Motion to Proceed as Amicus Curiae; Memorandum in Support of Motion to Proceed as Amicus Curiae and in Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion to Remand; Correspondence from Bradford Reynolds to Brock; Envelope to Guinier

Correspondence

June 28, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Motion to Proceed as Amicus Curiae; Memorandum in Support of Motion to Proceed as Amicus Curiae and in Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion to Remand; Correspondence from Bradford Reynolds to Brock; Envelope to Guinier, 1982. 2400a483-d792-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5bf2871e-0d5b-4459-8ecd-5cf5303b1c6a/motion-to-proceed-as-amicus-curiae-memorandum-in-support-of-motion-to-proceed-as-amicus-curiae-and-in-opposition-to-plaintiffs-motion-to-remand-correspondence-from-bradford-reynolds-to-brock-envelope-to-guinier. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

6-za-dt

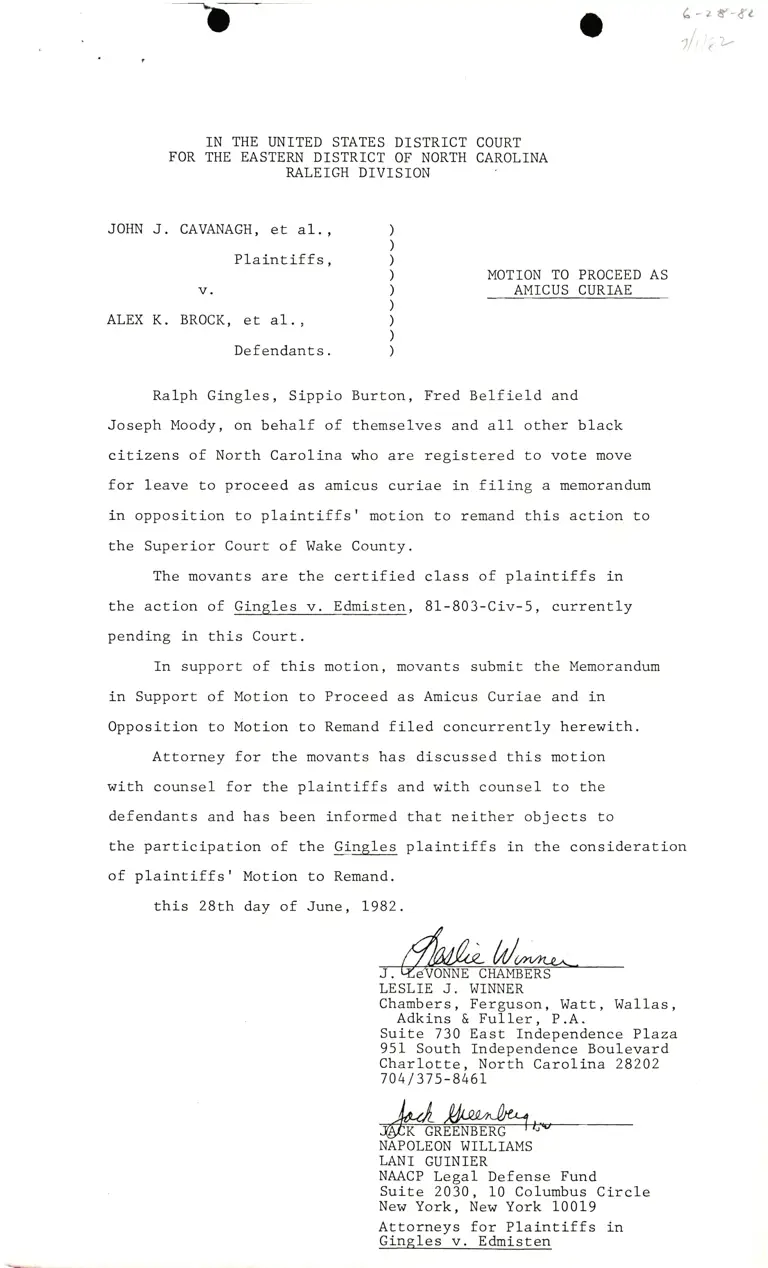

IN THE I]NITED STATES DISTRICT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH

RALEIGH DIVISION

COURT

CAROLINA

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, €t al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

ALEX K. BROCK, €t dl.,

Defendants.

