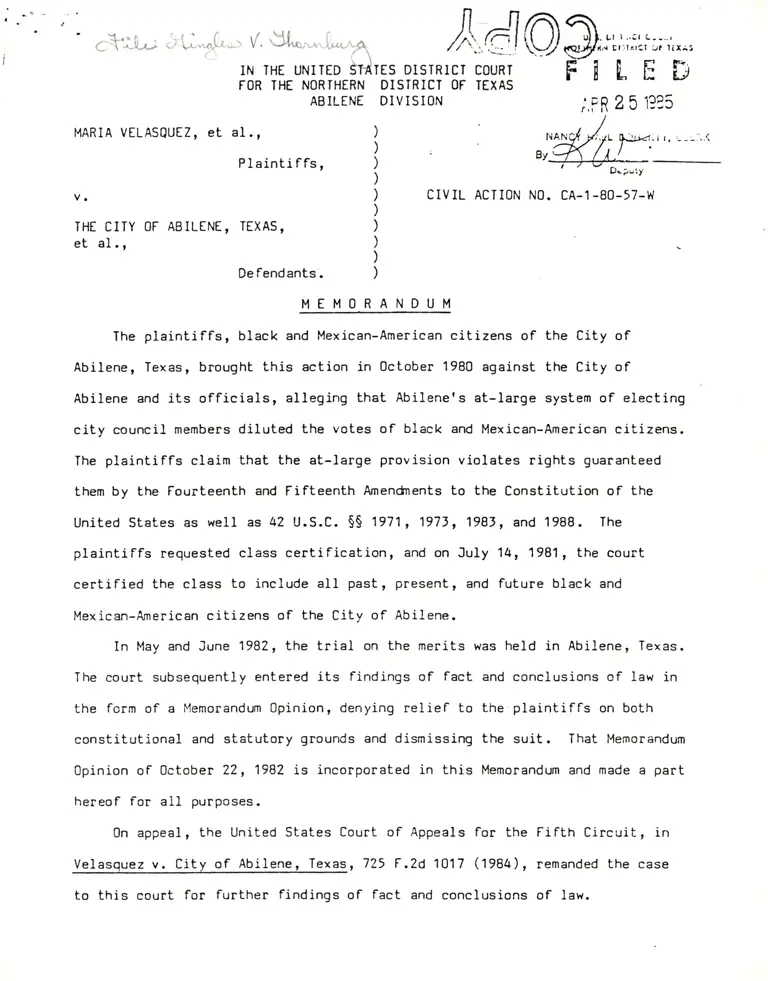

Velasquez v. City of Abilene Memorandum

Public Court Documents

April 25, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Velasquez v. City of Abilene Memorandum, 1985. 25f88294-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a28a3989-79b4-47d2-929c-d6abfc8fcca3/velasquez-v-city-of-abilene-memorandum. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

a .l

. I', i,- . ''.,.",(, /. 'i(" ,,,

^

IN THE UNITED STiIEs

FOR THE NORTHERN DI

ABILENE DI

MARIA VELASQUEZ, et aI., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

vo )

)

THE CITY OF ABILENE, TEXAS, )

et a1., )

)

Defendants. )

CIVIL ACIION NO. CA-1.80-57.W

DISTR

STR ICT

VISION

MEMORANDUM

The plaintiffs, black and Mexican-American citizens of the City of

Abilene, Texas, brought this action in 0ctober 1980 against the City of

Abilene and its officials, alleging that Abileners at-large system of electing

city council members diluted the votes ol black and Mexican-American citizens.

The plaintiffs claim that the at-large provision violates rights guaranteed

them by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendnents to the Constitution of the

United States as well as 42 U.S.C. $$ 1971, 197), 198r, and 1988. The

plaintiffs requested class certification, and on July 14,1981, the court

certified the class to include aI] past, present, and future black and

Mexican-American citizens of the City of Abilene.

In May and June 1982, the trial on the merits was held in Abilene, Texas.

The court subsequently entered its findings ofl fact and conclusions of law in

the form of a Memorandum Opinion, denying relief to the plaintiffs on both

constitutional and statutory grounds and dismissing the suit. That Memorandum

Opinion of October ??,1982 is incorporated in this Memorandum and made a part

hereof for all purposes.

0n appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in

Velasquez v. City of Abilene, Texasr 725 F.2d 1017 (1984), remanded the case

to this court for further findings of fact and conclusions of law.

aI 1,,..!rc--.r

(31-i,!itt,'r criliral irt Iixas

FILEE

;,?R 2 5 1??5

Accordingly, an additional evidentiary hearing was held on Februaty 21r 1985,

and the parties have now filed additional briefs and proposed additional

findings and conclusions. The court has reviewed and examined the transcript

of the original trial on the merits, as well as the pleadings, briefs, ad

arguments of aIl parties. This Memorandum shall constitute its additional

findirgs of fact and conclusions of law. /

Standards of liability in vote dilution cases

1. Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

The starting point for constitutional analysis of a voting system is

the rule announeed in City of Mobile v. Bo1den, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), that an

at-Iarge voting scheme is not per se unconstitutional. To state a

constitutional claim for dilution of minority votirg power, a plaintiff must

show that the at-large election system discriminates against persons beeause

of their race and that a discriminatory purpose at least in part pronpted

adoption of the at-Iarge system. Id. The courts are to look to certain factors

listed in Zimmer _v. @(eilhe1, 485 F.zd 1297 (5th Cir. 1975), afF'd on other

grounds sub nom., East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S.

