oPPo-

nents3Tof section 2 alike agreed that the

35 2 Senate Hearings 69 (Sen- Batch).

35 Senate Retrrcrt, 27 (section 2 "faithful to

the basil intento of the llouse bill); 2

Senate Hearings 50 (Sen. DoIe)("[T]he

conpronise retains the results standards

of the trtathias/Kennedy bi11. llowever, we

also feel that the legislation should be

strenqt,hened with additional language

mhat Iegal standard should

aPPly urder the results test...o) (EmPha-

sTs - added) , 51 (Sen. Dole) (language

"strergthens the tlouse-passed bi11") 58

(Sen. 6iOen)(new Language merely 'cIari-

iies" s.1992 and "does not change muchi),

128 Cong. Rec. S6950-61 (daily ed' June

17, 1962) (Sen. DoIe); 128 Cong. Rec'

83840 (daily ed. June 23, 1982) (ReP'

Edwards).

37 2 Senate Hearings 70 (Sen. Hatch).("The

proPosed compromise is not a comPromise at

ifi, in ny oPinion. The imPact of the

35 -

language proposed by Senator Dole ard

u I t irnately adopted by Congress was

intended not to water down the original

House biIl, but merely to spelI out more

explicitly the intended meaning of

legislation

Horse.38

already approved bY the

The Solicitor urges the Court to give

litt1e weight to the Senate RePort

accompanying S.1 992, describing it as

proposed compromise is not .Iikely to-be

one whit different than the unamended

House measure" relating t,o seet'ion 2i

Senate Report, 95 (additional views of

Sen. Eatch); 128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed.

June 9r 1982) S 6515' S.6545 (Sen. Hatch);

128 Cong. Rec. (daily ed. June 10, 1982) S

6725 (Sen. East); 128 Cong. Rec. (daily

ed.7 June 15, 1982) S.5786 (Sen. Harry

Byrd).

38 The compromise language was designed to

reassure Senate cosPonsors that the White

v. Regester totar itt of circumstances-TE5E

e ntlffitl- i n the House , a nd esPoused

throughout the Senate hearings by sup-

porters of the Eouse passed bill, would be

codified in the st,atute itself . 2 Senate

Eearings 60; Senat,e RePort , 27 .

-35

nerel y t,he work of a .f action. U. S. . Br . I ,

8 n.6i U.Sn Br. TI, 8 n.12, 24 n.49"

Not,hi ng i n the legislative history of

section 2 supports the Solicitorrs

suggestion that this Court should depart

from the long establ,ished principle t,hat

committee reports are to be treated as the

most authoritative guide to congressional

intent. Garcia v. United States, 105

S.Ct. 479, 483 (1984). Senator DoIe, to

whose position the Solicitor would give

particular weight, pr'efaced his Additional

Views with an acknowledgement t,hat " [T]he

Committee Report is an accurate statement

of the inteht of s.1992r ds reported by

the committee."39 on the floor of the

Senate both supporters and opponents of

39 Senate Report 193; see also id. at 195 ("I

express my views not to tat-e issue with

the body of the reporti) 199 ("I concur

with the interpretation of this action in

the Committee Report."), 196-98 (addi-

tional views of Sen. GrassleY).

37

section 2 agreed that the Committee report

constituted the authoritative explanation

of the legislatiorr.40 until the filing of

its briefs in this case, it was the

consistent contention of the Department of

Justice that in interpreting section 2

i It,] he Senate .Report... is' entitled to

greater weight than any other of the

legislative history."4l only in the spring

of' 1 985 did the Department reverse its

position and adsert that the Senate report

faction that

40 128 Corg. Rec. 56553 (daily ed.7 June 9l

1982) (Sen. Kennbdy) ; S6546-48 (dai1y ed.

June 10, 1982) (Sen. Kennedy); 56781 (Sen.

Dole)(daily ed. June 15, 19821i 55930-34

(Sen. DeConcini) r S5941-44, 56967 (Sen.

Irtathias), S6950, 6993 (Sen. Dole), s5967

S5991 -93 (Sen. Stevens) r S5995 (Sen.

