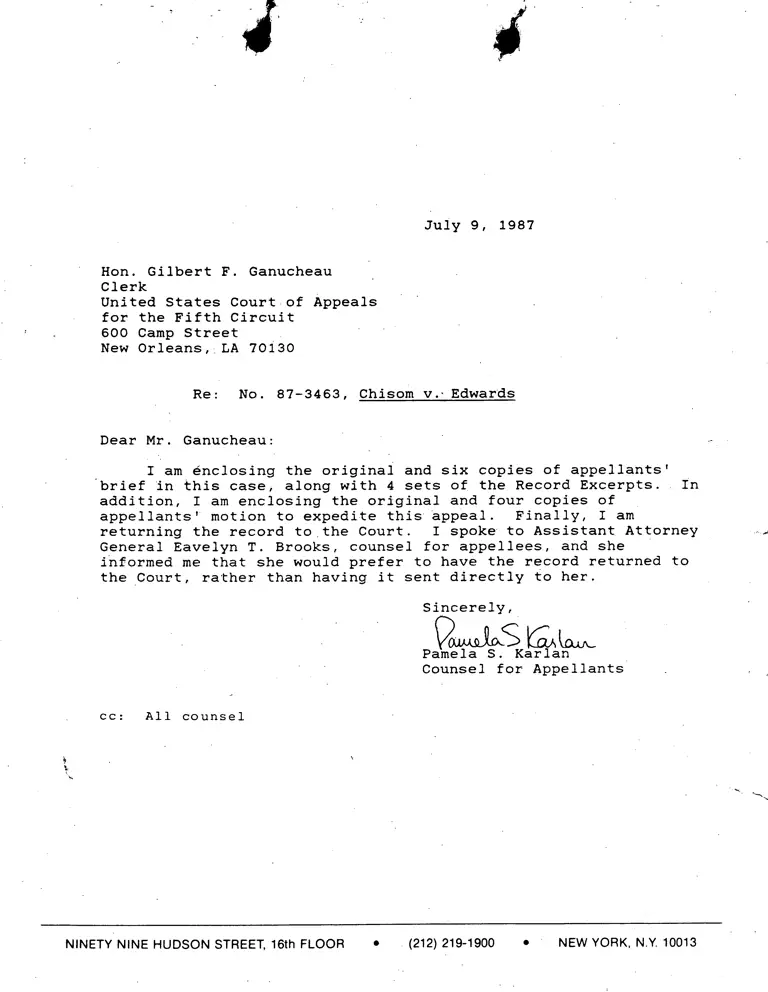

Correspondence from Karlan to Ganucheau (Clerk); Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants Ronald Chisom, et al.; Record Excerpts

Public Court Documents

September 19, 1986 - July 8, 1987

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Correspondence from Karlan to Ganucheau (Clerk); Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants Ronald Chisom, et al.; Record Excerpts, 1986. d44db730-f211-ef11-9f89-0022482f7547. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df3a6f67-d12f-4dd8-9351-58bd93611c98/correspondence-from-karlan-to-ganucheau-clerk-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants-ronald-chisom-et-al-record-excerpts. Accessed December 17, 2025.

Copied!

July 9, 1987

Hon. Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Clerk

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

600 Camp Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Re: No. 87-3463, Chisom v.. Edwards

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

I am enclosing the original and six copies of appellants'

brief in this case, along with 4 sets of the Record Excerpts. In

addition, I am enclosing the original and four copies of

appellants' motion to expedite this appeal. Finally, I am

returning the record to the Court. I spoke to Assistant Attorney

General Eavelyn T. Brooks, counsel for appellees, and she

informed me that she would prefer to have the record returned to

the Court, rather than having it sent directly to her.

Sincerely,

auuloS

Pamela S. Karlan

Counsel for Appellants

cc: All counsel

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR • (212) 219-1900 • NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013

710

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

RONALD CHISOM. et al.

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY

643 Camp Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

C. LANI GUINIER

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

• The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the

following listed persons have an interest in the outcome of this

case. These representations are made in order that Judges of

this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

Plaintiffs: Ronald Chisom

Marie Bookman

Walter Willard

Marc Morial

Louisiana Voter Registration/Education

• Crusade

• Henry A. Dillon, III

Defendants: There are no nongovernmental defendants

Attorneys Julius L. Chambers

for

Plaintiffs: Charles Stephen Ralston

C. Lani Guinier

Pamela S. Karlan

•

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

William P. Quigley

Ron Wilson

Roy Rodney

Attorneys William J. Guste, J.

for

Defendants: Kendall L. Vick

Eavelyn T. Brooks

M. Truman Woodward, Jr.

Blake G. Arata

A. R. Christovich

A 'Noise M. Dennery

Attorney of Record for

Plaintiffs-Appellants

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs-appellants request that this case be set for oral

argument. This appeal involves a legal issue of national

importance, namely, whether the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, covers elections for judicial office, and represents the

first time that a court of appeals has been asked to address this

question.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Certificate of Interested Persons

Statement Regarding Oral Argument iii

Table of Authorities •vi

Statement of Jurisdiction 1

Statement of the Issues Presented 1

Statement of the Case 2

I. Proceedings Below 2

II. Statement of the Facts 3

Summary of Argument 4

Argument 6

I. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act Outlaws

Racial Discrimination in All Elections,

Including Elections for Judicial Positions 6

A. By Its Terms, Section 2 Covers All Elections 6

B. The Relationship of Section 2 to the Fifteenth

Amendment and to Section 5 Shows that Section 2

Should Apply to Judicial Elections 7

1. Section 2 and the Fifteenth Amendment 8

2. Section 2 and Section 5 10

C. The Legislative History of the Voting Rights

Act Shows Congress' Intention to Bar Racial

Discrimination in All Elections, Including

Judicial Elections 12

iv

D. The 1982 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act

Were Intended To Restore the Broad Scope of

Section 2's Protection, and Thus Cannot Justify

Excluding Judicial Elections 15

E. The Unique Nature of the Judicial Function Is

Irrelevant to the Question Whether Section 2

Covers Judicial Elections 18

II. The District Court Erred in Dismissing Appellants'

Constitutional Claims 23

Conclusion 28

Certificate of Service 29

Appendices

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Allen v. State Board of Elections,

393 U.S. 544 (1969)

American Nurses' Ass'n V. State of Illinois,

783 F.2d 716 (7th Cir. 1986)

Pages

12,13

25

Brown v. Dean, 555 F. Supp. 502 (D.R.I. 1982) 20

City of Mobile V. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) 8,24

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) 12

Conley V. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41 (1957) 25

Dillard V. Crenshaw County, 640 F. Supp. 1347

(M.D. Ala. 1986) 9,25

Fortson V. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (1965) 19

Goodloe V. Madison County Board of Election Commis-

sioners', 610 F. Supp. 240 (S.D. Miss. 1985) 21

Haith V. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985)

(three-judge court), aff'd, U.S.

91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986) 11,12,15

Harris v. Graddick, 615 F. Supp. 239

Ala. 1985) 21

Illinois State Board of Elections V. Socialist

Workers Party, 440 U.S. 173 (1979) 20

Kirksey V. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss.

1986) (three-judge court) 10

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D.La.

1983) (three-judge court) 9,21,23

•Martin V. Allain, Civ. Act. No. J84-0708(B)

(S.D. Miss., Apr. 1, 1987) 17,23

Morial V. Judiciary Commission of the State

of Louisiana, 565 F.2d 295 (5th Cir. 1977)

(en banc), cert. denied, 435 U.S. 1013 (1978) • • • • 22

vi

Cases Pages

Nevitt V. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 215-16 (5th Cir.