6t6 (1976), in determining whether a given voting system is unconstitutional.

In the instant case, the court carefully considered all substantial

evidence presented, evaluated the evidence according to the Zimmer factors,

and concluded in light of all of the circumstances that Abilene's at-large

election scheme did not violate the Constitution of the United States. The

court's previous Memorandum contains the detailed discussion of facts and law

supporting its conclusion that no discriminatory purpose underlies Abilene's

election system, and further exposition of this determination is not

necessary.

The court reiterates its prior conclusion that the at-large election

system in Abilene, Texas passes constitutional muster. Therefore, the court

will devote the remainder of Lhis Memorandum to examination of the evidence in

light of the requirements of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, except for a brief

discussion below of a suggested discriminatory purpose behind the 196?

revision of the Abilene city charter.

?. Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended by Congress in 1982,

places a different burden on a plaintiff attempting to prove vote dilution.

To make out a case for statutory vote dilution, the plaintiff must either

prove "discriminatory purpose in the adoption or maintenance of the challenged

system of Isic] practice" or "that the challenged system or practice, in the

context of all the circtrnstances in the jurisdiction in question, results in

minorities being denied equal €rccess to the political process." S. Rep. No.

417,97th Cong., 2d Sess. ?7, replinted in 1982 U.5. Code Cong. & Ad. News

177 , ?O5. Congressional enactment of this results test in Voting Rights Act

cases is significant since it is easier for plaintiffs to show a

discriminatory effect oF an election system than it is to prove that a

discriminatory purpose underlies that system.

The Senate Report on the 1982 amendment to the Act suggests a list of

factors courts should consider in deciding whether a challenged election

system violates the Act. As noted in the report, the factors are derived

from the same Zimmer factors employed in a constitutional analysis of vote

dilution.

The factors include:

1. the extent of any history of official

discrimination in the state or political

subdivision that touehed the right of the members

of the minoriLy qroup to register, to vote, or

otherwise to participate in the democratic

process;

-5-

?. the extent to wtrich voting in the

elections oF the state or political suMivision is

racially polarized;

t. the extent to wtrich the state or

political subdivision has used unusually Iarge

eleetion districts, majority vote requirements,

anti-single shot provisions, or other voting

practices or procedures that may enhance the

opportunity For discrimination against the

minority group;

4. if there is a candidate slating

process, whether the members of the minority group

have been denied access to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the

minority group in the state or political

subdivision bear the effects of discrimination in

such areas as education, employment and health,

whi.ch hinder their ability to participate

effectively in the political process;

6. whether politieal campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the

minority group have been elected to p.rblic office

in the jurisdiction.

Additional factors that in some cases have

had probative value as part of plaintiffsl

evidence to establish a violation are:

whether there is a significant

lack of responsiveness on the part of

elected officials to the particularized

needs of the minority group;

whether the policy underlying the

state or political subdivision's use of

such voting qualification, prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice or

procedure is tenuous.

S. Rep. No.417 at 28-?91 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News al ?O6-?O7

( footnotes ornitted) .

Although the court addressed many of these factors in its previous

Memorandum in terms of the Zimmer considerations, it did not frontally

consider them in the manner suggested by the Senate report. The court will

mw discuss each of the factors, explaining in particular the evidence and

conclusions to be derived thereFrom concerning polarized voting, the Citizens

for Better Government and slatirg, effects of past discrimination, and the

196? revision of the Abilene city charter.

-4-

Application of Votinq Riohts Act factors

1. History of officiel dlscrimination

The court takes judicial notice of the fact that the State of Texas

has a long history of official racial discrimination stretehing from before

the Civil War to the 1960s. As described in the body and appendices of the

court's previous Memorandurn, Texas instituted a poll tax and for many years

maintained official barriers to prevent minorities from gaining access to the

political process.

As with other Texas cities during this period, AbiJ.en" adopied laws that

discriminated against persons because oF their race. 0ne of the plaintiffst

expert witnesses, Dr. Chandler Davidson of Riee University, recounted the

history of official discrimination in Abilene based on his exarnination of

newspaper articles and other historical sources. In 1919, the city passed an

ordinance requiring separate water coolers for blacks and whites in railway

stations and waiting rooms. Tr. 420. A 1942 ordinance prohibited sexual

interc-ourse or cohabitation between blacks and whites within the corporate

limits of the city. Tr.421. In 194r, an ordinance was passed segregating

elevators, imposing a $50 fine if it was violated. }|. Blaeks were not

allowed to use the city library, and both blacks and Mexican-Americans were

forced to play in segregated parks Lhat were inferior to the parks used by

whrites. jg. Cemeteries were segregated, and restrictive covenants concerning

race were in widespread use. Tr. 4?1-??, The Abilene publie schools were

adninistered by the city until 1957, and the evidence presented by the

plaintiffs clearly shows that Abilene schools were separate, but certainly not

equal, until they were integrated in the 1960s.

