Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 27, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Joint Appendix, 1984. f9996150-d992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a6addda0-2f61-4713-9f8e-f6be8d4e5e2a/joint-appendix. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

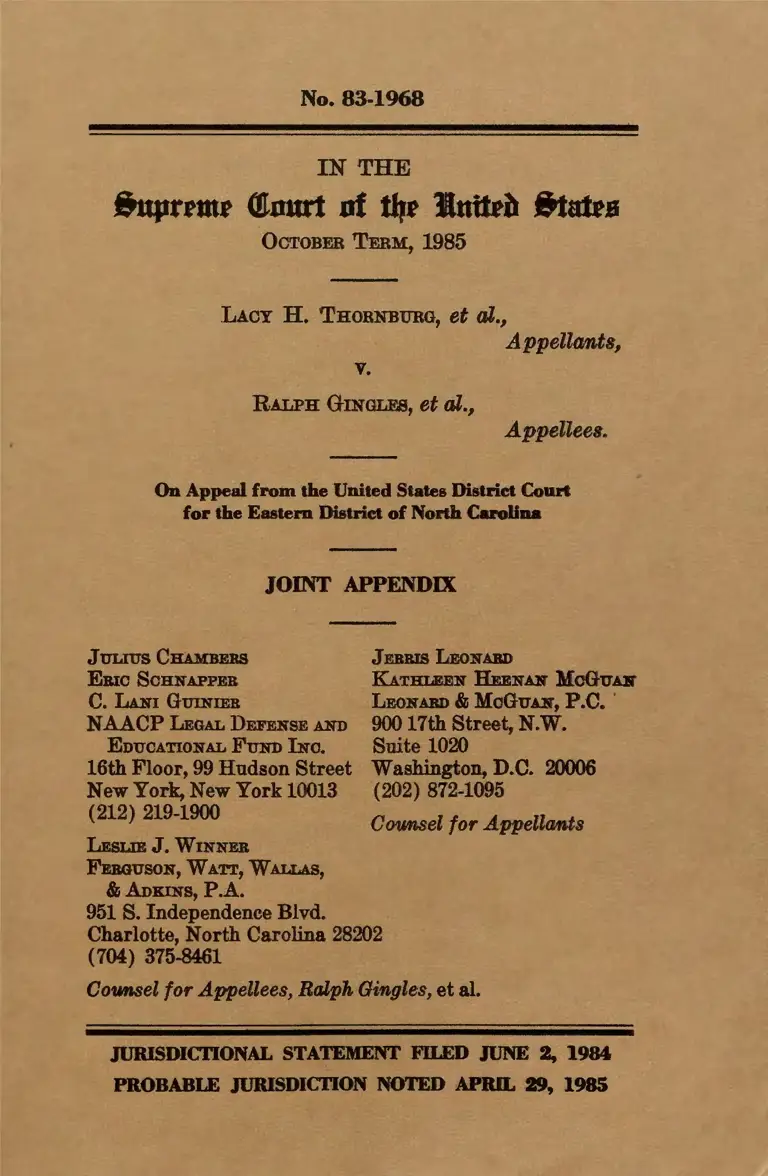

No. 83-1968 .

IN THE

&uprrmt C!tnurt nf tlft 1lnitt~ &tatts

OcTOBER TERM, 1985

LAcY H. THORNBURG, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et aZ.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastem District of North Carolina

JOINT APPENDIX

JULIUS CHAMBERS

Emc ScHNAPPER

c. LANI GUINIER

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FuND INc.

16th Floor, 99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

LESLIE J. WINNER

FERGUSON, WATT, WALLAS,

& ADKINS, P.A.

JERRIS LEONARD

KATHLEEN HEENAN MoGuAli

LEONARD & McGuAN, P.C. ·

900 17th Street, N.W.

Suite 1020

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 872-1095

Counsel for .Appellants

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

( 704) 375-8461

Counsel for .Appellees, Ralph Gingles, et al.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT FILED JUNE 2, 1984

PROBABLE JURISDICTION NOTED APRIL 29, 1985

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF RELEVANT DocKET ENTRIES . JA-1

ORDER oF THREE-JuDGE CoURT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-3

MEMORANDUM OPINION OF THREE-JUDGE CouRT . . . . . J A-5

STIPULATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-59

ExcERPTS FRoM TRANSCRIPT oF TRIAL BEFORE THREE-

JUDGE CoURT . . .......... .. .. . ... .. .. ... .. .. . . JA-119

Witnesses:

Bernard N. Grofman . ... . .. .. .... . .. .... . JA-119

Direct Examination .. . ....... ... .. . . . .. JA-119

Cross Examination .. . .. ... . .. .. . . . . . ... JA-143

Redirect Examination .. . ....... .. . . . .. . JA-152

Harry Watson . ... . .. . . ... . .. .. .. . . . .. . . . JA-156

Direct Examination .. ..... . . . . . ...... . . JA-156

Paul Luebke ... ... . . . .. .. . . . . .. . . . . .. .. .. JA-160

Direct Examination ... ... .... .......... J A-160

Cross Examination .... . . ... . .. . ... .. . . . JA-168

Phyllis D. Lynch ... ... ........ ... .. ...... JA-174

Direct Examination . .. .. ... . . . .. . . ... .. JA-174

Cross Examination . . ... ... . . .. ... . ..... JA-183

Samuel L. Reid .... . . . ... .. .. . . . .... . .. .. JA-193

Direct Examination . .. .. . .. ... . . . ... . .. JA-193

Cross Ex.Lmination . .. . . .. .. ... . ... . .. . . J A-194

11

TABLE oF CoNTENTS continued

Page

Robert W. Spearman .... .... ............. JA-198

Direct Examination .. ...... . .... .. ..... JA-198

Cross Exaillination ...... . .... ... . ...... JA-199

Larry Little . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-201

Direct Examination ...... . ... ...... . . . . JA-201

Cross Examination ...... . ........ . .. ... JA-206

Willie Lovett ... .......... ............... JA-210

Direct Examination .............. . ..... JA-210

G, K. Butterfi(>ld, Jr .......... . .. . . .. . .... JA-215

Direct Examination .... ......... ... .... J A-215

Fred Belfield, Jr .......... .. .... .. ... .... JA-228

Direct Examination .... ... ......... .. . . J A-228

Joe P. Moody . ............... .. ........ .. JA-232

Direct Examination ................. . .. JA-233

Theodore Arrington .. ............. . .... . . JA-233

Direct Examination ............. .... ... JA-233

Frank W. Ballance, Jr ........ .... .... .. . . JA-237

Direct Examination .............. . ..... JA-237

Cross Examination ..................... J A-246

Leslie Bevacqua ... . .. .... ..... . .......... JA-248

Direct Examination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-248

Ill

TABLE oF CoNTENTS continued

Page

Marshall Arthur Rauch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-249

Direct Examination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-249

Cross Examination ..................... JA-252

Louise S. Brennan ....................... JA-255

Direct Examination .................... JA-255

Cross Examination .... . ................ JA-262

Malachi J. Green ....................... .. JA-266

Direct Examination .................... JA-266

Recross Examination ................... J A-269

Examination .................. . ....... J A-269

Arthur John Howard Clement, III .. .. .. .. JA-270

Direct Examination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-270

Alloen Adams ................... .. .... .. . JA-271

Direct Examination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . J A-271

Thomas Brooks Hofeller ........ . ......... JA-275

Direct Examination ......... . . . ...... . . JA-275

Cross Examination ......... . ....... . ... J A-277

Date

JA-1

CHRONOLOGICAL UST OF

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

Documents

9.16.81 Complaint

10.16.81 Designation of Three-Judge Court

11.13.81 Plaintiff's Motion to Supplement Complaint

11.19.81 Order Allowing Supplement of Complaint

1.29.82 Defendant's Motion to Consolidate with

No. 81-1066-Civ.5

2.18.82 Order Consolidating No. 81-803-Civ.5 with

No. 81-1066-Civ.5

3.17.82 Motion to Certify the Class

Motion to Further Amend the Complaint

3.25.82 Order Allowing Second Supplement to Complaint

3.29.82 Answer To Second Supplemental Complaint

4.02.82 Stipulation of Class Action

4.22.82 Motion for Voluntary Dismissal of Claim as to

N.C. Districts for the United States Congress

4.23.82 Application for Hearing on Preliminary

Injunction

4.27.82 Order Granting Motion for Partial Voluntary

Dismissal

4.30.82 Hearing on Temporary Restraining Order

5.03.82 Motion for Temporary Restraining Order

Denied

5.12.82 Motion to Consolidate 82-545-CIV-5 with

81-803-CIV-5 and 81-1066-CIV-5

7.26.82 Order Consolidating 82-545-CIV-5 with

81-803-CIV-5 and 81-1055-CIV-5

Date

JA-2

DocKET ENTRIES (Cont.)

