U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74L Ed 2d (Brown v Socialist Workers '74 Campaign Committee)

Unannotated Secondary Research

October 4, 1982 - December 8, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74L Ed 2d (Brown v Socialist Workers '74 Campaign Committee), 1982. 3fed54af-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8d049e10-0d6d-41b0-854d-86da5defcf86/us-supreme-court-reports-74l-ed-2d-brown-v-socialist-workers-74-campaign-committee. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74LEA?d'

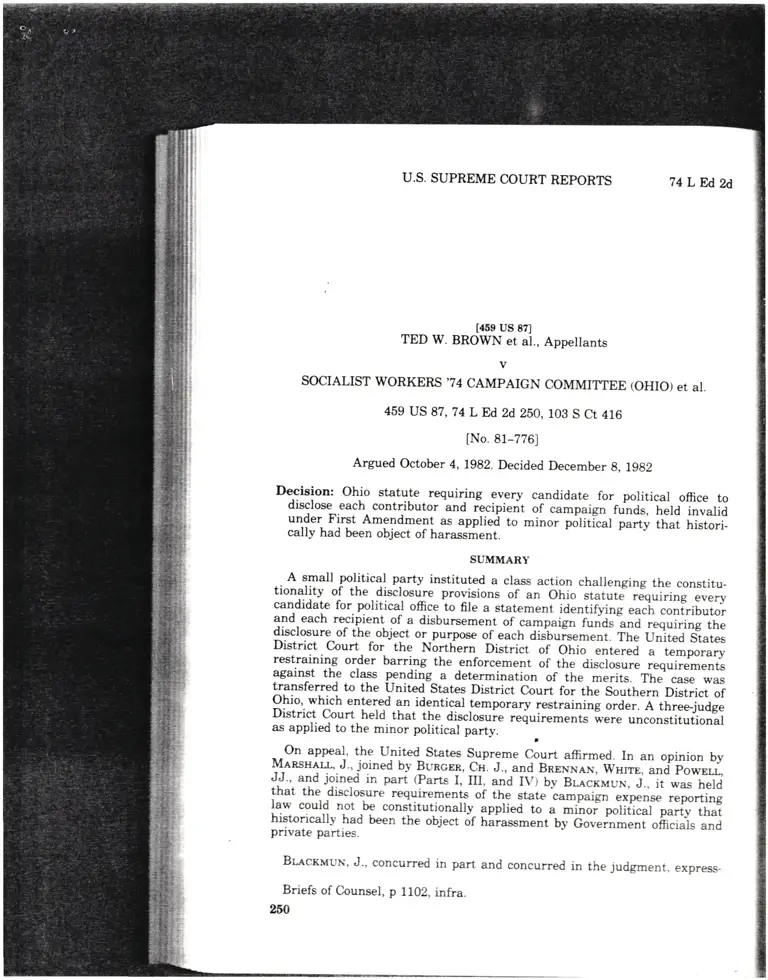

ld6e us 871

TED W. BROWN et al., Appellants

v

socIALIsr woRKERs '24 CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE (oHIo) et al.

459 US 87,74 L Ed 2d 250, 103 S Ct 416

[No. 81-726]

Argued October 4, LggZ. Decided December g, 1gg2

Decision: ohio statute requiring every candidate for political office todisclose each cont':ibutor and recipient or ca-frig-frr'.rd., trela invaliaunder First Amendmel-t as applied to minor p"titi*r p"rty that rristori-cally had been object of harassment.

SUMMARY

. A small political p_arty instituted a class action challenging the constitu-tionality of the disclosure provisions of an ot io siaiuie- requiring every

can-didate for political office to file a statement identifyinj each contributorand-each recipient of a disbursement of -campaign r"ras'a"a ."q"i.i"l trr"disclosure of the objelt or_purpose of each ais'u"fte*e"i. The united statesDistrict court for-the Nb"tte"" -Disirict

of otrio u.,t".La a temporaryrestraining order barring the enforcement of the disclosure requirements

psaingt the class pgldilg- a determination of the merits. The "*" **transferred to the United States District Crcurt for tfru So"tt ern Oisirict ofohio, which entered.an identicar temporary restraining order. a ttrree-:uiseDistrict Court held that the disclosure requirem""ut ir"ie ,rnconstitutional

as applied to the minor political party. ,

on appeal, the u.nited states s^upreme court affirmed. In an opinion by

!I-e,nsnt,.r,, J., joined by puncrn,_q". J.,an4 Bnr*Ni", W*", and pownu,

J.J.,. a1d joined in part (parts I,'[I, and tVl Uv e;;;;;, J., it was heldthat the disclosure requirements of the state tampaign expense reportinglaw could not be constitutionary- applied t" ";i;;;-po-tiii.rr party thathistorically had been the object 6r ni.'"r"r."ent by co*,"irr*errt officials andprivate parties.

BLn'cxMUx, J., concurred in part and concurred in the judgment, express-

Briefs of Counsel, p 1102, infra.

?,60

74L&c U

trE (OHIO)et al.

t6

8, 1982

: political office to

funds, held invalid

party that histori-

lnging the constitu-

rte requiring every

ng each contributor

s and requiring the

The United States

bered a temporary

csure requirements

rits. The case was

iouthern District of

rrder. A three-judge

re unconstitutional

I. In an opinion by

i/nrrr. and Pownu.,

uN, J.. it was held

expense reporting

nlitical party that

nment oficials and

judgment, express-

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS'74 CAMP. COMM.

459 US 87,74L8,d2d250,103 S Ct 416

ino the view that the court should not have reached the issue whether a

ifndard of proof different from that applied to disclosure of campaign

intriUutions should be applied to disclosure of campaign disbursements.

O'CoNNon,,J., joined by RrnNqursr and SrrvrNs, JJ., concurred in part

and dissented in part, expressing the view that the Etatute was invalid as to

th" di""loture of contributors but that the statute was valid as to the

disclos,r"e of the recipients of expenditures.

HEADNOTES

Ctassified to U.S. Supreme Court Digest, Lawyers'Edition

Constitutional Law $ 940.5 - First disbursement, cannot be constitutionally

Amendment - minor political applied to a minor political party that

party-_ -. disclosure of political h-istorically has been the object of ha-

contributions and expenditures rassment by Government officials and

- stat€ statute

la, 1b. The disclosure requirements of private parties; the First Amendment

a 6tate campaign *p";*-;;;ffi L;, prohibits a state from compelling disclo-

ifri"f, .ornplh-"reryc"rrdiaate fo."potiti- sures by a minor party that wili subject

;i-;ffi; tb tle a itut"rn"nt identifying those persons identified to the reason-

each contributor and each recipient'of a able probability of threats, harassment,

disbursement of campaign funds and to or reprisals, since such disclosures would

disclose the object or purpose of each infringe the First Amendment rights of

TOTAL CLIENT.SERVICE LIBRARY.S REFERENCES

16A Am Jur 2d, Constitutional Law $S 545, 546; 25 Am Jur

2d, Elections $ 117

USCS, Constitution, 1st Amendment

US L Ed Digest, Constitutional Law $$ 940.5, 959

L Ed Index to Annos, Associators and Clubs; Campaign Ex-

penses; Elections; Freedom of Speech, Press, Religion, and

Assembly

ALR Quick Index, Campaign Expenses; Elections; Freedom of

Association; Freedom of Speech and Press; Political Parties

Federal Quick Index, Campaign Expenses; Elections; tr''reedom

of Association; Freedom of Speech and Press; Political

Activities and Matters

ANNOTATION REFERENCES

Supreme Court's views regarding the First Amendment right of association as

applied to the advancement of political beliefs. 67 L Ed 2d 859.

The Supreme Court and the right of free speech and press. 93 L Ed 1f51, 2 L Ed

2d 1706, 11 L Ed 2d 1116, 16 L Ed 2d 1053, 21 L Ed 2d 976.

State regulation of the giving or making of political contributions or expendi-

tures by private individuals. 94 ALR3d 944.

26r

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74LEd2d

t

E

.a-

t

the party and iL. members and support-

ers. (O'Connor, Rehnquist, and Stevens.

JJ., dissented in part from this holding.r

Constitutional Law $ 959 First

Amendment - disclosure of polit-

ical association

2. The Constitution protects against

the compelled disclosure of political asso-

ciations and beiiefs since such disclo-

sures can seriouslv infringe on privac-v of

association and belief guaranteed by the

First Amendment; the right to privacy

in one's political associations and beliefs

will yield only to a subordinating inrer-

est of the state that is compelling, and

then only if there is a substantiai rela-

tion between the information sought and

an overriding and compelling state inter-

est.

Appeal and Enor $ I08S - review -questions considered-power of

Supreme C,ourt

3a, 3b. The question whether the tesi

for safeguarding the First Amendment

interests of minor political parties re_

garding compelled disclosure of cam-

paign contributors also applies to the

compelied disclosure of recipients of'

campaign disbursements is properly be-

fore the Supreme Court u.here the- Dis.

trict Court necessarill-held that the test

appiies to both contributions and expen-

ditures and that the evidence was suffi_

cient to show a rea-sonable probabilitl.

that disclosure would subject both con-

tributors and recipients to pubiic hostil_

ity and harassment and where the cor_

rectness of the District Court's holdings

are fairl-y included in the question pre-

sented in the jurisdictional statement.