The court agrees with the plaintiffs that there is a history of past

ofFicial discrimination in Texas ard in Abilene itselF that affected minority

access to the democratic process.

-5-

Z. Racially polarized voting

The court approaches the evidence concerning polarized voting in

Abilene with Lhe caution suggested by Judge Higginbotham in Jones v. City of

Lubbock, 73O F.?d ?r, (5tn Cir . 1984) (Higginbotham, J. concurring). As one

would expect, distinguished experts with experience in voting rights

litigation testified on behalF of both the plaintiffls and defendants and

reached opposite conclusions regarding the existence of polarized voting in

Abilene.

Testifying for the plaintiffs, Dr. Davidson stated that there are three

techniques anployed by social scientists to identify polarized voting: bloc

voting analysis, regression analysis, and sample survey analysis. Dr.

Davidson by-passed the first two methods erd used a survey to study votirg

patterns in Abilene. He explained that he did not perform a bloc voting or

regression analysis for any period past 1970 because none of Abileners Voting

precinets contained a large enough majority oF blacks or Mexican-Americans

such that he could draw reliable conclusions usirq those methods. Tr.511.

Based on its understanding of the statistical techniques available to study

voting patterns, the court agrees that Abileners Fairly even distribution of

blacks and Mexiean-Americans among the voting precincts, at least since

1970, makes Abilene a poor subject for bloc votirq or regression analysis.

For the period before 1970, Dr. Davidson presented some evidence of

polarized voting in Abilene. He based his conclusion that voting in the 1950s

and 1960s was very polarized on examination of the overwhelmingly black

Preeinct J box located at Woodson School and a precirrct identified as

predominately populated by Mexican-Americans. Tr. 511. In the 1956 statewide

refererdum election, he found polarized voting on the issues dealing with a

proposed exemption from compulsory attendance at integrated schools, proposed

enactment of stricter anti-miscegenation Iarvs, and the interposition of states

-6-

rights doctrine. Tr. 51r-16. He reached a similar conclusion concerning the

1961 statewide reFerendum on repeal of the poll tax. He also stated that

there was polarized voting in the 196?r 1968, and 1970 school board elections.

Tr. 517-19.

The court agrees that Dr. Davidson's studies reveal some evidence of

polarized voting in the 1950s and 1960s. Although, as discussed below, the

court is skeptical as to the probative value of referendtrn eleetion results in

a polarized voting analysis, the voting results fron the 1956 and 1963

referenda elections show that voters in the l{oodson School precinct

disproportionately voted against exemption from mandatory attendarne, stricter

anti-miscegenation laws, and interposition and voted for repeal of the poll

tax as conpared to Taylor County voters as a whole.

This fact is some evidence oF polarized voting in the 1956 and 1967

refererdum elections, but the court is not strongly persuaded that the

plaintifFsr statistics are sound. Dr. Davidson's analysis compares one

Abirene precinct with vote totals in Taylor County, not just the city of

Abilene. This is not a fatal defeet, though, since Abilene constituted 90

percent of Taylor County during the period studied by Dr. Davidson. Tr. 510.

However, his eonclusions are speculative since the plaintiffs presented no

evidence oF voting results from a predominately white precinct in these same

elections so that a complete bloc voting analysis could be accunplished.

Instead, Dr. Davidson merely compared results frcrn Woodson School with Taylor

County as a rhole without identifying the racial composition of the county or

of its constituent precircts other than Woodson School. Neither did the

plaintiffs present any figures representing the population of the Woodson

Sehool precinct or any other Taylor County box, much less an identified

precinct within Abilene itself.

-7-

Serious credibility problems also arise regarding the plaintiffs'

evidence of polarized votirg in the 19621 1968, ard 1970 school board

elections. First, the plaintiffs presented no evidence concerning the issues

in those races, the qualifications oF the candidates, or any of the many other

factors that may have influenced the election. Second, the plaintiffs failed

to present any evidence oF voting results from predoninately white precincts

so that a cornparison with predominately minority precincts could be made and a

rigorous bloc voting analysis could be eompleted. Finally, the plaintiffs

failed to translate percentage of votes cast into actual number of votes so

that e cunparison of actual votes across the city could be made.

Even assuming that Dr. Davidson's studies oF voting in the 1950s and

1960s demonstrates polarized voting, evidence of votirq patterns in the 1970s

and beyond does not reveal polarization. Dr. Davidson based his conclusion

that Abilene voting is polarized on the results of surveys corducted aFter the

1979 city council race and the 1981 referendum on single-member districts.

