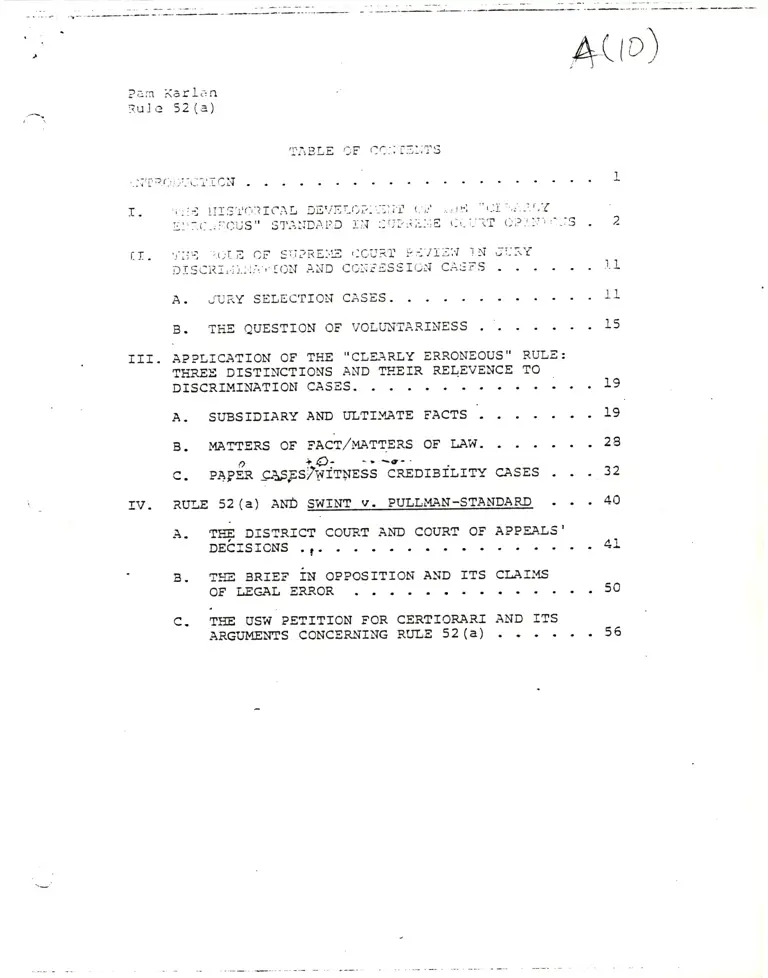

Annotated Memorandum from Karlan on "Clearly Erroneous" Rule

Working File

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Annotated Memorandum from Karlan on "Clearly Erroneous" Rule, 1985. 28a87cd3-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/90fc46ff-6286-42a1-93af-9b801d915bc6/annotated-memorandum-from-karlan-on-clearly-erroneous-rule. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

Pam XarI--o

F.ui e 52 (a)

I. r::i IIlS'r'rj.?IC.l L Di'jEr-i?-":'r-'r {r,r' ..,.'!l "t-'-f r"'-1. -'r''4

r;l':.(,-,:.()us" sl.;IIDAF.D ii.{ lli;-?,ii:-., E r-r-:-'iT (1 ) r:l-t r--:s

l.T. . ,r ij-; :(rr_ E OF Sii.rREilE rlC,UR'I' P:- /r.-li'I i t{ ,11--.-r'f

D I S Ciir.': r.l. i.::',' l ()N p.i'iD C (-11i.: dS S I (-r{ C'\ S F'5

A. JUP.Y SELECTIO}I CASES. .

B. TE1E QUESTION OF VOLIATTARINESS

III. APPLICATION OF THE "CLEARLY ERRONEOUS" RULE:

THREE DTStINCTTONS AND tI{ErR REI{EVENCE TO

A. SUBSIDIARY AND ULTI:YATE FACTS .

B. MATTERS OF FACT,/MATTERS OF I.AW.

o iO' rrre''

c. P4PEIR -A$FSltlijTNESS CREDTBTLITY CASES

IV. RULE 52 (A) ANb SWTNT V. PULLI'IAN'STANDARD

A. gEE DISTS.ICT COIIRT A!{D COURT 08 APPEALS,

DECTSTCNS .,.

B. THE BRIET i}I OBPOSITION AND ITS CI,AIT4S

OF I.EGAL ERROR

C. IIIE USW PETITION POR CERTIORARI AND ITS

ARGUIVIEI{TS CONCERNING R'TILE 52 (A)

EdL D)

2

.1.1

1I

l5

19

19

28

32

40

.4L

50

56

a_..,

' I Before the adoption of Fed.R.Civ.P. 52(a) , the scoPe of an

-' appellate court's power to review a trial court's findings depended

on whether the case involved sounded in 1aw or in equity- The

Seventh Amendment's provision that'no fact tried by a jury shal1 be

otherwise reexamined in any Court of the United States than according

, to the rules of common ]aw" was expanded over the years to include

ven .non-jury cases when they involved cornmon law issues, and the

factual finCings of a trier of fact were held nearly inviolate.

.UnLess the error had been truly egregious, a finding of fact was

very rarely overt,urned. fn ec.uity c,?::es, appellate courts had a

relative).y free l-.::rd in rcvi,;-r.;i;',g l-,r:,Lh;ir,lt'.::rs r:f fact and -ilatLcrs

of 1;w. p,u1e 52(a),;hich sul-c?rsc.jtd 'r:,oth t.he o.r-rJ larv and equity

s..a:-,,larCs, did i-rot even:.lrircss firidings of larv, in regard to "rhich

,. Eppel Lete cour ts r €:.ii:'re,l f r,le to ,:ver r ule tr ia1 courts' Ceterminaticrls '

fn regard to -fin,Ji;rgs of fact, it leai-,e,1 somewhat totrard the o1d

cornmon-law s'uai.Card: "Findin'js of f act shal1 not be set aside

unless clearly erroneous, and due regard sha1l be given to the

opportunity of the trial court to judge of the credibility of the

witnesses. " Ferl.R-Civ.P. 52(a) 2A U'S'C' What I hope to io in this

irremo is: ( I) Trace the developnrent, in the Supreme Court, of ihe

,,c1ear1y erro:^=ous" standard; (II) Examine Supreme Court Cecisions

in two ccnstituticnal areas (A) Jury Discr imina'.ion and

(B) Conf essi,)n cases -- to see what l ight the Court'S scandaris ".or

review in these natters might shed on Title VII litigation;

(III) Look at cases, both in the circuits and in the Suprerne Court,

which focus on three distinctions critical to a ProPer epglication

'j of the "c1ear1y erroneous" staniard: (A) The suirsidiary fact,/u1ti:,-,ate

fact distinction; (B) The natter of iacl/mat.ter of 1aw distinction;

and- (C) The docunentary case/,,titness credi.biliEt case dis!.inction;

,-J

2

and (fV) Given the case law, analyze it,s impact on Swint v. Pullman.

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE "CLEARLY ERRONEOUS'' STANDARD

IN SUPRE}IE COURT OPINIONS

fn Baumgartner v. United States, 322 A.S. 665 (tg44), the Court

examined the bona fides of Baumgartner's oath at the time he became

an.\merican citizen. fn its discussion of what sort of appellate

review was appropriate, the Court laid out many of the considerations

that have since become mainstays of RuLe 52(a) interPretation:

The phrase "finding of fact" may be a sunmary charactertzat.ion

of c-rnplicated factors of varying significance for ju'lgncnt.

Such a "finding of fact" may be the ultinate jud,;nent on a nass

of details involvir,g not merely an assessnent of the trrrst:;or thi-

ness of i,,itnesses, but other aFilropr iate inf erences that nay be

dra,+n from living testi:r,cny which elude print. The c-onclusi','eness

of a "f inding of f act" CepenCs on Elre nature of the :ater ials

on'*hich the finding is based. ?he finding even of a so-(:a1Ied

"subsidiary fact" i1,ay be a nore or less difficult prccess

varying according to the simpl ici ty or sr.rbtle'"y of the tyPe of'"fact" in conLroversy. Fin,iing so-ca11ed uliimate "facts"

more clearly irrplies the application of stanCards of 1aw. And

so the "finding of fact" even if made by two courts may 90

beyond the determii:ation ihat should not be set aside here.

Though label.1ed "finding of'fact, " it may involve the very

basis on which judgment of fal1ib1e eviCence is to be nade.

Thus, the conclusion that may appropriately be drawn from Ehe

whole mass of evidence is not always '"he escer tainnent of

the kind of "fact" that precludes consideraiion by this Ccurt.

. Particularly is t,his so where a Cecisicn here for review

cannot escape broadly social judgrnents judgnents J-yi.ng clcse

to oginion reEarding the whole naiure of our Covernnent and the

duties and j.in:runities of citizenshrp. 322 U. S. at 570-1.

Several f acets of the Court's opini.on bear noting. First, the

Court distinguishes between findings of subsidiary fact i.e.,

docunentary or empirical fi.ndings -- and findings of ultinate fact,

which the Court analogizes to the application of 1egal stanCards; Ehe

Court feels less obligated to defer to a lower court's findings when

they involve the Latter. Second, the Cour'. states that the source

of a particular factual deternination nay influence ihe deference

with which higher courts view it. Final1y, the Court a1lots itseif

I.

