Maggie Bozeman and Julia Wilder: Advocates Jailed for Assisting Elderly Black Voters in Alabama

Civil rights demonstrators, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (not pictured), arrive in Montgomery, Alabama, on March 26, 1965, on the third leg of the Selma-to-Montgomery March for voting rights. (Photo by AFP via Getty Images)

“Throwback to the Old South”

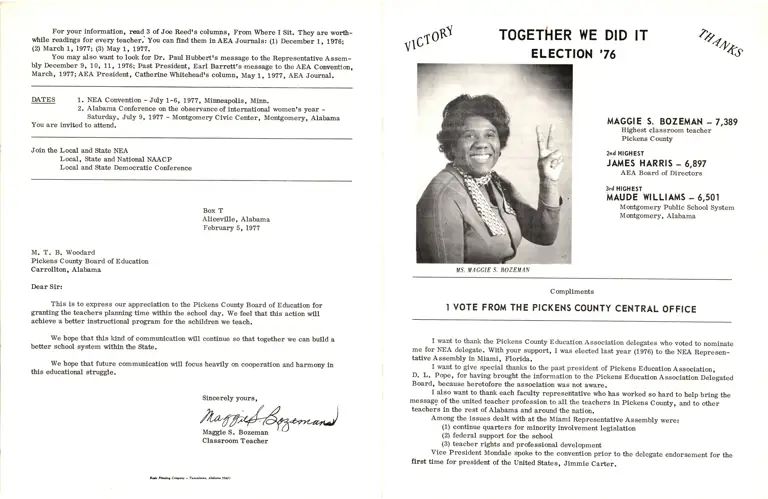

Before the local sheriff arrested her on voting fraud charges in 1978, Maggie Bozeman had been teaching school for 27 years in Pickens County, Alabama. It was educational inequalities that led Bozeman, a Black woman, to become a political activist. In the early 1950s, she went to Pickens County School Board meetings to question why, for example, some classrooms for Black students had enough supplies and seats, and others did not. The all-white school board held public meetings in a small room that could not fit many attendees. When Bozeman shared her concerns, the board members told her that she was “interfering with their meeting.”

NEA Congratulatory Pamphlet to Bozeman

“I didn’t know it was their meeting,” Bozeman said later. “I thought it was mine too.” Instead of staying silent, she encouraged more Black participation by inviting her Black friends and colleagues to join the meetings in the small room with her, and by organizing more Black people to register to vote.

By 1978, Bozeman and her friends had been helping to register Black voters for over a decade in Pickens County, a place that civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin later called “a throwback to the old South.” Located 75 miles southwest of Birmingham, Alabama, close to the Mississippi state line, Pickens County was 42% Black, but a Black person had never held county office there. Black locals told The Louisville Defender that a few “big-time white families,” descendants of slave-holding plantation owners, controlled the area’s “political, economic, and legal levers” with “a rule of terror and fear.” Knowing that white supremacists held office, many Black residents feared political involvement.

“It used to be nightriders to intimidate us. But Klan activity is sneaky. Now they wear neckties and suits,” Geraldine Sawyer, a Black woman and one-time mayor of the small Pickens County town McMullen, said to The Louisville Defender. “People are afraid. They fear they’ll lose their jobs or their homes if they register and vote.”

The courthouse in Carrollton, the county seat or capital, was the only place where many Black residents could register in person. But sometimes the doors were closed, and even when they were open, the sheriff stood watch over Black voters as they filled out forms. Many in the Black community felt that the sheriff’s gun and uniform contributed to an atmosphere of intimidation while they attempted to register to vote.

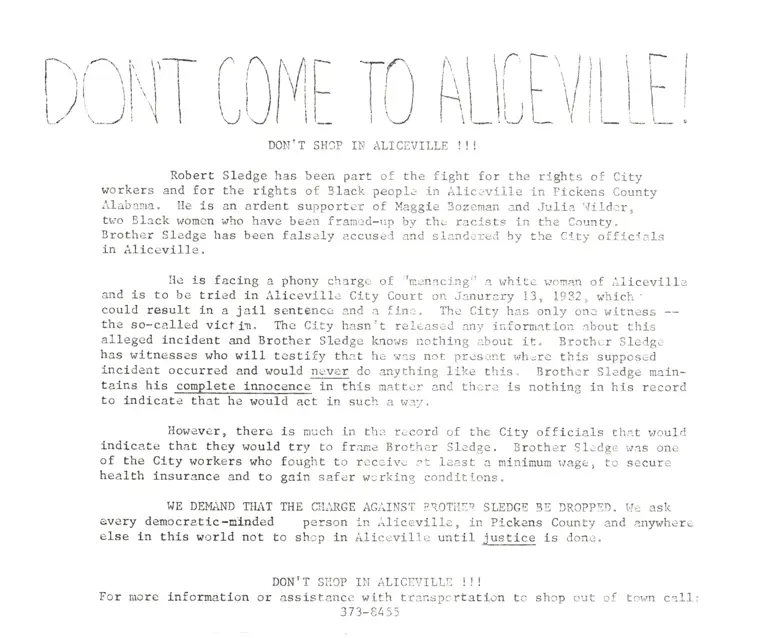

Don’t Come to Aliceville Notice

A Black grassroots effort to boycott the stores of a Pickens County city.