Dr. Davidson employed surveys since there was rp precinct with sufficient

minority population to substantiate the results of bloc voting or regression

stud ies .

The plaintiffs claim that Hs. Mary Lujan's race for the city council in

1979 clearly reflects polarized voting. The court strongly disagrees and

finds to the contrary for several reasons. First, the survey employed by the

plaintiffls was not random in the way it identified black voters. Dr. Davidson

testified that a panel of persons selected blacks and Mexican-Americans oFf of

lists of actual voters to be surveyed. Tr, 659. 0nly one person on the

selection panel was someone other than a named plaintiff in this case, an

employee of West Texas Legal Services, Inc., or Ms. Lujan's canpaign

treasurer. Tr. 661. This hand-picking of minority survey subjects undermines

the randorn nature of the survey and raises serious doubts concerning the

-8-

validity of its results. Second, as the defendantsr expert, Dr. Del Taebel of

the University oF Texas at Arlirgton, testified, a post-election telephone

survey of voters is inherently suspect since voters may be particularly

secretive concerning their votes Following an election and may even Forget for

whom they voted. Tr.1?48. Third, nevrspaper publicity of the survey may have

skewed the results of the survey. Tr. 1251. Fourth, a survey eoncerning Ms.

Lujanrs campaign would not constitute reliable evidence of polarized voting in

Abilena, even assuming that it did exist, since she was not a serious

candidate. The uncontradicted evidence reveals that Ms. Lujan made no

campaign expenditures in her race, if eleeted would have been, at twenty-six

years of age, the youngest council person ever elected in Abilene, and was

only the seventh woman to ever run For the courrcil. Tr. 664-66. Furthermore,

she held only one campaign reception, started her campaign two weeks before

the eleotion, and even then did not actively seek election. Tr. 1?49-50.. It

does not surprise the court that Ms. Lujan was defeated. In fact, it is

remarkable that any relatively unkrpwn candidate who canpaigned as she did

would receive nine or ten percent of the vote. Because of these important

factors ignored in Dr. Davidson's survey, the court must wholly diseount any

conclusion of racially polarized voting gleaned from a study of Ms. Lujanrs

1979 council race.

The second survey presented by the plaintiffs to suggest racially

polarized voting examined the 1981 referendum on single-member districts

suhnitted to the voters after this suit was filed. In this survey, the

plaintiffs identified 157 Spanish surnamed persons, 119 blacks, and 41111

Anglos who actually voted in the election. From this group, the plaintiffs

obtained cornpleted surveys from 5f Spanish surnamed personsr 40 blacks, and

-9-

129 Anglos. 0f theser 9l percent of the Spanish surnamed,77 percent of the

blmks, and only 27 percent of the Anglos voted in fevor of single-member

districts. Tr.5tr-t4.

The plaintiffs argue that these results are conclusive indications of

polarized voting, but the court disagrees. First, as Dr. Taebel stated, a

referendtrn is rarely the proper subject for polarization analysis. Tr. 1?51.

The court rkrpwledged above that the racial referenda issues presented to

Texas voters Ln 1956 and 1967 nay be examples of the rare occasions in which

referenda can be classified as pro-minority or anti-minority issues. However,

the 1981 single-member district referendr,m does not appear to the court

inherently to have appealed to the racial consciousness or prejudice oF any

voter. Certainly there is no convincing evidence that the single-member

district refererdum was a racial minority versus racial majority issue

susceptible to polarization analysis. Second, there is a problem concerning

the sample size of voters used in the survey. IF the courtts calculations are

correct, the plaintiffs reached their conclusions of polarized voting oF

whites based on 1.14 percent or 129 of 41111 Anglo voters identified. When

compared with the results based on information from 11.76 percent or 53 of 157

Spanish surnamed voters identified and 28.78 percent or 40 of 119 black voters

identified, the small sample used to classify the Anglo vote may have

overstated the percentage of the Anglo vote against single-member districts.

Third, Dr. Davidson's referendum survey suffers from problems similar to those

present in his survey of Ms. Lujan's race discussed above. These shortcanings

relate to the random nature of the survey, possible bias in questions asked

over the telephone, and the impact of newspaper publicity. Tr. 1251. Added

together, these weaknesses in Dr. Davidson's survey of the 1981 referendurn on

single-member districts undermine his conclusions, ad the court finds that

his studies do not support a finding of polarized voting on racial lines.