Kennedy) (daily ed. June 17, 19821 i

57091-92 (Sen. Hatch), 57095-96 (Sen.

Kennedy) (daily ed.7 June 1 8, 1 982) .

Post-ltiat erief for the United States of

Anrerica, County Council of Sumter County,

South Carolina v. United States, No.

41

38

"cannot be taken as determinative on all

counts." U.S. Br. l, P. 24, n"49" This

newly formulated account of the legisla-

tive history of section 2 is clearly

incorrect.

The Solicitor urges that substairtial

weight be given to the views of Senator

Hatch ,42 ^rd

hi.s legislative assistant.43 rn

fact, however, Senator Batch was the most

intransigient congressional critic of

amended section 2, and he did not as the

42 In an amicus brief in City Council of the

City of Chicago v. KetEhumi--No.

i-FEieilin this case,

U.S. Br. TI 21 n.43, the Solicitor asserts

that Senator Eatch "supported the com-

promise adopted by Congress"" Brief for

United States as Amicus , 15 n.1 5.

43 The solicitor cit,es for a supposedly

authoritative summary of the origin and

meaning of section 2 an article written by

Stephen Markman. U.S. Br. Ifr 9r 10.

Mr. t{arkman is the chief counsel of the

Judiciary Subcommittee chaired by Senator

Hatch, and $ras Senator Hatch I s chief

assistant in llatch I s unsuccessful opposi-

tion to the amendnent to section 2.

39

Solicitor suggests support Lhe Dole

proposal. On the contrary, Senator Eatch

urged the Judiciary Committee to reject

the DoIe ProPosal ,44and vras one of only

four Committee members to vote against,

it.45 FoIlowing the Committeers action,

Senator Hatch appended to the Senate

Report Additional Views objecting to this

nodified version of section 2-46 on the

floor of the Senate, S€nator Hatch

supported an unsuceessful amendment that

'-'a.r1A h.rua e{-rtrr.le frorn the bill the

amendme nt

adopted

de nou nced

to section 2 that had been

by the committe" r

4T.rrd again

the language which eventuallY

44 2 senate tlearings 70-74.

45 Jg. B5-8G.

46 Senate Report, 94-101.

47 128 Cong. Rec. s5965 (daily ed. June 17,

1 982) .

40

became Iar.48

Finally, t,he Solicitor urges that the

views of the President regarding section 2

should be given 'particular weighti

because the President endorsed the DoIe

proposal, and his 'support for the

compromise ensured its passage.t U.S. Br.

I, I n.5. we agree with the Solicitor

General that the construction of section 2

which the Department of Justice now

proposes in its amicus brief should be

considered in light of the role which the

Administration played in the adoption of

this legislation. But that role is'rot,

as the Solicitor asserts, one of a key

sponsor of the legislation, without whose

48 Inunediately prior to the f inal vote on the

bi11, Senator Hatch stated , ' these

amerdments promise to effect a destructive

transformation in the Voting Rights Act."

128 Cong. Rec. S7139 (daily ed. June 18,

19821 i 'l 28 Cong . Rec. ( daily ed . June 9 |

1982) 56506-21.

41

support the bill could not have been

adopted. On the contrary, the Adninis-

tration in general, and the Department of

Justice in particular, were throughout the

legislative process among the most consis-

tent, adamant and outspoken opponents of

t,he proposed Amendment to section 2.

Shortly after the Passage of the

House bi11, the Administration launched a

concerted attack on the decision of the

Eouse to amend section 2. On November 6,

statement

denouncing the 'new and untested reffectsr

standard, " and urging that section 2 be

limited to instances of purposeful

discrimination, 2 Senate tlearings 763,

a position Mr. Reagan strongly reaffirmed

at a press conference on December 17.49

When in January 1982 the Senate commenced

49 New

coI.

York Times, Dee. 18, 1981, P. B7,

4.