Documents

8.18.82 Motion to File Third Supplement on Amended

Complaint

9.03.82 Answer to Third Amended Complaint

9.29.82 Order Allowing Third Amended Complaint

12.22.82 Plaintiff's Motion for Summary Judgment

1.18.83 Defendant's Cross-Motion for Summary

Judgment

7.14.83 Pre-Trial Order

Pre-Trial Conference

7.21.83 Gingles Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Brief

Pugh Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Brief

Defendants' Pre-Trial Brief

7.21.83 Motion by Plaintiffs in 81-1066-CIV-5 To

Intervene In Trial of 81-803-CIV-5

7.22.83 Order Withdrawing Previous Order which con

solidated 81-1066-CIV-5 with 81-803-CIV-5;

Trial of 81-1066-CIV-5 continued without prej

udice of plaintiffs to intervene in trial of

81-803-CIV-5.

7.22.83 Motion to Intervene Granted

7.25.83 Trial Before Three-Judge Court (8 Days)

9.22.83 Order entering Summary Judgment in favor of

Defendants In 82-545-CIV-5

10.07.83 Plaintiff's Proposed Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law

10.07.83 Defendants' Proposed Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law

1.27.84 Memorandum Opinion and Order

2.03.84 Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court

JA-3

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

No. 81-803-CIV-5

RALPH GINGLES, et al.

vs.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, et al.

Plaintiffs,

Defendants.

FILED

JAN 27 1984

J. RICH LEONARD, CLERK

U.S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. NO. CAR.

ORDER

For the reasons set forth in the Memorandum Opinion of the

court filed this day;

It is ADJUDGED and ORDERED that:

1. Chapters 1 and 2 of the North Carolina Session Laws of

the Second Extra Session of 1982 (1982 redistricting plan) are

declared to violate section 2 of the Voting rights Act of 1965,

amended June 29, 1982, 42 U.S. C. § 1973, by the creation of

the following legislative districts: Senate Districts Nos. 2 and

22, and House of Representatives Districts Nos. 8, 21, 23, 36,

and 39.

2. Pending further orders of this court, the defendants,

their agents and employees, are enjoined from conducting any

primary or general elections to elect members of the State

Senate or State House of Representatives to represent, inter

JA-4

· alia, registered black voters resident in any of the areas now

included within the legislative districts identified in paragraph

1. of this Order, whether pursuant to the 1982 redistricting

plan, or any revised or new plan.

This Order does not purport to enjoin the conduct of any

other primary or general elections that the State of North

Carolina may see fit to conduct to elect members of the Senate

or House of Representatives under the 1982 redistricting plan,

or to elect candidates for any other offices than those of the

State Senate and House of Representatives. See N.C.G.S.

i20-2.1 (1983) Cum. Supp.).

3. Jurisdiction of this court is retained to entertain the

submission of a revised legislative districting plan by the de

fendants, or to enter a further remedial decree, in accordance

with the Memorandum Opinion filed today in this action.

4. The award of costs and attorneys fees as prayed by

plaintiffs is deferred pending entry of a final judgment, or such

earlier date as may be · shown required in the interests of

justice.

J. Dickson Phillips, Jr.

United States Circuit Judge

W. Earl Britt, Jr.

Chief United States District Judge

Franklin T. Dupree, Jr.

Senior United States District Judge

I certify the foregoing to be a true and correct copy of the

Order.

J. Rich Leonard, Clerk

United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

By Cherlyn Wells

Deputy Clerk

JA-5

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

No. 81-803-CIV-5

RALPH GINGLES, et al.

vs.

RUFUS 1. EDMISTEN, et al.

Plain tiffs,

Defendants.

FILED

JAN 27 1984

J. RICH LEONARD, CLERK

U.S. DISTRICT COURT

E. DIST. NO. CAR.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

Before PHILLIPS, Circuit Judge, BRITT, Chief District Judge,

and DUPREE, Senior District Judge.

PHILLIPS Circuit Judge:

In this action Ralph Gingles and others, individually and as

representatives of a class composed of all the black citizens of

North Carolina who are registered to vote , challenge on con

stitutional and statutory grounds the redistricting1 plan

1 For consistency and convenience we use the term "redistricting"

throughout as a more technically, as well as descriptively, accurate one than

the terms "apportionment" or "reapportionment" sometimes used by the

parties herein to refer to the specific legislative action under challenge here.

See Cantens v. Lcmnn, 543 F . Supp. 68, 72 n.3 (D. Col. 1982).

.TA-6

enacted in final form in 1982 by the General Assembly of North

Carolina for the election of members of the Senate and House of

Representatives of that state's bicameral legislature. Jurisdic

tion of this three-judge district court is based on 28 U.S. C.

§§ 1331, 1343, and 2284 (three judge court) and on 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973c.

The gravamen of plaintiffs' claim is that the plan makes use

of multi-member districts with substantial white voting ma

jorities in some areas of the state in which there are sufficient

concentrations of black voters to form majority black single

member districts, and that in another area of the state the plan

fractures into separate voting minorities a comparable con

centration of black voters, all in a manner that violates rights of

the plaintiffs secured by section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, amended June 29, 1982, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (Section 2, or

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act), 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1983, and the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments

to the United States Constitution. 2 In particular, the claim is

that the General Assembly's plan impermissibly dilutes the

voting strength of the state's registered black voters by sub

merging black voting minorities in multi-member House Dis

trict No. 36 (8 members - Mecklenburg County), multi

member House District No. 39 (5 members - part of Forsyth

County), multi-member House District No. 23 (3 members -

Durham County), multi-member House District No. 21 (6

members- Wake County), multi-member House District No. 8

(4 members - Wilson, Edgecombe and Nash Counties), and

multi-member Senate District No. 22 (4 members- Mecklen

burg and Cabarrus Counties), and by fracturing between more

than one senate district in the northeastern section of the state

a concentration of black voters sufficient in numbers and con-

2 The original complaint also included challenges to population deviations

in the redistricting plan allegedly violative of one-person-one-vote princi

ples, and to congressional redistricting plans being contemporaneously

enacted by the state's General Assembly. Both of these challenges were

dropped by amended or supplemental pleadings responsive to the evolving

course of legislative action , leaving only the state legislature "vote dilution"

claims for resolution.

:JA-7

tiguity to constitute a voting majority in at least one single

member district, with the consequence, as intended, that in

none of the senate districts into which the concentration is

fractured (most notably, Senate District 2 with the largest

mass of the concentration) is there an effective voting majority

of black citizens.

We conclude on the basis of our factual findings that the

redistricting plan violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act in

all the respects challenged, and that plaintiffs are therefore

entitled to appropriate relief, including an order enjoining

defendants from conducting elections under the extant plan.

Because we uphold plaintiffs' claim for relief under Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act, we do not address their other statutory

and constitutional claims seeking the same relief.