3

a '.rider scope of review in cases involving "broadly social judgments!"

this view of Ehe Supreme Court as the only ProPer ultimate arbiter

of consit,utional questions is borne out in its decisions in the

jury discrimination and confession cases-

The first major case in which the Supreme Court dealt sPecifically

with the requirements of 52(a) was an antitrust action,

United States v. United StaEes Gvpsum Co., 333 U.S. 364 (L947),

where it defined both the scope of the Rule and !h" meaning of the

phrase "c1ear1y erroneous." h'hen findings involve "inferences

drawn f rom Cocuments or undisputed f acts, heretofore Cescr j.bed or

set out, " Rule 52 (a) applies. 333 U. S. at 214. )!ore than si.inple

ei;rpirical Eindings are therefore inclu,lad r"ithin 52 (a) 's SCoPe.

An appellate court can reverSe a Lo'';er L-curt's f indings of fact

"when although there is evidence to suPPort.it, iie revierving court

is left with.the <ief inite and f irm convicticn that a inistake has been

conmitted." Ibid., dt 395. This defi.nition of "clearly erroneous"

is firnly entrenched in the case 1aw.

In United Siates v. YeLlow Ceb Co., 338 U.S. 338, 34L-2, (I94E),

also an antitrust cese, the Court incluied within the sccpe cf S2(a)

" f indings as to the designr rlrotive, and intenc wi ci: which ;en act

f . -r

{srnce they/ degend peculiarly upon the credit ci'ren to witresses

by those who hear them." ThiS statement makes c1ear, as some later

rN views seem to have forgotten, that the major reason why cuestlons

^ay

^W ),, of intent are often left to the deterninati.on of trial cour'.s is the

r.lP J/

'' +W influence which the demeanor of witnesses may have on findings

concerning the hidden feelings of Particular actors-

Three cases Ceci.ied the fo11,--rwing tern further clarifi.ed ehe

Court's conception of the proper bounds of apPellate review. In

United States v. National Association or- ReaI Estate SoarCs, 339 U. S.

---M

485 (1950), the Court elaborated on its statement in Yellow Cab:

"ft is not enough that we might give the facts another construction,

resolve the ambiguities differently, and find a more sinister cast

to actions which the District Court apparently deemed innocent. "

339 U.S. at 495. ?husr dn appellate court could not pit its own

subjective feelings as to how a piece of evidence ought to be

interpreted against a trial court's subjective feeling; the lower

court's interpretation must be objectively mistaken to permit

appellate reversal. In Graver ?ank,and M,fg. Co. v. LinCe Air

Protj.lg-ts Co., 339 U.S. 605 (1950), the Court extended this high Cegree

of de.,-'Grence to.3 case in which fin,liigs of ultinate fact involved

assessing ii;a1y types of evidence and balancing their credibility

against one an,cther. in a patents case, "a f inding of equivalence

is a determination or fabt. 9lhat constitutes equivalency

raust be <ietermined against:h" context of the patent, the prior art,

and the padicular circuinstances of the case. Equivalence, in the

patent 1aw, is not the prisoner of a formula and is not an absolute

to be considered in a vacuum." 339 U.S. at 609. That a finding

of equivalence is not "the prisoner of a formula" will beccme an

inportant consideration in Iight of later cases whose results seemingly

contradict Graver Tank. This inportance of this factor was hinted

at in another patent case decided that term, Greqt Atlantic & Pacific

Tea Co. v. Su.oerrnarket Equipment Co. , 340 U. S. L47 (1950) . In A&P,

the Court saw itself as dealing'*ith the application of particular

standards involving combination patents io undisputed facts, and

therefore as reviewing something which was reore a matter of law than

a finding of fact. Graver Tank, therefore, did not app1y. 340 U.S.

5

at 153-4. The Court seems to be distinguishing, then, between

the subjective judgments involved in inferring attitudes from facts

and the more "objective" type of judgment involved in applying

enunciated 1ega1 standards to the particular facts of a case.

United SEates v. Oregon Medical Society,'343 U.S. 32I (1951),

reiterated the Court's commitment to the Ye1low Cab-N.A.R.E.B.

"clear1y erroneous" standard of review for questions of intent:

There is no case more aPProPriate fof adherence to this

rule than one in which the complaining party creates a

vast record of cumulative evidence aS to 1ong-past trans-

actions r lilotives, and purposes, the ef f ect oE which

depends 1.:rge1y on credibility of witnesses- 343 U.S. at 332-

ilere again, the Court's sentirr-rrent seems to rest on the assunption

that a large part of the value of Rule 52(a) is tied to the trial

couri's aCvantage is assessing witness credibility.

?o the ACvisory Conrmittee on Rule 52, i',oi{€v€r r it SG€i-r€d that

lower courts were often applying the "c1ear1y errcneous" rule 9n1-Y.

in cases in which witness demeanor played a crucial ro1e. In

1955, it reconnended changing Rule 52(a) to read: "Findings of fset

sha1l not be set eside unless clearly errcneous. In the aPPliu-ation

of this principle regard shal1 be given to the special oPportunity

of the trial court to judge of the credibility of those witnesses who

appeared personally before it." 5A Moore's FeCeral Practice r.152.01t71

at 26A9 (1980). The effect of this amendment would have been to

reinforce the applicability of the "cleariy erroneous" standard to

all findings of factr ES the Committee's NoLe makes clear: "The amend-

;a is designed to end the confusion and show definitely that the

"clearly erroneous" test is not modified by the lang4age which for;r:er1y

followed it, but is aFplicable in all ceses. " Ibid. This ainend;nent,

however, was rejected, so Ehe perhaps ambiguous standard of the

original Rule'52 (a) reinains in ef fect.

In United States v. Parke, Davis & Co., 362 U.S. 29 (1950),

another antitrust action, the Supreme Court reversed the loyer court's

determination that the defendant's price maint&ineflce policy hadn't

violated Sl of the Sherman Act. The ioutt's opinion here applied

the analysis developed in the "application of 1ega1 standards" cases

(Baumgartner and AeP):

The District Court prenised its uitimate finding that Parke

Davis did not violate the Sherman Act on an erroneous inter-

pretation of the standard to be applied. . tsecause of the

District Court's error we are reviewing a question of 1aw,

namely whether :he District Court applied the PrcPer sia;':arC

to essent.ially undispu'ued f acts . 362 U. S. at 14.

This tack r.',-=rkcd a departure f ron the approach iaken in srrrlh ,:arl ier

an t i tr us t ,jc,: j s ions as U. S. Gy-p_-I and Yel Lcw Cab, 'rhuaE€ t:le Cou r t

ha,J allt:,',,,e,1 'cria1 courts a gccd deal of g.ltitude in naking ccnciug:.ot'ls

f rom Cocunentary eviCence as to notive a;id intent.

Tte follcwing irear, the Court continued its movement, away from

52 (a) 's restrictions on appellate rev iew in United Slates v

:,li-rs-;pi Generatlng Co. , 364 LI. S. 520 (I961) . ?his case involved

a conf l ict of interest on the par t of a govern;'ent empJ.oyee in the

negotial--ion of a gcvern:jlent contract. In making its decision,

ihe Cour t rel ied on docur"entary f ind ings by the tr ial cour t. licne-

theless, "our reliance upon the finciings of fact Cces not preclr-:Ce

us from naking an independent Iny enphasis] de'-ernination as io the

1ega1 conc-l.usions and inferences which should be dravrn from them- "

364 U-S.'at 526. This case marks the nost e.xpansive stateir,ent of

the Court's power of review. In light of later statenents, its

seems unlikely that the Court would sii1l Ceiine its powers this

broad 1y.

United States v. Singer i'1f9. Co. , 374 U.S. L74 (L962), contains

somewhat contradictory pronounce-the Court,'s atiempt to reconcile its

ments on Ehe proper standard for appellate review of findings of

ultimate fact. fn footnote 9, 374 U.S. at L94, the Court stated

that "fnsofar as that conclusion Ithat the manufacturers' actions

manifested a common purposel derived from the court's aPPlication

of an improper standard to the facts, it may be corrected as a matter

of law. Insofar as the conclusion is based on 'inferences drawn from

. '' .:o.r.ents or undisputed f acts, . Rule 52(a) of the Rules of Civil

Procedure is applicable. "' In light of this disiinction, a good

deal of the Court's prior rulings can be unders'.ood-

On the one side, in Baungariner,.{&P, and Parke Davis, the Court

/ saw the lower courts' acl-iviEies as involving how ':ertain facis o';ght

/

i to be interpreted, given a definite 1.=,;a1 st,.:rlard. In these casas,

t

I

I t.iere was a single correct lens l--hro'jghehich the Perticular facts

\

I ouEht to be vier..'ed; it was relatively sinple for an appellate court

to determine -if it had Cone so. Cn the other side, in Graver Tank,

N.A.R.E.B., and Oregon liedieal Society, the 1c'wer courts' persPectives

on the facts did not have to conforn to a single predeternined 1egal

standard. It was therefore not as easy for an appell.ate court to

...determine errori as a result, it shouLd be more hesitant to do so.

This differencer BS we shal1 see in Section IfI, nay be particu.Larl'

'inportant in a Title VII case: to the extent that a deternination

of discrinination rests on t,he application of certain standards to

the peculiar facts of the caser Efl appellate court becomes freer

to set aside that lower court finding; to the extent that a finding

a discrininat.ion rests more on the judge's subjective inference from

those factsr ED appellate court should be Loathe to disturb it.

in. !lg-!te.d-S!ate,S--v.--Leneral liotor::. 334 U.S. L27, \4L'2' (l-965),

the Supreme Court held that the lower court had erred "in its failure

to apply i.he correct and established stanCard for ascertaining the

I

existence of a combination or conspiracy under 51 of the Sherman

Act.' In a footnote, the Court fleshed out its views:

We note that that ultimate conclusion by the trial

judge. . . is not to be shielded by the "c1ear1y erroneous"

Lest embodied in Rule 52 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. . The question here is not one of "factr'

but consist,s rather of the 1ega1 standard required to be

applied to the undisputed facts of the case. . Moreover,

the-trial court'S customary oPPortunity to evaluate the

demeanor and thus the credibility of the witnesses, which

is the rationale behind Rule 52(a) , plays only a

restricted role here. This was essentially a "paper" case.

