NEA Congratulatory Pamphlet to Bozeman

Working File

February 5, 1977

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. NEA Congratulatory Pamphlet to Bozeman, 1977. 28878c11-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/33d3c9f0-2495-4381-8544-7128ef6d92e5/nea-congratulatory-pamphlet-to-bozeman. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

For your information, read 3 of Joe Reedts columns, From Where I Sit. They are wor.l[-

while readings for every teacher.' You can find them in AEA Journals: (1) December 1, 1gZ6;

(2) March L,1977; (3) May l, L977,

You may also want to look for Dr. Paul Hubbertts message to the Representative Assem-

b1y December 9, 10, 11, 1976; Past President, Earl Barrettts rnessage to the AEA Coavention,

March, 1977; AEA President, Catherine Whiteheadts column, May L, L977, AEA Journal.

DATES 1. NEA Convention - Juty 1--6, 7977, Minneapolis, Minn.

2. Alabama conference on the observanceof international womenrs year -

Saturday, July 9, L977 - Montgomery Civic Center, Montgomery, Alabama

You are invited to attend.

Join the Local and State NEA

Local, State and National NAACP

Local and State Democratic Conference

Box T

Aliceville, Alabama

February 5, L977

M. T. B. Woodard

Pickens County Board of Education

Carrollton, Alabama

Dear Sir:

This is to express our appreciation to the Pickens County Board of Education for

granting the teachers planning time within the school day. We feel that this action will

achieve a better instructional program for the schildren we teach.

We hope that this kind of communication will continue so that together we can build a

better school system within the State.

We hope that future communication will focus heavily on cooperation and harmony in

this educational struggle.

Sincerely yours,

fi*

Classroom Teacher

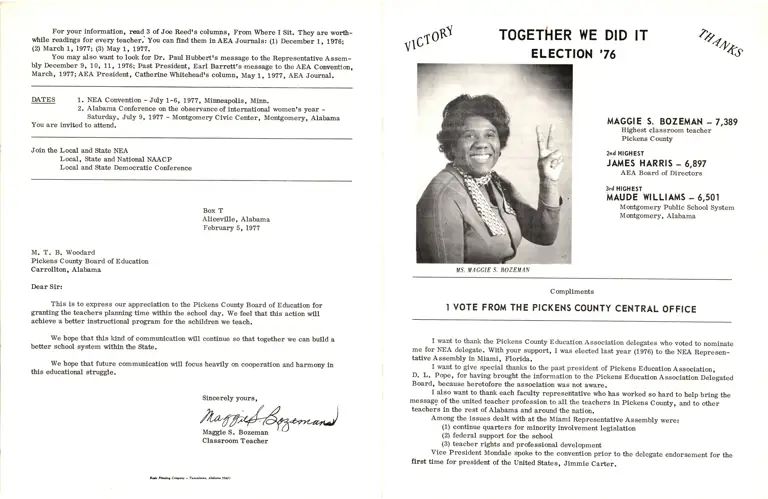

vlc10B1

W

}{E DID ITTOGETHER Qr*.f"

ELECTION '76

MAGGIE S. BOZEMAN _ 7,389

Highest classroom teacher

Pickens County

2nd HIGHEST

JAMES HARRIS - 6,897

AEA Board of Directors

3rd HIGHEST

MAUDE WILLIAMS - 6,50I

Montgomery Public School System

Montgomery, Alabama

Compliments

I VOTE FROM THE PICKENS COUNTY CENTRAL OFFICE

I want to thank the Pickens County Education Association delegates who voted to nominate

me for NEA delegate. With your support, I was elected last year (19?6) to the NEA Represen-

tative Assembly in Miami, Florida.

I want to give special thanks to the past president of Pickens Education Association,

D. L. Pope, for having brought the information to the Pickens Education Association Delegated

Board, because heretofore the association was not aware.

I also want to thank each facult5r represeritative who has worked so hard to help bring the

mess,age of the united teacher profession to all the teachers in Pickens County, and to other

teachers in the rest of Alabama and arorurd the nation.

Among the issues dealt with at the Miami Representative Assembly were:

(1) continue quarters for minority involvement legislation

(2) federal support for the school

(3) teacher rights and professional development

Vice President Mondale spoke to the convention prior to the delegate endorsement for the

first time for president of the united states, Jimmie carter.

T4S. ilIACGIE S. BOZET|AN

Jdt tut Cwt - Ttccdato, Alde r5,,O,

Terry Herndon, NEA Executive Director said, rrWe need members not subscribers.rr We

hope every member of Pickens Educatlonal Association, Alabama Education Association, and

the National Educational Associationwill be active participants in helping move our tmited

prcfessionals ahead.

The pickens Educational Association needs a voice in the educational policy-making and

decision-making of Pickens County Board of Education.

POLITICS

Teachers astive in Politics make better teachers and better citizens. Let us all work

together to improve support for education.

We need to elect honest, qualified and er<perienced leaders vfuo are committed to working

for the interest of teachers, students, the communlt5r, &nd the nation.

1977 NEA Convertion

APPLE

Pickens County Active Members

Reglster 22, 190 Active

PEA Membership-

Together we elected BOB LIPSC0ilB

to NEA Executive Committee

=

' ',*L'*#--*-L*"-**L**^-L4.#

.,u.%

Dear l{aggle,

We yaat you to }nos bor mrch re pereonally appreclate the help and eupport

of tbe Plctrens County Educatloa Aseoclatlon la the caopalga to elect

Alabaoare candldate to the NEA Executlve Cmlttee. Your poeltlon of

leaderehlp and lnfluence iu your local gave the eanpalgo a treoendous

boost, aud we are grateful that you sere able to lend your support.

lae vlctory sould not have beeo posslble rlthout the solldarlty of the

Alabma delegatlon at NEA aod tbe people back hoe sho bsd rork6rl the past

year to ualce 1t poselble. It yas apparent to everyooe that ALabalate

aupport ras solld ae a rock.

Pleaee couvey our appreclatlon to the neoberE of yotrr local for the uauy

tlnd rords of eacourageoert, the flDanclal contrlbutloaa, eod the physlcal

and moral support they gave to the caopalga.

Pleaee knos that I eteud ready to help you aod the teachers lu yorr loca1

when called upon. I am depeadlng ou you to help nake me a good NEA

Executlve Co@lttee ueober. Please keep ue apprlsed of your conceras.

I look forsard to our contlnued worklug together for the inprwenent of

educatlon T *. Datlon.

IIe dld lt!

&**

t"iJ 'i

t

:lt

;-il

\it

r

l

t"

.,.e

Slncelely,

bM

Robert Ltpeconb

Atu-

Athena Arrlngton

Caopalgn Coordlnator

3709 Sparkman Drive o Huntsrille, Alabama 35810