Constitutional Law g 940.b - First

Amendment - minor political

partl'disclosure of political con_

tributions and expenditures

4. The government inrerests in compel-

ling disclosure o{ informarion concerning

campaign contributions and expendi-

tures are weaker in the case of minor

political parties. u'hile the threai t()

First Amendmeni values is greater. both

of these considerations applr not onlv t.o

252

the disclosure of the names of campaign

contributors but also to the disclorr.e of

names of recipients of campaign dis_

bursements. (O'Connor, Rehnquiit, and

Stevens, JJ., dissented from this hold_

ing. )

Constitutional Lau, $ 940.5 - First

Amendment - minor political

party - disclosure of political

expenditures

5a, 5b. Minor polirical parties are enti-

tied to an exemption from requirements

that recipients of campaign expenditures

be disclosed vyhere the-y ca, sho*, a ,"a-

sonable probability of harassment, since

the governmenr interest is substantiallv

reduced in the case of minor parties; a

Iegitimate government interesi in pre-

venting corruption by requiring the dis-

closure of recipients of campaign dis-

bursements has less force in the context

of minor poiitical parties since minor

parties are not as likely as major parties

to make significant expenditures in fund-

ing dirty tricks or other improper cam-

paign activities and since the expendi-

ture bl minor parties of even a substan.

tial portion of their limited funds on

illegal activities would be unlikelv to

have a substantial impact; the mere pos-

sibiiitl' that minor parties rx'ill resori to

corruption or unfair tactics cannot jus-

tifl' the substantial infringement on

First Amendment interests that would

result from compelling the disclosure of

recipienrs of expenditures. (O'Connor,

Rehnquist, and Stevens, JJ., dissented

from this holding.)

Constituf,ional Lau' g g40.5; Evidence

S 96I - First Amendment - dis-

closure of political contributions

and expenditures - test for ex-

empting minor political part1.

6. The test for safeguarciing the First

Amendment interests of minor politicai

partres and their rrrerrbe.s ani support-

ers appltes not oni. 1o r-h! corrrr,eljeC

dist'losure oi cz.rnpai;:; c{,niributurs nut

also to the con:peiiec criajosL:i-e oi'rectp .

ents of campaigr, dtsbursentenLs: the tesl

lbr delerr::lning u.her: rhe Firsr Ainend.

ment requires exemptin[: ri]nor parties

74 LDd 2d

.he names of campaign

Iso to the disclosure of

nts of campaig:n dis-

rnnor, Rehnquist, and

ented from this hold-

aw $940.6 - Firet

minor political

closure of political

Iitical parties are enti-

on from requirements

ampaign expenditures

they can show a rea-

of harassment, since

Lerest is substantiallv

e of minor parties: a

rent interest in pre-

by requiring the dis-

rts of campaign dis-

r force in the context

parties since minor

kely as major parties

expenditures in fund-

other improper cam-

I since the expendi-

es of even a substan-

ir limited funds on

luld be unlikely to

mpact; the mere pos-

rarties will resort to

r tactics cannot jus-

il infringement on

nterests that would

.ng the disclosure of

rditures. (O'Connor,

vens, JJ., dissented

' $ 940.5; Evidence

imendment - dis.

:ical contributione

'e6 - t€st for ex-

political partS'

rguarding the First

r of minor political

mbers and support-

to the compelled

ln contributors but

disclosure of recipi-

ursements: the test

r the First Amend-

ting minor parries

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS ,24 CAMP. COMM.

459 US 87,74LF!2d2fi.103 s ct 416

from compelled disclosures is that the names are disclosed; evidence of private

evidence offered need- show only a rea- and governm""i-r,o.tiuty to*ria-" ,ni-

eonable probability that rhe compelled nor frlitical p"ity

"ia its members es-

disclosure of a party's contributors' tablishes

" ,;;;;;"b1" p.ou"uiiii; th"t

names will subject them to threats, ha- disclosing tt e names of contributors anJ

rassment, or reprisals .from either gov- recipients will subject them to th;";,

ernment officials or private parties; mi- harassment, .Jl"pri""ls where it isnor parties must be allowed sufficient shown that there haie been threatenine

oexibilitv in the proof of injury. phone calls, t.te mait, i;; ;ffi;;";?

constitutionar r.aw g e40.8; Evidence ffilil ffi::U:'ff.:"ilX,,:1":1Xt

$ 96r - First Amendment - mi- party candidate, the firing of shots at anor political party - discrosure party office, -;.i;; government surveil-ofpolitical expenditures iance of";;"r,r,;"i a Federal Bureau7a-7c. A minor poriticar party does nor of Investigad;;-i;;;l".inreligence pro_have to prove that ch,l and harassment gram dirJctd .g.i"rt the party; evi-are directly attributable to a statute's lence of ;;;;ri';;J past harassment

disclosure requirements in estabrishing a suggests that hostility to*,ard the partyreasonable probability that recipienLrof ir*Ingr"in"J ."J^"iir."rt- to continue.campaign expenditures will be subjected (.O'Coinor, n"fr"qUrt, and Stevens, JJ.,tD threats and harassment if their dissented ir;;i;;;this holding.)'

--'

SYLLABUS BY REPORTER OF DECISIONS

Held: The disclosure provisions of the crosure of campaigrr contributors butohio campaign Expense Reporting Law also to th; ;;;;[.,"d;disclosure of recipi-requiring every candidate for poritical entsof."-purCJiJr]rsements.

office to report the names and addresses (b) Here, ine"bisi.i.t cou.t, in uphold_of campaign contributors and recipients ing appellee.' .h"li;;;" to the constitu-of campaign disbursements, cannot be tio'naliiy

"f

-th;

ohi; disclosure provi-constitu-tionally applied to appellee So .;o.rr, i"op".l,

-""i.irO"d

that the evi_cialist workers parrv (swpj, a minor dence of p;i;;i"-;;;'dore.nment host,-political party that historicall-v r,"" b."" ity to*a.d the swp and its membersthe object of harassment by Government eitabrishes . ."*onubr" probability thatt4"i"1". and.private parties. disclosing the names of contributors and(a) The First Amendment prohibits a recipienti *ill-.ru:".i them to threars,state from .compelling discroiures b1: a harassment, and reprisals.minor political party that will subject Afrrmed.

those persons identified to the reason- Ma_rshall, J., derivered the opinion ofable probability of thre_ats, harassment, the court, i" ;hi;h ilurger, c.J., andor reprisals. Bucklev v^V^al9o, 424 US 1, C.".r.ru.r, White. and powell. JJ., joined,?4' 46 L Ed 2d 6s9, 96 s ct'6ir: M;.;: and in parts r, III, and IV of r*.hichover, minor parties must be alrowed suf- Br"ckmun, J., j;i"J] ir""k-rrr,, J., firedficient flexibility in the-proof-of injurj' in opinion concurring in part and con-Ibid rhese principles. 16. ..r"gu"iJr.rg Iu..i.,g in the judgment. o,connor, J.,the First Amendment interests 6i -inoi n1.a ; "pi"i"""""i"r..ing in part andparties and their members and support- Jisserting'i; ;;---i; which Rehnquisters apply nor only ro the compell# dis- and Ste..&s, "rj" lli*a

APPEARANCES OF COUNSEL

Gary Elson Brown argued the cause for appellants.

Thomas D. Bucklev, Jr. argued the cause-fbr appellees,Briefs of Counsel, p if OZ, irrfi^.

253

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS

OPTNION OT'THE COURT

74LEdtut

[{59 US 8t]

Justice Marehall delivered the

opinion of the Court.

[1a] This case presents the ques-

tion whethei certain disclosure re-

quirements of the Ohio Campaign

Expense Reporting Law, Ohio Rev

Code Ann $ 3517.01 et seq. (1922 and

Supp 1981), can be constitutionally

applied to the Socialist Workers

Party, a minor political party which

historically has been the object of

harassment by government ofrcials

and private parties. The Ohio stat-

ute requires every political party to

report the names and addresses of

campaign contributors and recipi-

ents of campaign disbursements. In

Buckley v Valeo, 424 US 1, 46 L Ed

2d 659, 96 S Ct 612 (1976), this Court

held that the First Amendment pro.

hibits the government from compel-

ling disclosures by a minor political

party that can show a "reasonable

probability" that the compelled dis-

closures will subject those identified

to "threats, harassment, or repri-

sals." Id., at74,46 L Frt 2d 6Eg, 96 S

G,612. Employing this test, a three.

judge District Court for the South-

ern District of Ohio held that the

Ohio statute is unconstitutional as

applied tn the Socialist Workers

Party. We aftrm.