384 U.S. at L42, fn. 16.

The Court's belief here seems to be that Rule 52(a) was neant Eo

restrict appellate review only in th,)S€ ir,at'uers in which a Erial

court pcssessed uniqr:s advantages. Ultimately, all thesc' aCvantaEes

can be tr.aced i,ack

whiLe the appellate

i:o oi:e f actor: the trial court sees 1i';e ',ritnesses

crrurt has r:nJ-y a transcript 'in front of it

In cases'*here the trial and appellate courts,3re Eiresent.-d with

iden tical

overruling

made.

evidence, the appellal--e court shculd not be hesitant in

the lower court if it believes that a mistake has been

Zenich Radio Corp. v. Iiazeltine lesearch, f nc. , 395 U. S. 100,

(I969), a patents caser Eetreated soneivhat from the libera] review

standarCs enunciated in This case involved the corre':!ness

the trial judge regarding theof certain inferences drawn bY

da:r'rages Zenith had sustained as a result of a conspiracy in restraint

of trade. After restatiig its commitment to the Gypsum standard

(see p. 3), the Court went on to state that "Trial and aPpellate

courts alike must also observe the practical limits of the burden

of proof. . The Court has repeatedly held that in the absence

of more precise proof, the factfinder may'conclude as a matter of

just and reasonable infeE€i1c€r'r 395 U.S. at L23, that a prcscribed

activity has damaged the plaintiff. fn some ways, this staternenL

seens Lo be t,he f 1ip s ide of the Cour t's bel ief in 3au:rgar tner that

"the conclusiveness of a 'finding of fact' degends on the nature €i

G. M.

i

9

of the materials on which the finding is based," 322 U.S. at 670-L,

and suggests again the Singer distinction -- when a trial court

judge's determination is, by its very nature, discretionary, appellate

courts ought to resPect that discretion, while when a judge's

determination ought to follow some well-defined path, the appellate

court is free to drag him back should he stray.

fn Kelley v. Southern Pacific Co., 4L9 U.S. 318 (L974), an

ernpioyee injury comPensation case, the Court, citing Singer,

reiterated ir-s conviction that appellate review of trial ccurts'

iii,proper applieations of 1ega1 standards xas not at all limited by

52 (a) :

trie need not reach the questicn whether ai-,! of tile Distr ict

Courtrs finaings in this case were clearly erroneous, since

we agree with the Court of A-ppeals that the trial court

applied an erroneous 1ega1 standard in holding that the

piii"tiff rsas within the rea,:h of the irELA. 419 U.S. at 323

?he Suprerne Qourt then went on to discuss the ways in w.hich the

plaintiff could !:ave shown that, tS a tratter "of ccnmon-Iaw principles,

he wes an employee. Ibid. at 323-4. Thus, the Court showed its

r.rill ingness in legaI StaniarCS CaSes to examine caref u11y the

actual Cata in the trial record to dei,ernine if the standards had

been correctly aPPlied.

Davton Board of E{ucation v. Brinknan, 443 U.S. 526 (L979),

was the first case I found in which the Court discussed ihe apPlication

of the "c1ear]y errcneous'r rule in the ccntext of a civil rights

case. In a footnote, the Court stated that "!\'e have no quarrel with

our Brother S.tewar t' s general conclus ion that t,here is great value

in appellate courts showing deference to the factfinding of local

trial judges. The clearly erroneous siarCard serves that Purpose

we11. But under that standard the Court of Appeals performed

its unavoidable duty in this case ana concluded that the District

\)

!

10

Court had erred." 443 U.S. at 534, fn. 8. fn

howeverr the Court characterized the District

having "ignored the 1egal significance"'of the

Dayton's school system had been segregated at

443 U.S. at 535-6. bnder the Court's previous

mistaken application of a lega1 standard need

erroneous to be overruled.

the text itself,

Court's error as

empirical fact that

the time of Brown I.

analysis, such a

not be clearly

The i'ncst recent case having a potential i,lpact on the scoPe of

Rule 52(a) is Burdine v. Texg3. lele5!3rent of Cotnmunity Af fairs,

,r, ,rrtrr. ,here, the Court declined to decide whether49 U.S.L.W. 41

the Fiith glssr:it had erred in declining to abide by the "cIearly

errcnecu.s" stanCard in its review of the District Court's finding

of no discrinination because "the Court of LPpeals epplied the v;rcng

Legal stanrlard to the evidence. Iny enphasis]" 49 U.S.L.W. at 42I7,

fn. L2. This suggestion that, the l'lcDonne11 Douglas three-step

process for showing a violatj.on of S703 [i'-rsDonIgll -Douqlas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. '792t 802-4 (1973)1, is a lega1 standard which

nust be folicwed in each Tit,1e VII case could trrr€an i.hat intenticnal

discrinrination ought to be viewed in the PersPective sei out in the

Ba':mgartner-?arke Davis-Dayton line of cases, where the more restric-

iive stendard of review rnandated by 52(a) is inapplicable.

Overal1, then, the development of RuIe 52(a) in Supreme Court

cases suggests that the Court takes a restrictive view of aPpellate

review prinari.ly in cases where it believes that the lower courts,

through their actual contact with witnesses hold a significant aCvantage

in balancing different forms of evidence in making findings of ultimate

fact. fn areas in which controversies over the actual facts are

absent, the Court views appellate courts as equally capable of applying

the correct lega1 standards and therefore as not being as strictly

bound by prior lower court deterninations.

a r,

,{..- :

rr..

ffi"I83,Irgr*$y* couRr REvrEv ru ,ruRy DrscRr!,txt{AtroN

AIID

.This' vierr .is particularly strong in cases involving what Ehe

_ r-us_ J.IvoJ.v:.ng What Elfe

elose to opiniorl resarrrin- .r-^ -., - '. judgrments lying

;::,: :J',#:.,:"':T. ll" *n"'. ;;,; ;; ;:,ff. .:j',j:;;=,:.:;;.'T:T,."iidas f,urther disti 1 , ^r .: _was f,urther distilled in

:

.;1

''ll

::j.J

A. MI8Y SELECTION CESES

For over go years' it n-":-be3n establis!:d.

!rr.t a criminal

convinctic

craus e-#"to3tt3"ff3::t:'nno t "';;-dictment o

-reasonor'f ,:.i;;;;iliHtrHL'"'f

=#i"5:t3*tfu

.1'=i"""ilil;i.;"', ?3r"rlr"l". jr"l ?Etl3i;l'*i..i;;i. "iii*l* I

-"7ury cases involve violation of a consEitutionar provision, theurteenth Amendment, and not of a statute, such as Titre vrr. This

,o ro.J ;; ;."".,,* :j.J::::"are duty borurd to make an 5'ndependent extsrnination of the evidence inthe record-" 41g u.s. 506, 517 fn. 6 (1974).' this reslrcnsi'bir:'ly to scrutinj-ze carefu]ly any state action whichmight deprive citizens of their federal constitutional rights wasreiterated in .rackson v. virqinia , 443 [I.S. 3O7 (1929), acaseconcerniag tbe sufficiency of evidence

"

\

lard - -r-__-*:.*t

er evrdence aRd the "beyond a reasonabre

:::"":jt':l';".:,::::T:

;re

that ,.A rederal couft has a dury

; called upon to apply aconstitutionar standard to a convicti.on obEai.ned in a state coult.,.443 u's' at 31g- this approach is compatibre, of course, witb t.beone laid out i,' the "1ega1 standards,, cases examined in secti.on r.frro areas in which the phil0sophy of supreme court reviero is particularlywell-deveroped are Possible racial discrimination i.n grand jury serectionrnd Ehe deteruination of vo*:'tariness in confessions.

14

lAJs the Court recogniaed in Arlington Eeights, " [s]ometimes

' i clear ;nttera, unexplainable on grounds ottrer than race,

energer Eroru the effect of the etate action even when the

goveining legielation aPPears neutral on its face. . . Id.,

aE 266."

"raehano+-on: ;- Dauis itself recognized Lhj.s stanCard of sc:rrtiay as

alrpropriate in jurlz eases, the Castaneda court went on to Point out,

430 Ir.S. at 4932

It ig also clear [the Washincton v. Davis Cor:rt wroteJ from

ttre cases

-dealing -withffiion i.n the selectioa

of juries that, thd systematic exclusion of Negroes is ;!!3,!f- [my emphasisJ such an 'r:negual application of, the law . Els

1 gp-show intentional discriminatiotl." 426 g.s: at 24r.-

Ainally, in Rose v. ttitchell , 443 Ir.S. 549 (L979), the Court reaffirmed

its obligation to.exaurine-;rcssible defects in a grand jury's composition,

even in light of Stope v. Powell , 428 Ir.S. 465 (1976), whicb had held--

that a federal habeas corpus claim could not be invoked by staEe

prisoners who had been afforded the op5:ortr:nity for full and faj.r

consider:ation in state court of their claims relatiag to the adruission

of iIlegalIy seized evidence at their trials. Taking into account both

tbis decisj.on and JusticeJackson's dissent in Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S.

