Chisom v. Roemer: Extending Voting Rights to Judicial Elections

In 1989, 64-year-old Revius O. Ortique Jr., Chief Judge of the Orleans Parish Civil District Court in Louisiana, said that after trying unsuccessfully for years to get elected to the state’s highest court, he was finished with Louisiana Supreme Court elections unless the election district was split. “At my age now, I don’t intend to run unless I feel confident I can win,” he told the Abbeville Meridional.

Judge Ortique’s professional pedigree should have given him this confidence. After graduating from Southern University Law School in the 1950s, the New Orleans native and World War II veteran opened a private practice and built a reputation as a “dogged civil rights lawyer” who fought to integrate labor unions and public facilities.

He was later elected as a civil district judge and served as the president of the National Bar Association (the nation’s oldest and largest network of Black attorneys and judges), as a five-term president of the Urban League of Greater New Orleans, and as a three-term president of the Community Relations Council.

Over the course of his career, five United States presidents would appoint Judge Ortique to various councils and commissions.

But in Louisiana, discriminatory election procedures and racial bloc voting kept Black jurists like him from the state’s highest court.

In 1991, after five years of arguing that Louisiana’s judicial elections violated Section Two of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) accomplished the necessary breakthrough to help Black judicial candidates. LDF took Chisom v. Roemer to the U.S. Supreme Court, winning a six-to-three decision for the plaintiffs, Black registered voters in Orleans Parish. The victory paved the way for Judge Ortique to become the first Black justice on the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1992.

Affidavit of Israel M. Augustine; of Revius O. Ortique, Jr.; of Silas Lee, III

Disenfranchising Black Voters

Because of the way Louisiana aligned its voting districts, the state’s electoral system denied Black voters an equal opportunity to elect judges to the state Supreme Court. Until 1991, the Louisiana Supreme Court was composed of seven judges. Five of these judicial seats came from single-member districts, and two came from District One, the state’s largest, most populous, and only multimember district. To win a judicial seat, a candidate had to receive the majority vote in their district, which meant that in District One, the two candidates with the most votes in an at-large election won. District One consisted of four parishes: Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson. Orleans Parish was home to about half of District One’s residents, and it had more Black than white registered voters. But even if every Black voter in Orleans Parish voted for the Black candidate, that Black candidate could not win election to either of District One’s two judicial seats because more than three-fourths of the registered voters in the district’s other three parishes were white and voted as a bloc against the Black candidate of choice. In District One judicial elections as late as the 1980s, no plurality of white voters had supported the Black candidate.

In September 1986, on behalf of the approximately 135,000 Black registered voters of Orleans Parish, LDF filed the class action lawsuit Chisom v. Edwards in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana against Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards, Secretary of State James H. Brown, and Commissioner of Elections Jerry M. Fowler. The lawsuit alleged violations of Section Two of the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act (42 U.S.C. § 1983), and the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Complaint

Three months before, in Thornburg v. Gingles, the U.S. Supreme Court had set a precedent establishing the criteria that voters must demonstrate in a Section Two challenge to discriminatory election procedures in such multimember districts. Congress amended Section Two of the Voting Rights Act in 1982 in response to the Supreme Court’s 1980 decision in Mobile v. Bolden, which held that Section Two required a showing of “discriminatory intent.” The amended Section Two made clear that only a showing of discriminatory effect (not intent) was required to demonstrate a violation, stating in part, “No voting qualification … or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

In Thornburg v. Gingles, the Court held that a successful Section Two challenge requires plaintiffs to establish three criteria: that a minority group is large and geographically compact enough to function as a voting majority within its own district; that the minority group is politically cohesive; and that a white voting majority is operating as a bloc that usually defeats the minority’s preferred candidate.

Using these criteria, lawyers for the plaintiffs in the Chisom case argued that the judicial election procedures in Louisiana’s District One kept minority voters from electing candidates of their choice. At trial, LDF attorneys presented District Court Judge Charles Schwartz Jr. with a study of voting patterns in 34 recent judicial elections in District One.

Black voters had supported Black candidates in 29 of these elections, but not once had white voters cast a majority of their votes for any Black candidate. To solve the problem of Black vote dilution in District One, the attorneys presented possible ways for the state to create a majority-Black voting district within its boundaries.

Judge Schwartz dismissed the suit in May 1987. Although he acknowledged the plaintiffs’ evidence of discrimination, he said they had failed to show an intent to discriminate sufficient to support their constitutional claims. He also ruled that judges were not “representatives” within the meaning of Section Two of the Voting Rights Act. Thus, according to Judge Schwartz, Section Two did not cover judicial elections.