42

hearings on proposed amendments to the

Voting Rights Act, the Attorney General

appeared as the first wit,ness to denounce

section 2 as "just bad J.egislationr'

objecting in part,icular to any proposal to

apply a results standard to any state not

covered by section 5. 1 Senate Hearings

7 0-97 . At the close of the Senate

Bearings in early March the Assistant

Attorney General for Civil Rights gave

extensive testiinony in opposition to the

adoption of the totalit,y of circumstances/

results test. I9.r dt 1655 et seq. Both

Justice Department officials made an

effort to soLicit public opposition to the

results test, publishing critical analyses

in several national nevtspapet"So"rrd, in the

50 2 Senate Hearings 770 (Assistant At-

torney General Reynolds) (Washington

Post), 774 (Attorney General Smith) (

Op-ed articler New York Times), 775

(Attorrrey General Smith) ( Op-ed article,

Washington Post).

43

case of the Attorney General, issuing a

warning to members of the United Jewish

Appea1 that adoption of a results test

would lead to court ordered racial quo-

tas.51 The white House did not endorse the

DoIe proposal until after it had the

support of 13 of the'18'members of the

Judiciary Committee and Senator DoIe had

warned pubLicly that he had the votes

'2necessary to override anY veto.'

Eaving failed to persuade Congress to

reiect - resrr'l ts standard in sectiolr 2r I

the Department of Justice now seeks to

persuade t,his court to adopt an interpre-

tation of section 2 that would severely

limit the scope of that provision. Under

these unusual circumstances the Depart-

51

52

E. qt 780.

Los Arrgeles Times, l,lay

Street Journal, MaY

Senate Hearings 58.

4t 1982, p. 1; WalI

4t 1982r P. 8; 2

44

mentrs views do not appear t,o warrant the

weight that might ordinarily be appro-

priate. We believe that greater deference

should be given to the views expressed in

an ami.cus brief .in this case by Senator

Dole and the other principal co'sponsors of

section 2.

B. Equal Electoral Opportunity is.

Section 2 provides that a claim of

unlawful vote dilution is established Lf,

"based on the totality of circumstances, "

members of a racial minority ohave less

opportunity than other members to partici-

pate in the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice.'53 rn the

instant case the district court concluded

that minority voters lacked such an equal

opportunity. JA 53-54.

53 42 u.s.c. s

forth in the

1973, Section 2(b) is set

opinion below, JA 13.

45

Both aPPellants and the Solicitor

General suggest, however, that section 2

is lirnited to those ext,reme cases in which

the effect of an at-Iarge eleetion is to

render virtually impossible t'he election

of public officials, black or otherwise,

favored by minority voters. Thus appel-

lants assert that section 2 forbids use of

a multi-member district when it "effec-

tively locks the racial ninority out of

the Political forumr " A. Br. 44, or

ishuts[s] racial rninorities out of the

electoral process" }|. at 23- The Soli-

citor invites the Court to hold that

.section 2 applies only where minorlty

candidates are "effectively shut out of

the political process". U.S. Br. II 27i

see also i9. at 11. On this view, the

election of even a single black candidate

would be fatal to a section 2 c1aim.

46

The requirements of section 2,

however, are not met by an election scheme

which merely aecords to minorities some

minimal opportunity to participate in the

political Proeess. Section 2 requires

t,hat "the political Processes leading to

nomination or eLection' be, not merely

open to minority voters and candidates,

but 'ggg*. open". (Emphasis added) " The

prohibition of section 2 is not linited to

those systems which provide minoriLies

with no access whatever to the political

process, but extends to systems which

afford minorities '1ess opportunity than

other members of the electorate to

participate in the political Process and

to elect representaEives of their choice."

(Ernphasis added) .