MOTION TO PROCEED AS

AMICUS CURIAE

Ralph Gingles, Sippio Burton, Fred Belfield and

Joseph Moody, oD behalf of themselves and all other black

citizens of North Carol-ina who are registered to vote move

for leave to proceed as amicus curiae in filing a memorandum

in opposition to plaintiffs' motion to remand this action to

the Superior Court of hlake County.

The movants are the certified class of plaintiffs in

the action of Gingles v. Edmisten, 81-803-Civ-5, currently

pending in this Court.

In support of this motion, movants submit the Memorandum

in Support of Motion to Proceed as Amicus Curiae and in

Opposition to Motion to Remand filed concurrently herewith.

Attorney for the movants has discussed this motion

with counsel for the plaintiffs and with counsel to the

defendants and has been informed that neither objects to

the participation of the Gingles plaintiffs in the consideration

of plaintiffs' Motion to Remand.

this 28th day of June , L982.

LESLIE J. WINNER

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, I,rlallas ,

Adkins & Fu1ler, P.A.

Suite 730 East Independence Plaza

95L South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

704137s-846r

NAPOLEON WILLIAMS

LANI GUINIER

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs in

Gingles v. Edmisten

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MLEIGH DIVISION

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, et a1., )

)

Plaintiffs, ) MEMOMNDI'M IN SUPPORT OF

) I,TOTION TO PROCEED AS AMICUS

) CURIAE AND IN OPPOSITION TO

) PLAINTIFF'S MOTION TO REMAND

v.

ALEX K. BROCK, et a1., )

)

Defendants. )

I. STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action challenges the apportionment of the North

Carolina General Assembly on the ground that the apportionment

fails to comply with Article I1 S3(3) and S5(3) of rhe Norrh

Carolina Constitution. These provisions prohibit the division

of any county in creating representative districts for the

North Carolina House of Representatives and the North Carolina

senate. The action was filed in the superior court of wake

County seeking to prohibit defendants, various state officiaLs,

from conducting an election pursuant to the challenged appor-

tionment. Defendants removed the action to this Court pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. $1443(2), and plaintiffs have moved ro remand

the action to State Court.

Ralph Gingles, Sippio Burton, Joseph Moody and Fred

Belfield, oD behalf of themselves and all other black citizens

of North carolina who are registered to vote, move for leave

to proceed as amicus curiae and to file a Memorandum in Opposi-

tion to Plaintiff's Motion to Remand.

II. ARGUMENT IN SUPPORT OF MOTION

TO PROCEED AS AMICUS CURTAE

The movants have been certified as the class of plaintiffs

in Gingles, et al. v. Edmisten, et al., Civil Action Number

81-803-Civ-5, currently pending in the Eastern District of

North Carolina. That action, in part, challenges Article fI,

S3(3) and 55(3) of Lhe North Carolina Constitution as

violaring 52 of rhe Voring Rights Acr of L965, 42 U.S.C.

S1973, 42 U.S.C. 51981 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the united states constitution. The complaint

alleges that the challenged portions of the North carolina

Constitution have the purpose and effect of denying bLack

citizens the right to use their vote effectively because

of their race.

In addition, Gingles challenges the specific apportion-

ments enacted because of their result of dilution of minority

voting strength. The Gingles plaintiffs request that the

Court require North Carolina to apportion the legislature

in a manner which fairly reflects minority voting strength,

and plaintiffs contend that the State's refusal to divide

counties necessarily prevents them from having an apportion-

ment without a discriminatory result.