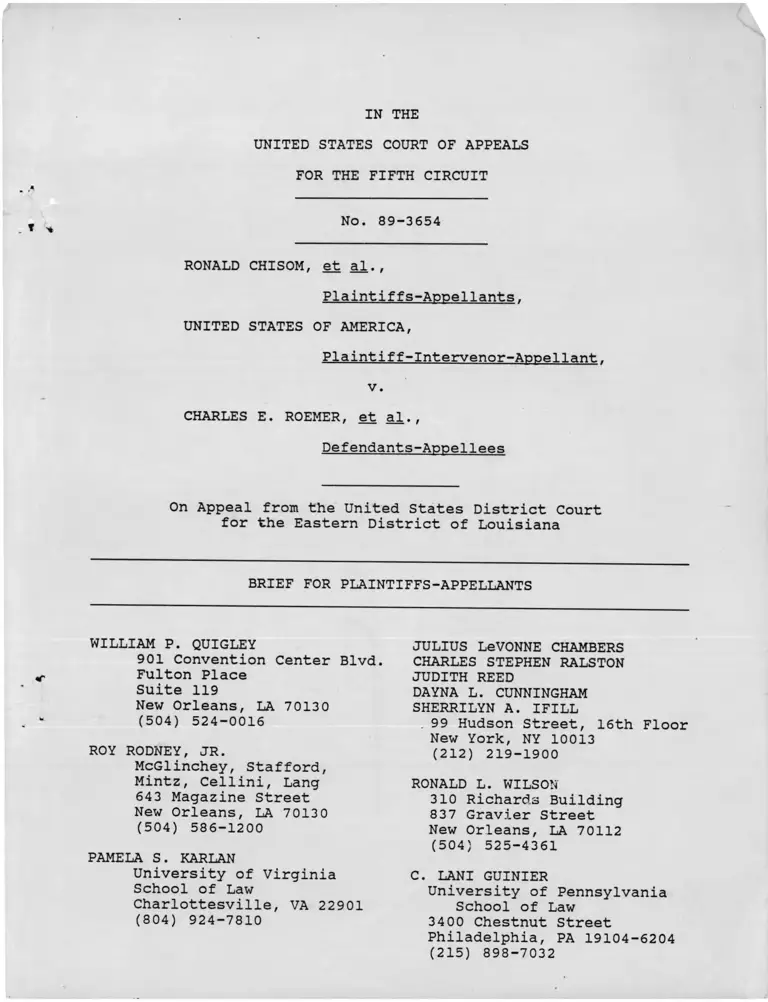

Correspondence from Karlan to Ganucheau (Clerk); Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants Ronald Chisom, et al.; Record Excerpts

A Victory on Appeal

LDF appealed this ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and won in February 1988. In a unanimous decision, a three-judge panel ruled that Congress had intended Section Two of the Voting Rights Act to eliminate all discriminatory voting practices, including those used in judicial elections. “Where racial discrimination exists, it is not confined to elections for legislative and executive officials; in such instance, it extends throughout the entire electoral spectrum,” the panel ruled. It sent the case back to District Court, instructing it to decide whether District One’s at-large voting procedures discriminated against minority voters.

“This victory for Black voters in Orleans Parish … helps to reaffirm the principle that Congress intended the Voting Rights Act to have the broadest possible application,” said LDF’s Director-Counsel Julius Chambers. “We are encouraged that this action will pave the way for new election districts to be drawn and in place in time for Louisiana’s judicial election scheduled for September.”

Louisiana’s government officials, however, did not want to redraw the state’s election districts by September 1988. Declaring the case a matter of national importance, new Louisiana Governor Buddy Roemer immediately appealed the Fifth Circuit decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. Roemer argued that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 applied to legislative but not judicial races, and if the Supreme Court did not reverse the Fifth Circuit’s ruling, the decision would have implications for judicial elections in 41 other states. “If the Court does not take this case, chaos will ensue,” the petition for review warned.

Eight states filed an amicus brief backing Louisiana’s position, but the Reagan administration’s Department of Justice (DOJ) disagreed. Calling the appeal unready for the Supreme Court, the DOJ wrote in a brief, “While elected judges do not represent voters in the same way that legislators do, when a state chooses to have an elected judiciary, it establishes a policy that judges will be selected by voters to express and represent the civil and legal views of the community.”

The Supreme Court denied Louisiana’s appeal request. William “Bill” Quigley, LDF’s New Orleans local counsel, said this was good news: “The fact that the Supreme Court did not decide to review the court decision, which was favorable to the Voting Rights Act, does send a clear signal that the law does apply to judicial elections.”