1978), cert. denied, •446 U.S. 951 (1980) 21

Reynolds V. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) 20,21

Rubin V. O'Koren, 621 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1980) 26

Thornburg V. Gingles, 478 U.S. , 92 L.Ed.2d

25 (1986) 8

Toney v. White, 476 F.2d 203 (5th Cir.), modified

and aff'd, 488 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc) 20

United States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners,

435 U.S. 110 (1978) 13

Voter Information Project v. City. of Baton Rouge,

612 F.2d 208 (1980) passim

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972)

(three-judge court), aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095

(1973) 18,19,20

Statutes, Rules, and Regulations

28 U.S.C. § 1291 1

42 U.S.C. § 1971(e) 13

42 U.S.C. § 1973 7, passim

42 U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1) 7

La. Const. art. V, § 4 3

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-101 (West 1983)

Fed R. Civ. P. 8(a)(2)

Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b)

52 Fed. Reg. 498 (1987)

3

25

26

11

Vii

Legislative History Paaes

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227 (1982) 11, passim

S. Rep. No. 94-295 (1975) 17

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982) 8, passim

Voting Rights: Hearings Before Subcommittee

No. 5 of the House Judiciary Comm., 89th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1965)

Voting Rights Act: Proposed Section 5 Regulations,

Report of the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1986)

13,14

11

128 Cong. Rec. S7095 (daily ed., June 16, 1982) 11

128 Cong. Rec. H3841 (daily ed. June 16, 1982)• 11

Other Authorities

H.R. 6400, § 11(c) 13

Joint Center for Political Studies, Black

Elected Officials: A National Roster, 1980 (1980) 17

Nomination of William Bradford Reynolds to be

Associate Attorney General of the United States:

Hearings Before the Sen. Judiciary Comm.

Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong., 1st Sess.'(1985) 11

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting

Rights Act: Ten Years After (1965) 18

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Unfulfilled Goals (1981) 18

U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census,

Statistical Abstract of the United States 1986

(106th ed. 1985) 18

5 C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure § 1301 (1969) 26

viii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The judgment of the district court dismissing the complaint

was entered on June 8, 1987. Plaintiffs-appellants' notice of

appeal was filed on June 17, 1987. This Court's jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

(1) Did the district court err in holding that judicial

elections are not covered by section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973?

(2) Did plaintiffs sufficiently allege discriminatory

intent?

(3) Did the district court err in imposing a requirement

•that allegations of discriminatory intent be pleaded with

particular specificity in cases raising claims under the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitut,ion?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. Proceeding Below

This action was commenced in September 1986 by five black

individuals registered to vote in Orleans Parish, Louisiana, and

a nonprofit corporation active in the field of voting rights

whose members are black registered voters in Orleans Parish.

Plaintiffs sought to represent a class consisting of all black

registered voters in Orleans Parish.

The complaint alleges that the system under which Justices

of the Louisiana Supreme Court are elected impermissibly dilutes

the voting strength of the black voters of Orleans Parish, in

• violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. Record

Excerpts ("RE") 17-23. Defendants moved to dismiss the complaint

for failure to state either a statutory or a constitutional

claim. On May 1, 1987, the district court (Charles Schwartz,

Jr., J.), issued an opinion holding that section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act does not apply to the election of judges and that

plaintiffs had failed to plead an intent to discriminate with

sufficient specificity to support their constitutional claims.

2

RE 5-16. On June 8, 1987, the district court entered a judgment

dismissing plaintiffs' complaint. RE 4.

II. Statement of the Facts

This case concerns the district court's dismissal of

plaintiffs-appellants' complaint. The following facts were

alleged in the complaint, see RE 17-23, and must therefore be

taken as true.

The Supreme Court of Louisiana consists of seven elected

Justices. Pursuant to La. Const. art. V, § 4, and La. Rev. Stat.

Ann. § 13-101 (West 1983), the Justices are elected from six

judicial districts. Each of the judicial districts elects one

Justice, except for the First Supreme Court District, which

elects two Justices at large. Thus, the First Supreme Court

District, which consists of four parishes--Orleans, St. Bernard,

Plaquemines, and Jefferson--is the only multimember judicial

district.

The total population of the First Supreme Court District is

approximately 1,102,253. Of this total, 379,101 persons (34.4%)

are black. There are 515,103 registered voters in the First

District, of whom 162,810 (31.61%) are black.

• Although the First Supreme Court District contains four

parishes, over half of the district's residents and over half its

registered voters live in Orleans Parish. The majority of

Orleans Parish's residents (55.3%) and of its registered voters

(51.6%) are black.

Louisiana has a long history of purposeful official

3

discrimination on the basis of race, including, in particular,

purposeful discrimination touching upon

black citizens

this pervasive

of Louisiana continue to

official discrimination.

for offices in jurisdictions within the

the right to vote. The

suffer the effects of

In addition, elections

First Supreme Court

District, including elections for judicial office, are

characterized by widespread racial polarization: in races

involving black and white candidates, black voters vote

overwhelmingly for black candidates, while white voters vote

overwhelmingly for white candidates. White voters refuse to

support black candidates. The combination of demographic,

historical, and socio-economic•factors results in black voters in

the First Supreme Court District being unable to participate

equally in the processes leading to the nomination ind election

of Supreme Court Justices and therefore to elect the candidate of

their choice. No black person has ever been elected to the

Louisiana Supreme Court, either from the First Supreme Court

District or from any other district.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

prohibits states from using electoral schemes that result in the

dilution of minority voting power. First, the Voting Rights Act

expressly defines "voting" to encompass "any . . . election" at

which votes are cast for "candidates for public . . office"

and thus, by its terms, applies to judicial elections. Moreover,

4

the structure of the Voting Rights Act and its relationship to

the Fifteenth Amendment show that section 2 reaches judicial

elections. The Supreme Court has already held that section 5 of

the Act, which prohibits states from implementing new electoral

schemes that have the effect of discriminating against minority

voters, applies to judicial elections. Since section 2 and

section 5 were intended to provide complementary tools for

combating electoral discrimination, section 2 should also be

construed to reach judicial elections. This Court has already

held that the Fifteenth Amendment prohibits discrimination in

judicial elections. Since section 2 represents Congress' use of

its enforcement power under the Fifteenth Amendment, section 2

should also prohibit discrimination in judicial elections.

The legislative history of the Voting Rights Act and its

amendments strengthens the conclusion that section 2 should cover

judicial elections. It shows a clear congressional purpose to

eliminate discrimination from every election in which registered

voters participate.

In light of these factors, the district court erred in

holding that the Voting Rights Act does not cover judicial

elections. The linchpin of the district court's analysis is its

observation that judges perform a different function from other

elected officials. With respect to claims under the Voting

Rights Act, that observation is legally irrelevant. Once a state

has made the decision to use an elected judiciary, it cannot

grant the right to choose judges to white citizens while

5

effectively denying that right to black citizens.

The district court also erred in dismissing appellants'

constitutional claims. The heart of the district court's holding

is its misinterpretation of this Court's opinion in Voter

Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208 (1980).

Contrary to the district court's assumption, that case does not

stand for the proposition that the evidence underlying a claim of

discriminatory intent must be pleaded with specificity in the

complaint. Rather, that case, and the complaint in this case,

are fully consonant with the general principles of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure that a complaint contain a short and

plain statement of the claim and that intent need be pleaded only

generally.

ARGUMENT

I. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act Outlaws Racial

Discrimination in All Elections, Including Elections

for Judicial Positions

The fundamental error in the district court's analysis is

that it focuses exclusively on what judges do after they are

elected. Only by virtually ignoring the language, structure, and

• legislative history of the Voting Rights Act was the district

court able to conclude that the nature of the judicial function

renders an electoral system that dilutes the votes of black

citizens immune from attack.

6

A. By its Terms, Section 2 Covers All Elections

Section 2(a) of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, contains

an absolute prohibition of racial discrimination in voting:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any State ... in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color . . . .