-10-

The defendants' expert witness, Dr. Taebel, testified that polarized

voting along racial lines did not exist in Abilene. He based this conclusion

on two main facts. First, he stated that the evidence presented by the

plaintifFs did not demonstrate a pattern of polarized voting in Abilene

elections. Tr. 1?54. He noted that the plaintiffsr studies of Ms. Lujan's

1979 courpil race and the 1981 referendum election do not support a conclusion

oF polarized voting because of the fundamental failings of these surveys and

their Irck of adjustment For factors other than race that may have affected

the outcome of the elections. The court discussed Dr. Taebelrs criticism of

the plaintiffsf studies when those studies were described above and must agree

that the shortcomings he Iists undermine the persuasiveness of Dr. Davidsonts

determinations. Second, Dr. TaebeI explained that white voters voted

overr,fielmingly for minority candidates in four races. Tr. 1254. These

cournil racea involved 'th" following minority candidates: ltr. Joe Alcorta,

twice elected; Mr. Leo Scott; and Mr. Carlos Rodriguez. Tr.1254-55. He also

concluded that plaintiffsf Exhibit No. 12, entitled'!Percentage of Total Vote

Received by Minority Candidatesr" also demonstrates'rthat wlrites have voted in

significant numbers for minority candidates in several cases.rr Tr. 1?56.

This evidence of voting across racial lines directly contradicts the

definition of polarized voting generally accepted by political scientists.

In sum, there is evidence of racially polarized voting in Abilene's past,

but the plaintiffs have failed to demonstrate that there was racially

polarized voting in any election in the last fifteen years. The plaintiffsf

statistical studies of Ms. Lujan's 1979 council race and 1981 referendum

election suffer from the flaws Dr. Taebel noted, and the court must conelude

that those studies are not reliable. Further, the defendants, through the

testimony of Dr. Taebel, have proven a pattern of voting in Abilene revealing

that whites voted in significant numbers for minority candidates on numerous

-11-

oecasions. Far from showing a pattern of polarized voting as needed to

support the plaintiffsr claim, the evidence demonstrates m polarized voting

in recent times. Contrary to the conclusion urged by the plaintiFfs, and

based on consideration of a1l the substantial evidence, the court coneludes

that there is no credible evidence of a pattern of racially polarized voting

in Abilene.

Discriminatory voting practices and procedures

As stated in its previous Memorandum at 27-?8, the court recognizes the

potentially discriminatory efFects on minority voting power of the size of

Abilene, the majority vote requirement, numbered place system, and

geographical residercy requirernent. Clearly, the existence of these

procedures in Abilene's voting system makes this factor weigh in favor of the

plaintiffs, although the court also recognizes that there is easy access to

the campaign since there is no requirement for a petition in order for a

eandidate to be placed on the ballot. Stipulation No. ]0.

Slating and the Citizens for Better Government

The court agrees with the plaintiffs that a slating process for city

ofFicials can be used and manipulated in such a way that it would dilute the

votes of minorities. PlaintifFs, through Dr. Davidson, and other witnesses,

have presented evidence that the Citizens for Better Government (CBG) in

Abilene has dominated city politics and elections of city councilmen and

mayors for many years. The structure of the CBG is, as shown by the

evidence, as FoIIows:

A meeting, in which all interested citizens of Abilene were invited to

attend, would be held on a weekday, usual.l.y at noon. The citizens of each

election precinct would eLect a chairman, who in turn would automatically

serve on the board of directors of the CBG. The board oF directors would

designate a nominating cornmittee to solicit and select candidates, who rtould

-12-

be supported by the CBG at the next city electlon. The nominating committee

would report its recormendations to the executive board of the CBG. This

executive board could reject and change these nominations, and in fact did

reject some of the norninations during the period of its dorninarne. It is this

structure and method of endorsement t,hat plaintiffs assert to support their

theory of dilution. The evidence is uncontradicted that 9?.5 percent or 17 of

40 council seats up for election between 1966 and 1982 were won by

CBG-endorsed candidates. Tr. 5r9

Undoubtedly this process of CBG endorsement could be used to deny

minorities or others a meanirgful participation in city government, but the

question presented to this court is rrf,rether or not the CBG, through its

structural processes, did in fact diseriminate against minorities, or by its

acts, whether intentional or not, did dilute the votes of minorities.

It must be adnitted that the CBG, and its officials and executive

committee, used the structural processes to eliminate any candidates wtro did

not agree with the CBGrs political beliefs and philosophies. However, the

evidence refutes the theory that the CBG used these political structures as a

barrier to the election of minorities to the city council or as a means to

dilute the votes of minorities. Neither did the CBG operate in such a way as

to have those effects on minority votirq.

The evidence is unmistakable that during the 1970s, three members of

minority races, two Mexican-Americans and one black, were elected and served

on the Abilene City Couneil with the endorsement and support of the CBG.

The court further finds that these three would not have been elected in any of

these elections if the CBG had not endorsed and supported them.

It appears to the court, therefore, that the CBG's actions have supported

and increased the chances of blacks and Mexican-Americans to be elected in the

City of Abilene rather than to thwart the efforts of minorities to be elected.

-1t-

If CBG had used its power over city elections in the past to deny its

endorsement to a member of a minority race, srd had instead supported a

non-minority candidate, a minority would not have been elected. It was

because oF such CBG support that any minority has been elected to the city

council in Abilene.

The plaintiffs complain that the minorities selected were not to their

Iiking, yet the plaintiff English adniLted that on several occasions he voted

for the CBG-backed minority candidate. If these minority members of the city

council, elected with the support of the CBG, did not vote or act, after their

election, in accordance with the wishes of the plaintifFs or other minorities,

this cannot be blamed on the slating process of the CBG.