I

The Socialist Workers party

6WP) is a small political party with

approximately 60 members in the

State of Ohio. The Party states in its

constitution that its aim is ,,the abo

lition of capitalism and the estab-

lishment of a workers' government

to achieve socialism." As the District

Court found, the SWP does not advo

cate the use of violence. It seeks

instead to achieve social change

through the political process, and its

members regularly run for public

office. The SWP's candidates have

had little success at the polls. In

1980, for example, the Ohio SWp's

candidate for the United States Sen-

ate received fewer than 27,000 votes,

less than LgVo of the total

[45e US Ee]

Campaign contributions and "rt!f:ditures in Ohio have averaged about

$15,000 annually since 1974.

In 1974 appellees instituted a class

action' in the District Court for the

Northern District of Ohio challeng-

ing the constitutionality of the dii-

closure provisions of the Ohio Cam-

paign Expense Reporting Law. The

Ohio statute requires every candi-

date for political office to file a state

ment identifying each contributor

and each recipient of a disbursement

of campaign funds. g 3512.10., The

. l-. The plaintiff clem as eventually certifed

includes all SWP candidates for poliiical office

in Ohio, their campaign commitiees and trea-

surers, and people who contribute to or re

ceive disbureements from SIVp campaigr

committees. The defendants are the Ohi6 Sec_

retary of State and other state and local

ofrcials who administer the disclosure l8w.

2. Secuon 3517.10 provides in relevant part:

"(Al. Every campaign committee, potiiicat

commitr€e. and polirical party which made or

received a contribution or made an expendi_

ture in connection with the nominatiion or

election of any candidarc at any election held

2tt4

in this state shall file, on a form prescribed

under this eection, a full, true, and itcmlzed

Btstement, made under penalty of election

falsiEcation, eetting forth in detail the contri-

butions and expenditures .

-(Bi Each statement required by division (A)

of this section shall conrain ihe follo*.ing

information:

"(4) A etatement of contributions made or

received, which ehali include:

"(a) The month, day, and year of the contri-

bution:

BTS 74LEA2I

nall political party withy 60 members in the

. The Party states in its

;hat its aim is ,,the abo

italism and the estab-

t workers' government

rialism." As the District

the SWP does not advo.

of violence. It seeks

rchieve social change

olitical process, and its

ularly run for public

iVP's candidates have

:cess at the polls. In

nple, the Ohio SWp's

lhe United States Sen-

werthan Z7,AOO votes,

of the total

169 US Egl

-_ vote.

lributions and expen-

I have averaged about

ty smce 1924.

lees instituted a class

)istrict Court for the

ict of Ohio challenp_

rtionality of the ;i:-

ns of the Ohio Cam-

Reporting Law. The

rquires every candi-

I office to file a state.

rg each contributor

nt of a disbursement

nds. $ 3512.10., The

'object or PurPose"s

[45e US 00]

of each dis-

bur:ement must also be disclosed.

The lists of names and addresses of

oontributors and recipients are open

to public inspection for at least six

years. Violations of the disclosure

requirem,ents are punishable by fines

of up to $1,000 for each day of viola-

tion. $ 3517.99.

On November 6,1974, the District

Court for the Northern District of

Ohio entered a temporary restrain_

ing order barring the enforcement of

the disclosure requirements against

the class pending a determinatlon of

the merits.. The case was then trans_

ferred to the District Court'for the

Southern District of Ohio, which en-

tered an identical temporary re.

straining order in February igZS.,

Accordingly, since 1924

[45e US el]

have not disclosed trre n"m#:illi::

tributors and recipients but have

otherwise complied with the statute.A three-judge District Court ;;

9-o-nv-ened pursuant to 2g USC g 22g1

[28 USCS $ 2281]. Foilowing ;;t *

sive discovery, the trial was"held in

Feb-ruary 1981. After reviewing the

"substantial evidence of both go-""i"-

mental and private hostility ioward

and harassment of SWp meinbeisand supporters," the three_judge

court concluded that under AucUey

u

^Yaleo,

424_US 1. 46 L Ed 2d 6ig,96 S ct 672 (1976), the ohio

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS ,24 CAMP. COMM.

459 US 87 , 7 4 L Ft 2d 250, 103 S Ct 416

rle, on a form prescribed

r -full, true, and itemized

rder penalty of election

orth in detai.l the contri_

ure6.

reguired b.v division lA)I contain the follou.ing

f contribuiions made or

rnclude;

'. and year of the contri-

"(b) The full name and address of each

person, in-cluding any chairman o. treasu.Li

tlrereof if other than an individual, from

whom c.ontributions are received. The .eo"i.._

ment of filing the full address aoes

"ot a"ofuto an)' statement filed by a state o. to"j

oommitlee of a political party, to

" n"."""

committee of such committee,

-or

to a

"o__it_tee_ recognized by a state or local commlltee

as-its fund-raising auxiliary

"(o. A^ description of the contribution re.

ceived, if other than money;

"td) The value in dollars and cents of the

contribution:

-

"ter All contributions and expenditures

ahall be itemized separarely ."g.;ei;;i;;;

amount except a receipt of i contribution

trom a person in the sum of twenty_five dol.lars or less at one social o, f"na_".iJing

""it-i-ty. An account of the rotal

"o"tiiButio".from each such eocial or fund_raisin;;;;il:

shall b€ lisred separarety, td"il;;-";th'il'.

expenses incurred and paid in connectionwith,such. activity. No continuing

"di;ii;;wnlch makes a contribution from funds whichare derived solell- from regular a"*-p"iJ'Ui

me5nbery of the association shall be requirj

to. hst the name or addres-" oi

".,, -"L-Uu.lwho paid such dues.

."li, a staLemenr of expend:rures whichahall include:

- "(a) The month. da1.. anC rea;- of expendi-ture:

"(bt The full name and address of eachperson to whom the expendrture *.-. -"a".

including any chairman or treasurer thereofif a commitrce, association,

". ;;;; ;-;;-

sons;

"tct 15" object or purpose for *.hich theexpendlture was made:

"(d) The amount of each expendit.ure.

"....: 4ll such sratements shail be open topublic inspection in the offic" whe." ,f,'*'.ifiled, and shall be carefuily p.;;;;-i";';

period ofat least six years.'.

_If the candidate is running for a shtewide

offce,-the statement shall fe fil; ;;;;';;;

Ohio Secretan- of State: otherwise, ,f,"-rt [_ment shall b€ 61ed with the

"pp.op-ri"Lcounty board of elections. g SSfZ.fftar.

-'-----

3. g 3S1Z.l0GX5Xc).

.1. Tt" order restrained various state off-

i.il,ffJ :l"'{Xf, .i:,W.:;:1lx'i'}:

Ohio Campaign .Expense n"fi"..irl-'f.""' r#

Lne. penalt\. provision of that lau.. the effect of*'hich wjll be to postpon" ,f," U"eir;ii"'JiaI) possrble period of r.iolation of thar lar^f biptarntrus, . until such time as the case lldecided by the three judge p"r,"f.'r.t-it' i.-

nereb)- convened." tCitations omitted. I

5. Apparentl.v none of the parties throush_out th€ &year period questioneci *h"il;;;;

extended duration of the temporar-l. restrain_

ing- order conformed to tt" iequii"-""r.'.f

Rule 650) of the Federat Bules

"iCi"iii;t*dure,

255

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPOBTS 74LEd2d

disclosure requirements are uncon'

stitutional as applied to appellees.o

We noted probable jurisdiction. 451

vs L122,71 L Ed 2d 108, 102 S Ct

968 (1981).

II

t2l The Constitution Protects

against the compelled discloeure of

political associations and beliefs.

Such dieclosures "can seriously in-

fringe on privacy of association and

belief guaranteed by the First

Amendment." Buckley v Valeo, su-

pra, at U, 46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S Ct

612, citing Gibson v Florida Iegisla-

tive Comm., 372 US 539, 9 L Ed 2d

929, 83 S Ct 889 (1963); NAACP v

Button, 371 US 415, I L &l 2d 405,

83 S Ct 328 (f9ffi); Shelton v Tucker,

364 US 479,5 L Ed 2d 231, 81 S Ct

247 (I9ffi); Bates v Little Rock, 361

us 516, 4 L Ed 2d 4W,80 s Ct 412

(1960); NAACP v Alabama, 357 US

449, 2 L Ed 2d 1488, 78 S Ct 1163

(1958). "Inviolability of privacy in

group association may in many cir-

cumstanoes be indispensable to pres-

ervation of freedom of association,

particularly where a group espouses

dissident beliefs." NAACP v AIa-

bama, supra, at 462, 2 L M 2d

1488, 78 S Ct 1163. The right to

privacy in one's political associ-

ations and beliefs will yield

[45e US 92]

the Stat€ [that is] compelling,"'

NAACP v Alabama, supra, at 463,2

L Ed 2d 1488, 78 S Ct 1163 (quoting

Sweezy v New Hampshire, 354 US

234,265,1 L Ed 2d 1311, 77 S Ct

1203 (1957) (opinion concurring in

result), and then only if there is a

"substantial relation between the in-

formation sought and [an] overriding

and compelling state interest." Gib-

son v Florida Legislative Comm., su-

pra, at 546, I L Ed 2d 929, 83 S Ct

889.