I

General Background and Procedural History

In July of1981, responding to its legal obligation to make any

redistrictings compelled by the 1980 decennial census, the

North Carolina General Assembly enacted a legislative

redistricting plan for the state's House of Representatives and

Senate. This original 1981 plan used a combination of multi

member and single-member districts across the state, with

multi-member districts predominating; had no district in which

blacks constituted a registered voter majority and only one

with a black population majority; and had a range of maximum

population deviations from the equal protection ideal of more

than 20%. Each of the districts was composed of one or more

whole counties, a result then mandated by state constitutional

provisions adopted in 1968 by amendments that prohibited the

division of counties in legislative districting. At the time this

original redistricting plan was enacted (and at all critical times

in this litigation) forty of North Carolina's one hundred coun

ties were covered by section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. § 1973c (Section 5, or Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act. ).

JA-8

Plaintiffs filed this action on September 16, 1981, challeng

ing that original redistricting plan for, inte1· alia, its population

deviations, its submergence of black voter concentrations in

some of the multi-member districts, and the failure of the state

to obtain preclearance, pursuant to Section 5, of the 1968

constitutional amendments prohibiting county division in

legislative districting.

After this action had been filed, the state submitted the 1968

no-division-of-counties constitutional provisions for original

Seeton 5 preclearance by the Attorney General of the United

States. While action on that submission was pending, the

General Assembly covened again in special session and in

October 1981 repealed the original districting plan for the state

House of Representatives and enacted another. This new plan

reduced the range of maximum population deviations to ap

proximately 16%, retained a preponderance of multi-member

districts across the state, and again divided no counties. No

revision of the extant Senate districting plan was made.

In November 1981, the Attorney General interposed formal

objection, under Section 5, to the no-division-of-counties con

stitutional provisions so far as they affected covered counties.

Objection was based on the Attorney General's expressed view

that the use of whole counties in legislative districting required

the use oflarge multi-member districts and that this "necessar

ily submerges cognizable minority population concentrations

into larger white electorates." Following this objection to the

constitutional provisions, the Attorney General further ob

jected, on December 7, 1981, and January 20, 1982, to the then

extant redistricting plans for both the Senate and House as

they affected covered counties.

In February 1982, the General Assembly again convened in

extra session and on February 11, 1982, enacted for both the

Senate and House revised redistricting plans which divided

some counties both in areas covered and areas not covered by

Section 5. Again, on April 19, 1982, the Attorney General

interposed objections to the revised districting plans for both

JA-9

the Senate and House. The letter interposing objection ac

knowledged some improvement of black voters' situation by

reason of county division in Section 5 covered areas, but found

the improvements insufficient to permit preclearance. The

General Assembly once more reconvened in a second extra

session on April 26, 1982, and on April 27, 1982, enacted a

further revised plan which again divided counties both in areas

covered and areas not covered by Section 5. That plan, embo

died in chapters 1 and 2 of the North Carolina Session Laws of

the Second Extra Session of 1982, received Section 5 preclear

ance on April30, 1982. As precleared under Section 5, the plan

constitutes the extant legislative districting law of the state,

and is the subject of plaintiffs' ultimate challenge by amended

and supplemented complaint in this action. 3

During the course of the legislative proceedings above

summarized, this action proceeded through its pre-trial

stages. 4 Amended and supplemental pleadings accommodating

to successive revisions of the originally challenged redistrict

ing plan were allowed. Extensive discovery and motion prac

tice was had; extensive stipulations of fact were made and

embodied in pretrial orders. The presently composed three-

3 The final plan's division of counties in areas of the state not covered by

Section 5 was challenged by voters in one such county on the basis that the

division violated the state's 1968 constitutional prohibition. The claim was

that in non-covered counties of the state the constitutional prohibition re

mained in force, notwithstanding its suspension in covered counties by virtue

of the Attorney General's objection. In Cavanagh v. Brock, No. 82-545-CIV-

5 (E.D.N.C. Sept. 22, 1983), which at one time was consolidated with the

instant action, this court rejected that challenge, holding that as a matter of

state law the constitutional provisions were not severable, so that their

effective partial suspension under federal law resulted in their complete

suspension throughout the state.

4 At one stage in these proceedings another action challenging the

redistricting plan for impermissible dilution of the voting strength of black

voters was consolidated with the instant action. In Pugh v. Hunt , No.

81-1066-CIV-5, also decided this day, we earlier entered an order of the

cleconsolidation and permitted the black plaintiffs in that action to intervene

as individual and representative plaintiffs in the instant action.

JA-10

judge court was designated by Chief Judge Harrison L. Winter

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit on

October 16, 1981. The action was designated a plaintiff class

action by stipulation of the parties on April2 , 1982. Following

enactment and Section 5 preclearance of the April 27, 1982,

Senate and House districting plans, the pleadings were closed,

with issue joined for trial on plaintiffs' challenge, by amended

and supplemented complaint, to that finally adopted plan.

Following a final pre-trial conference on July 14, 1983, trial

to the three-judge court was held from July 25, 1983, through

August 3, 1983. Extensive oral and documentary evidence was

received. Decision was deferred pending the submission by

both parties of proposed findings offact and conclusions oflaw,

briefing and oral argument. Concluding oral arguments of

counsel were heard by the court on October 14, 1983, and a

limited submission of supplemental documentary evidence by

both parties was permitted on December 5, 1983.

Having considered the evidence, the memoranda oflaw sub

mitted by the parties, the stipulations of fact , and the oral

arguments of counsel, the court, pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P.

52(a), enters the following findings of fact and conclusions of

law, prefaced with a discussion of amended Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act and of certain special problems concerning

the proper interpretation and application of that section to the

evidence in this case.

II

Amended Section 2 Of The Voting Rights Act

From the outset of this action plaintiffs have based their

claim of racial vote dilution not only on the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments, but on Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act. As interpreted by the Supreme Court at the time this

action was commenced, former Section 2, 5 secured no further

5 Former Section 2, enacted pursuant to Congress's constitutional enforce

ment powers , provided simply:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice,

or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political

(footnote continued on next page)

JA-11

voting rights than were directly secured by those con

stitutional provisions. To the extent "vote dilution" claims lay

under either of the constitutional provisions or Section 2, 6 the

requirements for proving such a claim were the same: there

must have been proven both a discriminatorily "dilutive" effect

traceable in some measure to a challenged electoral mechanism

and, behind that effect, a specific intent on the part of responsi

ble state officials that the mechanism should have had the

effect. City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980).

While this action was pending for trial and after the

ultimately challenged redistricting plan had been enacted and

given Section 5 preclearance, Congress amended Section 27 in

drastic and, for this litigation, critically important respects. In

rough summary, the amended version liberalized the statutory

vote dilution claim in two fundamental ways. It removed any

necessity that discriminatory intent be proven, leaving only

the necessity to show dilutive effect traceable to a challenged

electoral mechamism; and it made explicit that the dilutive

effect might be found in the "totality of the circumstances"

within which the challenged mechanism operated and not alone

in direct operation of the mechanism.

(footnote continued from previous page)

subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in Section 1973b(f)(2) of this title.

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (1976).

6 It is not now perfectly clear-but neither is it of direct consequence

here-whether a majority of the Supreme Court considers that a racial vote

dilution claim, as well as a direct vote denial claim, lies under the fifteenth

amendment and, in consequence, lay under former Section 2. See Rogers v.

Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 619 n.16 (1982). It is well settled, however, that such

claims lie under the fourteenth amendment, though only upon proof of intent

as well as effect. See City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980).

7 H.R. 3112, amending Section 2 and extending the Voting Rights Act of

1965, was passed by the House on October 15, 1981. On June 18, 1982, the

Senate adopted a different version, S. 1992, reported out of its Committee on

the Judiciary. The House unanimously adopted the Senate bill on June 23,

1982, and it was signed into law by the President on June 29, 1982. There was

no intervening conference committee action.