2A2 (1950), another jury discri:nination case in whj.ch a conviction had

l:een overtrrrned because of biased grand jury selection procedtutres,

.fustice Stesrart argrred i,hat conviction by a properly coustitsuted petit

jury convinced of the defendant's guiJ.t "beyond a reasonable doubE"

cured any taint in the grand jury selection procedure and therefore,

that neither on direct appeal nor on collateral review, should 3 con-

viction be set aside. The Court rejected this argument r:nequivocally:

This Court, of course, consistently has rejected this.argr:ment.

IE, has done so iarplicitly. . . . [alna it has done so expressly.

. . . We decline not to depart from this longstanding consistent

practice, and we adhere to the Courtts previous decisions.

443 U.S. at 554.

-:- The Cor:rt, then, has continued its cornmiEnent to proviCing ttre

fullest possible review in constitutional rights deprivations cases

involving discrjrninatory practies even after it significantly lirnited

:.5

access in other cri-ninal consrtitutionAl rights matters. Thj-s decision

,

seemsr to spring f,rom two f,aetors which may also affect its views iJ,

. regard to Title rJEI litigation. First, the preei'bnce or absence of

'di.ecrj:ai-natioa is an issue of ultimate fact, depenaent on judgrnent

and the application of analytical standards tso tlre raw uaterial peculiar

to the casei appellate courtE are as gualified as lower courts to

make ana1ltic decisions which approach the status of qr:estions of lalr.

Second, discri:ninatorT jtrry selection Procedures, unlike, SsYr the

admission of illegalIy seized evidence at a trial, have a social

i:npact far in excess of theii i:nlnct on the individual. The SupreBe

Court has recognized this since its serrinal decisioa in Strauder v-

West'Virqinia, 1OO U.S. 303 (1881). There, it ;rci-nted out that j*n '

addition to denying equal proteetion to blacks tried before juries

from which their Peers had been excluded:

The very fact that colored peopte ale singled.out and expressly.

denied iy " statute all rigLt to participatg in the admj-nistration

of 'the.Law, as jurors, because of their color, !E9"gh they are

citizen= "nd may-be in other respects fu1Ly qualified, is practically

a brand uPoE th-en, aff,ixed by the law; an assertion of their

inferiori-ty, and a sti-nulant t.o t.Lat race prejudice which is en

impedinent- to securing to individr:als of t.be race that equal

iGtice which tbe law-ains to secr:re to alJ. others.'100 U.S. at 3--

The same analysis holds 5.n fitle VII cases. If minorities are barred

from certaia 5rcsitions, either outright or through the'workings of

intentionalJ.y discriminatory testing or Promotional systc?ls, their

ensui:1g economically disadvantaged conditlon will place a badge of

inferioiity ou ttrem and barmful stereotllpes about their lack of

ability wiJ.l be perpetuated.

B. TEE QUESEION OF VOLUNTEX NESS

The Fifttr Amendment provides that no person "sha1l be compelled in

any criminal case to be a witness against hjmself." Through the

Fourteenth Amendment, ttris prohibition has been held applicable to

state prosecuLions as well. l{alloy v. Eloqan,.378 U.S. 1, 6 (1964).

-

.15

Slnce ttris Ls a federal right, the Court went on f salr it should be

judggd by the gtandards developed ia federal cases. I!&, at 10.

Evea prior to tbe wholesale inc-orporation cirf the eeJ;E-incrj.rnlnaLioa

clause, the'Suprerue Court had he1d, in Brown v. liisEissippir 2gT U.S.

278 (1936), tlrat the use of coerced eonfessions fr:ndarnentally

violated due process and was thus prohibit,ed by the Fourteentb Anendment.

- ., aL 297. The questioo which . the Court addressed in these cases

which is of the most interest tso us is: what should be ttre role of the

Supreme Court i.rr detenn-ining

Parrne v. Arkansas, 356

ttre voh:ntariness of a confession?

Ir.S. 560 (1958), involved tlre murder

r:neducated black man who was held incorununicado

confi:ering tlrat trse of a confession obtained

coercion violated ttre Fourteenth Anendruent,

conviction of a I9-year-old

un€:t his confessiotl. After

by either physical or nental

tbe Cor:rt continued:

Enforcement of the criminal laws of the States rests principally

wittr ttre state corxrts, and general.ly their f,i.ndings of fact,

fairly made upon sr:bstain$4l and conflicting _testimony as to

the ci.rcr:mstances producing the eontested confession . . . are

not this Cotrrt's c6ncern; yet when the clai:n is that the prisoneL's

conf,ession is the product of coercion we are borrnd to make our

ordn exanination of the record to dete:-aine whettrer the claiu i.s

meritoriogs. . . . That question can be answdred only by reviewing

tlre ericr:mstances under which the confession was made. 356 U.S.

at 551-2.

The scope of rerriew the Supreme Court allows itself here is even Bore

exte:rsive than that which it carved out in jury cases, since here it

will make an independent judgruent even in cases involving conflicting

evidence and live testiuony -- factors which the Cor:rt usually had

foqrrd to give the trial cor:rt a decided advantage i:a detaarining the

issue involved. Cf Gravel Tank, EI1g3 at 4, where tbe existence of

confU.cting evidence was taken as a justification for appellate

deference. Again, it seems that the Cor:rt's feeling that it should

l:e the ultjmate arbiter of constitutional rights overrides its sense

of the deference that ought to be Paid to tbe advantages held by

b

triaL cor:rts in assessing credibllity.

I

.17

.. I

Blacl<burn v. Alabama, 361 U.S. 199 (1960) made elear the resolution,

,n. the Suprene Court had nade betueen Ehis c0urpeting clains. After

r)

.atatingthatithad'accord[edJaI1oft}redeferbncetothetria1

' Judge. s decision which is compatible with our duty to ,dete:::inine ' :-i_ _ __ a:..

constitutional questions, " 351 U.S. at 205, the Court reminded lts

readers tlrat ',!re cannot escape Ehe restrrcnsibility of scntinizi'ng the

record ourselves." @4!., fn. 5.

Brookhart v. Janis, 384 Ir.S. 1, 4, tb,-4 (1966), expressed the

view that voluntariness was a matter or 1aw or ultirnate fact suitable

for unhampered appellate review: "When Constitutional rights tura oa

the resolution of, a factual dLspute vre are duty bound to make aa

indep€ndent srami-nation of the evidbnce in ttre record. t'

'

Davis v. North Carolina, 384 Ir.S. 737 (1966), tras decided after the

Cor:rtrs landmark decision in !.{iranda v. Arizona, 384 Ir.S. 436 (1965)-

lj-mitett by t-be decision in lfiranda, but rather that !,tir-anda provided

a rrsefuJ. tool i:e assessiag vo1r.:nta=i-ness. 384 U.S. at 740. The

Court once again for:nd that its duty required it " to exarn-ine the entire

record and to make an ind,ependent dete::urination of the $!!gfl!3i, issue'

of volrrntariness [my emphasis] . " JE&, Bt 74L-2. Ttuls view was confi:med

iu1ater.decision,e.g.,,397U.s.564,555(I97o};

Beclcrpith v. united States, 421 U.S. 34L, 348 (1976).

ttuo relatively recent cases have amplified the Court's ;rcsition.

In Drope v. I.tissouri, 42O U.S. L62, the State had argued that the

Supreme Court owed a good deal of defere.nce to the fi.ndings of the Missor:ri

Supreme Court. After replying tbat it "share[d] resSrcndent's concern

for this necessara, ba1ancer" 420 II.S. at 174, the Court went on to

i _, say that ttris case involved making inferences from established facts

and that it was "incr:mbent on us to anallze the facts in order that the

I

'rg

approPriate righE,

59O (1935)." 42O

lts view of,

stronglys .

may be assured. Nrrrri c v A 1 ahama . 294 u.s. 587 , ,

U.S. at 175. In a footnote, the Corrrt stressed

the nature of a flndlng of, volrrntarii:ess eveo more

But .issuee of, fact" is a coaE of, many colors.. IE' does nots

cover a conclusion drawn from trlcontroverted happenings, when

that, "orr"i*i-n

incorSro;E; Etandards of conduct or criteria

for JudgmenE which "rL-io

themselves decisive of constitutional

right,s. Such st,andards and criteria, measul"d 1:"T:: !li. -i.ioir"r"ot=--a""wn frcm eonstitutional. provisi?ns, and tlreir

proper .;;ii.;Lions, *. issues for thi; Cor:rt's adjudication'

. . . e=ia"ially in cases arising under Ebe Due Process Clause

it-ir i-f;rg";E m disinguish-belween issues of faet that are

here rorlli&"a ""a-i="o!=

which, though cast in the fom of

detaminalions of fact, are Ehe very iisues !-" review which this

Court sits. watts v.-inaianq. 338 t.S. 49, 51, (1949) (opinion

of, Frankfurter, ,lJ IL|.L, fn' 10 '

The most recent case involving voh:ntariness was decided this

te::B, Edwards v- Arizona, 49 I,.S.L.W. 4496 (1981) ' In the majority

opinion, the Court overturned Edwardst conviction since, although he had

requested a lawyer, detectives interrogaEed hi-m again before the

lawyer had arrived. The Cor:rtts rationale -- that ". . . [T]he

Arizona Supreme Court applied aB e:ironeous standard for deterrtilling

waiv-er when the accused has specifiealJ.y invoked his right Eo cor:ns€I, "

49.Ir.S.L.W. aE 4497 - falls squarely within their tradilional

apBroach- ,fustice poweJ.J.ts concrurrence, in which ,fustice Rehnqr:ist

joi.ned, borpever, argn:ed thaE the "relevant inquiry -- whether the suspect'

desires to talk to 1rcIice without counsel -- is a question of fact

[uy emphasis] to be dete:mi:zed in light of a1I the circumstances-"

Ibid. at 45o0. while at first this night see!! a dangeror:s departure

fra earlier views on tbe nature of tbe f,indings involved in voluntariness

cases, tshe tone of the concrurrence as a whole is somewhat less

radical. Justice Powell is objecting to making the

of who "initiated,, a conversation b,etr,veen lrclice and

factual dete:mination

dislrcsitive of the enlire constiEutional question of

Ee still seeras loyal to the court's general approach

the suspect

voh:ntariness.

of looki-ng

(^

I9

at',various f,acts that may be relevant t'o dete:ani"ning whet'her there

has been a valid waiver, " &jtL at 4500, independently, and applying

a constitutional standard in makiag Ehe final deter':o.ination- such

a perspeetive does not necessarily suggest Ehat ure iuprene Court

itself play a less aetive role in revierling: cases of this sort'

With this general overvies of the Supreme Court's Srcsition as

backgror:nd, I will not discuss Possible applications of these

formulations of, the role of, appellate revien to discri:nination cases'

Because the supreEe coult itself fras not slrcken very clearly as

to Ehe role of, appellate review in th,ese matters, most of rny

examination will be based on cases decided by the various courts of

Appeals.