In Buckley v Valeo this Court up

held against a First Amendment

challenge the reporting and discle

sure requirements imposed on politi-

cal parties by the Federal Election

Campnjgn Act of L971. 2 USC $ 431

et seq. [2 USCS $$ 431 eL seq.). 424

US, at W74,46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S

Ct 612. The Court found three gov-

ernment interests sufEcient in gen-

eral to justify requiring disclosure of

information concerning campaign

contributions and expenditures:7 en-

hancement of voters' knowledge

about a candidate's possible alle-

giances and interests, deterrence of

corruption, and the enforcement of

contribution limitations.s The Court

stressed, however, that in certain

circumstances the balance of inter-

ests requires exempting minor politi-

cal parties from compelled disclo-

sures. The government's interests in

only to a "'subordinating interest of compelling disclosures are "dimin-

6. Because it invalidated the Ohio Btatute as

applied to the Ohio SWP, the District Court

did not decide appellees'claim that the stat-

ute was faciall;- invalid. The Ohio statute

requires disclosure of contributions and ex-

penditures no matter how small the amount.

Ohio RBv Code Ann $ 3517.10GX4xe\ (Supp

1981t. Appellees contended that the absence

of a monetary threshold rendered the statute

facially invalid since the compeiied drsclosure

of nominal contributions and expenditures

iacks a subetantiai nexus with an1' ciairr,ei

government interest. See Bucklel' v \raieo.

424 US, at 8?,44, 46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S Ct

6t2.

The District Court's opinion is unreported.

?.56

7. Title 2!USC $$ 432, 4U, and 438 (1976

ed, supp v) [2 uscs $$ 432. 434 and 438]

require each political committee to keep de-

tailed records of both contributions and ex-

penditures, including the names of campaign

contributors and recipients of campaign dis-

bureements, and to fiIe reports with the Fed-

eral Election Commission which are made

available to the public.

8. The government interest in enforcing

Iimitations is completely inapplicable in thi6

case, since the Ohio law impoees no limita'

tion6 on the amount of campaiSn contribu'

tions.

74LE/l2d

isl compelling,"'

ra, supra, at 463,2

S Ct 1163 (quoting

.ampshire, 354 US

2d 1311, 77 S Ct

,ion concurring in

only if there is a

ron between the in-

and [an] overriding

ate interest." Gib-

islative Comm., gu-

N, 2d 929,83 S Ct

aleo this Court up

First Amendment

rcrting and disclo

r imposed on politi-

e Federal Election

197t.2 USC $431

i$ 431 et seq.). 424

L Ed 2d 659, 96 S

t found three gov-

i sufficient in gen-

.riring disclosure of

:erning campaign

expenditures:? en-

roters' knowledge

te's possible alle-

ests, deterrence of

he enforcement of

ations.6 The Court

', that in certain

' balance of inter-

rpting minor politi-

compelled disclo

ment's interests in

sures are "dimin-

32, 434, and 438 (1976

i $$ 432, 434 and 4381

commiltee to keep de-

contributions and ex-

;he names of campaign

rients of campaign dis-

r reports with the Fed-

sion which are made

interect in enforcing

:ly inapplicable in this

,aw imposes no limita-

of campaign contribu-

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS '74 CAMP. COMM.

459 us 87,74L Ed 2d 250, 103 s ct 416

frI,1; ;t,',l; iT.";JXffil dft'E;

irsS. n{iror party candidates "usu-

lI" r"p."."nt definite and publicized

Iewpoints" well known to the Pub-

lic, and the improbability of -their

winni.,g reduces the dangers of cor-

ruption and vote'buying. Ibid. At the

same time, the potential for impair-

ing First Amendment interests is

substantiallY greater:

[45e us e3]

"We are not unmindful that the

damage done bY disclosure to the

associational interests of the mi-

nor parties and their members

and to suPPorters of indePendents

could be significant. These move-

ments are less likelY to have a

sound financial base and thus are

more vulnerable to falloffs in con'

tributions. In some instances fears

of reprisal may deter contributions

to the point where the movement

cannot survive. The public interest

also suffers if that result comes to

pass, for there is a consequent

reduction in the free circulation of

ideas both within and without the

political arena." Id., at 7L, 47 L Ed

2d 405, 96 S Ct 1155 tfootnotes

omittedt.

We concluded that in some circum-

stances the diminished government

interests furthered by compelling

disclosures by minor parties does not

justify the greater threat to First

Amendment values.

Buckley v Valeo set forth the fol-

lowing test for determining when

the First Amendment requires ex-

empting minor parties from com'

pelled disclosures:

"The evidence offered need show

only a reasonable probability that

the compelled disclosure of a Par-

ty's contributors' names will sub-

ject them to threats, harassment,

or reprisals from either Govern-

ment officials or private Parties."

Id., at 74, 47 L Ed 2d 405, 96 S Ct

I 155.

The Court acknowledged that "un-

duly strict requirements of Proof

could impose a heavy burden" on

minor parties. Ibid. Accordingly, the

Court emphasized that "[m]inor par-

ties must be allowed sufficient flexi'

bility in the proof of injury." Ibid.

"The proof may include, for exam'

ple, specific evidence of past or

present harassment of members

due to their associational ties, or

of harassment directed against the

organization itself. A Pattern of

threats or specific manifestations

of public hostility may be suffi-

cient. Ne*' parties that have no

history upon which to draw maY

be

[45e us 94]

able to offer evidence of rePri-

sals and threats directed against

individuals or organizations hold-

ing similar views." Ibid.

[3a] Appellants concede that the

Buckley test for exempting minor

parties governs the disclosure of the

names of contributors, but they con'

tend that the test has no application

to the compelled disclosure of names

of recipienr-s of campaign disburse-

ments.e Appellants assert. that the

9. [3b] We believe that the question

u'hether the Buckiel test applies to the com-

pelled disclosure o1 recipients of expenditures

is properly before us. Throughout this litiga-

tic,n Ohit, ha-s maintained that i1 can constitu-

tionallr, require the SWP to disclose the

names of both campaign contributors and

recipients of campargn expenditures. ln inval-

idating both aspects of the Ohio statute a-s

applied to the S\"'P the District Court neces-

saril-v held (l I thal the Buckley standard.

which permits flexinie proof of the reasonable

probabilitl ol rhrr.,L.. harassment. or repri-

sals. appiies to botn contributions and expen-

ditures. and t2l thar the evidence was suffi-

cient to shorx' a rea-sonable probabilit;- that

257

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74LEd2d

State has a substantial interest in

preventing the misuse of campaign

funds.to They also argue thai tf,e

disclosure of the nameJof

[45e US 95]

of campaign funds will n";fli,iTf

nificant impact on First Amendmerit

rights, because, unlike a contribu-

tion, the mere receipt of money for

commercial services does not affir_

matively express political support.

lal We. reject appellants' unduly

narrow view of the minor-party ei-

emption recognized in Bucklev. Ar>

pellants'attempt to limit the exemp

tion to laws requiring disclosure of

contributors is inconsistent with the

rationale for the exemption stated in

Buckley. The Court concluded that

ttre government interests supporting

disclosure are weaker in the i""e oi

minor parties, while the threat to

First Amendment values is greater.

Both of these considerationi apply

not only to the disclosure of Cam-

paign contributors but also to the

disclosure of recipients of campaign

disbursements.

[5aJ Although appellants contend

that 'fQuiring disclosure of recipi-

ents of disbursements is neces"u.y'to

prevent corruption, this Court recos-

nized in Buckley that this co.r""i-

edly legitimate government interest

has less force in the context of mi-

nor parties. The federal law consid_

ered in Buckley, like the Ohio law at

issue here, required campaign com_

mittees to identify both- cimpaign

contributors and iecipients oi'..ii-pgign disbursements. 2 USC

l_$^13?Cl and (d) and 484(a) and (b) t2USpq $! a32(c) and (d) and a3a(a)

and (b)]. We stated that ,,bv exposins

large contributions and expenditureZ

to the light of publicity,,,-disclosure

requirements "ten[d] to ,prevent the

corrupt use of money to affect

elections."' Id., at 67,-46 L Ed 2d

659,.96 S Cr 612 (emphasis added),

glgt$g Burroughs v United States,

290 US 534,548,78 L Ed 484, 54 SCt 287 (1934). We concluded. how-

ever, that because minor party can-

d.idates are unlikely to win eleitions,

the government's general interest in

"deterring the 'buying' of elections"

is "reduced" in the case of minor

parties. 424 US, at 70, 46 L Ed 2d

659, 96 S Ct 612.')

disclosure would subject both contributors

and recipients to public hostility and harass-

ment. In their jurisdictional statement, appel-

lants appealed from the entire jud5rrneni en_

tered below and presented the folloning ques_

tion for review:

"Whether, under the standards set forth bv

this Court in BuckJe5. v Valeo. 424 tJS f : aOi

Ed 2d 6s9, 96 S Ct brt ,tgz6,. tf," piori"ionl

of Sections 3Sl?.10 and 3512.11 oi'tfre dfrio

Revised Code. u'hich require that th; ;;;_paign committee of a canciidate fo. p"Uii.

office 6le a reporr disclosing the full iameiard addresses of persons making

"ontii-[u-tlonE to or receiving expenditures from such

commlttee. are consistent n.ith the righr of

priy5]. of assocratron guaranreed b.v the First

ano rourteenth Amendments <.rf the Constitu,

tion of rhe Unirc{ Sures

",i.,e,.

oppIJ to-ile

committ€es of candidarcs of a minorin partv

which can establlsh onll iso.lared inr;n;;';i

harassment direcred toward the ,A;i;;;

258

or its members within Ohio during recent

.vears." Juris Statement i.