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (emphasis added). Section 14(c)(1), which

defines"voting" for purposes of the Act, further shows that this

absolute ban is not restricted to particular types of elections:

The terms "vote" or "voting" shall include all action

necessary to make a vote effective in any primary,

special, or general election, including, but not

limited to, registration, listing pursuant to this

subchapter, or other action prerequisite to voting,

casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted

properly and included in the appropriate totals of

votes cast with respect to candidates for public or

party office and propositions for which votes are

received in an election.

42 U.S.C. .§ 19731(c)(1) (emphasis added). Thus, neither the

substantive nor the definitional sections of the Act provides any

exclusion from the Act's coverage for particular types of

elections.' Aspirants for elective judicial positions are

undeniably "candidates for public ... office," and the process by

which they attain those offices are undeniably "elections."

Thus, section 2 by its terms outlaws schemes for electing judges

that impair the ability of black citizens to participate

'Indeed, the application of the act to candidates for

"party" office further undercuts the district court's contention

that the particular functions performed by judges render

discriminatory election systems immune from attack under section

2.

7

effectively.

B. The Relationship of Section 2 to the

Fifteenth Amendment and to Section 5 Shows

that Section 2 Should Apply to Judicial

Elections

This Court and the Supreme Court have already held that the

Fifteenth Amendment and section 5 of the Voting Rights Act apply

to judicial elections. Because section 2 was intended to enforce

the Fifteenth Amendment and to complement section 5 as a tool for

eradicating discriminatory electoral practices, the decisions in

those earlier cases support the conclusion that section 2 also

applies to judicial elections.

1. Section 2 and the Fifteenth Amendment

Section 2 "protect[s] citizens against the risk that the

right to vote will be denied in violation of the Fifteenth

Amendment." S. Rep. 94-417, p. 40 (1982) ("Senate Report") •2

This Court has already held that suits challenging discrimination

in judicial elections may be maintained under the Fifteenth

Amendment. Voter Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge, 612

F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980). In City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55 (1980), the Supreme Court held that section 2 "simply restated

the prohibitions already contained in the Fifteenth Amendment .

at 61 (plurality opinion); see also Senate Report at

17-19. Thus, prior to the amendment of section 2 in 1982, a

2The Supreme Court has termed the Senate Report an

"authoritative source" concerning Congress' intent in amending

section 2. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. , 92 L.Ed.2d 25, 42

n. 7 (1986).

8

plaintiff clearly could have stated a cause of action under

section i with regard to discriminatory systems for electing

judges. Nothing in the 1982 amendments can be read to remove

judicial elections from the scope of the Voting Rights Act. See

infra pp. 15-17.

Moreover, to reach the conclusion adopted by the district

court would require making the illogical assumption that Congress

used its enforcement power under the second section of the

Fifteenth Amendment to enact a statute that gives minority

citizens less protection than they enjoy under the Amendment

standing alone. Cf. Senate Report at 39-40 (discussing how the

proposed amendments to section 2 represent a legitimate use of

Congress' power to "enact measures going beyond the direct

requirements of the Fifteenth Amendment"). The district court

provided no reason for assuming that section 2's prohibition of

intentional racial vote dilution3 is narrower than the Fifteenth

Amendment's prohibition. If the nature of the judicial function

is irrelevant to the constitutional prohibition of intentional

racial vote dilution, it is equally irrelevant to the statutory

prohibition. Thus, since the Fifteenth Amendment reaches

intentional vote dilution in judicial elections, section 2 also

reaches such discrimination.

3Although section 2 no longer requires a showing of

discriminatory intent, it still prohibits the adoption or

maintenance of intentionally discriminatory systems. See Dillard

v. Crenshaw County, 640 F. Supp. 1347, 1353 (M.D. Ala. 1986);

Ma'or V. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325, 344 (E.D.La. 1983) (three-judge

court); Senate Report at 27.

But if section 2 reaches intentional vote dilution in

judicial elections, then it necessarily also reaches dilution

even when such dilution is merely the result of a particular

system. Congress stated that making the presence or absence of

discriminatory intent a dispositive issue in a section 2 suit

"asks the wrong question." Senate Report at 36. Coverage of

judicial elections simply cannot turn on the intention of the

state officials who enacted or maintain the practices being

challenged. Therefore, section 2 covers all discrimination in

judicial elections.

2. Section 2 and Section 5

The relationship between sections 2 and 5 of the Voting

Rights Act similarly' compels the conclusion that section 2

applies to judicial elections. Sections 4 and 5 of the Act

suspend the use of various devices historically used to

disenfranchise minority voters and require certain jurisdictions

with a history of depressed political participation to seek

federal approval of electoral changes before those changes go

into effect. Congress has made clear that these provisions are

intended to work in tandem with the more generalized prohibitions

of section 2 to form a concerted plan of attack on practices,

standards, and devices that discriminate against minority voters.

Senate Report at 5-6.

It is undisputed that judicial elections are subject to the

preclearance provisions of section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

Kirksem V. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss. 1986) (three-

10

judge court); Haith V. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985)

(three-judge court), aff'd, U.S. , 91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986).

Congress has squarely rejected the proposition that a violation

of section 5 is not necessarily a violation of section 2:

Under the Voting Rights Act, whether a discriminatory

practice or procedure is of recent origin affects only

the mechanism that triggers relief, i.e., litigation

[under section 2] or preclearance [under section 5].

The lawfulness of such a practice should not vary

depending on when it was adopted, i.e., whether it is a

change.

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p. 28 (1982) ("House Report]. 4 Section 5

provides an additional procedural mechanism for protecting voters

in areas with an egregious history of voting discrimination; it

^

does not, however, use an inconsistent standard of review. The

district court's analysis thus essentially creates a Voting

Rights Act "grandfather clause," by permitting Louisiana to

continue using a discriminatory system the Act would not permit

it to enact today.

4Both Congress and the Attorney General• have interpreted the

protections of sections 5 and 2 as coextensive with respect to

the closely related question whether the Attorney General must

object under section 5 to practices that also violate section 2.

See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 12 n. 31 (1982); 128 Cong. Rec.

S7095 (daily ed., June 16, 1982) (remarks of Sen. Kennedy); 128

Cong. Rec. H3841 (daily ed. June 16, 1982) (remarks of Rep.

Sensenbrenner and Rep. Edwards); Voting Rights Act: Proposed

Section 5 Regulations, Report of the Subcomm. on Civil and

Constitutional Rights of the House Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong.,

2d Sess. 5 (1986); Nomination of William Bradford Reynolds to be

Associate Attorney General of the United States: Hearings Before

the Sen. Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 119 (1985); 52

Fed. Reg. 498 (1987) (to be codified at 28 C.F.R. § 51.55(b) (the

Attorney General will withhold § 5 preclearance from changes that

violate § 2); 52 Fed. Reg. 487 (1987) (when facts available at

preclearance proceeding show that the change "will result in a

Section 2 violation, an objection will be entered.")

11

Moreover, the analysis of the three-judge court in Haith

clearly supports applying section 2 as well as section 5 to

judicial elections. Haith expressly relied on the language of

section 2 to support its conclusion that "the Act applies to all

voting without any limitation as to who, or what, is the object

of the vote." Haith V. Martin, 618 F. Supp. at 413 (emphasis in

original). Thus, no basis exists in the structure of the Act

itself for concluding that only section 5 applies to judicial

elections.

C. The Legislative History of the Voting Rights

Act Shows Congress' Intention To Bar Racial

Discrimination in All Elections, Includina

Judicial Elections

In light of the reasons for including judicial elections

within section 2, the decision to exclude them should be made

only on the basis of an explicit congressional intention to do

so. But nothing in the legislative history of the Act suggests

that Congress somehow intended to permit continued racial

discrimination against minority voters as long as that

discrimination involved only judicial elections. To the

contrary, the legislative history confirms the conclusion that

Congress intended that section 2 cover judicial elections.

