Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief of Legal Services of North Carolina

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief of Legal Services of North Carolina, 1985. 5203575e-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b23a7f55-6e06-4834-9060-e8dbc6669e66/motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae-and-brief-of-legal-services-of-north-carolina. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

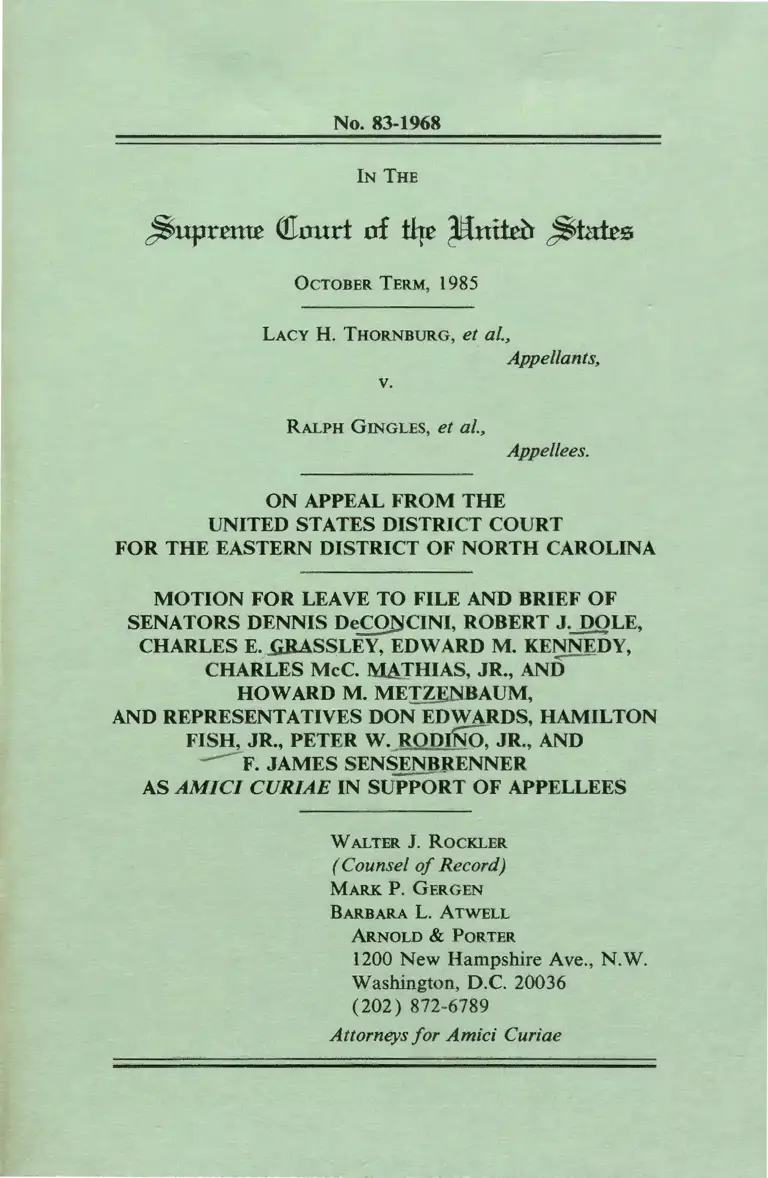

No. 83-1968

IN THE

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

LACY H. THORNBURG, et a/.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF OF

SENATORS DENNIS DeCQNCINI, ROBERT JJ1QLE,

CHARLES E . ..GRASSLEY, EDWARD M. KENNEDY, - . .,---

CHARLES McC. MAJHIAS, JR., AND

HOWARD M. ME~:NBAUM,

AND REPRESENTATIVES DON EDWARDS, HAMILTON ---FISH, JR., PETER W. RODINO, JR., AND

_.-F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER -AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

WALTER J. ROCKLER

(Counsel of Record)

MARK P. GERGEN

BARBARA L. ATWELL

ARNOLD & PORTER

1200 New Hampshire Ave., N .W.

Washington, D .C. 20036

(202) 872-6789

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

No. 83-1968

IN THE

OcTOBER TERM, 1985

LACY H. THORNBURG, et a/.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et al .•

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROUNA

MOTION OF SENATORS DENNIS DeCONCINI,

ROBERT J. DOLE, CHARLES E. GRASSLEY,

EDWARD M. KENNEDY, CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR.,

AND HOWARD M. METZENBAUM, AND

REPRESENTATIVES DON EDWARDS, HAMILTON

FISH, JR., PETER W. RODINO, JR., AND

F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER

FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF ON

BEHALF OF APPELLEES

Amici Curiae are members of the United States Congress

who were principal co-sponsors and supporters of amended

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (1982) .

Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 36.3, amici respectfully

request leave. to file the accompanying amicus brief.*

• Appellees have consented to amici's participation in this case. Appel

lants, however, have denied consent.

As members of the United States Senate and House of

Representatives and the respective Judiciary Committees of the

Senate and House, and as key co-sponsors of amended Section

2, amici are vitally interested in ensuring that the Voting Rights

Act is properly interpreted. The position taken by the Solicitor

General and appellants in this case is inconsistent with the

literal provisions of Section 2. Moreover, it discounts the

importance of the Senate Report, the key source of legislative

history in this case. We are concerned both with preserving the

integrity of Congressional Committee Reports and ensuring

that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is preserved as an

effective mechanism to ensure that people of all races will be

accorded an equal opportunity to participate in the political

processes of this country and to elect representatives of their

choice.

The accompanying brief undertakes a detailed review of

the language and legislative history of amended Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, issues that the parties will not address in the

same detail. Thus, amici believe that the perspective they bring

to the issues in this case will materially aid the Court in

reaching its decision.

Members of the House of Representatives and Senate have

participated as amici curiae in numerous cases before this Court

involving issues affecting the legislative branch, both by motion,

e.g., United States v. Helstoski, 442 U.S. 477 ( 1979), and

consent, e.g., National Organization for Women v. Idaho, 455

u.s. 918 (1982).

For the foregoing reasons, amici respectfully request leave

to file the accompanying amicus brief.

Dated: August 30, 1985

Respectfully submitted,

WALTER J. RocKLER

(Counsel of Record)

MARK P. GERGEN

BARBARA L. ATWELL

ARNOLD & PORTER

1200 New Hampshire Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Telephone: ( 202) 872-6789

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

No. 83-1968

IN THE

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

LACY H. THORNBURG, et a/.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et a/.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF SENATORS DENNIS DeCONCINI, ROBERT J.

DOLE, CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, EDWARD M. KEN

NEDY, CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., AND HOWARD

M. METZENBAUM, AND REPRESENTATIVES DON ED

WARDS, HAMILTON FISH, JR., PETER W. RODINO,

JR., AND F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER AS AMICI

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF INTEREST ........................................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................... 2

ARGUMENT.................................................................... 5

I. TO ASSUME COMPLIANCE WITH SEC

TION 2 UPON EVIDENCE OF SOME ELEC

TORAL SUCCESS BY MEMBERS OF A MI

NORITY GROUP VIOLATES THE LITERAL

REQUIREMENTS OF THAT PROVISION;

EVIDENCE OF SOME ELECTORAL SUC

CESS MUST BE VIEWED AS PART OF THE

"TOTALITY OF CIRCUMSTANCES" TO BE

CONSIDERED············· · ··································~··· 5

II. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE 1982

AMENDMENTS AND THE PRE-BOLDEN

CASE LAW CONCLUSIVELY DEMON

STRATE THAT A VIOLATION OF SECTION

2 MAY BE FOUND ALTHOUGH MEMBERS

OF A MINORITY GROUP HAVE EX

PERIENCED LIMITED ELECTORAL SUC-

CESS ......................................................... ~............ 8

A. The Legislative History: The Majority

Statement in the Senate Report Specifi

cally Provides that Some Minority Group

Electoral Success Does Not Preclude a

Section 2 Claim if Other Circumstances

Evidence a Lack of Equal Access ................ 8

B. The Majority Statement in the Senate Re

port Is an Accurate Statement of the Intent

of Congress with Regard to the 1982

Amendments....... ......................................... 14

1. The Majority Statement in the Sen

ate Report Plainly Reflects the Intent

and Effect of the Legislation .............. 15

2. As a Matter of Law, the Majority

Statement in the Senate Report Is

Entitled to Great Respect................... 20

III. THE DISTRICT COURT APPROPRIATELY

LOOKED TO THE TOTALITY OF CIRCUM

STANCES INCLUDING THE EVIDENCE OF

SOME BLACK ELECTORAL SUCCESS TO

DETERMINE WHETHER BLACKS HAD

EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO PARTICIPATE

IN THE ELECTORAL SYSTEM; THE

COURT DID NOT REQUIRE PROPOR

TIONAL REPRESENTATION........................... 23

CONCLUSION................................................................. 30

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Beer v. United States, 374 F. Supp. 363 (D.D .C.