The determination of the question raised in Cavanagh v.

Brock, that is, the enforcability of Articles II S3(3) and

S5(3), of the North Carolina Constitution, will inevitably

have an impact on the determination of the claims raised

in Gingles v. Edmi-sten. The Gingles plaintiff s, therefore,

have an interest in litigation at hand. They request to

file this memorandum in order to urge the Court to allow

the importanL civil rights question raised in Cavanagh to

be considered in by federal court and to a11ow these inter-

twining questions in the Cavanagh, Gingles, and Pugh cases

to be determined by a single court, the federal court in

which they are already pending.

III. ARGU},IENT IN OPPOSITION TO REMAND

Defendants in Cavanagh base their motion to remand on

28 U.S.C. S1443(2) which provides:

Any of the following civil actions or crimi-

na1 prosecutions, cormnenced in a State court may

be removed by the defendant to the districL court

of the United States for the district and division

embracing the place wherein it is pending:

(2) For any act under color of authority

derived from any- 1aw providing for equal rights,

or for_r_efusing to do anv act on the-ground that

it would be inconsistent with ql4h law. (Emphasis added.)

-2-

under this section removal is proper when a state court

action challenges the refusal of state officials to comply

with a state law or requirement and the refusal is on the

grounds that compliance would violate federal law which

protects equal rights.

This action is exactly such an action. Whatever its

form, the heart of the complaint in cavanagh is a challenge

to the refusal of the State of North Carolina and its officials

to comply with Article II S3(3) and 55(3) of rhe Norrh Carolina

Constitution in enacting the 1981 apportionment of the North

Carolina General Assembly. There is no dispute that the

State did, indeed, refuse or fail to comply with these provi-

sions in dividing Forsyth and several other counLies. Thus,

the on1-y real question presented by the litigation is whether

that failure was justified in order to comply with federal

statutes and constitutional provisions and, therefore, was

required by the supremacy clause of the united States consti-

tution, Article VI, S2.

This is the very kind of situation for which 51443(2)

refusal removal was intended. As explained in Bridgeport

Education Association v. Zinr,gr, 415 F.Supp . 715, 7LB (D. Conn.

L978), when the predecessor of S1443 was enacted, Representa-

tive wilson proposed an amendment to cover refusals to act in

addition to actions under Federal authority. He explained

his amendment by saying, "[T]his amendment is intended to

enable State officers, who shalt refuse to enforce State laws

discriminating... on account of race or color, to remove

their cases to the united states courts when prosecuted for

refusing to enforce those 1aws." Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., lst

Sess. at t367, ds quoted in Bridgeport Ed. Ass'n v. Zinner,

supra.

The statute has been applied to a11ow

in e.g", Inlhite v. I,rlellington, 627 F.2d 582

Bridgeport Ed. Ass'n v. Zinner, supra; and

removal of cases

(2d CLr. 1980) ;

O'Keefe v. New York

City Bd,of Elections, 246 F. Supp . 978 (S.D. N.y. 1965) .

-3-

o

In White v. Wellington, supra officials of the City

of New Haven refused to comply with various provisions of

the state civil service laws because they alleged that to

do so would be in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of L964, prohibiting racial discrimination in employment.

This action to enforce the state civil service laws was held

to be properly removed under the refusal clause 28 U.S.C.

S1443(2). Bridgeport Ed. Ass'n v. Zinner, E-gp:e, had essentially

similar facts.

In O'Keefe v. New York City Bd. of Elections, supra, City

elections officials refused to enforce the New York State

literacy test because they alleged that it violated the Voting

Rights Act of 1965. The Court held that the citizens' action

to require enforcement of the literacy test was properly removed

under the refusal clause of 28 U.S.C. 51443(2).

Each of these cases is parallel in all important aspects

to the case at hand in which state officials have refused

to comply with provisions of the North Carolina Constitution

which violate the Voting Rights Act and other federal requirements.