We rhink that the correctness of both hold_

ings of the District Court is ,.fairl_v includJ'

in the question presented in the jurisdictional

stat€ment. ThLs Qsu6,s Rule lS.ltat. See pro

cunier v Navarette, 494 US S55, Sbg, n 6, SSL Ed 2d 24. 98 S Ct 8S5 (1978r f,lolur porne.

to decide isaot limited by the precise t".-. of

the question presented").

I0. This is one of three government inter_

ests identi-fied in Bucklel' Appellants do not

contend that the other two interests, enhanc-

ing voters' abilit5. to evaluate candidates and

enforcing contribution limitations, supporl

the disclosure of the names of recipient. of

campaign disbursemen*.

. ll. [5b] The partial dissent suggesls thar

the government int.erest in the disclosure oj

recipients of expenditures is not significantll.

dirninished in the case of minor poiitical par.

ties. since parties *ith little theilfrood of

74 LM 2d

osure of recipi-

s is necessary to

ihis Court recog-

rat this conced-

rrnment interest

e context of mi-

leral law coneid-

rthe Ohio law at

campaign com-

both campaign

cipients of cam-

ents. 2 USC

434(a) and O) [2

I (d) and 434(a)

hat "by exposing

md expenditures

icity," disclosure

] to 'prevent the

roney to affect

67, 46 L Ed 2d

lmphasis added),

v United States,

ILEd484,54S

concluded, how-

ninor party can-

to win elections,

rneral interest in

ing' of elections"

e case of minor

70, 46 L Ed 2d

Ohio during recent

,ectness of both hold-

t is "fairly included"

I in the jurisdictional

Rule 15.1ta). See Pro

US 555, 559. n 6, 55

(1978) ("[O]ur power

v the precise terms of

ee government inter-

'y Appellants do not

wo interests, enhanc-

.luate candidates and

limitotions, Bupport

rmes of recipients of

dissent Buggests that

in the discloeure of

r is not aigniicantlY

,f minor political par-

r little likelihood of

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS'74 CAMP' COMM'

459 us 87.74LEd2dzfi' 103 s ct 416

[46e us 96]

Moreover, appellants seriously un'

aerstot" the threat to First Amend'

ii""t "igttt

that would result from

iluirinE minor parties to disclose

it e tecipi"nts of campaign disburse'

ments'

t'169 us 9zl

ExPenditures bY a Political

perriy often consist of reimburse-

ments, advances, or wages Paid to

party members, camPaign workers,

and

-supporters,

whose activities lie

at the very core of the First Amend-

ment.r2 Disbursements maY also go

to persons who choose to exPress

their support for an unpopular cause

by ptorridi.rg services rendered

sca.ce by public hostility and suspi-

cion.ts Should their involvement be

1

r

tt

aI

E

s

f

3I

I

Ti?

clectoral Eu@ess might neverthelees finance

Iio-p". campaign activities merely to gain

6q;ition. Post, at 109-110. 74 L EA %l' at

l6a-t't" partial dissent relies on Justice

Wttit 't BeParate opinion in Buckley, in which

he pointed out that "unlimited money tempts

*o-ole to spend it on whatever money can

f,,nj to it fl.rence an election." 424 US' at 265'

le-L na 2d 659, 96 S Ct 612 (emphasis in

original).

An examination of the cont€xt in which

.lustice- Whit€ made this observation indicates

iilUf, why the state interest here is insub-

i;ti;il Justice White was addressing the

constitutionality of ceilings- on cam.Pargn l:x-

oenditures applicable to all candldat€s rrts

;;i ;* that such ceilings "could plav a

LiUsta"tiat role in preventing unethica) prac'

ti"o.; fUia. ln the case of minor parties'

ho*".r"., their limited financiai resources

;;; ;'a built-in expenditure ceiling which

-i"i-i*t the likelihood that they wjll ex-

oenJ substantial amounts of money to finance

i-oi"o"t campaign activities See id'' at 7l'

46i Ed 2d 650, m s o 612. For example' far

f-- fr""it g 'iunlimited money," th9

-OI!9

SwF fr"" hid an average of roughly $15'000

available each year to spend on its e-lection

efforts. Most of lhe Iimited resources of minor

*.tG Utt typically be needed to pay for the

6.din..-u fixed- costs of conducting campaigns'

a.at

""-

filing fees, travel expenses, -and..the

"ip"""o

incrlrred in publishing and distribut'

i.i "t-p"ign

literature and maintaining of-

6ces. Thus Justice White's obsen'ation that

'i6t ancing illegal actirities is lo*' on the cam-

*i* o.r-""irition's priority list," id ' at 265'

is "f. Pa-za 659, 96 S Ct 612' is particularlv

;p*t," in the case of minor parties We

cannot agree, therefore, that minor parties

"." ""

fiX'"ly as major parties to make .signi-6-

cant expeniitu.es in funding dirty tricks or

other improper campaign activities' See polt'

at 110, il L pa 2d, at 2ffi Moreover' the

expenditure b1' minor Parties of even a sub

stantiat portion of their limited funds on

illegal activities would be unlikely to have a

gubetantial impact.

Furthermore, the mere possibility that mi

nor parties will resort to corrupt or unfair

tactics cannot justify the substantial infringe

ment on First Amendment interests that

would result from compelling the disclosure of

recipients of expenditures. ln Buckley, we

acknowledged the possibility that- supporters

of a majoi party candidate might channel

money into minoi parties to divert votes from

other major party contenders, 424 US' at 70'

46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S Ct 612, and that, as

noted by the partial dissent, post, at-110, and

n 5,74 L Ed 2d, at 266, occasionally minor

parties may affect the outcomes of elections'

We thus recogrrized that the distorting influ-

ence of Iarge contributors on elections may

not be entirily absent in the context of minor

parties. Nevertheless, because we concluded

ihut th" government interest in disclosing

contributors is substantially reduced in the

case of minor parties' we held that minor

parties are entitled to an exemption from

iequiremenl" that contributors be disclosed

where they can show a reasonable probability

of harassment. 424 US, at 70, 46 L Ed 2d 659'

96 S Ct 612. Because we similarly conclude

that the government interest in requiring the

disclosurJ of recipients of expenditures is sub-

stantially reduced in the case of minor par-

ties, we hold that the minor-party exemption

recognized in Buckley applies to compelled

discl,osure of expenditures a.-s well.

12, For texample' the expenditure 6tate'

ments filed by the SWP contain a substantlal

percentage oi entries designarcd as per diem'

iravel expenses, room rental, and so on The

Ohio staiute makes it particularly easy to

identify these individuals since it requires

disciosure of the purpme of the disbursemenls

a--. weII as the idintitv of the recipients Ohio

Rev Code Ann $ 3517.1OBX5Xct (Supp 1981)'

13, "'[F]inancial transactions can reveal

much about a person's activities. associations'

and beiiefs.'" Bucklel v Valeo, 424 US' at 66'

46 L Ed 2d 659. 96 S Ct 612, quoting Califor-

nia Bankers Assn. v Shultz,416 US 21' 78-79'

39 L &t 2d 812.94 s ct 1494 \L974) (Powell,

259

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74LEd2d

publicized, these persons would be as

vulnerable to threats, harassment,

and reprisals as are contributors

whose connection with the party is

solely financial.t. Even indivlduals

[45e US 98]

who receive disbuisements for

"merely" commercial transactions

may be deterred by the public en-

mity attending publicity, and those

seeking to harass may disrupt com-

mercial activities on the basis of

expenditure information.16 Because

an individual who enters into a

transaction with a minor party

purely for commercial reasons lacks

any ideological commitment to the

party, such an individual mav well

be deterred from providing services

by even a small risk of harassment.r6

Compelled disclosure of the names of

such recipients of expenditures could

therefore cripple a minor party's

alility to operate effectively ."a

thereby reduce "the free circulation

of ideas both within and without the

political arena." Buckley, 424lJS, at

7L. 46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S Ct 612

(footnotes omitted). See Sweezy v

New Hampshire, 954 US, at iSC_

257, 7 L Ed 2d L31L,77 S Ct 1203(plurality opinion) ("Any interfer-

ence with the freedom of a party is

simultaneously an interference with

the freedom of its adherents',).