1974), rev'd on other grounds, 425 U.S. 130 ( 1976)

Chandlerv. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 ( 1976) .. ........... .

City Council of Chicago v.- Ketchum, 105 S. Ct. 2673

( 1985) ....................................................................... .

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 ( 1980) ............. .

Garcia v. United States, __ U.S._, 105 S. Ct.

479 ( 1984) ................................................................ .

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C.

1984) .....................•....................................................

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704 ( W.D. Tex.

1972) ......................................................................... .

Graves v. Barnes, 378 F. Supp. 641 (W.D. Tex.

1974) ......................................................................... .

Grove City College v. Bell, __ U.S._, 104 S. Ct.

1211 ( 1984) .............................................................. .

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139 (5th

Cir. ) , cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 ( 1977) .................. .

Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 ( 1980), quoting TVA

v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 ( 1978) .............. ....................... .

McCain v. Lybrand, No. 74-281 (D.S.C. April 17,

1980) ··········································································

McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037 (11th

Cir. 1984) .................................................................. .

Monterey Coal v. Federal Mine Safety & Health

Review Commission, 743 F.2d 589 (7th Cir. 1984) .

National Association of Greeting Card Publishers v.

United States Postal Service, 462 U.S. 810 ( 1983) ..

National Organization for Women v. Idaho, 455 U.S.

918(1982) ................................................................ .

North Haven Bd. of Education v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512

( 1982) ········································································

Sperling v. United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3d Cir.

1975), cert. denied, 462 U.S. 919 ( 1976) ................ .

United States v. International Union of Automobile

Workers, 352 U.S. 567 ( 1957) ................................. .

13

20,21

14

passim

20

passim

12

13

22

13,23

7

12

20,24,

25,26

21

21

2

22

21

20

lll

Page

United States v. Dallas County Comm'n, 739 F.2d

1529 (11th Cir. 1984) ............................................... 20,25,26

United Statesv. Helstoski, 442 U.S. 477 ( 1979).......... 2

United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 ( 1968) ............ 20

United States v. Marengo County Comm'n, 731 F.2d

1546 (11th Cir. ), cert. denied, __ u.s. _ _ , 105

S. Ct. 375 ( 1984) ....................................................... passim

Velasquez v. City of Abilene, 125 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir.

1984).......................................................................... 7,10,20

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 914 ( 1971) ................... 11

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 ( 1973)....................... passim

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), a.ff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish School

Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 ( 1976)....................... passim

Zuberv. Allen, 396 U.S. 168 ( 1969) ............................ 20

STATUTES

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No.

97-205 ........................................................................ passim

42 u.s. § 1973 ............................................................... 2

MISCELLANEOUS

Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on

the Constitution of the Senate Comm. on the Judi-

ciary, Vol. II, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. ( 1982) ............... 15,16

Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on

the Constitution of the Senate Comm. on the Judi-

ciary, Vol. I, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. ( 1982) ................. 11

Report of the Senate Judiciary Committee on

S. 1992, S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

( 1982) ........................................................................ passim

Report of the House Committee on the Judiciary on

H.R. 3112, H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., lst

Sess. ( 1981) ............. .................................................. 9

128 Cong. Rec. S7139 (daily ed. June 18, 1982) .~·· ·· · ·· 14

128 Cong. Rec. S7091-92 (June 18, 1982) .. ................. 19

128 Cong. Rec. S7095 (daily ed. June 18, 1982) ......... 18

lV

Page

128 Cong. Rec. S7095-96 (June 18, 1982) .................. . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6995 (daily ed. June 17, 1982 ) ........ . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6991, S6993 (daily ed. June 17,

1982) ......................................................................... . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6960-62, S6993 (daily ed. June 17,

1982) ·········································································· 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6941-44, S6967 (daily ed. June 17,

1982) ·········································································· 19

128 Cong. Rec. 6939-40 (daily ed. June 17, 1982 ) ..... . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6930-34 (daily ed. June 17, 1982) .. . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6919-21 (daily ed. June 17, ·1982) .. . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6781 (dailyed. June 15, 1982) ........ . 18

128 Cong. Rec. S6780 (dailyed. June 15, 1982) ........ . 18

128 Cong. Rec. S6646-48 (daily ed. June 10, 1982) .. . 19

128 Cong. Rec. S6553 (daily ed. June 9, 1982) .......... . 17,18

128 Cong. Rec. H3841 (daily ed. June 23, 1982) ....... . 19

128 Cong. Rec. H3840-41 (daily ed. June 23, 1982) .. 17

No. 83-1968

IN THE

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

LACY H. THORNBURG, et a/.,

Appellants,

v.

RALPH GINGLES, et a/.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF SENATORS DENNIS DeCONCINI, ROBERT J.

DOLE, CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, EDWARD M. KEN

NEDY, CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., AND HOWARD

M. METZENBAUM, AND REPRESENTATIVES DON ED

WARDS, HAMILTON FISH, JR., PETER W. RODINO,

JR., AND F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER AS AMICI

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

Senators Dennis DeConcini, Robert J. Dole, Charles E.

Grassley, Edward M. Kennedy, Charles McC. Mathias, Jr., and

Howard M. Metzenbaum, and Representatives Don Edwards,

Hamilton Fish, Jr., Peter W. Rodino, Jr., and F. James

Sensenbrenner hereby appear as amici curiae pursuant to the

motion filed herewith.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

This case presents an important issue of interpreting the

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-205, as

2

they pertain to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973. As members ofthe United States House of Representa

tives and Senate, amici are vitally interested in this case, which

could determine whether Section 2 is to be preserved as an

effective mechanism to ensure that people of all races will be

accorded an equal opportunity to participate in the political

processes of this country and in the election of representatives

of their choice. This case also raises an important question of

the weight to be given congressional committee reports by

which the intent underlying a statute is expressed.

Members of the House of Representatives and Senate have

participated as amici curiae in numerous cases before this Court

involving issues affecting the legislative branch, both by motion,

e.g., United States v. Helstoski, 442 U.S. 477 ( 1979), and

consent, e.g., National Organization for Women v. Idaho, 455

u.s. 918 ( 1982).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

As the authors and principal proponents of the 1982

amendments to Section 2, our primary concern in this case is to

ensure that Section 2 is interpreted and applied in a manner

consistent with Congress' intent. The Solicitor General and the

appellants contend that the district court's finding that the

challenged multimember legislative districts violated Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act "cannot be reconciled" with the

evidence of some recent electoral success by black candidates in

those districts. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae 24,

28.

The three-judge district court, using the "totality of circum

stances" analysis made relevant by Section 2, found blacks

were denied an equal opportunity to participate in the political

process in the challenged districts on the basis of a wide variety

of factors. It considered the evidence of electoral success at

length in its opinion, and found such successes to be "too

minimal in total numbers" and of "too recent" vintage to

support a finding that black candidates were not disadvantaged

3

because of their race. Gingles v. Edmisten. 590 F. Supp. 345,

367 (E.D.N.C. 1984). Appellants and the Solicitor General, on

the other hand, ascribing definitive weight to a single factor,

argue that "given the proven electoral success that black

candidates have had under the multimember system," no

violation of Section 2 can be established. Brief for the United

States as Amicus Curiae 28.