LDF attorney Charles S. Ralston said that state officials were nervous about the idea of minority candidates receiving judgeships. “There’s a lot of concern from judges about this whole issue,” he told The Philadelphia Tribune.

Robert Pugh, the state’s attorney, said he had no problem with Black judges, but he did not want the electoral system to have to change to achieve minority representation.

“We first started elected judges 138 years ago. And, for 109 years, it’s been exactly this way.” LDF’s point was that this system had long been a thinly veiled means of keeping non-white judges off the bench for more than a century.

A Second District Court Trial

Judge Schwartz again presided over the second trial before the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana in April 1989. To support the argument that white voters would not elect Black judges, several Black community leaders testified that, despite overwhelming support from Orleans Parish and endorsements from the press as well as white and Black political leaders, they could not attract enough white votes to secure electoral victories. Judge Ortique of the Orleans Parish Civil District Court testified that voters in the Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes were hostile to Black people. Civil District Judge Bernette Johnson said during her testimony that “it would not make sense for a Black candidate to launch a campaign—an expensive campaign—to win votes in Jefferson, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard Parish.” She added, “If I offer my credentials and have an opportunity to present myself, if people are fair, they perhaps would consider me as a candidate. But from living in this area, I don’t think it would make sense to offer myself as a candidate” in those parishes. Judge Johnson offered as an example that voters in part of Jefferson Parish had recently elected former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke to the District 81 seat in the state legislature. “I can’t believe people with this mindset would also support me,” Judge Johnson said.

Court Transcripts

Judge Schwartz told Judge Johnson during her testimony that Duke’s election was not a fair example of discriminatory voting patterns throughout District One. He said that on the other hand, a white candidate would not try to campaign against a Black candidate in a New Orleans housing project, noting, “If you want to add some humor to it, I live in District 81.” Judge Johnson replied, “I wasn’t saying it for humor, Judge, I was saying I wouldn’t offer myself as a candidate in that district.”

Judge Schwartz ruled against the Black registered voters for the second time in September 1989. He found that even though a majority of Black voters lived within an area that could be defined as a subdistrict, the Black population was not large enough to constitute a majority in a district, which was among the criteria needed to establish a Section Two violation. He further ruled that the Black voters had not provided enough evidence to demonstrate the existence of racially polarized voting, in which the white voting majority acted as a bloc against Black candidates. He found that Black voters could elect Black candidates of their choice in Orleans Parish-only elections, and they could elect white candidates in the four-parish district.

In an appeal to the Fifth Circuit, LDF attorneys argued that “the stipulations and uncontradicted evidence squarely establish the existence” of Section Two violations in District One’s judicial elections based on the criteria established in the Thornburg v. Gingles precedent. “The differential support of Black candidates is staggering. Within Orleans Parish, Black support for Black candidates in contested elections since 1978 has averaged 80%. White support for those same candidates has averaged only 17%.” The brief noted that the District Court did not contest testimony showing that “white voters within the First District, particularly whites in the three suburban parishes, simply will not vote for Black judicial candidates.” LDF argued that Congress passed Section Two to protect minority voters against such vote dilution, especially when those same voters held a lower economic status and for generations had been subjected to discriminatory education, housing, and employment practices. They cited the Thornburg v. Gingles decision, which stated, “The essence of a Section Two claim is that a certain electoral law, practice, or structure interacts with social and historical conditions to cause an inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by Black and white voters to elect their preferred representatives.” Furthermore, Louisiana’s electoral history was so rife with racist practices—including all-white primaries and voter registration barriers like citizenship tests and educational and property requirements—that the state was a “covered jurisdiction” under Section Five of the Voting Rights Act, requiring it to receive preapproval from a court or the DOJ before changing any voting law.

Chisom v. Roemer Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Nonetheless, on November 2, 1990, the Fifth Circuit ruled against the Black voters, overturning its earlier ruling in a seven-to-six en banc decision. Without disputing the significant evidence of Black vote dilution, the Fifth Circuit said that the Voting Rights Act did not apply to judicial elections because, as Judge Schwartz had ruled earlier, judges are not “representatives” of the people, but “servants” of the law and thus not covered by Section Two.

Speaking to the Abbeville Meridional, Judge Ortique disputed this interpretation. “The fact of the matter is that all public officials are servants of the people,” he said. “It would appear to me that if the state is going to use voting as the process by which those selections are made, it’s not a question of who is a representative or who is not a representative, but, rather, whether the voting process or electoral process is going to be fair.”