There is no dispute thaL defendants in Cavanagh v. Brock

are state officials. They are designated as such in the

Complaint, Part II. As state officials they are entitled

to invoke the refusal to act portion of 51443(2). See, in

addition to l,rlhite , supra, Zinner, supra, and O'Keef e , e-]]Pra,

West Vir8inia Bar v. Bostic, 351 F.Supp. 1118 (S.D. W.Va.L972)t

Burns v. Board of School Conrrnissioners , 302 F. SupP. 309 (S.D.

Ind. L969), aff 'd 437 E.2d 1143 (7th Cir. L971-).

In this respect, Massachusetts Counq.l-I pf Construction

Employees v. White, 495 F.Supp. 220 (D.Mass. 1980), is not

to the contrary. The Court ordered a remand under 51443(2)

of an action against State officials who were held not to

be acting under federal authority under the "[F]or any act

under color of authority" clause of S1443(2). There was

no discussion of their right as State officials to invoke ttre

-4-

"for refusing to do any act" clause of 51443(2). Rather the

court held that it was an action and not a. refusal to act

which was challenged and that use of the latter clause was

not appropriate. Id. at 222,

Similarly, Folts v. City of Richmond, 480 F.Supp. 62I

(E.D. Va. L979) is not contrary on this poi.nt. The defen-

dant officials of the city of Richmond were held not to be

acting under Federal authority under the "for any act" clause.

The "refusal to act" removal was rejected, not because defen-

dants were not the proper persons to invoke it, but because

defendants did not predieate the removal on a federal law

providing for equal rights. Id. at 626.

Since defendants are state officials, and since the

complaint challenges the refusal or failure to comply with

the state constitution, the only question is whether that

refusal is arguably justifiable by the inconsistence of the

state law with a federal 1aw providing for equal rights.

At this stage the defendants only have to show a colorable

conflict between the state and federal laws and do not have

to establish that they are likely to prevail on the merits.

see white v. wellington, 627 F.2d at 586-587; Bridgeporr Ed.

Ass'n v. Zinner, 4L5 F.supp. at 722-723. This is logical since

the onLy inquiry now is which court should ultimately determine

the merits, and requiring a showing of likelihood of prevail-ing

would require the federal court to predetermine the merits

of the equal rights defense.

rn this case, defendants say that their failure to comply

with the North carolina consititution was necessary in order

to comply wirh 55 of rhe Voring Righrs AcL of L965 and, in

particular-, the requirement of the Attorney General of the

united states that Guilford county be apportioned in a way

that fairly reflects the voting strength of the black citizens

of that county. The affidavits of}{essrs. Hale and Long tend

to establish that it was necessary to divide adjacent

-5-

Forsyth County, a county not covered by 55, in order to

apportion Guilford County, in a manner that does comply

with 55.

At this point defendants do not have to show that

they will prevail on their defense of the necessary conflict

between the North Carolina constitution and the Voting Rights

Act. They merely have to raise a colorable conflict between

state and federal law. This they have done.

In addition to 55 of the Voting Rights Act there are,

however, several other federal equal rights statutes and

constitutional provisions which are necessarily in conflict

with Article II 53(3) and S5(3) of Lhe Norrh Carolina Consri-

tutionr 52 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 3s amended,

42 U.S.C. 51973, 42 U.S.C. 51981 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution. Whether the

division of non-S5 covered counties in the apportionment

of the North Carolina General Assembly is required by these

provisions is the essential question raised in Gingles v.

Edmisten; it is a question appropriately raised in a federal

court and already pending in this court. The question is not

frivolous. As the United States Department of Justice found

in its objection to these provisions under S5, "IT]he use

of such multi-member districts necessarily submerges cognizable

minority population concentrations into 1-arger white electorates.