.JA-12

Following Section 2's amendment, plaintiffs amended their

complaint in this action to invoke directly the much more

favorable provisions of the amended statute. All further

proceedings in the case have been conducted on our perception

that the vote dilution claim would succeed or fail under

amended Section 2 as now the obviously most favorable basis of

claim. 8

Because of the amended statute's profound reworking of

applicable law and because of the absence of any authoritative

Supreme Court decisions interpreting it, 9 we preface our find

ings and conclusions with a summary discusson of the amended

statute and of our understanding of its proper application to the

evidence in this case. Because we find it dispositive of the vote

dilution claim, we may properly rest decision on the amended

statute alone and thereby avoid addressing the still subsisting

constitutional claims seeking the same relief. See Ashwander v.

Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 347 (1936) (Bran

deis, J., concurring).

8 Of course, the direct claims under the fourteenth (and possibly the

fifteenth) amendment remain, and could be established under Bolden by

proof of a dilutive effect intentionally inflicted. But no authoritative decision

has suggested that proof alone of an unrealized discriminatory intent to

dilute would suffice. A dilutive effect remains an essential element of con

stitutional as well as Section 2 claims. See Hartman, Racial Vote Dilution

and Separation of Powers: A n Explomton of the Conflict Between the

Judicial "Intent" and the Legislative "Results" Standards, 50 Geo. W.L.

Rev. 689, 737-38 n.318 (1982). Neither is there any suggestion that the

remedy for an unconstitutional intentional dilution should be any more

favorable than the remedy for a Section 2 "results" violation. Whether the

evidence of discriminatory intent might nevertheless have limited relevance

in establishing a Section 2 "result" claim is another matter.

9 There have , however, been a few lower federal court decisions interpret

ing and applying amended Section 2 to state and local electoral plans. All

generally support the interpretation we give the statute in the ensuing

discussion. See Majorv. Treen, Civil Action No. 82-1192 Section C (E. D. La.

Sept. 23, 1983) (three-judge court); Rybicki v. State Board of Elections, No.

81-C-6030 (N.D. Ill. Jaan. 20, 1983) (three-judge court); Thomasville Branch

of NAACP v. Thomas County, Civil Action No. 75-34-THOM (M.D. Ga.Jan.

26, 1983); Jones v. City of Lubbock, Civil Action No. CA-5-76-34 (N.D. Tex.

Jan. 20, 1983); Taylor v. Haywood County, 544 F. Supp. 1122 (W.D. Tenn.

1982) (on grant of preliminary injunction).

JA-13

Section 2, as amended, reads as follows:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or ap

plied by any State or political subdivision in a manner

which results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any

citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or

color, or in contravention of the guarantees set forth in

Section 4(±)(2), as provided in subsection (b).

(b) A violation of subsection(a) is established if, based on

the totality of circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open to participation

by members of a class of citizens protected by subsection

(a) in that its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of their choice. The

extent to which members of a protected class have been

elected to office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided, That

nothing in this section establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in numbers equal to their

proportion in the population.

Without attempting here a detailed analysis of the legisla

tive history leading to enactment of amended Section 2, we

deduce from that history and from the judicial sources upon

which Congress expressly relied in formulating the statute's

text the following salient points which have guided our applica

tion of the statute of the facts we have found.

First. The fundamental purpose of the amendment to Sec

tion 2 was to remove intent as a necessary element of racial

vote dilution claims brought under the statute. 10

10 Senator Dole, sponsor of the compromise Senate version ultimately

enacted as Section 2, stated that one of his "key objectives" in offering it was

to

make it unequivocally clear that plaintiffs may base a violation of Sec

tion 2 on a showing of discriminatory "results" , in which case proof of

discriminatory intent or purpose would be neither required , nor rele

vant. I was convinced of the inappropriateness of an ''intent standard"

(footnote continued on next page)

JA-14

This was accomplished by codifying in the amended statute

the racial vote dilution principles applied by the Supreme

Court in its pre-Bolden decision in White v. RegesteT, 412 U.S.

755 (1973). That decision, as assumed by the Congress/1 re

quired no more to establish the illegality of a state's ~lectoral

mechanism than proof that its "result," irrespective of intent,

when assessed in "the totality of circumstances" was "to cancel

out or minimize the voting strength of racial groups," I d. at 765

- in that case by submerging racial minority voter concentra

tions in state multi-member legislative districts. The White v.

RegesteT racial vote dilution principles, as assumed by the

Congress, were made explicit in new subsection (b) of Section 2

in the provision that such a "result," hence a violation of se

cured voting rights, could be established by proof "based on

the totality of circumstances . . . that the political processes

leading to nomination or election . . . are not equally open to

participation" by members of protected minorities. Cf. id. at

766.

Second. In determining whether, "based on the totality of

circumstances," a state's electoral mechanism does so "result"

in racial vote dilution, the Congress intended that courts

should look to the interaction of the challenged mechanism

with those historical, social and political factors generally sug

gested as probative of dilution in White v. RegesteT and sub-

(footnote continued from previous page)

as the sole means of establishing a voting rights claim, as were the

majority of my colleagues on the Committee.

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 193 (1982) (additional views of Sen.

Dole) (hereinafter S. Rep. No. 97-417).

11 Congressional opponents of amended Section 2 contended in debate that

White v. Regester did not actually apply a "results only" test, but that,

properly interpreted, it required , and by implication found , intent also

proven. The right or wrong of that debate is essentially beside the point for

our purposes. We seek only Congressional intent, which clearly was to adopt

a "results only" standard by codifying a decision unmistakably assumed

whether or not erroneously- to have embodied that standard. See Hartman,

Racial Vote Dilution, supra note 8, at 725-26 & n.236.

JA-15

sequently elaborated by the former Fifth Circuit in Zimmer v.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en bane) , affd on

other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) (per curiam). These typically

include, per the Senate Report accompanying the compromise

version enacted as amended Section 2:

1. the extent of any history of official discrimination in

the state or political subdivision that touched the right of

the members of the minority group to register, to vote, or

otherwise to participate in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the elections of the

state or political subdivision is racially polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or political subdivision

has used unusually large election districts, majority vote

requirements, anti-single shot provisions, or other voting

practices or procedures that may enhance the opportunity

for discrimination against the minority group;

4. if there is a candidate slating process, whether the

members of the mimority group have been denied access

to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the minority group

in the state or political subdivision bear the effects of

discrimination in such areas as education, employment

and health, which hinder their ability to participate effec

tively in the political process;

6. whether political campaigns have been character

ized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority group

have been elected to public office in the jurisdiction.

Additional factors that in some cases have had proba

tive value as part of plaintiffs' evidence to establish a

violation are:

whether there is a significant lack of responsiveness

on the rart of elected officials to the particularized

needs o the members of the minority gToup.

whether the policy underlying the state or political

subdivision's use of such voting qualification, prere

quisite to voting, or standard, practice or procedure is

tenuous.

JA-16

While these enumerated factors will often be the more

relevant ones, in some cases other factors will be indica

tive of the alleged dilution.

S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra note 10, at28-29 (footnotes omitted).

Third. Congress also intended that amended Section 2

should be interpreted and applied in conformity with the

general body of pre-Bolden racial vote dilution jurisprudence

that applied the White v. R egester test for the existence of a

dilutive "result. "12

Critical in that body of jurisprudence are the following prin

ciples that we consider embodied in the statute.