The Supreme Court has frequently noted Congress' "intention

to give the Act the broadest possible scope," Allen v. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 566-67 (1969). Congress sought

"to counter the perpetuation of 95 years of pervasive voting

discrimination," City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. , 156, 182

12

(1980), and to "create a set of mechanisms for dealing with

continued voting discrimination, not step by step, but

comprehensively and finally," Senate Report at 5.

The Voting Rights Act originated as H.R. 6400, a bill

drafted by the Johnson Administration. The House Judiciary

Committee conducted extensive hearings with respect to that bill.

See Voting Rights: Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the

House Judiciary Comm., 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965) ("House

Hearings"]. At those hearings, Attorney General Katzenbach

testified at length as to the bill's scope. The Supreme Court

has held that, "in light of the extensive role [he] played in

drafting the statute and explaining its operation to Congress,"

Katzenbach's construction of the Act is entitled to great weight.

United States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners, 435 U.S. 110,

131 & n. 20 (1978); see Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. at

566-69; Senate Report at 17 & n. 51.

H.R. 6400 adopted the definition of "voting" employed by the

Civil Rights Act of 1960, see H.R. 6400, § 11(c), reprinted in

House Hearings at 865, which guaranteed the right to cast an

effective ballot "with respect to candidates for public or party

office and propositions for which votes are received in an

election," 42 U.S.C. § 1971(e). In response to questions from

Members of Congress as to the intended scope of H.R. 6400, the

Attorney General made clear that "[e]very election in which

registered electors are permitted to vote would be covered" by

13

the Act. House Hearings at 21 (emphasis added) .5 The clear

5Rep. Kastenmeier noted that one alternative bill had

defined "election" to include

"any general, special, primary election held in any

State or political subdivision thereof solely or

partially for the purpose of electing or selecting a

candidate to public office, and any election held in

any State or political subdivision thereof solely or

partially to decide a proposition or issue of public

law."

The following exchange then occurred:

"Mr. KASTENMEIER. First, I am wondering if you

would accept that definition.

Mr. KATZENBACH. Yes.

Mr. KASTENMEIER. Secondly, I am wondering if you

feel it might aid to put a definition of that sort in

the administration bill or whether it is unnecessary.

Mr. KATZENBACH. I don't think it is necessary.

Congressman, but I cannot think of any objection that I

would have to using that definition or something very

similar to it."

House Hearings at 67 (emphasis added). Katzenbach had a similar

colloquy with Rep. Gilbert:

"Mr. GILBERT. ... You refer in section 3 of the

bill [which dealt with tests and devices] to Federal,

State and local elections. Now, would that include

election for a bond issue?

Mr. KATZENBACH. Yes.

Mr. GILBERT. Now, my bill, H.R. 4427. I have a

definition. I spell out the word 'election' on page 5,

subdivision (b). I say:

"Election" means all elections, including

those for Federal, State, or local office and

including primary elections or any other

voting process at which candidates or

officials are chosen. "Election" shall also

include any election at which a proposition

or issue is to be decided.

Now, I have no pride of authorship but don't you

think we should define in H.R. 6400 [the

Administration's bill] the term 'election'?

Mr. KATZENBACH. I would certainly have no

objection to it and I think it should be broadly

defined.

14

focus of the Act was on the right of all citizens to participate

in the electoral process, rather than on the particular question

to be determined at a given election. As one court has noted,

"the Act applies to all voting without any limitation as to who,

or what, is the object of the vote." Haith v. Martin, 618 F.

Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985) (three-judge court) (emphasis in

original) (holding that section 5 of the Act covers judicial

elections), aff'd, U.S. , 91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986). In light

of Congress' sweeping determination to eliminate the blight of

racial discrimination in voting, it is hard to imagine that

Congress intended, sub silentio, to permit the continued

disenfranchisement of black voters as long as the elections in

which they were barred from participating effectively involved

choosing judges.

D. The 1982 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act

2 Were Intended To Restore the Broad Scope of

Section 2's Protection, and Thus Cannot

Justify Excluding Judicial Elections

In 1982, section 2 was amended to reinstate the "results"

test, and thereby to provide broader protection under the Voting

Rights Act than the Fifteenth Amendment gives. Senate Report at

15. Ultimately, the district court's entire holding rests on the

paradoxical claim that the very act of broadening section 2

constricted its coverage because of the use of one word,

"representatives," in section 2(b). Section 2(b) provides, in

pertinent part, that

House Hearings at 121 (emphasis added).

15

A violation of subsection (a) of this section is

established if, based on the totality of circumstances,

it is shown that the political processes leading to

nomination or election . . . are not equally open to

participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its

members have less opportunity than other members of the

electorate to participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice. The extent

to which members of a protected class have been elected

to office . . . is one circumstance which may be

considered: Provided, That nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in

the population.

Section 2(b) was added to the Act not to restrict the kind

of elections to which the Act applies, but to make clear that the

mere fact that a minority group had not achieved "proportional

representation" (on any particular elected body) would not

constitute a violation of section 2. See Senate Report at 2.

Nothing in the statute or legislative history supports the claim

that section 2(b) •was meant to restrict section 2's protection to

a subset of elections. The choice of the word "representatives,"

as opposed to, for example, the words "candidate" or "elected

official," which are used extensively in the legislative history,

see, e.g., id. at 16, 28, 29, 30, 31, and 67, 6 simply cannot

carry the weight the district court places on it. The only other

district court to have addressed the applicability of section 2

to judicial elections recognized that the word "representative"

was not used in any restrictive sense:

6The House Report uses similar terminology. See, e.g., H.R.

Rep. No. 97-227, p. 4 (1982) ("electoral process"); id. at 18

(condemning practices that deprive minorities of the chance to

elect the "candidate of their choice").

16

There is no legislative history of the Voting Rights

Act or any racial dilution case law which distinguishes

state judicial elections from any other types of

elections. Judges do not "represent" those who elect

them in the same context as legislators represent their

constituents. [However, t]he use of the word

"representatives" in Section 2 is not restricted to

legislative representatives but denotes anyone selected

or chosen by popular election from among a field of

candidates to fill an office, including judges.

Martin v. Allain, Civ. Act. No. J84-0708(B), slip op. at 35-36

(S.D. Miss., Apr. 1, 1987).

In light of the reason why section 2(b) was added, there was

absolutely no reason to believe that it would have had any effect

on the Act's coverage of judicial elections. To the contrary,

Congress' discussion of the increasing presence of minority

elected officials suggests that the ability of minority voters to

elect the judges of their choice was one of the purposes of the

Act. For example, the House Report relied on figures mgarding

the number of black elected officials provided in a report that

explicitly included, as relevant elected officials, elected black

judges. See House Report at 7-9; Joint Center for Political

Studies, Black Elected Officials: A National Roster, 1980, at 4-

5, 14-15 (1980). Of particular salience to this case, the report

on which Congress relied included black elected judges in

Louisiana within its total of black elected officials within the

state. See id. at 123 and 132. 7

7Congress has consistently relied on data concerning black

elected officials that explicitly include judges. In 1975, for

example,. Congress relied for its figures regarding the number of

black elected officials on a report prepared by the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights. See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 94-295, p. 14

(1975). That report explicitly included judges in its summaries

17

E. The Unique Nature of the Judicial Function Is

Irrelevant to the Question Whether Section 2 Covers

Judicial Elections

Rather than relying on the language, structure, and

legislative history of the Act, the district court assumed that

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972) (three-judge

court), aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) (per curiam), had addressed

and rejected the claim that section 2 prohibits discriminatory

judicial elections. It then used Wells' reasoning to explain why

the nonrepresentative nature of the judicial function renders

discriminatory judicial elections immune from attack.