The Solicitor General and appellants seemingly ask this

court to rule that evidence of recent, and limited, electoral

success should be preclusive of a Section 2 claim, though

evidence of other factors overwhelmingly may compel a finding

that blacks are denied an equal opportunity to participate in the

political process. This position is contrary to the express terms

of Section 2, which requires a comprehensive and realistic

analysis of voting rights claims, and it could raise an artificial

barrier to legitimate claims of denial of voting rights which in

some ways would pose as significant an impediment to the

enforcement of Section 2 as the specific intent rule of City of

Mobile v. Bolden. 446 U.S. 55 ( 1980 ), rejected by Congress in

1982.

To assume that some electoral success by some members of

a minority group, no matter how limited or incidental such

success may be, conclusively evidences an equal opportunity for

members of that group, confuses the occasional success of black

candidates with the statutory guarantee of an equal opportunity

for black citizens to participate in the political process and to

elect candidates of their choice. Experience, as documented by

the pre-Bolden case law, proves that the systematic denial of

full and equal voting rights to blacks may be accompanied by

the sporadic success of some blacks in primary or general

elections. As the courts have uniformly recognized, the vice of

the denial of equal voting rights to a minority group is not

obviated by such token or incidental successes of its members.

Most importantly, the position advocated by the Solicitor

General and appellants is inconsistent with the literal language

of Section 2, and was expressly rejected by Congress when it

considered the 1982 amendments, as is made clear in the

4

Report of the Senate Judiciary Committee on S. 1992, S. Rep.

No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. ( 1982) (hereinafter the "Senate

Report") . This Report cannot be treated as the view of "one

faction in the controversy," as argued in the amicus brief of the

Solicitor General (Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

8 n.12 ), in the face of clear evidence that the Report accurately

expresses the intent of Congress generally, and importantly of

the authors of the compromise legislation that was reported by

the Senate Judiciary Committee and enacted, essentially un

changed, into law.

If this Court were to discount the importance of the views

expressed in the Senate Report, it would have significance

beyond this particular case. A. majority of the Judiciary

Committee sought to provide, in the Senate Report, a detailed

statement of the purpose and effect of the 1982 amendments.

That statement was relied upon by members of the Senate in

approving the legislation, and by members of the House in

accepting the Senate bill as consistent with the House position.

This Court should not cut the 1982 amendments free from their

legislative history, and adopt an interpretation of that legisla

tion inconsistent with the view of the congressional majority.

To do so would undermine firmly established principles of

interpretation of Acts of Congress, and sow confusion in the

lower courts that are so often called upon to determine the

legislative intent of federal statutes.

The Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982 were in

tended to reinstate fair and effective standards for enforcing the

rights of minority citizens so as to provide full and equal

participation in this nation's political and electoral processes. In

1982, Congress had before it an extensive record showing that

much had been accomplished towards this end since the Voting

Rights Act was adopted in 1965, but that much more remained

to be done. In construing and applying Section 2, the Court

should be mindful of Congress' remedial goal to overcome the

various impediments to political participation by blacks and

other minority groups.

5

ARGUMENT

I. TO ASSUME COMPUANCE WITH SECTION 2

UPON EVIDENCE OF SOME ELECTORAL SUCCESS

BY MEMBERS OF A MINORITY GROUP VIOLATES

THE UTERAL REQUIREMENTS OF THAT PROVI

SION; EVIDENCE OF SOME ELECTORAL SUCCESS

MUST BE VIEWED AS PART OF THE "TOTAUTY

OF CIRCUMSTANCES" TO BE CONSIDERED

The evidence of some electoral success by blacks in the

challenged districts in North Carolina is not dispositive of a

Section 2 claim, as is evident from the plain language of the

statute. 1 Section 2 requires that claims brought thereunder be

analyzed on the basis of the "totality of circumstances" present

1 We make no effort herein to state the facts · at issue in this case in a

complete manner, though we do note the limited nature of black electoral

success as presented in the district court's findings:

House District No. 36 (Mecklenburg County) and Senate District No. 22

(Mecklenburg and Cabarrus Counties ) - Only two black candidates have

won elections in this century. One black won a seat in the eight member

House delegation in 1982 after this litigation was filed (running without white

opposition in the Democratic primary) , and one served in the four-member

Senate delegation from 1975-1980. This limited success is offset by frequent

electoral defeats. In Bouse District 36, seven black candidates have tried and

failed to win seats from 1965-1982, and in Senate District 22 black candidates

failed in bids for seats in 1980 and 1982. Blacks comprise approximately 25

percent of the population in these Districts. 590 F. Supp. at 357, 365.

House District No. 39 (part of Forsyth County)-The first black to serve

as one of the five-member delegation served from 1975-1978. He resigned in

1978 and his appointed successor ran for reelection in 1978 but was defeated;

a black candidate was also defeated in 1980. In 1982, after this litigation was

filed, two blacks were elected to the House. This pattern of election, followed

by defeats, mirrors elections for the Board of County Commissioners, in which

the only black elected was defeated in her first reelection bid in 1980, and for

elections to the Board of Education, in which the first black elected was

defeated in his bids for reelection in 1978 and 1980. Blacks comprise 25.1

percent of the County's population. 590 F. Supp. at 357, 366.

House District No. 23 (Durham County) - Since 1973, one black has

been elected to the three-member delegation. He faced no white opposition

(footnote continues)

6

in the challenged district. The focus is on whether there is equal

access to the process. The extent of past black electoral success

is only one relevant circumstance.

The controlling provision is Section 2( b), which states:

"A violation of subsection (a) is established if, based

on the totality of circumstances, it is shown that the

political processes leading to nomination or election

in the State or political subdivision are not equally

open to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in

that its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the politi

cal process and to elect representatives of their

choice. The extent to which members of a protected

class have been elected to office in the State or

political subdivision is one circumstance which may

be considered: Provided, That nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their. proportion in

the population."

This express statutory provision clarifies that the "extent to

which members of a protected class have been elected to office

in the State or political subdivision is one circumstance which

may be considered . .. . " Obviously, other factors which com

prise the "totality of circumstances" surrounding the political

process must also be considered, as they were by the district

court in finding a violation of Section 2 here. See Section III,

(footnote continued)

in the primary in 1980 or 1982 and no substantial opposition in the general

election either of those years. Blacks constitute 36.3 percent of the population

of the county. 590 F. Supp. at 357, 366, 370-71.

House District No. 21 (Wake County)-The first time in this century a

black candidate successfully ran for the six-member delegation was in 1980.

That same candidate had been defeated in 1978. Blacks comprise 21.8

percent of the population of the county. 590 F. Supp. at 357, 366, 371.

House District No. 8 (Wilson, Edgecomb and Nash Counties) - No

black was ever elected to serve from this four-member district although it is

39.5 percent black in population. 590 F. Supp. at 357, 366, 371.

7

infra. Electoral success is a relevant criterion, but not the sole

or dominant concern, as posited by the Solicitor General.2

As will be shown below, the primary reason Congress

adopted Section 2( b), which originally was offered as a

clarifying amendment by Senator Dole, was to ensure that the

focus of the Section 2 "results" standard would be on whether

there was equal opportunity to participate in the electoral

process.

The statutory language necessarily contemplates that a

Section 2 violation may be proven despite some minority

candidate electoral success. The focus on the "extent" of

minority group electoral success contemplates gradations of

success-from token or incidental victories to electoral domina

tion-and makes clear that a violation of Section 2 may be

proven in cases where some members of the group have been

elected to office, but the group nevertheless has been denied

a full-scale equal opportunity to participate in the political

process.3

Because Section 2 is plain on its face, it should not be

necessary to look further to the legislative history. Maine v.