The essence of racial vote dilution in the White v. R egester

sense is this: that primarily because of the interaction of sub

stantial and persistent racial polarization in voting patterns

(racial bloc voting) with a challenged electoral mechanism, a

racial minority with distinctive group interests that are cap

able of aid or amelioration by government is effectively denied

the political power to further those interests that numbers

alone would presumptively, see United Jewish Organization v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 166 n.24 (1977), give it in a voting con

stituency not racially polarized in its voting behavior. See

Nevett v. Sides , 571 F .2d 209, 223 & n.16 (5th Cir. 1978). Vote

dilution in this sense can exist notwithstanding the relative

absence of structural barriers to exercise of the electoral fran

chise. It can be enhanced by other factors - cultural, political,

social, economic - in which the racial minority is relatively

disadvantaged and which further operate to diminish practical

political effectiveness. Zimmer v . McKeithen, supra. But the

demonstrable unwillingness of substantial numbers of the ra-

12 SeeS. Rep. No. 97-417, supm note 10, at 32 ("[T]he legislative intent [is]

to incorporate [White v. Regester} and extensive case law ... which de

veloped around it."). See also id. at 19-23 (Bolden characterized as "a marked

departure from [the] prior law" of vote dilution as applied in Wh ite v.

Regester, Zimmer v. McKeithen, and a number of other cited federal deci

sions following White v .. Regester).

JA-17

cial majority to vote for any minority race candidate or any

candidate identified with minority race interests is the linchpin

of vote dilution by districting. N evett v. Sides , supra; see also

Rogers v . Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 623 (1981) (emphasizing cen

trality of bloc voting as evidence of purposeful discrimination).

The mere fact that blacks constitute a voting or population

minority in a multi-member district does not alone establish

that vote dilution has resulted from the districting plan. See

Z immer, 485 F.2d at 1304 ("axiomatic" that at-large and multi

member districts are not per se unconstitutional). Nor does the

fact that blacks have not been elected under a challenged

districting plan in numbers proportional to their percentage of

the population. I d. at 1305. 13

On the other hand, proof that blacks constitute a population

majority in an electoral district does not per se establish that no

vote dilution results from the districting plan, at least where

the blacks are a registered voter minority. Id. at 1303. Nor

does proof that in a challenged district blacks have recently

been elected to office. Id . at 1307.

Vote dilution in the White v. Regester sense may result from

the fracturing into several single-member districts as well as

from the submergence in one multi-member district of black

voter concentrations sufficient, if not "fractured" or "sub

merged," to constitute an effective single-member district vot

ing majority. See Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 219 (5th Cir.

1978).

Fourth. Amended Section 2 embodies a congressional pur

pose to remove all vestiges of minority race vote dilution

perpetuated on or after the amendment's effective date by

state or local electoral mechanisms. 14 To accomplish this, Con-

1:3 This we consider to be the limit of the intended meaning of the disclaimer

in amended Section 2 that "nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in

the population." 42 U.S.C. § 1973.

l.J Both the Senate and House Committee Reports assert a purpose to

forestall further purposeful discrimination that might evade remedy under

(footnote continued on next page)

JA-18

gress has exercised its enforcement powers under section 5 of

the fourteenth and section 2 of the fifteenth amendments15 to

create a new judicial remedy by private action that is broader

in scope than were existing private rights of action for con

stitutional violations of minority race voting rights. Specifical

ly, this remedy is designed to provide a means for bringing

states and local governments into compliance with con

stitutional guarantees of equal voting rights for racial minori

ties without the necessity to prove an intentional violation of

those rights. 16

Fifth. In enacting amended Section 2, Congress made a

deliberate political judgment that the time had come to apply

(footnote continued from previous page)

the stringent intent-plus-effects test of Bolden and to eradicate existing or

new mechanisms that perpetuate the effects of past discrimination. See S.

Rep. 97-417, supra note 10, at40; H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.

31 (1981) (hereinafter H.R. Rep. No. 97-227).

We accept-and it is not challenged in this action by the state defendants

that Congress intended the amendment to apply to litigation pending upon

its effective date. See Major v. Treen, supra, slip op. at 40-41 n.20.

15 Both the Senate and House Committee Reports express an intention

that amended Section 2 be regarded as remedial rather than merely redefini

tional of existing constitutional voting rights. See S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra

note 10, at 39-43; H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, supm note 14, at 31.

16 Congressional proponents of amended Section 2 were at pains in debate

and committee reports to disclaim any intention or power by Congress to

overrule the Supreme Court's constitutional interpretation in Bolden only

that the relevant constitutional provisions prohibited intentional racial vote

dilution, and to assert instead a power comparable to that exercised in the

enactment of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act to provide a judicial remedy

for enforcement of the state's affirmative obligations to come into com

pliance. See , e.g., S. Rep. 97-417, supra note 10, at 41 ("Congress cannot

alter the judicial interpretations in Bolden ... . [T]he proposal is a proper

statutory exercise of Congress' enforcement power .. . . ").

No challenge is made in this action to the constitutionality of Section 2 as a

valid exercise of Congress's enforcement powers under the fourteenth (and

possibly fifteenth) amendment, and we assume constitutionality on that

basis. See Major v. Treen, supra, slip op. 44-61 (upholding constitutionality

against direct attack).

JA-19

the statute's remedial measures to present conditions of racial

vote dilution that might be established in particular litigation;

that national policy respecting minority voting rights could no

longer await the securing of those rights by normal political

processes, or by voluntary action of state and local govern

ments, or by judicial remedies limited to proof of intentional

racial discrimination. See, e.g., S. Rep. 97-417, supra note 10,

at 193 (additional view of Senator Dole) (asserting purpose to

eradicate "racial discrimination which ... still exists in the

American electoral process").

In making that political judgment, Congress necessarily

took into account and rejected as unfounded, or assumed as

outweighed, several risks to fundamental political values that

opponents of the amendment urged in committee deliberations

and floor debate. Among these were the risk that the judicial

remedy might actually be at odds with the judgment of signifi

cant elements in the racial minority; 17 the risk that creating

"safe" black-majority single-member districts would perpetu

ate racial ghettos and racial polarization in voting behavior; 18

the risk that reliance upon the judicial remedy would supplant

the normal, more healthy processes of acquiring political pow

er by registration, voting and coalition building;19 and the

17 See Voting R ights Act: Hearings BefoTe the Subc01nm. on the Constitu

tion of the Senate Comm. on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 542-46 (Feb.

1, 1982) (hereafter Senate Hemings) (prepared statement of Professor Mc

Manus, pointing to disagreements within black community leadership over

relative virtues of local districting plans).

18 See Subcommittee on the Constitution of the Senate Committee on the

Jndiciw71, 97th Cong., 2d Sess., Voting Rights Act, Report on S. 1992, at

42-43 (Comm. Print 1982) (hereafter Subcommittee R epoTt), Teprinted in 8.

Rep. No. 97-417, supm note 10, 107, 149 (asserting "detrimental con

sequence of establishing racial polarity in voting where none existed, or was

merely episodic, and of establishing race as an accepted factor in the decision

making of elected officials"); Subcommittee R eport, snpra, at 45, rep?inted

inS. Rep. No. 97-417, supm note 10, at 150 (asserting that amended Section

2 would aggravate segregated housing patterns by encouraging blacks to

remain in safe black legislative districts).

19 See Subcommittee RepoTt, supm note 18, at 43-44, rep1·inted inS. Rep.

No. 97-417, supra note 10, at 149-60.

JA-20

fundamental risk that the recognition of "group voting rights"

and the imposing of affirmative obligation upon government to

secure those rights by race-conscious electoral mechanisms

was alien to the American political tradition. 20

For courts applying Section 2, the significance of Congress's

general rejection or assumption of these risks as a matter of

political judgment is that they are not among the circum

stances to be considered in determining whether a challenged

electoral mechanism presently "results" in racial vote dilution,

either as a new or perpetuated condition. If it does , the remedy

follows, all risks to these values having been assessed and

accepted by Congress. It is therefore irrelevant for courts

applying amended Section 2 to speculate or to attempt to make

findings as to whether a presently existing condition of racial

vote dilution is likely in due course to be removed by normal

political processes, or by affirmative acts of the affected

government, or that some elements of the racial minority

prefer to rely upon those processes rather than having the

judicial remedy invoked.