The district court's assumption that Wells concerned the

Voting Rights Act is, quite simply, wrong. First, the complaint

in Wells never mentions the Voting Rights Act. 8 Rather, the

complaint makes clear that the basis of Wells' claim was the

population deviation among Louisiana's Supreme Court Districts,

of the number of black elected officials. See, e.g., U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights Act: Ten Years

After 377 (table containing the number of black elected county

officials in counties with 25% or more black populations, column

listing "Law Enforcement Officials" includes, among others,

"judges" and "justices of the peace").

Similarly, the Civil Rights Commission and the Census Bureau

include elected minority jurists within their descriptions of

black elected officials. See, e.g., U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights,

The Voting Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals 27-28 (1981) (stating

that blacks were rarely elected to "law enforcement positions

(including sheriffs and iudges)") (emphasis added); id. at 31,

34, 35, 37; U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census,

Statistical Abstract of the United States 1986, at 252 (106th ed.

1985).

8A copy. of that complaint appears in Appendix A to this

brief.

18

and the consequent failure to comply with the principle of one-

person, one-vote. 9

The three-judge district court in Wells understood the case

to concern solely whether the Fourteenth Amendment required equal

population apportionment for judicial districts. Its opinion

makes absolutely no mention of either the Fifteenth Amendment or

the Voting Rights Act. That court described its holding in these

terms: "we hold that the concept of one-man, one-vote

apportionment does not apply to the judicial branch of the

government." 347 F. Suppe at 454. Thus, neither the pleadings

nor the opinion in Wells supports the assertion by the court

below that "Wells clearly states section 2 is not applicable to

judicial elections." RE 12.

It is even clearer that the Supreme Court's summary

affirmance in Wells provides no basis for excluding judicial

elections. "The precedential effect of a summary affirmance can

extend no farther than 'the precise issues presented and

9The only statement in the entire complaint which even

mentions racial discrimination is 116(e), which alleges that the

apportionment scheme "lacks uniformity, consistency and

rationalization and, in many instances, operates to minimize or

cancel out the voting strength of racial or political elements in

the election districts." It is clear from the context of the

complaint as a whole that this allegation was not intended to

state a cause of action separate from the plaintiffs'

straightforward malapportionment claim. Cf. Fortson V. Dorsey,

379 U.S. 433, 439 (1965) (although plaintiffs "asserted in one

short paragraph of their brief" that Georgia's system of electing

state senators was used to dilute the electoral strength of black

voters, they "never seriously pressed this point below" and the

district court "did not consider or rule on its merits";

therefore, the Supreme Court addressed only the one-person, one-

vote claim).

19

necessarily decided," and thus "[q]uestions which 'merely lurk

in the record,' are not resolved and no resolution of them may be

inferred." Illinois State Board of Elections v. Socialist

Workers Party, 440 U.S. 173, 182-83 (1979) (internal citations

omitted). The sole issue presented in Wells' jurisdictional

statement was

Does a state constitutional provision which provides

for the election of state Supreme Court Justices by

districts violate the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment when those districts do not

conform to the one-man, one-vote rule?

Juris. Statement at 4, Wells v. Edwards, No. 72-621. 10 Since

neither the opinion of the three-judge court nor the

jurisdictional statement made any mention of the Fifteenth

Amendment, the Voting Rights Act, or, indeed, discrimination on

the basis of race, the Supreme Court's summary affirmance in

Wells simply has no precedential weight on the question whether

section 2 applies to judicial elections.

Nor should the opinion in Wells carry any analytical weight.

The fact that the Constitution does not require strict population

equality among judicial districts says virtually nothing about

whether the Voting Rights Act prohibits judicial apportionment

schemes that result in black voters being denied an equal

opportunity to participate effectively.

First, the protections mandated by Reynolds v. Sims, 377

U.S. 533 (1964), are not identical to those provided by the

10A copy of the jurisdictional statement appears in Appendix

B to this brief.

20

Voting Rights Act. The Voting Rights Act has always been

interpreted as providing protection beyond that afforded by the

principle of one-person, one-vote. For example, the Act reaches

practices wholly unrelated to the effects of apportionment. 11

But even with respect to questions of apportionment, Congress

intended that the Voting Rights Act be interpreted more broadly

than Reynolds, because it knew that "population differences were

not the only way in which a facially neutral districting plan

might unconstitutionally undervalue the votes of some." Senate

Report at 20; cf. Voter Information Project v. City of Baton

Rouge, 612 F.2d at 211 (discussing distinction between one-

person, one-vote theory and claims of racial vote dilution);

Nevitt v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 215-16 (5th Cir. 1978)

(distinguishing between "quantitative" and "qualitative" vote

dilution), cert. denied, 446 U.S. 951 (1980). Thus, for example,

Ma or V. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 349-55 (E.D. La. 1983) (three-

judge court), rejected a congressional districting plan that

fractured New Orleans' large black community into two districts

despite the plan's compliance with the one-person, one-vote

standard. The plan submerged concentrations of black voters

within white majorities, thereby making it impossible for blacks

11See, e.g., Toney v. White, 476 F.2d 203, 207-08 (5th Cir.)

(use of voter purge statute), modified and aff'd, 488 F.2d 310

(5th Cir. 1973) (en banc); Harris v. Graddick, 615 F. Supp. 239

(M.D. Ala. 1985) (appointment of polling officials); Goodloe v.

Madison County Board of Election Commissioners, 610 F. Supp. 240

(S.D. Miss. 1985) (invalidation of absentee ballots); Brown v.

Dean, 555 F. Supp. 502 (D.R.I. 1982) (location of polling

places).

21

to elect the candidates of their choice. This result itself was

prohibited by the Voting Rights Act.

The fact that judges are not supposed to represent directly

the will of a constituency also is irrelevant to the scope of

section 2. The district court's reliance on Morial v. Judiciary

Commission of the State of Louisiana, 565 F.2d 295 (5th dr.

1977) (en banc), cert. denied, 435 U.S. 1013 (1978), is therefore

misplaced. In Morial, this Court held that the duties of judges

and the duties of more political officials differed in ways that

justified placing restrictions on candidates for judicial office

that were not imposed on candidates for other offices. But the

question of how ludges and candidates for judicial office should

conduct themselves differs significantly from the question of

what rights should be accorded to voters given a state's decision

to make judicial positions elective. The Voting Rights Act

focuses on the rights of black voters, not the interests of black

candidates. 12 Neither the scope of )official duties nor the level

of official performance has any bearing on whether black voters

can be denied an equal voice in electing those officials. Both

Houses of Congress have expressly rejected the concept that a

voting rights plaintiff must show unresponsiveness on the part of

elected officials to establish a violation of section 2. See

Senate Report at 29, n. 116 ("Unresponsiveness is not an

essential part of plaintiff's case."); House Report at 30 (same).

12The Morial Court explicitly stated that the challenged

statute had only a negligible impact on the constitutional

interests of voters. See 565 F.2d at 301-02.

22

In light of Congress' decision that responsiveness or its absence

is not the touchstone of a section 2 violation, it makes no sense

to suggest, as the court below did, that section 2 should not

cover judicial elections because a judge is not supposed to

represent the views of the electorate. Ma or V. Treen, 574

F.Supp. at 337-38, implicitly recognized that the interests and

rights of black voters in judicial and nonjudicial elections are

identical when it relied on an analysis of polarized voting which

included, among the 39 elections studied, at least 13 involving

judicial positions.