The Supreme Court Decides

LDF took its appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. The LDF brief addressed Judge Schwartz’s ruling that Black voting participation in Orleans Parish countered claims of Black vote dilution. “It is, of course, true that African American candidates have won election to both judicial and nonjudicial offices within Orleans Parish. … But they have done so in spite of overwhelming white support for their opponents; they won only because African American voters outnumber white voters within Orleans Parish. … Put simply, analysis of voter behavior in elections involving the four-parish area establishes two things: first, that voting is so racially polarized that no African American candidate can win in an election in which residents of all four parishes vote, and second, that African Americans within Orleans Parish have the potential to elect the candidate of their choice in Orleans Parish-only contests.”

Chisom v. Roemer Brief for Petitioners

LDF argued that, by dismissing the Section Two claims on the grounds that judges were not “representatives” covered by the Voting Rights Act, the rulings of the District Court and the Fifth Circuit failed to consider the uncontested evidence of voter discrimination that rendered the minority voice as unimportant in judicial elections. LDF attorneys wrote, “To permit states to use systems for electing judges that deny African Americans an effective voice tells African American citizens that their views regarding who should sit in judgment over the entire community are not worthy of the respect accorded the views of white voters, thereby denying African Americans equal dignity. Moreover, it cannot help but breed cynicism regarding the fairness of the judicial system as a whole to have a bench so overtly unrepresentative of the community whose power it exercises.”

The U.S. Solicitor General with the Justice Department joined LDF on behalf of the Black registered voters. During the oral argument on April 22, 1991, U.S. Solicitor General Kenneth Starr, on behalf of the federal government, criticized the lower court rulings, arguing that judges were representatives of the people because they were elected by popular consent and accountable to voters.

“That’s what the Voting Rights Act is all about,” Starr contended. “It’s about voting, and it’s about elections.”

Justice Antonin Scalia, who interpreted the Voting Rights Act narrowly, asked Starr how it was possible to determine whether a white voting majority had diluted a minority vote in judicial elections when the law did not require equal representation for justices on the Louisiana Supreme Court.

“It seems to me you need a standard for dilution,” Justice Scalia said. “You don’t know what watered beer is unless you know what beer is.” He further pressed Starr to clarify the standard for vote dilution, asking what the baseline was.

Starr replied that the congressionally mandated baseline involved establishing “whether there is in fact a dilution of the effectiveness and the ability of minorities to participate fully in the electoral process and to elect candidates of their choice.”

Even so, the burden on the plaintiffs was not to prove Black vote dilution, or to create a “baseline” that would determine whether white majority rule had influenced the racial makeup of justices on the Louisiana Supreme Court. LDF attorneys had offered uncontested evidence—over five years and several court appearances—that showed no Black justice had ever been elected to Louisiana’s highest court. The focus of the argument before the U.S. Supreme Court was whether the 1982 amendment to Section Two covered judicial elections. Pamela S. Karlan of the University of Virginia School of Law, a cooperating attorney with LDF who delivered the oral argument before the Supreme Court, summarized the issue: “We’re claiming that the present system dilutes our ability to participate equally, because due to racial bloc voting, due to a history of discrimination, due to racial appeals and campaigns and the like, Black citizens in Louisiana are not able to participate … to the same degree that white citizens are able to participate in selecting a supreme court that rules all of them.”

LDF argued in its brief that because Congress had “expressly directed” that the Voting Rights Act’s Section Two and Section Five should be “interpreted in tandem,” and because the Supreme Court had previously held that Section Five covered changes to judicial elections, Section Two also applied to the election of judges.

The Court agreed with the Black voters of Orleans Parish and LDF. The majority found, in a six-to-three decision, that “representatives” refers to “winners of representative, popular elections, including elected judges.” Delivering the opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens, who had been appointed by moderate Republican President Gerald Ford in 1975, said, “It is difficult to believe that Congress, in an express effort to broaden the protection afforded by the Voting Rights Act, withdrew, without comment, an important category of elections from that protection. Today we reject such an anomalous view, and hold that state judicial elections are included within the ambit of Section Two as amended.”

To comply with the ruling, the Louisiana state legislature redrew the judicial electoral map, creating a single-member district composed of a majority of Black voters anchored in Orleans Parish. In 1992, Judge Ortique was finally elected as the first Black justice on the Louisiana Supreme Court. He served until 1994, when he retired at age 70. Judge Johnson succeeded him and became the first Black woman elected to the Court, holding office until her retirement in 2020. Judge Piper D. Griffin, the third Black justice in Louisiana Supreme Court history, is an associate justice on the Court as of 2024. Far beyond Louisiana, Chisom v. Roemer has become a landmark precedent, bolstering voting rights and spurring challenges to judicial district lines across the country.