III. APPLICATION OF Tffi "CLEARLY ERRONEOUS.. RULE: THREE DISTINCTIONS

AISD TEEIR RELEITVANCE TO DISCRII'IINATION CASES

When asked during his testimony at the Chicago 7 trial to stick

to ttre facts, Norman Mailer retorted',Facts are nothing without their

nuances, si!.' Three nuances which the courts have divined in the

phrase "findings of fact" have substantially loosened the strictures

placed on appellate reviesr by nule 52 (a) 's "clearly erroneous" requirement'

A. SUBSIDIARY FACTS AND ULTIMATE FACTS

Ever since Baumqartner, .!g!j!g, courts have recognized a difference

between issues of subsidiary fact and issues of ultirnate fact' A

finding of subsidiary fact involves specific, quasi-empirical, details'

AIso, in light of the decisions in Gvpsum, YeIIow cab' @.'

and Zenith, it seems that "freestyle" inferences from basic facts

are subsidiary; that is, cbnclusions not dependent on a particular

and well-defined legal standard. deductions which could be made by

a layman, are findi,ngs of fact within the meaning of 52 (a) - In the

language of the Baunsartner oPinion, a finding of ultimate faet,

20

more clearly irnplies the application of standards of law'

Though f"Ueifea',,f,inding oi-fact," it may involve the very basis

on whieh'J;9*;"t-oi tait:.Ute evidence ii to be made. Thus the

conclusioi tiat may appropriately be drawn 'from the whole 3aass

of evidei""-i" tot-aliiys-the asiertainment'of the kind of

;i""t;-ril;a pr""roa"" "i,".iaeration

by this .court.' 322 U.S. at 671

.

Over the years, appellate coutts have struggLed with the ap5llieation

of what often seens to be a W gUJ.deline as to how to distinguish

between lower courtst inferencet, which are subject to Rule 52(a)"

protection, and their findings of ultimate facl-, which are not'

stevenot n __llosle:g, 2]:o t.2a 515 (gth Cir., 1954), involved a District

coutt order that certain employees be rehired.by the court-aPpointed

Trustee in a Chapter X reorganization proceeding' In explaining its

decision to overrule the.District Court, the Court of Appeals ex-

plained thats

When a finding is essentially one dealing with-the effect of

certain transactions or evenls, rather than a finding whigh resolves

ai"p"i"a facts, Brr appellate court is not bound by the rule

that findings "n"ff irot U" set aside unless clearly erroneous

but is fi""'to-ai"r, its ohrn conclusions. 210 F.2d at 619

At first glance, the Ninth circuit's position seems at odds with the

stance taken by the Su-oreme Court in dvosum' Yeilow Cab' and Grave=

Tank. Eere however, the court of Appeals saw this District court's

fi.ndings of the effect of rehiri-ng the fired employees as being

con'ected to its assumption that the discharges were "in direct vioration

of the subsisting contractual rights of the appellees.'' Ibid' What

these contractual rights are, the boundaries of a court's Power to

order specific performance, and the ProPer supervisory role of a

District Coutt in Chapter X proceedirgs, are all legal questions'

Thus, the inferences drawn by the lower eourt did not depend solely

on the baspfacts; they also involved the application of legal standards

and tsherefore were ngt Protected by the "clearly erroneous" test'

l,luch the same position was taken by the Third circuit in sears,

Eoebuck and co. v. Johnson, 2]'g r.2d 590 (1954) . Johnson had set up

the ,,AII-State School of Oriving.." Sears, which had spent millions of

(1

(

2l

Sdollars promoting its "Allstate" brands of automobile accessories and

automobile insurance, "o.L claimi'ng that it was being damaged by the

,,Confusir.rg similarity" of the two names. Citing'a previous. Case'

O4ips, Inc. u. Johnson and Johnson, zOG F.2d 144 (3d Cir', 1953) ' cert''

denied,346u.s.a67(1953),thecourtexplainedthattheevidence

used to prove "confusin$ similarity" was protected by 52 (a) ' but

that the conclusion itself was not:

, Rule 52(a) is not.apPlicable where, d5 here, the dispute is

not as to'ttre basic-?acts, but as to what inf,erence (i'e'

ultimate-facil should reasonably be derived from the basic

facts. fhis court, bY examining tfre basic facts found by

the district court, can determine, 8s aduantageously.-""-!I"

district-"""rt-".r, whether or not an inference of likelihood

of confusion is warranted. 219 F'2d at 591'

The court,s eguatS-on of, inference and ultimate fact here is somewhat

rnisgruided in light of the SuPreme Court' s atterupts to dif ferentiate

the two. This case can be reconciled with the mainstream, hor"evetr,

since the third circuit seems to view likelihood of eonfusion as

involving not merely inferences drawn from the case at hand' but also

the application of an evolving legal standard developed through the

prior case law. The Court gives credence to this interpretation

when it cites the Restatement, Second, of Torts, 3s setting forth

"the generally accepted factors to be considered in determining

whether a particular designation is confusingly similar to another's

trade name.,. 219 F.2d at 592. The weight given the four factors

Iisted in the Bestatement removes the findings in this case from the

class Of freestyle inferences t'O which the "clearly erroneous"

standard applies, and places them in the category of "application

of leagl standardsr " which are accorded 'a much freer review. Thus,

the,,inferences,,to which the Third Circuit refers ought really to

be prefaced with "legal."

Galena Oaks Corp. v. Sccfield, 2!8 F.2a 2]-7 (sth Cir" 1954) is

the semj.nal case underlying the Fifth circuj.t's distinction between

*r:hsridiarv and ultimate facts- In Gaiena Oaka, the Ccurt addressed

",

.l)

" l,J/V

\.-, , '

. -I"

, IT\.' ut;

, r' .{,r

,}

c,4.'Y'

22

the qdestion of the purPose f,or which the plaintiff had held

property. In an earlier case, the rif,th Circuit had declared

ultimate facts fell under the "clearly erroneous'" standard'

Dunlap, 210 F,2d, 465, 468 (1954). II1 Galena oaks' howeeer''

certain

that

Lobello v.

as the so-ealled "ultimate fact" is simple lhe result resched

by proceir-"t lega1 reasoning from, or the interpretation of

tire-tegai significance of, the evidentiary facts, it is

,;"olj"it to ieview free of the restraining impact of the

so-.called ' clearly erroneous' trule - " IJehmaEul v: lg!te-!on'

206 F:2d, 5g2, 594'(3d Cir-, 1953) ' 2:.8 s'2d at 2L9'

Recent cases have conti-nued to view less deferentiaL treatment

of lorer courts' findings of ultimate fact as appropriate. In

University Ei1ls, Inc. v. Pattoq, 427 f.2d 1094, 1099 (1970) ' the

Sixth Cirarit exPlained that

Although findings of fact adopted by a-District Court are

Linaini or-"tr aipellate eourt unlesi clearly erroneous, Fed.R.

Civ.p. 52 (a) , iirlerpretation of written contracts, conclusions

of law, *i*li questions of fact and law, and findings as to

an ultimat"-i"Et, adopted by the court, are not subject to lho

rule and are within the competence of an appellate coul!' -^Cordovan

associates, lnc. v. Pavto+ Ruhher. co. , 299 F.2d_858, 859-50

itates, 415 F.2d (6th Cir-, 1970)

The group of determinations ttre silth circuit exempts from the "clearly

erroneous" fule ate all ateas in which the lower courts Possess no

advantage in interpretation. This theme runs throughout both the

Supreme Court and the Courts of Appeals' discussions of tEe applicability

of RuIe 52(a): the rule was designed to take advantage of the-':

trial court's oplrcrtunity to observe live testimony; when that ability

has no appl]cability to an individual case, the rule loses its force

and appellate courts should not hesitate to review.

Karavos Compania Naviera S.A. v. Atlantica E<port Corp', 588 F'2d

1, 7-g (2d Cir., 1978), contains the most extensive recent discr:ssion

of thj.s issue. Appellee's contention that the district court's finding

of agency was a finding of fact which fell within the scope of 52 (a)

',flies i-n the face of this court's long-held position reiterated as

recently as in Kennecott Cooper Corp. v'. Curtiss-Wright Corp., 584

...