Plaintiffs' complaint in this case is not that minorities were

discriminated against by the CBG or that it was the intent of the CBG to

discriminate because of race or color. When examined closely, their complaint

is that the CBG refused to endorse somebody of a minority race who had a

political philosophy opposite to that of the CBG. In other words, it was

discrimination against persons because oF their politieal beliefs rather than

because of race.

The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution

and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended in 1982 prohibit discrimination

because of race or color and do not in any way attempt to tell any group of

citizens or individuals whom they must support, nor do they prohibit a group

of citizens from endorsing someone of their own political belieF, rrfrether that

person be Anglo, blak, or Mexican-American.

-14-

Minorities, as shown in the court's original Memorandun, were encouraged

to attend the meetirgs of the CBG, and in fact did so, even servirg on the

nominating committee. The fact that the CBG, through a majority of its

executive board at times, did not do the bidding of the minorities is not

proof of racial discrimination.

The courtrs discussion of slating thus far has dealt with the CBG during

its period oF dqninance over Abilene local elections. Although the CBG was

extraordinarily successFul in slating candidates and electing them to ofFice

between 1956 and 198?, CBG hegemony in Abilene ended abruptly in 1982. Since

that time, the mood among the electorate in Abilene has been decidedly

anti-CBG. Transcript of February 2111995 hearirg at 85 [hereinafter cited as

Tr. Part II]. In 1981 and 1984, the CBG-endorsed candidate was the winner in

only one of the five races conducted during that period. Tr. Part II 54. In

1984, the CBG did not slate candidates prior to their announcing for office,

but endorsed several candidates afLer they anrnunced. Tr. Part II 58. In

1985 , the CBG did not hold an annual meeting, did not field a slate of

carrdidates, and made no endorsements For city council. Stipulation No.93.

Several witnesses testified that the CBG is dead in Abilene, and a strong mood

toward electing independent candidates has replaced a tendercy built up over

sixteen years to support the CBG candidate.

After considering all of the evidence of slating in Abilene, the court

concludes that the efflect of slating was not to discriminate against

minorities or dilute their voting strength. During the period of CBG

dominance, minorities had fair access to the slating process and could

influence the selection of persons to be slated. Since the FaIl of the CBG,

minorities are able to support independent candidates wlro are responsive to

their needs. This too is an open process that does not offend either the

Constitution or the Voting Rights Act.

-15-

EfFects of past discrimination

As indicated previously in this opinion, official discrimination has

existed in Abilene in the past. Also, as discussed in the court's previous

Memorandum at 19, there is a disparity in Abilene in minority voting

registration and turrput as cqnpared to whites. This condition exists even

though there has been no statutory or constitutional impediments to minority

participation in voting since 1968. Stipulation No. 9. The court further

finds that the socio-eeonomic status of minorities in Abilene is lower than

that of whites, with minorities having lower median number of years of

schooling, lower percentage of high school and eollege graduates, and lower

median income. In eddition, more minority families live below the poverty

line,live with more persons per room, and inhabit less valuable houses than

do their white counterparts. Finally, the unemployment rate for minorities is

higher than that for whites.

Admittedly, there is a disparity between the relative socio-economic

statuses of whites and minorities in Abilene. However, there was no evidence

presented to the court of lingering discrimination beyond the mere statistics

concernirg Abilene's minorities or any facts presented linking this disparity

to the eleetion system used in Abilene. The court finds that there is no

persistent diserimination in Abilene concerning education, employment, and

health wtrich prevents minority citizens from Full access to the political

procegs.

Racial appeals in political campaigns

There was no evidence presented in the trial of this ease of any overt

racial appeal in any election since the 1960s. The plaintiffs did present

evidence of frustration of their involvement in the political process. One

plaintiff filed for county office and was treated rudely by the clerk. Tr.

177. Another plaintiff testified that she was harassed rrfren she ran for

-16-

office , It. )25, and her husband stated that his property u,as repeatedly

damaged when she campaigned for office. Tr. t61. Finally, there was evidence

that several minority candidates received threatening telephone caIls. The

court does not doubt that each ol these instances occurred, but there is

evidence that other minorities may in part have been responsible for the

threatening calls, Tr. Part lI 7r-74, and certainly it is possible that they

took part in damaging property as well. There was no evidence in the record

of actual instances oF prejudicial action other than these instances. There

was no direct evidence thet this conduct was raeially motivated, and the court

holds that these isolated events do not demonstrate a pattern of overt or

subtle racial appeals in Abilene politics.

Election oF minorities to office

Between 1885 and 1971, no minorities were elected to the city council.

From 1950 to 1970, no blrck or Mexican-American ran for the council.

Stipulation No . 4r. Since 197r, two Mexican-Amerieans and one black have been

elected.