[6] We hold, therefore, that the

test announced in Buckley for safe-

guarding the First Amendment in_

terests of minor parties and their

members and supporters applies not

only to the compelled disclosure of

campaign contributors but also tothe compelled disclosure of recipi-

ents of campaign disbursements.

III

[7a] The District Court properly

applied the Buckley test to fhe facts

of this case. The District Court found

"substantial evidence

[45s US 99]

mentar and privat" .::Ifl:l i:f;f;

J-., concurring). The District Court found thar

the Federal Bureau of lnvestigation tFBfL ai

least until 1926 routinely investlgated the

financial transactions of ine SWp"ana f...i

track of the payees of SWp checks.

14. The fact that some or even man-v recipi-

ents of campaigrr expenditures may- not L

exposed_to the risk of public hostilitl: does not

detract from the serious threat to the exercise

of First Amendment rights of those rnho aie

so exposd. We cannot agree with the partial

dissent's assertion that disclosu.". of aii_

bursements paid to campaiglr *orkers and

support€rs will not increase the probabilitv

that the). will be subjected to harassm"nt.na

hostility. Post, at 11f-112, ?4 L Ed Za, at iel.Apart from the fact that individuals mar.

work for a candidate in a variet.r. of r*.av."

without publicizing their involvement. the

application of a disclosure requirement re-

sults in a dramatic increase in public expo-

sure. Under Ohio law a per6on's affiliation

with the party will be recorded in a document

?.ffi

that must be kept open ro inspection by any

one who u.ishes to examine it for a p".ioa oiat least six .years. Ohio Rev Code Ann

S35l7.fqc) (Supp 1981r. The preservation of

unorthodox political affiiationi in public re_

cords substantiall.r, increases the potential for

harassment above and beyond the risk that

an individual faces simply as a result of hav-rng worked for an unpopular pany at one

tlme.

15. See, e.g., Sociaiist Workers partv v At_

l{lney Ge}eral, 458 F Supp 895, 904 rSOXf'

1978r (FBf inrerference ".ltt SWp trauel ai_

rangements and speaker hall rentalt. vacatedon other grounds, 596 F2d Sg (CA2), ceri

!e$ed,444 US 90s,62 L Ed 2d r4r. 100 S-a;

21? t.1979).

16. Moreover, it would be hard to think of

man_v instances in r.r,hich the state interest inpreventing

.vote-bu1.ing anC in,nroper cam.paign activities *'ould be furthered br thr

disclosure of pavment. for routine .n-rn"..iri

seruces.

74 LEd 2d

i59, 96 S Ct 612

). See Sweezy v

354 US, at 250-

1L,77 S Ct 1203

("Any interfer-

lom of a party is

interference with

rdherents").

erefore, that the

Buckley for safe-

; Amendment in-

rarties and their

orters applies not

lled disclosure of

tors but also to

:losure of recipi-

rsbursements.

I

t Court properly

y test to the facts

strict Court found

ce

s egl

of both govern-

l hostility toward

r to inspection by any

nine it for a period of

)hio Rev Code Ann

). The preservation of

iliations in pubiic re

rases the potential for

beyond the risk that

cly as a result of hav-

popular party at one

Workers Party v At-

Supp 895, 904 (SDNY

with Sl*P travel ar-

r hall rentalt, vacated

F2d 58 (CA2). cert

LEd 2d 141. 100 S Cr

d be hard to think of

h the state interest in

and improper cam-

be furthered bl the

or routine commercial

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS'74 CAMP' COMM'

459 US 87 . 7 4 L Ed %l 250, 103 s ct 416

and harassment-- of SWP members

;J BupPoryT'" APPellees intro-

;r*d pi-oof of sPecific incidents of

l;vate- and government hostility to

;rrd the SWP and its memhr€

-itfri" the four years Preceding the-

;rt"]. These incidents, many of

*fri.f, occurrd in Ohio and neigh'

Uoarrg States, included threatening

"f,ot

J calls and hate mail, the burn'

ing of SWP literature, the destruc'

tiJn of SWP members' ProPerty, PG

lice harassment of a party candidate,

*a tn" frring of shots at an SWP

o6"". Th".e was also eYidence that

io tt " l2-month period before trial

22 SWP memhrs, including 4 in

Ohio, were fired because of their

Dartv membership. Although appel-

-Iants

contend that two of the Ohio

firings were not PoliticallY moti-

vated, the evidence amPlY suPPorts

the District Court's conclusion that

"orivate hostility and harassment

to*ard SWP members make it diffi-

cult for them to maintain emPloY-

Bgnt."

The District Court also found a

past history of Government harass-

ment of the SWP' FBI surveillance

of the SWP wa-" "massive" and con-

tinued until at least 1976. The FBI

also conducted a counterinteliigence

program against the SWP and the

Young Socialist Alliance (YSA), the

SWP's youth organization. One of

the aims of the "SWP DisruPtion

Program" was the dissemination of

information designed to impair the

ability of the SWP and YSA to func-

tion. This program included "disclos-

ing to the press the criminal records

of SWP candidates, and sending

anonymous letters to SWP members,

supporters, spouses, and emPloY-

ers."t7 Until at least 1976, the FBI

employed various covert techniques

to

[450 Us 100]

obtain information about the

SWP, including information concern-

ing the sources of its funds and the

nature of its expenditures. The Dis'

trict Court specifically found that

the FBI had conducted surveillance

of the Ohio SWP and had interfered

with its activities within the State.rs

Government surveillance wa-s not

limited to the FBI. The United

States Civil Service Commission also

gathered information on the SWP,

the YSA, and their suPPorters, and

the FBI routinely distributed its re-

ports to Army, NavY and Air Force

Intelligence, the United States Se-

cret Service, and the Immigration

and Naturalization Service.

ITbl The District Court ProPerlY

concluded that the evidence of pri-

vate and Government hostilitY to-

ward the SWP and its members es-

tablishes a reasonable probability

that disclosing the names of contrib-

utors agd reciPients will subject

them to threats. harassment, and

17. The District Court was quoting from

Part I of the Final Report of Special Master

Judge Breitel in Socialist Workers Party v

Atrorney General of the United States, 73 Civ

3160 (TPG) (SDNY, Feb. 4. 198O), detailing

the United States Government's admissions

concerning the existence and nature of the

Crovernment sun eillance of the SWP.

f& The District Court aleo found the follow'

tn8

-The Government possesses about 8,000,0O0

dauments relating to the SWP, YSA . . . and

their members. Since 1960 the FBI has

had about 300 informants who were members

of the SWP and/or YSA and 1,000 ncn'mem'

ber informants. Both the Cleveland and Cin-

cinnati FBI field offices had one or more SWP

or YSA member informants. Approximatell'

2l of the SWP member informants held Iocal

branch offices. Three informants even ran for

elective o6ce as SWP candidates The 18

informants whooe files were disclosed to

Judge Breitel received total pa1'ment.s o-f

S358,648.38 for their services and expenses."

(Footnotcs omitted.)

zlil

U.S. SUPREME @URT REPORTS 74 LEd 2d

repriaals.re There were numeroue in-

etances of recent harassment of the

SWP both in Ohio and

[450 US rou

states.r There was also .or.il"?lti:

evidence of pa3t Government harass-

ment. Appellants challenge the rele

vance of this evidence of Govern-

ment harassment in light of recent

efforts to curb official misconduct.

Notwithstanding these efforts, the

evidence suggests that hostility to-

ward the SWP is ingrained and

likely to continue. All this evidence

was properly relied on by the Dis-

trict Court. Buckley, 424 US, at 74,

46 L Fd 2d 659,96 S Ct 612.

.ry

[1b] The First Amendment prohib.

its a State from compelling disclo

sures by a minor party that will

subject those persons identified to

the reasonable probability of threats,

harassment, or reprisali. Such dis-

closures would infringe the

[459 US 102]

First

Amendment rights of the party and

its members and supporters. In light

of the substantial evidence of past

and present hostility from private

persons and Government officials

against the SWP, Ohio's campaign

disclosure requirements cannot be

constitutionally applied to the Ohio

swP.

_.The judgment of the three-judge

District Court for the Southern Dis-

trict of Ohio is affirmed.

It is so ordered.