In deciding to make positions on its Supreme Court elective,

the State of Louisiana has decided that the people shall choose

the justices. Having made this decision, the State lacks the

power to structure its judicial elections in a fashion that

results in black citizens having a lesser opportunity to elect

the judicial candidates of their choice than white citizens

enjoy. See also Martin v. Allain, slip op. at 35-36. 13

13Even though an office need not be representative, in the

sense that a State is not required in the first place to permit

citizens to choose the person who fills it, the Voting Rights Act

prohibits practices that diminish the opportunity of minority

citizens to decide who fills it once the decision has been made

that it should be elective. See Senate Report at 6-7 (abolishing

elective posts may "infringe the right of minority citizens to

vote and to have their vote fully count").

23.

II. The District Court Erred in Dismissing Appellants'

Constitutional Claims

In essence, the district court rested its decision to

dismiss plaintiffs' constitutional claims on two grounds. First,

it believed that the complaint had failed to advance a claim of

intentional discrimination: "plaintiffs intend to prove [their

constitutional] claim on a theory of 'discriminatory effect' and

not on a theory of 'discriminatory intent . . ." RE 16.

Second, it held that, even assuming that the complaint does

advance a claim of intentional discrimination, it failed to do so

with sufficient specificity: "plaintiffs'- complaint does not

allege the system by which the Louisiana Supreme Court Justices

are elected was instituted with specific intent to discriminate.

This contrasts with the specific allegations in Voter Information

Pro ect • • • " RE 16. 14

The district court's first ground for dismissing the

complaint ignores the plain language of the complaint, which

explicitly alleges that:

The defendant's actions are in violation of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution and 42 USC Section 1983 in that the

purpose and effect of their actions is to dilute,

minimize, and cancel the voting strength of the

plaintiffs.

RE 22 (emphasis added). Appellants clearly did not propose to

proceed upon a constitutional "theory of 'discriminatory

14The district court's opinion did give plaintiffs an

opportunity to replead their constitutional allegations to

conform with its reading of Voter Information Project.

24

effect," RE 16, in light of City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55 (1980). Cf. Plaintiffs' Motion in Opposition to Motion to

Dismiss at 12 (discussing the Fifteenth Amendment's intent

requirement) •15

Second, the district court erred in holding that the

complaint's allegation of purpose was insufficient. Its

conclusion fails to give proper weight to the standards

established by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and rests on

a misreading of this Court's decision in Voter Information

Pro ect v. City of Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980).

Rule 8 governs general rules of pleading. It requires that

a pleading setting forth a claim for relief must contain "a short

and plain statement of the claim, " Fed R. Civ. P. 8(a)(2), "that

will give the defendant fair notice of what the claim is and the

grounds upon which it rests." Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 47

(1957). Thus, for example, the Seventh Circuit held, in American

Nurses' Ass'n v. State of Illinois, 783 F.2d 716 (7th Cir. 1986),

that a charge of intentional sexual discrimination, "standing

alone, would be quite enough to state a claim under Title VII."

Id. at 724. Similarly, this Court's decision in Voter

Information Project makes clear that complaints in constitutional

voting rights cases must be construed liberally. 612 F.2d at

15Even in cases involving claims of intentional

discrimination, plaintiffs must plead and prove some level of

discriminatory effect. Cf. Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 640 F.

Supp. 1347 (M.D. Ala. 1986) (section 2 intent case). Thus, that

the complaint pleaded "purpose and effect" cannot be taken as an

indication of an intent to advance an "effects theory" only.

25

210; cf. Rubin V. O'Koren, 621 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1980).

Certainly, the complaint in this case meets the standards of Rule

8: defendants are on notice that plaintiffs intend to prove that

the system of electing Supreme Court Justices from the First

District violates the United States Constitution.

Moreover, Rule 9, which governs pleading of special matters,

further supports appellants' position:

In all averments of fraud or mistake, the circumstances

constituting fraud or mistake shall be stated with

particularity. Malice, intent, knowledge, and other

condition of mind of a person may be averred generally.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b) (emphasis added). The drafters of Rule 9(b)

felt that to require specificity of pleading with regard to

intent would be counterproductive since conditions of the mind

are inherently difficult to describe with exactitude in the short

and plain statement foreseen by Rule 8. 5 C. Wright & A. Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 1301 (1969).

The rationale for Rule 9(b)'s approval of general

allegations of intent is, if anything, stronger in a case

involving group intent. The problem of analyzing intent is

compounded when the intent to be discerned is the product of a

group of individuals acting over a long period of time. In light

of the dual commands of Rules 8(a) and 9(b), the complaint in

this case was clearly sufficient to survive a motion to dismiss.

Read properly, Voter Information Project reaches the same

conclusion. First, that case simply does not stand for the

proposition that complaints in constitutional voting rights cases

require some form of heightened specificity. It is clear from

26

the context of this Court's quotation of several paragraphs of

the Voter Information Project complaint that the reason for that

quotation was not to set a special rule for pleadings; rather, it

was intended to differentiate the claim of constitutional racial

vote dilution raised, by Voter Information Project from a claim of

constitutional one-person, one-vote vote dilution. See 612 F.2d

at 211.

In addition, the allegations on which this Court relied in

Voter Information Project are no more "specific" than the

allegations made in the complaint in this case. Voter

Information Project alleged: (1) that the "sole purpose" of the

existing electoral system was to ensure the preservation of an

all-white judiciary; (2) that the system had been adopted "as a

reaction to increasing black voter registration"; and (3) that

Baton Rouge had a "continuing history of 'bloc voting," 612

F.2d at 211. In this case, the complaint alleges that the

challenged scheme represents: (1) an intention to "dilute,

minimize, and cancel the voting strength of the plaintiffs," who

are black; (2) an official history of racial discrimination; (3)

"widespread prevalence of racially polarized voting"; and (4) the

"lack of any justifiable reason to continue" the current

electoral scheme. RE 6, 5. It is hard to fathom any legally

significant difference between these two sets of allegations

great enough to justify dismissing the complaint.

27

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the district court dismissing appellants'

complaint for failure to state a claim should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY

643 Camp Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

July 8, 1987

•

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

C. LANI GUINIER

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Pamela S. Karlan, hereby certify that on July , 1987,

I served copies of the foregoing brief upon the attorneys listed

below via United States mail, first class, postage prepaid:

Kendall L. Vick, Esq.

Asst. Atty. General

La. Dept. of Justice

234 Loyola Ave., Suite 700

New Orleans, LA 70112-2096

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Blake G. •Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, LA 70170

A. R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Noise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(2„,s Gi1/4

Pamela S. Karlan

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

29

APPENDIX A

••_•

2ivil Action Num]oer

UNITED STATES DIST7ICT COURT

2 0 0

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA, BATON ROUGE DIVISION

I U. LASTR!CT

!

MRS. BETTY 'TELLS

Petitioner 3

! C'riA;LES ki

THE GOVERNOR OF LOUISIANA - THE HONORABLE- EDWIN-EDWV

THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE STATE OF LOUISIANA -

THE HONORABLE 1:7ADE O. MARTIN, JR., THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

OF LOUISIANA - THE HONORABLE WILLIAM GUSTE, THE STATE

CUSTODIAN OF VOTING MACHINES FOR LOUISIANA - THE

HONORABLE DOUGLAS FOWLER, THE DEMOCRATIC STATE

CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF LOUISIANA and THE

REPUBLICAN STATE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF LOUISIANA

Defendants

FILED: DY. CLK.

COMPLAINT

1.

Petitioner herein is Mrs .. Betty a citizeil,and. resident and

:elector of Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. " •

2.

The defendants herein are:

(a) The Governor of Louisiana - The Honorable Edwin

Edwards, whose_office is at the State Capitol,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

(b) The Secretary of State for the State of Louisiana .-

The Honorable Wade 0. Martin, Jr., whose office is

at the State Capitol, Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

(c) The Attorney General of Louisiana - The Honorable

William Guste, whose office is at the State Capitol,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

(d) The State Custodian of Voting Machines for Louisiana -

The Honorable Douglas Fowler, whose office is at the

State Capitol, Baton Rouge, Louisiana;

(e) The Democratic State Central Committee - Its Chairman

is the Honorable Arthur C. Natson, whose office is

located in the City of Natchitoches, Natchitoches

Parish, Louisiana, and;

.•

.17

••••••,-,-

4

• (f) The .epublican State Central Committee - Its Chairman

is the Honorable Charles C. deGravelles, whose office

is located in the City of Lafayette, Lafayette Parish,

Louisiana. _

3.