Lack of responsiveness

In its previous Memorandtrm at 9-18, the court made detailed Findings that

elected city officials in Abilene were responsive to the needs of the minority

community. There is no need to elaborate further on the provision of

governmental services to the minority community or the distribution of

municipal jobs and appointments to various city boards. There is ample

evidence in the record to show that the city government in Abilene is

responsive to the concerns of minority citizens despite the subjective

testimony of several plaintiffs and their witnesses that city services are

unsatisfactory. In fact, in a survey conducted by the defendantsr expert, Dr.

Taebel, minorities rated city servicestrmore than satisFactory" more so than

did Anglos in all but two survey categories. It. 1242.

-17 -

One issue worthy of separate consideration concef,ns the responsiveness of

CBG-endorsed cournil members to the minority conmunity. The plaintiffs argued

that those members, Leo Scott, Joe Alcorta, and Carlos Rodriguez were mere

token candidates and could not truly represent minority interests. They

criticized Mr. Scott because he signed a letter in favor of limiting funding

to West Texas Legal Services. They also suggested that Mr. Alcorta ard Mr.

Rodriguez were not familiar with the problems of the Mexican-American

cornmunity and were not sensitive to the needs of minorities.

The court recognizes that the plaintiffs did not support the three

CBG-endorsed minority candidates and that they would have endorsed other

persons if they had possessed the CBG's slating power. However, the Voting

Rights Act does not guarantee the election of the candidate of onets choice.

Instead, it ensures that the election process does not discriminate against

Persons because of their race and deprive them of the right to vote for the

candidate of their choice. The court finds that the three minority candidates

who were endorsed by the CBG and served on the city council were responsive to

minority concerns and were eFfective council members. Each eandidate stated

that he tmk his oath of office very seriously ard conscientiously attempted

to represent all of the citizens of Abilene to the best of his ability. Tr.

1112, 11t+4-46, 1161. Mr. Rodriguez was particularly active in minority

affairs, having served as chairman of the Abilene Chapter of the League of

United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) Tr. 1?r4. While head of Abilene's

LULAC chapter, Rodriguez eriticized the school district's attitude toward

Mexican-Americans. Tr. '1165. The plaintiffs presented no evidence to prove

that these men were mere tokens and failed to represent their constituencies.

In fact the credible evidence is to the contrary.

-1 8-

fenuousness

Despite the courtrs dicta in Jones v. City of Lubboekr T?7 F.2d tG4,

,8t (5th Cir.1984), that it "doubt[s] that the tenousness factor has any

probative value for evaluating the rFairness' of the electoral systernts

impact r'r the court is obliged to consider the motivations underlying Abilene's

eldctoral system in an efFort to comply with the guidelines suggested in the

Voting Rights Actrs legislative history.

The plaintiffs' main attack under this topic concerns the 1962 revision

of the city charter and its acccrnpanying modifications of the election system.

The court finds that Abilene's election system is not based on a tenuous

public policy. The plaintiffs concede that Texas law in Article 11, section 5

of the Constitution and Article 1175 of the Revised Statutes empowers a home

rule city such as Abilene to select whichever form of government it wishes.

Although the reasons underlying the 1962 revision are uncl.ear, it appears from

the testimony of Judge Bryan Bra6ury, the revision cormission chairman, that

the purpose was a sincere desire to make Abilene's city government more

democratic.

Discriminatory intent behind 1952 revision

The parties to this suit strongly disagree as to the possibility of

discriminatory intent in the adoption of the 1962 revision despite their

stipulation thatrfnone of the approved amendments to the 1952 charter are

germane to any issue in this case and no challenges are raised by any party to

them." Stipulation No. ?6. But notwithstanding this stipulation, the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in its opinion very clearly

directed this court to study this matter further. The plaintiffs argue that

the 1962 revision was enacted based on a racially discriminatory intent. They

note that 1962 was a year oF high racial tension and that it was well known at

that time that the voting mechanisms enacted served to dilute minority voting

-1 9-

strength. The plaintiffs also note that all of the members of the revision

corrmissionwerewhiteardarguethatthisinsomewaydemonstratesa

discriminatoryintent.Theplaintiffsplaeespecialemphasisontwo

statements made by members of the conmission to show discriminatory intent'

First,theypointtoastatementmadebyMr.HudsonSmart,vieeehairmanof

the conmission, who stated that the runoff provision was desirable since all

elective county, state, and national officer elections provide for runoffs'

Tr. 600. secord, they note a statement made by Judge Bryan Bradbury, chairman

ofthecommission,thatthepurposeoftherunofFprovisionwastokeepa

minority from gaininq control of city government' Tr' 605'

Dr.Davidson,plaintiffs,expertwitness,citesheadlinesintheAbilene

newspaper in 196O-1962 and the votes on referendum issues in 1960 as evidence

that there was racial motivation behind these charter amendments and for

preservirrgEheat-largesystemofelectingcitycouncilmembers.Defendants

correcllypointoutthatthesenewsPaperarticleswerenotfrontpagebanner

nheadlines'r, but were stories appearing in the first section of the papero

Most of these headlines merely recount events during the civit Rights movement

intheearlylg60s,aditdoesnotappearthattheyindieateracia}biasof

any widesPread extent in Abilene'