III

Findings of Fact

A.

The Challenged Districts

The redistricting plans for the North Carolina Senate and

House of Representatives enacted by the General Assembly of

North Carolina in April of 1982 included six multi-member

districts and one single-member district that are the subjects

of the racial vote dilution challenge in this action.

20 See Senate Hearings, supra, note 17, at 1351-54 (Feb. 12, 1982) (pre

pared statement of Professor Blumstein); id. at 509-10 (Jan. 28, 1982) (pre

pared statement of Professor Erler), reprinted in S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra

note 10, at 147; id. at 231 (Jan. 27, 1982) (testimony of Professor Berns),

rep1"inted inS. Rep. No. 97-417, supra note 10, at 147.

JA-21

The multi-member districts, each of which continued pre

existing districts and apportionments, are as follows, with

their compositions, and their apportionments of members and

the percentage of their total populations and of their registered

voters that are black:

District

Senate No. 22 (Mecklenburg

and Cabarrus Counties (4

members)

House No. 36 (Mecklenburg

County) (8 members)

House No. 39 (Part of For

syth County) (5 members)

House No. 23 (Durham

County) (3 members)

House No. 21 (Wake County)

(6 members)

House No. 8 (Wilson, Nash

and Edgecombe Counties)

(4 members)

%of Population

that is Black

24.3

26.5

25.1

36.3

21.8

39.5

%of Registered Voters

that is Black

(as of 1014182)

16.8

18.0

20.8

28.6

15.1

29.5

As these districts are constituted, black citizens make up

distinct population and registered-voter minorities in each.

Of these districts, only House District No. 8 is in an area of

the state covered by § 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

At the time of the creation of these multi-member districts,

there were concentrations of black citizens within the bound

aries of each that were sufficient in numbers and contiguity to

constitute effective voting majorities in single-member dis

tricts lying wholly within the boundaries of the multi-member

districts, which single-member districts would satisfy all con

stitutional requirements of population and geographical con

figuration. For example, concentrations of black citizens em-

JA-22

braced within the following single-member districts, as de

picted on exhibits before the court, would meet those criteria:

Multi-Member District

Single-Member District:

location and racial

composition E xhibit

Senate No. 22 Part of Mecklenburg County; Pl. Ex. 9

(Mecklenburg/Cabarrus 70.0% Black

Counties)

House No. 36 (1) Part of Mecklenburg County; Pl. Ex. 4

(Mecklenburg County) 66.1% Black

(2) Part of Mecklenburg County; Pl. Ex. 4

71.2% Black

House No. 39 Part of Forsyth County; 70.0% Pl. E x. 5

(Part of Forsyth County) Black

House No. 23 Part of Durham County; 70.9% Pl. Ex. 6

(Durham County) Black substitute

House No. 21 Part of Wake County; 67.0% Pl. Ex. 7

(Wake County) Black

House No. 8 Parts of Wilson, Edgecombe and Pl. Ex. 8

(Wilson, Edgecombe, Nash Nash Counties; 62.7% Black

Counties)

The single-member district is Senate District No. 2 in the

rural northeastern section of the state. It was formed by ex

tensive realignment of existing districts to encompass an area

which formerly supplied components of two multi-member

Senate districts (No.1 of2 members; No. 6 of2 members). It

consists of the whole of Northampton, Hertford , Gates, Ber

tie, and Chowan Counties, and parts of Washington, Martin,

Halifax and Edgecombe Counties. Black citizens made up

55.1% of the total population of the district, and 46.2% of the

population that is registered to vote. This does not constitute

them an effective voting majority in this district. 21

21 We need not attempt at this point to define the exact population level at

which blacks would constitute an effective (non-diluted) voting majority ,

either generally or in this area. Defendant's expert witness testified that a

general "rule of thumb" for insuring an effective voting majority is 65%. This

(footnote continued on next page)

JA-23

This district is in an area of the state covered by § 5 of the

Voting Rights Act.

At the time of creation of this single-member district, there

was a concentration of black citizens within the boundaries of

this district and those of adjoining Senate District No. 6 that

was sufficient in numbers and in contiguity to constititute an

effective voting majority in a single-member district, which

single-member district would satisfy all constitutional require

ments of population and geographical configuration. For ex

ample, a concentration of black voters embraced within a dis

trict depicted on Plaintiffs Exhibit 10(a) could minimally meet

these criteria, though a still larger concentration might prove

necessary to make the majority a truly effective one, depend

ing upon experience in the new district alignments. In such a

district, black citizens would constitute 60.7% of the total

population and 51.02% of the registered voters (as contrasted

with percentages of 55.1% and 46.2%, respectively, in chal

lenged Senate District 2).

B

Circumstances Relevant To The Claim Of Racial Vote

Dilution: The "Zimmer Factors"

At the time the challenged districting plan was enacted in

1982, the following circumstances affected the plan's effect

(footnote continued from previous page)

is the percentage used as a "benchmark" by the Justice Department in

administering § 5. Plaintiffs' expert witness opined that a 60% population

majority in the area of this district could only be considered a "competitive"

one rather than a "safe" one.

On the uncontradicted evidence adduced we find-and need only find for

present purposes-that the extant 55.1% black population majority does not

constitute an effective voting majority, i.e., does not establish peT se the

absence of racial vote dilution, in this district. See KiTksey v. BoaTd of

Supervisors, 554 F.2d139, 150 (5th Cir. 1977) ("Where ... cohesive black

voting strength is fragmented among districts, .. . the presence of districts

with bare population majorities not only does not necessarily preclude

dilution but . . . may actually enhance the possibility of continued minority

political impotence.").

.JA-24

upon the voting strength of black voters of the state (the

plaintiff class), and particularly those in the areas of the chal

lenged districts.

A History Of Official Discrimination Against Black Citizens

In Voting Matters -

Following the emancipation of blacks from slavery and the

period of post-war Reconstruction, the State of North Carolina

had officially and effectively discriminated against black

citizens in matters touching their exercise of the voting fran

chise for a period of around seventy years, roughly two genera

tions, from ca. 1900 to ca. 1970. The history of black citizens'

attempts since the Reconstruction era to participate effective

ly in the political process and the white majority's resistance to

those efforts is a bitter one, fraught with racial animosities that

linger in diminished but still evident form to the present and

that remain centered upon the voting strength of black citizens

as an identified group.

From 1868 to 1875, black citizens, newly emancipated and

given the legal right to vote, effectively exercised the fran

chise, in coalition with white Republicans, to control the state

legislature. In 1875, the Democratic Party, overwhelmingly

white in composition, regained control of state government

and began deliberate efforts to reduce participation by black

citizens in the political processes. These efforts were not imme

diately and wholly successful and black male citizens continued

to vote and to hold elective office for the remainder of the

nineteenth century.

This continued participation by black males in the political

process was furthered by Fusionists' (Populist and Republican

coalition) assumption of control of the state legislature in 1894.

For a brief season, this resulted in legislation favorable to

black citizens' political participation as well as their economic

advancement.