This emphasis on equality of opportu-

nity was reiterated throughout the

legislative history of section 2. The

47

Senate rePort insisted repeatedly that

section 2 reguired equality of political

opportuni ty. 54 Senator Dole, in. his

54 S. Rep. 97-417, p. 15 ("equal chance to

BH::i'$::"3".o'l"n."'"i::?:?lrn'.""""???li

20 ('equa1 access to the Pollqi-"?1

process;; at-large elections invalid"if

ifrey give rninoriLies "Iess oPPof tunity

tnair .-.. other residents to participate in

the political processes and to elect

legi6lators of their choice"l, 21 (Plain-

tiifs must Prove they ihad less opportu-

nit,y than did other r.esidents in the

disfrict to participate'in the political

Processes and to elect legislators of

tneir choice") , 27 (denial of "equa1

accesc to the Fo'l i t i eal ProceSSil , 28

(minority voters to have rthe same

opportunity to participate.in the politi-

ci1 procesi as other citizens enjoy";

minority voters entitled to 'an equal

opportunitY to ParticiPate in the

p6iitcaf processes and to elect candi--ilates of their choiceo ) , 30 ( "denial of

equal access to any phase of the electoral

pioc.ss for minorily votersi; standard is

ilhether a challenged practice "operated

to deny the minority plaintiff an equal

opportunity to participate and elect

canaiaates of their choice" i Process must

be "equalIy open to participation PV tlr:

group in question'), 31 (remedy .shouldIssure "equa1 opportunity for minority

citizens to participate and t,o elect

candidates of their choice') .

48

Additional Views, endorsed the committee

reportr and reiterated that under the

language of section 2 minority voters were

to be given "the same opportunity as

others to participate in the political

process and to elecE, the candidates of

their cho1."".55 Senator DoIe and others

repeatedly nade this point on the floor of

the senate.56

The standard announced in White v.

Regestei das clearly one of equal oppor-

tunity, prohibiting at-large elections

which afford minority voters 'less

opportunity than o.. other residents in

Id. at 194 (emphasis onitted); See also

iA. at 1 93 ( "Citizens of all rfE6s-58

Ei'titled to have an equal chance of

electing candidates of their choice. . . . ') 7

194 ("equal aceess to the political

process).

128 Cong. Rec. S6559, S5560 (Sen.

Kennedy)(daily ed. June 9, 1982)i daily

ed. June 17, 1982)i 128 Cong. Rec.

57119-20 (Sen. DoIe), (dai1y ed. June 18,

1 e82) .

55

55

49

the district to ParticiPate in the

political Processes and to elect legisla-

tors of their choic€.r 412 U.s. it 765.

(Emphasis added). The Solicitor General

asserts that during the Senate hearings

three suPPorters qf section 2 described it

as ]merelY a means of ensuring that

minorities were not effectively tshut outt

of the electoral process". U.S. Br. II,

1 1 . This is not an accurate description

of 'the testimony cited by the Solicito''57

L''

57 David Walbert stated that minority

voters had had "no chance" to win elec-

tions . in their earlier successful

dilution cases, 1 Senate Hearings 626,

but also noted that the standard under

White was whether minority voters had an

f,6{'Ea-a1 opportunity" to do so. rd. senator

Keinedy-ltated inat under -ilection 2

minori{ies could not, be "effectively shut

out of a fair oPportunity t'o participate

in the ele: ion". Id. aE 223. Clear1y a

"fair" opportunitflis more than aly

minimal opportunity. Armand Derfner did

use the wo-rds "shut out', but not, as the

Solicitor does, followed by the clause 'of

the political process" . Id. at 81 0. I{ore

impoitantly, both in his-oral statement

(id. at 796, , 800) and his PrePared

sFatement (id. at 811, 818) t'tr. Derf ner

50

Even if it were, the remarks of three

witnesses would carry no weight where they

conflict with the express language of the

bi11, the committee report, and the

consistent statements of supporters. Ernst

and Ernst v. Eochfelder, 425 U.S. 185, 204

n.24 (1975).

C. The Election of Some Minority

r

The central argument advanced by the

Solicitor General and the appellants is

that the election of a black candidate in

a multi-member di.strict conclusively

establishes the absence of a section 2

violation. The Solicitor asserts, U S"

Br. I 13-14, that it is not sufficient

that there is underrepresentation now t ot

expressly endorsed the equal opportunity

standard.

!