The testimony ofl Dr. Taebel directly refutes the plaintiffs' contention

that reforms such as those enacted by the revision cormission in 1962 were

widelyknowntobediscriminatoryatthattime.Hestatedthatthiseffect

was not even krpwn to political scientists and goverrment scholars until after

a 1965 study of the impact of place-voting requirements by Professor Roy

Young. Tr.1226. He alsO stated that most revision cormission members he had

workedwithwerefairlynaiveintheirselectionofelectionsystemssothata

discriminatory PurPose was unlikely' Tr' 123''

-?o-

Thereisabso}utelynoevidencelinkingthefactthatalloftherevision

cormission members were white to any discriminatory PUrPose behind the

revision.Thecourt,therefore,dismissesthiscontention.

The court finds that Mr. smert's statement concerning local, state' and

national election runoff provisions does not show discriminatory intent' It

is true that runoffs are not required in general elections' However, they are

generally required in primary elections in Texas, and it is possible that i'lr'

smart was reFerring to these when he made the statement' Regardless of this

fact, the plaintiffs made no showing that his statement was a deliberate

falsehood designed to hide a discriminatory intent behind the proposed charter

rev ision .

while it is true that Judge Bryan Bradbury, the chairman of the charter

revision conmission, made the statement that the revision would ensure that a

minority would not be elected, the court finds that this statement did not

:

refer to racial minorities but rather to political minorities' T'here was a

desire, as shown by Judge Bradbury's testimonyt that any Person elected to the

:

Abilene City Courcil would have received a majority of the votesrat some city

election, either in the primary or in the runoff, and would ensure that a city

council member would not take his seat until ard unless such a majority was

received.

Two other important pieces of evidence sullgest that racial discrimination

was not a factor behind the revision. First, the proposed revised charter

included Section 1}6, a provision that prohibited discrimination in city

employment because of race. Accordirq to Dr. Taebel, the Abilene charter is

the only one out of over one hundred charters that he had studied that

contained such an equal employment provision. Tr ' 1221 ' The adoption of

Section 1f5 as part of eleet,ion system revisions strongly suggests t'he lack oF

a discriminatory motivation for the revision. secord, the revision also

-21-

increased the number of council seats from four to six' making the election ot

aminoritymore}ikelythanwhenthecouncilwasgnaller.Tr.lL?a.This

supports the conclusion that the revisions were not improperly motivated'

The testimony tendered by the deFendants in this case concernirg Lhe 1962

charteramendmentelectionismorereasonableandbelievablethanthe

testimony of plaintiffs in this respect. For that reason, the court finds

that the charter commission and the voters of Abilene in 196? ' in voting 0n

thecitycharteramendnents,werenotmotivatedbyanydiscriminatoryintent

against blacks or Mexican-Americans, and that the effect of the enendments are

not discriminatorY at this time'

Conclusion

The court has carefully considered all of the evidence presented in this

ease as weII as the briefs and arguments subrnitted by the parties' Based on

carefu}studyofthismaterialinlightoFal}ofthecircumstances

surroundirg the system of city elections in Abilene' the court determines that

there has been no violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments or the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 '

ThereisnoeasychecklistofFactorsorothercalculusthatatrial

court ctrl use in determinirg whether a challenged voting system discriminates

against persons because of their race' The legislative history of the voting

Rights Act suggests certain factors which the court has here employed, but in

theendrthecourtmustconcluder'rlrethervotedilutionhasoccurredbasedon

an extensive examination of the social, historical' and political forces

surrounding the challenged electoral system'

The court has made such an exhaustive study in the case of city elections

in Abilene, Texas and concrudes that the at-large system does not discriminate

against minority voters in Abilene because of their race' As discussed in the

previous Memorandum and in the section dealing with the 1962 charter revision

-22-

in the present Memorandum, the court concludes that there was no discri-

minatory intent behind the adoption or continuation of Abilene's system of

electing city council members and the mayor. Further, Abilene's eleetion

system does not have the effect of discriminating against minorities. The

plaintifFs in this case and the cl.ass they represent had and continue to have

an equal opportunity to elect persons whon they believe will best represent

their interests. The plaintiffs conplain that past members of the Abilene

City Council, both Anglo and minority, were not to their liking. However,

neither the Constitution of the United States nor the Voting Rights Act

guarantees any voter that the candidate of his choice will be elected. The

law requires that all persons have an equal opportunity to vote for the

candidate of their choice and to not have their vote illegally diluted.

Abilenets system of erections provides this opportunity to arl of its

citizens, minority and norpminority alike, and is therefore constitutionally

and statutorily permissible.

A judgment will be entered in accordance with the above.

The clerk wirl furni,sh a copy hereof to each attorney.

ENTERED Lhi, AbY^y of April , 1e85.

i:.';l=I:::.f 0 . li30}l?Ats.i

Chief Judge

Northern District of Texas

-2t-