Jurisdiction:

(a) Jurisdiction here is based on Article 3, Section 2

of the Constitution of the United States and under

the Constitution's Fourteenth Amendment Equal

Protection clause;

(b) Jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under the

provisions of Title 28, United States Code, Section

1331 (this being a civil action in equity arising

under the Constitution and Laws of the United States)

and Title 42, United States Code, Sections 1983 and

1988; petitioner contends that she has been, is now

being, and will continue to be denied rights, privi-

leges, and immunities secured to her, and others

similarly situated, by the Constitution of the United

States and that she is being denied the full and equal

benefit of pertinent laws. As a consequence, she has

been, is now being and will continue to be, deprived

of her civil rights as a citizen of Louisiana and of

the United States in violation of the Constitution

and Laws of the United States;

(c) . Jurisdiction of this Court-is further invoked undei•

the provisions of Title 23, United States Code, Section

1343 (3) .; this being an action by petitioner for the

redress of the aforesaid deprivation, under color of

law, of her rights, privileges and immunities and the

equal protection of the laws, secured to her as a

citizen of the United States by the Constitution and

laws of the United States;

(d) Jurisdiction of this Court is additionally invoked

under the provisions of 23 United States Code 2201

and 2202 for a Declaratory Judgment decreeing the

rights of plaintiff herein in that the present laws

apportioning the Louisiana Supreme Court are uncon-

stitutional upon their face, or, alternatively, are

unconstitutional because of the manner in which they

have been, are being, or will be administered; and

(e) Complainant further proceeds herein pursuant to Title

28, United States Code, Sections 2201 and 2202, for

a Declaratory Judgment to determine and define the

legal rights, status and relations of plaintiff, and

those similarly situated, in the subject matter of

this controversy, and for a final adjudication of all

matters in actual controversy between the parties to

this cause.

-Article 7, section 9 of the Constitution of the State of Louisiana,

adopted June 13, 1921, established the composition of the Supreme

Court of Louisiana, designated Supreme Court districts numbering

six (6) together with the number of justices to be elected from

. each district. That constitutional provision is presently in

effect and is, by reference, incorporated herein and made part

hereof.

5.

;Article 7, section 9 of the Louisiana Constitution, adopted in 1921

referred to in the preceding article which is presently in effect '

is arbitrary, capricious, discriminatory -and unreasonable; it does:

not respond to the "one man, one vote" principle and contains multi-

ple infirmities, defects and irregularities which are not constitu-

tionally permissible.

s.

'Article 7, section 9 of the Louisiana Constitution, adOcted in 1921

[should be declared unconstitutional, illegal, null andlvoid for the

11following, among other, reasons:

(a) The article and section contains copulation deviations

by districts which are not justified on any legal basis

and which do not occur as the result of a rational state.

policy;

(b) Thevarious.district created by Article.7,.section 9,i-

of the Louisiana Constitution, adopted June 18, 1921,

have not been changed or redistricted since their

creation in 1921 nor has there been any effort to

reapportion said districts in accord with population

changes, or designate proper representation from each;

(c) The population deviation, reflected by the U. S. Census,

1970, State of Louisiana, shows a variance of represen-

tation on th? Lui5iarla Sunreme Court of 312,582 as.

between District 1,4 (369,490) and District (532,072)

and further variances between the remaining districts;

(d) The composition of District 1 of the Louisiana Sunreme

Court effectively and practically eliminates: represen-

tation on the Louisiana Supreme Court for the Parishes

of Jefferson, St. 3ernard and Plaguemines since said

parishes are lumped with Orleans Parish and said Orleans

Parish has a greater population than all other parishes

in said district combined.

(e) The constitutional provision referred to in Article 4

lacks uniformity, consistency and rationalization and,

in manyinstances, operates to minimize or cancel out

the voting strength of racial or political elements

in the election districts.

. , .

7.

,Petitioner alleges that she is an adult citizen of the United States

and of the State of Louisiana and is a duly qualified and registered

voter for the State of Louisiana; she appears herein individually

and as a qualified voter of this State in her own behalf and on

behalf of all qualified voters of Louisiana Who are similar%rsitu-

ated and who also are aggrieved by the malapportionment, present

and contemplated, of the Louisiana Constitution Article 7, section

9; more specifically, petitioner alleges that her right to vote for

Louisiana Supreme Court justices and her representation through and

by her Supreme Court justices is constitutionally impaired because

. the weight and force of her vote is, in a substantial fashion,

diluted when compared with the weight and force of the votes of

:.citizens living in other parts of the State.

8.

P Petitioner further alleges that there are no distinctive, special ,

or justifiable circumstances or sanctions of law bearing a reasonabl

relation to the pretended object - equality of representation - of'

!ithe constitutional provisions described in Article 4 and that

ikliscriminations and lack of uniformity result therefrom. Defendants

rare charged, under the laws of Louisiana, with the obligation of :

rcalling and conducting primary, special and general elections for i

'Ptblic officials, including members of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

!Defendants, acting under color of law and with full knowledge of

lithe facts and circumstances as herein related, have been, are, and!

will continue to act pursuant to the laws referred to in Article

4tereinabove in such a manner as will continue and perpetuate the

,LAiscrirdinations against petitioner and those:Similarly sittiated7.

r,if defendants act and are permitted to act under the authority of. t:

and in the implementation of the said laws, their official acts, ,

deeds and omissions will result in arbitrary, capricious, unreason-

able and discriminatory state action which violates the voting

rights, powers and privileges of petitioner and those similarly

situated; such will completely and effectively deny to petitioner

and others the full and equal benefit of pertinent State laws,

1.2ractices, procedures and, particularly, those that relate. to the

election of members of the Louisiana Supreme Court for the forth-

coming term in the primary, special and general elections to be

!iconducted commencing August 19, 1972.

9.

ihetitioner further alleges that defendants herein have previously

Il maintained, do now maintain, and will continue to perpetuate

!! arbitrary and impermissible discriminations as against petitioner

Hand those similarly situated by maintaining, supporting and imple-

menting statutes that have resulted in and will result in malappor-

l!tionment of the Louisiana Supreme Court; petitioner is and will

!continue to be damaged and injured irreparably by such unlawful ane

unconstitutional actions and especially with respect to such actior

insofar as the forthcoming primary elections of August 19, 1972 arE

1,1concerned. ,

4

ij

ft

10.

For the reasons herein set forth, petitioner desires and is entitled

to have this Honorable Court declare the following provision of the

Louisiana Constitution:

(a) Article 7, section 9 of the Louisiana Constitution

of 1921

to be unconstitutional, illegal, null and void.

11.

Petitioner has no plain, adequate or effective remedy at law to

:redress the wrongs emanating from the constitutional provision

:referred to in Article 4 and also has no plain, adequate or effec-

tive remedy at law, to avoid the effect cf said constitutional

Lprovision other than to invoke the equity powers of this Court;

!ishe respectfully requests that she and those similarly situated be

!!granted injunctive relief and that this court, in a manner and fOrM

to be determined by it, fashion and effectuate a plan of reepoor-

htionment for the Louisiana Supreme Court which will accord to

petitioner and those similarly situated, her constitutional rights,

;1!privileges and immunities.

hWHEREFORE, PETITIONER PRAYS THAT:

1. This petition and the requests herein be made heard

and determined by a District Court of three judges

as required by 23 U.S.C. 2234;

. , .