In the context of the racial bloc voting that seems to exists,

such a phenomena operates and would continue to operate 'to

minimize or cancel out the voting strength of racial...elements

of the voting population.' Fortsonv. Dorsev, 37g U.S. 433,

439 (1965)." See letter of William Bradford Reynolds dated

30 November 1981, attached.

This reasoning applies as well to the 60 counties not

covered by 55 as it does to the 40 counties which are covered.

There is clearly a colorable claim that compliance with these

North Carolina Constitutional provisions outside the S5 covered

-6-

counties is in conflict with federal statutes and constitutional

provisions which prohibit racial discrimination and apportionment

of representative districts.

The federal court has jurisdiction to answer this question,

and a staters refusal to comply with a state 1aw contrary

to these federal equal rights provisions justifies removal

under 28 U. S.C. S1443(2) .

In addition, 28 U.S.C. 51443(2) refers to federal laws

"providing for equal rights." This contrasts to 28 U.S.C.

51443(1) which speaks of laws providing for "equal civil

rights. " Assuming that this difference is for a purpose,

then 51443(2) should not be limited to federal laws prohibiting

L/

racial discrimination as is S1443(1). - But cf. Appalachian

Volunteers v. Clerk, 432 F.2d 530 (6ttr Cir. L970) (applying

the Supreme Court interpretation of S1443(1) to S1443(2)

but only with regard to the "act under color of authority"

phrase. )

If conflicts with other federal equal rights provisions

justify removal under S1443(2), then there is further reason

to deny the motion to remand. There is ample evidence in

the transcripts of the North Carolina House and Senate Redis-

tricting Committees to support the conclusion that the state

refused to fo11ow the North Carolina Constitution prohibition

against dividing counties in areas not covered by 55 in part

because of the one person-one vote requirement of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution, and in part because to apply that State

Constitutional provision to. some parts of the state and not

to others was itself perceived to be a violation of the equal

protection clause. See, e.B. Dtmston v. Scott, 336 F.Supp.206 (E.D.N.C. L972).

Since the equal protection clause is obviously a "law

providing for equal rights, " the state's refusal to follow

the state consLitutional provisions in order to avoid a conflict

with the equal protection clause also justifies removal under

28 u.s.c. s1443(2).

L/ Note that each citation that addresses this question

on pl-4 of defendants' Brief in Opposition to Remand ionsiders

the question only for 28 U.S.C. Sf443(f).

-7-

CONCLUSION

At the heart of cavanagh v. Brock is a series of federal

statutory and constitutional questions. Because of the pendency

of Gingles v. Edmisten and Pugh v. Hunt, this court already

has before it the question of whether the division of counties

in apportioning the General Assembly is perrnissible or required

under Ehe Voting Rights Act and the United States Constitution.

rf the judgment of this court were inconsistnet with the

judgment of the state court i, ggygqqgh v. Brock, the defendant

state officials would be subjected to mutually exclusive

mandates. There can be only one apportionment of the North

carolina General Assembly. whether the one enacted is lega1.

and enforceable is, at this time, essentially a series of

questions of federal 1aw. These questions should be answered

by a single federal court. The motion to remand should be

denied.

rhis 24 day of June, L982.

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallas,

Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730 East Independence PLaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

704-375-846r

'ia

LANI GU]NIER

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs in

Gingles v. EdmisLen

LESLIE J. WINNER

R

LEON WILLIAMS

-8-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have this day served the foregoing

Motion to Proceed as Amicus curiae and Memorandum in support

of Motion to Proceed as Amicus curiae and in opposition to

Plaintiff's Motion to Remand upon all other counsel by pracing

a copy of the same in the United States post Office, postage

prepaid, addressed to:

Mr. Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

Attorney at Law

Post Office Box 3245

20I West Market Street

Greensboro, North Carol-ina 27402

Mr. James Wallas, Jr.

Deputy Attorney General for

Legal Affairs

N.C. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Mr. Jerris Leonard

Jerris Leonard & Assoc, pC

900 17th Streer, NW

Suite 1020

Washington, DC 20006

This 2( day of June, L982.