Black Activism in Pickens County Draws Attention

Despite these tensions, the Black citizens of Pickens County took pride in their community and called it “Glory Land.” To empower the county’s Black community and address persistent racial inequities, advocates, including Bozeman, organized local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Voters League. Bozeman and other Black activists began to use this collective power, organizing well-attended protests that secured better pay for sanitation workers and infrastructure improvements such as newly paved roads in Black neighborhoods.

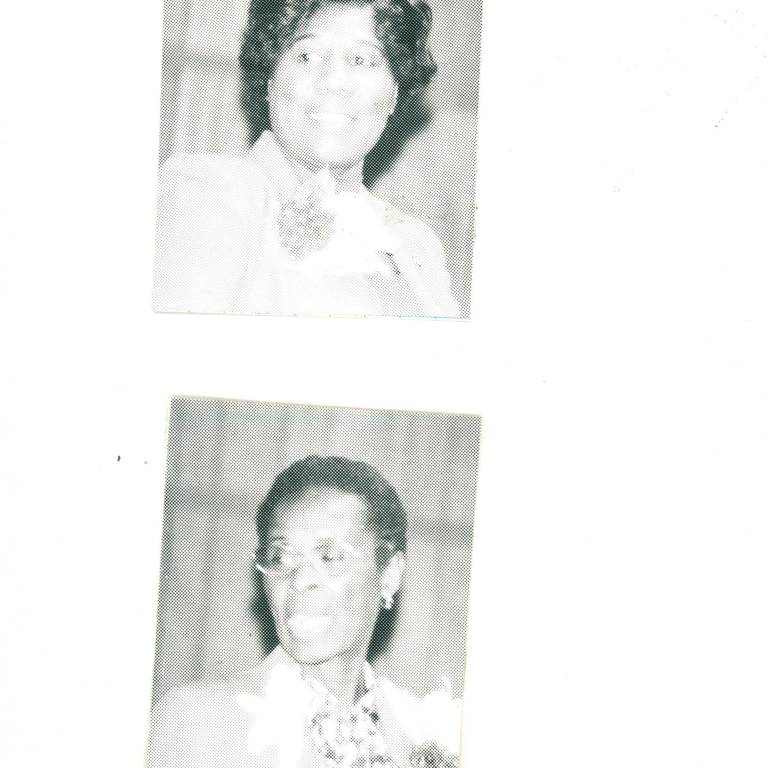

White authorities took note of the growing political power of the Black community. They seized a chance to curtail it in 1978, when a Black woman named Manny Dunner Hill planned to run against a white male banker for a school board seat. For the Dunner Hill election, Bozeman, then president of the local NAACP chapter, and Julia Wilder, then president of the Voters League and an officer of the SCLC, partnered with other advocates from the Voters League to provide absentee ballot applications to Black residents who could not vote in person because they were homebound or elderly and/or they could not read. Using three central mailing addresses as the return addresses, the voting advocates had the ballots notarized and sent to the County Election Commission. Dunner Hill won her primary on September 26, 1978.

Maggie Bozeman (top) and Julia Wilder (bottom)

Within days, the district attorney opened an investigation and issued subpoenas to 39 elderly Black voters whom Bozeman and Wilder had assisted. The probe spread fear throughout the rural Black community.

The day before the general election, as Bozeman returned from recess duty with her students, she saw five police cars outside her school. Officers arrested her and Wilder for forging signatures on absentee ballots. Terrified by the police activity against Bozeman and Wilder the day before the election, many Black residents abstained from voting, and Dunner Hill lost her school board bid by 106 votes.

On Election Day, a 79-year-old Black woman named Sophie Spann went to cast her ballot in person but was told she could not because she had already submitted an absentee ballot. Spann said she knew nothing about this. Although Bozeman and Wilder said that Spann had consented to participate in the absentee ballot process, the district attorney built a case against the activists based largely on this testimony.