23

F.2d 1195, I2OO n. 3. that'[t]he application of a Iegal standard

,

to the facts is not a "finding of fact" within the rule.'"' The Court

went on to point, out that "even the advocat,es of'.a broad reading of the

term'finding of factrr" concede that errors in the interpretation of a

1egal standard to be applied render the whole determination subject to

reversal without the necessity of finding clear error. After discussing

the interpretations of the various circuits, Karavos concludes:

It simple appeals to us to be more consistent with the language

of the Ru1e, with clarity of analysis, and with the apProPriate

roles of the district courts and the courts of appeal to sa}rr

as we have been doing for thirty-five years, that the aPPlication

of a 1ega1 standard, whether it is a "question of law" or

not, is not a question of fact within F.R.Civ.P. 52(a).

several circuits have discussed the subsidiary fact'lultimate fact

distinction. specif icil1y .as it applies to findings of discrimination.

The l'ifth Circuit has been expecially concerned with this guestion.

United Sates v. Jacksonville Terminql Co., 451 t.2d 4L8, 423'424 (Sth

Cir., 1971)r cert. denied, 406 U.S. 906 (L972\, was its first major

statement on this issue. In this case, involving alleged violations of

litle VIf on the parts of both. the employer and the unions, the Government

claimed that the district court judge had "erred in his findings ofrultimat,e

fact (such as conclusory statements that particular acts or series of

acts, did not establish the existenmce of discrimination or discriminatory

intent as defined in Title VII) r ds well as his 1ega1 conclusions dervied

from the factual milieu." 451 f.2d at 423. lhe Court announced that

"Ii]nsofar as the Government's attack is predicated on these grounds, the

'cI€arly erroneous' rule is not a bulwark hindering appellaEe review."

Ibid., at 423-424. The Court's citation of Singer, .9-g,, shows at least

that it was sensitive to the fine distinction between "inferential"

secondary findings of fact and "Iegal' ones.

The Circuit continued to pursue this line of analysis in such

cases as Hester v. Southern Railroad, 497 E.2d 1374, 1381 (5th Cir.r L974),

(^'\

24

where it held that a"conclusory finding of discriminat,ion is among the

class of ultimate facts dealt with a conclusions.of 1aw and subject to

review outside the constrictions of Rule 52(a)." In .Causev v. Ford

Motor Co., 516 F.2d 416 (5t,h Cir., 1975), it elaborated on this vien;

citing Baumgartnerts definition of an ultimate fact as one equivalent

to judgment itself, the Court declared that

Although discrimination ve] noq is essentially a question

of faci, it is, at the saiECffi?, the ultimate issue for

resolution in this case, being exPressly Proscribed by

iZ V.S.C.S20OO (e)-2(a) . As such,- a f inding of -discriminationor nondisirimination is afinding of ultimate fact. .

In reviewing the district courtrs findings, therefoE€r we

will proce"S to make an independent deteimination of appellantrs

altegitions of discrimination, though bound by- findings of

subsidiary fact which are themselves not clearly erroneous.

515 r.2d at 421.

The Fifth Circuit's analysis here also echoes Parke Davis, G.!1., and

Ke11ey, supra, where the Supreme Court seened to be saying that a trial

.) court could not insulate !t,s actual resolution of the issue being

tried before it frorn appellate review simply by terrning its determination

a finding of fact.. The Fifth Circuit has repeatedly affirmed its

'

commitment to t,his viewpoint. See, e.g., East v. Romine, Inc', 518 F'

2A 332, 33g-g (Sth cir, I975) ; Wade v. l'lississippi cooperaEive Extension

service, 52g F.2d 5og, 515 (5th cir., L976)i aames v. Stockham valves and

Fittings Co., 559 1l.2d 3iO, 352 (5th Cir., L977), cert. denied, 434 U.S.

1034 11978); Parsons v. Kaiser Aluminum Co., 515 F.2d 1374, !382-3

(tth Cir.r 1978), cert. denied,44L U.S. 968 (1979); Crawford v'

Western Electric Co., Inc., 6!4 F.2d 1300, 1311 (5th Cir-r 1980), and,

of course, Swint v. Pullmaq:Elgndg!9.

l{hiIe they have not dealt with this question in quite as much

depth

same

1970 )

as the Fif th Circuit,, three other circuit,s have used roughly the

analysis. In Strglta v. w!e_e!_gn_S-l-ass__Co., 42L E.2d 259 (3rd Cir.,

,4@,398U.S.905(1970),.theCourtexamineda-c1aimof

i)

25

sex discrimintt,ion arising under the Equal Pay Act. The diitrict court had

/.- t.\ .' found that the etnployer had raet'the burden of proving that the disparity

in

1av

nas.b-ased on factors other

-than

sex and fo.unu.In$:fore that

rces i,, 'o'f E

: '

the differences in pay were due to reaL differences in work performed.

such a finding was not protected by 52(a), the court held: "we are not

. . . bound by evidence which has not reached the status of finding

of factr 1oE by conclusions which are but legal inferences from facts.

lciting Laumqartnerl Lehmann v. Acheso.n, and Sinqer] 421 F2d at 267.

The seventh circuit, specifically depending on th: rifth

Cir.cuit's analysis in East v. Romine,.ggpg,, and its own Previous

holding in Stewart v. General Motors '(see Section IIIB, !!g),

held in Unired States v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 4I5, 425 (7th Cir., L977),

cert. denied, 434 U.S. 835 (L977), that "distinction must be drawn between

subsidiary facts to which the 'clear11z erroneous' standard applies' and

the ultimate fact of discrimination'necessary.to trigger a statutory or

constitutional violation, which is the decisive issue to be determined

in this litigation.' rn Flowers v. crouch-walker corp., 552 t.2d L271,

L2g4 (7th Cir., Lg77), a case involving alleged racial discrimi.naEion

in the dismissal of'a bricklayer, the Seventh Circuit reiterated its

adherence to this view:

[W]hen the factual determination is primarily a matter of drawing

inferences from undisputed facts or determining their lega1

implicatj.ons, appellale review is much broader than where

diiputed evidenll and questions of credibility are involved-

The Eighth Circuit expressed much the same view in Christopher

v. State of lowa, 559 F.2d 1135 (8th Cir.r L917). This was a sex

discrinination case where the Court of Appeals affirrned the trial court's

decision for the defendant. Nevertheless, in discussing the standard

of review which it planned to apply to the district court's findings,

the Court said

lhe acceptance of the trial court's findings of fact does not

r)

r.-

26

requirethatrreaPPlytheclearlyerroyous.standardin

teiting "fr"tfr.r tiri -conclusions drarn from the found facts are

in accordance with established 1an. The scope.of the elearly

erron."""-=t"ndard does not Preclude such'.inquiry' 559 F'2d

at 1138

Only the First Circuit has i position subs'tantially at odds with'

this general consensus. 1n Sweeney v. Board of Trustees of Keene State

Q!}99g,, 504 F.2d 105 (Ist Cir.r 1979) and Manninq v' Frustees of Tufts

Colleqe, 613 B.2d l2OO (Ist Cir.r 1980), the Circuit stated its position'

In Sweeney, the court responded to the plaintiff's suggestion that

the clearly erroneous standard didn't apPly to Tit'le vII discrimination

cases, because the "factual" finding was equivalent to resolution of the

1ega1 issue of discrinination:

we are not inclined to that approach. This circuit has applied

to the clearly erroneous stanEird to conclusions involving.

mixed d;;ai;;s of 1aw and fact except when there is some indication

that ttie court misconceived the 1ega1 standards. 504 F.2d at 109,

rn. z.

I,lanning, 613 F.2d at 1203r. noted this theory with approval.

Upon closei examination, however, neiLher of these cases is

apposite to general Title VII litigation. Both cases involved temure

decisions on individual faculty members. This is an extremely

idiosyncratic Process, one in which extremely personal judgments are

made by colleagues; it in no way resembles decisions about seniority

systems, rrhlch operate 1ve11-nigh automatically, or entry-leve1 jobs

in which personali!y triits have little significance' Indeed' the

Court noted in both cases that live testimony had had a major impact

on the diStrict court's decision:

. the opportunity for firsthand observation may be

"si."iifiy

iioportant in [a casel such as this, where the

issue is whether "personility" reasons were sexually biased'

[Sweenev] 604 F.2d at 109

. the district court's jucgment about credibi.lity,

formed during o-necessarily short hearing, must.have a large

;;;;i;g on rri= conclusion lbout the underlying issue of

whether the complainant has been a victim of sex discrimination'

27

[llanninq] 613 F.2d at L204

applicability of 52(a) in more detail. Suffice it to say here that

question 'addie-ssed in thethe questlon in these cases, unlike the question lddr

cases I cited in the Third, Fifth, seventh, and Eight circuits, does

not involve undisputed facts and the aPPlication o€ lega1 standardsr

but rather concerns the actual iletermination of basic facts (whether

the perionality issue was dependent on the plantiff's sex.) As footnote

2 in sweenev, .:gE!3,, admits, misconceptions of lega1 standards are

excepted from the clearly erroneous rule's scoPe' This exception seems

much more akin to the rule exPressed in the other circuits, than the

rule the First Ciicuit'propounds.

Especially given the tone of the Supreme Court's recent opinions

in Dayton Board of Educa€ion and @ suBra (see PP. 9-10), I think

that the prevailing mood on Rule 52(a) is that the district court's

applications of particular 1ega] standards is not particularly

privileged. In fact, as \re shal] see in the next section, the

intermingling of issues of law and

rather than attemPting the futile

to treating the whole melange as a

fact is so cornplete that' many courts,

task of disentangling them, have taken

matter of Iaw.