51

that there was underrepresentation for a

century prior to the filing of the action;

on the Solicitorrs view there must at all

times have been underrepresentation. Thus

the Solicitor insists there is no vote

dilution in Senate Distr LcE'22, whieh has

not elected a black since 1978, and 'that

there can be no vote dilution in House

District 36, becauser of eight rePresen-

tatives, a single black, the first this

century, was elected there in 1982 after

this lit,iqation was filed.

This interpretation of section 2 is

plainly inconsistent with t,he language and

legislative history of the statute.

Section 2(b) directs the courts to

consider ithe totality of circumstancesr"

an admonition which necessarily precludes

giving conclusive weight to any single

circumstance.5S The "totality of circum-

58 rhe Solicitorrs argumenE also flies in the

52

stancesi standard was taken from White v.

Regester, which Congress intended to

codify in section 2. The llouse and Senate

reports both emphasize the importance of

considering the totality of circumstances,

rather than focusing on only one or two

portions of .the reeord. Senate Report 27,

34-35; Eouse Report, 30. The Senate

Report sets out a number of "[tlypica]"

factors to be considered in a dilution

".".r59 of which nthe extent to which

membe'rs of the minority grouP have been

face of t,he language of section 2 which

disdvows any intent to establish proPor-

t,ional representation. On the Solicitor I s

view, even if there is in fact a denial of

equal opportunity, blacks cannot prevail

in a section 2 action if they have t ot

have ever had, proportional representa-

tion. Thus proportional rePresentation,

spurned by Congress as a measure of

liability, would be resurrected by the

Solicitor General as a type of affirmative

defense.

The factors are set out in the opinion

below. JA 15.

59

53

elected to public office in the juris-

diction' is only orl€ I and admonishes

'there is no requirement that any Partic-

ular nurnber of f actors be proved, or that'

a majority of then point one way or the

other. n Senate Report 28-29..60 Senator

'DoIe, in his additional views accomPanying

the committee report, makes this p1ain.

'The extent to which members of a Pro-

tected class havlbeen elected under the

challenged practice or structure is just'

6na f ar:t-or. amono the totality of circum-

\)

stances to be considered, and is not

9j:!Slj;!ve.n }|. at 194. (EmPhasis

added).61

50 See also Senate Report 23 ('not every one

of the factors needs to be proved in order

to obtain relief" ) .

128 Cong. Rec. S6951 (daily ed- June_l7,

1982) (Sen. Dole); 128 Cong. Rec. S7119

(daily ed. June 18, 1982) (Sen. DoIe).

61

54

The argumenE,s of appellants and the

Solicitor General that any minority

electoral success should f orecl.ose a

section 2 claim rrere expressly addressed

and rejected by Congress. The Senate

Report explains, 'the election of a few

minority candidates does not tnecessarily

foreclose the possibility of dilution of

the black vote. '' Id. at 29 n.l 1 5. Both

White v. Regester and it,s progeny, as

Congress 'weIl knerd, had repeatedly

disapproved the contention now advanced by

appellants and the so1icitor.62 In white

itself, as the Senate Report noa"il

total of two blacks and five hispanics had

62 "The results test, codified by the

committee bill, is a well-established

on€r familiar to the eourts. It has a

reliable and reassuring track record,

which completely belies claims that it

woulcl make ProPort1.onal representata-

t10n tne stanclarcl tor avolcllnq a vt-o-

ong. Rec.

I

asI.s

56559 (Sen. Kennedy) (daily ed. June 9,

1982).