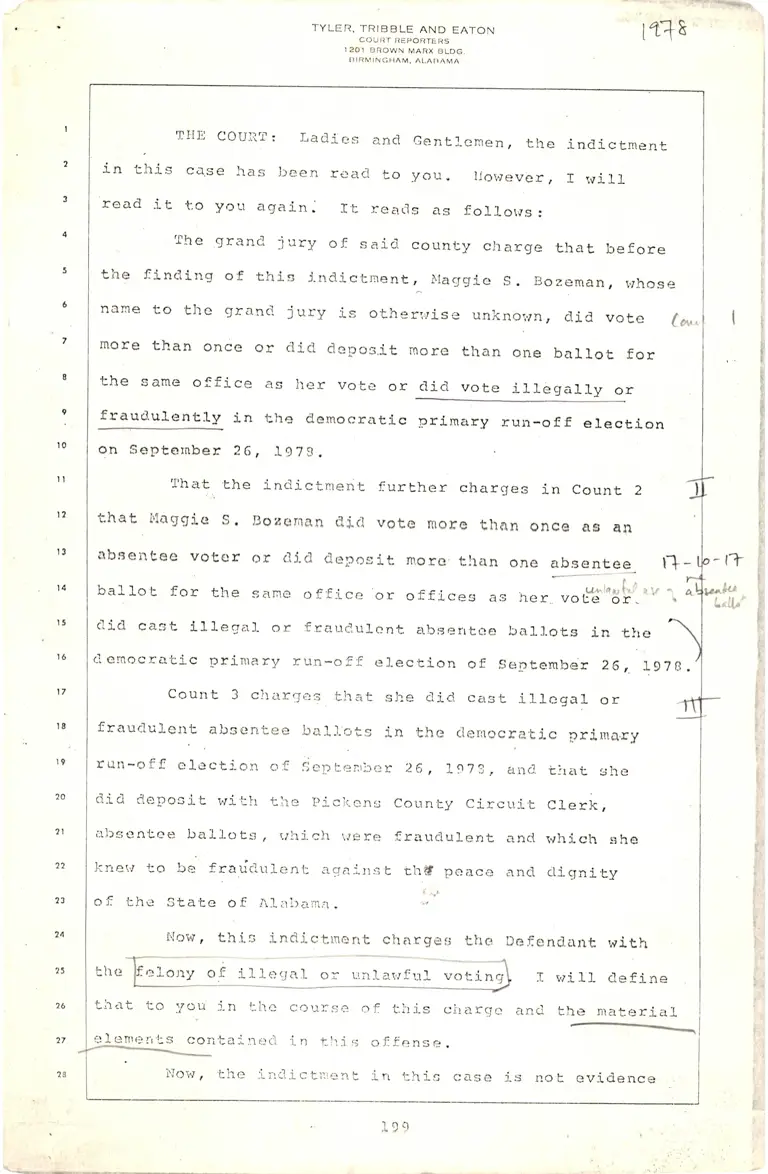

The Case Against Bozeman and Wilder

Both Bozeman and Wilder believed that they had handled the absentee ballots correctly, but there were technical problems with how the ballots were registered. During their trial before the Alabama Criminal Circuit Court for Pickens County, the prosecution contended that the women took applications for absentee ballots to elderly Black people, helped those who could not read fill them out and sign their names with an “X” mark, and then submitted the applications to the county election office. Because many of these voters could not read, the volunteers did not put the applicants’ addresses on the applications—instead, they used one of three central addresses, including one that belonged to Wilder. When the election office mailed the absentee ballots to these addresses, Wilder, Bozeman, and the other volunteers from the Voters League took them to the voters, helped the voters fill them out, and then had them notarized and sent back to the election office. The notary, a man in Tuscaloosa, told Wilder and Bozeman’s group that he needed to see the voters before notarizing their ballots. Due to many of the voters’ mobility limitations, the women assured him of ballot integrity so that the notary would agree to approve them.

Maggie Bozeman and others, 1982. (Atlanta University Center)

When the district attorney looked through one box of the absentee ballots, he noticed that 39 of them had identical votes, an identical notary, and an identical mailing address—that of Wilder’s home. In the fall of 1980, he put Bozeman and Wilder on trial for voting fraud and called 13 of these elderly Black voters to testify. Frightened and confused, many of these voters provided testimony that contradicted Bozeman and Wilder’s recollections of assisting the voters and submitting their absentee ballots.