Thiboutot, 448 U.S. l, 6 n.4 ( 1980) , quoting TVA v. Hill, 437

2 The Solicitor General seems to suggest that black electoral success in

rough proportion to the black proportion of the population should be

preclusive of a Section 2 claim. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

24-25. At most, this argument appears relevant only to House District No. 23

(Durham County), and, in any event, is plainly inconsistent with Congress'

clearly stated intent that Section 2 claims should not depend upon the race of

elected officials. Section 2 seeks to defiect excessive concern with the racial or

ethnic identity of individual officeholders and, instead, to focus attention

where it properly belongs: on the existence of an equal opportunity for

members of the minority group to participate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice.

3 Consistent with this clear statutory mandate, and the legislative history

discussed below, the lower courts which have considered this issue all have

expressly rejected the position espoused by the Solicitor General and appel

lantS. United States v. Marengo County Comm'n, 731 F.2d 1546, 1571-72

(11th Cir. ), cert. denied, __ U.S.___, 105 S. Ct. 375 ( 1984) ("It is

equally clear that the election of one or a small number of minority elected

officials will not compel a finding of no dilution."); Velasquez v. City of

Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017, 1022 (5th Cir. 1984 ).

8

U.S. 153, 184 n.29 ( 1978). Nevertheless, we will examine that

history because it confirms, in the most unequivocal terms, the

intent of Congress that the extent of minority group electoral

success be analyzed as a part of the totality of circumstances

from which to measure the openness of the challenged political

system to minority group participation. Further, that history

provides an important indication of the manner in which such

analysis should be undertaken, and supports the analysis and

conclusions of the court below.

II. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE 1982

AMENDMENTS AND THE PRE-BOLDEN CASE LAW

CONCLUSIVELY DEMONSTRATE THAT A VIOLA

TION OF SECTION 2 MAY BE FOUND ALTHOUGH

MEMBERS OF A MINORITY GROUP HAVE EX

PERIENCED UMITED ELECTORAL SUCCESS

A. The Legislative History: The Majority Statement in

the Senate Report Specifically Provides that Some

Minority Group Electoral Success Does Not · Pre

clude a Section 2 Claim if Other Circumstances

Evidence a Lack of Equal Access

The legislative history of the 1982 amendments shows very

clearly that Congress did not intend that limited electoral

success by a minority would foreclose a Section 2 claim. This

intent is most plainly stated in the Senate Report, but a similar

intent also is evident from the House deliberations, the individ

ual views of members of the Senate Judiciary Committee

appended to the Senate Report, and the floor debates in the

Senate.

The 1982 amendments originated in the House, which

initially determined that the Bolden intent test was unworkable,

and that it was necessary to evaluate voting rights claims

9

brought under Section 2 on the basis of " [a] n aggregate of

objective factors." 4 Report of the House Committee on the

Judiciary on H.R. 3112, H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., lst

Sess. 30 ( 1981) (hereinafter the "House Report"). As would

the Senate, the House rejected the position that any single

factor should be determinative of a Section 2 claim. The House

Report noted that " [a] 11 of these [described] factors need not

be proved to establish a Section 2 violation." /d. at 30. Thus,

while the House bill did not by its terms require the consid

eration of the " totality of circumstances," that plainly was the

intent of the House.

The Senate refined the House bill, and made explicit the

intent that Section 2 claims be addressed on the basis of the

"totality of circumstances." This refinement came about be

cause of a compromise authored by Senator Dole and others,

the import of which will be addressed in detail below. Of

immediate significance, though, is the fact that the Senate

Report explaining this compromise expressly dealt with the

issue of the significance of minority group electoral success to

Section 2 claims. Indeed, the intent of the Committee with

regard to the handling of this factor was expressed more than

once.

The Senate Report includes, as one "typical factor" to

consider in determining whether a violation has been estab

lished under Section 2, "the extent to which members of the

minority group have been elected to public office in the

jurisdiction." Senate Report at 29. Additional important

commentary with regard to this factor is then provided:

"The fact that no members of a minority group have

been elected to office over an extended period of time

4 Relevant factors, drawn from the Court's decision in White v. Regester,

412 U.S. 755 ( 1973 ), and its progeny included "a history of discrimination

affecting the right to vote, racially polarity [sic] voting which impedes the

election opportunities of minority group members, discriminatory elements of

the electoral system such as at-large elections, a majority vote requirement, a

prohibition on single-shot voting, and numbered posts which enhance the

opportunity for discrimination, and discriminatory slating or the failure of

minorities to win party nomination." House Report 30.

10

is probative. However, the election of a few minority

candidates does not 'necessarily foreclose the possi

bility of dilution of the black vote, • in violation of this

section. Zimmer 485 F.2d at 1307. If it did, the

possibility exists that the majority citizens might

evade the section e.g., by manipulating the election of

a 'safe' minority candidate. 'Were we to hold that a

minority candidate's-success at the polls is conclusive

proof of a minority group's access to the political

process, we would merely be inviting attempts to

circumvent the Constitution. . . . Instead we shall

continue to require an independent consideration of

the record.' Ibid." Senate Report at 29 n.115. (Ref

erences are to Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1973 ), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish

School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 ( 1976). )

No clearer statement of the intent of the Committee with regard

to this issue seems possible. ·see Velasquez v. City of Abilene,

725 F.2d 1017, 1022 (5th Cir. 1984) ("In the Senate Report

. . . it was specifically noted that the mere election of a few

minority candidates was not sufficient to bar a finding of voting

dilution under the results test."). s

Further, this analysis, and its reliance on Zimmer v.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d at 1307, is consistent with the express

view of the Committee that" [ t]he ' results' standard is meant to

restore the pre-Mobile legal standards which governed cases

s The Solicitor General suggests that this statement indicates that minor

ity group electoral success will not defeat a Section 2 claim only if it can be

shown that such success was the result of the majority "engineering the

election of a ' safe' minority candidate." Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae 24 n.49. Amici, who were integrally involved in writing the Senate

Report, view this statement as providing an example which illustrates why

some suceess should not be dispositive, not a legal rule defining the only

circumstance where it is not. Of course, there are numerous other reasons why

some electoral success might not evidence an equality of OPPortunity to

participate in the electoral process. For example, as in the instant case, the

ability to single-shot vote in multimember districts may produce some black

officeholders, but at the expense of denying blacks the opportunity to vote for

a full slate of candidates. See 590 F. Supp. at 369.

11

challenging election systems or practices as an illegal dilution of

the minority vote. Specifically, subsection (b) embodies the

test laid down by the Supreme Court in White [ v. Regester, 412

U.S. 755 ( 1973)]." Senate Report at 27. a This reliance on pre

Bolden case law is important, for it was firmly established under

that case law that a voting rights violation could be established

even though members of the plaintiff minority group had

experienced some electoral success within the challenged sys

tem.

The Committee was acutely aware of this precedent. 7

Indeed, in the case set by Congress as the polestar of Section 2

analysis- White v. Regester-a voting rights denial was found

by this Court despite limited black and Hispanic electoral

success in the challenged districts in Dallas and Bexar Counties

in Texas. Senate Report at 22. a

e There can be no doubt that this was the view of a Congressional

majority as well. Thus, in his additional views, Senator Dole remarked that

"the new subsection [2( b)] codifies the legal standard articulated in White v.

Regester, a standard which was first applied by the Supreme Court in

Whitcomb v. Chavis, and which was subsequently applied in some 23 Federal

Courts of Appeals decisions." Senate Report at 194. Senator Grassley, in his

supplemental views, similarly remarked that "the new language of Section 2 is

the test utilized by the Supreme Court in White." /d. at 197.

7 The Senate Report states:

"What has been the judicial track record under ·me 'results test'?

That record received intensive scrutiny during the Committee

hearings. The Committee reviewed not only the Supreme Court

decisions in Whitecomb [sic] and White, but also some 23

reported vote dilution cases in which federal courts of appeals,

prior to 1978, followed White. " Senate Report at 32.