The Fusionists' legislative program favorable to blacks im

pelled the white-dominated Democratic Party to undertake an

JA-25

overt white supremacy political compaign to destroy the

Fusionist coalition by arousing white fears of Negro rule. This

campaign, characterized by blatant racist appeals by pamphlet

and cartoon, aided by acts of outright intimidation, succeeded

in restoring the Democratic Party to control of the legislature

in 1898. The 1898 legislature then adopted constitutional

amendments specifically designed to disenfranchise black vo

ters by imposing a poll tax and a literacy test for voting with a

grandfather clause for the literacy test whose effect was to

limit the disenfranchising effect to blacks. The amendments

were adopted by the voters of the state, following a compara

ble white supremacy campaign, in 1900. The 1900 official litera

cy test continued to be freely applied for 60 years in a variety of

forms that effectively disenfranchised most blacks. In 1961,

the North Carolina Supreme Court declared unconstitutional

the practice of requiring a registrant to write the North Caroli

na Constitution from dictation, but upheld the practice of

requiring a registrant "of uncertain ability" to read and copy in

writing the state Constitution. Bazemore v . Bertie County

Board of Elections, 254 N.C. 398 (1961). At least until around

1970, the practice of requiring black citizens to read and write

the Constitution in order to vote was continued in some areas of

the state. Not until around 1970 did the State Board of Elec

tions officially direct cessation of the administration of any

form of literacy test.

Other of:fjcial voting mechanisms designed to minimize or

cancel the potential voting strength of black citizens were also

employed by the state during this period. In 1955, an anti

single shot voting law applicable to specified municipalities and

counties was enacted. It was enforced, with the intended effect

of fragmenting a black minority's total vote between two or

more candidates in a multi-seat election and preventing its

concentration on one candidate, until declared unconstitutional

in 1972 inDunstonv. Scott, 336 F. Supp. 206 (E.D.N.C. 1972).

In 1967, a numbered-seat plan for election in multi-member

legislative districts was enacted. Its effect was, as intended, to

prevent single-shot voting in multi-member legislative dis-

JA-26

tricts . It was applied until declared unconstitutional in the

Dunston case, supra, in 1972.

In direct consequence of the poll tax and the literacy test,

black citizens in much larger percentages of their total num

bers than the comparable percentages of white citizens were

either directly denied registration or chilled from making the

attempt from the time of imposition of these devices until their

removal. After their removal as direct barriers to registration,

their chilling effect on two or more generations of black citizens

has persisted to the present as at least one cause of continued

relatively depressed levels of black voter registration. Be

tween 1930 and 1948 the percentage of black citizens who

successfully sought to register under the poll tax and literacy

tests increased from zero to 15%. During this eighteen-year

period that only ended after World War II , no black was

elected to public office in the state. In 1960, twelve years later,

after the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of E duca

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), only 39.1% of the black voting age

population was registered to vote, compared to 92.1% of age

qualified whites. By 1971, following the civil rights movement,

44.4% of age-qualified blacks were registered compared to

60.6% of whites. This general range of statewide disparity

continued into 1980, when 51.3% of age-qualified blacks and

70.1% of whites were registered, and into 1982 when 52.7% of

age-qualified blacks and 66.7% of whites were registered. 22

22 The recent history of white and black voter registration statewide and in

the areas of the challenged districts is shown on the following chart.

Whole State

Mecklenburg

Forsyth

Durham

Wake

Wilson

Percent of Voting Age

Population R egistered to Vote

10/78 10180 10/82

White Black White BlcLck White Black

61.7 43. 7 70.1 51.3 66.7 52.7

71.3 40.8 73.8 48.4 73.0 50.8

65.8 58.7 76.3 67.7 69.4 64.1

63. 0 39.4 70.7 45.8 66.0 52. 9

61. 2 37.5 76. 0 48.9 72.2 49.7

60.9 36.3 66.9 40.9 64.2 48.0

(footnote continued on next page)

JA-27

Under the present Governor's administration an intelligent

and determined effort is being made by the State Board of

Elections to increase the percentages of both white and black

voter registrations, with special emphasis being placed upon

increasing the levels of registration in groups, including

blacks, in which those levels have traditionally been depressed

relative to the total voting age population. This good faith

effort by the currently responsible state agency, directly

reversing official state policies which persisted for more than

seventy years into this century, is demonstrably now produc

ing some of its intended results. If continued on a sustained

basis over a sufficient period, the effort might succeed in

removing the disparity in registration which survives as a

legacy of the long period of direct denial and chilling by the

state of registration by black citizens. But at the present time

the gap has not been closed, and there is of course no guarantee

that the effort will be continued past the end of the present

state administration.

The present condition - which we assess - is that, on a

statewide basis, black voter registration remains depressed

relative to that of the white majority, in part at least because of

the long period of official state denial and chilling of black

(footnote continued from previous page)

Percent of Voting Age

Population Registered to Vote

10/78 10/80 10182

White Black White Black White Black

Edgecombe 63.8 37.9 68.2 50.4 62.7 53.1

Nash 61.2 39.0 72.0 41.2 64.2 43.0

Bertie 75.6 46.0 77.0 54.1 74.6 60.0

Chowan 71.3 44.3 77.4 53.9 74.1 54.0

Gates 80.9 73.5 83.9 77.8 83.6 82.3

Halifax 66.8 40.9 72.0 50.4 67.3 55.3

Hertford 75.6 56.6 81.8 62.5 68.7 58.3

Martin 69.3 49.7 76.9 55.3 71.2 53.3

Northampton 72.4 58.5 77.0 63.9 82.1 73.9

Washington 74.3 62.8 82.2 66.0 75.6 67.4

JA-28

citizens' registration efforts. This statewide depression of

black voter registration levels is generally replicated in the

areas of the challenged districts, and in each is traceable in part

at least to the historical statewide pattern of official dis

crimination here found to have existed.

Effects Of Racial Discrimination In Facilities, Education,

Employment, Housing And Health

In consequence of a long history, only recently alleviated to

some degree, of racial discrimination in public and private

facility uses, education, employment, housing and health care,

black registered voters of the state remain hindered, relative

to the white majority, in their ability to participate effectively

in the political process.

At the start of this century, de jure segregation of the races

in practically all areas of their common life existed in North

Carolina. This condition continued essentially unbroken for

another sixty-odd years, through both World Wars and the

Korean conflict, and through the 1950's. During this period, in

addition to prohibiting inter-racial marriages, state statutes

provided for segregation of the races in fraternal orders and

societies; the seating and waiting rooms of railroads and other

common carriers; cemeteries; prisons, jails and juvenile deten

tion centers; institutions for the blind, deaf and mentally ill;

public and some private toilets; schools and school districts;

orphanages; colleges; and library reading rooms. With the

exception of those laws relating to schools and colleges, most of

these statutes were not repealed until after passage of the

federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, some as late as 1973.

Public schools in North Carolina were officially segregated

by race until 1954 when Brown v. Board of Education was

decided. During the long period of de jure segregation, the

black schools were consistently less well funded and were

qualitatively inferior. Following the Brown decision, the pub

lic schools remained substantially segregated for yet another

fifteen years on a de facto basis, in part at least because of

various practical impediments erected by the state to judicial

JA-29

enforcement of the constitutional right to desegregated public

education recognized in Brown. As late as 1960, only 226 black

students throughout the entire state attended formerly all

white public schools. Until the end of the 1960's, practically all

the state's public schools remained almost all white or almost

all black. Substantial desegregation of the public schools only

began to take place around a decade ago, following the Su

preme Court's decision in Swann v. Mecklenburg County

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). In the interval since,

"white-flight" patterns in some areas of the state have pre

vented or reversed developing patterns or desegregation of

the schools. In consequence, substantial pockets of de facto

segregation of the races in public school education have re

arisen or have continued to exist to this time though without

the great disparities in public funding and other support that

characterized de jure segregation of the schools.

Because significant desegregation of the public schools only

commenced in the early 1970's, most of the black citizens of the

state who were educated in this state and who are over 30 years

of age attended qualitatively inferior racially segregated pub

lic schools for all or most of their primary and secondary

education. The first group of black citizens who have attended

integrated public schools throughout their educational careers

are just now reaching voting age. In at least partial con

sequence of this segregated pattern of public education and the

general inferiority of de jure segregated black schools , black

citizens of the state who are over 25 year of age are substantial

ly more likely than whites to have completed less than 8 years

of education (34.6% of blacks; 22.0% of whites), and are sub

stantially less likely than whites to have had any schooling

beyond high school (17.3% of blacks; 29.3% of whites).