19. After reviewing the evidence and the

applicable law, the District Court concluded:

"[fJhe totality of the circumstances estab-

lishes that, in Ohio, public disclosure that a

person is a member of or has made a contr!

bution to the SWP would create a reasonable

probability that he or she would be subjected

to threats, haraesment or rneprisals.,' T}re Dis-

trici Court then enjoined the compelled disclo

sures of either contributors' or recipients'

names. Although the District Court did not

expreasly refer in the quoted passage to dis-

cloeure of the names of recipients of campaign

.tiobursements, it is evident from the opini6n

that the District Court was addressing both

contributors and recipients

-

ZO. [7c] Some of the recent episodes of

!!_Ift", harnmment, and reprisals against the

SWP and its members occurred o'utside of

Ohio. AntiSWP occurrences in places such as

Chicago (Sl{P ofrce vandalized) and pitts-

burgh (shot fired at SWP building) are cer-

tainly relevant to the determinatlon of the

public's attitude toward the S\{p in Ohio. In

Buckley we etated that "[n]ew parties that

have no \bm.y upon which to draw rnay . . .

offer evidence of reprisals and threaL di-

rected againsi individuals or organizations

holding simitar views." 424 US, at 74, 46 L Ed

2d 659. 96 S Cr 612 Surely the Ohio SWp

262

may ofer evidence of the experiences of other

chapters espousing the samC political philoso

phy. See 198O Illinois Socialist Workers Cam-

paign v State of Illinois Board of Elections,

531 F Supp 915, 921 (ND nl 1981).

Appellants point to the lack of direct evi-

dence Iinking the Ohio statute's disclosure

requirements to the harassment of campaign

contributors or recipients of disbursements. In

Buckley, however, we rejected such ,,unduly

strict requirements of proof' in favor of .,flexi-

bllrJr in the proof of injury." 424 lJS, at 74,

46 L &l 2d 659,96 S Ct 612. We thus rejecred

requiring a minor party to "come forward

with witnesses who are too fearful to contrib.

ute but not too fearful to testify about their

fear" or prove that "chill and harassment

[are] directly attributable to the specific dis-

cloeure from thich the exemption is sought.,,

Ibid. We thinf that these considerations are

squal-ly applicable ro the proof required to

establish a reoqonable probability that recipi-

ents will be subjected to threats and harass-

ment if their names are disclosed. While the

partial dissent appears to agree, post. ar 112-

113, n 7, 74 L U 2A. at 269-270, its .,sepa_

ratel)' focused inquiry," post. at 112, and n Z,

74 L M ?d, at 269 in reality reguires evidence

of chill and harassment directly attributable

to the expendituredisclosure requirement.

74LEd 2d

:ompelling disclo-

party that will

ons identified to

nbility of threats,

prisals. Such dis-

inge the

I r02l

First

of the partY and

.rpporters. In light

evidence of Past

lity from Private

,ernment officials

Ohio's camPaign

ments cannot be

rplied to the Ohio

rf the three'judge

the Southern Dis-

rmed.

he experiences of other

: same political Philoso

Socialist Workers Cam-

ois Board of Elections'

ID Ill 1981).

the lack of direct evi'

do statute's disclosure

rarassrn€nt of camPaign

nts of disbursements. In

rejected such "undulv

oroof in favor of "flexi-

inju.y." 424 US, at ?4,

)t 612. We thus rejected

artv to "come forward

'e to fearful to contrib-

rl to testify about their

"chill and harassment

able to the sPecific dis-

re exemPtion is eought "

ihese considerations are

the proof required to

r probabilitY that reciPi-

I to threats and harass-

are disclosed. While the

s to agree, Post, at 112-

l, al 269-270 it^s "sePa'

;," post.at 112. arrd n 7'

realitl' requires evidence

ent dlrectl]' attributablt

;closure requrrement

I ioin Parts I, III, and fV of the

c;fi;'r;i"ion and agxee with much

^f what is said rn Part II' But I

;r;il;gt"e, with the Court or with

ffi;';;tr"i dissent, that we should

Ii"f,Jr," issue whether a standard

lri-ri-i am"rent from that aPPlied

i.'ait.r*"re of campaign -contribu'

IiorJtr,o"td be applied to disclosure

-r"'""tt"p"ig" diibursements' See

;'t;;il:" s,74LEd 2d' at251-

isi]'*",, at Ll?'113, t 7' 71.! N

-il|,'

"i-

iSS-270.r Appellants did not

fibU;; tr," oiit'ict court that

lffitu"t standards might aPPIY- Nor

was the issue raised in aPPettants

irI"ii"iio"al statement or in their

ir;;a;" the merits in this Court'

&nsequentlY, I would merelY as'

iie'to, PurPoses of our Present

i-*iti""-ti appellants apparently

i"r"-""""-ed throughoqt this litiga-

iion and as the District Court clearly

"*"-J-that

the flexible P:oof ryl-"

;*il;kl"y v Valeo, 424 Uq-l' 46 L

rfo-za 65-9, 96 s ct 612 (1976)' aP-

ofl* "q""tly

to forced disclosure of

Io"ttiU"tions and to forced disclo

t"i" of expenditures' I would leave

foi

-a"ott ei daY, when the issue is

.q"*"tY Presented, considered bY

G"-.o"*i below, and adequatelY

briefed here, the significant question

that now divides the Court'

This Court's Rule 15'1(a) states:

"Only the questions set forth in the

;urisdiction.l strt"-et't or fairly in'

cluded therein

"Whether, under the standards

set forth bY this Court in BuckleY

, valeo, 4i4 uS 1 t46 L Fd 2d 659'

96 S Ct 612l (19?6), the Provisions-

of Sections 3517.10 and 3517'11 ot

ihe Ohio Revised Code, which re-

ouire that the camPaign commit-

te- of a candidate for public ofhc-e

file a rePort disclosing

-

the tull

names and addtesses of Persons

r".t l"g contributions to or receiv-

ing eiPenditures .from such com-

mitte", """ consistent with the

ti*frt

'of

PrivacY of association

s;aratteed- bY the First and Four-

["""tt Amendments of the Consti-

iutio" of the Unit'ed States when

"rofi"a

to the committees of candi-

a-"["t of a minoritY PartY which

*" establish onlY isolated - in-

stances of harassment directed to'

ward the organization or its mem-

bers within- Ohio during recent

years." Juris Statement i'

The ouestion assumes the applicabil-

itv "ig;.Lfey

to the entire case' and

"Ju

trri. bourt to decide onlY

*t

"tt "t the evidence Presented to

u"J fr.rt found by the District Court

;;;" sufficient to suPPo4 !!tt

"o".t't

conclusion that the Buckley

test was satisfied.

Abse'nt extraordinarY circum-

tt *"., this Court does not decide

i""""" beyond those it has agreed to

;;;;. I(4"yo. v Educational Equgl-

iw L"*"""415 US 605, 623' 39 L Eq

ii oioi ga s ct 1323 $e7$: united

SL;t v Bass, 404 US 336, 339' n 4'

5o i, oa 2d 488, 92 s ct 515 (1971);

CL*t"f Talking Pictures C-o' v

Justice

part and

ment.

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS'?4-CAMP' COMM'

459 US 87,74LEd 2d 250' 103 S Ct'116

SEPARATE OPINIONS

Blackrnun, concurring in tional statement presented a single

-.on"o"titg in the judg- question:

the

1459 us l03l

will be considered bY

Appellants' jurisdic'

l. Although the partial dissenr agrees-that

Orit G"; is-not properly presented.and there

fore that the question ehould not be declded'

Dost. at 112-113, n7.74L Ed 2d' at 269-270 '

io l*trt- tta reasoning endorse a different

stst dard of Proof. See n 2' infra'

263

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 74LEd2d

Western Electric Co., 304 US 175,

17&179, 82 L Ed L2t3, 58 S Ct 849

(1938). According to the Court, how-

ever, the issue whether the flexible

standard of proof established in

Buckley applies to recipients of ex-

penditures Is "'fairly included' in

the question presented." Ante, at 94,

n 9,74 L Ed 2d, at 258. But appel-

lants' failure to present the issue

was not a mere oversight in phras-

ing that question. That appellants

did not invoke this Court's jurisdic-

tion to review specifically the proper

standard for disclosure of campaign

expenditures is also apparent from

appellants' arguments in their juris-

dictional statement and their brief

on the merits. In their jurisdictional

[t159 US 104]

statement, under the heading "The

Question is Substantial," appellants

stated:

"The standards governing the

resolution of actions involving

challenges to reporting require-

ments by minority parties were

eet forth by this Court in the case

of Buckley v Valeo, 424 US 1 [46 L

Ed 2d 659, 96 S Ct 6121 (1976). In

Buckley the Court held that in

order to receive relief from report-

ing requirements such as those at

issue in this action a minority

party must establish '. a rea-

sonable probability that the com-

pelled disclosure of a party's con-

tributors' names will subject them

to threats, harassment or reprisals

from either Government officials

or private parties.' 424 US, at 74

[46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S Ct 612]."

Juris Statement 10.

Appellants went on to state that the

flexible standard of proof of injury

established in Buckley applied to

"disclosure requirements." Juris

Statement L2-13. Similar assertions

are found in appellants'brief on the

2U

merits. See Brief for Appellants 12

("Summary of'Argument"); id., at 18

("While refusing to grant minority

parties a blanket exemption from

financial disclosure requirements,

the Court in Buckley established a

standard under which they may ob-

tainrelief .. ").

Thus, appellants' exclusive theme

in the initial presentation of their

case here was that the District Court

erred in finding that the Buckley

standard was satisfied. They did not

suggest that the standard was inap

plicable, or applied differently, to

campaign expenditure requirements.