Mr. Arthur J. Donaldson

Burke, Donaldson, Holshouser

& Kenerly

309 North Main Streer

Salisbury, NorLh Carolina 28L44

Iulr. Wayne T. E11iot

Southeastern Legal Foundation

1800 Century Boulevard, Suite 950

Atlanta, Georgia 30345

Mr. Hamilton C. Horton, Jr.

Itrhiting, Horton & Hendrick

450 NCNB PLaza

Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27L01

-9-

U,.4f;*-*

.di_1Fv.r:,,: :,Wy', (

U.S. Department of Justicr

CivilRights Divi( r

Oflicc ol the Assistont Auorney General Washington, D.C. 205j0

3 0 tioy ,98t

l4r. Alex Brock

Executive Secretary - Director

State Board of Elections

suite 801, Raleigh Building

5 West Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina 2760L

Dear Mr. Brock:

This is in reference to the 1968 amendment (H.8. No. 47L

(L967)), which provides that no county shall be divided in the

formation of a Senate or Representative district and which was

recently submitted to the Attorney General pursuant to Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. L973c.

Your submission was completed on October 1, 1981.

We have made a careful review of the information that you

have provided, the events surrounding the enactment of the change,

the application of the amendment in past legislative reapportion-

ments, and commenEs and information provided by other interested

parties. 0n the basis of that analysis, we are unable to conclude

that this amendment, prohibiting the division of counties in

reapportionments, does not have a discriminatory purpose or effect.

Our analysis shows that the prohibition against dividing

the 40 covered counties in the formation of Senate and House

districts predietably requires, and has led to the use of, large

multi-member disEricts. Our analysis shows further that the use

of such multi-member districts necessarily submerges cognizable

minority population concentrations into larger white electorates.

In the context of the racial bloc voting that seems to exist, such

a phenomenon operates and would continue to operate "to minimize

or cancel out that voting strength of racial elements of the

voting population." Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433, 439 (1965).

((r)

-l-

2

Ttris determination with respect to the jurisdictions

covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act should in no

way be regarded as precluding the State from following a

policy of preserving county lines wtrenever feasible in

formurating its new districts. rndeed, this is the poricy in

many states, subject onry to the preclearance requirements of

Section 5, vtrere applicable. In the present submission,

howeverr we are evaluating a legal requirement that every

county must be included in the plan as an undivided whole.

As noted above, the inescapabre effect of sueh a requirement

is to submerge sizeable black communities in large multi-

member districts.

Under these circumstances, and guided by the standards

established in cases such as Beer v. United States, 425 U.S.

130 (1976), we are unabre to GTtude ttrEffiffiB amendment

requiring nondivision of counties in legislative redistricting

does not have a racially discriminatory purpose or effect.

Accordingly, on behalf of the Attorney General, I must

interpose an objection to that amendment insofar as it affects

the covered counties.

Of course, as provided by Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Actr 1zou have the right to seek a dectaratory judgment

from the United States District Court for the District of

Columbia that this change has neither the purpose nor will

have the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on

account of race, color or membership in a language m5-nority

group. In addition, the Procedures for the Administration of

Section 5 (Section 5L.44, 46 Fed. Reg. 878) permit you to

request the Attorney General to reconsider the objection.

However, until the objection is withdrawn or the judgment

from the District of Columbia is obtained, the effect of the

objection by the Attorney General is to make the 1968 amendment

legally unenforceable.

If you have any questions concerning this matter,

please feel free to call Carl W. Gable (202-724-7439), Director

of the Section 5 Unit of the Voting Section.

Since re1y,

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

Wm. Bradford Reyno

CHAMBERS, FERGUSON, WATT, WALLAS. ADKINS & FULLER. P.A

ATORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 73O EAST INOEPENDENCE PLAZA

95I SOUTH INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARO

CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA 2A2O2

It'ls. I€ni

I{MCP b1pJ.

Srite 2030,

Nou York, Noo