55

been eleeted from the two multi-member

districts invalidated in that case. Senate

Report 22. Zimmer v. McKeithenr in a

passage quoted by the Senate Report, had

refused to treat "a minority candidate I s

success at the polLs [als conclusit.." 19.

at 29 n.l15. The decision i. llgmer i=

particularly important because in that

case the court ruled for the plaintiffs

despite the fact that blacks had won

twci-thirds of the seats in the most recent

0

dissenters in Zimmer unsuceessfully made

the same argument now advanced by appel-

lants and the Solicitor, insisting'the

election of three black candidates . ..

pretty well explodes any notion that black

voting st,rength has been cancelled or

minimized'. 485 F.2d at 1310 (Coleman,

J., dissenting). A number of other

lower court cases implementing White had

63

56

also refused to attach concLusive weight

to the election of one or more minority

candidates. 63

There dE€r as Congress anticipated, a

variety of .circumstances under which the

election of one or moie minority can-

didates might occur despite an absence of

Kirksey v" Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d

Cross v"

Baxter, 604 F.2d 875, 880 i.7 t EEfTtEfr

eT;--I 9791; united states v. Board of

Supervisors o

allace V.

House, 515 F.2d 619, 523 n"2-T5Effi

Tt75I. See also Seriator Hollings'

@mtrents on the district court decision in

MeCain v. Lybrand, No. 74-281 (D.S.C.

eEI-TZ,-19EffiTTnding a voting rlghts

violation despite some black participation

on the school board and ot,her bodies . 128

Cong. Ree. S5855-55 (daily ed. June 15,

1975). In post-1982 section 2 cases, the

courts have also rejected the contention

that, the statute only applies where

mirprities are completely shut out. See

€.9. r United States v. Marengo CouE

G-nunission 3l t,eiilTfFil) , cert. denied,

(1984); velas@ vffioi

F.2d ror7iffisEE'ffiTg

105 S.Ct. 375

Abilene, 725

>t

the equal electoral opportunity required

by the statute. A minority candidate

might simply be unopposed in a primary or

general election, or be seeking election

in a race in which there were fewer white

candidates than there were positions to be

fi1led.54 white officials or PoIit'ical

54 rne Solicitor General suggests t'hat the

very fact that a black candidate is

unolposed conclusively demonstrates that

the-Landidate or his or her supporters

rrere simply unbeatable. U. S. . Br. II, 22

n.46, 33.- But the number of white

pot,ential candidates who choose to enter a

pariicuiir at-targe race may well be the

res

tions entirely unrelated to the circum-

stances of anY ninoritY candidate

Evidence that whlte potent'ial candidates

were deterred by the perceived strength of

a minority candidate might be relevant

rebuttal evidence in a section 2 action,

but here aPPeIlants offered no such

evidence to-explain the absence of a

sufficient number of white candidates to

contest all the at-large seats. l{ore-

over, in other cases, t,he Department- of

.ilustice has urged courts to find a

violationof section 2 notwithstanding the

election of a black candidate running

unopposed. See United-tlgtes v. Marengo

coulitv commiss

ffiindings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law for the United States,

I

58

leaders, concerned about a pending or

threatened section 2 action, night

engiDeer the election of one or more

minority candidates for the PurPose of

preventing the imposition of single member

districts.65 The mere fact that minorit,y

candidates.were elected would not mean

that those successful candidates were the

representatives preferred by ninority

filed June 21, 1985r P. 8.

55 Ziilmer v. McKeithenr 485 F.2d at 1307:

"Such success night, onoccasion, be

attributable to the work of poli-

ticians, who, apprehending that the

support of a black candidate would

be politically expedient, campaign

to insure his election. Or such

success might be attributable to

political support motivated by

d i f fere nt co ns ideratio ns--namely

that election of a black candidate

will thwart successful challenges to

electoral schemes on dilution

grounds. In either situationr a

candidate could be elected despite

the relative po1 i t ical backward ness

of black residents in the electoral

district. "

I

59 '-

voters. The successful minority candi-

dates might have been the choice, as in

White v. Regesler, 412 U.S. at 755i Senate

Report, 22, of a white political organiza-

tion, or night have been able to win and

retain office only by siding with the

white community onr oE avoiding entirely,

those issues about which whites and

non-whites disagreed. Even where minority

voters and candidates face severe inequal-

ity in opportunity, t,here will occasion-

a1lv be minoritv candidates able to

t

overcome those obstacles because of

exceptional ability or oa 'stroke of luckr

which is not likely to be repeated....'65

The election of a black candidate may

also be the result of "single shootiDg",

which deprives minority voters of any vote

at all in every at-Iarge election but one.