A list and analysis of these 23 cases appears in Voting Rights Act:

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the Senate Comm. of the

Judiciary, Vol. I, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 1216-26 ( 1982) (hereinafter "I Senate

Hearings") (appendix to prepared statement of Frank R. Parker, director,

Voting Rights Project, Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law).

a The Senate Report cites the portion of this Court's opinion in White v.

Regester wherein it was observed that " [ s] ince Reconstruction, only two

black candidates from Dallas County had been elected to the Texas House of

Representatives, and these two were the only blacks ever slated by the Dallas

Committee for Responsible Government, white-dominated slating group."

(footnote continues)

12

The Committee also expressly relied upon the opinion of

the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Zimmer v. McKeithen,

which it described as " [ t] he seminal court of appeals

decision . . . subsequently relied upon in the vast majority of

nearly two dozen reported dilution cases." Senate Report at 23.

In Zimmer, the Circuit Court found inconclusive the fact that

three black candidates had won seats in the challenged at-large

district since the institution of the suit. The Court reasoned that

while the appellee urged that "the attendant success of three

black candidates, dictated a finding that the at-large scheme did

not in fact dilute the black vote . . . . [ W] e cannot endorse the

view that the success of black candidates at the polls necessarily

forecloses the possibility of dilution of the black vote." 485 F .2d

at 1307.

Similarly, the Committee considered with approval a re

cent case involving Edgefield County, South Carolina, where

prior to Bolden a voting rights violation had been found, despite

limited black electoral success, because '' [ b] lack participation

in Edgefield County has been merely tokenism and even this

has been on a very small scale." McCain v. Lybrand, No. 74-

(footnote continued)

412 U.S. at 766-67. The decision of the district coun indicates that the first of

these candidates ran in 1966, and that they were selected by the white

dominated Dallas Committee for Responsible Government without the

participation of the black community. Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704,

726 (W.D. Tex. 1972), a.frd in part and rev'd in part sub nom. White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755 ( 1973).

A similar point was made with respect to Hispanic success in Bexar

County, where " [ o] nly five Mexican-Americans since 1880 have served in the

Texas Legislature from Bexar County. Of these, only two were from the

barrio area." 412 ·u.s. at 768-69. The district coun indicated that four of

these five were elected after 1960. Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. at 732.

The findings in White v. Regester seem unremarkable until it is realized

that in the instant case the same or a lesser showing of black electoral success

in all of the districts here at issue (except House District No. 23 ), is being

relied upon as conclusive evidence that no voting rights violation has

occurred.

13

281 , slip op. at 18 (D.S.C. April 17, 1980), quoted at Senate

Report 26.9

There is absolutely no indication in the legislative history

that any member of either House of Congress thought that

evidence of minority group electoral success should be pre

clusive of a Section 2 claim. The Solicitor General and

appellants recite at some length numerous statements to ·the

effect that Section 2 was not meant to require proportional

representation. This point is made on the face of the statute,

and there is no question that Section 2 does not re.quire that

minority group representation be, at a minimum, equal to the

group's percentage of the population. However, the finding of

a violation of Section 2 in the face of some minority group

electoral success does not depend upon a rule requiring

proportional representation. Rather, as the reasoning of the

court below illustrates, the finding of a violation depends upon

the assessment of the "totality of circumstances" to determine

whether members of the minority group have been denied an

equal opportunity to participate in the political process and to

9 In addition, there are other pre-Bolden decisions of similar import not

specifically addressed in the Senate Report or in the ftoor debates. So, in one

of the 23 appellate decisions studied by the Committee, the Fifth Circuit

Court, rejecting a reapportionment plan ordered by the district court because

it left the chances for black success unlikely, noted its continuing adherence to

the Zimmer rule: "we add the caveat that the election of black candidates

does not automatically mean that black voting strength is not minimized or

canceled out." Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139, 149 n.21 (5th

Cir. ), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 ( 1977 ).

This rule of common sense was respected by the district courts. For

example, in Graves v. Barnes, 378 F. Supp. 641 , 659-61 (W.O. Tex. 1974) ,

the court concluded that the recent election of Hispanics to the Texas House

of Representatives and to the school board did not frustrate a voting rights

claim.

Similarly, a district court refused in Beer v. United States, 374 F. Supp.

363 (D.D.C. 1974), rev'd on other grounds, 425 U.S. 130 ( 1976), to deem the

city of New Orleans to be entided to pre-clearance under Section 5 despite a

showing that four blacks recendy had won elective office in the municipality.

Although the Section 5 retrogression standard differs from the. Section 2

standard, Beer is relevant to the case at hand in that the Court n. ::ognized that

minority candidate success can be attributable to factors other than equal

access to the electoral process by minority group members.

14

elect representatives of their choice. The disproportionality of

minority group representation is, at most, one factor in the

analysis.

B. The Majority Statement in the Senate Report Is an

Accurate Statement of the Intent of Congress with

Regard to the 1982 Amendments

The Solicitor General appears to believe that Congress

intended to adopt in 1982, the rule rejected in Zimmer v.

McKeithen, drawing from certain statements by amicus Senator

Dole and others that Section 2 was not intended to require

proportional representation, an inference that a Section 2 claim

is foreclosed wherever limited electoral success is shown. See

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae 11 -14. 10

In making this argument, the Solicitor General also argues,

as he did in another recent appeal to this Court regarding a

Section 2 claim, City Council of Chicago v. Ketchum, 105 S. Ct.

2673 ( 1985), that the Senate Report is not determinative of the

intent of Congress, and attaches greater significance to the

individual views of amici Senators Dole and Grassley, and

Senator Hatch. 11 Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae,

10 The Solicitor General also cites the Report of the Subcommittee on the

Constitution to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on S. 1992, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. ( 1982) ("Subcommittee Report" ). The.Subcommittee Report does

not reflect, nor does it purport to reflect, the views of the Congressional

majority who favored overturning the Bolden intent test and reinstating a

results test. !d. at 20-52. At the time the Subcommittee Report was written, a

3-2 majority of the Senate Subcommittee supported existing law, a position

squarely rejected by the full Committee and by the Senate as a whole. The

Chairman of the Subcommittee-Senator Orrin Hatch-opposed the Dole

compromise and voted for the bill ultimately enacted only with great

reluctance, continuing to state until the final vote on the bill his view "that

these amendments promise to effect a destructive transformation in the Voting

Rights Act .... " 128 Cong. Rec. S7139 (daily ed. June 18, 1982 ). Of the four

other members of the Subcommittee: Senator Strom Thurmond opposed the

Dole compromise; Senator Charles Grassley supported the compromise, and,

as noted below, expressly acceded to the majority view of the Senate Report;

and Senators Dennis DeConcini and Patrick Leahy objected to the con

clusions of the Subcommittee Report.

11 As noted in the preceding footnote, while Senator Hatch did ultimately

vote for the bill, he opposed the Dole compromise in Committee and voiced

opposition to it on the floor of the Senate.

15

13 n.27. These efforts are misguided on both factual and legal

grounds.

1. The Majority Statement in the Senate Report

Plainly Reflects the Intent and Effect of the

Legislation

To understand the significance of the majority view stated

in the Senate Report, and of the individual views of amici

Senators Dole and Grassley, it is necessary to un<!_erstand the

nature and the genesis of what is aptly termed the Dole

compromise. The purpose of the compromise was to clarify

what standard should be used under the results test to ensure

that the amended Section 2 would not be interpreted by courts

to require proportional representation. The bill originally

adopted by the House-H.R. 3112-attempted to accomplish

this with a disclaimer that " [ t] he fact that members of a

minority group have not been elected in numbers equal to the

group's proportion of the population shall not, in and of itself,

constitute a violation of this section." In addition, the stated

purpose of the House bill was to reinstate the standards of pre

Eo/den case law, which was understood by the House not to

require proportional representation. House Report at 29-30.

The House bill attracted immediate support in the Senate.