Bozeman v. State Court Transcript

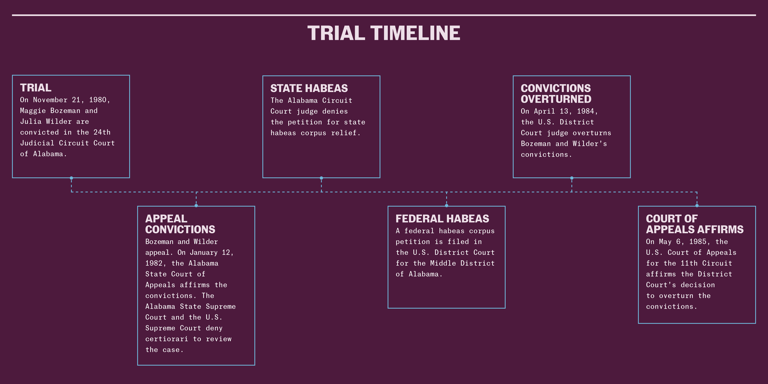

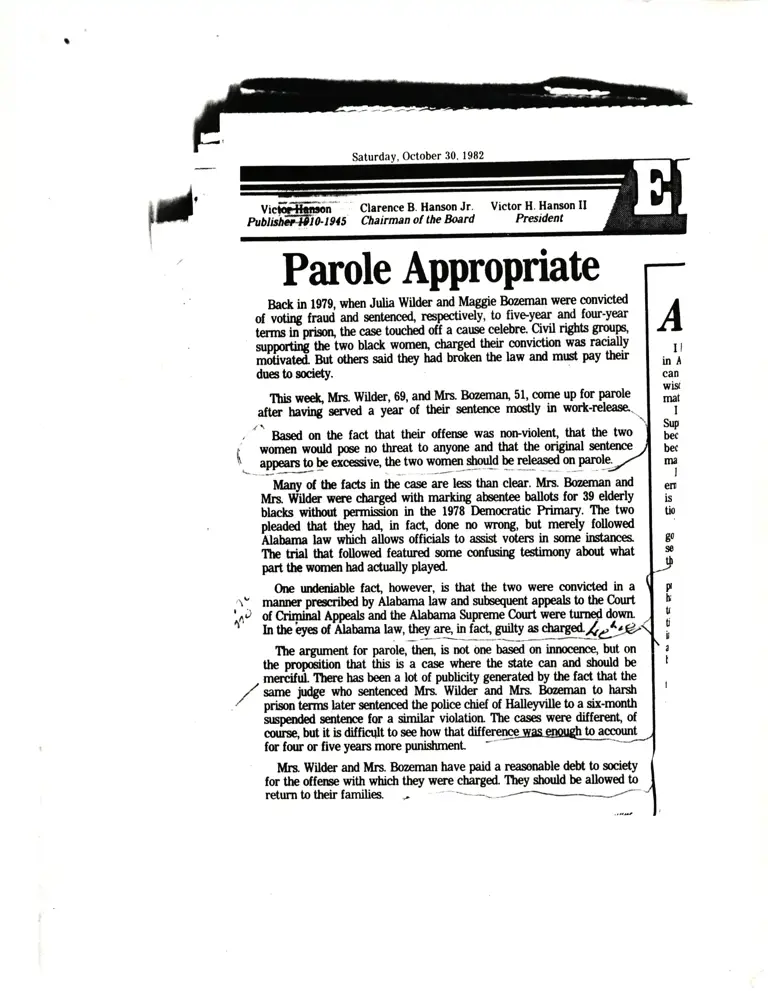

On November 21, 1980, an all-white jury convicted Bozeman and Wilder on charges of illegal voting in the 1978 election. Wilder, then 69, received the maximum sentence of five years, and Bozeman, 51, received four years. The Washington Post said that the sentences “are believed to be the stiffest ever given in an Alabama voting fraud case.”

Their legal counsel appealed. Upholding the convictions, judges on the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals noted in their opinion that they were concerned about the testimony of the elderly Black voters whose words were “confusing and conflicting, depending upon who was examining them.” Bozeman and Wilder’s attorneys included this concern in their appeal to the Alabama State Supreme Court, but it refused to review the case, as did the U.S. Supreme Court.

The women’s last chance for leniency came on January 12, 1982, when Alabama Circuit Court Judge Clatus Junkin considered their plea for lighter sentences. Fifteen character witnesses spoke on their behalf. Their lawyers argued that the case was racially motivated and intended to stop Black voter registration. Judge Junkin had the power to suspend the women’s sentences or to give Bozeman and Wilder probation in lieu of imprisonment. But in front of nearly 300 Black spectators, the judge denied leniency and ordered the women to immediately begin their prison sentences at the Tutwiler Prison for Women in Wetumpka, Alabama. Cries, yells, and moans filled the courtroom. As Judge Junkin demanded order, people began singing “We Shall Not Be Moved.” Police officers pulled the convicted women away from supporters who were holding and protecting them. Eventually, Bozeman and Wilder quietly submitted themselves to the sheriff’s custody.

“We knew we were framed,” Wilder later told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “Any time you try to do something for the upbuilding of humanity, you have to suffer.”

In an interview with The New York Times, Judge Junkin said the case involved “a straight-out crime” by “a couple of women who just flagrantly went out and stole 39 votes.”