',f ,r,

"} IN v( J

A^vt

Jd

28

B. MATTERS OF 8ACT,/MATTEB.S OF I'AW

,'Rule52(a)describestheverynarro'/,reviewthatmaybe

giventofindingsoffact.Itissilentaboutlega!conclusions.

This sirence has been correctly interpreted as meaning that the

,clearly ertroneous. restriction in not applicable and that the

trial coutrt,s nrlings on questj.ons of law are reviewable without

anysuchlimitatj.on..,gWrightandl,tiller,FederalProcedr:reand

Practice 52588 (1971, P' 750) '

IDgj:@,,.gE,theSupremeCourtdecidedthata"conclusion

derived from the courtrs application of an iroproPer stand'ard to the

facts...maybecorrectedaS.amatteroflar.l."3T4U.S.at

Lg4, fn- g. Mississippi Generatinq co., -SsEl, also presented

this view . 364 u.s. at, 526 (see p. 6, above.) since Baunsartr-Ier

hadalreadydescribedt,hisapplicatio.nofastandardoflawto

theparticularfactsofacaseasafindj.ngofultimaE,efact,

Lower appellate courts often have seerned confused as to which

category--questionoflaworquestionoffact.-ultj.matefacts

oughttobeincIudedin.TheSecondcircuit,sanswerin@.,

supra -- that whatever a finding of ultimate fact turns out to be'

Rule 52(a) doesn't apply to it -- is probably the most prag:matic

approach.

Altshoughnoneoftheothercircuitshascomeout'with quite

(- :

so pragxnatic an aPProach, several of them have treated t'he

issue of statutorily-prohibited discrirnination in much this fashion'

The existence of discrimination in these cases straddles the

Iine lretween gtrestion of fact and question of law with almost

incredible agility. on the one hand, the existence of discrimination

is a factual, statistic issue which the plaintiff must dernonstrate

in order to make out a pri:na facie case. on the other, ie is

. O'u,. /'(*'/ lhe ultirnate issue to be estabU.shed by Ehe liti'gat'ion, as

A. L7/ J ' u.S. v. chicaqo, EllPE, amongi others, has Srcinted 6ut' Given

a"" t*teme Court's analysis in the sLL case' -s!E' that the

. "ultirnate conclusion by the trial judge : is ' not' to be

shielded by the 'elearly erroneous' test embodied in nule 52(a),"

3g4 U.S. at, L42, fn 15, most Courts of Appeals have reviewed district

courts, findi.rags in discrimination cases with less compr-rnction

about interference in the trial courts' bailiwick than they normally

show, since to exercise no:mal deference here would be, in

essence, to rubber stamp any lower court decision.

The Fif,th Circuit has frequently commented on the question

of the proper pigeonhole for discrimination cases. fn II#,

EgpEg, it pJ-aced " [t]he conclusory finding of discriminati-on

among the class of ulti.urate facts dealt with as conclusions of

Law and srrbject to reviesr outside the constrictions of RuIe 52 (a)."

4g7 ?.2d at 138I. In 33IEg, EgpB, it elaborated on this view:

I{e are qiso careful in discrimination suits, where ttre

elernents'of fact and law become particularly intermeshed, of

the distinction between findings of sr:bsidiary fact and

findings of ultimate fact. A iinaing of nondiscriraj-nation is

a finding of ultimate fact that can be reviewed free of the

elearly erroneous rule. 575 F.2d at 1382-3'

grawford, E;g, 614 l' .2d at 1311 also reflects this perspective:

,'The ulLirnate legal issue i-n a Tit1e VII or section I98I case

is whether discrj:ainaUlon occurred, although this question is also

one of fact.,, AtI of these opinions demonstrate the difficulty

of deciding whether or not the "clearly erroneous" rule governs

review of findings in discrimination cases. The Fifth Circuit's

appreciation of the fine distinction -- shown in its differentiation

between the ultimate finding of discrj:nination and the subsidiary

factual findings which underlie this finat determination (and

its deference toward the decisions of the trial court in regard

Eo the latter) -- certainly is not "sytnptomatic of a general disregard

. . . disregarrd for tlre proper allocation of restrrcnsibilities beBrreen

district, courts and eourts of appeals in deterrnining the

eristnce of discriminatory PurPose j.n Title VII case.s, " Pet. Brief

at fg-10.' Rather, it manifests special sensitividy t'oward

Sreservi.ng the proper spheres of relative autonomy for both

judicial levels, since it autborizes broad intervention only in

that facet of a diserirninati-on cases which involves matters of

Iaw.

The Seventh Circuit has also followed this hybri.d approach-

U.S. v. chicaqo and l]5g[@!}er, Egp53., (see p' 25 'l:ove) '

recognized the matter of law component in the question of discri:nination

and confirmed the Cireui!'s decision in Stewart v. General llotsors

gg -, 542 F.2d 445, 44g (7th Cir. , Lg'|l6), cert. denied, 433 u.s.

919 (Lg76), seh. denied, 434 u.s. 881 (L977), not to adhere Eo

the ."c1early erroneous" standard in reviewi.ng trial court

dete:minationg of discrimj:ratj-on. Independent examinatj-on of the

district coutrt,s interpretation of the subsidiary facts is therefore

ap-oropriate.

In contrast to this more moderate approach, the sixth

Circuit has taken a far lnore ir,terventionist Srcsition on the

nature of findings of ultimate fact. In Povner v. Lear Siegler, Inc.,

542 E.2d 955 (6th Cir. , Lg76), cert. denj-ed, 433 U.S. 908 (1976) '

a case concerning whether or not treatment as a corPorate ent5-ty

would lead- to an r:gfaj-r hardship, the court held tJrat:

The fact that a trial court labels determinations as

,'f5.ndings" does not make them so if they are i-n.reality

conclusions of 1aw. In that case, they are subject to

r:nrestricted review. . If a deternulnation concerns

whether the evidence showed that somethingi occurred or

existed, it is a fj-nding of fact. Eowever, if a determination

is made by processes of legal reasoning from, or interpretation

of the legal significance of, the evidenLiary facts, it is

30

j;':r,s-

l1

a maE,ter of law [cit'ing Galena Oaks, supra] '

at 959.

31

542 E.2d

It,: interesting to note how the Sixth Circuit transforms the

.Galeira.Oaks prescription. In Srlena Oaks, tile fifth Circuit

,,._

.-.: ^.. 3^e

had set forth a spectn:m of appropriate levels of revier'r for

findings of, subsidiary and ultimate fact (see section III e,

below, fo1- a more complete discussion of the spectn:m of review

approach.) 218 F.2d at z],g. Although it, exempted the application

Of legal standards frOm the "clearly'erroneous" requirement,

the Fifth circuit neve! went so far as to say that the question

involved solely legal matters. lhe Si.:<ttt Circuit has forcefully

exlnr:nded just such a position. In Detroit Police Officers'

Association v. Younq, 608 E.2d 67L (6th Cir', L979), 9931!3;!9!91!'

49 g.S.L.w. (1981), the Court specifically applied its

view to a discrimination. case. In holding that the district court's

findi.ng t6at there had been no showing of prior dj-scrimination

against blacks by the Detroit Police DePartment was "based on

errors of law and an impe:-nissably restrictive view of ttre

evidence," the Court of Appeals came right out to say that

,.whether prior discrirninaEion occurred is a co,nclusion of law [my

emphasisl based on subsidiary facts [citing U.S. v. Chicaqo, SE] '"

608 1..2d at 686. Eere too the Sixth Circuit goes beyond the

preced,ent on which it relies, since tlre Seventh Circuit in U-S- v-

Chicaqo found both factual and legal considerations in Ehe ultinrate

finding of discrj:aination-

Given the case law I've examined in Sections IlI A and B, I

thiltk it's accurate to say that the second' Third' Fifth' sixth'

Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits reflect, a general consensus

that, when treati.ng an ultimate issue of fact as .a question of

fact to which RuIe 52 (a) applies would preempt a.opellate consideration

\

\_)

:

V

-l

32

of the trial court's actual resolution of, the case, that ultimate

ttJ

(-: -EacE ought to be viewed as a matter of raw. The five circuj'ts

/.. which have addressed tlris problem in the cont,ext of discrj'rnination

Lr -! LL^

--?.- =--*aari =.Fq

treaturent for discrirnination cases is to treat them as matters

of law in which they have full Fowers of review.

PAPER CI\SESIMTNESS CREDIBILIT':T CASES

Both in tleose cases where it has justified adherence to

the ,,clearly erroneous" standard, such as 39-U@., gI.ry

Tank, aI Societv, and in those cases where it has

forrnd a broader scope of review appropriate, such as General

Motors and-. EelLgI,, the supreme court, has taken pai-ns to discuss

t}1e relative advantages of, trial and appellate courts i:t assessing

tlre evidence. The major difference is 5rcinted to in the language

of the Ru1e itself: ". and due regard shall be given to the

opportr^rnity of the trial court to judge of ttre credibility of

the witnesses-" While all cor:rts have'generally recognized that

this additional phrase does not mean that onlv in cases where

witness credibility is a cruciaL issue should the "clearly erroneous"

standard apply, many decisions suggest that the J:nlrcrtance of live

testimony should be taken into account in fixing the burden of

showiag "erroneousness" which the $PPellant must meet' In addition

to the ease law, tacit approval for this lrcsition can be gleaned

from the rejection of the 1955 proSrcsed amendment' to 52 (a) ' whj'ch

would have mandated equal standards for live and paper cases.

See p. 5 above.