Senators Mathias and Kennedy introduced the House bill as

S. 1992, and enlisted the support of approximately two-thirds of

the members of the Senate as co-sponsors. 12 Still, certain

members of the Senate, and, in particular Senator Dole, had

lingering doubts as to whether the language of the House bill

was sufficient to foreclose the interpretation of the Voting

Rights Act as requiring proportional representation. To arne-

12 Initially S. 1992 had 61 co-sponsors, and by the time the Senate

Judiciary Committee passed upon the Dole compromise, this number had

grown to 66. Thus, as Senator Dole himself recognized in Committee

deliberations, "without any change the House bill would have passed."

Executive Session of the Senate Judiciary Committee, May 4, 1982, reported

at Voting Rights Act: Hearings before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the

Senate Comm. on the Judiciary, Vol. II, 97th Cong.,{ 2d Sess. 57 ( 1982)

( hereinafter "II Senate Hearings") .

16

liorate this concern, Senator Dole-in conjunction with Sena

tors Grassley, Kennedy and Mathias, among others 13_

proposed that Section 2 ( b) be added to pick up the standard

enunciated by this Court in White v. Regester. In addition, the

disclaimer included in the House bill was strengthened to state

expressly that "nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal to their

proportion of the population."

As Senator Dole himself was careful to emphasize, the

compromise was consistent with the Section 2 amendments

passed by the House. 14 As Senator Joseph Biden explained in

the Committee debate over the Dole compromise, "What it

does [is], it clarifies what everyone intended to be the situation

from the outset." Executive Session of the Senate Judiciary

Committee, May 4, 1982, reported at II Senate Hearings 68. In

introducing S. 1992 on the floor, Senator Mathias also termed

the Committee actions on Section 2 "clarifying amendment[s]"

which "are consistent with the basic thrust of S. 1992 as

introduced and are helpful in clarifying the basic meaning of

the proposed amendment." 128 Cong. Rec. S6942, S6944

(daily ed. June 17, 1982).15

13 Senator Dole explained that he "along with [amici] Senators DeCon

cini, Grassley, Kennedy, and Metzenbaum and Senator Mathias ... had

worked out a compromise on [Section 2]." Id. at 58.

14 Thus, Senator Dole explained the proposed compromise as follows:

"(T]he compromise retains the results standards of the

Mathias/Kennedy bill. However, we also feel that the legislation

should be strengthened with additional language delineating

what legal standard should apply under the results test and

clarifying that it is not a mandate for proportional representation.

Thus, our compromise adds a new subsection to section 2, which

codified language from the 1973 Supreme Court decision of

White v. Regester." Executive Session of the Senate Judiciary

Committee, May 4, 1982, reported at II Senate Hearings, 60.

See also United States v. Marengo County Comm'n, }31 F. 2d 1546, 1565 n.30

(11th Cir. ), cert. denied, _ _ U.S. __ , 105 S. Ct. 375 ( 1984 ).

1s A similar understanding of the Senate bill was expressed on the floor

of the House by Representative Don Edwards, Chairman of the Subcom

mittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the House Committee on the

Judiciary:

(footnote continues)

17

The authors of the compromise-in particular amici Sena

tors Dole and Grassley-did not perceive it as inconsistent with

the majority view of the proposed legislation. Indeed, in

additional comments to the Senate Report, both amici Senators

Dole and Grassley clearly stated that they thought-the majority

statement to be accurate. Thus, Senator Dole prefaced his

additional views with the comment that " [ t] he Committee

Report is an accurate statement of the intent of S. 1992, as

reported by the Committee." 16 Senate Report at 193. And

Senator Grassley prefaced his views with the cautionary remark

that " I express my views not to take issue with the body of the

Report." Senate Report at 196. So that there could be no doubt

as to his position, he later added that "I concur with the

interpretation of this action in the Committee Report." Senate

Report at 199. Moreover, the individual views expressed by

both these Senators were in complete accord with the majority

statement. 17

(footnote continued)

" Basically, the amendments to H.R. 3112 would . .. clarify the

basic intent of the section 2 amendment adopted previously by

the House.

" These members [the sponsors of the Senate compromise] were

able to maintain the basic integrity and intent of the House

passed bill while at the same time finding language which more

effectively addresses the concern that the results test would lead

to proportional representation in every jurisdiction throughout

the country and which delineates more specifically the legal

standard to be used under section 2." 128 Cong. Rec. H3840-

3841 (daily ed. June 23, 1982 ).

16 As Senator Dole stated in his additional views, his primary purpose in

offering the compromise was to allay fears about proportional representation

and thereby secure the overwhelming bipanisan suppon he thought the bill

deserved. For this reason, his comments primarily were concerned with

stressing the intent of the Committee that the results test and the standard of

White v. Regester should not be construed to require proportional representa

tion. Senate Repon at 193-94. This in no way suggests that he disagreed with

the views expreslied in the majority repon, for that repon also went to great

pains to explain that neither the results test nor the standard of White v.

Regester implied .a guarantee of proponional representation. Senate Repon

at 30-31. A disclaimer to the same effect appears, of course, on the face of the

statute.

17 Senator Dole objected to etfons by opponents to redefine the intent of

the 1982 amendments on the floor of the Senate. See 128 Cong. Rec. S6553

(daily ed. June 9, 1982 ).

18

Both proponents and opponents of S. 1992 recognized in

the floor debates the significance of the majority statement in

the Committee Report as an explanation of the bill's purpose.

So, early on in the debates Senator Kennedy noted that:

"Those provisions, and the interpretation of those

provisions, are spelled out as clearly and, I think, as

well as any committee report that I have seen in a

long time in this body.

"I have spent a good deal of time personally on this

report, and I think it is a superb commentary on

exactly what this legislation is about.

"In short, what this legislative report points out is

who won and who lost on this issue. There should be

no confusion for future generations as to what the

intention of the language was for those who carried

the day." 128 Cong. Rec. S6553 (daily ed. June 9,

1982 ). 18

18 Senator Kennedy reemphasized this point a week later:

"If there is any question about the meaning of the language, we

urge the judges to read the report for its meaning or to listen to

those who were the principal sponsors of the proposal, not to

Senators who fought against the proposal and who have an

entirely different concept of what a Voting Rights Act should be."

128 Cong. Rec. S6780 (daily ed. June 15, 1982).

An admonition which Senator Dole heartily echoed:

"I join the Senator from Massachusetts in the hope that when the

judges look at the legislative history, they will look at those who

supported vigorously and enthusiastically the so-called com

promise."

128 Cong. Rec. S6781 (daily ed. June 15, 1982).

Senator Kennedy later remarked to the same effect:

"Fortunately, I will not have to be exhaustive because the Senate

Judiciary Committee Report, presented by Senator Mathias, was

an excellent exposition of the intended meaning and operation of

the bill."

128 Cong. Rec. S7095 (daily ed. June 18, 1982).

19

Thus, the proponents of the legislation, including Senators

Dole, 19 Grassley,2o DeConcini,21 Mathias,22 and Kennedy,2.3

repeatedly pointed their colleagues to the majority statement of

the Senate Repon for an explanation of the legislation. Con

versely, opponents of t.he compromise,24 or proponents of

panicular amendments,2s looked to the majority statement of

the Senate Repon as a basis for their individual criticisms of the

bill. At no point in the debates did any Senator claim that the

_majority statement of the Senate Repon was inaccurate, or that

it represented the peculiar views of "one faction in the con

troversy."

Respect for the majority statement of the Senate Repon

carried to the floor of the House during the abbreviated debate

on the Senate bill. Thus, amicus Representative F. James

Sensenbrenner explained to his colleagues:

" First, addressing the amendment to section 2, which

incorporates the ' results' test in place of the 'intent'

test set out in the plurality opinion in Mobile against

Bolden, there is an extensive discussion of how this

test is to be applied in the Senate committee repon."