Later, reporters discovered that the sheriff had a personal history with Spann, one of the Black elderly voters who had provided key testimony against the women. As a nanny, Spann had raised the sheriff’s deputy, who was also the sheriff’s son-in-law. Before Spann took the stand in Bozeman and Wilder’s trial, the sheriff himself had brought her lunch—which might have influenced her testimony.

The Legal Defense Fund Joins the Fight

Reading about the case in The New York Times in January 1982, Legal Defense Fund (LDF) Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg sensed that an injustice had occurred. He took the story to LDF voting rights attorney Lani Guinier, telling her, “Just get these convictions overturned.”

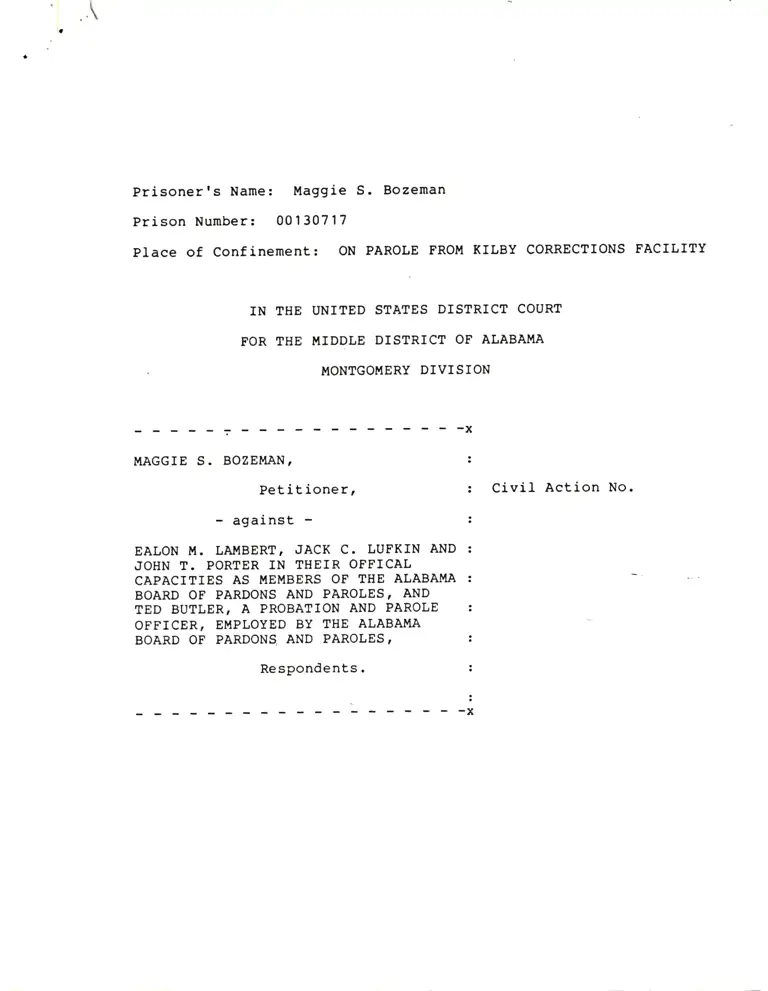

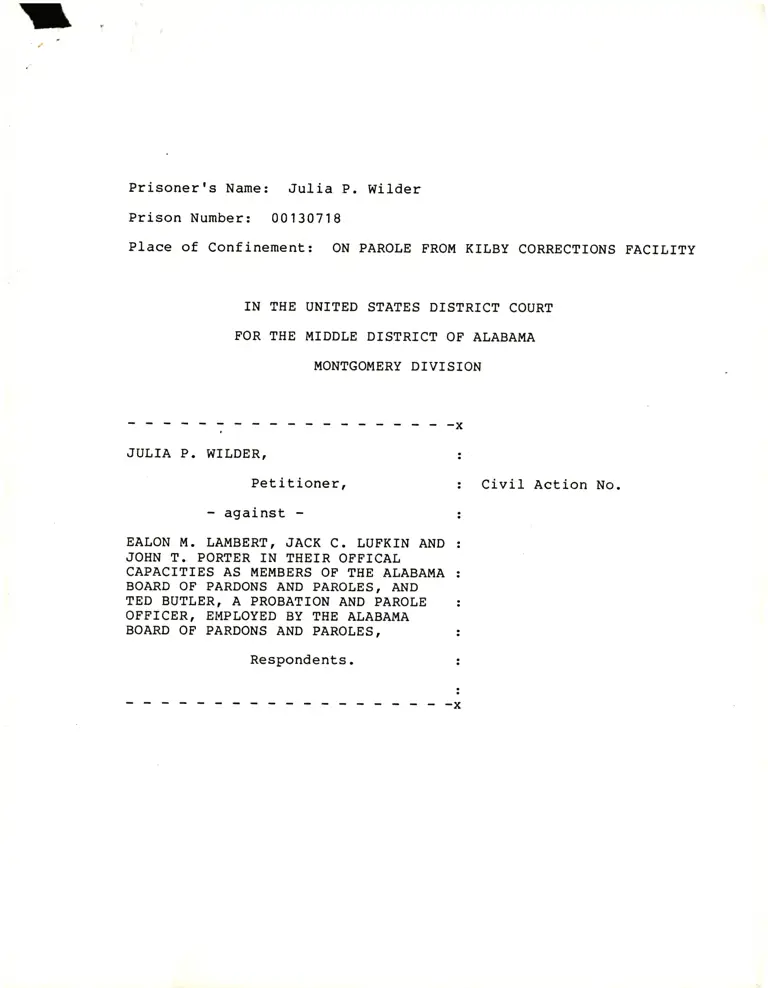

Guinier, along with other LDF attorneys, soon began working on filing habeas corpus petitions in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama seeking post-conviction relief. In the habeas petitions, LDF asserted that the state of Alabama was unlawfully detaining Bozeman and Wilder with convictions and sentences that violated their rights under the U.S. Constitution.

The effort to overturn the Alabama convictions fed into LDF’s legislative campaign to extend and amend the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which periodically required congressional reauthorization. If Congress did not reauthorize the act during the summer of 1982, key portions of the law would expire, including parts of Section Two that prohibited racially discriminatory election practices and procedures.

Bozeman and Wilder’s stories humanized the goals of the Voting Rights Act by demonstrating the kind of discriminatory election procedures the law was designed to prevent. As news spread about these Black activists who had been targeted as part of a larger effort to suppress the Black vote, grassroots demands to free them fueled a sustained movement to strengthen the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Bozeman v. Lambert Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus by a Person in State Custody

Wilder v. Lambert Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus by a Person in State Custody

Trial timeline for Bozeman and Wilder

Public Outcry Grows

Within two weeks of arriving in prison, Bozeman and Wilder entered a work release program that let them live in a mobile home in Tuskegee rather than a jail cell. The move was the result of public outcry about their imprisonment. Immediately after Judge Junkin’s decision, civil rights leaders and lawyers put political pressure on Alabama officials, including Governor Forrest “Fob” James and the state corrections commissioner, in a series of private meetings. As a result, Governor James expedited Bozeman and Wilder’s transition to work release, an action that civil rights activist Rustin said gave “credence to the view that Mrs. Bozeman and Mrs. Wilder were imprisoned falsely.” The Pickens County affair, Rustin wrote in the Los Angeles Sentinel, highlighted “the obstacles minorities face in their efforts to fully participate in the political process.”