It was not until their reply brief,

submitted eight years after this suit

was instituted and at a time when

appellees had no opportunity to re-

spond in writing, that appellants

sought to inject this new issue into

the case. See Irvine v California, 347

us 128, 129, 98 L Ed 561, ?4 S Ct

381 (1954) (plurality opinion of Jack-

son, J.). In my view, it simply cannot

be said that it was "fairly included"

in the jurisdictional statement.

Moreover, "[w]here issues are nei-

ther raised before nor considered lby

the court belowl, this Court will not

ordinarily

[459 US 105]

consider them." Adickes v

S.H. Kress & Co., 398 US 144, L47, n

2, 26 L Ed 2d 742,90 S Ct 1598

(1970); Lewn v United States, 355

US 339, 362-363, n 76, 2 L Ed 2d

327, 78 S Ct 311 (1958). The District

Court did not address the question

whether some standard other than

that developed in Buckley should

appll' to disclosure of campaign ex-

penditures The reason for this

that appeliants conceded in the

trict Court. as they concede here,

that the "flexibility in the proof of in-

jury" applicable to disclosure of con-

was

Dis-

BROWN v SOCIALIST WORKERS'?-4-CAMP' COMM'

459 us 87 ,74 L FA %) zfi, 103 s ct 41674LEd 2d

rr Appellants 12

ment"); id., at 18

r grant minoritY

exemption from

e requirements,

Iey established a

ich they may ob

exclusive theme

entation of their

bhe District Court

hat the BuckleY

ied. They did not

andard was inaP

d differently, to

ure requirements.

their reply brief,

ars after this suit

at a time when

rpportunity to re-

that appellants

ris new issue into

: v California,347

Ed 561, 74 s ct

y opinion of Jack-

r, it simply cannot

; "fairly included"

.l statement.

-.re issues are nei-

nor considered [bY

his Court will not

s l05l

r them." Adickes v

t98 us 144,147, n

42, 90 s ct 1598

Inited States, 355

n16,2LEd2d

1958). The District

lress the question

rndard other than

r Buckley should

e of campaign ex-

eason for this was

nceded in the Dis-

rey concede here,

y in the proof of in-

o disclosure of con-

tritrutors governed the entire case'

::#';t*;iS*t"tiI'xltl;.f;

Ir**m,ffi:r:l;trl.x*'"Jsil

m'lt*,^r ;frili'.'ffi- #?1

;;ti that "evidence of Past- ha-

?r*rn""t maY be Presented bY Plain-

,iF"- i" cases such as the instant

il"." D"f"tdants' Post-Trial Memo

randum 4-5'

This case Presents no extraordi-

.or*, circumstances justifying devia-

i'ion ftorn this C,ourt's Rule 15'1(a)

""J

it" long+stablished practice- re'

il"ti"g issues not presented U"-loY

ff;- h;" deviated from the Rule

wfren jurisdictional issues have been

"-itt

it bY the Parties and lower

@utts, see, e' g., United States v

S;;"; Broadcasiins e,o', 351 U]S 1-9-2r

rgi.-roo L Ed 1081, 76 s ct 763

tfgSel, or when the Court has no

ii""a ;'pl"io error" not assigned' see

6r*"t"* v United States, 330 US

srii, +t2,91 L Ed 973, 67 s ct zil

OgiZl. (ibviouslv, the issue that di

vides the Court from the partial djs'

eent is not jurisdictional' Nor, as the

Court's opinion persuasively demon-

strates, is application of the Buckley

t€st to disclosure of campaign dis-

Uursemen* "plain error'" Indeed, I

consider it quite possibie that, after

full consideiation, the Court would

adopt the BuckleY standard in this

coniext for the reasons stated by the

Crcurt. I also consider it quite possi

ble that, after full consideration, the

Court might wish to revise the Buck-

ley standard as applied to campaign

disbursemenLs-perhaps to take ac-

count of the different types of expen-

ditures covered and their differing

impacts on associational rights,- or

peit.ps along the lines suggested .in

It " p"*i"t d-issent. But this signifi-

cant constitutional

[45e us tTl.i'ion

should

not be made until the question is

properly presented so that the rec-

ord- iniludes data and arguments

adequate to inform the Court's judg-

ment.

The Court's aPParent reliance on

Procunier v Navarette, 434 US 555'

560, n 6,55 L Ed 2d 24,98 S Ct 855

(19i8), does not provide a rationale

for deciding this issue at this time'

The petitioner there had included in

his petition for certiorari all the

o,resiio.rs we eventuallY decided'

Notwithstanding the fact that the

Court limited its grant of the peti-

tion to a single question, the parties

fully briefed the questions on which

,"ri"ro had been denied' Deciding

those questions, therefore, was nei-

ther unwise nor unfair' In this case'

in contrast, appellants affirmatively

excluded the point at issue in their

jurisdictional statement and in their

trief on the merits. BY faiiing to

raise it until their reply briel appel-

Iants prevented appellees from.re-

sponding to the argument in writing'

Th""" &n be no question that' as

the Court observes, "'our Power tn

decide is not limited by the precise

t r*a of the question Presented'' "

Ante, at 94, n 9, 74 L Ed 2d, at 258

(ouotine Procunier v Navarette, 434

Ui, rtioo, t 6,55 L Ed 2d 24,98 S

Ct 855, (emPhasis suPPlied)' P't

Rule 15.l(a) is designed. as a pruden-

tial matter, to prevent the possibility

that such tactics wiII result in ill-

considered decisions. It is cases Iike

this one that show the wisdom of the

RuIe.

Thus, for PurPoses of this case' I

would as;sume, as appellants' .iuris'

dictional statement and brief on the

merits assume, that the BuckieY

standard applies to campaiga expen-

285

fi'

U.S. SUPREME C,oURT REPORTS 74LEd2d

ditures just as it applies to contribu-

tions.t Appellees

[459 US 107]

presented "specific

evidence of past or present harass-

ment of members due to their associ-

ational ties; or of harassment di

rected against the organization it-

self," sufficient under the rule in

Buckley to establish a "reasonable

probability" that the Ohio law would

trigger "threats, harassment, or re

prisals" against contributors. 424

US, at 74, 46 L Ed 2d 659, 9G S Ct

612. On this basis, I would affirm the

judgment of the District Court in its

entirety.

Justice O'Connor, with whom

Justice Rchnquist and Justice Ste-

vens join, concurring in part and

dissenting in part.

I concur in the judgment that the

Socialist lVorkers Party (SWP) has

sufficiently demonstrated a reason-

able probability that disclosure of

contributors will subject those per-

sons to threats, harassment, or repri-

sals, and thus under Buckley v Va-

leo, 424 US 1, 46 L Ed 2d 659, 96 S

Ct 612 (1976), the State of Ohio can-

not constitutionally compel the dis-

closure. Further, I agree that the

broad concerns of Buckley apply to

the required disclosure of recipiLnts

ef sempaig-n expenditures. But, as I

view the record presented here, the

SWP has failed to carry its burden

of showing that there is a reasonable

probability that disclosure of recipi-

ents of expenditures will subject the

recipients themselves or the SWP to

threats, harassment, or reprisals.

Moreover, the strong public interest

in fair and honest elections out-

weighs any damage done to the asso-

ciational rights of the party and its

members by application of the

State's expenditure disclosure law.

[459 US loE]

I

Buckley upheld the validity of the

Federal Election Campaign Act of

1971, which requires the disclosure

of names of both contributors to a

campaign and recipients of expendi-

tures from the campaign. Buckley

recognized three major governmen-

tal interests in disclosure require.

ments: deterrence of corruption; en-

hancement of voters' knowledge

about a candidate's possible all,e-

giances and interests; and provision

of the data and means necessary to

detect violations of any statutory

limitations on contributions or ei-

penditures. The precise challenge

that the Buckley Court faced, how-

ever, was the overbreadth of the

Act's requirements "insofar as they

?: fr" partial dissent says it agrees that

"this i6 not the appropriate case to determine

whether a diferent test or gtandard of proof

should be employed in determining the consti-

tutional validity of required disclosure of ex-

pendrtures." Post, at llL, n ?, ?4 L Ed 2d, at

2q9 If that is ao, however appellees' proof.

which the partial dissent agrees establisired a

reasonable probability of threats, harqsment,

or repriaals against contributors. likewise al-

lowed the District Court to find a reasonable

probability of threats, harassment. or repri-

sals against recipients of expenditure. 'ih"

B-uckl_ey etandard permits proof that a partic-

ular discloeure creat€s the requisite likelihmd

of harassment to be based on a showing of

zffi

haraesment directed at members of the party

or at the olganization itrr,lf . 424 US, at ?4, 46

L Ed tut S9. 96 S Ct 612. Thus, I do not

understand how the partial dissent's ',sepa.

rately focused inquiry" can "plainly require a

different reeult," pct, at 1lB. n 7, il t ga U.