Residential housing patterns in North Carolina, as generally

in states with histories of de jure segregation, have traditional

ly been separated along racial lines. That pattern persists

today in North Carolina generally and in the areas covered by

the challenged districts specifically; in the latter, virtually all

residential neighborhoods are racially identifiable. Statewide, ·

JA-30

black households are twice as likely as white households to be

renting rather than purchasing their residences and are sub

stantially more likely to be living in overcrowded housing,

substandard housing, or housing with inadequate plumbing.

Black citizens of North Carolina have historically suffered

disadvantage relative to white citizens in public and private

employment. Though federal employment discrimination laws

have, since 1964, led to improvement, the effects of past dis

crimination against blacks in employment continue at present

to contribute to their relative disadvantage. On a statewide

basis , generally replicated in the challenged districts in this

action, Blacks generally hold lower paying jobs than do whites,

and consistently suffer higher incidences of unemployment. In

public employment by the state, for example, a higher percen

tage of black employees than of whites is employed at every

salary level below $12,000 per year and a higher percentage of

white employees than black is employed at every level above

$12,000.

At least partially because of this continued disparity in em

ployment opportunities, black citizens are three times as likely

as whites to have incomes below the poverty level (30% to

10% ); the mean income of black citizens is 64.9% that of white

citizens; white families are more than twice as likely as black

families to have incomes over $20, 000; and 25.1% of all black

families, compared to 7.3% of white families, have no private

vehicle available for transportation.

In matters of general health, black citizens of North Carolina

are, on available primary indicators, as a group less physically

healthy than are white citizens as a group. On a statewide

basis, the infant mortality rate (the standard health measure

used by sociologists) is approximately twice as high for non

whites (predominately blacks) as for whites. This statewide

figure is generally replicated in Mecklenburg, Forsyth,

Durham, Wake, Wilson, Edgecombe and Nash Counties (all

included within the challenged multi-member districts).

Again, on a statewide basis, the death rate is higher for black

JA-31

citizens than for white, and the life-expectancy of black citizens

is shorter than is that of whites.

On all the socio-economic factors treated in the above find

ings, the status of black citizens as a group is lower than is that

of white citizens as a group. This is true statewide, and it is true

with respect to every county in each of the districts under

challenge in this action. This lower socioeconomic status gives

rise to special group interests centered upon those factors. At

the same time, it operates to hinder the group's ability to

participate effectively in the political process and to elect rep

resentatives of its choice as a means of seeking government's

awareness of and attention to those interests. 23

Other Voting Procedures That Lessen The Opportunity Of

Black Voters To Elect Candidates Of Their Choice

In addition to the numbered seat requirement and the anti

single shot provisions of state law that were declared unconsti

tutional in 1972, see supra p. 28, North Carolina has, since

1915, had a majority vote requirement which applies to all

primary elections, but not to general elections. N.C.G.S.

§ 163-111.24

The general effect of a majority vote requirement is to make

it less likely that the candidates of any identifiable voting

23 Section 2 claimants are not required to demonstrate by direct evidence a

causal nexus between their relatively depressed socio-economic status and a

lessening of their opportunity to participate effectively in the political

process. See S. Rep. No. 97-417, supra note 10, at 29 n.114. Under

incorporated White v. Regester jurisprudence, "[i]nequality of access is an

inference which flows from the existence of economic and educational

inequalities." Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d139, 145 (5th Cir.),

cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 (1977). Independently of any such general

presumption incorporated in amended Section 2, we would readily draw the

inference from the evidence in this case.

2~ There is no suggestion that when originally enacted in 1915, its purpose

was racially discriminatory. That point is irrelevant in assessing its present

effect, as a continued mechanism, in the totality of circumstances bearing

upon plaintiffs' dilution claim. See Part II, supra.

.JA-32

minority will finally win elections, given the necessity that

they achieve a majority of votes, if not in a first election, then

(if called for) in a run-off election. This generally adverse effect

on any cohesive voting minority is, of course, enhanced for

racial minority groups if, as we find to be the fact in this case,

see infm pp. 48-58, racial polarization in voting patterns also

exists.

While no black candidate for election to the North Carolina

General Assembly-either in the challenged districts or

elsewhere-has so far lost (or failed to win) an election solely

because of the majority vote requirement, the requirement

nevertheless exists as a continuing practical impediment to the

opportunity of black voting minorities in the challenged dis

tricts to elect candidates of their choice.

The North Carolina majority vote requirement manifestly

operates with the genE?ral effect noted upon all candidates in

primary elections. Since 1950, eighteen candidates for the

General Assembly who led first primaries with less than a

majority of votes have lost run-off elections, as have twelve

candidates for other statewide offices, including a black cancli

date for Lt. Governor and a black candidate for Congress. The

requirement therefore necessarily operates as a general, ongo

ing impediment to any cohesive voting minority's opportunity

to elect candidates of its choice in any contested primary, and

particularly to any racial minority in a racially-polarized vote

setting. 25

North Carolina does not have a subdistrict residency

requirement for members of the Senate and House elected

from multi-member districts, a requirement which could to

some degree off-set the disadvantage of any voting minority in

multi-member districts. 26

25 See White v. Regester, 412 U. S. 775, 766 (1973).

26 See icl. at 766 n.10.

JA-33

Use Of Racial Appeals In Political Campaigns

From the Reconstruction era to the present time, appeals to

racial prejudice against black citizens have been effectively

used by persons, either candidates or their supporters, as a

means of influencing voters in North Carolina political cam

paigns. The appeals have been overt and blatant at some times,

more subtle and furtive at others. They have tended to be most

overt and blatant in those periods when blacks were openly

asserting political and civil rights- during the Reconstruction

Fusion era and during the era of the major civil rights move

ment in the 1950's and 1960's. During the period from ca. 1900

to ca. 1948 when black citizens of the state were generally

quiescent under de jure segregation, and when there were few

black voters and no black elected officials, racial appeals in

political campaigning were simply not relevant and according

ly were not used. With the early stirrings of what became the

civil rights movement following World War II, overt racial·

appeals reappeared in the campaign of some North Carolina

candidates. Though by and large less gross and virulent than

were those of the outright white supremacy campaigns of 50

years earlier, these renewed racial appeals picked up on the

same obvious themes of that earlier time: black domination or

influence over "moderate" or "liberal" white candidates and

the threat of "negro rule" or "black power" by blacks "bloc

voting" for black candidates or black-"dominated" candidates.

In recent years, as the civil rights movement, culminating in

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, completed the eradication of de

jure segregation, and as overt expressions of racist attitudes

became less socially acceptable, these appeals have become

more subtle in form and furtive in their dissemination, but they

persist to this time.

The record in this case is replete with specific examples of

this general pattern of racial appeals in political campaigns. In

addition to the crude cartoons and pamphlets of the outright

white supremacy campaigning of the 1890's which featured

white political opponents in the company of black political

leaders, later examples include various campaign materials,

.JA-34

unmistakably appealing to the same racial fears and pre

judices, that were disseminated during some of the most hotly

contested statewide campaigns of the state's recent history:

the 1950 campaign for the United States Senate; the 1954

campaign for the United States Senate; the 1960 campaign for

Governor; the 1968 campaign for Governor; the 1968 Presiden

tial campaign in North Carolina; the 1972 campaign for the

United States Senate; and most recently, in the imminent 1984

campaign for the United States Senate.

Numerous other examples of assertedly more subtle forms

of "telegraphed" racial appeals in a great number of local and

statewide elections, abound in the record. Laying aside the

more attenuated forms of arguably racial allusions in some of

these , we find that racial appeals in North Carolina political

campaigns have for the past thirty years been widespread and

persistent.

The contents of these materials reveal an unmistakable in