To support the women, activists organized a series of events that kept their story in the national spotlight. On February 7, 1982, Southern civil rights workers and several hundred supporters started a 140-mile march from the courthouse in Carrollton, Alabama, to the State Capitol building in Montgomery. By the time the march finished 13 days later, 30 national organizations and approximately 3,000 people had joined. Sponsored by the SCLC and the “National Coalition to Free Julia Wilder and Maggie Bozeman and Save the Voting Rights Act,” the march drew national attention to the link between the women’s incarceration and the political battle being waged in Washington, D.C.

The march partly overlapped with the route from Selma to Montgomery taken 17 years before on Bloody Sunday, when police had attacked peaceful protesters marching in support of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. John Lewis, a future 17-term U.S. Representative, returned in 1982 to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where police had beaten him in 1965. Of his return, Lewis, who had just won his first local political office, told The New York Times, “I came back today with a sense of hope and determination that we are on the verge of building a new movement.” Richard Arrington Jr., the first Black mayor of Birmingham, emphasized the need for justice for Bozeman and Wilder.

"As long as freedom fighters like Maggie Bozeman and Julia Wilder can be railroaded, jailed in the Pickens Counties of America, justice is still on trial," Richard arrington said to The New York Times.

Two months later, on April 17, 1982, the Southern Rural Women’s Network held a summit in Pickens County in support of women’s and rural issues. Women from across the country traveled in caravans from the Carrollton Courthouse to Tuskegee, where as part of the work release program Bozeman taught classes to children with developmental disabilities and Wilder worked at a senior center. The event included a prayer vigil in Montgomery attended by 800 people on the steps of the State Capitol.

To keep pressure on Congress, the SCLC sponsored a 2,000-mile march one week later from Tuskegee to Washington, D.C. After crossing five Southern states where discriminatory electoral practices routinely violated civil rights, the two-month “march-motorcade” reached the nation’s capital on June 23, 1982, the same day that Congress renewed the Voting Rights Act. In her book Lift Every Voice, LDF attorney Guinier attributed this legislative victory to grassroots activists, writing, “It was the plain speech of ordinary people that would help the rest of America bear witness to a different vision.”