66 wallace v. House,

( 5th Cir. 1 975) .

515 F.2d 619, 623 n.2

60

In multi-member elections for the North

Carolina General Assembly where there are

no numbered seats, voters may typically

vote for as many candidates as there are

vacancies. Votes which they cast for their

second or third favorite candidates,

howeverr rnay result in the victory of that

candidaEe over the votersr first choice.57

Where voting is along racial lines, the

only way minority voters may have to give

preferred candidates a serious chance of

victory is to cast only one of t'heir

ballotsr oE "single shootrr and relinquish

any opportunity at all to influence the

57 this is especially true in North Carolina

where, because of the multiseat electoral

system, a candidate may need votes from

more than 50t of the voters to win. For

example, in the Forsyth Senate primary in

1980, there were 3 candidates for 2 seats.

If the votes rrere spread evenly and all

voters voted a fuIl slate, each candidate

would get votes fuom 2/3 or 67$ of the

voters. In such circumstances it would

take votes from more than 57t of the

voters to win. N.C.G.S. 163.111 (a) ( 2) .

3

61

election of the other at-large officials-58

Where single shot voting is necessary

to elect a black candidate, black voters

are forced to limit their franchise in

order to compete at all in the politicaL

process. This is the functional equiva-

lent of a' rule which pernitted white

voters to cast five ba1lot,s for five

at-large seats, but required black voters

to abnegate four of those ballots in order

to cast one ballot for a black candidate.

*

58 For examPle, in 1978, in Durham County,

99t of the black voters voted for no one

but the black candidate, who vron. JA Ex-

Vol. I Ex. 8. In Wake CountY in 1978,

approximately 808 of the black voters

supported the black candidate, but

because not enough of them single shot

voted the black candidate lost. The next

year, after substantially more black

voters concentrated their votes on the

black candidate, forfeiting their right to

vote a full slate, the first black was

elected. Similarly in Forsyth County when

black voters voted a full slate in 1980,

the black candidate lost. It was only

after many black voters declined to vote

for any white candidates that black

candidates were elected in 1982. Id.

62

Black voters may have had some opportunity

to elect one representative of their

choice, but they had no oPPortunitY

whatever to elect or influence the

election of any of the other rePresenta-

tives.59 Even where.the election of one or

more blacks suggests t,he possible exis-

tence of some electoral opportunities for

minorities, the issue of whet,her those

opportunities are the same as the oPpor-

59 there is no support'for appellants' claim

that white candidates need black support

to win at-large. Black votes were not

inportant for successful white can-

didates. Because of the necessity of

single shot voting, in most instances

black voters rrere unable to affect the

outcome of other than Ehe races of the few

bl acks who tdon. For examPle, white

cardidates in Durham were successful with

only 58 of the votes cast by blacks in

1978 and 1982r in Forsyth' white can-

didaLes in 1980 who received less than 2t

of the black vote were successful, and in

Mecklenburg in 1982, the leading white

senate eandidate won the general

election although only 5t of black voters

voted for him. Id. See, JA 244.

*

63

tunities afforded to whites can onl'y be

resolved by a distinct,Iy 1ocal aPPraisal

of aLI other relevant evidence.

These comPlex Possibilities make

clear the wisdom of Congress in requiring

that a court hearing' a secEion 2 cliim.'

must cons ider 'the totaL i ty o'f circum-

stancesr' rather than only considering the

extent to which minority voters haver oE

have not, been underrepresented in one or

more years. Congress neither deemed

r-6no]rrsive the eleetion of minoritv can-

a

didates, nor directed that such vie-

tories be ignored.T0 The language and

legislative history of section 2 recognize

the potential significance of the election

70 As in other areas of civil rights, the

results test in section 2 no more requires

proof t,hat no blacks ever win elections

than the effect rule in Tit1e VII requires

that no blacks can ever Pass a particular

non-job related test. See Connecticut

v. r6a1 | 457 U.s. 440 (1982)-

64

of minority candidates, but require that