128 Cong. Rec. H3841 (daily ed. June 23, 1982 ).

Again, there is no suggestion by any member of the House that

the majority statement in the Senate Repon was less than an

accurate statement of the intent of Congress with regard to the

bill.

19 128 Con g. Rec. S6960-62, S6993 (daily ed. June 17, 1982).

2o 128 Cong. Rec. S6646-48 (daily ed. June 10, 1982).

21 128 Cong. Rec. S6930-34 (daily ed. June 17, 1982 ).

22 128 Cong. Rec. S6941-44, S6967 (daily ed. June 17, 1982 ).

23 128 Cong. Rec. S6995 (daily ed. June 17, 1982 ); S7095-96 (June 18,

1982).

24 128 Cong. Rec. S6919-21, S6939-40 (daily ed. June 17, 1982); S7091-

92 (June 18, 1982) .

25 128 Cong. Rec. S6991, S6993 (daily ed. June 17, 1982). The

amendment offered by Senator Stevens is particularly noteworthy-it con

cerned the application of the standards of Section 2( b) in pre-clearance

cases-because he largely sought to justify it on the basis of a consistent

statement in the Senate Report.

20

2. As a Matter of Law, the Majority Statement in

the Senate Report Is Entitled to Great Respect

Under fundamental tenets of statutory construction, Com

mittee Reports are accorded the greatest weight as the views of

the Committee and of Congress as a whole.

In the preceding term, this Court reaffirmed the long

established principle that committee reports are the author

itative guide to congressional intent:26

"In surveying legislative history we have repeatedly

stated that the authoritative source for finding the

legislature's intent lies in the Committee reports on

the bill, which ' represent [ ] the considered and

collective understanding of those Congressmen in

volved in drafting and studying proposed legislation.'

Zuber v. Allen, 396 U.S. 168, 186 ( 1969)."

Garcia v. United States, __ U.S._, 105 S. Ct. 479, 483

( 1984 ); accord Chandler v. Roudebush, -425 U.S. 840, 859 n.36

(1976) ; Zuber v. Allen, 396 U.S. 168, 186 (1969) ; United

States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 385 ( 1968 ); United States v.

International Union of Automobile Workers, 352 U.S. 567, 585

( 1957). The Garcia Court also reiterated the principle that

committee reports provide "more authoritative" evidence of

congressional purpose than statements by individual legislators.

Garcia, 105 S. Ct. at 483; United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. at

385; cf United States v. Automobile Workers, 352 U.S. at 585.

In light of these well-established principles, the effort to

undermine the value of the Committee Report as a guide to

legislative intent by citation to statements made during floor

debates is misguided. Committee reports are "more author

itative" than statements by individual legislators, regardless of

26 Consistent with this longstanding principle, the Senate Report has

been the authoritative source of legislative history relied on by courts

interpreting the 1982 Voting Rights Act Amendments. See, e.g., McMillan v.

Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037 ( 11th Cir. 1984 ); United States v. Dallas

County Comm 'n, 739 F.2d 1529 ( 11th Cir. 1984 ); United States v. Marengo

County Comm'n, 731 F.2d 1546 ( llthCir. ), cert. denied, _ U.S._ , 105 S.

Ct. 375 ( 1984); Velasquez v. City of Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1984).

21

the fact that the individual legislator is a sponsor or floor

manager of the bill. See National Association of Greeting Card

Publishers v. United States Postal Service. 462 U.S. 810, 832-33

n.28 ( 1983 ); Chandler v. Roudebush. 425 U.S. at 859 n.36;

Monterey Coal v. Federal Mine Safety & Health Review Com~

· mission. 743 F.2d 589, 596-98 (7th Cir. 1984); Sperling v.

United States. 515 F.2d 465, 480 (3d Cir. 1975), cert. denied.

462 u.s. 919 ( 1976).27

The basis for this rule is quite simple, for to give con

trolling effect to any legislator's remarks in contradiction of a

committee report "would be to run too great a risk of per

mitting one member to override the intent of Congress. . . . "

Monterey Coal v. Fed. Mine Safety & Health Review, 743 F.2d

at 598. The rule also reflects the traditions and practices of

both Houses of Congress, in which members customarily rely

on the report of the committee of jurisdiction to provide an

authoritative explanation of the purpose and intent of legisla

tion before any floor consideration begins. For example, the

Senate Rules forbid the consideration of "any matter or

measure reported by any standing committee . . . unless the

report of that committee upon that matter or measure has been

available to members for at least three calendar days ... prior

to the consideration . . .. " Rule XVII, para. 5, Standing Rules

of the Senate. In this way, each member has the opportunity to

examine not only the text of proposed legislation, but also the

explanation and justification for it, well in advance of any vote

on the bill. By contrast, the vast majority of members may be

completely unaware of the content of a statement made during

27 In National Association of Greeting Card Publishers, the Court ruled

that a statement by the floor managers of a bill, appended to the conference

committee report, lacked "the status of a conference report, or even a report

of a single House available to both Houses." 462 U.S. at 832 n.28. The Court

in Chandler v. Roudebush held a committee report to be "more probative of

congressional intent" than a statement by Senator Williams, the sponsor of

the legislation. 425 U.S. at 859 n.36. In Monterey Coal, the court noted that

the sponsor's statements "are the only mention in the legislative history of the

specific issue before us." Monterey Coal v. Fed. Mine Safety & Health Review,

743 F.2d at 59(i. Nevertheless, because the sponsor's position was not "clearly

supported by the conference committee report," the court declined to give the

sponsor's remarks controlling weight. 743 F.2d at 598.

22

floor debates. It is impossible to determine from the official

record of congressional proceedings whether a given member,

or a majority or any particular number of members, was

present when a certain statement was made. It is even

customary for statements to be delivered orally only in part,

with the balance printed in the Congressional Record "as if

read." Given these facts, well known to amici from their

decades of experience in both Houses, there is little basis for

concluding that any given ·statement made in floor debate

accurately states the intent of any member other than the one

who made it.2B

Furthermore, the "compromise character" of the 1982

amendments does not detract from the validity of the majority

views. Here the proponents of the compromise wording

expressly agreed with the majority views and viewed the

28 The cases cited by the Solicitor General in support of the effort to

amplify the statements of individual senators and disparage the significance of

the Senate ReP?rt, are inapposite.

In North Haven Bd. of Education v. Bell, 456 U.S. 512 ( 1982), the Court

noted that "the statements of one legislator made during debate may not be

controlling," but indicated that statements made by Senator Bayh, a sponsor

of the legislation, were "the only authoritative indications of congressional

intent regarding the scope of§§ 901 and 902" of Title IX, because § § 901 and

902 originated as a floor amendment and no committee report discussed

them. 456 U.S. at 526-27.

The other case cited by the Solicitor General, Grove City College v. Bell,

_ U.S. __, 104 S. Ct. 1211 ( 1984 ), also involved an interpretation of Title

IX. The Court in Grove City again recognized that "statements by individual

legislators should not be given controlling effect," but cited North Haven to

support its position that "Sen. Bayh's remarks are 'an authoritative guide to

the statute's construction.' " 104 S. Ct. at 1219. The Court indicated that Sen.

Bayh's remarks were authoritative only to the extent that they were consistent

with the language of the statute and the legislative history. !d.

Thus, North Haven and Grove City concern the significance of a sponsor's

expressed views in the absence of a relevant statement in a committee report.

Here, in marked contrast, the Solicitor General draws an unwarranted

inference that electoral success might preclude a Section 2 claim from Senator

Dole's expressed desire to avoid a requirement of proportional representation,

and then asserts that inference as superior to an express statement to the

contrary in the Senate Report.