Bozeman and Wilder Released

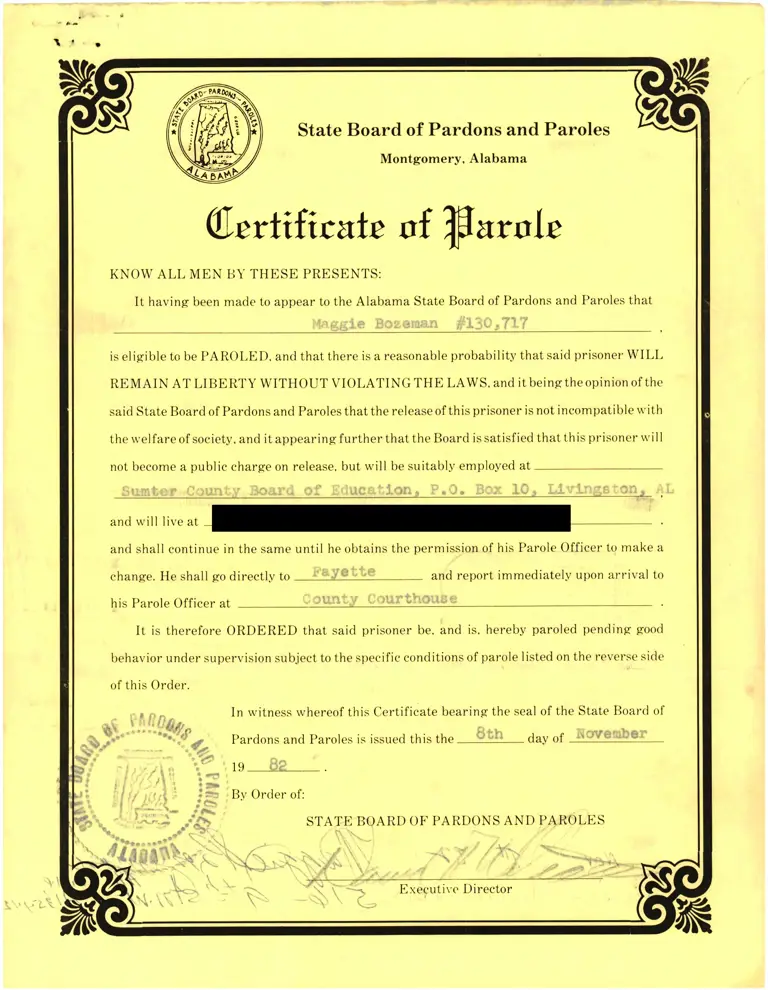

On November 2, 1982, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to release Bozeman and Wilder on parole, after more than nine months of receiving telegrams and petitions from across the country demanding their release. “It was definitely the public pressure that brought about their early release,” Judy Hand of the Southern Organizing Committee for Racial and Economic Justice said to The Louisville Defender.

But, as Bozeman said to the Defender in an early November interview shortly after her parole, “The struggle is not over.” The all-white Pickens County School Board had fired her after her conviction. She was offered another teaching position, but it was 30 miles away from her house and not in Pickens County, the district she had called home for 27 years. And after being convicted of felonies, the women did not have certain rights, including the right to vote. Referring to her parole, Bozeman said, “This is the first step towards the right road to justice. Pickens County is Glory Land for us, but we are not free. We don’t know how long it will be before our civil rights are restored. We don’t know what the power structure might do to us.” She said she would not ask for a pardon, explaining to the Defender, “The system inflicted this on us. Let the courts overturn the conviction. I want to see it resolved in court. We’ll not come begging for mercy.”

Bozeman/Wilder News Clippings; Memo; Testimony of Bozeman; Recollections of the Interview with Judge Junkin, Fayette; Correspondence from Braden to SOC Executive Committee; Selma March Articles (Redacted)