{ Orvis v. }liqgins, 180 F.2d 537 (2d Cir-, 1950) , cert. denied, 340 U.S.

gIO (1950), was the first case to suggest that a spectrum of levels

of review was appropriate. [Whi1e Baumgartner had mentioned that

,

I

33

"[t]he conclusiveness of a 'finding of fact'depends on the nature

of the materials on which the finding is based," 322 u.S. at 670'

it neither specifically referred to the "cleirly erroneous' standard

.nor addressed the problerir in the context of ' the "dbcumenlaty" /"live"'

distinction we're concerned with here.J Faced with the Supreme

Court's placing "inferences drawn from document,s or undisputed facts"

firrnly within the protection of RUle 52(a) [Gvpsum, 333 U.S. at 3941 ,

Judge Frank stated that there $rere "approximate gradations" to be

made in the standard of review: "If [a trial judge] decides a fact

issue on written evidence aloner w€ are as able as he to determine

credibility and so we may disregard his finding." 180 F.2d at 539.

Whi1e Judge Frank I s position that an appellate court is completely

free to disregard a trial court's findings of fact in a case decided

on documentary evidence has been roundly criticized, many opinions

have discussed the appropriateness of a broader standard of review

in cases whictr- do not depend on demeanor evidence.

The General Motors.case, W., provides the Supreme Court's

clearest discussion of the question. The "rationale behind Rule 52 (a)

aS Set out in Oreoon Medical Societv, Supra, is "the trial court's

customary oPPortunity to evaluate the demeanor :td thus the

credibility of the witnessesr" the G.M. opinion declared. rn a case

where "of the 38 witnesses who gave testimony, only three appeared in

person [and] ICJhe testimony of the other 35 witnesses was submitted

either by affidavi.t, by deposition, or in the form of an agreed-upon

narrative of the testimony given in the earlier criminal proceeding

before another judge," 384 U.S. at t4I-2, fn.15, this rationale

disappe.ars and the reviewing court should not be as hesitant in

revewing in the trial court's decision as it normally might be. This

same c.M. footnote also provided the appellation 'paper cases" by

34

documentary cases have come better known.

,

majority of the. circuits have come to the conclusion that

paper cases are to some degreee or another less protected by the

..".cIear1.y erroneous" rule than '!1ive' cases' are.' Tle Second Circuitr'

as its leading case, orvis v. Higgins, .g3pgg.r__-indicates, has been

one of the most interventionist circuits. In United States ex re1.

Laskv v. LaVa11ee, 472 F.2d 960, 963 (2d Cir., L973), it reviewed

a habeas corpus action and, citing Orvis v. Eiggins with approval,

held that:

where the factual findings of the district judge are made

so1e1y on the basis of an interpretation of documentary

recorEs, and the credibility of witnesses is not in issue,

may make our own independent factual determination. "

Although it never explicitly refers to this factor, the opinion hints

that the court may also be influenced by the deprivation of rights

issues involved in a habeas petition. See Section fI B, above, for

a more detailed discussion of the special resPonsibility of appellate

courts in cases involving the deprivation of Constitutional rights.

The Fifth Circuit has also discussed the aPProPriateness of

a 'spectrum" approach. In Galena Oaks, -ggpg.r it said:

[T]he burden of showing a finding of fact "c1ear1y erroneous"

is- not a measure of exict an uniiorm weight. . The burden

is especially strong'when the trial court has had the

oppori,rrriEy,-not poisessed by the appellate court, to see and

helr the witnesse!, to observe their derneanor on- the stand,

and thereby t,he better to judge of their credibility. : ...

'3he burden is lighter, muc6 lighter, when we consider logical

inferences drawn from undisputed facts or from documents,

though .the "c1ear1y erroneous' rule is still applicable.

2I8 F.zd at 2t9.

Since the definition of "clear1y erroneous" in Glpsum.-is ultimately

so nebulous that-'the reviewing court 1Ue1 left with the definite

and firm conviction that a mistake has been mader'333 U.S. at

395 it should be clear that the Ga1ena Oaks formulation affords

an appellate court ample latitude in revewing PaPer cases. That

makes eminent sense in light of the whole PurPose behind Rule 52 (a) :

('"

(:

',

35

to the extent that an apPellate court has before it precisely

the same evidence as the trial court had had, its conviction

that a mistake has been made will certainly be firmer and more

definite than if it has to reconstiuct the materiAl from which

the trial court made its determination. I Ehink this concept

is crucial in understanding the "1ive case"/"paper case" distinction:

regardless of the appellate court's professions of inclusion in'

or exemption from, the "c1ear1y erroneous" rule, the threshhold for

reversal will inevitably be lower in paper cases, since the reviewing

court will be less inclined to ascribe a trial court's determination

withwhichitdisa9reestofactors''whiche1udeprint.,'9@,

322 at 670.

This analysis underlies the Fifth Circuit's later cases as

d

4gZ F.2d 508, 5L2 (5th Cir., Lg74), the Court explained that:

the presumptions under this rule normally accord.ed the

trial co,rr-t's findings are lessened where the evidence

consists of documentary evidence, dePosici.ons, and

"situationi where crediUility is not seriously involved

oEr if it is, where the reviewing court is in just as

good a position as the trial couit to judge credibility"'

5A tloore's Federal Practice {52.04 (2d Ed' 1969)

The circuiE confirmed its Qe facto adherence t,o this sPe-ctrum approach

in Jenkins v. Louisiana state Board of Educatlen, 505 F.2d,992

(5th cir., 1975), where, after stating that in a wholly documentary

case, 'the appellant's burden of showing that the triat court's

findings of fact are clearly erroneous is not as heavy as it would

be if the case had t.urned on the credibility of witnesses appearing

before the trial judger'the Court went on to state that it would

not ,,overturn the decision of the trial court unless !{e are lef t

with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been

t)

37

, declining to oPerate under it in this case, recognized that a

broader scope of review was aPproPriate in paper cases. AeEna

Casualtv and Suretv Co. v. llunt, 486 F.2d 81, 84..(lath Cir., 1173)

set out the Tenth Circuit's approach to PaPer.cases:

fn a series of cases, this court has held that in the

absence of oral testimony, the appellate court is equally

as capable as the t,rial court of examining the evidence

and drawing conclusions therefrom, and that we are under

a duty to do so. . [Documentary findings] do not

carry the same weight, on appeal as findings based entirely

an oral testimony. In dealing with all such documentary

evidence, the trial court is denied its normal advantage

.f an opportunity to judge the credibility of the

witnesses. . Though this lack of opportunity to

observe the witnesses estdblishes the appellate court's

duty to evaluate documentary evidence in an equal capacity

with the trial judger w€ are loath to overturn the

findings of a trial court unless they are clearly erroneous.

Jenninss v. General Medical Corp., 604 F.2d 1300, 1305-6 (I$th Cir,,

l)7)) reaffirmed this view.

i.+*

The Sixth, Eighth, and District of Columbia Circuits take a(.',

less cautious position and assert outright that the "c1ear1y

oneous' rule does not apply in many paper record cases. Inerr

' universitv llills, rnc. v. Pattqn , 42i F.2d 1094, 1099 (5th Cir. ,

1970), a case involving the question of contractual use restrictions

on some land tract,s, the Sixth Circuit declared that the

interpretation of written contracts was "not subject to the rule

and [is] wit,hin the competence of an appellate court.'l

Jn Frito-Lay, Inc. v. So Good Potato Chip Co., 540 F.2d 927,929,

(8th Cir., L976), the Eight Circuit held that "wherer ds here,

there is no dispute as to the evidence upon which the District Courtrs

findings are based, where there.are no credibility issues before

this Court. we are not confined by Ehe clearly erroneous standard

of review. " Final1y, in Owings v. Secretary of United SEates Air

Force, 447 F.2d L245, L255 (D.c. Cir. , L97L), the D.C. Circuit declared:

Note

the

38

We have Ehe same record before us that was before the ,

trial court and, since the district judge took no testrmony

and there wetre no issues of credibiliEy, we are in as

go"a a position as the trial court to determine what

inferenles should be drawn therefrom

in'all three cases how the "lega1 st,andirdsn'argument and

"paper case" argument overlaP.

Just as it did on the issue of whether a finding of discrimination

fal1swithin52(a)'sdefinitionof"findingoffact,"theFirst

Circuitrs Position on PaPer ca'ses Seems antithetitcal to t'hose

expressed ,by other circuits. In Custom Paper Products Co' v'

Arlantic Paper Box Co., 459 F.2d L78, L79 (I'st Cir., L972), the

Court said:

. . . tTl he basic principle remains the same: if a

dist,rict courtrs f indings, considering t,he recor_d as

a whoIe, whether based on live or other types of

evidence "ie reasonably 'suppor.led, they must stand.

id: -, .-j--

Given what seems to be a shif ting threshhold of er'roneousfrsss- necessary

to make a finding 'clearly' erroneous, however, the First Circuit's

approach does not ultimately differ too much from t'he mainstream'

The phrases "considering the record aS a whole" and "reasonably

supported" provide the same kind of escaPe hatch for appellate

judges eager to reverse a district court's finding as'a firm and

definite conviction that a mistake has been made- does' It will

always be easier to find something clearly erroneous when the

revewing court has a clear picture of what occurred during t'rial

than when it has only a hazy idea of what transpired below.

(rt's also interestirg, in light of Graver Tank and A&P, suPra,

that Custom Paper involved a patent issue')

In additiOn, both Manninq and sweeney, the cases in which

the First Circuit held that aisciimination was not the kind of

finding of ultimate fact which was exemPt from 52(a) , were cases