23

compromise wording as merely a clarification of the intent of

Congress. 29 In these circumstances, there is no reason to

conclude that the Committee Report, prepared after adoption

of the compromise, and accepted by all as an accurate ex

planation of it, loses its status as the most authoritative guide to

legislative intent.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT APPROPRIATELY LOOKED

TO THE TOTALITY OF CIRCUMSTANCES IN

CLUDING THE EVIDENCE OF SOME BLACK ELEC

TORAL SUCCESS TO DETERMINE WHETHER

BLACKS HAD EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO PARTICI

PATE IN THE ELECTORAL SYSTEM; THE COURT

DID NOT REQUIRE PROPORTIONAL REPRE

SENTATION

At bottom, the argument of the Solicitor General and

appellants, that limited electoral success by members of a

minority group should be conclusive evidence that the group

enjoys an equal opportunity to participate, rests on the claim

that such a rule is implicit in the disclaimer that Section 2 does

not provide a minority group the right to proportional repre

sentation. All parties agree that Section 2 was not intended by

Congress to provide a right to proportional representation-but

that point has no significance to the immediate issue.

As the pre-Bolden case law discussed previously illustrates,

the trier of fact may find a denial of equal voting opportunity

where, despite evidence of some minority group electoral

success, evidence of other historical, social and political factors

indicates such a denial. See, e.g., White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 ( 1973 ); Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139 (5th

Cir. ), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 ( 1977); Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973 ), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll

Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636. Such a finding in

no way implies or necessitates that Section 2 be applied as a

guarantee of proportional representation. The "dispropor

tionality" of minority group representation is not the gravamen

29 See text and notes accompanying nn.l4-l7, supra.

24

of the Section 2 claim in such a case, though it may be a factor;

rather, it is the confluence of factors which indicates that an

equal opportunity to participate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice has been denied members

of the group. 30

In order to determine whether a violation of Section 2 has

occurred, courts are to consider whether, given the " totality of

circumstances," members of a protected class have been given

ari equal opportunity to participate in the electoral process and

to elect representatives of their choice. In its opinion, the

district court appeared to undertake just the sort of "totality of

circumstances" analysis in the challenged state legislative dis

tricts as is required by Section 2. In fact, the district court,

quoting the Senate Report at 28-29, set forth the nine so-called

"Zimmer" factors which may be relevant in determining wheth

er a Section 2 violation has been established, and proceeded to

analyze those factors. 590 F. Supp. at 354.

The court stated that it found a high degree of racially

polarized or bloc voting, such that in all districts a majority of

the white voters never voted for any black candidate. The

existence of racially polarized voting is a significant factor in

determining whether vote dilution exists, particularly where, as

here, large multimember districts are involved.3 1 See McMillan

30 As the Solicitor General himself points out, " [a) mended Section

2 . .. focuses not on guaranteeing election results, but instead on securing to

every citizen the right to equal 'opportunity . .. to participate in the political

process . . . .'" Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae 14. Congress

could not have been more clear in expressing its intention that election results

alone should not be determinative of a Section 2 claim.

31 We do not suggest that white voters should be forced to vote for

minority candidates. Every voter, regardless of race has the right to vote for

the candidate of his or her choice. If, however, a majority of white voters will

not vote for a black candidate in any circumstance, and large multimember

districts with majority white voting populations are drawn, the minority vote

is likely to be of relatively little consequence. At best, minority voters are

required to "single-shot" their votes to elect any black candidates in the face

of the majority white opposition.

Because of idiosyncrasies that may be present in any particular election,

the court should look at more than one election, as. the district court did, to

assess the pattern of racially polarized voting. Of course, for this reason,

black success in a single election, even with some white support, cannot be

determinative.

25

v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037 (5th Cir. 1984 ); United

States v. Dallas County Commission, 739 F .2d 1529 (lith Cir.

1984 ); United States v. Marengo County Comm 'n, 731 F.2d

1546 (lith Cir. ), cert. denied, __ U.S._, 105 S. Ct. 375

( 1984 ). This brief does not contend that all at-large,

multimember districts should be suspect or subject to challenge

under Section 2. Rather, the district court acknowledged that

"a multimember district does not alone establish that vote ·

dilution has resulted," 590 F. Supp. at 355, but found that large

multimember districts along with severe racial polarization in

voting and other factors combined here to create ·such dilu

tion.32

The district court stated further that it found a history of

official discrimination against blacks in voting matters-in

cluding the use of devices such as a poll tax, a literacy test, and

an anti-single-shot voting law-which had continuing effect to

depress black voter registration. 590 F. Supp. at 359-61.

Although the district court acknowledged that these devices

were no longer employed by the early 1970s, it also recognized

that their existence for over half a century has had a lasting

impact. !d. at 360. The lasting impact of historical dis

crimination on the present-day ability to participate in the

electoral process has also been recognized in other recent cases.

Cf. United States v. Marengo County Comm'n, 731 F .2d at 1567

(" [ P] ast discrimination can severely impair the present-day

ability of minorities to participate on an equal footing in the

political process."); McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d at

1043-44.

The district court decision rests, in part, on the fact that this

history of official discrimination is still relatively close in terms

of time. The court noted that a "good faith" effort is now being

32 The Solicitor General mischaracterizes the district court's position in

suggesting that it improperly defined racially polarized voting to exist where

more than 50 percent of whites and blacks vote for a different candidate. The

district court's finding of racially polarized voting instead was based on

extensive expert testimony which established that a majority of white voters

will not vote for any mirtority candidates. This was the case even when blacks

ran for office unopposed.

26

made by the responsible state agency to remedy the effects of

past discrimination. The court observed:

" ' .. . If continued on a sustained basis over a

sufficient period, the effort might succeed in removing

the disparity in registration which survives as a legacy

of the long period of direct denial and chilling by the

state of registration by black citizens. But at the

present time the gap has not been closed, and there is

of course no guarantee that the effort will be contin

ued past the end of the present state adminis

tration.' " 590 F. Supp. at 361.

The court below also recognized as significant the majority

vote requirement imposed by North Carolina in primaries. Cf.

Zimmer, 485 F.2d at 1305. Because of the historical domina

tion of the Democratic party in local races, this majority vote

requirement in primaries substantially impeded minority voters

from electing candidates of their choice. 590 F. Supp. at 363.

Recent cases which have considered amended Section 2 have

reached similar conclusions. Cf. McMillan v. Escambia County,

supra, 748 F .2d at 1044 ("[A] majority vote is required during

the primary in an area where the Democratic Party is domi

nant. This factor weighs in favor of a finding of dilution.");

United States v. Dallas County Commission, supra, 739 F.2d at

1536 ("[T]he requirement of a majority in the primary plus the

significance of the Democratic primary combined to 'weigh[]

in favor of a finding of dilution .. . .' "); United States v.

Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d at 1570 (A showing of

vote dilution is "enhanced" by a majority vote requirement in

the primary).

The district court found that " [ f] rom the Reconstruction

era to the present time, appeals to racial prejudice against black

citizens have been effectively used by persons, either candidates

or their supporters, as a means of influencing voters in North

Carolina political campaigns." 590 F. Supp. at 364 .

. Moreover, the racial appeals "have tended to be most

overt and blatan~ in t-hose periods when blacks were openly

asserting political and civil rights." !d. The district court

27

concluded that the effect of racial appeals "is presently to lessen

to some degree the opportunity of black citizens to participate

effectively in the political processes and to elect candidates of

their choice." !d. Racial electoral appeals are a relevant factor.

Senate Report at 29. While not present in this case, one must

be sensitive to the possibility of racial electoral appeals. by

minority candidates as well.

And, the district court found that North Carolina had

offered no legitimate policy justification for the form of the

challenged districts. 590 F. Supp. at 373-74. As the court in

Marengo County acknowledged, "the tenuousness of the justifi

cation for a state policy may indicate that the policy is unfair."

731 F.2d at 1571 (citation omitted),

The foregoing findings contained in the district court's

opinion illustrate that in deciding this case the court appropri

ately considered the factors that Congress found relevant in

assessing the "totality of circumstances." Amici also note that

the distric~ court analyzed black electoral success at length, as

the statute contemplates, as "one circumstance to be consid

ered." However, the Court found that in light of the totality of

circumstances this evidence of electoral success was inadequate

to establish that blacks had an equal opportunity to participate