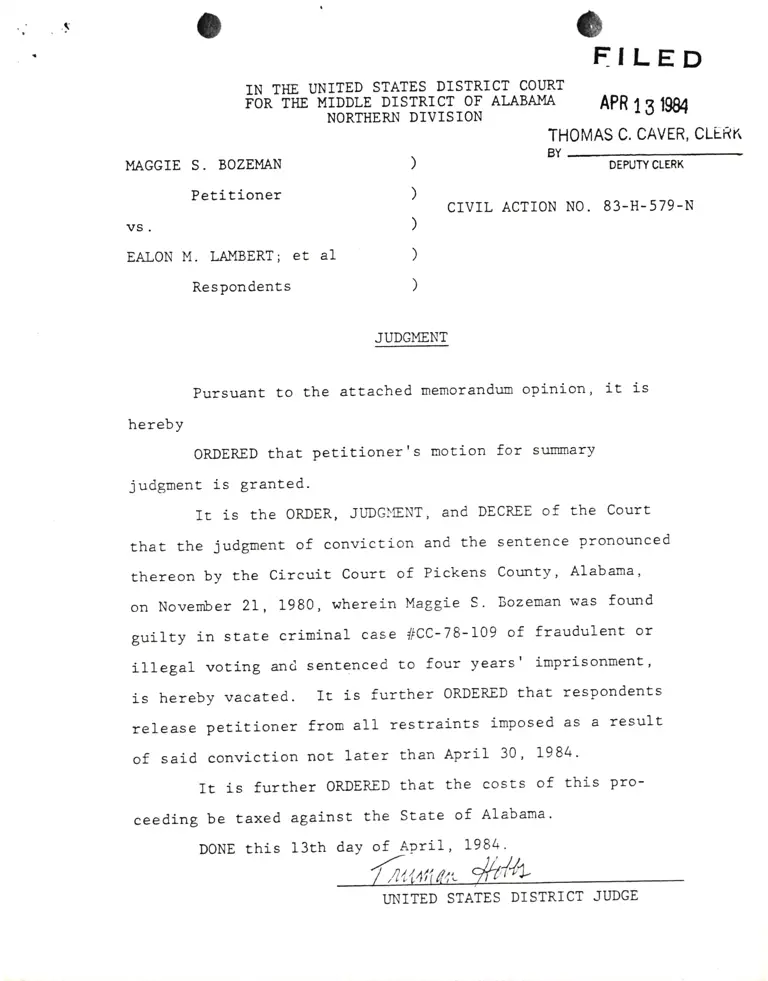

In civil habeas corpus petitions filed in federal court against the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles (known as Bozeman v. Lambert, et al. and Wilder v. Lambert, et al.), LDF argued that the prosecution had violated Bozeman and Wilder’s Sixth Amendment rights by trying and convicting them for offenses with which they were never charged. LDF also asserted that there was insufficient evidence to try the women on charges of fraudulent voting.

What is a habeas corpus petition?

A habeas corpus petition is a lawsuit brought by a person who is detained to challenge the lawfulness of their conviction or sentence. It is a civil action against a state agent (typically the warden) who is holding the person in custody.

Federal habeas corpus: A person who was convicted in state court can file a federal habeas corpus petition after exhausting state remedies. The person files a writ of habeas corpus under 28 U.S. Code Section 2255 in the U.S. District Court for their jurisdiction. If relief is denied at the District Court, the petitioner may appeal to the federal Circuit Court of Appeals for further review. If the Court of Appeals does not grant relief, then they may file a writ of certiorari before the U.S. Supreme Court.

On April 13, 1984, Judge Truman Hobbs overturned Bozeman and Wilder’s convictions. In his opinion, Judge Hobbs found that the women’s Sixth Amendment rights had been violated because the accusations against them were not fully outlined until after the defense rested its case. Judge Hobbs issued separate judgments on LDF’s claim that there was insufficient evidence for a jury to charge Bozeman and Wilder with fraudulent or illegal voting. He said that there was sufficient evidence for a jury to convict Wilder with casting an improperly notarized ballot. The state had not charged Wilder with this crime, but Judge Hobbs said they had 90 days to do so. Because no absentee ballots had been mailed to Bozeman’s address, the judge said that no inference could be drawn that she had intentionally taken part in forging a ballot.

Judgment

"There is a world of difference between forging a person’s ballot and failing to follow the proper procedure in getting that person’s ballot notarized," Judge Hobbs stated. "If petitioners were facing the latter charge, they had a right to be told. They were not. To put it simply, petitioners were tried upon charges that were never made and of which they were never notified. Thus, their convictions cannot stand."

Julia Wilder and Maggie Bozeman registered elderly Black voters in Pickens County, Alabama, 1970-80.

Certificate of Parole for Bozeman (Redacted)

Although the Alabama attorney general, after pressure from Black legislators, decided not to appeal, the local district attorney appealed the decision. In May 1985, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld Judge Hobbs’ ruling, stating that authorities had tried Bozeman and Wilder for offenses with which they were never charged.

Vanzetta Penn Durant, a Montgomery-based attorney who represented the women from 1978 to 1985, told The Atlanta Journal Constitution that her clients were guilty of nothing but encouraging Black people to vote. “The aim of the prosecution from beginning to end was to dilute Black voting power,” she said. But instead of diluting the power of the Black vote, the case strengthened it by mobilizing a civil rights movement that successfully pushed for the extension of the Voting Rights Act.

As SCLC President Joseph E. Lowery said of white authorities in a speech upon the women’s parole, “Because you put them in prison, all of us are stronger today.”