2. Defendants be served with a copy of this complaint;

3. An appropriate order issue herein directed to defendants,

commanding them to appear before this Court, at a time

and on a date designated, to dhow cause why an'intar-

locutory injunction should not issue herein, enjoining,

restraining and prohibiting them from discriminating

against and depriving petitioner of her rights to equal

protection of the laws and, in addition, enjoining,

restraining and prohibiting them from acting under or

in any manner implementing any of the following

constitutional provisions of Louisiana:

(a) Article 7, section 9, Constitution, State of

Louisiana.

4. Upon the final hearing of this cause upon its merits,

!I the interlocutory injunction be made permanent and the

Court declare that Article 7, section 9 of the Constitu-

.tion of State of Louisiana is unconstitutional, illegal,

r. null, void and of no effect;

6

ii i I 5. In a form and manner to be determined by the Court, a

ii plan of reapportionment of the Louisiana Supreme Court

,ge

_

".. .

be fashioned and Put into effect so as to guarantee

to petitioner' in the forthcoming elections her rights

and Privileges as a citizen of the United States, to

equal -,rotection of the laws secured her by the

Constitution and laws of the United States and her

civil rights, secured by law.

!Address

BY:

CHARLZS F. 3ARBZ:P.A, Trial Attorney

Attorney for :Petitioner

2. 0. 3ox 247

Hetairie, - Louisiana 70004

(Area 504) 337-4950

of Petitioner: Mrs. 3etty 31

1S17 Neyrey Drive

-Metairie, Louisiana

•1

Civil Action Number 72-200

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA, BATON ROUGE DIVISION/

MRS. BETTY WELLS

Petitioner

THE GOVERNOR OF LOUIS/ANA - THE HONORABLE EDWIN EDWARDS,

THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE STATE OF LOUISIANA -

THE HONORABLE WADE. 0. MARTIN, R. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

OF LOUISIANA - THE HONORABLE WILL/AM GUSTE, THE STATE

CUSTODIAN OF VOTING MACHINES FOR LOUISIANA - THE

HONORABLE DOUGLAS FOWLER. THE DEMOCRATIC STATE

CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF LOUISIANA and THE

REPUBLICAN STATE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF LOUISIANA

Defendants

1

;•FILED: DY.CLK..

i;

AMENDED COMPLAINT

Comes. now the plaintiff, and as of -course in accordance with

Rule : 15(a)., Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, amends Paragraph 2(f).

..of the complaint in this action so that the same will read as

follows:

(2.

The defendants herein are:

(f) The Republican State Central Committee - Its Chairman

is the Honorable James H. Boyce, whose office is located

in the City of Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish,

Louisiana.)

CHARLES F. BARBERA, Trial Attorney

Attorney for Petitioner

P. O. Box 247

.Metairie, LA 70004

(Area 504) 837-4950

„

, -

Civil Action Number 72-200

UN/TED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA, BATON ROUGE DIVISION

MRS. BETTY WELLS

Petitioner

THE GOVERNOR OF LOUISIANA - THE HONORABLE EDWIN EDWARDS,

THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE STATE OF LOUISIANA -

THE HONORABLE WADE 0. MARTIN. JR., THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

OF •LOUISIANA - THE HONORABLE WILL/AM GUSTE. THE STATE

CUSTODIAN OF VOTING MACHINES FOR LOUIS/ANA - THE

HONORABLE DOUGLAS FOWLER, THE DEMOCRATIC STATE

CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF LOUISIANA and THE

REPUBLICAN STATE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF LOUISIANA

Defendants

DY.CLK.:

NOTICE OF AMENDED COMPLAINT

;!

_ , .Please take notice that the within is a. copy of the amended ,

ii

_ . . . . . .. . _ . . . . .. . . . • .

complaint filed in this action as a matter of course pursuant to

:Rule 15(a) Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, on the ez2J- day of

.July, 1972.

h <

CHARLES F. BARBERA, Trial Attorney

Attorney for Petitioner

P. O. Box 247

Metairie, LA 70004

(Area 504) 837-4950

APPENDIX B

;4 .

•

IN THE

MICHAEL RODAK, JR.,CLERK

reme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

7 2 6 2

No. MOO•

MRS. BETTY WELLS,

Appellant,

versus

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL.,

Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court,

Middle District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

CHARLES F. BARBERA

Attorney for Appellant

P. 0. Box 247

Metairie, LA. 70004

(Area 504) • 837-4950

•

:

• INDEX

Opinion Below 1, Appendix A

Jurisdiction 1-2

Constitutional Provisions 2-4, Appendix B

Question Presented 4

Statement 4-14

14-15

la-8a

8a-9a

10a-14a

• Certificate of Service 15a-16a

TABLE OF CASES

Avery v. Midlandl County, 390 U.S. 474, 88 S.Ct.

1114, 20 L.Ed.2d 45 6, 18

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 82 S.Ct. 691, 7 L.Ed

2d 663 • 5, 6, 15

Bannister v. Davis, 263 F.Supp. 202 12

Hadley v. Junior College District, 397 U.S. 50, 90

S.Ct. 791, 25 L.Ed.2d 45 6, 8, 9, 10, 15

Kilgarlin v. Hill, 386 U.S. 120, 87 S.Ct 820, 17

L.Ed.2d 771 12, 13

• Radio Corporation of America v. U.S., 95 F.Supp.

Conclusion

Appendix A

Appendix B

• Appendix C

660 2

Reynolds v. Simms, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12

• L.Ed.2d 506 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 15

Swann v. Adams, 385 U.S. 440, 87 S.Ct. 569, 17

L.Ed.2d 501 12, 13, 14

•114 .u1-11i

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1971

No. 72-200

MRS. BETTY WELLS,

versus

EDWIN EDWARDS, ET AL.,

Appellant,

Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court,

Middle District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division

JURISDICTION STATEMENT

THE OPINION BELOW

The Memorandum Decision of the United States Dis-

trict Court, Middle District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge

Division is reported at F.Supp , and appears

herein as Appendix A. No other written opinions have

been delivered.-

STATEMENT OF THE GROUNDS ON WHICH THE

JURISDICTION OF THIS COURT IS INVOKED

This is a civil action wherein the appellant, Mrs.

Betty Wells, sought declaratory and injunctive relief

2. 3

whereby Article VII, Section 9 of the Louisiana Con-

stitution should be declared unconstitutional as viola-

tive of the one-man, •one-vote rule. This suit was

brought pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2281 wherein it is pro-

vided that a three judge district court should be con-

vened when the constitutionality of a state constitu-

tional provision is in question.

The judgment to be reviewed is that ruling rendered

by the three judge panel appointed for the United States

District Court, Middle District of Louisiana, Baton

Rouge Division for Civil Action Number 72-200. That

ruling was issued on August 16, 1972. No petition for

rehearing was filed. The notice of appeal was filed in

the United States District Court for the Middle District

of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division, the court possess-

ed of the record, on the 26th day of August, 1972. (Rule

33).

Jurisdiction of the appeal is conferred on this Court

by Title 28 of the United States Code, Section 1253.

The leading case in authority for sustaining the

jurisdiction of this Court is Radio Corporation of A-

merica v. U. S., D. C. Illinois 1950, 95 F.Supp. 660, af-

firmed 71 S.Ct. 806, 341 U.S. 412, 95 L.Ed. 1062.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

The validity of Article VII, Section 9 of the Louisiana

Constitution is here involved. The full text of that arti-

cle is as follows:

7

• - -Art. VII, Section 9. Supreme court districts;

- justices

. Section 9. The State shall be divided into

• - six Supreme Court Districts, and the Supreme

• • Court, except as otherwise provided in this

Constitution, shall always be composed of

Justices from said Districts.

First district.. The The parishes of Orleans, St.

• Bernard, Plaquemines and Jefferson shall